Abstract

Background

Several US organizations now recommend starting average-risk colorectal cancer (CRC) screening at age 45 years, but the prevalence of colonic neoplasia in individuals younger than 50 years has not been well characterized. We used a national endoscopic registry to calculate age-stratified prevalence and predictors of colorectal neoplasia.

Methods

Outpatient screening colonoscopies performed during 2010–2020 in the GIQuIC registry were analyzed. We measured the prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas by age, sex, and race/ethnicity, as well as the prevalence ratio (PR) of neoplasia compared to the reference group of 50–54 year-olds. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to identify predictors of neoplasia.

Results

We identified 3,928,727 screening colonoscopies, of which 129,736 (3.3%) were performed on average-risk individuals younger than 50 years. The prevalence of advanced neoplasia was 6.2% for 50–54 year-olds and 5.0% (PR 0.81, 95% CI 0.78–0.83) for average-risk 45–49 year-olds. Men had higher prevalence of neoplasia than women for all age groups. White individuals had higher prevalence of advanced neoplasia than persons of other racial/ethnic groups in most age groups, which was partially driven by serrated lesions. On multivariable regression, White individuals had higher odds of advanced neoplasia than Black, Hispanic, and Asian individuals in both younger and older age groups.

Conclusions

In a large US endoscopy registry, the prevalence of advanced neoplasia in 45–49 year-olds was substantial and supports beginning screening at age 45 years. White individuals had higher risk of advanced neoplasia than Black, Hispanic, and Asian individuals across the age spectrum. These findings may inform adenoma detection benchmarks and risk-based screening strategies.

Keywords: advanced neoplasia, early-onset colorectal cancer, GIQuIC

Graphical Abstract

Lay Summary

In a national study of average-risk individuals younger than 50 years who underwent screening colonoscopy, 5% of 45–49 year-olds had advanced colorectal neoplasia, which supports screening in this group.

Introduction

A number of countries in North America, Europe, Asia, and Oceania have witnessed a rise in incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC), defined as CRC diagnosed before age 50 years.1 An increase in colorectal cancer (CRC) mortality among younger individuals has also been observed in four high income countries, including the United States (US).2 In response to these concerning epidemiological trends, and informed by cost-utility modeling,3–5 US organizations including the American Cancer Society, US Preventive Services Task Force, and the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer have updated their guidelines to recommend CRC screening starting at age 45 years for average-risk individuals.6–8 However, the prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas among average-risk individuals younger than 50 years has not been well characterized. A few recent studies have examined this topic,9–11 but the generalizability of these findings may be limited by older data, geographic restriction, or modest sample size.

It is critically important to understand the prevalence of neoplasia among younger individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy—including differences by age, sex, and race and ethnicity—because quality benchmarks for the detection rates of advanced neoplasia and adenoma have not been established in these populations. Large real-world data would also permit more granular risk stratification based on individual characteristics, which could inform decisions regarding screening modality based on available resources while ensuring equity for outcomes and balancing the benefits and harms of screening.

The main objectives of this study were to calculate age-stratified prevalence and risk factors for colonic neoplasia in a large group of individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy in the US, with an emphasis on persons younger than 50 years. In addition, we sought to examine whether the proportion of individuals aged 45 to 49 years undergoing screening colonoscopy changed over time.

Methods

Population

This study used data from GI Quality Improvement Consortium (GIQuIC), a national endoscopy registry established in 2010 by the American College of Gastroenterology and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy for the purposes of quality improvement, performance evaluation, and research. All data are entered and submitted by individual sites using a standardized collection form.12 Participation in the registry is voluntary and research using deidentified data has been exempted from review by the Western Institutional Review Board.

This analysis included all outpatient colonoscopy reports between 1/1/2010 and 12/31/2020 that were performed for the indication of screening for colonic neoplasia. In GIQuIC, each individual has a unique identifier that is specific for a site but not for the entire database, so a single individual who has undergone procedures at multiple participating sites may potentially be counted as multiple individuals. Only data from the first colonoscopy for each site-patient was recorded, although this also included any findings from follow-up colonoscopies performed within 180 days of the initial examination that were considered part of the same episode of care. Screening for colonic neoplasia is one of more than 15 selectable indications in GIQuIC, and a 2018 internal audit of 1550 colonoscopy records in the registry found that indication for examination was 98.7% accurate when compared to medical records. Procedures performed for any other indication, on patients outside the age range of 18 to 89 years, with inadequate bowel preparation (defined as not sufficient to accurately detect polyps >5 mm in size), and without reported photo-documentation of the appendiceal orifice or terminal ileum were excluded. To minimize reporting bias, the analysis also excluded reports from endoscopists who provided pathology results on less than 50% of their procedures in which polyps were removed or biopsies were taken.

Exposures

The following individual- and facility-level data were extracted: age, sex, race and ethnicity, family history of CRC or advanced adenomas in a first-degree relative younger than 60 years, body mass index (BMI), insurance, American Society of Anesthesiologists class, sedation type, and facility type. For race and ethnicity, all Hispanic individuals were classified as Hispanic, regardless of race. Individuals were considered average risk if they did not have a reported family history of CRC or advanced adenomas in a first-degree relative before age 60 years. Although some of these individuals (e.g., those with two first-degree relatives diagnosed at any age or one first-degree relative diagnosed after age 60 years) would be recommended to start screening at age 40 years or earlier based on the 2017 US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer guideline,13 these data were not captured in the registry.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the prevalence of advanced neoplasia in age groups younger than 50 years. Advanced neoplasia was defined as any of the following: 1) advanced adenoma (adenoma ≥10 mm, with high grade dysplasia, or with villous component); 2) advanced serrated lesion (sessile serrated polyp/lesion (SSL) ≥10 mm, SSL with dysplasia, or traditional serrated adenoma); 3) adenocarcinoma. Since serrated lesions are not consistently included in the definition of advanced neoplasia, sensitivity analyses excluding serrated lesions were also performed. Secondary outcomes included the prevalence of adenomas (not including SSLs), prevalence ratio (PR) of advanced neoplasia and adenomas compared to 50–54 year-olds undergoing screening, prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas stratified by sex and race and ethnicity, and predictors of advanced neoplasia and adenomas in the those younger vs. older than 50 years on logistic regression. To assess whether the proportion of screening colonoscopies in the 45–49 year age group changed over time, we examined trends overall and by sex and race and ethnicity from 2013 to 2020. Due to small sample size, procedures from 2010 to 2012 were excluded from the trend analysis.

Statistical analysis

For individuals aged 50 years and older, advanced neoplasia and adenoma prevalence for all screening colonoscopies were calculated—including the small proportion of persons with positive family history—to reflect real-world practice. Since there was a much larger proportion of individuals with a positive family history in those younger than 50 years, prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas both for those at average risk and all individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy were measured. For outcomes stratified by sex and race and ethnicity, only prevalence for those at average risk in individuals younger than 50 years was calculated because this more accurately reflects the low prevalence of positive family history in the general population. For multivariable logistic regression, a model was constructed with five commonly available and clinically relevant variables: age, sex, race and ethnicity, family history, and BMI. Patients with missing or unknown race and ethnicity data were excluded from the regression analysis. The Cochran-Armitage test was used to analyze trends over time. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P<0.05. Analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

During the study period, the registry collected data on 12,244,085 colonoscopies, which were performed by 5,678 endoscopists at 795 sites in 50 states and territories. A total of 3,928,727 screening colonoscopies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, of which 211,020 were performed on individuals younger than 50 years. Within this younger screening cohort, 129,736 procedures were performed on individuals without a family history of CRC or advanced adenomas. This group represented younger individuals at average risk for screening and constituted 3.3% of all screening colonoscopies. Since a 2009 guideline had recommended screening Black individuals starting at age 45 years,14 we conducted a subgroup analysis combining Black individuals younger than 45 years with non-Black individuals younger than 50 years and found 111,474 procedures that occurred before the recommended screening age during the study period.

Table 1 shows patient demographics and prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas for average-risk screening patients under 50 years. The majority (71.5%) of individuals were aged 45 to 49 years and 56.0% were women. The largest racial and ethnic groups were White (49.2%), Black (16.1%), Hispanic (5.1%), and Asian (2.8%), although data was missing or unknown in 23.7% of cases. The overall prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas was 4.8% and 26.4%, respectively. In the subgroup analysis without Black individuals aged 45–49 years, the prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas was 4.9% and 26.8%, respectively (data not shown). Since the neoplasia prevalence was similar with and without Black individuals aged 45–49 years, all racial and ethnic and age groups were included in the main analysis.

Table 1:

Characteristics of average-risk individuals under 50 years undergoing screening colonoscopya

| Variable | n (%) | Adenoma prevalence | Advanced adenomab/CRC prevalence | Advanced neoplasiab prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 129,736 (100.0%) | 26.4% | 3.4% | 4.8% |

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 | 2,249 (1.7%) | 7.4% | 0.8% | 1.8% |

| 30–39 | 9,898 (7.6%) | 17.6% | 2.3% | 3.4% |

| 40–44 | 24,837 (19.1%) | 24.2% | 3.0% | 4.6% |

| 45–49 | 92,752 (71.5%) | 28.3% | 3.8% | 5.0% |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 72,656 (56.0%) | 21.9% | 2.6% | 4.0% |

| Male | 57,080 (44.0%) | 32.1% | 4.5% | 5.7% |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 63,799 (49.2%) | 27.3% | 3.7% | 5.3% |

| AI/AN | 415 (0.3%) | 25.5% | 4.1% | 5.3% |

| Asian | 3,570 (2.8%) | 24.2% | 2.7% | 3.8% |

| Black | 20,942 (16.1%) | 22.8% | 3.1% | 3.7% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6,630 (5.1%) | 26.3% | 3.6% | 4.5% |

| NH/PI | 112 (0.1%) | 25.0% | 1.8% | 1.8% |

| Other | 3,477 (2.7%) | 25.6% | 3.3% | 5.0% |

| Missing / Unknown | 30,791 (23.7%) | 27.1% | 3.1% | 4.5% |

| BMI | ||||

| Underweight (12.0 – 18.4) | 265 (0.2%) | 18.1% | 2.6% | 3.8% |

| Normal (18.5 – 24.9) | 7,464 (5.8%) | 23.7% | 3.4% | 4.7% |

| Overweight (25.0 – 29.9) | 10,445 (8.1%) | 27.8% | 4.3% | 5.7% |

| Obese (30.0 – 59.9) | 11,875 (9.2%) | 29.5% | 4.8% | 5.9% |

| Unknown | 99,687 (76.8%) | 26.1% | 3.2% | 4.5% |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | 17,454 (13.5%) | 27.9% | 4.6% | 6.0% |

| Medicare | 223 (0.2%) | 28.7% | 5.4% | 7.6% |

| Medicaid | 460 (0.4%) | 26.1% | 3.7% | 4.6% |

| Tricare | 494 (0.4%) | 27.5% | 3.0% | 4.0% |

| Other | 13,491 (10.4%) | 27.2% | 4.1% | 5.4% |

| None | 2,001 (1.5%) | 27.0% | 4.0% | 5.1% |

| Unknown/Missing | 95,613 (73.7%) | 25.9% | 3.1% | 4.4% |

| ASA category | ||||

| I | 30,657 (23.6%) | 23.9% | 2.9% | 4.3% |

| II | 87,897 (67.8%) | 26.6% | 3.5% | 4.8% |

| III | 11,060 (8.5%) | 31.2% | 4.7% | 5.7% |

| IV / V | 122 (0.1%) | 28.7% | 4.1% | 6.6% |

| Teaching Facility | ||||

| No | 107,682 (83.0%) | 26.3% | 3.5% | 4.8% |

| Yes | 8,566 (6.6%) | 26.0% | 2.6% | 3.6% |

| Missing | 13,488 (10.4%) | 27.5% | 3.9% | 5.1% |

| Sedation type | ||||

| Deep | 27,878 (21.5%) | 26.5% | 3.5% | 4.9% |

| General | 3,445 (2.7%) | 30.1% | 4.8% | 6.0% |

| Moderate | 10,123 (7.8%) | 28.5% | 3.2% | 4.9% |

| None | 227 (0.2%) | 26.9% | 1.3% | 2.6% |

| Missing | 88,063 (67.9%) | 25.9% | 3.4% | 4.6% |

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; AI/AN, American Indian/Alaska Native; CRC, colorectal cancer; NH/PI, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists

Average risk is defined as not having a first-degree relative aged <60 years with CRC or advanced adenomas

Advanced neoplasia is defined as any of the following: 1) advanced adenoma (adenoma ≥10 mm, with high grade dysplasia, or with villous component); 2) advanced serrated lesions (sessile serrated lesion (SSL) ≥10 mm, SSL with dysplasia, or traditional serrated adenoma); 3) adenocarcinoma

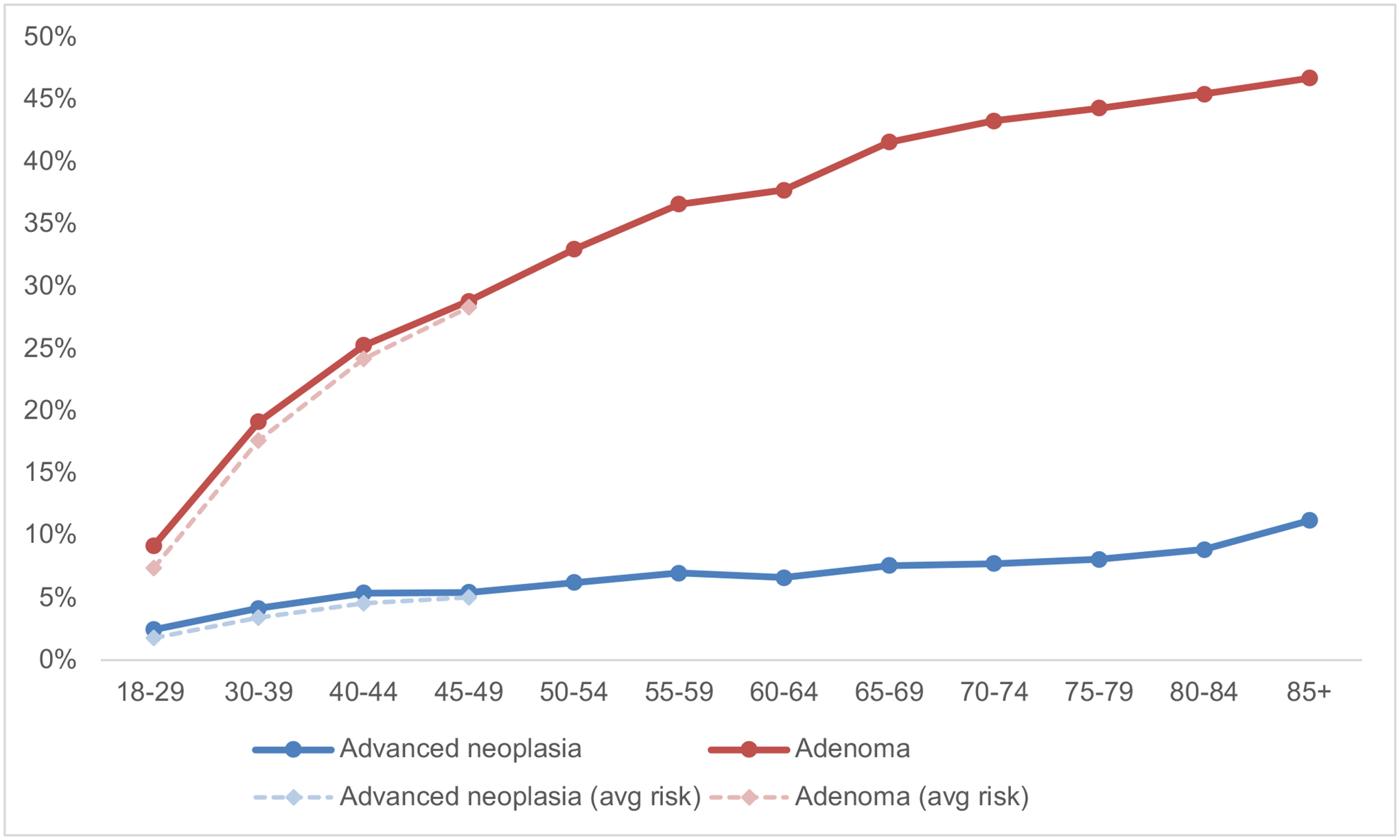

Prevalence by Age

The prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas stratified by age group is shown in Figure 1 and Table 2. For all screening exams, the prevalence of advanced neoplasia in those under 50 years ranged from 2.5% in the 18–29 year age group to 5.4% in the 45–49 year age group. Compared to the reference group of 50–54 year-olds, the prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas for all 45–49 year-olds was 12% (PR 0.88, 95% CI 0.86–0.90) and 13% (PR 0.87, 95% CI 0.87–0.88) lower, respectively. Among average risk 45–49 year-olds, the prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas was 19% (PR 0.81, 95% CI 0.78–0.83) and 14% (PR 0.86, 95% CI 0.85–0.87) lower, respectively, than the reference group.

Figure 1:

Prevalence of neoplasia in screening colonoscopya,b

a Average risk is defined as not having a first-degree relative aged <60 years with CRC or advanced adenomas

a Advanced neoplasia is defined as any of the following: 1) advanced adenoma (adenoma ≥10 mm, with high grade dysplasia, or with villous component); 2) advanced serrated lesions (sessile serrated lesion (SSL) ≥10 mm, SSL with dysplasia, or traditional serrated adenoma); 3) adenocarcinoma

Table 2:

Prevalence of neoplasia by age and family history

| Advanced neoplasiab | Advanced adenomab/CRC | Adenoma | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | N | n | Prevalence | PR (95% CI) | n | Prevalence | PR (95% CI) | n | Prevalence | PR (95% CI) | |

| Average-riska screening | 18–29 | 2,249 | 40 | 1.8% | 0.29 (0.21–0.39) | 17 | 0.8% | 0.16 (0.10–0.26) | 166 | 7.4% | 0.22 (0.19–0.26) |

| 30–39 | 9,898 | 339 | 3.4% | 0.55 (0.50–0.61) | 229 | 2.3% | 0.49 (0.43–0.55) | 1,745 | 17.6% | 0.53 (0.51–0.56) | |

| 40–44 | 24,837 | 1,132 | 4.6% | 0.73 (0.69–0.78) | 740 | 3.0% | 0.63 (0.58–0.67) | 6,010 | 24.2% | 0.73 (0.72–0.75) | |

| 45–49 | 92,752 | 4,655 | 5.0% | 0.81 (0.78–0.83) | 3,480 | 3.8% | 0.79 (0.76–0.81) | 26,287 | 28.3% | 0.86 (0.85–0.87) | |

| All screening | 18–29 | 5,632 | 138 | 2.5% | 0.39 (0.33–0.47) | 77 | 1.4% | 0.29 (0.23–0.36) | 516 | 9.2% | 0.28 (0.26–0.30) |

| 30–39 | 25,982 | 1,078 | 4.1% | 0.67 (0.63–0.71) | 703 | 2.7% | 0.57 (0.53–0.61) | 4,973 | 19.1% | 0.58 (0.57–0.60) | |

| 40–44 | 50,233 | 2,701 | 5.4% | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) | 1,836 | 3.7% | 0.77 (0.73–0.80) | 12,691 | 25.3% | 0.77 (0.75–0.78) | |

| 45–49 | 129,173 | 7,034 | 5.4% | 0.88 (0.86–0.90) | 5,256 | 4.1% | 0.85 (0.83–0.88) | 37,228 | 28.8% | 0.87 (0.87–0.88) | |

| 50–54 | 1,324,334 | 82,383 | 6.2% | REF | 63,132 | 4.8% | REF | 436,906 | 33.0% | REF | |

| 55–59 | 673,143 | 47,074 | 7.0% | 1.12 (1.11–1.14) | 37,293 | 5.5% | 1.16 (1.15–1.18) | 246,417 | 36.6% | 1.11 (1.11–1.11) | |

| 60–64 | 749,841 | 49,595 | 6.6% | 1.06 (1.05–1.08) | 38,837 | 5.2% | 1.09 (1.07–1.10) | 282,977 | 37.7% | 1.14 (1.14–1.15) | |

| 65–69 | 545,186 | 41,392 | 7.6% | 1.22 (1.21–1.23) | 33,364 | 6.1% | 1.28 (1.27–1.30) | 226,699 | 41.6% | 1.26 (1.26–1.27) | |

| 70–74 | 293,260 | 22,720 | 7.7% | 1.25 (1.23–1.26) | 18,505 | 6.3% | 1.32 (1.30–1.35) | 126,972 | 43.3% | 1.31 (1.31–1.32) | |

| 75–79 | 111,544 | 9,019 | 8.1% | 1.30 (1.27–1.33) | 7,450 | 6.7% | 1.40 (1.37–1.43) | 49,418 | 44.3% | 1.34 (1.33–1.35) | |

| 80–84 | 18,267 | 1,622 | 8.9% | 1.43 (1.36–1.50) | 1,418 | 7.8% | 1.63 (1.55–1.71) | 8,302 | 45.4% | 1.38 (1.36–1.40) | |

| 85+ | 2,132 | 239 | 11.2% | 1.80 (1.60–2.03) | 216 | 10.1% | 2.13 (1.87–2.41) | 996 | 46.7% | 1.42 (1.35–1.48) | |

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer

Average risk is defined as not having a first-degree relative aged <60 years with CRC or advanced adenomas

Advanced neoplasia is defined as any of the following: 1) advanced adenoma (adenoma ≥10 mm, with high grade dysplasia, or with villous component); 2) advanced serrated lesions (sessile serrated lesion (SSL) ≥10 mm, SSL with dysplasia, or traditional serrated adenoma); 3) adenocarcinoma

Prevalence by Sex

Men had higher prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas than women in every age group, including those younger than 50 years. The prevalence of advanced neoplasia among average-risk women aged 45–49 years (4.1%) was most similar to that of men in the 30–39 year age group (3.7%, Table 3, Supplemental Figure 1). Conversely, the prevalence of advanced neoplasia in average-risk men aged 45–49 years (6.2%) was most comparable to that of women aged 65–69 years (6.4%). Similar findings were observed for adenoma detection, with prevalence in average-risk men aged 30–49 years being comparable to that of women who were at least 10 years older (Table 3, Supplemental Figure 2).

Table 3:

Prevalence of neoplasia by sexa

| Advanced neoplasiab | Adenoma | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| 18–29 | 2.0% | 1.6% | 9.1% | 6.2% |

| 30–39 | 3.7% | 3.2% | 21.2% | 15.1% |

| 40–44 | 5.3% | 4.0% | 29.5% | 20.3% |

| 45–49 | 6.2% | 4.1% | 34.4% | 23.5% |

| 50–54 | 7.3% | 5.2% | 39.8% | 27.1% |

| 55–59 | 8.4% | 5.8% | 43.8% | 30.5% |

| 60–64 | 7.9% | 5.5% | 44.8% | 31.9% |

| 65–69 | 9.1% | 6.4% | 48.9% | 35.8% |

| 70–74 | 9.3% | 6.5% | 50.4% | 37.7% |

| 75–79 | 9.3% | 7.1% | 50.8% | 39.3% |

| 80–84 | 10.2% | 7.7% | 51.2% | 40.5% |

| 85+ | 11.8% | 10.7% | 50.3% | 43.4% |

Age 18–49 years: prevalence is for average-risk individuals undergoing screening; age 50 years and older: prevalence is for all individuals undergoing screening

Advanced neoplasia is defined as any of the following: 1) advanced adenoma (adenoma ≥10 mm, with high grade dysplasia, or with villous component); 2) advanced serrated lesions (sessile serrated lesion (SSL) ≥10 mm, SSL with dysplasia, or traditional serrated adenoma); 3) adenocarcinoma

Prevalence by Race and Ethnicity

The prevalence of advanced neoplasia in White individuals was higher than persons of other racial and ethnic groups for ages 18–59 years, with the exception of American Indian/Alaska Native individuals aged 45–49 years (Table 4, Supplemental Figure 3). For ages 60–79 years, the prevalence for White individuals was similar to that of Hispanic individuals but remained higher than that of other racial and ethnic groups. For ages 80 years and older, Black individuals had similar or higher prevalence of advanced neoplasia than Whites individuals, while Hispanic individuals had lower prevalence than both Black and White individuals. The prevalence of advanced neoplasia for White individuals aged 45–49 years was comparable to that of Hispanic individuals aged 50–54 years, Black individuals aged 55–59 years, and Asian individuals aged 65–69 years. Importantly, these results appeared to be driven by a consistently higher prevalence of advanced serrated lesions in White individuals compared to those of other racial and ethnic groups. Supplemental Table 1 shows the absolute difference in advanced neoplasia prevalence for White individuals relative to persons of other racial and ethnic groups, as well as how much of the difference is attributed to advanced serrated lesions. Of the groups stratified by age and race and ethnicity with cell count ≥10 (n=43), White individuals had a 1% or higher prevalence of advanced serrated lesions for 49% of the groups and less than 1% higher prevalence for 47% of the groups. White individuals had lower prevalence of advanced serrated lesions in only in 5% of the groups. In the sensitivity analysis excluding advanced serrated lesions from the definition of advanced neoplasia, Black individuals aged 60–84 years and Hispanic individuals aged 60–74 years had higher prevalence than White individuals, whereas the reverse was true when advanced serrated lesions were included (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 4:

Prevalence of neoplasia by race and ethnicitya

| Advanced neoplasiab | Adenoma | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | AI/AN | NH/PI | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | AI/AN | NH/PI |

| 18–29 | 2.0% | 0.6% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6.9% | 5.2% | 5.7% | 3.2% | 5.0% | 0.0% |

| 30–39 | 3.6% | 1.8% | 2.3% | 1.5% | 2.2% | 0.0% | 17.9% | 11.2% | 15.5% | 12.3% | 4.3% | 20.0% |

| 40–44 | 4.8% | 3.2% | 4.0% | 3.7% | 4.1% | 0.0% | 24.5% | 19.6% | 22.5% | 21.2% | 23.3% | 10.0% |

| 45–49 | 5.8% | 3.9% | 4.9% | 4.1% | 6.5% | 2.1% | 30.1% | 23.8% | 28.5% | 26.8% | 31.2% | 27.4% |

| 50–54 | 6.9% | 4.9% | 5.5% | 4.7% | 5.6% | 5.5% | 33.9% | 29.1% | 30.7% | 30.7% | 31.7% | 34.2% |

| 55–59 | 7.6% | 6.2% | 6.3% | 5.2% | 5.7% | 7.2% | 37.1% | 34.5% | 35.6% | 33.7% | 34.4% | 38.4% |

| 60–64 | 6.9% | 6.1% | 7.0% | 5.2% | 5.3% | 5.5% | 37.5% | 37.2% | 38.7% | 36.5% | 35.0% | 38.4% |

| 65–69 | 7.9% | 7.4% | 7.8% | 6.2% | 4.0% | 6.0% | 41.2% | 41.9% | 42.9% | 40.2% | 35.6% | 42.9% |

| 70–74 | 8.1% | 7.2% | 8.0% | 6.5% | 4.6% | 6.3% | 42.9% | 42.8% | 44.9% | 43.8% | 38.3% | 47.5% |

| 75–79 | 8.4% | 7.5% | 8.6% | 7.6% | 5.8% | 3.7% | 43.9% | 44.1% | 45.9% | 44.9% | 40.0% | 46.9% |

| 80–84 | 9.3% | 9.3% | 8.0% | 7.8% | 4.9% | 0.0% | 44.7% | 46.4% | 47.2% | 48.2% | 27.9% | 62.5% |

| 85+ | 11.4% | 13.3% | 9.0% | 11.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 45.8% | 46.4% | 43.3% | 48.1% | 85.7% | 50.0% |

Abbreviations: AI/AN, American Indian/Alaska Native; NH/PI, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Shaded cells: count<10

Age 18–49 years: prevalence is for average-risk individuals undergoing screening; age 50 years and older: prevalence is for all individuals undergoing screening

Advanced neoplasia is defined as any of the following: 1) advanced adenoma (adenoma ≥10 mm, with high grade dysplasia, or with villous component); 2) advanced serrated lesions (sessile serrated lesion (SSL) ≥10 mm, SSL with dysplasia, or traditional serrated adenoma); 3) adenocarcinoma

The prevalence of adenomas was generally higher in White individuals than persons of other racial and ethnic groups from age 18–49 years. Adenoma prevalence in White individuals was similar to Black individuals starting at age 60 years, lower than Hispanic individuals starting at age 60 years, and lower than Asian individuals starting at age 70 years. For ages 50 years and older, White individuals had higher prevalence of adenomas than those who were American Indian/Alaska Native but lower prevalence than those who were Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. The adenoma prevalence of White individuals aged 45–49 years was comparable to that of Black, Hispanic, and Asian individuals aged 50–54 years (Table 4, Supplemental Figure 4).

Predictors of Advanced Neoplasia and Adenomas

Factors associated with advanced neoplasia and adenomas on multivariable logistic regression, stratified by age at colonoscopy, are shown in Table 5.

Table 5:

Predictors of neoplasia among individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy, stratified by agea

| Age <50 years (n = 165,882) | Age 50+ years (n = 2,853,434) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced neoplasiab | Adenoma | Advanced neoplasiab | Adenoma | |

| Age | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| 18–29 | REF | REF | -- | -- |

| 30–39 | 1.70 (1.39 – 2.08) | 2.26 (2.02 – 2.52) | -- | -- |

| 40–44 | 2.33 (1.91 – 2.83) | 3.30 (2.97 – 3.67) | -- | -- |

| 45–49 | 2.49 (2.05 – 3.03) | 4.13 (3.72 – 4.58) | -- | -- |

| 50–54 | -- | -- | REF | REF |

| 55–59 | -- | -- | 1.15 (1.13 – 1.16) | 1.19 (1.18 – 1.20) |

| 60–64 | -- | -- | 1.07 (1.05 – 1.08) | 1.25 (1.24 – 1.26) |

| 65–69 | -- | -- | 1.24 (1.22 – 1.26) | 1.48 (1.47 – 1.49) |

| 70–74 | -- | -- | 1.27 (1.25 – 1.29) | 1.59 (1.58 – 1.61) |

| 75–79 | -- | -- | 1.35 (1.32 – 1.38) | 1.68 (1.66 – 1.71) |

| 80–84 | -- | -- | 1.51 (1.42 – 1.60) | 1.76 (1.70 – 1.82) |

| 85+ | -- | -- | 1.98 (1.70 – 2.30) | 1.83 (1.66 – 2.02) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Male | 1.38 (1.32 – 1.44) | 1.64 (1.60 – 1.68) | 1.45 (1.44 – 1.46) | 1.72 (1.71 – 1.73) |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||||

| White | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| AI/AN | 1.22 (0.91 – 1.65) | 0.93 (0.78 – 1.11) | 0.74 (0.68 – 0.80) | 0.88 (0.85 – 0.92) |

| Asian | 0.68 (0.59 – 0.77) | 0.89 (0.83 – 0.94) | 0.73 (0.71 – 0.75) | 0.97 (0.96 – 0.98) |

| Black | 0.65 (0.61 – 0.70) | 0.74 (0.72 – 0.77) | 0.82 (0.80 – 0.83) | 0.92 (0.91 – 0.92) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.84 (0.77 – 0.92) | 0.93 (0.89 – 0.98) | 0.89 (0.87 – 0.90) | 0.97 (0.96 – 0.98) |

| NH/PI | 0.72 (0.38 – 1.76) | 0.87 (0.64 – 1.18) | 0.74 (0.65 – 0.83) | 1.02 (0.95 – 1.08) |

| Other | 0.92 (0.81 – 1.06) | 0.94 (0.88 – 1.00) | 0.92 (0.89 – 0.95) | 1.00 (0.995 – 1.03) |

| Family History | ||||

| None | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Advanced Adenoma | 1.32 (1.22 – 1.42) | 1.14 (1.09 – 1.19) | 1.00 (0.97 – 1.03) | 0.92 (0.90 – 0.93) |

| CRC | 1.17 (1.12 – 1.23) | 1.06 (1.03 – 1.09) | 0.91 (0.89 – 0.93) | 0.90 (0.89 – 0.91) |

| BMI | ||||

| Underweight (12.0 – 18.4) | 0.92 (0.62 – 1.36) | 0.94 (0.76 – 1.15) | 1.18 (1.10 – 1.27) | 1.05 (1.003 – 1.09) |

| Normal (18.5 – 24.9) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Overweight (25.0 – 29.9) | 1.07 (0.98 – 1.17) | 1.15 (1.10 – 1.20) | 1.07 (1.05 – 1.09) | 1.19 (1.18 – 1.20) |

| Obese (30.0 – 59.9) | 1.30 (1.20 – 1.42) | 1.41 (1.35 – 1.48) | 1.27 (1.25 – 1.29) | 1.46 (1.44 – 1.47) |

| Unknown | 0.89 (0.83 – 0.96) | 1.12 (1.08 – 1.17) | 0.80 (0.79 – 0.81) | 1.09 (1.08 – 1.10) |

Abbreviations: AI/AN, American Indian/Alaska Native; NH/PI, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; CRC, colorectal cancer

Estimates are adjusted for all other variables shown in table. Analysis restricted to individuals with known race and ethnicity

Advanced neoplasia is defined as any of the following: 1) advanced adenoma (adenoma ≥10 mm, with high grade dysplasia, or with villous component); 2) advanced serrated lesions (sessile serrated lesion (SSL) ≥10 mm, SSL with dysplasia, or traditional serrated adenoma); 3) adenocarcinoma

Individuals younger than 50 years

For advanced neoplasia in individuals younger than 50 years, positive predictors included increasing age (OR 2.49, 95% CI 2.05–3.03 for age 45–49 years compared to age 18–29 years), male sex (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.32–1.44), family history of advanced adenomas (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.22–1.42) or CRC (OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.12–1.23), and obesity (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.20–1.42 compared to normal BMI). Relative to White individuals, Black (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.61–0.70), Asian (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.59–0.77), and Hispanic (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77–0.92) individuals were less likely to have advanced neoplasia.

Factors associated with adenomas were generally similar to those for advanced neoplasia, with a few differences. For race and ethnicity, the adenoma risk estimates for Black (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.72–0.77), Asian (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.83–0.94), and Hispanic (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.89–0.98) individuals relative to White individuals were attenuated compared to the advanced neoplasia risk estimates. In addition to obesity, overweight BMI (OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.10–1.20) was also a risk factor for adenomas.

Individuals aged 50 years and older

Compared to younger individuals, there were several differences in factors associated with advanced neoplasia in those aged 50 years and older. With respect to race and ethnicity, White individuals had higher risk of advanced neoplasia compared persons of other racial and ethnic groups. The protective association of being Black (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.80–0.83), Hispanic (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.87–0.90), and Asian (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.71–0.75) were attenuated in the older vs. younger age group. American Indian/Alaska Native (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.68–0.80) and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.65–0.83) individuals had a lower association with advanced neoplasia in the older but not younger group, although the risk estimates for older and younger Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander persons were similar. A family history of advanced adenomas was not associated with advanced neoplasia in those aged 50 years and older, and those with a family history of CRC actually had lower risk (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.89–0.93). All individuals with a BMI outside of normal range, including those who were underweight (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.10–1.27), had higher risk of advanced neoplasia.

For adenomas, risk estimates for Black (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.91–0.92), Hispanic (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.96–0.98), Asian (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.96–0.98), and American Indian/Alaska Native (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.85–0.92) individuals were attenuated compared to risk estimates for advanced neoplasia. Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander individuals had similar risk as Whites individuals. A family history of both advanced adenomas (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.90–0.93) and CRC (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.89–0.91) were associated with reduced risk of adenomas. Similar to advanced neoplasia, all individuals with a BMI outside of normal range had higher risk of adenomas.

Trends in screening colonoscopy use in the 45–49 year age group

From 2013 to 2020, the proportion of screening colonoscopies performed in the 45–49 year age group increased from 2.9% to 5.0% (P<.0001, Table 6). The proportion of procedures by sex remained stable over time, and women accounted for 56.3% of procedures in 2020 (P=0.40). In this age group, the proportion of colonoscopies performed on non-White individuals increased from 33.5% to 37.3% (P<.0001), and the biggest single year increase was observed from 2019 (34.3%) to 2020 (37.3%).

Table 6:

Trends in screening colonoscopy use in the 45–49 year age group, 2013–2020

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total | P trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, n (%) | All Ages | |||||||||

| 45–49 | 1,404 (2.9) | 6,066 (2.9) | 9,151 (2.6) | 15,158 (2.6) | 18,344 (2.6) | 23,564 (3.1) | 32,321 (4.1) | 23,120 (5.0) | 129,128 (3.3) | <.0001 |

| <45 and 50+ | 46,820 (97.1) | 207,023 (97.2) | 338,967 (97.4) | 575,127 (97.4) | 701,764 (97.5) | 734,657 (96.9) | 755,068 (95.9) | 439,246 (95.0) | 3,798,672 (96.7) | |

| Sex, n (%) | Age 45–49 years | |||||||||

| Female | 791 (56.34) | 3,445 (56.8) | 5,096 (55.7) | 8,542 (56.4) | 10,348 (56.4) | 13,379 (56.8) | 17,970 (55.6) | 13,005 (56.3) | 72,576 (56.2) | 0.40 |

| Male | 613 (43.7) | 2,621 (43.2) | 4,055 (44.3) | 6,616 (43.7) | 7,996 (43.6) | 10,185 (43.2) | 14,351 (44.4) | 10,115 (43.8) | 56,552 (43.8) | |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Non-White | 324 (33.5) | 1,557 (34.7) | 2,517 (35.9) | 3,958 (32.4) | 4,905 (33.3) | 6,357 (34.4) | 8,796 (34.3) | 6,934 (37.3) | 35,348 (34.6) | <.0001 |

| White | 643 (66.5) | 2,935 (65.3) | 4,494 (64.1) | 8,251 (67.6) | 9,826 (66.7) | 12,104 (65.6) | 16,829 (65.7) | 11,673 (62.7) | 66,755 (65.4) |

Discussion

Using a large US registry with 129,736 screening colonoscopies performed between 2010 and 2020 in average-risk individuals under age 50 years, we determined the prevalence of colonic neoplasia stratified by age. The prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas in average-risk 45–49 year-olds was 5.0% and 28.3%, respectively, which was 19% and 14% lower relative to 50–54 year-olds. Men had higher prevalence of neoplasia than women for every age group, and the prevalence of advanced neoplasia in average-risk men aged 45–49 years was comparable to that of women aged 65–69 years. The prevalence of neoplasia was generally higher for White individuals than for persons of other racial and ethnic groups in those younger than 50 years. The higher prevalence of advanced neoplasia in Whites individuals relative to those of other racial and ethnic groups, especially for older individuals, was driven by advanced serrated lesions. In persons younger than 50 years, predictors of advanced neoplasia on multivariable logistic regression included older age, male sex, family history of CRC or advanced adenomas, and obesity; Black, Hispanic, and Asian individuals had lower risk than White individuals. From 2013 to 2020, the proportion of screening colonoscopies in the 45–49 year age group increased, as did the proportion of non-White individuals who received procedures in this age group.

Our study is the largest analysis of colonoscopy data among average-risk individuals under 50 years to date. Although the number of average-risk individuals under 50 years may seem high, this group accounted for only 3.3% of all screening procedures during the study period. Within this group, 18,262 procedures (14.1%) were performed on Black individuals aged 45–49 years, for whom screening has been recommended since 2009 by the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines.14 In addition, our definition of average-risk included those with two first-degree relatives diagnosed with CRC at any age or those with one first-degree relative diagnosed after age 60 years, and these individuals would have been recommended start screening at age 40 years or earlier based on the 2017 US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer guideline.13 Reassuringly, a recent internal audit of the GIQuIC registry showed that procedural indication was highly accurate when compared to the medical record. Given that the registry also included data from nearly every US state and territory, these findings offer a representative snapshot of the US population.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Kolb et al. that included 17 studies of average-risk individuals younger than 50 years (N=51,811) found that the prevalence of advanced neoplasia (not including serrated lesions) was 3.6% in 45–49 year-olds and 4.2% in 50–54 year-olds,9 which is similar to our estimates of 3.8% and 4.8%, respectively. The prevalence ratio for 45–49 year-olds relative to 50–54 year-olds in our study (0.79) was comparable to that of Kolb et al. (0.86), but the difference was statistically significant in our study, likely due to the much larger sample size. Using the same definition for advanced neoplasia, Butterly et al. examined a cohort of “average-risk equivalent” individuals in the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry—including those with low-risk symptoms such as abdominal pain or constipation—and found a similar prevalence of 3.7% in persons aged 45–49 years.10 Both the Kolb et al. and Butterly et al. studies found a much lower prevalence of colorectal neoplasia in 45–49 year-olds (17.5–17.8%) than the prevalence of adenomas in our study (28.3%), which may reflect the educational and technological advances that have spurred higher adenoma detection rates over time. Kolb et al. included 10 of 17 studies that had concluded by 2011, and Butterly et al. used data collected since 2004. In contrast, our more recent study period may better reflect current adenoma detection rates in clinical practice. Two other studies used more recent but geographically restricted data. Shaukat et al. reported an advanced neoplasia detection rate of 3.3% among average-risk individuals aged 45–49 years in a large community practice, but the investigators’ more expansive definition of advanced neoplasia included both advanced serrated lesions and five or more precancerous lesions, making it difficult to directly compare with the other studies.11 Yen et al. found the prevalence of advanced neoplasia including serrated lesions in a population of predominantly male 45–49 year-olds with low-risk symptoms at a single Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center was 8.5%.15 We found a 6.2% advanced neoplasia prevalence among men in the same age group, which may indicate that the general population has a lower prevalence of risk factors for colorectal neoplasia compared to Veterans who receive care in the VA. The aforementioned four studies that assessed advanced neoplasia in average-risk individuals included approximately 430 cases of advanced neoplasia in the 45–49 year age group combined, compared to 3480 cases in this study. In addition to being the largest, our study included the most diverse population in terms of race and ethnicity and geographic residence. To our knowledge, this is also the first study to focus on average-risk individuals that found a statistically significant difference in advanced neoplasia prevalence between the 45–49 and 50–54 year age groups. Trivedi et al. examined approximately 25% of data reported to GIQuIC from 123 ambulatory endoscopy centers, but because their analysis included higher risk individuals with symptoms and a family history of advanced colorectal neoplasia, the prevalence of neoplasia they found was higher than in the present study and not representative of the average-risk screening population.16

Although the prevalence of neoplasia was lower for individuals younger than 50 years, the rate of change in the prevalence of both advanced neoplasia and adenomas appeared similar for individuals aged 40–49 years and 50–59 years (Figure 1). Furthermore, the prevalence of CRC in those aged 45–49 years (0.23%, PR 0.97, 95% CI 0.84–1.11) was no different than those aged 50–54 years (0.24%). A previous Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) analysis suggested that the abrupt increase in CRC incidence at age 50 years can be partially attributed to individuals with latent disease who are not diagnosed until they reach screening age.17 Our data corroborate this hypothesis and indicates that in the average-risk screening population, the yield of advanced neoplasia remains reasonably high in the 45–49 year age group. These findings support the new guidelines to initiate screening at age 45 years, which will likely result in a level of protection against CRC in this younger age group that is clinically comparable to the 50–54 year age group.

The GIQuIC data can also be used to establish quality benchmarks, such as the adenoma detection rate (ADR), for 45–49 year-olds joining the screening pool. Among average-risk individuals in this age group, adenoma prevalence or ADR was 23.5% in women, 34.4% in men, and 28.3% overall. This implies that the current ADR benchmarks of 20% for women, 30% for men, and 25% overall could be maintained for younger screening participants.13

Our findings also provide a useful reference for risk stratification in regions where colonoscopy capacity is limited. In such locales, screening colonoscopy could be reserved for persons at higher risk for advanced neoplasia based on factors such as age and sex, while other screening options such as fecal immunochemical testing could be used for individuals at lower risk. However, any effort to translate this data into more complex, risk-based screening algorithms must be carefully implemented to ensure equity across demographic groups.

An important finding of our study was the higher prevalence of advanced neoplasia and adenomas in White individuals compared to persons of most other racial and ethnic groups in those younger than 60 years. For advanced neoplasia, much of the difference was driven by the higher prevalence of advanced serrated lesions in White individuals (Supplemental Table 1), which is consistent with previous studies.18,19 However, studies have shown that the prevalence of the CpG island methylator phenotype—the CRC molecular pathway associated with serrated lesions—is lower in EOCRC than in late-onset CRC, suggesting serrated lesions are not the primary reason for the rise in EOCRC.20 Indeed, when serrated lesions were excluded and the outcome was restricted to advanced adenomas and CRC, White individuals still had slightly higher prevalence in those younger than 60 years while Black individuals had higher prevalence than White individuals in older age groups (Supplemental Table 2). A 2008 analysis by Lieberman et al. that used screening colonoscopy data from a consortium of 67 US practices found that Black individuals had a higher prevalence of large (>9 mm) polyps than White individuals across all age groups (7.7% vs. 6.2%, P < .001), even though the difference for those younger than 60 years was not statistically significant.21 Since the Lieberman et al. study used data from 2004–2005, our results suggest that the prevalence of neoplasia among younger adults has increased faster among White individuals than Black individuals in the past 15 years. This trend would parallel the trajectory of EOCRC, where the observed increase in incidence is primarily driven by White individuals.22,23 Furthermore, these findings provide evidence that the established precursor lesions and neoplasia pathways for CRC overall also apply to younger adults.

The regression models provide further evidence that White individuals have higher risk of neoplasia compared to persons of other racial and ethnic groups, even after adjusting for age, sex, family history, and BMI. For persons younger than 50 years, Black, Asian, and Hispanic individuals had 35%, 32%, and 16% lower risk of advanced neoplasia relative to White individuals, respectively. The same pattern held for older adults, except that Asian individuals had the lowest risk of advanced neoplasia and the protective effect for Black, Asian, and Hispanic persons was attenuated compared to younger adults. In the US, Black individuals have had the highest CRC incidence across all age groups since the 1980s,24 but there has been no difference in incidence between Black and White individuals younger than 50 years since 2014.25,26 If the odds ratios in our cross-sectional study of mostly precancerous lesions remain stable, we would expect the incidence of EOCRC in White individuals to surpass that of Black individuals over time. Incidence in adults aged 50 years and older remains higher in Black individuals,25 but our data suggests the gap between Black and White individuals will similarly narrow in this age group. Since our results show White individuals have an increased risk of neoplasia compared to Black individuals in both younger and older age groups, which is a striking change from the historical data, then the same factors responsible for the increase in CRC in younger White adults also likely explain the higher risk of neoplasia in older White adults. While an examination of the potential factors driving the rise in EOCRC are beyond the scope of this study, these findings imply that the racial and ethnic trends described in EOCRC are not confined to younger adults.

Of the five commonly available clinical factors we examined as potential predictors of colonic neoplasia, older age was the strongest predictor of advanced neoplasia and adenomas in both the younger and older groups. Compared to average-risk individuals aged 45–49 years, the prevalence of advanced neoplasia in 50–54 year-olds and 80–84 year-olds was 1.2-fold and 1.8-fold higher, respectively. Therefore, while the rise in EOCRC has appropriately focused a spotlight on younger adults, as the screening pool is expanded in the US it is imperative to remember that the absolute risk of neoplasia remains far higher in older adults.

There has been concern that lowering the screening age to 45 years may exacerbate disparities that disadvantage racial and ethnic minorities.27 The current data show that the proportion of non-White individuals receiving screening colonoscopy in the 45–49 year age group actually increased 3.8% from 2013 to 2020, and the majority of the increase occurred in 2020. This may have been prompted by the incremental adoption of the updated American Cancer Society guidelines as well as the death of Chadwick Boseman, which data suggest raised interest in CRC nationally and particularly in the Black community.28 However, longer term data that includes the period after the publication of the 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force guideline are needed to confirm this finding and to evaluate whether existing racial and ethnic disparities in screening are narrowing.

The strengths of this study include a very large sample size, geographic and racial and ethnic diversity of the population, and high data reliability when compared to the medical record. However, some limitations of the dataset should be acknowledged. First, GIQuIC is not truly a population-based database because each site participates voluntarily and pays an annual fee. Second, examining only the first colonoscopy for each individual would be ideal for determining neoplasia prevalence, but this information could not be determined in the database. However, we did restrict the analysis to the first screening colonoscopy for each individual at a participating site. Finally, the study could not assess the anatomic distribution of colorectal neoplasia by age because data on anatomic subsite were not collected.

In a large cross-sectional study of screening colonoscopies performed in US adults, the prevalence of advanced neoplasia in individuals aged 45–49 years was substantial. Although the prevalence in this age group was lower than in older age groups, these findings support recent guidelines to lower the screening age to 45 years. Since the prevalence of adenomas in these individuals exceeded current ADR benchmarks, it is reasonable to include this age group in ADR calculations. The proportion of non-White individuals undergoing screening colonoscopy among 45–49 year-olds increased over time. Finally, White individuals had higher risk of advanced neoplasia than Black, Hispanic, and Asian individuals in both younger and older adults, which indicates evolving racial and ethnic trends in CRC across the age spectrum.

Supplementary Material

What You Need to Know.

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

Colorectal cancer screening is recommended for average-risk individuals starting at age 45 years in the United States, but the prevalence of neoplasia in younger adults has not been thoroughly studied.

NEW FINDINGS

Among average-risk individuals aged 45–49 years who underwent screening colonoscopy in a national registry, advanced neoplasia prevalence was 5.0%. Whites had higher prevalence of advanced neoplasia than other racial/ethnic groups in most age groups.

LIMITATIONS

Although the registry is racially/ethnically and geographically diverse, the data is not population-based.

IMPACT

These findings support initiating screening at age 45 years, demonstrate current adenoma detection benchmarks are applicable in the 45–49 year age group, and may inform risk-based screening strategies.

Funding:

Funding for this study was provided by a ReMission Foundation grant to PSL. PSL is also supported by grant K08 CA230162 from the National Cancer Institute. The funding source had no role in the analysis of data, preparation of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures:

PSL has received research support from Epigenomics and Freenome and is on the advisory board for Guardant Health. The remaining authors have no disclosures.

Disclaimer:

This material is the result of work supported in part by resources from the Veterans Health Administration. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

Abbreviations:

- ADR

adenoma detection rate

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- EOCRC

early-onset colorectal cancer

- GIQuIC

GI Quality Improvement Consortium

- OR

odds ratio

- PR

prevalence ratio

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- SSL

sessile serrated lesion

- US

United States

- VA

Veterans Affairs

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santucci C, Boffetta P, Levi F, et al. Colorectal Cancer Mortality in Young Adults Is Rising in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, and Australia but Not in Europe and Asia. Gastroenterology 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterse EFP, Meester RGS, Siegel RL, et al. The impact of the rising colorectal cancer incidence in young adults on the optimal age to start screening: Microsimulation analysis I to inform the American Cancer Society colorectal cancer screening guideline. Cancer 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meester RGS, Peterse EFP, Knudsen AB, et al. Optimizing colorectal cancer screening by race and sex: Microsimulation analysis II to inform the American Cancer Society colorectal cancer screening guideline. Cancer 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knudsen AB, Rutter CM, Peterse EFP, et al. Colorectal Cancer Screening: An Updated Modeling Study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2021;325:1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2021;325:1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel SG, May FP, Anderson JC, et al. Updates on Age to Start and Stop Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations From the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2021:S0016–5085(21)03626-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolb JM, Hu J, DeSanto K, et al. Early-Age Onset Colorectal Neoplasia in Average-Risk Individuals Undergoing Screening Colonoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 2021:S0016–5085(21)03095-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butterly LF, Siegel RL, Fedewa S, et al. Colonoscopy Outcomes in Average-Risk Screening Equivalent Young Adults: Data From the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaukat A, Rex DK, Shyne M, et al. Adenoma detection Rates for 45–49 year old screening population. Gastroenterology 2021:S0016508521035289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.GIQuIC. GIQuIC Data Collection Form. Available at: https://giquic.gi.org/data-collection-form.asp [Accessed January 28, 2022].

- 13.Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients From the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2017;153:307–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yen T, Scolaro J, Montminy E, et al. Spectrum of Advanced Colorectal Neoplasia and Anticipated Yield of Average-Risk Screening in Veterans Under Age 50. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc 2021:S1542–3565(21)01229–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trivedi PD, Mohapatra A, Morris MK, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Young-Onset Colorectal Neoplasia: Insights from a Nationally Representative Colonoscopy Registry. Gastroenterology 2022:S0016–5085(22)00005–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abualkhair WH, Zhou M, Ahnen D, et al. Trends in Incidence of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer in the United States Among Those Approaching Screening Age. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e1920407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallace K, Burke CA, Ahnen DJ, et al. The association of age and race and the risk of large bowel polyps. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol 2015;24:448–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace K, Brandt HM, Bearden JD, et al. Race and Prevalence of Large Bowel Polyps Among the Low-Income and Uninsured in South Carolina. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:265–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perea J, Rueda D, Canal A, et al. Age at onset should be a major criterion for subclassification of colorectal cancer. J Mol Diagn JMD 2014;16:116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lieberman DA, Holub JL, Moravec MD, et al. Prevalence of colon polyps detected by colonoscopy screening in asymptomatic black and white patients. JAMA 2008;300:1417–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal Cancer Incidence Patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang SH, Patel N, Du M, et al. Trends in Early-onset vs Late-onset Colorectal Cancer Incidence by Race/Ethnicity in the United States Cancer Statistics Database. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc 2021:S1542–3565(21)00817-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. 2019. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016/[Accessed December 27, 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics [Internet]. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer/[Accessed December 27, 2021].

- 26.Montminy EM, Zhou M, Maniscalco L, et al. Trends in the Incidence of Early-Onset Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Among Black and White US Residents Aged 40 to 49 Years, 2000–2017. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2130433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang PS, Allison J, Ladabaum U, et al. Potential Intended and Unintended Consequences of Recommending Initiation of Colorectal Cancer Screening at Age 45 Years. Gastroenterology 2018;155:950–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naik H, Johnson MDD, Johnson MR. Internet Interest in Colon Cancer Following the Death of Chadwick Boseman: Infoveillance Study. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e27052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.