Abstract

A growing body of evidence suggests a potential link between child maltreatment and asthma. Determining whether and how child maltreatment causes or worsens asthma would have major implications for disease prevention and treatment, as well as public health policy. In this article, we examine epidemiologic studies of child maltreatment and asthma and asthma-related outcomes, review the evidence for potential mechanisms underlying the child maltreatment-asthma association, and discuss future directions. To date, a child maltreatment-asthma link has been reported in most studies of children and adults, though the type of maltreatment associated with asthma has differed across studies. Such discrepant findings are likely explained by differences in study design and quality. All studies have been limited by potential under-reporting of child maltreatment and selection bias, and nonthorough assessment of asthma. Despite these limitations, the aggregate evidence from epidemiologic studies suggests a possible causal link between child maltreatment and asthma, though the relative contributions of various types of maltreatment (physical, sexual, emotional, or neglect) are unclear. To date, there is insufficient evidence of an association between child maltreatment and lung function in children or adults. Limited evidence further suggests that child maltreatment could influence the development or severity of asthma through direct effects on stress responses and anxiety- or depressive-related disorders, immunity, and airway inflammation, as well as indirect effects such as increased obesity risk. Future prospective studies should aim to adequately characterize both child maltreatment and asthma, while also assessing relevant covariates and biomarkers of stress, immune, and therapeutic responses.

Keywords: adults, asthma, child maltreatment, children

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Asthma is the most common chronic lung disease among children worldwide,1 affecting ~7% of children in the United States.2 In this country, Puerto Rican and African American children share a disproportionate burden of asthma and are often exposed to violence at the individual, family, and community levels.3 Over the last two decades, both exposure to violence4–9 and chronic stress10–13 have been implicated in causing and worsening childhood asthma.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)14 can have a long lasting negative impact on physical and psychological health.15–21 Child maltreatment, a stressful ACE that may involve direct exposure to violence, is unfortunately a common problem: at least one in seven children in the United States have experienced child abuse or neglect in the past year, and this is likely an underestimate.22. Child maltreatment has been associated with chronic conditions and diseases such as asthma.15,23

Determining whether and how child maltreatment causes or worsens asthma could have major implications for the prevention and treatment of asthma across life stages, while also impacting public health policy. In this article, we examine findings from epidemiologic studies of child maltreatment and asthma and asthma-related outcomes, review the available evidence for potential mechanisms underlying the link between child maltreatment and asthma, and discuss future directions in this area. While it could be argued that adverse experiences like racism and gun violence are forms of child maltreatment that occur outside the home, this review is focused on child maltreatment in the traditional sense, encompassing physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect.22

2 |. CHILD MALTREATMENT, ASTHMA, AND ASTHMA-RELATED OUTCOMES

2.1 |. Asthma in children

Child maltreatment was first reported to be associated with pediatric asthma in a cross-sectional study of 1213 Puerto Ricans aged 6–16 years living in the metropolitan area of San Juan and Caguas (Puerto Rico).24 In the year before that study, 14% of participating children had witnessed an act of violence, 7% had been victims of violence, and 6% had been victims of physical or sexual abuse. Compared with children without a history of physical or sexual abuse, those with a history of physical or sexual abuse had a higher prevalence of current asthma (50% vs. 39%). In a multivariable analysis adjusting for age, parental history of asthma, and annual household income, physical, or sexual abuse was associated with significantly increased odds of current asthma (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.3–5.0]) and medication use for asthma (aOR = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.1–5.3).24 Similar findings were reported in a subsequent cross-sectional study of 1413 subjects aged 16–27 years old in New Zealand, in which child maltreatment was defined as a history of involvement by a child protection agency (extracted from a national database).25 In that study, child maltreatment was significantly associated with a lifetime diagnosis of asthma, even after adjusting for socioeconomic status (SES), lifetime mental disorders, body mass index (BMI), and lifetime smoking (aOR = 2.3, 95% CI = 1.3–3.8).25 In a secondary analysis, self-reported child maltreatment was not significantly associated with lifetime asthma, a negative finding that could be explained by recall bias in a study of adolescents and young adults.

Asthma is a syndrome comprising various phenotypes such as atopic asthma and nonatopic asthma. A cross-sectional study of 1370 Brazilian children aged 4–12 years examined the relation between intrafamilial violence and asthma symptoms according to atopy (defined as an IgE ≥0.70 IU/ml to ≥1 common allergen).26 In a multivariable analysis adjusting for second-hand smoke, maternal education, living conditions, and other covariates, maltreatment through nonviolent discipline (aOR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.2–3.2) and maltreatment through violent discipline (aOR = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.0–2.2) were associated with nonatopic asthma symptoms. Although child maltreatment was not associated with atopic asthma symptoms, there was a limited assessment of asthma and atopy may have been misclassified due to the small number of allergens tested and the threshold used for a positive IgE (i.e., ≥0.70 IU/ml instead of ≥0.35 IU/ml).

Children born to mothers who experienced traumatic events during adulthood, including intimate partner violence (IPV),27,28 domestic violence,29 or interpersonal trauma30 may be at increased risk of incident asthma. With regard to maternal history of child maltreatment, a Canadian prospective cohort study followed 1551 (45.8%) of 3388 mother–child pairs for 2 years after birth.31 In that study, children born to mothers who self-reported a history of childhood abuse were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with asthma by age 2 years than children born to mothers without a history of childhood abuse, even after accounting for maternal education, maternal race, household income, parity, and the child’s sex (aOR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.0–3.4).31 Of note, maternal symptoms of depression assessed in late pregnancy and maternal symptoms of depression and anxiety at 24 months postpartum were both significant mediators of the association between maternal child maltreatment and childhood asthma, but such mediation effects were not quantified.31 In a separate prospective cohort study conducted in Brisbane (Australia), 3762 (52.1%) of 7223 mother–child dyads enrolled at a baseline visit were followed up to 21 years after birth. Of the 3762 participating youth, 130 (3.5%) had experienced any child maltreatment (substantiated by a child protection agency) up to age 14 years and 1274 (33.9%) had ever been diagnosed with asthma by a physician.32 Of the various types of child maltreatment, only emotional abuse was significantly associated with lifetime physician-diagnosed asthma after adjustment for maternal age, in utero smoking, current smoking, BMI, and other confounders (aOR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.0–2.5). Although there was a trend for a dose–response relationship between the number of child maltreatment events and lifetime asthma, this was not statistically significant in a multivariable analysis (p = 0.06).

2.2 |. Asthma in adults

Child maltreatment has also been associated with asthma in adults. A cross-sectional study of 18,303 adults from 10 different countries in the United States of America, Europe, and Japan showed that self-reported physical abuse before age 18 years was significantly associated with self-reported physician-diagnosed asthma after age 20 years, even after accounting for age, sex, study site, and current smoking (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.3–2.8).33 In that study, there was a dose–response relationship between ACEs (including but not limited to physical or sexual abuse) and asthma after age 20 years.33 Similar findings for physical abuse were reported in a cross-sectional study of 400 adults ages 40–60 years in Saudi Arabia, in which a self-reported history of being beaten at home during childhood was associated with a diagnosis of asthma.34 In contrast, a cross-sectional study of 3000 women in New Zealand found that self-reported sexual (but not physical) abuse before age 16 years was significantly associated with asthma in the previous year, though the analysis was not adjusted for potential confounders (unadjusted OR = 2.3, 95% CI = 1.1–4.8).35 In a separate cross-sectional study of 3081 pregnant women in Peru, neither self-reported physical abuse nor self-reported sexual abuse during childhood was significantly associated with self-reported asthma at or after age 18 years.36 However, women who reported three or more abuse events (physical or sexual) during childhood had 1.9 times significantly increased odds of asthma (95% CI for aOR = 1.1–3.3), even after accounting for BMI, difficulty paying for basics, education, smoking history, and alcohol consumption history.36

Potential mediators of the observed association between child maltreatment and asthma in adults include cigarette smoking and mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety. In a recent cross-sectional study of British adults older than 40 years, 157,366 (46%) of 339,092 participants who were invited to complete an online mental health questionnaire emailed their responses.37 Of those 157,366, 120,732 were eligible for inclusion in the study; 81,105 (67.2%) of the 120,732 eligible subjects had complete data on all relevant covariates and were included in the primary analysis. In a multivariable analysis, self-report of any child maltreatment was associated with self-report of current physician-diagnosed asthma (aOR = 1.2, 95% CI = 1.1–1.3). In a mediation analysis adjusted for household income, educational attainment, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, and other covariates, lifetime generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and lifetime major depressive disorder (MDD) explained 21.8% and 32.5%, respectively, of the child maltreatment-current asthma association. Similar results were obtained after excluding current smokers and former smokers with ≥10 pack-years of smoking from the mediation analysis, suggesting that GAD and MDD mediate an association between child maltreatment and asthma in adults, independently of smoking. Those findings were essentially unchanged in a sensitivity analysis including all 120,732 eligible subjects after imputation of missing data.

A prospective cohort study of African American women aged 21–59 years examined the relation between self-reported child maltreatment and incident (new-onset) asthma during 14 years of follow-up.38 Of the 59,009 participants, 54,886 subjects did not report asthma of childhood onset and had no asthma diagnosed before the baseline visit. Of those 54,886 eligible subjects, 28,456 (52%) were included in the primary analysis. During 417,931 person-years of follow-up, 1160 participants reported incident asthma (defined as physician-diagnosed asthma and concurrent use of asthma medication). Compared with women who experienced no abuse during childhood or adolescence, the adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR) for any childhood abuse was 1.2 (95% CI = 1.1–1.5), and 1.1 for any adolescent abuse (95% CI = 0.9–1.4). This association was stronger for childhood physical abuse (aIRR = 1.3 95% CI = 1.1–1.5) than for childhood sexual abuse (aIRR = 1.2, 95% CI = 0.9–1.5). Of interest, the observed associations were stronger in women who were older than 40 years than in younger women.38

A separate 1-year prospective study of 668 predominantly non-Hispanic white (81%) and African American (19%) adolescents aged 12–18 years living in western Pennsylvania examined the relation between traumatic events (including child abuse) and health-related symptoms in 15 areas, including “heart and lung.”39 Although there was no association between traumatic events and self-reported asthma, that study was limited by loss of follow-up for 113 (17%) of the 668 participants, limited statistical power, unclear assessment or definition of asthma, and noninclusion of neglect as a form of child abuse.39

2.3 |. Lung function

In a recent 48-week longitudinal study of data from 98 diverse youth aged 6–16 years who were treated with low-dose inhaled corticosteroids for mild persistent asthma,40 increased distress related to exposure to violence (including but not limited to child abuse) was associated with significant decrements in percent predicted (%pred) forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) (−3.27% for each 1-point increment in a validated scale, with 95% CI = −6.44% to −0.22%) and %pred forced vital capacity (FVC) and reduced asthma-related quality of life. In that report, increased violence-related distress was also significantly associated with reduced FEV1 and FVC in an ~5-year prospective study of 232 Puerto Rican youth aged 6–14 years.40 Taken together, those results suggest that increased violence-related distress between childhood and adolescence leads to reduced FEV1 and FVC in subjects with asthma, and that this may be partly explained by reduced sensitivity to inhaled steroids.40

In contrast to findings for violence-related distress in youth with asthma, there has been no or inconsistent association between child maltreatment and reduced lung function in studies of children32 and adults41,42 in the general population. In an Australian prospective cohort study of children followed from birth until age 21 years, child maltreatment was not associated with decrements in FVC, FEV1, or forced expiratory flow mid expiratory phase (FEF25–75).32 However, that study was limited by plausible selection bias due to substantial loss of follow-up (~48%) and potential under-reporting of child maltreatment (as only 3.5% of subjects had an event captured by a child protection agency).32 In a cross-sectional study of German adults older than 20 years, child maltreatment was significantly associated with asthma attacks, medication use for asthma, and asthma symptoms (e.g., wheeze without a cold), but not with FVC, FEV1, or FEV1/FVC.41 However, only 1386 (32.2%) of the original 4308 study participants were included in the analysis, which was not adjusted for medication use or disease status (e.g., asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]).41

In a case-control study nested within a prospective study, child maltreatment was defined as cases of physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect captured by the judicial system of an US mid-Western metropolitan area by age 11 years.42 After mean follow-up of ~30 years, neglect—but not physical or sexual abuse—was significantly associated with a reduced peak air flow, even after accounting for SES indicators, mental illness, smoking, and other covariates (aOR = 4.0, 95% CI = 1.1–15.3).42

2.4 |. Asthma hospitalizations

In a study of administrative data for 6262 predominantly Black children of low SES who lived in a mid-Western metropolitan area in the United States and were followed for an average of 16 years, any report of child maltreatment (abuse or neglect) was significantly associated with increased risk of a hospitalization for asthma during follow-up, even after accounting for parental education, census-level indicators of SES, parental mental illness, and other covariates (aHR = 1.7, 95% CI = 1.5–2.0).43 Given a database-driven design, that study was limited by nonadjustment for potential confounders at the individual level (e.g., smoking, household income).

2.5 |. Summary

Table 1 shows the main results of 12 published studies of child maltreatment and asthma in children (n = 4) and adults (n = 8, though one study included adolescents). Of these 12 studies, 9 have been cross-sectional and 3 have been longitudinal. Although the type of child maltreatment (e.g., physical vs. sexual, self-reported vs. extracted from a database) associated with asthma differs across studies, all showed at least one association between child maltreatment (any, one type, or a threshold such as at least three events) and asthma, with some studies reporting a clear dose–response relationship.

TABLEE 1.

Summary of results from published studies on child maltreatment and asthma

| References | Study population | Main findings |

|---|---|---|

| Studies in children | ||

| Cross-sectional | ||

| Cohen et al.24 | 1213 Puerto Rican children aged 5–13 years living in San Juan (PR) | As reported by the participating children, physical, or sexual abuse in the previous year was associated with current asthma (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.3–5.0) and medication use for asthma. |

| Bonfim et al.26 | 1370 Brazilian children aged 4–12 years living in Bahia (Brazil) | Among nonatopic children, maternal report of intrafamilial violence was associated with nonatopic asthma symptoms in the prior year (aOR for maltreatment with nonviolent discipline = 1.95, 95% CI = 1.2–3.2, and aOR for maltreatment with violent discipline = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.0–2.2). Among atopic children, maternal report of intrafamilial violence was not associated with asthma symptoms in the prior year. |

| Longitudinal | ||

| Lanier et al.43 | 6282 children living in a mid-Western US city who were followed for 12–18 years using data from administrative systems | Any report of child maltreatment before age 12 years was associated with increased risk of a hospitalization for asthma during follow-up (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.5–2.0). |

| Abajobir et al.32 | 3762 Australian subjects followed from birth until age 21 years | Any report of emotional abuse (aOR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.0–2.5) or neglect (aOR = 1.7, 95% CI = 1.0–2.8) was associated with lifetime asthma by age 21 years. Reports of other types of abuse (physical or sexual) were not associated with lifetime asthma by age 21 years. Childhood abuse was not associated with lung function. |

| Studies in adults | ||

| Cross-sectional | ||

| Romans et al.35 | 3000 women in New Zealand | In an unadjusted analysis, self-reported sexual abuse before age 16 years (n = 173) was associated with 2.3 times increased odds of asthma in the previous year (95% CI = 1.1–4.8) with nonsignificant results for self-reported physical abuse (n = 31, OR = 2.0, 95% CI = 0.7–5.7). |

| Scott et al.33 | 18,003 adults from 10 countries in the United States of America, Europe, and Japan | Self-reported physical abuse before age 18 years was associated with physician-diagnosed asthma after age 20 years (aHR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.3–2.8). A dose-response relationship was shown for an association between adverse childhood events (including but not limited to physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect) and adult-onset asthma. Self-reported sexual abuse or neglect was not associated with adult-onset asthma. |

| Scott et al.25 | 1413 adolescents and young adults, aged 16–27 years, living in New Zealand | Report of any maltreatment before age 17 years, extracted from a national database, was associated with lifetime asthma (aOR = 2.3, 95% CI = 1.3–3.8). Self-reported child maltreatment was not associated with lifetime asthma. |

| Hyland et al.34 | 400 adults aged 40–60 years living in Saudi Arabia | Self-reported physical abuse (being beaten once or more per month) during childhood was associated with 1.7 times increased risk for asthma (p < 0.05, 95% CI not provided). |

| Banerjee et al.36 | 3081 pregnant women in Peru | Neither (self-reported) physical or sexual abuse during childhood was associated with self-reported adult-onset asthma. However, having experienced at least three abuse events (physical or sexual) was associated with adult-onset asthma (aOR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.1–3.3). |

| Spitzer et al. 41 | 1386 German adults 20 years and older | Self-reported child maltreatment was associated with medication use for asthma (aOR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.1–3.3), asthma attacks (aOR = 4.1, 95% CI = 1.4–12.2), and “asthma or chronic bronchitis” (aOR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.0–2.6), but not with lung function. |

| Han et al.37 | 81,105 British adults older than 40 years | Self-reported child maltreatment was associated with current physician-diagnosed asthma (aOR = 1.2, 95% CI = 1.1–1.3) with a significant dose-relationship shown for the number of child maltreatment events and asthma. In a multivariable mediation analysis, lifetime generalized anxiety disorder and lifetime major depressive disorder explained 21.8% and 32.5%, respectively, of the observed child maltreatment-current asthma association. |

| Longitudinal | ||

| Coogan et al.38 | 28,456 African American women aged 21–59 years followed for 14 years | Compared with women who reported no abuse during childhood or adolescence, any childhood abuse was associated with 1.2 times increased risk of new-onset (incident) asthma during follow-up (95% CI for adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR] = 1.1–1.5). This association was slightly stronger and more significant for physical abuse (aIRR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.1–1.5) than for sexual abuse (aIRR = 1.2, 95% CI = 0.9–1.5). |

Discrepant findings are likely explained by differences in study design and quality. Unlike prospective studies, cross-sectional studies cannot assess temporal relationships and exclude “reverse causation” (i.e., if children with asthma were more likely to be abused). All studies have been limited by potential under-reporting of child abuse, as self-report is subject to recall bias and information extracted from databases (e.g., child protection agencies) may miss nonreported and less severe events. Similarly, selection bias cannot be excluded as an alternative explanation in most studies, whether cross-sectional or prospective (the latter resulting from differential loss of follow-up related to child maltreatment and asthma). Moreover, asthma may have been misclassified in studies of young children (who may have had transient wheeze) and smoking adults (who may have COPD), as most studies have relied on self-report from questionnaires. In addition, most studies have classified childhood- versus adult-onset asthma based on retrospective assessments.

Despite all the limitations listed above, the consistency of the overall findings for any child maltreatment and asthma suggests a potential causal relationship, which warrants follow-up in future longitudinal studies with further characterization of asthma phenotypes and endotypes.

To date, there is insufficient and weak evidence of an association between child maltreatment and lung function in children or adults, though a recently reported association between violence-related distress and childhood lung function,40 together with findings for asthma attacks and asthma hospitalizations41,43 support a possible link between child maltreatment and greater asthma severity.

3 |. POTENTIAL MECHANISMS

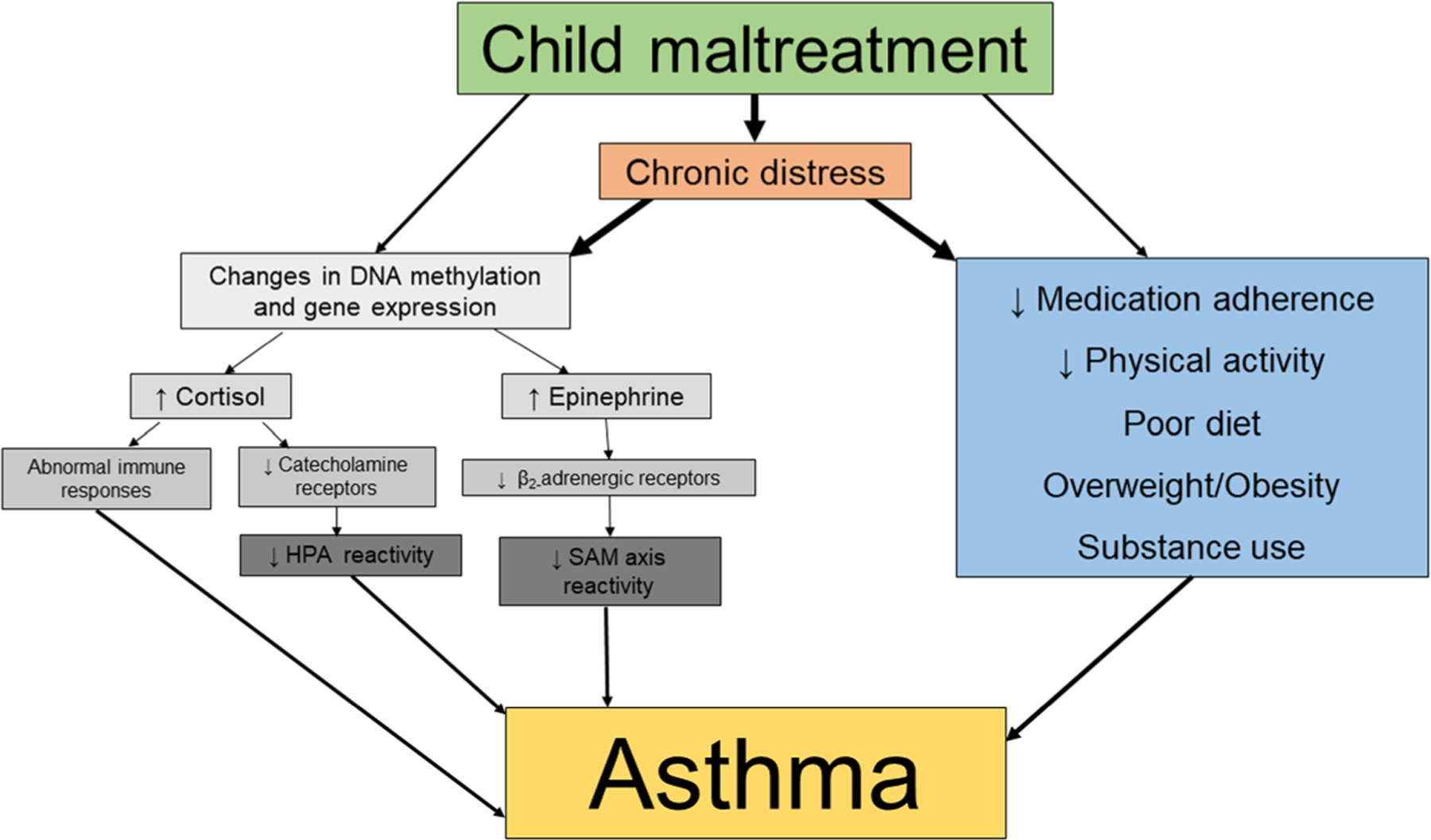

Psychosocial stressors such as child maltreatment could influence the development or severity of asthma through direct and indirect effects3,13 (Figure 1). Child maltreatment leads to chronic distress, which may affect methylation and expression of genes that regulate physiologic responses to stress,44 including those mediated by the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, the sympathetic–adrenal–medullary axis, and the autonomic nervous system.45 Chronic alteration of stress responses, including increased circulating levels of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine can in turn lead to downregulation of receptors and decreased HPA axis responsiveness, abnormal immune responses, and a reduced response to asthma therapies such as short-acting bronchodilators and corticosteroids.45–50 Moreover, child maltreatment has been linked to the development of depressive and anxiety disorders,51 which have been shown to increase the risk of incident asthma in adults.33,52,53 Indeed, GAD and MDD were recently shown to be significant mediators of the association between child maltreatment and asthma in adults (see above).37 Chronic stress from child maltreatment could also impact asthma through indirect mechanisms such as reduced adherence with controller medications, poor diet and decreased physical activity, overweight or obesity, and substance use.13 Further, children who experience maltreatment could be coexposed to other risk factors such as outdoor air pollution, which may have synergistic detrimental effects on asthma.

FIGURE 1.

Potential direct and indirect effects of child maltreatment on asthma

To our knowledge, there have been no experimental studies of the effects of child maltreatment on physiologic responses to stress or immune responses. However, indirect evidence for such effects is provided by two studies of other types of intrafamilial conflict or violence. The first study examined parent–child conflict and expression of the genes for the glucocorticoid receptor (NR3C1) and the β2-adrenergic receptor (ADRB2) in white blood cells (WBCs) from 57 Canadian children with asthma.54 Parent–child pairs participated in a conflict task, and coders rated interactions for evidence of harsh and supportive behaviors. In that study, harsh conflict behaviors were associated with lower expression levels of NR3C1 and ADRB2 in WBCs, as well as more asthma symptoms in participating children. Of note, most participants were atopic,54 limiting the generalizability of those findings to children with nonatopic asthma. The second study examined exposure to maternal IPV and HPA axis reactivity and asthma during early childhood in 1292 low-income, predominantly non-Hispanic white (59%) children from the US Northeast.55 Salivary cortisol samples were collected from participating children with validated stress reactivity paradigms at ages 7, 15, 24, 35, and 48 months old, when maternal reports of IPV were also obtained. Maternal exposure to IPV when the child was 7 months old was associated with subsequent reports of childhood asthma, but this association differed according to the child’s HPA reactivity status: IPV-exposed children who were “cortisol reactors” (~43% of participants) were at significantly increased risk of asthma at ages 7 months (β = 0.17, p = 0.02) and 15 months (β = 0.17, p = 0.02). Although asthma cannot be accurately diagnosed in early childhood, those findings suggest that young children who are physiologically reactive may have increased risk of asthma- or wheeze-related outcomes when exposed to stressors such as IPV.55

4 |. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Child maltreatment is a highly sensitive but potentially important risk factor for asthma. To overcome the limitations of previous work, large studies with a prospective design should examine both the number and types of child maltreatment from early life to adolescence, including child and medical neglect (e.g., nonadherence with treatment, poor nutrition, and lack of exercise), which may worsen asthma control.56

Accurate detection of all cases is unlikely, and thus assessing child maltreatment using high-quality databases from child protection agencies could capture most moderate to severe events while ensuring that affected children are provided with compassionate care and appropriate follow-up. An alternative approach would be to use self-reported maltreatment by the child’s parents, but this is suboptimal and would likely lead to reporting and selection biases, as the child’s parent would have to be informed of the potential need for referral to child protective services during the informed consent process. Indeed, findings from studies of exposure to violence in older children suggest substantial under-reporting by their parents.57,58

In parallel with assessment of child maltreatment, future studies should adequately characterize asthma phenotypes (e.g., “obese asthma,” childhood- vs. adult-onset) and endotypes (e.g., Th2-high vs. non-Th2 high asthma). Because asthma cannot be appropriately diagnosed before age 6 years, a high retention of study participants into adolescence and adulthood will require appropriate strategies to avoid loss of follow-up. Moreover, such studies should obtain data on covariates that may confound or modify the relationship between child maltreatment and asthma (e.g., outdoor air pollution, second-hand smoke, obesity, mental illness) while also examining biomarkers of HPA reactivity, immunity, and inflammatory and treatment responses to yield novel insights into the mechanisms underlying the child maltreatment-asthma link. Given that child maltreatment may worsen asthma,24,41 future studies should also include objective measures of asthma control and asthma severity (e.g., bronchodilator or airway responsiveness and scales from validated questionnaires).

The need for further research does not preclude much needed public health policies to prevent child maltreatment and its negative consequences for children with and without asthma. Moreover, current evidence supports screening for child maltreatment and associated mental illnesses (e.g., GAD, MDD, and posttraumatic stress disorder) in adolescents and adults with or at risk for asthma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants HL117191, MD011764, and HL152475 (PI: J. C. Celedón) from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. K. Gaietto is supported by an institutional training grant from the US NIH (T32 HL129949).

Funding information

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: HL117191, HL152475, MD011764, T32 HL129949

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Celedón has received research materials from GSK and Merck (inhaled steroids) and Pharmavite (vitamin D and placebo capsules), to provide medications free of cost to participants in NIH-funded studies, unrelated to the current work. The remaining author declares no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Serebrisky D, Wiznia A. Pediatric asthma: a global epidemic. Ann Glob Heal. 2019;85(1), doi: 10.5334/aogh.2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Data. CDC. 2021. Accessed August 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm

- 3.Landeo-Gutierrez J, Forno E, Miller GE, Celedón JC. Exposure to violence, psychosocial stress, and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):917–922. doi: 10.1164/RCCM.201905-1073PP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han YY, Forno E, Celedón JC. Health risk behaviors, violence exposure, and current asthma among adolescents in the United States. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54(3):237–244. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eldeirawi K, Kunzweiler C, Rosenberg N, et al. Association of neighborhood crime with asthma and asthma morbidity among Mexican American children in Chicago, Illinois. Ann Allergy, Asthma, Immunol. 2016;117(5):502–507.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.09.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sternthal MJ, Jun HJ, Earls F, Wright RJ. Community violence and urban childhood asthma: a multilevel analysis. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(6):1400–1409. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00003010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramratnam SK, Han YY, Rosas-Salazar C, et al. Exposure to gun violence and asthma among children in Puerto Rico. Respir Med. 2015;109(8):975–981. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berz JB, Carter AS, Wagmiller RL, Horwitz SM, Murdock KK, Briggs-Gowan M. Prevalence and correlates of early onset asthma and wheezing in a healthy birth cohort of 2- to 3-year olds. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(2):154–166. doi: 10.1093/JPEPSY/JSJ123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haavet O, Straand J, Saugstad O, Grünfeld B. Illness and exposure to negative life experiences in adolescence: two sides of the same coin? A study of 15-year-olds in Oslo, Norway. Acta Pædiatrica. 2004;93(3):405–411. doi: 10.1111/J.1651-2227.2004.TB02970.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunton G, Dzubur E, Li M, Huh J, Intille S, McConnell R. Momentary assessment of psychosocial stressors, context, and asthma symptoms in hispanic adolescents. Behav Modif. 2016;40(1–2):257–280. doi: 10.1177/0145445515608145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han YY, Forno E, Brehm JM, et al. Diet, interleukin-17, and childhood asthma in Puerto Ricans. Ann Allergy, Asthma, Immunol. 2015;115(4):288–293. e1 doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oren E, Gerald L, Stern DA, Martinez FD, Wright AL. Self-reported stressful life events during adolescence and subsequent asthma: a longitudinal study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(2): 427–434.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landeo-Gutierrez J, Celedón JC. Chronic stress and asthma in adolescents. Ann Allergy, Asthma, Immunol. 2020;125(4):393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson EC, Heath AC, Madden PAF, et al. Association between self-reported childhood sexual abuse and adverse psychosocial outcomes: results from a twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(2): 139–145. doi: 10.1001/ARCHPSYC.59.2.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chanlongbutra A, Singh GK, Mueller CD. Adverse childhood experiences, health-related quality of life, and chronic disease risks in rural areas of the United States. J Environ Public Health. 2018;2018:7151297. doi: 10.1155/2018/7151297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Heal. 2017;2(8):e356–e366. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, et al. Vital signs: estimated proportion of adult health problems attributable to adverse childhood experiences and implications for prevention—25 states, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(44):999–1005. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.MM6844E1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhan N, Glymour MM, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Childhood adversity and asthma prevalence: evidence from 10 US states (2009–2011). BMJ Open Respir Res. 2014;1(1), doi: 10.1136/BMJRESP-2013-000016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott KM, Korff MVon, Angermeyer MC, et al. Association of childhood adversities and early-onset mental disorders with adult-onset chronic physical conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8): 838–844. doi: 10.1001/ARCHGENPSYCHIATRY.2011.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and sources of childhood resilience: a retrospective study of their combined relationships with child health and educational attendance. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):792. doi: 10.1186/S12889-018-5699-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fast Facts: Preventing Child Abuse & Neglect.Violence Prevention, Injury Center. CDC. 2021. Accessed January 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/fastfact.html

- 23.Strathearn L, Giannotti M, Mills R, Kisely S, Najman J, Abajobir A. Long-term cognitive, psychological, and health outcomes associated with child abuse and neglect. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e20200438. doi: 10.1542/PEDS.2020-0438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen RT, Canino GJ, Bird HR, Celedón JC. Violence, abuse, and asthma in Puerto Rican children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(5):453–459. doi: 10.1164/RCCM.200711-1629OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott KM, Smith DAR, Ellis PM. A population study of childhood maltreatment and asthma diagnosis: differential associations between child protection database versus retrospective self-reported data. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(8):817–823. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0B013E3182648DE4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonfim CB, dos Santos DN, Barreto ML. The association of intrafamilial violence against children with symptoms of atopic and non-atopic asthma: a cross-sectional study in Salvador, Brazil. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;50:244. doi: 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2015.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gartland D, Conway LJ, Giallo R, et al. Intimate partner violence and child outcomes at age 10: a pregnancy cohort. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:1066–1074. doi: 10.1136/ARCHDISCHILD-2020-320321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suglia SF, Duarte CS, Sandel MT, Wright RJ. Social and environmental stressors in the home and childhood asthma. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(7):636–642. doi: 10.1136/JECH.2008.082842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subramanian SV, Ackerson LK, Subramanyam MA, Wright RJ. Domestic violence is associated with adult and childhood asthma prevalence in India. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(3):569–579. doi: 10.1093/IJE/DYM007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunst KJ, Rosa MJ, Jara C, et al. Impact of maternal lifetime interpersonal trauma on children’s asthma: mediation through maternal active asthma during pregnancy. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(1):91–100. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomfohr-Madsen LM, Bayrampour H, Tough S. Maternal history of childhood abuse and risk of asthma and allergy in 2-year-old children. Psychosom Med. 2016;78(9):1031–1042. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abajobir AA, Kisely S, Williams G, Strathearn L, Suresh S, Najman JM. The association between substantiated childhood maltreatment, asthma and lung function: a prospective investigation. J Psychosom Res. 2017;101:58–65. doi: 10.1016/J.JPSYCHORES.2017.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott KM, Korff MVon, Alonso J, et al. Childhood adversity, early-onset depressive/anxiety disorders, and adult-onset asthma. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(9):1035–1043. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0B013E318187A2FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyland ME, Alkhalaf AM, Whalley B. Beating and insulting children as a risk for adult cancer, cardiac disease and asthma. J Behav Med. 2013;36(6):632–640. doi: 10.1007/S10865-012-9457-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romans S, Belaise C, Martin J, Morris E, Raffi A. Childhood abuse and later medical disorders in women. An epidemiological study. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71(3):141–150. doi: 10.1159/000056281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banerjee D, Gelaye B, Zhong QY, Sanchez SE, Williams MA. Childhood abuse and adult onset asthma among Peruvian women. J Asthma. 2018;55(4):430–436. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2017.1339243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han Y-Y, Yan Q, Chen W, Celedón JC. Child maltreatment, anxiety and depression, and asthma among British adults in the UK Biobank. Eur Respir J. Published online March 17, 2022. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03160-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coogan PF, Wise LA, O’Connor GT, Brown TA, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Abuse during childhood and adolescence and risk of adult-onset asthma in African American women. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(4):1058–1063. doi: 10.1016/J.JACI.2012.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark DB, Thatcher DL, Martin CS. Child abuse and other traumatic experiences, alcohol use disorders, and health problems in adolescence and young adulthood. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(5):499. doi: 10.1093/JPEPSY/JSP117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaietto K, Han Y-Y, Forno E, et al. Violence-related distress and lung function in two longitudinal studies of youth. Eur Respir J. 2021;59:2102329. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02329-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spitzer C, Ewert R, Völzke H, et al. Childhood maltreatment and lung function: findings from the general population. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(4):2002882. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02882-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Bentley T, Johnson MS. A prospective investigation of physical health outcomes in abused and neglected children: new findings from a 30-year follow-up. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(6):1135–1144. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lanier P, Jonson-Reid M, Stahlschmidt MJ, Drake B, Constantino J. Child maltreatment and pediatric health outcomes: a longitudinal study of low-income children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(5):511. doi: 10.1093/JPEPSY/JSP086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenberg SL, Miller GE, Brehm JM, Celedón JC. Stress and asthma: novel insights on genetic, epigenetic, and immunologic mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen E, Miller GE. Stress and inflammation in exacerbations of asthma. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(8):993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forsythe P, Ebeling C, Gordon JR, Befus AD, Vliagoftis H. Opposing effects of short- and long-term stress on airway inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(2):220–226. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200307-979OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller GE, Chen E. Life stress and diminished expression of genes encoding glucocorticoid receptor and β2-adrenergic receptor in children with asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(14): 5496–5501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506312103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brehm JM, Ramratnam SK, Tse SM, et al. Stress and bronchodilator response in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(1):47–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201501-0037OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palumbo ML, Prochnik A, Wald MR, Genaro AM. Chronic stress and glucocorticoid receptor resistance in asthma. Clin Ther. 2016;42: 993–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Juruena MF, Eror F, Cleare AJ, Young AH. The role of early life stress in HPA axis and anxiety. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:141–153. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9705-0_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gardner MJ, Thomas HJ, Erskine HE. The association between five forms of child maltreatment and depressive and anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;96:104082. doi: 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2019.104082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brunner WM, Schreiner PJ, Sood A, Jacobs DR. Depression and risk of incident asthma in adults. The CARDIA study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(9):1044–1051. doi: 10.1164/RCCM.201307-1349OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De La Hoz RE, Jeon Y, Miller GE, Wisnivesky JP, Celedón JC. Post-traumatic stress disorder, bronchodilator response, and incident asthma in World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(11):1383–1391. doi: 10.1164/RCCM.201605-1067OC/SUPPL_FILE/DISCLOSURES.PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ehrlich KB, Miller GE, Chen E. Harsh parent–child conflict is associated with decreased anti-inflammatory gene expression and increased symptom severity in children with asthma. Dev Psychopathol. 2015;27(4, pt 2):1547–1554. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bair-Merritt MH, Voegtline K, Ghazarian SR, et al. Maternal intimate partner violence exposure, child cortisol reactivity and child asthma. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;48:50–57. doi: 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knox BL, Luyet FM, Esernio-Jenssen D. Medical neglect as a contributor to poorly controlled asthma in childhood. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2020;13:327–334. doi: 10.1007/s40653-019-00290-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richters JE, Martinez P. The NIMH community violence project: I. Children as victims of and witnesses to violence. Psychiatry. 2016;56(1):7–21. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Brien M, John RS, Margolin G, Erel O. Reliability and diagnostic efficacy of parents’ reports regarding children’s exposure to marital aggression. Violence Vict. 1994;9(1):45–62. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.9.1.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]