Abstract

Purpose

We investigated whether artificial intelligence (AI)-based denoising halves PET acquisition time in digital PET/CT.

Methods

One hundred ninety-five patients referred for [18F]FDG PET/CT were prospectively included. Body PET acquisitions were performed in list mode. Original “PET90” (90 s/bed position) was compared to reconstructed ½-duration PET (45 s/bed position) with and without AI-denoising, “PET45AI and PET45”. Denoising was performed by SubtlePET™ using deep convolutional neural networks. Visual global image quality (IQ) 3-point scores and lesion detectability were evaluated. Lesion maximal and peak standardized uptake values using lean body mass (SULmax and SULpeak), metabolic volumes (MV), and liver SULmean were measured, including both standard and EARL1 (European Association of Nuclear Medicine Research Ltd) compliant SUL. Lesion-to-liver SUL ratios (LLR) and liver coefficients of variation (CVliv) were calculated.

Results

PET45 showed mediocre IQ (scored poor in 8% and moderate in 68%) and lesion concordance rate with PET90 (88.7%). In PET45AI, IQ scores were similar to PET90 (P = 0.80), good in 92% and moderate in 8% for both. The lesion concordance rate between PET90 and PET45AI was 836/856 (97.7%), with 7 lesions (0.8%) only detected in PET90 and 13 (1.5%) exclusively in PET45AI. Lesion EARL1 SULpeak was not significantly different between both PET (P = 0.09). Lesion standard SULpeak, standard and EARL1 SULmax, LLR and CVliv were lower in PET45AI than in PET90 (P < 0.0001), while lesion MV and liver SULmean were higher (P < 0.0001). Good to excellent intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) between PET90 and PET45AI were observed for lesion SUL and MV (ICC ≥ 0.97) and for liver SULmean (ICC ≥ 0.87).

Conclusion

AI allows [18F]FDG PET duration in digital PET/CT to be halved, while restoring degraded ½-duration PET image quality. Future multicentric studies, including other PET radiopharmaceuticals, are warranted.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00259-022-05800-1.

Keywords: [18F]FDG, PET, Denoising, Artificial intelligence, Deep learning, Acquisition time

Introduction

Recent research in PET has focused on decreasing noise and increasing signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) [1]. Digital PET with silicon photomultipliers (SiPM) has led to improved timing, energy, spatial resolution, and effective time-of-flight (TOF) sensitivity [2–5]. This has resulted in faster scanning with less injected activity [1]. However, despite these advances, there is an ever-increasing demand for PET scans, which can contribute to significant delays in scheduling examinations and patient management.

Deep learning (DL), a subdivision of artificial intelligence (AI), has many emerging applications in nuclear medicine [6, 7]. DL is able to increase PET resolution, decrease noise, and thus enhance image quality [8–12]. It may allow for reducing injected activity, acquisition time, or a combination of both [10, 13–21].

DL-based denoising can either be associated with PET reconstruction or be used as a post-reconstruction tool. SubtlePET™ (Subtle Medical, Stanford, US, provided by Incepto, France) is a post-reconstruction PET denoising software that has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and validated by the European Commission for [18F]FDG PET [22]. The algorithm is based on deep convolutional neural networks (DCNN), the most common DL architecture [23, 24]. SubtlePET™ uses multi-slice 2.5D encoder-decoder U-Net DCNN. It takes the pixel’s neighborhood into account to reduce noise and increase image quality. Using a residual learning approach that is optimized for quantitative (L1 norm) and structural similarity (SSIM), it has learned to separate and suppress noise components while preserving non-noise components.

Recently, SubtlePET™ processed [18F]FDG PET images obtained with 33% less injected activity gave similar visual and quantitative performances to native PET in analog PET/CT without time-of-flight (TOF) [25]. Promising results were also reported while reducing reconstructed PET acquisition time by 75% using analog and digital PET/CT (with or without TOF) in a smaller study population with a substantially higher original time-activity PET product [26]. Our group demonstrated the stability of most [18F]FDG PET radiomics features while applying this software without study count reduction [27].

In this prospective study, we aimed to evaluate the feasibility of halving PET acquisition time in a routine clinical setting by using SubtlePET™ while preserving visual and semi-quantitative PET performances in digital TOF PET/CT.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

One hundred ninety-five adult patients referred to our comprehensive cancer center for initial or follow-up [18F]FDG PET/CT from end-January to end-February 2021 were prospectively included in this study. The only exclusion criterion was a specific acquisition protocol involving a longer acquisition time per bed position on the head and neck or liver areas.

This non-interventional clinical study was approved by the local institutional review board from the François Baclesse Comprehensive Cancer Center and was registered with the French Health Data Hub under reference N° F20210720123322 on 20 January 2021. All patients provided informed consent to the use of their data.

Imaging protocol and processing

All exams were performed in accordance with the EANM imaging guidelines [28] on a digital SiPM PET/CT (VEREOS, Philips Healthcare). After a 6-h fasting period, patients were injected with 3 MBq/kg [18F]FDG intravenously.

Before each PET scan, a low-dose non-contrast-enhanced CT scan was acquired for attenuation correction and as an anatomical reference. CT scan parameters were 100–140 kV, with variable mAs according to a dose right index of 14 and an iterative reconstruction Idose of 4:64 × 0.625-mm slice collimation, the pitch of 0.83, rotation time 0.5 s, 3D modulation, matrix 512 × 512 and voxel size 0.97 × 0.97 × 3 mm3.

PET acquisition, 1 h post-injection, was recorded in list-mode. Its field comprised at least the skull base to the upper thigh and was extended to total body acquisition if needed. Two PET reconstructions were performed: one for routine clinical purposes using the full acquisition time of 90 s per bed position (“PET90”), and a second one using 45 s per bed position for the purpose of this study (“PET45”). For both reconstructions, we used 3D ordered subset expectation maximization (3D-OSEM) with Point Spread Function (PSF), 4 iterations with 4 subsets (4i4s), a 2 × 2 × 2 mm3 voxel size, and 288 × 288 matrix size. Scatter, attenuation, and random corrections were computed.

PET45 images were processed by SubtlePET™ and are referred to hereafter as “PET45AI.” A fully automatic workflow allowed image transfer as well as denoising. A common and affordable NVIDIA 1080 GPU processor was used for SubtlePET™.

Image analysis

Visual analysis

Original blinded PET90 and PET45AI were reviewed side-by-side by five experienced nuclear medicine physicians on a Syngo.via viewing server (version VB 30A, Siemens Healthcare). Each reader interpreted a unique part of the study population (all images per patient) and did not review PET/CT scans they had previously seen in clinical practice.

Readers attributed a global, whole-image quality (IQ) score to each PET series: 1 = poor; 2 = moderate; 3 = good. It was based on global and hepatic image noise and on normal tissue contrast.

All lesions with increased [18F]FDG uptake were notified on each PET series. For each lesion, the readers specified the preferred PET series for detection (related to the contrast-to-background ratio), the supposed nature, i.e. malignant (primary tumor, local recurrence, (nodal) metastasis), benign or indeterminate, and its location.

Additionally, to evaluate the incremental value of AI-based denoising, PET45 was compared to PET90 and PET45AI in 146 patients (due to missing data).

Semi-quantitative analysis

Lesions were independently and semi-automatically segmented on each PET series, using the 50% 3D-isocontour of the maximal pixel value.

In each lesion volume-of-interest (VOI), the following standardized uptake values based on lean body mass (SUL) were measured: SULmax and SULpeak. LBM was estimated using the Janma formula [29].

The metabolic volume (MV) of the lesion and, when feasible, its short and long axes on the associated CT were calculated.

In addition, the reference liver SULmean with its standard deviation (SD) were collected in a 3 cm-diameter VOI in the right liver lobe, identical for each PET series.

Both standard and EARL1 (European Association of Nuclear Medicine Research Ltd) SUL were analyzed. EARL1 SUL was obtained numerically by Gaussian post-filtering within Syngo.via (EQ.PET filter [30]), with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 7.2 mm for all PET series. Our center is EARL accredited, and we use EARL1 SUL in routine practice for quantification, as it is transposable to different PET cameras and reconstructions [31].

Lesion-to-liver ratios (LLR) were calculated as SUL/SULmean liver and the coefficient of variation in the liver (CVliv) as SD/ SULmean.

Statistical analysis

Shapiro–Wilk testing found all quantitative variables (except for denoising processing time and SUL differences) to be non-normally distributed, further expressed by the median and interquartile range (IQR).

IQ scores between two PET series were compared by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with continuity correction for paired data. Concordance rates of lesion detection between PET90 and PET45AI and between PET90 and PET45 were compared by the chi-squared test. Differences in continuous quantitative variables (semi-quantitative PET measures) between two PET series were statistically analyzed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired data.

Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) between semi-quantitative measures in PET90 and PET 45AI were also calculated, considering 0.5–0.75 as moderate, 0.75–0.9 as good, and > 0.9 as excellent reliability [32]. Absolute differences in SUL between PET series were calculated as SULPET45AI − SULPET90 and relative differences or delta ∆ as (SULPET45(AI) − SULPET90) / SULPET90, and likewise for MV.

Bland Altman plots were used to display absolute SUL differences between PET90 and PET45AI, with Limits of Agreement (LOA) computed as the mean difference ± 1.96 × SD. A logistic uni- and multivariable regression analysis was carried out to look for predictive factors of a decrease of over 10% in SULmax in PET45AI vs PET90.

This decrease threshold of 10% was set by the required accuracy of SUL calibration within 10% for VEREOS PET, according to the AAPM report 126 [33]. Bonferroni correction for statistical significance level was used in univariable logistic regression analysis. Elsewhere, P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted with R version 4.0.2.

Results

Patient population and image processing

The main characteristics of the 195 patients included in this study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| N = 195 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median; IQR1 | 66; 59–74 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 122 (63) |

| Female | 73 (37) |

| Weight (kg), median; IQR | 72; 61–84 |

| BMI 2 (kg/m2) | 26; 23–30 |

| Glycaemia (g/l) | 1.05; 0.95–1.20 |

| Scan delay (min) 3 | 57; 55–59 |

| Study indication (n (%) of patients) | |

| Malignancy | 147 (75) |

| Baseline staging | 39 (20) |

| Therapeutic evaluation | 65 (33) |

| Recurrence detection/staging | 43 (22) |

| Characterization (benign vs malignant) | 41 (21) |

| Miscellaneous | 7 (4) |

| Primary lesion (origin) | |

| Lung | 70 (36) |

| Breast | 68 (35) |

| Gynecological (except breast) | 17 (9) |

| Colorectal | 6 (3) |

| Lymphoma | 6 (3) |

| Unknown primary | 6 (3) |

| Sarcoma | 5 (3) |

| Other 4 | 23 (12) |

1 IQR, interquartile range between first and third quartile (Q1 and Q3); 2 BMI, body mass index; 3 2 patients had a delay < 55 or > 65 min pi.(53 and 70 min); 4 Other primaries: prostate (4), melanoma (3), head-and-neck (3), esophagus and stomach (3), bladder (3), testicle (1), pancreas (1), anus (1), myeloma (1), mesothelioma (1), skin squamous cell carcinoma (1), Merkel cell carcinoma (1). 12 patients had more than one primary; 7 patients had no primary (sum > 195)

All two-fold count reduced PET series (PET45) were successfully treated by the denoising software with a mean processing time of 90 s (min–max; 45–122 s).

Image analysis

Visual analysis: comparison between PET90 and PET45AI

IQ scores were similar between original PET90 and PET45AI (P = 0.80), good (score 3) in 92% (n = 180 vs 179) and moderate (score 2) in 8% (n = 15 vs n = 16) of exams.

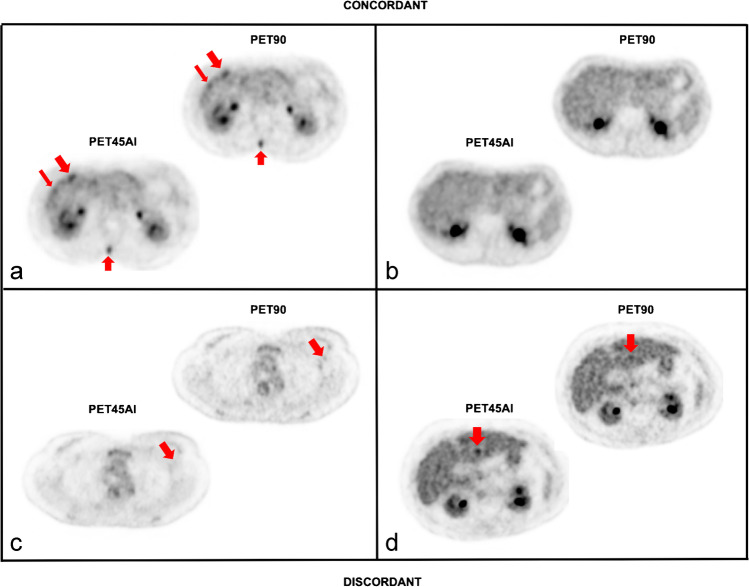

Concerning lesion detection, 33 out of 195 patients presented a normal and concordant examination on both PET series. In the remaining 162 patients, a total of 856 lesions were detected.

Of these, 836 lesions were visualized in both original PET90 and denoised PET45AI, resulting in a lesion concordance rate of 97.7%. Seven out of 856 (0.8%) small and low-uptake lesions were detected exclusively on PET90 in 6 patients (Table 2). Thirteen foci (1.5%) were detected only on PET45AI in 10 patients, mostly corresponding to indeterminate liver lesions. An illustration is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Description of discordant lesions between PET90 and PET45AI

| Patient | Lesion | Malignancy | Location | Nature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original PET90 only | 1 | 1 | lymphoma | retroperitoneal lymph node | malignant |

| 2 | 2 | breast | lung | malignant (metastasis) | |

| 3 | 3 | ovarium | peritoneum | malignant (metastasis) | |

| 4 | peritoneum | malignant (metastasis) | |||

| 4 | 5 | breast | bone | malignant (metastasis) | |

| 5 | 6 | breast | axillary lymph node | indeterminate | |

| 6 | 7 | lung | small intestine | indeterminate | |

| PET45AI only | 7 | 8 | mesothelioma | liver | indeterminate |

| 9 | liver | indeterminate | |||

| 8 | 10 | hypopharynx | liver | indeterminate | |

| 9 | 11 | lung | liver | indeterminate | |

| 12 | liver | indeterminate | |||

| 10 | 13 | breast | liver | indeterminate | |

| 11 | 14 | multiple myeloma | liver | indeterminate | |

| 12 | 15 | breast | liver | indeterminate | |

| 13 | 16 | lung | liver | indeterminate | |

| 14 | 17 | breast | liver | indeterminate | |

| 15 | 18 | breast | spleen | indeterminate | |

| 16 | 19 | colon | bone | benign | |

| 20 | bone | indeterminate |

Fig. 1.

Two concordant and two discordant PET images between PET90 and PET45AI In a several hepatic (oblique red arrows) and a spinal bone metastasis (vertical upward red arrows) in a female patient with breast cancer were detected on both original PET90 and denoised PET45AI. In b a concordantly negative PET. In c a low-uptake, sub-centimetric left axillary lymph node (oblique red arrows) in a patient referred for left breast cancer staging, classified indeterminate and exclusively detected on original PET90. In d an indeterminate liver focus exclusively annotated on PET45AI (vertical downward red arrows) in a male patient scanned for advanced lung cancer staging

There was no per-lesion preferred PET series for detection in 86% of lesions. On the other hand, original PET90 was preferred for 12% and PET45AI for 2%.

Semi-quantitative analysis: PET90 and PET45AI measures

Statistical comparison of standard values

Lesion SULmax, SULpeak, LLR, and CVliv were significantly lower in denoised PET45AI than in original PET90 (P < 0.0001) (Table 3). In contrast, lesion MV and liver SULmean were higher in PET45AI than in PET90 (P < 0.0001). Lesion SUL, MV, LLR, and liver SULmean showed a good-to-excellent correlation between both PET series (≥ 0.873 up to 0.998).

Table 3.

Standard semi-quantitative measures in original PET90 and denoised PET45AI

| PET90 | PET45AI | ICC [95%CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion | SULmax (g/ml) | 4.45 [3.08–7.53] | 3.99 [2.68–6.94] | 0.99 [0.98–0.99] |

| SULpeak (g/ml) | 2.72 [1.87–4.77] | 2.63 [1.79–4.65] | 1.00 [0.99–1.00] | |

| MV (ml) | 1.22 [0.61–2.90] | 1.45 [0.80–3.30] | 0.97 [0.97–0.98] | |

| Liver | SULmean (g/ml) | 1.66 [1.52–1.84] | 1.77 [1.60–1.96] | 0.87 [0.84–0.90] |

| CV (%) | 12.83 [11.71–14.49] | 10.96 [9.55–12.41] | 0.58 [0.48–0.66] | |

| Lesion/liver | LLRmax | 2.68 [1.81–4.58] | 2.32 [1.51–4.04] | 0.97 [0.97–0.98] |

| LLRpeak | 1.67 [1.12–2.86] | 1.51 [1.01–2.69] | 0.99 [0.99–0.99] |

All values are expressed as median [interquartile range]. ICC, intraclass correlation coefficients between PET90 and PET45AI measures; MV, metabolic volume; CV, coefficient of variation; LLR, lesion-to-liver ratio

Statistical comparison of EARL1values

Lesion EARL1 SULpeak was not significantly different between both PET series (P = 0.09). Otherwise, the comparison of EARL1 SUL and derived measures between PET90 and PET45AI was similar to the comparison of standard measures.

Absolute and relative differences

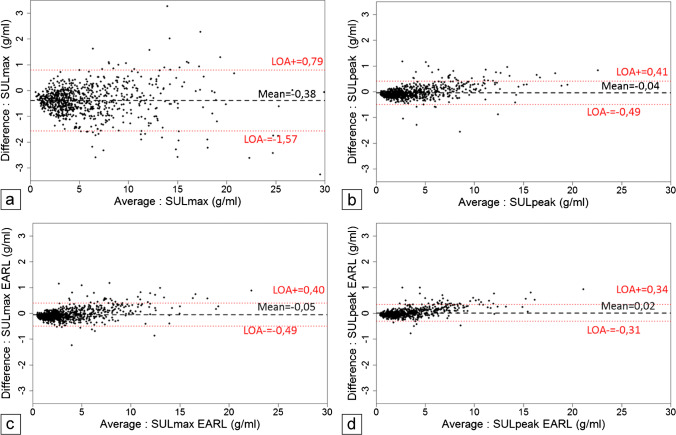

Bland Altman (Fig. 2) plots show the absolute difference between both PET series in SULmax and SULpeak (both standard and EARL1 measures) for each lesion. The highest mean absolute difference reached − 0.38 g/mL [95% CI − 0.43, − 0.34] for standard SULmax in PET45AI vs original PET90. The other average absolute differences were close to 0.

Fig. 2.

Bland Altman plots for standard SULmax (a) and SULpeak (b) and respective EARL1 SULmax (c) and SULpeak (d): Y-axis shows the absolute differences between PET45AI and PET90 SUL measures versus their means on X-axis. A dashed black line corresponds to the mean and dotted red lines to the upper and lower limits of agreement (LOA). Most lesions had SUL below 5 g/ml

The mean ± SD relative differences in PET45AI compared to PET90 reached − 9.48 ± 11.50% for standard SULmax, − 3.41 ± 7.17% for standard SULpeak, − 3.74 ± 7.34% for EARL1 SULmax, and − 1.37 ± 5.71% for EARL1 SULpeak of lesions. For liver SULmean, the mean relative difference was + 5.64 ± 4.75% and 5.88 ± 3.93% for standard and EARL1 measures, respectively.

Explanatory factors analysis of differences between PET90 and PET45AI

In visual lesion detection

Table 4 shows lesion characteristics (size and uptake) according to their detectability. Most discordant and preferred lesions had a low-to-moderate uptake and size.

Table 4.

Lesion features according to their detectability in original PET90 and denoised PET45AI

| Size on CT (mm) | MV (ml) 1 | SULmax (g/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute detection | Long axis | Short axis | ||

| Concordant | 16 [10–24] | 10 [7–16] | 1.3 [0.6–3.2] | 4.4 [3.1–7.5] (2) |

| Discordant PET90 only | 5 [5–6] | 4 [3–6] | 0.8 [0.6–1.2] | 2.1 [1.5–2.6] |

| Discordant PET45AI only | NA3 | NA | 1.2 [0.6–2.9] | 3.0 [2.5–3.3] |

| Preferred serie for detection | ||||

| No | 17 [11–25] | 11 [7–17] | 1.5 [0.8–3.8] | 4.6 [3.1–7.7] (2) |

| PET90 | 9 [7–12] | 7 [5–9] | 1.1 [0.7–1.8] | 2.7 [2.0–3.6] (2) |

| PET45AI | 8 [5–22] | 6 [4–16] | 1.5 [0.9–2.7] | 2.2 [1.6–2.8] (2) |

All measures are displayed as median [interquartile range]; 1 MV, metabolic volume. Note that metabolic volumes of small lesions and with low contrast-to-background ratios are less accurate. 2 of original PET90; 3 NA, not assessable (no measurable CT lesion)

In lesion SULmax

Multivariable logistic regression analysis indicated two independent predictors of a SULmax decrease of over 10% in PET45AI compared to PET90, namely SULmax in PET45AI (P < 0.0001) and CT long axis (P = 0.01) (Table 5). Supplementary Fig. 3 shows that the smaller the lesion size on CT and the lower the SULmax, the greater the probability of a negative SULmax bias over 10%.

Table 5.

Uni-and multivariable logistic regression analysis for predicting a negative ΔSULmax above 10% in PET45AI compared to PET90

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | P | OR | P | |

| Age | 0.99 [0.82–1.21] | 0.98 | 1.04 [0.81–1.34] | 0.77 |

| Female sex | 1.87 [1.26–2.78] | 0.002* | 1.11 [0.65–1.87] | 0.71 |

| BMI | 1.20 [0.99–1.44] | 0.05 | 1.02 [0.78–1.32] | 0.91 |

| Glycaemia | 1.18 [0.97–1.43] | 0.10 | 1.17 [0.89–1.54] | 0.25 |

| SULmax(1) | 0.18 [0.13–0.25] | < 0.0001* | 0.22 [0.14–0.33] | < 0.0001* |

| CT long axis | 0.20 [0.14–0.29] | < 0.0001* | 0.49 [0.28–0.84] | 0.01* |

| MV (1) | 0.06 [0.03–0.13] | < 0.0001* | 0.28 [0.07–1.11] | 0.07 |

| CVliv(1) | 0.98 [0.81–1.18] | 0.81 | 1.35 [0.87–2.09] | 0.18 |

| CVliv_Ratio | 0.96 [0.82–1.14] | 0.67 | 0.79 [0.56–1.11] | 0.17 |

* statistically significant. 1 of PET45AI. OR, odds ratio; BMI, body mass index; MV, metabolic volume; CVliv, coefficient of variation in the liver. CVliv_Ratio = CVliv (PET45AI) / CVliv (PET90). PET45AI SULmax values were used to build a predictive model focusing on the end result, namely denoised and not original PET. However, we obtained the same results with original PET90 SULmax. A negative ΔSULmax above 10% concerned 383 lesions (46%). Few lesions showed an increase above 10% in SULmax (n = 9; 1.0%) on PET45AI vs PET90, not further analyzed

Evaluation of PET45

Visual analysis

PET90, PET45, and PET 45AI were compared in 146 patients. Two cases are illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4.

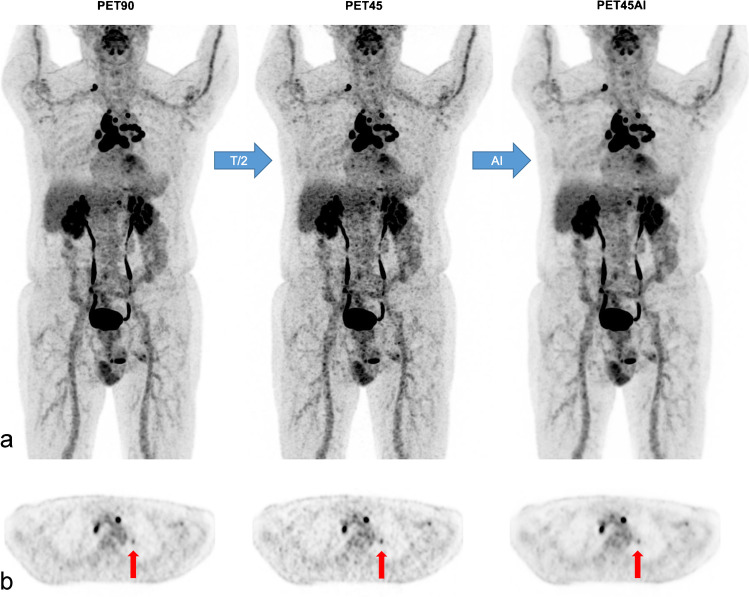

Fig. 3.

Concordant lesions A 77-year-old man (78 kg; BMI 24 kg/m2) with multifocal lymphadenopathy of unknown origin. MIP views (a) and axial PET slices (b) of [18F]FDG PET90, PET45, and PET45AI. Detection of small left suprahilar lymphadenopathy in all PET series (vertical arrows in b) with respective standard SULmax of 1.8 (PET90), 2.3 (PET45), and 1.7 g/ml (PET45AI). Nonetheless, PET45 images are noisier than PET90 or PET45AI images, particularly in the liver

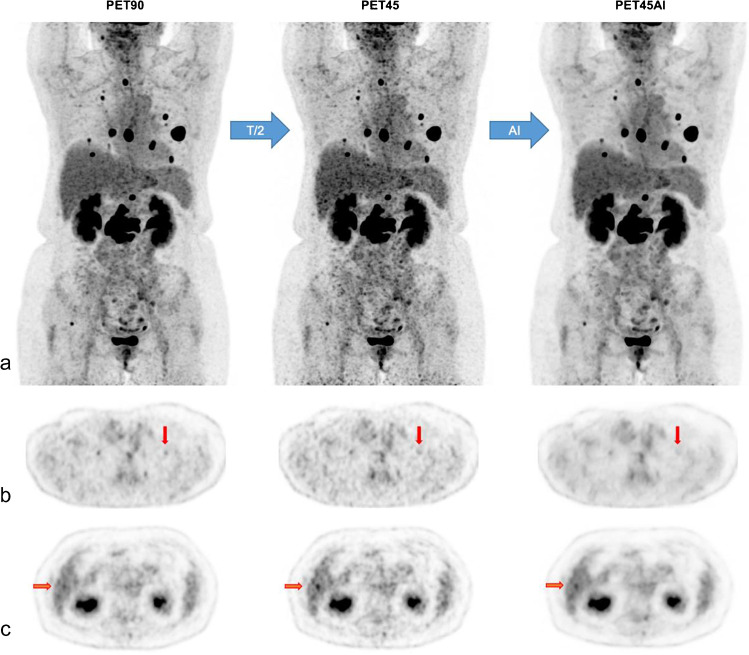

Fig. 4.

Discordant lesions A 59-year-old women (66 kg; BMI 23 kg/m2) with a history of breast cancer showing multiple lung and bone metastases. MIP views (a) and axial PET slices (b and c) of [18F]FDG PET90, PET45, and PET45AI. Vertical red arrows in (b) demonstrate one lung metastasis in the upper lobe of the left lung only detected in PET90, measuring 2 × 3 mm on CT with standard SULmax of 1.1 g/ml in PET90. In c a false positive hepatic focus in PET45 (horizontal red arrows)

IQ scores were lower in PET45 (median: 2) than in both PET90 and PET45AI (median: 3), P < 0.0001. Poor IQ scores (= 1) were exclusively found in PET45 scans (n = 12; 8%). IQ was scored moderate (= 2) in 99 (68%) PET45 examinations vs in 13 (9%) PET90 and 16 (11%) PET 45AI, the remainder being considered of good image quality.

In this subgroup of patients, the lesion detection concordance rate between PET90 and PET45 was 88.7% (582/656), while that between PET90 and PET45AI was 97.4% (589/605), P < 0.0001. The number of false-positive foci was higher in PET45 (n = 61; 9.3%) than in PET45AI (n = 10; 1.7%), P < 0.0001. Furthermore, 13 (2.0%) false-negative lesions were present in PET45 and 6 (1.0%) in PET45AI, P = 0.15.

Semi-quantitative analysis

Lesion standard SULmax was significantly higher in PET45 than in PET90 (P ≤ 0.0001, with an average ± SD relative bias of + 3.30 ± 10.34%). Lesion standard SULpeak, EARL1 SULpeak and EARL1 SULmax were similar in PET90 and PET45.

CVliv was significantly higher in PET45 (median 18.00; IQR 15.98–21.16%) than in PET90 (12.84; 11.88–14.27%) and than in PET45AI (10.80; 9.68–12.21%), P < 0.0001.

Discussion

This prospective study shows good visual and semi-quantitative performances of AI-denoised half-count PET compared to original PET in a digital PET/CT. We simulated a two-fold reduction in the PET acquisition time and then applied a commercially available PET denoising software based on U-net DCNN. All PET series were successfully denoised within 2 min in an automatic workflow using a common GPU card. This makes it compatible with routine clinical use. Visually, global image quality scores were similar between PET90 and PET45AI but lower and clinically insufficient in half-count PET45 due to high noise. We obtained few discordances (2.3%) between original PET90 and denoised PET45AI in the absolute detection of 856 lesions.

A total of 0.8% of lesions were detected only on PET90 in 3% of patients. This concerned sub-centimetric or small lesions with a maximum SULmax of 3.1 g/ml. Most of these “original PET90-only or false-negative lesions in PET45AI” were classified as authentically malignant (71%) or indeterminate (29%). Many other concordant malignant lesions were detected in all but one of these patients.

A total of 1.5% of lesions were exclusively visualized on denoised PET45AI in 5% of patients. These “false positives” were predominantly located in the liver and interpreted as indeterminate or benign foci. For most lesions, there was no per-lesion preferred PET series for detection. However, in a minority of lesions (12%), original PET was preferred and less frequently (in 2%) denoised PET. Whether on original or on denoised PET, preferred lesions showed a variable uptake and size, mostly low-to-moderate. More expertise in the reading of these new denoised PET images could further improve the accuracy and comfort of readers.

A higher lesion detection discordance rate (> 10%) was found between PET90 and half-duration PET45 than between PET90 and PET45AI, with particularly additional false positives in PET45. This further renders half-count PET not compatible with routine clinical use. Similar results were observed in [21], with also a decrease in diagnostic confidence when dividing acquisition time by two.

Comparing semi-quantitative SUL measures in lesions between PET90 and PET45AI, only harmonized EARL1 SULpeak was not significantly different when using the same Gaussian post-filter for both PET series. Standard SULpeak and standard and EARL1 SULmax were lower in denoised PET45AI than in original PET90. The average relative difference remained below 10% for all lesion SUL. Greater SUL biases occurred especially in lesions with a moderate size and uptake and mostly “non-target and non-evaluable lesions” according to PERCIST criteria [34, 35]. In our quantitative study, all lesions were taken into account. The overrepresentation of small, low-uptake lesions negatively affected quantitative differences between both PET series.

On the other hand, SULmean in the reference liver was slightly higher (on average + 6%) in PET45AI than in the original PET90. Its standard deviation and thus its noise levels were lower (on average − 12% for standard CVliv). The decrease in CVliv highlights the denoising efficacy even when dividing study counts by two.

Some other research groups have found even lower SUV biases, despite a higher study count reduction, especially while using CycleGANs as DL architecture [16, 17] or Subtle PET™ (U-net) [26]. However, their studies were performed on different and/or smaller cohorts.

A pilot study of 10 small lung nodules suggested that a fully 3D U-net compared to a 2.5D U- net, as used in our study, may offer better lesion quantitative performance, even though visual image quality was similar [19]. However, 2.5D U-net is useful for routine clinical practice owing to its shorter computational time and lower processing capacity requirement.

Nevertheless, probably more important than these differences in semi-quantitative measures was their correlation between original PET90 and PET45AI, in particular for lesion SUL.

This inter-PET correlation was very high for lesion SUL and MV (with ICCs of at least 0.97) and high for liver SULmean (with ICCs of at least 0.87), testifying to the stability and reliability of these measures obtained after PET count reduction and denoising.

A strength of our study is a large number of lesions of very different sizes, uptake, nature, and location.

Study limitations are the side-by-side reading methodology which could have enhanced the detection accuracy in PET45(AI). Second, the clinical impact of denoised PET has not been properly established. Third, the unlimited lesion number per patient led to a potential statistical bias due to the over-representation of dependent lesions in the same patients. Fourth, the effect of AI-denoising on image artifacts was not studied. A final small drawback is a use of harmonized EARL1 SUL measures, which are still widely used, and not more recent EARL2 values [36].

Our study thus supports the routine use of Subtle PET™ combined with a two-fold faster PET acquisition.

The benefit of decreasing PET duration, thus reducing waiting time for appointments and helping patients who experience discomfort, outweighs the minor decrease in performance.

Although not properly studied, our findings could also lead to a reduction in injected activity or a combination of both (activity and time). Initially, an Italian group reported a similar performance of Subtle PET™ treated PET with 33% less injected [18F]FDG activity compared to native PET in non-TOF analog PET/CTs [25].

Further research should be carried out on ways to increase performances, e.g. by optimizing the DL-model and/or adapting acquisition time in liver and regions of interest. Furthermore, large multicentric studies with different PET cameras, reconstruction parameters, and various reductions in [18F]FDG PET acquisition time-activity product are necessary. Striking the optimal balance between performance and time savings is essential. Moreover, research with other PET radiopharmaceuticals is warranted.

Conclusion

This prospective study demonstrates the satisfactory preservation of [18F]FDG PET image quality and quantification when applying AI-based denoising on half-duration PET compared to original full-duration PET. AI restored degraded and clinically insufficient image quality of half-duration PET. It paves the way for a significant reduction in acquisition time and the optimization of PET imaging equipment in routine clinical practice.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ray Cooke for language editing.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Kathleen Weyts (material preparation, image reading, and data analysis), Charline Lasnon, Renaud Ciappuccini, Elske Quak, Stéphane Bardet (image reading), Justine Lequesne (material preparation and statistical analysis), Cyril Jaudet, and Aurélien Corroyer-Dulmont (material preparation and data analysis). The first draft of the manuscript was written by Kathleen Weyts, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

We benefitted from a 1-month free trial period of SubtlePET™.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and compliance with the French Research Standard MR-004. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Centre François Baclesse and registered (20/1/2021/ N° F20210720123322 on the French Health Data Hub).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for the publication of the images in Figs. 1, 3, and 4.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Advanced Image Analyses (Radiomics and Artificial Intelligence)

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Conti M, Bendriem B. The new opportunities for high time resolution clinical TOF PET. Clinical and Translational Imaging Springer. 2019;7:139–147. doi: 10.1007/s40336-019-00316-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rausch I, Ruiz A, Valverde-Pascual I, Cal-González J, Beyer T, Carrio I. Performance evaluation of the Vereos PET/CT system according to the NEMA NU2–2012 standard. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. Soc Nuclear Med; 2019;60:561–7. 10.2967/jnumed.118.215541 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Zhang J, Maniawski P, Knopp MV. Performance evaluation of the next generation solid-state digital photon counting PET/CT system. EJNMMI Res. 2018;8:97. doi: 10.1186/s13550-018-0448-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salvadori J, Odille F, Verger A, Olivier P, Karcher G, Marie P-Y, et al. Head-to-head comparison between digital and analog PET of human and phantom images when optimized for maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio from small lesions. EJNMMI Phys. 2020;7:11. doi: 10.1186/s40658-020-0281-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.López-Mora DA, Carrió I, Flotats A. Digital PET vs analog PET: clinical implications? Seminars in Nuclear Medicine. Elsevier. 2021 doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nensa F, Demircioglu A, Rischpler C. Artificial intelligence in nuclear medicine. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:29S–37S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.220590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seifert R, Weber M, Kocakavuk E, Rischpler C, Kersting D. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in nuclear medicine: future perspectives. Semin Nucl Med. 2021;51:170–177. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong X, Zan Y, Weng F, Tao W, Peng Q, Huang Q. Enhancing the image quality via transferred deep residual learning of coarse PET sinograms. IEEE transactions on medical imaging IEEE. 2018;37:2322–2332. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2830381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim K, Wu D, Gong K, Dutta J, Kim JH, Son YD, et al. Penalized PET reconstruction using deep learning prior and local linear fitting. IEEE transactions on medical imaging IEEE. 2018;37:1478–1487. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2832613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui J, Gong K, Guo N, Wu C, Meng X, Kim K, et al. PET image denoising using unsupervised deep learning. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. Springer; 2019;46:2780–. 10.1007/s00259-019-04468-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Berg E, Cherry SR. Using convolutional neural networks to estimate time-of-flight from PET detector waveforms. Physics in Medicine & Biology. IOP Publishing; 2018;63:02LT01. 10.1088/1361-6560/aa9dc5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Liu J, Malekzadeh M, Mirian N, Song T-A, Liu C, Dutta J. Artificial intelligence-based image enhancement in PET imaging: noise reduction and resolution enhancement. PET clinics Elsevier. 2021;16:553–576. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet2021.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan S, Zhu Y-M. Full-dose PET image estimation from low-dose PET image using deep learning: a pilot study. Journal of digital imaging Springer. 2019;32:773–778. doi: 10.1007/s10278-018-0150-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiang L, Qiao Y, Nie D, An L, Lin W, Wang Q, et al. Deep auto-context convolutional neural networks for standard-dose PET image estimation from low-dose PET/MRI. Neurocomputing Elsevier. 2017;267:406–416. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2017.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaefferkoetter J, Yan J, Ortega C, Sertic A, Lechtman E, Eshet Y, et al. Convolutional neural networks for improving image quality with noisy PET data. EJNMMI research Springer. 2020;10:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13550-020-00695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanaat A, Shiri I, Arabi H, Mainta I, Nkoulou R, Zaidi H. Deep learning-assisted ultra-fast/low-dose whole-body PET/CT imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:2405–2415. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05167-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou L, Schaefferkoetter JD, Tham IW, Huang G, Yan J. Supervised learning with cyclegan for low-dose FDG PET image denoising. Medical Image Analysis. Elsevier; 2020;65:101770. 10.1016/j.media.2020.101770 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Liu H, Wu J, Lu W, Onofrey JA, Liu Y-H, Liu C. Noise reduction with cross-tracer and cross-protocol deep transfer learning for low-dose PET. Phys Med Biol. 2020;65:185006. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/abae08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu W, Onofrey JA, Lu Y, Shi L, Ma T, Liu Y, et al. An investigation of quantitative accuracy for deep learning based denoising in oncological PET. Physics in Medicine & Biology. IOP Publishing; 2019;64:165019. 10.1088/1361-6560/ab3242 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Wang Y-RJ, Baratto L, Hawk KE, Theruvath AJ, Pribnow A, Thakor AS, et al. Artificial intelligence enables whole-body positron emission tomography scans with minimal radiation exposure. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021. 10.1007/s00259-021-05197-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Mehranian A, Wollenweber SD, Walker MD, Bradley KM, Fielding PA, Su K-H, et al. Image enhancement of whole-body oncology [18F]-FDG PET scans using deep neural networks to reduce noise. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. Springer; 2021;1–11. 10.1007/s00259-021-05478-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.SubtlePET | Subtle Medical [Internet]. accessed on Nov 17 2021. Available from: https://subtlemedical.com/subtlepet/

- 23.Sahiner B, Pezeshk A, Hadjiiski LM, Wang X, Drukker K, Cha KH, et al. Deep learning in medical imaging and radiation therapy. Med Phys. 2019;46:e1–36. doi: 10.1002/mp.13264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeCun Y, Kavukcuoglu K, Farabet C. Convolutional networks and applications in vision. Proceedings of 2010 IEEE international symposium on circuits and systems. IEEE. 2010; 10.1109/ISCAS.2010.5537907

- 25.Katsari K, Penna D, Arena V, Polverari G, Ianniello A, Italiano D, et al. Artificial intelligence for reduced dose 18F-FDG PET examinations: a real-world deployment through a standardized framework and business case assessment. EJNMMI Phys. 2021;8:25. doi: 10.1186/s40658-021-00374-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaudhari AS, Mittra E, Davidzon GA, Gulaka P, Gandhi H, Brown A, et al. Low-count whole-body PET with deep learning in a multicenter and externally validated study. NPJ digital medicine Nature Publishing Group. 2021;4:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00497-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaudet C, Weyts K, Lechervy A, Batalla A, Bardet S, Corroyer-Dulmont A. The impact of artificial intelligence CNN based denoising on FDG PET radiomics. Frontiers in oncology. Frontiers; 2021;3136. 10.3389/fonc.2021.692973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Boellaard R, Delgado-Bolton R, Oyen WJG, Giammarile F, Tatsch K, Eschner W, et al. FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging: version 2.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:328–54. 10.1007/s00259-014-2961-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Janmahasatian S, Duffull SB, Ash S, Ward LC, Byrne NM, Green B. Quantification of lean bodyweight. Clinical pharmacokinetics Springer. 2005;44:1051–1065. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544100-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quak E, Le Roux P-Y, Hofman MS, Robin P, Bourhis D, Callahan J, et al. Harmonizing FDG PET quantification while maintaining optimal lesion detection: prospective multicentre validation in 517 oncology patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:2072–2082. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3128-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aide N, Lasnon C, Veit-Haibach P, Sera T, Sattler B, Boellaard R. EANM/EARL harmonization strategies in PET quantification: from daily practice to multicentre oncological studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:17–31. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3740-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koo TK, Li MY. Cracking the code: providing insight into the fundamentals of research and evidence-based practice a guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mawlawi O, Jordan D, Halama J, Schmidtlein C, Wooten W. PET/CT acceptance testing and quality assurance [Internet]. AAPM; 2019 Oct. Available from: https://www.aapm.org/pubs/reports/detail.asp?docid=193

- 34.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge MA. From RECIST to PERCIST: evolving considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. Journal of nuclear medicine. Soc Nuclear Med; 2009;50:122S-150S. 10.2967/jnumed.108.057307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Joo Hyun O, Lodge MA, Wahl RL. Practical PERCIST: a simplified guide to PET response criteria in solid tumors 1.0. radiology. Radiological Society of North America; 2016;280:576. 10.1148/radiol.2016142043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Kaalep A, Sera T, Rijnsdorp S, Yaqub M, Talsma A, Lodge MA, et al. Feasibility of state of the art PET/CT systems performance harmonisation. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. Springer; 2018;45:1344–61. 10.1007/s00259-018-3977-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.