Abstract

Perfectionism has a strong association with eating disorders, anxiety and depression. Unguided internet cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism has demonstrated efficacy in female adolescents without elevated eating disorder symptoms. No research to date has examined unguided internet cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism for adolescents with elevated eating disorder symptoms as an indicated prevention for eating disorders and co-occurring symptoms of anxiety and depression. The protocol outlines the plan for a randomised controlled trial of a co-designed, unguided internet cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism with female adolescents with elevated symptoms of eating disorders. The intervention will be a 4-week programme compared to a waitlist control. Outcomes on eating disorder symptoms, anxiety and depression will be measured pre and post intervention and follow-up.

Trial registration

This trial was registered on 23 September 2020 with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12620000951954P).

Keywords: Internet interventions, Cognitive-behavioural therapy, Perfectionism, Eating disorders, Adolescents, Protocol

Highlights

-

•

This protocol described a planned trial of internet CBT for perfectionism in adolescents.

-

•

Female adolescents with elevated eating disorder symptoms will be included in this indicated prevention trial.

-

•

The intervention has been co-designed with adolescents to ensure relevance to young people.

-

•

Efficacy will be examined on outcomes of perfectionism, eating disorders, anxiety and depression.

1. Introduction

Perfectionism is a risk and perpetuating factor for eating disorder symptoms in adults (Fairburn et al., 2003b; Limburg et al., 2017) and adolescents (Johnston et al., 2018; Vacca et al., 2021). Cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism (CBT-P) has been demonstrated in recent meta-analyses to have medium effects on eating disorder symptoms (g = 0.61 (Galloway et al., 2022); g = 0.64 (Robinson and Wade, 2021)) and transdiagnostic impacts on anxiety (g = 0.42) and depressive (g = 0.60) symptoms (Galloway et al., 2022). Numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT-P on reducing perfectionism and psychopathology, delivered via the internet in unguided (e.g., Egan et al., 2014; Grieve et al., 2022; Shu et al., 2019; Valentine et al., 2018; Wade et al., 2019) and guided formats (Rozental et al., 2017; Shafran et al., 2017). A meta-analysis has indicated no difference between face to face and internet delivered CBT-P (Suh et al., 2019).

The majority of studies of CBT-P have been treatment studies, however some studies have examined it as a prevention to reduce the onset of psychological symptoms and disorders. It is generally acknowledged that there are three levels that prevention can be categorised into; universal prevention (population-level interventions applied regardless of risk), selective prevention (targeting a subpopulation who are identified as having increase risk factors for the disorder), and indicated (targeted) prevention (individuals who do not meet full diagnostic criteria but are exhibiting traits or symptoms of the disorder) (Gordon, 1983). However, often prevention studies are in fact risk reduction studies (Watson et al., 2016), despite this, we will be consistent with the literature and refer to the current study as a prevention trial.

Preliminary research has demonstrated face to face delivery of CBT-P as a universal prevention programme can prevent the onset of anxiety and depression in adolescents (Nehmy and Wade, 2015; Vekas and Wade, 2017). Wilksch et al. (2008) demonstrated the efficacy of face to face CBT-P as an indicated prevention for female adolescents with eating disorder symptoms. Wilksch et al. (2008) recruited 128 female adolescents (mean age = 15 years), and defined the high risk for eating disorder group as those with a mean score ≧4 on the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn and Beglin, 1994) shape and weight concern subscales. They found small to medium effect sizes for eating disorder symptoms (d = 0.31) at post treatment, and these gains were maintained at 3-month follow up (d = 0.27), with the programme showing most promise in the ‘high risk’ group. Whilst this presents promising initial results, further research is needed, particularly on scalable formats of the intervention as there has only been one trial of internet delivered CBT-P as a prevention for eating disorders in adolescents.

Shu et al. (2019) conducted a selective prevention trial which was an RCT of unguided internet delivered CBT-P (ICBT-P) with 94 female adolescents aged 14–19 years. In this study participants were excluded if they had high eating disorder scores defined as a score of ≧2 on the SCOFF (Hill et al., 2010), in order for the study to be a selective rather than indicated prevention for those with elevated eating disorder symptoms. The ICBT-P group had medium reductions compared to control in clinical perfectionism (perfectionistic concerns factor) at post-treatment (d = 0.69) which were large effects at 6-month follow-up (d = 0.84). The results demonstrated no significant difference between groups on eating disorder symptoms at post-treatment, however there appeared to be a delayed treatment effect, as at 6-month follow-up the ICBT-P group demonstrated a large reduction in eating disorder symptoms (d = 0.85) compared to control. Further, there was a transdiagnostic impact of treatment observed, where at post-treatment the ICBT-P group had medium reductions compared to control in anxiety (d = 0.79) and depression (d = 0.58), which were maintained at 6-month follow-up (anxiety d = 0.69; depression d = 0.63).

The results of Shu et al. (2019) are encouraging, however no research to date has examined whether ICBT-P has efficacy as an indicated (targeted) prevention in eating disorders which is the important next step to examine whether the intervention can prevent the onset of clinical eating disorders in adolescents starting to display symptoms.

The utility of targeting perfectionism is valuable, as a transdiagnostic process (Egan et al., 2011) which has demonstrated the ability to treat a range of symptoms of eating disorders, anxiety and depression (Galloway et al., 2022; Robinson and Wade, 2021). Consequently, CBT-P holds promise as an intervention to prevent eating disorders and associated anxiety and depression in young people. Indeed, previous studies of CBT-P delivered in a book format have demonstrated the treatment was equally effective in reducing eating disorder symptoms to standard CBT for eating disorders in a clinical eating disorder sample, but not surprisingly as CBT-P is a transdiagnostic treatment, resulted in larger effect size reductions in anxiety and depression than CBT for eating disorders (Steele and Wade, 2008).

The rationale for internet-delivered indicated prevention is clear in order to increase access to the intervention compared to traditional face to face prevention programmes which have been well researched in eating disorders (Watson et al., 2016). Internet delivered interventions have been extensively demonstrated to be efficacious for a range of psychological disorders (see Andersson (2016) for a review). Internet interventions have many benefits including reducing inequality in access, cost-effectiveness, and scalability (Andersson, 2016).

The aim of the proposed trial is to examine the efficacy of co-designed ICBT-P for adolescents with elevated symptoms of eating disorders. The two novel aspects of the proposed research are: (i) to conduct the first indicated (targeted) prevention trial of ICBP-P for eating disorders and associated anxiety and depression in adolescents and (ii) to conduct the first co-designed ICBT-P intervention. An important new contribution to the literature of the proposed trial is that the intervention will be co-designed by adolescents with lived experience of perfectionism. Given the critical importance highlighted in recent research of including young people as co-creators of interventions (Sebastian et al., 2021), including perfectionism, there are no studies to date which have included young people in the development of interventions for perfectionism (Egan et al., 2022). In a review of studies of perfectionism in young people, Egan et al. (2022) concluded that it is imperative for future research to include young people with lived experience in co-designing CBT-P, as CBT-P to date has not been co-designed with youth. Engaging in co-designed interventions with adolescents with lived experience of perfectionism may help to improve the interventions and relevance to young people (Egan et al., 2022).

2. Method

2.1. Aims and hypothesis

The aim of the proposed randomised controlled trial (RCT) is to examine the efficacy of co-designed ICBT-P as an indicated prevention programme to target symptoms of eating disorders and associated anxiety and depression in female adolescents. This trial will examine the efficacy of unguided ICBT-P which has been refined from the website evaluated in Shu et al. (2019) in a sample of Australian female adolescents displaying elevated eating disorder symptoms. The determination to limit the current trial to female adolescents was due to issues historically found in attempting to recruit sufficient sample sizes of male participants with eating disorder symptomology. It is hypothesised that after completion of unguided ICBT-P compared to a control group participants will report significantly lower perfectionism and symptoms of eating disorders, anxiety and depression which will be maintained at 6-month follow-up. A prevention impact will be demonstrated by a clinically significant reduction in symptoms of disordered eating that fall outside of clinical norms, where scores on the EDE-Q of 3.26 or above are used as a proxy indicative of an eating disorder (see discussion below of O'Brien et al. (2016) EDE-Q norms in adolescent clinical populations). A similar procedure to indicate prevention effects was used in Nehmy and Wade et al. (2015) where a cut-off score on the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) was used as an indicator of clinical levels of negative affect, and in Wade et al. (2015) and Wilksch et al. (2008) where a mean score on the EDE-Q was used to categorise eating disorder prevention.

2.2. Design

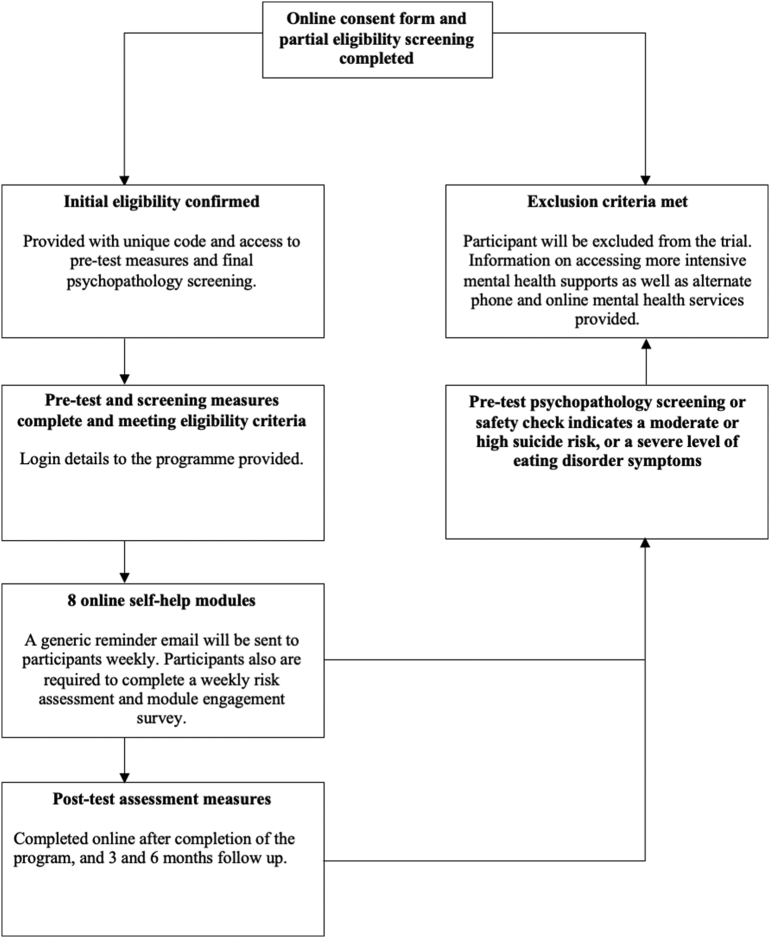

This study is an RCT which will include a minimum sample of 196 female adolescents aged 13–18 years. Following screening, eligible participants will complete outcome measures at pre-intervention and post-intervention, as well as at one, three, and six-month follow-up (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of participants through study.

2.3. Intervention development

The ICBT-P programme is based on ‘Overcoming Perfectionism’ (Shafran et al., 2018), and the intervention was developed by adapting and refining the website evaluated in Shu et al. (2019). Despite the efficacy of the website evaluated in Shu et al. (2019), it has been increasingly recognized as important to ensure that interventions are jointly designed, and that young people co-create interventions and their input is included to all stages of research (Hetrick et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2015; Shaw et al., 2016). In order to ensure that our intervention was not merely designed for youths by researchers, we consulted with young people to co-create a new website based on the one created by Shu et al. (2019), through a Youth Advisory Group (YAG).

Members of the YAG (N = 5, 100 % female, age range 16 to 17 years, mean age = 16.6, SD = 0.49) were found via social media advertising, requesting that ‘tech-savvy’ youths with lived experience of perfectionism be part of a focus group to provide input into the development of an online intervention programme to reduce perfectionism. YAG members were reimbursed with a $35 Amazon voucher in compensation for their time. Interested YAG participants were first invited to spend a 2-week period viewing and exploring the existing website (Shu et al., 2019) before young people were consulted in focus groups. A semi-structured interview was used to guide the focus group discussions (see Table 1), to explore youth perceptions of perfectionism and mental health, before discussing their specific experiences and thoughts about the Overcoming Perfectionism (Shu et al., 2019) programme. Two focus group meetings were held online, and were between 60 and 90 minute duration each.

Table 1.

Youth Advisory Group focus group questions.

| General questions | 1. How do you define perfectionism? |

| 2. In your experience, how is perfectionism experienced by young people? | |

| 3. In your experience, how is perfectionism relevant for young people with or at-risk of eating disorders? | |

| 4. What do you think are the best formats for an intervention for perfectionism in young people? | |

| Website-specific questions | 5. What did you like about the website/programme? |

| 6. What did you not like, or would change? | |

| 7. What were the most helpful aspects of the programme? | |

| 8. Do you think there is anything else that would be helpful to add? | |

| 9. What did you think of the activities in the programme? | |

| 10. What did you think of the website name? | |

| 11. How did you find the language used on the site? (i.e., was it easy to read and understand?) | |

| 12. What did you think of the images used? | |

| 13. Do you think the website would be easy to use? | |

| 14. Do you have any further opinions you would like to offer? |

The focus groups were recorded and transcribed. Although the YAG was small with 5 members, the perspectives raised in the second focus group were largely consistent with the first focus group, and whilst ongoing consultation with a greater number of youths may have revealed further perspectives, for the practical purpose of time constraint in needing to start the RCT further consultation groups were not conducted.

An outline of the feedback on the website (Shu et al., 2019) that the YAG provided was summarised and emailed to the YAG, as well as a summary documenting the actions taken by the research team to incorporate their feedback and make changes to the programme to make it more appealing and accessible to youth. A new website was then developed to incorporate all of the perspectives that young people had regarding the intervention. A thematic analysis of the focus groups revealed two main sources of feedback: content and aesthetic. Whilst participants expressed enjoying the programme activities, readings, videos, and audio recordings, they felt that the aesthetic and “feel” of the website needed “modernizing”. For example, one young person stated “I think it would be nice if you took more of a photographic approach to it, like less quotes, and more relevant images just to kind of like break up the text.”. Positive feedback from young people in the YAG included feeling that the pitch of the language was right; “It was very supportive as well as being informative”. Young people also endorsed finding the content useful, for example, “I really liked the worksheet things because they kind of forced you to reflect and think on your thought patterns and behaviours, and then kind of I liked the structuring of it as well, because it offered like a clear thing to do”. In summary, our YAG suggested that inspirational quotes were not liked, which resulted in the removal of them, and instead they were replaced with more conceptual images and visual art.

Significant time went into the redesign of the website, including renaming the programme from Be-You-Tiful.com.au which was used in Shu et al. (2019) to YouthPerfectionism.org, and ensuring mobile compatibility which was not available in the previous trial (Shu et al., 2019). The resulting website is an interactive internet intervention which is unguided, and incorporates the views of the young people and their recommendations from our YAG (see Table 2 for an overview of intervention content). After the alterations had been made, the website was then reviewed to ensure fidelity to the treatment protocol, by SE an expert in CBT-P. Only minor typographical changes were required. The current iteration of the ICBT-P ‘Overcoming Perfectionism’ programme, Youthperfectionism.org, has been co-designed by female adolescents with lived experience of perfectionism, the intended end-user demographic in order to be appealing and relevant to young people.

Table 2.

Module overview of the Overcoming Perfectionism online youth intervention programme.

| Module | Content summary |

|---|---|

| 1 - Introduction to perfectionism and welcome | Introduces what perfectionism is, discusses symptoms of perfectionism, discusses how perfectionism can be unhelpful, highlights the negative aspects of perfectionism, as well as acknowledging the difficulty in reducing perfectionism due to the positive outcomes, and finishes with a fun quiz on the content of the module. |

| 2 - The perfectionism cycle | Explores how thoughts and behaviours can perpetuate the perfectionism cycle, provides example formulations, provides blank formulation templates for participants to draw their own perfectionism cycles, and ends with a fun quiz on the content of the module. |

| 3 - Getting started | Discusses the pros and cons of addressing unhelpful perfectionism (short term and long term), highlights areas of life that might be positively impacted by a reduction in perfectionism, includes activities for participants to identify areas of perfectionism that apply to them and the associated thoughts and behaviours, and ends with a fun quiz on the content of the module. |

| 4 - Myth busting | Explores myths that perpetuate perfectionism (cognitive distortions), discusses diminishing returns and effort, and introduces the concept of surveys to help challenge cognitive distortions and to reality test. The module finishes with a fun quiz on the content of the module. |

| 5 - Game plan | Behavioural experiments are introduced, examples are provided, and participants are challenged to develop their own, dichotomous thinking is challenged, continuums are introduced, and the concept of acceptance and compassion are introduced. The module ends with a fun quiz on the content of the module. |

| 6 - The bright side | This module focuses on identifying positives, changing/noticing thinking styles, thought-challenging activities are introduced, further unhelpful thinking styles (cognitive distortions) are examined in detail with activities for participants to reflect on their own thinking. The module ends with a fun quiz on the content of the module. |

| 7 - Procrastination | Overcoming procrastination is explored, along with time management and problem-solving skills. Pleasant event scheduling is discussed and encouraged. Behavioural experiments are proposed to help reduce procrastination and improve time management. The module ends with a fun quiz on the content of the module. |

| 8 - Self-love and forward planning | The final module explores self-compassion, re-defining self-worth, exploring values, and developing an action plan for the future. The module ends with a fun quiz on the content of the module. |

2.4. Participants

We aim to recruit a sample of 196 female, adolescent Australians (aged from 13 to 18 years) in order to assess the efficacy of ICBT-P on reducing symptoms of eating disorders, anxiety and depression. Following other recent RCTs of unguided internet CBT (Egan et al., 2021) an a-priori power analysis following the methods of Dattalo (2013) was conducted. Based on an alpha level of 0.05, 80 % power, a small effect size (f2 = 0.02) and two groups, 190 participants per treatment group will be required. We determined a small treatment effect on the basis of a meta-analysis of unguided internet CBT (g = 0.27; Karyotaki et al., 2017).

The inclusion criteria are: (i) identify as female, (ii) aged 13 to 18 years of age, (iii) reliable access to the internet (iv) access to a general practitioner (in case of risk issues and need for urgent referral), and (v) report elevated symptoms of eating disorder symptoms as indicated by an EDE-Q global score greater than 1.5 (based on norms by Fairburn and Beglin (1994) citing a mean EDE-Q global score of 1.5 in a community sample). Exclusion criteria are: (i) moderate to high suicide risk as indicated by the score on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-Kid) module B1 (3 questions assessing suicidality) (Sheehan et al., 2010) in line with procedures used by (Shu et al., 2019), and (ii) if the participant is currently receiving psychotherapy. Participants are requested to self-report current engagement in therapy, and the researchers consider any ongoing, regular, therapeutic engagement with the explicit aim of treating mental health as therapy; one session supportive contacts are not included. Participants may continue taking any psychotropic medications they are currently utilizing; however they are requested to contact the researchers if they have any changes in medication throughout the trial, and in the 6-month follow-up period.

2.5. Recruitment

Participants will be recruited through social media advertising and schools. School principals, psychologists, and high school wellbeing staff will be contacted with information about the programme, and requested to share the information with students, faculty, and parents. Recruitment via specialty eating disorder services and advocacy groups across Australia (such as the Butterfly Foundation and the National Eating Disorder Collaboration) will also be engaged in, to provide an option for those who may not meet intake or full criteria for an eating disorder and are sub-syndromal, to have the opportunity of instead participating in this indicated prevention study.

2.6. Procedure

This trial has been prospectively registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR; ACTRN12620000951954P). This study protocol and the trial were approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2020-0626) in August 2020. Interested adolescents and/or their parents will be able to register their interest for the study online via www.youthperfectionism.org. This involves reading a digital participant/parent information sheet (parent and child version for adolescents under 16, or a mature minor version for adolescents 16 and over), providing a name and contact email address for the young person as well as for the parent, providing brief demographic information that helps to determine initial eligibility (age, country and state, sex, and whether they are engaged in therapy at present), and digitally signing the consent form.

Participants 16 years and over will be assessed as ‘Mature Minors’ in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council's National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2018). Informed consent will be determined via the following procedure: participants will be required to indicate that they understand what the study involves and the risks/benefits to participating by responding to a brief multi-choice questionnaire. Prospective participants will be advised to seek their parent/caregiver's advice and consent if they do not understand the study requirements, or are unable to correctly answer the informed consent questionnaire. Interested youths who are under the age of 16 will be directed to complete a similar consent procedure, however in addition to their own consent, they are requested to also obtain parental consent as part of the registration process. Participants who meet initial inclusion criteria at this stage (the correct age, sex, location, and status of therapeutic engagement) will be emailed a link enabling them to access and complete pre-test measures which include screening for the final eligibility criteria: suicide risk and level of eating disorder symptomology. Any young person indicating a moderate or high suicide risk, will be contacted (along with their parent, including parents of participants aged 16–17 years) with information on more appropriate emergency and local support services, and informed that they do not meet inclusion criteria to continue with the trial. Excluded participants will be provided with access to the programme to allow them the opportunity to benefit from the intervention, however their data will not be collected, and they will not be included in the trial. Young people with an EDE-Q global score greater than 3.26 (psychometric data on the EDE-Q indicates a mean global score of 3.26 in a clinical paediatric population) (O'Brien et al., 2016) but who meet all other criteria will be accepted into the study, but an email will be sent to them and their parent recommending that they access a specialist eating disorder service, and to inform the researchers once they have commenced treatment. Their data will be collected up until the point where they start engaging in other psychological care. This decision was made on the basis that in Australia it can typically take up to 6 months or longer to access specialist services for eating disorders in adolescents, that relatively few participants were likely to access and commence ongoing therapy prior to the completion of the 6-month follow-up point.

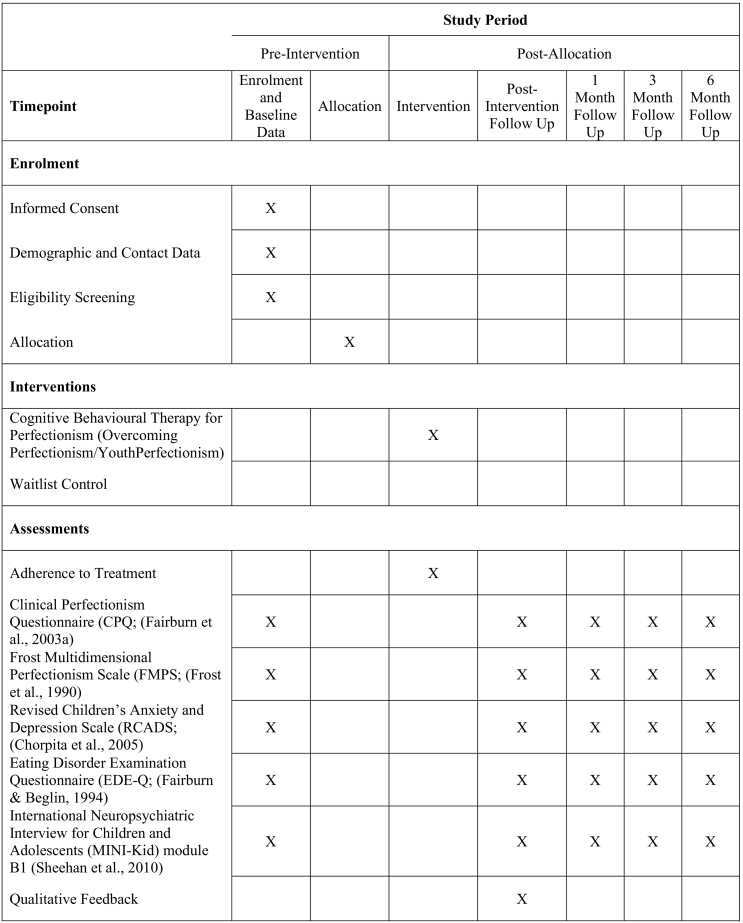

If a participant meets all eligibility criteria, after completion of the pre-assessments, they will be randomly allocated to the intervention or waitlist control group via a random number generator. Simple randomization is being used, concealment from the principal researcher is not possible due to study practicalities of being a PhD led project and is a design limitation Those in the intervention group will be sent the password to the locked section of the www.youthperfectionism.org website, whereby they can then access the Overcoming Perfectionism modules. Participants will be instructed to complete two modules per week, with generic reminder emails being sent to participants for the duration of the four-week programme. The generic emails will prompt participants to login to the programme (link provided in the email) and complete two modules for the week, simply to serve as a reminder. This programme is unguided, with modules ‘unlocked’ to allow participants to move between them as they choose. Users are anonymous on this platform, as no user data is saved, stored, or recorded. Participants are advised to download copies of worksheets to complete, as completing them online will not save their information once they leave the page. In order to access the website platform participants are required to have a login password. This is only given to the participant and held by the study authors. However, no participants are identifiable. Participants will be requested to complete post-intervention measures four-weeks from the date of access. Further follow-up assessment measures will also be emailed to participants at one, three, and six-months post-intervention (see Fig. 2). Those in the wait-list control group will also be sent follow-up assessment measures with the same timeframes outlined above. Following completion of the 6-month post-test, waitlist control participants will be provided with access to the treatment programme. In order to assess for any adverse effects that participants may have experienced, the Reliable Change Index (RCI) will be calculated. The RCI is a measure of reliable change, where a score above 1.96 will indicate change between the pre and post intervention groups, whilst a score below or equal to 1.96 would indicate no change, or potentially an adverse effect (Jacobson and Truax, 1991). Any participants who are identified as having experienced adverse effect following the intervention will have their parent or guardian contacted via email, with the advice for them to attend their GP and seek a referral to a mental health agency or professional.

Fig. 2.

SPIRIT diagram.

2.7. Outcome measures

2.7.1. Clinical Perfectionism Questionnaire (CPQ; Fairburn et al., 2003a)

The CPQ is a 12-item measure of clinical perfectionism that has good internal consistency and concurrent validity with other measures of perfectionism in adult clinical and non-clinical samples (Chang and Sanna, 2012; Egan et al., 2016; Hoiles et al., 2016; Prior et al., 2018; Steele et al., 2011) and adolescents (Shu et al., 2020). The CPQ has often been used as a 10-item measure with the two reverse scored items excluded due to low factor loadings, and is valid as a single total score to measure clinical perfectionism (Howell et al., 2020). The CPQ has good internal consistency (α = 0.83) and strong concurrent validity with anxiety, depression, and stress (Chang and Sanna, 2012). The 10-item measure will be used here.

2.7.2. Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS; Frost et al., 1990)

The FMPS is a well-validated measure of perfectionism that contains 35 questions across six subscales; Concern Over Mistakes, Doubts About Actions, Personal Standards, Parental Expectations, Organization, and Parental Criticism (Frost et al., 1990). In this study only the 9-item concern over mistakes (CM; negative reactions to mistakes) and 7-item personal standards (PS; setting high standards) will be used as an additional outcome measure of perfectionism as these scales are the most clinically relevant subscales of the measure (Shafran et al., 2002) and widely used as outcomes measures in RCTs of CBT-P (Galloway et al., 2022). The FMPS has excellent internal consistency (α = 0.90) (Frost et al., 1990).

2.7.3. Revised Children's Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita et al., 2005)

The RCADS is a 47-item measure that assesses anxiety and depressive symptoms in children from 8 to 18 years of age (Chorpita et al., 2000). It measures symptoms across six subscales: separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and low mood/major depressive disorder. The RCADS is has excellent reliability and validity, with internal consistency of subscales ranging from 0.78 to 0.88 (Chorpita et al., 2005).

2.7.4. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn and Beglin, 1994)

The EDE-Q is a valid and reliable measure of eating disorder psychopathology comprised of four factors; Dietary Restraint, Eating Concern, Shape Concern, and Weight Concern (Fairburn and Beglin, 1994; Fairburn and Cooper, 1993; Fairburn et al., 2003b). The EDE-Q has 28 items which assess eating disorder symptoms over the past month and demonstrates good reliability and validity (Luce et al., 2008; Mond et al., 2006). Internal consistency for each subscale ranges from 0.78 to 0.93, and test-retest correlations range from 0.81 to 0.94 (Luce et al., 2008).

2.7.5. Adherence to treatment

Participants will be requested to complete a brief four-item questionnaire to assess adherence and compliance with the intervention protocol. These items were used by Shu et al. (2019) and derived from a study by Thiels et al. (1998), and include questions such as “How much of the module did you complete?” as well as prompting for a percentage rating of completion.

2.8. Data analysis

The primary outcome is perfectionism, as measured by the CPQ. All other measures of symptoms are secondary outcomes. Intent-to-treat analyses will be conducted using Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM) to examine the interaction between groups (intervention or control) and time, and the main effects between group and time. There will be four time points included (pre-intervention, post-intervention, one-month follow-up, three-month follow up, and six-month follow up). GLMM has been selected for this analysis as it uses all data to model parameter estimates using full information maximum likelihood estimation, and it will used to determine the efficacy of treatment, whilst helping to account for within- and across- participant variability. ‘Participant’ will serve as a nominal random effect, with fixed effect being group (control or experimental), pre-treatment scores operating as covariates, and post-treatment scores as ordinal fixed effects, with a 2-way interaction of group x time. Between-group effect sizes will be calculated using Cohen's d conventions. Following recent pilot work (Hoiles et al., 2022) examining the impact of guided CBT for perfectionism in adults, we will examine the impact of treatment on response and remission rates in our outcomes including perfectionism and psychological symptoms. Any instances of negative or adverse outcomes will also be included in trial reports. No subgroup or interim analyses have been planned. The primary endpoint is the 6-month follow-up period. To account for missing data, we will use robust maximum-likelihood (MLR) estimation in order to account for both missingness and potential non-normal distributions in the data. We plan to analyse data at post-treatment when available from a sufficient sample, then conduct analysis of follow-up treatment data at a later point.

2.9. Ethical considerations

All information gathered from participants is treated as confidential, and will be securely stored on University drives, in de-identified forms, until the completion of the research when the ability to re-identify data will be permanently deleted. Email servers used to communicate with participants is as secure as any email communication, we take care not to associate any data with emails sent to participants, i.e., participants enter questionnaire responses in Qualtrics using a unique code which is stored on the secure University server separate to identifying data.

Whilst waitlist control groups require additional consideration from researchers, as having participants deteriorate or experience negative consequences as a result of being allocated to the waitlist condition, as outlined, currently in Australia where the trial is being conducted, participants wait typically for 6 months or longer to access child and adolescent mental health services. Consequently, being allocated to the control condition is essentially the same process as waiting for other services. After completion of the study, those in the wait-list control group will have access to the treatment programme. The design is in line with the Australian ethical guidelines (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2018), which outlines control groups being ethical and appropriate where participants would otherwise have no recourse treatment that is known to be effective.

3. Discussion

The paper has presented the protocol for a unique trial of an ICBT-P programme that aims to examine the efficacy of unguided ICBT-P as an indicated prevention programme in the treatment of female adolescents at risk for eating disorders on symptoms of eating disorders, anxiety, and depression. Whilst there is evidence that face-to-face CBT for perfectionism is effective for a variety of community and clinical/subclinical populations (Nehmy and Wade, 2015; Vekas and Wade, 2017; Watson et al., 2016; Wilksch et al., 2008), and we know that ICBT-P in community populations is effective in reducing eating disorder symptoms (Shu et al., 2019), it has not yet been demonstrated whether unguided ICBT-P in female adolescents at risk for eating disorders demonstrates efficacy in reduction of eating disorders, anxiety, depression and perfectionism.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Sarah Egan receives royalties from Little Brown Book Group for “Overcoming Perfectionism: A self-help cognitive behavioural treatment” on which the internet intervention is based.

References

- Andersson G. Internet-delivered psychological treatments. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2016;12:157–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E.C., Sanna L.J. Evidence for the validity of the clinical perfectionism questionnaire in a nonclinical population: more than just negative affectivity. J. Pers. Assess. 2012;94(1):102–108. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2011.627962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita B.F., Moffitt C.E., Gray J. Psychometric properties of the revised child anxiety and depression scale in a clinical sample. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005;43(3):309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita B.F., Yim L., Moffitt C., Umemoto L.A., Francis S.E. Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behav. Res. Ther. 2000;38:835–855. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dattalo P. Oxford University Press; 2013. Analysis of Multiple Dependent Variables. [Google Scholar]

- Egan S.J., McEvoy P., Wade T.D., Ure S., Johnson A.R., Gill C., Greene D., Wilker L., Anderson R., Mazzucchelli T.G., Brown S., Shafran R. Unguided low intensity cognitive behaviour therapy for anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a randomised trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2021;144 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2021.103902. 103902-103902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan S.J., Shafran R., Lee M., Fairburn C.G., Cooper Z., Doll H.A., Palmer R.L., Watson H.J. The reliability and validity of the clinical perfectionism questionnaire in eating disorder and community samples. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2016;44:79–91. doi: 10.1017/S1352465814000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan S.J., van Noort E., Chee A., Kane R.T., Hoiles K.J., Shafran R., Wade T.D. A randomised controlled trial of face to face versus pure online self-help cognitive behavioural treatment for perfectionism. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014;63:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan S.J., Wade T.D., Fitzallen G., O’Brien A., Shafran R. A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies of the link between anxiety, depression and perfectionism: implications for treatment. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2022;50:89–105. doi: 10.1017/S1352465821000357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan S.J., Wade T.D., Shafran R. Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: a clinical review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011;31:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C.G., Beglin S.J. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994;16:363–370. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(199412). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C.G., Cooper Z. In: Binge-eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. 12th ed. Fairburn C.G., Wilson G., editors. Guildford Press; 1993. The eating disorder examination; pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C.G., Cooper Z., Shafran R. University of Oxford; Oxford, UK: 2003. Clinical Perfectionism Questionnaire. Unpublished scale. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C.G., Cooper Z., Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003;41:509–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R.O., Marten P., Lahart C., Rosenblate R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1990;14:449–468. doi: 10.1007/BF01172967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway R., Watson H., Greene D., Shafran R., Egan S.J. The efficacy of randomised controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2022;51(2):170–184. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2021.1952302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R.S. An operational classification of disease prevention. Public Health Rep. 1983;98(2):107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve P., Egan S.J., Andersson G., Carlbring P., Shafran R., Wade T.D. The impact of internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism on different measures of perfectionism: a randomised controlled trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2022;51(2):130–142. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2021.1928276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick S.E., Robinson J., Burge E., Blandon R., Mobilio B., Rice S.M., Simmons M.B., Alvarez-Jimenez M., Goodrich S., Davey C.G. Youth codesign of a Mobile phone app to facilitate self-monitoring and management of mood symptoms in young people with major depression, suicidal ideation, and self-harm. JMIR Ment. Health. 2018;5(1) doi: 10.2196/mental.9041. e9-e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill L.S., Reid F., Morgan J.F., Lacey J.H. SCOFF, the development of an eating disorder screening questionnaire. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2010;43(4):344–351. doi: 10.1002/eat.20679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiles K.J., Kane R.T., Watson H.J., Rees C.S., Egan S.J. Preliminary investigation of the reliability and validity of the clinical perfectionism questionnaire in a clinical sample. Behav. Chang. 2016;33:127–135. doi: 10.1017/bec.2016.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiles K.J., Rees C.S., Kane R.T., Howell J., Egan S.J. A pilot randomised controlled trial of guided self-help cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism: impact on diagnostic status and comorbidity. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 2022;76 doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2022.101739. 101739-101739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell J., Anderson R., Egan S., McEvoy P. One factor? Two factor? Bi-factor? A psychometric evaluation of the frost multidimensional scale and the clinical perfectionism questionnaire. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2020;49(6):518–530. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2020.1790645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N.S., Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991;59(1):12–19. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J., Shu C.Y., Hoiles K.J., Clarke P.J.F., Watson H.J., Dunlop P.D., Egan S.J. Perfectionism is associated with higher eating disorder symptoms and lower remission in children and adolescents diagnosed with eating disorders. Eat. Behav. 2018;30:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyotaki E., Riper H., Twisk J., Hoogendoorn A., Kleiboer A., Mira A., Mackinnon A., Meyer B., Botella C., Littlewood E., Andersson G., Christensen H., Klein J.P., Schröder J., Bretón-López J., Scheider J., Griffiths K., Farrer L., Huibers M.J.H., Phillips R., Gilbody S., Moritz S., Berger T., Pop V., Spek V., Cuijpers P. Efficacy of self-guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. JAMA Psychiatry (Chicago, Ill.) 2017;74(4):351–359. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.K., Logan H.C., Young E., Sabee C.M. Youth-centered design and usage results of the iN touch mobile self-management program for overweight/obesity. Pers. Ubiquit. Comput. 2015;19(1):59–68. doi: 10.1007/s00779-014-0808-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limburg K., Watson H.J., Hagger M.S., Egan S.J. The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017;73:1301–1326. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce K.H., Crowther J.H., Pole M. Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for undergraduate women. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2008;41(3):273–276. doi: 10.1002/eat.20504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond J.M., Hay P.J., Rodgers B., Owen C. Jan). Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for young adult women. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006;44(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council . 2018. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007) [Google Scholar]

- Nehmy T.J., Wade T.D. Reducing the onset of negative affect in adolescents: evaluation of a perfectionism program in a universal prevention setting. Behav. Res. Ther. 2015;67:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien A., Watson H.J., Hoiles K.J., Egan S.J., Anderson R.A., Hamilton M.J., Shu C., J M. Eating disorder examination: factor structure and norms in a clinical female pediatric eating disorder sample. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016;49:107–110. doi: 10.1002/eat.22478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior K.L., Erceg-Hurn D.M., Raykos B.C., Egan S.J., Byrne S., McEvoy P.M. Validation of the clinical perfectionism questionnaire in an eating disorder sample: a bifactor approach. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018;51(10):1176–1184. doi: 10.1002/eat.22892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson K., Wade T.D. Perfectionism interventions targeting disordered eating: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021;54(4):473–487. doi: 10.1002/eat.23483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental A., Shafran R., Wade T., Egan S., Bergman Nordgren L., Carlbring P., Landström A., Andersson G. A randomized controlled trial of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for perfectionism including an investigation of outcome predictors. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017;95:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian C.L., Pote I., Wolpert M. Searching for active ingredients to combat youth anxiety and depression. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021;5(10):1266–1268. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01195-5. 2021/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R., Cooper Z., Fairburn C.G. Clinical perfectionism: a cognitive– behavioural analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002;40:773–791. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R., Egan S., Wade T. 2nd ed. Robinson; 2018. Overcoming Perfectionism. [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R., Wade T., Egan S., Kothari R., Allcott-Watson H., Carlbring P., Rozental A., Andersson G. Is the devil in the detail? A randomized controlled trial of guided internet-based CBT for perfectionism. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017;95:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw H., Rohde P., Stice E. Participant feedback from peer-led, clinicna-led, and internet-delivered eating disorder prevention interventions. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016;49:1087–1092. doi: 10.1002/eat.22605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Sheehan K.H., Shytle R.D., Janavs J., Bannon Y., Rogers J.E., Milo K.M., Stock S.L., Wilkinson B. Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID) J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2010;71(3) doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu C.Y., O’Brien A., Watson H.J., Anderson R.A., Wade T.D., Kane R.T., Lampard A., Egan S.J. Structure and validity of the clinical perfectionism questionnaire in female adolescents. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2020 doi: 10.1017/S1352465819000729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu C.Y., Watson H.J., Anderson R.A., Wade T.D., Kane R.T., Egan S.J. A randomized controlled trial of unguided internet cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism in adolescents: impact on risk for eating disorders. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019;120 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele A., O’Shea A., Murdock A., Wade T.D. Perfectionism and its relation to overevaluation of weight and shape and depression in an eating disorder sample. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2011;44:459–464. doi: 10.1002/eat.20817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele A., Wade T.D. A randomised trial investigating guided self-help to reduce perfectionism and its impact on bulimia nervosa: a pilot study. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008;46:1316–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh H., Sohn H., Kim T., Lee D.-G. A review and meta-analysis of perfectionism interventions: comparing face-to-face with online modalities. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019;66(4):473–486. doi: 10.1037/cou0000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiels C., Schmidt U., Treasure J., Garthe R., Troop N. Guided self-change for bulimia nervosa incorporating use of a self-care manual. Am. J. Psychiatr. 1998;155(7):947–953. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacca M., Ballesio A., Lombardo C. The relationship between perfectionism and eating-related symptoms in adolescents: a systematic review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2021;29(1):32–51. doi: 10.1002/erv.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine E.G., Bodill K.O., Watson H.J., Hagger M.S., Kane R.T., Anderson R.A., Egan S.J. A randomized controlled trial of unguided internet cognitive–behavioral treatment for perfectionism in individuals who engage in regular exercise. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018;51(8):984–988. doi: 10.1002/eat.22888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vekas E.J., Wade T.D. The impact of a universal intervention targeting perfectionism in children: an exploratory controlled trial. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017;56:458–473. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade T.D., Kay E., Valle M.K., Egan S.J., Andersson G., Carlbring P., Shafran R. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism: more is better but no need to be prescriptive. Clin. Psychol. 2019;23(3):196–205. doi: 10.1111/cp.12193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wade T.D., Wilksch S.M., Paxton S.J., Byrne S.M., Austin S.B. How perfectionism and ineffectiveness influence growth of eating disorder risk in young adolescent girls. Behav. Res. Ther. 2015;66:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson H.J., Joyce T., French E., Willan V., Kane R.T., Tanner-Smith E.E., McCormack J., Egan S.J. Prevention of eating disorders: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016;49:833–862. doi: 10.1002/eat.22577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilksch S., Durbridge M., Wade T. A preliminary controlled comparison of programs designed to reduce risk of eating disorders targeting perfectionism and media literacy. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2008;47(8):939–947. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799f4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]