Abstract

Background: Refugees are the most vulnerable to mental health problems of all migrant groups. Epidemiological studies measuring the prevalence of mental health disorders in resettled refugee populations have found high rates of psychiatric disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. To investigate the evidence of Social Determinant of Mental Health in Immigrants and Refugees

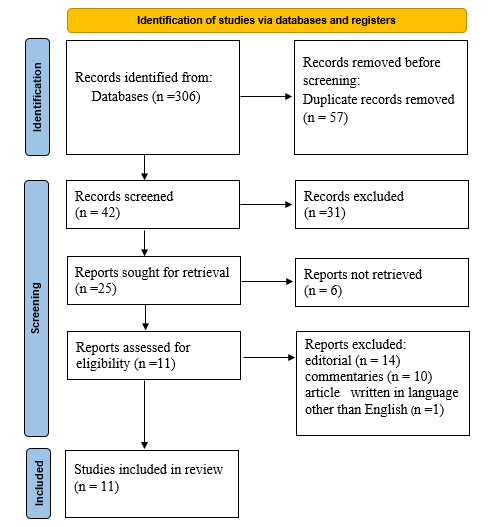

Methods: We searched PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and ProQuest databases electronically. The interval selected for searching articles was between 2000-2021. After selecting articles based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, data were extracted, and the results were summarized.

Results: Among 306 initial studies, 11 studies were the inclusion criteria. In these studies, the target population was people who had immigrated to countries or become refugees for various reasons. In 7 of 11 studies, social factors affecting the mental health of refugees were examined. In four studies, these factors were examined in immigrants. In most studies, social determinants of mental health were common among refugees and migrants.

Conclusion: Improving each of the determinants of health plays an important role in increasing the level of mental health of immigrants and refugees.

Keywords: Social Determinant, Mental Health, Refugee, Immigrant

What is “already known” in this topic

Refugees and asylum seekers flee their countries because of persecution, war, and/or violence, and many are exposed to torture and trauma. Forced displacement of populations has occurred for centuries as a result of ‘persecution, conflict, generalized violence, and human rights violations.

What this article adds

Disparities in social determinants and in mental health outcomes between refugees, immigrants, and domestic-born individuals and between sub-groups of refugees are largely attributable to inequalities in social determinants, including socioeconomic factors, social support, and systemic racism and discrimination.

Introduction

Globally, there are currently almost 80 million forcibly displaced people, including 26 million refugees and over 4 million asylum seekers. Refugees and asylum seekers flee their countries because of persecution, war, and/or violence, and many are exposed to torture and trauma (1). Forced displacement of populations has occurred for centuries as a result of ‘persecution, conflict, generalized violence, and human rights violations (2). The United Nations Refugee Convention defines a refugee as a person who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable to or, owing to such fear, unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country (3).

When a person shifts his residence from one political or administrative boundary to another, it is known as “migration.” Migration is a social phenomenon and can be understood as a part of society. Migration is also called a process of people adapting to a new environment which involves making decisions, preparations, going through the procedure, shifting physically to another geographical area, adjusting to the local cultural needs, and becoming a part of the local system. When a person goes through this process, it will have a definite influence on his/her life as a whole (4).

Migration is a process of population movement either across an international border or within a country (5). Globally, five to ten million people cross an international border yearly to take up residence in a different country with a higher percentage of women than men (6, 7).

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as "a complete physical, mental, and social condition, not merely the absence of disease." Mental health is one of the most important aspects of health, and according to the definition of the World Health Organization, mental health is included in the general concept of health, which is the full ability to play socio-mental and physical roles and not the existence of retardation (8).

SDH is the ‘conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age...[which] are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels (9). SDH can be considered to be ‘the causes of the causes of health inequities' (10). Dahlgren and Whitehead in their influential SDH model, highlight relevant conditions at various levels that affect health - individual factors (e.g., age, sex), individual lifestyle factors (e.g., exercise, smoking), social and community networks, living and working conditions (e.g., education, work environment, housing) and general socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions (11).

The risks for developing mental disorders and poorer mental health are greater for members of groups with less access to power, material resources, and policymaking as a result of broader social, political, and economic factors that sustain inequalities (12, 13).

Refugees are the most vulnerable to mental health problems of all migrant groups (14). Epidemiological studies measuring the prevalence of mental health disorders in resettled refugee populations have found high rates of psychiatric disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety (15, 16).

Migration involves certain phases to go through; hence, it is a process. Many times, lack of preparedness, difficulties in adjusting to the new environment, the complexity of the local system, language difficulties, cultural disparities, and adverse experiences would cause distress to the migrants. Moreover, subsequently, it hurts the mental well-being of such a population (4). Given the importance of the role of social factors affecting the mental health of refugees and migrants, this study examines the evidence on the social determinants of mental health among immigrants and refugees.

Methods

This study reviewed studies involving a social determinant of mental health in refugees and migrants. In this study, articles that examined the social determinant of mental health mental in refugees and migrants during the period 2000 to 2021 were reviewed.

To find suitable studies for analysis, several databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library, ProQuest, were searched. The search strategy was designed by combining keywords. Databases were explored using search keywords, synonyms, and their combination with OR and AND operators to increase search sensitivity. The search strategy for the PubMed database was as follows:

(“mental health”[tiab] OR (Health[tiab] AND Mental[tiab]) OR “Mental Hygiene”[tiab] OR (Hygiene[tiab] AND Mental[tiab])) AND (“health Social Determinant”[tiab] OR “Health Social Determinants”[tiab] OR “Structural Determinants of Health” OR “Health Structural Determinant”[tiab] OR” Health Structural Determinants”[tiab]) AND (“Migrants and Transients”[tiab] OR Transients[tiab] OR Transient[tiab] OR Nonmigrants[tiab] OR Nonmigrant[tiab] OR Squatters[tiab] OR Squatter[tiab] OR “Migrant Workers”[tiab] OR “Migrant Worker”[tiab] OR (Worker[tiab] AND Migrant[tiab]) OR (Workers[tiab] AND Migrant[tiab]) OR Migrants[tiab] OR Migrant[tiab] OR Nomad[tiab] OR “transient and migrants”[tiab] OR Refugee[tiab] OR “Political Asylum Seekers”[tiab] OR (“Asylum Seeker”[tiab] AND Political[tiab]) OR (“Asylum Seekers”[tiab] AND Political[tiab]) OR “Political Asylum Seeker”[tiab] OR (Seekers[tiab] AND “Political Asylum”[tiab]) OR “Political Refugees”[tiab] OR “Political Refugee”[tiab] OR (Refugee[tiab] AND Political[tiab]) OR (Refugees[tiab] AND Political[tiab]) OR “Asylum Seekers”[tiab] OR “Asylum Seeker”[tiab] OR (Seeker[tiab] AND Asylum[tiab]) OR (Seekers[tiab] AND Asylum[tiab]) OR “Displaced Persons”[tiab] OR “Displaced Person”[tiab] OR (Person[tiab] AND Displaced[tiab]) OR (Persons[tiab] AND Displaced[tiab]) OR “Internally Displaced Persons”[tiab] OR (“Displaced Person”[tiab] AND Internally[tiab]) OR (“Displaced Persons”[tiab] AND Internally[tiab]) OR “Internally Displaced Person”[tiab])

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In this systematic review, inclusion criteria were: studies that conducted social determinants of mental health in refugees and migrants; studies with available full-text papers; and studies written in English and published between 2000 and 2021.

This systematic review excluded papers that did not meet the following criteria: Studies that have identified social factors affecting outcomes other than mental health; studies written in languages other than English; and all protocols, conference abstracts, and letters to the editor.

Data Analysis

After searching different databases, all the recovered studies were imported into EndNote software, and the duplicates were removed. The remaining papers were independently studied by two researchers specializing in this field. At this stage, PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) principles were followed to retrieve the final studies. In the first stage, the title and abstract of the studies were reviewed and the relevant papers were selected according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the next step, if the full text of a selected study was available, it was carefully reviewed and the final studies were selected. In each of these stages, if there was disagreement between the two researchers, the studies were reviewed by a third researcher. For each study entering into the final step, a sheet in Excel software was generated to extract the primary data, including author(s) name, year of publication, objectives, setting, social determinant, Outcome variable, and impact social determinant of mental health.

Results

306 articles were found after searching the database. After removing duplicates, 249 articles were included in the study. Of these, 88 studies remained after entering the title and entered the next stage. Abstracts of 88 submitted articles were reviewed, and 42 articles were considered to review the text of the article. The full text of 42 articles was reviewed, of which 31 studies were excluded from the study based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, 11 studies were selected for a more detailed review (Fig. 1.). No new and relevant study was found in the reference review phase of the final articles.

Fig. 1.

Results of the systematic literature search

The data of the articles were extracted using the data form and in the format of a table (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of characteristics and results of included studies .

| Author/Year | Study Design | Objective | Participant | Setting | Social Determinant | Outcome Variable | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell et al/ 2018 (18) | Cross-sectional analyses | To investigate the effect of social determinants, such as employment, language ability and accommodation, on mental health in refugees in the UK | New Refugees (n = 5678), in which all new UK refugees (2005-2007) | UK | language ability, employment status and accommodation satisfaction | Emotional well-being | Refugees who were unemployed in the UK, could not speak English well or were unsatisfied with their accommodation had significantly higher odds of poorer emotional well-being in the cross-sectional analysis |

| Delara et al/ 2016 (19) | Review | To reviews and consolidates findings from the existing literature on social determinants of immigrant women’s mental health within a socioecological framework. | Immigrant Women’s | Canada | Cultural Levels, Social Connections, Social support, Social Influence, Social Position(age, gender role, race, ethnic identity, marital and socioeconomic status), housing, neighborhood, and physical working conditions | Depression, anxiety, Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), low self-esteem, and anger | Findings of this review revealed that mental health of immigrant women is an outcome of several interacting determinants at social, cultural, and health care system levels and hence calls for many different ways to promote it |

| Jessica et al/ 2020 (20) | Randomized Controlled Trial | The goal of this RCT was to rigorously test a social justice approach to reducing high rates distress among refugees in the United States | A total of 290 refugee adults from 143 households | Southwestern United States | Acculturation, English Proficiency(understand, speak, read, and write),Social Support(family ethnic community, and non-ethnic community) | Emotional distress, Anxiety ,Depression | Addressing social determinants of mental health from a strengths-based, holistic approach that aims for multilevel change is effective at promoting the well-being of resettled refugees, including increasing protective factors and reducing emotional distress. |

| Nicholaset al/ 2017 (21) | Qualitative study | 82 documented migrant workers | Singapore | Age, Salary ,Hours/week, Construction | Psychological distress | Migration status places workers who come into workplace conflict with their employers at heightened risk of mental illness. | |

| Mawani/ 2014 (22) | Review | Outline a multi-level framework of determinants of mental health inequities, including macro-, community-, family-, and individual levels of determinants across a continuum from pre-migration to resettlement | Refugee | Canada | Macro-level factors(economic, political, social and physical environments), Community-level Factors(Social Factors, Cultural Factors, Psychological Factors, Built Environment), Family-level factors, Individual-level Factors(Migration Status and Context, Socioeconomic Status). | Mental health | Disparities in social determinants and in mental health outcomes between refugees, immigrants, and domestic-born individuals, and between sub-groups of refugees, are largely attributable to inequalities in social determinants, including socioeconomic factors, social support, and systemic racism and discrimination |

| Michaela Hynie et al/ 2018 (23) | Critical Review | Refugee | Canada | Income, Employment, Housing, Social Support and Social Isolation, Discrimination, Language Skills and Interpretation, The Asylum-Seeking Process | PTSD, distress, and/or depression | ||

| Bukola Salami et al/ 2017 (24) | Cross-sectional survey | Examined the relationship of both self-perceived mental health and reported diagnosis of mood disorders with age, gender, migration status, time since migration, and social determinants of health factors | 12160 participants aged 15–79 years/migrant | Canada | Age, gender, Income, Employment, education, community belonging, Time since immigration | Self-perceived mental health and self-reported diagnosis of mood disorder | |

| Wong et al/ 2017 (25) | Cross-sectional survey | To explore how mapped social determinates of health has impacted the mental health and wellbeing of African ASR’s in Hong Kong | 374 African ASR(asylum-seekers and refugees) population in Hong Kong | African asylum-seekers and refugees in Hong Kong | Gender, Age Group, Marital Status, Biological/Behavioral Circumstances, Place of origin, Length of Residence in Hong Kong, Recreational Drugs, Multiple Sex partners, | Depressive | |

| Hollander/ 2013 (26) | Cross-sectional design | To increase knowledge, using population-based registers, of how pre- and post-migration factors and social determinants of health are associated with inequalities in poor mental health and mortality among refugees and other immigrants to Sweden | I: All immigrants from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, the Middle East, Somalia, and the former Yugoslavia in 2006 II Part 1: All registered immigrants compared with all Swedish-born in the year 2006. Part 2: Immigrants from non-OECD-countries in 2006 who arrived in Sweden since 1993. III Non-labour-market immigrants IV The total population in 2000 2006 with a strong connection to the labour market |

Sweden | Age, education, and marital status, immigrant’s country of origin(ethnicity), employment | Psychotropic drugs, mortality, depressive disorder | The relative risk of hospitalization due to depressive disorder following unemployment. |

| Kim et al/ 2014 (27) | Review | The article will offer best practice recommendations based on the factors identified through the SDMH framework for Southeast Asian refugees | Refugees | Southeast Asian Refugees in United States | Income, education, occupation, social class, gender, race/ethnicity, and nativity status | Mental health | |

| Kuo et al/ 2020 (28) | Cross-sectional research design | To examine and identify predictors of mental health and physical health in a sample of adult Syrian | A total of 235 Syrian refugees | Syrian Refugees in Canada | Educational level, marital status, sex, Family Income, Ethnic group and English proficiency level | Mental health |

Footer For Table 4

Most of the studies conducted in recent years (2014-2020) highlight the importance of social factors affecting mental health among refugees and immigrants in the world. Since most immigrants and refugees migrate to developed countries and these countries are economically well, these studies have been conducted in the developed countries of the world.

In these studies, the target population was people who had immigrated to countries or become refugees for various reasons. In 7 of 11 studies, social factors affecting the mental health of refugees were examined. In four studies, these factors were examined in immigrants.

The population varied in the studies. The largest sample size was 5678 people and the smallest sample size was 82 people.

The studies were designed using cross-sectional studies, reviews, qualitative studies, and clinical trials. 5 studies were performed using cross-sectional study methods, 4 review studies, 1 qualitative method study, and 1 clinical trial study. In all studies, the study aimed to investigate and determine the social factors affecting mental health among refugees and immigrants.

In most studies, social determinants of mental health were common among refugees and immigrants. Age, Gender, Marital Status, Occupational Status, Race, Ethnicity, Housing, Income, English Proficiency, Multi Sex, Partner, Recreational Drugs Social Status, Social Support Within and Outside the Family, Social Influence, Activities and Conditions Physicality, length of stay in the destination country, biological and behavioral conditions, sense of belonging to the community, time of migration and satisfaction with the place of residence were determined as factors affecting the mental health of refugees and immigrants.

In these studies, 9 cases investigated education, 9 cases investigated income, 9 cases investigated employment, 6 cases investigated English language proficiency, 5 cases investigated age, 5 cases investigated marital status, 4 cases investigated gender, 4 cases investigated race, 4 cases investigated social support and 3 of 11 studies investigated Housing as a social factor affecting the mental health of refugees and immigrants.

Outcome variables studied in these studies include emotional well-being, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, low self-esteem, emotional distress, mental distress, self-perceived mental health, and the diagnosis of mood disorder through a person, psychotropic drugs, mortality, and suicide.

In the outcome variables, 5 studies investigated depression, 3 studies investigated nervousness, 2 studies investigated anxiety, and 2 studies investigated post-traumatic stress disorder, which was jointly examined.

Discussion

Different conditions and factors in the path of migration affect the health and mental health of immigrants. The choice of immigration method, the way of settling in the destination country, the ability to adapt to the environment and culture of the destination country, the attitude of the people of the destination country towards immigrants, etc., are examples that affect the mental health of immigrants; But how can this impact be directed in the positive direction of improving the mental health of immigrants?

Most people who choose to be refugees are under psychological pressure. They will experience more stress and psychological problems than other immigrants: Experience of the unsafe route, dealing with environmental hazards, high uncertainty, living in unprincipled camps, etc. Therefore, their mental health will be greatly endangered compared to other immigrants

Research studies from around the world show that migration is a complex process. Migration affects different people in different ways. In other words, migrating without planning and awareness will often be accompanied by stressful events, obstacles, and challenges. If the migration is planned and done with awareness, its consequences are managed, not only it will be successful, but also it will improve the level of mental health and satisfaction of people

The mental health of people who immigrate without knowing the language of the destination country is more at risk than other immigrants. These people are not able to communicate with the people of the destination community. They have difficulty meeting their daily needs and will not have much ability to find friends in the destination country; therefore, to reduce the stress caused by migration and maintain the mental health of people in migration, they should be somewhat familiar with the language of the destination country. This is especially true for people who are migrating to study and obtain a student visa.

Most people who choose to immigrate as refugees do not have the right to return to their homeland. Therefore, they will be separated from their families and relatives sometimes for the rest of their lives. Unfortunately, this greatly affects the mental health of immigrants and will have devastating consequences for them.

The migration process alone does not endanger the health of people; in many cases, it improves their standard of living. Especially if the migration is done correctly and with complete information about the destination country; But if the migration process is not done properly, it can lead to many problems in the mental health of immigrants

According to the latest studies of researchers, the level of economy and welfare of the destination country and the governments' treatment of immigrants will have a direct impact on their health and mental health.

Some factors improve the mental health of immigrants in the destination country. These factors include finding a suitable place to live, getting good job opportunities, joining family members in the destination country, access to better public services, access to better health care, lack of cultural restrictions, and so on

According to our study, social determinants such as age, gender, income, education, housing, employment, English language proficiency, race and ethnicity, and social support are among the factors that have a significant impact on the mental health of immigrants and refugees.

According to the findings of this study, people who migrate at a younger age have more flexibility to adapt to the environment. By accepting the customs of the destination country, these people can adapt more to the environment. But it is difficult for older people to adapt to the customs of the destination country, given that they have lived longer in their own country. Therefore, migration in older people affects their mental health.

The findings of this study showed that gender is one of the factors affecting the mental health of refugees and migrants. In her study, Delara et al. found that women who migrate were at greater risk than men and that their mental health was greater than that of men. People migrate for a variety of reasons, but women usually have their motivations, including joining their family, economic incentives, and educational opportunities, as well as escaping gender discrimination and/or political violence and gaining more social independence. While there are many benefits for immigration, living in a new society poses many challenges for migrant and refugee women. Immigrant women may also face many difficulties in accessing the health care system due to communication, psychological, social, spiritual and religious, structural, economic, and cultural barriers (19)

based on a study by Mawani et al., employment and income are some of the factors affecting the mental health of refugees. These people have lower employment rates than people in the same country. Refugees often live in less economically disadvantaged cities in the destination country, and because of national dispersal policies, refugees are often unable to choose their cities or neighborhoods, so they are forced to live in cities that may be economically viable. It is weak and they cannot get the job they want and have low-income jobs. This makes them unable to meet their basic needs with the income they get from their job. On the other hand, severe financial constraints that force them to live in densely populated low-income neighborhoods cause refugees to face unique mental health challenges (22). Hynie et al. stated in their study that job availability is not for refugees. It is important not only because of income generation but also because of the sense of purpose, identity, and social connection that jobs themselves provide, and the important impact of the physical and psychological social environment of the workplace on mental health (23).

Harrigan stated in his study that immigrants' employment affects their mental health. Threats of deportation generally affect the health of immigrants and harm their mental health (21).

According to Goodkind 's study findings, the impact of post-migration stressors (poverty, lack of access to resources, loss of social support and valuable social roles, discrimination/marginalization, English language proficiency) on refugees' persistent mental health is evident. Since these people spend most of their financial resources and they cannot get a good job in the destination country, their income decreases, and they become poor. On the other hand, they will face the problem of lack of social support in the destination country. These people cannot be successful in social relationships with other people due to a lack of English language proficiency (20).

According to Salami et al.'s study, people who have recently immigrated to Canada feel more belonging to the community, have a higher income, have more well-being, and as a result, have better mental health and lower stress and depression. But immigrants who have been living for 10 years were dissatisfied with their situation and were in worse mental health than the first group (24).

Hollander 's study showed that refugees are in a worse mental health condition than non-refugees. Refugee men have a higher relative mortality risk for cardiovascular disease and external causes of death than non-refugee individuals. The relative risk of hospitalization due to depressive disorder following unemployment is higher among immigrant women (26).

In Campbell et al.'s study, refugees who were unemployed or underemployed, lived in poor housing, had less contact with social support networks, had economic problems, did not have a good understanding of English, and had poor mental health (18).

In their study, Wong et al. supported the relationship between the number of family members and friends in reducing immigrants' depression, which is due to increased social support by family and friends. Immigrants typically have more concerns about the well-being of family members in the host country, often due to limited contact with family members and the stress of prolonged separation. The more contacts a person has with family and friends, the better their mental health will be (25).

Limitations

In this study, it was tried to avoid any bias by conducting a comprehensive and systematic search. However, the failure to follow a standard cost detection approach in the selected studies had reduced the consistency of the reported results; hence, it might prevent the analysis of the reported results on the basis of different dimensions. Most studies have been conducted in developed countries such as Canada, and one study discusses the importance of migration among women, which could be an important issue in future studies. This systematic review study undoubtedly provides very valuable information about the factors affecting the mental health of refugees and migrants for individuals and communities, which shows the importance of the mental health of these people around the world.

Conclusion

Age, sex, marital status, employment, race, ethnicity, housing, income, English language proficiency, multi sex, partner, recreational drugs use, social status, social support inside and outside the family, social influence, activities, and physical conditions, length of stay in the destination country, biological conditions and behavior, sense of belonging to the community, time of migration and satisfaction with the place of residence are important social determinants in the mental health of immigrants and refugees. Improving each of these factors plays an important role in increasing the level of mental health of these people.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

The support provided by School of Health, Torbat Heydariyeh University of Medical Sciences to conduct this study is highly acknowledged

Cite this article as: Rashki Kemmak A, Nargesi SH, Saniee N. Social Determinant of Mental Health in Immigrants and Refugees: A Systematic Review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2021 (31 Dec);35:196. https://doi.org/10.47176/mjiri.35.196

References

- 1.Ziersch A, Miller E, Baak M, Mwanri L. Integration and social determinants of health and wellbeing for people from refugee backgrounds resettled in a rural town in South Australia: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2020 Dec:1. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09724-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.United Nations. UNHCR global trends-forced displacement in 2015. 2016. Geneva, Switzerland

- 3.United Nations. Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. 2011. Geneva, Switzerland

- 4.Virupaksha HG, Kumar A, Nirmala BP. Migration and mental health: An interface. J Nat Sci Biol. 2014 Jul:233. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.136141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.International Organization, International Migration. Glossary on Migration, International Organization of Migration, Geneva, Switzerland, 2004, http://www. iomvienna. at/sites/default/files/IML 1 EN

- 6.Davies AA, Basten A, Frattini C. Migration: a social determinant of the health of migrants. Eurohealth. 2009:10.

- 7.Guruge S, Collins E, Bender A. Working with immigrant women: guidelines for mental health professionals. Can J. 2010 Jul 1:114

- 8.Ganji H. Mental health. Tehran: Arsebaran, Press; 2005

- 9.Social Determinants. https://www. who. int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/

- 10.Marmot M, Allen JJ. Social determinants of health equity. Am J Public Health. 2014:S517. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm. 1991:1–69

- 12.Commission on. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008

- 13.World Health. Social determinants of mental health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014

- 14.Bhugra D, Gupta S, Bhui K, Craig T, Dogra N, Ingleby JD. et al. WPA guidance on mental health and mental health care in migrants. World Psychiatry. 2011:2e10. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Marshall GN, Schell TL, Elliott MN, Berthold S, Chun C. Mental health of cambodian refugees 2 decades after resettlement in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 2005:571e9. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Turner SW, Bowie C, Dunn G, Shapo L, Yule W. Mental health of Kosovan Albanian refugees in the UK. Br J Psychiatry. 2003:444. [PubMed]

- 17.Rashki Kemmak, Rezapour A, Jahangiri R, Nikjoo Sh, Farabi H, Soleimanpour S. Economic burden of osteoporosis in the world:A systematic review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2020 (12 Nov) doi: 10.34171/mjiri.34.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Campbell MR, Mann KD, Moffatt S, Dave M, Pearce MS. Social determinants of emotional well-being in new refugees in the UK. Public Health. 2018 Nov 1 doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Delara M. Social determinants of immigrant women’s mental health. Adv Public Health. 2016 Mar 7

- 20.Goodkind JR, Amer S, Christian C, Hess JM, Bybee D, Isakson BL. et al. Challenges and innovations in a community-based participatory randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Behav. 2017 Feb:123. doi: 10.1177/1090198116639243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Harrigan NM, Koh CY, Amirrudin A. Threat of deportation as proximal social determinant of mental health amongst migrant workers. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017 Jun 1:511. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0532-x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Mawani FN. Social determinants of refugee mental health. InRefuge and resilience 2014 (pp. 27-50)

- 23.Hynie M. The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: A critical review. Can J Psychiatry. 2018 May:297. doi: 10.1177/0706743717746666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Salami B, Yaskina M, Hegadoren K, Diaz E, Meherali S, Rammohan A. et al. Migration and social determinants of mental health: Results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Can J Public Health. 2017 Jul:362. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.108.6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wong WC, Cheung S, Miu HY, Chen J, Loper KA, Holroyd E. Mental health of African asylum-seekers and refugees in Hong Kong: using the social determinants of health framework. BMC Public Health. 2017 Dec:1. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3953-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Hollander AC. Social inequalities in mental health and mortality among refugees and other immigrants to Sweden–epidemiological studies of register data. Glob Health Act. 2013 Dec 1:21059. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.21059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Kim I, Kim W. Post-resettlement challenges and mental health of Southeast Asian refugees in the United States. Best Pract Ment Health. 2014 Oct 1:63.

- 28.Kuo BC, Granemann L, Najibzadeh A, Al-Saadi R, Dali M, Alsmoudi B. Examining Post-Migration Social Determinants as Predictors of Mental and Physical Health of Recent Syrian Refugees in Canada: Implications for Counselling, Practice, and Research. Can