Abstract

A revised purification of acetopyruvate hydrolase from orcinol-grown Pseudomonas putida ORC is described. This carbon-carbon bond hydrolase, which is the last inducible enzyme of the orcinol catabolic pathway, is monomeric with a molecular size of ∼38 kDa; it hydrolyzes acetopyruvate to equimolar quantities of acetate and pyruvate. We have previously described the aqueous-solution structures of acetopyruvate at pH 7.5 and several synthesized analogues by 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-Fourier transform (FT) experiments. Three 1H signals (2.2 to 2.4 ppm) of the methyl group are assigned unambiguously to the carboxylate anions of 2,4-diketo, 2-enol-4-keto, and 2-hydrate-4-keto forms (40:50:10). A 1H-NMR assay for acetopyruvate hydrolase was used to study the kinetics and stoichiometries of reactions within a single reaction mixture (0.7 ml) by monitoring the three methyl-group signals of acetopyruvate and of the products acetate and pyruvate. Examination of 4-tert-butyl-2,4-diketobutanoate hydrolysis by the same method allowed the conclusion that it is the carboxylate 2-enol form(s) or carbanion(s) that is the actual substrate(s) of hydrolysis. Substrate analogues of 2,4-diketobutanoate with 4-phenyl or 4-benzyl groups are very poor substrates for the enzyme, whereas the 4-cyclohexyl analogue is readily hydrolyzed. In aqueous solution, the arene analogues do not form a stable 2-enol structure but exist principally as a delocalized π-electron system in conjugation with the aromatic ring. The effects of several divalent metal ions on solution structures were studied, and a tentative conclusion that the enol forms are coordinated to Mg2+ bound to the enzyme was made. 1H–2H exchange reactions showed the complete, fast equilibration of 2H into the C-3 of acetopyruvate chemically; this accounts for the appearance of 2H in the product pyruvate. The C-3 of the product pyruvate was similarly labelled, but this exchange was only enzyme catalyzed; the methyl group of acetate did not undergo an exchange reaction. The unexpected preference for bulky 4-alkyl-group analogues is discussed in an evolutionary context for carbon-carbon bond hydrolases. Routine one-dimensional 1H-NMR in normal 1H2O is a new method for rapid, noninvasive assays of enzymic activities to obtain the kinetics and stoichiometries of reactions in single reaction mixtures. Assessments of the solution structures of both substrates and products are also shown.

β-Ketolases hydrolyze carbon-carbon bonds of 1,3-diketo substrates, and 10 of these enzymes are cited in the Enzyme Nomenclature listings (37) (EC 3.7.1.1 to EC 3.7.1.10). They are frequently encountered in microbial, plant, and animal cells. A brief survey of their occurrence has been provided recently (28). The role of β-ketolases, like that of other hydrolases, e.g., proteases, lipases, and esterases, is clearly to form intermediary products suitable for processing by central metabolic pathways to carbon dioxide and to contribute to the biosynthesis of cellular constituents for growth or for detoxification. A few natural substances produce 1,3-diketo metabolites that are hydrolyzed by β-ketolases to achieve C-C bond hydrolysis; these include the three aromatic amino acids, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan. A carbon-carbon bond cleavage by kynureninase (EC 3.7.1.3) in tryptophan catabolism is a variant in that the formal “2-amino-4-keto” intermediate, kynurenine, is the substrate for the formation of anthranilate and alanine, which presumably occurs via its “2-imino-4-keto” derivative after condensation with the pyridoxal phosphate prosthetic group of the enzyme (1). The thymol, orcinol, and resorcinol catabolic pathways in different strains of Pseudomonas putida yield 2,4,6-triketo carboxylate intermediates after dioxygenative cleavage of hydroxyquinol substrates (7–9). The different compounds are hydrolyzed to carboxylates and 2,4-diketo carboxylates; orcinol and resorcinol are catabolized via acetopyruvate (Fig. 1A) (8, 9), and thymol is catabolized through 3-methylacetopyruvate (7), before further enzymic hydrolyses. Similar enzymic hydrolyses of vinylogous 1,5-diketones are common when these are formed after meta-ring opening of catechols and quinols in other catabolic pathways (2, 3, 11, 12, 24).

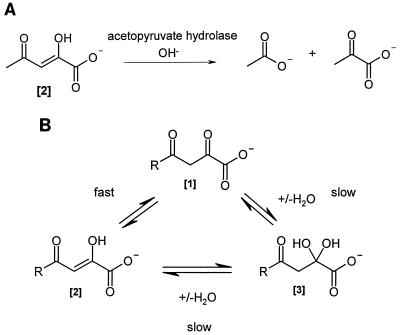

FIG. 1.

(A) The acetopyruvate hydrolase reaction. (B) Main aqueous-solution structures of acetopyruvate (R = CH3) in phosphate buffer at pH 7.5. The proportions for each structural form are approximately as follows: [1]:[2]:[3] = 40:50:10. Interconversion rates are described by Guthrie (17) and given in the text. The structure shown for [2] (enol) is for the protonated enol form at pH 7.5.

Two β-ketolase enzymes have been purified to apparent homogeneity: acetopyruvate hydrolase (EC 3.7.1.6) (10) from orcinol-grown P. putida and the fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (EC 3.7.1.2) used in phenylalanine and tyrosine catabolism, from bovine liver (21). A molecular size of ∼38 kDa was determined for the enzyme from P. putida (10). It was concluded that this enzyme was monomeric by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and native gel electrophoresis, molecular size exclusion chromatography, and ultracentrifugation (10). Data were not shown for the bovine liver enzyme (21). However, fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase accepted acetopyruvate, whereas acetopyruvate hydrolase from P. putida did not catalyze the hydrolysis of several β-diketo acids such as fumarylacetoacetate. Acetoacetate, oxalate, and the product pyruvate were competitive inhibitors of the bacterial acetopyruvate hydrolase (10).

Acetopyruvate hydrolase from rat liver extracts (EC 3.7.1.5) was first described by Meister and Greenstein (Fig. 1A) (23). Although this enzyme was not extensively purified, Meister and Greenstein were able to show the hydrolysis of several diketo acids with longer-chain alkyl groups replacing the methyl group of acetopyruvate, indicating that 4-substituted 2,4-diketo acids possessed the structural prerequisites for binding at the active site(s); acetoacetone was not a substrate for hydrolysis for either of the liver enzymes or the inducible acetopyruvate hydrolase from P. putida. In our previous study of acetopyruvate hydrolase from P. putida (10), 2,4-diketocarboxylate substrate analogues were not available to us, and thus examination of the specificity was extremely limited. We have synthesized a variety of 2,4-diketo carboxylic acids with larger alkyl substituents attached to the 4-position, replacing the methyl substituent at C-4 with branched-chain, alicyclic, and arene substituents (5), and we now describe a spectrum of the substrate specificity of the bacterial enzyme.

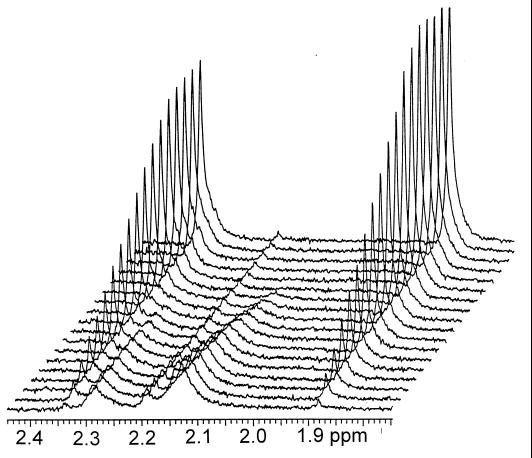

The easiest and most rapid assay for acetopyruvate hydrolase is by UV. The 2,4-diketo acids have characteristic absorption maxima in the 285- to 340-nm range, depending on the individual compound (27). However, the hydrolysis products require individual analyses after derivatizations, extractions, separations, and measurements, e.g., by absorbance, high-performance liquid chromatography, or gas chromatography. Proton-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements in situ, although relatively insensitive, offered an alternative assay for both reaction kinetics and stoichiometries with single reaction mixtures (Fig. 2). The value of 1H-NMR enzymic assays in 1H2O is shown here.

FIG. 2.

1H-NMR stack plot of the acetopyruvate hydrolase-catalyzed cleavage of acetopyruvate (enol form, 2.15 ppm; keto form, 2.28 ppm; hydrate, 2.19 ppm) to acetate (1.88 ppm) and pyruvate (2.34 ppm) in the presence of Mn2+ ions. Spectra were taken every 13 min.

Previously, Guthrie (17) had analyzed the proton spectra of acetopyruvate and its protonated forms in organic solvents and aqueous buffers, pH 1.5 to 6.5, with continuous-wave spectrometers, 60 and 100 MHz. We have used routine one-dimensional (1D) pulse sequences with Fourier transform (FT)-NMR spectrometers and confirmed his observations and conclusions and at the higher pH values used for the enzyme assays. We used normal water as a solvent, and we used a presaturation pulse sequence to suppress the massive proton signals, which would otherwise saturate the analogue digital converter of FT spectrometers and thus conceal or distort some signals of interest in the 3.5- to 5.5-ppm region.

The substrates used were synthesized by Claisen condensations, and their structures were confirmed by the usual spectroscopic methods (5). Guthrie’s experiments (17) showed that there are three main aqueous solution structures of the acetopyruvate carboxylate anion which are in equilibrium: 2,4-diketo, 4-keto-2-enol, and a 4-keto-2-hydrate (Fig. 1B). (Enol-enolate equilibrium at a pH of ∼7.5 is discussed by Guthrie [17] and Brecker et al. [5]. We use the term “enol” to describe this here.) There are large differences in the proportions of these equilibrium structures, which are influenced by pH values, metal ions, and the nature of the terminal substituents (5). The substrate specificity of the β-ketolase induced in P. putida is described. Some isotopic chemical and enzyme-catalyzed “virtual reactions” (1, 34) were examined. The main conclusion is that the aqueous-solution structures of different analogues, and not the formal diketo structure used to describe the pure crystalline solid or liquid forms of some analogues, are of paramount importance for the occurrence of enzymic hydrolysis. This was shown by 1H-NMR experiments (5, 28, 30a).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial and culture conditions.

P. putida ORC (9) was grown in minimal medium (25) supplemented with glucose (20 mM), orcinol (5 mM), and Lab-Lemco (Oxoid) (0.1%) in a 14-liter fermentor (New Brunswick Scientific Inc.) for 16 to 24 h at 30°C. Lab-Lemco broth cultures (2 × 7 ml) were added to the medium defined above (2 × 200 ml), and the cultures were incubated at 30°C for 16 to 30 h, with shaking. These cultures were used to inoculate the fermentor (10 liters of medium) and were aerated at ∼8 liters min−1 and stirred at 300 rpm. After the orcinol was exhausted (16 to 24 h), 1 M glucose (100 ml) and 0.5 M orcinol (100 ml) were added, and they were added again after ∼10 to 16 h. Two to six further similar additions were made after the orcinol was used up, and the cultures were harvested and resuspended in 50 mM KH2PO4–NaOH buffer at pH 7.5, then stored at −14°C. Extracts were prepared by cell disruption using a French press (25).

Acetopyruvate hydrolase assays and purification.

The routine rapid UV assay was used (10) for monitoring the purification procedure, which included two chromatographic separations on a hydrophobic-interaction chromatograph (XK 16; Pharmacia) and an ion exclusion column (IEC) (Q6; Bio-Rad); this is a modification of the previous procedure (10) to take advantage of the chromatographic supports presently available and fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC). Crude cell extracts (supernatants from centrifugation at 105,000 × g) prepared in 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.8, were treated with (NH4)2SO4 after a protamine sulfate precipitation. The proteins that precipitated between 30 and 70% saturation were redissolved, dialyzed, and separated by FPLC on phenyl Sepharose (XK16; Pharmacia) by elution with a 0.0 to 2.0 M KCl stepwise gradient in phosphate, pH 6.8. An active fraction, eluted with 0.2 M KCl, was equilibrated in 10 mM imidazole buffer, pH 6.8, applied to an IEC (Q6; Bio-Rad), and fractionated with a 0.0 to 1.0 M linear KCl gradient in the buffer. Fractions 14 to 16 were examined by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (see Fig. 3), which indicated that one major protein was present. It did not catalyze the hydrolysis of acetopyruvate unless EDTA or Mg2+ ions were added (see Results and Table 2). An electrophoretically pure protein (SDS-gel electrophoresis) with a molecular size of ∼38 kDa was obtained (purification, 69-fold; yield, 71%; specific activity, 4.8 μmol min−1 mg−1). The enzyme was stored at 4°C for immediate use and at −14°C for 2 to 6 months.

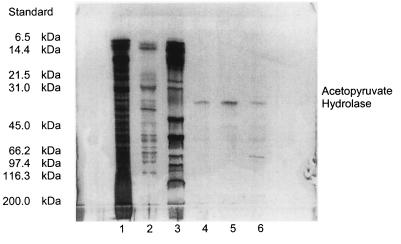

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE of purified acetopyruvate hydrolase and molecular size standards. Lane 1, crude cell extract; lane 2, after HIC; lane 3, SDS-PAGE standard proteins; lanes 4 to 6, sequential fractions 14, 15, and 16 after IEC. (Fractions were eluted with ∼0.2 M KCl.)

TABLE 2.

Effects of divalent metal ions on hydrolytic activity with acetopyruvate as the substrate

| Metal iona | Relative activity on acetopyruvate (%)b |

|---|---|

| Cu2+ | 0 |

| Cd2+ | 60 |

| Fe2+ | 80 |

| No metal ion | 100 |

| Ni2+ | 100 |

| Ca2+ | 100 |

| Mg2+ | 240 |

| Zn2+ | 280 |

| Mn2+ | 760 |

The concentration is equimolar to the substrate concentration (0.1 mM).

Relative to a reaction rate of 100% with no metal ions added (IEC and EDTA).

Chemicals.

Medium chemicals and chromatographic supports were obtained from commercial sources. 2,4-Diketo acid analogues were synthesized as potential substrates and were fully characterized. Their aqueous-solution structures in equilibrium were characterized under a variety of conditions, including the effects of pH, divalent metal ions, and the unwanted side reaction of an intermolecular aldol condensation to produce dimers in 10 to 30 h during storage of the solutions at 20°C (5). We used 1H-NMR and UV spectroscopy for these purposes.

1H-NMR assays of acetopyruvate hydrolase reactions.

All spectra were measured on a Varian Gemini-200 or on a Varian Unity-600 by using a 5-mm broadband probe head. The enzymic transformations and parallel measurements were carried out in a commercial NMR sample tube (outer diameter, 5 mm; length, 178 mm) rotating at 20 rps in the NMR machine. The substrates (20 mM) were dissolved in 100 mM aqueous phosphate buffer at pH 7.5 and added to the NMR sample tube (0.7 ml). A 20% (vol/vol) D2O solution or a D2O vortex capillary tube (22) was added for a lock signal. After a test measurement and field homogenization (shimming), the enzyme was added. The amount of enzyme was calculated so that complete cleavage of the substrate took place in 4 to 8 h. Then 18 spectra were recorded. For each spectrum, 128 scans were accumulated in about 13 min (200 MHz) or about 6 min (600 MHz). The spectra with the 4-tert-butyl substrate were taken with 16 scans (80 s) and no delay. All the spectra were referenced to the H2O signal (4.70 ppm), and for the suppression of the water signal, the presaturation method (16, 20) was used for the 200-MHz NMR and the WET (water suppression enhanced through I1 effects) method (26, 33) was used for the 600-MHz NMR. The following parameters were adjusted for a 1H frequency of 200 or 600 MHz (5): a presaturation duration of 1.0 s (at 200 MHz), a 1H pulse angle of 90°, an acquisition time of 2.0 s, and a relaxation delay of 1.5 s.

RESULTS

Acetopyruvate hydrolase.

Acetopyruvate hydrolase was purified to apparent homogeneity from P. putida ORC by an alternative purification procedure (Table 1). It showed the same characteristics as the previous preparation from P. putida 01 (10). It was electrophoretically pure (by SDS-PAGE and PAGE) and was characterized as a monomeric protein with a molecular size of ∼38 kDa (Fig. 3) and with no evidence of subunit structure in the native enzyme. Enzymic activity was enhanced by several divalent metal ions, e.g., Mg2+ and Mn2+, but was inhibited by Cu2+ ions (described below).

TABLE 1.

Purification of acetopyruvate hydrolase from P. putida ORC

| Enzymea | Total amt (U) | Protein mass (mg) | Sp act (U/mg) | Total activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude cell extract | 62.4 | 840.0 | 0.07 | 76.4 |

| Product of 2nd (NH4)2SO4 precipitation | 81.6 | 510.0 | 0.16 | 100.0 |

| HIC product | 61.2 | 65.5 | 1.16 | 75.0 |

| IEC productb | 44.6 | 9.3 | 4.8 | 54.6 |

For a description of the purification procedures, see Materials and Methods.

None of the IEC fractions were enzymatically active alone. Assays for the IEC fractions contained Mg2+ ions (1.0 mM).

The 1H-NMR assay of enzymic activity.

Guthrie (17) had clearly shown by 1H-NMR that three major aqueous-solution forms of acetopyruvate exist at pH values of 1.5 to 6.5. We confirmed this with 1H-NMR-FT spectra and obtained a pKa of about 7.5 for the α-keto-enol tautomers of the carboxylate anions (Fig. 4) (5, 17). This was important to show which solution structure was the actual substrate for the hydrolysis reaction (Fig. 1 and 2).

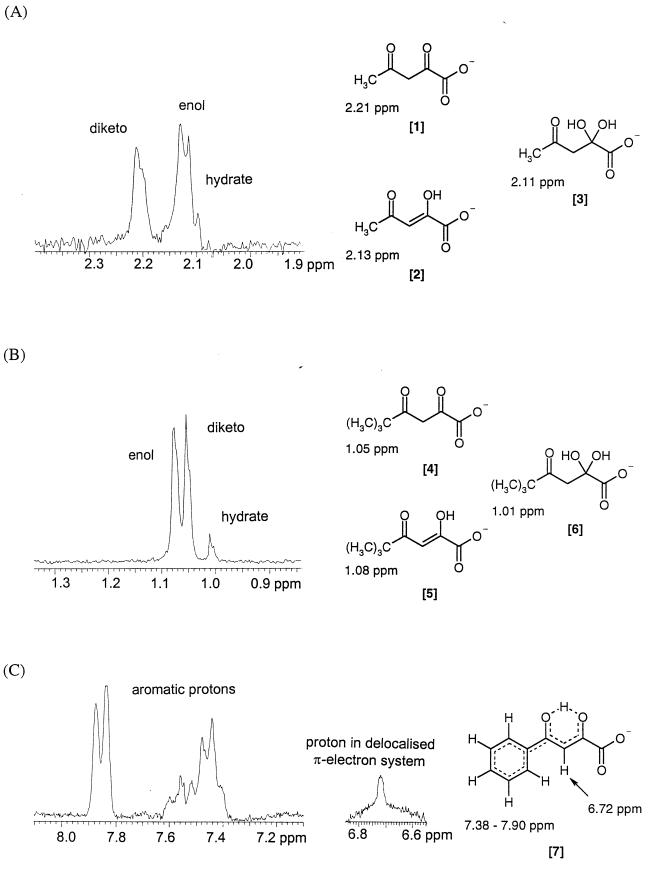

FIG. 4.

1H-NMR spectrum of acetopyruvate (A) and two analogues (B and C) at pH 7.5.

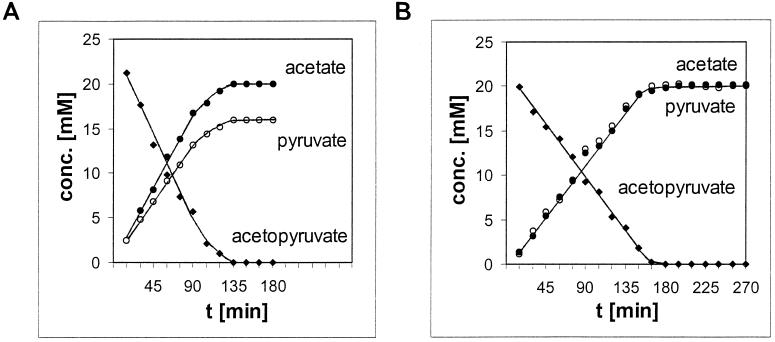

The first 1H-NMR experiments to measure the acetopyruvate hydrolase reaction did not give the expected equimolar production of acetate and pyruvate that had been established by chemical analysis (10). The apparent molar yield of pyruvate was ∼20% lower than that of acetate. The substrate was completely used up during the reaction, as shown by UV assay, 1H-NMR spectroscopy, and chemical assays (Fig. 5A). 2H2O (20%, vol/vol) had been used as a lock signal for the NMR experiments, and chemical proton exchange had occurred into the C-3 position of acetopyruvate (5). This was confirmed by separating the 2H2O from the reaction mixture in a capillary tube used for the lock (5, 22), which restored the measured equimolar stoichiometry (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Comparison of the progress of acetopyruvate hydrolysis by the hydrolase with the 2H2O lock signal provided internally (A) or externally in a capillary tube (B).

The nonenzymic exchange of 2H into acetopyruvate, acetate, and pyruvate was examined. Only acetopyruvate received 2H, but this reaction was too rapid for kinetic measurements on the NMR timescale. Enzyme-catalyzed exchange of 2H was different in that both acetopyruvate and pyruvate, but not acetate, were labelled in proportion to the amount of 2H2O provided in the reaction mixtures. All subsequent experiments used the 2H2O lock in a capillary tube in order to avoid the complications of 2H–1H exchange reactions.

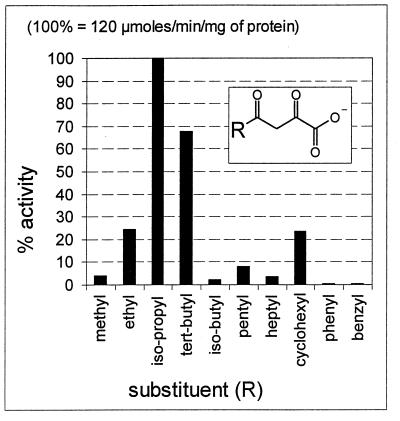

Substrate specificity.

Twelve substrate analogues were synthesized, and their aqueous-solution structures were unambiguously characterized (5). These analogue substrates gave a surprising spectrum of hydrolysis rates (Fig. 6). Acetopyruvate itself could be regarded as a very poor substrate; its rate of hydrolysis was ∼20 times less than that for the 4-iso-propyl homologue (100%), while that for the 4-tert-butyl analogue was 68%. Even with a cyclohexyl substituent at the C-4, the hydrolysis rate was higher (25%) than that for acetopyruvate (4%). In contrast, analogues with 4-phenyl or 4-benzyl substituents were very poor substrates (<1%) (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Substrate specificity of acetopyruvate hydrolase without added metal ions. Data are taken from the UV assays and were confirmed by the 1H-NMR method. Substrate concentrations for the two assays were 0.1 mM (UV) and 20 mM (NMR).

Effects of metal ions on hydrolase activity.

Several bivalent metals markedly stimulated activity (Table 2). A Michaelis-Menten plot of the Mg2+ ion concentrations with acetopyruvate as the substrate gave apparent Km and Vmax values of ∼1.7 mM and 4.8 μmol min−1 mg of enzyme−1 in the presence of Mg2+ ions. Mn2+ ions were more effective at lower concentrations than Mg2+ ions (Table 2) (10). After enzyme purification with the Cu2+ column (IEC), enzymic activity was not detected in collected fractions in the usual UV assay, but the addition of EDTA and several divalent cations to the assay mixtures restored activity. They presumably build a complex with Cu2+ ions eluted from the copper column. These observations were substantiated as shown in Table 2.

Mg2+ ions did not stimulate the low hydrolase activity observed with the arene-substituted analogues. These and other observations will be briefly discussed later, but a detailed analysis is not the purpose of this work.

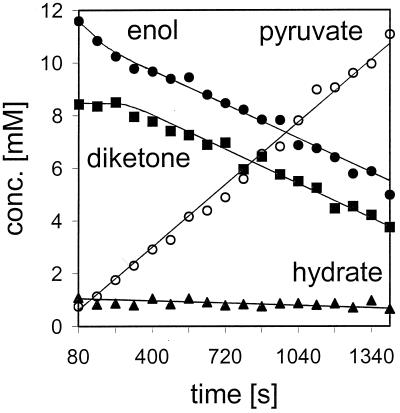

What is the aqueous-solution structure for hydrolysis?

We needed a fast and more-sensitive 1H-NMR assay to establish that it is the enol form which is hydrolyzed. 4-tert-Butyl-2,4-diketobutanoate (5,5-dimethyl-2,4-dioxohexanoate) (Fig. 4B) was used as the substrate for these experiments at concentrations of about 20 mM. The tert-butyl group has 9 equivalent protons and gives one singlet for each solution structure (enol, 1.08 ppm; diketo, 1.05 ppm; hydrate, 1.01 ppm). That is three times more sensitive than the methyl group signals in acetopyruvate. The three characteristic proton singlets were obtained in ∼80 s, i.e., a spectrum could be displayed from 16 scans. Figure 7 clearly shows that the enol form was rapidly hydrolyzed first, during the first 300 s of the reaction time, while the concentrations of the diketo and hydrate structures remained constant. Thereafter, the enol and diketo forms disappeared at similar rates, while the hydrate was very slowly depleted (∼10%). The experiment was repeated four times, showing this “burst” phenomenon, as with serine hydrolases (1, 13), followed by a rate determined by the rate constants for equilibrium of the two tautomers. As Guthrie showed, and we confirmed, the time to equilibrium of the keto-enol mixture is short (κ = 0.1 s−1) compared to the time to equilibrium of the hydrate to the tautomers (κ = 0.012 s−1) at pH 5 (Fig. 1) (5, 17). The relative rates of disappearance of the three forms are shown in Table 3, with data taken from Fig. 7.

FIG. 7.

Disappearance of the three structural forms of 4-tert-butyl-2,4-diketobutanoate and formation of pyruvate in aqueous solution.

TABLE 3.

Initial and steady-state hydrolysis rates of the three solution structural forms of tert-butyl-2,4-diketo butanoatea

| Time(s) | Change in concn (μmol s−1) of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enol | Diketone | Hydrate | Pyruvate | |

| 0–300 | −8.6 | ±0 | −0.15 | 7.7 |

| 300–1,800 | −4.6 | −3.9 | −0.15 | 7.7 |

Initial rates, 0 to 300 s; steady-state rates, 300 to 1,800 s. Data are taken from Fig. 7.

Acetopyruvate at pH 7.5 and room temperature forms a dimer by a Claisen-type condensation (5). This dimer is not a substrate for the enzyme (data not shown), even though it does provide an enol form. Substitution of the C-3 position may make the substance unacceptable.

DISCUSSION

Three main topics are discussed below: (i) the central role and ubiquity of β-ketolases in general metabolic processes, mostly peripheral, (ii) the development of the proton-NMR method to monitor enzymic reactions in normal 1H2O and in 2H2O, and (iii) the importance of understanding the aqueous-solution structures of substrates provided to enzymes and the preference shown for analogues of 2,4-diketobutanoates with large substituents at the C-4 position.

β-Ketolases.

It is clear that β-ketolases (EC 3.7.1.[1 to 10]), which catalyze carbon-carbon bond hydrolyses, are frequently used in catabolic pathways (28). Carbon-carbon bond synthesis by these enzymes is energetically unfavorable in H2O, and alternative thioester substrates with suitable leaving groups, e.g., CO2, have been evolved to achieve this purpose. β-Ketolases are ideal for catabolic processes once 1,3-diketo functionality has been introduced by oxidation reactions, and thus they represent an alternative to aldolases, thiolases, decarboxylases, oxygenases, etc., for fragmentation of the carbon skeletons of organic molecules. Most β-ketolases described so far are intracellular enzymes, but for the biodegradation of polyvinyl alcohols, extracellular versions (EC 3.7.1.7) are produced by some microorganisms (28, 31). It is not known if any of these enzymes also catalyze retroaldol reactions of partially oxidized 1-hydroxy-3-keto intermediate polymers, which are undoubtedly formed initially by the extracellular oxidase(s) (18, 28, 31, 35). Like the expression of the intracellular β-ketolases, that of the extracellular enzymic activities is specifically regulated by the provision of suitable precursor substrates, usually presented as growth substrates, that are oxidized to 1,3-diketones.

Acetopyruvate hydrolase(s) is induced by the growth of many bacteria with acetogenic (polyketide) natural products, e.g., resorcinols and safroles; so, by inference, are other β-ketolases, since 1,3,5-triketo intermediates frequently occur in these catabolic pathways (3, 7–9, 28). We studied an acetopyruvate hydrolase (EC 3.7.1.6) from orcinol-grown cells of P. putida 01 previously (10). The purpose of the present study was to examine the specificity of this enzyme with recently synthesized substrates, by using the normal UV assays, and to explore also the versatility of the routine 1D-proton-NMR methods described below for kinetics and stoichiometries.

The proton-NMR method.

The proton nucleus is present in almost all biological molecules. Proton-NMR spectra can be very definitive for diagnostic purposes and are useful for crude quantitative analyses (±5%), but their use for studies of this kind, to describe metabolic experiments in normal 1H2O, is rare in the literature (19, 28, 38). Experiments with nuclei other than protons have frequently been used to understand metabolic processes, including the transport of intermediates and ions across membranes and cells, since the 1970s (14, 25, 28, 32). We have found that the proton nucleus is very suitable for the analysis of enzymic reactions and those catalyzed by growing and nongrowing bacterial cell suspensions in situ (6, 19, 25, 30, 38). This is a relatively insensitive method, but it is entirely satisfactory when substrates, intermediates, and products are in high concentrations (≥1 mM) and the signals are not multiple nor coupled to neighboring protons or other nuclei in the substrates, although this also provides valuable information.

Acetopyruvate is enzymically hydrolyzed to equimolar quantities of acetate and pyruvate (Fig. 5) (10). Thus the “isolated” methyl group signals of the substrate and of both products seemed ideal markers for monitoring the entire reaction progress by 1D-proton-NMR. The major problem was to suppress the very large 1H2O signal (4.70 ppm; ∼114 Meq liter−1) because it saturates the ADC of FT spectrometers, and small signals of interest cannot then be seen. One possible solution is to use 2H2O as a solvent, but even with 99.9% 2H2O, the residual proton signal can be 100 times (∼114 meq liter−1) those of the substrates and products of interest (15, 30). Two major additional problems arise with the use of 2H2O as a solvent: (i) the kinetic isotope effects that affect the reaction rates observed and (ii) 2H–1H exchange into substrates and products. The unknown effect of 2H2O on enzyme solution structures must also be considered. For these reasons we used one of the established pulse sequences to presaturate the water signal (5, 16, 20) or to suppress it by selective coherence transfer (26, 33).

We did initially observe considerable isotopic exchange in the acetopyruvate hydrolase reaction and a rapid chemical exchange into the substrates. This occurred with the addition of 20% (vol/vol) 2H2O to reaction mixtures for a lock signal. The yield of pyruvate was apparently 20% lower than that obtained by the chemical analysis. A 2H–1H exchange had most likely occurred, chemically or enzymically, into the methylene (C-3) group of acetopyruvate. Alternatively, exchange into the methyl group of the product pyruvate had occurred. In independent experiments (data not shown) we established that this was a facile chemical exchange reaction for acetopyruvate, but exchange into pyruvate was enzyme catalyzed. When the 2H2O lock was provided externally in a capillary tube within the NMR tube, equimolar relationships of the enzyme reactions were restored, as observed by NMR analysis (Fig. 5).

Aqueous-solution structures of substrates and acetopyruvate hydrolase specificity.

The NMR experiments had shown that most 2,4-diketo acids exist in three main aqueous-solution structural forms at pH 7.5 (Fig. 1B) (5, 17): the carboxylate anions of 2,4-diketo, 2-enol-4-keto, and 2-hydrate-4-keto forms (∼40:50:10). Exceptions to this were two arene analogues, 4-phenyl- and 4-benzyl-2,4-diketobutanoate (Fig. 4). They gave broad proton signals (∼30 Hz line width at half-high) inconsistent with the structures assigned to their aliphatic and alicyclic counterparts. By using detailed 2D-NMR analyses (heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence and heteronuclear multiple bond correlation) it was suggested that a π-delocalized electron distribution occurred between the 2- and 4-keto functions (Fig. 4) to form a quasi-six-membered ring with cations (5). Further support for this proposal was provided by the chelation complexes with divalent metal ions. Thus Mg2+ and Mn2+ ions formed chelates between the 2-enol and carboxylate anions of the aliphatic acids, whereas the two keto (2 and 4) oxygens (Fig. 4) formed a delocalized π-electron system in conjugation with the arene substituents. In this respect the structures deduced for Cu2+ ion chelates entirely supported the two very different aqueous-solution structural forms of the alkyl and aryl analogues (5).

We examined the substrate specificity of acetopyruvate hydrolase with three questions in mind. How much tolerance does the enzyme possess to accept 4-substituted substrate analogues for binding or for a productive catalytic reaction? What is the actual aqueous form that is used for the enzyme-catalyzed reaction? How do divalent metal ions affect (stimulate or inhibit) enzymic activity? Some answers to these questions are given here and in Results.

First, the sizes and shapes of the various 4-substituted analogue substrates accepted for hydrolyses gave some surprising results. An extraordinary feature is that bulky aliphatic branched-chain substrate analogues and an alicyclic analogue are much better substrates than acetopyruvate itself, with the standard UV or NMR assays used (Fig. 6). The hydrolytic activities observed with branched-chain substituents are particularly remarkable: the iso-propyl analogue is hydrolyzed ∼20 times faster than acetopyruvate, the substrate formed in the orcinol and resorcinol pathways for which acetopyruvate hydrolase had presumably been evolved. One possible explanation of this specificity is that these hydrolytic enzymes with a preference for the iso-propyl functionality were selectively evolved for the biodegradation of terpenoid structures. There is suggestive evidence for this from some established monoterpene catabolic pathways, namely, those for d- and l-camphor (39) and some aromatic terpenoid equivalents such as thymol (7) and p-cymene (11), all of which yield iso-butyrate by hydrolytic reactions of a 1,3-diketone (thymol) or a vinylogous 1,5-diketo analogue (p-cymene). With respect to camphor biodegradation, it is significant that the initial oxidative reactions lead to 1,4-diketones that are processed further not by hydrolysis but by spontaneous chemical rearrangements (39). The logic of the proposed chemical mechanism for the hydrolysis of the diketones is rational. 1,3-Diketones or vinylogous 1,5-diketones are suitable for carbon-carbon bond hydrolysis, whereas 1,4-diketones are not; the latter require oxygenative reactions to form lactones and break a carbon-carbon bond, and they rearrange spontaneously to monocylic intermediates (36, 39).

2,4-Diketo carboxylate substrates with different ring substituents in the 4-position represent interesting contrasts and allow some conclusions to be made. The 4-cyclohexyl analogue is a good substrate (∼10 times faster than acetopyruvate), but the arene substituent homologues are not. Therefore, we propose that there is not a geometrical exclusion of arene substrates for binding to the enzyme. Instead, the solution structures of the arene analogues probably account for their inadequacy as competent hydrolytic substrates for this enzyme. This is also supported by the solution structures proposed with a delocalized π-electron system predominating for the arene substrates (5). There is little or no enol structure available for hydrolysis (see below). Possible competitive binding with the arene analogues was not investigated.

Structure of the substrates for hydrolysis.

To determine the structures of the substrates used for hydrolysis, we had to conduct high-sensitivity proton-NMR experiments. Since the 4-tert-butyl analogue was a good substrate (Fig. 6) and could be used at relatively high concentrations, it was the choice for these experiments. The increased sensitivity for proton-NMR analysis afforded by this substrate gave data that led to the conclusion that the enolate-dianion structure was the preferred substrate for hydrolysis. The data shown in Fig. 7 suggest this, since the enol was consumed early in the reaction while the concentrations of the diketo and hydrate forms remained constant. Thereafter, the enol and diketo isomers disappeared at similar rates and the hydrate disappeared very slowly. This can be explained by the kinetic equilibrium constants for these molecular species (5, 17), in that the hydrolysis rate may become limited by the relatively fast keto-enol interconversions to equilibrium (17). These experiments required short accumulation times of 80 s for each spectrum to be obtained (16 scans) at the earliest times of the enzymic reactions (Fig. 7).

Equilibrium of structural forms in aqueous solution also seems important for the substrates for other enzymic reactions, e.g., for glucose-fructose (xylose-xylulose) isomerase reactions. For the isomerization of an aldose to a ketose, only the linear aqueous-solution isomer appears to be used (37).

Divalent metal ions and hydrolase activity.

We had previously shown that Mg2+ and Mn2+ ions markedly stimulated the enzymic hydrolysis of acetopyruvate and that Mn2+ was more effective than Mg2+ at 1/10 of its concentration (10). A chance observation was made during the purification of acetopyruvate hydrolase on a Cu complex column (IEC). Activity was not recovered in any eluted fraction, but when EDTA was added to reaction mixtures, the hydrolase was functional again. Some Cu2+-protein interaction seemed to have occurred, which was reversible by the counterion, EDTA, and was stimulated further by Mg2+ or Mn2+ ions. This was not investigated in detail.

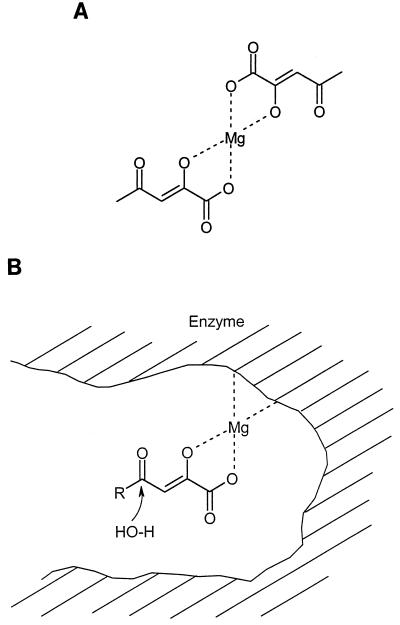

There was, however, a second feature involved, namely, the chelation characteristics of the substrates to various metal ions (5). In particular, Mg2+ is coordinated to the enolate dianion, and a bidentate is formed. What then is the role of Mg2+ in catalysis? We propose that substrate binding to the hydrolase is Mg2+ or Mn2+ dependent and provides an enolate complex with the enzyme for the catalytic reaction (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Proposed coordination structures of Mg2+ and acetopyruvate (5) (A) and potential substrate binding to the enzyme (B).

Mg2+ ions also may form complexes with the 4-phenyl and 4-benzyl 2,4-diketobutanoate analogues as delocalized structures of the type proposed for their protonation (Fig. 4 and 6) (7). Thus, both 2- and 4-keto oxygens do not form complexes with metal ions; in contrast with the 2-enol and carbonyl oxygen atoms of acetopyruvate and stable substrate 2-enol forms. The arene analogues are not available as substrates for catalysis.

General conclusion.

A study of one enzyme of the β-ketolase class of enzymes (EC 3.7.1.1 to EC 3.7.1.10) is insufficient for making broad generalizations, although some significant features do emerge from this work. Attention to, and understanding of the solution structures of these carbonyl substrates is very important for the interpretation of binding and catalytic events. We chose acetopyruvate hydrolase for its apparent simplicity but found quite unexpected complexity of the solution structures of several substrates and their metal chelates. Furthermore, we showed how acetopyruvate readily dimerizes in aqueous solution (5). The effect of the dimer formed (5) on the enzymic hydrolysis of monomeric substrates was not assessed, but it was shown that the dimer was not a substrate.

Of the 1,3-diketo carbon-carbon bond hydrolases, only two (EC 3.7.1.2 and EC 3.7.1.6) have been purified to apparent homogeneity (28). Hydrolases used in catabolic sequences for arenes dioxygenate catechols, quinols, and hydroxyquinols, which use meta-ring cleavage enzymes give vinylogous 1,5-diketones for hydrolysis. Attention has been paid to their subunit structures; monomeric, dimeric, and tetrameric enzymes were isolated from different bacterial sources (2, 4, 12, 24). Substrate specificities of the vinylogous 1,5-diketo hydrolases have been examined almost exclusively with substrates biochemically prepared in solution. The substrate structures in aqueous solution are usually depicted only as keto-enol tautomeric forms. This is consistent with the UV-visible spectra at different pH values, which show characteristic isosbestic points. From our proton and carbon-13 measurements (5) with the simpler 2,4-diketo acids, we suggest that the solution structures of the vinylogous 2,6-diketo acids are much more complex than those proposed; hydrates and their isomeric (E/Z) forms are likely to exist as well. Investigations for the purpose of understanding the molecular species of these substrates that these enzymes hydrolyze are under way.

In other experiments (data not shown), we observed similar results for stoichiometries of the hydrolase reactions with a partially purified enzyme and even with crude cell extracts. While meaningful experiments with crude enzyme preparations seem appropriate here, they are antithetical to the legendary dictum of the late Ephraim Racker (29): “Don’t waste clean ideas on dirty enzymes.” We are totally in agreement with this statement, but if it can be demonstrated, as it can for acetopyruvate hydrolase, that results with a crude enzyme preparation are the same as those with the homogenous enzyme of interest, then “dirty enzymes” are acceptable for preliminary experiments. The selective specificity of C-C bond hydrolysis of 1,3-diketo structures is ensured when the specificity for the regulation of enzyme synthesis is also demonstrated (8–10, 27). Acetopyruvate hydrolase (and many other β-ketolases) in cells is induced by the diketones or their precursors (28).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support from Österreichische Nationalbank, project 6404, and from the Austrian Science Foundation, project P12763-CHE, is gratefully acknowledged.

We also thank J. Plavec and M. Polak (National Institute of Chemistry, Ljubljana, Slovenia) for taking the 600-MHz spectra. M. Hayn (KF-Uni Graz), H. Weber, and H. Böhling (TU Graz) contributed substantially to this work.

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to Robert McLafferty on the occasion of his 70th birthday.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeles R H, Frey P A, Jencks W A. Biochemistry. Boston, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assinder S J, Williams P A. The TOL plasmids: determinants of the catabolism of toluene and the xylenes. Adv Microb Physiol. 1990;31:1–69. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartholomew B A, Smith M J, Long M T, Darcy P J, Trudgill P W, Hopper D A. The isolation and identification of 6-hydroxycyclohepta-1,4-dione as a novel intermediate in the bacterial degradation of atropine. Biochem J. 1993;293:115–118. doi: 10.1042/bj2930115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayly R C, Di Berardino D. Purification and properties of 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-2,4-heptadienoate hydrolase from two strains of Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:30–37. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.1.30-37.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brecker L, Pogorevc M, Griengl H, Steiner W, Kappe T, Ribbons D W. Synthesis of 2,4-diketoacids and their aqueous solution structures. New J Chem. 1998;23:437–446. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brecker, L., P. Urdl, W. Schmidt, H. Griengl, and D. W. Ribbons. 1999. Unpublished data.

- 7.Chamberlain E M, Dagley S. The metabolism of thymol by a Pseudomonas. Biochem J. 1968;110:755–763. doi: 10.1042/bj1100755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman P J, Ribbons D W. Metabolism of resorcinylic compounds by bacteria: orcinol pathway in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1976;125:975–984. doi: 10.1128/jb.125.3.975-984.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman P J, Ribbons D W. Metabolism of resorcinylic compounds by bacteria: alternative pathways for resorcinol in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1976;125:985–998. doi: 10.1128/jb.125.3.985-998.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davey J F, Ribbons D W. Metabolism of resorcinylic compounds by bacteria. Purification and properties of acetylpyruvate hydrolase from Pseudomonas putida 01. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:3826–3830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeFrank J J, Ribbons D W. p-Cymene pathway in Pseudomonas putida: initial reactions. J Bacteriol. 1977;129:1356–1364. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.3.1356-1364.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Díaz E, Timmis K N. Identification of functional residues in a 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde hydrolase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6403–6411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fersht A R. Enzyme structure and mechanism. W. H. New York, N.Y: Freeman; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gadian D G. Nuclear magnetic resonance and its application to living systems. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaines G L, Smith L, Neidle E L. Novel nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy methods demonstrate preferential carbon source utilization by Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6833–6841. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6833-6841.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guéron M, Plateau P, Decorps M. Solvent signal suppression in NMR. Prog NMR Spectrosc. 1991;23:135–209. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guthrie J P. Acetopyruvic acid: rate and equilibrium constants for hydration and enolization. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:7020–7024. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haines J R, Alexander M. Microbial degradation of polyethylene glycols. Appl Microbiol. 1975;29:621–625. doi: 10.1128/am.29.5.621-625.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hickel A, Gradnig G, Griengl H, Schall M, Sterk H. Determinations of the time course and enzymic reaction by 1H-NMR spectrometry: hydroxynitrile-lyase catalysed transhydrocyanation. Spectrochim Acta Part A. 1996;52:93–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hore J P. Solvent suppression. Methods Enzymol. 1989;176:64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsiang H H, Sim S S, Mahuran D J, Schmidt D E. Purification and properties of a diketo acid hydrolase from beef liver. Biochemistry. 1972;11:2098–2102. doi: 10.1021/bi00761a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalinowski H O, Berger S, Braun S. 13C-NMR-Spectroskopie. Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme Verlag; 1984. p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meister A, Greenstein J P. Enzymic hydrolysis of 2,4-diketoacids. J Biol Chem. 1948;175:573–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menn F M, Zylstra G J, Gibson D T. Location and sequence of the todF gene encoding 2-hydroxy-6-oxohepta-2,4-dienoate hydrolase in Pseudomonas putida F1. Gene. 1991;104:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90470-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morawski B, Eaton R W, Rossiter J T, Guoping S, Griengl H, Ribbons D W. 2-Naphthoate catabolic pathway in Burkholderia strain JT 1500. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:115–121. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.115-121.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogg R J, Kingsley P B, Tayler J S. WET, a T1- and B1-insensitive water-suppression method for in vivo localised 1H NMR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson B. 1994;104:1–10. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pogorevc M. Magister Diploma thesis. Graz, Austria: Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pokorny D, Steiner W, Ribbons D W. β-Ketolases—forgotten hydrolytic enzymes? Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:291–296. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Racker E. Remembering Ef: Efraim Racker. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:6. . (Obituary.) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribbons, D. W., and L. Brecker. 1999. Unpublished data.

- 30a.Ribbons D W, Weber H, Griengl H. Abstracts of the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Monitoring microbial fermentations by proton-ID-NMR-spectrometry, abstr. Q-58; p. 465. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakai K, Hamada N, Watanabe Y. A new enzyme, β-diketone hydrolase: a component of a poly(vinyl alcohol)-degrading enzyme preparation. Agric Biol Chem. 1985;49:1901–1902. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salhany J M, Yamane T, Shulman R G, Ogawa S. High resolution 31P nuclear magnetic resonance studies of intact yeast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:4966–4970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.12.4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smallcombe S H, Patt S L, Keifer P A. WET solvent suppression and its applications to LC NMR and high-resolution spectroscopy. J Magn Reson A. 1995;117:295–303. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sprinson D B, Rittenberg D. Nature of the activation process in enzymatic reactions. Nature. 1951;167:484. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuky T, Tsuchii A. Degradation of diketones by a polyvinyl alcohol-degrading enzyme produced by a Pseudomonas sp. Process Biochem. 1983;12:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trudgill P W. Natural puzzles: alicyclic rings and things. In: Hagedorn S C, Hanson R S, Kunz D A, editors. Microbial metabolism and the carbon cycle. Newark, N.J: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1988. p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Webb E C. IUBMB enzyme nomenclature. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weber, H. K., H. Weber, and R. J. Kazlauskas. 1999. Unpublished data.

- 39.Willetts A J. Structural studies and synthetic applications of Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:55–62. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)84204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]