Abstract

Background

Adolescents with immature mind and unstable emotional control are high-risk groups of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) behavior. We meta-analyzed the global prevalence of NSSI and prevalence of NSSI characteristics in a non-clinical sample of adolescents between 2010 and 2021.

Methods

A systematic search for relevant articles published from January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2021 was performed within the scholarly database search engines of CBM, CNKI, VIP, Wanfang, PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and Embase. Eligibility criteria were as follows: provided cross-sectional data on the prevalence of NSSI; the subjects were non-clinical sample adolescents; and a clear definition of NSSI was reported. We used the following definiton of NSSI as our standard: the deliberate, self-inflicted destruction of body tissue, such as cutting, burning, and biting, without attempted suicide. The quality evaluation tool for cross-sectional studies recommended by the JBI was used. The global prevalence of NSSI was calculated based on the random-effects model by Comprehensive Meta-analysis version 3.0. Subgroup analyses were performed to compare the prevalence according to sex, living place, smoking or drinking history, and family structure.

Results

Sixty-two studies involving 264,638 adolescents were included. The aggregate prevalence of NSSI among a non-clinical sample of adolescents was similar between over a lifetime (22.0%, 95% CI 17.9–26.6) and during a 12-month period (23.2%, 95% CI 20.2–26.5). Repetitive NSSI was more common than episodic NSSI (20.3% vs. 8.3%) but the frequency of mild injury (12.6%) was similar to that of moderate injury (11.6%). Multiple-method NSSI occurred slightly more often compared than one-method NSSI (16.0% vs. 11.1%). The top three types of NSSI in adolescents were banging/hitting (12.0%, 95% CI 8.9–15.9), pinching (10.0%, 95% CI 6.7–14.8), and pulling hair (9.8%, 95% CI 8.3–11.5), and the least common type was swallowing drugs/toxic substances/chemicals (1.0%, 95% CI 0.5–2.2). Subgroup analyses showed that being female, smoking, drinking, having siblings, and belonging to a single-parent family may be linked to higher prevalence of NSSI.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis found a high prevalence of NSSI in non-clinical sample of adolescents, but there are some changes in severity, methods, and reasons. Based on the current evidence, adolescents in modern society are more inclined to implement NSSI behavior by a variety of ways, which usually are repetitive, and moderate and severe injuries are gradually increasing. It is also worth noting that adolescents with siblings or in single-parent families are relatively more likely to implement NSSI behavior due to maladjustment to the new family model. Future research needs to continue to elucidate the features and risk factors of NSSI so as to intervene in a targeted way.

Limitation

The limitation of this study is that the heterogeneity among the included studies is not low, and it is mainly related to Chinese and English studies. The results of this study should be used with caution.

Systematic review registration

[www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/], identifier [CRD42022283217].

Keywords: adolescents, non-suicidal self-injury, prevalence, characteristics, meta-analysis

Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) behavior in adolescents is an ongoing societal health concern and is defined as the deliberate, direct, and socially unacceptable destruction of body tissue, such as skin cutting, skin burning, and hitting oneself, but without an attempt at suicide (1, 2). The possible motivation and potential purpose of NSSI behavior in adolescents might be to remove difficulties in life, release pressure or control emotion (3). NSSI behavior often carries a high risk of personal injury and high risk of repetition, which can increase the occurrence of suicidal behavior and seriously endanger the physical and mental health of adolescents (4, 5). Many lines of evidence indicate that while adolescents are physically mature during puberty, they have yet to reach psychological maturity, have higher levels of impulsivity, and may experience difficulty in regulation of negative emotions and be prone to engage in NSSI behaviors (6). Moreover, NSSI during adolescence can have long-lasting and far-reaching developmental consequences, manifesting as anxiety, depression, and suicidal behaviors later in life as well as increased burden on society and families (7). The prevalence of NSSI in adolescents increased significantly at the beginning of the 21st century, and the incidence remains high (8).

In China, a total of 15,623 adolescents in rural regions were engaged in a nationwide survey by using a multistage sampling method, and approximately 29% of them reported a history of NSSI at least once during the last year (9). In the United States, a 2015 survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System estimated the prevalence of NSSI behavior among high-school-age adolescents (n = 64671) in 11 US states. It concluded that 6.4–30.8% of adolescents had purposefully engaged in NSSI behavior without attempted suicide during the past 12 months (10). A cross-sectional assessment comprising 12,068 adolescents in 11 European countries determined the lifetime prevalence of direct self-injurious behavior (D-SIB) to be 27.6%, corresponding to 19.7% for occasional D-SIB and 7.8% for repetitive D-SIB. Lifetime prevalence varied from 17.1 to 38.6% across countries (11). According to a meta-analysis, the average lifetime prevalence of primary occurrence of NSSI in school-aged adolescents worldwide was 17.2% (range 8.0–26.3%) (12). Another meta-analysis involving 686,672 children and adolescents found a 22.1% (95% CI 16.9–28.4) lifetime prevalence of NSSI and 19.5% (95% CI 13.3–27.6) in a 12-month time period (13). It is not difficult to see that NSSI has become one of the key health problems in the field of adolescent psychology in the past decade. However, the epidemic characteristics and influencing factors of NSSI in different regions of the world are quite different.

Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to estimate the global prevalence of NSSI behavior and research its characteristics in adolescents. In this context, we were able to identify epidemiological and social factors associated with NSSI that could be used to deliver timely assistance and intervention in the future.

Methods

This study was conducted by following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (14), with the registration number of CRD42022283217 on PROSPERO.

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

A systematic search within the literature was performed using the electronic databases China Biological Medicine (CBM), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP database, Wanfang database, PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and Embase, from January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2021. In this study, we use the combination of Mesh words and free words for literature search. The following search terms or combination thereof were used (* indicates truncation): (“self-harm” or “self-injury”) and (“adolescent” or “youth” or “young” or “teen*” or “student*” or “school*”) and (“prevalence”). Reference lists from the retrieved literature were also examined to identify additional studies.

Two authors (X-zS and L-jH) independently confirmed the eligibility of studies by screening title and abstract. Studies published in English or Chinese were considered. Any dissonance between the two authors was communicated and jointly resolved. Eligibility criteria are as follows: provided cross-sectional data on the prevalence of NSSI; the subjects are non-clinical sample adolescents who are those between the ages of 10 and 19; and a clear definition of NSSI was reported. We used the following definiton of NSSI as our standard: the deliberate, self-inflicted destruction of body tissue, such as cutting, burning, and biting, without attempted suicide (1, 2). Any study that did not meet the above inclusion criteria was excluded.

Data extraction

Two authors (L-jH and D-dH) independently and manually extracted data from eligible studies after reading the full-length text. The following data were extracted: name of first author, year of publication, country of origin, study design, instrument for NSSI assessment, participant gender, total sample size, mean age of participants, and prevalence of NSSI. Prevalence of NSSI was considered our primary outcome. Disagreements about data extraction were resolved by the corresponding author (X-hH). We used the quality evaluation tool for cross-sectional studies recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (15).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with Comprehensive Meta-analysis version 3.0. The I2 statistic was used to assess the between-study heterogeneity, which described the percentage of variance on a basis of real differences in study effects. An I2 value of 25% was considered low, 50% moderate and 75% substantial. If significant heterogeneity was detected, the random-effects model was applied. The random-effects model assumes various effect sizes between studies, different study designs and study subjects. Thus, the aggregate prevalence of NSSI was calculated based on the random-effects model, and data were reported with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) where appropriate. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Publication bias was assessed using the funnel plot along with Egger’s and Begg’s tests. A p value of 0.05 or less was used as the cut off for the presence of statistically significant publication bias. Subgroup analyses were performed to compare the aggregate prevalence of NSSI outcome in each study as a function of sex, living place, smoking, or drinking history, and family structure. Sensitivity analyses were performed by changing the combined effect model to explore potential sources of heterogeneity.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

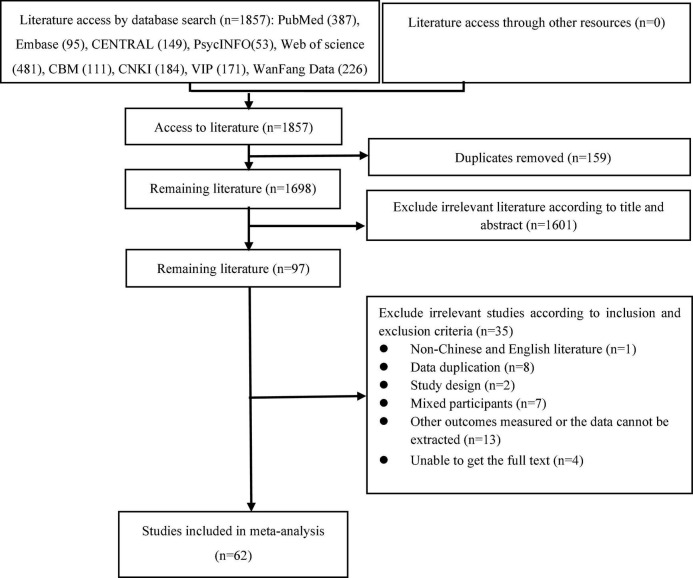

The detailed process of paper selection is displayed in Figure 1. A total of 1,857 relevant citations were gathered after an extensive literature search was performed in several databases. Duplicates (n = 159) were removed, and a screen of titles and abstracts determined that an additional 1,601 were irrelevant. The resulting 97 studies were comprehensively reviewed, and an additional 35 were excluded. Finally, 62 studies including 264,638 subjects were used in this meta-analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of literature search.

Characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Country of origin | Instrument for NSSI assessment | Sample size |

Mean age | Prevalence of NSSI, % |

|||

| Male | Female | Total | Past year | Lifetime | ||||

| Yan et al., 2012 (16) | China | RBQ-A | 705 | 583 | 1288 | 14.24 | 22.67 | NA |

| Giletta et al., 2012 (17) | Italy; Netherlands | 6-item measure | NA | NA | 1502 | 15.69 | 22.84 | NA |

| Di Pierro et al., 2012 (18) | Italy | SIQ-TR | 79 | 188 | 267 | 17.03 | 13.48 | 18.4 |

| Sornberger et al., 2012 (19) | United States | Single-item measure | 3503 | 3623 | 7126 | 14.92 | NA | 24.47 |

| Tang et al., 2013 (20) | China | FASM | 1436 | 1471 | 2907 | 15.4 | 33.6 | NA |

| Tormoen et al., 2013 (21) | United States | Single-item measure | NA | NA | 11440 | NA | NA | 4.3 |

| Cheung et al., 2013 (22) | China | Single-item measure | 1047 | 1270 | 2317 | 16.4 | 13.98 | NA |

| Zetterqvist et al., 2013 (23) | Sweden | FASM | 1515 | 1545 | 3060 | NA | 35.6 | 41.6 |

| Liang et al., 2014 (24) | China | 8-item measure | 1089 | 1031 | 2140 | 14 | NA | 23.1 |

| Rodav et al., 2014 (25) | Israel | OSI-F | NA | NA | 275 | 14.81 | 20.7 | NA |

| Liang et al., 2014 (26) | China | SHQ | 1085 | 1046 | 2131 | 13.92 | NA | 23.2 |

| Evren et al., 2014 (27) | Turkey | Single-item measure | NA | NA | 4957 | 15.58 | 14.4 | NA |

| Albores-Gallo et al., 2014 (28) | Mexico | Self-injury questionnaire | 244 | 289 | 533 | 13.37 | 12.6 | 17.1 |

| Claes et al., 2014 (29) | Belgium | SHI | 395 | 137 | 532 | 15.11 | NA | 26.5 |

| Claes et al., 2015 (30) | Belgium; Netherlands | SHI | 436 | 349 | 785 | 15.56 | NA | 20.1 |

| Hanania et al., 2015 (31) | Jordan | Single-item measure | 478 | 474 | 952 | NA | 14.29 | 22.6 |

| Kiekens, 2015 (32) | Belgium; Netherlands | SHI | 511 | 408 | 946 | 15.52 | NA | 24.31 |

| Gandhi et al., 2015 (33) | Belgium | SIQTR | 201 | 335 | 568 | 16.13 | NA | 16.5 |

| Calvete et al., 2015 (34) | Spain | FASM | 901 | 959 | 1864 | 15.32 | 32.2 | NA |

| Somer et al., 2015 (35) | Turkey | ISAS | 745 | 911 | 1656 | 16.8 | NA | 31.3 |

| Kim and Yu, 2017 (36) | South Korea | DSHI | 376 | 341 | 717 | NA | NA | 8.8 |

| Cimen et al., 2017 (37) | Turkey | ISAS | 241 | 314 | 555 | NA | NA | 11.4 |

| Liu et al., 2017 (38) | China | Single-item measure | 1027 | 1063 | 2090 | 15.5 | 12.6 | 8.8 |

| Lin et al., 2017 (39) | China | Twelve NSSI behaviors | 1007 | 1108 | 2161 | 15.83 | 20.1 | NA |

| Ma et al., 2018 (40) | China | Adolescent NSSI behavior questionnaire | 4600 | 5104 | 9704 | NA | 38.50 | NA |

| Jiang et al., 2018 (41) | China | Chinese version of YRBSS | 1005 | 805 | 1910 | NA | 6.80 | NA |

| Cui et al., 2018 (42) | China | Single-item measure | 2033 | 1704 | 3737 | NA | 34.7 | NA |

| Gandhi et al., 2018 (43) | Belgium | Single-item measure | NA | NA | 401 | 16.6 | NA | 16.5 |

| Liu et al., 2018 (44) | China | Single-item measure | NA | NA | 5696 | 15.0 | 21.4 | 28.1 |

| Tang et al., 2018 (9) | China | Chinese-FASM | 8043 | 7580 | 15623 | 15.2 | 29.2 | NA |

| Ren et al., 2018 (45) | China | DSHI | 955 | 1034 | 1989 | 15.45 | 20.8 | NA |

| Jiang et al., 2018 (46) | China | DSHI | 579 | 447 | 1026 | 13.76 | 24.2 | NA |

| Cao et al., 2019 (47) | China | Single-item measure | 1075 | 1029 | 2104 | NA | NA | 10.9 |

| Chen et al., 2019 (48) | China | OSI | 4150 | 2979 | 7129 | 15.48 | NA | 33.7 |

| Chen et al., 2019 (49) | China | 8-item measure | 7250 | 6192 | 14162 | 15.13 | 15.36 | NA |

| Ma et al., 2019 (50) | China | 8-item measure | 7999 | 7539 | 15538 | 15.13 | 28.74 | NA |

| Xu et al., 2019 (51) | China | ANSAQ | 10862 | 10969 | 21831 | 15 | 7.9 | NA |

| Zhang and Zhang, 2019 (52) | China | Adolescents’ non-suicidal self-injury scale | 708 | 789 | 1497 | 12.01 | NA | 9.9 |

| Li et al., 2019 (53) | China | 8-item measure | 10990 | 11638 | 22628 | 15.36 | 32.1 | NA |

| Gaspar et al., 2019 (54) | Portugal | Single-item measure | 1499 | 1763 | 3262 | 14.8 | 20.3 | NA |

| Hu et al., 2020 (55) | China | OSI | 4150 | 2979 | 7129 | 15.48 | 33.7 | NA |

| Hu et al., 2020 (56) | China | ANSAQ | 3995 | 3130 | 7125 | 13.93 | 51.40 | NA |

| Jiang et al., 2020 (57) | China | ANSAQ | 7347 | 7153 | 14500 | 14.83 | 14.81 | NA |

| Lin et al., 2020 (58) | China | Modified Adolescents’ Self-Harm Scale | 997 | 1068 | 2065 | NA | NA | 40.34 |

| Mao et al., 2020 (59) | China | Modified Adolescents’ Self-Harm Scale | 308 | 333 | 641 | 16.37 | NA | 32.1 |

| Pang and Wang, 2020 (60) | China | Self injury behavior assessment questionnaire | 7648 | 7174 | 14822 | 15.27 | 30.54 | NA |

| Wang et al., 2020 (61) | China | Fourteen NSSI behaviors | 412 | 363 | 775 | 15.58 | 41.3 | NA |

| Zhou et al., 2020 (62) | China | OSI | 2219 | 2215 | 4434 | 14.38 | 33.3 | NA |

| Liu et al., 2020 (63) | China | Adolescent NSSI Function Assessment Scale | 1245 | 1460 | 2705 | 13.4 | NA | 47.1 |

| Tang et al., 2020 (64) | China | Chinese-FASM | 8043 | 7580 | 15623 | 15.1 | 28.58 | NA |

| Gu et al., 2020 (65) | China | Seven NSSI behaviors | NA | NA | 949 | 13.35 | 38.9 | NA |

| Buelens et al., 2020 (66) | Belgium | Single-item measure | NA | NA | 2130 | 15 | NA | 21.8 |

| Liang et al., 2021 (67) | China | DSHI | 670 | 611 | 1281 | 10.60 | NA | 42.31 |

| Sun et al., 2021 (68) | China | RBQ-A | 534 | 466 | 1000 | NA | NA | 27.6 |

| Costa et al., 2021 (69) | Brazil | FASM | 254 | 251 | 505 | 14.32 | 45.3 | NA |

| Perez et al., 2021 (70) | Spain | ISAS | 809 | 924 | 1733 | 15.76 | NA | 24.6 |

| Madjar et al., 2021 (71) | Israel | NSSI-AT | 148 | 158 | 306 | NA | 11.4 | NA |

| Jeong and Kim, 2021 (72) | South Korea | Single-item measure | 968 | 879 | 1843 | NA | 8.8 | NA |

| Lee et al., 2021 (73) | South Korea | Korean-DSHI | 1075 | 599 | 1674 | 16.6 | 28.3 | NA |

| Tang et al., 2021 (74) | China | Twelve NSSI behaviors | 545 | 504 | 1060 | 14.66 | 40.9 | NA |

| Jiang et al., 2021 (75) | China | Seven NSSI behaviors | 356 | 372 | 728 | 14.07 | 17.4 | NA |

| Abbasian et al., 2021 (76) | Iran | ISAS | NA | NA | 604 | 14.29 | NA | 38.7 |

SHQ, self-harm questionnaire; RBQ-A, risky behavior questionnaire for adolescents; YRBSS, youth risk behavior surveillance system; OSI, Ottawa self-injury; ANSAQ, adolescent non-suicidal self-injury assessment questionnaire; DSHI, deliberate self-harm inventory; SIQTR, self-injury questionnaire-treatment related; FASM, functional assessment of self-mutilation; OSI-F, Ottawa self-injury inventory-functions; SHI, self-harm inventory; ISAS, inventory of statements about self-injury; NSSI-AT, non-suicidal self-injury assessment tool; NA, not available.

Quality assessment of included studies

Most of the included studies (44, 71%) were of high quality, complied with all items of the quality evaluation tool for cross-sectional studies recommended by the JBI, but a few included studies (18, 29%) did not clearly give the content required for evaluation (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Quality assessment of included studies.

| Study | Q1a | Q2a | Q3a | Q4a | Q5a | Q6a | Q7a | Q8a | Q9a |

| Yan et al., 2012 (16) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Giletta et al., 2012 (17) | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Di Pierro et al., 2012 (18) | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Sornberger et al., 2012 (19) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tang et al., 2013 (20) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tormoen et al., 2013 (21) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cheung et al., 2013 (22) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zetterqvist et al., 2013 (23) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Liang et al., 2014 (24) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rodav et al., 2014 (25) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Liang et al., 2014 (26) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Evren et al., 2014 (27) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Albores-Gallo et al., 2014 (28) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Claes et al., 2014 (29) | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Claes et al., 2015 (30) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hanania et al., 2015 (31) | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kiekens et al., 2015 (32) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gandhi et al., 2015 (33) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Calvete et al., 2015 (34) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Somer et al., 2015 (35) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kim and Yu, 2017 (36) | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cimen et al., 2017 (37) | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Liu et al., 2017 (38) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lin et al., 2017 (39) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ma et al., 2018 (40) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jiang et al., 2018 (41) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cui et al., 2018 (42) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gandhi et al., 2018 (43) | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Liu et al., 2018 (44) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tang et al., 2018 (9) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ren et al., 2018 (45) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jiang et al., 2018 (46) | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cao et al., 2019 (47) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chen et al., 2019 (48) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chen et al., 2019 (49) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ma et al., 2019 (50) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Xu et al., 2019 (51) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zhang and Zhang, 2019 (52) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Li et al., 2019 (53) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gaspar et al., 2019 (54) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hu et al., 2020 (55) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hu et al., 2020 (56) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jiang et al., 2020 (57) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lin et al., 2020 (58) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mao et al., 2020 (59) | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pang and Wang, 2020 (60) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wang et al., 2020 (61) | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zhou et al., 2020 (62) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Liu et al., 2020 (63) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tang et al., 2020 (64) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gu et al., 2020 (65) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Buelens et al., 2020 (66) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Liang et al., 2021 (67) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sun et al., 2021 (68) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Costa et al., 2021 (69) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Perez et al., 2021 (70) | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Madjar et al., 2021 (71) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jeong and Kim, 2021 (72) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lee et al., 2021 (73) | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tang et al., 2021 (74) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jiang et al., 2021 (75) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Abbasian, 2021 (76) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

aQ1–Q9 based on the Joanna Briggs Institute Risk Assessment (15).

Aggregate prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents

Lifetime and 12-month prevalence

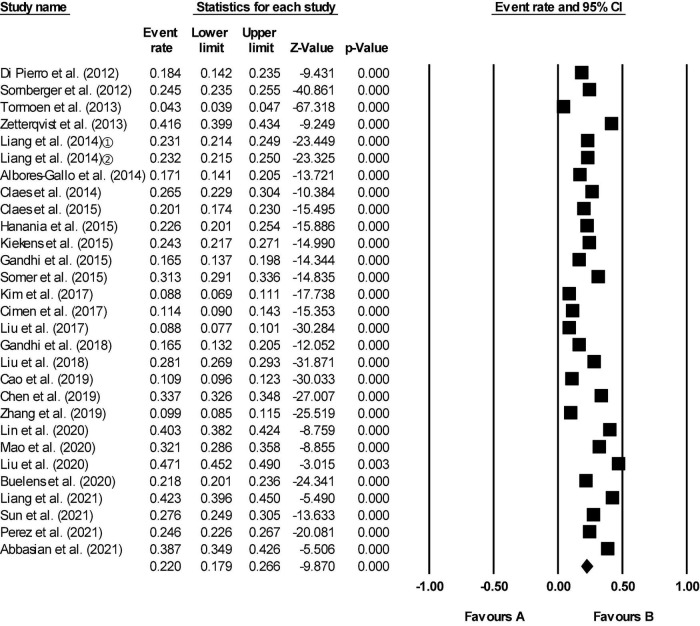

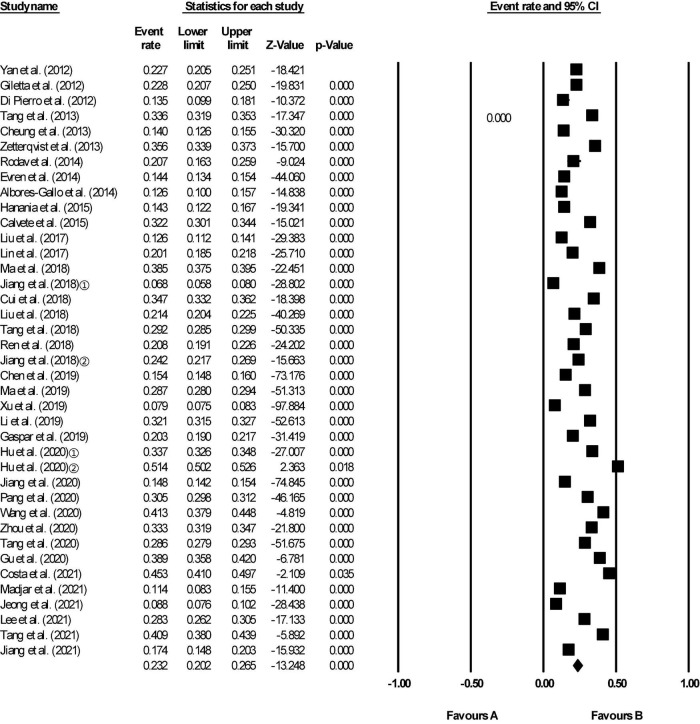

Of the 62 included studies, some reported lifetime prevalence, some reported 12-month prevalence, and some both. In our study the lifetime aggregate prevalence of NSSI among 64,484 adolescents included in 29 studies was 22.0% (95% CI 17.9–26.6) (Figure 2). There was a significant level of heterogeneity detected (I2 = 99.393, p < 0.001). The 12-month aggregate prevalence of NSSI was only slightly higher when assessed in 39 studies (23.2%, 95% CI 20.2–26.5) involving a total of 212,752 adolescents (Figure 3). The heterogeneity remained significantly high with the additional studies (I2 = 99.660, p < 0.001).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of the lifetime aggregate prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents. The location of the square represents the incidence of the event, the size of the square represents the weight, and the diamond represents the combined incidence.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of the 12-month aggregate prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents.

Aggregate prevalence of different characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents

Frequency

Table 3 shows that the aggregate prevalence of episodic NSSI in adolescents was 8.3% (95% CI: 5.4–12.5), while 20.3% (95% CI 13.9–28.6) of adolescents reported repetitive NSSI.

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents.

| Characteristic | Number of studies (n) | NSSI prevalence (%) | 95% CI | Heterogeneity test |

|

| I2/% | p | ||||

| Frequency | |||||

| Episodic frequency | 6 | 8.3 | 5.4–12.5 | 98.606 | <0.001 |

| Repetitive frequency | 6 | 20.3 | 13.9–28.6 | 99.295 | <0.001 |

| Severity | |||||

| Minor/mild | 5 | 12.6 | 6.4–23.3 | 99.432 | <0.001 |

| Moderate/severe | 5 | 11.6 | 10.0–13.3 | 84.917 | <0.001 |

| Method | |||||

| One method | 6 | 11.1 | 8.8–13.9 | 88.157 | <0.001 |

| Multiple methods | 6 | 16.0 | 11.0–22.6 | 97.003 | <0.001 |

| Type | |||||

| Cutting | 19 | 7.0 | 5.7–8.6 | 97.996 | <0.001 |

| Biting | 12 | 8.6 | 6.4–11.4 | 98.957 | <0.001 |

| Burning | 17 | 2.5 | 1.8–3.4 | 97.394 | <0.001 |

| Carving | 7 | 7.8 | 5.1–12.0 | 97.608 | <0.001 |

| Pinching | 4 | 10.0 | 6.7–14.8 | 96.367 | <0.001 |

| Pulling hair | 10 | 9.8 | 8.3–11.5 | 97.429 | <0.001 |

| Scratching | 13 | 8.6 | 6.6–10.9 | 97.755 | <0.001 |

| Banging/hitting | 18 | 12.0 | 8.9–15.9 | 99.566 | <0.001 |

| Interfering with wounds | 5 | 7.8 | 4.8–12.3 | 96.291 | <0.001 |

| Rubbing skin | 3 | 3.6 | 2.0–6.6 | 96.620 | <0.001 |

| Sticking needles | 3 | 3.6 | 1.8–7.0 | 96.664 | <0.001 |

| Swallowing drug/toxic substance/chemicals | 3 | 1.0 | 0.5–2.2 | 93.874 | <0.001 |

Severities

The aggregate prevalence of minor or mild NSSI in adolescents was 12.6% (95% CI 6.4–23.3), which was similar to that of moderate or severe NSSI (11.6%, 95% CI 10.0–13.3) (Table 3).

Method

One-method NSSI affected 11.1% (95% CI 8.8–13.9) of the adolescent population included in our meta-analysis (Table 3), with a slightly higher percentage reporting multiple-method NSSI (16.0%, 95% CI 11.0–22.6).

Type

The top three types of NSSI in adolescents were banging/hitting (12.0%, 95% CI 8.9–15.9), pinching (10.0%, 95% CI 6.7–14.8), and pulling hair (9.8%, 95% CI 8.3–11.5), and the least used type of self-harm was swallowing drugs/toxic substances/chemicals (1.0%, 95% CI 0.5–2.2) (Table 3).

Subgroup analyses of non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents

Sex

When classified by gender, the prevalence of NSSI was significantly higher in females (25.4%, 95% CI 22.4–28.6) than in males (22.0%, 95% CI 19.2–25.0; p < 0.001) based on 43 studies (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents based on subgroup analyses.

| Subgroup | Number of studies, n | Number of adolescents, n | NSSI prevalence, % | 95% CI, % | Heterogeneity test |

Subgroup differences |

||||

| I2/% | p | OR | 95% CI | Z | p | |||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 43 | 107,285 | 22.0 | 19.2–25.0 | 99.268 | <0.001 | 0.839 | 0.768–0.918 | –3.835 | <0.001 |

| Female | 43 | 102,473 | 25.4 | 22.4–28.6 | 99.202 | <0.001 | ||||

| Living place | ||||||||||

| Urban areas | 10 | 37,514 | 26.6 | 20.6–33.5 | 99.428 | <0.001 | 1.048 | 0.923–1.190 | 0.727 | 0.467 |

| Rural areas | 10 | 28,404 | 25.8 | 20.9–31.4 | 98.930 | <0.001 | ||||

| Smoking history | ||||||||||

| Yes | 3 | 1,479 | 24.7 | 12.4–43.1 | 93.050 | <0.001 | 2.588 | 1.470–4.559 | 3.293 | <0.001 |

| No | 3 | 4,072 | 10.1 | 3.2–27.6 | 99.149 | <0.001 | ||||

| Drinking history | ||||||||||

| Yes | 3 | 2,721 | 24.4 | 12.2–42.9 | 96.610 | <0.001 | 3.014 | 1.487–6.108 | 3.060 | 0.002 |

| No | 3 | 2,850 | 9.3 | 3.1–24.8 | 98.677 | <0.001 | ||||

| One child | ||||||||||

| Yes | 16 | 49,014 | 25.8 | 22.5–29.3 | 98.611 | <0.001 | 0.939 | 0.889–0.991 | –2.269 | 0.023 |

| No | 16 | 86,402 | 27.0 | 24.0–30.3 | 99.077 | <0.001 | ||||

| Single-parent family | ||||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 1,203 | 30.1 | 27.6–32.8 | 1.758 | 0.383 | 1.200 | 1.056–1.363 | 2.379 | 0.017 |

| No | 4 | 19,959 | 23.5 | 19.0–28.5 | 97.183 | <0.001 | ||||

Urban vs. rural

When the subjects in 10 studies were grouped by location, the prevalence of NSSI was found to be higher among adolescents living in urban areas (26.6%, 95% CI 20.6–33.5) than among those living in rural areas (25.8%, 95% CI 20.9–31.4), but this difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Smoking or drinking history

Prevalence of NSSI was significantly higher in adolescents who smoked (24.7%, 95% CI 12.4–43.1 vs. non-smoking: 10.1%, 95% CI 3.2–27.6, p < 0.01) and drank alcohol (24.4%, 95% CI 12.2–42.9 vs. non-drinking: 9.3%, 95% CI 3.1–24.8, p < 0.01). The results from three studies are shown in Table 4.

Family structure

Finally, NSSI was more prominent among adolescents in families with multiple children (27.0%, 95% CI 24.0–30.3) than among those in single-child families (25.8%, 95% CI 22.5–29.3). Moreover, the prevalence of NSSI was higher among adolescents in single-parent families (30.1%, 95% CI 27.6–32.8) than among those in two-parent families (23.5%, 95% CI 19.0–28.5). Differences were statistically significant in both scenarios (p < 0.05).

Sensitivity analysis

In order to explore the stability of meta-analysis results, we repeated the meta-analysis with a fixed-effects model, which gave similar lifetime and 12-month aggregate prevalences of NSSI as the random-effects model. This suggested that our meta-analysis was reliable.

Publication bias

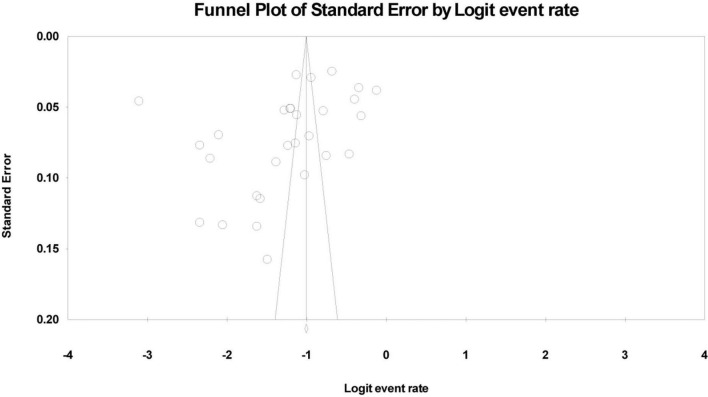

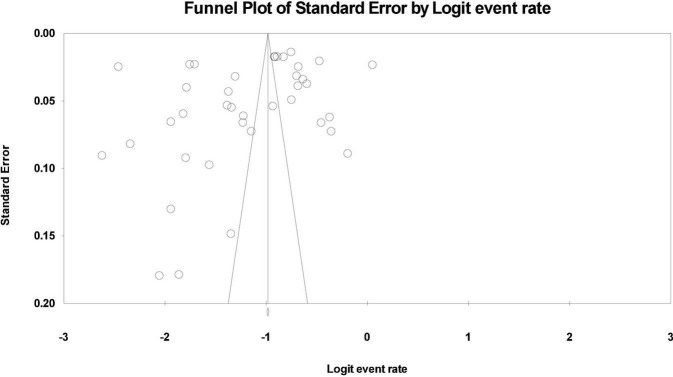

Asymmetry was detected in the funnel plot of the lifetime and 12-month aggregate prevalence rates (Figures 4, 5). Egger’s test showed no significant publication bias in the 29 studies (t = 1.97, p = 0.059) used to determine the lifetime rates, or in the 39 studies used to calculate the 12-month prevalence. However, the Begg’s test found significant publication bias within the studies used to calculate the lifetime aggregate prevalence (Z = 2.10, p = 0.035), but not in those studies referenced for the 12-month aggregate prevalence (Z = 1.68, p = 0.09).

FIGURE 4.

Funnel plot of the lifetime aggregate prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents.

FIGURE 5.

Funnel plot of the 12-month aggregate prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents.

Discussion

Although NSSI in adolescents widespread, it is yet often a hidden problem. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to study the global prevalence and characteristics of NSSI between 2010 and 2021 among a non-clinical sample of adolescents. This meta-analysis found a high prevalence of NSSI in adolescents. Repetitive NSSI was more common than episodic NSSI (20.3% vs. 8.3%) but the frequency of mild injury (12.6%) was similar to that of moderate injury (11.6%). Multiple-method NSSI occurred slightly more often compared than one-method NSSI (16.0% vs. 11.1%). The top three types of NSSI in adolescents were bang-ing/hitting, pinching, and pulling hair, and the least common type was swallowing drugs/toxic substances/chemicals. Subgroup analyses showed that being female, smoking, drinking, having siblings, and belonging to a single-parent family may be linked to higher prevalence of NSSI.

This study found that the aggregate prevalence rates were 22.0% during a lifetime and 23.2% during 12 months. This finding was consistent with the 22.1% lifetime prevalence of NSSI and 19.5% in a 12-month prevalence reported from a meta-analysis with 686,672 children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018 (13). Compared with that study, our study did not include children and focused on the prevalence of NSSI among adolescents in the last decade. It can be seen that the 12-month prevalence rate of NSSI was more higher in our study. However, it was lower than a comparative study done in 11 European countries among 12,068 adolescents showing lifetime prevalence varied from 17.1 to 38.6% (11). Still, our finding was higher than that another meta-analysis reported lifetime prevalence rate of NSSI in a worldwide was 17.2% (12). Despite these slight variations in findings, there is no doubt that the prevalence of NSSI is high worldwide. Adolescence is a sensitive and vulnerable period of time in which a person learns methods of internalizing and externalizing emotions, and a wide range of problematic behaviors can develop as a result of learning unhealthy coping mechanisms (77). Adolescents who have trouble expressing emotions and feelings may project a depressed mood characterized by impulsive and irritable self-injury and self-mutilation. Epidemiological investigation suggests that senior high school students with NSSI behavior often have seriously negative emotions and lack positive cognitive activities (78). When adolescents are in a stressful environment for a long time, or suddenly encounter a stressful event that exceeds their ability to cope, they may be attacked by negative emotions in the face of difficult situations that can not be easily solved, this in turn may induce impulsive and reckless behaviors. Sometimes, adolescents do express their feelings, parents often take a critical or neglectful attitude, which is more likely to lead to the child toward NSSI behavior (79). Other factors may also increase the likelihood of NSSI. For example, peer pressure may lead teenagers to self-mutilate in order to obtain a sense of identity and achievement. These same actions may also lead a teenager to feel embarrassment or inferiority to people around them. Oftentimes an adolescent may hide self-injury behavior and scars in order to avoid recalling the painful experience of the past (80). Schools should be made aware of the extent to which NSSI behavior is prevalent and problematic. This knowledge could guide the creation of safe environments where adolescents can go and learn how to deal with their emotions in positive ways, which could help prevent NSSI.

Our study found that adolescents were much more likely to injure themselves repeatedly by multiple methods, although the likelihood of mild or moderate injury seemed similar. This may reflect that self-injurious behavior can lead someone to feel that he or she is solving interpersonal problems, which may reduce negative thoughts or feelings, and instead generate positive emotions or feelings. To some extent, the more times an adolescent repeats the self-harm, the more they feel that they can control negative emotions. When these actions do not solve the actual problem, the risk of more severe consequences, such as suicide, are increased (81). The present study also found that the three most common types of NSSI in adolescents were banging/hitting, pinching, and pulling hair, while the least common type of NSSI in adolescents was swallowing drugs/toxic substances/chemicals. It is possible that adolescents rarely opt to swallow drugs/toxic substances/chemicals because of their preference for sensory stimulation: more physically involved attempts at self-harm may stimulate the senses more quickly and speed up the reactionary feeling of control. Although another study in 516 Korean adolescents found the incidence of cutting injury was high (19.3%) (82), the prevalence was only 7.0% in our meta-analysis. This may be related to the difficulty in acquiring dangerous goods in some countries, such as blades and sharp tools, or cutting injury was scary and bloody for most adolescents. Our results help to identify common types of self-injury and prevent possible self-injury.

Given that adolescence is a critical period to initiate self-injury prevention and intervention efforts (83), understanding the prevalence and features of NSSI is of great significance. Subgroup analyses showed that being female, smoking, drinking, having siblings, and being part of a single-parent family may increase risk of NSSI. According to our results, the prevalence of NSSI in female adolescents was higher than that in male adolescents. This was consistent with the research results in a study that NSSI showed to be associated with female gender (84). Female adolescents may be more susceptible to self-injury because they are more likely to experience higher negative influence and have lower ability to manage emotion, including acceptance of emotions and controlling impulses (78). Another study confirmed that menophania, irregular menstruation, and algomenorrhea were associated with an increased risk of NSSI (44). Smoking and drinking have also been positively associated with the prevalence of NSSI. Positive relationships of smoking, drinking, and self-injury with NSSI have also been reported in some previous studies (85–87). In addition, family structure and family ties may increase risk of NSSI. Our finding that adolescents from single-parent families were more prone to engage in self-injurious behavior was consistent with a study of Poland encompassed 5,685 individuals (88). It is possible that a connected family and solid parent-child ties can protect against self-injury (26). Research on the influence of familial ties on adolescent NSSI has thus far focused on the influence of parent-child relationships, while remarkably little is known about the influence of the relationships between relatives or between siblings. Our study found that adolescents with siblings were more likely to engage in self-injurious behavior than adolescents in single-child families. The bond between siblings is lifelong and represents one of the most important relationships in one’s life because children spend more time with their siblings than with their parents (89). The bond between siblings encompasses positive features (e.g., warmth, intimacy, empathy) but also negative features (e.g., conflict, rivalry), and it may have a major impact on each sibling’s life and wellbeing (90). Siblings may be a source of emotional support for each other (91). Our findings indicate that adolescents with siblings may face different peer interaction pressure, and may choose NSSI behavior as a signal to seek outside help in order to seek parental attention.

From the results of this study, we could see that in the 21st century, especially in the last decade, the incidence of adolescent NSSI behavior in non-clinical samples remains high, but there are some changes in severity, methods and reasons. Based on the current evidence, adolescents in modern society are more inclined to implement NSSI behavior by a variety of ways, which are repetitive and intentional, and moderate and severe injuries are gradually increasing. In terms of the types of NSSI, in the past, cutting was one of the main ways of self-injury, but the first three types of NSSI in this study were banging/hitting, pinching, and pulling hair. It is also worth noting that adolescents with siblings or single parent families are more prone to NSSI behavior. There may be three reasons as follows:

First, the temptation of virtual world and the influence of network environment on NSSI behavior. With the development of social economy and the popularity of new media on the internet, more and more adolescents are exposed to more complex and varied information about NSSI behavior on the internet. They will compare and discuss their own self-injury experience, and it is easier to try new ways of NSSI behavior (92).

Second, the increase of learning pressure, ineffective coping styles and out-of-control emotional self-management. Compared with the adolescents of the last century, the adolescents of the 21st century live in a more prosperous material environment. But facing a more intense competitive environment, they usually need not only learn the cultural knowledge of an age group, but also learn all kinds of talents or skills (93). When learning pressure is too high and the response is ineffective, their emotions are easy to get out of control, and they may have NSSI behaviors due to venting or avoiding bad emotions.

Third, adolescents’ interpersonal relationships are becoming more and more complex. Adolescents are gradually facing relatively complex peer relationships, teacher-student relationships, and family relationships. The instability of interpersonal relationship is easy to lead to cognitive deviation, negative emotions and problematic behaviors (92). Especially in China, with the opening of the comprehensive two-child policy, adolescents who used to be only children have a brother or sister with a large age difference, and the focus of the family has shifted away from themselves. When they feel helpless and have no help, NSSI behavior may become the last way to deal with it, because the visual impact of self-injury and the signal to the outside world are telling others that “I need help,” at the same time, it can also force others to respond, such as attracting the attention of parents (90). In addition, with the increasingly inclusive society, the increase of personal freedom and the improvement of marital autonomy, the divorce rate in contemporary society is much higher than that in the last century (94). Therefore, the number of children in single parent families is gradually increasing. With the change of family structure, family atmosphere and parental rearing patterns, adolescents are not easy to adapt to new family relationships and induce bad emotions and behaviors (88).

This study has several advantages. First, the meta-analysis shows minimal publication bias. Second, the aggregate prevalence of NSSI in adolescents was broken down in terms of frequencies, severities, methods, and types. Our findings contribute to raising awareness that NSSI in adolescents is a prevalent and unaddressed issue and should be addressed urgently. On the other hand, we acknowledge the following limitations in our study. First, all the included studies were in Chinese or English, so language bias cannot be ruled out. It is not difficult to find that more than half of the research comes from China. There may be two reasons for this: first, in terms of database selection, we not only selected four English comprehensive databases, PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and PsycINFO which are representative, but also four representative databases in China were also selected. So there is more than half of research come from China. Second, China is the most populous country in the world. NSSI among adolescents has become one of the most important public health problems in China, with more and more research input and published results, more and more Chinese studies are included in meta-analysis. In this way, the final summary of research results can be more comprehensive. Of course, due to the limitations of the author’s language, the lack of in-depth analysis of other related studies in French, German, Spanish, Japanese, Korean is also one of the limitations of this study. Second, the different studies used a wide variety of screening instruments and different cut-off points for NSSI, resulting in high heterogeneity among studies. Also contributing to heterogeneity were differences in study subjects, locations, and sociocultural environments. Lastly, we cannot ignore the risk of bias due to the self-report nature of NSSI instruments, which for socially taboo topics such as NSSI and suicide may not always be fully reliable.

Conclusion

In summary, the global prevalence rate of NSSI in adolescents is high. Psychological, cognitive behavioral, family, and social interventions could be used to lower this number. Further research should be built on our findings and identify risk factors for self-harm in adolescents so that effective methods can be developed. With these actions, we can protect the health and safety of adolescents to the greatest extent possible. Administrators and the leaders of the community and hospital should create programs that teach adolescents how to deal with their emotions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

QX and XS designed the study and developed the idea in consultation with LH, DH, and XH. XS and LH were responsible for literature screening. LH, DH, and XH extracted data. QX performed the statistical analyses. QX and XS drafted the manuscript and XH revised it. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants for their contribution.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Projects of Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (grant number 2021YFS0151) and the Scientific Research Project of Sichuan Provincial Health Commission (Popularization and application project, grant number 20PJ014).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Yu CF, Xie Q, Lin SY, Liang Y, Wang GD, Nie YG, et al. Cyberbullying victimization and non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among Chinese adolescents: school engagement as a mediator and sensation seeking as a moderator. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:572521. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esposito C, Bacchini D, Affuso G. Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and its relationships with school bullying and peer rejection. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 274:1–6. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooley JM, Fox KR, Boccagno C. Nonsuicidal self-injury: diagnostic challenges and current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2020) 16:101–12. 10.2147/NDT.S198806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson K, Garisch JA, Wilson MS. Nonsuicidal self-injury thoughts and behavioural characteristics: associations with suicidal thoughts and behaviours among community adolescents. J Affect Disord. (2021) 282:1247–54. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plener PL, Kaess M, Schmahl C, Pollak S, Fegert JM, Brown RC. Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2018) 115:23–30. 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfeifer JH, Allen NB. Puberty initiates cascading relationships between neurodevelopmental, social, and internalizing processes across adolescence. Biol Psychiatry. (2021) 89:99–108. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulbas LE, Hausmann-Stabile C, De Luca SM, Tyler TR, Zayas LH. An exploratory study of nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behaviors in adolescent Latinas. Am J Orthopsychiatry. (2015) 85:302–14. 10.1037/ort0000073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L, Havertape L, Plener PL. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2012) 6:10. 10.1186/1753-2000-6-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang J, Li G, Chen B, Huang Z, Zhang Y, Chang H, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury in rural China: results from a nationwide survey in China. J Affect Disord. (2018) 226:188–95. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monto MA, McRee N, Deryck FS. Nonsuicidal self-injury among a representative sample of US adolescents, 2015. Am J Public Health. (2018) 108:1042–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunner R, Kaess M, Parzer P, Fischer G, Carli V, Hoven CW, et al. Life-time prevalence and psychosocial correlates of adolescent direct self-injurious behavior: a comparative study of findings in 11 European countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2014) 55:337–48. 10.1111/jcpp.12166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2014) 44:273–303. 10.1111/sltb.12070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim KS, Wong CH, McIntyre RS, Wang J, Zhang Z, Tran BX, et al. Global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4581. 10.3390/ijerph16224581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2015) 13:147–53. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan J, Zhu CZ, Situ MJ, Du N, Huang Y. Study on the detection rate and risk factors regarding non-suicidal serf-injurious behavior in middle school students. Chin J Epidemiol. (2012) 33:46–9. 10.1007/s11783-011-0280-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giletta M, Scholte RHJ, Engels R, Ciairano S, Prinstein MJ. Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: a cross-national study of community samples from Italy, the Netherlands and the United States. Psychiatry Res. (2012) 197:66–72. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Pierro R, Sarno I, Perego S, Gallucci M, Madeddu F. Adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: the effects of personality traits, family relationships and maltreatment on the presence and severity of behaviours. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2012) 21:511–20. 10.1007/s00787-012-0289-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sornberger MJ, Heath NL, Toste JR, McLouth R. Nonsuicidal self-injury and gender: patterns of prevalence, methods, and locations among adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2012) 42:266–78. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.0088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang J, Ma Y, Guo Y, Ahmed NI, Yu YZ, Wang JJ. Association of aggression and non-suicidal self injury: a school-based sample of adolescents. PLoS One. (2013) 8:e78149. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tormoen AJ, Rossow I, Larsson B, Mehlum L. Nonsuicidal self-harm and suicide attempts in adolescents: differences in kind or in degree? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2013) 48:1447–55. 10.1007/s00127-012-0646-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung YTD, Wong PWC, Lee AM, Lam TH, Fan YSS, Yip PSF. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of suicide among adolescents in Hong Kong. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2013) 48:1133–44. 10.1007/s00127-012-0640-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zetterqvist M, Lundh L-G, Dahlström O, Svedin CG. Prevalence and function of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a community sample of adolescents, using suggested DSM-5 criteria for a potential NSSI disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2013) 41:759–73. 10.1007/s10802-013-9712-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang S, Yan J, Zhu C, Situ M, Du N, Huang Y. The prevalence and risk factors for non-suicidal self injury among middle school students. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. (2014) 23:1013–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodav O, Levy S, Hamdan S. Clinical characteristics and functions of non-suicide self-injury in youth. Eur Psychiatry. (2014) 29:503–8. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang S, Yan J, Zhang T, Zhu C, Situ M, Du N, et al. Differences between non-suicidal self injury and suicide attempt in Chinese adolescents. Asian J Psychiatr. (2014) 8:76–83. 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evren C, Evren B, Bozkurt M, Can Y. Non-suicidal self-harm behavior within the previous year among 10th-grade adolescents in Istanbul and related variables. Nordic J Psychiatry. (2014) 68:481–7. 10.3109/08039488.2013.872699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albores-Gallo L, Mendez-Santos JL, Luna AXG, Delgadillo-Gonzalez Y, Chavez-Flores CI, Martinez OL. Nonsuicidal self-injury in a community sample of older children and adolescents of Mexico city. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. (2014) 42:159–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claes L, Luyckx K, Bijttebier P. Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: prevalence and associations with identity formation above and beyond depression. Pers Individ Dif. (2014) 6:101–4. 10.1016/j.paid.2013.12.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Claes L, Luyckx K, Baetens I, Van de Ven M, Witteman C. Bullying and victimization, depressive mood, and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: the moderating role of parental support. J Child Fam Stud. (2015) 24:3363–71. 10.1007/s10826-015-0138-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanania JW, Heath NL, Emery AA, Toste JR, Daoud FA. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents in amman. Jordan Arch Suicide Res. (2015) 19:260–74. 10.1080/13811118.2014.915778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiekens G, Bruffaerts R, Nock MK, Van de ven M, Witteman C, Mortier P, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury among Dutch and Belgian adolescents: personality, stress and coping. Eur Psychiatry. (2015) 30:743–9. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gandhi A, Luyckx K, Maitra S, Claes L. Non-suicidal self-injury and identity distress in Flemish adolescents: exploring gender differences and mediational pathways. Pers Individ Dif. (2015) 82:215–20. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calvete E, Orue I, Aizpuru L, Brotherton H. Prevalence and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in Spanish adolescents. Psicothema. (2015) 27:223–8. 10.7334/psicothema2014.262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Somer O, Bildik T, Kabukçu-Başay B, Güngör D, Başay Ö, Farmer RF. Prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury and distinct groups of self-injurers in a community sample of adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2015) 50:1163–71. 10.1007/s00127-015-1060-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim M, Yu J. Factors contributing to non-suicidal self injury in Korean adolescents. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. (2017) 28:271–9. 10.12799/jkachn.2017.28.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cimen ID, Coskun A, Etiler N. Non-suicidal self-injury behaviors’ features and relationship with adolescents’ daily life activities and mental status. Turk J Pediatr. (2017) 59:113–21. 10.24953/turkjped.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu XC, Chen H, Bo QG, Fan F, Jia CX. Poor sleep quality and nightmares are associated with non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2017) 26:271–9. 10.1007/s00787-016-0885-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin MP, You J, Ren Y, Wu JY, Hu WH, Yen CF, et al. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury and its risk and protective factors among adolescents in Taiwan. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 255:119–27. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma S, Wan Y, Zhang S, Xu S, Liu W, Xu L, et al. Mediating effect of psychological symptoms, coping styles and impulsiveness on the relationship between childhood abuses and non-suicidal self-injuries among middle school students. J Hygiene Res. (2018) 47:530–5. 10.19813/j.cnki.weishengyanjiu.2018.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang XQ, Xu WY, Li XY, Wen XT, Xie F, Huang Q, et al. Risk factors and cumulative effect of non-suicidal self injury behavior of rural senior high school students in Wuyuan. Chin J Sch Health. (2018) 39:1876–8. 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2018.12.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cui YY, Huang YY, Chen DY, Zhou L, Wang Y. Status and influencing factors of non-suicidal self-injury behaviors of middle school students in Shenzhen. South China J Prev Med. (2018) 44:416–20. 10.13217/j.scjpm.2018.0416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gandhi A, Luyckx K, Goossens L, Maitra S, Claes L. Association between non-suicidal self-injury, parents and peers related loneliness, and attitude towards aloneness in flemish adolescents: an empirical note. Psychol Belg. (2018) 58:3–12. 10.5334/pb.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X, Liu ZZ, Fan F, Jia CX. Menarche and menstrual problems are associated with non-suicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2018) 21:649–56. 10.1007/s00737-018-0861-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren YX, Lin MP, Liu YH, Zhang X, Wu JYW, Hu WH, et al. The mediating role of coping strategy in the association between family functioning and nonsuicidal self-injury among Taiwanese adolescents. J Clin Psychol. (2018) 74:1246–57. 10.1002/jclp.22587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang YQ, Ren YX, Liang QJ, You JN. The moderating role of trait hope in the association between adolescent depressive symptoms and nonsuicidal self-injury. Pers Individ Dif. (2018) 135:137–42. 10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao X, Wen S, Liu J, Lu J. Study on the prevalence and risk factors of non-suicidal self-injury among middle school students in Shenzhen. Sichuan Mental Health. (2019) 32:449–52. 10.11886/j.issn.1007-3256.2019.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen XL, Tang HM, Zou YX, Yang LX, Fu SJ, Zhang LM, et al. Relationships of bullying victimization and emotional behaviors to non-suicidal self-injury in middle school students. J Nanchang Univ. (2019) 59:71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Y, Zhang M, Guo H, Yi Y, Ma Y, Tang J. Associations of neglect and physical abuse with non-suicidal self-injury behaviors among adolescents in rural China. Chin J Sch Health. (2019) 40:984–90. 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2019.07.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma Y, Chen Y, Zhang M, Guo H, Yi Y, Ma Y, et al. Association of non-suicidal self-injury with Internet addictive behavior among adolescents. Chin J Sch Health. (2019) 40:972–6. 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2019.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu H, Wan Y, Xu S, Zhang S, Wang W, Zeng H, et al. Associations of non-suicidal self-injury with suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among middle school students. Chin Mental Health J. (2019) 33:774–8. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2019.10.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang SS, Zhang Y. The impact of parental psychological control on non-suicidal self-injury: the role of campus bullying as a mediator. Chin J Dis Control Prev. (2019) 23:459–63. 10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2019.04.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li DL, Yang R, Wan YH, Tao FB, Fang J, Zhang SC. Interaction of health literacy and problematic mobile phone use and their impact on non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2366. 10.3390/ijerph16132366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gaspar S, Reis M, Sampaio D, Guerreiro D, de Matos MG. Non-suicidal self-injuries and adolescents high risk behaviours: highlights from the portuguese HBSC study. Child Indic Res. (2019) 12:2137–49. 10.1007/s12187-019-09630-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu W, Zhou YX, Zhou F, Huang P. The influence of negative coping and maternal-child attachment on non-suicidal self-injury and their interaction among middle school students. Modern Prevent Med. (2020) 47:2351–5. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu Y, Xu H, Wan YH, Su PY, Fan YG, Ye DQ. The status and influencing factors of non-suicidal self-injury among middle school students in Anhui Province. Chin J Dis Control Prev. (2020) 24:923–8. 10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2020.08.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang Z, Xu H, Wang S, Li S, Song X, Zhang S, et al. Associations between childhood abuse experience parent-child relationship and non-suicidal self-injury in middle school students. Chin J Sch Health. (2020) 41:987–90. 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2020.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin L, Zeng F, Jiang Q, Liao M, Zhang Y, Zheng J. Associations of psychological resilience with family cohesion and non-suicidal self-injury of middle school students in Fu jian Province. Chin J Sch Health. (2020) 41:1664–7. 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2020.11.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mao C, Li Y, Li P. Relationship between parenting styles and non-suicidal self-injury in senior students: the moderating role of gender. J Shandong Univ. (2020) 58:100–5. 10.6040/j.issn.1671-7554.0.2019.1012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pang W, Wang X. Status of non-suicidal self-injury among middle school students in Zhuang nationality and its association with internet addiction. Chin J Sch Health. (2020) 41:732–5. 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2020.05.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang L, Li D, Yang R, Hu J, Wan Y, Zhang S. Associations of health literacy and screen time with non-suicidal self-injury behavior among middle school students in Shenyang. Chin J Sch Health. (2020) 41:205–8. 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2020.02.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou F, Ao C, Hu W, Hu DZ, Long XX, Huang P. Mediating role of help-seeking behaviorin relationship between being bullied and non-suicidal self-injury in middle school student. J Nanchang Univ. (2020) 60:60–5. 10.13764/j.cnki.ncdm.2020.06.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Y, Xiao YY, Ran HL, He XT, Jiang LL, Wang TL, et al. Association between parenting and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents in Yunnan, China: a cross-sectional survey. Peerj. (2020) 8:e10493. 10.7717/peerj.10493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang J, Ma Y, Lewis SP, Chen RL, Clifford A, Ammerman BA, et al. Association of internet addiction with nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents in China. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e206863. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gu HL, Ma PY, Xia TS. Childhood emotional abuse and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: the mediating role of identity confusion and moderating role of rumination. Child Abuse Neglect. (2020) 106:104474. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buelens T, Luyckx K, Kiekens G, Gandhi A, Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L. Investigating the DSM-5 criteria for non-suicidal self-injury disorder in a community sample of adolescents. J Affect Disord. (2020) 260:314–22. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liang KL, Hu SP, Li YX, Zou K, Huang XQ, Zhao L, et al. Family environment factors of non-suicidal self-injury behaviors among primary and middle school students. Modern Prevent Med. (2021) 48:304–7. 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sun W, Shen S, Zhang Z. Analysis of risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury among middle school students. J Clin Psychosom Dis. (2021) 27:83–5. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-187X.2021.01.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Costa R, Peixoto A, Lucas CCA, Falcao DN, Farias J, Viana LFP, et al. Profile of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: interface with impulsiveness and loneliness. J Pediatr. (2021) 97:184–90. 10.1016/j.jped.2020.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perez S, Garcia-Alandete J, Gallego B, Marco JHN. Characteristics and unidimensionality of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of spanish adolescents. Psicothema. (2021) 33:251–8. 10.7334/psicothema2020.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Madjar N, Sarel-Mahlev E, Klomek AB. Depression Symptoms as mediator between adolescents’ sense of loneliness at school and nonsuicidal self-injury behaviors. Crisis. (2021) 42:144–51. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jeong JY, Kim DH. Gender differences in the prevalence of and factors related to non-suicidal self-injury among middle and high school students in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:5965. 10.3390/ijerph18115965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee JY, Kim H, Kim SY, Kim JM, Shin IS, Kim SW. Non-suicidal self-injury is associated with psychotic like experiences, depression, and bullying in Korean adolescents. Early Intervent Psychiatry. (2021) 15:1696–704. 10.1111/eip.13115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tang W-C, Lin M-P, You J, Wu JY-W, Chen K-C. Prevalence and psychosocial risk factors of nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr Psychol. (2021) [Online ahead of print]. 10.1007/s12144-021-01931-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jiang Y, Ren Y, Liu T, You J. Rejection sensitivity and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: mediation through depressive symptoms and moderation by fear of self-compassion. Psychol Psychother. (2021) 94:481–96. 10.1111/papt.12293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abbasian M, Pourshahbaz A, Taremian F, Poursharifi H. The role of psychological factors in non-suicidal self-injury of female adolescents. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. (2021) 15:e101562. 10.5812/ijpbs.101562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lanfredi MMA, Ferrari C, Meloni S, Pedrini L, Ridolfi ME, Zonca V, et al. Maladaptive behaviours in adolescence and their associations with personality traits, emotion dysregulation and other clinical features in a sample of Italian students: a cross-sectional study. Borderline Pers Disord Emot Dysregul. (2021) 8:14. 10.1186/s40479-021-00154-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen WL, Chun CC. Association between emotion dysregulation and distinct groups of non-suicidal self-injury in Taiwanese female adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:3361. 10.3390/ijerph16183361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Holden RR, Lambert CE, La Rochelle M, Billet MI, Fekken GC. Invalidating childhood environments and nonsuicidal self-injury in university students: depression and mental pain as potential mediators. J Clin Psychol. (2021) 77:722–31. 10.1002/jclp.23052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Burke TA, Ammerman BA, Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Piccirillo M. Nonsuicidal self-injury scar concealment from the self and others. J Psychiatr Res. (2020) 130:313–20. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Khanipour H, Hakim Shooshtari M, Bidaki R. Suicide probability in adolescents with a history of childhood maltreatment: the role of non-suicidal self-injury, emotion regulation difficulties, and forms of self-criticism. Int J High Risk Behav Addict. (2016) 5:e23675. 10.5812/ijhrba.23675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Son Y, Kim S, Lee JS. Self-Injurious behavior in community youth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1955. 10.3390/ijerph18041955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wyman PA. Developmental approach to prevent adolescent suicides: research pathways to effective upstream preventive interventions. Am J Prev Med. (2014) 47:S251–6. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bježanèeviæ MGHI, Dodig-Æurkoviæ K. Self-injury in adolescents: a five-year study of characteristics and trends. Psychiatr Danub. (2019) 31:413–20. 10.24869/psyd.2019.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marin SHM, Sahebihagh MH, Nemati H, Ataeiasl M, Anbarlouei M, Pashapour H, et al. Epidemiology and determinants of self-injury among high school students in iran: a longitudinal study. Psychiatr Q. (2020) 91:1407–13. 10.1007/s11126-020-09764-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bresin K, Mekawi Y. Different ways to drown out the pain: a meta-analysis of the association between nonsuicidal self-injury and alcohol use. Arch Suicide Res. (2020) [Online ahead of print] 10.1080/13811118.2020.1802378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xin XWY, Fang J, Ming Q, Yao S. Prevalence and correlates of direct self-injurious behavior among Chinese adolescents: findings from a multicenter and multistage survey. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2017) 45:815–26. 10.1007/s10802-016-0201-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pawłowska B, Potembska E, Zygo M, Olajossy M, Dziurzyńska E. Prevalence of self-injury performed by adolescents aged 16-19 years. Psychiatr Pol. (2016) 50:29–42. 10.12740/PP/36501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Buist KL, Dekoviæ M, Prinzie P. Sibling relationship quality and psychopathology of children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2013) 33:97–106. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dirks MAPR, Recchia HE, Howe N. Sibling relationships as sources of risk and resilience in the development and maintenance of internalizing and externalizing problems during childhood and adolescence. Clin Psychol Rev. (2015) 42:145–55. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tschan TLJ, Schmid M, In-Albon T. Sibling relationships of female adolescents with nonsuicidal self-injury disorder in comparison to a clinical and a nonclinical control group. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2019) 13:15. 10.1186/s13034-019-0275-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nesi J, Burke TA, Lawrence HR, MacPherson HA, Spirito A, Wolff JC. Online self-injury activities among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents: prevalence, functions, and perceived consequences. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. (2021) 49:519–31. 10.1007/s10802-020-00734-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen X, Zhou Y, Li L, Hou Y, Liu D, Yang X, et al. Influential factors of non-suicidal self-injury in an eastern cultural context: a qualitative study from the perspective of school mental health profess-ionals. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:681985. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.681985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Reiter SF, Hjörleifsson S, Breidablik HJ, Meland E. Impact of divorce and loss of parental contact on health complaints among adolescents. J Public Health. (2013) 35:278–85. 10.1093/pubmed/fds101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.