Abstract

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is the prodromal stage of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Prior research shows that females are more impacted by MCI than males. On average females have a greater incidence rate of any dementia and current evidence suggests that they suffer greater cognitive deterioration than males in the same disease stage. Recent research has linked these sex differences to neuroimaging markers of brain pathology, such as hippocampal volumes. Specifically, the rate of hippocampal atrophy affects the progression of AD in females more than males. This study was designed to extend our understanding of the sex-related differences in the brain of participants with MCI. Specifically, we investigated the difference in the hippocampal connectivity to different areas of the brain. The Resting State fMRI and T2 MRI of cognitively normal individuals (n = 40, female = 20) and individuals with MCI (n = 40, female = 20) from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) were analyzed using the Functional Connectivity Toolbox (CONN). Our results demonstrate that connectivity of hippocampus to the precuneus cortex and brain stem was significantly stronger in males than in females. These results improve our current understanding of the role of hippocampus-precuneus cortex and hippocampus-brainstem connectivity in sex differences in MCI. Understanding the contribution of impaired functional connectivity sex differences may aid in the development of sex specific precision medicine to manipulate hippocampal-precuneus cortex and hippocampal-brainstem connectivity to decrease the progression of MCI to AD.

Keywords: mild cognitive impairment, sex difference, hippocampus, functional connectivity, Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

According to the CDC, there are 6.2 million people in the United States living with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) in 2021 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). This disease disproportionately affects females as they constitute more than two-thirds of the AD population (Snyder et al., 2016). The higher prevalence of AD in females has been attributed to females having greater longevity compared to males (Guerreiro and Bras, 2015). Since age is the greatest risk factor for the development of AD, it would be reasonable to state that more females would live long enough to develop AD. However, increasing evidence suggests there are other factors contribute to the sex-specific risk of AD such as genetics, hormonal differences, rate of depression, education level, and sleep disturbances (Andrew and Tierney, 2018; Mielke, 2019; Pearce et al., 2022).

The most important predictor is mild cognitive impairment (MCI) that always precedes AD, usually years before meeting the diagnostic criteria of clinical dementia (Petersen, 2004). MCI is defined as cognitive decline greater than expected for a given age but does not notably interfere with daily activities (Salmon, 2011). Current clinical evidence demonstrates about a 20% annual conversion rate of MCI to AD and that more than half of the individuals with MCI progress to dementia within 5 years (Gauthier et al., 2006; Davatzikos et al., 2011; López et al., 2020; McGrattan et al., 2022). In addition to prevalence differences, females experience greater cognitive deterioration than males in the same disease stage (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016) that are also present in individuals with MCI (Sohn et al., 2018). Compared to males with AD, females perform worse on a variety of neuropsychological tasks and have greater total brain atrophy and temporal lobe degeneration (Henderson and Buckwalter, 1994; Chapman et al., 2011; Gumus et al., 2021). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data collected through the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study attested to the faster atrophic rate (Hua et al., 2010). The hippocampus is also known to be affected at the earliest stages of MCI, even before a diagnosis can be made (Braak and Braak, 1995), and hippocampal atrophy has been found to affect the progression of AD only in females (Burke et al., 2019). Recent research revealed additional brain imaging markers that may also contribute to the sex differences in AD and are specifically present in individuals with MCI and that reduced hippocampal volume and any microhemorrhage, regardless of location, are the best MRI features to predict the transition from pre-MCI to MCI (Ferretti et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2022). Cavedo et al. (2018) found that males with MCI had a higher anterior cingulate cortex amyloid load and glucose hypometabolism in the precuneus, posterior cingulate, and inferior parietal cortex. Similar findings have been reported among cognitively normal adults (Rahman et al., 2020) suggesting that males have a higher brain resilience. However, the role of sex-related differences in hippocampal connectivity during MCI has not been elucidated yet.

This study was designed to extend the understanding of the mechanism underlying the sex differences in pathophysiological biomarkers in individuals with MCI. Our hypothesis was that hippocampal functional connectivity (FC) to the precuneus cortex and the brain stem shows sex-and MCI-specific differences. The FC of the hippocampus will be analyzed and compared between females and males with MCI, as well as cognitively normal females and males as controls.

Materials and methods

Data source

The data for this study were extracted from the ADNI1, which is a publicly accessible dataset available at adni.loni.usc.edu. Launched in 2003, ADNI is a longitudinal, multi-site, cohort study, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The original study, ADNI-1, has been extended three times and the database contains subject data from ADNI-1, ADNI-GO, ADNI-2, and ADNI-3. The overall goal of the studies was to evaluate whether serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org.

Screening process

The data were screened for subjects with MCI. To eliminate multiple images from the same subject, the data included early MCI (EMCI), late MCI (LMCI), or MCI from the 1-year subject visit of ADNI-1, ADNI-GO, ADNI-2, and ADNI-3. Subjects’ selection was also limited to those with data collected from resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) and 3.0-Tesla T2 magnetic resonance imaging. A similar search methodology was applied for cognitively normal (CN) subjects. The screening resulted in a total of 40 MCI females, 42 MCI males, 25 CN females, and 20 CN males. To balance the number of subjects in each group, 20 of each group were randomly selected for the study. Demographics of MCI subjects are provided in Table 1. This includes age, Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype, the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Geriatric Depression (GD) Scale, the Global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), and the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ), and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q). IBM SPSS (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, United States) was used to run independent t-tests to ensure there was not a statistically significant sex difference in age, MMSE, GD Scale, CDR, FAQ and NPI-Q (P > 0.05). If normal distribution could not be assumed based on the Shapiro–Wilk test, a non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was performed. These values are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Mild cognitive impairment subject demographics.

| ID | Sex | Age | ApoE genotype | MMSE | GD Scale | CDR | FAQ | NPI-Q |

| S001 | F | 74 | ε3 ε3 | 26 | 6 | 0.5 | 0 | 3 |

| S002 | F | 65 | ε4 ε4 | 25 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| S003 | F | 71 | ε4 ε4 | 29 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| S004 | F | 80 | ε3 ε3 | 25 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 |

| S005 | F | 70 | ε3 ε3 | 30 | 5 | 0.5 | 0 | - |

| S006 | F | 65 | ε4 ε4 | 27 | 7 | 1.0 | 30 | 10 |

| S007 | F | 79 | ε3 ε3 | 29 | 0 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 |

| S008 | F | 58 | ε3 ε4 | 30 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 3 |

| S009 | F | 76 | ε3 ε4 | 26 | 7 | 0.5 | 4 | 8 |

| S010 | F | 61 | ε3 ε3 | 29 | 3 | 0.5 | 5 | 0 |

| S011 | F | 72 | ε3 ε4 | 28 | 2 | 1.0 | 19 | 16 |

| S012 | F | 72 | ε3 ε3 | 28 | 5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| S013 | F | 84 | ε3 ε3 | 28 | 6 | 0.5 | 8 | 0 |

| S014 | F | 69 | ε3 ε3 | 26 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| S015 | F | 72 | ε3 ε3 | 30 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 3 |

| S016 | F | 72 | ε3 ε4 | 28 | 0 | 0.5 | 6 | 4 |

| S017 | F | 81 | ε3 ε4 | 25 | 2 | 0.5 | 7 | 3 |

| S018 | F | 77 | ε3 ε3 | 29 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 2 |

| S019 | F | 67 | ε3 ε3 | 29 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| S020 | F | 63 | ε3 ε3 | 29 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| S021 | M | 68 | ε3 ε4 | 29 | 0 | 0.5 | 2 | 3 |

| S022 | M | 72 | ε3 ε4 | 29 | 0 | 0.5 | 12 | 4 |

| S023 | M | 62 | ε4 ε4 | 29 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| S024 | M | 58 | ε3 ε3 | 25 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 |

| S025 | M | 74 | ε3 ε4 | 28 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 | 2 |

| S026 | M | 63 | ε2 ε3 | 30 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 |

| S027 | M | 90 | ε3 ε3 | 26 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | 11 |

| S028 | M | 86 | ε3 ε3 | 25 | 1 | 0.5 | 6 | 3 |

| S029 | M | 87 | ε3 ε4 | 29 | 1. | 1.0 | 10 | 12 |

| S030 | M | 70 | ε2 ε4 | 28 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 |

| S031 | M | 74 | ε2 ε3 | 30 | 3 | 0.5 | 0 | 2 |

| S032 | M | 75 | ε3 ε4 | 27 | 5 | 1.0 | 21 | 7 |

| S033 | M | 69 | ε3 ε3 | 27 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 |

| S034 | M | 74 | ε3 ε3 | 29 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| S035 | M | 77 | ε2 ε3 | 28 | 6 | 0.5 | 7 | 8.0 |

| S036 | M | 80 | ε3 ε4 | 21 | 3 | 1.0 | 22 | 4 |

| S037 | M | 73 | ε3 ε4 | 30 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 |

| S038 | M | 76 | ε3 ε3 | 30 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| S039 | M | 62 | ε4 ε4 | 27 | 5 | 0.5 | 3 | 7 |

| S040 | M | 76 | ε3 ε3 | 23 | 5 | 0.5 | 3 | 4 |

| Female μ ± SD | 71 ± 7.1 | - | 27.7 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 2.4 | 0.55 ± 0.16 | 4.4 ± 7.7 | 3.0 ± 4.1 | |

| Male μ ± SD | 73 ± 8.5 | - | 27.5 ± 2.5 | 2.1 ± 1.9 | 0.6 ± 0.21 | 5.0 ± 6.5 | 4.1 ± 3.5 | |

| Between sex t-tests | P = 0.44 | - | P = 0.95 | P = 0.58 | P = 0.38 | P = 0.22 | P = 0.12 | |

Bold values represented by Mean±STD and p-values.

Analysis of functional connectivity and statistical testing

The subject’s original rs-fMRI and MRI images (NiFTI format) were imported into the NITRC Functional Connectivity Toolbox (CONN) version 20b (Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon, 2012). CONN utilizes SPM12 (Welcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, United Kingdom) and MATLAB R2020a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, United States) in its processes and by default a combination of the Harvard-Oxford atlas (HOA distributed with FSL2) (Smith et al., 2004; Woolrich et al., 2009; Jenkinson et al., 2012) and the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002).

The images were processed through the default functional and structural preprocessing pipeline as detailed in Nieto-Castanon (2020). This included realignment, slice timing correction, coregistration/normalization, segmentation, outlier detection, and smoothing. Additionally, this step extracted the blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) time series from the regions of interest (ROIs) and at the voxels. Next, the images were denoised to remove confounding effects from the BOLD signal through linear regression and band-pass filtering. A quality assurance check was made after the denoising to ensure normalization and that there were no visible artifacts in the data.

A seed-to-voxel analysis was conducted for each subject. This analysis created a seed-based connectivity (SBC) map between the ROI (left or right hippocampus) to every voxel of the brain. The SBC map is computed as the Fisher-transformed bivariant correlation coefficients between the ROI BOLD time series and each individual voxel BOLD time series (Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon, 2012). The mathematical relationship to construct the SBC is shown below

where R is the average ROI BOLD timeseries, S is the BOLD timeseries at each voxel, r is the spatial map of Pearson correlation coefficients, and Z is the SBC map of the Fisher-transformed correlation coefficients for the ROI. Finally, F-tests were conducted between the SBC maps to compare differences between groups. For a cortical area to be considered significant, the toolbox used the Gaussian Random Field theory parametric statistics, with a cluster threshold p < 0.05 (FDR-corrected) and voxel threshold p < 0.001 (uncorrected) to control the type I error in multiple comparisons (Worsley et al., 1996). Additionally, the area must have been over 800 voxels large or cover more than 80 percent of a given atlas (specific brain area).

Results

The brain regions identified to be significantly different between the MCI and CN groups are shown in Table 2. The left and right para hippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, and amygdala all had significant between-group differences in both sexes. The regions that had a sex-specific were the Precuneus Cortex and the Brainstem, observed only in males.

TABLE 2.

Brain regions with a significant difference between mild cognitive impairment and cognitively normal for each sex.

| Sex | ROI | Brain area (Atlas) | % Atlas covered | # Of voxels |

| Female (FMCI v FCN) | Right Hippocampus | Left Posterior Para Hippocampal Gyrus | 89% | 346 |

| Right Posterior Para Hippocampal Gyrus | 89% | 283 | ||

| Right Hippocampus | 100% | 342 | ||

| Left Hippocampus | 94% | 318 | ||

| Right Amygdala | 100% | 342 | ||

| Left Amygdala | 97% | 318 | ||

| Left Hippocampus | Left Posterior Para Hippocampal Gyrus | 91% | 354 | |

| Right Posterior Para Hippocampal Gyrus | 90% | 288 | ||

| Right Hippocampus | 98% | 684 | ||

| Left Hippocampus | 100% | 761 | ||

| Right Amygdala | 94% | 322 | ||

| Left Amygdala | 100% | 327 | ||

| Male (MMCI v MCN) | Right | Brain Stem | 24% | 1001 |

| Hippocampus | Precuneus Cortex | 18% | 993 | |

| Left Posterior Para Hippocampal Gyrus | 97% | 380 | ||

| Right Posterior Para Hippocampal Gyrus | 97% | 308 | ||

| Right Hippocampus | 98% | 685 | ||

| Left Hippocampus | 100% | 760 | ||

| Right Amygdala | 100% | 342 | ||

| Left Amygdala | 100% | 327 | ||

| Left | Brain Stem | 20% | 829 | |

| Hippocampus | Precuneus Cortex | 20% | 1132 | |

| Left Posterior Para Hippocampal Gyrus | 92% | 358 | ||

| Right Posterior Para Hippocampal Gyrus | 94% | 299 | ||

| Right Hippocampus | 98% | 685 | ||

| Left Hippocampus | 100% | 760 | ||

| Right Amygdala | 99% | 337 | ||

| Left Amygdala | 100% | 327 |

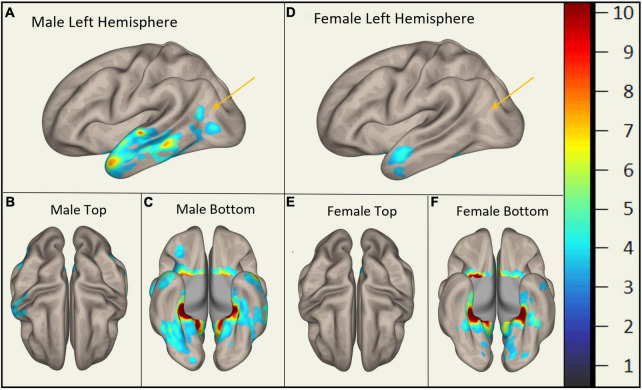

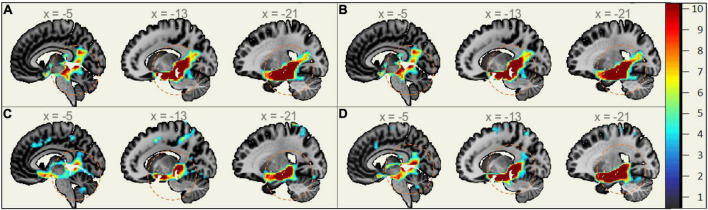

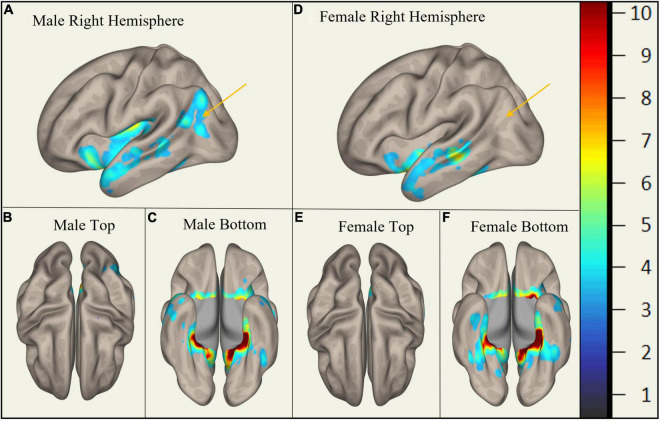

In MCI, males showed significantly stronger connectivity of the right or left hippocampus to the left or right precuneus cortex, respectively. This difference is shown visually by comparing boxes A and D (see Figures 1–3). There was also a sex specific difference detected in the brain stem. This is visualized in Figure 3.

FIGURE 1.

Sex-Specific Pathological Features with Right Hippocampus as ROI. Highlighted display the statistically significant cortical regions between mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and cognitively normal (CN) (p < 0.001) normalized to a 1–10 scale. Orange arrows indicate the areas of difference at the precuneus cortex. Panels (A–C) display MMCI v MCN. Panels (D–F) display FMCI v FCN.

FIGURE 3.

Sex-Specific Pathological Features Sagittal View. Highlighted Areas display the statistically significant regions between cognitively normal (CN) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (p < 0.001) normalized to a 1–10 scale. Orange circles indicate the area of difference in the brain stem and provide size reference between subplots. (A) Right Hippocampus ROI MMCI v MCN. (B) Left Hippocampus ROI MMCI v MCN. (C) Right Hippocampus ROI FMCI v FCN. (D) Left Hippocampus ROI FMCI v FCN.

FIGURE 2.

Sex-Specific Pathological Features with Left Hippocampus as ROI. Highlighted areas display the statistically significant cortical regions between mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and cognitively normal (CN) (p < 0.001) normalized to a 1–10 scale. Orange arrows indicate the area of difference at the precuneus cortex. Panels (A–C) display MMCI v MCN. Panels (D–F) display FMCI v FCN.

Discussion

This study supports that there are sex differences in pathophysiological biomarkers of the brain in MCI. Specifically, it extends our current understanding of the role of the hippocampus in these differences. We demonstrate that hippocampal functional connectivity differs to the precuneus cortex and the brain stem between males and females.

The differences found between the MCI and cognitively normal groups across sexes (posterior para hippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, and amygdala) are consistent with prior studies. The posterior para hippocampal gyrus is the cortical ridge in the medial temporal lobe. It contains the hippocampus (covering it medially) and amygdala (covering it anteromedially) (Goel, 2015). These structures are highly integrated and significant in the process of associative memory (Weniger et al., 2004). It has been shown that functional connectivity between the hippocampus and amygdala to different regions of the brain is disrupted in MCI (Wang et al., 2011; Ortner et al., 2016). This is consistent with our findings.

The role of the precuneus cortex is consistent with other literature highlighting its importance in the development of AD. The precuneus cortex is in the posteromedial portion of the parietal lobe. This area has a central role in a wide range of integrated tasks, including visuo-spatial imagery, episodic memory retrieval, and self-processing operations (Cavanna and Trimble, 2006). The precuneus cortex has been shown to have significantly greater activation in MCI, compared to controls, during visual encoding memory tasks (Rami et al., 2012). Prior studies have shown that functional connectivity between the hippocampus and precuneus cortex differs between individuals with early AD and healthy controls (Kim et al., 2013; Yokoi et al., 2018). However, these studies do not extend to differences between sexes. It has been shown that in individuals with subjective memory complaints, males compared to females had glucose hypometabolism in the precuneus cortex (Cavedo et al., 2018). Our findings extend this knowledge of differences between males and females in the precuneus cortex and show that the effect of MCI on the hippocampal-precuneus cortex functional connectivity may be contributing to the high prevalence of MCI in females.

Previous studies observed that functional connectivity of the locus coeruleus (LC) and the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in the midbrain of the brain stem differ in individuals with AD and MCI. Specifically, the connectivity between the VTA and the para hippocampal gyrus and cerebellar vermis were associated with the occurrence of neuropsychiatric symptoms of AD (Serra et al., 2018). Other studies showed that reduced connectivity between the LC and para hippocampal gyrus in MCI was correlated with memory performance (Jacobs et al., 2015). The difference in functional connectivity seen between males and females in this study extends these known connectivity differences seen between MCI and controls to an additional sex difference. This may be a factor in the observed worse neuropsychological tasks seen in females.

The sex differences observed in MCI have also been attributed to other factors besides functional connectivity. For example, cognitive reserve, referring to education and premorbid intelligence (IQ), is associated with the progression of MCI to AD (Osone et al., 2014). Furthermore, Giacomucci et al. (2022) reported that sex interacts with cognitive reserve and influences the onset and severity of subjective cognitive decline. Additionally, sex differences in the progression of AD from MCI have been correlated with the ApoE ε4 allele, a well-known risk factor for AD. It has been observed that ApoE ε4 is only significantly correlated to the progression of AD in females (Kim et al., 2015).

In summary, these findings are significant as they expand our current understanding of the role of the hippocampus-precuneus cortex and hippocampus-brainstem connectivity in sex differences in MCI. Understanding these sex differences in pathophysiology may aid in the development of sex-specific precision medicine to manipulate hippocampal-precuneus cortex and hippocampal-brainstem connectivity to decrease the progression of MCI to AD. Our findings provide the rationale for sex-specific interventions such as cognitive training (Hardcastle et al., 2022) and neuro-navigation guided, targeted non-invasive brain stimulation (Mackenbach et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021) or their combination (Vecchio et al., 2022).

Limitations and Future Work are related to this study’s number of subjects. While this research provides preliminary findings on sex differences in functional connectivity of the hippocampus in individuals with MCI, the small sample size (n = 80) is a limitation. Therefore, future work includes increasing sample size in a larger database, as well as expanding functional connectivity from other regions of interest for MCI, in addition to the hippocampus. Furthermore, studies such as these could be furthered by combining mentioned risk factors such as cognitive reserve or genetic differences to explore if there is any connection.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

JW conducted the study and drafted the manuscript. YY contributed to conceptualization, problem solving, and guidance during the conduction of the study. AY, PM, DW, WS, CC, and YY participated in editing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Runfeng Tian for his help and suggestion in data preprocessing. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number: W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research and Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck and Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Funding

This research was supported by a seed grant from the Vice President for Research and Partnerships of the University of Oklahoma and the Data Institute for Societal Challenges. This work was also supported by the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (OCAST) Health Research Program HR21-164, the American Heart Association (#966924), Oklahoma Shared Clinical and Translational Resources (U54GM104938) with an Institutional Development Award from National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIA-supported Geroscience Training Program in Oklahoma (T32AG052363), Oklahoma Nathan Shock Center (P30AG050911), and Cellular and Molecular GeroScience CoBRE (P20GM125528).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association (2016). 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 12 459–509. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew M. K., Tierney M. C. (2018). The puzzle of sex, gender and Alzheimer’s disease: Why are women more often affected than men? Womens Health 14:1745506518817995. 10.1177/1745506518817995 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Braak E. (1995). Staging of Alzheimer’s disease- related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol. Aging. 16 271–278. 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00021-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke S. L., Tianyan H., Fava N. M., Li T., Rodriguez M. J., Schuldiner K. L., et al. (2019). Sex differences in the development of mild cognitive impairment and probable Alzheimer’s disease as predicted by the hippocampal volume or white matter hyperintensities. J. Women Aging 31 140–164. 10.1080/08952841.2018.1419476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna A. E., Trimble M. R. (2006). The precuneus: A review of its functional anatomy and behavioral correlates. Brain 129 564–583. 10.1093/brain/awl004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavedo E., Chiesa P. A., Houot M., Ferretti M. T., Grothe M. J., Teipel S. J., et al. (2018). Sex differences in functional and molecular neuroimaging biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease in cognitively normal older adults with subjective memory complaints. Alzheimers Dement. 14 1204–1215. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Alzheimer’s Disease. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/dotw/alzheimers/index.html (accessed March 9, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Chapman R. M., Mapstone M., Gardner M. N., Sandoval T. C., McCrary J. W., Guillily M. D., et al. (2011). Women have farther to fall: Gender differences between normal elderly and Alzheimer’s disease in verbal memory engender better detection of Alzheimer’s disease in women. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 17 654–662. 10.1017/S1355617711000452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davatzikos C., Bhatt P., Shaw L. M., Batmanghelich K. N., Trojanowski J. Q. (2011). Prediction of MCI to AD conversion, via MRI, CSF biomarkers, and pattern classification. Neurobiol. Aging 32 2322.e19–27. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti M., Iulita M. F., Cavedo E., Chiesa P. A., Schumacher Dimech A., Santuccione Chadha A., et al. (2018). Sex differences in Alzheimer disease–the gateway to precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14 457–469. 10.1038/s41582-018-0032-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier S., Reisberg B., Zaudig M., Petersen R. C., Ritchie K., Broich K., et al. (2006). Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 367 1262–1270. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomucci G., Mazzeo S., Padiglioni S., Bagnoli S., Belloni L., Ferrari C., et al. (2022). Gender differences in cognitive reserve: Implication for subjective cognitive decline in women. Neurol. Sci. 43 2499–2508. 10.1007/s10072-021-05644-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel A. (2015). Parahippocampal Gyrus. Available online at: 10.53347/rID-34499 (accessed May 20, 2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro R., Bras J. (2015). The age factor in Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Med. 7 1–3. 10.1186/s13073-015-0232-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumus M., Multani N., Mack M. L., Tartaglia M. C. (2021). Progression of neuropsychiatric symptoms in young-onset versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Geroscience. 43 213–223. 10.1007/s11357-020-00304-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle C., Hausman H. K., Kraft J. N., Albizu A., O’Shea A., Boutzoukas E. M., et al. (2022). Proximal improvement and higher-order resting state network change after multidomain cognitive training intervention in healthy older adults. Geroscience 44 1011–1027. 10.1007/s11357-022-00535-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson V. W., Buckwalter J. G. (1994). Cognitive deficits of men and women with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 44 90–96. 10.1212/WNL.44.1.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X., Hibar D. P., Lee S., Toga A. W., Jack C. R., Jr., Weiner M. W., et al. (2010). Sex and age differences in atrophic rates: An ADNI study with n = 1368 MRI scans. Neurobiol. Aging 31 1463–1480. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs H. I. L., Wiese S., van de Ven V., Gronenschild E. H., Verhey F. R., Matthews P. M., et al. (2015). Relevance of parahippocampal-locus coeruleus connectivity to memory in early dementia. Neurobiol. Aging 36 618–626. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M., Beckmann C. F., Behrens T. E., Woolrich M. W., Smith S. M. (2012). FSL. Neuroimage 62 782–790. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Sheng C., Chen G., Liu C., Jin S., Li L., et al. (2022). Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Glucose metabolism patterns: A potential index to characterize brain ageing and predict high conversion risk into cognitive impairment. Geroscience. 10.1007/s11357-022-00588-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim Y. H., Lee J. H. (2013). Hippocampus–precuneus functional connectivity as an early sign of Alzheimer’s disease: A preliminary study using structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging data. Brain Res. 1495 18–29. 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Kim M. J. S., Kim H. S., Kang S. W., Lim W., Myung W., et al. (2015). Gender differences in risk factors for transition from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: A CREDOS study. Compr. Psychiatry 62 114–122. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López M. E., Turrero A., Cuesta P., Rodríguez-Rojo I. C., Barabash A., Marcos A., et al. (2020). A multivariate model of time to conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Geroscience. 42 1715–1732. 10.1007/s11357-020-00260-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach C., Tian R., Yang Y. (2020). “Effects of electrode configurations and injected current intensity on the electrical field of transcranial direct current stimulation: A simulation study,” in Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (Montreal, QC: EMBC; ), 3517–3520. 10.1109/EMBC44109.2020.9176686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrattan A. M., Pakpahan E., Siervo M., Mohan D., Reidpath D. D., Prina M., et al. (2022). Risk of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia in low-and-middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Assoc. 8:e12267. 10.1002/trc2.12267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke M. M. (2019). Sex and gender differences in Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Psychiatr. Times 35 14–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Castanon A. (2020). Handbook of Functional Connectivity Magnetic Resonance Imaging Methods in CONN. Boston, MA: Hilbert Press. 10.56441/hilbertpress.2207.6598 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortner M., Pasquini L., Barat M., Alexopoulos P., Grimmer T., Förster S., et al. (2016). Progressively disrupted intrinsic functional connectivity of basolateral amygdala in very early Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurol. 7:132. 10.3389/fneur.2016.00132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osone A., Arai R., Hakamada R., Shimoda K. (2014). Impact of cognitive reserve on the progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 15 428–234. 10.1111/ggi.12292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce E. E., Alsaggaf R., Katta S., Dagnall C., Aubert G., Hicks B. D., et al. (2022). Telomere length and epigenetic clocks as markers of cellular aging: A comparative study. Geroscience 44 1861–1869. 10.1007/s11357-022-00586-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen R. C. (2004). Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J. Intern. Med. 256 183–194. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A., Schelbaum E., Hoffman K., Diaz I., Hristov H., Andrews R., et al. (2020). Sex-driven modifiers of Alzheimer risk a multimodality brain imaging study. Neurology 95 e166–e178. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rami L., Sala-Llonch R., Solé-Padullés C., Fortea J., Olives J., Lladó A., et al. (2012). Distinct functional activity of the precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex during encoding in the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 31 517–526. 10.3233/JAD-2012-120223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon D. P. (2011). Neuropsychological features of mild cognitive impairment and preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 10 187–212. 10.1007/7854_2011_171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra L., Di Domenico C., D’Amelio M., Dipasquale O., Marra C., Mercuri N. B., et al. (2018). In vivo mapping of brainstem nuclei functional connectivity disruption in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 72 72–82. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M., Jenkinson M. W., Woolrich C. F., Beckmann T. E. J., Behrens H., Johansen-Berg P. R., et al. (2004). Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23 208–219. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H. M., Asthana S., Bain L., Brinton R., Craft S., Dubal D. B., et al. (2016). Sex biology contributions to vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease: A think tank convened by the women’s Alzheimer’s research initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 12 1186–1196. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn D., Shpanskaya K., Lucas J. E., Petrella J. R., Saykin A. J., Tanzi R. E., et al. (2018). “Sex differences in cognitive decline in subjects with high likelihood of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 8:7490. 10.1038/s41598-018-25377-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N., Landeau B., Papathanassiou D., Crivello F., Etard O., Delcroix N., et al. (2002). Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage 15 273–289. 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchio F., Quaranta D., Pappalettera C., Di Iorio R., L’Abbate F., et al. (2022). Neuronavigated magnetic stimulation combined with cognitive training for Alzheimer’s patients: An EEG graph study. Geroscience 44 159–172. 10.1007/s11357-021-00508-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Liang P., Jia X., Qi Z., Yu L., Yang Y., et al. (2011). Baseline and longitudinal patterns of hippocampal connectivity in mild cognitive impairment: Evidence from resting state fMRI. J. Neurol. Sci. 309 79–85. 10.1016/j.jns.2011.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weniger G., Boucsein K., Irle E. (2004). Impaired associative memory in temporal lobe epilepsy subjects after lesions of hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, and amygdala. Hippocampus 14 785–796. 10.1002/hipo.10216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli S., Nieto-Castanon A. (2012). Conn: A functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2, 125–141. 10.1089/brain.2012.0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolrich M. W., Jbabdi S., Patenaude B., Chappell M., Makni S., Behrens T., et al. (2009). Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. Neuroimage 45 S173–S186. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley K. J., Marrett S., Neelin P., Vandal A. C., Friston K. J., Evans A. C. (1996). A unified statistical approach for determining significant signals in images of cerebral activation. Hum. Brain Mapp. 4 58–73. Yang Y., Sidorov E., Dewald J. P. (2021). Targeted tDCS reduces the expression of the upper limb flexion synergy in chronic hemiparetic stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 102:e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Sidorov E. V., Dewald J. P. (2021). Targeted tDCS reduces the expression of the upper limb flexion synergy in chronic hemiparetic stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 102:e10. 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.07.418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi T., Watanabe H., Yamaguchi H., Bagarinao E., Masuda M., Imai K., et al. (2018). Involvement of the precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex is significant for the development of Alzheimer’s disease: A PET (THK5351, PiB) and resting fMRI study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10:304. 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.