Abstract

Chemotaxis to the aromatic acid 4-hydroxybenzoate (4-HBA) by Pseudomonas putida is mediated by PcaK, a membrane-bound protein that also functions as a 4-HBA transporter. PcaK belongs to the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) of transport proteins, none of which have so far been implicated in chemotaxis. Work with two well-studied MFS transporters, LacY (the lactose permease) and TetA (a tetracycline efflux protein), has revealed two stretches of amino acids located between the second and third (2-3 loop) and the eighth and ninth (8-9 loop) transmembrane regions that are required for substrate transport. These sequences are conserved among most MFS transporters, including PcaK. To determine if PcaK has functional requirements similar to those of other MFS transport proteins and to analyze the relationship between the transport and chemotaxis functions of PcaK, we generated strains with mutations in amino acid residues located in the 2-3 and 8-9 loops of PcaK. The mutant proteins were analyzed in 4-HBA transport and chemotaxis assays. Cells expressing mutant PcaK proteins had a range of phenotypes. Some transported at wild-type levels, while others were partially or completely defective in 4-HBA transport. An aspartate residue in the 8-9 loop that has no counterpart in LacY and TetA, but is conserved among members of the aromatic acid/H+ symporter family of the MFS, was found to be critical for 4-HBA transport. These results indicate that conserved amino acids in the 2-3 and 8-9 loops of PcaK are required for 4-HBA transport. Amino acid changes that decreased 4-HBA transport also caused a decrease in 4-HBA chemotaxis, but the effect on chemotaxis was sometimes slightly more severe. The requirement of PcaK for both 4-HBA transport and chemotaxis demonstrates that P. putida has a chemoreceptor that differs from the classical chemoreceptors described for Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium.

Aromatic compounds are commonly present in the environment as breakdown products of the complex plant polymer lignin and as environmental pollutants. The enzymology and genetic regulation of metabolic pathways required for the aerobic degradation of a variety of aromatic acids and aromatic hydrocarbons by bacteria have been studied extensively (2, 10, 14, 27, 40). By contrast, chemotaxis and transport, two important events that precede degradation, have received little attention.

The aromatic acid 4-hydroxybenzoate (4-HBA) is a strong chemoattractant for Pseudomonas putida (15). Metabolism of 4-HBA is not required for chemotaxis because mutants blocked in 4-HBA degradation respond to 4-HBA just as well as the wild-type parent (12). In previous work, we determined that PcaK, a transporter of 4-HBA (13, 25, 26), also acts as a chemoreceptor for this compound. pcaK mutants are nonchemotactic to 4-HBA and structurally related aromatic acids including benzoate (13). The role of PcaK in chemotaxis is not simply to catalyze the intracellular accumulation of 4-HBA because at the concentrations (millimolar) at which chemotaxis is tested, sufficient 4-HBA diffuses into cells that the transport function of PcaK is not needed to allow for wild-type growth rates (13).

Although PcaK mediates chemotaxis to 4-HBA, it is not similar to the transmembrane chemoreceptors (methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins [MCPs]) that have been studied extensively in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium (37). Rather, PcaK belongs to a large group of transport proteins called the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) (23, 29). The MFS has recently been reevaluated and expanded to include 18 different transporter families that can be loosely grouped according to substrate specificities. PcaK is the founding member of the newly defined family 15 for aromatic acid/H+ symporters within the MFS (29). Permeases from the different MFS families typically share little overall sequence identity. However, all have in common 12 or 14 predicted transmembrane regions and a series of conserved amino acid residues [GXXXD(R/K)XGR(R/K)] in the cytoplasmic hydrophilic loop between the second and third (2-3 loop) membrane-spanning segments. This motif is repeated, although with a lesser degree of conservation, in the cytoplasmic hydrophilic loop between the eighth and ninth (8-9 loop) transmembrane segments of the permease. Certain amino acids within the 2-3 loop have been shown to be required for substrate transport in LacY, the lactose permease of E. coli, and TetA, a tetracycline antiporter of E. coli encoded by transposon Tn10 (19, 32, 41–43). PcaK is predicted to have 12 membrane-spanning regions, and it contains the two conserved stretches of amino acids known to be required for substrate transport by LacY and TetA.

To date, PcaK is the only MFS transporter to be implicated in chemoreception. As a start to determining how PcaK functions as both a transporter and a chemoreceptor for 4-HBA, we used site-directed mutagenesis to examine the functional significance of the PcaK 2-3 and 8-9 cytoplasmic loops for these two processes. Our results show that mutations in the 2-3 and 8-9 hydrophilic loops that affect transport also affect chemotaxis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. putida | ||

| PRS2000 | Wild type | 28 |

| PRS4085 | KmrpcaK::Km 4-HBA chemotaxis− 4-HBA transport− | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| BL21(DE3) | hsdS gal (λcIts857 ind-1 Sam7 nin-5 lacUV5-T7 gene 1) | 38 |

| DH5α | F− λ−recA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 hsdR17 thi-1 gyrA96 supE44 endA1 relA1 φ80dlacZΔM15 | Gibco-BRL |

| HB101 | F−hsdS20 recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 supE44 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 | 33 |

| S17-1 | thi pro hsdR hsdM+ recA, chromosomal insertion of RP4-2 (Tc::Mu Km::Tn7) | 34 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBBR1MCS-5 | Gmr; broad-host-range cloning vector | 21 |

| pRK415 | Tcr; IncP, broad-host-range cloning vector | 20 |

| pRK2013 | Kmr; ColE1, RK2 transfer genes | 7 |

| pT7-5 | Apr; T7 promoter expression vector | 39 |

| pUC4K | Kmr Tcr; Km resistance GenBlock | Pharmacia |

| pHJD100 | Tcr; pcaK with native promoter cloned in pRK415 | 13 |

| pHJD104 | Kmr Tcr; SalI Kmr cassette fragment from pUC4K inserted in SalI site of pcaK cloned in pRK415 | This study |

| pHJD193 | Gmr; pcaK with native promoter cloned in pBBR1MCS-5 | This study |

| pHNN100 | Apr; pcaK lacking native promoter cloned in pT7-5 | 13 |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Gmr, gentamicin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance.

Media and growth conditions.

Cultures of P. putida were grown at 30°C in a defined mineral medium (minimal medium) that contained 25 mM KH2PO4, 25 mM Na2HPO4, 0.1% (NH4)2SO4, and 1% Hutner mineral base (final pH, 6.8) (8). 4-HBA was sterilized separately and added at the time of inoculation to a final concentration of 5 mM. E. coli strains were grown in LB broth (3) at 37°C. Wild-type and mutant PcaK proteins were expressed in E. coli from a T7 promoter by diluting an overnight culture into 50 ml of fresh LB media and incubating to an A660 of 0.3. Cultures were then induced by the addition of 0.4 mM isopropylthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Incubation was continued at 37°C until the A660 of the culture had approximately doubled. For P. putida, the antibiotics gentamicin and kanamycin were used at final concentrations of 5 and 100 μg/ml, respectively; for E. coli, ampicillin, gentamicin, kanamycin, and tetracycline were used at final concentrations of 100, 20, 100, and 100 μg/ml, respectively.

Bacterial transformations and conjugations.

Plasmids carrying tetracycline resistance genes were mobilized from E. coli S17-1 into P. putida by patch matings on LB agar plates with incubation overnight at 30°C. Plasmids carrying gentamicin resistance genes were mobilized from E. coli DH5α into P. putida via a triparental mating using E. coli HB101(pRK2013) (4). E. coli was transformed with plasmid DNA by the method of Hanahan (9).

DNA manipulations and sequencing.

Plasmid DNA to be used for sequencing and subcloning was prepared with a QIAprep miniprep kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.). Restriction endonuclease digestions were done as instructed by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). DNA fragments for subcloning were purified from agarose gel slices by using a GENECLEAN Spin kit (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.). Southern hybridizations were carried out with a Genius kit (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.).

Construction of a pcaK mutant.

A P. putida pcaK mutant, PRS4085, was constructed by insertional inactivation of the pcaK gene. The 1.3-kb (SalI fragment) Kmr (kanamycin resistance) GenBlock cassette (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) was inserted into the SalI restriction site of the pcaK gene in pHJD100 to generate pHJD104 (Table 1). Plasmid pHJD104 was mobilized from E. coli S17-1 into P. putida PRS2000, and the recombinant PRS4085 from this mating was identified by screening for Kmr and tetracycline sensitivity. The chromosomal insertion was verified by Southern analysis.

Cloning of pcaK and site-directed mutagenesis.

A 1,656-bp segment of DNA, encompassing the pcaK gene and its native promoter, was amplified from pHJD100 by PCR. The upstream primer KPI (5′GCACGTGCTGCAGGTGCGATAAACGCACAGTGTCGC3′) incorporated a PstI cloning site (underlined), and the downstream primer KHI (5′CGATGGATCCTTGTGCTGCGAATGGCTCTCAAAG3′) incorporated a BamHI cloning site (underlined). The amplified DNA was then cloned into the broad-host-range vector pBBR1MCS-5 to form pHJD193 (Table 1). Plasmid pHJD193 was then used as template for the generation of site-directed mutants of pcaK by the incorporation of a phosphorylated oligonucleotide during PCR amplification (24). Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene Cloning Systems, La Jolla, Calif.) was used in PCRs to reduce base pair misincorporations. The outer amplification primers used were KPI and KHI; 5′ phosphorylated mutagenic primers were designed to incorporate one codon change and a silent restriction enzyme recognition site for screening of mutated PCR products.

For expression in E. coli, mutant pcaK genes were amplified by PCR using the pBBR1MCS-5 clones as templates. The upstream primer KRI (5′GACTGAATTCCCCAATCATCGTCCCCTGTA3′) incorporated an EcoRI cloning site (underlined). The downstream primer used was KHI. The 1,462-bp amplified PCR products, which lacked the native pcaK promoter, were each cloned into pT7-5 under control of the T7 promoter.

The nucleotide sequences of all mutant pcaK genes were verified by DNA sequencing.

Transport assays.

4-HBA transport was measured in E. coli expressing recombinant PcaK or in P. putida grown to mid-log phase on 4-HBA. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in phosphate buffer (25 mM KH2PO4, 25 mM Na2HPO4 [pH 6.8]) to an A660 of 5 to 10. The cell suspension was gently aerated at room temperature until the time of assay to prevent oxygen limitation. Transport assays were initiated by the addition of 300 μl of the cell suspension to an equal volume of phosphate buffer containing 130 μM [14C]4-HBA, 4 mM glucose, and 4 mM succinate. Samples (0.1 ml) were taken at timed intervals and filtered through Nuclepore polycarbonate membranes (0.22-μm pore size; Costar Corp., Cambridge, Mass.). The filters were washed with 2 ml of phosphate buffer before and after sample addition. The amount of accumulated substrate was determined by scintillation counting of the cells retained on the filters. Rates for 4-HBA transport in P. putida were calculated from linear time points over a 1-min time span. Transport saturated much more quickly in E. coli, usually within 5 to 10 s. For this reason, 4-HBA accumulation in E. coli was expressed over a 10-s time span.

[35S]methionine labeling of PcaK.

Cultures (1 ml) of E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pT7-5, pHNN100, or one of the pT7-5 mutant pcaK clone series were harvested at an A660 of 0.3. The cells were pelleted and washed twice in 0.5 ml of M9 medium (1) and resuspended in 1.0 ml of M9 medium containing 0.02% 18 l-amino acids, excluding cysteine and methionine. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, cultures were induced with 0.4 mM IPTG and incubated for an additional 30 min. Rifampin (from a freshly prepared methanol stock) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, and the resuspended cells were incubated for an additional 60 min at 37°C. l-[35S]methionine (10 μCi) was added, and the incubation was continued for another 5 min. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 0.5 ml of M9 medium, and disrupted by sonication. Whole cells were removed by low-speed centrifugation, and the supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation for 90 min at 174,000 × g at 4°C. The membrane pellet was suspended in 20 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer (1) and stored at −20°C. The aqueous cytoplasmic supernatant was mixed with 4 volumes of acetone and placed at −70°C for 30 min to precipitate the cytoplasmic proteins. The acetone mixture was centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000 × g. The pellet was suspended in 20 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and stored at −20°C. The membrane protein and cytoplasmic protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE on 12.5% acrylamide–0.33% bisacrylamide gels. The gels were dried and exposed to both X-ray film (−70°C for 12 h) and electronic autoradiography (Instant Imager; Packard Instrument Company, Meriden, Conn.) for quantitation.

Chemotaxis assays.

Soft agar swarm plates for qualitative assessment of chemotaxis consisted of minimal medium containing 0.1% instead of 1% Hutner mineral base, 0.3% Noble agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), and the carbon source 4-HBA (the chemoattractant) at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Chemotaxis to 4-HBA was measured quantitatively by capillary assays as previously described (15), using cells that were grown with 4-HBA as the carbon and energy source. Chemotactic behavior was measured by counting the number of bacteria that responded to the attractant by entering a 1-μl microcapillary tube containing 5.0 mM 4-HBA over a period of 30 min.

Protein determinations.

Whole cells were precipitated with 5% trichloroacetic acid and boiled in 0.1 N NaOH for 10 min. Protein concentrations were determined by using the Bio-Rad Laboratories (Richmond, Calif.) protein assay, using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Radiochemicals.

l-[35S]methionine (83 Ci/mmol) and [ring-ul-14C]4-hydroxybenzoic acid (33 mCi/mmol) were purchased from Amersham Corp. (Arlington Heights, Ill.).

RESULTS

Construction and complementation of a pcaK mutant.

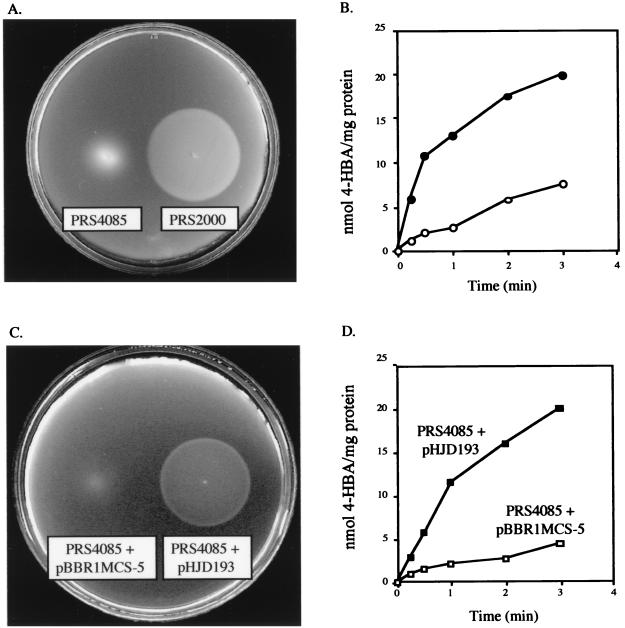

A P. putida mutant (PRS4085) that was unable to transport or respond chemotactically to 4-HBA was created by insertionally inactivating the chromosomal copy of pcaK with a Kmr cassette. When pcaK was expressed in this mutant in trans (supplied on pHJD193), both the 4-HBA transport and chemotaxis phenotypes were restored to wild-type levels as determined by [14C]4-HBA transport and 4-HBA swarm plate assays (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

4-HBA transport and chemotaxis phenotypes of wild-type and pcaK mutant strains of P. putida. (A) Chemotactic swarms formed by wild-type P. putida PRS2000 and the pcaK mutant strain PRS4085 on a soft agar plate containing 0.5 mM 4-HBA. Plates were inoculated with motile cells at a point corresponding to the center of the swarm ring and incubated for 20 h at 30°C. The wild-type response is represented by a large sharp ring that is generated in response to a gradient of 4-HBA that is created by the cells as they metabolize the carbon source. The fuzzy small ring reflects random movement of motile cells that cannot detect 4-HBA. (B) Cells of PRS4085 ( ) accumulated 4-HBA at a substantially lower rate than wild-type PRS2000 cells (●). (C) PcaK complements the mutant 4-HBA chemotaxis phenotype. The pcaK gene, expressed in trans from pHJD193, complements the PRS4085 chemotaxis phenotype on 4-HBA soft agar plates comparable to those of the wild-type strain PRS2000 (A). (D) PcaK complements the mutant 4-HBA transport phenotype. The pcaK gene, expressed in trans from pHJD193 (■) in the PRS4085 mutant, accumulates 4-HBA at an increased rate compared to PRS4085 harboring the vector pBBR1MCS-5 (

) accumulated 4-HBA at a substantially lower rate than wild-type PRS2000 cells (●). (C) PcaK complements the mutant 4-HBA chemotaxis phenotype. The pcaK gene, expressed in trans from pHJD193, complements the PRS4085 chemotaxis phenotype on 4-HBA soft agar plates comparable to those of the wild-type strain PRS2000 (A). (D) PcaK complements the mutant 4-HBA transport phenotype. The pcaK gene, expressed in trans from pHJD193 (■) in the PRS4085 mutant, accumulates 4-HBA at an increased rate compared to PRS4085 harboring the vector pBBR1MCS-5 ( ) alone. The levels of 4-HBA transport by the complemented strain were comparable to those of the wild-type strain (B).

) alone. The levels of 4-HBA transport by the complemented strain were comparable to those of the wild-type strain (B).

Isolation of pcaK site-directed mutants.

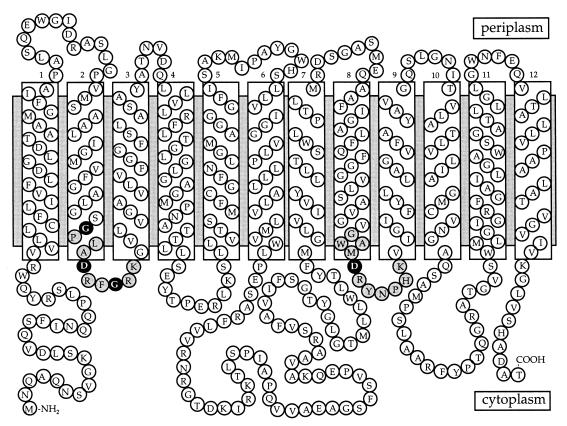

The algorithm of Jones et al. (18) was used to predict the secondary structure and membrane topology of PcaK (Fig. 2). We identified in PcaK two stretches of conserved amino acids between the 2-3 and 8-9 loops which correspond to similar segments in LacY and TetA that had previously been shown to be required for substrate transport (17, 43). Based on the LacY and TetA studies, a series of site-directed mutants were generated within the 2-3 and 8-9 loop sequences of PcaK. Within the 2-3 loop, the first-position glycine (the 85th amino acid of PcaK; Gly-85) and the fifth-position aspartate (Asp-89) were changed to a valine and an asparagine, respectively (Gly-85-Val and Asp-89-Asn changes), since the corresponding changes in LacY and TetA abolished substrate transport. The eighth-position glycine (Gly-92) of the 2-3 loop was changed to a leucine (Gly-92-Leu change), a valine (Gly-92-Val change), a glutamate (Gly-92-Glu change), an alanine (Gly-92-Ala change), or a cysteine (Gly-92-Cys change) to see if doing so created PcaK proteins with different levels of 4-HBA transport activity. The fifth-position aspartate (Asp-323) of the 8-9 loop was also targeted for mutagenesis. This aspartate corresponds to the fifth-position aspartate of the 2-3 loop, but neither LacY or TetA has this charged residue in the 8-9 cytoplasmic loop (30, 41).

FIG. 2.

Two-dimensional model of PcaK based on the algorithm of Jones et al. (18). Predicted hydrophobic transmembrane segments are enclosed in boxes. The 2-3 and 8-9 consensus transport sequences are highlighted in gray. Amino acids within the consensus transport sequences that were targeted for site-directed mutagenesis are highlighted in black with white lettering.

Mutant PcaK activity in E. coli and localization to the cell membrane.

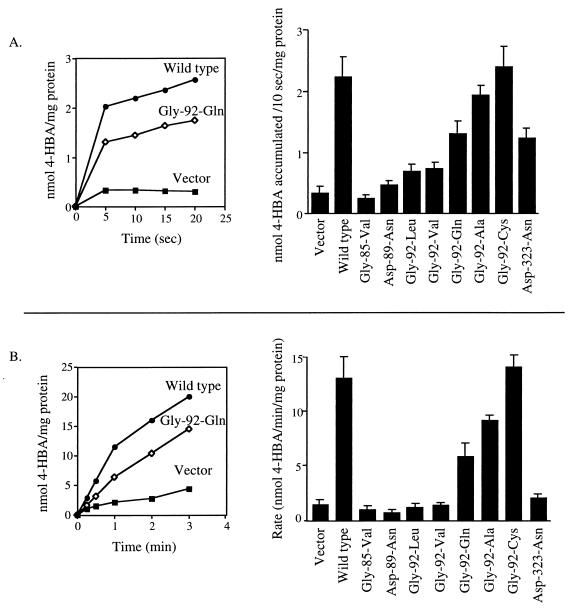

Since E. coli does not degrade 4-HBA, 4-HBA transport in the absence of metabolism could be measured in E. coli cells expressing wild-type and mutant PcaK proteins (Fig. 3A). PcaK proteins with a Gly-85-Val or Asp-89-Asn change were completely defective in the ability to catalyze 4-HBA transport. Proteins with a variety of changes at Gly-92 accumulated 4-HBA to various degrees. Gly-92-Val and Gly-92-Leu mutant proteins accumulated 4-HBA at greatly reduced levels that were, however, still significantly higher than background levels. PcaK proteins with a Gly-92-Gln or Gly-92-Ala change accumulated intermediate levels of 4-HBA, and the Gly-92-Cys mutant PcaK behaved similarly to the wild-type PcaK protein. The amount of 4-HBA transport catalyzed by the Asp-323-Asn mutant PcaK protein was reduced by 50% relative to the wild type (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Accumulation of 4-HBA by E. coli BL21(DE3) (A) or P. putida PRS4085 (B) expressing wild-type and mutant PcaK proteins. Proteins were expressed in E. coli from the expression plasmid pT7-5 and in P. putida from the broad-host-range vector pBBR1MCS-5. The bar graphs in each panel represent the average level of 4-HBA accumulation for at least six separate experiments, each done in duplicate. Standard deviations are represented by error bars. The graphs show representative time courses for 4-HBA accumulation in E. coli (A) and P. putida (B).

To determine if the various PcaK mutations affected protein localization or levels of protein expression, wild-type and mutant PcaK proteins were labeled with l-[35S]methionine during expression in E. coli. Each mutant PcaK protein was found to be localized to the cell membrane at levels that were similar to the wild-type level (data not shown). The cytoplasmic fraction contained no labeled protein. Although E. coli cells expressing wild-type PcaK could catalyze 4-HBA transport, such cells were not chemotactic to 4-HBA (6).

Effects of pcaK mutations on 4-HBA transport by P. putida.

4-HBA transport mediated by wild-type and mutant PcaK proteins was also assayed in P. putida, so that the rates of transport and levels of chemotaxis could be compared for the same organism. Each mutant PcaK protein was expressed in the P. putida pcaK null mutant strain PRS4085, and the rate of [14C]4-HBA transport was measured (Fig. 3B). In general, the results obtained paralleled those seen with E. coli. However, the transport phenotypes of some of the mutants were more severe in the P. putida background (Table 2). For example, the Gly-92-Leu, Gly-92-Val, and Asp-323-Asn mutations allowed for measurable levels of 4-HBA transport when expressed in E. coli but were transport deficient in P. putida. PcaK mutant proteins are expressed at higher levels in E. coli than in P. putida, where they are expressed from the native pcaK promoter. This may explain the elevated rates of 4-HBA transport in E. coli.

TABLE 2.

Comparative effects of PcaK, LacY, and TetA mutations in the consensus transport sequence on 4-HBA transport and chemotaxis

| Mutationb | % Accumulation of substratea

|

% of wild-type chemotaxis to 4-HBA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PcaK

|

LacY | TetA | |||

| P. putida | E. coli | ||||

| Gly-85-Val | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asp-89-Asn | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gly-92-Leu | 0 | 17 | 91 | 30 | 2 |

| Gly-92-Val | 0 | 20 | 78 | 5 | 0 |

| Gly-92-Gln | 39 | 51 | —c | 50 | 9 |

| Gly-92-Ala | 68 | 83 | — | — | 48 |

| Gly-92-Cys | 111 | 109 | 94 | 40 | 108 |

| Asp-323-Asn | 5 | 46 | NCd | NC | 5 |

Percentage of wild-type transport for each substrate. In P. putida, 100% accumulation equals the value of 4-HBA accumulated in the pcaK mutant PRS4085 complemented with a wild-type pcaK on plasmid pHJD193; in E. coli, 100% accumulation equals the value of 4-HBA accumulated in strain BL21(DE3) expressing wild-type pcaK from the expression plasmid pHNN100. The percentages represent values corrected for background accumulation in the vector strain. Values for LacY and TetA are taken from Jessen-Marshall et al. (17) and Yamaguchi et al. (43), respectively.

Residue numbers are based on the PcaK sequence. LacY and TetA values are for the corresponding residue of the consensus sequence.

—, the corresponding residue in the protein has not been changed to the respective amino acid.

NC, no corresponding residue is present in the protein.

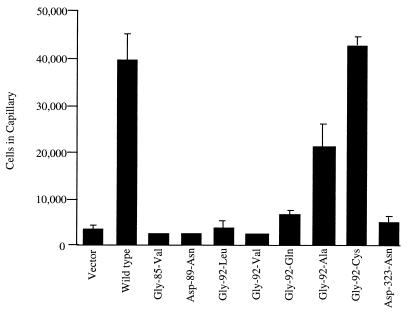

Effects of pcaK mutations on 4-HBA chemotaxis.

Each mutant PcaK protein was expressed in the P. putida pcaK null mutant strain PRS4085, and chemotaxis to 4-HBA was measured by capillary assays. PcaK mutants that did not transport 4-HBA in P. putida (Gly-85-Val, Asp-89-Asn, and Asp-323-Asn) were not chemotactic to this compound. The mutant PcaK series at Gly-92 of the 2-3 loop produced mutant PcaK proteins that could detect 4-HBA at levels ranging from background to wild type in capillary assays (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Chemotactic responses of P. putida strains expressing various mutant PcaK proteins to 4-HBA. Each mutated pcaK gene was introduced in trans into the P. putida pcaK null mutant strain PRS4085 from the broad-host-range vector pBBR1MCS-5. The chemotactic responses to 4-HBA were measured by capillary assay. The bar graph represents the average number of cells that accumulated in a microcapillary that contained 5.0 mM 4-HBA in at least four separate experiments, each done in triplicate. Standard deviations are represented by error bars.

DISCUSSION

Function of PcaK in transport.

PcaK is a membrane-bound protein that is required for both 4-HBA chemotaxis and transport by P. putida (13, 25). A topological model of PcaK (Fig. 2) indicates that it contains 12 hydrophobic regions and two stretches of amino acids, the 2-3 and 8-9 cytoplasmic hydrophilic loops, that are characteristic of all MFS transporters. It has been suggested that the 2-3 and 8-9 loop sequences play a functional role in substrate transport, possibly by acting as a gate for channel opening and closing (17). The work described here demonstrates that PcaK resembles other MFS permeases, namely, the E. coli lactose permease and tetracycline antiporter, in that specific residues within 2-3 and 8-9 hydrophilic loops are required for 4-HBA transport. The first-position glycine and the fifth-position aspartate of the 2-3 loop (GPLADRFGRK) are conserved in PcaK, and mutations to a valine (Gly-85-Val) and an asparagine (Asp-89-Asn) resulted in mutant PcaK proteins that were unable to transport 4-HBA. These results parallel those seen in LacY and TetA mutant proteins that have similar amino acid changes in their 2-3 loops (Table 2). A glycine at the first position of the consensus transport sequence is likely to be required for turn structure of the polypeptide. This has been concluded from extensive site-directed mutational studies of LacY and TetA, where only small-side-chain amino acid substitutions (alanine or serine) at the first position can partially function in substrate transport (16, 17, 43). The effects of removing the charge at the fifth-position aspartate of the PcaK 2-3 loop (Asp-89-Asn) indicate that a negative charge at this position may be required for 4-HBA transport. The importance of a charge in the fifth position of the 2-3 loop has been demonstrated in LacY and has also been shown to be critical for TetA function (17, 43).

As in LacY and TetA, the eighth-position glycine of PcaK is important but not absolutely required for substrate transport because some amino acid changes at this position allowed for 4-HBA transport. The eighth-position glycine in PcaK does not seem to be important for turn structure, because nonconservative amino acid side chain mutants (Gly-92-Gln and Gly-92-Cys) allowed for 4-HBA transport, while a more conservative change (Gly-92-Val) did not. A similar conclusion has been reached for LacY and TetA (Table 2).

In MFS permeases, the amino acid sequence of the 8-9 hydrophilic loop is not as well conserved as the 2-3 consensus hydrophilic loop. For example, neither the 8-9 loop of TetA nor that of LacY contains an aspartate residue at the fifth position corresponding to an aspartate in the 2-3 loop (30, 41). However, PcaK does have this aspartate residue in the 8-9 loop (GWAMDRYNPHK). This negative charge is required for substrate transport by PcaK in P. putida (Table 2). The charged aspartate residue in the 8-9 loop is conserved among the entire aromatic acid/H+ symporter family of the MFS (29), suggesting that this may be important for transport of aromatic acid substrates.

Function of PcaK in chemotaxis.

PcaK is, so far, unique among MFS transporters in that it mediates chemotaxis as well as transport of 4-HBA in P. putida. There is precedent for the involvement of other types of transporters in chemotaxis. One such example is glucose chemotaxis, mediated by the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent carbohydrate phosphotransferase system in E. coli. However, even in this case, it is still unclear how transport and chemotaxis are coupled (22, 31). In general, the site-directed mutants in the 2-3 and 8-9 loops of PcaK that abolished transport also abolished chemotaxis. This is consistent with the idea that 4-HBA transport is required for 4-HBA chemotaxis by PcaK. However, it is also possible that entry of 4-HBA into cells per se is not what is important, but rather that conformational changes in the 2-3 and 8-9 loops that are required for transport are also required for chemotactic signaling. In support of this view is the observation that some mutants (e.g., Gly-92-Ala and Gly-92-Gln) have a chemotaxis phenotype that is slightly more severe than the transport phenotype (Table 2).

Previous work in our laboratory has shown that PcaK is required for chemotaxis to the aromatic acid benzoate as well as 4-HBA (13). PcaK does not transport benzoate, although benzoate competitively inhibits the transport of 4-HBA (25), indicating that benzoate binds to PcaK. This finding indicates that PcaK may function in chemoreception of benzoate by binding a chemoeffector and transmitting a signal to the chemotaxis machinery via a conformational change without ligand transport being required.

A possible mechanism of PcaK-mediated chemotaxis is that a conformational change that accompanies ligand binding to the periplasmic surface of PcaK, or transport of a ligand by PcaK, signals a physically associated protein to initiate chemosensory signal transduction. This could be accomplished via a system homologous to the well-studied chemotaxis signaling system of E. coli and S. typhimurium. In these enteric bacteria, a ternary complex of an MCP, CheA, and CheW initiates signal transduction. This ternary complex allows CheA, the sensor kinase, to be autophosphorylated in response to ligand binding by an MCP. This results in the subsequent phosphorylation of CheY, which in turn binds to the flagellar motor to change its direction of rotation, effecting a chemotactic response (37). A cluster of general chemotaxis genes homologous to those of the enterics has been identified in P. putida (5). Homologs of MCP genes have not yet been identified in P. putida, but we expect that they exist since we know from physiological data that there are proteins in P. putida which are methylated in response to aromatic acid addition (11). It seems plausible that PcaK could interact with a physically associated MCP to initiate chemosensory signal transduction via a conformational change. Another possibility is that signal transduction can be initiated by an electrostatic charge, for example, proton or ion symport, that accompanies transport. PcaK is an aromatic acid/H+ symporter. It is known that a combination of conformational and electrostatic changes that occur in sensory rhodopsin in response to stimulating light are responsible for sensory signal transduction via a physically associated MCP in Halobacterium salinarium (35, 36). It is possible that an analogous situation occurs with PcaK.

A final possibility is that once 4-HBA is transported into the cell, it binds intracellularly to a soluble MCP or other protein to initiate signal transduction. However, due to the ability of aromatic acids to diffuse across bacterial membranes, enough 4-HBA is accumulated within the pcaK mutant to allow growth at wild-type rates under the conditions in which 4-HBA chemotaxis was measured (13). This finding indicates that simple accumulation of 4-HBA within the cell is not enough for 4-HBA chemotaxis to occur; PcaK must be present. The data indicating that PcaK is required for chemotaxis to benzoate also argue against an indirect role of PcaK in signal transduction.

Regardless of the mechanism involved, it is clear that P. putida uses a single protein to mediate the two processes of transport and chemotaxis. Physiologically, the combining of two such processes would be advantageous in that the protein that localizes cells to an environment rich in 4-HBA is also the protein that allows accumulation of 4-HBA within cells. Although PcaK is the first described MFS protein that acts in this way, it is doubtful, in view of the prevalence of MFS transporters, that it is unique. It will be interesting to see if other MFS transporters, particularly members of the aromatic acid/H+ symporter family, can function in chemotaxis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM56665 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dagley S. Biochemistry of aromatic hydrocarbon degradation in pseudomonads. In: Sokatch J R, editor. The biology of Pseudomonas. Vol. 10. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press, Inc.; 1986. pp. 527–556. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis R W, Botstein D, Roth J R. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski D R. Broad-host range DNA cloning system for gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7347–7351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ditty J L, Grimm A C, Harwood C S. Identification of a chemotaxis gene region from Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;159:267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ditty, J. L., and C. S. Harwood. Unpublished data.

- 7.Figurski D H, Helinski D R. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1648–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Costilow R N, Nester E W, Wood W A, Krieg N R, Phillips G B, editors. Manual of methods for general bacteriology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harayama S, Timmis K N. Catabolism of aromatic hydrocarbons by Pseudomonas. In: Hopwood D A, Chater K F, editors. Genetics of bacterial diversity. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harwood C S. A methyl-accepting protein is involved in benzoate taxis in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4603–4608. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.4603-4608.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harwood, C. S. Unpublished data.

- 13.Harwood C S, Nichols N N, Kim M-K, Ditty J L, Parales R E. Identification of the pcaRKF gene cluster from Pseudomonas putida: involvement in chemotaxis, biodegradation, and transport of 4-hydroxybenzoate. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6479–6488. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6479-6488.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harwood C S, Parales R E. The β-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:553–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harwood C S, Rivelli M, Ornston L N. Aromatic acids are chemoattractants for Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:622–628. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.2.622-628.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jessen-Marshall A E, Parker N J, Brooker R J. Suppressor analysis of mutations in the loop 2-3 motif of the lactose permease: evidence that glycine-64 is an important residue for conformational changes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2616–2622. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2616-2622.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jessen-Marshall A E, Paul N J, Brooker R J. The conserved motif, GXXX(D/E)(R/K)XG[X](R/K)(R/K), in hydrophilic loop 2/3 of the lactose permease. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16251–16257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.16251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones D T, Taylor W R, Thornton J M. A model recognition approach to the prediction of all-helical membrane protein structure and topology. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3038–3049. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaback H R. The lactose permease of Escherichia coli: a paradigm for membrane transport proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1101:210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keen N T, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad host range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lux R, Munasinghe V R N, Castellano F, Lengeler J W, Corrie J E T, Khan S. Elucidation of a PTS-carbohydrate chemotactic signal pathway in Escherichia coli using a time-resolved behavioral assay. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1133–1146. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marger M D, Saier M H., Jr A major superfamily of transmembrane facilitators that catalyze uniport, symport, and antiport. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:13–19. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90081-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michael S F. Mutagenesis by incorporation of a phosphorylated oligo during PCR amplification. BioTechniques. 1994;16:411–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nichols N N, Harwood C S. PcaK, a high-affinity permease for the aromatic compounds 4-hydroxybenzoate and protocatechuate from Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5056–5061. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5056-5061.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols N N, Harwood C S. Repression of 4-hydroxybenzoate transport and degradation by benzoate: a new layer of regulatory control in the Pseudomonas putida β-ketoadipate pathway. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7033–7040. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7033-7040.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ornston L N, Houghton J E, Neidle E L, Gregg L A. Subtle selection and novel mutation during evolutionary divergence of the β-ketoadipate pathway. In: Silver S, Chakrabarty A M, Iglewski B, Kaplan S, editors. Pseudomonas biology: biotransformations, pathogenesis, and evolving biotechnology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ornston L N, Parke D. Properties of an inducible uptake system for β-ketoadipate in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1976;125:475–488. doi: 10.1128/jb.125.2.475-488.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pao S S, Paulsen I T, Saier M H., Jr Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1–34. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.1-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pazdernik N J, Jessen-Marshall A E, Brooker R J. Role of conserved residues in hydrophilic loop 8-9 of the lactose permease. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:735–741. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.735-741.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Postma P W, Lengeler J W, Jacobson G R. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1149–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roepe P D, Consler T G, Menezes M E, Kaback H R. The Lac permease of Escherichia coli: site-directed mutagenesis studies on the mechanism of β-galactoside/H+ symport. Res Microbiol. 1990;141:290–308. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(90)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. BioTechnology. 1983;1:784–789. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spudich J L. Protein-protein interaction converts a proton pump into a sensory receptor. Cell. 1994;79:747–750. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spudich J L, Lanyi J K. Shuttling between two protein conformations: the common mechanism for sensory transduction and ion transport. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:452–457. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stock J B, Surette M G. Chemotaxis. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1103–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Meer J R, de Vos W M, Harayama S, Zehnder A J B. Molecular mechanisms of genetic adaptation to xenobiotic compounds. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:677–694. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.677-694.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamaguchi A, Kimura T, Someya Y, Sawai T. Metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli encoded by transposon Tn10: the structural resemblance and functional difference in the role of the duplicated sequence motif between the hydrophobic segments 2 and 3 and segments 8 and 9. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6496–6504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamaguchi A, Ono N, Akasaka T, Noumi T, Sawai T. Metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli encoded by transposon Tn10: the role of the conserved dipeptide, Ser65-Asp66, in tetracycline transport. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:15525–15530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi A, Someya Y, Sawai T. Metal-tetracycline/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli encoded by transposon Tn10: the role of a conserved sequence motif, GXXXXRXGRR, in a putative cytoplasmic loop between helices 2 and 3. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19155–19162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]