Abstract

Development of an efficient and eco-friendly technique to break tuber dormancy in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is highly demanded due to the production of two or more crops annually. Several physiological and hormonal changes have been found to be related to the breaking of tuber dormancy; however, their consistency with genotypes and different protocols have not been well clarified. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of four dormancy-breaking methods, that is, plant growth regulator (PGR) dipping in 30, 60, or 90 mgL−1 benzyl amino purine (BAP) and 10, 20, or 30 mgL−1 gibberellic acids (GA3) alone and in the combination of optimized concentrations; electric current application at 20, 40, 60, or 80 Vs; cold pre-treatment at 2, 4, or 6 °C; irradiation at 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, or 3.5 kGy. In addition, changes in endogenous levels of abscisic acid (ABA), zeatin (ZT), and gibberellin A1 (GA1) in six potato genotypes after subjecting to these methods were investigated. Overall, the highest effective method for dormancy duration was the PGR application which shortened the duration by 18 days, followed by electric current (13 days), cold pre-treatment (9 days), and then irradiation (7 days). The solution of 60 mgL−1 BAP significantly reduced the dormancy duration in all genotypes but did not have a significant effect on the sprout length. While 20 mgL−1 GA3 produced maximum sprout length with a non-significant effect on dormancy duration. The genotype × PGR interaction for dormancy duration was more pronounced in short- and medium-term dormancy genotypes than in long-term dormancy genotypes. The genotypes displayed a significant positive correlation between dormancy duration and ABA levels but exhibited a negative correlation between dormancy duration and ZT as well as GA1 levels. From the first to the third week of storage, ABA was decreased in tubers while, however, ZT and GA1 were increased. The obtained results could be useful for the postharvest storage of potato tuber and the related field of physiological investigation in future.

Keywords: plant growth regulators, dormancy, Solanum tuberosum L., sprouting, zeatin, g-radiation, cold-treatment, electric current

Introduction

Potato is the world's third most popular vegetable in terms of consumption and fourth in terms of production. It is grown on 0.19 million hectares in Pakistan, with an estimated annual production of 4.6 million tons, at an average of 24.2 tons per hectare. Pakistan ranks 19th in terms of production and 12th for export quantity (Bashir et al., 2021). Potato is grown round the year in Pakistan. Autumn (mid-September to January) is the main crop, accounting for 80–85% of total yearly production, with spring (January–May) and summer (April to September) harvests accounting for 10–15% and 1–2%, respectively (Khalid et al., 2020). Its tubers go through a period of dormancy after harvest and are unable to sprout. Thus, the tuber dormancy prevents seed potatoes harvested under the spring and summer crops from being used for subsequent summer and autumn crops (Khan, 2004). Similarly, the autumn-produced seed could also not be used for subsequent spring and summer crops (Haider et al., 2019). The economic dormancy period of seed potatoes varies by country and cropping pattern. With multiple cropping systems in Pakistan, the interval between harvesting and planting consecutive crops is quite short (less than a month). Due to the unavailability of short-term dormancy genotypes, the growers have adapted the autumn-to-autumn cycle by storing the produce of the autumn crop from medium- and long-term dormancy genotypes for the following autumn crop, resulting in seed quality decline (Khan, 2004; Haider et al., 2019).

The dormancy is governed by endogenous levels of abscisic acid (ABA), zeatin (ZT), and gibberellic acid (GA3), which are produced through the mevalonic acid pathway (Vivanco and Flores, 2000; Davies, 2004). Their interaction, therefore, has a significant impact on tuber dormancy and sprouting regulation. ABA contents during dormancy are the result of a synthesis-metabolism balance that favors catabolism when dormancy ends (Destefano-Beltrán et al., 2006). The level of ABA is highest in freshly harvested tubers and decreases during postharvest storage. However, there is no specific ABA level below which sprouting begins (Claassens and Vreugdenhil, 2000). Cytokinin levels are low during dormancy and subsequently rise at the initiation of sprouting. The increase in cytokinin content is accompanied by a decrease in ABA during dormancy break (Bryan, 1989). Endogenous GA1 was also shown to be rather high just after harvest, decreased during storage, and then increased to its greatest level during vigorous sprout growth (Suttle et al., 2012).

Different approaches have been tested to overcome tuber dormancy in potatoes depending on germplasm and the resources available (Bryan, 1989). Common methods for breaking tuber dormancy include cold shock plus heat (Deligios et al., 2019) and the application of various chemicals such as Rindite (Kim et al., 1999), bromoethane (Alexopoulos et al., 2009), carbon disulfide (Salimi et al., 2010), and thiourea (Mani et al., 2013). They are, however, either ineffective or hazardous to humans and the environment. The use of growth promoters in low quantities is reported to stimulate potato tuber sprouting (Carrera et al., 2000; Alexopoulos et al., 2008). Some growth promoters, such as cytokinin and GA, are also used for bud break and sprouting of seed potatoes and are safe for human use (Wurr, 1978). Previous studies suggest that dormancy break coincides with an abrupt increase in the concentration of ZT and GA1 and a decrease in ABA in the buds and adjacent tissues (Suttle, 2004; Hartmann et al., 2011).

The phenomenon of tuber dormancy breakage in potatoes via numerous approaches and consequent physiological changes (changes in oxidative patterns, sugar levels, and protein contents) has been well studied; however, little is known about changes occurring in endogenous levels of hormones in response to individual and combined application of cytokinin, that is, BAP, and gibberellin, that is, GA3, electric current, cold pre-treatment, and irradiation to the tubers of six potato genotypes. The outcomes of this study will provide researchers with new insights into the hormonal regulation of potato tuber dormancy. This study aimed to test the impact of various dormancy-breaking techniques viz. plant growth regulators, electric current, cold pre-treatment, and irradiation on tuber dormancy duration of six potato genotypes and observe the endogenous hormonal changes in the tuber.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Six genotypes of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) out of 22 including an equal number of white (FD51-5, Sante, and FD69-1) and red skin genotypes (PRI Red, FD73-49, and FD8-1) were imported from Potato Research Institute (PRI), Sahiwal, Pakistan (Haider et al., 2019). Healthy tubers were selected based on their dormancy behavior excluding the damaged, diseased, or deformed types.

Application of dormancy-breaking methods

During March 2018, tubers of six potato genotypes were collected after 10 days of harvesting from Potato Research Institute (PRI), Sahiwal. Tubers were dipped in 30, 60, or 90 mgL−1 solution of benzylaminopurine (BAP) and 10, 20, or 30 mgL−1 solution of gibberellic acid (GA3) for 24 h to optimize their concentrations, and for the evaluation of their combined effect on breaking dormancy, the tubers were dipped in each solution for 12 h. For control, tubers were dipped in distilled water. Each treatment was replicated four times, and 30 tubers were used in each replicate, since potato skin is almost impermeable to chemicals (Haider et al., 2019); therefore, parenchyma tissues were exposed to different solutions of PGRs by giving a small cut (15 mm length ×10 mm depth). The tubers, after treatment, were stored under ambient conditions (23.8 ± 1.0°C) till sprouting.

Moreover, tubers were packed in corrugated cardboard boxes and taken to the Post-harvest Research Center, Ayyub Agricultural Research Institute, for cold pre-treatment. The tubers were stored for four days at different storage regimes, that is, control, 2°C, 4°C, and 6°C. After cold storage, they were kept at ambient temperature to study sprouting and biochemical characteristics. The temperature and humidity were recorded during ambient storage.

Electric current (20, 40, 60, or 80 V) was applied to tubers for 24 h by penetrating needles (of handmade electric stimulator) 15 mm inside the flesh at the apical and stem ends of the tuber. For control, tubers were injected with needles and an electric current was applied without any voltage. Once treated, the tubers were stored under ambient conditions to calculate different parameters. For the assessment of the influence of gamma rays on tuber hormonal contents, a 137Cs source with radiation power of 1 kGy/ 1.5 h was used, at the Nuclear Institute of Agriculture and Biology, Faisalabad. The tubers were exposed to doses of 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, and 3.5 kGy and stored afterward at ambient temperature for hormonal analysis.

All the above trials were laid out according to completely randomized design (CRD) under factorial settings.

Data collection

Determination of dormancy duration and sprout length

Data on dormancy duration and sprout length were collected from six tubers in each replication on a daily basis. The dormancy was considered to have been broken when sprouts reached 2 mm in length (Van Ittersum and Scholte, 1993; Pande et al., 2007). The length of the sprout was measured using a measuring tape.

Determination of endogenous plant growth regulators in tubers

Endogenous plant growth regulators (PGRs) in tubers were analyzed by using the method described by Tang et al. (2011) at one- and three-week storage after treatment of tubers using a Varian ProSTAR 240 high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), Walnut Creek, CA, USA, equipped with a Milli-Q ultrapure water purification system. Standards of abscisic acid (ABA) and zeatin (ZT) were obtained from Sigma Chemical, [2H2]-GA1 d2-GA1 (purity > 90%) was purchased from OlChemim Ltd (Olomouc, Czech Republic), chromatographic purity methanol was from Fisher Chemical, ethanoic acid was analytical grade, and the water used in the experiment was ultrapure.

A thin disk of parenchyma (1 g of tissue) was excised from each tuber, frozen and ground in liquid nitrogen, homogenized, and then extracted overnight with 30 ml of 80% cold aqueous methanol (<0 °C) in darkness at 4°C. The extracts were purified by a protocol adapted by Bensen et al. (1990). After filtration, the extracts were reduced to the aqueous phase. Each extract obtained was then centrifuged at 5,000 rpm and 4°C for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. Then, fresh cold methanol was poured onto the remnant and extracted three times as stated above. The total methanolic extract was dried in a rotary evaporator (Laborata 4002, Heidolph, Nürnberg, Germany) and dissolved in 10 ml methanol. The extracts were fractionated using a C-18 chromatographic column (150 ×4.6 mm, 5 μm) and a mixture of acetonitrile (Solvent A)/1 percent (v/v) acetic acid containing 0.5 ml liter−1 triethylamine (Solvent B). The following were the solvent gradient conditions: initial: 5% A, hold for 10 min, a linear gradient to 30% A in 15 min, hold for 35 min, a linear gradient to 100% A, hold for 3 min, return to initial conditions in 5 min. The column temperature was 35°C, flow rate of 1 ml min−1, and UV detection wavelength of 254 nm. ABA, ZT, and GA1 were measured by injection of the extract into a reverse phase HPLC. Determinations of ABA, ZT, and GA1 were performed on the same sample and expressed in ng g−1 FW.

Statistical analyses

All data were subjected to a three-way analysis of variance (treatment × genotype × storage period) under three factors factorial completely randomized design (CRD) using Statistix9® software (Analytical Software, Tallahassee, USA), and the results are interpreted as the relative contribution of treatment, genotype, storage period, and their interactions by determining the percentage of total variance from the corresponding sum of squares (SS) as performed by Kyriacou et al. (2021). The least significant difference (LSD) test was used to compute mean comparisons and main effects for treatment, genotype, storage period, and their interactions at P ≤ 0.05. The SPSS 16.0 program was used to conduct Pearson's correlation analysis (USA). The correlation was analyzed by the general linear model procedure in SAS, version 9.2 (Cary, NC).

Results

Screening trial

There were significant differences in the duration of postharvest dormancy among the original 22 genotypes evaluated in the screening trial (Haider et al., 2019). From these, three distinct groups were chosen based on their tuber sprouting behavior. Short-term dormancy genotypes included FD51-5 and PRI Red; genotypes with medium-term dormancy included Sante and FD73-49, while FD69-1 and FD8-1 were classified as long-term dormancy genotypes. Each group contained white and red skin genotypes as both colors of tubers are equally liked and consumed by the consumers in the country (Pakistan).

Individual application of PGRs and their optimization

Effect on tuber dormancy and sprout length

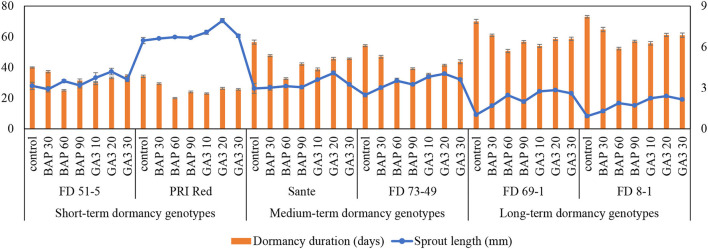

PGRs, genotypes, and their interactive effect (PGRs × genotypes) were significant (P ≤ 0.05) for dormancy duration and sprout length (Table 1A). Among PGRs, 60 mgL−1 was the most effective dose of BAP in shortening the dormancy duration and 20 mgL−1 of GA3 in increasing the sprout length, in all genotypes. The interactive effect was more pronounced in the short-term (PRI Red and FD51-5) and medium-term (FD73-49 and Sante) dormancy genotypes and less pronounced in the long-term (FD69-1 and FD8-1) dormancy genotypes (Figure 1).

Table 1A.

Mean comparison of dormancy duration and sprout length of potato tubers influenced by PGRs and genotypes during the year 2018.

| Factors | Dormancy duration (days) | Sprout length (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (T) | Control | 53.5a | 2.73f |

| 30 mgL−1 BAP | 46.7b | 3.09e | |

| 60 mgL−1 BAP | 34.3f | 3.47c | |

| 90 mgL−1 BAP | 40.6d | 3.21d | |

| 10 mgL−1 GA3 | 38.2e | 3.77b | |

| 20 mgL−1 GA3 | 43.1c | 4.15a | |

| 30 mgL−1 GA3 | 43.9c | 3.57c | |

| LSD T (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.95 | 0.141 | |

| Genotype (G) | FD51-5 | 32.1e | 3.35b |

| PRI Red | 25.0f | 6.80a | |

| Sante | 43.2c | 3.20c | |

| FD73-49 | 41.0d | 3.29bc | |

| FD69-1 | 57.5b | 2.10d | |

| FD8-1 | 59.7a | 1.70e | |

| LSD G (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.88 | 0.130 | |

| LSD T × G (P ≤ 0.05) | 2.386 | 0.370 |

BAP, benzylaminopurine; GA3, gibberellic acid.

Treatment means followed by the same letter are not significantly different.

LSD, least significant difference.

Figure 1.

Mean comparison of dormancy duration (days) and sprout length (mm) in potato tubers under genotype × PGR interactive effect. Vertical error bars represent standard error of means.

Effect on tuber endogenous plant growth regulators

Abscisic acid (ABA), zeatin (ZT), and gibberellin A1 (GA1) in experimental tubers were significantly influenced by the dormancy-breaking methods, genotypes, and storage periods and the two-way interaction of genotype × storage period. The rest of the interactions were non-significant (Table 1B). All the treated tubers resulted in significantly lower ABA and higher ZT, and GA1 compared to the control. There was a significant positive correlation (r ≥ 0.99) between dormancy and ABA levels. The short dormancy genotypes (FD51-5 and PRI Red) had significantly lower levels of ABA than the moderate (Sante and FD73-49) and long-term dormancy genotypes (Sante and FD73-49), and the moderate dormancy genotypes had lower levels of ABA than the long-dormancy genotypes. There was a significant negative correlation between dormancy and ZT levels (r ≥ −0.94) and dormancy and GA1 levels (r ≥ −0.94). The short-term dormancy genotypes had significantly higher levels of ZT and GA1 than those of the moderate- and long-dormancy genotypes, and the medium-term dormancy genotypes had significantly higher levels of ZT and GA1 than the long-term dormancy genotypes.

Table 1B.

Periodic changes in the contents of ABA, ZT, and GA1 in experimental tubers of six potato genotypes dipped in PGRs during 2018.

| Factors | ABA | ZT | GA1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ng g−1 FW | ng g−1 FW | ng g−1 FW | ||

| Treatment (T) | Control | 98.2a | 16.1c | 0.52c |

| 30 mgL−1 BAP | 97.4a | 16.2c | 0.53bc | |

| 60 mgL−1 BAP | 90.0d | 16.9a | 0.58a | |

| 90 mgL−1 BAP | 93.9c | 16.4b | 0.55ab | |

| 10 mgL−1 GA3 | 95.1bc | 16.3bc | 0.56ab | |

| 20 mgL−1 GA3 | 95.2b | 16.3bc | 0.58a | |

| 30 mgL−1 GA3 | 95.5b | 16.2bc | 0.55b | |

| LSD T (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.27 | 0.22 | 0.023 | |

| Genotype (G) | FD51-5 | 62.0e | 19.1b | 0.70b |

| PRI red | 54.1f | 22.9a | 0.84a | |

| Sante | 100.7c | 14.3d | 0.47c | |

| FD73-49 | 95.1d | 17.0c | 0.45cd | |

| FD69-1 | 122.6b | 12.7e | 0.44d | |

| FD8-1 | 135.9a | 12.2f | 0.39e | |

| LSD G (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.18 | 0.20 | 0.021 | |

| Storage period (SP) | 1 Week | 125.7a | 9.7a | 0.59a |

| 3 Week | 64.4b | 23.0b | 0.51b | |

| LSD SP (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.68 | 0.12 | 0.012 | |

| LSD T × G (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | |

| LSD T × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | |

| LSD G × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.67 | 0.29 | 0.030 | |

| LSD T × G × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS |

NS, non-significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Treatment means sharing same letter differ non-significantly.

ABA, abscisic acid; GA1, gibberellin A1; BAP, benzylaminopurine; GA3, gibberellic acid; LSD, least significant difference.

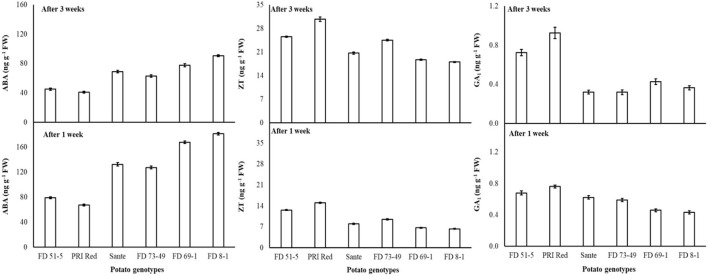

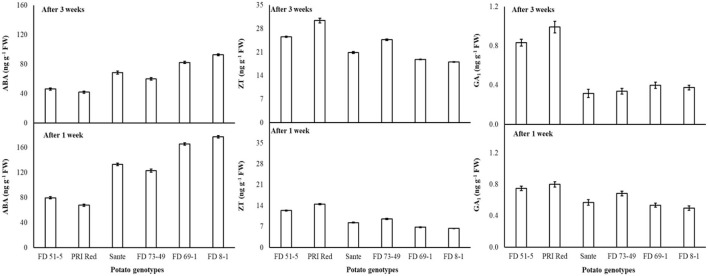

Under the genotype × storage period interaction, ABA decreased more rapidly in the long-dormancy genotypes than in the moderate or short dormancy genotypes (Figure 2). The rates of increase in ZT between week one and week three were similar in four of the genotypes (FD51-5, PRI Red, Sante, and FD73-49) (Figure 2). GA1 increased between week one and week three in the short dormancy genotypes but decreased in the moderate- to long-dormancy genotypes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Change in ABA, ZT, and GA1 levels in tuber during storage period (3 weeks) following treatment with alone benzylaminopurine and gibberellic acid. Vertical error bars represent standard error of means (n: 4).

Individual and combined application of optimized doses of PGRs

Effect on tuber dormancy and sprout length

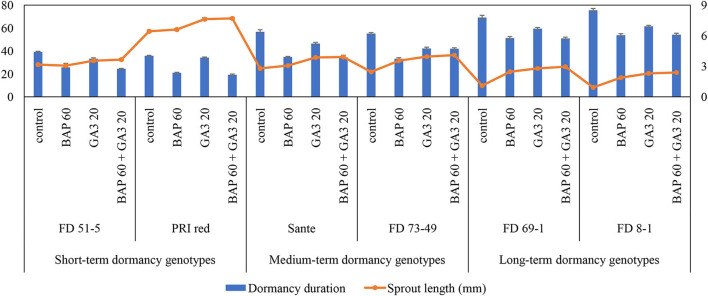

The individual effects of PGRs and genotypes and their interaction were significant (P ≤ 0.05) for shortening the dormancy duration (Table 2A). Among PGRs, 60 mgL−1 BAP and its combination with 20 mgL−1 GA3 effectively reduced the dormancy duration by 18.6 and 17.7 days and increased the sprout length by 1.2 and 1.5 times, respectively (Table 2A). “PRI Red” displayed the shortest (27.5 days) and “FD8-1” displayed the longest dormancy duration (Table 2A). The interaction was more pronounced in the short- (PRI Red and FD51-5) and medium-term (FD73-49 and Sante) dormancy genotypes and less pronounced in the long-term (FD8-1 and FD69-1) dormancy genotypes (Figure 3).

Table 2A.

Mean comparison of dormancy duration and sprout length of potato tubers dipped in optimized doses of PGRs and genotypes during 2019.

| Factors | Dormancy duration (days) | Sprout length (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (T) | Control | 55.2a | 2.81c |

| 60 mgL−1 BAP | 36.6c | 3.43b | |

| 20 mgL−1 GA3 | 46.2b | 4.01a | |

| 60 mgL−1 BAP + 20 mgL−1 GA3 | 37.5c | 4.12a | |

| LSD T (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.18 | 0.142 | |

| Genotype (G) | FD51-5 | 30.6d | 3.35b |

| PRI Red | 27.5e | 7.09a | |

| Sante | 43.1c | 3.41b | |

| FD73-49 | 43.1c | 3.51b | |

| FD69-1 | 57.7b | 2.33c | |

| FD8-1 | 61.2a | 1.87d | |

| LSD G (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.45 | 0.174 | |

| LSD T × G (P ≤ 0.05) | 2.901 | 0.348 |

BAP, benzylaminopurine; GA3, gibberellic acid.

Treatment means followed by the same letter are not significantly different.

BAP, benzylaminopurine; GA3, gibberellic acid; LSD, least significant difference.

Figure 3.

Mean comparison of dormancy duration (days) and sprout length (mm) in potato tubers under genotype × PGR interactive effect. Vertical error bars represent standard error of means.

Effect on tuber endogenous plant growth regulators

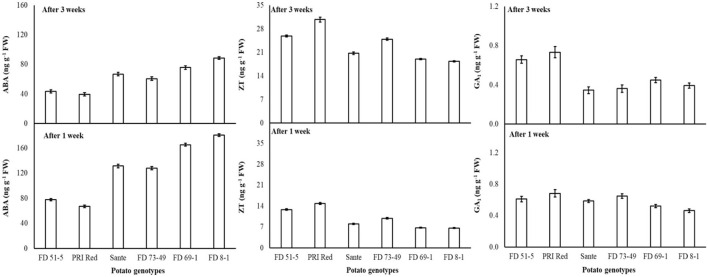

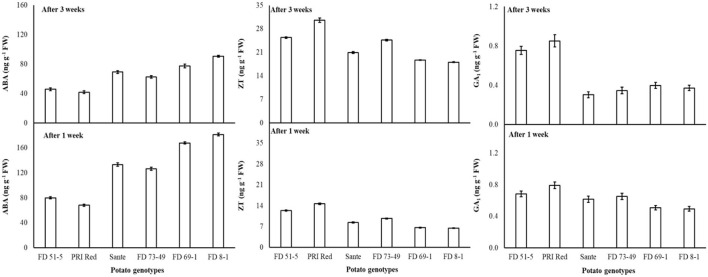

The lowest ABA (89.9 ng g−1 FW) and highest ZT (17.0 ng g−1 FW) and GA1 (0.53 ng g−1 FW) levels were found with a combined application of 60 mgL−1 of BAP and 20 mgL−1 GA3. The maximum ABA was observed in FD8-1, while the minimum was observed in PRI Red (Table 2B). Levels of ABA (125.7ng g−1 FW) and GA1 (0.58 ng g−1 FW) at week one were significantly higher than ABA (64.4ng g−1 FW) and GA1 (0.49 ng g−1 FW) at week three (Table 2B). ZT was significantly lower in week one (9.7ng g−1 FW) than in week three (23.0ng g−1 FW) (Table 2B). A significant positive correlation (r = 0.99) was observed in genotypes between dormancy and ABA levels. The short-term dormancy genotypes (PRI Red and FD51-5) had significantly lower levels of ABA than the medium-term (FD73-49 and Sante) and long-term dormancy genotypes (FD8-1 and FD69-1), and the medium-term dormancy genotypes had relatively lower levels of ABA than the long-term dormancy genotypes. There was a significant negative correlation between dormancy and ZT levels (r ≥ −0.94) and dormancy and GA1 levels (r ≥ −0.94). The rates of increase in ZT between week 1 and week 3 were greater in genotypes PRI Red and FD73-49 (Figure 4). However, GA1 increased during the storage time in the short-term dormancy genotypes but decreased in the medium- to long-term dormancy genotypes (Figure 4).

Table 2B.

Periodic changes in the contents of ABA, ZT, and GA1 in experimental tubers of six potato genotypes dipped in optimized doses of PGRs during 2019.

| Factors | ABA | ZT | GA1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ng g−1 FW | ng g−1 FW | ng g−1 FW | ||

| Treatment (T) | Control | 98.5a | 16.1c | 0.49c |

| 60 mgL−1 BAP | 91.1c | 16.8b | 0.57a | |

| 20 mgL−1 GA3 | 95.2b | 16.3c | 0.53b | |

| 60 mgL−1 BAP + 20 mgL−1 GA3 | 89.9c | 17.0a | 0.57a | |

| LSD T (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.25 | 0.22 | 0.026 | |

| Genotype (G) | FD51-5 | 60.4e | 19.4b | 0.63b |

| PRI red | 53.3f | 22.8a | 0.71a | |

| Sante | 99.0c | 14.4d | 0.46d | |

| FD73-49 | 94.3d | 17.4c | 0.51c | |

| FD69-1 | 120.5b | 12.8e | 0.48cd | |

| FD8-1 | 134.6a | 12.5f | 0.43e | |

| LSD G (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.53 | 0.27 | 0.032 | |

| Storage period (SP) | 1 Week | 124.9a | 9.8a | 0.58a |

| 3 Week | 62.3b | 23.3b | 0.49b | |

| LSD SP (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.89 | 0.16 | 0.019 | |

| LSD T × G (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | |

| LSD T × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | |

| LSD G × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | 2.17 | 0.39 | 0.046 | |

| LSD T × G × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS |

NS, non-significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Treatment means sharing same letter differ non-significantly.

ABA, abscisic acid; GA1, gibberellin A1; BAP, benzylaminopurine; GA3, gibberellic acid; LSD, least significant difference.

Figure 4.

Change in ABA, ZT, and GA1 levels in tuber during storage period (3 weeks) following treatment with benzylaminopurine and gibberellic acid together. Vertical error bars represent standard error of means (n: 4).

Electric shock of tubers

Effects on tuber dormancy and sprout length

The effect of electric current and genotype was significant (P ≤ 0.05) for dormancy duration and sprout length in tubers during both years (Table 3A), but their interactive effect was found significant only for the year 2019 (Table 3B). In both years, the shortest dormancy duration was observed in tubers treated with the electric current at 80 V which was significantly different from the control. PRI Red showed the shortest dormancy duration.

Table 3A.

Mean comparison of dormancy duration and sprout length of six genotypes potato tubers during 2018–2019 underwent direct electric current.

| Factors | Dormancy duration (days) | Sprout length (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| Electric current (Ec) | 0-V | 54.0a | 53.7a | 2.75b | 2.70c |

| 20-V | 49.7b | 49.6b | 2.79b | 2.78bc | |

| 40-V | 48.1c | 48.1c | 2.79b | 2.85bc | |

| 60-V | 46.4d | 46.1d | 2.84b | 2.90b | |

| 80-V | 41.0e | 40.6e | 3.52a | 3.51a | |

| LSD T (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.36 | 1.35 | 0.179 | 0.156 | |

| Genotype (G) | FD51-5 | 36.9d | 36.5d | 3.19b | 3.19b |

| PRI Red | 30.7e | 31.0e | 6.46a | 6.53a | |

| Sante | 48.0c | 48.6c | 2.98c | 2.93c | |

| FD73-49 | 48.2c | 47.8c | 2.64d | 2.66d | |

| FD69-1 | 60.2b | 59.3b | 1.26e | 1.30e | |

| FD8-1 | 63.2a | 62.7a | 1.09e | 1.08f | |

| LSD G (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.50 | 1.47 | 0.196 | 0.171 | |

| LSD Ec × G (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | 3.308 | NS | NS | |

NS, non-significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Treatment means followed by the same letter are not significantly different.

LSD, least significant difference.

Table 3B.

Mean comparison of dormancy duration of potato in 2019 under direct electric current and genotype interactive effects.

| Treatments (T) | Genotypes (G) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FD51-5 | PRI Red | Sante | FD73-49 | FD69-1 | FD8-1 | |

| 0-V | 41.0k | 33.7mn | 55.2ef | 53.7fg | 68.7a | 69.7a |

| 20-V | 38.2kl | 32.2no | 50.5ghi | 51.2gh | 62.0bc | 63.5b |

| 40-V | 38.2kl | 31.5no | 49.0hij | 48.5hij | 58.5de | 63.2b |

| 60-V | 35.7lm | 31.5no | 47.7ij | 46.0j | 56.7def | 59.2cd |

| 80-V | 29.2op | 26.2p | 40.5k | 39.5k | 50.7ghi | 57.7de |

LSD Ec × G (P ≤ 0.05) = 3.308.

Treatment means followed by the same letter are not significantly different.

LSD, least significant difference.

Effect on tuber endogenous plant growth regulators

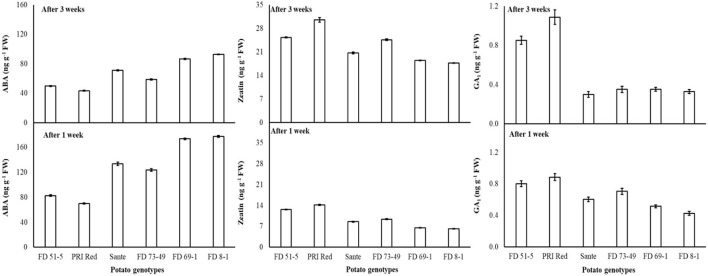

The contents of ABA, ZT, and GA1 for electric current, genotypes, and storage periods are given in Table 3C. ABA decreased with increasing voltages. There were no significant differences for ZT at most voltages but were significantly higher at the 60 V and 80 V. GA1 also increased with increasing voltage. ABA (126.1 ng g−1 FW) and GA1 (0.62 ng g−1 FW) were significantly higher in week one than ABA (64.7 ng g−1 FW) and GA1 (0.51 ng g−1 FW) in week three. ZT was significantly lower in week one (9.7 ng g−1 FW) than in week three (23.0 ng g−1 FW). There was a significant positive correlation (r = 0.99) between dormancy and ABA levels in genotypes. The short-term dormancy genotypes had significantly lower levels of ABA than the moderate- and long-term dormancy genotypes, whereas a negative correlation was observed between dormancy and ZT (r = −0.96) and GA1 (r = −0.92). The genotypes PRI Red and FD51-5 had higher levels of GA1 than FD73-49 and Sante which had higher levels of GA1 than FD8-1 and FD69-1 (Figure 5).

Table 3C.

Periodic changes in the contents of ABA, ZT, and GA1 in experimental tubers of six potato genotypes following treatment with direct electric current during the year 2018–2019.

| Factors | ABA | ZT | GA1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ng g−1 FW | ng g−1 FW | ng g−1 FW | ||

| Electric current (Ec) | 0-V | 98.9a | 16.2c | 0.51c |

| 20-V | 97.8a | 16.2c | 0.53c | |

| 40-V | 95.8b | 16.2c | 0.56b | |

| 60-V | 94.0c | 16.5b | 0.58b | |

| 80-V | 90.4d | 16.8a | 0.64a | |

| LSD T (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.21 | 0.21 | 0.026 | |

| Genotype (G) | FD51-5 | 62.9e | 18.9b | 0.72b |

| PRI red | 55.1f | 22.6a | 0.82a | |

| Sante | 101.2c | 14.6d | 0.46d | |

| FD73-49 | 94.6d | 17.2c | 0.50c | |

| FD69-1 | 122.5b | 12.7e | 0.45d | |

| FD8-1 | 136.0a | 12.3f | 0.43d | |

| LSD G (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.32 | 0.23 | 0.029 | |

| Storage period (SP) | 1 Week | 126.1a | 9.7b | 0.62a |

| 3 Week | 64.7b | 23.0a | 0.51b | |

| LSD SP (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.76 | 0.13 | 0.017 | |

| LSD Ec × G (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | |

| LSD Ec × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | |

| LSD G × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.87 | 0.32 | 0.041 | |

| LSD Ec × G × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS |

NS, non-significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Treatment means sharing same letter differ non-significantly.

LSD, least significant difference.

Figure 5.

Change in ABA, ZT, and GA1 levels in tuber during storage period (3 weeks) following treatment with low temperature under cold storage. Vertical error bars represent standard error of means (n: 4).

Cold pre-treatment of tubers

Effect on tuber dormancy and sprout length

The dormancy duration and sprout length were significantly (P < 0.05) influenced by the storage temperatures and the genotypes in both years (Table 4A). The lowest dormancy duration was recorded in tubers stored at 2°C in both years, and the longest dormancy duration was found in tubers of control. The shortest dormancy duration and highest sprout length were recorded in “PRI Red” in both years. The interactive effect of storage temperature and genotype did not have a significant effect on the dormancy duration but on the sprout length (Table 4A).

Table 4A.

Mean comparison of dormancy duration and sprout length of six potato genotypes tubers during 2018–2019 underwent low-temperature cold storage.

| Factors | Dormancy duration (days) | Sprout length (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| Temperature (T) | Control | 54.7a | 53.7a | 2.72c | 2.76c |

| 2°C | 45.5d | 44.7d | 3.38a | 3.36a | |

| 4°C | 48.5c | 48.3c | 2.95b | 2.98b | |

| 6°C | 51.0b | 50.9b | 2.81bc | 2.82bc | |

| LSD T (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.16 | 1.34 | 0.196 | 0.164 | |

| Genotype (G) | FD51-5 | 38.1c | 37.2d | 3.14b | 3.164b |

| PRI Red | 32.8d | 32.4e | 6.39a | 6.34a | |

| Sante | 50.6b | 48.6c | 2.99b | 3.00b | |

| FD73-49 | 49.2b | 47.8c | 2.66c | 2.70c | |

| FD69-1 | 63.9a | 64.0b | 1.34d | 1.41d | |

| FD8-1 | 64.8a | 66.6a | 1.26d | 1.26d | |

| LSD G (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.42 | 1.64 | 0.240 | 0.201 | |

| LSD T × G (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

NS, non-significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Treatment means followed by the same letter are not significantly different.

LSD, least significant difference.

Effect on tuber endogenous plant growth regulators

ABA levels decreased with the lowest temperature (2°C) treatment. There were no significant differences for ZT at most storage temperatures, with the exception that ZT was significantly higher at the lowest temperature. GA1 also increased with the lowermost temperature. FD8-1 had the highest ABA content (135.0 ng g−1 FW) and the lowest ZT (12.0 ng g−1 FW) and GA1 (0.43 ng g−1 FW) of the genotypes studied, while PRI Red had the lowest ABA (54.9 ng g−1 FW) and the highest ZT (22.5 ng g−1 FW) and GA1 (0.89 ng g−1 FW) contents (Table 4B). ABA (124.4 ng g−1 FW) and GA1 (0.64 ng g−1 FW) were significantly higher in week one than ABA (65.2 ng g−1 FW) and GA1 (0.54 ng g−1 FW) contents in week three (Figure 6). On the contrary, ZT was significantly lower in week one (9.7 ng g−1 FW) than in week three (23.0 ng g−1 FW) (Figure 6).

Table 4B.

Periodic changes in the contents of ABA, ZT, and GA1 in experimental tubers of six potato genotypes following treatment with low-temperature cold storage during 2018–2019.

| Factors | ABA | ZT | GA1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ng g−1 FW | ng g−1 FW | ng g−1 FW | ||

| Temperature (T) | Control | 97.9a | 16.1b | 0.54d |

| 2°C | 91.2d | 16.6a | 0.65a | |

| 4°C | 93.8c | 16.4b | 0.60b | |

| 6°C | 96.2b | 16.2b | 0.57c | |

| LSD T (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.97 | 0.21 | 0.025 | |

| Genotype (G) | FD51-5 | 62.9e | 18.9b | 0.79 |

| PRI red | 54.9f | 22.5a | 0.89 | |

| Sante | 100.8c | 14.6d | 0.44 | |

| FD73-49 | 91.4d | 17.1c | 0.51 | |

| FD69-1 | 123.9b | 12.8e | 0.47 | |

| FD8-1 | 135.0a | 12.2f | 0.43 | |

| LSD G (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.18 | 0.26 | 0.030 | |

| Storage period (SP) | 1 Week | 124.4a | 9.7b | 0.64 |

| 3 Week | 65.2b | 23.0a | 0.54 | |

| LSD SP (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.68 | 0.15 | 0.017 | |

| LSD T × G (P ≤ 0.05) | 2.368 | NS | NS | |

| LSD T × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | |

| LSD G × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.67 | 0.37 | 0.043 | |

| LSD T × G × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS |

NS, non-significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Treatment means sharing same letter differ non-significantly.

LSD, least significant difference.

Figure 6.

Change in ABA, ZT, and GA1 levels in tuber during storage period (3 weeks) following treatment with electric current. Vertical error bars represent standard error of means (n: 4).

Irradiation of tubers

Effect on tuber dormancy and sprout length

γ-radiation significantly influenced the dormancy duration of tubers of different potato genotypes in both years (Table 5A). However, the interactive effect of irradiation dose × genotype did not significantly alter the dormancy duration. The lowest dormancy duration in 2018 (48.4 days) and 2019 (48.9 days) was recorded in the tubers treated with the highest dose of radiation (3.5 kGy) compared to the highest dormancy duration in 2018 (55.9 days) and 2019 (55.5 days) was found in the tubers of control. Among genotypes, PRI Red showed the shortest dormancy duration during both years 2018 (34.8 days) and 2019 (35.9 days), and FD8-1 showed the longest in both 2018 (68.9 days) and 2019 (68.7 days).

Table 5A.

Mean comparison of dormancy duration and sprout length of potato tubers for two years (2018–2019) under γ-irradiation doses and genotype main effects.

| Factors | 2018 | 2019 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dormancy duration | Sprout length | Dormancy duration | Sprout length | ||

| (Days) | (mm) | (Days) | (mm) | ||

| Irradiation dose (ID) | Control | 55.9a | 2.8d | 55.46a | 2.80c |

| 1.0 kGy | 55.0ab | 2.8cd | 55.29a | 2.84c | |

| 1.5 kGy | 54.3b | 2.8cd | 54.33ab | 2.86c | |

| 2.0 kGy | 53.8bc | 2.8cd | 53.92bc | 2.87bc | |

| 2.5 kGy | 52.7c | 2.9bc | 52.88cd | 2.92bc | |

| 3.0 kGy | 51.5d | 3.0b | 52.00d | 3.01b | |

| 3.5 kGy | 48.3e | 3.2a | 48.88e | 3.23a | |

| LSD ID (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.15 | 0.14 | 1.219 | 0.143 | |

| Genotypes (G) | FD51-5 | 40.4e | 3.2b | 38.07d | 3.19b |

| PRI Red | 34.8f | 6.7a | 35.96e | 6.61a | |

| Sante | 54.7c | 2.9c | 55.07b | 2.89c | |

| FD73-49 | 52.3d | 2.6d | 52.72c | 2.63d | |

| FD69-1 | 67.5b | 1.2e | 69.00a | 1.23e | |

| FD8-1 | 68.9a | 1.0e | 68.68a | 1.054f | |

| LSD G (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.06 | 0.13 | 1.128 | 0.132 | |

| LSD ID × G (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

NS, non-significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Treatment means followed by the same letter are not significantly different.

LSD, least significant difference.

Effect on tuber endogenous plant growth regulators

The concentration of ABA decreased with increasing radiation dosage (Table 5B). There were no significant differences in ZT contents at most dosage levels, with the exception that ZT was significantly higher at the highest dosage than at the other six lower doses (Table 5B). GA1 increased with increasing dosage. In general, GA1 was significantly higher when differences in dosage were greater than 1.0–1.5 KGy (Table 5B). ABA and GA1 decreased from week one to week three, while ZT increased (Table 5B). There was a significant positive correlation (r = 0.99) between dormancy and ABA levels and negative correlation (r = −0.94) between dormancy and ZT (-0.97) and GA1 (-0.94) levels. ABA decreased more rapidly in the long-dormancy genotypes than in the moderate or short dormancy genotypes, while ZT increased between week one and week three (Figure 7). The rate of increase was prominent in PRI Red and FD73-49 (Figure 7). GA1 increased between week one and week three in the short dormancy genotypes but decreased in the moderate- to long-dormancy genotypes (Figure 7).

Table 5B.

Periodic changes in the contents of ABA, ZT, and GA1 in experimental tubers of six potato genotypes following γ-radiation during 2018–2019.

| Factors | ABA | Zeatin | GA1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ng g−1 FW | ng g−1 FW | ng g−1 FW | ||

| Irradiation (I) | Control | 98.2a | 16.1b | 0.55e |

| 1.0 kGy | 97.8a | 16.1b | 0.57de | |

| 1.5 kGy | 97.5ab | 16.2b | 0.58cd | |

| 2.0 kGy | 97.1ab | 16.2b | 0.58cd | |

| 2.5 kGy | 96.6bc | 16.2b | 0.60bc | |

| 3.0 kGy | 96.0cd | 16.3ab | 0.63b | |

| 3.5 kGy | 94.9d | 16.5a | 0.69a | |

| LSD I (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.09 | 0.22 | 0.025 | |

| Genotype (G) | FD51-5 | 66.2e | 18.9b | 0.83b |

| PRI red | 56.6f | 22.3a | 0.98a | |

| Sante | 102.3c | 14.6d | 0.45d | |

| FD73-49 | 91.1d | 17.0c | 0.53c | |

| FD69-1 | 129.9b | 12.5e | 0.43d | |

| FD8-1 | 135.2a | 11.9f | 0.38e | |

| LSD G (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.01 | 0.20 | 0.023 | |

| Storage period (SP) | 1 Week | 126.8a | 9.5b | 0.66a |

| 3 Week | 67.0b | 22.9a | 0.55b | |

| LSD SP (P ≤ 0.05) | 0.58 | 0.12 | 0.013 | |

| LSD I × G (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | |

| LSD I × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS | |

| LSD G × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | 1.42 | 0.29 | 0.032 | |

| LSD I × G × SP (P ≤ 0.05) | NS | NS | NS |

NS, non-significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Treatment means sharing same letter differ non-significantly.

LSD, least significant difference.

Figure 7.

Change in ABA, ZT, and GA1 levels in tuber during storage period (3 weeks) following treatment with γ-irradiation. Vertical error bars represent standard error of means (n: 4).

Discussion

The seed potato sector in Pakistan requires genotypes with varied tuber dormancy lengths to fit into various cropping calendars of the growers (Haider et al., 2019). Commonly, the use of dormancy-breaking methods could increase the flexibility in raising consecutive crops. The dormancy breakage through the use of chemicals including bromoethane, thiourea, and rindite has been widely studied, but these chemicals are harmful and unsafe for humans and the environment. Therefore, developing an efficient, safe, and eco-friendly method for the breakage of seed-tuber dormancy is highly demanded.

It has been reported that the reduction of the dormancy period might be due to the effect of benzylaminopurine (BAP) on the nutrient sink that is essential in maintaining the G1-S and G2-M transitions in the plant cell. The exogenous application of cytokinin affects the endogenous nutrient and zeatin (ZT) contents and eventually results in the release of dormancy (Hannapel et al., 2004). During dormancy breaking, the endogenous level of ZT increased, and by contrast, the level of ABA decreased (Deligios et al., 2019). In this study, it was found that the application of 60 mg L−1 BAP significantly reduced the dormancy duration of potato tubers by 19.1 days when compared to the untreated control, and it approved the significant role of exogenous cytokinin in dormancy breaking. The response to treatments for breaking tuber dormancy was highly affected by genotypes; hence, an optimized concentration for each genotype has practical usage for growers.

The combined application of benzyl adenine (BA) with gibberellic acid (GA3) could significantly enhance sprouting when compared to the same levels of BA or GA applied individually (Njogu et al., 2015). The exogenously applied GA3 could stimulate the sprouting of excised tuber buds by enhancing the level of endogenous GA (Alexopoulos et al., 2007; Hartmann et al., 2011). Among different types of GA applied through an exogenous injection, GA1 was the only effective to terminate the dormancy of shortly stored tubers (Suttle, 2004). The endogenous levels of PGRs have been investigated, and it was found that the ABA level decreased and, by contrast, ZT and GA1 increased when the storage duration was prolonged (Suttle, 1998). In this study, the endogenous levels of ABA, ZT, and GA1 in the tubers treated with combined application of BAP and GA3 were significantly changed from the first week to the third week when compared to the control. These changes were found to be more evident in long-term dormancy genotypes than in medium- or short-term dormancy genotypes. However, either a decrease in dormancy duration or an increase in sprout length was more pronounced in short- and medium-term dormancy genotypes. Hence, it was suggested that there is an obvious difference among genotypes in hormonal changes during the dormancy-breaking period.

The exogenous application of GA3 enhances the endogenous level of GAs which affects the synthesis of amylase which enhances starch break down causing quick sprout growth (Krochko et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2014). It was suggested that in this study, the increase in sprout length in the tubers treated with 20 mgL−1 GA3 might be due to the process of starch breakdown mediated by the enzyme, amylase (Sergeeva et al., 2012; Dai et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2018). In the subsequent year, the best doses of BAP and GA3 were experimented together to determine their combined effect on dormancy period and sprout length. The dormancy duration was statistically similar to that of individually applied BAP, but the combined application had a prominent effect on sprout length of tubers compared to individual applications of BAP and GA3.

It is thought that ABA is metabolized mainly by oxidation of the 8′ methyl group to form the unstable intermediate 8′-hydroxy-ABA, which spontaneously rearranges to form phaseic acid (PA), which is then reduced to form dihydrophaseic acid (DPA) (Krochko et al., 1998; Alexopoulos et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2020), while ZT level increased with progression in storage (Letham and Palni, 1983; Horgan, 1986; Alexopoulos et al., 2006). Our findings are consistent with these, as we observed a gradual decrease in the endogenous level of ABA and an increase in the level of ZT. With the increase in storage period (from first to the third week), ZT and GA1 increased in the short dormancy genotypes and ABA decreased; however, GA1 decreased in the moderate- to long-dormancy genotypes.

The variations observed in dormancy duration and sprout length of different genotypes under the effect of electric current are in line with the findings of Kocacaliskan et al. (1989), who observed the decrease in dormancy duration and increase in sprout length with the passage of storage period following application of electric current. However, he did not find any significant difference in the interaction, voltages × days. The encouragement of sprouting by electric current might be due to its stimulation of GA1 synthesis as the electric current had an encouraging effect on ZT and GA1 in this study and deterring effect on ABA. The electric current channelizes the cellular communication in seed tubers which enhances the translocation of food reserves from parenchyma cells of the internal part to the eyes of the tuber and used by the developing sprout (Mishra, 2015). This is the first-ever report on the effect of electric current on endogenous ZT, GA1, and ABA levels of potato tubers.

In potatoes, extended exposure of tubers to temperatures ≤ 2 or ≥30 °C rapidly terminates the dormancy and starts sprouting upon return to moderate temperatures (Wiltshire and Cobb, 1996). In this study, significant differences for dormancy duration and sprout length in experimental genotypes were observed under the effect of cold pre-treatment in comparison with control. The results agree with those of Muthoni et al. (2014), who found that cold pre-treatment of tubers at 2°C shortened the dormancy duration by 2 weeks in long-dormant cultivars. The findings contradict many previous reports that found cold pre-treatment has a non-significant effect on short dormant cultivars (Van Loon, 1987; Van Ittersum and Scholte, 1993). The dormancy breakage through cold pre-treatment might be due to disruption of membrane integrity by low temperature which further leads to electrolyte leakage and subcellular compartmentation. This natural process leads to the use of starch reserves for providing energy for sprout growth.

Previous work related to the effect of cold pre-treatment on endogenous ABA content indicated that initial concentrations of ABA were positively correlated with dormancy duration and negatively correlated with dormancy break (Sonnewald and Sonnewald, 2014). The findings of this study are in agreement with those of Tosetti et al. (2021) that level of ABA is high during dormancy and drops 10–100 times during dormancy break and sprout growth. There is considerable evidence to support the findings related to zeatin increase under the effect of cold pre-treatment. From the findings of Hartmann et al. (2011), it is obvious that the concentrations of cytokinin in tubers stored under different regimes reduce significantly after harvest of the tubers, remain steady during dormancy, but began to increase at dormancy break. The cytokinin concentrations rose faster under high-temperature storage (25°C) compared to low-temperature storage (4°C). Another study supported the current findings where the tubers were stored at 2°C and found that there was a 20- to 50-fold increase in zeatin contents over 6-week storage, coinciding with the natural break of innate dormancy (Bromley, 2009). Similarly, Suttle (1998) reported that an increase in bioactive cytokinin preceded the onset of sprouting in tubers stored under growth permissive conditions and in tubers held in a cold regime (3°C). Cytokinin contents are low in dormant tubers and increased at the commencement of sprouting (Roman et al., 2016). Support for the increase in GA1 content in potato tubers comes from the studies of Suttle et al. (2016) and Lizarazo-Peña et al. (2020), who found the levels of endogenous gibberellins were low during dormancy and increase with the start of bud growth. Again during the sprout growth, the concentration of GA1 in tubers drops again.

There has been no report found to date about the effect of gamma rays on breakage of potato tuber dormancy, although a lot of its use is published in the past to extend the dormancy period. Gamma rays are the super energetic form of electromagnetic radiation, the most penetrating compared to any other ray (Kovacs and Keresztes, 2002). Irradiation of tubers at higher doses might cause disruption in hormonal balance. However, its use at lower doses did not have a significant effect on dormancy breakage. This study found that response to the highest dose (3.5 kGy) was significant for ABA, ZT, and GA1 levels between genotypes and storage periods.

Conclusion

Understanding the concept of postharvest dormancy may provide an insight into the variety's selection for either their use as seed potatoes or short- to long-term storage for fresh market. The genotypes with wide-ranging dormancy can be selected by the farmers depending on the time gap between the crop planting–harvesting. Indeed, different dormancy-breaking methods (use of PGRs, electric current, cold pre-treatment, and irradiation) might create more flexibility for planting a consecutive crop. Of all the studied methods of potato tubers treatment technologically feasible on large volumes is only the method with pre-cooling at low temperature. The variant with tubers soaking in 60 mgL−1 BAP + 20 mgL−1 GA3 has shown the best results and is technologically expedient only in case of tubers cutting mechanization (peeling damage) before processing. Furthermore, the role of endogenous PGRs during dormancy progression clearly shows that ABA was highest initially and declined with the passage of time. Alternatively, ZT was lowest at the start of dormancy and increased with time. While GA1 showed a different response, it increased between week one and week three in the short dormancy genotypes but decreased in the medium- to long-term dormancy genotypes. In further work, the authors recommend studying the field evaluation of different dormancy-breaking methods on emergence, growth, and yield of the potato crop.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MH and MN. Data curation: IA, MK, BA, and MS. Formal analysis: MH, MN, and BA. Funding acquisition: DV, RM, and ME. Investigation: MH, IA, and M. Methodology: MH, RI, and M. Project administration: IA, M, DV, RM, and AA-G. Resources: FA-H and M. Software: RI, MK, and MS. Validation: MN and MK. Visualization: RI, FA-H, ME, and MS. Writing—original draft: MH. Writing—review and editing: MN, IA, BA, DV, RM, MK, AA-G, and RI. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Development Projects to finance excellence (PFE)-14/2022-2024 granted by the Romanian Ministry of Research and Innovation and CASEE Fund for Incentives, project No: CASEE fund 2021-2. Further, the authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2022R483), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for providing help to publish this research work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors highly acknowledge the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan, for providing the facility and resources to conduct this research. The seed material by the Potato Research Institute, Sahiwal. Endogenous PGRs were analyzed at the Hi-Tech laboratory, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad. Dr. Kathleen Haynes (Research Geneticist, USDA, Beltsville, MD, USA) assisted in the statistical analyses of experimental data. Further, the authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2022R483), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.945256/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alexopoulos A. A., Aivalakis G., Akoumianakis K. A., Passam H. C. (2008). Effect of gibberellic acid on the duration of dormancy of potato tubers produced by plants derived from true potato seed. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 49, 424–430. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.02.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos A. A., Aivalakis G., Akoumianakis K. A., Passam H. C. (2009). Bromoethane induces dormancy breakage and metabolic changes in tubers derived from true potato seed. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 54, 165–171. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2009.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos A. A., Akoumianakis K. A., Passam H. C. (2006). The effect of the time and mode of application of gibberellic acid on the growth and yield of potato plants derived from true potato seed. J. Sci. Food Agric. 86, 2189–2195. 10.1002/jsfa.2595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos A. A., Akoumianakis K. A., Vemmos S. N., Passam H. C. (2007). The effect of postharvest application of gibberellic acid and benzyl adenine on the duration of dormancy of potatoes produced by plants grown from TPS. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 46, 54–62. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2007.03.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir K. M., Ali A., Farrukh M. U., Alam M. (2021). Estimation of economic and production efficiency of potato production in Central Punjab. Pakistan. p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Bensen R. J., Beall F. D., Mullet J. E., Morgan P. W. (1990). Detection of endogenous gibberellins and their relationship to hypocotyl elongation in soybean seedlings. Plant Physiol. 94, 77–84. 10.1104/pp.94.1.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley J. R. (2009). Cytokinin Interconversion by StCKP1 Controls Potato Tuber Dormancy. (Doctoral dissertation: ). University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan J. E. (1989). Breaking dormancy of potato tubers. CIP. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera E., Bou J., García-Martínez J. L., Prat S. (2000). Changes in GA 20-oxidase gene expression strongly affect stem length, tuber induction and tuber yield of potato plants. Plant J. 22, 247–256. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00736.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claassens M. M. J., Vreugdenhil D. (2000). Is dormancy breaking of potato tubers the reverse of tuber initiation? Potato Res. 43, 347–369. 10.1007/BF02360540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H., Fu M., Yang X., Chen Q. (2016). Ethylene inhibited sprouting of potato tubers by influencing the carbohydrate metabolism pathway. J. Food Sci. Technol. 53, 3166–3174. 10.1007/s13197-016-2290-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P. J. (2004). Plant Hormones: Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action!. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Deligios P. A., Rapposelli E., Mameli M. G., Baghino L., Mallica G. M., Ledda L. (2019). Effects of physical, mechanical and hormonal treatments of seed-tubers on bud dormancy and plant productivity. Agronomy. 10, 33. 10.3390/agronomy10010033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Destefano-Beltrán L., Knauber D., Huckle L., Suttle J. C. (2006). Effects of postharvest storage and dormancy status on ABA content, metabolism, and expression of genes involved in ABA biosynthesis and metabolism in potato tuber tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 61, 687–697. 10.1007/s11103-006-0042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider M. W., Ayyub C. M., Malik A. U., Ahmad R. (2019). Plant growth regulators and electric current break tuber dormancy by modulating antioxidant activities of potato. Pakistan J. Agri. Sci. 56, 867–877. 10.21162/PAKJAS/19.7428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hannapel D. J., Chen H., Rosin F. M., Banerjee A. K., Davies P. J. (2004). Molecular controls of tuberization. Am. J. Potato Res. 81, 263–274. 10.1007/BF02871768 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A., Senning M., Hedden P., Sonnewald U., Sonnewald S. (2011). Reactivation of meristem activity and sprout growth in potato tubers require both cytokinin and gibberellin. Plant Physiol. 155, 776–796. 10.1104/pp.110.168252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan R. (1986). Plant growth regulators and the control of growth and differentiation in plant tissue cultures. Plant Biol. 3, 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid F., Mubarik A., Aqsa Y. (2020). Potato Cluster Feasibility and Transformation Study. Cluster Development Based Agriculture Transformation Plan Vision-2025. Islamabad: Planning Commission of Pakistan. [Google Scholar]

- Khan I. A. (2004). PARS-70: an interspecific potato hybrid suitable for long storage and autumn-to-autumn seed multiplication. Potato Res. 47, 187–193. 10.1007/BF02735984 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. S., Jeon J. H., Choi K. H., Joung Y. H., Joung H. (1999). Effects of rindite on breaking dormancy of potato microtubers. Am. J. Potato Res. 76, 5–8. 10.1007/BF02853551 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kocacaliskan I., Kufrevioglu I., Keha E. E., Caliskan S. (1989). Breaking dormancy in potato tubers by electric current. J. Plant Physiol. 135, 373–374. 10.1016/S0176-1617(89)80136-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs E., Keresztes A. (2002). Effect of gamma and UV-B/C radiation on plant cells. Micron 33, 199–210. 10.1016/S0968-4328(01)00012-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krochko J. E., Abrams G. D., Loewen M. K., Abrams S. R., Cutler A. J. (1998). (+)-Abscisic acid 8′-hydroxylase is a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase. Plant Physiol. 118, 849–860. 10.1104/pp.118.3.849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou M. C., Antoniou C., Rouphael Y., Graziani G., Kyratzis A. (2021). Mapping the primary and secondary metabolomes of carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) fruit and its postharvest antioxidant potential at critical stages of ripening. Antioxidants. 10, 57. 10.3390/antiox10010057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letham D. S., Palni L. M. S. (1983). The biosynthesis and metabolism of cytokinins. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 34, 163–197. 10.1146/annurev.pp.34.060183.001115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lizarazo-Peña P. A., Fornaguera-Espinoza F., Ñústez-López C. E., Cruz-Gutiérrez N. A., Moreno-Fonseca L. P. (2020). Effect of gibberellic acid-3 and 6-benzylaminopurine on dormancy and sprouting of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers cv. Diacol Capiro. Agronomía Colombiana 38, 178–189. 10.15446/agron.colomb.v38n2.82231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mani F., Bettaieb T., Doudech N., Hannachi C. (2013). Effect of hydrogen peroxide and thiourea on dormancy breaking of microtubers and field-grown tubers of potato. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 21, 221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A. K. (2015). Biomolecular characterization of impact of weak electric field on the plant system. Indian J. Scientific Res. 6, 25–29. Available online at: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A454498328/AONE?u=anon~dbfcc243&sid=googleScholar&xid=34f8ed77 [Google Scholar]

- Muthoni J., Kabira J., Shimelis H., Melis R. (2014). Regulation of potato tuber dormancy: a review. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 8, 754–759. Available online at: https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/INFORMIT.372072986689603 [Google Scholar]

- Njogu M. K., Gathungu G. K., Daniel P. M. (2015). Comparative effects of foliar application of gibberellic acid and benzylaminopurine on seed potato tuber sprouting and yield of resultant plants. Am. J. Agric. 3, 192–201. 10.11648/j.ajaf.20150305.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pande P. C., Singh S. V., Pandey S. K., Singh B. (2007). Dormancy, sprouting Behaviour and weight loss in Indian potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) varieties. Indian J. Agric Sci. 77, 715–720. [Google Scholar]

- Roman H., Girault T., Barbier F., Péron T., Brouard N., Pencík A., et al. (2016). Cytokinins are initial targets of light in the control of bud outgrowth. Plant Physiol 172, 489–509. 10.1104/pp.16.00530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salimi K., Afshari R. T., Hosseini M. B., Struik P. C. (2010). Effects of gibberellic acid and carbon disulphide on sprouting of potato minitubers. Sci. Hortic. 124, 14–18. 10.1016/j.scienta.2009.12.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeeva L. I., Claassens M. M. J., Jamar D. C. L., Van Der Plas L. H. W., Vreugdenhil D. (2012). Starch-related enzymes during potato tuber dormancy and sprouting. Russian J. Plant Physiol. 59, 556–564. 10.1134/S1021443712040115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnewald S., Sonnewald U. (2014). Regulation of potato tuber sprouting. Planta. 239, 27–38. 10.1007/s00425-013-1968-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttle J. C. (1998). Postharvest changes in endogenous cytokinins and cytokinin efficacy in potato tubers in relation to bud endodormancy. Physiol. Plant. 103, 59–69. 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1998.1030108.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suttle J. C. (2004). Involvement of endogenous gibberellins in potato tuber dormancy and early sprout growth: a critical assessment. J. Plant Physiol. 161, 157–164. 10.1078/0176-1617-01222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttle J. C., Abrams S. R., De Stefano-Beltrán L., Huckle L. L. (2012). Chemical inhibition of potato ABA-8'-hydroxylase activity alters in vitro and in vivo ABA metabolism and endogenous ABA levels but does not affect potato microtuber dormancy duration. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 5717–5725. 10.1093/jxb/ers146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttle J. C., Campbell M. A., Olsen N. L. (2016). Potato tuber dormancy and postharvest sprout control. Postharvest ripening physiology of crops 449–476. [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Wang L., Ma C., Liu J., Liu B., Li H. (2011). The use of HPLC in determination of endogenous hormones in anthers of bitter melon. J. Life Sci. 5, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Tosetti R., Waters A., Chope G. A., Cools K., Alamar M. C., McWilliam S., et al. (2021). New insights into the effects of ethylene on ABA catabolism, sweetening and dormancy in stored potato tubers. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 173, 111420. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2020.111420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ittersum M. K., Scholte K. (1993). Shortening dormancy of seed potatoes by a haulm application of gibberellic acid and storage temperatures regimes. Am. J. Potato Res. 70, 7–19. 10.1007/BF02848643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon C. D. (1987). Effect of physiological age on growth vigour of seed potatoes of two cultivars. 4. Influence of storage period and storage temperature on growth and yield in the field. Potato Res. 30, 441–450. 10.1007/BF02361921 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco J. M., Flores H. E. (2000). Control of root formation by plant growth regulators. Plant growth Regul. Agric. Hortic. Their role Commer. uses. Food Prod. Press. an Impr. Haworth Press. New York. p. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Ma R., Zhao M., Wang F., Zhang N., Si H. (2020). NO and ABA interaction regulates tuber dormancy and sprouting in potato. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 311. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire J. J. J., Cobb A. H. (1996). A review of the physiology of potato tuber dormancy. Ann. Appl. Biol. 129, 553–569. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1996.tb05776.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wurr D. C. E. (1978). “'seed'tuber production and management,” in The potato crop. Springer. p. 327–354. 10.1007/978-1-4899-7210-1_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Onik J. C., Hu X., Duan Y., Lin Q. (2018). Effects of (S)-carvone and gibberellin on sugar accumulation in potatoes during low temperature storage. Molecules. 23, 3118. 10.3390/molecules23123118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Hou J., Liu J., Xie C., Song B. (2014). Amylase analysis in potato starch degradation during cold storage and sprouting. Potato Res. 57, 47–58. 10.1007/s11540-014-9252-631253316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.