Abstract

In the Internet age, some online factors, such as online self-presentation, related to life satisfaction have received much attention. However, it is unclear whether and how different strategies of online self-presentation are linked to an individual’s life satisfaction differently. Accordingly, the present study examined the possible different relationships between different online self-presentations and life satisfaction with a sample of 460 Chinese college students. Using a series of questionnaires, a moderated mediation model was built in which positive online feedback was a mediator and self-esteem was a moderator. The results indicated that: (1) positive self-presentation was negatively associated with college students’ life satisfaction, whereas honest self-presentation was positively related to it; (2) positive online feedback was a significant mediator in such relationships; (3) the mediation process was moderated by self-esteem. Specifically, positive self-presentation was negatively related to positive online feedback only for high self-esteem college students, but negatively associated with life satisfaction only for low self-esteem ones. By contrast, honest self-presentation was positively associated with positive online feedback despite the level of self-esteem, but positively linked with life satisfaction only for those with low self-esteem. The findings suggest that honest rather than positive online self-presentation should be conducive to college students’ life satisfaction, particularly for those with low self-esteem. The implications were discussed.

Keywords: Online self-presentation, Positive online feedback, Life satisfaction, Self-esteem, College students

Introduction

Life satisfaction, as a key indicator of well-being, refers to how an individual overall assesses and feels his or her lives during most of the time or a certain period of time (Diener et al., 2002; Maddux, 2018). It has been shown to be positively related to many personal psychological, behavioral, interpersonal, and social outcomes (Proctor et al., 2009). It can mediate the association of adverse life events with suicidal ideation as well (Yang et al., 2020), and improving individuals’ life satisfaction helps reduce the risks of mental disorder (Chen et al., 2017). Therefore, identifying its contributing factors has long been concerned by scholars.

Traditionally, when an individual has a high quality of social network and perceives much social support from this network, he or she will have a high level of life satisfaction (Lebacq et al., 2019) because good interpersonal communication produces positive emotion and affect (Diener et al., 1991). In the Internet age, however, online social networking sites (SNSs) have been indispensable mediums for individuals to present themselves and communicate with others (Pew Research Center, 2018). They remain an effective way of online socialization for individuals who are capable of maintaining personal relationships with friends from near and far (Brailovskaia et al., 2020). Therefore, some online factors related to life satisfaction have attracted much attention. This topic is especially important in certain periods, such as a special time of the COVID-19 pandemic when individuals have fewer face-to-face social contacts and turn to SNSs for happiness.

On SNSs, individuals can post photos and videos, likes, comments, and share their personal stories with others (Aljasir et al., 2017; Kuss & Griffiths, 2017). When they present this personal information, some individuals may selectively show information that are beneficial to the self in order to actively make themselves look positive in public (Wright et al., 2018); In contrast, others would rather express themselves in a real and sincere way, disclosing their personal information deeply. Numerous studies have indicated that the quantity of online self-disclosure is positively linked to subject well-being (SWB) (Bij de Vaate et al., 2019; Chan, 2021; Jang et al., 2018; Kim & Lee, 2011; Tyler et al., 2018) or life satisfaction (Kereste & Tulhofer, 2019; Pang, 2018; Wang, 2013). However, it is not well answered whether and how different self-presentation strategies are associated with them differently. Accordingly, the current study explored the possible different relationships between different self-presentations on SNSs and life satisfaction and a mediating role of positive online feedback in these associations as well as a moderation role of self-esteem in the mediating process.

Online self-presentation and life satisfaction

In terms of relationship management, the strategies of online self-presentation can be divided into two contrasting categories (Kim & Lee, 2011): positive self-presentation and honest self-presentation. The former refers to selectively revealing or highlighting one’s positive aspects in order to create a good impression on SNSs. In contrast, the latter is more strongly associated with one’s honest self that represents one’s real characteristics, reflecting the way users authentically disclose their feelings, thoughts as well as life events on SNSs.

According to the self-discrepancy theory posited by Higgins (1987), people often copmare their own actual self with the ideal self, while a larger discrepancy between the two will lead to more negative psychological outcomes, such as disappointment and anxiety. Actually, Facebook users usually disclose more positive emotions rather than negative ones on Facebook (Ziegele & Reinecke, 2017). This positivity bias on Facebook seems likely to attenuate the willingness to present real, but negative information (e.g., distress). It will lead to a larger difference between the real self and the virtual self, and then produce negative emotions (Grieve et al., 2020). In this sense, inauthentic self-presentation on SNSs can be related to many psychological problems of maladjustment (Grieve & Watkinson, 2016), such as high social anxiety (Duan et al., 2020; Twomey & O'Reilly, 2017), low self-esteem (Manago, 2015), poor psychosocial well-being (Michikyan et al., 2014), and problematic social networks use (Li et al., 2018). In other words, concealing one’s self behind positive self-presentation may result in negative emotions and adverse thoughts (D’agata & Holden, 2018; Jackson & Luchner, 2017).

In contrast, individuals can have higher self-concept clarity regarding social anxiety (Orr & Moscovitch, 2015) and improve subjective happiness in honest self-presentation (Jang et al., 2018). Sharing honest personal information, thoughts, and feelings enables people to express themselves, buffer negative feelings, and provide psychological benefits (Kim & Dindia, 2011). Research has found that people who present their real self on SNSs have more positive affect, less negative affect (Reinecke & Trepte, 2014), greater happiness particularly for those high self-esteem individuals (Jang et al., 2018), and higher levels of SWB (Lee & Borah, 2020).

Social penetration theory (SPT; Taylor, 1968) can also explain the association of honest self-presentation with life satisfaction from the aspect of interpersonal relationships. SPT proposes that information disclosed to others has different types and layers, and that the development of relationships depends on how individuals reveal their personal information, such as their attitudes, feelings, and likes, to each other (Taylor & Altman, 1987). Honest self-presentation on SNSs is a special way for individuals to present their true self to their friends (Nadkarni & Hofmann, 2012), which can enhance interpersonal trust and the intimate relationship between friends (Lin & Utz, 2017), and help individuals accumulate social capital and obtain social support (Sosik & Bazarova, 2014). Specifically, honest self-presentation on SNSs helps to construct and maintain good social ties (Lee et al., 2011), and contributes to relief of individual depression and loneliness, and to improvement of individual life satisfaction (Chai et al., 2018; Grieve & Watkinson, 2016). Meanwhile, for all tested demographic groups, interpersonal relationships have been found to be an obvious contributor to life satisfaction (Bermack, 2014).

Despite accumulating evidence supporting different relationships between different self-presentations and life satisfaction, empirical evidence of comparing them directly in a same study is very scarce. Thus, by incorporating previous literature, we aimed to fill this gap and hypothesized that positive self-presentation would be negatively linked with life satisfaction, whereas honest self-presentation would be positively related to it (H1).

Positive online feedback as a mediator

When presenting ourselves, we generally imagine and speculate how audience respond to us, and typically search for such feedback from others to evaluate ourselves (Goffman, 1959). On SNSs, a unique feature is that audience feedback is available, immediate and quantifiable (Schlosser, 2020). As a result, users can often obtain timely feedback after online self-presentation (Metzler & Scheithauer, 2018). Among them, positive online feedback is an important type of social support, mainly in the form of positive and timely evaluations during online interactions (Liu & Brown, 2014). Specifically, it refers to the supportive responses that individuals receive after they post or update personal information on SNSs, such as likes (Metzler & Scheithauer, 2017) and positive comments (Bazarova et al., 2015). Previous research has indicated that adults’ different areas of self-presentation on Facebook are related to positive feedback from the online audience (Liu & Brown, 2014; Yang & Brown, 2016). This perceived positive online feedback also can lead to positive social consequences (Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2019). Positive feedback indicates being accepted, concerned, and socially supported, implying that the responder has positive attitude to the individual, and solidifying their relationship (Lee et al., 2014; Liu & Brown, 2014). Accordingly, positive online feedback should be a key mediator in the relationship between online self-presentation and life satisfaction.

In terms of the relationship between different self-presentation and positive online feedback, positive self-presentation can not contribute to people’s mental health or relationship if people are unable to trust in others on SNSs (Kim & Baek, 2014), whereas those who present themselves in a “courageous” and even self-deprecating way acquire much social support (Bareket-Bojmel et al., 2016). Although we usually regard self-derogation as a problematic behavior which may cause to adverse social outcomes (e.g., social reject) (Ollier-Malaterre et al., 2013), some studies support that self-derogation is not always unfavorable while self-enhancement does not always lead to positive outcomes. For example, research has found that people tend to consider those who like to enhance themselves but fail to show an expected performance actually as boastful and give them low evaluations (Schlenker & Leary, 1982), whereas undergraduates who choose to self-derogation when presenting themselves on SNSs receive increased positive feedback from their social network (Bareket-Bojmel et al., 2016).

As found, the deep and real self-disclosure on SNSs can gain more social support (Hampton & Lu, 2015; Ko & Kuo, 2009; Seo et al., 2016). When individuals present broader, deeper, and more authentic information on SNSs, they will get more online feedback from their friends (Yang, 2014). Only when individuals seek support via honest and sincere self-disclosure, can they receive it with a greater likelihood from others (Greene et al., 2006; Li et al., 2020), which could be beneficial to their SWB (Bij de Vaate et al., 2019; Luo & Hancock, 2019). While presenting a positive but untrue self, one can not receive helpful social support from their Facebook friends and thereby can not really feel happy (Oh et al., 2014).

On the basis of the above literature, we concluded that positive self-presentation would be negatively linked to positive online feedback but honest self-presentation would be positively associated with it.

In terms of the relationship between positive online feedback and life satisfaction, positive online feedback has been consistently found to be positively related to individuals’ social support (Lee et al., 2014; Liu & Brown, 2014; Wohn et al., 2016) and life satisfaction (Satici & Uysal, 2015; Wenninger et al., 2014). According to uncertainty reduction theory, interactive and verbal strategies are good ways for individuals to solve the relational uncertainty (Jin & Pena, 2010; Neuliep, 2012). Positive online feedback is very common during online interaction. It helps individuals understand how their friends see them by providing certain information for them (Brashers et al., 2004). Previous research has also found that the affirmation and recognition from others can effectively improve the attitude and evaluation towards oneself (Sung et al., 2016; Yang, 2014), which can improve their life satisfaction and happiness (Scissors et al., 2016). Given that social support is a vital source of happiness, and related to improved well-being (Haber et al., 2007), positive feedback, a more specific type of social support, provided by one’s online friends such as likes and comments may also positively contribute to the individual’s happiness and SWB (Kim & Lee, 2011; Zell & Moeller, 2018). In other words, the more social support from positive online feedback individuals perceived, the higher life satisfaction level they had (Nabi et al., 2013; Shahyad et al., 2011).

Accordingly, by incorporating previous literature, we predicted that positive online feedback would be a key mediator in the associations of different self-presentations with life satisfaction (H2). It has been shown to mediate the relationship between honest self-presentation and life satisfaction (Liu et al., 2016). It can mediate the association between self-disclosure on SNSs and bonding social capital as well (D. Liu & Brown, 2014). It also plays a mediating role in the link between online self-presentation and individuals’ self-esteem (Meeus et al., 2019). However, empirical evidence of its mediating role in the different relationships between different self-presentations and life satisfaction is scanty. Therefore, we aimed to narrow this gap in the current study and tested this hypothesis.

Self-esteem as a moderator

In addition to the mediating role of positive online feedback at an environmental level, self-esteem, one’s positive or negative attitudes towards the self (Rosenberg, 1965), may serve as a key moderator in this mediation model at an individual level.

According to previous experimental results, those high self-esteem individuals not only show more defense against negative information, but also accept less negative information (Zhou et al., 2018). By contrast, individuals with low self-esteem are not only more likely to perceive external rejection information (Zhou et al., 2018), but also more likely to perceive others’ behavior as rejection (Kashdan et al., 2014), thus perceiving less positive feedback. This is because low self-esteem individuals can not focus on their own qualities and do not have the ability to overcome negative or rejection information (Tazghini & Siedlecki, 2013). Therefore, for people with low self-esteem, in the case of receiving a large amount of feedback after self-presentation on SNSs, those negative rejection messages may attract their attention first. In the study of Cameron et al. (2009), individuals whose self-esteem is either high or low expressed failure information to their partners and received same positive feedback, but people with low self-esteem could not correctly perceive the positive feedback provided by their partners, and reported less positive feedback than their counterparts.

The “poor get poorer” Internet theory proposes that overuse of SNSs may destroy individuals’ well-being, and this negative effect is even worse particularly for people who lack adequate psychosocial support from others in daily life (Selfhout et al., 2009; Snodgrass et al., 2018). Thus, individuals with low self-esteem may perceive less positive feedback and life satisfaction than those high self-esteem ones when they present themselves on SNSs. Furthermore, according to the self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987), when individuals present themselves positively on SNSs, the discrepancies between their actual self-state and ideal self-state will be greater for low self-esteem individuals than for high self-esteem ones, signifying more loss of positive outcomes and more dejection-related emotions. In addition, high self-esteem can operate as a buffer which can mitigate the negative effect of using positive self-presentation due to its low vulnerability to loss and strong resilience, in accordance with the buffer hypothesis (Arndt & Goldenberg, 2002), but people with low self-esteem would suffer a lot. Consequently, we deduced that positive self-presentation would be related to less positive feedback and life satisfaction, particularly for low self-esteem individuals.

In contrast, individuals with high self-esteem feel better about themselves and are more likely to believe themselves as attractive or popular than do their counterparts (Wood & Forest, 2016). They believe they are lovable, deserving of attention, and feel that if they are in trouble, others will respond to their needs and be ready to help them (Palermiti et al., 2017). As a result, they are able to feel more loved and accepted by others. In addition, they are more likely to perceive others’ supportive responses when they present themselves on SNSs (Greitemeyer et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2017). Thus, high self-esteem individuals would be more confident and easeful when showing the self honestly to online friends than low self-esteem ones. By disclosing true oneself on SNSs, they would also reveal more competence and thus perceived more positive online feedback and life satisfaction (Jang et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Similarly, from the aspect of “rich get richer” theory, individuals who have good social skills and adequate social support will benefit more from the Internet use (Kraut et al., 2002; Reer & Krämer, 2017). There is agreement that more sociable people are more capable of making better use of the opportunities offered by SNS to strengthen their social network (Ross et al., 2009). For example, individuals not only can get all kinds of valuable support and help from their friends through using SNSs (Indian & Grieve, 2014; Wohn & Larose, 2014), but also can meet the needs of self-worth and self-integration and have relatively pleasant emotional experience (Wise et al., 2010). Therefore, SNSs use can improve their life satisfaction (Pang, 2018; Shahyad et al., 2011). Accordingly, those high self-esteem individuals may particularly perceive more positive feedback and life satisfaction when they present themselves honestly on SNSs than those low self-esteem individuals.

The possible moderation role of self-esteem, however, has not been fully explored in the previous research, we therefore examined it and hypothesized that positive self-presentation would be related to low sense of positive online feedback and life satisfaction, particularly for those low self-esteem individuals, whereas it would be weaker for those high self-esteem individuals (H3) and that honest self-presentation would be related to heightened sense of positive online feedback and life satisfaction, particularly for high self-esteem individuals, whereas it would be weaker for those low self-esteem individuals (H4).

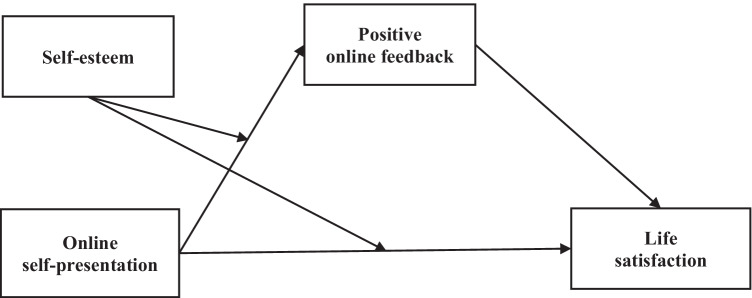

In sum, as shown in Fig. 1, we examined a moderated mediation model in which positive online feedback would differently mediate the different associations of different self-presentation with college students’ life satisfaction and self-esteem would differently moderate this mediating process as well.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized model

Methods

Participants

Participants included 460 Chinese college students from one normal university located in eastern China. A priori power analysis with the G*Power 3 software package (Faul et al., 2009) indicated that the sample size that would provide an adequate power (0.95) and a moderate effect size (f2 = 0.15) at a 0.05 significance level (α) using a hierarchical regression analysis with 4 tested predictors would be 129 participants, and thus justifying this sample size. Forty students were excluded due to missing data or inaccurately completing the measures. Ultimately, 420 students completed the survey with a response rate of 91%. The final sample consisted of 244 (58.10%) females and 176 (41.90%) males aged from 18–24 (M = 20.23, SD = 4.59). Among these students, 145 (34.52%) were freshman, 106 (25.24%) were sophomore, 80 (19.05%) were junior, and 89 (21.19%) were senior; 276 (65.71%) were from rural areas and 144 (34.29%) were from urban areas.

Measures

Online self-presentation

Online self-presentation was assessed with nine items adapted from positive self-presentation and honest self-presentation scale (Kim & Lee, 2011) by Niu et al. (2015). The positive self-presentation subscale consists of 5 items, which is designed to evaluate how individuals selectively present positive aspects of themselves on SNSs (e.g., ‘‘I post photos that only show the happy side of me’’). The honest self-presentation subscale consists of 4 items that assesses the extent to which individuals honestly present their true selves on SNSs (e.g., ‘‘I don’t mind writing about bad things that happen to me when I update my status’’). All items were answered on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = ‘‘strongly disagree’’; 7 = ‘‘strongly agree’’). A higher averaged score indicated more positive/honest self-presentation on SNSs. The Chinese version of this scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties among Chinese college students (α = 0.82, 0.74; Niu et al., 2015). In the present study, the Cronbach’s αs for the two subscales were 0.85 and 0.79 respectively.

Positive online feedback

Positive online feedback was measured using the positive online feedback scale adapted from Liu and Brown (2014). The scale is composed of 5 items (e.g., “When I update my status on SNSs”; “When I post photos on SNSs”) assessing how often participants received positive feedback on SNSs. All items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “never”; 5 = “frequently”). The scale focuses on the overall frequency of positive online feedback rather than its level of positivity, as it is difficult for college students to determine the level of positive feedback (Liu & Brown, 2014). The higher the averaged score, the more frequently the participants were to receive positive feedback from friends while using SNSs. The Chinese version of this scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties among Chinese college students (α = 0.90; Jiang et al., 2019). The Cronbach’s α was 0.92 in the present study.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was measured by a revised Chinese version of Rosenberg (1965) Self-Esteem scale. The scale is composed of 10 items (e.g., “I am able to do things as well as most other people.”). Considering that the 8th item in the scale is not suitable for measuring Chinese self-esteem due to cultural difference (Tian, 2006), only the remaining 9 items were used in the present study. They were answered on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = ‘‘strongly disagree’’; 4 = ‘‘strongly agree’’). A higher averaged score indicated a higher self-esteem. The Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.90 in the current study.

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured with six items developed by Wang and Shi (2003). The items (e.g., “How satisfied are you with your current life?”) were answered on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 7 = “strongly agree”) and then averaged to form an overall score of life satisfaction. The higher the averaged score, the higher of life satisfaction. In the current study the Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.78.

Procedure

Before the survey began, informed consent was obtained from participants, and the study plan was approved by the Scientific Research Ethic Committee at our university. All participants completed a series of anonymous questionnaires at their classrooms administered by well-trained psychological graduate assistants. The authenticity, independence and completeness of their answers as well as the confidentiality of the information collected were emphasized to all participants. It took approximately 15 min to complete all of the measures.

Data analysis

In the current study, data analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0 and PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013). SPSS 22.0 was used to investigate the correlations among the main variables, and PROCESS macro for SPSS 22.0 to estimate the models. Then, four models were constructed. Among them, two models examined the mediation role of online positive feedback in the relationship between different online self-presentation and life satisfaction. Following MacKinnon’s (2008) four-step procedure, Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro (model 4) was used to estimate the mediating effect. The other two models used Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro (model 8) to tested the moderation role of self-esteem in the two mediation models. Specifically, the current study assessed the effects of moderation of self-esteem on the association of online self-presentation with positive online feedback and on the association of online self-presentation with life satisfaction. In addition, values at two levels of self-esteem (M ± 1SD) were used to calculate the simple slopes. All the variables involved in the analysis were standardized.

As suggested by Preacher and Hayes (2008), the present study used a bootstrap approach to decide the significance of the mediation of positive online feedback. Specifically, 5,000 bootstrapped samples and 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) were used in this approach. If the CI did not contain zero, the effect was seen as significant.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients for all study variables. As expected, the variables were all correlated with each other.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study variables

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive self-presentation | 18.02 | 6.59 | — | ||||

| 2. Honest self-presentation | 17.74 | 5.26 | -0.33*** | — | |||

| Positive online feedback | 13.96 | 5.29 | -0.42*** | 0.56*** | — | ||

| Self-esteem | 26.63 | 5.16 | -0.41*** | 0.52*** | 0.51*** | — | |

| Life satisfaction | 27.79 | 6.60 | -0.43*** | 0.49*** | 0.54*** | 0.70*** | — |

N = 420. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. The same below

Testing the mediation model

Positive self-presentation as a predictor

By the preliminary examining, all independent variables’ variance inflation factors were less than 2.00, therefore there was no multicollinearity.

The results (see Table 2) revealed that positive self-presentation was negatively related to both positive online feedback and life satisfaction, while the latter two were positively associated with each other. Then, the mediation test showed that the path from positive self-presentation to life satisfaction through positive online feedback was significant, ab = – 0.19, Boot SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [– 0.24, – 0.13]. It indicated that positive online feedback partially mediated the relationship between positive self-presentation and life satisfaction but in the opposite direction. The mediation effect was – 0.19, accounting for 42.61% of the total effect.

Table 2.

Testing the mediating role of positive online feedback in the relationship between positive self-presentation and life satisfaction

| Independent variables | Model 1 (DV:LS) | Model 2 (DV: POF) | Model 3 (DV: LS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | b | t | |

| PS | -0.44 | -9.93*** | -0.42 | -9.53*** | -0.25 | -5.74*** |

| POF | 0.44 | 10.18*** | ||||

| R2 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.35 | |||

| F | 98.57*** | 90.82*** | 113.25*** | |||

PS Positive self-presentation, POF Positive online feedback, LS Life satisfaction

Honest self-presentation as a predictor

To test another mediation model, the same procedure was used. As shown in Table 3, however, we found that honest self-presentation was positively related to both positive online feedback and life satisfaction, while the latter two were positively associated with each other. Then, the mediation test showed that the association of honest self-presentation with life satisfaction through positive online feedback was significant, ab = 0.22, Boot SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.17, 0.28]. It indicated that positive online feedback also played a partial mediating role in the relationship between honest self-presentation and life satisfaction with a mediating effect of 0.22, which accounted for 44.02% of the total effect.

Table 3.

Testing the mediating role of positive online feedback in the relationship between honest self-presentation and life satisfaction

| Independent variables | Model 1 (DV:LS) | Model 2 (DV: POF) | Model 3 (DV: LS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | b | t | |

| HS | 0.50 | 11.67*** | 0.56 | 13.78*** | 0.28 | 5.79*** |

| POF | 0.39 | 8.31*** | ||||

| R2 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.35 | |||

| F | 136.15*** | 189.78*** | 113.67*** | |||

HS Honest self-presentation, POF Positive online feedback, LS Life satisfaction

Testing the moderated mediation models

Positive self-presentation as a predictor

As Table 4 illustrates, positive self-presentation was negatively correlated with positive online feedback, while self-esteem was positively linked with it, and the interaction between them was significant on positive online feedback as well, indicating a moderating role of self-esteem in the relationship between positive self-presentation and positive online feedback.

Table 4.

Testing the moderated mediation effects with positive self-presentation as a predictor

| Independent variables | Model 1 (DV: POF) | Model 2 (DV: LS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | |

| Constant | -0.09 | -2.24** | 0.03 | 0.97 |

| PS | -0.22 | -5.30*** | -0.13 | -3.38*** |

| Self-esteem | 0.51 | 11.46*** | 0.49 | 11.24*** |

| PS × Self-esteem | -0.22 | -6.74*** | 0.08 | 2.77** |

| POF | 0.25 | 6.08*** | ||

| R2 | 0.39 | 0.56 | ||

| F | 88.28*** | 129.60*** | ||

PS Positive self-presentation, POF POF, LS Life satisfaction

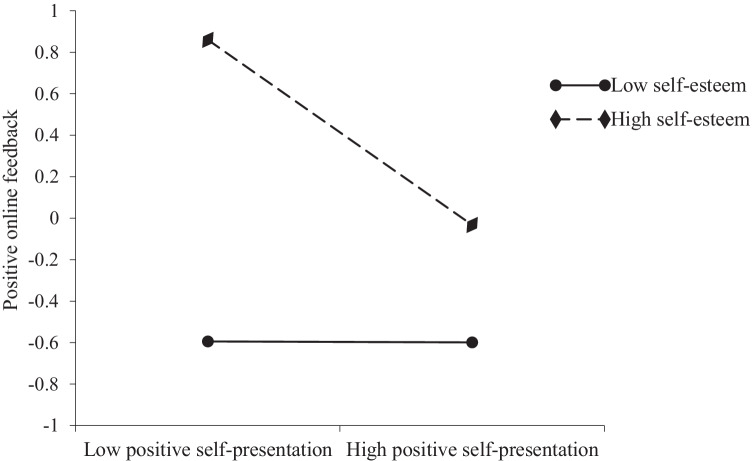

To better understand the moderation effect of self-esteem, Fig. 2 shows the plot of the association of positive self-presentation with positive online feedback at two levels of self-esteem (M ± 1SD). As shown in Fig. 2, positive self-presentation was only significantly associated with positive online feedback for participants with high self-esteem (βsimple = – 0.45, p < 0.001), while not for those with low self-esteem (βsimple = – 0.002, p > 0.05). Although college students with high self-esteem received more positive feedback than those with low self-esteem (t = – 10.97, p < 0.001), they would receive significantly decreased positive feedback when in high levels of positive self-presentation.

Fig. 2.

Moderating role of self-esteem in relationship between positive self-presentation and positive online feedback

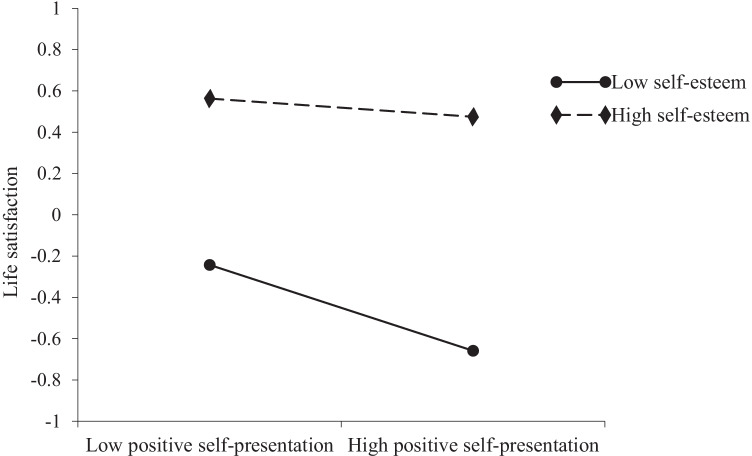

On the other hand, positive self-presentation was negatively linked to life satisfaction, and its interaction with self-esteem was significant on life satisfaction as well, indicating that self-esteem also moderated the relationship between positive self-presentation and life satisfaction.

As shown in Fig. 3, a simple slope test found that positive self-presentation was only significantly related to life satisfaction among college students with low self-esteem (βsimple = – 0.21, p < 0.001) while not among their counterparts (βsimple = – 0.04, p > 0.05). It indicated that participants with low self-esteem not only perceived less life satisfaction than those with high self-esteem (t = – 13.18, p < 0.001), but also further perceived significantly decreased life satisfaction when in high levels of positive self-presentation.

Fig. 3.

Moderating role of self-esteem in relationship between positive self-presentation and life satisfaction

Honest self-presentation as a predictor

To test another conceptual model, the same procedure was used. The results (see Table 5) showed that honest self-presentation and self-esteem were both positively associated with positive online feedback and their interaction was significant on positive online feedback as well.

Table 5.

Testing the moderated mediation effects with honest self-presentation as a predictor

| Independent variables | Model 1 (DV: POF) | Model 2 (DV: LS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | |

| Constant | -0.10 | -2.40* | 0.04 | 1.22 |

| HS | 0.38 | 8.71*** | 0.09 | 2.05* |

| Self-esteem | 0.41 | 8.75*** | 0.48 | 10.73*** |

| HS × Self-esteem | 0.19 | 5.75*** | -0.09 | -2.85** |

| POF | 0.25 | 5.77*** | ||

| R2 | 0.43 | 0.55 | ||

| F | 104.00*** | 126.39*** | ||

HS Honest self-presentation, POF POF, LS Life satisfaction

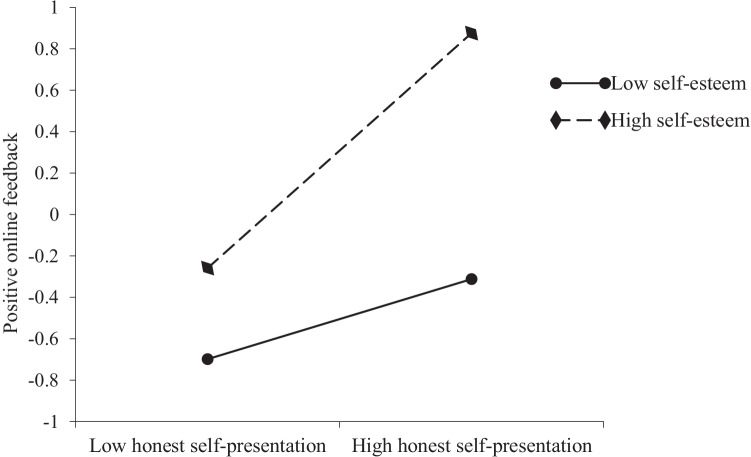

As shown in Fig. 4, a simple slope test found that honest self-presentation was positively linked with positive online feedback either for college students with low self-esteem (βsimple = 0.19, p < 0.001) or for those with high self-esteem, (βsimple = 0.57, p < 0.001), but the latter slope was obviously higher. It indicated that college students with high self-esteem would particularly benefit from high levels of honest self-presentation to positive online feedback.

Fig. 4.

Moderating role of self-esteem in relationship between honest self-presentation and positive online feedback

On the other hand, honest self-presentation was positively linked with life satisfaction, and its interaction with self-esteem was significant on life satisfaction as well.

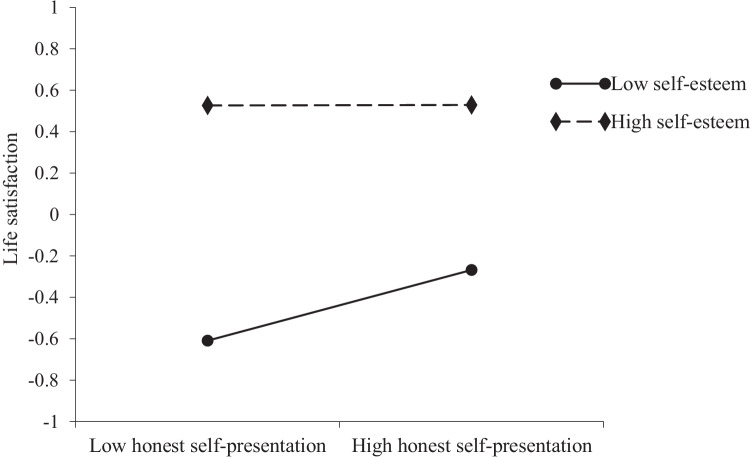

As shown in Fig. 5, a simple slope test found that honest self-presentation was only significantly and positively related to life satisfaction among college students with low self-esteem (βsimple = 0.17, p < 0.001) while not among those with high self-esteem (βsimple = 0.001, p > 0.05). Although college students with low self-esteem perceived less life satisfaction than their counterparts (t = – 13.18, p < 0.001), they would perceive significantly increased life satisfaction when in high levels of honest self-presentation.

Fig. 5.

Moderating role of self-esteem in relationship between honest self-presentation and life satisfaction

Discussion

Although the association between online self-presentation and individual life satisfaction has been studied in previous research, it is yet unclear whether and how different strategies of self-presentation are related to life satisfaction differently. The current study answered this question by revealing the direct and indirect relationships between different self-presentation and life satisfaction through positive online feedback and the moderating effect of self-esteem on them.

Online self-presentation and life satisfaction

In accordance with H1, the results showed that positive self-presentation was negatively related to college students’ life satisfaction whereas honest self-presentation was positively linked with it.

Although SNSs offer college students a platform to connect to known and unknown online friends, present their own information, and look for others’ information (Griffiths et al., 2014; Kuss & Griffiths, 2017), the so-called friends on SNSs not only overlap with the social circle in real life, but also involve some strange net friends. Therefore, some college students will try to create a positive image by presenting positive information selectively. When individuals present themselves positively, they deliberately hide negative information and filter their cognition of themselves, real life and future negative aspects (Wright et al., 2018). Such cognitive filtering that cannot reflect the real situation will hinder their self-integration and self-acceptance (Carson & Langer, 2006). In line with the self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987), this will lead to a greater self-discrepancy between the actual self and the virtual self, and then produce negative emotions (Grieve et al., 2020). Similarly, other studies have also indicated that a larger discrepancy between the real self and the ideal self will cause to greater psychological discomfort (Grieve et al., 2020; Heng et al., 2018), which further reduces their life satisfaction.

On the contrary, honest self-presentation seems to contribute to college students’ life satisfaction, as found in previous research (Kim & Lee, 2011). On the one side, it can be interpreted that individuals can present their real information and status on SNSs to carry out self-affirmation (Toma, 2013), thus obtaining social support (Ko & Kuo, 2009) and improving SWB (Bij de Vaate et al., 2019; Luo & Hancock, 2019). On the other side, according to the social penetration theory, honest self-presentation is beneficial for deepening interpersonal relationships, gaining interpersonal trust, and increasing social support (Lin & Utz, 2017; Sosik & Bazarova, 2014), which helps improve life satisfaction. As a result, when college students present themselves more authentically on SNSs, their life satisfaction is higher.

The mediating role of positive online feedback

Consistent with H2, we found that positive online feedback mediated the different relationships between different self-presentations and college students’ life satisfaction in different directions.

This is possible because when individuals present themselves positively rather than honestly on SNSs, other people may fail to form trust in them which will be unfavorable for their mental health and interpersonal relationship (Kim & Baek, 2014), whereas they will receive more positive feedback when they disclose themselves honestly even negatively (Bareket-Bojmel et al., 2016). While positive self-presentation may maintain a level of positive self-image, it hides the negative side of individuals, which may go against the development of deep intimate relationships and the acquisition of beneficial social support (Oh et al., 2014). Only when individuals seek support through disclosing themselves honestly, they can receive it with a great likelihood from online friends (Greene et al., 2006), and such support has been consistently shown to be positively linked to their SWB (Bij de Vaate et al., 2019; Luo & Hancock, 2019). While individuals hide behind a smiling online mask, it is difficult for them to acquire meaningful social support from online friends (Oh et al., 2014). Meanwhile, when individuals perceive less social support, their life satisfaction and overall SWB decrease, resulting in fewer positive emotions and more negative emotions (Kong & You, 2013). Therefore, when college students used more positive self-presentation on SNSs, they would perceive less positive online feedback, and thereby decrease their life satisfaction.

By contrast, because honest self-presentation is an individual’s real presentation on SNSs, which is sincere and open, it can help an individual reduce negative emotions or attitudes (Grieve & Watkinson, 2016), get more social support (Yang, 2014) and thereby improve life satisfaction (Chai et al., 2018) by showing one’s real side and sharing the current real situation. Although honest self-presentation may present negative information or attitudes about oneself, an individual’s unadorned and authentic presentation of information enables friends to perceive their current real situation, and thus provide their support and help more easily (Greene et al., 2006; Kim & Lee, 2011). As well, from the perspective of social penetration theory, honest self-presentation on SNSs can increase interpersonal trust and intimacy (Jian & Li, 2018), maintain interpersonal relationships and obtain social support (Ko & Kuo, 2009), and enable individuals to obtain emotional social support and social identification (Xie, 2014). Thus, honest self-presentation can enable college students to know themselves more objectively and clearly, perceive more positive online feedback, and then improve life satisfaction.

The moderating role of self-esteem

Partially consistent with H3, more positive self-presentation was found to be connected with less life satisfaction, only for those low self-esteem individuals, but associated with less positive online feedback only for those high self-esteem ones.

These findings partially supported the “poor get poorer” theory, which believes individuals with inadequate development resources in their real lives might erode their well-being through bad online experience (Selfhout et al., 2009; Snodgrass et al., 2018). They partially supported Higgins’s (1987) self-discrepancy theory as well, according to which people with low self-esteem will perceive larger differences between the real self and the ideal self when they present themselves positively but not honestly and thereby experience more dissatisfaction with themselves and their lives.

However, it is not the case for the results about positive online feedback. Several reasons can be considered. First, life satisfaction is a judgmental process that based on self-selected standards, which is greatly affected by the level of individual self-esteem. However, the frequency of positive online feedback is an objective component, which has little to do with individual experience/perception to some extent. Second, high self-esteem may be regarded as ostentation when individuals presenting excessive positive self, which will cause the audience’s disgust (Schlenker, 1980) and then lead to a significant decrease in positive feedback. By contrast, the audiences, particularly those who know the low self-esteem individuals, may relatively tolerate and encourage them when they present some positive information of themselves. Certainly, another possible explanation of the result about low self-esteem is that individuals with low self-esteem often look down on their own worth (Forest & Wood, 2012), and thus are not only more likely to perceive external rejection information (Zhou et al., 2018), but also more likely to perceive others’ behavior as rejection (Kashdan et al., 2014). They are also inclined to concentrate on concealing their perceived shortcomings and true feelings (Baumeister et al., 1989), which may hinder their social support seek and acquisition and thereby receive less positive feedback (Oh et al., 2014). Therefore, whether they have less or more positive self-presentation, the frequency of positive online feedback they received were always lower with no significant change, compared to their counterparts, as indicated in the present study. These results suggest that positive but not real self-presentation should be not good for everyone, but particularly for those low self-esteem individuals in terms of decreased life satisfaction and for those high self-esteem ones in terms of reduced positive feedback.

As well, H4 was partially supported. Honest self-presentation was found to be linked to high sense of positive online feedback despite the levels of self-esteem of participants, particularly for those high self-esteem individuals, but linked with more life satisfaction only for those low self-esteem ones.

These results seemed to partially support the hypothesis of “rich get richer”: because college students who have good social behavior are inclined to present more self-information on SNSs, and receive more positive feedback through honest self-presentation (Kraut et al., 2002; Reer & Krämer, 2017). Now it is widely believed that people who are more sociable make better use of the opportunities provided by SNSs to strengthen their social ties (Ross et al., 2009). In addition, individuals with low self-esteem usually have cognitive bias of rejecting information: they not only show less defense against negative information, but also accept more negative information (Zhou et al., 2018), which may discount the positive association of their honest self-presentation with perceived positive feedback to some degree. By contrast, people with high self-esteem play an active part in interpersonal communication (Sampthirao, 2016). Therefore, individuals with high self-esteem are more likely to get social feedback after their honest self-presentation on SNSs than their counterparts. Even so, more honest self-presentation on SNSs still brought significantly more positive feedback for those low self-esteem individuals.

However, the result about life satisfaction was not the case in that only low self-esteem college students benefited from their honest self-presentation while their counterparts did not. There may be several reasons. On the one side, according to the self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987), when those low self-esteem individuals honestly present themselves, they will experience small discrepancies between their true self-states and ideal self-states and less negative emotions, which helps improve their life satisfaction. More than that, they can be more clear about their self-concepts regarding social anxiety (Orr & Moscovitch, 2015) and honest self-disclosure which enables them to express themselves and buffer negative feelings (Kim & Dindia, 2011). On the other side, low self-esteem may be seen as an act of sincerity when low self-esteem individuals presenting more honest self on SNSs, which will help them receive the audience’s likes (Schlenker, 1980), which will further result in a noticeable rise in life satisfaction. By contrast, people with high self-esteem are very clear about and believe in themselves and their selves are relatively free of influence of external social appraisal (Wood & Forest, 2016). Moreover, because self-esteem acts as a “buffer”, people with high self-esteem do not fluctuate greatly in terms of emotional adaptation (Arndt & Goldenberg, 2002). Thus, high self-esteem individuals always perceive more stable and higher life satisfaction than their counterparts, as found in the present study. It is still important to point out that, however, low self-esteem individuals seemed to benefit more from honest self-presentation on SNSs in terms of increased life satisfaction.

Limitations and future directions

There still are some limitations in the current study. First, in line with previous research (An et al., 2020; Liu & Brown, 2014), we focused on the overall frequency of positive feedback without distinguishing the roles of different specific positive feedback (e.g., likes, positive comments, or caring emojis). Future research could further explore the different associations of more specific types of positive online feedback with people’s well-being. Second, we did not sufficiently address the possible impact of SNS usage time and the number of SNS friends on the current results. Future studies should consider them as control variables to obtain more comprehensive and convincing findings. Third, we used a series of self-report questionnaires which may yield inaccurate measures because participants’ answers on some items are easily affected by social desirability. Therefore, future research should take other methods into account, such as evaluations by others and content analysis of SNSs accounts of participants to better understand the association of different strategies of self-presentation of college students’ life satisfaction and to improve the findings’ ecological validity. Fourth, we used a cross-sectional design which can not draw any causal conclusion. Future designs could benefit by implementing experimental manipulations that directly facilitate participants’ interactions on SNSs to test more causal models between self-presentation and life satisfaction. Finally, we used a small sample coming from only one university in China which limited its representativeness and the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should recruit a more diverse sample to provide new evidence.

Conclusions and implications

The current study provides valuable information by highlighting the positive role of honest self-presentation and the strength of positive online feedback for everyone on perceived life satisfaction, as well as the important moderating effect of self-esteem. We found that different strategies of self-presentation on SNSs was differently linked to college students’ life satisfaction and positive online feedback was a crucial mediator in such relationships. We also found that honest rather than positive self-presentation on SNSs was conducive to life satisfaction, particularly for those low self-esteem ones.

These findings have potential practical implications as well. First, the findings suggest that honest rather than positive self-presentation would be a better choice for anybody on SNSs to improve life satisfaction. They are particularly instructive for individuals in a special period, such as a home isolation period for the prevention of COVID-19, who reduce real-world social connections and turn to Internet for happiness. Second, they may be especially meaningful for individuals who are in low self-esteem because presenting more honest selves will particularly benefit their life satisfaction. Certainly, promoting self-esteem should have more fundamental benefits for happiness.

Authors' contributions

Lumei Tian constructed and designed this study, and substantially modified the manuscript. Pengyan Dai and Ruonan Zhai critically modified the manuscript as well. Jieling Cui collected the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (No. 16BSH103).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Shandong Normal University. The procedures used in this study conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors consented to the submission of the manuscript to the journal.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aljasir S, Bajnaid A, Elyas T, Alnawasrah M. Themes of Facebook status updates and levels of online disclosure: The case of university students. International Journal of Business Administration. 2017;8(7):80–97. doi: 10.5430/ijba.v8n7p80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An, R., Jiang, Y., & Bai, X. (2020). The relationship between adolescent social network use and loneliness: Multiple mediators of online positive feedback and positive emotions (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28(4), 824–833. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.04.036

- Arndt, J., & Goldenberg, J. L. (2002). From threat to sweat: The role of physiological arousal in the motivation to maintain self-esteem. In A. Tesser & D. A. Stapel, & J. V. Wood (Eds.), Self and motivation: Emerging psychological perspectives (pp. 43–69). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/10448-002

- Bareket-Bojmel L, Moran S, Shahar G. Strategic self-presentation on Facebook: Personal motives and audience response to online behavior. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;55:788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Tice DM, Hutton DG. Self-presentational motivations and personality differences in self-esteem. Journal of Personality. 1989;57(2):547–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb02384.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bazarova, N. N., Choi, Y. H., Schwanda Sosik, V., Cosley, D., & Whitlock, J. (2015). Social sharing of emotions on Facebook: Channel differences, satisfaction, and replies. In proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work & social computing (pp. 154–164). ACM Press. 10.1145/2675133.267529

- Bermack, B. (2014). Interpersonal relationships and life satisfaction among information technology professionals (Publication No.3644069) [Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Bij de Vaate AJD, Veldhuis J, Konijn EA. How online self-presentation affects well-being and body image: A systematic review. Telematics and Informatics. 2019;47:101361. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2019.101316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J, Margraf J. I present myself and have a lot of Facebook-friends-Am I a happy narcissist!? Personality and Individual Differences. 2019;148:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia J, Bierhoff HW, Rohmann E, Raeder F, Margraf J. The relationship between narcissism, intensity of Facebook use, Facebook flow and Facebook addiction. Addictive Behaviors Reports. 2020;11:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brashers DE, Neidig JL, Goldsmith DJ. Social support and the management of uncertainty for people living with HIV or AIDS. Health Communication. 2004;16(3):305–331. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1603_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JJ, Holmes JG, Vorauer JD. When self-disclosure goes awry: Negative consequences of revealing personal failures for lower self-esteem individuals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(1):217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carson SH, Langer EJ. Mindfulness and self-acceptance. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2006;24(1):29–43. doi: 10.1007/s10942-006-0022-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chai, H., Chu, X., Niu, G., Sun, X., Lian, S., & Yao, L. (2018). Self-disclosure on social networking sites and adolescents’ life satisfaction: A moderated mediation model (in Chinese). Journal of Psychological Science, 41(5), 81–87. 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20180512

- Chan, T. K. H. (2021). “Does self-disclosure on social networking sites enhance well-being? The role of social anxiety, online disinhibition, and psychological stress”, In Z. W. Y. Lee, T. K. H. Chan, & C. M. K. Cheung (Eds.), Information Technology in Organisations and Societies: Multidisciplinary Perspectives from AI to Technostress (pp. 175–202). Emerald Publishing. 10.1108/978-1-83909-812-320211007

- Chen L, Gong T, Kosinski M, Stillwell D, Davidson RL. Building a profile of subjective well-being for social media users. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0187278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’agata MT, Holden RR. Self-concealment and perfectionistic self-presentation in concealment of psychache and suicide ideation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2018;125:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Colvin CR, Pavot WG, Allman A. The psychic costs of intense positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(3):492–503. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.3.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Lucas RE, Oishi S. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. The handbook of positive psychology. Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Duan W, He C, Tang X. Why do people browse and post on WeChat moments? Relationships among fear of missing out, strategic self-presentation, and online social anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2020;23(10):708–714. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forest AL, Wood JV. When social networking is not working: Individuals with low self-esteem recognize but do not reap the benefits of self-disclosure on Facebook. Psychological Science. 2012;23(3):295–302. doi: 10.1177/0956797611429709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, K., Derlega, V. J., & Mathews, A. (2006). Self-Disclosure in Personal Relationships. In A. L. Vangelist & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships (pp. 409–428). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/cbo9780511606632.023

- Greitemeyer T, Mügge DO, Bollermann I. Having responsive Facebook friends affects the satisfaction of psychological needs more than having many Facebook friends. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2014;36(3):252–258. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2014.900619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve R, Watkinson J. The psychological benefits of being authentic on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2016;19(7):420–425. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve R, March E, Watkinson J. Inauthentic self-presentation on Facebook as a function of vulnerable narcissism and lower self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020;102:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Social networking addiction: An overview of preliminary findings. In K. P. Rosenberg & L. Curtiss Feder (Eds.), Behavioral addictions: Criteria, evidence, and treatment (pp. 119–141). Elsevier Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-407724-9.00006-9

- Haber M, Cohen J, Lucas T, Baltes B. The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;39:133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton KN, Lu W. Beyond the power of networks: Differentiating network structure from social media affordances for perceived social support. New Media & Society. 2015;19(6):861–879. doi: 10.1177/1461444815621514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Heng S, Zhou Z, Lei Y, Niu G. The impact of actual-ideal self-discrepancies on adolescents' game addiction: The serial mediation of avatar identification and flow experience (in Chinese) Studies of Psychology and Behavior. 2018;16(2):111–118. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2018.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review. 1987;94(3):319–340. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian M, Grieve R. When Facebook is easier than face-to-face: Social support derived from Facebook in socially anxious individuals. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;59:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson CA, Luchner AF. Self-presentation mediates the relationship between Self-criticism and emotional response to Instagram feedback. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017;133:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang W, Bucy EP, Cho J. Self-esteem moderates the influence of self-presentation style on Facebook users' sense of subjective well-being. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;85:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jian RR, Li S. Seeking help from weak ties through mediated channels: Integrating self-presentation and norm violation to compliance. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;87:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Bai X, Qi S, Wu Y. The effect of adolescents’ social networking on social anxiety: The mediating role of online positive feedback and self-esteem (in Chinese) Chinese Journal of Special Education. 2019;8:76–81. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-3728.2019.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin B, Pena JF. Mobile communication in romantic relationships: Mobile phone use, relational uncertainty, love, commitment, and attachment styles. Communication Reports. 2010;23(1):39–51. doi: 10.1080/08934211003598742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Dewall CN, Masten CL, Pond RS, Jr, Powell C, Combs D, Schurtz DR, Farmer AS. Who is most vulnerable to social rejection? The toxic combination of low self-esteem and lack of negative emotion differentiation on neural responses to rejection. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kereste G, Tulhofer A. Adolescents’ online social network use and life satisfaction: A latent growth curve modeling approach. Computers in Human Behavior. 2019;104:106–187. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.106187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Baek YM. When is selective self-presentation effective? An investigation of the moderation effects of “self-esteem” and “social trust”. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2014;17(11):697–701. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Dindia K. Online self-disclosure: A review of research. In: Wright KB, Webb LM, editors. Computer-mediated communication in personal relationships. Peter Lang Publishing; 2011. pp. 156–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lee JR. The Facebook paths to happiness: Effects of the number of Facebook friends and self-presentation on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2011;14(6):359–364. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko HC, Kuo FY. Can blogging enhance subjective well-being through self-disclosure? Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2009;12(1):75–79. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F, You X. Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Social Indicators Research. 2013;110:271–279. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9930-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R, Kiesler S, Boneva B, Cummings J, Helgeson V, Crawford A. Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues. 2002;58(1):49–74. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;14(3):311–328. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14030311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebacq T, Dujeu M, Méroc E, Moreau N, Pedroni C, Godin I, Castetbon K. Perceived social support from teachers and classmates does not moderate the inverse association between body mass index and health-related quality of life in adolescents. Quality of Life Research. 2019;28(4):895–905. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-2079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DKL, Borah P. Self-presentation on Instagram and friendship development among young adults: A moderated mediation model of media richness, perceived functionality, and openness. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020;103:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Lee J, Kwon S. Use of social-networking sites and subjective well-being: A study in South Korea. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, & Social Networking. 2011;14(3):151–155. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Kim YJ, Ahn J. How do people use Facebook features to manage social capital? Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;36:440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Jiang Y, Zhang B. The influence of loneliness on problematic mobile social networks usage for adolescents: The role of interpersonal distress and positive self presentation (in Chinese) Journal of Psychological Science. 2018;41(5):1117–1123. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20180514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Coduto KD, Song C. Comments vs. One-click reactions: Seeking and perceiving social support on social network sites. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 2020;64(5):777–793. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2020.1848181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Utz S. Self-disclosure on SNS: Do disclosure intimacy and narrativity influence interpersonal closeness and social attraction? Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;70:426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Brown BB. Self-disclosure on social networking sites, positive feedback, and social capital among Chinese college students. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;38:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Sun X, Zhou Z, Niu G, Kong F, Lian S. The effect of honest self-presentation in online social network sites on life satisfaction: The chain mediating role of online positive feedback and general self-concept (in Chinese) Journal of Psychological Science. 2016;39(2):406–411. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20160223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Hancock J. Self-disclosure and social media: Motivations, mechanisms and psychological well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2019;31:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Maddux JE. Subjective well-being and life satisfaction: An introduction to conceptions, theories, and measures. In: Maddux JE, editor. Subjective well-being and life satisfaction. Routledge; 2018. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Manago AM. Media and the development of identity. In: Scott R, Kosslyn S, editors. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Meeus A, Beullens K, Eggermont S. Like me (please?): Connecting online self-presentation to pre- and early adolescents’ self-esteem. New Media & Society. 2019;21(3):1–18. doi: 10.1177/1461444819847447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler A, Scheithauer H. The long-term benefits of positive self-presentation via profile pictures, number of friends and the initiation of relationships on Facebook for adolescents’ self-esteem and the initiation of offline relationships. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017;8:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler A, Scheithauer H. Association of self-presentational strategies on Facebook and positive feedback in adolescence - A two-study approach. International Journal of Developmental Sciences. 2018;12(3):1–18. doi: 10.3233/DEV-180246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michikyan M, Subrahmanyam K, Dennis J. Can you tell who I am? Neuroticism, extraversion, and online self-presentation among young adults. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;33:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi RL, Prestin A, So J. Facebook friends with (health) benefits? Exploring social network site use and perceptions of social support, stress, and well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16(10):721–727. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni A, Hofmann SG. Why do people use Facebook? Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;52(3):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuliep JW. The relationship among intercultural communication apprehension, ethnocentrism, uncertainty reduction, and communication satisfaction during initial intercultural interaction: An extension of anxiety and uncertainty management (AUM) Theory. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research. 2012;41(1):1–16. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2011.623239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu G, Bao N, Zhou Z, Fan C, Kong F, Sun X. The impact of self-presentation in online social network sites on life satisfaction: The effect of positive affect and social support (in Chinese) Psychological Development and Education. 2015;31(5):563–570. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.05.07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oh HJ, Ozkaya E, LaRose R. How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;30:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ollier-Malaterre A, Rothbard NP, Berg JM. When worlds collide in cyberspace: How boundary work in online social networks impacts professional relationships. Academy of Management Review. 2013;38(4):645–669. doi: 10.5465/amr.2011.0235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orr EMJ, Moscovitch DA. Blending in at the cost of losing oneself: Dishonest self-disclosure erodes self-concept clarity in social anxiety. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology. 2015;6(3):278–296. doi: 10.5127/jep.044914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palermiti AL, Servidio R, Bartolo MG, Costabile A. Cyberbullying and self-esteem: An Italian study. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;69:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. Microblogging, friendship maintenance, and life satisfaction among university students: The mediatory role of online self-disclosure. Telematics and Informatics. 2018;35(8):2232–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2018.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2018). Social media use in 2018. https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor CL, Linley PA, Maltby J. Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2009;10(5):583–630. doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9110-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reer F, Krämer NC. The connection between introversion/extroversion and social capital outcomes of playing world of warcraft. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2017;20(2):97–103. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke L, Trepte S. Authenticity and well-being on social network sites: A two-wave longitudinal study on the effects of online authenticity and the positivity bias in SNS communication. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;30:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ross C, Orr ES, Sisic M, Arseneault JM, Simmering MG, Orr RR. Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009;25(2):578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2008.12.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampthirao, P. (2016). Self-concept and interpersonal communication. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 3(3). 10.25215/0303.115

- Satici SA, Uysal R. Well-being and problematic Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;49:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker BR, Leary MR. Social anxiety and self-presentation: A conceptualization model. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;92(3):641–669. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.92.3.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker, B. R. (1980). Impression management: The self-concept, social identity, and interpersonal relations. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

- Schlosser AE. Self-disclosure versus self-presentation on social media. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2020;31:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scissors, L., Burke, M., & Wengrovitz, S. (2016, February). What’s in a Like? Attitudes and behaviors around receiving likes on Facebook. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing—CSCW’16 (pp. 1499–1508). ACM Press. 10.1145/2818048.2820066

- Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, Delsing M, Bogt TF, Meeus WH. Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: The role of perceived friendship quality. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32(4):819–833. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo M, Kim J, Yang H. Frequent interaction and fast feedback predict perceived social support: Using crawled and self-reported data of Facebook users. Journal of Computer Communication. 2016;21:282–297. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahyad S, Besharat MA, Asadi M, Alipour AS, Miri M. The relation of attachment and perceived social support with life satisfaction: Structural equation model. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2011;15:952–956. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass JG, Bagwell A, Patry JM, Dengah HJFI, Smarr-Foster C, Van Oostenburg M, Lacy MG. The partial truths of compensatory and poor-get-poorer internet use theories: More highly involved videogame players experience greater psychosocial benefits. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;78:10–25. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.26701.13286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sosik VS, Bazarova NN. Relational maintenance on social network sites: How Facebook communication predicts relational escalation. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;35:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Chai H, Niu H, Cui X, Lian S, Tian Y. The effect of self-disclosure on social networking site on adolescents’ loneliness: A moderated mediation model (in Chinese) Psychological Development and Education. 2017;33(4):477–486. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2017.04.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sung Y, Lee JA, Kim E, Choi SM. Why we post selfies: Understanding motivations for posting pictures of oneself. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;97:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DA. The development of interpersonal relationships: Social penetration processes. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1968;75(1):79–90. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1968.9712476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DA, Altman I. Communication in interpersonal relationships: Social penetration processes. In: Roloff ME, Miller GR, editors. Interpersonal processes: New directions in communication research. Sage Publications Inc; 1987. pp. 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Tazghini S, Siedlecki KL. A mixed method approach to examining Facebook use and its relationship to self-esteem. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(3):827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L. Shortcoming and merits of Chinese version of Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale (in Chinese) Psychological Exploration. 2006;26(2):88–91. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-5184.2006.02.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toma CL. Feeling better but doing worse: Effects of Facebook self-presentation on implicit self-esteem and cognitive task performance. Media Psychology. 2013;16(2):199–220. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2012.762189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey C, O'Reilly G. Associations of self-presentation on Facebook with mental health and personality variables: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2017;20(10):587–595. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler JM, Adams KE, Kearns P. Self-presentation and subjective well-being. In: Maddux JE, editor. Subjective well-being and life satisfaction. Routledge; 2018. pp. 355–391. [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS. “I share, therefore I am”: Personality traits, life satisfaction, and Facebook check-ins. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2013;16(12):870–877. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Shi S. Preparation for “life satisfaction scales applicable to college students (CSLSS)” (in Chinese) Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science. 2003;12:199–201. [Google Scholar]

- Wenninger, H., Krasnova, H., & Buxmann, P. (2014, October). Activity matters: Investigating the influence of Facebook on life satisfaction of teenage users [Paper presentation]. ECIS 2014 Proceedings-22nd European Conference on Information Systems, Tel Aviv, Israel.

- Wise K, Alhabash S, Park H. Emotional responses during social information seeking on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2010;13(5):555–562. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohn DY, Larose R. Effects of loneliness and differential usage of Facebook on college adjustment of first-year students. Computers & Education. 2014;76(7):158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wohn DY, Carr CT, Hayes RA. How affective is a "like"?: The effect of paralinguistic digital affordances on perceived social support. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2016;19(9):562–566. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JV, Forest AL. Self-protective yet self-defeating: The paradox of low self-esteem people's self-disclosures. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2016;53:131–188. doi: 10.1016/bs.aesp.2015.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright EJ, White KM, Obst PL. Facebook false self-presentation behaviors and negative mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2018;21(1):40–49. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W. Social network site use, mobile personal talk and social capital among teenagers. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;41:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Brown BB. Online self-presentation on Facebook and self development during the college transition. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45(2):402–416. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0385-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]