Abstract

Purified native Tromp1 was subjected to mass spectrometric analysis in order to determine conclusively whether this protein possesses a cleaved or uncleaved signal peptide. The molecular masses of Tromp1, three Treponema pallidum lipoproteins, and a bovine serum albumin (BSA) control were determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. The molecular masses of all of the T. pallidum lipoproteins and BSA were within 0.7% of their respective calculated masses. The molecular mass of Tromp1 was 31,510 Da, which is consistent with a signal-less form of Tromp1, given a calculated mass of unprocessed Tromp1 of 33,571 Da, a difference of 2,061 Da (a 6.5% difference). Purified native Tromp1 was also subjected to MALDI-TOF analysis in comparison to recombinant Tromp1 following cyanogen bromide cleavage, which further confirmed the identity of Tromp1 and showed that native Tromp1 was not degraded at the carboxy terminus. These studies confirm that Tromp1 is processed and does not contain an uncleaved signal peptide as previously reported.

Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum, the etiologic agent of venereal syphilis, has for over a decade been known to possess a unique outer membrane containing an extremely low density of membrane-spanning surface-exposed protein (17, 20). It is believed that these T. pallidum rare outer membrane proteins, termed TROMPs (6), are the only surface-exposed antigens on this organism and therefore represent the key surface targets for protective host immune mechanisms which develop during syphilitic infection.

In our previous attempts to identify potential TROMP candidates, two proteins of 31 and 28 kDa were found to be markedly enriched in outer membranes isolated from T. pallidum (5). The 31-kDa protein, termed Tromp1, was found to have properties consistent with those of an outer membrane porin protein, including amphiphilicity following phase separation in the detergent Triton X-114 and electrical conductivity when analyzed in planar lipid bilayers (3). It was also determined that recombinant Tromp1, when expressed, exported, and targeted to Escherichia coli outer membranes, also exhibited porin activity similar to that measured for native Tromp1 (4). Tromp1 has also been found to have 26 to 28% sequence identity to adhesin proteins found in the streptococcal family (12), suggesting a potential role as a virulence determinant.

While our studies have shown that Tromp1 is a porin protein, recent studies by Hardham et al. (10) have found that Tromp1 is also part of an operon which possesses similarities to ABC transporter systems and that Tromp1, also called TroA in these studies, has 28% sequence identity to periplasmic binding proteins of these ABC transporter operons. This apparent disparity between the demonstrated outer membrane location and porin activity of Tromp1 and the suggestion that TroA is a periplasmic binding protein from homology comparisons is an area of research which is currently being investigated. It has also been recently reported by Akins et al. (2) that Tromp1 possesses an uncleaved signal peptide, which these investigators conclude anchors Tromp1 to the inner membrane and accounts for its demonstrated hydrophobicity. Because Tromp1 possesses an N terminus blocked to Edman sequencing, the conclusion that Tromp1 is uncleaved was based upon a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)-based size comparison of native Tromp1 and that generated from an in vitro translation product. Thus, the findings of these studies have resulted in one current view that Tromp1 is not an outer membrane protein but rather a periplasmic binding protein anchored to the inner membrane by an uncleaved signal peptide.

In order to begin to address the controversy surrounding Tromp1, we have isolated and purified the hydrophobic form of native Tromp1 for mass spectrometric analysis to determine conclusively whether this protein possesses a cleaved or uncleaved signal peptide. The findings reported here demonstrate conclusively that Tromp1 has a cleaved signal peptide and is therefore not anchored to the inner membrane by an uncleaved signal peptide as previously reported (2). Also implicit from these findings is that the hydrophobicity of Tromp1 is not due to an uncleaved signal peptide, as reported previously, but is rather an inherent property of this protein, which we believe is consistent with its outer membrane location.

Isolation and purity of native Tromp1 and three other T. pallidum hydrophobic proteins.

Native hydrophobic forms of Tromp1, the 47-kDa lipoprotein, the MglB homolog lipoprotein (41 kDa), and the TmpC lipoprotein (35 kDa) were isolated from approximately 2 × 1011 T. pallidum cells as follows. T. pallidum subsp. pallidum (Nichols strain) was extracted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2) from 20 intratesticularly infected rabbits as previously described (13). Approximately 800 ml of treponemal extract was centrifuged twice at 400 × g for 10 min each time in order to pellet gross tissue debris and then at 20,000 × g for 30 min in order to pellet the treponemes. The treponemal pellet was washed in 200 ml of PBS and then recentrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min. The final treponemal pellet was resuspended in 26 ml of ice-cold PBS to which was added 4 ml of ice-cold 10% hydrogenated Triton X-114 (Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif.) to yield a final detergent concentration of 2%. The suspension was next incubated on a rocker at 4°C for 2 h in order to solubilize the outer membrane. After this incubation, the suspension was centrifuged at 20,000 × g in order to remove T. pallidum protoplasmic cylinders and the supernatant was removed and warmed to 37°C for 5 min, which resulted in cloud formation of the detergent. The suspension was then centrifuged at 3,000 × g in order to yield separated hydrophobic (bottom) and aqueous (top) phases. The hydrophobic phase was recovered (approximately 2 ml), extracted twice with 40 ml of warmed PBS, and then centrifuged as described above. The final extracted hydrophobic phase (approximately 2 ml) was then combined with 30 ml of ice-cold acetone, incubated for 2 h at 4°C, and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min to recover precipitated protein. The protein pellet was then subjected to two-dimensional SDS-PAGE as previously described (5). After electrophoresis, proteins in the gel were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) as previously described (18), stained with 0.2% amido black in water for 20 min, and destained by using distilled water. Protein spots corresponding to Tromp1, the 47-kDa lipoprotein, the MglB lipoprotein, and the TmpC lipoprotein were identified based upon their respective molecular weights and isoelectric points as previously described (15).

In order to elute the proteins from the membrane, the section of the PVDF membrane corresponding to each of these proteins was cut out and placed in 250 μl of 2% SDS–1% hydrogenated Triton X-100–50 mM Tris, pH 9.0 (1). The suspensions were incubated on a shaker for 16 h at room temperature and then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min. Samples from each of the supernatants were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) and identified by silver staining (Bio-Rad). The total amount of protein recovered from each of the eluted samples was estimated to be 3 to 5 μg.

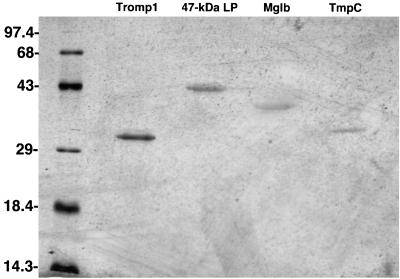

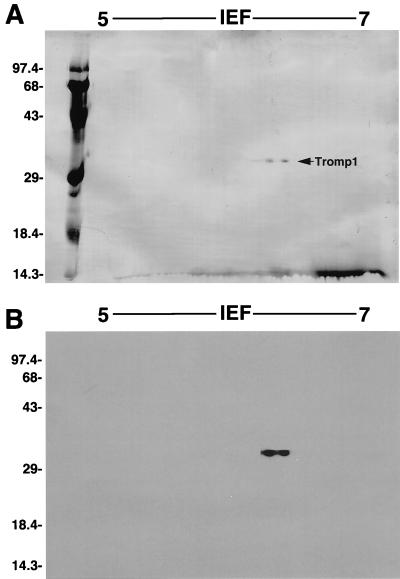

As shown in Fig. 1, 1/25 (approximately 200 ng) of each sample analyzed showed a single band corresponding to a molecular mass consistent with that of Tromp1 (31 kDa), the 47-kDa lipoprotein, the 41-kDa MglB homolog lipoprotein, and the 35-kDa TmpC lipoprotein. In addition, Tromp1 was further analyzed by two-dimensional immunoblotting using specific anti-Tromp1 serum and enhanced chemiluminescence as previously described (4). As shown in Fig. 2, the amido black-stained immunoblot showed a doublet at 31 kDa (Fig. 2A) corresponding to the molecular mass and pI (6.6) reported previously for Tromp1 (3). The stained 31-kDa doublet reacted specifically with anti-Tromp1 serum (Fig. 2B), confirming that the isolated protein was Tromp1.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE, followed by silver staining, of isolated native Tromp1, the 47-kDa lipoprotein (47-kDa LP), the 41-kDa Mglb homolog lipoprotein (Mglb), and the 35-kDa TmpC lipoprotein (TmpC). Approximately 200 ng of each isolated protein was combined with sample buffer containing 2% SDS and 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and boiled prior to electrophoresis. The values on the left indicate the positions of molecular weight standards (103).

FIG. 2.

Two-dimensional immunoblot analysis of isolated native Tromp1. Approximately 500 ng of isolated native Tromp1 was separated in the first dimension by denaturing isoelectric focusing (IEF) and then in the second dimension by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane. (A) Amido black-stained PVDF membrane showing the detection of only Tromp1. (B) Membrane in panel A probed with specific anti-Tromp1 serum, confirming the detection of Tromp1. The values on the left indicate the positions of molecular weight standards (103).

MALDI mass spectrometry of purified native Tromp1.

To obtain an accurate measurement of the molecular mass of Tromp1, its mass spectrum was recorded by using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometry. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was performed by using a Voyager RP machine (Perceptive Biosystems, Framingham, Mass.) operating in linear mode. The three other T. pallidum membrane lipoproteins and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were also analyzed as controls. For sample preparation, 0.3 μl of chloroform-methanol-precipitated protein (21) (1 to 10 pmol) dissolved in 60% HCOOH (2 to 4 μl) was mixed with 0.5 μl of a 20-mg/ml matrix solution (2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid; Aldrich, Milwaukee, Wis.) in 50% HCOOH–50% isopropanol and dried immediately on the MALDI plate.

The measured masses of the lipoproteins and BSA, as well as their calculated masses based upon their gene sequences and posttranslational modifications, are presented in Table 1. Reasonable agreement between the measured and calculated masses was obtained for the three control lipoproteins and BSA, with discrepancies of 0.7% or less. Mass accuracy of 0.1% is expected for the MALDI-TOF technique using internal calibration, as we used for these experiments, and thus it was concluded that the proteins had been modestly modified during the isolation process. Methionine oxidation and acrylamide adducts of cysteine are expected on proteins exposed to SDS-PAGE. Nevertheless, the measured masses support the structural assignment of N-palmitoyl, S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-propyl] to the N-terminal cysteine of these lipoproteins and support translational termination at the first stop codon in the case of the 47-kDa lipoprotein.

TABLE 1.

Molecular masses of T. pallidum proteins measured by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

| Protein | Molecular mass (Da)

|

% Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Measureda | ||

| Uncleaved Tromp1 | 33,571 | 31,510 | 6.5 |

| Tromp1 cleaved between amino acids 19 and 20 | 31,491 | 0.1 | |

| Tromp1 cleaved after THA | 31,182 | 1.0 | |

| Tromp1 cleaved after AFG | 30,977 | 1.7 | |

| Tromp1 cleaved after AAA | 30,433 | 3.5 | |

| TmpCb | 36,278 | 36,350 | 0.2 |

| Mglb homologb | 41,265 | 41,560 | 0.7 |

| 47-kDa 1st stop codonb | 46,541 | 46,790 | 0.5 |

| 47-kDa 2nd stop codonb | 47,642 | 46,790 | 1.8 |

| BSA | 66,430 | 66,431 | <0.01 |

Done with Voyager RP in linear mode.

N-terminal cysteine is N-palmitoyl, S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-propyl].

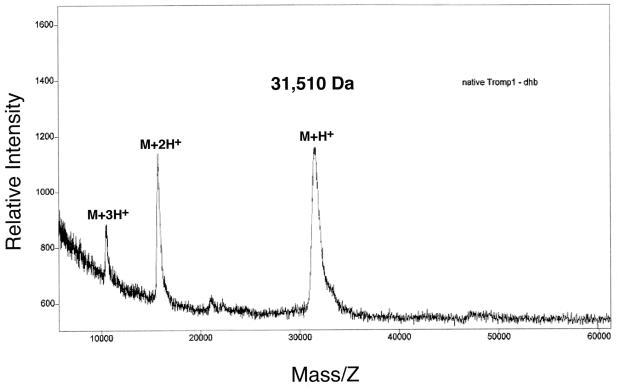

As shown in Fig. 3, the MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of Tromp1 showed strong ions for the singly charged protein (M+H+) and the doubly charged ion (M+2H+); the triply charged ion was also visible (M+3H+). The measured mass of Tromp1 was found to be, whether in the presence or absence of an internal BSA standard, 31,510 Da (Fig. 3), which is in disagreement with the calculated mass of 33,571 Da for an unprocessed translation product (6.5% error). This mass determination for Tromp1 was consistent and reproducible following several separate experiments. A much closer agreement between the measured and calculated masses was obtained for a cleaved Tromp1 translation product (Table 1). A better match between masses is achieved if the THA leader peptidase I cleavage site in the Tromp1 signal peptide is invoked, although the calculated mass (31,182 Da) is lower than the measured mass (1% error). Arbitrary cleavage N terminal to Thr20 of the THA motif improves the match considerably (0.1% error). These results demonstrate that the native Tromp1 protein is cleaved to size from its original translation product. However, the level of accuracy in this analysis precludes assignment of the true N terminus and, formally, cleavage of the C terminus must also be considered.

FIG. 3.

Molecular mass spectrum of native Tromp1. The mass spectrum was recorded with a Perceptive Biosystems Voyager RP with laser intensity sufficient to achieve efficient ionization. The singly and doubly charged ions of BSA were used to calibrate the mass spectrometer, and similar results were obtained whether an internal calibration was used or not. dhb, 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid matrix solution.

MALDI mass spectrometric comparison of native and recombinant Tromp1.

Native Tromp1 and a signal-less form of recombinant Tromp1 were treated with CNBr, and the fragments were probed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in order to compare the observed peptide maps with theoretical ones based upon the known gene sequence and potential cleavage sites.

A signal-less form of recombinant Tromp1, corresponding to the signal peptide cleavage site of alanine-phenylalanine-glycine (AFG), was generated as follows. An N-terminal primer (5′-CGCCATATGAGCAAGGATGCCGCAGCAGAC-3′; the underlined region is the tromp1 gene sequence) corresponding to signal peptide cleavage after AFG was generated containing an NdeI restriction endonuclease site at the 5′ end (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). This construct results in a single methionine residue placed ahead of the site of signal peptide cleavage for the purpose of translation. A C-terminal primer consisting of 5′-CGCGGATCCCTAGCGAGCCAACGCAGCAA-3′ and corresponding to the end of the tromp1 gene was generated containing a BamHI restriction endonuclease site at the 5′ end. A PCR was performed with these primers as described previously (4). The tromp1 PCR product was ligated into pET17b (Novagen, Inc.), which had previously been digested with NdeI and BamHI. The resulting construct was transformed into E. coli BL21 DE3/pLysE (Novagen, Inc.) using cells made competent by CaCl2. Expression and fast-performance liquid chromatography purification of recombinant Tromp1 were performed as described previously (4).

For CNBr treatment of native and recombinant Tromp1, chloroform-methanol-precipitated protein pellets were dissolved in 35 μl of a 1-g/ml saturated solution of CNBr (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in 90% formic acid (Fisher, Fair Lawn, N.J.) to which was added 15 μl of water. A final CNBr/Met molar ratio of 500 was exceeded in all digestions. CNBr digestion was carried out for 4 h in the dark at room temperature. The reaction mixture was then dried (SpeedVac), redissolved in 250 μl of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.), and dried again. For MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, 0.3 μl of the CNBr-digested samples (1 to 2 pmol) dissolved in 60% HCOOH (2 to 4 μl) was mixed with 0.5 μl of a 10-mg/ml matrix solution (α-hydroxycinnamic acid; Aldrich) in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid–70% CH3CN and dried immediately on the MALDI plate. Bovine insulin was used as a standard.

Table 2 summarizes the results of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometric analysis of CNBr-treated recombinant and native Tromp1. Central to the interpretation of the mapping experiments is the appearance of peptides derived from the N and C termini of the protein. The C-terminal peptide (peptide 8) was observed in both cases, providing conclusive evidence that any processing was not at the C terminus. Internal peptides (peptides 3, 4, and 6) were well represented in both proteins, proving that the protein analyzed was Tromp1. In addition, the set of the native Tromp1 peptides used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information protein databases was found to match only Tromp1 and TroA, confirming that the peptides analyzed were from Tromp1. In native Tromp1, N-terminal data set peptides with masses agreeing well with those of peptide 2 and hybrid peptide 2/3 were observed, whereas only peptide 2 was observed in the recombinant protein. In the case of native Tromp1, the masses of the peptides that were observed support a model with cleavage between residues 19 and 20 generating a novel set of CNBr fragments that were not observed in the map of the uncleaved protein.

TABLE 2.

Peptide mapping by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of native and recombinant Tromp1 after CNBr cleavage

| Peptide no. | Calculated mass(es) (Da) of CNBr-cleaved Tromp1 peptide(s)a

|

Measured mass (Da) of CNBr-cleaved Tromp1 peptide(s) (% difference)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncleaved | Cleaved | Recombinantb | Native | |

| 1 | 1,502 | NDe | ||

| 1 + 2 | 4,205 | ND | ||

| 2 | 2,659 | 1,727, 1,931, 2,241c | 1,836 (1)d | 2,194 (27, 14, 2) |

| 2 + 3 | 4,650 | 3,718, 3,923, 4,232c | ND | 4,190 (13, 7, 1) |

| 3 | 1,946 | 1,946 | 1,946 (0) | 1,948 (0.1) |

| 4 | 3,835 | 3,835 | 3,836 (<0.1) | 3,835 (0) |

| 5 | 15,077 | 15,077 | 15,081 (<0.1) | ND |

| 6 | 5,526 | 5,526 | 5,526 (0) | 5,525 (<0.1) |

| 6 + 7 | 6,769 | 6,769 | 6,718 (<0.8) | 6,769 (0) |

| 7 | 1,197 | 1,197 | ND | ND |

| 8 | 1,495 | 1,495 | 1,494 (<0.1) | 1,494 (<0.1) |

The Peptide Mass program (9a) was used to calculate average peptide masses (M+H+) based upon natural isotopic abundance. Limited partial cleavage is considered, and internal methionine sulfoxide was used to calculate the mass rather than methionine delivered by Peptide Mass (thus, hybrids are 16 Da larger than the sizes reported by this program for peptides with C-terminal homoserine lactone). Peptides are numbered from the N to the C terminus.

Recombinant Tromp1 was constructed without a signal peptide and expressed with a start Met following the putative cleavage motif of alanine-phenylalanine-glycine (AFG).

Calculated masses of the N-terminal peptide of signal-less Tromp1 cleaved at AFG (1,727 and 3,718 Da), THA (1,931 and 3,923 Da), and N terminal to Thr20 (2,241 and 4,232 Da).

Percent difference was calculated against peptide 2 cleaved at AFG plus the N-terminal Met (1,858 Da).

ND, not detected.

The results presented here, in contrast to the previous report by Akins et al. (2), conclusively demonstrate that Tromp1 has a processed and cleaved signal peptide. Mass spectrometry analysis of native Tromp1 resulted in a molecular mass of 31,510 Da, consistent with a processed form of this protein given a calculated mass of unprocessed Tromp1 of 33,571 Da, a difference of 2,061 Da, which is the average size of a 19-residue signal peptide (19). This result was also reproducible whether an internal BSA protein control was included in or excluded from the sample containing Tromp1. Further, mass spectrometry peptide analysis of CNBr-treated Tromp1 confirmed that the sample tested was Tromp1 and that it was not degraded from the carboxy terminus. In addition, three T. pallidum lipoproteins, isolated the same way as Tromp1 from the hydrophobic phase of a Triton X-114 detergent extract, were also analyzed in order to confirm the validity of the molecular mass results obtained for T. pallidum proteins isolated by this method. The molecular masses obtained for the three lipoproteins were all within 0.7% of their calculated values given the addition for each of these lipoproteins of a covalent association of glycerol and three molecules of the fatty acid palmitate. Therefore, mass spectrometry analysis, which provides the most reliable assessment of molecular mass, has proven that native Tromp1 possesses a cleaved signal peptide.

Of the three potential leader peptidase I cleavage sites present at the carboxy terminus of the Tromp1 signal peptide, which include (from the N to the C terminus) threonine-histidine-alanine (THA), alanine-phenylalanine-glycine (AFG), and alanine-alanine-alanine (AAA), theoretical cleavage following THA results in a calculated molecular mass of the mature protein having the closest agreement with the mass spectrometry result of native Tromp1 (1% error). THA is also the cleavage site predicted for the Tromp1 signal peptide by the SignalP analysis program (14). However, given that a mass accuracy of 0.1% is expected for the MALDI-TOF technique, prediction of the cleavage site based upon this level of accuracy would place the cleavage site N terminal to the threonine of the THA motif. It is unlikely that this is the actual N terminus of the mature protein because this would require the upstream sequence of threonine-glycine-phenylalanine to be recognized as the cleavage motif, which is not a classic leader peptidase I cleavage recognition site (19).

Purified native Tromp1 and a signal-less form of recombinant Tromp1 were also analyzed in this study by mass spectrometry following CNBr cleavage. The intact-protein mass data combined with the CNBr mapping data provide overwhelming evidence that the observed protein is indeed Tromp1 and that again it is cleaved to a significantly shorter length than that predicted from the uncleaved protein. CNBr mapping data can be accommodated with cleavage between amino acids 19 and 20 or thereabout, bearing in mind the N-terminal modification implied by blockage to Edman sequencing. Definitive structural assignment of the N terminus of Tromp1 requires further biochemical analyses. Central to these analyses will be electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry, which has recently been applied to membrane proteins (23) and has, indeed, been used to measure the molecular weight of recombinant Tromp1 (22). Resolution by electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry should solve the heterogeneity of Tromp1 apparent in gels.

In the previous study by Akins et al. (2), their conclusion that Tromp1 possesses an uncleaved signal peptide was used to explain the hydrophobicity of Tromp1 and suggest its anchoring to the inner membrane. In contrast, our latest studies have indicated that the hydrophobicity of Tromp1 is due to reasons other than an uncleaved signal peptide. Further, our previous studies showed that treatment of T. pallidum with low concentrations of the nonionic detergent Triton X-114, which completely solubilizes the T. pallidum outer membrane without solubilizing the inner membrane (7, 16), resulted in the complete release of Tromp1 with no residual detection of Tromp1 in the inner membrane protoplasmic cylinder complex (3). Such findings are consistent with the idea that this hydrophobic protein has an outer membrane origin rather than being anchored to the inner membrane.

It was also reported by Akins et al. (2), who used a purified recombinant, that Tromp1 did not show any porin activity by the liposome swelling assay (8). Similarly, we have also found that with the exception of recombinant Tromp1 targeted to E. coli outer membranes (4), no soluble recombinant form of Tromp1 tested has shown porin activity when planar lipid bilayers were used. It should be emphasized, however, that this is in direct contrast to purified native Tromp1, which we have found to have consistent and reproducible porin activity following isolation by isoelectric focusing (3) and more recently by fast-performance liquid chromatography (9). We believe that the difference in this demonstrable porin activity between the native and recombinant proteins may be due to conformation.

In summary, the findings presented in this study conclusively show that native Tromp1 does, indeed, possess a processed signal peptide and is therefore an exported protein. These findings, therefore, indicate that Tromp1 is not anchored to the inner membrane and support the possibility that Tromp1 is a bona fide outer membrane protein of T. pallidum.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiao-Yang Wu for his excellent technical assistance. We also thank Kym Faull for his support and encouragement.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants AI-21352 and AI-12601 to M. A. Lovett and AI-37312 to J. N. Miller. Funds from the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-A16042) were used toward the purchase of the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer used.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aebersold R. Internal amino acid sequence analysis of proteins after in situ protease digestion on nitrocellulose. In: Matsudaira P T, editor. A practical guide to protein and peptide purification for microsequencing. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akins D R, Robinson E, Shevchenko D, Elkins C, Cox D L, Radolf J D. Tromp1, a putative rare outer membrane protein, is anchored by an uncleaved signal sequence to the Treponema pallidum cytoplasmic membrane. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5076–5086. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5076-5086.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco D R, Champion C I, Exner M M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Hancock R E W, Tempst P, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Porin activity and sequence analysis of a 31-kilodalton Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum rare outer membrane protein (Tromp1) J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3556–3562. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3556-3562.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco D R, Champion C I, Exner M M, Shang E S, Skare J T, Hancock R E W, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Recombinant Treponema pallidum rare outer membrane protein 1 (Tromp1) expressed in Escherichia coli has porin activity and surface antigenic exposure. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6685–6692. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6685-6692.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco D R, Reimann K, Skare J, Champion C I, Foley D, Exner M M, Hancock R E W, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Isolation of the outer membranes from Treponema pallidum and Treponema vincentii. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6088–6099. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6088-6099.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanco D R, Walker E M, Haake D A, Champion C I, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Complement activation limits the rate of in vitro treponemicidal activity and correlates with antibody-mediated aggregation of Treponema pallidum rare outer membrane protein (TROMP) J Immunol. 1990;144:1914–1921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham T M, Walker E M, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Selective release of the Treponema pallidum outer membrane and associated polypeptides with Triton X-114. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5789–5796. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5789-5796.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson A L, Nikaido H. Purification and characterization of the membrane-associated components of the maltose transport system from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8946–8951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Exner, M. M., D. R. Blanco, J. N. Miller, and M. A. Lovett. Unpublished data.

- 9a.ExPASy Proteomics Tools Website. 7 April 1999, revision date. [Online.] http://www.expasy.ch/tools/peptide-mass.html. [29 June 1999, last date accessed.]

- 10.Hardham J M, Stamm L V, Porcella S F, Frye J G, Barnes N Y, Howell J K, Mueller S L, Radolf J D, Weinstock G M, Norris S J. Identification and transcriptional analysis of a Treponema pallidum operon encoding a putative ABC transport system, an iron-activated repressor protein homolog, and a glycolytic pathway enzyme homolog. Gene. 1997;197:47–64. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe A M, Lambert P A, Smith A W. Cloning of an Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis antigen: homology with adhesins from some oral streptococci. Infect Immun. 1995;63:703–706. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.703-706.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller J N, Whang S J, Fazzan F P. Studies on immunity in experimental syphilis. II. Treponema pallidum immobilization (TPI) antibody and the immune response. Br J Vener Dis. 1963;39:199–203. doi: 10.1136/sti.39.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norris S J The Treponema pallidum Polypeptide Research Group. Polypeptides of Treponema pallidum: progress toward understanding their structural, functional, and immunologic roles. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:750–779. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.750-779.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radolf J D, Chamberlain N R, Clausell A, Norgard M V. Identification and localization of integral membrane proteins of virulent Treponema pallidum by phase partitioning with the nonionic detergent Triton X-114. Infect Immun. 1988;56:490–498. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.490-498.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radolf J D, Norgard M V, Shulz W W. Outer membrane ultrastructure explains the limited antigenicity of virulent Treponema pallidum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2051–2055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Von Heijne G. A new method for identifying secretory signal sequences and for predicting the site of cleavage between a signal sequence and the mature exported protein is described. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker E M, Zampighi G A, Blanco D R, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Demonstration of rare protein in the outer membrane of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum by freeze-fracture analysis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5005–5011. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5005-5011.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wessel D, Flugge U I. A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal Biochem. 1984;138:141–143. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitelegge, J. P., and K. F. Faull. Unpublished data.

- 23.Whitelegge J P, Gundersen C, Faull K F. Electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry of intact intrinsic membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1423–1430. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]