Abstract

Aims

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) are two growing epidemics that frequently co-exist. We aimed to gain insights into the underlying pathophysiological pathways in HF patients with AF by comparing circulating biomarkers using pathway overrepresentation analyses.

Methods and results

From a panel of 92 biomarkers from different pathophysiological domains available in 1620 patients with HF, we first tested which biomarkers were dysregulated in patients with HF and AF (n = 648) compared with patients in sinus rhythm (n = 972). Secondly, pathway overrepresentation analyses were performed to identify biological pathways linked to higher plasma concentrations of biomarkers in patients who had HF and AF. Findings were validated in an independent HF cohort (n = 1219, 38% with AF). Patient with AF and HF were older, less often women, and less often had a history of coronary artery disease compared with those in sinus rhythm. In the index cohort, 24 biomarkers were up-regulated in patients with AF and HF. In the validation cohort, eight biomarkers were up-regulated, which all overlapped with the 24 biomarkers found in the index cohort. The strongest up-regulated biomarkers in patients with AF were spondin-1 (fold change 1.18, P = 1.33 × 10−12), insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 (fold change 1.32, P = 1.08 × 10−8), and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7 (fold change 1.33, P = 1.35 × 10−18). Pathway overrepresentation analyses revealed that the presence of AF was associated with activation amyloid-beta metabolic processes, amyloid-beta formation, and amyloid precursor protein catabolic processes with a remarkable consistency observed in the validation cohort.

Conclusion

In two independent cohorts of patients with HF, the presence of AF was associated with activation of three pathways related to amyloid-beta. These hypothesis-generating results warrant confirmation in future studies.

Keywords: Heart failure, Atrial fibrillation, Pathway analysis, Amyloid-beta

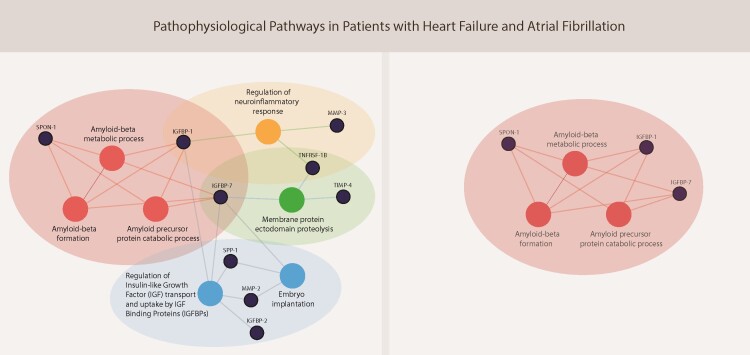

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Common disease-promoting signalling pathways in heart failure and atrial fibrillation: putative underlying mechanisms and potential therapeutic consequences’, by Joshua A. Keefe et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvac107.

1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in heart failure (HF) with a prevalence between 20% and 60% depending on the type and severity of HF.1–3 Both AF and HF are strongly associated with ageing, share many other clinical risk factors such as obesity and hypertension, and can trigger each other.2,3 Distinct differences are observed when comparing patients with HF with and without AF. We recently showed that patients with AF and HF are older, less often have an ischaemic aetiology of HF, and have a distinct biomarker profile when compared with HF patients in sinus rhythm.4,5 Moreover, patients with AF and HF have a poorer quality of life and worse outcomes when compared with those without AF.4,6 Pooled individual-patient data revealed that in contrast to the beneficial effects observed in patients with HF with a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) in sinus rhythm, β-blockers did not improve clinical outcomes in patients with AF and HFrEF.7 The potential lack of β-blocker efficacy suggests differences in pathophysiology between HF patients with and without AF, but the exact mechanisms remain poorly understood and understudied.7

Unravelling the underlying pathophysiology of AF in HF is important since this population might respond to different therapies than HF patients without AF.8,9 Underlying pathophysiological mechanisms can be studied by performing pathway overrepresentation analyses, a method that can identify associated pathways based on circulating biomarker profiles in specific subgroups.10,11 Therefore, we compared patients who had HF with and without AF, studied their biomarker profiles and associated pathophysiological pathways, which might help discover new treatment targets for patients with HF and AF.

2. Methods

2.1 Patient population

We performed a post hoc study of patients enrolled in A Systems Biology Study to Tailored Treatment in Chronic Heart Failure (BIOSTAT-CHF), of which the design and primary results have been published previously.12,13 In brief, BIOSTAT-CHF was a prospective, observational, multinational, European HF study, in which a total of 2516 patients were included. Patients were eligible with either a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40% or plasma concentrations of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) >2000 ng/L. Another 1738 patients with HF were included in an independent cohort from six centres in Scotland, which we have used as our validation cohort. Patients were enrolled into the validation cohort when they were diagnosed with HF and had a previous documented admission with HF requiring diuretic treatment.12 This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, and medical ethics committees of participating centres approved the study. All patients provided written informed consent.

2.2 Definitions

Patients were classified as AF when they met the following criteria: (i) a documented history of AF and (ii) AF registered on the standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) at baseline of the study. Patients were classified as having sinus rhythm when they met the following criteria: (i) no documented history of AF and (ii) sinus rhythm on the baseline ECG. Patients with a pacemaker rhythm (n = 320) or unknown rhythm (n = 58) were excluded from our analyses. Patients with prior episodes of AF but who were in sinus rhythm at baseline (n = 197) and those without a history of AF but with AF on the baseline ECG (n = 82) were excluded from our analyses, since these patients could interfere with the contrast in underlying pathophysiological pathways between the AF and sinus rhythm groups under study. We did include these patients in a previous biomarker study on AF in BIOSTAT-CHF, but since subsequent analyses revealed that many biomarkers tend to fluctuate with paroxysmal episodes of AF, we chose to include HF patients with ‘permanent’ AF when compared with those who never had any previously documented episode of AF in the current analyses.4,5 A flow chart of the selected patients is displayed in Supplementary material online, Figure S1.

2.3 Biomarkers

The Olink Cardiovascular III panel includes 92 biomarkers from different pathophysiological domains. The Proseek Multiplex 96 × 96 kit of Olink Bioscience (Uppsala, Sweden) analysis service was used, which measured the 92 biomarkers in 1 µl plasma samples. The reagents are based on the Proximity Extension Assay technology, which binds 92 oligonucleotide-labelled antibody probe pairs to the target biomarker.14 For further quantification, real-time PCR was performed. Olink wizard and GenEx software were used for further data analysis. Proseek® data are presented as arbitrary units on a log2 scale (Supplementary material online, Tables S1 and S2). Complete biomarker data were available in 87% of the patients under study.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Normally distributed continuous variables were displayed as mean ± standard deviation, non-normally distributed variables as median with the first and third quartile (Q1–3). Categorical variables were presented as numbers with percentages. Group comparisons were tested using Student’s t-tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, or χ2 tests where appropriate. Differences in expression of the 92 biomarkers between patients with AF vs. sinus rhythm were tested using Linear Models for Microarray data analysis (Limma) software (version 3.34.9), using a log2 fold change cut-off of 0.2, and a false discovery rate <0.05 according to the Benjamini–Hochberg method. The biomarkers that were up-regulated in patients with AF compared to those in sinus rhythm were further studied by using pathway overrepresentation analysis. Pathway overrepresentation analysis was performed with knowledge from established pathways in publicly available databases: Gene Ontology, Reactome, and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) using Cytoscape (version 3.7.1) and plugin ClueGO (version 2.5.4).10,15,16 Multivariable logistic regression was performed to study the association between the biomarkers within pathways and AF status, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), heart rate, a history of coronary artery disease, and renal disease. Since we were interested in underlying pathophysiological differences between patients with HF with a reduced/mid-range/preserved ejection fraction HFrEF/HFmrEF/HFpEF, we performed the same analyses in these subgroups. Unfortunately, these subgroups were too small to gain results with pathway overrepresentation analyses. This was still the case when we analysed only two groups: LVEF <45% vs. LVEF ≥45%. We therefore tested for interactions to determine whether the association of biomarkers and AF status was present in patients with HFrEF/HFmrEF/HFpEF by adding the interaction term to the logistic regression model and also tested for an interaction with LVEF on a continuous scale. A separate network analysis focusing on pathophysiological differences between patients with HFpEF and HFrEF has been published previously.11 A P-value smaller than 0.1 was considered statistically significant for testing interactions. All other tests were performed two-sided, and a P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using R, A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 3.5.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1 Index cohort

3.1.1 Clinical characteristics

Of 1620 patients with HF enrolled, 648 (40%) had AF and 972 (60%) were in sinus rhythm. Patients with AF were older, less often women, had a higher BMI and a higher heart rate (Table 1). Fewer patients with AF had a history of coronary artery disease, but more often a history of renal disease when compared with those in sinus rhythm. Patients with AF had larger left atrial diameters, and greater interventricular and posterior wall thickness on echocardiography.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the index cohort

| Atrial fibrillation, n = 648 (40%) | Sinus rhythm, n = 972 (60%) | P-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | |||

| Age (years) | 72 ± 10 | 65 ± 13 | <0.001 |

| Women (%) | 164 (25) | 298 (31) | 0.02 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28 ± 6 | 27 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| NYHA class I/II/III/IV (%) | 9/50/37/4 | 12/53/32/4 | 0.07 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 125 ± 21 | 126 ± 23 | 0.43 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76 ± 13 | 75 ± 14 | 0.23 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 91 ± 24 | 80 ± 18 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | <0.001 | ||

| Never | 270 (42) | 322 (33) | |

| Past | 318 (49) | 450 (46) | |

| Current | 58 (9) | 200 (21) | |

| History of (%) | |||

| Coronary artery diseasea | 244 (38) | 448 (46) | 0.001 |

| Valvular surgery | 71 (11) | 31 (3) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 72 (11) | 71 (7) | 0.011 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 69 (11) | 88 (9) | 0.33 |

| Hypertension | 419 (65) | 597 (61) | 0.20 |

| Diabetes | 210 (32) | 308 (32) | 0.80 |

| COPD | 116 (18) | 140 (14) | 0.07 |

| Renal disease | 213 (33) | 213 (22) | <0.001 |

| Physical examination (%) | |||

| Rales | 356 (56) | 486 (52) | 0.10 |

| Oedema | 393 (70) | 399 (50) | <0.001 |

| Hepatomegaly | 113 (18) | 106 (11) | <0.001 |

| KCCQ—Quality of Life | |||

| Functional status score | 43 (25–64) | 54 (34–75) | <0.001 |

| Clinical summary score | 41 (24–61) | 50 (32–71) | <0.001 |

| Overall score | 41 (26–61) | 51 (34–70) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | 3430 (1872–6387) | 2293 (925–5347) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 13.3 (11.9–14.6) | 13.4 (12.1–16.6) | 0.28 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 104 (88–131) | 97 (80–121) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiographic data | |||

| LVEF, % | 33 ± 12 | 29 ± 10 | <0.001 |

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 50 ± 8 | 46 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Interventricular wall thickness, mm | 11 ± 2 | 10 ± 2 | <0.001 |

| Posterior wall thickness, mm | 11 ± 2 | 10 ± 2 | <0.001 |

| Medication at baseline (%) | |||

| ACEi or ARB | 440 (68) | 726 (75) | 0.003 |

| β-blocker | 523 (81) | 810 (83) | 0.20 |

| MRA | 318 (49) | 516 (53) | 0.13 |

| Diuretics | 648 (100) | 971 (100) | 1.00 |

| Amiodarone | 81 (13) | 110 (11) | 0.52 |

| Digoxin | 246 (38) | 60 (6) | <0.001 |

| Verapamil/diltiazem | 22 (3) | 7 (1) | <0.001 |

| Class 1c antiarrhythmic drugs | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.00 |

| Ivabradine | 0 (0) | 23 (2) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin K antagonist | 461 (71) | 130 (13) | <0.001 |

| Direct oral anticoagulants | 7 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.004 |

P-values for group comparisons were tested using Student’s t-tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, or χ2 tests where appropriate.

ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Coronary artery disease: previous myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and/or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG).

3.1.2 Biomarker concentrations

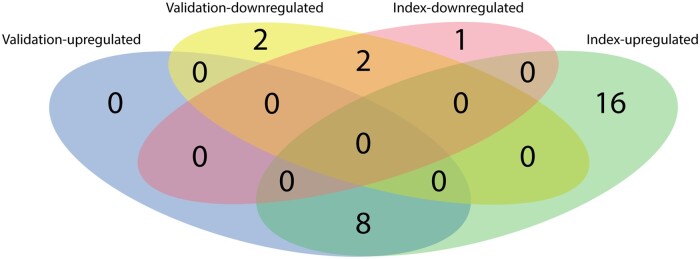

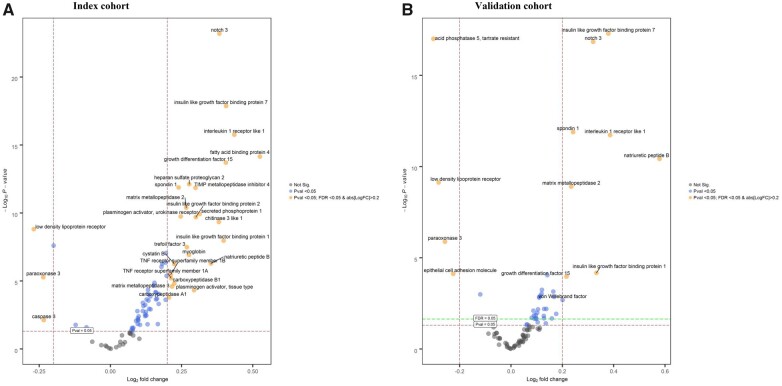

In the index cohort, 24 biomarkers were up-regulated and three biomarkers were down-regulated in patients with AF as compared to those in sinus rhythm (Figure 1). A volcano plot with the up- and down-regulated biomarkers is presented in Figure 2A. The three biomarkers that were most significantly differentially expressed in patients with AF when compared with those in sinus rhythm were neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 3 (NOTCH3, fold change 1.30, P = 6.40 × 10−24), insulin-like growth factor binding protein-7 (IGFBP-7, fold change 1.33, P = 1.35 × 10−18), and interleukin-1 receptor-like 1 (IL1RL1, fold change 1.35, P = 1.75 × 10−16) (Supplementary material online, Table S1).

Figure 1.

Venn diagram displaying the number of significantly up-regulated and down-regulated biomarkers in patients with atrial fibrillation vs. sinus rhythm in the index (n = 1620) and validation cohort (n = 1219) of BIOSTAT-CHF.

Figure 2.

Volcano plots of differential biomarker expression in patients with atrial fibrillation vs. sinus rhythm in the index (A, n = 1620) and validation cohort (B, n = 1219) of BIOSTAT-CHF. y-axis = significance, x-axis = effect size (positive = up-regulated, negative = down-regulated), labelled biomarkers are significantly differentially expressed proteins.

3.1.3 Pathway overrepresentation analyses of up-regulated biomarkers

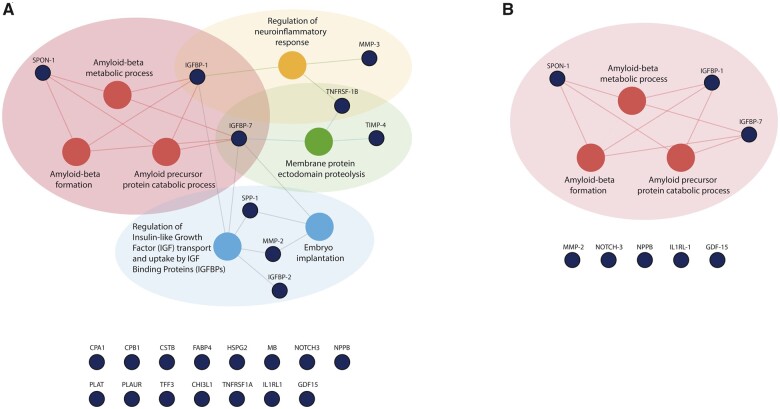

Pathway overrepresentation analyses of the 24 up-regulated biomarkers in the index cohort revealed seven pathways that were dysregulated specifically in patients with AF: (i) amyloid-beta metabolic process, (ii) amyloid-beta formation, (iii) amyloid precursor protein catabolic process, (iv) regulation of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) transport and uptake by IGF binding proteins, (v) embryo implantation, (vi) membrane protein ectodomain proteolysis, and (vii) regulation of neuroinflammatory response (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Results of pathway overrepresentation analyses of patients with atrial fibrillation vs. sinus rhythm in the index cohort (A, n = 1620) and the validation cohort (B, n = 1219) of BIOSTAT-CHF. The nodes in blue represent the 24 biomarkers that were significantly up-regulated in patients with atrial fibrillation when compared with those in sinus rhythm in the index cohort (A), and eight biomarkers that were significantly up-regulated in these patients in the validation cohort (B). The nodes in red reveal the overrepresented pathways of these biomarkers. Based on current knowledge, the blue nodes below the figures are biomarkers that were not found to be overrepresented in a specific biological pathway. CHI3L1, chitinase 3 like 1; CPA1, carboxypeptidase A1; CPB1, carboxypeptidase B1; CSTB, cystatin B; FABP4, fatty acid-binding protein 4, adipocyte; GDF-15, growth differentiation factor 15; HSPG2, heparan sulphate proteoglycan 2; IGFBP-1, insulin like growth factor binding protein 1; IGFBP-2, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2; IGFBP-7, insulin like growth factor binding protein 7; IL1RL-1, interleukin 1 receptor like 1; MB, myoglobin; MMP-2, matrix metallopeptidase 2; MMP-3, matrix metallopeptidase 3; NOTCH3, neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 3; NPPB, natriuretic peptide B; PLAT, plasminogen activator, tissue type; PLAUR, plasminogen activator, urokinase receptor; SPON-1, spondin-1; SPP-1, secreted phosphoprotein 1; TFF3, trefoil factor 3; TIMP-4, metalloproteinase inhibitor 4; TNFRSF1A, TNF receptor superfamily member 1A; TNFRSF1B, TNF receptor superfamily member 1B.

3.2 Validation cohort

3.2.1 Clinical characteristics

The baseline characteristics of patients included in the smaller validation cohort are presented in Table 2. In general, patients enrolled in the validation cohort were older, had a higher LVEF, and lower plasma concentrations of NT-proBNP when compared with patients included in the index cohort. However, similar trends were observed in patients with AF compared to those in sinus rhythm, in which patients with AF were older, less often women, had higher heart rates, and less often a history of coronary artery disease.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the validation cohort

| Atrial fibrillation, n = 468 (38%) | Sinus rhythm, n = 751 (62%) | P-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | |||

| Age (years) | 75 ± 10 | 72 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| Women (%) | 148 (32) | 291 (39) | 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 ± 6 | 29 ± 6 | 0.13 |

| NYHA class I/II/III/IV (%) | 0/39/46/14 | 2/42/44/13 | 0.22 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126 ± 21 | 127 ± 23 | 0.38 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 72 ± 15 | 68 ± 12 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 87 ± 27 | 72 ± 18 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | <0.001 | ||

| Never | 275 (59) | 358 (48) | |

| Past | 148 (32) | 279 (37) | |

| Current | 43 (9) | 110 (15) | |

| History of (%) | |||

| Coronary artery diseasea | 194 (42) | 462 (62) | <0.001 |

| Valvular surgery | 39 (8) | 39 (5) | 0.04 |

| Stroke | 105 (23) | 105 (14) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 96 (21) | 160 (22) | 0.79 |

| Hypertension | 274 (59) | 434 (58) | 0.80 |

| Diabetes | 149 (32) | 225 (30) | 0.53 |

| COPD | 83 (18) | 135 (18) | 0.99 |

| Renal disease | 220 (47) | 312 (42) | 0.11 |

| Physical examination (%) | |||

| Rales | 219 (49) | 301 (42) | 0.02 |

| Oedema | 290 (68) | 385 (57) | 0.001 |

| Hepatomegaly | 20 (5) | 23 (3) | 0.36 |

| KCCQ—Quality of Life | |||

| Functional status score | 45 (25–65) | 46 (27–71) | 0.05 |

| Clinical summary score | 41 (25–65) | 45 (26–70) | 0.07 |

| Overall score | 42 (30–60) | 45 (30–68) | 0.03 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | 2105 (1045–4204) | 872 (311–2807) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 13.5 (12.1–14.7) | 13.1 (11.7–14.3) | 0.004 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 98 (82–123) | 95 (77–121) | 0.04 |

| Echocardiographic data | |||

| LVEF, % | 43 ± 13 | 41 ± 13 | 0.03 |

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 48 ± 7 | 43 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| Interventricular wall thickness, mm | 13 ± 3 | 12 ± 4 | 0.29 |

| Posterior wall thickness, mm | 12 ± 4 | 11 ± 5 | 0.54 |

| Medication at baseline (%) | |||

| ACEi or ARB | 322 (69) | 540 (72) | 0.28 |

| β-blocker | 339 (72) | 540 (72) | 0.89 |

| MRA | 144 (31) | 229 (31) | 0.97 |

| Diuretics | 457 (98) | 746 (99) | 0.02 |

| Amiodarone | 12 (3) | 27 (4) | 0.41 |

| Digoxin | 193 (41) | 12 (2) | <0.001 |

| Verapamil/diltiazem | 18 (4) | 13 (2) | 0.036 |

| Class 1c antiarrhythmic drugs | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Ivabradine | 1 (1) | 33 (4) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin K antagonist | 327 (70) | 87 (12) | <0.001 |

| Direct oral anticoagulants | 22 (5) | 6 (1) | <0.001 |

P-values for group comparisons were tested using Student’s t-tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, or χ2 tests where appropriate.

ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Coronary artery disease: previous myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and/or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG).

3.2.2 Biomarker concentrations

In the validation cohort, eight biomarkers were significantly up-regulated in patients with AF, all of which overlapped with the 24 biomarkers that were found to be significantly up-regulated in the index cohort (Figure 1). The eight biomarkers that were up-regulated in AF patients in both HF cohorts included IGFBP-7 (fold change 1.30, P = 5.13 × 10−18), NOTCH3 (fold change 1.25, P = 1.44 × 10−17), spondin-1 (SPON1, fold change 1.18, P = 1.29 × 10−12), IL1RL1 (fold change 1.31, P = 3.44 × 10−11), natriuretic peptide B (fold change 1.49, P = 3.78 × 10−11), matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP-2, fold change 1.18, P = 1.25 × 10−9), IGFBP-1 (fold change 1.26, P = 6.68 × 10−5), and growth differentiation factor 15 (fold change 1.16, P = 1.07 × 10−4) (Supplementary material online, Table S2). Low-density lipoprotein receptor and paraoxonase 3 (PON3) were significantly down-regulated in patients with AF in both the index and the validation cohort.

3.2.3 Pathway overrepresentation analyses of up-regulated biomarkers

Pathway overrepresentation analysis of the eight up-regulated biomarkers in patients with AF in the validation cohort revealed three activated pathways: (i) amyloid-beta metabolic process, (ii) amyloid-beta formation, and (iii) amyloid precursor protein catabolic process (Figure 3).

3.2.4 Overlap index and validation cohort

The three amyloid-beta-related pathways were found in both the index and validation cohort, and were related to three up-regulated biomarkers in patients with AF: SPON1 (fold change 1.18, P = 1.33 × 10−12), IGFBP-1 (fold change 1.32, P = 1.08 × 10−8), and IGFBP-7 (fold change 1.33, P = 1.35 × 10−18). After adjusting for the clinical covariates: age, sex, BMI, heart rate, a history of coronary artery disease, and renal disease, the concentrations of SPON-1, IGFBP-1, and IGFBP-7 remained associated with the presence of AF (all P < 0.001), in both the index and the validation cohort. These associations were similar among HF phenotypes (HFrEF/HFmrEF/HFpEF; P for interaction = 0.42) and across LVEF as a continuous variable (P for interaction = 0.96).

4. Discussion

We sought to identify pathophysiological pathways in HF patients with AF using pathway overrepresentation analyses. In two independent HF cohorts, we found that the presence of AF was associated with amyloid-beta metabolic processes, amyloid-beta formation, and amyloid precursor protein catabolic processes. These three pathophysiological pathways were found based on higher levels of SPON1, IGFBP-1, and IGFBP-7 in those with AF. In the larger index cohort, four more pathophysiological pathways were found, which were not observed in the independent validation cohort. Previous studies investigating specific phenotypes or subgroups in HF (e.g. diabetes, ischaemic HF, old vs. young, and HFpEF vs. HFrEF) have not revealed any amyloid-beta-related pathways despite using the same methodology, which supports that the current findings might be specific to the presence of AF in patients with HF.10,11,17

4.1 Individual biomarkers

In the present study, the concentrations of SPON-1, IGFBP-1, and IGFBP-7 were closely linked to the three amyloid-beta-related pathways. Although IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-7 are linked to a wide range of biological processes associated with inhibition and stimulation of cell growth, the current knowledge indicates a more specific role for SPON-1.18 SPON-1 is an extracellular matrix cell adhesion glycoprotein that is expressed in multiple organs including the heart and brain.18 The SPON-1 protein binds to the extracellular domain of amyloid precursor protein and inhibits beta-secretase cleavage of this amyloid precursor protein, a process that is strongly related to the formation of amyloid-beta depositions.19 In a large genome-wide association study investigating the rate of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, the most interesting candidate gene identified was SPON-1, since it was strongly associated with the rate of cognitive decline in two independent cohorts.20 Recent studies showed that increased levels of IGFBP-7, a marker of ageing and cellular senescence, were strongly associated with increased left atrial size, and the presence of AF in patients with HF.21–23 In Framingham Heart Study participants without HF, increased levels of IGFBP-1 were strongly associated with incident AF.24 In the present study, NOTCH3 was strongly up-regulated in patients with AF in both cohorts. The NOTCH system communicates in multiple tissues and systems, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.25 In the heart specifically, NOTCH signalling has been suggested to be associated with repair of infarcted and overloaded myocardium, but this has only been investigated in a pre-clinical setting.25 The role of the NOTCH system in patients with AF and HF is yet to be elucidated.

4.2 Amyloid-beta in HF and AF

Cardiac amyloidosis has been reported to be associated with a high prevalence of AF in several previous studies26–31; however, prior work focused on isolated atrial amyloidosis (IAA) and transthyretin-derived amyloidosis (ATTR)—the most commonly described forms of cardiac amyloidosis in elderly patients. Our results concerned amyloid-beta depositions, which are generally acknowledged as a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, in which abnormal cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein leads to pathological amyloid-beta fragments, protein aggregation, and formation of extracellular plaques that can lead to degradation of neurons.32,33 Even though Alzheimer’s disease has been traditionally considered as a brain-specific disease, recent discoveries suggest that other organs might also be involved in the pathophysiology, suggesting that Alzheimer’s disease might be a focal manifestation of a systemic disorder.32,34 The epidemiological link between AF and Alzheimer’s disease was first described in 1977, followed by studies showing that younger patients with AF had an increased risk of developing all-cause dementia, which could not be explained by the increased incidence of stroke alone.35–37 Since then, contradictory results have been reported, but neuropathological analyses of autopsies did reveal a higher incidence of amyloid-beta plaques and amyloid angiopathy in the brains of patients with permanent AF.38 Suggesting a unifying pathogenesis, Troncone et al.34 performed a cross-sectional study investigating cardiac involvement of patients with a primary diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease as compared to age-matched controls. Indeed, those with Alzheimer’s disease had increased left ventricular septal and inferolateral wall thickness on echocardiography, and expression of amyloid-beta plaques in both the heart and the brain.

4.3 Clinical relevance

Even though the current study revealed pathways related to amyloid-beta specifically, considerable overlap can be observed with more commonly recognized protein-misfolding diseases that are known to affect the heart. As recently reviewed, cardiac involvement has predominantly been reported in IAA, light chain (AL) and ATTR amyloidosis, but may occur in other types of amyloidosis, with cardiac arrhythmias, especially AF, as common presenting clinical features.39 The consistency of cardiac clinical presentations among the various types of amyloidosis, despite differences in involved proteins (e.g. atrial natriuretic peptide [ANP] vs. AL vs. ATTR), suggest common cardiac effects that may also plausibly apply to amyloid-beta deposition.40 Notably, the emergence of promising new treatment options for ATTR amyloidosis has raised awareness of the importance of screening for amyloidosis in patients with suggestive clinical features.41–43 Whether similar mechanistic approaches can be of use in patients with cardiac amyloid-beta depositions warrants further study.

4.4 Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, there have been no previous studies investigating underlying pathophysiological processes using pathway overrepresentation in patients with AF and HF. Therefore, our study adds to the limited understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of AF in patients with HF. The greatest strength of the current study is that we were able to validate our results in an independent HF cohort with clear definitions, and that the pathway overrepresentation analysis was based on a large number of measured plasma biomarkers.

A limitation of this study is that the findings are based on post hoc analyses. Unfortunately, we did not have direct biopsy evidence of cardiac/atrial amyloid-beta involvement, which are pivotal to confirm the cardiac amyloid-beta hypothesis. Future research in cases (patients with AF + HF) and controls (patients in sinus rhythm with and without HF) with markers derived from atrial tissue will provide more direct insights into our hypothesis.44 Another limitation concerns the selected biomarker panel, which did cover many pathophysiological domains but was primarily a cardiovascular disease-related biomarker panel. The number of significantly up-regulated biomarkers was higher in the index cohort than in the validation cohort, which resulted in more associated pathophysiological processes in the index cohort than in the validation cohort. This could be the consequence of the larger number of patients included in the index cohort, the different inclusion criteria of patients that were used for the two independent cohorts, or the different regions of inclusion of the study participants (11 European counties vs. six centres in Scotland). The use of amiodarone was higher in the index cohort compared with the validation cohort. However, despite these differences between the two cohorts, all up-regulated biomarkers and pathways found in the validation cohort overlapped with those found in the index cohort. The HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF subgroups were unfortunately too small to yield results with pathway overrepresentation analyses. There was, however, no interaction between the amyloid-beta-related biomarkers and the HF subgroups, suggesting a pathophysiological role of amyloid-beta in HF patients across the full LVEF spectrum. Not all (combinations of) biomarkers were annotated by the publicly available databases even though these biomarkers were deemed to be significantly up- or down-regulated in our analyses (e.g. NOTCH3 and IL1RL1), since the content of these databases is based on what is currently known about these biomarkers. Therefore, the results of the current pathway overrepresentation analyses might change over time, when the knowledge on the (combination of) biomarkers has increased. The current findings might reflect underlying pathophysiological processes specific to elderly patients with AF and HF, since the mean age of these patients was 72 and 75 years in the two cohorts, respectively. The number of women included in the cohorts was limited [n = 462 (index) and n = 439 (validation), 32%] and mainly comprised postmenopausal women. Even though we have attempted to define the AF and sinus rhythm group mutually exclusive, it is possible that patients with asymptomatic paroxysmal AF were misclassified. Based on the current definition, we may have predominantly included patients with persistent/permanent AF and less patients with paroxysmal AF. Moreover, we do not have data on the duration of AF since no continues rhythm monitoring was incorporated in the study protocol, which might have influenced the biomarker concentrations. Unfortunately, we also do not have information on cognitive function, other neurologic diseases, nor information on systemic or cardiac amyloidosis of patients enrolled in BIOSTAT-CHF, which could have strengthened our hypothesis linking AF–HF to Alzheimer’s disease and/or amyloidosis. As with all cross-sectional studies, we cannot prove causality.

5. Conclusion

In two independent cohorts of patients with HF, the presence of AF was associated with amyloid-beta metabolic processes, amyloid-beta formation, and amyloid precursor protein catabolic processes, based on higher levels of SPON1, IGFBP-1, and IGFBP-7 in those with AF. These hypothesis-generating results warrant confirmation in future studies.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Author’s contributions

A.A.V., N.J.S., L.L.N., C.C.L., P.v.d.M., J.M.T.M., K.D., J.G.C., F.Z., S.D.A., M.M., D.J.v.V., and G.F. conceived and designed the research. B.T.S., V.A.A., and I.E.S. have performed statistical analyses. A.A.V., C.S.P.L., and D.J.v.V. handled funding and supervision. A.A.V., N.J.S., L.L.N., C.C.L., P.v.d.M., J.M.T.M., K.D., J.G.C., F.Z., S.D.A., M.M., G.F., and D.J.v.V. acquired the data. B.T.S drafted the manuscript. V.A.A., I.E.S., M.K., M.P.v.d.B., H.L.A.N., I.C.V.G., P.v.d.M., F.Z., M.M., J.M.T.M., J.G.C., L.L.N., S.D.A., C.C.L., N.J.S., K.D., G.F., D.J.v.V., C.S.P.L., M.R., and A.A.V. have provided critical revisions of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Commission (FP7-242209-BIOSTAT-CHF).

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Bernadet T Santema, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Vicente Artola Arita, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Iziah E Sama, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Mariëlle Kloosterman, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Maarten P van den Berg, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Hans L A Nienhuis, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Isabelle C Van Gelder, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Peter van der Meer, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Faiez Zannad, Department of Cardiology, INSERM, Centre d’Investigations Cliniques Plurithé matique 1433, INSERM U1116, Université de Lorraine, CHRU de Nancy, F-CRIN INI-CRCT, Nancy, France.

Marco Metra, Department of Medical and Surgical Specialties, Institute of Cardiology, Radiological Sciences and Public Health, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy.

Jozine M Ter Maaten, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

John G Cleland, Department of Cardiology, National Heart & Lung Institute, Royal Brompton & Harefield Hospitals, Imperial College, London, UK; Department of Cardiology, Robertson Institute of Biostatistics and Clinical Trials Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK.

Leong L Ng, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK; Department of Cardiology, NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, UK.

Stefan D Anker, Department of Cardiology (CVK) and Berlin Institute of Health Center for Regenerative Therapies (BCRT), German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) Partner Site Berlin, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

Chim C Lang, Division of Molecular and Clinical Medicine, School of Medicine Centre for Cardiovascular and Lung Biology, Ninewells Hospital & Medical School, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK.

Nilesh J Samani, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK; Department of Cardiology, NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, UK.

Kenneth Dickstein, Department of Cardiology, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; Department of Cardiology, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway.

Gerasimos Filippatos, Department of Cardiology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Attikon University Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Dirk J van Veldhuisen, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Carolyn S P Lam, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands; Department of Cardiology, National Heart Centre Singapore and Duke-National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore.

Michiel Rienstra, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Adriaan A Voors, Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Translational perspective

Using an unbiased approach, we identified and validated dysregulation of three amyloid-beta-related pathways in patients who had heart failure (HF) with concomitant atrial fibrillation (AF). Amyloid-beta depositions are a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, but might also play a role in pathophysiological processes outside the central nervous system. Biopsy studies are needed to confirm the pathophysiological role of amyloid-beta in patients with AF and HF. Diagnostic and therapeutic implications should be investigated in the light of potential pathophysiological overlap between the three aging-related epidemics: Alzheimer’s disease, AF, and HF.

References

- 1. Maisel WH, Stevenson LW.. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and rationale for therapy. Am J Cardiol 2003;91:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kotecha D, Lam CS, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van Gelder IC, Voors AA, Rienstra M.. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation: vicious twins. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:2217–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kloosterman M, Santema BT, Roselli C, Nelson CP, Koekemoer A, Romaine SPR, Van Gelder IC, Lam CSP, Artola VA, Lang CC, Ng LL, Metra M, Anker S, Filippatos G, Dickstein K, Ponikowski P, van der Harst P, van der Meer P, van Veldhuisen DJ, Benjamin EJ, Voors AA, Samani NJ, Rienstra M.. Genetic risk and atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Santema BT, Kloosterman M, Van Gelder IC, Mordi I, Lang CC, Lam CSP, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Van der Harst P, Hillege HL, Ter Maaten JM, Metra M, Ng LL, Ponikowski P, Samani NJ, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Zwinderman AH, Zannad F, Damman K, Van der Meer P, Rienstra M, Voors AA.. Comparing biomarker profiles of patients with heart failure: atrial fibrillation vs. sinus rhythm and reduced vs. preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3867–3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Santema BT, Chan MMY, Tromp J, Dokter M, van der Wal HH, Emmens JE, Takens J, Samani NJ, Ng LL, Lang CC, van der Meer P, Ter Maaten JM, Damman K, Dickstein K, Cleland JG, Zannad F, Anker SD, Metra M, van der Harst P, de Boer RA, van Veldhuisen DJ, Rienstra M, Lam CSP, Voors AA.. The influence of atrial fibrillation on the levels of NT-proBNP versus GDF-15 in patients with heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol 2020;109:331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lam CS, Rienstra M, Tay WT, Liu LC, Hummel YM, van der Meer P, de Boer RA, Van Gelder IC, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA, Hoendermis ES.. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: association with exercise capacity, left ventricular filling pressures, natriuretic peptides, and left atrial volume. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kotecha D, Holmes J, Krum H, Altman DG, Manzano L, Cleland JG, Lip GY, Coats AJ, Andersson B, Kirchhof P, von Lueder TG, Wedel H, Rosano G, Shibata MC, Rigby A, Flather MD;Beta-Blockers in Heart Failure Collaborative Group . Efficacy of beta blockers in patients with heart failure plus atrial fibrillation: an individual-patient data meta-analysis. Lancet 2014;384:2235–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Verma A, Kalman JM, Callans DJ.. Treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Circulation 2017;135:1547–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rienstra M, Hobbelt AH, Alings M, Tijssen JGP, Smit MD, Brugemann J, Geelhoed B, Tieleman RG, Hillege HL, Tukkie R, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Crijns HJGM, Van Gelder IC; RACE 3 Investigators . Targeted therapy of underlying conditions improves sinus rhythm maintenance in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: results of the RACE 3 trial. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2987–2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tromp J, Voors AA, Sharma A, Ferreira JP, Ouwerkerk W, Hillege HL, Arevelo Gomez K, Lang CC, Ng LL, van der Harst P, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P, Lam CSP, Zannad F, Sama IE.. Distinct pathological pathways in heart failure patients with diabetes. JACC Heart Fail 2020;8:234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tromp J, Westenbrink BD, Ouwerkerk W, van Veldhuisen DJ, Samani NJ, Ponikowski P, Metra M, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, van der Harst P, Lang CC, Ng LL, Zannad F, Zwinderman AH, Hillege HL, van der Meer P, Voors AA.. Identifying pathophysiological mechanisms in heart failure with reduced versus preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Voors AA, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, van der Harst P, Hillege HL, Lang CC, Ter Maaten JM, Ng L, Ponikowski P, Samani NJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, Zannad F, Zwinderman AH, Metra M.. A systems BIOlogy Study to TAilored Treatment in Chronic Heart Failure: rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of BIOSTAT-CHF. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:716–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ouwerkerk W, Voors AA, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, van der Harst P, Hillege HL, Lang CC, Ter Maaten JM, Ng LL, Ponikowski P, Samani NJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, Zannad F, Metra M, Zwinderman AH.. Determinants and clinical outcome of uptitration of ACE-inhibitors and beta-blockers in patients with heart failure: a prospective European study. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1883–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Assarsson E, Lundberg M, Holmquist G, Björkesten J, Thorsen SB, Ekman D, Eriksson A, Rennel Dickens E, Ohlsson S, Edfeldt G, Andersson A, Lindstedt P, Stenvang J, Gullberg M, Fredriksson S.. Homogenous 96-plex PEA immunoassay exhibiting high sensitivity, specificity, and excellent scalability. PLoS One 2014;9:e95192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T.. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 2003;13:2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, Charoentong P, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Fridman WH, Pages F, Trajanoski Z, Galon J.. ClueGO: a cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics 2009;25:1091–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sama IE, Woolley RJ, Nauta JF, Romaine SPR, Tromp J, Maaten JM, Meer P, Lam CSP, Samani NJ, Ng LL, Metra M, Dickstein K, Anker SD, Zannad F, Lang CC, Cleland JGF, Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL, Voors AA.. A network analysis to identify pathophysiological pathways distinguishing ischaemic from non-ischaemic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:821–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. UniProt Consortium . UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:D506–D515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ho A, Sudhof TC.. Binding of F-spondin to amyloid-beta precursor protein: a candidate amyloid-beta precursor protein ligand that modulates amyloid-beta precursor protein cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:2548–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sherva R, Tripodis Y, Bennett DA, Chibnik LB, Crane PK, de Jager PL, Farrer LA, Saykin AJ, Shulman JM, Naj A, Green RC; GENAROAD Consortium; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium . Genome-wide association study of the rate of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2014;10:45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Januzzi JL, Packer M, Claggett B, Liu J, Shah AM, Zile MR, Pieske B, Voors A, Gandhi PU, Prescott MF, Shi V, Lefkowitz MP, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD.. IGFBP7 (insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7) and neprilysin inhibition in patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2018;11:e005133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gandhi PU, Gaggin HK, Redfield MM, Chen HH, Stevens SR, Anstrom KJ, Semigran MJ, Liu P, Januzzi JL.. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7 as a biomarker of diastolic dysfunction and functional capacity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: results from the RELAX trial. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:860–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gandhi PU, Chow SL, Rector TS, Krum H, Gaggin HK, McMurray JJ, Zile MR, Komajda M, McKelvie RS, Carson PE, Januzzi JL, Anand IS.. Prognostic value of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Card Fail 2017;23:20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Staerk L, Preis SR, Lin H, Lubitz SA, Ellinor PT, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Trinquart L.. Protein biomarkers and risk of atrial fibrillation: the FHS. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2020;13:e007607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferrari R, Rizzo P.. The Notch pathway: a novel target for myocardial remodelling therapy? Eur Heart J 2014;35:2140–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van den Berg MP, Mulder BA, Klaassen SHC, Maass AH, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P, Nienhuis HLA, Hazenberg BPC, Rienstra M.. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, atrial fibrillation, and the role of senile amyloidosis. Eur Heart J 2019;40:1287–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rapezzi C, Merlini G, Quarta CC, Riva L, Longhi S, Leone O, Salvi F, Ciliberti P, Pastorelli F, Biagini E, Coccolo F, Cooke RM, Bacchi-Reggiani L, Sangiorgi D, Ferlini A, Cavo M, Zamagni E, Fonte ML, Palladini G, Salinaro F, Musca F, Obici L, Branzi A, Perlini S.. Systemic cardiac amyloidoses: disease profiles and clinical courses of the 3 main types. Circulation 2009;120:1203–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Longhi S, Quarta CC, Milandri A, Lorenzini M, Gagliardi C, Manuzzi L, Bacchi-Reggiani ML, Leone O, Ferlini A, Russo A, Gallelli I, Rapezzi C.. Atrial fibrillation in amyloidotic cardiomyopathy: prevalence, incidence, risk factors and prognostic role. Amyloid 2015;22:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pinney JH, Whelan CJ, Petrie A, Dungu J, Banypersad SM, Sattianayagam P, Wechalekar A, Gibbs SD, Venner CP, Wassef N, McCarthy CA, Gilbertson JA, Rowczenio D, Hawkins PN, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ.. Senile systemic amyloidosis: clinical features at presentation and outcome. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grogan M, Scott CG, Kyle RA, Zeldenrust SR, Gertz MA, Lin G, Klarich KW, Miller WL, Maleszewski JJ, Dispenzieri A.. Natural history of wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and risk stratification using a novel staging system. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1014–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Röcken C, Peters B, Juenemann G, Saeger W, Klein HU, Huth C, Roessner A, Goette A.. Atrial amyloidosis: an arrhythmogenic substrate for persistent atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2002;106:2091–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang J, Gu BJ, Masters CL, Wang YJ.. A systemic view of Alzheimer disease—insights from amyloid-beta metabolism beyond the brain. Nat Rev Neurol 2017;13:612–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murphy MP, LeVine H.. Alzheimer’s disease and the amyloid-beta peptide. J Alzheimers Dis 2010;19:311–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Troncone L, Luciani M, Coggins M, Wilker EH, Ho CY, Codispoti KE, Frosch MP, Kayed R, Del Monte F.. Abeta amyloid pathology affects the hearts of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: mind the heart. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:2395–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cardiogenic dementia. Lancet 1977;1:27–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ott A, Breteler MM, de Bruyne MC, van Harskamp F, Grobbee DE, Hofman A.. Atrial fibrillation and dementia in a population-based study. The Rotterdam Study. Stroke 1997;28:316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ihara M, Washida K.. Linking atrial fibrillation with Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiological, pathological, and mechanistic evidence. J Alzheimers Dis 2018;62:61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dublin S, Anderson ML, Heckbert SR, Hubbard RA, Sonnen JA, Crane PK, Montine TJ, Larson EB.. Neuropathologic changes associated with atrial fibrillation in a population-based autopsy cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69:609–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ihne S, Morbach C, Obici L, Palladini G, Stork S.. Amyloidosis in heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2019;16:285–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goette A, Kalman JM, Aguinaga L, Akar J, Cabrera JA, Chen SA, Chugh SS, Corradi D, D'Avila A, Dobrev D, Fenelon G, Gonzalez M, Hatem SN, Helm R, Hindricks G, Ho SY, Hoit B, Jalife J, Kim YH, Lip GY, Ma CS, Marcus GM, Murray K, Nogami A, Sanders P, Uribe W, Van Wagoner DR, Nattel S; Document Reviewers. EHRA/HRS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus on atrial cardiomyopathies: definition, characterization, and clinical implication. Europace 2016;18:1455–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Solomon SD, Adams D, Kristen A, Grogan M, Gonzalez-Duarte A, Maurer MS, Merlini G, Damy T, Slama MS, Brannagan TH, Dispenzieri A, Berk JL, Shah AM, Garg P, Vaishnaw A, Karsten V, Chen J, Gollob J, Vest J, Suhr O.. Effects of Patisiran, an RNA interference therapeutic, on cardiac parameters in patients with hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. Circulation 2019;139:431–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Minamisawa M, Claggett B, Adams D, Kristen AV, Merlini G, Slama MS, Dispenzieri A, Shah AM, Falk RH, Karsten V, Sweetser MT, Chen J, Riese R, Vest J, Solomon SD.. Association of Patisiran, an RNA interference therapeutic, with regional left ventricular myocardial strain in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis: the APOLLO study. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:466–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B, Elliott PM, Merlini G, Waddington-Cruz M, Kristen AV, Grogan M, Witteles R, Damy T, Drachman BM, Shah SJ, Hanna M, Judge DP, Barsdorf AI, Huber P, Patterson TA, Riley S, Schumacher J, Stewart M, Sultan MB, Rapezzi C; ATTR-ACT Study Investigators . Tafamidis treatment for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1007–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Molina CE, Abu-Taha IH, Wang Q, Rosello-Diez E, Kamler M, Nattel S, Ravens U, Wehrens XHT, Hove-Madsen L, Heijman J, Dobrev D.. Profibrotic, electrical, and calcium-handling remodeling of the atria in heart failure patients with and without atrial fibrillation. Front Physiol 2018;9:1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Translational perspective

Using an unbiased approach, we identified and validated dysregulation of three amyloid-beta-related pathways in patients who had heart failure (HF) with concomitant atrial fibrillation (AF). Amyloid-beta depositions are a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, but might also play a role in pathophysiological processes outside the central nervous system. Biopsy studies are needed to confirm the pathophysiological role of amyloid-beta in patients with AF and HF. Diagnostic and therapeutic implications should be investigated in the light of potential pathophysiological overlap between the three aging-related epidemics: Alzheimer’s disease, AF, and HF.