ABSTRACT

We have established a mouse papillomavirus (MmuPV1) model that induces both cutaneous and mucosal infections and cancers. In the current study, we use this model to test our hypothesis that passive immunization using a single neutralizing monoclonal antibody can protect both cutaneous and mucosal sites at different time points after viral inoculation. We conducted a series of experiments involving the administration of either a neutralizing monoclonal antibody, MPV.A4, or control monoclonal antibodies to both outbred and inbred athymic mice. Three clinically relevant mucosal sites (lower genital tract for females and anus and tongue for both males and females) and two cutaneous sites (muzzle and tail) were tested. At the termination of the experiments, all tested tissues were harvested for virological analyses. Significantly lower levels of viral signals were detected in the MPV.A4-treated female mice up to 6 h post-viral inoculation compared to those in the isotype control. Interestingly, males displayed partial protection when they received MPV.A4 at the time of viral inoculation, even though they were completely protected when receiving MPV.A4 at 24 h before viral inoculation. We detected MPV.A4 in the blood starting at 1 h and up to 8 weeks postadministration in some mice. Parallel to these in vivo studies, we conducted in vitro neutralization using a mouse keratinocyte cell line and observed complete neutralization up to 8 h post-viral inoculation. Thus, passive immunization with a monoclonal neutralizing antibody can protect against papillomavirus infection at both cutaneous and mucosal sites and is time dependent.

IMPORTANCE This is the first study testing a single monoclonal neutralizing antibody (MPV.A4) by passive immunization against papillomavirus infections at both cutaneous and mucosal sites in the same host in the mouse papillomavirus model. We demonstrated that MPV.A4 administered before viral inoculation can protect both male and female athymic mice against MmuPV1 infections at cutaneous and mucosal sites. MPV.A4 also offers partial protection at 6 h post-viral inoculation in female mice. MPV.A4 can be detected in the blood from 1 h to 8 weeks after intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. Interestingly, males were only partially protected when they received MPV.A4 at the time of viral inoculation. The failed protection in males was due to the absence of neutralizing MPV.A4 at the infected sites. Our findings suggest passive immunization with a single monoclonal neutralizing antibody can protect against diverse papillomavirus infections in a time-dependent manner in mice.

KEYWORDS: papillomavirus, mouse papillomavirus (MmuPV1), mucosal infections, cutaneous infection, anogenital tract, oral cavity, monoclonal antibody, passive immunization, neutralizing, in vivo, cutaneous, in situ analysis, mucosal, sex difference, sexually transmitted diseases

INTRODUCTION

In addition to cervical cancer, anal cancer, and some skin cancers, human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are increasingly implicated in head and neck cancers (1–4). Four vaccines have been approved for the prevention of HPV-induced diseases and cancers (5, 6). Unfortunately, uptake of the vaccines has been low, and unvaccinated individuals who are unable to clear the infections naturally will continue to be at risk of developing HPV-associated cancers (7). Few studies have reported the efficacy of HPV vaccines in HPV-associated diseases of the skin and anus (8, 9). This is due in part to two critical challenges. First, papillomaviruses are species specific; therefore, it is not possible to study HPV infections in any animal models. Second, papillomaviruses are tissue specific, and it is difficult to test the impact of vaccines on inoculations at different anatomical sites in the same host.

The discovery of the mouse papillomavirus (MmuPV1) in 2011 has advanced many studies in the papillomavirus research community (10–12). Although early reports focused on cutaneous tropism (13–17), we and others have demonstrated and reported mucosal infections with MmuPV1 (18–21). We have definitively demonstrated that, in addition to cutaneous sites, several HPV relevant mucosal sites, including oral, vaginal, anal, and penile tissues, are all highly susceptible to viral infections in athymic nude mice (11, 22–26). MmuPV1 induces productive anogenital infections and dysplasia (26) that mimic HPV-associated anogenital infections in humans (27, 28). MmuPV1 also infects the single circumvallate papilla of the mouse tongue (22), which corresponds to where HPV-induced oropharyngeal cancers in humans are commonly found (29, 30). Given the broad tissue tropism of MmuPV1 and its relevance to diverse HPV-associated diseases, this model is ideal for testing our hypothesis that passive immunization can provide protection at different tissue sites in the same animal (11).

Our hypothesis is built upon previous reports and observations. First, passive immunization with serum from either vaccinated or infected animals has been effective at blocking subsequent inoculations in the MmuPV1 model (31, 32). Second, papillomavirus shows delayed entry into cells in vitro, and viral transcription cannot be detected until 12 to 24 h post-viral inoculation (33, 34). Third, we have developed a panel of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against MmuPV1, including MAb MPV.A4, which demonstrated strong neutralizing ability in vitro (25). We postulate that viral inoculation can be blocked at both cutaneous and mucosal sites using neutralizing MAb MPV.A4 within a time window postinoculation. Our study is the first one to compare the responses of different tissues to a single neutralizing antibody against papillomaviruses in vivo.

The experiments were designed to answer two key questions: (i) will MAb MPV.A4 block MmuPV1 infections at both cutaneous and mucosal sites after viral inoculation, and if so, (ii) how long will MPV.A4 be protective post-viral inoculation? Active infections can be readily established in immunocompromised animals at both cutaneous and mucosal sites (11, 19, 26, 35); therefore, we used two athymic nude mouse strains in the current study to test our hypothesis. The mouse strains (Hsd:NU and NU/J) were treated with MAb MPV.A4 or a control antibody intraperitoneally (i.p.) or intravenously (i.v.) at various time points before and after MmuPV1 inoculations. Mucosal infections were monitored by quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of viral DNA in lavage/swab samples (23). In previous studies, we used this strategy successfully to monitor vaginal, penile, anal, and oral infections longitudinally (23, 25, 26, 35). Meanwhile, cutaneous infections were monitored by recording tumor growth weekly by photography. At the termination of the experiments, all inoculated tissues were further examined for subclinical infections by analyzing viral DNA/RNA copies by qPCR. In situ hybridization (ISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were also conducted to confirm the presence of viral DNA/RNA and viral proteins, including E4, in the infected tissues (25). Fully protected mice had undetectable levels of viral DNA/RNA by qPCR and in situ viral signals at both mucosal and cutaneous sites. Partially protected mice had no visible cutaneous lesions, but they did have detectable viral DNA/RNA representing subclinical infections (18, 35).

RESULTS

Complete protection was found in both male and female athymic nude mice treated with anti-MmuPV1 monoclonal antibody (MPV.A4) before viral inoculation.

For viral inoculation, we used a standard dose reported in our previous studies (25). For females, we tested two cutaneous sites (tail and muzzle) and three mucosal sites (vagina, anus, and tongue); thus each mouse received a total of 5 × 109 viral DNA equivalents for five inoculation sites. For males, we tested two cutaneous sites (tail and muzzle) and two mucosal sites (anus and tongue), so each mouse received a total of 4 × 109 viral DNA equivalents for four inoculation sites.

Two groups of female athymic Hsd:NU mice (n = 6/group) were administered MAb MPV.A4 or H11.B2 intraperitoneally (i.p.), as this delivery route was shown to be effective for passive immunization with mouse serum in previous studies (31, 32). All mice were subsequently inoculated with 1 × 109 viral DNA equivalents/per site at cutaneous sites (muzzle and tail) and mucosal sites (vagina, anus, and tongue) 24 h after either MPV.A4 or H11.B2 was given. As shown in Fig. 1, no visible lesions (0/6) were found in MPV.A4-treated mice, suggesting complete protection at cutaneous sites (tail and muzzle), while visible lesions were detected in animals given MAb H11.B2 (Fig. 1A) (P = 0.00216 for both sites, Fisher’s exact test). Significantly lower viral DNA copy numbers were detected in the three mucosal sites (vagina, anus, and tongue) of MPV.A4-treated mice compared to control MAb-treated mice (Fig. 1B) (P = 0.005, 0.00278, and 0.00434, respectively, Wilcoxon analysis). The infected tissues were further tested for viral activity by in situ hybridization (ISH). The control mice were positive for viral DNA in both cutaneous and mucosal sites (Fig. 1C), while no virus-positive cells were detected in all tissue sections from the MPV.A4-immunized mice (data not shown). These findings demonstrate that papillomavirus infection at both cutaneous and mucosal sites can be completely neutralized by a specific neutralizing MAb when administered 24 h before viral inoculation.

FIG 1.

MPV.A4 provided complete protection at both cutaneous and mucosal sites. HSD:NU nude mice were i.p. injected with either an anti-MmuPV1 monoclonal antibody, MPV.A4, or the control antibody H11.B2 24 h before viral inoculation. Complete protection was observed in the MPV.A4-treated mice at cutaneous tail and muzzle sites (A), and significantly lower viral DNA copy numbers were detected at all three tested mucosal sites (B) (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). Photographs and lavages were conducted biweekly, and the data shown are from week 6 after viral inoculation. (C) Tissues were collected at week 6 after viral inoculation. Viral DNA was detected in vaginal, tongue, and anal tissues of the control group by ISH (×20;, scale bar = 100 μm), while no viral DNA was detected in the MPV.A4-treated mice (not shown). A representative ISH tissue section is presented.

To further test whether the same protection could be achieved in male mice, in addition to Hsd:NU athymic mice (n = 2), two groups of two different nude mouse strains, JNU (n = 3) and NU/J (n = 3), were injected intraperitoneally with either MPV.A4 (0.3 mg/mouse) or an isotype control Mab, H18.J4 (a negative-control MAb that neutralizes HPV18) (0.3 mg/mouse) 24 h before viral inoculation. Each male mouse was subsequently inoculated with MmuPV1 virus (1 × 109 viral DNA equivalents/per site) at four sites, including two cutaneous (muzzle and tail) and two mucosal (anus and tongue) sites. Complete protection was found in the MPV.A4-treated Hsd:NU male mice compared with H18.J4-treated mice with no protection at all sites (data not shown). Due to the small number of Hsd:NU mice, we focused on statistical analysis of JNU and NU/J mice. For cutaneous sites, we recorded tumor growth up to 8 weeks post-viral inoculation. At the termination of the experiment, all inoculated tissues were harvested and quantitated for viral RNA by qPCR, as described previously (23). As shown in Table 1, all inoculated sites in the MPV.A4-treated group showed significantly lower levels of viral RNA than those in the H18.J4-treated group, suggesting MPV.A4 provided complete protection against MmuPV1 infection in different nude mouse strains when administered at 24 h before viral inoculation in males as well as females.

TABLE 1.

Statistical results of viral RNA copies in infected tissues between MPV.A4- and H18.J4-treated males at 24 h before viral inoculation (n = 3/group)

| Site | Significance fora: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Male RNA | Female GMD | |

| Muzzle | 0.0058* | 0.034* |

| Tail | 0.0026* | 0.0191* |

| Anus | 0.0058* | |

| Tongue | 0.0052* | |

*, P < 0.05 between MPV.A4 and H18.J4 treated (two-way ANOVA).

Complete protection was found in female athymic nude mice treated with anti-MmuPV1 monoclonal antibody (MPV.A4) at the time of viral inoculation.

Previous in vitro HPV inoculation studies demonstrated that 12 to 24 h was required for papillomavirus transcripts to be detected postinoculation (36). However, the length of time after viral inoculation during which the virus can be neutralized by passive immunization in vivo was unknown (36, 37). Hence, we wanted to ascertain whether animals could be protected by receiving neutralizing antibody at the time of viral inoculation.

Two groups of female Hsd:NU athymic mice (n = 3/group) were injected with 0.3 mg of either MPV.A4 or H18.J4, an isotype control that neutralizes HPV18. The antibodies were delivered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at the time of inoculation (time point 0) with 1 × 109 viral DNA equivalents/per site at both cutaneous (muzzle and tail) and mucosal (vagina, anus, and tongue) sites. For cutaneous sites, we recorded tumor growth up to 5 weeks post-viral inoculation. At the termination of the experiment, all infected tissues were harvested and quantitated for viral RNA/DNA by qPCR (23). All H18.J4-treated mice developed visible lesions at both the muzzle and tail (Fig. 2C), while none of the MPV.A4-treated mice had any visible lesions at the muzzle and tail (Fig. 2D). Figure 2A and B show complete absence of viral RNA and DNA in MPV.A4-treated mice, suggesting complete protection at both cutaneous and mucosal sites (Table 1) (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). Further immunohistochemical analyses also demonstrated the presence of viral E4 protein in both cutaneous and mucosal tissues of H18.J4-treated mice (Fig. 2E), while E4 was absent in corresponding MPV.A4-treated mice (Fig. 2F). In summary, all sites except the anus in female mice treated with MPV.A4 at the time of viral inoculation showed significantly lower viral DNA and viral RNA transcripts than those of the H18.J4-treated group, as determined by Wilcoxon rank sum tests (Table 2).

FIG 2.

Absence of viral activities was found in the inoculated cutaneous and mucosal sites of the female mice treated with MPV.A4 at the time of inoculation. Female Hsd:NU nude mice were injected intraperitoneally with MPV.A4 or control antibody (H18.J4) at the time of viral inoculation. Both cutaneous (tail and muzzle) and mucosal (vagina, anus and tongue) tissues were further analyzed for viral RNA(A)/DNA(B) by qPCR and in situ assays. No viral RNA (A) or DNA (B) was detected by qPCR in MPV.A4-treated mice. Three out of three females treated with MPV.A4 (D) at the time of inoculation were absent of visible muzzle and tail lesions, while three out of three H18.J4-treated mice developed visible lesions at both muzzle and tail (C). Viral E4 proteins (E, F) were absent in both cutaneous and mucosal tissues of MPV.A4-treated female mice (F), while these viral proteins were readily detected in both cutaneous and mucosal tissues of the control (H18.J4)-treated mice (E).

TABLE 2.

Statistical results from comparison of viral RNA copies between MPV.A4- and H18.J4-treated females at the time of viral inoculation (n = 3/group)

| Site | Significance fora: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA | DNA | GMD | |

| Muzzle | 0.00661* | 0.00974* | 0.00549* |

| Tail | 0.0128* | 0.00891* | 0.00389* |

| Anus | 0.117 | 0.112 | |

| Tongue | 0.00549* | 0.0484* | |

*, P < 0.05 between MPV.A4 and H18.J4 treated (Wilcoxon rank sum tests).

MPV.A4 provided partial protection for males at cutaneous sites, but offered no protection at mucosal sites when administered at the time of viral inoculation.

We therefore tested whether male mice are protected by passive immunization to the same extent as female mice. Two groups of Hsd:NU athymic male mice (n = 3) were injected intraperitoneally with either MPV.A4 (0.3 mg/mouse) or control H18.J4 (0.3 mg/mouse) at the time of viral inoculation. Each male mouse was inoculated with MmuPV1 (1 × 109 viral DNA equivalents/per site) at two cutaneous (muzzle and tail) and two mucosal (anus and tongue) sites. All three mice receiving H18.J4 developed visible lesions at both the muzzle and tail (Fig. 3A), while two out of three males treated with MPV.A4 (Fig. 3B) showed no visible muzzle and tail lesions. This result was unexpected, as we observed complete protection in females with the same dose of MPV.A4, especially considering that female mice were infected with more virus overall per animal (5 tested sites) compared to males (4 tested sites). We repeated the experiment with an additional two groups of male Hsd:NU mice (n = 5/group) injected with 0.3 mg of either MPV.A4 or H18.J4 at the time of viral inoculation. Again, four out of five MPV.A4-treated male mice had no visible lesions at the muzzle and tail at the termination of the experiment, while all five H18.J4-treated mice had visible lesions. However, significantly smaller lesions were found in both infected tail and muzzle tissues of MPV.A4-treated male mice when compared to those of H18.J4-treated mice (Fig. 3C, P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). The experiment was terminated at week 5 post-viral inoculation, and the infected tissues of all groups were further tested for viral RNA/DNA via qPCR analyses. Figure 3D and E show that comparable levels of viral RNA and DNA were detected in the infected tissues of MPV.A4- and H18.J4-treated male mice (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). Low levels of viral RNA/DNA were detected in the infected tongue tissues of the H18.J4-treated mice, possibly due to early termination of the experiment (5 weeks) and sampling as we harvested half of each tongue for RNA/DNA extraction and half for in situ assays. The targeted tissue for MmuPV1 infection is the single circumvent papilla of the tongue (22). To further observe viral presence in the infected tongues in these mice, we conducted additional in situ analyses on the second half of the harvested tongues of H18.J4-treated mice. As shown in Fig. 3F, viral DNA, RNA, and E4 protein (via in situ hybridization [ISH], RNA-ISH, and immunohistochemistry [IHC], respectively) were found in H18.J4-treated mice, indicating the establishment of productive infection. As Hsd:NU athymic mice are outbred, the individual variation may partially explain the low levels of detection in the test samples by qPCR (Fig. 3F). In summary, no inoculated sites of the MPV.A4-treated male mice showed significantly lower viral RNA/DNA levels compared to the H18.J4-treated group, although the average size of visible lesions in the MPV.A4 group was significantly smaller (Table 3) (Wilcoxon, P < 0.05 between MPV.A4 and H18.J4).

FIG 3.

MPV.A4 provided minimal protection for males at both cutaneous and mucosal sites. Male Hsd:NU mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti-MmuPV1 monoclonal antibody MPV.A4 or an isotype control (H18.J4) at the time of viral inoculation. Two out of three males treated with MPV.A4 (B) at the time of inoculation were absent of visible muzzle and tail lesions, while three out of three H18.J4-treated mice developed visible lesions at both muzzle and tail (A). The experiment was repeated, and two out of three males receiving MPV.A4 were absent of visible lesions at the tail and muzzle while all H18.J4-treated mice developed visible lesions. Significantly smaller lesions were found in the infected tissues of MPV.A4-treated when compared to those of H18.J4-treated male mice (C, P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). Viral RNA (E) and viral DNA (F) were quantitated by qPCR in harvested tissues at the termination of the experiment (week 5 after viral inoculation). Squares represent experiment 1, and circles represent experiment 2. The tongue tissues showed very low viral RNA/DNA by qPCR in the H18.J4 mice. To further determine the viral presence in these mice, we conducted additional in situ hybridization on the second half of infected tongue and detected viral DNA, RNA, and E4 protein by in situ hybridization, RNA in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry, respectively (D).

TABLE 3.

Statistical results from comparison of viral RNA copies between MPV.A4- and H18.J4-treated male groups (n = 8/group)

| Site | Significance fora: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA | DNA | GMD | |

| Muzzle | 0.0629 | 0.777 | 0.0227* |

| Tail | 0.0507 | 0.0558 | 0.0217* |

| Anus | 0.121 | 0.965 | |

| Tongue | 0.157 | 0.59 | |

*, P < 0.05 between MPV.A4 and H18.J4 treated (Wilcoxon rank sum tests).

Correlation of viral RNA and DNA levels with disease and visible lesions.

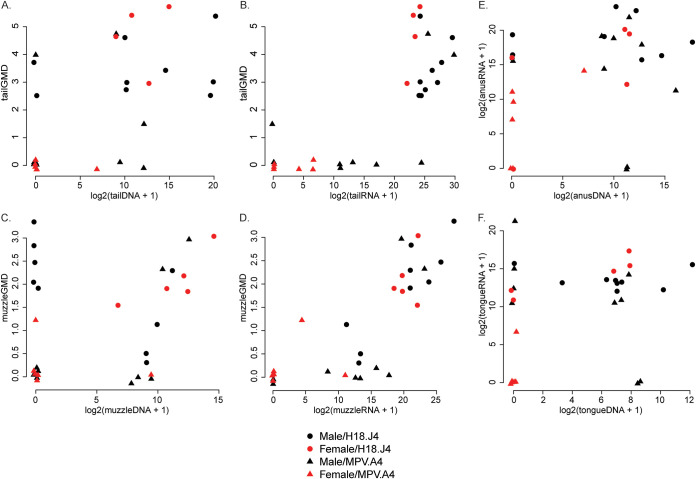

We assessed both viral RNA and DNA levels in the infected tissues especially the two cutaneous sites (tail and muzzle), where we were also able to evaluate lesion size. We used scatterplots (Fig. 4) and Spearman correlation coefficients to assess the strength of associations between different pairs of variables. The correlation of viral RNA with lesion size (geometric mean diameter [GMD] in millimeters) of both the tail (r = 0.694) (Fig. 4B) and muzzle (r = 0.836) (Fig. 4E) was stronger than the correlation of viral DNA level with lesion size of the tail (Fig. 4A) (r = 0.556) and muzzle (r = 0.375) (Fig. 4D), respectively. Viral RNA and viral DNA levels were moderately correlated in mucosal sites, including the anus (r = 0.373) and the tongue (r = 0.271), but were weakly correlated in infected tail (r = 0.237, Fig. 4C) and muzzle (r = 0.185, Fig. 4F) tissues.

FIG 4.

Correlation among viral RNA, DNA levels, and lesion size. Viral RNA and DNA levels in the infected tail (A and B) and muzzle (D and E) tissues were tested against the lesion size. As shown in panels A and D, viral DNA levels in tail and muzzle were higher in large lesions. Viral RNA levels (B and E) correlate well with lesion size and better than viral DNA (A and D). However, RNA and DNA did not correlate highly in both tail (C) and muzzle (F) tissues as well as those in mucosal sites (data not shown).

MPV.A4 was detected in the blood and at local sites in female and male mice.

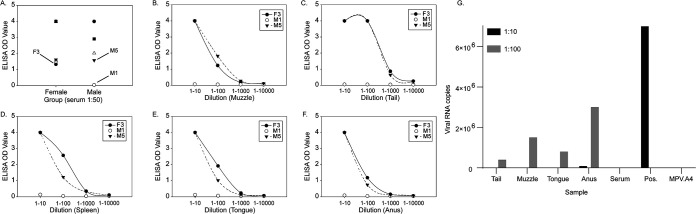

We postulate that poorer protection via passive immunization in males may result from lower levels of antibody circulating in the blood and delays in arriving at local inoculated sites. To test our hypothesis, we simultaneously administered 0.2 mg MPV.A4 and 0.04 mg H18.J4 intraperitoneally to five male (M1 to M5) and five female (F1 to F5) Hsd:NU athymic mice. We collected blood samples at 1, 6, and 24 h postadministration for antibody detection. All females had detectable MPV.A4 and H18.J4 at 1, 6, and 24 h post-i.p. administration (Fig. 5). One (M1) out of five males, however, had no detectable MPV.A4 (Fig. 5A) and H18.J4 (Fig. 5B) at all time points for unknown reasons. All five females and four out of five males were positive for both MPV.A4 and H18.J4 at 1 h postinjection, suggesting intraperitoneal delivery of both high and low doses of antibodies was effective and efficient in mice.

FIG 5.

Antibody detection after intraperitoneal delivery in the Hsd:NU athymic nude mice. Five female (red) and five male (blue) Hsd:NU athymic nude mice received 0.2 mg MPV.A4 and 0.04 mg H18.J4 mixture intraperitoneally. At 1, 6, and 24 h postadministration, blood samples were collected for MPV.A4 and H18.J4 detection by ELISA. All five females and four out of five males were positive for both MPV.A4 (A) and H18.J4 (B) at 1 h postinjection, suggesting the antibodies were transferred to the circulating system quickly.

To determine whether antibodies were successfully distributed to the locally wounded sites for viral inoculations in the above studies, we collected tissues (tail, muzzle, tongue, and anus) as well as spleens at 24 h post-i.p. delivery of antibodies. Using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), we analyzed all tissues of three mice (F3, M1, and M5) with the lowest signals in the serum test (Fig. 6A). The two positive serum samples (F3 and M5) showed comparable levels of MPV.A4 in all tested tissues (Fig. 6B to F), while the negative sample of M1 was also negative for MPV.A4 in all tested tissues. We further tested the neutralization ability of MPV.A4 in the serum and all tissues for M5. A dose-dependent inhibition of viral activity was found in all tested sites (Fig. 6G). Most tested sites were completely absent of viral RNA copies at a high concentration (1:10), except the anus, which was also the least protected site among all. Therefore, antibodies administered intraperitoneally can arrive at wounded tissues, leading to protection from MmuPV1 inoculation, especially at 24 h before viral inoculation. This is consistent with our passive immunization finding of complete protection in both female and male mice when the antibody was delivered 24 h before viral inoculation.

FIG 6.

Antibody detection in wounded tissues after intraperitoneal delivery. We further tested the serum (A) and local wounded tissues (tail, muzzle, tongue, and anus) as well as the spleens. They were collected at 24 h posttreatment for three animals (F3, M1, and M5). Two positive serum samples (F3 and M5) showed comparable MPV.A4 levels in all tested tissues (B to F), while the negative sample, M1, was also negative for MPV.A4 in all tested tissues. (G) Viral RNA was absent completely in most tested sites at a higher concentration (1:10) except the anus, which was also the least protected site among all.

We postulated that the failed appearance of MAb in males correlated with the body mass and therefore tested five female mice with equivalent body weight to the males. One out of five high-weight females also had no detectable MAb at all sites (data not shown), suggesting that body weight may have played a role in failed protection. Therefore, the failed protection in tested males when MPA.A4 was given at the time of viral inoculation may have been due to the absence of antibody at the locally wounded tissues.

Protection against MmuPV1 inoculation by MPV.A4 at time of viral inoculation is dose dependent.

As we observed complete protection in females but not males treated with MPV.A4 group at the time of inoculation, we hypothesized that a lower dose of MPV.A4 would be effective for protection in females. We tested a lower dose (0.03 mg) at the time of inoculation to determine whether using 10-fold-lower dose of MPV.A4 could also provide sufficient protection for females at both cutaneous and mucosal sites. To ensure delivery of all antibodies in the circulating system instantly, we administered antibodies intravenously (i.v.) via the tail vein instead of i.p. in this dose study.

Two groups of female Hsd:NU nude mice (n = 3/group) were included in the experiment. Low-dose MPV.A4 (0.03 mg) and H18.J4 control (0.3 mg) were administered intravenously at the time of viral inoculation. Five sites, including two cutaneous (muzzle and tail) and three mucosal (vagina, anus, and tongue) sites were inoculated with 1 × 109 viral DNA equivalents as described previously (25). Lavage samples from the mucosal sites were collected at week 4 post-viral inoculation for viral DNA quantification. The lesions on the tails and muzzles were recorded photographically. Tissues were harvested at week 6 post-viral inoculation for viral RNA/DNA quantification or in situ analyses. Animals given low-dose MPV.A4 had no visible lesions (Fig. 7C and D), as was the case in animals given high-dose MPA.A4 (Fig. 7A and B), while visible cutaneous lesions were found in the control H18.J4-treated group (Fig. 7E and F). Lavage fluids collected from the three mucosal sites (vagina, anus, and tongue) were tested at week 4 post-viral inoculation. Lower (but not statistically significant) levels of viral DNA were found in the low-dose MPV.A4 group compared with the control H18.J4 treatment group (Fig. 7I) (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). The infected tissues were further analyzed by immunohistochemistry, as shown in panels G (tail) and H (vagina). Viral E4 protein was readily detected in the H18.J4-treated mice but absent in the low-dose MPV.A4-treated mice. Viral RNA was further quantitated in the infected tissues by qPCR analysis. As shown in Fig. 7J, lower (but not statistically significant) levels of viral RNA were detected in the tail, muzzle, and vaginal tissues in the low-dose MPV.A4-treated mice (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). In agreement with our previous observations (23), the anus and tongue tissues in the control group showed lower levels of viral RNA at week 5 post-viral inoculation compared with the lower genital tract tissues, suggesting these two sites had a slow start for viral infections although both tissues can develop high-grade dysplasia after 9 months post-viral inoculation (22, 24). Subclinical infection without visible lesions in animals given the lower dose of MPV.A4 indicated viral suppression by neutralizing antibody to some extent; however, a lower dose of the neutralizing antibody was insufficient to completely block viral infection in these mice.

FIG 7.

A lower dose of MPV.A4 only provided partial protection at both cutaneous and mucosal sites of females. Three groups of Hsd:NU nude females (n = 3) were injected at the tail vein with MPV.A4 (high dose, 0.3 mg/mouse, and low dose, 0.03 mg/mouse) or an isotype control (H18.J4, 0.3 mg/mouse) at the time of viral inoculation. No visible lesions were observed in three out of three females in both the high-dose (A and B) and low-dose (C and D) MPV.A4-treated mice, while all control mice grew visible lesions at both muzzle and tail sites (E and F). Viral E4 proteins were detected in the control tail (G) and vaginal (H) tissues of H18.J4-treated mice and absent in corresponding tissues of both high-dose (0.3 mg) and low-dose (0.03 mg) MPV.A4-treated mice (I). Lower but not significantly lower levels of viral DNA were detected at all mucosal sites (vagina, anus, and tongue), even in the lower-dose group, than in the control group (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). (J) Viral RNA was quantitated by qPCR in harvested tissues, and significantly lower levels of viral RNA were not found in the low-dose MPV.A4-treated groups at two cutaneous sites and vaginal tissues compared with those in the H18.J4-treated groups (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). The tongue and anal tissues showed very low levels of viral RNA in both MPV.A4 and control mice.

Partial protection was found in athymic female nude mice treated with anti-MmuPV1 monoclonal antibody (MPV.A4) up to 6 h post-viral inoculation.

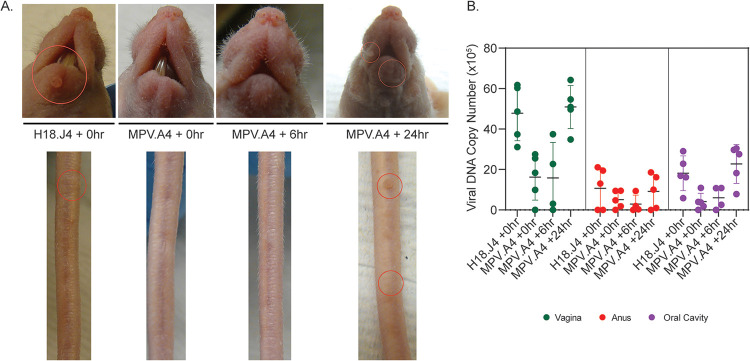

In our previous studies, we observed that different mouse strains showed differential responses to viral inoculation (11–14, 16, 38, 39). For athymic mice, we also found differences among strains. For example, NU/J nude mice were originally reported resistant to MmuPV1 inoculation at skin sites (13). Our study demonstrated positive but weaker infection at cutaneous sites of NU/J nude mice but vigorous infections at mucosal sites, including the development of carcinoma in situ at the lower genital tract (26). To test whether similar protection can be achieved by passive immunization and time course of protection post-viral inoculation, we used the NU/J nude mouse strain in the following time course experiment. As we observed better protection in female mice, the time course experiment was conducted in female mice. To ensure more efficient delivery of the antibody to infected sites, we administered MPA.A4 (0.3 mg) intravenously via the tail vein. We tested whether MPV.A4 antibody delivered 6 h and 24 h postinoculation would provide any protection as we observed protection in mice with antibody delivered at 0 h postinoculation.

Four groups of inbred NU/J nude female mice (n = 5/group) were inoculated with 1 × 109 viral DNA equivalents/per site at five sites, including two cutaneous (muzzle and tail) and three mucosal (vagina, anus, and tongue) sites. At 0, 6, and 24 h post-viral inoculation, one group was injected via tail vein with MPV.A4 (0.3 mg/mouse). The control group was injected i.v. with H18.J4 (0.3 mg/mouse) at the time of viral inoculation. Cutaneous infections were monitored by recording tumor growth, and mucosal infections were monitored by collecting lavage samples and analyzed by qPCR quantification.

All mice in the control group and 24 h postinoculation group treated with MPV.A4 grew visible lesions, even though these lesions were much smaller than those observed in Hsd:NU nude mice (Fig. 8A). In contrast, no lesions or minimal lesions were found in the 0- and 6-h-postinoculation groups, respectively. Similar results were observed in the mucosal sites. No significant difference in viral DNA in the lavage samples was observed between mice treated 24 h post-viral inoculation and those of control mice administered H18.J4 at the time of inoculation (time point 0) (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests) (see Table 5 below and Fig. 8B), however, significantly lower levels of viral DNA were found between the MPV.A4-treated group at 0 h and H18.J4 isotype control as well as the MPV.A4-treated mice at 24 h in vaginal and oral lavage samples (P = 0.00794 and 0.0159, respectively, Wilcoxon rank sum tests) (Table 4). Significantly lower levels of viral DNA were found between the MPV.A4-treated group at 6 h and 24 h in the vaginal samples (P = 0.0317), but not in the oral samples. No significant difference was found at all sites between the MPV.A4-treated group at 0 and 6 h post-viral inoculation (Table 5) (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests).

FIG 8.

Partial protection was observed in the MPV.A4-treated group up to 6 h post-viral inoculation. NU/J nude mice (n = 5) were injected in the tail vein with MPV.A4 or an isotype control (H18.J4) at 0, 6, and 24 h after viral inoculation. (A) Visible lesions were observed at tail and muzzle sites of the H18.J4 control group, but not in the MPV.A4-treated animals at 5 weeks post-viral inoculation. (B) Viral DNA from the lavage fluid collected at week 5 from individual animals was detected at three mucosal sites. A significant difference was found between the control and 0- and 6-h post-viral inoculation groups at the vaginal and oral sites (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). No significant difference was detected at the anal sites (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests).

TABLE 5.

Statistical analysis by comparing viral DNA from lavage samples of MPV.A4-treated mice at different times before and after viral inoculation

| Pair (n = 5/group) | Significance fora: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal | Anal | Oral | |

| H18.J4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 0 h | 0.00794* | 0.526 | 0.0159* |

| H18.J4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 24 h | 0.69 | 0.833 | 0.31 |

| H18.J4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 6 h | 0.0635 | 0.533 | 0.0635 |

| MPV.A4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 24 h | 0.00794* | 0.463 | 0.0159* |

| MPV.A4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 6 h | 1 | 0.461 | 1 |

| MPV.A4 at 24 h vs MPV.A4 at 6 h | 0.0317* | 0.325 | 0.0635 |

*, P < 0.05 between MPV.A4 and H18.J4 (Wilcoxon rank sum tests).

TABLE 4.

Statistical analysis between males (n = 6/group) and females (n = 3/group) in both MPV.A4- and H18.J4-treated groups

| Site | Significance fora: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA |

RNA |

GMD |

||||

| H18.J4 | MPV.A4 | H18.J4 | MPV.A4 | H18.J4 | MPV.A4 | |

| Muzzle | 0.0203* | 0.183 | 0.893 | 0.0332* | 1 | 0.736 |

| Tail | 1 | 0.206 | 0.0139* | 0.0355* | 0.147 | 0.152 |

| Anus | 0.585 | 0.00503* | 0.438 | 0.0739 | ||

| Tongue | 0.735 | 0.0416* | 0.947 | 0.0153* | ||

*, P < 0.05 between male and female mice (Wilcoxon rank sum tests).

Due to low viral DNA loads detected in the anal lavage fluid of all the groups, no significant difference was detected between MPV.A4- and H18.J4-treated control mice (Table 5) (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum tests). Overall, viral infection could be partially blocked up to 6 h post-viral inoculation at both cutaneous and mucosal sites, but the viral infection was already established in the inoculated sites by 24 h, at which time the antibody cannot clear preexisting infections. These results mimic the findings of HPV vaccines that show no protection against preexisting infections (5).

We further extracted RNA and DNA from the infected tissues of the 0- and 6-h post-viral inoculation group and the control group for viral RNA and DNA quantification at the termination of the experiment at week 9 post-viral inoculation. A significant difference was found among the groups (0 and 6 h and the H18.J4-treated group) in viral RNA and DNA at all sites, except tail and tongue, respectively (Table 6) (Kruskal-Wallis test). Consistent with the lavage data, no viral RNA was detected in the tail (0/5), muzzle (0/5), anus (0/5), and tongue (0/5) tissues from the mice passively immunized with MPV.A4 at 0 h. Two out of five MPV.A4-treated mice showed viral positivity of the vaginal tissues, and these were not significantly lower than those in the control mice (Fig. 9A). These observations parallel our findings in Hsd:NU nude mice described in experiments above. Additional paired analyses are reported in Table 7. In the 6-h post-viral inoculation group, viral RNA was absent in the tail (0/5) and very low in the anus, but detectable at the other sites. However, statistically significant lower levels of viral RNA were seen in the anal tissues between both the 0- and 6-h MPV.A4-treated group and the H18.J4 control group (Table 6) (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

TABLE 6.

Statistical analysis of viral DNA and RNA in tissues among MPV.A4 (0 and 6 h post-viral inoculation)- and H18.J4-treated groups

| Site | Significance fora: |

|

|---|---|---|

| RNA | DNA | |

| Tail | 0.127 | 0.0158* |

| Muzzle | 0.0334* | 0.00176* |

| Vagina | 0.00202* | 0.0334* |

| Anus | 0.0035* | 0.0205* |

| Tongue | 0.00628* | 0.148 |

*, P < 0.05 among different groups (Kruskal-Wallis test).

FIG 9.

Significantly lower levels of viral RNA and DNA were detected in tissues of the MPV.A4-treated group up to 6 h post-viral inoculation. Viral RNA (A) and viral DNA (B) in the infected tissues were quantified by qPCR, and MAb MPV.A4-treated animals were compared to Mab H18.J4 (control)-treated animals. Significance among the groups was calculated based on Wilcoxon rank sum tests, and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

TABLE 7.

Statistical analysis by comparing viral RNA detected from different tissues among MPV.A4- and H18.J4-treated mice

| Pair (n = 5/group) | Significance fora: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tail | Muzzle | Vagina | Anus | Tongue | |

| H18.J4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 0 h | 0.0668 | 0.0248* | 0.0065* | 0.00558* | 0.0065* |

| H18.J4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 6 h | 0.396 | 0.383 | NA | 0.0142* | 0.888 |

| MPV.A4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 6 h | 0.371 | 0.0404* | 0.0129* | 0.128 | 0.01* |

*, P < 0.05 between MPV.A4 and H18.J4 treated (Wilcoxon rank sum tests). NA not available.

Interestingly, significantly lower levels of viral DNA were detected in the 6-h treatment group, even though viral RNA was only significantly reduced at the anus (Table 7). A significant difference was also found between the 0-h and 6-h MPV.A4 treatment groups and the control (H18.J4) group for viral DNA at the tail, muzzle, and vaginal sites (Table 8) (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test), but not at the anus and tongue sites between the 6-h versus H18.J4-treated group (P > 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test) (Fig. 9B).

TABLE 8.

Statistical analysis by comparing viral DNA detected from different tissues among MPV.A4- and H18.J4-treated mice

| Pair (n = 5/group) | Significance fora: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tail | Muzzle | Vagina | Anus | Tongue | |

| H18.J4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 0 h | 0.0178* | 0.00558* | 0.0413* | 0.00994* | 0.072 |

| H18.J4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 6 h | 0.0334* | 0.0108* | 0.0334* | 0.434 | 1 |

| MPV.A4 at 0 h vs MPV.A4 at 6 h | 0.661 | 0.00721* | 1 | 0.102 | 0.131 |

*, P < 0.05 between MPV.A4 and H18.J4 treated (Wilcoxon rank sum tests).

Duration of monoclonal antibody in the blood after passive immunization.

A previous study suggested that passively transferred serum could be detected in the blood after several weeks postadministration in mice (31). To determine the stability of our monoclonal antibody in the serum of our tested animals, we collected serum of mice at the termination of the experiments (up to week 8 post-viral inoculation) and tested for MPV.A4 in the bloodstream. We detected positive samples from females with either i.p. or i.v. delivery and from male mice with i.p. delivery: 7/15, 11/14, and 3/10 mice, respectively. This suggests that MPV.A4 can be sustained for several weeks in both males and females. No significant difference was found among different delivery routes (i.p. versus i.v.) or sexes (male versus female). Most interestingly, all the mice treated with MPV.A4 at 24 h post-viral inoculation were found positive for MPV.A4, although no protection was found in these mice. This finding agrees with the findings that HPV vaccination offers no protection in existing HPV infected patients (5).

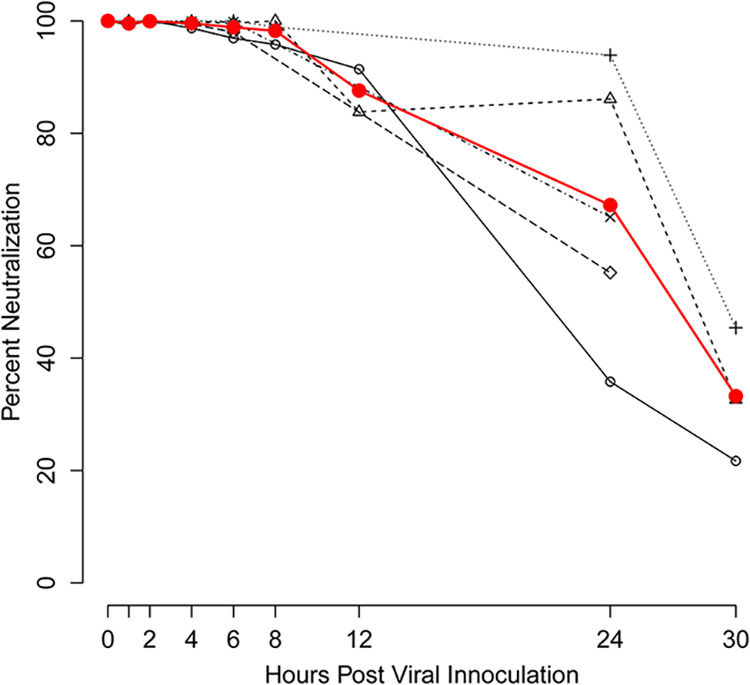

No viral transcripts were found in mouse keratinocytes up to 8 h post viral inoculation in vitro.

A previous study demonstrated that mouse papillomavirus pseudovirus could bind both HaCat and mouse keratinocytes and vaginal keratinocytes in vitro (37, 40). MPV.A4 can completely block MmuPV1 infection in mouse keratinocyte K-38 cells and in vivo (25, 41). We also detected that the binding of MmuPV1 to K-38 cells was inhibited by MPV.A4 in a dose- and time-dependent manner (data not shown). In parallel with the in vivo studies, we conducted a time course neutralization experiment in K-38 cells to determine viral entry time and to test MPV.A4 neutralization at different time points post-viral inoculation (+0, +2, +4, +6, +8, +10, +12, +24, and +30 h). This experiment was repeated several times for each time point. As seen in Fig. 10, cells were completely protected by the neutralizing MAb MPV.A4 at 8 h post-viral inoculation and about 90% protected at 12 h post-viral inoculation. This observation agrees with our previously reported findings that most of the virus could still be neutralized up to 30 h post-viral inoculation in vitro for HPV-11 and cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV), suggesting that MmuPV1 shares similar delayed entry characteristics to other papillomaviruses (42).

FIG 10.

MPV.A4 protected mouse keratinocytes against MmuPV1 inoculation up to 8 h post-viral inoculation. In vitro postattachment neutralization of MmuPV1 by MPV.A4 was conducted in mouse keratinocyte cell line K38. K38 cells were infected with MmuPV1 at 4°C. At different time points (1 to 30 h post-viral inoculation), K38 cells were washed, and 10 μg/mL MPV.A4 or negative controls was added (H16.V5 or H11.B2). The cells were harvested at 48 to 72 h post-viral inoculation, and RNA was extracted for MmuPV1 detection. E1^E4 transcripts were quantitated by qRT-PCR and plotted as a percentage of neutralization of MmuPV1 controls.

DISCUSSION

Papillomaviruses can only be propagated in vitro when supplied with differentiating epithelial cells to complete their life cycle (41). Currently no HPV animal infection model is available. Roberts et al. used an HPV16 pseudovirus (HPVL1/L2 capsid encapsidating a reporter gene) to study viral entry in the mouse vaginal epithelium, but this model was not capable of exploring natural virus infections (43). Several previous studies have used the HPV pseudovirus-mouse vaginal model to investigate the mechanism of neutralization in vivo (37). Although HPV16 capsids were able to deliver the reporter gene to mouse tissues, no productive HPV16 infection will occur, even if an HPV16 genome is encapsidated (44). Using the passive immunization strategy, they found neutralizing antibody against HPV16 was stable in serum and genital secretions between 24 and 72 h after i.p. injection in B6 mice and still effectively blocked pseudovirus-associated reporter DNA delivery (33).

The mouse papillomavirus (MmuPV1) model’s broad tissue tropism, mimicking diverse human papillomavirus infection, allowed us to answer two key questions that cannot be studied in a pseudovirus-mouse model. First, will passive immunization and, by extension, vaccination provide protection post-viral inoculation? If so, what is the window of time for successful neutralization of the virus with a neutralizing MAb? Previous studies demonstrated successful protection by passive immunization with neutralizing polyclonal serum before viral inoculation in the mouse model (31, 32). Whether post-viral immunization is protective remains unclear. Second, would passive immunization with neutralizing antibody offer equivalent protection against papillomavirus-associated diseases in different tissues? We have demonstrated both cutaneous and mucosal infections in several immunocompromised mouse strains, including two athymic nude mouse strains, which provides an ideal way to answer these two questions (11).

We tested protection of an in-house neutralizing MAb (MPV.A4) using two athymic nude mouse strains, outbred Hsd:NU and inbred NU/J nude mice, which develop visible lesions at cutaneous sites (muzzle and tail) and productive infections at mucosal sites by quantitating viral RNA and DNA in longitudinal lavage samples (26). These two mouse strains, however, have shown some differences in disease outcomes (11, 26, 35). Hsd:NU athymic mice grew more and larger lesions than NU/J athymic mice at the cutaneous sites, while NU/J athymic mice showed more advanced disease after MmuPV1 inoculations at the mucosal sites, especially the genital tract, within a given time frame post-viral inoculations (26). These two mouse strains are complementary and suitable to study both cutaneous and mucosal infections.

In agreement with previous studies that serum generated from VLP-vaccinated animals can passively immunize mice 24 h before viral inoculation (31), we also tested 4- and 24-h passive immunizations before viral inoculation using MPV.A4 by both i.p. and i.v delivery methods. Both males and females demonstrated protection against MmuPV1 infections at both cutaneous and mucosal sites when receiving MPV.A4 prior to viral inoculation. Mice that received MPA.A4 at 24 h post-viral inoculation were not protected from viral infections. These findings agree with the previous report that neutralizing antibodies have no therapeutic effect like that reported in humans (5).

It is interesting to determine the rate and timing of the antibody that appears in the circulating blood and how long it can remain in circulation. In our current study, we demonstrated that MPV.A4 can be detected in the blood at 1 h post-i.p. injection and up to 8 weeks in some animals. These data support the observed protection in mice that received MPA.A4 at the time of viral inoculation. Also of note is that the neutralizing antibody did not provide protection in the anus in females, while other tested tissues showed a significant reduction in both viral RNA and viral DNA when neutralizing antibody was added at the time of viral inoculation. This differential site protection by passive immunization has not been reported previously and warrants further investigation.

We observed four out of six male mice that lacked visible lesions on the tail and muzzle after MPV.A4 treatment. However, compared with the control group, none of the tested tissues had significantly different levels of viral RNA and viral DNA, suggesting only partial protection was provided by the neutralizing antibody at the time of inoculation. We further demonstrated that failed protection in males may result from the absence of neutralizing antibodies in tested tissues. We tested whether i.v. delivery of MPV.A4 would improve the protection in males, and similar results were observed, suggesting the delivery route was not key for this observed sex difference (data not shown). As we delivered the same amount of MPV.A4 to males and females, this observation may suggest even higher levels of antibody are needed for males, even though we infected only four sites in males, while five sites were infected in females.

Several explanations are postulated for this observed sex bias in passive immunization. First, we also failed to detect antibody in one out of five female mice that have equivalent body weight to males, suggesting body mass might play a role in Hsd:NU athymic mice. This problem could be resolved with a dose based on body weight in future studies. Second, a reported study showed that blood clearance of input IgG2a correlates with low endogenous IgG2a levels in many nude mouse strains, including Hsd:NU athymic mice (45). The investigators detected high levels of heterogeneity in male blood IgG2a. Coincidently, MPV.A4 and H18.J4 are both mouse IgG2a antibodies. We postulate additionally, that these two input antibodies were cleared rapidly in the males that failed to show antibodies in the blood and tested tissues. To test this hypothesis, we can use a neutralizing antibody of a different isotype to determine whether isotype IgG2a played a role in the failed protection in these males. Third, we postulated that the observed sex difference is related to the mouse strain. To test this hypothesis, we tested five male and five female C57BL/6 mice. Interestingly, all five females and five males were positive for MPV.A4 in both blood and spleen at 48 h post-i.p delivery, suggesting effective delivery of antibodies in these B6 mice (data not shown). Therefore, the mouse strain may also contribute to our current observations. We also acknowledge that more studies need to be conducted to gain a better understanding of other possible mechanisms underlying the observed sex differences. For example, sex hormones (both male and female) and/or receptors (estrogen receptors alpha and beta) may play a role and thus need further investigation.

Interestingly, antibody infused at 6 h post-viral inoculation also provided partial protection in females. This result demonstrates that at least some virus had not entered cells at this time point and supported the findings of others that papillomavirus entry can be a protracted process (36, 41). The mechanism of in vivo neutralization of HPV by neutralizing antibody was reported in a previous study (33). Using a passive serum transfer strategy, investigators demonstrated that the initial steps of in vivo HPV inoculation took place on the basement membrane (BM), in contrast to the extracellular matrix (ECM), as described for in vitro cell culture inoculations (46). They found that it took 4 h post-viral inoculation to detect BM binding although substantial binding of virions by neutrophils was found at 4 h post-viral inoculation (33). Our findings suggest that the internalization of MmuPV1 can be delayed up to 6 h post-viral inoculation. Our in vitro neutralization assay further supports that virus can be neutralized up to 8 h post-viral inoculation. Not surprisingly, MPV.A4 failed to protect mice at 24 h post-viral inoculation (47). This observation further validates the previous findings that current prophylactic vaccines cannot clear preexisting HPV infections in humans (48).

Our previous studies have shown viral DNA quantification of longitudinally collected lavage samples from mucosal sites could be used to monitor viral activities and disease progression (23). Our current study further proved that both viral DNA and RNA could be used to measure viral activities in both lavage and local tissue samples. However, viral RNA correlated better with inoculations and lesions at the cutaneous sites than viral DNA. We postulate that the discrepancy may result from the viral extraction method (TRIzol), which might not be optimal for viral DNA detection. In general, viral RNA is more sensitive than viral DNA in viral detection in tissues with low viral activities. Therefore, viral RNA could be an additional parameter to be included to increase the accuracy of monitoring lower viral activities in tissues.

We have previously reported some differences in disease outcome in two athymic nude mouse strains, especially at cutaneous sites (26). Consistent with what we previously reported, NU/J athymic mice had smaller lesions (tail and muzzle) compared to Hsd:NU athymic mice in the control group (13, 26). We included both nude mouse strains for the current study and showed similar protection at both cutaneous and mucosal sites at the time of viral inoculation in female mice. Therefore, both mouse strains are appropriate for passive immunization studies. As we did not detect any viral transcripts in the fully protected mice, we believe that passive immunization using a neutralizing antibody following viral inoculations is effective. However, the time window of antibody protection is within a few hours of initial virus inoculation.

In summary, this is the first in vivo study to investigate passive immunization against viral inoculations in multiple tissues simultaneously using a single monoclonal antibody. Findings from this study provide opportunities to further study the mechanisms of antibody blocking papillomavirus infections and clearance in different tissues. These results will further strengthen the utility of this unique MmuPV1 mouse model to investigate diverse human papillomavirus-associated disease progression, immunological responses, and virus-host interactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viral stock.

Infectious virus was isolated from lesions on the tails of mice from our previous studies (18). In brief, the lesions were scraped from the tail with a scalpel blade and homogenized in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), using a Polytron homogenizer (Brinkman PT10-35) at the highest speed for 3 min, while chilling in an ice bath. The homogenate was spun at 10,000 rpm, and the supernatant was decanted into Eppendorf tubes for storage at –20°C. For these experiments, the virus was diluted 1:5 in 1× PBS, and 200 μL was passed through a 0.2-μm-pore cellulose acetate sterile syringe filter. This was chased by the addition of 200 μL 1× PBS. The 1× PBS filtrate was added to the filtered virus to give a total of 250 μL sterile virus solution when taking into account loss in the filter. Viral DNA was quantitated by extraction of the DNA from 5 μL of this stock. One microliter of the DNA extract contains 1 × 108 viral genome equivalents. About 1 × 109 viral DNA genome equivalents were used for each inoculation site (49).

Animals and viral inoculations.

All mouse work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Pennsylvania State University’s College of Medicine (COM), and all methods were performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations. Hsd:NU (outbred, Foxn1nu/nu) mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were obtained from Envigo, J/NU (outbred, Foxn1nu/nu), NU/J (inbred, Foxn1nu/nu), and C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. All animals were housed (2 to 5 mice/cage) in sterile cages within sterile filter hoods and were fed sterilized food and water in the COM biosafety level 2 (BSL2) animal core facility. Mice were sedated intraperitoneally (i.p) with 0.1 mL/10 g body weight with a ketamine-xylazine mixture (100 mg/10 mg in 10 mL double-distilled water [ddH2O]). For vaginal inoculation, female mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 3 mg medoxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera; Pfizer) in 100 μL PBS 3 days before the viral inoculation, as previously described (24, 49). The vaginal and anal tracts were wounded with The Doctors’ BrushPicks coated with nonoxynol (Conceptrol; Ortho Options [over the counter]). For the tail and muzzle, a blade was used to scarify the skin, as described previously (50). For tongue inoculation, tongues were withdrawn using sterile forceps, and microneedles were used to wound the ventral surface of the tongues (22). Care was taken to minimize the bleeding. Twenty-four hours after wounding, the mice were again anesthetized and challenged with 10 μL (1.0 × 109 viral DNA genome equivalents/site) of the sterilized viral suspension at both cutaneous sites (tail and muzzle) and mucosal sites (the vaginal for female and anal and tongue for both sexes). The muzzle and tail, vaginal (for females), anal, and ventral surface of the tongues was again gently wounded, and 10 μL of sterile virus was applied to the freshly abraded surfaces. Animals were placed on their backs during recovery to minimize loss of virus from the inoculated sites. Monitoring was conducted weekly, and a photographic log was created for each animal (23).

Monoclonal antibody generation and purification.

Mouse papillomavirus virus-like particles (VLPs) were used as the antigen for immunization in mice. We generated several anti-MmuPV1 monoclonal antibodies in the laboratory and tested their ability to neutralize viral inoculation in vitro. One such monoclonal antibody, MPV.A4, showed effective neutralization in mouse keratinocyte cells (25). We first tested whether MPV.A4 could neutralize viral inoculation in vivo via passive immunization. For this pilot study, we used 0.5 mg of unpurified MPV.A4 supernatant and a negative-control antibody, H11.B2 (a monoclonal antibody that neutralizes HPV11 infectivity), intraperitoneally (i.p.) at 4 h before viral inoculation, as described in previous passive immunization studies using mouse serum (31, 32). Female athymic Hsd:NU mice (n = 4/group) were subsequently inoculation with 1 × 109 viral DNA equivalents/per site at cutaneous sites (muzzle and tail) and mucosal sites (lower genital tract, anal tract, and oral cavity) at 4 h after antibody administration. Two out of four MPV.A4-treated animals were completely protected at all infected sites, while no protection was found in all four animals in the H11.B2-treated control group (data not shown). We concluded that MPV.A4 was capable of neutralizing in vivo viral inoculation, but the unpurified MPV.A4 we administered was a suboptimal dose that was not sufficient to neutralize all the input virus. We therefore proceeded with additional studies using purified antibody. Both anti-MmuPV1 monoclonal antibody (MPV.A4) and controls (H11.B2 and H18.J4) were adapted into serum-free medium (Gibco) and purified on protein A affinity columns (Thermo-Fisher Pierce). These purified antibodies were used for both in vivo and in vitro studies (51).

Determination of the dose of anti-MmuPV1 L1 monoclonal antibody (MPV.A4) for passive immunization in vivo.

To determine the dose required for complete protection against viral infection for MPV.A4 to neutralize viral inoculation in vivo, we used purified MPV.A4 that was first tested in an in vitro neutralization assay (25). We calculated that approximately 0.03 mg antibody would be needed to neutralize 5 × 108 viral DNA equivalents in vitro (data not shown). When we administered 0.3 mg of purified MAb MPV.A4 or control antibody, we delivered a theoretical dose to sufficiently neutralize a total of 5 × 109 viral DNA equivalents for each female mouse as well as each male mouse, which would receive 4 × 109 viral DNA equivalents in total. We therefore used 0.3 mg purified monoclonal antibody MPV.A4 and two controls (H11.B2 and H18.J4, two MAbs that neutralize HPV11 or HPV18, respectively) for most experiments, except the dose experiment.

Antibody detection in the blood and local tissues.

Hsd:NU athymic or C57BL/6 mice of both sexes were simultaneously administered 0.2 mg MPV.A4 and 0.04 mg H18.J4 intraperitoneally. Blood samples were collected at different times (1, 6, 24, and 48 h) postadministration for antibody detection. At 24 or 48 h postadministration, we also collected tissues (tail, muzzle, tongue, and anus) and spleens. All tissues were minced and resuspended in 200 mL of sterile 1×PBS. The supernatant of different dilutions was used for antibody detection using our routine ELISAs as described previously (51).

Vaginal, anal, and oral lavage for DNA extraction.

The vaginal, anal, and oral lavages/swabs were conducted using 25 μL of sterile 0.9% NaCl introduced into the vaginal and anal canals (35). The rinse was gently pipetted in and out of the vaginal canal and stored at −20°C before being processed. For oral and anal lavages, a swab (Puritan PurFlock Ultra; Puritan Diagnostics, LLC) soaked in 25 μL of sterile 0.9% NaCl was used. For DNA extraction, the DNeasy kit (Qiagen) was used according to the instructions of the manufacturer. All DNA samples were eluted into 50 μL EB buffer.

Viral DNA and transcript copy number analysis.

Linearized MmuPV1 genomic DNA was used for standard curve determination by a probe qPCR system. The primer pairs (5′-GGTTGCGTCGGAGAACATATAA-3′ and 5′-CTAAAGCTAACCTGCCACATATC-3′) that amplify E2 were used together with the probe (5′-6-carboxyfluorescein [FAM]-TGCCCTTTCA/ZEN/GTGGGTTGAGGACAG-Iowa black fluorescent quencher [IBFQ]-3′). Each reaction mixture consisted of 9 μL of ultrapure water, 5 pmol of each primer, 9 μL of Brilliant III qPCR master mix (Agilent), and 2 μL of DNA template. The PCR conditions were initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min and then 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 s and at 60°C for 10 s and reactions were run on an Agilent AriaMx. Viral copy numbers were converted into equivalent DNA load using the formula 1 ng viral DNA = 1.2 × 108 copy numbers (http://cels.uri.edu/gsc/cndna.html). For lavage samples, 2 μL of the 50-μL DNA extracts of each lavage was used for qPCR (35). For the tissue samples, 100 ng total DNA was used for qPCR. All samples were tested in at least duplicates. Viral titers were calculated according to the standard curve (23).

RNA and DNA were extracted from tissues by homogenization in TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) using a Polytron homogenizer (Brinkman PT10-35) for 60 s at speed 6. The protocol for TRIzol reagent extraction of RNA followed by DNA was followed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Viral RNA (E1^E4 transcripts) was quantitated using primers (5′-TAGCTTTGTCTGCCCGCACT-3′ and 5′-GTCAGTGGTGTCGGTGGGAA-3′ and probe 5′-FAM-CGGCCCGAAGACAACACCGCCACG-6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine [TAMRA]-3′). Two hundred nanograms of RNA was reverse transcribed using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo-Fisher), and 2 μL cDNA was used in the qPCR analysis. A 500 nM concentration of each primer and 250 nM probe were used with the Brilliant III qPCR kit (Agilent) on an Agilent AriaMx qPCR machine under the following qPCR conditions: 95°C for 3 min and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 10 s.

In vitro neutralization assay.

Cells of the spontaneously immortalized mouse keratinocyte cell line K38 (a generous gift from Julia Reichelt, University of Newcastle, United Kingdom) (52) were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells per well in E-medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and nystatin and were cultured with mitomycin C-treated (Enzo Life Sciences) J2 3T3 feeder cells, as previously described (53). One microliter of viral extract from our MmuPV1 stock (1 × 108 genome DNA equivalent) was used for infection of K38 cells. For the neutralizing assay of serum or supernatant of tissues harvested in the monoclonal tracking experiment, the virus was incubated with different dilutions of supernatant at 37°C for 1 h before being added into a 12-well plate well for each sample. The RNA was quantitated as described above for tissues. In the time point study, the virus was incubated with the cells at 4°C for 1 h. Cells were washed 1× with medium, and then 10 μg/mL MAb (MPV.A4, H18.J4, or H11.B2) was added to cells at different time points (1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, and 30 h). The cells were incubated at 37°C for 3 additional days after the initial virus binding step and harvested with TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies). Total RNA was extracted from the infected cells, and infectivity was assessed by measuring viral E1^E4 transcripts with qRT-PCR E1^E4-forward (5′-CATTCGAGTCACTGCTTCTGC-3′), E1^E4-reverse (5′-GATGCAGGTTTGTCGTTCTCC-3′), and E1^E4-probe (5′-FAM-TGGAAAACGATAAAGCTCCTCCTCAGCC-TAMRA-3′), as previously described, with a few modifications as follows. The Brilliant III Master mix kit (Agilent) was used for the quantitative reverse transcription-PCRs (qRT-PCRs) and carried out on an Agilent AriaMx. The following cycling conditions were applied: 50°C for 10 min (reverse transcription), 95°C for 3 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 10 s. The viral RNA copy numbers were calculated with a standard curve, as described previously (21). The neutralization rate was calculated based on several repeated experiments and compared to that of virus alone.

Immunofluorescence detection.

K38 cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells per well on glass coverslips in a 12-well plate in E medium. The next day, 5 μg CsCl-purified MmuPV1 was either added directly to cells or incubated with 10 μg/mL MPV.A4 for 1 h before being added to cells for 1 h. MPV.A4 was added at indicated time points (0, 1, or 2 h) after MmuPV1 addition. Following incubation, cells were fixed in cold methanol for 5 min. Coverslips were blocked with 5% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 (BSA/PBS/T). A mixture of MPV.A4 and MPV.B9 (both detecting L1 of MmuPV1) at a 1:100 dilution each was incubated to detect bound MmuPV1. After 3 washes with PBS/T, secondary goat anti-mouse 488 (1:1,000; Life Technologies) and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (1:100) were added. Following 3 washes, coverslips were inverted and mounted onto glass slides with ProLong Gold antifade mountant (Invitrogen no. P36930). Images were taken by a wide-field fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Imager Z2, Axiocam 506 mono) using Zeiss Zen Blue/Pro software. These images were further processed by ImageJ 1.8.0 (NIH, Bethesda, MD). All images from samples of different groups were taken with identical microscope settings and adjusted uniformly.

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization analyses of infected tissues.

After termination of the experiment, the animals were euthanized, and tissues of interest were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, as described previously. Adjacent sequential sections were cut for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) analyses, in situ hybridization (ISH), RNA in situ hybridization (RNA-ISH), and immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses, as described in previous studies (25). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against MmuPV1 E4 protein was a generous gift from John Doorbar’s group. For ISH, a biotin-labeled 3,913-bp EcoRV/BamH1 subgenomic fragment of MmuPV1 was used as the probe for the detection of MmuPV1 DNA in tissues (24). Access to target DNA was obtained following incubation with 0.2 mg/mL pepsin in 0.1 N HCl at 37°C for 8 min. After thorough washing, the biotinylated probe was applied and heated to 95°C for 5 min to achieve dissociation of target and probe DNA. Reannealing was allowed to occur for 2 h at 37°C. Target-bound biotin was detected using a streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (AP) conjugate, followed by colorimetric development in BCIP/NBT (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate–nitroblue tetrazolium). Counterstaining for ISH was performed with Nuclear Fast Red (American MasterTech, Inc.). Viral RNA expression was detected in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues by RNAscope technology (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Inc.), using custom probes that mapped within the second exon of the E1^E4 open reading frame (ORF) (nucleotides [nt] 3139 to 3419) with RNAscope 2.5 VS Probe-V-MusPV-E4 following the manufacturer’s protocol. After hybridization, the bound probes were detected by colorimetric staining using the RNAscope 2.5 HD assay—Brown and counterstained with hematoxylin. For IHC, an in-house rabbit anti-MmuPV1 E4 polyclonal antibody (John Doorbar’s lab) or anti-MmuPV1 L1 antibody (an in-house mouse monoclonal antibody, MPV.B9) was used on FFPE sections. Detection was achieved using the ImmPRESS anti-rabbit IgG polymer system (Vector no. MP-7801) or M.O.M. (Mouse on Mouse) ImmPRESS HRP (peroxidase) polymer kit (Vector number MP-2400) using ImmPACT NovaRED substrate (SK-4805). Before mounting, the slides were counterstained with 50% hematoxylin Gill’s no. 1 solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.02% ammonium hydroxide solution (Sigma-Aldrich) (25, 35, 54).

Statistical analysis.

For experiments with a small sample size (n < 3/group), a permutation-based approach was used to compare RNA-based viral counts at various sites between MPV.A4- and H18.J4-treated groups. The geometric means of length by width by height ± standard error of the mean (SEM) in millimeters (25) of lesions of infected tails and muzzles were similarly analyzed (55). In brief, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) models without interaction were fit for a given outcome variable using the factors strain (JNU versus NU/J) and treatment (MPV.A4 versus H18.J4), and the F test statistic corresponding to the equality of the marginal means for treatment was recorded. Corresponding test statistics were recorded after applying random permutations to the outcome variable. Permutations were restricted to preserve the strain in order to control for any variability across strains. A total of 1e4 random permutations were used for each outcome variable, and the permutation-based test statistics were utilized to assess the significance of the observed test statistics. Random seeds were set for each permutation in order to guarantee reproducible results. For most other experiments, Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to perform two group comparisons of viral DNA copy numbers from lavage sites or DNA and RNA viral levels from tissue samples: e.g., in male versus female for a given treatment type or H18.J4 versus MPV.A4 in female mice. Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied to perform similar comparisons in three or more groups, followed by Wilcoxon rank sum tests for pairwise comparisons of interest. The association between treatment group and the presence of lesions on cutaneous sites was examined with Fisher’s exact test. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to examine associations between log-transformed viral DNA, log-transformed viral RNA levels, and tumor volume. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant, and no adjustment was made for multiple testing because of the exploratory nature of this study. R 4.0.2 (56) was used to perform all statistical analyses. Figures were generated using R 4.0.2, GraphPad Prism 8, SigmaPlot, or Graphics.

Data availability.

The data supporting the finding of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award no. R21AI121822 (N. D. Christensen and J. Hu), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under award no. 1R21DE028650 (J. Hu), National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award no. 1 R21 CA271069 (J. Hu), the Jake Gittlen Memorial Golf Tournament, Penn State Cancer Institute Program Project Development Award sponsored by the Highmark Community Health Reinvestment Fund, and the Pathology Department Research Fund.

We thank John Doorbar for providing polyclonal anti-MmuPV1 E4 antisera.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Jiafen Hu, Email: fjh4@psu.edu.

Lawrence Banks, International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benevolo M, Dona MG, Ravenda PS, Chiocca S. 2016. Anal human papillomavirus infection: prevalence, diagnosis and treatment of related lesions. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 14:465–477. 10.1586/14787210.2016.1174065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shigeishi H, Sugiyama M. 2016. Risk factors for oral human papillomavirus infection in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med Res 8:721–729. 10.14740/jocmr2545w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gravitt PE, Winer RL. 2017. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of viral latency. Viruses 9:267. 10.3390/v9100267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khoury R, Sauter S, Butsch Kovacic M, Nelson AS, Myers KC, Mehta PA, Davies SM, Wells SI. 2018. Risk of human papillomavirus infection in cancer-prone individuals: what we know. Viruses 10:47. 10.3390/v10010047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roden RBS, Stern PL. 2018. Opportunities and challenges for human papillomavirus vaccination in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 18:240–254. 10.1038/nrc.2018.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razzaghi H, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, Henley SJ, Viens L, Wilson R. 2018. Five-year relative survival for human papillomavirus-associated cancer sites. Cancer 124:203–211. 10.1002/cncr.30947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shanmugasundaram S, You J. 2017. Targeting persistent human papillomavirus infection. Viruses 9:229. 10.3390/v9080229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deshmukh AA, Chhatwal J, Chiao EY, Nyitray AG, Das P, Cantor SB. 2015. Long-term outcomes of adding HPV vaccine to the anal intraepithelial neoplasia treatment regimen in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis 61:1527–1535. 10.1093/cid/civ628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshmukh AA, Chiao EY, Das P, Cantor SB. 2014. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination in HIV-negative men who have sex with men to prevent recurrent high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Vaccine 32:6941–6947. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingle A, Ghim S, Joh J, Chepkoech I, Bennett Jenson A, Sundberg JP. 2011. Novel laboratory mouse papillomavirus (MusPV) infection. Vet Pathol 48:500–505. 10.1177/0300985810377186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu J, Cladel NM, Budgeon LR, Balogh KK, Christensen ND. 2017. The mouse papillomavirus infection model. Viruses 9:246. 10.3390/v9090246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uberoi A, Lambert PF. 2017. Rodent papillomaviruses. Viruses 9:362. 10.3390/v9120362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundberg JP, Stearns TM, Joh J, Proctor M, Ingle A, Silva KA, Dadras SS, Jenson AB, Ghim SJ. 2014. Immune status, strain background, and anatomic site of inoculation affect mouse papillomavirus (MmuPV1) induction of exophytic papillomas or endophytic trichoblastomas. PLoS One 9:e113582. 10.1371/journal.pone.0113582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handisurya A, Day PM, Thompson CD, Bonelli M, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 2014. Strain-specific properties and T cells regulate the susceptibility to papilloma induction by Mus musculus papillomavirus 1. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004314. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uberoi A, Yoshida S, Frazer IH, Pitot HC, Lambert PF. 2016. Role of ultraviolet radiation in papillomavirus-induced disease. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005664. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang RT, Wang JW, Peng S, Huang TC, Wang C, Cannella F, Chang YN, Viscidi RP, Best SRA, Hung CF, Roden RBS. 2017. Spontaneous and vaccine-induced clearance of Mus musculus papillomavirus 1 infection. J Virol 91:e00699-17. 10.1128/JVI.00699-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue XY, Majerciak V, Uberoi A, Kim BH, Gotte D, Chen X, Cam M, Lambert PF, Zheng ZM. 2017. The full transcription map of mouse papillomavirus type 1 (MmuPV1) in mouse wart tissues. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006715. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cladel NM, Budgeon LR, Cooper TK, Balogh KK, Hu J, Christensen ND. 2013. Secondary infections, expanded tissue tropism, and evidence for malignant potential in immunocompromised mice infected with Mus musculus papillomavirus 1 DNA and virus. J Virol 87:9391–9395. 10.1128/JVI.00777-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spurgeon ME, Uberoi A, McGregor SM, Wei T, Ward-Shaw E, Lambert PF. 2019. A novel in vivo infection model to study papillomavirus-mediated disease of the female reproductive tract. mBio 10:e00180-19. 10.1128/mBio.00180-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spurgeon ME, Lambert PF. 2019. Sexual transmission of murine papillomavirus (MmuPV1) in Mus musculus. eLife 8:e50056. 10.7554/eLife.50056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scagnolari C, Cannella F, Pierangeli A, Mellinger Pilgrim R, Antonelli G, Rowley D, Wong M, Best S, Xing D, Roden RBS, Viscidi R. 2020. Insights into the Role of Innate Immunity in Cervicovaginal Papillomavirus Infection from Studies Using Gene-Deficient Mice. J Virol 94. 10.1128/JVI.00087-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cladel NM, Budgeon LR, Balogh KK, Cooper TK, Hu J, Christensen ND. 2016. Mouse papillomavirus MmuPV1 infects oral mucosa and preferentially targets the base of the tongue. Virology 488:73–80. 10.1016/j.virol.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu J, Budgeon LR, Cladel NM, Balogh K, Myers R, Cooper TK, Christensen ND. 2015. Tracking vaginal, anal and oral infection in a mouse papillomavirus infection model. J Gen Virol 96:3554–3565. 10.1099/jgv.0.000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cladel NM, Budgeon LR, Balogh KK, Cooper TK, Hu J, Christensen ND. 2015. A novel pre-clinical murine model to study the life cycle and progression of cervical and anal papillomavirus infections. PLoS One 10:e0120128. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cladel NM, Jiang P, Li JJ, Peng X, Cooper TK, Majerciak V, Balogh KK, Meyer TJ, Brendle SA, Budgeon LR, Shearer DA, Munden R, Cam M, Vallur R, Christensen ND, Zheng ZM, Hu J. 2019. Papillomavirus can be transmitted through the blood and produce infections in blood recipients: evidence from two animal models. Emerg Microbes Infect 8:1108–1121. 10.1080/22221751.2019.1637072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cladel NM, Budgeon LR, Balogh KK, Cooper TK, Brendle SA, Christensen ND, Schell TD, Hu J. 2017. Mouse papillomavirus infection persists in mucosal tissues of an immunocompetent mouse strain and progresses to cancer. Sci Rep 7:16932. 10.1038/s41598-017-17089-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]