Abstract

The Helicobacter pylori genome encodes four penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). PBPs 1, 2, and 3 exhibit similarities to known PBPs. The sequence of PBP 4 is unique in that it displays a novel combination of two highly conserved PBP motifs and an absence of a third motif. Expression of PBP 4, but not PBP 1, 2, or 3, is significantly increased during mid- to late-log-phase growth.

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral, gram-negative bacterium which causes chronic superficial gastritis and is associated with peptic ulcer disease, gastric carcinoma, and gastric lymphoma (2, 19, 22–24). H. pylori appears to be unique in that a number of typical cytoplasmic proteins, including urease, heat shock proteins A and B (HspA and HspB), catalase, and superoxide dismutase, are associated with the outer membrane (4, 6–8, 14, 26, 32). Surface-adsorbed urease (most likely derived from autolyzed bacteria) appears to be essential for survival of H. pylori at pH 2, a condition routinely encountered by the bacterium in the human stomach (7, 16, 26).

Autolytic mechanisms in bacteria presumably involve disruption of the peptidoglycan (PG) layer, since it is the backbone of the cell structure. The enzymes capable of degradation and synthesis of PG can be classified into two broad classes, penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) and non-PBPs (11, 21). In general, PBPs capable of degrading PG exhibit endopeptidase and/or carboxypeptidase activity (33, 34). In this communication, we describe a novel H. pylori PBP with unique properties.

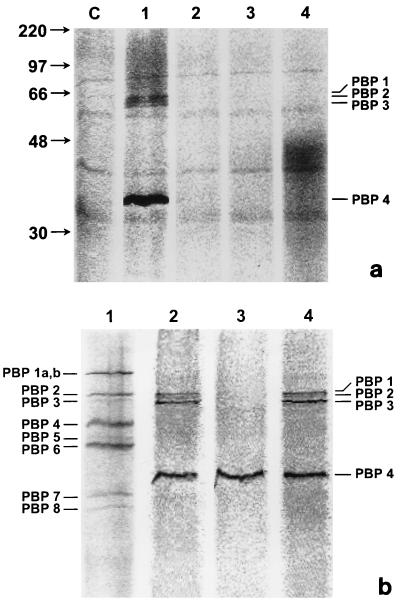

To identify H. pylori PBPs, fluorescein-C6-aminopenicillanic acid (Flu-6-APA) was prepared and used to covalently label permeabilized bacteria grown on agar plates (10, 26, 29). Protein preparations normalized for total protein were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (5, 18, 30). For detection of Flu-6-APA-labeled proteins, gels were scanned in a Fluorimager. In H. pylori 84-183, four PBPs, ranging in molecular mass from 32 to 66 kDa, were identified. Three high-molecular-weight PBPs were in the size range (55 to 66 kDa) of PBPs A, B, and C, described by Ikeda et al. (15) (Fig. 1a, lane 1). We refer to PBPs A, B, and C as PBPs 1, 2, and 3, respectively, since in general PBPs are labeled numerically rather than alphabetically (34). A fourth low-molecular-weight PBP, of approximately 32 kDa (PBP 4), not identified by Ikeda and colleagues was observed consistently in our preparations (Fig. 1a, lane 1). As a negative control to confirm that PBPs in whole-cell extracts bind to the penicillin moiety of Flu-6-APA and not to the fluorescein moiety, whole-cell extracts were incubated with fluorescein-di-galactose. Neutral hydroxylamine specifically removes penicillin (and thereby fluorescein) from PBPs (3). Disappearance of PBPs after treatment with neutral hydroxylamine was used as an additional control. No protein bands were visible with fluorescein-di-galactose labeling, indicating that there is no nonspecific binding of proteins to the fluorescein label (Fig. 1a, lanes 3 and 4). Similarly, no protein bands were visible after treatment of Flu-6-APA-treated protein samples with neutral hydroxylamine (Fig. 1a, lane 2), further confirming the specificity of PBP binding to Flu-6-APA. The fluorescence intensity of PBP 4 was consistently greater than that of the other three PBPs, most likely due to increased expression of PBP 4 compared to the other three PBPs (see below). Pretreatment of whole cells with EDTA did not inhibit the ability of PBP 4 to bind to Flu-6-APA, indicating (data not shown) that metal ions are not required for penicillin binding; hence, PBP 4 is unlikely to be related to metallo-β-lactamases (25).

FIG. 1.

(a) PBP profile of H. pylori. Flu-6-APA-labeled H. pylori whole-cell extracts were separated by SDS–12% PAGE; the molecular mass standards are indicated in kilodaltons. Lane C, no Flu-6-APA added (negative control); lane 1, H. pylori 84-183 labeled with 10 μM (final concentration) Flu-6-APA; lane 2, H. pylori 84-183 labeled with 10 μM (final concentration) Flu-6-APA and then treated with hydroxylamine (hydroxylamine treatment disrupts the covalent linkage with PBPs, resulting in release of the label); lane 3, H. pylori 84-183 labeled with 10 mM fluorescein-di-galactose; lane 4, H. pylori 84-183 labeled with 100 mM fluorescein-di-galactose. PBPs 1, 2, and 3, seen in lane 1, presumably represent PBPs A, B, and C, respectively, as reported by Ikeda et al. (15). (b) Distribution of PBP 4 between membrane and soluble fractions. H. pylori 84-183 membrane and soluble fractions normalized for total protein content were labeled with Flu-6-APA, and equal amounts of total proteins were analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE. Lane 1, E. coli K-12 strain MC1061 whole cells (16); lane 2, H. pylori 84-183 whole-cell extracts; lane 3, H. pylori soluble fraction; lane 4, H. pylori membrane fraction.

During characterization of PBP 4, we noticed significant loss of PBP 4 signal in membrane preparations compared with whole cells. Therefore, we investigated the possibility that PBP 4 might be distributed in both the membrane and the soluble (nonmembrane) fractions due to mechanical separation of loosely bound PBP 4 from the bacterial membrane fraction during centrifugation. H. pylori 84-183 membrane and soluble fractions were prepared (28) after harvesting of bacteria from agar plates into phosphate-buffered saline. Figure 1b shows that unlike most PBPs (11–13), PBP 4 of H. pylori is present both in membrane fractions and in soluble fractions. By analogy with E. coli PBP 4, it is likely that a fraction of H. pylori PBP 4 is loosely associated with the membrane and that this association is disrupted during biochemical preparation of the membrane and soluble fractions (17). In contrast, the high-molecular-weight PBPs of H. pylori were observed exclusively in membrane preparations (Fig. 1b). There is no apparent difference between the molecular weights of PBP 4 present in these two fractions.

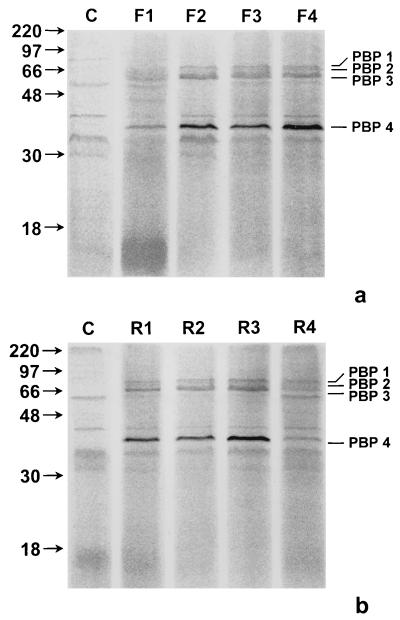

We investigated the possibility that PBP 4 expression might vary with the growth phase, since PBP 4 was not detected in very early log phase cultures (12 h) of H. pylori by Ikeda et al. (15). For this purpose, H. pylori 84-183 early-log-phase (24-h), mid-log-phase (48-h), late-log-phase (72-h), and extremely late-log-phase (96-h) cultures were harvested (16) and whole cells were labeled with Flu-6-APA. As seen in Fig. 2, a distinct difference in the total amounts of PBP 4 present in a fresh subculture and a repeated subculture is noticeable. In freshly subcultured bacteria, the amount of PBP 4 is low in early-log-phase cultures and increases in mid- to late-log-phase cultures (Fig. 2a). In contrast, in repeatedly subcultured H. pylori 84-183, expression levels of PBP 4 are similar from early through late log phase while decreasing in extreme late log phase (Fig. 2b). Expression levels of the three high-molecular-weight PBPs, however, are similar in freshly and repeatedly subcultured H. pylori at all growth stages (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Time course of PBP 4 expression. (a) H. pylori 84-183 (fresh subculture) whole cells harvested at early (24-h), mid (48-h), late (72-h), and extremely late (96-h) log phase were normalized for total protein content and labeled with Flu-6-APA, and an equal amount of total protein was analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE. Lane C, no Flu-6-APA added; lane F1, early-log-phase (24-h) culture; lane F2, mid-log-phase (48-h) culture; lane F3, late-log-phase (72-h) culture; lane F4, extremely late-log-phase (96-h) culture. (b) H. pylori 84-183 (repeat subculture) whole cells harvested at early (24-h) mid (48-h), late (72-h), and extremely late (96-h) log phase were normalized for total protein content and labeled with Flu-6-APA, and an equal amount of total protein was analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE. Lane C, no Flu-6-APA added; lane R1, early-log-phase (24-h) culture; lane R2, mid-log-phase (48-h) culture; lane R3, Late-log-phase (72-h) culture; Lane R4, extremely late-log-phase (96-h) culture.

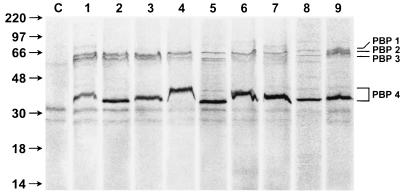

H. pylori PBP 4 was detected in all strains analyzed. The size of PBP 4 varied from 30 to 36 kDa between different strains, as seen in Fig. 3. There was also some variation in the profile of high-molecular-weight PBPs. The significance of this variation is currently unknown but is consistent with the significant genetic variability present in H. pylori genes (9). In all strains tested, the amount of fluorescence associated with PBP 4 was relatively greater than that of the high-molecular-weight PBPs.

FIG. 3.

Size variation of PBP 4 in different strains. Whole cells from different H. pylori strains were normalized for total protein content and labeled with Flu-6-APA, and an equal amount of total protein was analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE. Lane C, no Flu-6-APA added; lane 1, strain CK44; lane 2, strain HH12; lane 3, strain RJ17; lane 4, strain GS; lane 5, strain N6; lane 6, strain WV8D3; lane 7, strain A5; lane 8, strain HM; lane 9, strain 84-183. Lanes 1 to 4 and lanes 6 and 8 are fresh clinical strains which were obtained from human subjects undergoing endoscopy for dyspeptic symptoms and have been minimally passaged in the laboratory. Lanes 5, 7, and 9 are laboratory strains which, although initially isolated from humans, have been extensively passaged in the laboratory (16).

H. pylori PBP 4 was purified on a penicillin affinity column (3). The PBPs eluted from the affinity column were separated by gel electrophoresis. Based on silver staining of the resultant gel, the amount of PBP 4 purified from the affinity column was significantly greater than that of the three high-molecular-weight PBPs, suggesting that quantitatively more PBP 4 is present in H. pylori (data not shown). The low-molecular-weight PBP 4 was subjected to N-terminal sequencing (20, 30). A single N-terminal sequence, ??GEKYFKMANQALK, was obtained from both membrane and soluble fractions. The first two residues of PBP 4 could not be identified by N-terminal sequencing.

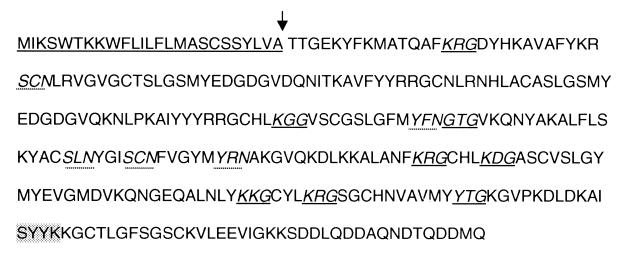

The PBP 4 protein is encoded by open reading frame (ORF) HP0160 and JHP148 according to the TIGR and ASTRA H. pylori genome sequence databases, respectively (Fig. 4) (1, 35). The PBP 4 gene encodes a 306-amino-acid protein (Fig. 4) that is rich in cysteine (4.5%) and has a predicted molecular mass of 34 kDa (ORF HP0160 [35]). The predicted molecular mass of the mature form of PBP 4 (25-amino-acid signal sequence processed form) is 31,189 Da. There are two amino acid substitutions in the N-terminal amino acid sequences of PBP 4 between H. pylori 84-183 and 26695. The predicted N-terminal amino acid sequence of PBP 4 from H. pylori J99 is identical to the N-terminal amino acid sequence of strain 84-183, as reported above (1). The sequence of PBP 4 shows no homology to any known PBP or proteins from other bacteria.

FIG. 4.

Deduced amino acid sequence of PBP 4 protein (ORF HP0160). The sequence begins with an initiation methionine. The signal peptidase cleavage site is denoted by an arrow, and the signal peptide sequence is underlined. The PBP 4 sequence lacks the conserved KTG motif. However, several regions in the PBP 4 sequence differ from the conserved KTG motif. However, several regions in the PBP 4 sequence differ from the conserved KTG motif by a single residue; these sites are italicized and underlined. Possible SXN motifs are italicized and marked with dotted underlines. The active site of all known PBPs (SXXK) is highlighted (36).

There are three possible explanations for the lack of detection of PBP 4 by Ikeda et al. (15). First, they used 14C-labeled penicillin to detect PBPs whereas we used Flu-6-APA labeling to analyze PBPs. However, since we were able to detect much more silver-stainable PBP 4 in our purification procedures (which do not rely on binding of Flu-6-APA to PBPs) relative to the three high-molecular-weight PBPs, it is unlikely that the method used for labeling is the source of the difference. The second difference between these two studies is that our cultures were routinely grown on blood agar plates, while Ikeda et al. used liquid broth cultures. The third difference between our PBP studies and those of Ikeda et al. is the culture age of the bacterial sample. Ikeda et al. (15) used a very early log phase (12-h) culture for their protein isolations, while we routinely used late-log-phase (72-h) cultures in our assays. Interestingly, expression of PBP 4 appears to be minimal in early-log-phase cultures and maximal in older cultures. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that all of the PBP 4 in the membrane preparations employed by Ikeda et al. (15) was present in a form loosely associated with the cell membrane and was therefore not detected.

Analysis of the genome sequence from H. pylori 26695 (35) or J99 (1) indicates that the protein sequence of PBP 4 belongs to a family of seven paralogous genes (on the basis of moderate sequence similarity [P = 10−50]) that are scattered throughout the genome (27). At least one member of this family, HcpA, is expressed in H. pylori ATCC 49503 (27). We were unable to detect penicillin binding to any member of this family (except PBP 4) in any of the strains examined. Therefore, the significance of above sequence similarity is unclear. In contrast to the sequence of PBP 4, sequence similarity searches of the H. pylori genome have identified three genes (ORFs HP 597, 1556, and 1565 in the TIGR genome database [35] and ORFs JHP 544, 1464, and 1473 in the ASTRA genome database [1]) that show significant homologies to PBPs from other bacteria (13, 34). These three ORFs are likely to correspond to PBPs 1, 2, and 3, as identified by Ikeda et al. (15) and in the present study.

Catalytic centers of PBPs have a remarkably well-conserved topology, and the residues involved in penicillin binding are referred to as motifs: motif 1 (SXXK), motif 2 [S(Y)XN(C], and motif 3 [K(H,R)T(S)G] comprise the catalytic center (13, 34). In all PBPs identified to date, these three motifs are arranged in a specific order from the N to C termini within PBPs, with motif 1 being the first in the order followed by motif 2 and then motif 3 (13, 34). The sequence of PBP 4 from strain 26695 (35) shows a single conserved SXXK motif. However, the sequence of PBP 4 from strain J99 (1) shows two SXXK motifs, one of which is in the same position as that in strain 26695. We have verified the sequence of the PBP 4 gene in strain 26695 (by direct DNA sequencing of PCR fragments) and have found no differences from the reported sequence (data not shown). The sequences of PBP 4 from both strains show conserved SXN motifs but not the conserved K(H,R)T(S)G motif. Further, in the sequence of PBP 4 the SXXK motif is present near the C terminus following the SXN motif (Fig. 4). The significance of the unique arrangement of PBP motifs in PBP 4 is not known.

Based on the lack of sequence similarity with known PBPs and the unique arrangement of the PBP motifs, PBP 4 may carry out a unique reaction(s) and/or may contribute to the spiral morphology of H. pylori (19). When a low-molecular-weight PBP (PBP G) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa with extensive homology to Escherichia coli d,d-endopeptidase (PBP 4 of E. coli) is overproduced in E. coli, lysis of cells results (31). It is worth pointing out that H. pylori PBP 4 is a low-molecular-weight PBP and appears to be overproduced compared to PBPs 1, 2, and 3. Additional experiments are required to determine the function(s) of PBP 4 in H. pylori. At present, we are analyzing the composition of H. pylori PG to determine the structure of the possible substrate for PBP 4.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the comments and suggestions of Raoul S. Rosenthal, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. A portion of this work was completed as part of an independent study course undertaken by C.W. at the Marquette University Department of Biology.

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grants CA67527 and DK39045 (B.E.D.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alm R A, Ling L L, Moir D T, King B L, Brown E D, Doig P C, Smith D R, Noonan B, Guild B C, DeJonge B L, Carmel G, Tummino P J, Caruso A, Uria-Nickelsen M, Mills D M, Ives C, Gibson R, Merber D, Mills S D, Jiang Q, Taylor D E, Vovis G F, Trust T J. Genomic sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature (London) 1998;397:176–180. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaser M J. Hypotheses on the pathogenesis and natural history of Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:720–727. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90126-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumberg P M, Strominger J L. Covalent affinity chromatography of penicillin-binding components from bacterial membranes. Methods Enzymol. 1974;34:401–405. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(74)34046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bode G, Malfertheiner P, Lehnhardt G, Nilius M, Ditschuneit H. Ultrastructural localization of urease of Helicobacter pylori. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1993;182:233–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00579622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn B E, Sung C C, Taylor N S, Fox J G. Purification and characterization of Helicobacter mustelae urease. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3343–3345. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3343-3345.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn B E, Vakil N B, Schneider B G, Miller M M, Zitzer J B, Peutz T, Phadnis S H. Localization of Helicobacter pylori urease and heat shock protein in human gastric biopsies. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1181–1188. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1181-1188.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eschweiler B, Bohrmann B, Gerstenecker B, Schlitz E, Kist M. In situ localization of the 60 k protein of Helicobacter pylori, which belongs to the family of heat shock proteins, by immuno-electron microscopy. Int J Med Microbiol Virol Parasitol Infect Dis. 1993;280:73–85. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80942-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foxall P A, Hu L T, Mobley H L. Use of polymerase chain reaction-amplified Helicobacter pylori urease structural genes for differentiation of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:739–741. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.3.739-741.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galleni M, Lakaye B, Lepage S, Jamin M, Thamm I, Joris B, Frere J M. A new, highly sensitive method for the detection and quantification of penicillin-binding proteins. Biochem J. 1993;291:19–21. doi: 10.1042/bj2910019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georgopapadakou N H. Penicillin-binding proteins and bacterial resistance to β-lactams. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2045–2053. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.10.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghuysen J M. Serine beta-lactamases and penicillin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:37–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goffin C, Ghuysen J M. Multimodular penicillin binding proteins: an enigmatic family of orthologs and paralogs. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1079–1093. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1079-1093.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawtin P R, Stacey A R, Newell D G. Investigation of the structure and localization of the urease of Helicobacter pylori using monoclonal antibodies. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1995–2000. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-10-1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda F, Yokota Y, Mine Y, Tatsuta M. Activity of cefixime against Helicobacter pylori and affinities for the penicillin-binding proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2426–2428. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.12.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnamurthy P, Parlow M, Zitzer J B, Vakil N B, Mobley H T, Levy M, Phadnis S H, Dunn B E. Helicobacter pylori containing only cytoplasmic urease is susceptible to acid. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5060–5066. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5060-5066.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korat B, Mottl H, Keck W. Penicillin-binding protein 4 of Escherichia coli: molecular cloning of the dacB gene, controlled overexpression, and alterations in murein composition. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:675–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall B J. Helicobacter pylori: a primer for 1994. Gastroenterologist. 1993;1:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsudaira P. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanninga N. Cell division and peptidoglycan assembly in Escherichia coli. Mol Miocrobiol. 1991;5:791–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nomura A, Stemmermann G N, Chyou P H, Kato I, Perez-Perez G I, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1132–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parsonnet J, Friedman G D, Vandersteen D P, Chang Y, Vogelman J H, Orentreich N, Sibley R K. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L, Gelb A B, Warnke R A, Jellum E, Orentreich N, Vogelman J H, Friedman G D. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1267–1271. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405053301803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Payne D J, Bateson J H, Gasson B C, Khushi T, Proctor D, Pearson S C, Reid R. Inhibition of metallo-beta-lactamases by a series of thiol ester derivatives of mercaptophenylacetic acid. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:171–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phadnis S H, Parlow M H, Levy M, Ilver D, Caulkins C M, Connors J B, Dunn B E. Surface localization of Helicobacter pylori urease and a heat shock protein homolog requires bacterial autolysis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:905–912. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.905-912.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ping C, Mcclain M S, Forsyth M H, Cover T L. Extracellular release of antigenic proteins by Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1988;66:2984–2986. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2984-2986.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popham D L, Setlow P. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and mutagenesis of the Bacillus subtilis ponA operon, which codes for penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 1 and a PBP-related factor. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:326–335. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.2.326-335.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popham D L, Setlow P. Phenotypes of Bacillus subtilis mutants lacking multiple class A high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2079–2085. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2079-2085.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song J, Xie G, Elf P K, Young K D, Jensen R A. Comparative analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa penicillin-binding protein 7 in the context of its membership in the family of low-molecular-mass PBPs. Microbiology. 1998;144:975–983. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-4-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spiegelhalder C, Gerstenecker B, Kersten A, Schlitz E, Kist M. Purification of Helicobacter pylori superoxide dismutase and cloning and sequencing of the gene. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5315–5325. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5315-5325.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spratt B G. Distinct penicillin binding proteins involved in the division, elongation, and shape of Escherichia coli K12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:2999–3003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.8.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spratt B G, Cromie K D. Penicillin-binding proteins of gram-negative bacteria. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:699–711. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomb J F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature (London) 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waxman D J, Strominger J L. Penicillin-binding proteins and the mechanism of action of beta-lactam antibiotics. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:825–869. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.004141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]