Abstract

We report a diastereoconvergent synthesis of anti-1,2-amino alcohols bearing N-containing quaternary stereocenters using an intermolecular direct C–H amination of homoallylic alcohol derivatives catalyzed by a phosphine selenide. Destruction of the allylic stereocenter during the selenium-catalyzed process allows selective formation of a single diastereomer of the product starting from any diastereomeric mixture of the starting homoallylic alcohol derivatives, eliminating the need for the often-challenging diastereoselective preparation of starting materials. Mechanistic studies show that the diastereoselectivity is controlled by a stereoelectronic effect (inside alkoxy effect) on the transition state of the final [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement, leading to the observed anti selectivity. The power of this protocol is further demonstrated on an extension to the synthesis of syn-1,4-amino alcohols from allylic alcohol derivatives, constituting a rare example of 1,4-stereoinduction.

We report a diastereoconvergent synthesis of anti-1,2-amino alcohols bearing N-containing quaternary stereocenters using an intermolecular direct C–H amination of homoallylic alcohol derivatives catalyzed by a phosphine selenide.

Introduction

The prevalence of stereodefined 1,2- and 1,4-amino alcohol motifs in pharmaceuticals and asymmetric catalysts has generated a need for stereocontrolled synthesis of these structures.1 Direct C–H functionalization is now a state-of-the-art strategy for the synthesis of 1,2-amino alcohols, allowing introduction of new C–N or C–O bonds without prefunctionalization at that carbon atom.2 In this context, a variety of transition-metal catalyzed3 and radical-mediated4 C–H amination approaches to 1,2-amino alcohols have been reported. Although these methods provide efficient access to these compounds, little attention has been paid to the diastereoselectivity1,3a–c,5 of these transformations, especially intermolecular aminations, or to the construction of quaternary heterosubstituted stereocenters.6 Additionally, diastereoselective synthesis of 1,4-amino alcohols via direct C–H functionalization has not been reported.

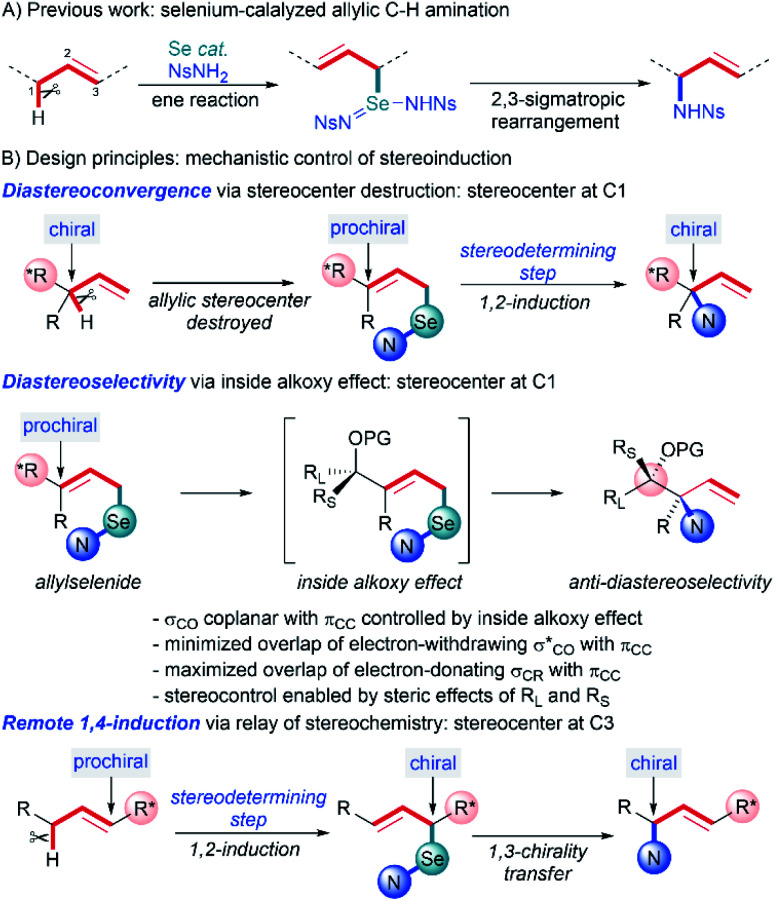

We previously reported a metal-free allylic amination catalyzed by phosphine selenides that proceeds via a mechanism distinct from most other C–H functionalizations.7 Initial ene reaction between an imidoselenium species cleaves the C–H bond and transposes the alkene, and a subsequent [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement delivers the new C–N bond (Scheme 1A). This “flip-flop” mechanism has several distinct properties that enable new modes of diastereocontrol without requiring intramolecular delivery of the nitrogen group: (i) C–H bond cleavage and C–N bond formation occur in separate steps, (ii) both steps are concerted and proceed suprafacially, (iii) initial activation of the C C bond by Se takes place distal to the C–H bond being functionalized, and (iv) there is no allylic transposition of the intermediate, allowing either step to be stereodetermining depending on the substrate. Careful analysis of these key elements reveals that the presence of an oxygen-substituted stereocenter attached to either C1 or C3 of the allyl system would enable diastereoselective synthesis of 1,2- and 1,4-amino alcohols that are difficult to access using current C–H amination methods.

Scheme 1. Stereoselectivity analysis of selenium-catalyzed C–H amination.

When the stereocenter is attached to C1 (Scheme 1B), the allylic stereocenter in starting material is destroyed in the ene reaction, and then formed anew in the stereodetermining [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement, thus enabling a diastereoconvergent process whereby a single diastereomer can be accessed from diastereomeric mixtures of the starting material. In contrast, the stereospecificity of most C–H nitrenoid insertion approaches3d–o would require diastereomerically pure starting materials that are often challenging to access8 (Scheme 2A).

Scheme 2. Diastereoselective synthesis of 1,2-amino alcohols via direct C–H functionalization.

Second, the stereodetermining [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement now takes place in close proximity to the controlling stereocenter, allowing unprecedented diastereoselectivity via steric and/or electronic differentiation of the prochiral faces of the alkene (Scheme 1B). We hypothesized that an analog of the “inside alkoxy effect”9 might control the orientation of the C–O stereocenter in the transition state. Minimizing overlap of the  orbital with the π system would stabilize the relatively electron-poor transition state, allowing delivery of the nitrogen to the less sterically hindered face and thereby giving high anti selectivity. This is complementary to the syn selectivity observed for known methods3a–c,10 resulting from intramolecular delivery of a tethered nitrogen group (Scheme 2B).

orbital with the π system would stabilize the relatively electron-poor transition state, allowing delivery of the nitrogen to the less sterically hindered face and thereby giving high anti selectivity. This is complementary to the syn selectivity observed for known methods3a–c,10 resulting from intramolecular delivery of a tethered nitrogen group (Scheme 2B).

Alternately, when the stereocenter is attached to C3, the stereodetermining step switches to the initial ene reaction. In this step, attack of the selenium now occurs alpha to the stereocenter, allowing diastereoselectivity via 1,2-induction (Scheme 1B). This stereochemistry is then selectively transferred to the distal center in the suprafacial [2,3]-rearrangement. In this scenario, initial 1,2-stereoselection is efficiently relayed into remote 1,4-induction. Remote stereoinduction of this type is difficult to achieve.11

Herein, we disclose a diastereoconvergent synthesis of anti-1,2-amino alcohols bearing N-containing quaternary stereocenters via intermolecular direct C–H amination of homoallylic alcohol derivatives under metal-free conditions. We show that high diastereoselectivity is observed in the formation of 1,2-amino alcohols without quaternary centers as well. We also demonstrate the application of this protocol to remote 1,4-induction, resulting in the synthesis of syn-1,4-amino alcohols from (Z)-allylic alcohol derivatives (Scheme 2C).

Results and discussion

To test the feasibility of this approach, we started with a 1 : 1 mixture of diastereomers of homoallylic ester 1a as the model substrate. Our previously reported standard conditions for allylic amination gave the desired amination product, but in a disappointing 15% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Both conversion and overall mass recovery were low. Notably, we found that addition of an insoluble base is crucial to the success of the reaction. The role of this base is still unclear, but we hypothesize that trace acids formed under these conditions may partially decompose the starting material and/or product. A screen of basic additives revealed that Li2CO3 was optimal, giving product 2a in 79% yield (Table 1, entry 2). Conversely, an acid additive lowers the conversion (Table 1, entry 5). Importantly, the starting 1 : 1 diastereomeric mixture in substrate 1a was converted to a 10 : 1 mixture of diastereomeric products 2a. The steric size of the protecting group has a minor effect on the diastereoselectivity, with acetate giving somewhat lower selectivity than pivalate (Table 1, entry 3).

Optimization for anti-1,2-amino alcohols.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Change | 1aa (%) | Yield (%) d.r.a |

| 1 | Ref. 7a conditions | 30 | 15 |

| 2 | None | 0 | 79 (10 : 1) |

| 3 | Ac instead of Piv | 0 | 70 (6 : 1) |

| 4 | No Li2CO3 | 20 | 14 |

| 5 | p-Nitrobenzoic acid instead of Li2CO3 | 42 | 15 |

Yields and diastereomeric ratio (d.r.) determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3-dinitrobenzene as internal standard.

Importantly, as hypothesized, the relative configuration of the starting material has no impact on the diastereoselectivity or yield of the reaction (Scheme 3). Even substrate 1a enriched in the anti-diastereomer gives inversion of stereochemistry of the allylic stereocenter to give the same diastereomeric ratio with nearly identical yields. This highlights the advantage of this reaction in eliminating the need for preparing a single diastereomer of the substrate.

Scheme 3. Diastereoconvergent formation of anti-1,2-amino alcohols.

Next, we examined homoallylic alcohol substrates without substitution at the allylic position to see if our conditions would also give stereoselectivity for these substrates. A screen of common alcohol protecting groups showed that most give good yields and diastereoselectivities, including acetyl (Ac), pivaloyl (Piv), benzyl (Bn), and t-butyldiphenylsilyl (TBDPS) (Table 2). For the best combination of yield and selectivity we chose to continue with pivaloyl protected substrates. Thus, we obtained an optimal unified protocol for amination of substrates both with and without allylic substituents.

Screen of protecting groups.

Yields and diastereomeric ratio (d.r.) determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3-dinitrobenzene as internal standard.

PG = protecting group.

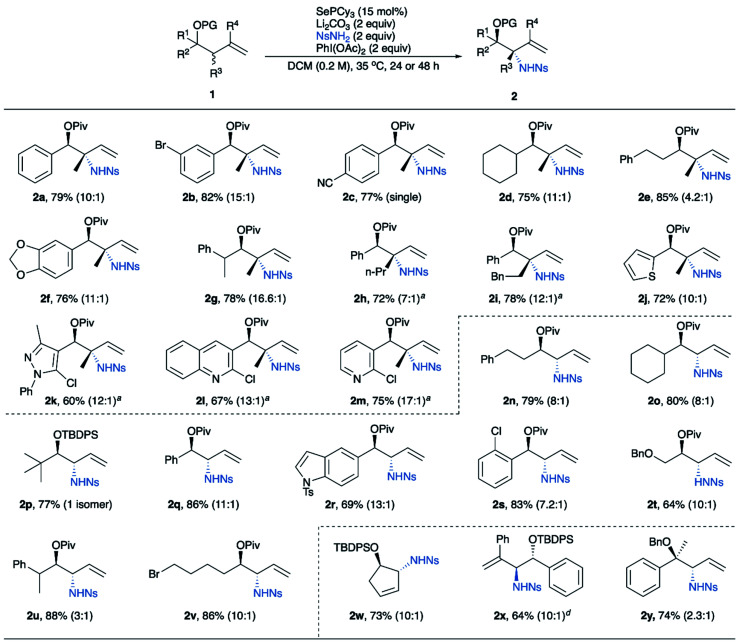

The optimized conditions were applied to a variety of homoallylic alcohol derivatives (Table 3). The reaction displays excellent compatibility with many functional groups including ester, alkyl halides, nitrile, aryl halides, ether, silyl ether, etc. Notably, our reaction tolerates a variety of heterocycles, especially nitrogen-containing heteroaromatics, including thiophene (2j), indole (2r), pyrazole (2k), quinoline (2l) and pyridine (2m). Additional substitution at the allylic position can be tolerated, giving aminated quaternary stereocenters in good yields and diastereoselectivities (2h, 2i). The reaction also tolerates substituents with a wide range of steric demands at the homoallylic position, including primary, secondary, and tertiary alkyl groups, as well as aryl groups. Notably, diastereoselectivities are high even with minimal steric difference between the R group and OPiv group (2n, 2v, 2t), though diastereoselectivity increases as the homoallylic group becomes larger. These trends apply to both substrates without (2n, 2o, 2q and 2p) and with allylic substituents (2e, 2a, and 2d). Furthermore, the reaction is also effective for 1,1-disubstituted alkenes (2x) and cyclic alkenes (2w).

Substrate scope for anti-1,2-amino alcohols.

|

Reaction was performed using SePCy3 (30 mol%) in DCE at 50 °C.

Isolated yields.

Diastereomeric ratio (d.r.) determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

ItBuSe was used as the catalyst.

PG = protecting group.

We then investigated the diastereoselective synthesis of 1,4-amino alcohols starting from internal allylic alcohol derivatives. We started our exploration by subjecting (E)-alkene substrates 3a–d to our previously published allylic amination conditions. Promisingly, the desired product was obtained in high yields, but no diastereoselectivity was observed using acetate as protecting group (Table 4, entry 1). A screen of protecting groups showed that larger groups gave only modest increases in diastereoselectivity (Table 4). We hypothesized that changing the alkene geometry to Z could improve the stereoselectivity by introducing 1,3-allylic strain,12 thereby reducing the conformational flexibility at the allylic position (see Scheme 8A). To our delight, amination of (Z)-alkene 3e gave a marked increase in diastereoselectivity to 4.9 : 1 (Table 4, entry 5). Though starting alkene 3e had the Z configuration, product 4e was found to be exclusively E, which was confirmed by observation of a coupling constant of 15.5 Hz between the alkene protons. The substrate scope for this 1,4-amino alcohol synthesis is given in Table 5. The reaction tolerates both primary and secondary groups on both sides of the alkene.

Optimization for syn-1,4-amino alcohols.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | PGb and R | E or Z | Yielda (%) | d.r.a |

| 1 | 3a | Ac, Me | E | 75 | 1 : 1 |

| 2 | 3b | Bz, Me | E | 75 | 1.5 : 1 |

| 3 | 3c | TBDPS, Me | E | 62 | 1.9 : 1 |

| 4 | 3d | Piv, Me | E | 76 | 1.7 : 1 |

| 5 | 3e | Piv, n-Pr | Z | 78 | 4.9 : 1 |

Yields and diastereomeric ratio (d.r.) determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3-dinitrobenzene as internal standard.

PG = protecting group.

Scheme 8. Stereochemical model for syn-1,4-amino alcohols.

Substrate scope for syn-1,4-amino alcohols.

|

Isolated yields.

Diastereomeric ratio (d.r.) determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Reaction time 70 h.

30 mol% catalyst used.

To probe the stereochemistry of the 1,2-amino alcohol products, 2p and 2f were deprotected and cyclized to 7 and 8, respectively (Scheme 4). Comparison of the coupling constant in 7 to the known literature value10b reveals that the protons are cis, indicating that the reaction affords anti-amino alcohols when there are no allylic substituents. For substituted product 8, an NOE was observed between the proton alpha to oxygen and the allylic methyl group, indicating that the major product bearing allylic substituents is also the anti-amino alcohol.

Scheme 4. Stereochemistry determination.

To explain the diastereoselectivity, a stereochemical model was built based on the proposed mechanism (Scheme 5), namely that the reaction proceeds via an ene reaction between a selenium bis(imide) and the alkene, followed by a [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. The diastereoconvergence is explained by the fact that the allylic stereocenter is destroyed in the initial ene reaction, resulting in preferential formation of the E alkene intermediate from both diastereomers of the starting material (Scheme 5A). The allylic amine stereocenter is then formed in the [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement step. Importantly, the relative stereochemistry of the C–N and C–O bonds is the same for both R2 = H and R2 = alkyl, indicating that the stereochemistry is being controlled only by the stereocenter attached to oxygen. To further test the importance of the inside alkoxy effect in controlling selectivity, ester 9 and homoallylic amine 11 were treated under our optimal reaction conditions, respectively (Scheme 6). Though the reactions proceeded in moderate yields, poor diastereoselectivity was observed, strongly supporting our hypothesis that the inside alkoxy effect9 is the primary factor responsible for the high diastereoselectivity we observe for homoallylic alcohol derivatives.

Scheme 5. Stereochemical model for anti-1,2-amino alcohols.

Scheme 6. Experimental evidence for inside alkoxy effect.

To gain further insights into the stereochemistry-determining [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement, a DFT computational study was performed (Scheme 5C).13 Transition states for the [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement step leading to each diastereomeric product were found. The one leading to the anti product (TS-I) was lower in energy by 2.6 kcal mol−1 than the one leading to the syn product (TS-II), consistent with our experimental results. Careful examination of the two transition states did not reveal any obvious steric clashes. In both, approach of the nitrogen takes place on the opposite face of the bulky alkyl substituent. Interestingly, we observed that TS-I had notably longer C–Se and C–N distances than TS-II (Δ ∼ 0.04 Å), indicating a looser transition state. This was accompanied by a greater degree of charge transfer from the allyl fragment to the selenium bis(imide) fragment (Δq = 0.04). These results are consistent with a stereoelectronic effect on the transition state similar to the known inside alkoxy effect9 described for cycloaddition reactions. NBO calculations show that the π system becomes electron-deficient during the rearrangement and that the orientation of the oxygen substituent affects the degree of charge transfer. In the most stable transition state (TS-I), the protected hydroxyl group is coplanar with the alkene, thereby minimizing the overlap of the electron-withdrawing  orbital with the π system. Simultaneously, this orientation maximizes the overlap of the electron-donating σC–H and σC–C bonds with the π system, enabling greater charge transfer and thereby stabilizing the transition state.

orbital with the π system. Simultaneously, this orientation maximizes the overlap of the electron-donating σC–H and σC–C bonds with the π system, enabling greater charge transfer and thereby stabilizing the transition state.

To isolate this stereoelectronic effect and more closely examine it, transition states for the [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement on a simple homoallyl fluoride substrate were found for three conformations about the C–C bond: anti, inside, and outside (Scheme 7). The inside fluoro transition state was again found to be the lowest in energy. As before, there is a clear correlation between the dihedral angle of the C–F bond and the amount of charge transfer from the substrate to the Se–N fragment, with the greatest charge transfer occurring in the inside fluoro transition state. Similarly, the transition states with more charge transfer were found to be looser, as indicated by the sum of the C–Se and C–N bond lengths, and had substantially more charge transfer to the selenium imide fragment. These calculated transition states confirm the importance of stereoelectronic control in the stereochemistry-determining [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement.

Scheme 7. Computational study for homoallyl fluoride.

The stereoselectivity in the 1,4-amino alcohols was explored through DFT calculations using a similar stereochemical model to that developed for the anti-1,2-amino alcohols.13 Unlike for 1,2-amino alcohols, however, the stereochemistry of this product is determined in the initial ene reaction. Avoidance of 1,3-allylic strain fixes the orientation of the allylic stereocenter as in Scheme 8A. DFT calculations reveal that the most stable transition state has the selenium bis(imide) approach from the same face of the alkene as the acyloxy group (TS-III), rather than adjacent to the alkyl group (TS-IV). Though small, the preference for TS-III over TS-IV of 0.4 kcal mol−1 is consistent with the relative steric size of these two groups and the observed diastereomeric ratio. The requirement for conformational restriction using 1,3-allylic strain explains the improved performance of Z alkenes over E alkenes.

In the subsequent [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement, orientation of the R* group in the equatorial position is favored, leading to the formation of the syn-1,4-amino alcohol bearing an E alkene as the major diastereomer (Scheme 8C). This is consistent with the observation that only E alkenes are formed, regardless of the initial configuration of the starting alkenes.

Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a diastereoconvergent synthesis of anti-1,2-amino alcohols bearing quaternary N-containing stereocenter via intermolecular direct allylic C–H amination catalyzed by phosphine selenides, complementary to existing approaches that give syn-1,2-amino alcohols. Experimental and computational studies reveal that the diastereoselectivity is controlled by a stereoelectronic effect similar to the inside alkoxy effect, in which the protected hydroxyl group avoids withdrawing electron density from the transition state of the [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. The diastereoconvergent ene reaction step eliminates the need to prepare a single diastereomer of homoallylic alcohol derivatives to achieve high diastereoselectivity. We have also developed a synthesis of syn-1,4-amino alcohols via direct C–H amination, constituting a rare example of remote stereochemical induction in the preparation of these compounds.

Data availability

Data for this paper, including characterization data for all new compounds and structures and energies for all DFT computations, are provided in the ESI.†

Author contributions

T. Z. conducted all experiments. J. L. B. performed all DFT calculations. F. E. M. directed the research. T. Z. and F. E. M. wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Washington and the National Science Foundation (CHE-2102267) for funding. Computations were facilitated through the use of advanced computational, storage, and networking infrastructure provided by the Hyak supercomputer system at the University of Washington, funded by the Student Technology Fee.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See https://doi.org/10.1039/d2sc02648a

Notes and references

- For selected reviews on amino alcohols, see: ; (a1) Lee H.-S. Kang S. H. Synlett. 2004:1673–1685. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-829578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; and references therein.; (b) Pu L. Yu H.-B. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:757–824. doi: 10.1021/cr000411y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ager D. J. Prakash I. Schaad D. R. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:835–876. doi: 10.1021/cr9500038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews on C–H functionalization, see: ; (a) Davies H. M. L. Manning J. R. Nature. 2008;451:417–424. doi: 10.1038/nature06485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gutekunst W. R. Baran P. S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1976–1991. doi: 10.1039/C0CS00182A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) McMurray L. O'Hara F. Gaunt M. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1885–1898. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15013H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of 1,2-amino alcohols via direct C–H amination. For intramolecular transformations, see: ; (a) Osberger T. J. White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:11176–11181. doi: 10.1021/ja506036q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fraunhoffer K. J. White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7274–7276. doi: 10.1021/ja071905g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Strambeanu I. I. White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12032–12037. doi: 10.1021/ja405394v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lebel H. Huard K. Lectard S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14198–14199. doi: 10.1021/ja0552850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lebel H. Mamani Laparra L. Khalifa M. Trudel C. Audubert C. Szponarski M. Dicaire Leduc C. Azek E. Ernzerhof M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:4144–4158. doi: 10.1039/C7OB00378A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Espino C. G. Du Bois J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:598–600. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010202)40:3<598::AID-ANIE598>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Grelier G. Rey-Rodriguez R. Darses B. Retailleau P. Dauban P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017;2017:1880–1883. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201700263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Grigg R. D. Rigoli J. W. Pearce S. D. Schomaker J. M. Org. Lett. 2012;14:280–283. doi: 10.1021/ol203055v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Ju M. Huang M. Vine L. E. Dehghany M. Roberts J. M. Schomaker J. M. Nat. Catal. 2019;2:899–908. doi: 10.1038/s41929-019-0339-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (j) Cui Y. He C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:4210–4212. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Milczek E. Boudet N. Blakey S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:6825–6828. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Liang J.-L. Yuan S.-X. Huang J.-S. Yu W.-Y. Che C.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:3465–3468. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3465::AID-ANIE3465>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Barman D. N. Nicholas K. M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011;2011:908–911. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201001160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (n) Liu Y. Guan X. Wong E. L.-M. Liu P. Huang J.-S. Che C.-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:7194–7204. doi: 10.1021/ja3122526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o1) Jung H. Keum H. Kweon J. Chang S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:5811–5818. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c00868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; . For intermolecular transformations, see: ; (p) Dong Y. Chen J. Xu H. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:11096–11099. doi: 10.1039/C8CC05637D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (q) Dong Y. Liu G. J. Org. Chem. 2017;82:3864–3872. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (r) Jin L. Zeng X. Li S. Hong X. Qiu G. Liu P. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:3986–3989. doi: 10.1039/C7CC00808B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (s) Kang T. Kim H. Kim J. G. Chang S. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:12073–12075. doi: 10.1039/C4CC05655H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples of radical-mediated C–H amination for synthesis of 1,2-amino alcohols, see:; (a) Mou X.-Q. Chen X.-Y. Chen G. He G. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:515–518. doi: 10.1039/C7CC08897C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nakafuku K. M. Zhang Z. Wappes E. A. Stateman L. M. Chen A. D. Nagib D. A. Nat. Chem. 2020;12:697–704. doi: 10.1038/s41557-020-0482-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wappes E. A. Nakafuku K. M. Nagib D. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:10204–10207. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Prusinowski A. F. Twumasi R. K. Wappes E. A. Nagib D. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:5429–5438. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c01318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kurandina D. Yadagiri D. Rivas M. Kavun A. Chuentragool P. Hayama K. Gevorgyan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:8104–8109. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b04189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews on diastereoselective C–H amination, see: ; (a) Herrmann P. Bach T. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:2022–2038. doi: 10.1039/C0CS00027B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Collet F. Lescot C. Dauban P. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1926–1936. doi: 10.1039/C0CS00095G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ramirez T. A. Zhao B. Shi Y. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:931–942. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15104E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Darses B. Rodrigues R. Neuville L. Mazurais M. Dauban P. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:493–508. doi: 10.1039/C6CC07925C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateu N. Kidd S. L. Kalash L. Sore H. F. Madin A. Bender A. Spring D. R. Chem.–Eur. J. 2018;24:13681–13687. doi: 10.1002/chem.201803143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and references therein.

- (a) Teh W. P. Obenschain D. C. Black B. M. Michael F. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:16716–16722. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c06997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Maloney T. P. Dohoda A. F. Zhu A. C. Michael F. E. Chem. Sci. 2022;13:2121–2127. doi: 10.1039/D1SC07067C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews on diastereoselective synthesis of homoallylic alcohols, see: ; (a) Xiang M. Pfaffinger D. E. Krische M. J. Chem.–Eur. J. 2021;27:13107–13116. doi: 10.1002/chem.202101890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ketcham J. M. Shin I. Montgomery T. P. Krische M. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:9142–9150. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kennedy J. W. J. Hall D. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2003;42:4732–4739. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yus M. González-Gómez J. C. Foubelo F. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:5595–5698. doi: 10.1021/cr400008h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zanoni G. Pontiroli A. Marchetti A. Vidari G. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007;2007:3599–3611. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200700054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (f) Denmark S. E. Fu J. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2763–2794. doi: 10.1021/cr020050h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Cha J. K. Kim N.-S. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:1761–1795. doi: 10.1021/cr00038a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b) Houk K. N. Moses S. R. Wu Y. D. Rondan N. G. Jager V. Schohe R. Fronczek F. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:3880–3882. doi: 10.1021/ja00325a040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hatakeyama S. Saijo K. Takano S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:865–868. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)61950-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples of diastereoselective synthesis of 1,3-amino alcohols via direct C–H amination, see: ; (a) Paradine S. M. White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2036–2039. doi: 10.1021/ja211600g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rice G. T. White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11707–11711. doi: 10.1021/ja9054959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Paradine S. M. Griffin J. R. Zhao J. Petronico A. L. Miller S. M. White M. C. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:987–994. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ma R. Young J. Promontorio R. Dannheim F. M. Pattillo C. C. White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:9468–9473. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b02690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wehn P. M. Lee J. Du Bois J. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4823–4826. doi: 10.1021/ol035776u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples of 1,4-stereoinduction, see: ; (a) Tomooka K. Keong P.-H. Nakai T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:2789–2792. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(95)00397-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (b1) Kobayakawa T. Narumi T. Tamamura H. Org. Lett. 2015;17:2302–2305. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and references therein.

- Hoffmann R. W. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:1841–1860. doi: 10.1021/cr00098a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Petersson G. A., Nakatsuji H., Li X., Caricato M., Marenich A. V., Bloino J., Janesko B. G., Gom-perts R., Mennucci B., Hratchian H. P., Ortiz J. V., Izmaylov A. F., Sonnenberg J. L., Williams-Young D., Ding F., Lipparini F., Egidi F., Goings J., Peng B., Petrone A., Henderson T., Rana-singhe D., Zakrzewski V. G., Gao J., Rega N., Zheng G., Liang W., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Throssell K., Montgomery Jr J. A., Peralta J. E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M. J., Heyd J. J., Brothers E. N., Kudin K. N., Staroverov V. N., Keith T. A., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A. P., Burant J. C., Iyengar S. S., To-masi J., Cossi M., Millam J. M., Klene M., Adamo C., Cammi R., Ochterski J. W., Martin R. L., Morokuma K., Farkas O., For-esman J. B. and Fox D. J., Gaussian 16, Revision C.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for this paper, including characterization data for all new compounds and structures and energies for all DFT computations, are provided in the ESI.†