Abstract

Adolescent hospitalizations for suicide-related behaviors have increased in recent years, with the highest rates occurring during the academic school year. Schools are a primary environment that adolescents return to following hospitalization, making them an important context for understanding recovery following a suicidal crisis. Although previous research highlights provider perceptions for improving this transition, limited research has focused on adolescent views. This qualitative study presents findings from interviews with 19 adolescents previously hospitalized for a suicide-related crisis. Results highlight the need to strengthen social supports for returning youth. Specifically, findings suggest the importance of emotional supports (e.g., positive school relationships and a safer psychosocial school climate), instrumental supports (e.g., collaborations and communication around re-entry), informational supports (clearer procedures for academics and re-entry processes), and appraisal supports that acknowledge the complexity of adolescent functioning upon return. Findings reinforce the importance of the school psychologist’s role in partnering with returning youth and their families and providing consultation to other school professionals about supporting their recovery.

Keywords: Suicide, School Adjustment, Qualitative Methods, Prevention, Mental Health Services, Community-School Collaboration

Introduction

Adolescent death by suicide and hospitalization for suicide-related behaviors (i.e., suicidal ideation, suicide plans and attempts) have significantly increased over the past two decades (Plemmons et al., 2018). Hospitalization rates appear highest during the school year (Plemmons et al., 2018) with school professionals frequently encountering students returning to school following hospitalization (Simon & Savina, 2010; Clemens et al., 2010). During the immediate period following psychiatric hospitalization, when majority of adolescents return to schools, risk for making a suicide attempt or re-hospitalization for suicide-related behaviors is extremely high (James et al. 2010). Thus, researchers have called for increased attention towards improving adolescent school re-entry experiences following hospitalization for suicide-related crises (Marraccini et al., 2019; Tougas et al., 2019). Therefore, this qualitative study explores adolescent perspectives of returning to school following psychiatric hospitalization for suicide-related crises, centralizing adolescent voices for improving school reintegration practices.

School Reintegration Following Psychiatric Hospitalization

Although the effectiveness of psychiatric hospitalization for stabilization and recovery from suicidal crisis is highly debated (Jobes 2017) it remains standard practice for most youth at risk for making a suicide attempt (Kidd et al., 2014). Inpatient care involves varying treatment modalities that focus on safety, stabilization, and psychopharmacology (Hayes et al., 2019). While often considered a necessity for preventing harm, psychiatric hospitalization can mean an abrupt disruption to adolescents’ everyday lives that requires immediate, on-going treatment following discharge (Prinstein et al., 2008). Unfortunately, treatment engagement following hospitalization is low (Brown & Jager-Hyman, 2014), with inconsistent attendance and premature treatment termination serving as common barriers to quality outpatient care (Spirito et al., 2011). In fact, a substantial portion of youth appear to receive no treatment following psychiatric hospitalization. For example, among recipients of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (n.d.) in 2018, median estimates of children (ages 6–17) hospitalized for a mental illness receiving follow-up care were 41.9% and 66.3% within 7 and 30 days, respectively. Thus, adolescents return to school with varying treatment experiences and levels of engagement, as well as social-emotional needs, and remain at high risk for ongoing suicide-related behaviors.

Studies exploring how best to support adolescents as they reacclimate to school after being discharged from psychiatric hospitals have primarily focused on school and mental health professionals’ perceptions. Key considerations that have emerged from this work suggest that schools should identify and mitigate school-related stressors, provide appropriate supports and interventions, establish re-entry and safety plans, and identify individuals to support returning youth (Blizzard et al., 2016; Clemens et al., 2010; Marraccini et al., 2019; Savina et al., 2014; Tougas et al., 2019; White et al., 2017). School professionals should also address negative peer reactions, discrimination, and bullying directed at returning youth (Savina et al., 2014), especially considering that connectedness to peers may serve as an important protective factor against subsequent suicidal ideation following psychiatric hospitalization (Czyz et al., 2012).

Among studies focused on adolescent experiences, similar themes have emerged. Preyde and colleagues (2017) explored adolescent (n = 161) concerns for returning to school during their hospital stay, identifying concerns related to social situations (peer and adult reactions in school), academics (missing work), mental health interfering with school work, the school environment, adjusting to the school routine, and managing psychiatric symptoms at school. Of the 62 adolescents participating in their follow-up study (Preyde et al., 2018), half described their return to school as difficult, with issues related to academics, social situations, and handling emotions. Adolescents demonstrating clinical improvements during psychiatric stay were significantly more likely to describe neutral or positive school reintegration experiences compared to adolescents identified as having only made minimal clinical improvements (Preyde et al., 2018).

Results from two dissertations exploring perceptions of adolescents (n = 8 in each study; Iverson, 2017; Simone, 2017) identified similar themes to those reported by Preyde and colleagues (2018) (i.e., academic, social, and/or emotional themes). Participants in the latter study were recruited based on participation in a transition program with dedicated resources for students returning to school following a mental health crisis and described positive experiences in the program (Simone, 2017). In a thesis focused on school adjustment of 87 adolescents following hospital discharge, Shelley (2007) found that most students returning to school did not receive special education services (66.7%) and had minimal in-school support service changes (although a slight increase in school-based counseling services was noted). Symptom severity did not significantly predict school adjustment, which reflected in-school behavioral referrals (e.g., suspensions, detention), academic grades, involvement in sports or clubs, and attitudes toward school. These preliminary studies provide an important foundation for understanding the phenomenological experiences of returning adolescents, as well as the types of services provided in schools following hospitalization, underscoring the need for additional research that identifies how school reintegration experiences can be improved.

Theoretical Framework

Ecological systems theory has set the stage for much of the work framing practice considerations for adolescent school reintegration. Savina and colleagues’ (2014) proposed ecologically informed guidelines that underscore the need for enhanced communication between stakeholders and establishing a re-entry plan for returning students. Tougas and colleagues’ (2019) framed their systematic review within a bioecological model identifying the problems and needs of adolescents returning to school. Accordingly, this study is framed within an ecological systems model for positive mental health (Bronfenbrennar, 1979; Zubrick & Kovess-Masfety, 2005), taking a dual-factor approach to suicide prevention (Suldo & Shaffer, 2008). That is, indicators of well-being and positive mental health are attended to alongside indicators of suicidality.

Within an ecological framework, adolescents are viewed in the center of multiple systems proposed to transact with development (Bronfenbrennar, 1979). From proximal to distal, these include: the youth ontosystem, including the youth’s own internal influences; the microsystem, which reflects the immediate environments surrounding youth, such as school and family; the mesosystem, which symbolizes connections between microsystems; the exosystem, encompassing indirect influences from larger systems such as the government or media; the macrosystem, including cultural values, customs, and laws; and the chronosystem, which reflects the dimensions of time. Variability in the youth ontosystem can include problems prior to hospitalization as well as emerging problems from hospitalization (Tougas et al., 2019), but also include a range of learned coping skills that can support adolescents as they reacclimate to the school environment. Individual “drivers” of suicide – that is individual thoughts, feelings, and experiences that lead adolescents to desire death by suicide specific experiences (Tucker et al., 2015) – are another component of the youth ontosystem that should be considered when monitoring recovery. Stressors within the family microsystem such as lack of resources (e.g., time, skills) can impede recovery (Tougas et al., 2019), but family-led advocacy and school involvement, as well as feelings of family connectedness (Whitlock et al., 2014), may support a positive return to school. School microsystem problems related to reintegration may include limited knowledge and training around mental health (Tougas et al., 2019); however, healthy school relationships and welcoming school climates may facilitate a sense of normalcy for returning youth. Family-hospital-school mesosystem communication barriers can prevent access to services or limit monitoring of adolescent risk (Tougas et al., 2019), but school-family-community partnerships and school-based health clinics may promote linkages to care.

Finally, cross-system social supports, which intersect all layers of the adolescent’s ecology, may help returning youth reacclimate to the school setting and also reinforce a sense of school connectedness to protect against suicide-related thoughts and behaviors (Marraccini & Brier, 2017). Connectedness has been proposed to protect against suicide by way of subjective feelings and intrapersonal experiences (e.g., feeling a sense of belonging), in the context of interconnected social systems that allow for direct avenues to help-seeking (e.g., disclosing suicidal ideation to an adult in school), and shared norms and expectations that promote help-seeking behaviors (Whitlock et al., 2014). Schools may play an important role in fostering connectedness by providing social support across four broad categories: emotional, instrumental, informational, and appraisal (Malecki & Demaray, 2003; Suldo et al., 2009; Tardy, 1985). That is, schools can provide: emotional support by conveying expressions of love, feelings of trust, and messages of empathy; instrumental supports through access to in-school mental health services and referrals for community care; informational support by offering guidance, advice, and information; and appraisal support with evaluative feedback that reinforces positive behaviors and provides scaffolding and direction towards improvement. A deeper understanding of adolescent school re-entry experiences and perceptions of social supports that is framed by a systems ecological model for positive mental health holds practical implications for school professionals supporting these youth. Insights can help guide improvements for existing practices and also inform ways schools can mitigate stressors related to suicide-related behaviors.

The Current Study

The extant research highlights provider perceptions for improving school re-entry and focuses on the phenomenological experiences of adolescents returning to schools following psychiatric hospitalization. Qualitative studies focused on adolescent experiences have relied on small sample sizes that may not fully capture the range of symptom severity and ethnic and racial variability representing hospitalized adolescents, with limited insight into adolescent perceptions for improving reintegration. No studies have explicitly focused on the perceptions of adolescents hospitalized for suicide-related risk, a particularly important group considering they represent nearly half of hospitalized youth (Tossone et al., 2014) and return to schools with complex academic, social-emotional, and cognitive needs (Cleary et al., 2019; White et al., 2017). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to cast light on the lived experiences of adolescents to help inform practices that support adolescent school re-entry following hospitalization for a suicide-related crisis. By focusing on adolescent perspectives, this study aims to: (1) describe school re-entry experiences following hospitalization; and (2) explore perceived ways for improving school re-entry.

Methods

This qualitative study was part of a larger mixed-methods study that is developing guidelines for school reintegration following hospitalization for a suicide-related crisis. The present study is focused on the qualitative data collected from adolescents previously hospitalized for suicide-related crises; however, both quantitative and qualitative data for the larger study is being collected from a range of stakeholders that includes adolescents, parents, school professionals, and hospital professionals.

Participants

Participants were identified from medical records of adolescent patients admitted to a large psychiatric hospital located in the southeast United States. Eligibility criteria included (a) hospitalization for suicide-related behaviors; (b) ages 13–18; (c) return to school following hospital discharge; and (d) ability to speak, read, and understand English sufficiently to complete study procedures. The final sample included 19 adolescents, ages 13–18 (mean age = 15.7, SD = 1.3 years). Participants identified their sex as female (n = 17; 89.5%) or male (n = 2; 11.8%); 84.2% (n = 16) identified as cisgender and the remaining identified in a way other than boy, man, girl, or woman (n = 2; 10.5%) or indicated they did not know if they were transgender (n = 1; 5.3%). Participants were White (n = 11; 57.9%), Asian and White (n = 4; 21.0%), Black or African American (n = 2; 10.5%), or other (n = 2; 10.5%). Four adolescents (21.0%) were Hispanic/Latinx and the remaining 13 (79%) were non-Hispanic/Latinx. Adolescents attended 18 different schools across 9 school districts.

Procedures

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Participants completed consent and assent prior to all study procedures, including parental permission and adolescent assent for adolescents ages 13–17 and consent for adolescents aged 18 years. Following consent and assent, adolescent participants completed interviews and a brief set of self-report surveys that included a demographic questionnaire developed by the researchers (see Supplementary Materials). Although not the focus of the current study, participants also completed a self-report measure of school climate (the Authoritative School Climate Survey; Konold & Cornell, 2015).

A semi-structured qualitative interview guide addressed four areas of adolescent experiences: (a) school experiences prior to hospitalization; (b) school experiences and considerations during hospitalization; (c) school re-entry experiences and processes; and (d) information sharing between hospitals and schools. For the current study, findings are presented as they relate to (c) school re-entry experiences and processes, which addressed topics related to experiences (e.g., the best or worst part of returning, school members’ perceptions of the student’s return, helpful information during school re-entry); processes (e.g., re-entry planning, key individuals involved, school supports); and considerations for students, families and professionals. A trained masters level interviewer conducted one-on-one interviews with adolescent participants that ranged in length of time from approximately 40 to 90 minutes. The interviewer completed debrief summaries following each interview and inter-rater reliability was assessed based on agreement during data analysis.

The interviewer also conducted the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITB; Nock et al., 2007) with adolescent participants to demonstrate the range in frequency of suicide-related thoughts and behaviors in the study sample. The SITB is a structured interview that has well established psychometric properties for assessing presence, frequency, and severity of suicide-related thoughts and behaviors (Nock et al., 2007). For the current study, the presence of suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts were collected retrospectively for the month prior to hospitalization, the month following return to school, and the month prior to the interview. Timeline follow-back methods were integrated into the SITB interview and participants indicated frequency of suicidal ideation (number of days) or suicide attempts (number of attempts) by marking them on a calendar.

Eighteen interviews were conducted in person, but the final interview occurred during social distancing to reduce the spread of the coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19) and was conducted virtually. As such, we did not conduct the SITB with the final participant. Surveys and interviews capturing quantitative data were completed using a combination of paper and pencil and electronic surveys via REDCap, an electronic data capture system (Harris et al., 2009). Adolescent participants were compensated $30 for participation.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics from quantitative data were calculated in SPSS v.20 (IBM, 2016). Qualitative interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by a professional transcription service. Transcribed interviews were redacted of identifying information and reviewed for accuracy then entered into NVivo 12 Pro qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2018). NVivo is a qualitative data analysis software program that helps organize and manage data into analytic themes. Applied thematic analysis, a systematic and inductive approach that draws from multiple theoretical and methodological perspectives such as basic inductive thematic analysis, grounded theory, and phenomenology, was conducted to analyze text in a transparent, efficient, and ethical manner (Guest et al., 2012). To ensure scientific rigor of methodology and enhance quality of qualitative data analysis, the coding structure was developed based on the interview agenda and iteratively developed based on emerging themes. The first and second author read transcripts and identified emergent themes separately, meeting weekly to come to agreement about the coding structure. Codes were refined across interviews and the final coding structure was entered into NVivo for analysis. To ensure trustworthiness, 10 transcripts were double coded, with researchers meeting to come to consensus. Following assessment of adequate inter-rater reliability (percent agreement above .80), the remaining nine transcripts were coded by the first author of which two were double coded by the second author to prevent drift and ensure consistency. Final codes related to the primary research aims were reviewed and summarized to identify themes related to school re-entry experiences. Illustrative quotes were coded within the final coding structure and selected to represent common themes.

Results

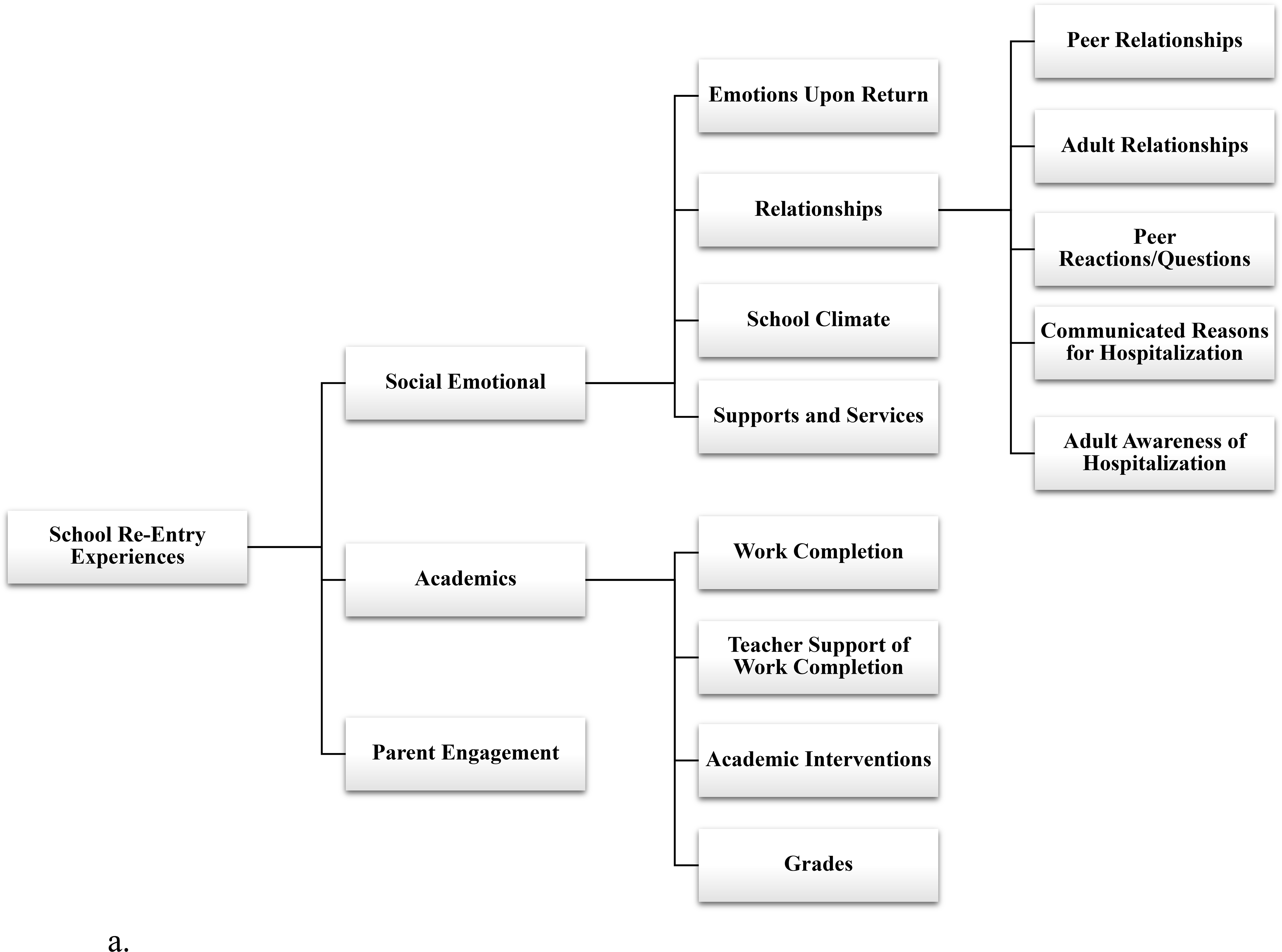

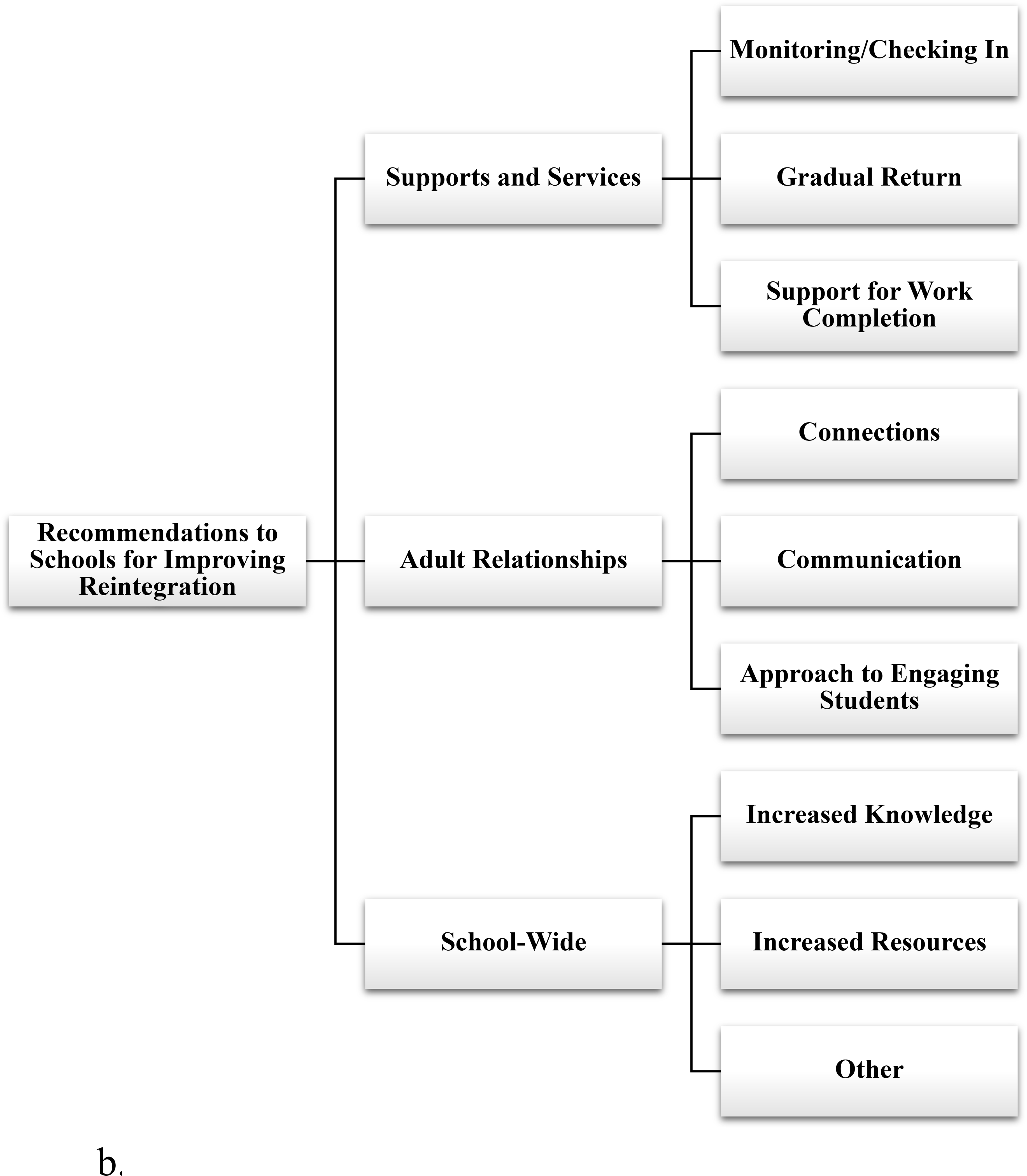

Following description of sample characteristics, qualitative themes are presented in two sections. Themes related to school re-entry experiences are presented first, followed by themes related to recommendations for schools related to improving adolescent re-entry (see Figures 1a and 1b for an overview).

Figure 1a.

Adolescent Perceptions of School Re-Entry Experiences

Figure 1b.

Adolescent Recommendations to Schools for Improving Reintegration

Sample Characteristics

Adolescents were interviewed between 1–6 months following hospital discharge (M = 4.9 months; SD = 1.4 months). Length of hospitalization ranged from 7–22 days (M = 13.2 days; SD = 4.7 days). Presence and frequency of suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts are shown in Table 1. Participant reports of past month suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts declined from month prior to hospitalization (100%, 64.7%, 58.8%, respectively), to the month adolescents returned to school (88.2%, 41.2%, 11.8%), to the month prior to the interview (55.5%, 11.1%, 0%). Frequency of ideation and attempts showed similar reductions over time.

Table 1.

Presence and Frequency of Suicide-Related Behaviors.

| Month Prior to Hospitalization | Month Following Return to School | Past Month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|

|

||||||

| Suicidal ideation | 17 | 100 | 15 | 88.2 | 10 | 55.5 |

| Suicide plan | 11 | 64.7 | 7 | 41.2 | 2 | 11.1 |

| Suicide attempt | 10 | 58.8 | 2 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

|

|

||||||

| Number of days ideation | 19.35 | 9.06 | 12.47 | 10.08 | 5.94 | 8.35 |

| Number of attempts | 1.87 | 3.36 | 0.125 | 0.34 | 0 | 0 |

School Re-Entry Experiences

As shown in Figure 1a, school re-entry experiences fell into categories related to social-emotional experiences, academic experiences, and parent engagement.

Social-Emotional Experiences of Return

Within social emotional experiences, adolescents described: (a) how it felt when they returned to school; (b) their interactions with school members (relationships with peers, relationships with adults, their peers’ reactions to their hospitalization, their communicated reason for absence, and the level of awareness adults in the school had of the student’s hospitalization); (c) school climate upon return; and (d) the supports and services they received.

Experienced Emotions During Re-Entry.

Many adolescents reported their initial experiences back at school as particularly difficult (n = 8), although a handful indicated it was actually positive (n = 4), and some described it as typical or only difficult for a short period of time (n = 6). Of those reporting difficult experiences (n = 8), most tended to describe them as overwhelming or exhausting (n = 5). A 16-year-old girl explained how school stresses interacted with pressure from her family:

On top of everything else going on and coming back, it was sensory overload. It was really hard. My parents really didn’t want me leaving early, and I understand that they wanted me to get back into school, get back into the rhythm of things, but what I had been through, I was definitely struggling staying there the whole day.

Other difficult experiences reported by students (n = 4) related to problematic relationships (e.g., encountering their perpetrator from a previous sexual assault), emergence of psychiatric symptoms in school settings, and having a hard time accessing supports. One boy described how returning to school was particularly hard given a history of trauma and having to overhear conversations that reminded him of it in school:

When I returned to school, it was hard for me because of all the people. It made me nervous what they were talking about…I felt like running away. I felt like I needed to be in one little area and nobody else there.

Regarding positive experiences, two students shared that it was nice or fun to see people such as friends and teachers again, and others (n = 2) simply indicated that their first day back was fine or good overall. Among those reporting their return to school as feeling typical or difficult for a short period of time (n = 6), a 15-year-old student (unsure of their gender identity), described their initial nervousness that was abated by feeling well supported:

Like the first day, I was pretty nervous. I was pretty like, “Ah,” but I had my friends there and they were really supportive, and they were really nice, and they were like, “Hey, if you don’t wanna be here, just tell me, and we’ll go somewhere else.

Two students also described how feeling like things were normal again contributed to their comfort overall. One of these students, an 18-year-old girl, described the good parts of her return this way: “bringing the normalcy quick and not making it uncomfortable for me. Not making it too different than how it was before. The bad things are that it was not different from before. [Laughs] I’m contradicting myself.”

Interactions with School Members.

When describing their interactions with school members, adolescents reflected on their relationships with peers and adults and the ways in which they believed school members viewed their absence (peer perceptions of their absences, communicated reasons for absences, and adult awareness of hospitalization).

Relationships with Peers and Adults.

Regarding peer experiences, two themes emerged: (1) positive connections with friends and peers; and (2) feelings of isolation. Multiple adolescents (n = 7) described having positive experiences with their friends. These included feeling like their peers were happy to see them, excitement around reconnecting with friends, feeling supported by friends, and even making new friends.

Adolescents also reported feeling isolated or purposefully isolating themselves from friends and peers (n = 7). Descriptions included lost friendships, fear of having missed out in social experiences, eating lunch alone, and purposefully seeking out adults instead of peer social interactions. A 15-year-old girl described her conflicting feelings about reconnecting with friends, feeling mad at them for not understanding her experience:

I came back and I was mad at them…I was a very different person when I first came back cuz it’s weird. You’re with completely different people for so long. Well, not so long but it felt like forever. It felt so long coming back. They were like, “Oh, you were just gone for a week and a half. Welcome back.” It’s like, “Oh my God. It felt like three months.”

When describing adult relationships upon return, a similar pattern to those related to peers emerged, with many reporting positive adult interactions (n = 7) and a few reporting negative experiences (n = 1) or minimal interactions with adults (n = 3). Of those reporting positive interactions, a number (n = 4) actually reflected on how their positive relationships with school adults prior to their hospitalization played a role in their interactions during their return. A 16-year-old girl described it this way:

…okay, I was really lucky because two of my teachers were really nice, and they were really involved, and – they definitely didn’t want me going behind because—me being—I feel like definitely if I wasn’t a concentrated, hard-working student, they wouldn’t have given me as much help.

Additionally, multiple adolescents (n = 5) described adults going out of their way to connect with them after their hospitalization. A 14-year-old girl shared how her teachers intentionally reached out:

I think they had a thought that it would be a much more safer and better choice that they got into a relationship with me. You know, getting to me, you know, just, like, showing me that they were safe, they were kind. You know, just building that trust between them.

Although far fewer students reported having negative interactions, one 15-year-old girl shared an experience of feeling judged by their teacher: “I remember one class, I really hated it because I just felt really judged, for some reason, not just by the students but by the teacher as well...”

School Members’ Views of Absence.

Adolescents described their peers’ reactions and questions regarding their hospitalization. Specifically, they described rumors about themselves being spread (n = 3) and questions or comments directed to them about their hospitalization or absences (n = 5). A few shared that they were not concerned about what their peers thought (n = 3) and others reported being treated the same by their peers as usual, it not feeling like a big deal, or not feeling like anyone really noticed their absence (n = 3).

This 17-year-old girl described her reaction to having peers ask questions and spread rumors: “…it’s hard for students and it can make you feel very vulnerable and alienated by everybody else asking questions and having your business spread around so people can help you.” Another 15-year-old girl described it this way: “And they’re, like, ‘Tell me exactly every gory detail.’ And people—I don’t know. People aren’t the nicest, but it was okay.”

Rumors included stories of pregnancy, drugs, and death, with one rumor centering around a teacher disclosing confidential information to the entire class about this 15-year-old student (unsure if transgender):

And then there was this one rumor that my friend had told me that one of my teachers had said, out loud—like they were doing roll, and they said my name, and they were like, “Oh, I forgot. She’s in a crazy hospital.” That found out not to be true. But, someone had told me that, and that really made me upset, and then it made me skip that class even more.

Regarding communicated reasons for absences, many adolescents shared different information with trusted or close friends compared to peers or acquaintances, with the former generally including more details and the latter less (n = 6). When describing what they communicated to close friends specifically, six adolescents described sharing the truth, but two explained they shared as little as possible because they didn’t want to be pitied or because they didn’t think they were allowed. Regarding peers more generally, most adolescents told their peers that they were sick (n = 9), a few (n = 3) shared that they were in the hospital or got mental health help, and one simply answered, “I don’t know.” Two adolescents described a two-phased approach with a general answer for an initial question, such as “I was out,” and if further questioned a pithy statement to end the conversation, such as “mind your own business.”

Adolescents also described adult school members’ awareness of their hospitalization. Six indicated that some adults knew where they were returning from (primarily support professionals such as counselors or administrators) and others did not (primarily teachers). Regarding teachers specifically, two students reported that they provided teachers with limited information about their whereabouts (e.g., they were sick) and another two described sharing information directly with teachers. Multiple students (n = 5) were unsure of whether or not adults knew about their hospitalization, of whom two reported that adults likely knew indirectly (i.e., they guessed it based on other experiences with the student).

School Climate.

When reflecting on the climate or environment of their school during their return, a handful of students described it feeling the same as before (n = 4) and others (n = 5) described it as feeling different than prior to their hospitalization. These changes were predominantly negative (n = 3), for example including increased or continued bullying experiences, and feelings of not belonging; and also involved changes in friendships (n = 1) or perceptions of improved climate (n = 1).

Supports and Services.

Finally, students were asked about the social-emotional supports and services they received when returning to school. A total of nine students indicated having no re-entry meeting or process during their return to school; however, 13 students described receiving some type of service intended to support their return to school, irrespective of being initiated by the school or others. Students described having a re-entry meeting, establishing a point person for their return, making a plan in the case of suicidal urges, developing a gradual plan for their return, and changing or initiating special education services or accommodations with an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) or a 504 plan (see Supplementary Table S1). While most simply indicated that they received these services, some students spoke about their feelings about these experiences. For example, two students described feeling uncomfortable being at their re-entry meeting; one explained that despite having a point-person, they were reticent to seek them out; and three described barriers to accessing their counselors. Students also described some of the strategies they employed to regulate their mood during school, with a mix of self-initiated strategies (e.g., activity books such as coloring books or word searches, talking to friends, having fidgets, using social media, checking in with a counselor or other school adult) and school initiated ones (e.g., counseling, having a safe place in school, having the option to leave class early or arrive late, and therapeutic plants). Regarding how decisions about supports and services in school were made during student return, students described a range of decision makers: including their parents (n = 5), themselves (n = 3), their school or the school professionals in school (n = 3), and outside providers (n = 2).

Academics

Description of academic expectations, experiences and interactions upon return included (a) work completion (the amount of work required, exemptions from making up work, timelines around work completion expectations, the need to self-initiate); (b) ways in which teachers were and were not helpful with supporting work completion; (c) academic interventions and course or schedule changes; and (d) feelings around grades.

Work Completion.

Adolescents described having a lot of missing work to complete or challenges with completing missed work (n = 6), and many (n = 8) reported that they were exempt from having to complete some or all missing work and exams. Five students also mentioned whether or not they had defined timelines for completing missing work, with a few describing how not being provided timelines made it more difficult to complete work (n = 2), and one suggesting it was fine. Three adolescents also shared how it was important for them to self-initiate and monitor their make-up work to be successful. For example, a 15-year-old girl explained:

I make a big deal to talk to my teachers— and say, “Hey, this is a thing that’s going on I need your help with.” Or, like, “Hey, I missed that one. I need a refresher.”… Most kids just fall behind and don’t get back.

Only four students reported concerns about missing out on lessons or instruction, with three identifying math as particularly challenging to learn following their absences.

Teacher Support.

Adolescents described a variety of ways in which teachers were particularly helpful in supporting their work completion, including clearly communicating, being available to support the student in completing make-up work, helping create workplans with deadlines, and providing accommodations (see Supplementary Table S2). Students also described approaches they considered unhelpful, with most sharing concerns about minimal or no communication about missing work or support in learning missed material (n = 4). A 17-year-old boy described it simply, “They didn’t really tell me what I needed to do; I had to figure it out.” A 15-year-old girl also explained:

…there was not much communication or help. They always tell you in high school, you’re on your own and stuff but you can at least try to help me. Come on. I’ve been gone for a week and a half. Can’t you just please make this easier on me? Especially when coming back from a place like that and you have to readjust yourself to being back into normal life and stuff, it’s like you’re just throwing this all at me and expecting me to be able to focus on it. Yeah, I wasn’t ready for that.

Academic Interventions.

A total of 11 students described having their schedules or classes changed upon their return, three of whom specifically identified their school counselor as supporting the process. Most (n = 7) described having more difficult or rigorous courses (e.g., Advanced Placement [AP]) dropped from their schedules). Although few expressed emotional reactions to these changes, one 15-year-old student (unsure if transgender) described their disappointment in learning how their school dropped them from AP and honors courses:

That’s something that also set me off – was that they changed my schedule from me having an AP class and a foreign language class and all honors and everything to all regular classes. I was really upset about that. So, before, like I had really good classes, but then I got hospitalized, and it messed everything up. And so, like, I couldn’t recover from doing that, so they just put me in regular classes. … Because it was such fast-paced, they thought I couldn’t keep up. I just didn’t like it either ’cause it was a completely different schedule than what I was doing before, and it scared the absolute shit outta me. Then, I ended up loving it because I had friends in there, and it was pretty nice.

Another girl, aged 16 years, explained her frustration at having minimal guidance related to her schedule:

And it was more of like, it laid on my shoulders to figure out if I was gonna drop out of the [advanced] program or if I was gonna return to school right away or take a couple months off and do summer school. Like, it was up to me.

Regarding academic supports, six students described signing up for in-school or out-of-school work completion or study skills courses (e.g., credit recovery programs, alternative learning centers, study skills classes). One described it as helpful and another described it as unhelpful.

Grades.

Only a few students described their perceptions about the impact of their mental health crises on their grades, with two specifically identifying a drop in their grades because of absences (with the former describing failing and the latter describing a shift from As to Bs). This latter student and two others explained how important their grades were to them, with a 16-year-old girl describing the push and pull they felt regarding self-care and grades the following way:

It was kind of like people—like my therapist and that type of thing, they were like, oh, you should put yourself first. But it was not like a—you can’t have both. It’s like—you can drop out of school. Like, you can put yourself first and just—you can choose to put yourself first over schoolwork. But then it’d be like I’d have to drop out the [advanced] program. I could potentially fail all my classes or get— incompletes for them.

On the other hand, another student (unsure if transgender), aged 15, described how grades felt less important compared to friendships upon their return, especially considering they had to complete school courses outside of the typical school day:

…I was worried about my friends and if people still cared about me ’cause that was what was most important to me, like if people still cared about me or still wanted me around. I just didn’t really—like grades were the least important thing to me, which is stupid ’cause I need to focus on that. I don’t know.

Parent Engagement

A theme related to parent engagement in re-entry experiences emerged across experiences. Ten adolescents spoke about the ways in which their parents advocated for them or supported their return to school. Multiple (n = 5) described their parents as the primary decision makers in changing their schedules, with a few (n = 2) upset by their decisions. For example, a 15-year-old explained feeling upset about their parents “quitting the class” for them and wasting all the work they put in to the class previously. Three adolescents shared how their parents informed the school about their hospitalization, two reported that their parents decided they would return to school gradually, and two explained that their parents reached out to the school directly to advocate for support around timelines and organizing missed academics for the students. Another student described how their parent contacted a teacher about ongoing bullying.

Recommendations to Schools for Improving Reintegration

As shown in Figure 1b, student recommendations for improving their return to school focused on recommendations for (1) improving supports and services, (2) strengthening adult relationships, and (3) addressing school-wide issues.

Supports and Services

Recommendations to schools around improved services and supports fell into three general categories: (a) providing monitoring or checking in with students during the initial period of their return, (b) providing a gradual return or easing of entry into making up work, and (c) providing support around work completion and academic make-up.

Nine students suggested that adults in school should regularly check in with them upon their return. Ideas ranged from daily meetings with counselors to simply sending a brief email or note to the student. A few even recommended specific strategies to engage returning adolescents, for example setting up a regularly occurring time to meet and reaching out to youth to set up counseling instead of relying on self-referrals. A 15-year-old student identifying in another way than girl or boy suggested:

Just be on the lookout for them, ‘cause they’re probably still a little bit hazardous. No one’s going to completely get better the first time they go to the hospital. Asking them maybe on a daily basis, “How was your day. How do you feel?” Just low-key questions that can kinda tell you a lot about them. Maybe let them know that you’re a support if you want to be a support. Some people don’t want to. Explicitly let them know. Just be like, “Hey, I’m here for you if you ever need anything, if you need to talk, or a shoulder to cry on.” I feel like that’s really important to a lot of people, ’cause a lot of people feel really alone, ’cause they don’t get that.

Although a few specifically suggested having trained counselors available for services, others simply spoke to the importance of having at least one adult who knew about their experience and could be a support at school. A 15-year-old girl described it this way:

I think it would’ve just made me feel like maybe someone was actually there to—I wasn’t less lonely there or I didn’t feel I was—you know. When you’re there, it just feels like nobody really knows what you’re going there. At home, at least, my parents knew that I was struggling. They knew that sometimes I would need time alone. When it came to school, nobody knew that so it would be nice if had somebody there who seemed like they understood my situation and stuff like that.

Although not calling for monitoring directly, when asked about how schools could improve his school re-entry experience, this 17-year-old boy student’s answer reinforced some of the other student’s recommendations: “I don’t know ‘cause I didn’t really reach out for support. It’s tough to give someone support if they don’t reach out for it if you don’t know they need it.” Two students also specifically indicated the importance of peer groups, with one suggesting a peer support group upon return.

The importance of returning to school gradually was described by four students. These adolescents recommended having returning students attend school later in the day or completing work when other students are not around, gradually beginning school work and assignments, and just generally taking the return to school slowly.

Finally, suggestions for improving expectations for work completion were offered by six students. A few (n = 3) described having time devoted to making up work (e.g., study skills classes) as a particularly helpful strategy. Others (n = 4) suggested that schools provide clearer guidance around deadlines and amount of work completion expectations and grading policies in the context of longer absences due to hospitalization, with one student explicitly suggesting that schools differentiate requirements around make-up work in classes that provide important academic content (e.g., math) compared to nonessential courses such as “athletic or standard courses.” Finally, two students voiced the importance of providing flexibility in grading and academic deadlines to allow returning students time for recovery.

Adult Relationships

A handful of students (n = 4) spoke about the importance of connecting with adults upon return and the ways in which adults should work to get to know returning adolescents and not overly focus on academics. They described wanting their teachers and counselors to get to know them, ask them how they are, and engage above and beyond academics. A 15-year-old girl explained: “I wish they – they acted like they cared more – a little bit more about me as a person.” Additionally, a 17-year-old girl shared the following:

But not just focusing on everything that you missed ’cause that’s gonna stress you out—bein’ like, “We love you,” or “I love you and I care about you. I miss you and you’re a great addition to my class. I’m super happy to have you back. If you need anything, just let me know. You can always talk to me if you need some chill time.”

Some students also addressed the ways in which they wanted adults to communicate with them around their hospitalization. While two students felt it was important to address the issue straight on, with honesty, another valued the normal feelings of being treated as a regular student and appreciated adults approaching the subject more discretely, for example by sharing a story about working with a similar student.

Finally, six students offered advice about how to approach students returning from the hospital, with most (n = 4) emphasizing the importance of treating returning adolescents with care – giving them a warm welcome and appreciating that their experiences were filled with challenges. One student, a 17-year-old girl, suggested adults in schools learn and apply therapeutic terminology after describing how she felt like she was in trouble when she was called out of class for a risk assessment:

They need to have different words, I guess. She was very accusatory. I felt embarrassed. I felt like I had done something very wrong for just saying that. Yeah. More like, “I noticed that you were struggling a little bit.”…“Use I. Don’t use you.” I think that could be really helpful.

Finally, checking assumptions about what adults know about the adolescent was also suggested by three students, with one emphasizing the possibility that the returning student has changed.

School-wide Issues

Regarding school-wide issues, six students identified the importance of awareness and training around mental health issues, including understanding challenges faced by students struggling with suicidal urges and the need to reduce stigma around mental health problems. Some emphasized the importance of understanding that returning students may continue to struggle with mental health difficulties, with one 17-year-old girl explaining how the standard protocols for risk assessments felt following hospitalization:

It’s not gonna be an easy transition. I went into my counselors, like, “I think I’m still suicidal,” a couple days into school. We had to call my parents. My parents had to come to school, and we had to talk this through. I had to leave, ’cause if you say that, you’re not allowed to be at school. They kick you out. They just don’t realize. They just think it’s like, “We’re going forward now.”

A few mentioned needing more resources to support returning youth, including more counselors and more time and energy spend on mental health training (n = 2). This 14-year-old girl reported why she thinks it is important “I just believe every single school across all 50 freaking states should be educated in mental health. That’s just me.” Students also described the importance of addressing bullying (n = 2) and approaching student interactions with more cultural awareness (n = 1). Two adolescents specifically offered suggestions on improving their social experience upon school re-entry, suggesting that teachers can help other adolescents learn how to appropriately welcome students back (n = 1) and that a general focus on improving the school’s understanding of mental health could improve the social experience (n = 1).

Discussion

This study aimed to expand understanding of school reintegration and inform improvements by elevating student voices and presenting the lived experiences of 19 adolescents previously hospitalized for suicide-related behaviors. By employing a qualitative approach to investigate the lived experiences of adolescents experiencing suicide-related thoughts and behaviors, findings from this study fill a significant gap in the literature that, until now, has focused primarily on provider perceptions of reintegration and overlooked perspectives from clinical samples of adolescents at high-risk for suicide. Findings set the stage for future research that can develop and evaluate school re-entry processes and procedures aimed at improving adolescent school experiences following suicidal crises to bolster clinical interventions supporting adolescent recovery.

We framed this study within an ecological systems model for positive mental health, positioning social support as a critical cross-system influence for youth returning to school following psychiatric hospitalization. Research conducted with clinical samples of adolescents has identified school connectedness and social connectedness as key protective factors against suicide attempts (King et al., 2019; Whitlock et al., 2014) and a wealth of research conducted within school and community samples has also supported the significance of teacher, classmate, and parent social support for promoting child and adolescent wellbeing (Malecki & Demaray, 2002). Although the frequency of specific types of social supports (i.e., emotional, instrumental, informational, and appraisal) may vary according to source (e.g., parents, teachers, peers), all four types of social support have been linked to improved social-emotional outcomes (Malecki & Demaray, 2003; Tennant et al., 2015). Accordingly, findings from the present study illuminate specific areas of strength and need within each of the four domains of social support. Specifically, these areas include: (1) emotional supports for strengthening school relationships and building positive psychosocial climates in school; (2) instrumental supports that facilitate collaborations around information sharing and re-entry processes; (3) informational supports that establish clear procedures for student re-entry; and (4) appraisal supports that recognize the complexity of adolescent functioning. In the following sections, we elaborate on each of these in more detail and then summarize how these findings may inform future studies for improving school reintegration following hospitalization for a suicide-related crisis.

Emotional Supports

Emotional supports from teachers have been identified as an important facilitator of overall student wellbeing (Malecki & Demaray, 2002; Suldo et al., 2009; Tennant et al., 2015) with findings from the current study signifying the importance of strengthening both adult and peer relationships and fostering a positive school psychosocial climate to support returning adolescents. Adolescents primarily focused on the positive interactions they had with school adults, but they also expressed a desire for adults to connect with them and engage with them interpersonally. Some stressed the importance of small actions by teachers and adults, reinforcing the importance of school professionals’ connection with them. The stories they shared, of appreciating teacher relationships and wanting more connections at large, bring to life some of the existing research that points to aspects of the school microsystem – school connectedness and teacher relationships – as a protective factor against suicide (King et al., 2019; Marraccini & Brier, 2017). Although here they were speaking to its importance for successful return to school following hospitalization, collectively these findings signify the need to strengthen school relationships with students. This phenomenon was previously stressed by Tougas et al. (2019) as an important informal support within the youth ontosystem.

Adolescents also described peers and friends as important supports upon their return. An important difference between perceptions of adult and peer reactions, however, involves the general reaction of the student body. Many described similar concerns reported in previous studies (Preyde et al., 2017; 2018), including having to face direct questions about their hospitalization and rumors related to their absences. Therefore, it is important that schools prioritize a culture of acceptance and care for individuals suffering from mental health problems. Considering concerns for confidentiality and the tendency for some families to keep knowledge of hospitalization from schools all together, promoting acceptance and sensitivity to mental health needs requires an on-going, preventative approach built into school culture.

Despite very few students describing changes in their school climate, many called for increased training around mental health issues, including understanding the significance of psychiatric hospitalization, as well as a focus on reducing mental illness stigma. Indeed, there has been a growing awareness of the importance of addressing mental health in schools and improving the psychosocial climate of school (Aldridge et al., 2018; Atkins et al., 2017) that reinforces the calls made by adolescents here. Previous research suggests schools should focus on improving the environment for returning youth by identifying and addressing peer reactions and improving mental health literacy in the school microsystem (Marraccini et al., 2019; Tougas et al., 2019). Adolescents voiced concerns about both adult and peer reactions. Thus, preparations should include a focus on reducing stigma related to mental health concerns across adults and students, in school and in the community at large (e.g., in the macrosystem). School psychologists can support this process by attending to some of the core components of school climate – that is by addressing many of the other considerations called for by the adolescents in the current study, such as fostering school connectedness, improving school relationships, increasing a sense of safety, and creating a healthy academic environment (Aldridge et al., 2018).

Instrumental Supports

Instrumental supports for supporting adolescents’ return to school following a suicidal crisis center around improved communication with the returning adolescent and their family, with hospital professionals involved in the adolescent’s psychiatric care, and with other school professionals involved in the adolescent’s education and emotional wellness. For example, school professionals can provide support to adolescents in identifying appropriate friends and adults to share information with that may benefit returning youth. Considering that many adolescents reported not being sure about the specific adults aware of their hospitalization, it is important that the specific school professionals receiving information, even after discussions with parents and receiving permission to share such details, are made explicit to adolescents. Meeting with adolescents in smaller settings, in addition to formal re-entry meetings or IEP meetings, is also an important addition to school re-entry processes given the anxiety and discomfort some adolescents expressed about being involved in meetings with parents and school adults.

It is also important to proactively support youth who may not have actively engaged parents or caregivers. Some of the school supports described by participants in the current study appear to have been initiated because of parents’ voiced concerns. School psychologists should consider culturally sensitive ways for engaging families, given family involvement is strongly connected to cultural and economic factors (e.g., Watson & Bagotch, 2015). Parents may feel unequipped at supporting their adolescents’ recovery, with limited time, knowledge, and resources (Tougas et al., 2019). A deeper understanding of parent and caregiver experiences, addressing perceived barriers and facilitators to a smooth return, could inform mechanisms for increasing access to all families.

Finally, considering the variability in students’ preferences for adult communication regarding their absences (e.g., direct versus indirect approaches), and previous work indicating school faculty and staff may feel unsure of how best to communicate with returning students (Tougas et al., 2019), school psychologists can partner with teachers and other support professionals to determine the best approach for engaging with returning youth.

Informational Supports

A common theme voiced by adolescents relates to the importance of informational supports. Adolescents called for clearer guidance regarding the school re-entry process in terms of the timing of their return to school, missing work completion, academic schedules, and on-going monitoring of their academic performance and emotional needs. They also provided insights that inform improved practice for re-entry planning such as key individuals to involve and improved ways for collaborating with adolescents and their families.

Preparing and establishing a re-entry plan for returning students has been identified as a critical step for supporting returning youth (Marraccini et al., 2019). The individuals involved in developing this plan may vary by school, but based on the experiences shared by adolescents in the current study, may include outside providers such as the adolescent’s therapist, parents or caregivers, and the adolescent themselves – stakeholders that may also help to overcome many of the communication challenges identified by professionals (Tougas et al., 2019). Key individuals supporting the adolescent’s return can be determined in consultation with the returning student. While some adolescents speculated that having strong relationships prior to hospitalization was helpful during their reintegration to school, some also described developing new relationships with school adults after returning from the hospital that may have helped ease their re-entry.

Regarding academics, adolescents called for clearer procedures related to work completion, better support for establishing academic completion timelines and deadlines, improved communication for identifying what work should be completed, and consideration of some flexibility in determining what work must be made-up. Adolescents also described the positive and negative implications of having their schedules changed and the support they received from courses focused on remediation. Taken together, adolescents recommended both a gradual re-entry process in terms of reduced time in school and reduced workload, as well as clearer expectations about work completion. The heavy burden of work completion described by some adolescents aligns to concerns described by school and hospital professionals (Clemens et al., 2010); however, less attention has been given to the immediate schedule changes described by this study’s adolescent participants. Given the variable reactions adolescents described in having their schedules change, schools should certainly prepare to engage not only with parents, but also students, in the decision making process.

A critical component of re-entry planning involves identifying school problems part of the youth ontosystem, such as social and educational difficulties, and providing interventions as needed (Marraccini et al., 2019; Tougas et al., 2019). Findings from the current study do indicate numerous social and academic concerns described by adolescents, but also indicate some creative coping strategies employed by returning adolescents. Partnering with adolescents to develop safety plans and identify appropriate interventions – both academic and social-emotional – may help strengthen re-entry plans. Furthermore, findings showcase the importance of seeking out adolescent perspectives about ongoing monitoring or check-ins, and also for providing clear expectations for academic courses and work completion. While common themes help enhance some of the key considerations in supporting adolescent return, the heterogeneity of adolescent perceptions is equally important to consider. Tailoring school re-entry plans based on individual needs and preferences may prove critical to successful school reintegration.

Because multiple adolescents reported not being able to access their counselor when needed or not actually being monitored by a school adult even after it was agreed upon, an essential component of re-entry plans may include accountability to ensure follow-through of the plan. Given the range of drivers that lead to suicide, and our limited understanding of how to predict suicide risk, it is critical that school professionals not only connect with returning adolescents when they display risk for suicide, but also support and connect with them at other times. Ongoing monitoring and strong adult relationships may help mitigate subsequent risk and also foster the trust necessary for identifying future suicidal urges.

Informational supports for returning youth and their families may be provided by a wide range of individuals, including teachers, administrators, school support professionals, and community providers. School psychologists may be involved in providing some of these supports directly; however, as experts in behavioral and mental health, school psychologists are critical for providing consultation to other school professionals more commonly involved in these processes.

Appraisal Supports

Teachers and other school professionals play a critical role in providing appraisal support to returning students by providing positive feedback regarding their academic and social-emotional progress, supporting their ongoing growth by identifying areas and skills for improvement, and acknowledging the difficult experiences they may continue to face. Yet, school professionals providing appraisal supports must also recognize that recovery from suicide-related crises may not follow a linear trajectory. Across findings, adolescents rarely described only one feeling when describing their experiences. While many reported their return to school as overwhelming and tiring, many also described the benefits of reconnecting with friends and peers. Adolescents described how they wanted to be treated with care and compassion, but also expressed a desire to be treated as they would under normal conditions. By recognizing this complexity, and preparing other school professionals to expect adolescents to display a range of behaviors and emotions, school psychologists can help prepare the school environment for returning youth. Expressions of joy and excitement can be celebrated, and should not be considered an indicator of full recovery or as a sign of malingering. School psychologists can help challenge the false assumptions of other adults in the building related to adolescents with suicidal urges needing to look a particular way.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the present study included a diverse sample of adolescents previously hospitalized for suicide-related behaviors, they were recruited from one hospital limiting the generalizability of findings. Adolescent perspectives are only one of multiple that need to be considered for improving school reintegration processes, and findings should be considered in conjunction with studies exploring hospital and school professionals and parents (Blizzard et al., 2016; Clemens et al., 2010; Simon & Savina, 2010). Future studies should jointly assess perspectives of multiple stakeholders (e.g., adolescents, parents, school professionals, hospital professionals) regarding practices and procedures for improving school re-entry. Furthermore, although the focus of present study was for school specific strategies at improving re-entry, future studies should also address additional considerations for hospital professionals in preparing families for school reintegration.

Because adolescents were hospitalized up to 6 months prior to the interview, retrospective bias may reduce the accuracy of adolescent reports. Longitudinal work, including both subjective and objective measures of adolescent experiences, is warranted to better understand the hospital to school re-entry process. In a similar vein, explorations of school-related predictors of and school-based interventions targeting adolescent recovery from suicide-related crises are sorely needed to identify the most effective ways schools can support their recovery. Although findings from this study and previous work (e.g., Marraccini et al., 2019; Savina et al., 2014; Tougas et al., 2019) have identified key recommendations for supporting returning youth, the extent to which these social supports can protect against subsequent suicidality in adolescents recovering from a suicidal crisis remains an empirical question. Inquiries into the feasibility, usability, and the efficacy of these recommendations for improving school re-entry experiences and preventing subsequent suicide-related thoughts and behaviors are a critical next step for improving practice. Finally, considering previous work that suggests only 16% of schools may have formal school re-entry process for supporting adolescents returning from psychiatric hospitalization (Marraccini et al., 2019), and adolescents’ call for clearer procedures and expectations for re-entry, school districts should prioritize developing and implementing standard protocols for school reintegration.

Conclusion

This study was one of the first to explore adolescent views on improving school re-entry following hospitalization for suicide-related behaviors. Findings highlight not only the importance of providing instrumental and informational supports for their academic return, but also strengthening emotional and appraisal supports for returning students by approaching them with compassion and care. As rates of adolescent suicide and hospitalization for suicide-related behaviors continue to rise, now more than ever it is important to listen to the voices of students struggling with suicidal urges.

Supplementary Material

Impact Statement:

This study elevates adolescent voices by describing their experiences and viewpoints regarding school reintegration following psychiatric hospitalization for suicide-related behaviors. School psychologists and other school professionals should partner with returning students and families in supporting reintegration, and collaborate to strengthen student-adult relationships upon their return. While standard protocols for supporting returning adolescents may help improve re-entry processes overall, it remains of critical importance to tailor safety plans and re-entry plans based on individual adolescent experiences.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to acknowledge the families who donated their time to this project and the Qualitative Science & Methods Training Program (QSMTP) of the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, which provided training in qualitative research methods for this manuscript.

This project was supported by Grant SRG-0-093-17 awarded to Marisa E. Marraccini from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The project described was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR002489, and internal funding from the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or UNC.

References

- Aldridge JM, & McChesney K (2018). The relationships between school climate and adolescent mental health and wellbeing: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Research, 88, 121–145. 10.1016/j.ijer.2018.01.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins MS, Cappella E, Shernoff ES, Mehta TG, & Gustafson EL (2017). Schooling and children’s mental health: realigning resources to reduce disparities and advance public health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 123–147. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blizzard AM, Weiss CL, Wideman R, & Stephan SH (2016). Caregiver perspectives during the post inpatient hospital transition: A mixed methods approach. Child and Youth Care Forum, 45(5), 759–780. 10.1007/s10566-016-9358-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, & Jager-Hyman S (2014). Evidence-based psychotherapies for suicide prevention: future directions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3), S186–S194. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (n.d.) Follow-Up After Hospitalization for Mental Illness: Ages 6 to 17. Retrieved November 07, 2020 from https://www.medicaid.gov/state-overviews/scorecard/follow-up-after-hospitalization-mental-illness-ages-6-17/index.html

- Cleary M, Visentin DC, Neil A, West S, Kornhaber R, & Large M (2019). Complexity of youth suicide and implications for health services. Journal of advanced nursing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens EV, Welfare LE, Williams AM (2010). Tough Transitions: Mental Health Care Professionals’ Perception of the Psychiatric Hospital to School Transition. Residential Treatment For Children & Youth, 27(4), 243–63. 10.1080/0886571x.2010.520631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czyz EK, Liu Z, & King CA (2012). Social connectedness and one-year trajectories among suicidal adolescents following psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(2), 214–226. 10.1080/15374416.2012.651998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen KM, & Namey EE (2012). Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks: California. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and work flow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42, 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes C, Palmer V, Hamilton B, Simons C, & Hopwood M (2019). What nonpharmacological therapeutic interventions are provided to adolescents admitted to general mental health inpatient units? A descriptive review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(3), 671–686. 10.1111/inm.12575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson P (2017). Adolescents’ experiences returning to school after a mental health hospitalization. Retrieved from: All Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. 709. http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/709. [Google Scholar]

- James S, Charlemagne SJ, Gilman AB, Alemi Q, Smith RL, Tharayil PR, & Freeman K (2010). Post-discharge services and psychiatric rehospitalization among children and youth. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37(5), 433–445. 10.1007/s10488-009-0263-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobes DA (2017). Clinical assessment and treatment of suicidal risk: A critique of contemporary care and CAMS as a possible remedy. Practice Innovations, 2(4), 207. 10.1037/pri0000054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd SA, McKenzie KJ, & Virdee G (2014). Mental health reform at a systems level: widening the lens on recovery-oriented care. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(5), 243–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Grupp-Phelan J, Brent D, Dean JM, Webb M, Bridge JA, … & Rea M (2019). Predicting 3-month risk for adolescent suicide attempts among pediatric emergency department patients. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(10), 1055–1064. 10.1111/jcpp.13087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konold T, & Cornell D (2015). Measurement and structural relations of an Authoritative School Climate model: A multi-level latent variable investigation. Journal of School Psychology, 53, 447–461. 10.1016/j.jsp.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki KC, & Kilpatrick Demary M (2002). Measuring perceived social support: development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASSS). Psychology in the Schools, 39(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Malecki CK, & Demaray MK (2003). What type of support do they need? Investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(3), 231. [Google Scholar]

- Marraccini ME, & Brier ZM (2017). School connectedness and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A systematic meta-analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(1), 5. 10.1037/spq0000192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraccini ME, Lee S, & Chin AJ (2019). School reintegration post-psychiatric hospitalization: protocols and procedures across the nation. School mental health, 11(3), 615–628. 10.1037/spq0000192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, & Michel BD (2007). Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment, 19(3), 309–317. 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik SK, Gay J, Brown C, Browning WL, Casey R, Freundlich K, Johnson DP, Lind CH, Rehm KP, Thomas S, & Williams D (2018). Hospitalization for Suicide Ideation or Attempt: 2008–2015. Pediatrics, 141. 10.1542/peds.2017-2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Nock MK, Simon V, Aikins JW, Cheah CS, & Spirito A (2008). Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts following inpatient hospitalization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 92. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preyde M, Parekh S, & Heintzman J (2018). Youths’ experiences of school re-integration following psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(1), 22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preyde M, Parekh S, Warne A, & Heintzman J (2017). School reintegration and perceived needs: The perspectives of child and adolescent patients during psychiatric hospitalization. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 34(6), 517–526. 10.1007/s10560-017-0490-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018) NVivo (Version 12).

- Savina E, Simon J, & Lester M (2014, December). School reintegration following psychiatric hospitalization: An ecological perspective. In Child & Youth Care Forum (Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 729–746). Springer US. 10.1007/s10566-014-9263-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley C (2007). Four-month follow-up of an adolescent psychiatric hospitalization: Predictors of school adjustment. (Doctoral thesis). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI Number: 3252069). Pace University, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Simone DJ (2017). Getting Back to School: Understanding Adolescents’ Experience of Reentry into School after Psychiatric Hospitalization (Doctoral dissertation, Northeastern University; ). [Google Scholar]

- Simon JB, & Savina EA (2010). Transitioning children from psychiatric hospitals to schools: The role of the special educator. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 27(1), 41–54. 10.1080/08865710903508084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Simon V, Cancilliere MK, Stein R, Norcott C, Loranger K, & Prinstein MJ (2011). Outpatient psychotherapy practice with adolescents following psychiatric hospitalization for suicide ideation or a suicide attempt. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 16(1), 53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suldo SM, Friedrich AA, White T, Farmer J, Minch D, & Michalowski J (2009). Teacher support and adolescents’ subjective well-being: A mixed-methods investigation. School Psychology Review, 38(1), 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Suldo SM, & Shaffer EJ (2008). Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. School Psychology Review, 37(1), 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tardy CH (1985). Social support measurement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 13(2), 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant JE, Demaray MK, Malecki CK, Terry MN, Clary M, & Elzinga N (2015). Students’ ratings of teacher support and academic and social–emotional well-being. School psychology quarterly, 30(4), 494. 10.1037/spq0000106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tougas AM, Rassy J, Frenette-Bergeron É, & Marcil K (2019). “Lost in Transition”: A Systematic Mixed Studies Review of Problems and Needs Associated with School Reintegration After Psychiatric Hospitalization. School Mental Health, 1–21. 10.1007/s12310-019-09323-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tossone K, Jefferis E, Bhatta MP, Bilge-Johnson S, & Seifert P (2014). Risk factors for rehospitalization and inpatient care among pediatric psychiatric intake response center patients. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 8(1), 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker RP, Crowley KJ, Davidson CL, & Gutierrez PM (2015). Risk factors, warning signs, and drivers of suicide: what are they, how do they differ, and why does it matter?. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 45(6), 679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson TN, & Bogotch I (2015). Reframing parent involvement: What should urban school leaders do differently?. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 14(3), 257–278. 10.1080/15700763.2015.1024327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]