Abstract

Background:

It is estimated that 300,000 children 0-14 years of age are diagnosed with cancer worldwide each year. While the absolute risk of cancer in children is low, in high-income countries, it is the leading cause of death due to disease in children. In spite of this, the etiologies of childhood cancer are largely unknown.

Methods:

We reviewed the literature on several components of the epidemiology of childhood cancer, including incidence, survival, risk factors, etiologic heterogeneity, and prevention. After describing known patterns in the epidemiology of childhood cancer, we propose future directions for epidemiologic research.

Results:

Recent studies indicate the worldwide incidence of childhood cancer is underestimated, especially in middle- and low-income countries. While survival continues to improve, there are significant disparities across the globe. In terms of risk factors, there are a few well-established associations including race/ethnicity, birthweight, birth defects, and ionizing radiation. Identifying novel risk factors is imperative for future prevention efforts.

Conclusions:

Future epidemiologic studies of childhood cancer should incorporate novel exposure methodologies, molecular features of tumors, and a more complete assessment of gene-environment interactions.

Impact:

It is hoped that our understanding of the causes of childhood cancer can be better ascertained, leading to novel surveillance or prevention strategies.

Keywords: pediatric cancers, epidemiology, environmental risk factors, endogenous risk factors, gene technologies

Background

It is estimated that 300,000 children 0-19 years of age are diagnosed with cancer worldwide each year (1). In high-income countries, cancer is the leading cause of death due to disease in children. The absolute risk of cancer in children is however quite low - 183 cases per million in the United States (2) - and this rarity limits attainable sample sizes and types of studies. Childhood cancers are heterogeneous and display a markedly different range of tumor types than in adults, including several classes which are largely exclusive to children. Advances in diagnostics have further split tumors into molecularly-defined subtypes which inform prognosis, therapy, and increasingly etiology. Childhood cancer epidemiology has traditionally relied on interview-based case-control studies but in recent decades has added laboratory assessment of exposure, germline DNA analysis, and molecular classification of tumors to the research repertoire.

Descriptive Epidemiology

Worldwide Incidence

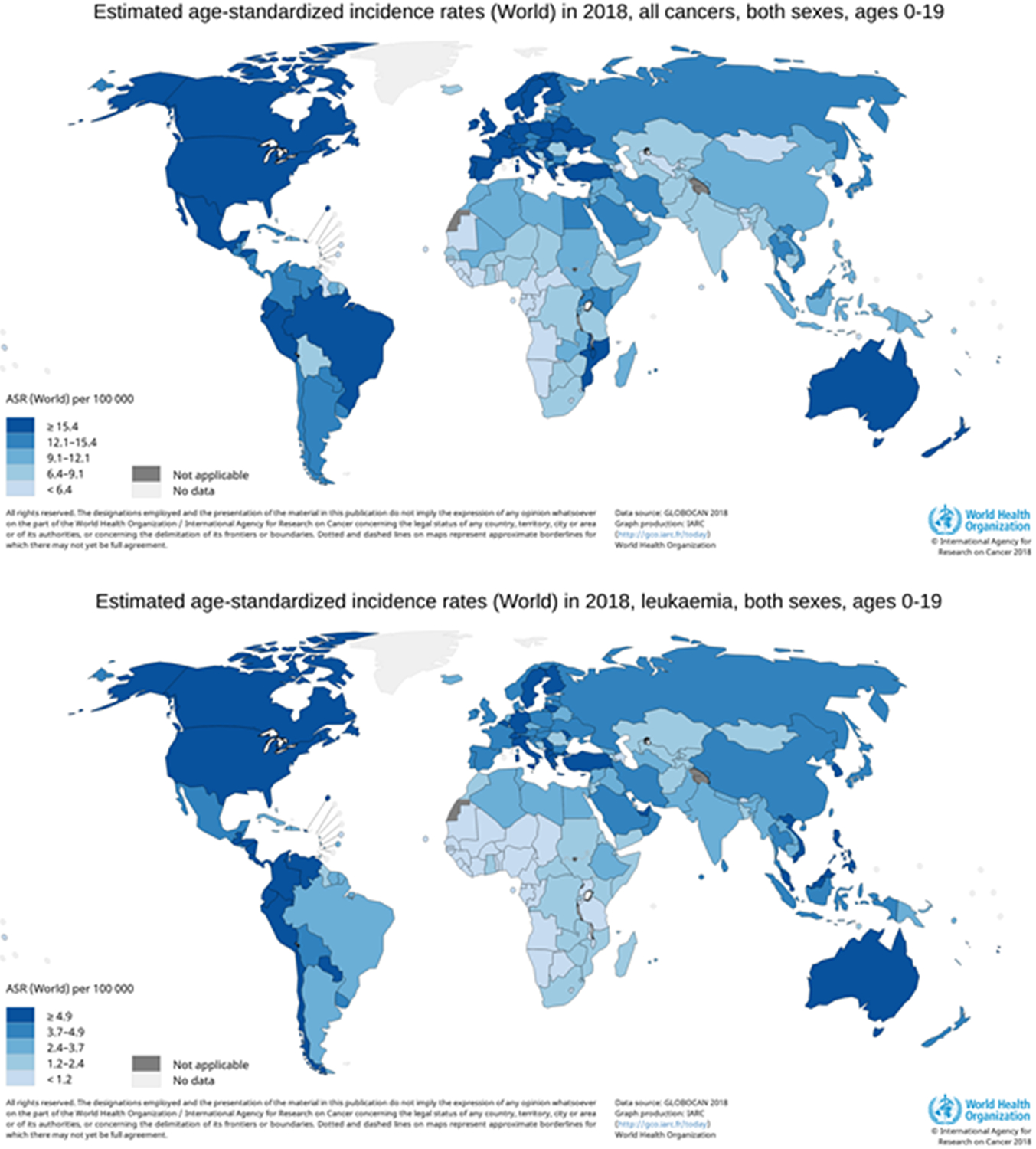

Accurate estimates of worldwide childhood cancer incidence are important for characterizing the impact of these malignancies and informing policy decisions. However, many countries do not have cancer registries that quantify the incidence of childhood cancer. It is estimated that 300,000 children are diagnosed with cancer annually. Data from GLOBOCAN are commonly used as a primary source to estimate the global incidence of childhood cancer. Notably, the incidence of childhood cancer is highest in North America, parts of South and Central America, Europe, and Australia with an age-standardized incidence rate (ASR) of ≥15.4 per 100,000 person-years for those 0-19 years of age (Figure 1a). These patterns largely hold true for leukemia diagnosed in those 0-19 years of age as well (Figure 1b). However, there are limitations to using GLOBOCAN data. For instance, data are presented according to ICD site codes, which do not reflect the major childhood cancer diagnostic groups. It is also suspected that in middle- and low-income countries poor pathology, misdiagnosis, and unascertained cases contribute to underestimation of rates. Because of this, a recent report attempted to estimate the total incidence of global childhood cancer using a simulation-based approach. In this assessment, Ward et al. estimated that there were 397,000 children 0-14 years of age diagnosed with cancer worldwide in 2015, a number much higher than GLOBOCAN estimates (3).

Figure 1.

Worldwide estimated age-standardized incidence for (a) all childhood cancer and (b) leukemia in 2018

International comparisons of rates between high-, middle-, and low-income countries using standard registry data should therefore be interpreted with the caveat that only diagnosed cancer is counted. Overall, leukemia is the most common cancer among children ages 0 to 14 years regardless of the geographic area. However, leukemias represent a slightly higher proportion of childhood cancers in Asia, Oceania, and Central and South America, while slightly lower on the African continent. In both North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa, lymphomas are more common than in other regions, due primarily to the high rates of Burkitt lymphoma. Soft-tissue sarcomas are much more common in Sub-Saharan Africa, due to the high incidence of Kaposi sarcoma in the region. Other notable differences include a lower proportion of CNS tumors but higher proportion of renal tumors in Sub-Saharan Africa, and a higher proportion of germ cell tumors in Asia.

US Incidence

Approximately 16,000 children 0-19 years of age are diagnosed with cancer in the United States (11,000 cases among children 0-14 years of age and 5,000 cases among those 15-19 years of age) (4). These numbers correspond to an ASR for all cancers of 16.4 cases per 100,000 person-years for 0-14 years and 23.3 per 100,000 person-years for 15-19 (2). Notably, the incidence of childhood cancer varies by year of life (Figure 2). Additionally, the distribution of cancer types shifts throughout childhood and adolescence. For example, non-CNS embryonal tumors are more common in early life compared to lymphomas, whereas lymphomas become relatively more common in adolescence (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of tumors across the pediatric age spectrum

As with many adult cancers, the incidence of childhood cancer varies by race/ethnicity. However, while non-Hispanic black adults often have a higher incidence of several cancers, non-Hispanic white children often experience a higher incidence of cancer relative to non-Hispanic black and Hispanic children. One notable exception is Hispanic children have higher rates of both ALL and AML compared to non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black children (2). There is emerging evidence that some of these disparities may be due to underlying genetic ancestry (5). However, this information has not been fully exploited (e.g., through admixture mapping) to better understand the etiology of childhood cancer (6).

Worldwide Survival

Worldwide, more than 100,000 children and adolescents younger than 20 years of age die from cancer per year (75,000 cancer deaths among children 0 to 14 years of age and 27,000 cancer deaths among 15- to 19-year-olds) (7). Survival is generally higher in high-income countries (HICs). Specifically, survival has consistently increased in most of Europe, North America, Japan, and Oceania (8,9). Whereas, several countries in Eastern Europe, Southeastern Asia, and Latin America have lagged behind. As with childhood cancer incidence, it is difficult to ascertain survival in countries without robust population-based cancer registries. International data presented in The Cancer Atlas (10), which is based on data from the CONCORD program show that for roughly the same time period (1990s-early 2000s), 5-year survival for childhood cancer overall was approximately 80% in high-income countries, roughly 55% in middle-income countries, and 40% in low-income countries (LICs). Furthermore, survival also differed by cancer type across those countries. Leukemia and lymphoma experience among the highest five-year survival in HICs (80% and 90%, respectively); however, in LICs only 36% and 55% of children diagnosed with leukemia and lymphoma, respectively, survive five years after their diagnosis. The disparity is even greater for CNS tumors and neuroblastoma (which were considered together as a group in the Cancer Atlas Data). Five-year survival is reported at 71% in HICs and only 27% in LICs. These trends were also demonstrated in an assessment that used a simulation-based analysis to estimate global childhood cancer survival trends. Specifically, Ward et al. reported that global 5-year net childhood cancer survival is currently 37.4% (95% uncertainty interval 34.7-39.8), with large variation by region, ranging from 8.1% (4.4-13.7) in eastern Africa to 83.0% (81.6-84.4) in North America (3).

US Survival

Childhood cancer remains the leading cause of disease-related mortality among children 1 to 14 years of age, with approximately 1,200 cancer-related deaths annually in the United States among children younger than 15 years (4). The relative contribution of cancer to overall mortality for 15- to 19-year-olds is lower than for the younger children, although approximately 600 deaths from cancer occur annually in this age group (11). Accordingly, death from cancer accounts for 12% of all deaths among children 1 to 14 years old, and 5% among adolescents (15-19 years old). However, survival rates for children 0 to 14 years of age have improved dramatically since the 1960s when the overall 5-year survival rate after a cancer diagnosis was estimated as 28% (12). Improvements in survival rates have continued into the mid-2000s in the United States, with the overall 5-year survival rate exceeding 80% for children and adolescents diagnosed during this period. In spite of this, survival does still lag for some cancer types (Figure 3). For instance, as recent data from SEER demonstrates, children diagnosed with CNS tumors, bone tumors, some types of soft tissue sarcoma, and hepatoblastoma have 5-year survival rates of <70%. While overall survival has improved in the US, there remain differences based on several factors, including sex and race/ethnicity. In terms of sex, using data from SEER, investigators demonstrated that males had worse survival compared to females for several cancers, including ALL, ependymoma, neuroblastoma, and osteosarcoma (13). Additionally, while non-Hispanic white children are more likely to be diagnosed with cancer, these children often have the best survival compared to other race/ethnicity groups. Specifically, data from SEER indicates that for most subtypes, non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics have inferior survival compared to non-Hispanic whites (14-19). Differences in survival are likely to be complex, arising from several factors, including but not limited to socioeconomic status, adherence to therapy, differences in treatment, underlying tumor biology, and genetic susceptibility (20). Therefore, future studies evaluating disparities should employ a comprehensive approach to reducing the impact of these differences.

Figure 3.

Improvements in 5-year survival for childhood cancer, SEER, 1975-2010

Risk factors

Knowledge on the etiology of childhood cancers comes mainly from case-control studies and must be interpreted within the limitations of the study design. Setting must also be considered as the vast majority of analytic epidemiology of childhood cancer have taken place in high income countries and may not generalize to lower income areas with different distributions of environmental and lifestyle risk factors. Childhood cancers are heterogeneous, and it must be recognized that each tumor has its individual risk factor profile. However there are some commonalities. For instance, the incidence is higher in males in nearly all cancers and many are thought to originate in utero. Some risk factors, like birth weight, cut across tumors but differ in the direction and magnitude of association, while others (e.g. hernias and Ewing sarcoma (21)) are unique to a particular cancer. It is also the case that the literature on causes is roughly proportional to incidence, so that we know far more about the etiology of ALL (36 cases per million) than hepatoblastoma (2.1 cases per million). Based on a review of the literature and overall impressions from the state of the field, we summarize the risk factors for childhood cancer below and in Table 1. Additionally, as there have been some reviews specifically focused on particular childhood cancers or the role of specific risk factors on a range of childhood cancers, we have also provided a table (Table 2) that outlines some of these efforts.

Table 1.

Confirmed and suspected risk factors for selected childhood cancers

| ALL | AML | NB | HB | RB | WT | MB | PNET | Ependymoma | Astrocytoma | Strength of evidence |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preconception/pregnancy | |||||||||||

| Smoking | ++ | ||||||||||

| Vitamins | ++ | ||||||||||

| Occupational exposures | ++ | ||||||||||

| Residential exposures | ++ | ||||||||||

| Coffee | + | ||||||||||

| Alcohol | ++ | ||||||||||

| Ionizing radiation | +++ | ||||||||||

| Birth | |||||||||||

| Maternal age | ++ | ||||||||||

| Paternal age | ++ | ||||||||||

| Chromosomal birth defects | +++ | ||||||||||

| Non-chromosomal birth defects | +++ | ||||||||||

| High birthweight | +++ | ||||||||||

| Low birthweight | +++ | ||||||||||

| C-section | + | ||||||||||

| Gestational age | + | ||||||||||

| Childhood | |||||||||||

| Breastfeeding | + | ||||||||||

| Allergies | ++ | ||||||||||

| Residential chemical | + | ||||||||||

| Passive smoke | + | ||||||||||

| Irradiation | ++ |

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; NB, neuroblastoma; HB, hepatoblastoma; RB, retinoblastoma; WT, Wilms tumor; MB, medulloblastoma; PNET, primitive neuroectodermal tumor. For strength of evidence:

epidemiologic evidence with little mechanistic support

can cross placenta or has developmental consequences but epidemiologic evidence is equivocal

| Positive, effect estimate > 1.5 | |

| Positive, effect estimate ≥ 1.5 | |

| No association | |

| Negative, effect estimate < 0.67 | |

| Negative, effect estimate ≤ 0.67 | |

| Inconclusive |

Table 2.

Selected reviews for childhood cancer and associated risk factors

| Topic | Authors | Year | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood cancers | |||

| ALL | Williams et al. | 2019 | 30770347 |

| AML | Puumala et al. | 2013 | 23303597 |

| Brain tumors | Johnson et al. | 2014 | 25192704 |

| Hepatoblastoma | Spector and Birch | 2012 | 22692949 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Skapek et al. | 2019 | 30617281 |

| Wilms tumor | Chu et al. | 2010 | 20670226 |

| Risk factros | |||

| Pesticides | Chen et al. | 2015 | 26371195 |

| Ionizing radiation | Kendall et al. | 2018 | 30131551 |

| Genetic predisposition | Plon and Lupo | 2019 | 31082280 |

Demographics

Age, sex, and race/ethnicity each influence the risk of childhood cancer. Figure 2 shows the distribution of tumors across the pediatric age spectrum. Leukemias, primarily ALL, display a distinct peak in incidence from age 2 to 5 years, while CNS tumors have fairly steady incidence throughout childhood. Non-CNS embryonal tumors have peak incidence in infancy, which then falls to near zero by ten years of age. There is a peak in incidence of bone and soft tissue sarcomas in mid-adolescence, as well as increasing incidence of lymphoma and other solid tumors that continues well into adulthood. Males have a higher risk for most childhood cancers, with rate ratios ranging from 6 for Burkitt lymphoma to 1.2 for AML; Wilms tumor, extragonadal GCT, thyroid carcinoma, and melanoma are notable for having slightly higher rates in females (22). The United States published cancer rates by race/ethnicity and so these data are often used to compare incidence. With few exceptions, the rate of childhood cancer is 25-50% lower in black compared to white children; the rate of ALL is higher among Hispanic children but for most solid tumors lower than in white children; incidence among Asian children is roughly similar to white children although some (i.e. neuroblastoma and Wilms tumor) have lower rates while germ cell tumors have dramatically higher rates (23).

Gestational and Perinatal

Due to the young age of onset, histologic resemblance of some pediatric cancer cells to embryonal cells, and pre- or perinatal detection of multiple types of cancer, most childhood cancers are thought to initiate in utero. Consequently, gestation is frequently examined as a critical window of risk. Birth weight, alone or with consideration of gestational age, has been most often studied (Table 1). Risk of most childhood cancers rises with increasing birth weight, from 5% per 500g increase for astrocytomas to 17% per 500g for Wilms tumor (24); hepatoblastoma, which is strongly associated with low birth weight, is the exception (25). Another consistent finding is that children with structural birth defects without a reported genetic syndrome have an elevated risk of pediatric cancer (26). Risk ratios for specific birth defect-cancer combinations range from 1.5 to 6.0 and the associations are apparent for most classes of birth defects and cancer (Table 1). Parental age at birth of offspring is also consistently associated with most types of childhood cancer, with between 5% and 10% higher risk per 5 years of maternal age; paternal age may also be associated with higher risk of pediatric cancer, although the tight correlation with maternal age and the greater degree of missing data make it harder to assess (27-31). There is some suggestive evidence that pathologies of pregnancy, such as pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes, and maternal obesity increase risk of childhood cancers but the evidence base is currently thin (32-37).

Environmental

While key environmental exposures have been identified for adult cancers (e.g., smoking, benzene), much less is known in relation to childhood cancer. A notable difference between adult cancers and childhood cancers is the latency period associated with these conditions. For instance, smoking usually starts during adolescence or young adulthood, but associated malignancies do not become apparent until many decades later. However, several childhood cancers are predominantly diagnosed in infancy (e.g., embryonal neoplasms such as neuroblastoma) or in early childhood (2 to 5 years of age), such as ALL. Therefore, the disruption in molecular processes that may lead to childhood cancer are likely different from those of adult cancers; at the least, the carcinogenic process in children is necessarily much shorter in time. Additionally, because of the age of onset, it is reasonable to surmise that many childhood cancers result from aberrations in early developmental processes. The current evidence to support a major etiologic role for environmental or other exogenous factors in childhood cancer is minimal (Table 1). While there is extensive evidence that high doses of ionizing radiation are associated with childhood cancer, the prevalence of this exposure is very low (38). Relatively common environmental exposures, including pesticides (39) and air pollution (40) have also been explored. While individual studies and meta-analyses have indicated associations between these exposures and some childhood cancers, effect sizes are relatively modest. One problem with previous studies of environmental exposures includes the limitations of using questionnaire data to estimate exposure or the use of proxies for exposure assessment (e.g., residential information). While residential information is arguably better than self-reported exposures, epidemiologic studies of childhood cancer must leverage novel approaches to better characterize the role environment in etiology. For example, correlating information on environmental exposures to the landscape of somatic mutations could provide novel insights into the carcinogenic properties of these factors (41).

Genetic Variation

Chromosomal abnormalities, subchromosomal structural variation, and pathogenic germline point mutations confer a sharply increased risk of cancer but underlie a minority of cases of childhood cancer (42-45). Next-generation sequencing studies have yielded precise estimates of the prevalence of germline pathogenic variation in most types of childhood cancer; for a few types such as adrenocortical carcinoma or hypodiploid ALL half or more of cases have such variation, while in most cancers the prevalence is 5-10% (46,47). In fact, according to a large-scale effort by Zhang et al., those childhood cancers where >10% can be attributed to highly penetrant pathogenic variants in known cancer predisposition genes include osteosarcoma, retinoblastoma, and adrenocortical carcinoma (47). Continued sequencing efforts have also yielded novel, rare, high-penetrance predisposition genes (48) and moderately-rare, medium-penetrance variation (49-51). Importantly, there has been a recent systematic effort to outline the guidelines for pediatric cancer predisposition surveillance. While it is beyond the scope of this review to fully outline those recommendations, they can be found at https://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/pediatricseries (52).

Against expectations genomewide association studies (GWAS) have succeeded in identifying common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with several childhood cancers despite sample sizes that, at least initially, fell far short of recommendations. This is likely due to the interesting and as yet unexplained fact that the magnitude of association of common SNPs with childhood cancer is greater than in adults (23), which seems to be a general property of pediatric diseases (53). The genetic architectures of ALL and neuroblastoma are mature, with multiple validated loci, subtype-specific associations, transethnic replication, and ethnically-specific loci (49-51,54-59). Two GWAS of Ewing sarcoma in European populations have also identified multiple loci (60,61), but genetic risk in non-European populations has not been examined. Single GWAS of Wilms tumor (62) and osteosarcoma (63) have also identified a limited number of loci. More recently investigators have demonstrated associations of childhood cancers with trait-related variation, such as genetically-determined telomere length (64) and height (65). The most significant variants found to be associated with childhood cancers in GWAS are depicted in Figure 4. While potential mechanisms for the genetic associations have been proposed (57-63), there have been few efforts to fully elucidate the functional consequences of variants identified in GWAS of childhood cancers. This is in part due to several variants being intronic or intergenic (63). However, there are some emerging efforts to elucidate the role of variants and genes identified in GWAS of childhood cancer, including Ewing sarcoma-related loci (66), IKZF1 variants and ALL (67), and BMI1 variants and ALL (68). Many SNPs do appear to be associated with lymphocyte development; however, additional work is needed to explore the biological underpinnings of these associations. Lastly, while small studies have examined transethnic replication of GWAS SNPs discovered in Europeans, genomewide discovery has mostly not been performed in non-European populations despite many recent calls to diversify genomic research.

Figure 4.

Genes and variants identified in GWAS of childhood cancer; up to 5 of the top SNPs with p < 10-8 in the GWAS catalogue (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/home) are displayed, with information for recent GWAS of T-cell ALL and LCH added.

Etiologic heterogeneity

There is emerging evidence that etiologic heterogeneity within childhood cancer subtypes may have limited previous epidemiologic assessments of these conditions. Furthermore, our understanding of subtypes continues to emerge. For example, ALL has traditionally been classified as B-cell or T-cell, based on the cell type affected. However, advances in cytogenetics has led to the latest version of the WHO classification of ALL to include several subtypes defined by their translocations and other cytogenetic features: BCR-ABL1, MLL rearranged, TEL-AML1, hyperdiploidy, hypodiploidy, IL3-IGH, and E2A-PBX1 (69). Another example is rhabdomyosarcoma, which was originally classified by histological type, e.g., embryonal vs. alveolar. However, through molecular advancements, further distinctions due to specific gene fusions between either PAX3 or PAX7 and FOXO1 that typically occur among the previously named alveolar types, are preferred risk stratification strategies compared to histology alone (70). Recent advances in genomics, epigenomics, and transcriptomics have allowed for molecular subtyping for a number of childhood malignancies. For example, at least four molecular subgroups of childhood medulloblastoma now exist (WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4), each exhibiting different molecular and clinical features (71); more recent tumor phenotyping suggests even further subtypes (72). Likewise, for other brain tumors, distinct molecular subgroups have now been established for ependymoma (73), high-grade gliomas (74), low-grade gliomas (75), and AT/RT (76). Recently, four molecular subtypes have been suggested for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: MCD (harboring the co-occurrence of MYD88L265P and CD79B mutations), BN2 (harboring BCL6 fusions and NOTCH2 mutations), N1 (harboring NOTCH1 mutations), and EZB (harboring EZH2 mutations and BCL2 translocations) (77). Less often, molecular analyses have suggested “lumping” tumors previously thought to be dissimilar, as with Ewing sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNET), which both frequently feature the EWS-FLI1 translocation (78). Also, GWAS of childhood cancers (including ALL and neuroblastoma) have pointed to differences in association between SNPs and molecularly-defined subtypes (79,80). These are just a few examples of the emerging landscape of tumor subtypes based on molecular features. Future epidemiologic studies must account for this information as etiologic factors could differ based on these characteristics.

Screening and Prevention

The ultimate goal of etiologic research in childhood cancer is to enable risk prediction, early detection, and, eventually, prevention. However, these goals remain distant for most children. Population-wide screening for pediatric cancer has, to our knowledge, only been attempted for neuroblastoma. The basis for screening was homovanillic acid, a catecholamine metabolite which serves as a biomarker for tumor burden in neuroblastoma and which is shed in urine. Thus in the late 1980s and 1990s screening for neuroblastoma in infants was attempted in three areas with the capacity for population-wide urine collection in infants: Quebec (81), Germany (82), and Japan (83). While these programs succeeded in identifying neuroblastoma earlier than clinical diagnosis, they did not improve mortality as they primarily detected favorable cases with a regressing phenotype, many of which would never have come to clinical attention. Hence, these programs were abandoned (84).

More recently, experts have issued recommendations in support of surveillance for tumor development in children with most genetic syndromes conferring high risk of cancer (85). Although there are few preventive measures to implement, there is consensus that surveillance can reduce morbidity and mortality through early detection. Screening for cancer predisposition, as opposed to screening for cancer in those with known predispositions, is more controversial. Newborn screening increasingly involves genetic in addition to metabolic testing (86), and thus could easily detect most types of pathogenic variation in cancer-associated genes. However, many screening programs prefer to include only conditions that are early-onset and for which there are interventions proven to improve outcome (87), which does not describe most pediatric cancers. Thus to our knowledge only one area in the world has instituted newborn screening for pediatric cancer predisposition, in the Brazilian state of Paraná where the R337H founder mutation in TP53 has an especially high prevalence (88).

Prevention of pediatric cancer is not yet feasible for a number of reasons. The first is simply that for diseases as rare as these the number needed to “treat” with an intervention would be impractically large, possibly population-wide, and consequently would be economically unfavorable. A second reason is that, as discussed above, there are no modifiable risk factors for childhood cancer that are strong and prevalent enough to justify intervention. However, most of the modifiable risk factors for pediatric cancer (e.g. maternal smoking, obesity, air pollution) are also associated with far more common diseases, thus efforts to reduce exposure for other reasons may have the effect of reducing childhood cancer incidence.

Future directions

Molecular Epidemiology

Initial epidemiologic studies of childhood cancer gathered data mainly by parental interview and medical record abstraction. These assessments relied on the case-control study design. However, the focus of the past decade has largely been on the molecular epidemiology of childhood cancers. This has been facilitated in part through the case-parent trio study design. Case-parent trios allow the estimation of inherited genetic effects, maternal genetic effects (which can be used as a proxy or mediator of the intrauterine environment), and gene-environment interactions. Additionally, the case-parent trio approach does not require the inclusion of a control group, which is a practical advantage, as control selection on the national scale has become increasingly difficult in recent years. This is in part due to the reliance on random digit dialing for control selection (89). Another option for control selection is utilizing birth certificate controls, which have been leveraged for two Children’s Oncology Group (COG) studies (90,91), as well as studies of other pediatric and perinatal outcomes (92). This could be a feasible approach for epidemiology studies of childhood cancer that require a comparison group. However, the scientific and practical appeal of the case-parent trio design for molecular epidemiology studies remains compelling. Because of this, several recent COG epidemiology studies have relied on this approach. This includes studies of osteosarcoma (93), neuroblastoma (94), Wilms tumor, Ewing sarcoma, germ cell tumors (95), and rhabdomyosarcoma. However, beyond genetic susceptibility to childhood cancer, few studies have explored using biological markers of exposure in studies of childhood cancer, which is in part due to the limited availability of samples collected prior to diagnosis. An emerging and important population-based resource for molecular epidemiology of childhood cancer is the use of dried blood spots (DBS) collected and archived as part of newborn screening efforts. DBS have been used in genetic epidemiology studies of childhood cancer (67), as well as using metabolomics to reveal novel ALL phenotypes (96). Additionally, DBS can be used to estimate prenatal exposures, including cotinine from tobacco smoke (97) and benzene (98).

There are also methods for leveraging genetic data to address questions not necessarily related to inherited genetic susceptibility. Two primary examples are 1) evaluating maternal genetic effects (as described earlier), which can be done using parental genetic data from case-parent trios (99); and 2) Mendelian randomization (100), which is a method of using genetic variation to examine the effect of an exposure (or another trait like birth weight) on disease in observational studies. These methods are more recently being leveraged in epidemiologic studies of childhood cancer. For instance, there has been an exome-wide association study of maternal genetic effects on ALL (101). Additionally, Mendelian randomization has been used to characterize the role of height on osteosarcoma risk (65) and telomere length on neuroblastoma risk (64).

A final underexplored area in the molecular epidemiology of childhood cancer is leveraging epigenetics, especially as these modifications relate to germline DNA. Notably, environmental exposures can lead to epigenetic modifications that influence gene expression and can modulate disease risk associated with genetic variation (101). For example, there is emerging evidence that air pollution exposure (a suspected risk factor for several childhood cancers) is associated with changes in DNA methylation (102). Therefore, a novel approach in better ascertaining the association between air pollution and particular childhood cancers could be evaluating DNA methylation marks associated with this exposure. Epigenetics therefore holds substantial promise for identifying mechanisms through which genetic and environmental factors jointly contribute to childhood cancer risk and outcome. As the underlying etiologies of the vast majority of childhood cancers appear multifactorial, including both genetic and environmental risk factors, molecular epidemiology will continue to be an important component in the assessment of these conditions.

Tumor Biology

As discussed, there is a growing awareness of the molecular heterogeneity within childhood cancer subtypes. As this molecular heterogeneity could point to etiologic heterogeneity, it will be vital to incorporate information on somatic mutations in future epidemiologic studies of childhood cancer. Furthermore, information on somatic mutations could be leveraged to better understand biological processes underlying etiology. For example, in an assessment by Alexandrov et al. of over 7,000 tumors yielded more than 20 distinct mutational signatures, which were associated with various features including age, mutagenic exposures, and defects in DNA maintenance (41). Additionally, several of these mutational signatures are of “cryptic” origin. Epidemiologic assessments that characterize the exposures associated with these signatures could yield novel insights into the mutational processes underlying the development of cancer with potential implications for prevention and therapy.

Global Epidemiology

It should be noted that the overwhelming majority of etiologic studies of ALL have been conducted in high-income countries, especially the United States and countries in Europe. It is critical that future studies include populations in middle- and low-income countries as exposures as well as genetic variation are likely to differ in these populations and etiologic features may differ.

Conclusion

While there have been tremendous strides in improving outcomes for children with cancer, there is still a great deal of work related to disentangling the etiologic origins of these conditions. Future studies should incorporate novel exposure methodologies, molecular features of tumors, and a more complete assessment of gene-environment interactions. Through these efforts, it is hoped that our understanding of the causes of childhood cancer can be better ascertained, leading to novel surveillance or prevention strategies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the work of the Children’s Oncology Group Epidemiology Committee in supporting this work.

Financial Information

Work from this manuscript was funded in part through the National Cancer Institute (U10CA180886), Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT RP170071 and RP180755), and St. Baldrick’s Foundation (522277).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bhakta N, Force LM, Allemani C, Atun R, Bray F, Coleman MP, et al. Childhood cancer burden: a review of global estimates. Lancet Oncol 2019;20(1):e42–e53 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30761-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2017. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/, based on November 2017 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, Frazier AL, Atun R. Estimating the total incidence of global childhood cancer: a simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol 2019;20(4):483–93 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30909-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures, 2019. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, Inc.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spector LG, DeWan A, Pankratz N, Turcotte L, Yang J, Scheurer M. Race/ethnicty, socioeconomic position, and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. American Journal of Epidemiology;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim JY-S, Bhatia S, Robison LL, Yang JJ. Genomics of racial and ethnic disparities in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer 2014;120(7):955–62 doi 10.1002/cncr.28531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferlay J GLOBOCAN 2018. Lyon, France: World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Negri E, Levi F, La Vecchia C. Childhood cancer mortality in Europe, 1970-2007. Eur J Cancer 2010;46(2):384–94 doi 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatenoud L, Bertuccio P, Bosetti C, Levi F, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Childhood cancer mortality in America, Asia, and Oceania, 1970 through 2007. Cancer 2010;116(21):5063–74 doi 10.1002/cncr.25406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jemal A The Cancer Atlas, 2nd Edition. American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics. Apr 25, 2019. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2017 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released December, 2018. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2017, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. <http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html>. Apr 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ries LAG, SEER Program (National Cancer Institute (U.S.)). Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents : United States SEER program 1975-1995 /[edited by Gloecker Ries Lynn A. … et al. ]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, SEER Program; 1999. vi, 182 p. p. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams LA, Spector LG. Survival Differences Between Males and Females Diagnosed With Childhood Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectrum 2019;3(2) doi 10.1093/jncics/pkz032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amirian ES. The role of Hispanic ethnicity in pediatric Wilms' tumor survival. Pediatric Hematology and Oncology 2013;30(4):317–27 doi 10.3109/08880018.2013.775618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes L, Chavan P, Blake T, Dabney K. Unequal Cumulative Incidence and Mortality Outcome in Childhood Brain and Central Nervous System Malignancy in the USA. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2018;5(5):1131–41 doi 10.1007/s40615-018-0462-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs AJ, Lindholm EB, Levy CF, Fish JD, Glick RD. Racial and ethnic disparities in treatment and survival of pediatric sarcoma. The Journal of Surgical Research 2017;219:43–9 doi 10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadan-Lottick NS, Ness KK, Bhatia S, Gurney JG. Survival variability by race and ethnicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA 2003;290(15):2008–14 doi 10.1001/jama.290.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn JM, Keegan TH, Tao L, Abrahão R, Bleyer A, Viny AD. Racial disparities in the survival of American children, adolescents, and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myelogenous leukemia, and Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer 2016;122(17):2723–30 doi 10.1002/cncr.30089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panagopoulou P, Georgakis MK, Baka M, Moschovi M, Papadakis V, Polychronopoulou S, et al. Persisting inequalities in survival patterns of childhood neuroblastoma in Southern and Eastern Europe and the effect of socio-economic development compared with those of the US. European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2018;96:44–53 doi 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatia S Disparities in cancer outcomes: lessons learned from children with cancer. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2011;56(6):994–1002 doi 10.1002/pbc.23078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valery PC, Holly EA, Sleigh AC, Williams G, Kreiger N, Bain C. Hernias and Ewing's sarcoma family of tumours: a pooled analysis and meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology 2005;6(7):485–90 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70242-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams LA, Richardson M, Marcotte EL, Poynter JN, Spector LG. Sex ratio among childhood cancers by single year of age. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2019;66(6):e27620 doi 10.1002/pbc.27620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow EJ, Puumala SE, Mueller BA, Carozza SE, Fox EE, Horel S, et al. Childhood cancer in relation to parental race and ethnicity: a 5-state pooled analysis. Cancer 2010;116(12):3045–53 doi 10.1002/cncr.25099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Neill KA, Murphy MF, Bunch KJ, Puumala SE, Carozza SE, Chow EJ, et al. Infant birthweight and risk of childhood cancer: international population-based case control studies of 40 000 cases. International Journal of Epidemiology 2015;44(1):153–68 doi 10.1093/ije/dyu265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spector LG, Puumala SE, Carozza SE, Chow EJ, Fox EE, Horel S, et al. Cancer risk among children with very low birth weights. Pediatrics 2009;124(1):96–104 doi 10.1542/peds.2008-3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lupo P Cancer Risk among Children and Adolescents with Birth Defects: A Population-Based Assessment in 10 Million Live Births. JAMA Oncology;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Contreras ZA, Hansen J, Ritz B, Olsen J, Yu F, Heck JE. Parental age and childhood cancer risk: A Danish population-based registry study. Cancer Epidemiol 2017;49:202–15 doi 10.1016/j.canep.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dockerty JD, Draper G, Vincent T, Rowan SD, Bunch KJ. Case-control study of parental age, parity and socioeconomic level in relation to childhood cancers. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30(6):1428–37 doi 10.1093/ije/30.6.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson KJ, Carozza SE, Chow EJ, Fox EE, Horel S, McLaughlin CC, et al. Parental age and risk of childhood cancer: a pooled analysis. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2009;20(4):475–83 doi 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a5a332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcotte EL, Druley TE, Johnson KJ, Richardson M, von Behren J, Mueller BA, et al. Parental Age and Risk of Infant Leukaemia: A Pooled Analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2017;31(6):563–72 doi 10.1111/ppe.12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yip BH, Pawitan Y, Czene K. Parental age and risk of childhood cancers: a population-based cohort study from Sweden. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35(6):1495–503 doi 10.1093/ije/dyl177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Contreras ZA, Ritz B, Virk J, Cockburn M, Heck JE. Maternal pre-pregnancy and gestational diabetes, obesity, gestational weight gain, and risk of cancer in young children: a population-based study in California. Cancer causes & control: CCC 2016;27(10):1273–85 doi 10.1007/s10552-016-0807-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deleskog A, den Hoed M, Tettamanti G, Carlsson S, Ljung R, Feychting M, et al. Maternal diabetes and incidence of childhood cancer - a nationwide cohort study and exploratory genetic analysis. Clinical Epidemiology 2017;9:633–42 doi 10.2147/CLEP.S147188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kessous R, Wainstock T, Walfisch A, Sheiner E. The risk for childhood malignancies in the offspring of mothers with previous gestational diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study. European journal of cancer prevention: the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP) 2018. doi 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Søegaard SH, Rostgaard K, Kamper-Jørgensen M, Schmiegelow K, Hjalgrim H. Maternal diabetes and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in the offspring. British Journal of Cancer 2018;118(1):117–20 doi 10.1038/bjc.2017.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stacy SL, Buchanich JM, Ma Z-q, Mair C, Robertson L, Sharma RK, et al. Maternal Obesity, Birth Size, and Risk of Childhood Cancer Development. American Journal of Epidemiology doi 10.1093/aje/kwz118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu X, Ritz B, Cockburn M, Lombardi C, Heck JE. Maternal Preeclampsia and Odds of Childhood Cancers in Offspring: A California Statewide Case-Control Study. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 2017;31(2):157–64 doi 10.1111/ppe.12338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kendall GM, Bithell JF, Bunch KJ, Draper GJ, Kroll ME, Murphy MFG, et al. Childhood cancer research in oxford III: The work of CCRG on ionising radiation. British Journal of Cancer 2018;119(6):771–8 doi 10.1038/s41416-018-0182-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen M, Chang C-H, Tao L, Lu C. Residential Exposure to Pesticide During Childhood and Childhood Cancers: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2015;136(4):719–29 doi 10.1542/peds.2015-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Filippini T, Hatch EE, Rothman KJ, Heck JE, Park AS, Crippa A, et al. Association between Outdoor Air Pollution and Childhood Leukemia: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Environmental health perspectives 2019;127(4):46002- doi 10.1289/EHP4381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SAJR, Behjati S, Biankin AV, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013;500(7463):415–21 doi 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plon SE, Lupo PJ. Genetic Predisposition to Childhood Cancer in the Genomic Era. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ripperger T, Bielack SS, Borkhardt A, Brecht IB, Burkhardt B, Calaminus G, et al. Childhood cancer predisposition syndromes-A concise review and recommendations by the Cancer Predisposition Working Group of the Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology. Am J Med Genet A 2017;173(4):1017–37 doi 10.1002/ajmg.a.38142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross JA, Spector LG, Robison LL, Olshan AF. Epidemiology of leukemia in children with Down syndrome. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2005;44(1):8–12 doi 10.1002/pbc.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zimmerman R, Schimmenti L, Spector L. A Catalog of Genetic Syndromes in Childhood Cancer. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2015;62(12):2071–5 doi 10.1002/pbc.25726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parsons DW, Roy A, Yang Y, Wang T, Scollon S, Bergstrom K, et al. Diagnostic Yield of Clinical Tumor and Germline Whole-Exome Sequencing for Children With Solid Tumors. JAMA oncology 2016;2(5):616–24 doi 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J, Walsh MF, Wu G, Edmonson MN, Gruber TA, Easton J, et al. Germline Mutations in Predisposition Genes in Pediatric Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine 2015;373(24):2336–46 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1508054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahamdallie S, Yost S, Poyastro-Pearson E, Holt E, Zachariou A, Seal S, et al. Identification of new Wilms tumour predisposition genes: an exome sequencing study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 2019;3(5):322–31 doi 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30018-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Churchman ML, Qian M, Te Kronnie G, Zhang R, Yang W, Zhang H, et al. Germline Genetic IKZF1 Variation and Predisposition to Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2018;33(5):937–48.e8 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moriyama T, Metzger ML, Wu G, Nishii R, Qian M, Devidas M, et al. Germline genetic variation in ETV6 and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a systematic genetic study. The Lancet Oncology 2015;16(16):1659–66 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00369-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah S, Schrader KA, Waanders E, Timms AE, Vijai J, Miething C, et al. A recurrent germline PAX5 mutation confers susceptibility to pre-B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nature Genetics 2013;45(10):1226–31 doi 10.1038/ng.2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brodeur GM, Nichols KE, Plon SE, Schiffman JD, Malkin D. Pediatric Cancer Predisposition and Surveillance: An Overview, and a Tribute to Alfred G. Knudson Jr. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23(11):e1–e5 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agopian AJ, Eastcott LM, Mitchell LE. Age of onset and effect size in genome-wide association studies. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2012;94(11):908–11 doi 10.1002/bdra.23066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Diskin SJ, Capasso M, Schnepp RW, Cole KA, Attiyeh EF, Hou C, et al. Common variation at 6q16 within HACE1 and LIN28B influences susceptibility to neuroblastoma. Nat Genet 2012;44(10):1126–30 doi 10.1038/ng.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maris JM, Mosse YP, Bradfield JP, Hou C, Monni S, Scott RH, et al. Chromosome 6p22 locus associated with clinically aggressive neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med 2008;358(24):2585–93 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa0708698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qian M, Xu H, Perez-Andreu V, Roberts KG, Zhang H, Yang W, et al. Novel susceptibility variants at the ERG locus for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Hispanics. Blood 2019;133(7):724–9 doi 10.1182/blood-2018-07-862946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trevino LR, Yang W, French D, Hunger SP, Carroll WL, Devidas M, et al. Germline genomic variants associated with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 2009;41(9):1001–5 doi 10.1038/ng.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang K, Diskin SJ, Zhang H, Attiyeh EF, Winter C, Hou C, et al. Integrative genomics identifies LMO1 as a neuroblastoma oncogene. Nature 2011;469(7329):216–20 doi 10.1038/nature09609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiemels JL, Walsh KM, de Smith AJ, Metayer C, Gonseth S, Hansen HM, et al. GWAS in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia reveals novel genetic associations at chromosomes 17q12 and 8q24.21. Nature Communications 2018;9(1):286 doi 10.1038/s41467-017-02596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Machiela MJ, Grunewald TGP, Surdez D, Reynaud S, Mirabeau O, Karlins E, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple new loci associated with Ewing sarcoma susceptibility. Nat Commun 2018;9(1):3184 doi 10.1038/s41467-018-05537-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Postel-Vinay S, Veron AS, Tirode F, Pierron G, Reynaud S, Kovar H, et al. Common variants near TARDBP and EGR2 are associated with susceptibility to Ewing sarcoma. Nat Genet 2012;44(3):323–7 doi 10.1038/ng.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Turnbull C, Perdeaux ER, Pernet D, Naranjo A, Renwick A, Seal S, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for Wilms tumor. Nat Genet 2012;44(6):681–4 doi 10.1038/ng.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Savage SA, Mirabello L, Wang Z, Gastier-Foster JM, Gorlick R, Khanna C, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two susceptibility loci for osteosarcoma. Nat Genet 2013;45(7):799–803 doi 10.1038/ng.2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walsh KM, Whitehead TP, de Smith AJ, Smirnov IV, Park M, Endicott AA, et al. Common genetic variants associated with telomere length confer risk for neuroblastoma and other childhood cancers. Carcinogenesis 2016;37(6):576–82 doi 10.1093/carcin/bgw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang C, Morimoto LM, de Smith AJ, Hansen HM, Gonzalez-Maya J, Endicott AA, et al. Genetic determinants of childhood and adult height associated with osteosarcoma risk. Cancer 2018;124(18):3742–52 doi 10.1002/cncr.31645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Musa J, Cidre-Aranaz F, Aynaud MM, Orth MF, Knott MML, Mirabeau O, et al. Cooperation of cancer drivers with regulatory germline variants shapes clinical outcomes. Nat Commun 2019;10(1):4128 doi 10.1038/s41467-019-12071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brown AL, de Smith AJ, Gant VU, Yang W, Scheurer ME, Walsh KM, et al. Inherited genetic susceptibility of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Down syndrome. Blood 2019. doi 10.1182/blood.2018890764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Smith AJ, Walsh KM, Francis SS, Zhang C, Hansen HM, Smirnov I, et al. BMI1 enhancer polymorphism underlies chromosome 10p12.31 association with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Cancer 2018;143(11):2647–58 doi 10.1002/ijc.31622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mrozek K, Harper DP, Aplan PD. Cytogenetics and molecular genetics of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2009;23(5):991–1010, v doi 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Skapek SX, Ferrari A, Gupta AA, Lupo PJ, Butler E, Shipley J, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019;5(1):1 doi 10.1038/s41572-018-0051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Northcott PA, Jones DT, Kool M, Robinson GW, Gilbertson RJ, Cho YJ, et al. Medulloblastomics: the end of the beginning. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12(12):818–34 doi 10.1038/nrc3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ma X, Liu Y, Liu Y, Alexandrov LB, Edmonson MN, Gawad C, et al. Pan-cancer genome and transcriptome analyses of 1,699 paediatric leukaemias and solid tumours. Nature 2018;555(7696):371–6 doi 10.1038/nature25795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson RA, Wright KD, Poppleton H, Mohankumar KM, Finkelstein D, Pounds SB, et al. Cross-species genomics matches driver mutations and cell compartments to model ependymoma. Nature 2010;466(7306):632–6 doi 10.1038/nature09173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang DA, Jones DT, Konermann C, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 2012;22(4):425–37 doi 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang J, Wu G, Miller CP, Tatevossian RG, Dalton JD, Tang B, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in pediatric low-grade gliomas. Nat Genet 2013;45(6):602–12 doi 10.1038/ng.2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Torchia J, Picard D, Lafay-Cousin L, Hawkins CE, Kim SK, Letourneau L, et al. Molecular subgroups of atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumours in children: an integrated genomic and clinicopathological analysis. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(5):569–82 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schmitz R, Wright GW, Huang DW, Johnson CA, Phelan JD, Wang JQ, et al. Genetics and Pathogenesis of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2018;378(15):1396–407 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1801445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ladanyi M EWS-FLI1 and Ewing's sarcoma: recent molecular data and new insights. Cancer Biol Ther 2002;1(4):330–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tolbert VP, Coggins GE, Maris JM. Genetic susceptibility to neuroblastoma. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 2017;42:81–90 doi 10.1016/j.gde.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Williams LA, Yang JJ, Hirsch BA, Marcotte EL, Spector LG. Is There Etiologic Heterogeneity between Subtypes of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia? A Review of Variation in Risk by Subtype. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers 2019. doi 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Woods WG, Gao R-N, Shuster JJ, Robison LL, Bernstein M, Weitzman S, et al. Screening of infants and mortality due to neuroblastoma. The New England Journal of Medicine 2002;346(14):1041–6 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa012387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schilling FH, Spix C, Berthold F, Erttmann R, Fehse N, Hero B, et al. Neuroblastoma Screening at One Year of Age. New England Journal of Medicine 2002;346(14):1047–53 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa012277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hiyama E Neuroblastoma screening in Japan: population-based cohort study and future aspects of screening. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore 2008;37(12 Suppl):88–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maris JM, Woods WG. Screening for neuroblastoma: a resurrected idea? Lancet (London, England) 2008;371(9619):1142–3 doi 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Malkin D, Nichols KE, Schiffman JD, Plon SE, Brodeur GM. The Future of Surveillance in the Context of Cancer Predisposition: Through the Murky Looking Glass. Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2017;23(21):e133–e7 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Almannai M, Marom R, Sutton VR. Newborn screening: a review of history, recent advancements, and future perspectives in the era of next generation sequencing. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2016;28(6):694–9 doi 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pitt JJ. Newborn Screening. The Clinical Biochemist Reviews 2010;31(2):57–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Custódio G, Parise GA, Kiesel Filho N, Komechen H, Sabbaga CC, Rosati R, et al. Impact of neonatal screening and surveillance for the TP53 R337H mutation on early detection of childhood adrenocortical tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2013;31(20):2619–26 doi 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Spector LG, Ross JA, Olshan AF. Children's Oncology Group's 2013 blueprint for research: epidemiology. Pediatric blood & cancer 2013;60(6):1059–62 doi 10.1002/pbc.24434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Puumala SE, Spector LG, Robison LL, Bunin GR, Olshan AF, Linabery AM, et al. Comparability and representativeness of control groups in a case-control study of infant leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. American Journal of Epidemiology 2009;170(3):379–87 doi 10.1093/aje/kwp127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Spector LG, Ross JA, Puumala SE, Roesler M, Olshan AF, Bunin GR. Feasibility of nationwide birth registry control selection in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology 2007;166(7):852–6 doi 10.1093/aje/kwm143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoon PW, Rasmussen SA, Lynberg MC, Moore CA, Anderka M, Carmichael SL, et al. The National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Public Health Reports (Washington, DC: 1974) 2001;116 Suppl 1:32–40 doi 10.1093/phr/116.S1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang Y, Basu S, Mirabello L, Spector L, Zhang L. A Bayesian Gene-Based Genome-Wide Association Study Analysis of Osteosarcoma Trio Data Using a Hierarchically Structured Prior. Cancer Informatics 2018;17:1176935118775103- doi 10.1177/1176935118775103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mazul AL, Weinberg CR, Engel SM, Siega-Riz AM, Zou F, Carrier KS, et al. Neuroblastoma in relation to joint effects of vitamin A and maternal and offspring variants in vitamin A-related genes: A report of the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer Epidemiology 2019;61:165–71 doi 10.1016/j.canep.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Marcotte EL, Pankratz N, Amatruda JF, Frazier AL, Krailo M, Davies S, et al. Variants in BAK1, SPRY4, and GAB2 are associated with pediatric germ cell tumors: A report from the children's oncology group. Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer 2017;56(7):548–58 doi 10.1002/gcc.22457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Petrick LM, Schiffman C, Edmands WMB, Yano Y, Perttula K, Whitehead T, et al. Metabolomics of neonatal blood spots reveal distinct phenotypes of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia and potential effects of early-life nutrition. Cancer Lett 2019;452:71–8 doi 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Spector LG, Murphy SE, Wickham KM, Lindgren B, Joseph AM. Prenatal tobacco exposure and cotinine in newborn dried blood spots. Pediatrics 2014;133(6):e1632–8 doi 10.1542/peds.2013-3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Funk WE, Waidyanatha S, Chaing SH, Rappaport SM. Hemoglobin adducts of benzene oxide in neonatal and adult dried blood spots. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17(8):1896–901 doi 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Lie RT. Distinguishing the effects of maternal and offspring genes through studies of "case-parent triads". American Journal of Epidemiology 1998;148(9):893–901 doi 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Burgess S, Small DS, Thompson SG. A review of instrumental variable estimators for Mendelian randomization. Statistical methods in medical research 2017;26(5):2333–55 doi 10.1177/0962280215597579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Archer NP, Perez-Andreu V, Stoltze U, Scheurer ME, Wilkinson AV, Lin T-N, et al. Family-based exome-wide association study of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia among Hispanics confirms role of ARID5B in susceptibility. PloS One 2017;12(8):e0180488 doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0180488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gondalia R, Baldassari A, Holliday KM, Justice AE, Mendez-Giraldez R, Stewart JD, et al. Methylome-wide association study provides evidence of particulate matter air pollution-associated DNA methylation. Environ Int 2019:104723 doi 10.1016/j.envint.2019.03.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]