Abstract

The silylation of a phosphine of OsH6(PiPr3)2 is performed via net‐metathesis between Si−C(sp n ) and H−C(sp3) σ‐bonds (n=2, 3). Complex OsH6(PiPr3)2 activates the Si−H bond of Et3SiH and Ph3SiH to give OsH5(SiR3)(PiPr3)2, which yield OsH4{κ1‐P,η2‐SiH‐[iPr2PCH(Me)CH2SiR2H]}(PiPr3) and R−H (R=Et, Ph), by displacement of a silyl substituent with a methyl group of a phosphine. Such displacement is a first‐order process, with activation entropy consistent with a rate determining step occurring via a highly ordered transition state. It displays selectivity, releasing the hydrocarbon resulting from the rupture of the weakest Si‐substituent bond, when the silyl ligand bears different substituents. Accordingly, reactions of OsH6(PiPr3)2 with dimethylphenylsilane, and 1,1,1,3,5,5,5‐heptamethyltrisiloxane afford OsH5(SiR2R′)(PiPr3)2, which evolve into OsH4{κ1‐P,η2‐GeH‐[iPr2PCH(Me)CH2SiR2H]}(PiPr3) (R=Me, OSiMe3) and R′−H (R′=Ph, Me). Exchange reaction is extended to Et3GeH. The latter reacts with OsH6(PiPr3)2 to give OsH5(GeEt3)(PiPr3)2, which loses ethane to form OsH4{κ1‐P,η2‐GeH‐[iPr2PCH(Me)CH2GeEt2H]}(PiPr3).

Keywords: Germanes, Osmium, Polyhydrides, Silanes, σ-Bond Metathesis

A series of pentahydride‐silyl/germyl‐osmium(VI) derivatives was prepared. These d2‐species of a late transition metal undergo a novel metathesis reaction between non‐activated E−C(sp n ) and H−C(sp3) σ‐bonds (E=Si, Ge; n=2, 3) affording new osmium(IV) tetrahydride complexes bearing phosphino‐silane and phosphino‐germane chelate ligands.

Introduction

Metathesis reactions between single nonpolar bonds mediated by transition metal complexes are challenging transformations from a conceptual point of view, which involve elemental steps of σ‐bond activation in both substrates and subsequent cross‐coupling of the resulting fragments. They can be described in a general manner according to Equation (a) (Scheme 1). The C−H silylation with hydrosilanes is a particular type of this class of reactions [Eq. (b) in Scheme 1], [1] which displays high chemoselectivity. [2] It is mainly centered on the functionalization of C(sp2)−H bonds, [3] while the functionalization of C(sp3)−H bonds is limited to some particular cases and still remains a great challenge. [4] As far as we know, C(sp3)−H silylation by σ‐activation/cross‐coupling metathesis involving Si−C cleavage instead of Si−H rupture has not been described [Eq. (c) in Scheme 1]. This is probably because the Si−H bond activation is kinetically and thermodynamically favored with respect to the Si−C bond rupture. [5]

Scheme 1.

Metathesis reactions between σ‐bonds mediated by transition metal complexes.

The C(sp3)−H silylation by such metathesis involving Si−C cleavage needs sequencing the cleavage of the Si−C and C(sp3)−H σ‐bonds in the metal coordination sphere. The Si−C bond activation by transition metal complexes is difficult; exceptionally uncommon is the rupture of inactivated Si−C(sp3) bonds due to their high dissociation energy and low polarity. It requires strongly nucleophilic metal centers in low oxidation state. There are a few examples of oxidative additions promoted by the formation of pincer or chelating ligands [6] and cases involving strained silicon‐containing rings. [7] The simple intermolecular Si−C(sp3) oxidative addition of alkyl, alkoxy, and siloxysilanes has been only very recently achieved by Chapp and Schley, with a cationic pincer‐supported iridium system. [8] Previously, Puddephatt had observed that the protonolysis of a (trimethylsilyl)methyl‐platinum bond led to a methyl‐platinum‐(trimethylsilyl) derivative. [9] A successful access has been also the alkyl α‐elimination on a silyl ligand coordinated to unsaturated tungsten, [10] ruthenium, [11] or iridium [12] centers, to afford silylene compounds. Classical metal‐promoted C(sp3)−H bond activation takes place via M(η2‐CH) intermediates, which evolve into alkyl derivatives by oxidative addition, heterolytic cleavage, [13] or σ‐bond metathesis. [14] A different approach involves C−H addition across a metal–ligand multiple bond. Such activation has been mainly performed employing imido complexes of early metals and electrophilic Schrock‐type carbene compounds. [15] However, the 1,2‐additions of nonpolar C(sp3)−H bonds to metal‐silylenes are very rare. [16] Sekiguchi has isolated a hafnium–silylene, which undergoes cyclometallation via 1,2‐CH addition of a silylene substituent across the Hf−Si double bond, [17] whereas Tilley has observed a similar intramolecular C−H activation and addition of a flanking mesityl methyl group across a Fe−Si double bond. [18]

Polyhydrides of platinum group metals show a highly diverse reactivity, where the σ‐bond activation reactions are preponderate. [19] The d2‐hexahydride complex OsH6(PiPr3)2 (1) occupies a privileged position within this class of compounds. In addition to activation of σ‐bonds of a wide range of organic molecules, [20] including β‐lactams [21] and nucleosides, [22] it shows interesting applications in catalysis [23] and is the synthetic precursor to novel OsII and OsIV phosphorescent emitters. [24] Although its chemistry is dominated by the reactions of C−H bond activation,[ 20c , 20d , 20f , 25 ] the Si−H bond rupture mediated by this polyhydride is unexplored. Such gap in the chemistry of one of most relevant polyhydrides of the platinum group metals prompted us to study its behavior towards R3SiH and R′R2SiH silanes. During the study, we discovered that one of the alkyl phosphines of 1 is able to undergo a surprising σ‐activation/cross‐coupling metathesis, which fits to the reaction summarized by Equation (c) of Scheme 1. This paper reports about this discovery.

Results and Discussion

Complex 1 activates the Si−H bond of R3SiH silanes. Treatment of solutions of the hexahydride complex in octane, with 1.0 equiv of triethylsilane and triphenylsilane, at 65 °C, for 4 h leads to the pentahydride‐osmium(VI)‐silyl derivatives OsH5(SiR3)(PiPr3)2 (R=Et (2), Ph (3)), which are unstable in solution and evolve into OsH4{κ1‐P,η2‐SiH‐[iPr2PCH(Me)CH2SiR2H]}(PiPr3) (R=Et (4), Ph (5)). The transformation results from the displacement of one of the R substituents of the silyl ligand by a methyl group of an isopropyl substituent of a phosphine. At 90 °C, in toluene, these σ‐bond metathesis reactions [Eq. (c)] are quantitative after 6 h (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

σ‐Activation/cross‐coupling metathesis according to Equation (c) applied to R3SiH: Preparation of complexes 2–4.

The generation rates of 2 and 4 are comparable. As a consequence, the transformation of 2 into 4 starts before the formation of 2 is complete. In contrast, the generation of 3 is significantly faster than the formation of 5 and therefore intermediate 3 can be isolated as analytically pure crystals suitable for X‐ray diffraction analysis. [26] Figure 1 shows a view of its structure. The polyhedron around the metal center can be described as a dodecahedron, in agreement with the structures of OsH6P2‐species [27] and related eight‐coordinate osmium‐polyhydrides. [28] The dodecahedron is defined by two intersecting BAAB orthogonal (88(6)°) trapezoidal planes. One of them contains the atoms P(1), H(01), H(02), and H(03), whereas the other is formed by the atoms P(2), H(04), H(05), and Si. The angle between the heavy atoms lying in the same plane, P(2)‐Os‐Si, of 133.72(3)° is significantly more open than those between heavy atoms situated at different planes, P(1)‐Os‐P(2) and Si‐Os‐P(1), of 110.92(3) and 109.70(3)°, which strongly deviate of the ideal value of 90°. The classical nature of the hydride ligands was confirmed by the DFT optimized structure, which yields separations between these ligands longer than 1.80 Å. It also reveals relatively short separations between the silicon atom and the hydrides H(02) and H(05) of 2.174 and 2.123 Å, respectively, which are consistent with the existence of the denoted “secondary interactions between silicon and hydrogen atoms (SISHA)”.[ 16a , 29 ] However, Atoms in Molecules (AIM) calculations do not show any bond path running between the involved atoms. Thus, the proximity between them seems to be related to their sizes and the geometry of the complex, but not to the existence of any bonding interaction.

Figure 1.

X‐ray structure of complex 3 with 50 % probability ellipsoids. Hydrogen atoms (except hydrides) are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [deg] for the X‐ray and DFT optimized (in square brackets) structures: Os−H(01) 1.581(10) [1.662], Os−H(02) 1.582(10) [1.635], Os−H(03) 1.593(10) [1.629], Os−H(04) 1.593(10) [1.657], Os−H(05) 1.582(10) [1.638], Os−P(1) 2.3996(8) [2.448], Os−P(2) 2.3965(8) [2.442], Os−Si 2.4312(9) [2.458], Si−H(02) [2.174], Si−H(05) [2.123]; P(1)‐Os‐P(2) 110.92(3) [109.84], Si‐Os‐P(1) 109.70(3) [106.95], Si‐Os‐P(2) 133.72(3) [134.04].

The structure of 2 as well as that of 3 are not rigid in hydrocarbon solutions. The hydride ligands of these compounds are involved in thermally activated position exchange processes, even at 153 K in methylcyclohexane‐d 14. In accordance with this, their 1H‐NMR spectra at room temperature show in the high field region a triplet at −10.70 ppm (2 J H,P=6.4 Hz) for 2 and −9.67 ppm (2 J H,P=8.4 Hz) for 3. Lowering temperature of the sample leads to a broadening of the resonance. However, decoalescence is not reached. The phosphine ligands also average their positions in solution. Thus, the 31P{1H} NMR spectra contain a singlet for the inequivalent phosphines, at about 39 ppm, in the temperature range 293–153 K. A triplet (2 J Si,P≈4 Hz) close to −2 ppm in the 29Si{1H} NMR spectra is also a characteristic feature of these polyhydrides.

The presence of a silylated phosphine in 4 and 5 was confirmed by means of the X‐ray diffraction structure of 5. [26] Figure 2 gives a view of the molecule. The polyhedron around the osmium atom can be described as a pentagonal bipyramid with the phosphorus atoms of the phosphines at the apical positions (P(1)‐Os‐P(2) 157.56(2)°), whereas the hydride ligands and the Si−H bond define the base of the polyhedron. The Si−H(01) distance of 1.91(2) Å lies within the range reported for the compounds, bearing a Si−H bonding interaction, which are called “asymmetric oxidative addition products (ASOAP)”.[ 16a , 29b ] The DFT optimized structure corroborates a short Si−H(01) distance (1.847 Å) and points out a classical nature of the hydride ligands, which are separated by more than 1.85 Å. To gain information about the nature of the osmium‐hydrogen‐silicon interaction, we also performed DFT calculations using the AIM method. The complex exhibits significant Os−Si, Si−H, and H−Os interactions as revealed by the occurrence of bond critical points located between the respective atoms, which are associated with bond paths running between them. This triangular topology, which is characteristic of elongated σ‐bonds acting as 2e‐donor ligands, [30] is complemented by a ring critical point (Figure S4).

Figure 2.

X‐ray structure of complex 5 with 50 % probability ellipsoids. Hydrogen atoms (except hydrides) are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [deg] for the X‐ray and DFT optimized (in square brackets) structures: Os−H(01) 1.584(9) [1.666], Os−H(02) 1.577(9) [1.667], Os−H(03) 1.580(9) [1.674], Os−H(04) 1.592(9) [1.648], Os−H(05) 1.590(9) [1.641], Os−P(1) 2.3512(6) [2.376], Os−P(2) 2.3449(6) [2.377], Os−Si 2.4645(6) [2.512], Si−H(01) 1.91(2) [1.847]; P(1)‐Os‐P(2) 157.56(2) [164.01], Si‐Os‐P(1) 80.98(2) [80.29], Si‐Os‐P(2) 121.302(19) [115.56].

The Si−H bond of 4 and 5 does not prevent a position exchange of low activation energy between such hydrogen atom and the hydride ligands, which are as well involved in the typical movements of this class of polyhydrides in solution. Thus, their 1H‐NMR spectra, in hydrocarbons, at room temperature show only one resonance, for the five hydrogen atoms coordinated to the metal center, which appears at about −10.6 ppm as a doublet of doublets with H−P coupling constants of around 14 and 10 Hz. Although a broadening of the signal is observed upon lowering the temperature of the sample, decoalescence does not take place even at 153 K, in methylcyclohexane‐d 14. In contrast to the hydrides, the heavy atoms keep their positions in the structure. In the same temperature range, the 31P{1H} NMR spectra contain an AB spin system at 64.6 ppm (Δν=2541 Hz, J A–B=152 Hz) for 4 and 63.8 ppm (Δν=2693 Hz, J A–B=148 Hz) for 5, whereas the 29Si{1H} NMR spectra show a doublet of doublets at 26.1 ppm (2 J Si,P=18.2 and 13.9 Hz) for 4 and 18.7 ppm (2 J Si,P=19.6 and 15.5 Hz) for 5.

The formation of 2 and 3 takes place via the unsaturated species OsH4(PiPr3)2 (A in Scheme 2), which undergoes the Si−H oxidative addition of the silanes. Tetrahydride A is generated by reductive elimination of molecular hydrogen from 1 and has been trapped with pyridines, [23b] 2,6‐dimethylbenzonitrile, [31] and boranes. [30a] The coordination of the nitrogenous Lewis bases yields tetrahydride compounds of the class OsH4(PiPr3)2L, whereas the boranes afford the trihydride‐dihydroborate complexes OsH3{κ2‐H,H‐(H2BR2)}(PiPr3)2. In contrast to A, the related chloride OsH3Cl(PPh3)3 reacts with diphenylsilane to give OsH3(SiClPh2)(PPh3)3 and OsH4(SiClPh2)(SiHPh2)(PPh3)2 and with phenylsilane to afford OsH4(SiClHPh)(SiH2Ph)(PPh3)2. [32]

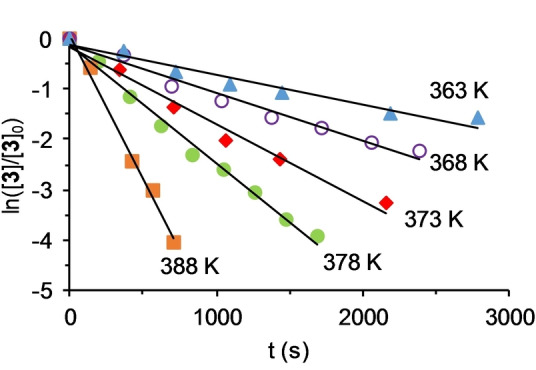

The metathesis between the σ‐bonds Si−C(sp n ) and C(sp3)−H of 2 (n=3) and 3 (n=2), to yield 4 and 5, can be rationalized as a two‐step process. The first of them should involve the reductive elimination of R−H from 2 and 3, to give tetrahydride‐osmium(IV)‐silylene intermediates OsH4(=SiR2)(PiPr3)2 (B in Scheme 2). The reaction should be seen as the reverse process of a 1,2‐addition of ethane or benzene across the Os−Si bond of a silylene and could be favored by the great number of hydrides at the metal coordination sphere. A limited number of osmium(II)‐silylene compounds has been isolated, [33] which were formed by α‐hydrogen elimination on secondary‐silyl intermediates. Once formed, the Os−Si double bond should then undergo the 1,2‐addition of a C(sp3)−H bond of a methyl group of an isopropyl substituent of one of the phosphine ligands, in the second step. To gain information about the metathesis, the conversion of 3 into 5 in toluene was followed by 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy as a function of the time, between 363 and 388 K. In this temperature range, the silylene intermediate B was not detected suggesting that, for a mechanism as that shown in Scheme 2, the release of R−H should be the rate determining step of the σ‐bond metathesis, while the addition of the C(sp3)−H bond of the phosphine across the Os−Si double bond would be fast. Figure 3 shows the spectra of the transformation at 378 K. The consumption of 3 with the corresponding increase of the amount of 5 is an exponential function of time, which can be linearized (Figure 4) as a first‐order process, according to Equation 1:

| (1) |

Figure 3.

31P{1H} NMR spectra (161.98 MHz) showing the transformation of 3 into 5 in toluene at 378 K.

Figure 4.

Plot of Equation (1) at different temperatures.

where [3]0 is the initial concentration of 3 and [3] is the concentration at time t. Values for the rate constant k in the temperature range studied are gathered in Table 1. The activation parameters obtained from the Eyring analysis (Figure 5) are ΔH ≠=22.8±3.3 kcal mol−1 and ΔS ≠=−14.2±8.8 cal K−1 mol−1, which combined give a ΔG ≠ value at 298 K of 27.1±5.9 kcal mol−1. The negative value of the activation entropy suggests an intramolecular process, which takes place via a highly ordered transition state, consistent with a direct elimination of R−H via a four‐center interaction.

Table 1.

Rate constants for the transformation of 3 into 5 at different temperatures in toluene.

|

T [K] |

[3]0 (M) |

k [s−1] |

|---|---|---|

|

363 |

0.032 |

(5.0 0.5)×10−4 |

|

368 |

0.032 |

(1.0 0.1)×10−3 |

|

373 |

0.032 |

(1.5 0.2)×10−3 |

|

378 |

0.032 |

(2.3 0.2)×10−3 |

|

388 |

0.032 |

(5.7 0.6)×10−3 |

Figure 5.

Eyring plot for the transformation of 3 into 5 in toluene.

The metathesis between σ‐bonds summarized by Equation (c) can be extended to R′R2SiH tertiary silanes bearing two different substituents. The reactions show selectivity, which is controlled by the strength of the Si‐substituent bonds, releasing the hydrocarbon resulting from the rupture of the weakest Si‐substituent bond (Scheme 3), as expected for a process kinetically controlled by such release. According to this, complex 1 reacts with dimethylphenylsilane, and 1,1,1,3,5,5,5‐heptamethyltrisiloxane to initially give the pentahydride‐osmium(VI)‐silyl complexes OsH5(SiR2R′)(PiPr3)2 (SiR2R′=SiMe2Ph (6), Si(OSiMe3)2Me (7)), which release benzene and methane to selectively and quantitatively afford the metathesis products, the osmium(IV)‐tetrahydride derivatives OsH4{κ1‐P,η2‐SiH‐[iPr2PCH(Me)CH2SiR2H]}(PiPr3) (R=Me (8), OSiMe3 (9)). NMR spectra of 6 and 7 agree well with those of 2 and 3, whereas NMR spectra of 8 and 9 resemble those of 4 and 5 (see Experimental Section in Supporting Information).

Scheme 3.

σ‐Activation/cross‐coupling metathesis according to Equation (c) extended to R'R2SiH: preparation of complexes 6–9.

Having demonstrated the generality of the σ‐ activation/cross‐coupling metathesis for silanes, we decided to investigate its extension to germanes. Treatment of solutions of 1 in toluene, at 50 °C, with 1.0 equiv of Et3GeH initially leads to complex OsH5(GeEt3)(PiPr3)2 (10), the germyl counterpart of 2, which as the latter loses ethane to give the σ‐bond metathesis product OsH4{κ1‐P,η2‐GeH‐[iPr2PCH(Me)CH2GeEt2H]}(PiPr3) (11 in Scheme 4). NMR spectra of 10 in toluene‐d 8 agree well with those of its silyl analogous compounds. Thus, the 1H spectrum at room temperature shows a hydride resonance at −10.40 (2 J H,P=9.0 Hz) ppm, which broadens as the sample temperature is lowered without undergoing decoalescence, whereas the 31P {1H} spectrum displays a singlet at 44.3 ppm. The NMR spectra of 11 in toluene‐d 8 are similar to those of 4, 5, 8, and 9. In the 1H spectrum at room temperature, the most noticeable feature is a doublet of doublets at −11.0 ppm with H−P coupling constants of 14.5 and 9.3 Hz, whereas the 31P{1H} spectrum shows the characteristic AB spin system for this class of compounds at 69.2 ppm (Δν=3148 Hz and J A–B=138 Hz).

Scheme 4.

σ‐Activation/cross‐coupling metathesis according to Equation (c) extended to Et3GeH: preparation of complexes 10 and 11.

Conclusion

This study shows the discovery of a new reaction, a metathesis between Si−C(sp n ) and H−C(sp3) σ‐bonds (n=2, 3), which has taken place on the coordination sphere of the metal center of an osmium‐polyhydride. Osmium‐hexahydride complex OsH6(PiPr3)2 reacts with R3SiH and R′R2SiH silanes to afford uncommon pentahydride‐osmium(VI)‐silyl intermediates, OsH5(SiR3)(PiPr3)2 and OsH5(SiR2R′)(PiPr3)2, which have been fully characterized. These d2‐species of a late transition metal evolve into the tetrahydride‐osmium(IV) derivatives OsH4{κ1‐P,η2‐SiH‐[iPr2PCH(Me)CH2SiR2H]}, by releasing hydrocarbons R−H and R′−H, respectively. The release of the hydrocarbon is a consequence of the displacement of one of the substituents of the silyl ligand by a methyl group of an isopropyl substituent of a phosphine. The displacement displays selectivity when the silyl ligand bears different substituents, the hydrocarbon corresponding to the Si‐substituent bond weakest from the three being released. The reaction shows generality for silanes and has been extended to germanes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (Projects PID2020‐115286GB‐I00 and RED2018‐102387‐T), Gobierno de Aragón (Group E06_20R and LMP23_21), FEDER, and the European Social Fund is gratefully acknowledged. E. R. thanks the MCIN for her FPI contract (PRE2018‐085398, “ESF investing in your future”).

In memory of Dr. Antonio Martínez

M. A. Esteruelas, A. M. López, E. Oñate, E. Raga, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202204081; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202204081.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Cheng C., Hartwig J. F., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8946–8975; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Yang Y., Wang C., Sci. China Chem. 2015, 58, 1266–1279; [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Hartwig J. F., Romero E. A., Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 4059–4070; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d. Richter S. C., Oestreich M., Trends Chem. 2020, 2, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Nakao Y., Hiyama T., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4893–4901; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Sore H. F., Galloway W. R. J. D., Spring D. R., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1845–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Ishiyama T., Sato K., Nishio Y., Miyaura N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5346–5348; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2003, 115, 5504–5506; [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Cheng C., Hartwig J. F., Science 2014, 343, 853–857; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Karmel C., Hartwig J. F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10494–10505; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Esteruelas M. A., Martínez A., Oliván M., Oñate E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 19119–19131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Pan J.-L., Li Q.-Z., Zhang T.-Y., Hou S.-H., Kangc J.-C., Zhang S.-Y., Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 13151–13154; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Su B., Lee T., Hartwig J. F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 18032–18038; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Feng J.-J., Oestreich M., Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 4273–4276; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Hirano M., Fukumoto Y., Matsubara N., Chatani N., Chem. Lett. 2018, 47, 385–388; [Google Scholar]

- 4e. Wen J., Dong B., Zhu J., Zhao Y., Shi Z., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 10909–10912; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 11001–11004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Sakaki S., Ieki M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 2373–2381; [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Schubert U., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1994, 33, 419–421; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1994, 106, 435–437; [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Sakaki S., Mizoe N., Musashi Y., Biswas B., Sugimoto M., J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 8027–8036. [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Mitton S. J., McDonald R., Turculet L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8568–8571; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 8720–8723; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Safa M., Jennings M. C., Puddephatt R. J., Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 2811–2813; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Kameo H., Ishii S., Nakazawa H., Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 4663–4669; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6d. Mitton S. J., McDonald R., Turculet L., Polyhedron 2013, 52, 750–754; [Google Scholar]

- 6e. Azpeitia S., Martínez-Martínez A. J., Garralda M. A., Weller A. S., Huertos M. A., Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 5416–5419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Li L., Zhang Y., Gao L., Song Z., Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 1466–1473; [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Wang X.-B., Zheng Z.-J., Xie J.-L., Gu X.-W., Mu Q.-C., Yin G.-W., Ye F., Xu Z., Xu L.-W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 790–797; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 800–807; [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Zhang L., An K., Wang Y., Wu Y.-D., Zhang X., Yu Z.-X., He W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3571–3582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chapp S. M., Schley N. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 5534–5539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ong C. M., Burchell T. J., Puddephatt R. J., Organometallics 2004, 23, 1493–1495. [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Begum R., Komuro T., Tobita H., Chem. Lett. 2007, 36, 650–651; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Suzuki E., Komuro T., Kanno Y., Okazaki M., Tobita H., Organometallics 2010, 29, 5296–5300. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hashimoto H., Sato J., Tobita H., Organometallics 2009, 28, 3963–3965. [Google Scholar]

- 12.

- 12a. Burger P., Bergman R. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 10462–10463; [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Klei S. R., Tilley T. D., Bergman R. G., Organometallics 2001, 20, 3220–3222; [Google Scholar]

- 12c. Klei S. R., Tilley T. D., Bergman R. G., Organometallics 2002, 21, 4648–4661. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Jones W. D., Feher F. J., Acc. Chem. Res. 1989, 22, 91–100; [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Shilov A. E., Shul'pin G. B., Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 2879–2932; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13c. Balcells D., Clot E., Eisenstein O., Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 749–823; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13d. Esteruelas M. A., Olivan M. in Applied Homogeneous Catalysis with Organometallic Compounds: A Comprehensive Handbook in Four Volumes, 3rd ed. (Eds.: Cornils B., Herrmann W. A., Beller M., Paciello R.), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2017, chap. 23; [Google Scholar]

- 13e. Eisenstein O., Milani J., Perutz R. N., Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8710–8753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Perutz R. N., Sabo-Etienne S., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2578–2592; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 2630–2645; [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Waterman R., Organometallics 2013, 32, 7249–7263. [Google Scholar]

- 15.

- 15a. Cavaliere V. N., Mindiola D. J., Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 3356; [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Wolczanski P. T., Organometallics 2018, 37, 505–516. [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Corey J. Y., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11291–11435; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Whited M. T., Taylor B. L. H., Comments Inorg. Chem. 2020, 40, 217–276. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakata N., Fujita T., Sekiguchi A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 16024–16025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith P. W., Tilley T. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3880–3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Esteruelas M. A., López A. M., Oliván M., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 8770–8847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.See for example:

- 20a. Eguillor B., Esteruelas M. A., García-Raboso J., Oliván M., Oñate E., Pastor I. M., Peñafiel I., Yus M., Organometallics 2011, 30, 1658–1667; [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Bolaño T., Esteruelas M. A., Gay M. P., Oñate E., Pastor I. M., Yus M., Organometallics 2015, 34, 3902–3908; [Google Scholar]

- 20c. Eguillor B., Esteruelas M. A., Lezáun V., Oliván M., Oñate E., Tsai J.-Y., Xia C. J., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 9106–9110; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20d. Eguillor B., Esteruelas M. A., Lezáun V., Oliván M., Oñate E., Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 1526–1530; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20e. Babón J. C., Esteruelas M. A., Fernández I., López A. M., Oñate E., Organometallics 2018, 37, 2014–2017; [Google Scholar]

- 20f. Cancela L., Esteruelas M. A., López A. M., Oliván M., Oñate E., San-Torcuato A., Vélez A., Organometallics 2020, 39, 2102–2115. [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Casarrubios L., Esteruelas M. A., Larramona C., Lledós A., Muntaner J. G., Oñate E., Ortuño M. A., Sierra M. A., Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 16781–16785; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Casarrubios L., Esteruelas M. A., Larramona C., Muntaner J. G., Oñate E., Sierra M. A., Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 10998–11006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.

- 22a. Esteruelas M. A., García-Raboso J., Oliván M., Oñate E., Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 5975–5984; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22b. Esteruelas M. A., García-Raboso J., Oliván M., Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 9522–9528; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22c. Valencia M., Merinero A. D., Lorenzo-Aparicio C., Gómez-Gallego M., Sierra M. A., Eguillor B., Esteruelas M. A., Oliván M., Oñate E., Organometallics 2020, 39, 312–323. [Google Scholar]

- 23.

- 23a. Barrio P., Esteruelas M. A., Oñate E., Organometallics 2004, 23, 1340–1348; [Google Scholar]

- 23b. Eguillor B., Esteruelas M. A., García-Raboso J., Oliván M., Oñate E., Organometallics 2009, 28, 3700–3709; [Google Scholar]

- 23c. Babón J. C., Esteruelas M. A., López A. M., Oñate E., Organometallics 2020, 39, 2177–2188; [Google Scholar]

- 23d. Babón J. C., Esteruelas M. A., Fernández I., López A. M., Oñate E., Organometallics 2020, 39, 3864–3872; [Google Scholar]

- 23e. Babón J. C., Esteruelas M. A., López A. M., Oñate E., Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 7284–7296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.

- 24a. Crespo O., Eguillor B., Esteruelas M. A., Fernández I., García-Raboso J., Gómez-Gallego M., Martín-Ortiz M., Oliván M., Sierra M. A., Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 5328–5330; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24b. Alabau R. G., Eguillor B., Esler J., Esteruelas M. A., Oliván M., Oñate E., Tsai J.-Y., Xia C., Organometallics 2014, 33, 5582–5596; [Google Scholar]

- 24c. Eguillor B., Esteruelas M. A., Fernández I., Gómez-Gallego M., Lledós A., Martín-Ortiz M., Oliván M., Oñate E., Sierra M. A., Organometallics 2015, 34, 1898–1910; [Google Scholar]

- 24d. Alabau R. G., Esteruelas M. A., Oliván M., Oñate E., Palacios A. U., Tsai J.-Y., Xia C., Organometallics 2016, 35, 3981–3995; [Google Scholar]

- 24e. Alabau R. G., Esteruelas M. A., Oliván M., Oñate E., Organometallics 2017, 36, 1848–1859; [Google Scholar]

- 24f. Castro-Rodrigo R., Esteruelas M. A., Gómez-Bautista D., Lezáun V., López A. M., Oliván M., Oñate E., Organometallics 2019, 38, 3707–3718; [Google Scholar]

- 24g. Cancela L., Esteruelas M. A., Galbán J., Oliván M., Oñate E., Vélez A., Vidal J. C., Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 2783–2796; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24h. Buil M. L., Esteruelas M. A., López A. M., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 4731–4761. [Google Scholar]

- 25.

- 25a. Esteruelas M. A., Masamunt A. B., Oliván M., Oñate E., Valencia M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 11612–11613; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25b. Esteruelas M. A., Forcén E., Oliván M., Oñate E., Organometallics 2008, 27, 6188–6192; [Google Scholar]

- 25c. Esteruelas M. A., Fernández I., Herrera A., Martín-Ortiz M., Martínez-Álvarez R., Oliván M., Oñate E., Sierra M. A., Valencia M., Organometallics 2010, 29, 976–986; [Google Scholar]

- 25d. Esteruelas M. A., Larramona C., Oñate E., Organometallics 2016, 35, 1597–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deposition Numbers 2088334 (for 3) and 2088335 (for 5) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

- 27. Howard J. A. K., Johnson O., Koetzle T. F., Spencer J. L., Inorg. Chem. 1987, 26, 2930–2933. [Google Scholar]

- 28.

- 28a. Esteruelas M. A., Lledós A., Martín M., Maseras F., Osés R., Ruiz N., Tomàs J., Organometallics 2001, 20, 5297–5309; [Google Scholar]

- 28b. Esteruelas M. A., Lledós A., Maseras F., Oliván M., Oñate E., Tajada M. A., Tomàs J., Organometallics 2003, 22, 2087–2096; [Google Scholar]

- 28c. Esteruelas M. A., Lledós A., Maresca O., Oliván M., Oñate E., Tajada M. A., Organometallics 2004, 23, 1453–1456; [Google Scholar]

- 28d. Eguillor B., Esteruelas M. A., Oliván M., Puerta M., Organometallics 2008, 27, 445–450. [Google Scholar]

- 29.

- 29a. Atheaux I., Delpech F., Donnadieu B., Sabo-Etienne S., Chaudret B., Hussein K., Barthelat J.-C., Braun T., Duckett S. B., Perutz R. N., Organometallics 2002, 21, 5347–5357; [Google Scholar]

- 29b. Nikonov G. I., Adv. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 53, 217–309. [Google Scholar]

- 30.

- 30a. Babón J. C., Esteruelas M. A., Fernández I., López A. M., Oñate E., Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 4482–4491; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30b. Esteruelas M. A., Fernández I., García-Yebra C., Martín J., Oñate E., Organometallics 2017, 36, 2298–2307. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Babón J. C., Esteruelas M. A., Fernández I., López A. M., Oñate E., Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 8673–8684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. He G., Wu L., Bai W., Chen J., Sung H. H. Y., Williams I. D., Lin Z., Jia G., Organometallics 2017, 36, 3729–3738. [Google Scholar]

- 33.See for example:

- 33a. Gusev D. G., Fontaine F.-G., Lough A. J., Zargarian D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 216–219; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2003, 115, 226–229; [Google Scholar]

- 33b. Glaser P. B., Tilley T. D., Organometallics 2004, 23, 5799–5812; [Google Scholar]

- 33c. Hayes P. G., Beddie C., Hall M. B., Waterman R., Tilley T. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 428–429; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33d. Calimano E., Tilley T. D., Organometallics 2010, 29, 1680–1692. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.