Abstract

There is an urgent need for better detection and understanding of vascular abnormalities at the micro-level, where critical vascular nourishment and cellular metabolic changes occur. This is especially the case for structures such as the midbrain where both the feeding and draining vessels are quite small. Being able to monitor and diagnose vascular changes earlier will aid in better understanding the etiology of the disease and in the development of therapeutics. In this work, thirteen healthy volunteers were scanned with a dual echo susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) sequence, with a resolution of 0.22×0.44×1mm3 at 3T. Ultra-small superparamagnetic iron oxides (USPIO) were used to induce an increase in susceptibility in both arteries and veins. Although the increased vascular susceptibility enhances the visibility of small subvoxel vessels, the accompanying strong signal loss of the large vessels deteriorates the local tissue contrast. To overcome this problem, the SWI data were acquired at different time points during a gradual administration (final concentration = 4mg/kg) of the USPIO agent, Ferumoxytol, and the data was processed to combine the SWI data dynamically, in order to see through these blooming artifacts. The major vessels and their tributaries (such as the collicular artery, peduncular artery, peduncular vein and the lateral mesencephalic vein) were identified on the combined SWI data using arterio-venous maps. Dynamically combined SWI data was then compared with previous histological work to validate that this protocol was able to detect small vessels on the order of 50μm to 100μm. A complex division-based phase unwrapping was also employed to improve the quality of quantitative susceptibility maps by reducing the artifacts due to aliased voxels at the vessel boundaries. The smallest detectable vessel size was then evaluated by revisiting numerical simulations, using estimated true susceptibilities for the basal vein and the posterior cerebral artery in the presence of Ferumoxytol. These simulations suggest that vessels as small as 50 μm should be visible with the maximum dose of 4mg/kg.

Keywords: Susceptibility Weighted Imaging, Quantitation, Visualization, midbrain

INTRODUCTION

Cerebrovascular diseases affect the circulation of blood to the brain due to abnormal vascular functional hemodynamics (Hu et al., 2017). A growing body of evidence in animal and human studies shows that micro-cerebrovascular abnormalities are the source of many neurological disorders (Desai Bradaric et al., 2012; Iadecola, 2013; Zlokovic, 2008). Although clear pathogenic mechanisms are unknown and may vary among diseases, significant microvasculature involvement has been suggested in many neurodegenerative and inflammatory diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease (PD), epilepsy, traumatic brain injury and multiple sclerosis (Zlokovic, 2008) to name a few of the major diseases. According to a recent national institutes of health (NIH) workshop, there is an urgent need for better detection and understanding of vascular abnormalities at the micro-level (Bosetti et al., 2016), where critical vascular nourishment and cellular metabolic changes occur. Being able to monitor and diagnose these vascular changes earlier in the disease process will aid in better understanding the etiology of the disease and in the development of therapeutics (Sweeney et al., 2018).

The midbrain, an area of focus in this paper, and its structures, especially the substantia nigra (SN), play a pivotal role in coordinating smooth movements (Guzman et al., 2009). It is not surprising that an ample amount of blood supply is required to meet such an energy demand (Harris et al., 2012; Hofmeijer and van Putten, 2012; Pacelli et al., 2015). It can be inferred that an insufficient blood supply could cause dopaminergic neuronal dysfunction in the SN. Therefore, it is quintessential to trace back the changes in cerebral microvasculature that manifest early in prediagnostic (preclinical and prodromal phases) and follow along ensuing development later in the clinical phase of PD (Noyce et al., 2016).

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), as it currently stands, is a powerful practical tool for imaging the major arterial (from M1 to M4) and venous (the dural sinuses and internal cerebral veins) segments. All of these vessels range in size from about 250μm to several millimeters. However, from a total volume perspective, these vessels are just a small part of the vasculature that actually feeds and drains the brain. Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) expands the ability on the venous side to image pial veins and medullary veins without the use of contrast agents (Liu et al., 2017). However, if the goal is to image arteries in vivo on the order of 50 to 100μm, then it will be very difficult, if not impossible, to do this with conventional MRA and SWI techniques. And yet it is just at this level where one may find the origin of microvascular disease.

The ability to image the very small veins with SWI without a contrast agent comes from the presence of the susceptibility differences with respect to surrounding tissues induced by the deoxyhemoglobin in the blood. Unfortunately, the arterial blood has no susceptibility difference with the background tissue and, hence, imaging arteries with conventional SWI without the use of a contrast agent has not been possible. Indeed, in previous work, the use of Ferumoxytol was introduced to induce a susceptibility in the arteries (as well as increase the susceptibility in the veins over and above that is caused by deoxyhemoglobin) (Liu et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2020). This new method may be dubbed as MICRO imaging, which stands for “Microvascular In-vivo Contrast Revealed Origins”. Among all the ultrasmall super-paramagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) particles, Ferumoxytol is the one most often used in human studies as an off-label magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent. With this USPIO-induced increase in susceptibility comes the potential to make small subvoxel vessels visible (now inclusive of arteries) without having to image at the resolution of the vessel itself. For example, without a contrast agent, small veins can be imaged by using a voxel size equal to twice the diameter of the vessel with SWI (Liu et al., 2017). This is due to both the increased dephasing/blooming artifact as well as to the special processing from SWI that uses phase-enhancing information. By increasing the susceptibility of the vessels, this ratio could be increased to perhaps a factor of four, making it possible to image 50 to 100μm diameter vessels with an imaging resolution of only 200 to 400μm on MRI. However, with this enhancement of the small vessels comes major blooming artifacts from the large vessels and so the challenge is how to collect the imaging data so that the large, medium and small vessels can all be imaged and the arteries separated from the veins. This must be accomplished by having sufficient resolution, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and speed to make it clinically viable.

In this work, we introduce a MICRO imaging protocol with the use of Ferumoxytol that enables us to image small vessels in vivo at a subvoxel level (i.e., <200μm) at 3T. Numerical simulations were performed and studied to select the best aspect ratio (testing both symmetric and asymmetric in-plane ratio) and imaging resolution in order to visualize subvoxel vessels. As a demonstration of the potential of MICRO imaging, we focused on studying the anatomy and microvasculature of the midbrain in healthy volunteers with an eye toward future work in studying vascular abnormalities in diseases such as PD. However, as mentioned above, the increase in susceptibility (in the presence of Ferumoxytol) will obscure the regions surrounding the larger vessels due to blooming artifacts. In order to overcome this problem, SWI data were acquired at different time points during the gradual administration of the Ferumoxytol making it possible to see through these blooming artifacts from large vessels by dynamically combining the post-contrast SWI data. The SWI data were used to obtain a map of major arteries and veins, which were then used to classify the smaller vessels as arterial/venous branches. A complex division-based phase unwrapping method was also employed to improve the quality of quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) by reducing the artifacts due to aliased voxels at the vessel boundaries. The smallest detectable vessel size was then evaluated by revisiting the simulations, using the estimated true susceptibilities for the basal vein (BV) and the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) in the presence of Ferumoxytol. In addition to the numerical simulations, the diameter of these small vessels was estimated by using the histological sections studied in previous literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data were acquired with an adapted three-dimensional (3D) gradient echo SWI sequence (Chen et al., 2018a) collected from a 3T MR scanner (Verio, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany), with a 32-channel head coil, before and during the administration of Ferumoxytol (Feraheme, AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Waltham, MA). The post-contrast data were acquired during a gradual increase in dose (final concentration = 4mg/kg). Thirteen healthy volunteers (n = 13, age = 33.5±13.8 years, female/male = 9/4) were scanned after obtaining approval from the institutional review board of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan and written informed consent was obtained in all cases.

Optimizing the MRI parameters

The roles of increased susceptibility and R2’ relaxation were evaluated to visualize arteries and, more specifically, to enhance the visibility of small arteries and veins using a simulation approach. From these simulations, the optimal imaging resolution was chosen to achieve the maximal SNR per unit time and maximal coverage of the brain.

For the numerical simulations, vessels were modeled as an infinite cylinder using a high resolution 2D grid (1024×1024) within which the vasculature could be mimicked at 3T, with an echo time (TE) = 15ms, a flip angle (FA) = 15°, a repetition time (TR) = 27ms and a range of 0.1 to 8mg/kg (with an interval of 0.1mg/kg) for the Ferumoxytol concentration. The dipole fields from an infinitely long cylinder, perpendicular to the main field, were used to simulate the 2D phase images (Brown et al., 2014). The region outside the vein was assumed to be white matter with a T2* = 53.2ms (Peters et al., 2007) and a T1 = 838ms (Wright et al., 2008) at 3T, for simulating the corresponding magnitude images. The T1, T2* and Δχ values of the cylinder were varied as a function of the Ferumoxytol dose (Knobloch et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018).

In order to determine the relationship between T1, T2* and Δχ with a given Ferumoxytol concentration, the total blood volume was estimated to be 3.75L assuming an average body weight of 50kg (Butterworth et al., 2018). The concentration of Ferumoxytol in blood [cFe] was calculated using [cFe] = dose × (body weight)/(blood volume) in mg/L. The T1 post-contrast was calculated from: T1 = 1/(−1.067 × ([cFe]/FeM)2 + 11.36 × ([cFe]/FeM) - 0.09) in sec, where FeM is the molar mass of iron (55.8g/mol) (Knobloch et al., 2018). The T2* was calculated from: T2* = 1/(1562 × ([cFe]/103) + 2) in sec and Δχ was calculated using Δχ = 32 × ([cFe]/103) in ppm (Liu et al., 2018). For a vein, the susceptibility value of 0.45ppm (at ~70% oxygenation) was added to that of the Ferumoxytol-induced susceptibility, to account for the deoxyhemoglobin content. The simulated images for voxel and subvoxel sized objects were generated by first finely sampling the cylinder in the image domain using a large 2D matrix size (1024×1024), where x×y represent the phase×slice dimensions. Then, the image was created by Fourier transforming the central 32×32, 32×16, 16×8 and 16×6 elements of k-space to represent the vessel aspect ratios (VAR), or the ratio of voxel size to the vessel size, of 2:2:2, 2:2:4, 2:4:8 and 2:4:10, respectively, in order to study the partial volume effects and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) (Cheng et al., 2009). Here, the frequency encoding dimension was kept constant. Thermal noise was added to simulate the SNRs of 4.2:1, 6:1, 12:1, 12:1 for 2:2:2, 2:2:4, 2:4:8 and 2:4:10, respectively. SWI images were generated by homodyne high-pass filtering (filter size=96×96) the phase images to generate a phase mask (φM), which was multiplied with the original magnitude images four times (Haacke et al., 2009). The CNR was calculated over 800 independent repetitions to reduce standard error of the mean estimates. The above steps were repeated with 4:4:4, 4:4:8, 4:8:16 to 4:8:20 VARs. Finally, CNR versus concentration was calculated for the average over two (NEX = 2) adjacent SWI datasets is presented with an SNR of 12√2:1 for the VARs of 2:4:10 and 4:8:20.

Contrast agent administration and data acquisition

All subjects were scanned with a dual echo SWI sequence at four time points: the first was acquired pre-contrast (Fe0) and the remaining three were acquired post-contrast (Fe1, Fe2 and Fe3) during a gradual increase in dose (final concentration = 4mg/kg). The Ferumoxytol dose was diluted with 60ml of 0.9% sodium chloride (or normal saline). The administration rate was selected between the range of 150–200 ml/hr, which was varied for each subject in order to consistently deliver the complete dose over a target time period of 21–23 minutes. The administration was initiated at the start of the first post-contrast sequence (Fe1) and the post-contrast scan (Fe3) began at the end of the infusion time. The blood pressure (BP) was collected before the initiation of the scanning session and within 15 minutes after scanning to monitor any signs of hypotension.

The acquisition time for each of the four sequences was 11 minutes with the imaging parameters: TE1/TE2/TR = 7.5/15/27 ms, bandwidth = 180 Hz/pxl, FOVread×FOVphase = 224×182 mm2, scanning matrix = 1024×416, number of slices = 96, slice oversampling = 8.3%, flip angle = 15o (Fe0 and Fe3) and 20o (Fe1 and Fe2); with a voxel size = 0.22×0.44×1 mm3 (reconstructed to 0.22×0.22×1 mm3). The generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) was utilized to further accelerate the data acquisition using a GRAPPA factor of 2 with central 36 reference lines.

Data post-processing

Prior to reconstructing the susceptibility maps, phase images need to be unwrapped. But as the concentration of Ferumoxytol increases and the susceptibility likewise increases, the conventional phase unwrapping fails particularly at the vessel boundaries. To overcome this problem, temporal phase unwrapping was employed by complex dividing consecutive time points (Chen et al., 2018b). Unfortunately, the process of co-registration of the images blurs the aliased voxels, making it impossible to unwrap them after registration. Hence, it is imperative to unwrap the phase completely before the registration step. Therefore, we used a ‘step-wise forward registration’ for the phase correction to prevent blurring of the aliased voxels. This was followed by a ‘backward registration’ in order to register the corrected phase to the Fe0 data. The image registration was performed using the statistical parametric mapping (SPM) package (SPM12, Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, University College London, London, UK) in MATLAB by using the normalized mutual information as the cost function and a 4th degree spline for interpolation (Ashburner and Friston, 1997; Collignon et al., 1995; Studholme et al., 1999). The transform parameters obtained from magnitude data registration were then applied to the unwrapped phase and SWI data. Data from two volunteers were not included in this study due to major motion during and between scans, leaving data from eleven healthy controls that could be analyzed.

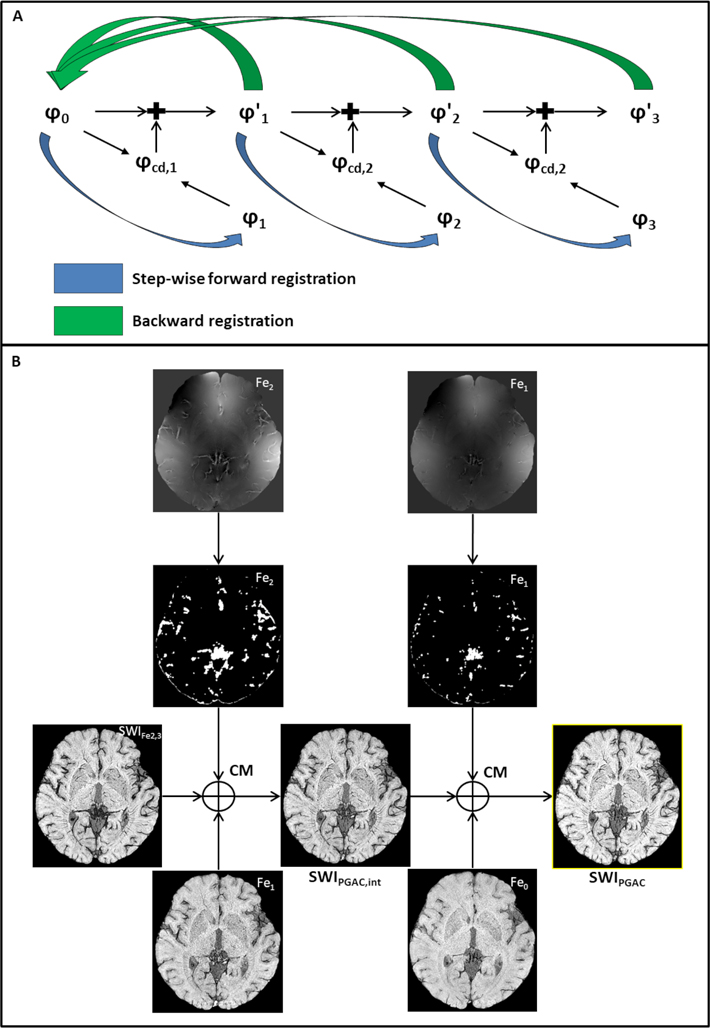

The following pipeline of registration and complex division was used: 1) the phase data from all the time points was unwrapped using the 3D best path method (Abdul-Rahman et al., 2007); 2) Fen−1 data was registered to the Fen data (or step-wise forward registration) and complex divided phase was calculated (where n = 1 to 3). The complex division was obtained using the short TE data, instead of the long TE, due to the lesser extent of unreliable signal caused by strong phase gradients that are proportional to the TE at the boundaries of the vessels; 3) The complex divided phase contained considerably fewer aliased voxels and was then added to the Fen−1 short TE phase data to obtain a corrected short TE Fen phase (referred to as φ’n). For the subsequent time points, φ’n phase data was used for this correction step; and 4) all the original magnitude and corrected phase data were registered to the Fe0 data (or backward registration). This process of correcting the aliased voxels surrounding the large vessels before registration is essential to obtain accurate QSM results. The above-mentioned registration process for modified phase unwrapping is illustrated in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Process of performing complex division-based phase unwrapping and SWI combination. (A) Illustration of the step-wise forward (blue arrows) registration, which is used to reduce the number of aliased voxels (that were remaining after conventional phase unwrapping) in the short TE phase data for post-contrast timepoints (φn, where n = 1 to 3). This was done by calculating a complex divided phase (φcd,n = φn − φn-1) between phase data from consecutive timepoints and adding it to the φn-1 data to obtain the corrected unwrapped phase (φ′n = φn-1 + φcd,n). Backward registration (green arrows) was performed by registering back all the corrected unwrapped phase (φ′n) to the Fe0 timepoint (φ0). (B) Process of reconstructing the phase gradient-based adaptively combined SWI (SWIPGAC) using the time points: Fe0, Fe1, Fe2 and Fe3. PQM = phase quality map. SWI Fe2,3 = average of SWI data at Fe2 and Fe3. The combination approach using the SWI mean, which uses the mean of the current and previous timepoint SWI data within the PQM region, was selected using numerical simulation experiments (see also Supplementary Figure S2 for more details). CM = combination method, SWIPGAC,int = intermediate SWIPGAC.

For the rest of the QSM processing, the sophisticated harmonic artifact reduction for phase data (SHARP) method was used to estimate the background field and remove it from the unwrapped phase (Schweser et al., 2011). The truncated k-space inverse filter approach with an iterative geometric constraint (also known as iSWIM) was applied to the resultant phase to generate the QSM data (Haacke et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2013). The QSM data was further refined as follows: 1) the strong phase gradients were removed from the long TE phase data using a phase quality mask (PQM) (at a threshold of Δφ > 1.8radians and dilated by a spherical kernel of radius = 5 voxels) and the resultant phase was used to obtain a QSM (QSMTE2) data set; 2) the QSM of the short TE data (QSMTE1) was generated without the use of a PQM; since at a low TE, the phase gradients were not as strong; and 3) the missing information on QSMTE2 was filled-in by applying an inverted quality mask to QSMTE1. This process reduced the aliasing artifacts surrounding the large vessels by utilizing the QSMTE1 and helped in revealing the smaller vessels hidden beneath the confounding artifacts by applying a quality mask on the long TE phase data. As mentioned above, the SWI images at each time point were generated by homodyne high-pass filtering the original long TE (15ms) phase data to obtain a φM, without any intervention from the PQM and prior to the registration process. Here, φM was generated as defined by Haacke et al. (Haacke et al., 2004) and was multiplied into the original long TE magnitude image (multiplication factor = 4). Similarly, the short and long TE magnitude (S(TE)) data were fitted to the monoexponential equation: S(TE) = ρ·e-(TE·R2*); where ρ is the intrinsic proton density of the tissues, to obtain R2* maps.

Dynamic combination of SWI data

The main advantage of acquiring multiple time points over the gradual injection of Ferumoxytol was the ability to monitor the blooming artifacts for different levels of vascular diameters. At the Fe0 time point, the large vessels (diameter ≈ 8 voxels across or 2mm) such as the BV and PCA were clearly visible, with minimal blooming artifact, but the smaller vessels could not be detected. Although these smaller vessels were revealed at the Fe3 data point, such a high dosage of Ferumoxytol caused the large vessels to appear much larger than in the pre-contrast image, hiding the confluence with the smaller connected vessels. All four time points were combined to create an ideal combined image of SWI, which was obtained by identifying and correcting the regions with strong phase gradients. The resultant SWI data will henceforth be referred to as phase gradient-based adaptively combined SWI (SWIPGAC) data. First, the TE2 magnitude data of Fe2 and Fe3 time points were averaged. This averaged data was then multiplied by the phase mask of the Fe3image (multiplication factor = 4) to obtain improved SWI data (SWIFe2,3) with higher SNR.

The signal from a homogeneous white matter region was obtained from all time points as well as the SWIFe2,3 data to determine the effects of different FAs. The difference of mean values, obtained from a homogeneous white matter region, at each time point with respect to the SWIFe2,3, data was subtracted from the Fe0, Fe1 SWI data to avoid the unwanted signal jumps and improve the quality of SWIPGAC data. In all cases, the distributions were obtained by manually contouring homogeneous regions, avoiding any hypointense structures that resembled a vessel on Fe3 SWI data. The contours were then copied to the other SWI datasets.

The regions with strong phase change were masked out on SWIFe2,3 data and were updated with that of the previous time points (first, with Fe1 SWI and then with Fe0 SWI) using a selected combination method (described in detail further below). A PQM, as defined in the previous sub-section, was used here to identify these regions with strong phase gradients (Δφ > 1.8radians) and dilated by a spherical kernel of radius = 5 voxels, starting from the long TE phase at Fe2 and then moving to the long TE phase at Fe1. This process is illustrated in Figure 1B.

The combination method for the dynamic SWI data was evaluated by applying three different methods on numerical simulations: 1) SWI substitution: direct substitution of the current SWI data by the previous timepoint data within the PQM, 2) φM substitution: the same as method 1, but instead of SWI data, the φM was substituted within the PQM. The resultant φM was then multiplied with the pre-contrast TE2 magnitude data; and 3) SWI mean combination: by using the mean of the current and previous timepoint SWI data within the PQM region. The numerical simulation involved a model of three crossing vessels, as shown in Supplementary Figure S1, which made it possible to study how well the above-mentioned methods preserved the contrast at the vessel intersections. The phase data was simulated using the forward filter (Koch et al., 2006; Salomir et al., 2003) on the susceptibility model and the magnitude data was simulated by using the tissue properties as mentioned in ‘Optimizing the MRI parameters’ sub-section. The same imaging parameters were used as the in vivo data and the range of 0 to 4mg/kg was used for simulating the Ferumoxytol concentrations. All three vessels were assumed to be veins. The original simulations were generated with a matrix size of 512×512×256 and, in order to induce Gibbs ringing, partial volume effects and signal loss, the central 32×32×16 k-space elements were cropped.

Producing MRA and MRV maps

The MICRO protocol enables multiple image sources for producing both MRA and MR venograms (MRV). For the MRV, the QSM and R2* constituted two different representations of veins. The third MRV was generated by dividing the short TE Fe1 magnitude data by the short TE Fe0 magnitude data. The T1-shortening effect of Ferumoxytol increases the signal more dramatically for the veins since the arteries already have high intensity from the time-of-flight (TOF) effect (i.e., even for the pre-contrast data). Hence, the above-mentioned division provides a venous-only map (VT1). The QSM, R2* and VT1 maps were then normalized to values between 0 and 1 and an average of these different MRV sources produced a high quality MRV, referred to as MRVavg. An MRA image was then calculated using a non-linear subtraction (MRAnl), as described by Ye et al. (Ye et al., 2013), of the long TE (S’) from the short TE (S) of the Fe0 magnitude data. This subtraction MRA is obtained via:

| (1) |

where, λ is a constant with an empirically selected value of 1.5. Due to the T2* effect, this subtraction will also enhance the veins, but to a much smaller extent than the arteries. Nevertheless, any venous enhancement was discarded by using a mask generated from MRVavg. As the TE2 data were not flow compensated, the arteries on R2* maps were also hyperintense and were later suppressed using the MRAnl data.

The MRAnl and MRVavg masks were used as overlays for the Fe3 SWI data to identify whether a newly revealed vessel was an artery or a vein. This was done by confirming the connection of a given subvoxel vessel to the large vessel over several consecutive slices by one of the authors with more than nine years of experience in analyzing MRI images, especially the SWI data. An adaptive vessel tracking method, implemented in SPIN-Research software (SpinTech Inc., Bingham Farms, MI, USA), was used to extract these smaller vessels from SWIPGAC and overlaid onto the Fe0 QSM data in order to better visualize the midbrain structures and vasculature (Jiang et al., 2005).

Comparison with histological data

Using previous histology work with vascular ink injection (Salamon, 1971), the ratio of PCA to peduncular artery (PedA) and a collicular artery (ColA) were obtained. This ratio, coupled with the true PCA diameter obtained from the in vivo data, was used to calculate a rough estimate of the true diameters of the PedA and ColA. Using the SWIPGAC data, PedA and ColA were identified for each volunteer. Similarly, another ex vivo study with methacrylate resin injection into the right internal carotid artery helped reveal deep white matter vessels under the scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Nonaka et al., 2003). The distance (from the ventricular angle, adjacent to the frontal horn of the lateral ventricles) and the diameter of the deep white matter vessels were measured from the SEM image. This distance was compared with the SWIPGAC data in the same region to obtain an estimate of the vessel size in that region.

Revisiting the numerical simulations

Quantitative values of susceptibility (Δχ) were obtained for large vessels (namely the BV and PCA) at each time point in order to assess the effect of Ferumoxytol. As the concentration of Ferumoxytol increases, the apparent volume of a given vessel increases due to the signal loss surrounding the vessel. This, in turn, causes the apparent Δχ (Δχapp) to be under-estimated, since the magnetic moment, which is proportional to the product of Δχ and the vessel volume (V) remains invariant. Hence, if the true volume (Vtrue) is known, the true susceptibility (Δχtrue) of a vessel can be calculated as:

| (2) |

where Vtrue was obtained by measuring the diameter (dtrue) for PCA and basal vein from the MRAnl and Fe0 QSM data, respectively. The apparent diameters (dapp) of these vessels were obtained from the short TE magnitude data at each post-contrast time point by measuring the number of voxels across the vessel that were outside the ±3σ range, where σ is the noise level of the image, measured within a homogeneous white matter region. The estimate for the true susceptibility is given by:

| (3) |

Here, Δχapp was obtained for each time point using the MRVavg and MRAnl masks of the basal vein and PCA and manually correcting these masks to avoid any region that has remnant unreliable phase change and to avoid misalignment between subsequent time points remaining even after image registration. Once Δχtrue was estimated for each post-contrast time point, the simulations were performed, as described above, using a high grid matrix of 1024×1024 and then collapsed to a 16×6 matrix, where x×y represents phase encoding × slice thickness, to obtain a VAR of 4:8:20. These simulated results helped validate whether one-fourth of a voxel-sized vessel could be visualized, especially using the Δχtrue values obtained from our cohort.

Statistical analysis

For the numerical simulations, the CNR values, represented by mean ± standard deviation of the mean (σM), were calculated over 800 independent repetitions and were compared with the Rose criterion (CNR > 3:1) to determine whether the simulated vessel would be detectable using the SWI data at a given dosage and imaging resolution. For each subject, using the BP values that were collected before and after the dose delivery, hypotension was defined as a decrease in systolic BP of >20 mmHg, or a decrease in diastolic BP of >15 mmHg (Lu et al., 2010). A paired t-test was used to compare the systolic and diastolic BP values that were acquired before and after Ferumoxytol delivery (statistical significance was set at p<0.05).

The homogeneous white matter signal distributions, obtained from each time point SWI data as well as SWIFe2,3 data, were compared using the one-way analysis of variance and the Tukey’s honestly significant difference procedure for multiple comparisons (statistical significance was set at p<0.05) (Brillinger, 2002; Hochberg and Tamhane, 1987; Searle et al., 1980). After the intensity correction, the white matter distribution was obtained from three different regions and the same tests were applied.

Finally, Δχapp and dapp measurements were summarized as mean and standard error. The profiles of the SWI signal across the large and subvoxel vessels, from all time points, were compared using the root-mean-squared-error (RMSE). For large vessels, Fe0 SWI was used as the reference for Fe1, Fe2, Fe3 SWI and SWIPGAC. Practically, the Fe0 SWI will contain the least blooming artifact surrounding the large vessels and, therefore, will be closest to the true shape and size of the given vessel. Similarly, for the subvoxel vessels (or the vessels which are invisible on Fe0 data), Fe3 SWI was used as a reference, since the Ferumoxytol content will be highest at Fe3 and will induce maximum contrast between the vessel and the surrounding tissue.

RESULTS

Based on the simulation results (Figure 2), the aspect ratio of 1:2:5 (or a VAR of 2:4:10 or 4:8:20) was selected because of: 1) the high CNR between the vessel and the surrounding tissue and 2) the extended brain coverage it offers in the slice-select direction. Therefore, the voxel resolution of 0.22×0.44×1mm3 was selected over other options such as 0.22×0.22×0.44mm3, 0.22×0.22×0.88mm3 and 0.22×0.44×0.88mm3. The acquired 0.22×0.44×1mm3 resolution data was then interpolated by zero filling in k-space along the phase-encode direction to achieve the pseudo-resolution of 0.22×0.22×1mm3. For the vessels on the order of ≈50μm, the trends show a linear increase in CNR for 4:8:16 and 4:8:20. However, with a VAR of 4:8:20 (or an imaging resolution of 0.22×0.44×1mm3 to visualize 50μm-sized vessels), the CNR did not cross the Rose criterion threshold using the estimated Δχ. On the other hand, when NEX = 2 is considered, representing the SWIFe2,3 dataset, the CNR improves significantly for VARs of 2:4:10 and 4:8:20, providing the best-case scenario compared to other VARs for detecting the 50μm-100μm vessels with the proposed voxel resolution of 0.22×0.44×1mm3.

Figure 2.

Simulations for a vein and an artery (at TE = 15ms, B0 = 3T) comparing CNR as a function of Ferumoxytol dose for different vessel aspect ratios (VAR). The values with error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation of the mean, calculated over 800 repetitions. VAR is the aspect ratio of a voxel with respect to the vessel size. The horizontal dotted line (CNR = 3) represents a threshold for detectable vessels based on the Rose criterion. VARs of 2:4:8 and 2:4:10 (frequency:phase:slice) provided the best CNR especially for doses higher than roughly 1.5 mg/kg. SNR used in each case was 4.2:1, 6:1, 12:1, 12:1 for VARs of 2:2:2, 2:2:4, 2:4:8 and 2:4:10 (top row) and, similarly, for VARs of 4:4:4, 4:4:8, 4:8:16 and 4:8:20 (bottom row), respectively. A plot of CNR versus concentration for the average over two (NEX = 2) adjacent SWI datasets is presented with an SNR of 12√2:1 for the VARs of 2:4:10 and 4:8:20. For the vein simulations, the susceptibility induced by the normal venous oxygenation level (Δχ = 0.45ppm at ~70% oxygenation) was added to the overall susceptibility at all Ferumoxytol concentrations. The difference between the venous and arterial simulation trends is mainly observed between the Ferumoxytol doses of 0.5–2.5mg/kg in the top row, where the venous CNR increases faster than that of the arterial case due to the susceptibility difference. If a voxel is (200 μm)3 in size, then a VAR = 2:2:2 represents a 100 μm vessel and a VAR = 4:4:4 represents a 50 μm vessel.

We did not observe any drastic change in BP values that would indicate Ferumoxytol-induced hypotension (Supplementary Table S1). The difference in systolic and diastolic pressures due to Ferumoxytol injection was not statistically significant (p>0.05) for our study population. The SNR, obtained from a homogeneous white matter region, of the original magnitude at Fe0 was 15:1 for short TE and 12:1 for long TE. The comparisons of the signal distributions for Fe0, Fe1 SWI data and SWIFe2,3 showed that the mean of the white matter region for Fe0 SWI data (209.9) was significantly different (p<0.05) than in the Fe1 (189.9), Fe2 (187.5), Fe3 (195.6) and SWIFe2,3 (191.4) data. In order to reduce any discontinuities in SWIPGAC data, the difference of the mean distribution values for Fe0 and Fe1 SWI data, with respect to SWIFe2,3 data, were obtained and were subtracted from the Fe0 and Fe1 SWI data. After this intensity correction, the distributions from three different homogeneous white matter regions were compared and none of the data had means significantly different than the other (p>0.05). Although this step of intensity correction will most likely be required only when the datasets are acquired with different imaging parameters (such as with different FAs), the presence of Ferumoxytol could induce an overall signal loss in white and grey matter for post-contrast data even with the same FAs. This signal loss could be utilized to obtain capillary density measurements. Supplementary Figure S1 demonstrates the reconstruction results of the three combination methods for SWIPGAC process. The SWI mean combination method was selected over SWI substitution and φM substitution methods as it was able to preserve the contrast of the smaller vein passing between the two parallel veins (red arrows in Supplementary Figure S1).

An example of Fe0 to Fe3 SWI data (Figure 3) shows gradual enhancement of subvoxel mid-brain vasculature. Ferumoxytol at 4mg/kg in Fe3 provided much better visualization of the smaller vessels. However, signal around the larger vessels was exacerbated due to the high susceptibility of the Ferumoxytol content (Figure 4C). On the other hand, the SWIPGAC provided better delineation of the larger vessels and preserved the visibility of the smaller or subvoxel vessels (Figures 4C and 4D). For the profile across the large vessels, SWIPGAC data exhibited the lowest RMSE value of 11.4 as compared with 79.4 for Fe3 SWI. Similarly, for small vessels, the RMSE was lowest for SWIPGAC (10.1) as compared with Fe0 (70.1), Fe1 (49.1) and Fe2 (30.3).

Figure 3.

Revealing the microvasculature of the midbrain using Ferumoxytol. (A) Pre-contrast (Fe0), post-contrast SWI data (Fe1, Fe2, Fe3) as well as the SWIPGAC are shown in the top row, whereas the bottom row shows their corresponding zoomed insets, focusing on the midbrain region. Each post-contrast data, starting from Fe1, was acquired at an interval of 11mins, increasing the dose at a steady rate (rate=150–200ml/hr, final concentration=4mg/kg). The post-contrast data revealed the mid-brain vasculature, which was not visible on the pre-contrast (Fe0) data. SWIPGAC was generated using the process illustrated in Figure 1, which reduced the signal loss surrounding the vessels; making it possible to obtain their true size (arrows), as shown in (B). All images were minimum intensity projected (mIP) over 8 sliceswith an effective slice thickness of 8mm.

Figure 4.

Comparing the signal behavior surrounding the large (A) and small (B) vessels on pre-contrast (Fe0), post-contrast (Fe1, Fe2, Fe3) as well as the SWIPGAC data. The profile plot in (C), averaged along the four white lines in (A), compares the signal around two neighboring large vessels for Fe0, Fe3 and SWIPGAC data, showing that Fe3 was not able to separate the two vessels due to the strong extravascular phase gradient. The profile plot in (D), averaged along the four black lines as shown on the zoomed inset in (B), demonstrates the ability to visualize the smaller vessels. These vessels were only visible on the SWIPGAC and Fe3.

Supplementary Figure S2 shows the advantage of dynamically acquiring the post-contrast data, where the low levels of Ferumoxytol in the blood makes the intravascular signal hyperintense. The arteries possess identical signal on both Fe0 and Fe1 data since the TOF effect pre-contrast is equivalent to the T1-shortening effect of the Ferumoxytol at Fe1 (≈11mins post beginning the injection). Hence, the division of Fe1 by Fe0 from short TE data suppressed the background tissues as well as the arteries. Additionally, an arterial mask (MRAnl) was generated by the non-linear subtraction given in Equation 1 and shown in Supplementary Figure S3. Finally, an improved MRVavg image (Supplementary Figure S4D) was produced by averaging the venous mask generated in Supplementary Figure S2 with the normalized R2* (Supplementary Figure S4B) and Fe0 QSM (Supplementary Figure S4C).

The MRAnl and MRVavg vessel masks helped visualize the major arteries and draining veins of the midbrain, whereas the QSM and SWIPGAC data provided a clear picture of the various anatomical structures (Figure 5). The Fe0 QSM data provided susceptibility-based contrast for structures such as the SN, red nucleus and inferior colliculus (Figure 5A). The vasculature of the midbrain (including the MRAnl (red), MRVavg (blue) and tracked smaller vessels (green)) were overlaid on the Fe0 QSM data (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Identifying the various structures of the midbrain using (A) Fe0 QSM and (B) SWIPGAC data for one selected participant. The red and blue overlays in (B) represent the MRAnl (arteries) and MRVavg (veins) masks. (C) Fe0 QSM, with the MRAnl (red) and MRVavg (blue) overlays. An adaptive vessel tracking algorithm was used to track the small vessels (green in C). SN = substantia nigra, RN = red nucleus, IC = inferior colliculus.

Another advantage of the MRAnl and MRVavg overlays was the ability to classify smaller vessels into an arterial or a venous branch (Figure 6). Based on the MRAnl overlay, the major brainstem arteries such as the anterior choriodal artery, inferior medial mesencephalic artery, medial hippocampal artery, posterior cerebral artery, posterior choroidal artery, posterior communicating artery, posterior hippocampal artery, posterior-medial choriodal artery and superior cerebral artery were identified. Similarly, based on the MRVavg overlay, the major draining veins of the brainstem such as the basal vein, inferior ventricular vein, interpeduncular vein, vein of Galen were identified. As an example, the PedA and ColA as well as the peduncular vein (PedV) and a branch of the lateral mesencephalic vein (LMV) were identified on the SWIPGAC data by finding their connections with these overlays in the midbrain region. Minimum intensity projections (mIP) of SWI images with different effective thickness (3mm, 6mm and 9mm) were used to find and confirm the connections of the small vessels to the large ones. The in vivo SWIPGAC data and the histological data with vascular ink injection, which illustrated small arteries in the midbrain, are shown in Figure 7. SWIPGAC data shows both arteries and veins due to the presence of Ferumoxytol. Based on the steps shown in Figure 6, PedA and ColA were classified and are identified by yellow and blue arrows, respectively, in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Mapping the connectivity of the large vessels to the subvoxel level using the overlays of the MRVavg and MRAnl maps on SWIPGAC data in the mid-brain. The SWIPGAC data, with the overlays, provided an initial condition to map: (1a) the collicular artery (ColA); (2a) peduncular artery (PedA); (1v) peduncular vein (PedV) and (2v) branch of the lateral mesencephalic vein (LMV), arising from the large arteries. The SWI data was minimum intensity projected over 3mm, 6mm and 12mm to visualize and confirm the connectivity. Major brainstem arteries: AChA = anterior choriodal artery, IMA = inferior medial mesencephalic artery, MHA = medial hippocampal artery, PCA = posterior cerebral artery, PChA = posterior choroidal artery, PComA = posterior communicating artery, PHA = posterior hippocampal artery, PmChA = posterior-medial choriodal artery, SCA = superior cerebral artery. Major brainstem veins: BV = basal vein, IVV = inferior ventricular vein, IPV = interpeduncular vein, VofG = vein of Galen.

Figure 7.

SWIPGAC data of eight different healthy subjects (A-D, F-I) focusing on the midbrain region. All images were minimum intensity projected (mIP) with an effective slice thickness of 8mm. The center image (E) was adapted from Figure 101 of the histology work by Salamon (Salamon, 1971). This histology work is also available online at Salamon’s Neuroanatomy and Neurovasculature Web-Atlas Resource: athttp://www.radnet.ucla.edu/sections/DINR/index.htm. The yellow and blue arrows identify PedA and ColA, respectively. Both vessels were clearly visible in all subjects.

The vessel diameter ratio from histology was calculated to be 7:1 and 18:1 for PCA:PedA and PCA: ColA, respectively (Figure 8A). From the in vivo data, the diameter of the PCA was measured to be 1.96±0.15mm across all subjects (Figure 8B). Based on the histology ratios and the in vivo PCA diameter, the estimated size of PedA and ColA were 280μm and 108μm. Furthermore, another validation was performed in the region near the frontal horn of the lateral ventricles, where the SWIPGAC data were compared with a panoramic SEM image (Figure 8 in (Nonaka et al., 2003)). Using the SEM, the diameter of the deep white matter vessels (4.7mm from the ventricular angle) was measured to be 46μm. From the ventricular angle, the medullary veins even as far as 16mm from the ventricular angle were clearly visible on the SWIPGAC data (Figure 8C), validating that the MICRO protocol was able to image vessels at the level of ~50μm.

Figure 8.

Validating the size of the small vessels that were visible after Ferumoxytol administration. (A) The ratio of posterior cerebral artery (PCA) to a peduncular artery (PedA) and collicular artery (ColA) was estimated using the histology work (adapted from Figure 101 in Salamon, 1971) by obtaining the vessel diameters at five different locations, as shown in the green boxes. (B) The true diameter of PCA was also obtained from Fe0 short TE magnitude data for all subjects. The vessel diameter ratio from the histology photograph was calculated to be 7:1 and 18:1 for PCA:PedA and PCA:ColA, respectively. (C) SWIPGAC data (with a zoomed inset of the medullary veins as shown by the white box), focusing on the cerebral white matter vessels. In the presence of 4mg/kg Ferumoxytol, the vessels as far as 16mm from the ventricular angle were visible on the SWIPGAC data. VA = Ventricular angle.

The QSM results were improved by unaliasing the voxels at the vessel boundaries (Supplementary Figure S5). The change in volume of a vessel was determined by measuring the diameter of the vessel on the post-contrast short TE magnitude data and comparing it with Fe0 QSM for BV and MRAnl for PCA (Figure 9). The mean and inter-subject variability of the Δχapp values acquired at Fe0, Fe1, Fe2 and Fe3 for the BV were 400±48 ppb, 597±131 ppb, 939±90 ppb and 1138±147 ppb, respectively. Similarly, Δχapp values acquired at Fe0, Fe1, Fe2 and Fe3 for the PCA were −19±36 ppb, 290±123 ppb, 746±73 ppb and 925±65 ppb, respectively. Based on the dapp value for each subject (Supplementary Table S2), the Δχtrue for each post-contrast time point were obtained (Supplementary Table S2). At a dosage of 4mg/kg of Ferumoxytol, the Δχtrue was estimated as 2340 ppb for the BV and 2157 ppb for the PCA (Figure 9 and Table S1). These calculated Δχtrue values were found to be higher than the estimated values (2156 ppb for veins and 1706 ppb for arteries as derived from Liu et al. 2018) that were used for initial simulation tests. Using the calculated Δχtrue, the numerical simulations were revisited using the VAR of 4:8:20 and we found that CNR exceeded the Rose criterion, for SWIFe2,3 data (NEX = 2), to detect the vessels as small as one-fourth the size of a voxel, which corresponds to roughly 50μm based on the imaging resolution undertaken in this study (Supplementary Figure S6).

Figure 9.

Determination of the true diameter (dtrue) and apparent diameter (dapp) for (A) the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and (B) the basal vein (BV). The post-contrast short TE magnitude (Mag) data (Fe1 to Fe3) show the increasing signal loss surrounding the vessels due to the presence of Ferumoxytol. MRAnl and Fe0 QSM were used to obtain the dtrue for PCA and BV, respectively. The diameters were measured by drawing a profile across the vessels, as shown by the red line in the images. The mean Δχapp (black markers) at each time point increased with the increase in Ferumoxytol dose for both (C) the PCA and (D) BV. The error bars represent the standard deviation of Δχapp for each subject. The red dots represent the Δχtrue value of blood at each time point derived from Eq. (3) based on the volume change.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this work, we demonstrated the utility of low dose Ferumoxytol in imaging the microvasculature of the midbrain. For large vessels, the high quality MRAnl and MRVavg maps were generated to help classify the smaller vessels into an artery or a vein. The SWIPGAC data helped in revealing the underlying microvasculature and, at the same time, reduced the confounding signal loss surrounding the major vessels. On the quantitative front, the step-wise forward registration was used to unwrap the post-contrast phase data by employing complex division; which in turn improved the quality of the QSM data and reduced the artifacts caused by the aliased voxels (Supplementary Figure S5). QSM data also provided a unique contrast for various structures of the midbrain based on their susceptibility distributions (Figure 5). Using the property of magnetic moment, the change in vessel diameter, caused by signal loss in the presence of Ferumoxytol, was used to calculate the Δχtrue for BV and PCA at all post-contrast time points. The numerical simulations generated Δχtrue values and the previous histological studies (Figure 8) helped validate that, with a dose as low as 4mg/kg, one can image vessels on the order of 50μm to 100μm using the proposed MICRO imaging protocol.

Mapping the vasculature of the brain has immediate implications for understanding the etiology of many neurovascular and neurodegenerative diseases such as PD. It is thought that the loss of dopamine-producing cells of the SN could be related to a hypoxic state brought on by reduced flow and potentially small vessel abnormalities (Guan et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2015). Of course, this vascular hypothesis has not yet been fully validated in PD, but our findings can provide a useful methodology for testing this vascular hypothesis.

MRI has the potential to be the technical choice for investigating the small vessels due to its non-invasive nature and its superb anatomical imaging for differentiating various tissues in the brain, including the level of oxygenation in a blood vessel (Buch et al., 2018, 2016; Haacke et al., 2015, 2010). However, with conventional MRI, there is a limit to the available voxel resolution based on the SNR of the image. SWI is a powerful tool to image the subvoxel veins. However, it is insensitive to arteries in their natural form due to the low level of deoxygenated hemoglobin in arterial blood, which results in no susceptibility contrast with respect to the surrounding tissue. These shortcomings can be circumvented by Ferumoxytol enhanced MRI, such as the MICRO imaging approach discussed herein. By administering a strongly paramagnetic agent, Ferumoxytol, SWI was able to detect both arteries and veins in the same sensitivity; and its sensitivity to detect subvoxel objects increased tremendously.

In order to visualize and determine whether each of these small vessels is a vein or an artery, high quality MRAnl and MRVavg were obtained for the major arteries and veins from the pre-contrast data. The overlays of MRVavg and MRAnl helped in tracking the smaller tributaries of the major vessels. Studying these smaller vessels and propagating their link with the larger source vessel is key for determining where the problem lies for patients with abnormal vasculature. However, great caution must be used in distinguishing arteries from veins in this way, and numerous errors of interpretation are possible if the vessels are not followed from the boundary of the midbrain, as shown in Figure 6.

The Δχapp also shows a strong increase for the Fe1 timepoint (roughly twice for Fe1 from Fe0), as compared to the subsequent post-contrast timepoints. Although this sharp increase was expected due to the presence of Ferumoxytol, the blooming artifacts for Fe2 and Fe3 timepoints caused the underestimation of the susceptibility measurements due to the preservation of magnetic moment (as explained earlier in the ‘Revisiting the numerical simulations’ sub-section). As seen in Figure 9, the Δχtrue value for Fe1 timepoint was very similar to the Δχapp value, but Δχtrue was much higher than Δχapp for later timepoints, confirming the role of blooming artifacts. In order to reduce the effect of partial volume on measuring the apparent and true values of the vessel volume, only a vessel with diameter greater than or equal to 6 voxels was chosen to obtain Δχapp. The vessel was then extracted from the MRAnl and MRVavg maps by selecting the segments that were not surrounded by other detectable vessels for a distance of 6 voxels. Any presence of a nearby vessel could overestimate the measured volume due to overlapping loss of signal at the vessel boundaries.

Some of the limitations of this study include limited resolution, requirement of Ferumoxytol administration and misalignment of vessels for different scans. It is possible to acquire the data with a higher voxel resolution. However, due to smaller voxel size and, consequently, the need for a higher bandwidth, SNR will be reduced to a point where the CNR will drop dramatically. With strong blooming effects, Ferumoxytol enhanced SWI can circumvent both insufficient spatial resolution and insufficient contrast for very small arterial and venous vessels, thus offering the capability of practically imaging micro-vessels.

The Ferumoxytol dose used in this study (4mg/kg) is a fraction of the usual dose used to treat patients with anemia. Since the rapid injection of Ferumoxytol is not recommended by the FDA (https://www.fda.gov/media/91415/download) to reduce the risk of any adverse reactions, the proposed protocol takes advantage of the gradual injection (over 21–23 mins) by acquiring multiple timepoints of high resolution SWI data. With this low dose and slow injection rate, the post-contrast SWI was able to reveal numerous smaller vessels in the mid brain. One of the known side effects of administering Ferumoxytol is hypotension (Lu et al., 2010). As seen in supplementary table S1, both systolic and diastolic BPs do not show significant changes after the injection of Ferumoxytol over a long scanning session. A possible reason for not seeing any hypotensive changes for this study is the use of low dose and gradual delivery.

Even a small amount of movement between scans or during scanning can deteriorate the temporal comparison of increasing Ferumoxytol content. The image registration mitigates this issue to some extent, but fails in exactly matching the location of the small vessels. For this reason, the registered data for each volunteer was manually examined in order to confirm that the time points were registered adequately to perform the complex divisions. In the end, only two volunteers’ data could not be evaluated because of severe motion and poor image quality.

Another important consideration was to assume that there were no changes between antemortem and postmortem states of the cerebral vasculature. It is known that in the postmortem state, the arterial smooth muscle relaxation and contractility change relative to their in vivo state (Onoue et al., 1993; Patel and Janicki, 1970). This change could have an impact on diameter measurements performed on micro-angiograms, since the dynamic pressure being imposed on the vessel walls is absent. However, we predict that such errors will be minimal for smaller vessels (<100 μm), as there is a lack of significant elastic tissue in their walls (Baker, 1937; Tucker and Mahajan, 2020). In addition, the histological work by Salamon et al, which was used for comparison in this work, does inhibit these changes and other artefacts related to postmortem preparation by injecting the radiopaque injection gradually with the simultaneous gelatin injection to preserve the shape of the vessels and prevent the leakage. The deformation was avoided by placing the cadaver brain slices in a mold on which the cerebral hemispheres rested, in order to reduce the shrinkage of cerebral tissue. Nevertheless, there may still be remnant changes in vascular diameter that cannot be confidently addressed in this work, such as the involvement of the vessel wall in the diameter measurements due to the absence of contrast between the intraluminal space and the vessel wall. In addition, the inter-subject variation in the postmortem vessel size could not be ascertained from the histology work by Salamon et al. Therefore, the numerical simulations based on the previous work (Figure 2) and the data-driven values for Δχtrue were calculated, in order to avoid these unwanted errors related to comparing with postmortem data. These simulations helped in confirming the detectability of 50μm-sized vessels, as shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S6.

With the help of the proposed MICRO protocol, the subvoxel vascular network can be enhanced at a very high spatial resolution. This will enable the identification of abnormal vasculature throughout the brain in the future and particularly in areas with white matter hyperintensities, which are present in diseases such as multiple sclerosis, dementia, stroke and PD to name a few. Similarly, perfusion weighted imaging and QSM data can be used to assess local cerebral blood flow and oxygenation levels, respectively, especially in areas with reduced vasculature.

In summary, with MICRO imaging, it was possible to image the subvoxel vasculature of the midbrain. With the proposed SWIPGAC method, the SWI data was improved significantly by reducing the confounding signal loss arising from strong susceptibility structures. Consequently, this approach could be used to study the vasculature of many other important structures such as the hippocampus or basal ganglia and its role in the etiology of different neurological diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank our MRI technician, Zahid Latif, for his efforts in collecting and organizing the data. The authors would also like to thank the participants that volunteered for this study. The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this report are those of the author(s) and should not be construed as an official government position, policy or decision unless so designated by other documentation.

Funding sources:

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant number: R56-AG060822, R01-NS108491, R01-NS108463, RF1-NS110041 and R01-AG057494).

Footnotes

Competing interests:

The authors report no competing interest.

REFERENCES:

- Abdul-Rahman HS, Gdeisat MA, Burton DR, Lalor MJ, Lilley F, Moore CJ, 2007. Fast and robust three-dimensional best path phase unwrapping algorithm. Appl. Opt., AO 46, 6623–6635. 10.1364/AO.46.006623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Friston K, 1997. Multimodal image coregistration and partitioning--a unified framework. Neuroimage 6, 209–217. 10.1006/nimg.1997.0290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AB, 1937. Structure of the Small Cerebral Arteries and their Changes with Age. Am J Pathol 13, 453–462.1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti F, Galis ZS, Bynoe MS, Charette M, Cipolla MJ, del Zoppo GJ, Gould D, Hatsukami TS, Jones TLZ, Koenig JI, Lutty GA, Maric Bilkan C, Stevens T, Tolunay HE, Koroshetz W, Agalliu D, Antonetti DA, Boehm M, Brooks CE, Caron KM, Chilian W, Daemen MJ, D’Amato R, Davis TP, Ergul A, Faber JE, Gomez AR, Grayson P, Grumbach I, Grutzendler J, Gu C, Gutterman D, Hallenbeck J, Herman I, Humphrey J, Iadecola C, Inscho EW, Kleinfeld D, Lo EH, Lopez JA, Macknik S, Malik A, Mayadas TN, McGavern D, Meininger GA, Miller VM, Nedergaard M, Nelson MT, Peirce Cottler S, Ramadan I, Rosenberg GA, Schiffrin EL, Searson P, Stachenfeld N, Stan RV, Suarez Y, Ubogu EE, Vexler ZS, Weyand CM, Zlokovic BV, 2016. “Small Blood Vessels: Big Health Problems?”: Scientific Recommendations of the National Institutes of Health Workshop. J Am Heart Assoc 5. 10.1161/JAHA.116.004389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brillinger DR, 2002. John W. Tukey: his life and professional contributions. Ann. Statist. 30, 1535–1575. 10.1214/aos/1043351246 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RW, Cheng Y-CN, Haacke EM, Thompson MR, Venkatesan R, 2014. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Physical Principles and Sequence Design, 2nd ed. Wiley, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Buch S, Chen Y, Ghassaban K, Haacke EM, 2018. T2*: Susceptibility Weighted Imaging and Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping, in: Cercignani M, Dowell NG, Tofts PS (Eds.), Quantitative MRI of the Brain. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 97–110. 10.1201/b21837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buch S, Ye Y, Haacke EM, 2016. Quantifying the changes in oxygen extraction fraction and cerebral activity caused by caffeine and acetazolamide. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 10.1177/0271678X16641129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth JF, Mackey DC, Wasnick JD, 2018. Morgan and Mikhail’s Clinical Anesthesiology. McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Liu S, Buch S, Hu J, Kang Y, Haacke EM, 2018a. An interleaved sequence for simultaneous magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) and quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM). Magn Reson Imaging 47, 1–6. 10.1016/j.mri.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Liu S, Kang Y, Haacke EM, 2018b. A rapid, robust multi-echo phase unwrapping method for quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) using strategically acquired gradient echo (STAGE) data acquisition, in: Medical Imaging 2018: Physics of Medical Imaging. Presented at the Medical Imaging 2018: Physics of Medical Imaging, International Society for Optics and Photonics, p. 105732U. 10.1117/12.2292951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y-CN, Neelavalli J, Haacke EM, 2009. Limitations of calculating field distributions and magnetic susceptibilities in MRI using a Fourier based method. Phys Med Biol 54, 1169–1189. 10.1088/0031-9155/54/5/005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon A, Maes F, Delaere D, Vandermeulen D, Suetens P, Marchal G, 1995. Automated multi-modality image registration based on information theory. In: Bizais. [Google Scholar]

- Desai Bradaric B, Patel A, Schneider JA, Carvey PM, Hendey B, 2012. Evidence for angiogenesis in Parkinson’s disease, incidental Lewy body disease, and progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 119, 59–71. 10.1007/s00702-011-0684-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J, Pavlovic D, Dalkie N, Waldvogel HJ, O’Carroll SJ, Green CR, Nicholson LFB, 2013. Vascular degeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Pathol. 23, 154–164. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2012.00628.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman JN, Sánchez-Padilla J, Chan CS, Surmeier DJ, 2009. Robust pacemaking in substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 29, 11011–11019. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2519-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke E, Mittal S, Wu Z, Neelavalli J, Cheng Y-CN, 2009. Susceptibility-weighted imaging: technical aspects and clinical applications, part 1. Am J Neuroradiol 30, 19–30. 10.3174/ajnr.A1400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke EM, Liu S, Buch S, Zheng W, Wu D, Ye Y, 2015. Quantitative susceptibility mapping: current status and future directions. Magn Reson Imaging 33, 1–25. 10.1016/j.mri.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke EM, Tang J, Neelavalli J, Cheng YCN, 2010. Susceptibility mapping as a means to visualize veins and quantify oxygen saturation. J Magn Reson Imaging 32, 663–676. 10.1002/jmri.22276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke EM, Xu Y, Cheng Y-CN, Reichenbach JR, 2004. Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI). Magn Reson Med 52, 612–618. 10.1002/mrm.20198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JJ, Jolivet R, Attwell D, 2012. Synaptic energy use and supply. Neuron 75, 762–777. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y, Tamhane AC, 1987. Multiple Comparison Procedures. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeijer J, van Putten MJAM, 2012. Ischemic cerebral damage: an appraisal of synaptic failure. Stroke 43, 607–615. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.632943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, De Silva TM, Chen J, Faraci FM, 2017. Cerebral Vascular Disease and Neurovascular Injury in Ischemic Stroke. Circ. Res. 120, 449–471. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, 2013. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 80, 844–866. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Dong, Haacke EM, 2005. ARGDYP: an adaptive region growing and dynamic programming algorithm for stenosis detection in MRI, in: Proceedings. (ICASSP ‘05). IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 2005. Presented at the Proceedings. (ICASSP ‘05). IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 2005., p. ii/465-ii/468 Vol. 2. 10.1109/ICASSP.2005.1415442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch G, Colgan T, Wiens CN, Wang X, Schubert T, Hernando D, Sharma SD, Reeder SB, 2018. Relaxivity of Ferumoxytol at 1.5 T and 3.0 T. Invest Radiol 53, 257–263. 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch KM, Papademetris X, Rothman DL, Graaf R.A. de, 2006. Rapid calculations of susceptibility-induced magnetostatic field perturbations for in vivo magnetic resonance. Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 6381. 10.1088/0031-9155/51/24/007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Brisset J-C, Hu J, Haacke EM, Ge Y, 2018. Susceptibility weighted imaging and quantitative susceptibility mapping of the cerebral vasculature using ferumoxytol. J Magn Reson Imaging 47, 621–633. 10.1002/jmri.25809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Buch S, Chen Y, Choi H-S, Dai Y, Habib C, Hu J, Jung J-Y, Luo Y, Utriainen D, Wang M, Wu D, Xia S, Haacke EM, 2017. Susceptibility-weighted imaging: current status and future directions. NMR Biomed 30. 10.1002/nbm.3552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Cohen MH, Rieves D, Pazdur R, 2010. FDA report: Ferumoxytol for intravenous iron therapy in adult patients with chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Hematol. 85, 315–319. 10.1002/ajh.21656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka H, Akima M, Hatori T, Nagayama T, Zhang Z, Ihara F, 2003. Microvasculature of the human cerebral white matter: arteries of the deep white matter. Neuropathology 23, 111–118. 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2003.00486.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyce AJ, Lees AJ, Schrag A-E, 2016. The prediagnostic phase of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 87, 871–878. 10.1136/jnnp-2015-311890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue H, Kaito N, Tokudome S, Abe T, Tashibu K, Nagashima H, Nakamura N, 1993. Investigation of postmortem functional changes in human cerebral arteries. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 13, 346–349. 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacelli C, Giguère N, Bourque M-J, Lévesque M, Slack RS, Trudeau L-É, 2015. Elevated Mitochondrial Bioenergetics and Axonal Arborization Size Are Key Contributors to the Vulnerability of Dopamine Neurons. Curr. Biol. 25, 2349–2360. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel DJ, Janicki JS, 1970. Static elastic properties of the left coronary circumflex artery and the common carotid artery in dogs. Circ. Res. 27, 149–158. 10.1161/01.res.27.2.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters AM, Brookes MJ, Hoogenraad FG, Gowland PA, Francis ST, Morris PG, Bowtell R, 2007. T2* measurements in human brain at 1.5, 3 and 7 T. Magn Reson Imaging 25, 748–753. 10.1016/j.mri.2007.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamon G, 1971. Atlas of arteries of the human brain. Sandoz, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Salomir R, de Senneville BD, Moonen CT, 2003. A fast calculation method for magnetic field inhomogeneity due to an arbitrary distribution of bulk susceptibility. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance Part B: Magnetic Resonance Engineering 19B, 26–34. 10.1002/cmr.b.10083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schweser F, Deistung A, Lehr BW, Reichenbach JR, 2011. Quantitative imaging of intrinsic magnetic tissue properties using MRI signal phase: an approach to in vivo brain iron metabolism? Neuroimage 54, 2789–2807. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle SR, Speed FM, Milliken GA, 1980. Population Marginal Means in the Linear Model: An Alternative to Least Squares Means. The American Statistician 34, 216–221. 10.2307/2684063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Hu J, Eteer K, Chen Y, Buch S, Alhourani H, Shah K, Jiang Q, Ge Y, Haacke EM, 2020. Detecting sub-voxel microvasculature with USPIO-enhanced susceptibility-weighted MRI at 7 T. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 67, 90–100. 10.1016/j.mri.2019.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studholme C, Hill DLG, Hawkes DJ, 1999. An overlap invariant entropy measure of 3D medical image alignment. Pattern Recognition 32, 71–86. 10.1016/S0031-3203(98)00091-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MD, Kisler K, Montagne A, Toga AW, Zlokovic BV, 2018. The role of brain vasculature in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1318–1331. 10.1038/s41593-018-0234-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Liu S, Neelavalli J, Cheng YCN, Buch S, Haacke EM, 2013. Improving susceptibility mapping using a threshold-based K-space/image domain iterative reconstruction approach. Magn Reson Med 69, 1396–1407. 10.1002/mrm.24384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker WD, Mahajan K, 2020. Anatomy, Blood Vessels, in: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PJ, Mougin OE, Totman JJ, Peters AM, Brookes MJ, Coxon R, Morris PE, Clemence M, Francis ST, Bowtell RW, Gowland PA, 2008. Water proton T1 measurements in brain tissue at 7, 3, and 1.5 T using IR-EPI, IR-TSE, and MPRAGE: results and optimization. MAGMA 21, 121–130. 10.1007/s10334-008-0104-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Pavlovic D, Waldvogel H, Dragunow M, Synek B, Turner C, Faull R, Guan J, 2015. String Vessel Formation is Increased in the Brain of Parkinson Disease. J Parkinsons Dis 5, 821–836. 10.3233/JPD-140454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Hu J, Wu D, Haacke EM, 2013. Noncontrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography and venography imaging with enhanced angiography. J Magn Reson Imaging 38, 1539–1548. 10.1002/jmri.24128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokovic BV, 2008. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron 57, 178–201. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.