Abstract

Pharmacists have had long-standing roles in public health, and the COVID-19 pandemic has broadened and accentuated their efforts in this area. Many pharmacists may be interested to expand pharmacy services to further support public health. While not intending to be exhaustive, this paper suggests potential areas for increased engagement and provides ideas for pharmacists who want develop and implement new initiatives to optimize the health of their patients and communities. The core functions of public health and the natural history of disease are presented as models to identify opportunities for pharmacists’ interventions. A three-step framework with practical strategies and helpful resources is proposed to identify and operationalize new services. Finally, the pharmacist’s role in clinical-community linkages is presented. It is hoped that this paper will stimulate additional ideas and actions in the pharmacy community to support public health.

Keywords: pharmacist, public health, preventive health services

Background

Public health “protects and improves the health of individuals, families, communities, and populations”.1 Public health is prevention-oriented and focuses on education and services to optimize health, research to understand and mitigate health conditions, and policy development to facilitate health improvements.1,2 Public health also promotes health care equity, accessibility, and quality.1,2

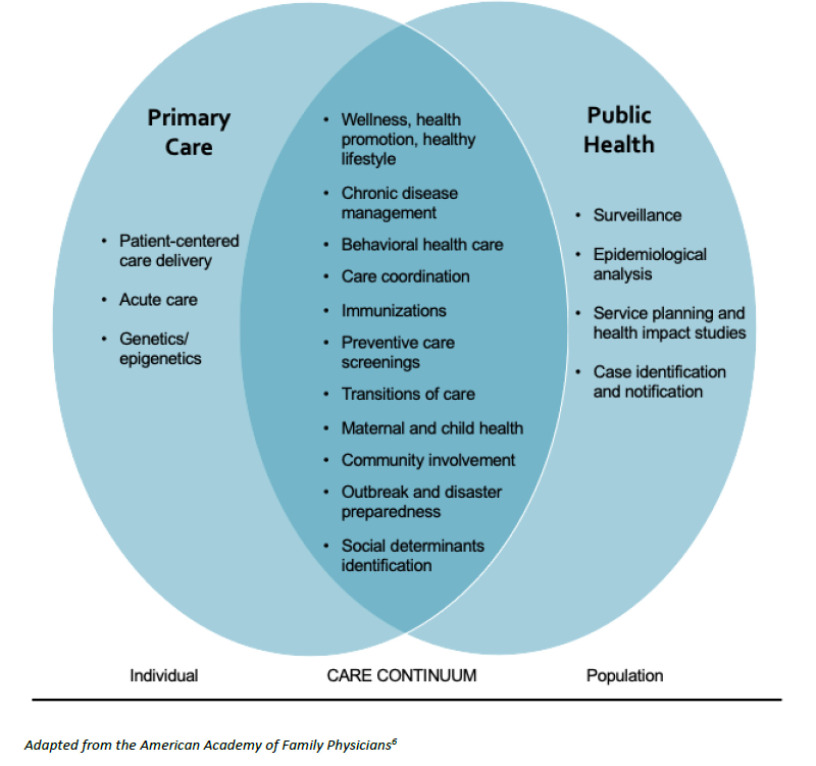

Given their accessibility and expertise, pharmacists’ impact in public health has been recognized.3-5 Indeed, by the very nature of their work many of the patient care activities pharmacists provide, especially in primary care settings,6,7 improve public health at the “micro” level (Figure 1).3,4 Some pharmacists choose to take on more formal roles in public health practice at the “macro” level, such as working at a health department or serving as a health administrator.3,4 The COVID-19 pandemic broadened and accentuated pharmacists’ public health efforts.8,9 At this time, many pharmacists may be interested to maintain these extended roles in public health activities and even expand pharmacy services to further support public health. This paper provides a framework for those wanting to develop and implement new initiatives to optimize the health of their patients and communities.

Figure 1.

Primary care and public health care continuum 6

Opportunities for Pharmacists in the Core Functions and Essential Services of Public Health

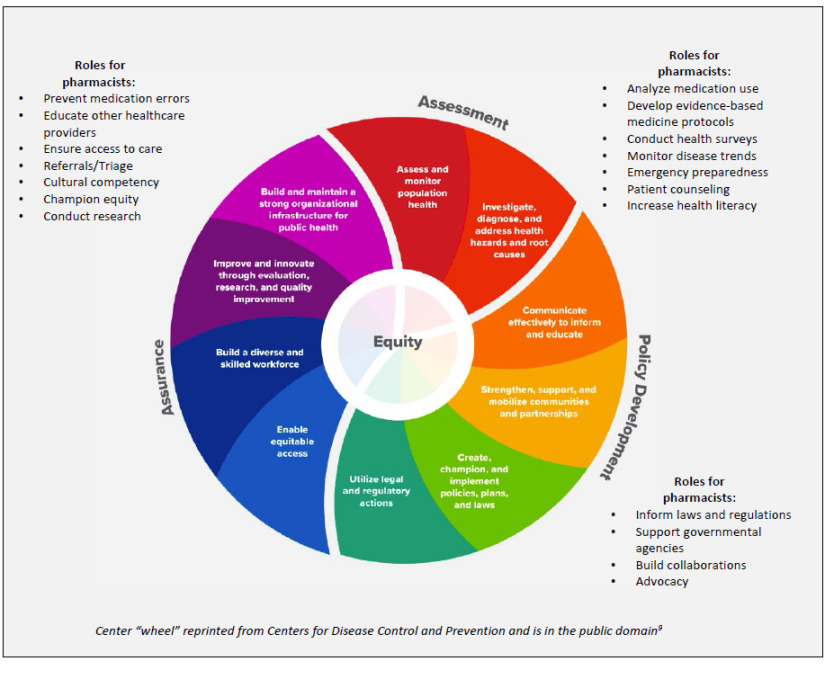

The well-known model of public health’s three core functions and ten essential health services presents opportunities for pharmacists to contribute to its mission.3,10 This long-standing model was updated in 2020 to bring it in line with current and future public health practice and to emphasize the central importance of health equity.10 The three core public health functions of assessment, policy development, and assurance encompass actions all communities should take to protect and promote health.10 Figure 2 shows the multiple ways that pharmacists can carry out the essential health services to strengthen the public health system.3,10

Figure 2.

Pharmacist contributions to the core functions and essential services of public health 3,9

Opportunities for Pharmacists in Preventive Care

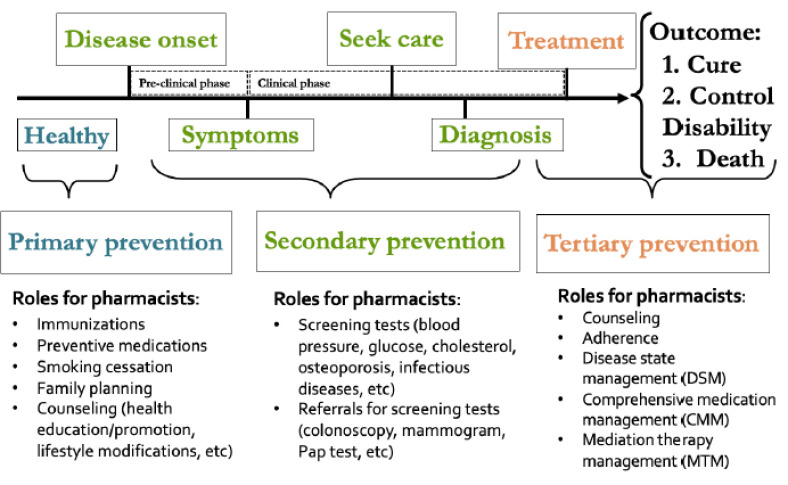

The natural history of disease describes the development and course of a disease in an individual over a period of time, starting when an individual is healthy and continuing until the outcome of the disease is experienced.11 There are two phases: the pre-clinical phase is the time when the patients do not realize they have a disease; the clinical phase is when the disease symptoms become apparent. 11 The natural history of disease highlights places for pharmacist intervention and opportunities to provide preventive care services (Figure 3).3,11

Figure 3.

Opportunities for pharmacist intervention in the natural history of disease to provide preventive services 3,10,11

Commonly, preventive activities are classified as primary, secondary or tertiary.12 Primary prevention services are provided with the goal to prevent development of disease.12 Secondary prevention services strive to identify early-stage disease, ideally in the pre-clinical phase, to mitigate its impact.12 Tertiary prevention services are provided in the clinical phase once a disease is diagnosed to slow or stop its progression.12 Figure 3 illustrates typical preventive services provided by pharmacists3 and the possible practice paradigms that may be employed to provide care including disease state management, collaborative medication management, and medication therapy management.13, 14 Collaborative practice agreements and provider status are essential to enabling pharmacists to provide these services, within their scope of practice.15

Opportunities to Develop New Pharmacy Services

Potential pharmacist interventions are apparent in the context of the core functions of public health and the natural history of disease. However, many pharmacists may wonder where to start when trying to decide which services to actually implement. Figure 4 provides a simple framework to aid in the deliberation and summarizes the step-wise approach described below.

Figure 4.

Steps to expand pharmacy services to support public health

Determining Health Needs

In order for the new service to be successful, there must be demand for it. Therefore, the first step is for pharmacists to determine the health needs in their areas. There are many sources of information on public health needs from national to local data.

Healthy People 2030 (https://health.gov/healthypeople) was released by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2020.16 It gives direction for priority areas of the nation’s health to address in the next decade.17 There are 355 measurable objectives organized in five categories: health conditions; health behaviors; populations; settings and systems; and social determinants of health.17 Healthy People encourages providers to use these objectives to identify needs and to set local targets for improvement.18 The website also lists evidence-based resources and shares information about successful programs and policies.19

There are other pertinent resources to also consult. States and communities across the country have developed health needs assessments and health improvement plans as directed by the Affordable Care Act.20 These are excellent documents for pharmacists wanting to better understand local health needs and the long-term plans to solve them.21 Pharmacists should also reach out to their state and local health departments; many are very interested to learn more about pharmacy and would welcome conversations about ways to work together.

Developing the Service

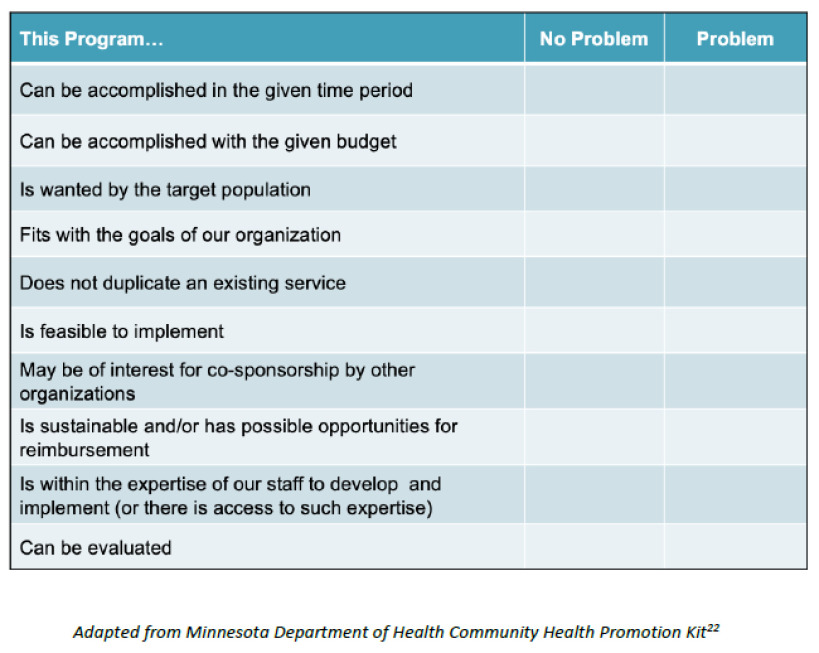

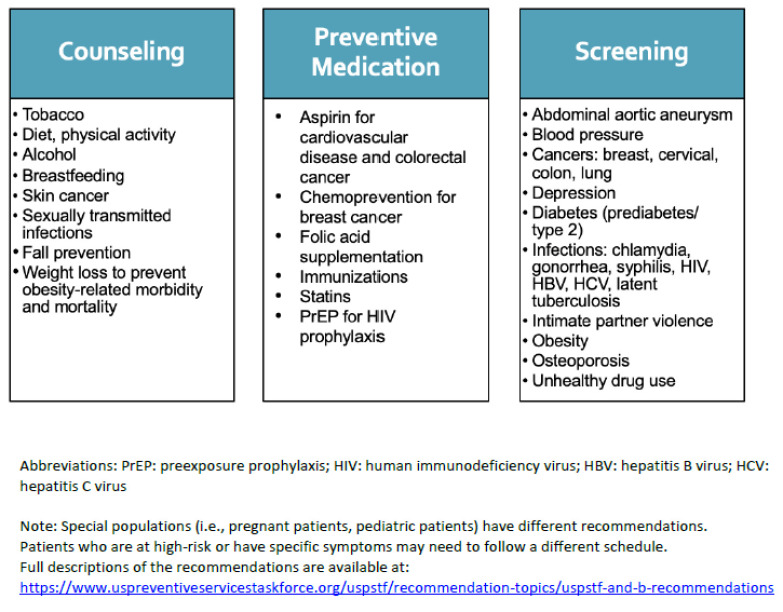

Once the area(s) of need have been determined, it’s time to decide which specific service(s) will be developed and implemented. The checklist in Figure 5 can be used to help determine which services are reasonable.22 There are also multiple blueprints available to help pharmacists at this stage. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has published several guides that can be used to facilitate pharmacists’ collaboration with physicians, health departments, and other entities (https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/toolkits/pharmacy.htm).23 Another helpful resource is the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which publishes guidelines regarding the preventive health services that should be routinely provided in primary care settings and the specific patients who would most benefit from these services (Figure 6).24 They also have created the Electronic Preventive Services Selector (ePSS) which allows clinicians to input selected patient demographics and generates a list of possible interventions (http://epss.ahrq.gov/PDA/index.jsp).25 Similarly, the Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF)26 performs systematic reviews on the effectiveness of various interventions and collates them in The Community Guide (https://www.thecommunityguide.org/).27

Figure 5.

Sample checklist to aid in determination of which pharmacy service(s) to develop 22

Figure 6.

Preventive services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force as of August 2021 for the general, adult, non-pregnant population24

Abbreviations: PrEP: preexposure prophylaxis; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus

Note: Special populations (i.e., pregnant patients, pediatric patients) have different recommendations.

Patients who are at high-risk or have specific symptoms may need to follow a different schedule.

Full descriptions of the recommendations are available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics/uspstf-and-b-recommendations

While developing the service, pharmacists must be strategic in their planning. What kind of resources are required, and how can this become a sustainable service? Having SMART objectives (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-bound)28 will allow for financial considerations such as creating a budget, performing breakeven analysis, and calculating return-on-investment as well as service evaluation. Additionally, developing a logic model provides a succinct visual aid to summarize the inputs, activities, and anticipated outcomes of the program and can be used for planning and evaluation.29

There are several aspects of service implementation that must also be addressed. Resources including personnel, money, supplies, and space should be allocated.30 Tasks should be outlined, and a timeline with mini-milestones should be established.30 Team members’ responsibilities should be clearly designated.30 Finally, procedures for documentation must be established.

Evaluating the Service

The final step is to evaluate the service once it has been established. However, planning for the evaluation should occur prior to implementation. Outcomes, measures, and data sources should be determined beforehand.31 Also, pharmacists should confer with various stakeholders as necessary, especially regarding data collection and access. 31 Goals of evaluation should be clearly indicated, and may include to track how well the service is being implemented (process evaluations); its impact (outcomes or effectiveness evaluations); its success in achieving its ultimate goals (impact evaluations) or to identify necessary changes as part of continuous quality improvement. 31,32

Evaluations should occur throughout the operation of the service at appropriate intervals as well as at its end, if applicable.32 This information is important to track the course of the service implementation, quantify its effect, and inform the development of additional services.32 It is important to also disseminate findings externally via presentations or publications in professional, practice, or other settings. This is key to spread the message of pharmacy’s impact in improving health and to share best practices and lessons learned.

Opportunities for Referral

Pharmacists are not always equipped to close public health gaps themselves. In these instances, referrals are crucial. Pharmacists function as part of clinical-community linkages and serve as a bridge to the other health care providers, public health and governmental agencies, or community-based organizations specializing in the particular services the patient might need.33,34 Pharmacists should make themselves and their staff aware of the resources available in the communities they serve and the proper referral pathways to meet patients’ clinical health or social determinant of health needs.

Conclusion

Pharmacists should realize the many ways they already affect public health and consider opportunities to become even more involved. While not intending to be exhaustive, this paper suggests potential areas for increased engagement and gives practical tips and strategies to accomplish such goals. It is hoped that this paper will stimulate additional ideas and actions in the pharmacy community to support public health.

Acknowledgements: None

Funding/Support: None

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health. What is public health? https://www.aspph.org/discover/ Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 2.CDC Foundation. What is public health? https://www.cdcfoundation.org/what-public-health Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 3.American Public Health Association. Washington DC:: American Public Health Association; 2006. Policy statement database: The role of the pharmacist in public health. Policy number 200614. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on the role of health-system pharmacists in public health. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008;65:462–7. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strand MA, DiPietro Mager NA, Hall L, Martin SL, Sarpong DF. Pharmacy contributions to improved population health: Expanding the public health roundtable. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:200350. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.200350. . DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Family Physicians. Position paper: Integration of primary care and public health. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/integration-primary-care.html Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 7.Institute of Medicine. Primary care and public health: Exploring integration to improve population health. Washington DC:: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross AE, MacDougall C. Roles of the clinical pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3:564–566. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1231. . DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strand MA, Bratberg J, Eukel H, Hardy M, Williams C. Community pharmacists’ contributions to disease management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:200317. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.200317. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2020/20_0317e.htm.] DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.200317 [Erratum appears in Prev Chronic Dis 2020;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 essential public health services. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Natural history and spectrum of disease. In: Principles of epidemiology in public health practice. 3rd ed. Atlanta, GA:: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Picture of America: Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/pictureofamerica/pdfs/picture_of_america_prevention.pdf Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 13.Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. Disease management. https://www.amcp.org/about/managed-care-pharmacy-101/concepts-managed-care-pharmacy/disease-management Accessed September 8, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. McBane SE, Dopp AL, Abe A, Benavides S, Chester EA, Dixon DL, Dunn M, Johnson MD, Nigro SJ, Rothrock-Christian T, Schwartz AH, Thrasher K, Walker S. Collaborative drug therapy management and comprehensive medication management-2015. Pharmacotherapy. 201535(4):e39–50. doi: 10.1002/phar.1563. 10.1002/phar.1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cernasev A, Aruru M, Clark S, Patel K, DiPietro Mager N, Subramaniam V, Truong HA. Empowering public health pharmacy practice—moving from collaborative practice agreements to provider status in the U.S. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(1):57. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy9010057. org/10.3390/pharmacy9010057 . doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.; 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople Healthy People. Accessed September 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.; https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives Browse objectives. Accessed September 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.; https://health.gov/healthypeople/tools-action Tools for action. Accessed September 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.; https://health.gov/healthypeople/tools-action/browse-evidence-based-resources Browse evidence-based resources. Accessed September 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.HPSA Acumen. Community health needs assessment (CHNA) https://hpsa.us/services/chna/community-health-needs-assessment-chna/ Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community health assessment and health improvement planning. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/cha/index.html Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 22.Minnesota Department of Health. Choosing programs: Is this program right for us? http://www.health.state.mn.us/communityeng/needs/choose.html Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pharmacy resources. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/toolkits/pharmacy.htm Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 24.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/ Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 25.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Electronic Preventive Services Selector (ePSS). http://epss.ahrq.gov/PDA/index.jsp Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 26.Community Preventive Services Task Force. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/task-force/about-community-preventive-services-task-force Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 27.Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. www.thecommunityguide.org. Accessed September 8, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/evaluation_resources/guides/writing-smart-objectives.htm Writing SMART objectives. Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluation guide: Developing and using a logic model. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/docs/logic_model.pdf Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 30.Eby K. From strategy to execution: How to create a sustainable, repeatable implementation plan. https://www.smartsheet.com/implementation-plan Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Creating community-clinical linkages between community pharmacists and physicians: A pharmacy guide. cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/ccl-pharmacy-guide.pdf. Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Types of evaluation. https://www.cdc.gov/std/program/pupestd/types%20of%20evaluation.pdf Accessed September 8, 2021.

- 33.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical-community linkages. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/community/index.html Accessed September 8, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community-clinical linkages for the prevention and control of chronic diseases: A practitioner’s guide. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/ccl-practitioners-guide.pdf Accessed September 8, 2021.