Abstract

We describe here the presence of two distinct types of rRNA operons in the genome of a thermophilic actinomycete Thermomonospora chromogena. The genome of T. chromogena contains six rRNA operons (rrn), of which four complete and two incomplete ones were cloned and sequenced. Comparative analysis revealed that the operon rrnB exhibits high levels of sequence variations to the other five nearly identical ones throughout the entire length of the operon. The coding sequences for the 16S and 23S rRNA genes differ by approximately 6 and 10%, respectively, between the two types of operons. Normal functionality of rrnB is concluded on the basis of the nonrandom distribution of nucleotide substitutions, the presence of compensating nucleotide covariations, the preservation of secondary and tertiary rRNA structures, and the detection of correctly processed rRNAs in the cell. Comparative sequence analysis also revealed a close evolutionary relationship between rrnB operon of T. chromogena and rrnA operon of another thermophilic actinomycete Thermobispora bispora. We propose that T. chromogena acquired rrnB operon from T. bispora or a related organism via horizontal gene transfer.

Protein synthesis is one of the most conserved functions of organisms. Some components of the protein synthesis apparatus, such as rRNAs (rRNA), are present in organisms belonging to all three domains of life: Eucarya, Bacteria, and Archaea (32, 38, 40). Highly stringent functional constraints on rRNA molecules render them the slowest-evolving molecules. Such molecules may potentially record the entire evolutionary history of an organism and its phylogenetic relationships with others (32, 38). The ample information capacity of the large- and small-subunit rRNA genes and their division into fast- and slow-evolving regions are thought to permit the documentation of different stages of evolution (32). Taken together, rRNA genes are considered ideal chronometers for the study of organismal evolution and, therefore, are widely used in the reconstruction of evolutionary history and phylogenetic relationships and in the classification and identification of organisms (1, 32).

Acceptance of rRNA as the ideal chronometer was also based on two important but understated assumptions. First, multiple copies of rRNA genes in an organism are either identical or nearly identical in nucleotide sequence; and second, rRNA genes are not subjected to horizontal gene transfer. Recently, evidences demonstrating the heterogeneity of rRNA sequences in a single organism have been steadily accumulating. Although in most cases the level of divergence is lower than 2% (4, 5, 21, 23, 30), the number of reports of divergence at much higher levels is hard to ignore. For example, the genome of the eucaryotic parasite Plasmodium berghei and the metazoan Dugesia mediterranea contains two types of 18S rRNA genes differing at 3.5 and 8% of the nucleotide positions, respectively (3, 10, 26). A 5% difference was also reported between two types of 16S rRNA genes in an archaebacterium, Haloarcula marismortui (28). Wang et al. (37) recently described the presence of two distinct types of 16S rRNA genes in a bacterium Thermobispora bispora. It is noteworthy that these organisms belong to different domains of life, indicating a wide distribution of this phenomenon. The origin of distinct types of rRNA genes in a single genome has been attributed to either divergent evolution after gene duplication or horizontal gene transfer (28, 37). The latter explanation is becoming increasingly attractive with the rapidly growing body of evidences showing the transfer of numerous genes between organisms across taxonomic boundaries (8, 9, 18, 20, 29, 34, 39). However, in none of the cases could the potential donor organism of an rRNA gene be identified.

T. bispora (36), the only known species of the genus, possesses four rrn operons: rrnA, rrnB, rrnC, and rrnD (37). rrnC and rrnD are complete operons, each containing a set of 16S, 23S, and 5S rRNA genes; rrnA and rrnB are incomplete in that rrnA contains only 16S and 23S rRNA genes and rrnB contains only a 16S rRNA gene. The 16S genes of rrnA and rrnC are of the same type (type I), sharing 99% nucleotide identity, while they differ at 98 nucleotide (nt) positions (6.4%) from type II 16S rRNA genes belonging to rrnB and rrnD. Surprisingly, all three 23S rRNA genes are almost identical. To explain the gene compositions and the structure of the rrn operons of T. bispora, it was hypothesized that the organism acquired a partial rrnB-like operon from another bacterial species. The partial operon duplicated once and then recombined one copy with an existent rrnC-like operon, leading to the generation of a mosaic rrnD (37). In this study we set out to look for the potential donor of the rrnB-like 16S rRNA gene. We reasoned that, first, the donor was likely to be an actinomycete not very distant from T. bispora, as indicated by the 6.4% variations between the two types of 16S rRNAs and, second, the donor and recipient organisms probably live in the same ecological niche. We therefore chose to start our search in another group of thermophilic actinomycetes, Thermomonospora species, who share with T. bispora similar optimal growth temperature and morphological and chemotaxonomic properties (41). By sequence analysis of multiple clones of the 16S rDNA PCR amplified from the genome of each Thermomonospora species, we found that Thermomonospora chromogena also possesses two distinct 16S rRNA genes which exhibit different levels of relatedness with the two types of 16S rRNA genes of T. bispora. Such an observation motivated us to clone, sequence, and characterize the rrn operons of T. chromogena and to study the relationships between different types of rrn operons of the two organisms. Here we report the result of this study and discuss its implications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

T. chromogena ATCC 43196T and Streptomyces lividans ATCC 19844T were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Rockville, Md. Thermomonospora chromogena JCM 6244T and other Thermomonospora species were obtained from the Japan Collection of Microorganisms, Wako, Japan. Each strain was grown in media under conditions recommended by the suppliers.

Oligonucleotide probes.

All oligonucleotide probes were synthesized by Oligos Etc., Inc., Wilsonville, Oreg.

Preparation of chromosomal DNA.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared as described previously (36).

Slot blot and Southern hybridization.

Slot blot hybridization was carried out by blotting DNA samples onto a Hybond-N membrane (Amersham, Aylesbury, United Kingdom) with a slot hybridization apparatus (Hoefer Instruments, San Francisco, Calif.). Southern blotting, probe labelling, and hybridizations were carried out according to procedures previously described (24).

PCR amplification and cloning of rDNA.

PCR amplification and cloning of 16S rDNA was carried out as described previously (36). The 5′ one-third of the 23S rRNA genes were amplified by PCR with a pair of primers, one targeting a conserved region at the end of the 16S rRNA gene and the other targeting a conserved block within the 23S rRNA gene. The sequences of the two oligonucleotides are as follows: 5′-GGTTGGATCCACCTCCTT-3′ corresponding to nt 1525 to 1542 of the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene (2) and 5′-ACCAGTGA GCTATTAGCG-3′ (nt 1090 to 1107, E. coli numbering). The 16S-23S rRNA gene spacer is included in the PCR-amplified fragment. The PCR products were cloned in pBluescript as described previously (36). M13 forward and reverse universal primers were used for sequencing the ends of cloned rDNA. The internal regions were sequenced in both orientations by using the following two sets of oligonucleotide primers targeting two conserved sequences within 23S rDNA. The first set of primers targeting a site corresponding to nt 45 to 60 of E. coli 23S rRNA gene are 23S-40f (5′-CCGATGAAGGACGTGGGA-3′) and 23S-40r (5′-TCCCACGTCCTTCATCGG-3′); the second set of primers targeting nt 456 to 472 are 23S-460f (5′-CCTTTCCCTCACGGTACT-3′) and 23S-460r (5′-AGTACCGT GAGGGAAAGG-3′).

Cloning of rRNA operons.

A total of 12 μg of chromosomal DNA was digested with BamHI or SalI restriction enzyme, and the DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a 0.8% low-melting-point agarose (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) gel. DNA fragments of about 3 to 6 kbp, 6 to 9 kbp and 9 to 12 kbp were recovered from the agarose gel and ligated into pBluescript SK (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) which had been digested with either BamHI or SalI and dephosphorylated with calf intestinal phosphatase. The ligation mixture was used to transform E. coli DH10B, and recombinant colonies were picked and inoculated into 100 μl of Luria-Bertani broth (LB) supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml in 96-well microtiter plates. The cultures were grown overnight, and 50 μl of each culture was transferred into wells of a new microtiter plate. An equal volume of a solution containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 1 M NaOH was added to lyse the cells and denature the DNA. Twenty microliters of each lysate was slot-blotted onto Hybond-N membrane, and the presence of rRNA genes were detected by hybridization.

DNA sequencing and sequence analyses.

DNA sequencing was carried out with the Taq Dye Primer Cycle Sequencing Kit and the Applied Biosystem model 373 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The complete nucleotide sequences of 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA genes were determined in both directions by using a set of primers based on conserved regions within the rRNA genes (19). Based on the results obtained from earlier rounds of sequencing analyses, new primers were designed to determine the sequences flanking the rRNA coding regions. Nucleotide sequences were aligned, and sequence similarity values were calculated by using the DNASTAR (Madison, Wis.) program. For phylogenetic analysis, a sequence distance matrix was generated by the method of Jukes and Cantor (16). Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed by using the neighbor-joining method of Saitou and Nei (31), and tree robustness was assessed by using the bootstrap method (6).

Preparation of RNA and Northern hybridization.

Total RNA was prepared as previously described (37). Northern hybridization was carried out according to a standard procedure (24).

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of PCR-amplified 16S rDNA of Thermomonospora species.

All Thermomonospora species listed in the Bergey’s Manual of Bacteriology (25) were included in this study. Nearly-complete 16S rDNAs were isolated by PCR from genomic DNA by using a pair of primers targeting the two ends of 16S rRNA genes (19). The PCR products were cloned into the plasmid pBluescript, and multiple clones from each species were subjected to DNA sequence analysis. Two 16S rDNA clones from the species T. chromogena were found to differ at approximately 6% of the nucleotide positions, but no significant heterogeneity was observed between different clones obtained from any of the other Thermomonospora species. Interestingly, a preliminary phylogenetic analysis showed that the two 16S rDNA sequences are much more closely related with the 16S sequences of T. bispora than with those of other Thermomonospora species (see below).

Southern blot analysis, cloning and sequencing of the rrn operons.

The above observations prompted us to further characterize the rrn operons of T. chromogena and to delineate their relationships with those of related actinomycete species, especially T. bispora.

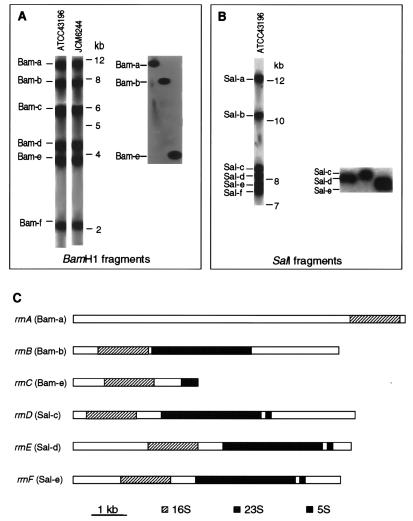

It is possible that our observation of two distinct types of 16S rDNA amplified from T. chromogena genome was an artifact due to contamination of either the culture or PCR reagents. To rule out this possibility, first, we acquired T. chromogena from a second culture collection, JCM, and carried out subsequent analyses of its rrn operons in parallel with the first culture which was purchased from the ATCC. Second, we cloned individual rrn operons from genomic DNA without using PCR. Genomic DNAs were prepared from both cultures grown from single colonies and cleaved with the restriction enzyme BamHI. According to the sequence data obtained above, no BamHI cleavage site exists within either type of 16S rRNA genes. BamHI digestion should produce DNA fragments containing intact 16S rRNA genes. Southern blot hybridization with a 16S-specific probe revealed an identical pattern of six equally intense bands from the genomic DNAs of both cultures, indicating the presence of six rrn operons in the genome (Fig. 1A, left). The first round of cloning of the rrn operons led to the isolation of three clones containing the DNA fragments designated Bam-a, Bam-b, and Bam-e (Fig. 1A, right). The nucleotide sequences of the three DNA fragments were determined, and the content of each fragment was schematically presented in Fig. 1C. In Bam-b reside a copy each of the 16S and 23S rRNA genes separated by a 165-bp spacer, but no 5S rRNA gene was found within the almost 2000-bp region downstream of the 23S rRNA gene. The Bam-e fragment contains a 16S rRNA gene, a much longer 802-bp 16S-23S spacer and a 446-bp 5′ segment of a 23S rRNA gene. In Bam-a only a 16S rRNA gene and a partial 16S-23S spacer are present toward its 3′ end. Sequence comparisons of the three BamHI fragments revealed that the 16S rRNA genes on Bam-a and Bam-e are 97.5% identical to each other but exhibit only 91.1 and 89.7% similarities with the 16S rRNA gene carried on Bam-b, respectively. Unexpectedly, the 446-bp 23S rRNA gene segment in Bam-e shows a strikingly low 80% similarity to the corresponding region in Bam-b. Taken together, it appears that in T. chromogena genome exist two distinct types of rrn operons. The two types of 16S rRNA genes found by the cloning strategy match perfectly the two types identified by the PCR-based experiment described above. Thus, the possibility of contamination is ruled out. From here on, we only present the results obtained from the analyses of the ATCC culture.

FIG. 1.

Southern blot analysis and cloning of rrn operons of T. chromogena. The genomic DNA prepared from two cultures of T. chromogena (ATCC 41196 and JCM 6244) were cleaved separately with either BamHI (A, left) or SalI (B, left). The cloned BamHI fragments (A, right) or SalI fragments (B, right) were released from plasmid by cleavage by using corresponding restriction enzymes. A 16S rDNA-specific probe was prepared by PCR amplification of the complete coding region from the genomic DNA by using a pair of primers targeting the conserved ends of the gene (19). (C) Schematic description of the content of six cloned rrn-containing DNA fragments and the designation of the operons.

In order to clone intact rrn operons, the genomic DNA of T. chromogena was cleaved separately by a series of restriction enzymes and examined by Southern blot hybridization by using probes specific for different regions of rrn operon. The restriction enzyme SalI was found to generate six fragments, and all appeared to contain complete rrn operons. Figure 1B (left) shows the hybridization pattern of SalI-digested genomic DNA and the designation of the six rrn-containing fragments. Three SalI fragments, Sal-c, Sal-d, and Sal-e, were cloned (Fig. 1B, right), and their sequences were determined. Each of the three SalI fragments contains a complete set of 16S, 23S, and 5S rRNA genes with flanking sequences on both ends (Fig. 1C). A pairwise sequence comparison demonstrated that the three operons are very similar in sequence in the coding regions of 16S, 23S, and 5S rRNA genes. However, sequence variations are present in the promoter, the 16S-23S spacer, and both the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions, indicating that they represent three different rrn operons. None of the rRNA genes on the three SalI fragments is the same as any of those on the three cloned BamHI fragments. Thus, we have obtained clones representing all the six rrn operons of T. chromogena, and we designate the six rrn operons on these cloned DNA fragments as indicated in Fig. 1C. Sequence comparison of all six operons uncovered high levels of sequence variations throughout the entire length of the operon between rrnB and the other five operons that are highly similar to one another (these five operons rrnA, rrnC, rrnD, rrnE, and rrnF are designated as type I operons). Approximately 6 and 10% nucleotide substitutions are scored between the 16S and 23S rRNA genes of rrnB and those of the type I operons, respectively. The dissimilarity extends into the 5′ external (ETS) and the 16S-23S internal (ITS) transcribed spacers. The 16S-23S ITS of rrnB is 165 bp long, about one-fifth the length of its counterparts in type I operons, which are 802 bp for rrnC, 700 bp for rrnD and rrnE, and 713 bp for rrnF. Though a few insertion-deletions are present, high levels of sequence similarities exist between the ITSs of different members of type I operons (sequences not shown). The short ITS of rrnB exhibits little overall homology with its large counterparts of type I operons, but three conserved sequence blocks are present which are thought important for processing primary rRNA transcripts (15, 17). All of the ITSs start with AAGGA and end with (C/T)GTGT and contain an approximately 20-bp highly conserved sequence toward the middle that has been found in many distantly related organisms (Fig. 2B and C; see also reference 37).

FIG. 2.

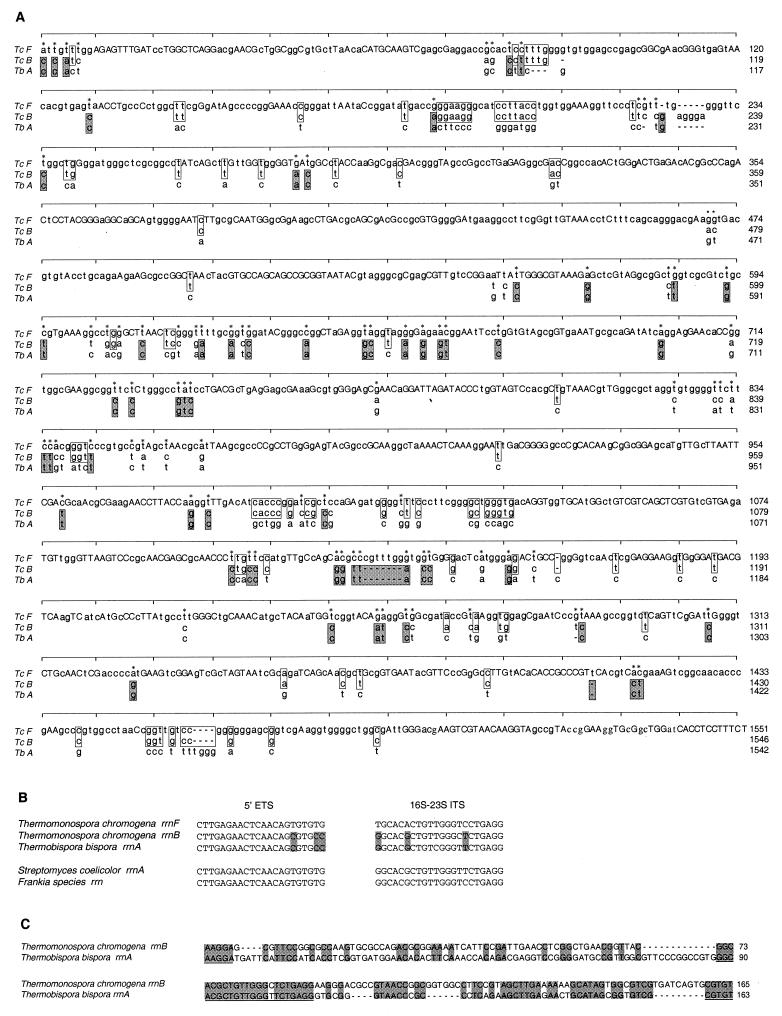

(A) Nucleotide sequence alignment of the 16S rRNA genes of T. chromogena rrnF (representing type I operons) and rrnB and that of T. bispora rrnA. The complete nucleotide sequence of the 16S rRNA gene of T. chromogena rrnF is presented. For the other two sequences, only nucleotides at variable positions are shown. Conserved nucleotides (19, 35) are indicated by uppercase letters. The asterisks mark the nucleotides that differ between rrnF and rrnB operons of T. chromogena. The open boxes show the nucleotides shared between T. chromogena rrnF and rrnB, and the shaded boxes denote those shared between T. chromogena rrnB and T. bispora rrnA. (B) Alignments of two conserved sequence blocks in both the 5′ ETS and the 16S-23S ITS. Nucleotide signatures shared between the sequences of T. chromogena rrnB and T. bispora rrnA are shaded. The corresponding sequences of Streptomyces coelicolor (EMBL X60514) and a Frankia species (GenBank M88466) are included for comparison. (C) Alignment of the 16S-23S spacer sequences of T. chromogena rrnB and T. bispora rrnA. Identical nucleotides are shaded. Conserved sequence motifs important for rRNA processing are underlined (15, 17, 37). The nucleotide sequences of the six rrn operons were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers AF116558 to AF116563.

Distribution and pattern of nucleotide variations in rrnB.

Is rrnB a pseudo-operon? To answer this question, we examined the distribution of nucleotide variations along rrnB in comparison with type I operons. Pseudogenes are expected to accumulate mutations in a random fashion affecting both evolutionarily conserved and variable positions at the same rate. In the 16S rRNA genes, about one-third of the nucleotides are either invariable or conserved in more than 90% of the 16S rRNA molecules that have been determined for bacterial species (19, 35). An inspection of the sequence alignment of the 16S rRNA gene of rrnB and those of type I operons revealed that none of the nearly 90 nt substitutions and several deletion-insertions coincides with any of the evolutionarily conserved positions (Fig. 2A). The same observation was also made from the examination of the alignment of 23S rRNA genes (not shown). The distribution of the base substitutions along the 23S rRNA genes appears to be highly biased in two ways. First, they tend to concentrate in a few regions. For example, in the 400-bp region from nt 300 to 700 nearly 25% of the bases are different between the 23S genes of rrnB and rrnF, while in another region of equal length from nt 2400 to 2800 only five nucleotide substitutions (1.25%) can be found. Second, even in the regions with highly frequent base variations, none of the evolutionarily conserved positions are involved.

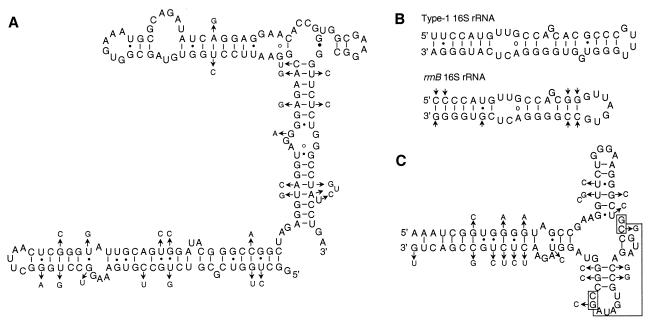

The nonrandom nature of nucleotide substitutions should also be characterized by the presence of compensating covariations of bases that are expected to interact in the secondary and tertiary structures of rRNA molecule (12). We examined the positions of base variations against consensus secondary structure models of 16S and 23S rRNA molecules (12). Many cases of compensating base covariations were readily identified at both secondary and tertiary levels. Figure 3 presents three examples. Two regions of the 16S rRNA of T. chromogena were chosen to generate the secondary structures. The former contains 15% base substitutions (Fig. 3A) and the latter includes an eight-base insertion-deletion (Fig. 3B). We also chose a 77-bp region from the 23S rRNA (Fig. 3C), which possesses an extraordinarily high 32.5% (25 of 77) of base substitutions. Structures very similar to the corresponding domains of the consensus structure models were generated without any difficulty. In all the three cases a majority of the base substitutions reflect compensating covariance, while the rest are either changes that lead to a different type of base pairing, such as G:C to G:U, or are located within loops or at positions that are not expected to destabilize the structure. The eight-base insertion-deletion is localized within a loop known to be highly volatile (12, 35). Figure 3C presents a case of covariation of two bases involved in a tertiary interaction, as well as many incidences of covaried bases for maintaining secondary interaction (12). In summary, the nonrandom distribution of the nucleotide substitutions and the presence of covariations of spatially interacting bases within both 16S and 23S rRNA molecules argue strongly against the possibility of rrnB being a pseudo-operon.

FIG. 3.

Compensating covariation of interacting bases. The secondary structures were generated according to the consensus models for 16S and 23S rRNAs (12). (A) Region corresponding to nt 588 to 753 of E. coli 16S rRNA (2). The nucleotide sequence of T. chromogena rrnF is presented to form the skeleton, and the smaller letters on the side denote the varied nucleotides in the rrnB sequence. Short bars connect the canonical pairings, such as G-C and A-U; small solid dots denote the noncanonical G-U and U-G pairings. Conserved A-G pairings are indicated by circles, and a G-G pairing is indicated by a large solid dot. The arrows point to covaried bases or base substitutions that lead to a different type of pairing, such as G-C to G-U. (B) Region of the 16S rRNA of T. chromogena rrnF and rrnB corresponding to nt 1118 to 1155 of the E. coli gene. This region of rrnB contains an eight-base deletion in comparison with rrnF. (C) Region of 23S rRNA of rrnB (nt 281 to 359, E. coli numbering) that differ from the corresponding region of rrnF at 32.5% nucleotide positions. Two pairs of bases involved in tertiary interaction are boxed and linked by a line.

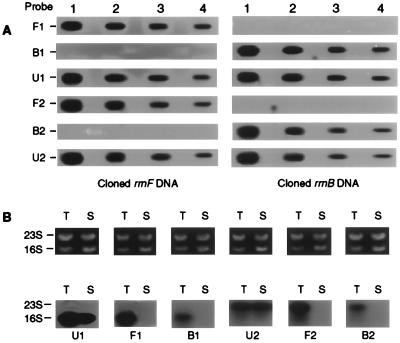

Detection of the expression of rrnB operon.

We used Northern hybridization to determine whether the rrnB operon is expressed and properly processed in the cell. Four oligonucleotides were designed as probes to differentiate rRNAs coded by the two types of operons. We first tested the specificity of each probe by hybridizing it to the two types of cloned rrn operons. Each probe recognized only its target gene without a detectable level of cross-hybridization to the gene from the other type of operon (Fig. 4A). Under identical conditions in a Northern blot analysis, each of the four probes detected a single band at positions corresponding to either 16S or 23S rRNAs as dictated by the specificity of the probe (Fig. 4B). The Northern analysis also included the total RNA prepared from Streptomyces lividans as a negative control. None of the probes specific for T. chromogena rRNAs hybridizes to the streptomycete RNA at a detectable level (Fig. 4B), though the four specific probes share more identical bases with the streptomycete targets than with the corresponding sites of the non-target rRNAs of T. chromogena. This confirms that the hybridization signals detected by rrnB-specific probes are unlikely to be the result of their nonspecific affinity to the rRNAs coded by type I rrn operons. This experiment verifies that rrnB is transcribed and that its transcripts are processed correctly in the cell.

FIG. 4.

Detection of the expression of the two types of rrn operons. (A) Specificity test of the oligonucleotide probes. Plasmids containing cloned rrnF and rrnB were separately slot-blotted onto duplicates of nylon membranes, and each piece of membrane was hybridized to a labeled probe. Names of the probes are shown on the left, and those of the two operons are shown at the bottom. Lanes 1, 2, 3, and 4 contain 20, 6.6, 2.2, and 0.8 ng of plasmid DNA, respectively. The target sequences of the probes are as follows: U1, 5′-CCCAACATCTCACGAC ACG-3′ (nt 1046 to 1064, 1068 to 1086, and 1063 to 1081 of the 16S rRNA genes of S. lividans rrnB, T. chromogena rrnB, and T. chromogena rrnF, respectively); F1, 5′-TGAGTCCCCACCACCCAAA-3′ (nt 1132 to 1150 of the 16S rRNA gene of T. chromogena rrnF); B1, 5′-GAGTCCCCGGCATTACCC-3′ (nt 1130 to 1147 of the 16S rRNA gene of T. chromogena rrnB); U2, 5′-TCGCTTTCGCTACGG CT-3′ (nt 719 to 735, 724 to 740, and 729 to 745 of the 23S rRNA genes of S. lividans rrnB, T. chromogena rrnB, and T. chromogena rrnF, respectively); F2, 5′-CACCGATTTCTCA CTGCT-3′ (nt 353 to 370 of the 23S rRNA gene of T. chromogena rrnF); and B2, 5′-CAGCGATTT GTGACTTCC-3′ (nt 352 to 369 of the 23S rRNA gene of T. chromogena rrnB). Probes were made complementary to the target sequences. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis (top) and Northern blot analysis (bottom) of rRNA. Duplicates of total RNA were prepared from both T. chromogena (T) and Streptomyces lividans (S), resolved by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis, and subjected to Northern analysis. The probe used for each hybridization is indicated at the bottom of each blot.

Evolutionary relationships between the rrn operons of T. chromogena and T. bispora.

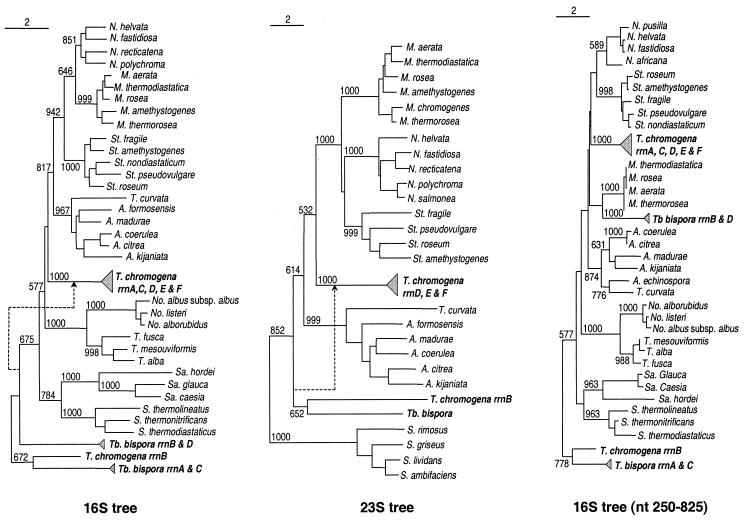

One hypothesis to explain the origin of the two distinct types of operons in T. chromogena is that the organism acquired a rrnB-like operon from another species through horizontal gene transfer. To look for the potential donor of rrnB, we first searched the GenBank by using the BLAST program for genes most closely related with T. chromogena rrnB. T. chromogena rrnB was found to demonstrate the highest level of sequence similarity with the rRNA sequences of T. bispora, followed by sequences from members of several other related actinomycete genera such as Microbispora, Microtetraspora, Nonomuria, Streptosporangium, and Actinomadura. The evolutionary relationship between the rrnB operon of T. chromogena and those of T. bispora were further studied by constructing phylogenetic trees. All of the 16S rRNA sequences of both T. chromogena and T. bispora were analyzed together with 26 representative actinomycete species belonging to closely related genera (Fig. 5, left). When several members of the Streptomyces and Saccharomonospora groups were used to form an outgroup, the 16S rRNA sequence of T. chromogena rrnB aggregates with T. bispora type I 16S rRNAs, forming a stable clade distant from the one that consists solely of the five sequences of T. chromogena type I rrn operons. However, in the absence of the outgroup the branch leading to the clade embracing the 16S rRNA of T. chromogena rrnB and the two types of T. bispora 16S rRNAs joined the type I rrn sequences of T. chromogena, forming a new but unstable clade (bootstrap, <50%). This outgroup-dependent relationship occurs only with the rRNA sequences of T. chromogena rrnB and T. bispora rrn operons. The phylogenetic positions of other Thermomonospora species have been discussed in detail previously (41) and will not be discussed here. To determine whether the gene relationships revealed by the 16S rRNA sequence analysis are reproducible with 23S rRNA sequences, we PCR amplified, cloned, and sequenced the 5′ one-third (ca. 1,200 bp) of the 23S rRNA genes from most of the actinomycete species represented in the 16S rRNA tree. The overall topology of the 23S rRNA tree is very similar to that of the 16S rRNA tree and again the relationship between the rRNAs of T. chromogena and T. bispora changes in an outgroup-dependent manner (Fig. 5, middle). Though uncertainty still exists, the significant stability of the trees constructed in the presence of the outgroup, as indicated by high bootstrap values, implies a fairly close relatedness between T. bispora rRNA genes and T. chromogena rrnB. However, it was not clear what causes the outgroup-dependent phylogenetic relationship change. To seek answers to this question, we inspected a sequence alignment (Fig. 2A) of the two types of 16S rRNAs of T. chromogena (represented by the genes rrnB and rrnF) and the type I 16S rRNA of T. bispora (represented by rrnA). Some very striking sequence features are revealed of the 16S rRNA of T. chromogena rrnB that, we believe, reflects its evolution history and explains the anomalous result of phylogenetic analysis. In the alignment of the three sequences (Fig. 2A) there are a total of 207 variable sites (including positions corresponding to insertion-deletions), of which 97 are identical between the two T. chromogena genes and 69 are identical between T. chromogena rrnB and T. bispora rrnA. The nucleotides shared between each of the two pairs of sequences are distributed in a highly nonrandom fashion. The 16S rRNA sequence of T. chromogena rrnB appears to be divided into segments highly similar to T. chromogena rrnF (e.g., nt 140 to 340 and nt 1310 to 1551) and those nearly identical to T. bispora rrnA (e.g., nt 550 to 750 and nt 1120 to 1150). In stark contrast, the sequences of T. chromogena rrnF and T. bispora rrnA are identical at only 25 positions (of the 207 variable sites), and they are scattered rather evenly throughout the entire length of the gene. When different regions of the sequences were used to repeat the phylogenetic analysis, drastically different relationships between the rRNA genes of the two organisms were obtained, while the relationships between other groups of actinomycetes were largely unaffected. An example is presented in Fig. 5 (right), where the region corresponding to nt 250 to 835 of the 16S rRNA sequence of T. chromogena rrnB was used in the tree construction. On this tree the close relatedness between rrnB and T. bispora rrnA and their distant relationship with T. chromogena type I sequences are demonstrated; these relationships are supported by high bootstrap values and are not affected by the absence of the outgroup. When the same region was excluded from the analysis, a stable tree structure similar to the 16S rRNA tree constructed without the outgroup was generated (tree not shown). Similar observations were also made in the analysis of the 23S rRNA genes (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic trees reconstructed by the neighbor-joining method (31). The 16S rRNA tree (left) was generated by using complete sequences. The 23S rRNA tree (middle) was reconstructed by using sequences of a region corresponding to nt 1 to 1107 of E. coli 23S rRNA. The abbreviations for the genus names are as follows: N, Nonomuria; M, Microbispora; St, Streptosporangium; A, Actinomadura; T, Thermomonospora; No, Nocardiopsis; Sa, Sacchropolyspora; S, Streptomyces; and Tb, Thermobispora. The numbers at the nodes indicate the bootstrap values based on 1,000 resamplings. The broken lines with an arrow show the position of that branch when the Streptomyces and Sacchropolyspora species are not included in the analysis. The tree on the right was constructed by using partial 16S rRNA sequence corresponding to nt 250 to 825 of T. chromogena rrnB. The bars on the top indicate the number of nucleotide substitutions per 100 nt. Except the sequences determined in this study, all 16S rRNA sequences were retrieved from GenBank. All 23S rDNA sequences determined in this study were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers AF116216 to AF116236.

The transcribed spacers of rRNA operons are much more variable than the coding regions (11). Thus, sharing of properties between spacers of different operons may serve as strong indications of relatedness. The 165-bp 16S-23S ITS of T. chromogena rrnB is about one-fifth the length of and shares little homology with those of type I operons. In contrast, it is similar in size and 61% identical to its 163-bp counterpart of T. bispora rrnA. Furthermore, the two spacers of T. chromogena rrnB and T. bispora rrnA share in the 20-bp conserved motif nucleotide signatures that are not present in the corresponding region of T. chromogena type-I rrn operons (Fig. 2B and C). Such conservation of nucleotide signatures also exists in the 20-bp conserved motif in the 5′ ETSs (Fig. 2B) of T. chromogena rrnB and T. bispora rrnA. Another shared structural feature by T. chromogena rrnB and T. bispora rrnA is the lack of the 5S rRNA gene, though sequence similarity between the two operons does not seem to extend beyond the end of 23S rRNA genes. Taken together, these results show that T. chromogena rrnB and T. bispora rrnA share high levels of similarities in both nucleotide sequence and structure throughout nearly the entire length of the operon.

DISCUSSION

The presence of two distinct classes of small-subunit rRNA gene in a single genome has been reported in organisms belonging to all three domains of life. However, in most of these reports, the comparison of sequences was largely limited to the small-subunit rRNA genes, and it is therefore not clear whether and how far the same level of sequence heterogeneity extends into other regions of the operon. Such information may provide crucial evidence for delineating the origin and evolution of the different types of rRNA genes. Here, we present the first description in the genome of a thermophilic actinomycete T. chromogena of two types of rrn operons that demonstrate high levels of sequence heterogeneity throughout the entire length of the operon and provide evidences for intergeneric horizontal transfer of an entire rRNA operon.

T. chromogena genome contains six rrn operons, of which four complete and two partial ones were cloned and sequenced. Comparative sequence analysis revealed that one of the operons, rrnB, is highly divergent from the other five that are very similar among themselves. These five operons are designated type I operons. rrnB differs from type I operons at approximately 6 and 10% of the nucleotide positions in 16S and 23S rRNA genes, respectively, and contains a 16S-23S ITS that is merely one-fifth the length of those of type I operons. To address the possibility that rrnB may represent a nonfunctional pseudo-operon, we inspected the distribution of nucleotide substitutions in the genes and examined the presence of compensating base covariations and the preservation of secondary and tertiary structures in both 16S and 23S rRNAs. We reached the conclusion that rrnB is functional on the basis of the following observations. First, the substituted bases in both 16S and 23S rRNA genes are distributed in a nonrandom fashion in that none of them coincides with any of the evolutionary invariable positions or positions that are conserved in a large majority of bacteria. Second, most of the base changes are involved in compensating covariations resulting in faithful preservation of predicted rRNA structures at both secondary and tertiary levels. Third, sequence motifs thought important for rRNA processing are present in both the 5′ and the 16S-23S transcribed spacers. Fourth, a Northern blot analysis detected the presence of both 16S and 23S rRNAs coded by rrnB in the cell.

Two theories have been put forward to explain the origin of distinct types of rRNA genes in a single genome (28, 37). An organism either evolves different types of a gene via divergent evolution after gene duplication or acquires a gene from another species through lateral gene transfer. One important piece of evidence supporting the latter theory would be a demonstration of a closer relatedness of one type of a gene to a homologous gene from a different species than to the other type in the same genome (18, 29, 29). In this study, we obtained evidences that strongly implicate a close evolutionary relatedness between the rrnB of T. chromogena and the rrnA of T. bispora. First, the two operons share features that distinguish them from T. chromogena type I operons, such as a short 16S-23S ITS and the lack of a 5S rRNA gene. Second, these two operons share many nucleotide signatures including insertion-deletions throughout the entire length of the operon that cannot be accounted for by independent evolution. Of particular interest is the presence in both 16S and 23S genes of T. chromogena rrnB of long segments that are nearly identical to the corresponding regions of T. bispora rrnA but considerably different from the same region of T. chromogena type I operons. Third, phylogenetic analyses on the basis of both 16S and 23S rRNA sequences demonstrated the association of the genes of T. chromogena rrnB with those of T. bispora, forming a clade rather distant from the one that contains solely the genes of the type I rrn operons of T. chromogena. The latter two evidences were not immediately obvious. The 16S and 23S rRNA genes of T. chromogena rrnB share, after all, more nucleotide signatures with their counterparts of the type I operons of the same organism, and the positions of rrnB genes in the phylogenetic trees were found to change in an outgroup-dependent manner. Only after close examination of a multiple sequence alignment was a mosaic nature of T. chromogena rrnB genes discovered (see Results). This discovery sheds light on our understanding of the origin and evolution of the operon and clarifies on the uncertain relationship between different rRNA genes of T. chromogena and T. bispora noted in the phylogenetic analyses.

Here, we propose a model to explain the origin and evolution of the rrnB operon in T. chromogena. T. chromogena or its immediate ancestor acquired a T. bispora rrnA-like operon from T. bispora or a closely related actinomycete via horizontal gene transfer. In the new host, the newly introduced operon underwent amelioration through biased gene conversion (13, 22) as well as mutations under the same directional pressure affecting all the genes of the recipient genome (22). Over time, the horizontally transferred operon became increasingly similar to the rRNA genes of the recipient organism. Multiple conversion events involving different segments of the operon resulted in the mosaic nature of the genes of T. chromogena rrnB. Obviously, this amelioration process obscures the evolution history of the horizontally transferred operon recorded in its nucleotide sequence and accounts for the uncertain relationship of T. chromogena rrnB genes to other members of T. chromogena and T. bispora rrn operons observed in the phylogenetic analyses. Congruous to this model, the rRNA genes of T. chromogena rrnF and T. bispora rrnA, which evolved independently in two organisms, share much fewer nucleotide signatures that are distributed in a random fashion. In addition, the absolute thermophilic growth characteristic of both T. chromogena and T. bispora indicates that they may inhabit the same ecological niche, thus providing opportunities of cell contact for the exchange of genetic material. This model explains well the distinct sequence and structural features of T. chromogena rrnB operon and its relationship with other rrn operons of both organisms. Though divergent evolution following gene duplication remains a possible cause of the two types of operons, it does not explain the segmental distribution in T. chromogena rrnB of nucleotide signatures characteristic of different parts of rrn operons belonging to two different organisms.

Horizontal gene transfer plays a major role in organismal evolution, especially so towards early stages of evolution (7, 39). Though many conserved genes have been used to infer organismal phylogeny at all taxonomic levels, there has been generally a lack of consistency (7, 39). The most likely explanation of the conflicting phylogenies appears to be the horizontal transfer of genes. Perhaps, horizontal transfer of rRNA genes is less likely than that of other genes due to the stringent functional constraint, but should they be exceptions? This study provides strong evidences for the horizontal transfer of an entire rrn operons between two organisms with a distant relationship. The implication is profound concerning the popular use of rRNA sequences in the inference of organismal relationships. Sneath (33) also speculated on the possibility of interspecific transfer of rRNA genes followed by recombinations with homologous genes in the recipient genome to explain the anomalous distribution of nucleotide signatures in the 16S rRNA sequences of some Aeromonas species. It is of fundamental importance to understand how widespread this phenomenon exists in nature. The increasing number of reports describing the presence of distinct types of rRNA genes in a single genome should cause some concerns (references 3, 10, 25, 27, and 37 and the present study). Also, lower than 2% sequence dissimilarity is rather common (4, 5, 21, 23, 30). In future studies of rRNA gene heterogeneity, more attention should be paid not only to the level of sequence dissimilarity but also to the distribution of base substitutions through alignment with related sequences. Such analysis may reveal the origin of the heterogeneity and provide useful information about the evolution of both rRNA genes and the organisms of concern.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology.

We thank Sydney Brenner for his comments and suggestions about the manuscript. We thank Alice Tay for determining the DNA sequences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R I, Lugwig W, Schleifer K H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brosius J, Palmer J J, Kennedy J P, Noller H F. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 16S ribosomal gene from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4801–4805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carranza S, Giribet G, Riberat C, Baguna J, Riutort M. Evidence that two types of 18S rDNA coexist in the genome of Dugesia (Schmidtea) mediterranea (Platyhelminthes, Turbellaria, Tricladida) Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:824–832. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayton R A, Sutton G, Hinkle P S, Jr, Bult C, Fields C. Intraspecific variation in small subunit rRNA sequences in GenBank: why single sequences may not adequately represent prokaryotic taxa. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:595–599. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-3-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.East A K, Thompson D E, Collins M D. Analysis of operons encoding 23S rRNA of Clostridium botulinum type A. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:8158–8162. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8158-8162.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;46:159–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng D F, Cho G, Doolittle R F. Determining divergence times with a protein clock: update and reevaluation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13028–13033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groisman E A, Saier M H, Jr, Ochman H. Horizontal transfer of a phophatase gene as evidence for mosaic structure of the Salmonella genome. EMBO J. 1992;11:1309–1316. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groisman E A, Sturmoski M A, Solomon F R, Lin R, Ochman H. Molecular, functional, and evolutionary analysis of sequences specific to Salmonella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1033–1037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunderson J H, Sogin M L, Wollet G, Hollingdale M, de la Cruz V F, Waters A P, McCutchan T F. Structurally distinct, stage-specific ribosomes occur in Plasmodium. Science. 1987;238:933–937. doi: 10.1126/science.3672135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurtler V, Stanisich V A. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology. 1996;142:3–16. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutell R G, Larsen N, Woese C R. Lessons from an evolving rRNA: 16S and 23S rRNA structures from a comparative perspective. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:10–26. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.10-26.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillis D M, Moritz C, Porter C A, Baker R J. Evidence for biased gene conversion in concerted evolution of ribosomal DNA. Science. 1990;251:308–310. doi: 10.1126/science.1987647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Z, Fasco M J, Kaminsky L S. Optimization of DNase I removal of contaminating DNA from RNA for use in quantitative RNA-PCR. BioTechniques. 1996;20:1012–1020. doi: 10.2144/96206st02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jemiolo D K. Processing of prokaryotic ribosomal RNA. In: Zimmermann R A, Dahlberg A E, editors. Ribosomal RNA: structure, evolution, processing, and function in protein biosynthesis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1995. pp. 453–490. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Monro H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 17.King T C, Sirdeskmukh R, Schlessinger D. Nucleolytic processing of ribonucleic acid transcripts in prokaryotes. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:428–451. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.428-451.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroll J S, Wilks K E, Farrant J L, Langford P R. Natural genetic exchange between Haemophilus and Neisseria: intergeneric transfer of chromosomal genes between major human pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12381–12385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stacketbrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Sequencing and hybridization techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawrence J G, Ochman H. Amelioration of bacterial genome: rates of change and exchange. J Mol Evol. 1997;44:383–397. doi: 10.1007/pl00006158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liefting L W, Anderson M T, Beever R E, Gardner R C, Forster R L. Sequence heterogeneity in the two 16S rRNA genes of Phormium yellow leaf phytoplasma. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3133–3139. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3133-3139.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long E O, Dawid I B. Repeated genes in eukaryotes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:727–764. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.003455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maden B E H, Dent C L, Farrell T E, Garde J, McCallum F S, Wakeman J A. Clones of human ribosomal DNA containing the complete 18S-rRNA and 28S-rRNA genes. Biochem J. 1987;246:519–527. doi: 10.1042/bj2460519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarthy A J. Thermomonospora and related genera. In: Williams S T, Sharpe M E, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 4. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1989. pp. 2552–2572. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCutchan T F. Ribosomal genes of Plasmodium. Int Rev Cytol. 1986;99:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61429-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mevarech M, Hiesch-Twizer S, Goldman S, Yakobson E, Eisenberg H, Dennis P P. Isolation and characterization of the rRNA gene clusters of Halobacterium marismortui. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3479–3485. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3479-3485.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mylvaganam S, Dennis P P. Sequence heterogeneity between the two genes encoding 16S rRNA from the halophilic archaebacterium Halobacterium marismortui. Genetics. 1992;130:399–410. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson K, Selander R K. Intergeneric transfer and recombination of the 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase gene (gnd) in enteric bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10227–10231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reischl U, Feldmann K, Naumann L, Gaugler B J, Ninet B, Hirschel B. 16S rRNA sequence diversity in Mycobacterium celatum strains caused by presence of two different copies of 16S rRNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1761–1764. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1761-1764.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbour-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santer M, Dahlberg A E. Ribosomal RNA: an historical perspective. In: Zimmermann R A, Dahlberg A E, editors. Ribosomal RNA: structure, evolution, processing, and function in protein biosynthesis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1995. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sneath P H A. Evidence from Aeromonas for genetic crossing-over in ribosomal sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:626–629. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-3-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Syvanen M. Horizontal gene transfer: evidence and possible consequences. Annu Rev Genet. 1994;28:237–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.28.120194.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van de Peer Y, Chapelle S, Wachter R D. A quantitative map of nucleotide substitution rates in bacterial rRNA. Nucleic Acid Res. 1996;24:3381–3391. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.17.3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Zhang Z S, Ruan J S. A proposal to transfer Microbispora bispora (Lechevalier 1965) to a new genus, Thermobispora gen. nov., as Thermobispora bispora comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:933–938. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Zhang Z S, Ramanan N. The actinomycete Thermobispora bispora contains two distinct types of transcriptionally active 16S rRNA genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3270–3276. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3270-3276.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woese C R. Bacterial evolution. Microbial Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woese C R. The universal ancestor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6854–6859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woese C R, Kandler O, Wheelis M L. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Z S, Wang Y, Ruan J S. Reclassification of Thermomonospora and Microtetraspora. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:411–422. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-2-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]