Abstract

Introduction

The perforation of the bowel as the first presentation of inflammatory bowel disease is a rare occurrence reported in about 0.15–3 % of the literature and is especially unusual in young patients <30 years of age. It is a serious event with most of the perforations occurring on the ileum. This article describes a unique case of a 20-year-old female patient who presented with perforated ileum due to Crohn's disease as an initial presentation operated at a private surgical center.

Case presentation

We present a case of a previously asymptomatic 21-year-old female presenting with intestinal perforation secondary to Crohn's disease for the first time.

The patient presented with crampy abdominal pain and frequent bilious vomiting of 3 days duration. She also had a high-grade fever and abdominal distension. WBC was 24,000 and an abdominal CT scan showed perforation of the bowel consistent with Crohn's Disease. Ruling out other etiologies perforated viscous secondary to query Crohn's Disease was entertained and laparotomy revealed 2 × 2 cm perforation on the anti-mesenteric border of the terminal ileum. The perforated segment was resected primary anastomosis was performed.

Following surgery, the patient was discharged symptom-free and linked to the Gastroenterology unit after a biopsy confirmed Crohn's disease. She was started on Prednisolone and Azathioprine exactly a month after her surgery. Her 6-month follow-up is smooth.

Conclusion

Presentation of bowel perforation as an initial feature of Crohn's Disease is a rare phenomenon. Adequate resuscitation followed by emergency laparotomy with primary resection and anastomosis could be life-saving for a hemodynamically stable patient.

Abbreviations: AZA, azathioprine; 6-MP, 6 mercaptopurine; anti-TNF, anti-tumor necrosis factor; CD, Crohn's disease; ALT, Alanine Aminotransferase; AST, Aspartate Aminotransferase; ALP, Alkaline Phosphatase; BPM, Beats Per Minute; BUN, Blood Urea Nitrogen; Hgb, hemoglobin; Hct, Hematocrit; MCV, Mean Corpuscular Volume; RBC, Red Blood Cells; WBC, White Blood Cells

Keywords: Crohn's perforation, Crohn's in Ethiopia, Ileal perforation

Highlights

-

•

The perforation of the bowel as the first presentation of inflammatory bowel disease is rare.

-

•

This article describes a unique case of a 20-year-old female patient who presented with perforated ileum due to Crohn’s disease as an initial presentation.

-

•

Presentation of bowel perforation as an initial feature of Crohn’s Disease is a rare phenomenon.

-

•

Adequate resuscitation followed by emergency laparotomy with primary resection and anastomosis could be life-saving for a hemodynamically stable patient.

1. Introduction

Crohn's disease is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract and is increasing in incidence worldwide. Typical clinical scenarios are young patients with abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue [1]. Intestinal perforation as an initial complication of Crohn's disease is a rare but serious event with most of the perforations occurring on the ileum [2].

This article describes a unique case of a 20-year-old female patient who presented perforated ileum due to Crohn's disease as an initial presentation operated at a private surgical center. This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [3].

2. Case presentation

This is a case report of a 20-year-old female patient who presented to a private surgical center with severe crampy abdominal pain and frequent bilious vomiting of 3 days duration. She also had a high-grade fever and abdominal distension. She had no diarrhea, loss of weight, joint pain, cough, chest pain, or night sweating. She has no previous history of abdominal surgery or similar illness. She is single, lives with her parents, and has a sister. There are no known medical illnesses that run in the family. She has no history of tobacco smoking or substance abuse.

At presentation, her blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, pulse rate was 120 Beats per Minute (bpm), respiratory rate was 18 per minute, and the temperature was 38.2 °C axillary. She was acutely sick looking (in pain); not in cardiorespiratory distress. She had a dry tongue and buccal mucosa. Her chest was clear and resonant. S1 and S2 cardiac sounds were well heard. The abdomen was slightly distended, moved with respiration, flanks were full, and hernia sites were free. Palpation revealed a tense abdomen with an area of deep tenderness around the peri-umbilical region. Bowel sounds were 5 per minute. Digital rectal examination revealed scanty stool with no blood on the examining finger. The patient was conscious and her neurological examination was normal.

With the initial impression of generalized peritonitis secondary to rule out a perforated appendix, the patient was investigated.

Her White Blood Cell count (WBC) 24,500 mcL, with Neutrophil 90.1 %, Red Blood Cells (RBC) 3.58 mcL, hemoglobin (Hgb) 11.8 g/dL, Hematocrit (Hct) 32.26 %, Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) 89.1 fL, Platelet 204 × 103, Creatinine 0.6, Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) 30, Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) 28, Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) 24, Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) 48, Albumin 4.3, total Bilirubin 1.1 and serum Albumin 3.6.

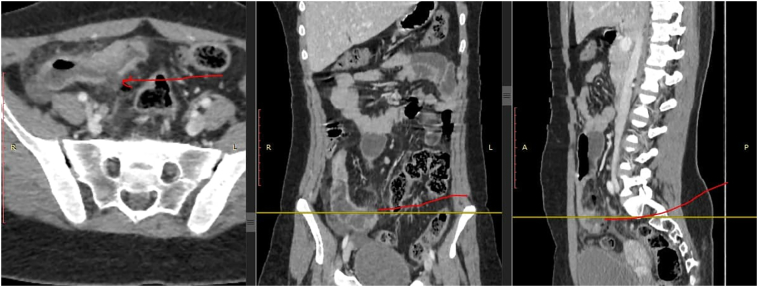

Abdominal CT scan was performed: it revealed circumferential long segment mural wall, edematous (infectious type) terminal ileal thickening and abnormal enhancement with surrounding inflammation, reactive mesenteric lymphadenopathy with frank anti-mesenteric border wall discontinuity with perforation and free peritoneal fluid likely secondary to a perforated terminal ileitis likely secondary to Crohn's disease (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(A) Coronal slice of computed tomography (CT) image of small bowel perforation at distal ileum.

(B) Sagittal slice of CT image of small bowel perforation at distal ileum.

3. Management and outcomes

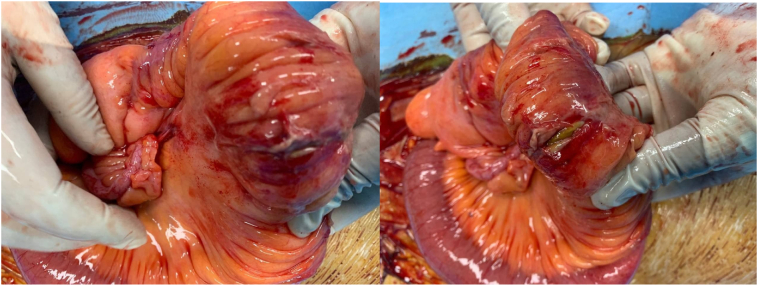

With the diagnosis of perforated terminal ileum secondary to Crohn's disease, the patient was taken to the OR for emergency laparotomy. During laparotomy, the anti-mesenteric border of the terminal ileum was perforated 60 cm from the ileocecal valve with typical Crohn's disease fat stranding of the ileum. The ileal region is full of creeping fat up to its serosa (Fig. 2). Otherwise, the small bowel, large bowel, cecum, appendix, and reproductive organs were grossly normal.

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative image showing perforated ileum with mesenteric fat crepitation.

En-bloc resection of the perforated segment and hand sewed single layer end to end anastomosis of the normal bowel in a continuous fashion was done with vicryl 2/0. Postoperatively patient was put on Ceftriaxone 1 g IV bid and Metronidazole 500 mg IV tid and was discharged symptom-free after 7 days. The patient was put on Metronidazole 500 mg PO TID for three months before discharge.

Culture sent from ileal specimen revealed normal gut flora. Histology of the specimen showed perforation of the anti-mesenteric wall and into peritoneal space, with granulomatous inflammation suggestive of Crohn's disease.

She was linked to a Gastroenterologist and after the biopsy report confirmed Crohn's ileitis, she started Prednisolone 60 mg PO per day, cotrimoxazole 960 mg PO per day, and Azathioprine 125 mg PO per day. Patient is on her 6th month post op recovering smoothly.

4. Discussion

In this case, it is quite notable that the patient reported no symptoms until her first presentation to the hospital with a perforated bowel. Free perforation of the bowel as the first presentation of Crohn's disease is rare with an incidence of 3.4 %, with 86.1 % of perforations involving the ileum [4].

It is accepted that Western and Eastern phenotypes do differ: with patients from Eastern populations leaning towards a male predominance, ileocolic disease, and a lower association with cigarette smoking, familial aggregation, and extra-intestinal disease compared to Western populations [5].

Cardinal manifestations of patients with Crohn's Disease are abdominal pain, diarrhea with or without gross bleeding, fatigue, and weight loss. Features of Trans-mural inflammation like stricture, fistula, perforation, hemorrhage, abscess, perianal disease are rare manifestations of Crohn's disease but would necessitate surgery as their mainstay of management. In 1–16 % of patients undergoing surgery for Crohn's disease, bowel perforation was the main indication [4].

The main aspect of surgical management is to limit the amount of bowel resected as much as possible to avoid complications like short bowel syndrome [4]. Patients who are hemodynamically unstable or who have edematous bowels, significant intrabdominal contamination from perforation, or other risk factors such as Malnutrition or chronic glucocorticoid use should have a diverting stoma rather than a primary anastomosis [6].

Crohn's disease recurs frequently after operative management. In several studies, the endoscopic recurrence rate was as high as 80 % one year after surgery; the clinical recurrence rate was 10 to 15 % per year. Between 70 and 90 % of patients will require surgery during their lifetime, with up to 39 % requiring repeated surgery [4]. Risk factors for recurrence are smoking, genetic (NOD2/CARD15 mutation), shorter preoperative disease duration, presence of proximal gastrointestinal (duodenum and jejunum) diffuse disease, prior surgery for Crohn's disease, first presentation with fistula or perforation are some [7], [8].

The main management of Crohn's disease is multidisciplinary in nature. Collaboration with the aim of reducing symptoms and maximizing patient quality of life among different disciplines is inherent [4].

Prevention of postoperative recurrence of CD requires determining which patients will benefit from early medical therapy and which patients should be monitored clinically, thereby avoiding the risks of therapy [9]. Patients with a smoking history, patients younger than age 30 years, perforating/penetrating/fistulizing/long segment inflammatory disease, history of ≥2 surgeries for CD, shorter disease duration prior to surgery characterizes higher-risk patients [7].

For patients at higher risk, it is suggested initiate immunosuppressive therapy postoperatively, and the approach is the following:

For higher risk, treatment naive patients (i.e., those who did not fail treatment with either AZA/6-MP or anti-TNF prior to surgery), begin Azathioprine or 6-Mercaptopurine (AZA/6-MP) within two to eight weeks following bowel resection [10]. If the patient can tolerate Metronidazole, it is also suggested a three-month course of antibiotics in combination with AZA/6-MP [7].

Postoperative therapy with an anti-TNF agent or AZA/6-MP reduces the risk of clinical recurrence [11].

Ileocolonoscopy is performed at 6 to 12 months and if endoscopic recurrence is found despite medical therapy, treatment can be intensified with the following options [12]:

For patients receiving monotherapy with AZA/6MP, anti-TNF agent can be started with or without discontinuation of AZA/6-MP.

For those patients already taking a biologic agent, options include increasing the dose of the anti-TNF agent, changing to a different anti-TNF agent, or adding AZA/6-MP to the anti-TNF regimen.

If the ileocolonoscopy at 6 to 12 months after surgery shows no endoscopic recurrence (i.e. Rutgeerts score i0 or i1), the patient can be monitored clinically on this regimen and surveillance ileocolonoscopy is suggested in one to three years.

5. Conclusion

Presentation of bowel perforation as an initial feature of Crohn's Disease is a rare phenomenon. Adequate resuscitation followed by emergency laparotomy with primary resection and anastomosis could be life-saving for a hemodynamically stable patient.

5.1. Medications

Postoperative therapy with an anti-TNF agent reduces the risk of both clinical and endoscopic recurrence (OR 0.51, 95 % CI 0.28–0.94, and OR 0.24, 95 % CI 0.15–0.39, respectively) [5].

Infliximab has been demonstrated to lower endoscopic and possibly clinical recurrence rates in postoperative CD [13].

Treatment with antibiotics like Metronidazole is generally safe but side effects may limit their use. Studies have shown that disease recurrence develops only when the mucosa is re-exposed to luminal contents, thus indicating that bacteria may have a role in recurrence; this provides a rationale for the use of antibiotics [14].

Data suggest that Mesalamine prophylaxis is associated with a modest benefit in preventing relapse [15].

Author's contributions

RT will be the corresponding Author and operating surgeon. KT analyzed and interpret the radiological images. BE assisted with proof reading, literature review and paper development.

Funding

No funds were used to write this case report.

Availability of data and materials

All the images and detailed information of this case are available at Hospital patient record and can be submitted upon request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical board review of the hospital has approved the publication of this case report. Facial images describing the patient discussed will not be used. The patient has provided written informed consent to get the case published.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Guarantor

RT will be the guarantor of this article.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Torres J., Mehandru S., Colombel J.-F., Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1741–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huerta C.T., Ribieras A.J., Kodia K., Yeh D.D., Kerman D., Byers P. Small intestinal perforation secondary to necrotizing enteritis—an under-recognized complication of Crohn’s disease. Am. Surg. 2022 doi: 10.1177/00031348211054521. 00031348211054521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Kerwan A., Thoma A., et al. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J.H., Tey T.T., Foo F.J., Koh F. Perforated viscus as first presentation of Crohn’s disease: a case report. Journal of Surgical Case Reports. 2021;2021(9):rjab415. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjab415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee R., Pal P., Hilmi I., Ghoshal U.C., Desai D.C., Rahman M.M., et al. Emerging IBD demographics, phenotype and treatment in South Asia, South-East Asia and Middle East: preliminary findings from the IBD-emerging nations' consortium. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022 doi: 10.1111/jgh.15801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myrelid P., Söderholm J.D., Olaison G., Sjödahl R., Andersson P. Split stoma in resectional surgery of high-risk patients with ileocolonic Crohn's disease. Color. Dis. 2012;14(2):188–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penner R.M., Tandon P. UpToDate; 2021. Management of Crohn Disease After Surgical Resection. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernell O., Lapidus A., Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and postoperative recurrence in Crohn's disease. Ann. Surg. 2000;231(1):38. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Cruz P., Kamm M.A., Prideaux L., Allen P.B., Desmond P.V. Postoperative recurrent luminal Crohn's disease: a systematic review. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012;18(4):758–777. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutgeerts P., Van Assche G., Vermeire S. Optimizing anti-TNF treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(6):1593–1610. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozuch P.L., Hanauer S.B. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a review of medical therapy. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2008;14(3):354. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen G.C., Loftus E.V., Hirano I., Falck-Ytter Y., Singh S., Sultan S., et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the management of Crohn's disease after surgical resection. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(1):271–275. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regueiro M., Feagan B.G., Zou B., Johanns J., Blank M.A., Chevrier M., et al. Infliximab reduces endoscopic, but not clinical, recurrence of Crohn's disease after ileocolonic resection. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(7):1568–1578. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nitzan O., Elias M., Peretz A., Saliba W. Role of antibiotics for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22(3):1078. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i3.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford A.C., Khan K.J., Talley N.J., Moayyedi P. 5-aminosalicylates prevent relapse of Crohn's disease after surgically induced remission: systematic review and meta-analysis. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. 2011;106(3):413–420. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the images and detailed information of this case are available at Hospital patient record and can be submitted upon request.