Summary

The harmful impacts of algorithmic decision systems have recently come into focus, with many examples of machine learning (ML) models amplifying societal biases. In this paper, we propose adapting income inequality metrics from economics to complement existing model-level fairness metrics, which focus on intergroup differences of model performance. In particular, we evaluate their ability to measure disparities between exposures that individuals receive in a production recommendation system, the Twitter algorithmic timeline. We define desirable criteria for metrics to be used in an operational setting by ML practitioners. We characterize engagements with content on Twitter using these metrics and use the results to evaluate the metrics with respect to our criteria. We also show that we can use these metrics to identify content suggestion algorithms that contribute more strongly to skewed outcomes between users. Overall, we conclude that these metrics can be a useful tool for auditing algorithms in production settings.

Keywords: attention inequality, inequality metrics, ranking and recommendation, responsible machine learning, AI ethics

Highlights

-

•

In this dataset, we find the top 1% of authors receive ∼80% of all views of Tweets

-

•

Inequality metrics work well for understanding disparities in outcomes on social media

-

•

Out-of-network impressions are more skewed than in-network impressions

-

•

The top X% share metrics perform the best relative to our criteria

The bigger picture

In recent years, many examples of the potential harms caused by machine learning systems have come to the forefront. Practitioners in the field of algorithmic bias and fairness have developed a suite of metrics to capture one aspect of these harms: namely, differences in performance between different demographic groups and, in particular, worse performance for marginalized communities. Despite great progress made in this area, one open question became particularly prominent for industry practitioners: how do you capture such disparities if you do not have reliable demographic data or choose not to collect them due to privacy concerns? You have probably heard statistics like “the top 1% of people own X% share of the wealth,” and this work applies those notions to levels of engagement on Twitter. We use inequality metrics to understand exactly how skewed engagements are on Twitter and dig deeper to isolate some of the algorithms that may be driving that effect.

You have probably heard statistics like “the top 1% of people own X% share of the wealth,” and this work applies those notions to levels of engagement on Twitter. This paper uses inequality metrics to understand exactly how skewed engagements are on Twitter and dig deeper to isolate some of the algorithms that may be driving that effect.

Introduction

Content recommendation algorithms live at the heart of social media platforms, with machine learning models recommending and ranking everything, from accounts to follow to topics of interest and the actual posts that appear in a user’s feed. Over the past decade, it has become clear that attention and engagement on social media platforms is highly concentrated, with a small set of users receiving the lion’s share of attention.1,2 Understanding this skew is crucial, not only for those seeking to monetize content on the internet, but, more importantly, for historically oppressed voices and social movements who have used social media to organize and find their communities. In addition, users’ trust can erode over time if they feel they are posting “into the void,” with no one seeing their content.3

At the same time, there has been a newly increased focus on the potential harms caused by machine learning systems.4, 5, 6 A large suite of fairness metrics has emerged, mainly focused on comparing disparities in model performance across demographic groups. In the case of classification models, these metrics often compare performance metrics such as false positive rate or accuracy.7, 8, 9 For ranking models, there has been a focus on differences in level of exposure between groups.10, 11, 12 While significant advancements have been made, these group-comparison metrics still suffer from some drawbacks. In practice, there are many hurdles to operationalization of these metrics. First, they require knowledge of a sensitive attribute in order to identify potentially disadvantaged groups. Such demographic information is often noisy or deliberately not collected due to privacy or legal concerns. Second, they are largely targeted at analyzing single classification or ranking models. End-user outcomes in production systems are usually the product of a large, interconnected system of models that feed into one another and are continually affected by (and adapting to) human behavior. In industry settings, these issues make metrics such as demographic parity difficult to implement in practice. As such, there is a need to supplement existing metrics with others that take a broader view of system outcomes, focusing on bigger picture disparity measurement without considering a specific model or requiring demographic information to be properly defined.

In this work, we study the usability of a suite of metrics originally used by economists to quantify income inequality, which we refer to as “distributional inequality metrics.”13 These inequality metrics help complement group fairness metrics, since they do not rely on knowledge of demographic information and focus on distribution of outcomes across an entire population. We evaluate, both qualitatively and quantitatively, how applicable these metrics are to the measurement of unequal outcomes on social media. Specifically, we:

-

•

define a set of desirable criteria for metrics, attempting to capture skews in outcomes in real-world settings;

-

•

quantify skews in engagements with posts on the Twitter algorithmic timeline, specifically focused on disparities between the authors;

-

•

identify algorithmic sources of distributional inequality using the proposed metrics, observing a connection between number of followers and exposure that suggests that out-of-network content suggestions are more skewed for users with fewer followers;

-

•

use the empirical results from applying the metrics in the cases above to evaluate them in the context of the desirable criteria we set forth.

Prior work

Many researchers have investigated the application of principles from economics to measure algorithmic fairness. In one recent study, a set of generalized entropy measures and inequality indices was used to quantify differences in group and individual fairness.14 Another work created puppet Twitter accounts and used the Gini index to compare the diversity of authors seen by accounts using the Twitter algorithmic timeline versus those that were using a simple chronological feed of content.15 Researchers at LinkedIn showed that the Atkinson index could be used to promote more equitable design choices when used in A/B testing.16 More generally, there has been much work by economists and social scientists to frame the questions surrounding algorithmic fairness.17,18 One particularly relevant work emphasizes that equality and power are often better ways to frame questions of algorithmic harms, and it provides a basis for new metrics for computing quantities relevant to these issues from economic theory.19

Outside of the field of economics, there has also been a focus on the fairness of ranking and recommendation, which often require different metrics compared with classification models. Several studies frame the fairness of rankings in terms of the allocation of exposure,10, 11, 12,20, 21, 22 highlighting the need for metrics that capture disparities in attention garnered by creators in ranking contexts. It has also been shown that the notion of individual fairness23 can be applied to ranking models, extending the previous work on exposure to enforce that similar items from minority and majority groups appear together.24 A recent paper summarizes the literature on these metrics and does a systematic review and mathematical unification.25 While these metrics are quite useful and relevant, they all rely on the presence of group labels for the providers of items to be ranked by the ranking model.

Finally, there is some work that considers system-level outcomes of ranking systems rather than individual models, particularly in the context of political bias in search results26 and gender bias in resume rankers.27 These studies come closest to our current work, as they specifically study disparities in outcomes of larger-scale algorithmic-driven systems.

Our work is unique compared with previous work in multiple respects. First, we undertake a systematic evaluation of a number of different demographic-free inequality metrics, many of which have not been studied previously in the context of recommendation systems or social media. Second, we apply the measurement of these metrics to flag specific algorithmic sources of skew in end-user outcomes, directly demonstrating how they can be used in a real-world operational setting on production-scale datasets.

Results

Moving from measuring model-level fairness to system-level outcomes

While current group-based fairness metrics are effective at identifying imbalances between demographics in model performance, they do not capture how these imbalances ultimately cascade and disproportionately harm or benefit end users. Focusing on end outcomes allows us to recenter our measurements on notions of social hierarchy, power distribution, and equality.19,28 Researchers at LinkedIn have previously advocated for a similar approach by incorporating the Atkinson index as a measure of inequality of outcomes during A/B testing, and in this work we hope to generalize that approach to a broader set of social media use cases.16 Diagnosing these issues is the first step toward what has been proposed as a more substantive approach to fairness, with the end goal being “reforms [that] can address the forms and mechanisms of inequality that were identified” and a reckoning with the algorithmic role in these mechanisms.28

Before embarking on our tests of inequality metrics, we must first consider the normative assumptions that come with the use of these measures. With group-based metrics, the normative assumption is relatively clear: we try to minimize disparities between demographic groups so that the models do not disproportionately harm already-marginalized populations. In the case of inequality, the normative prescription about what is “desirable” is not as clear. We do know that the “perfect” social media world is not one with “no inequality,” because there is a natural variation of interest in specific accounts and Tweets. For example, the authors of this paper might like to have as many views on Twitter as popular accounts like Lady Gaga or Barack Obama, but such an allocation of attention would not be fair considering the relative popularity of these accounts. At the same time, there is the very real problem that many creators on Twitter feel that their content is not seen. One study3 from Pew Research Center found that 67% of respondents thought that very few people saw their content, while 11% reported that nobody saw their content. The “ideal state” of a recommendation ecosystem like Twitter is one that is aligned with users’ preferences as both producers and consumers. That is, consumers see content they want to see and producers have reach commensurate with the quality of their content. We do not know what the optimal value of inequality would be for this state, and attempting to calculate that is out of the scope of this work. However, we do know that attention is heavily skewed currently and popular accounts get significantly more engagement than others. Therefore, the goal of this work is to introduce metrics that can measure the current state of attention inequality and potentially be used to understand in what direction new features move these measures. When used in combination with other metrics more related to overall performance, user retention, and satisfaction, they should be able to help practitioners understand when they reach alignment with user preferences. In short, we know, based on user feedback, that the current level of inequality is likely too high, and by introducing and vetting these metrics we can create tools for practitioners to better understand the effects of the features they ship. These metrics are influenced by both between-group disparities and within-group disparities, so they are able to capture differences in outcomes between groups while also taking into account differences between members within a particular group.

As mentioned above, we focus on disparities in the distribution of different types of engagements on Twitter as a concrete, measurable system-level outcome. While engagement is most definitely not the only measure of value gained from the platform,29 those sharing content on platforms with recommendation systems depend crucially on how they are ranked. Within social media, mobilizing social movements, showcasing work while searching for jobs, or building an audience for one’s content are all examples of use cases heavily driven by level of exposure. On other platforms, level of exposure can be a direct tie to revenue, such as for sellers on eBay and Amazon, artists on Spotify, or actors and producers on Netflix. Therefore, we see the number of engagements, a measure of how much a user’s content is exposed to others, as a good starting point for assessing the usefulness of these metrics.

In this frame of mind, it is important to acknowledge that many of the mechanisms of inequality present in algorithm-driven systems will not be identifiable by metrics alone. Measuring the value of a metric inherently assumes that the disparity or harm in question is quantitatively measurable. Many classes of harms will not be capturable with a metric. This is an additional motivation for exploring different types of engagement as a testing ground, since those outcomes are quantifiable and therefore disparities should be measurable by an actionable metric. At the same time, we note that any absence of disparities measured by this metric does not imply that a system is perfectly fair, but rather that there was negligible measurable inequality for the specific quantity being studied.

What makes a good system-level metric?

To evaluate them thoroughly, we must first define desirable criteria for metrics attempting to capture gaps in user experiences. We classify these desirable criteria in three categories: theoretical, qualitative, and empirical. Theoretical criteria are inherent mathematical properties that may be useful when deploying the metric. Qualitative criteria are criteria that are subjective evaluations of the metric. Empirical criteria are criteria for which we can use data to measure their efficacy. We evaluate metrics with respect to the following attributes, all of which contribute to their implementability in an operational context.

Theoretical criteria

Some desirable mathematical properties for criteria have been enumerated in previous economics literature,30 as well as LinkedIn’s study of the Atkinson index.16 These include the following:

-

•

Population invariance: because numbers of users frequently fluctuate, and we may want to compare between subgroups on the platform, the metric should have the same meaning for populations of different sizes.

-

•

Adjustability: the metric should allow practitioners to focus on different percentiles of the distribution, as a non-adjustable metric may not weight segments of the distribution appropriately for the application area being studied.

-

•

Scale invariance: if every value in the population is multiplied by a constant factor, the value of the metric should remain equal to its previous value.

-

•

Subgroup decomposability: the metric should be easily calculable in terms of values of the metric computed on subgroups of the population.

Qualitative criteria

-

•

Interpretability: changes in the metric should be understandable by non-experts.

-

•

User focus: the metric should be directly tied to real people’s experiences and measured in units that are easily translated into a description of a property of that population.

Empirical criteria

-

•

Stability: if resampling with a different population, the metric should have a similar value for similar distributions.

-

•

Effect size: when there are changes in the skew of the distribution, differences in the metric should be large enough to be distinguishable. Said another way, distributions that are very different should show a large dynamic range in values of the metric.

Distributional inequality metrics: Definitions

In this work, we have chosen to focus on metrics that were originally used to measure the concentration of income distribution in economics, since this family of metrics is already concerned with measuring disparities across a population. These metrics capture the skew or top heaviness of a distribution and can be applied to any set of non-negative input values. Table 1 shows the mathematical definitions of each metric we consider. The metrics we evaluate in this study include the following:

-

•

Gini index: the Gini index can be defined as the mean absolute difference between all distinct pairs of people in the population divided by the mean value over the population.31,32 In essence, it is a measure of how pairwise differences in income compare with the average income. It ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating perfect equality and one indicating a totally concentrated distribution.

-

•

Atkinson index: the Atkinson index was introduced to address some limitations of the Gini index, namely, that many believed it did not adequately weight those in the low part of the population.33 Atkinson introduces a new “aversion to inequality” parameter, ε, that explicitly allows for adjusting the weight of the low end of the distribution. It also ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more skew. As , the value of the Atkinson index approaches 1. This is because as we weigh the low end of the distribution more, any non-equal distribution will be considered more and more disparate.

-

•

Percentile ratio: a percentile is the value at which some percentage of people have incomes less than or equal to that value. For example, if the value of the 20th percentile of a distribution is $100, then 20% of people make less than or equal to $100. The percentile ratio is defined as the ratio of two different percentile values. In the economics literature, this is typically used to compare the low and high ends of the distribution, most usually the ratio of the 90th and 10th or the 80th and 20th percentiles.13

-

•

Share ratio: while percentile ratios compare single values at particular positions in the distribution, the share ratio compares cumulative portions of the distribution. For example, the 80/20 share ratio compares the share of wealth held by people in the top 20% (80th percentile and above) of the distribution with those in the bottom 20% (20th percentile and below).

-

•

Percentage share of top or bottom X%: while ratios are useful in capturing the scale of disparities, they do not offer any information about the values that went into the ratio. Sometimes it can be useful to directly report the share of wealth held by the top or bottom of a population. One work has suggested that, while Gini alone is insufficient in capturing differences in countries’ income distributions, a combination of top 10% share, bottom 10% share, and Gini can provide more information about disparities.34

-

•

Percentage of equal share: this percentage is the percentage of people for which the bottom end of the distribution has an equal share (50%) of the wealth compared with the top end of the distribution. For example, if the percentage of equal share were 99%, that would mean that the bottom 99% of people had a share of wealth equal to the top 1%.

-

•

Equivalent to top X%: one way to compare ends of the distribution without requiring ratios is to find equivalences in the distribution. For example, if the top 1% of a population has 30% of the wealth, we can ask what percentage of people at the bottom of the distribution carries the same fraction of wealth. The larger that percentage is, the larger the disparity between the high and the low ends of the distribution.

Table 1.

Inequality metric definitions: Mathematical definitions of distributional inequality metrics

| Category | Metric | Definition | Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entropy | Gini index | A value of 0 means perfect equality | ||

| Atkinson index | is “aversion to inequality;” for , the term divided by μ is defined as the geometric mean of the values ; a value of 0 means perfect equality; index goes to 1 as ;μ is the arithmetic mean of all values | |||

| Ratio | percentile ratio | and are percentiles to compare | ||

| share ratio | ||||

| Tail share | share of top X% | |||

| Equivalence | percentage of equal share | |||

| equivalent to top X% |

is the value for population member i, and K is the total number of members of the population. For notational purposes, we assume that the values are ordered in ascending order (, ). is the index of the value at the p-th percentile.

Many of these metrics are also related to a distribution visualization known as the Lorenz curve, a measure of cumulative fraction of wealth as a function of cumulative population size (see, for example, Figure 1).35 When curves do not intersect, a curve with more area under it indicates a more equitable distribution, and a diagonal line corresponds to the case in which all members of the population receive the same income. See the experimental procedures for details on the visual interpretation of the Lorenz curve, as well as its relationship to the metrics defined above.

Figure 1.

Lorenz curves: Lorenz curves for different types of engagement on Twitter

Lines closer to the dashed black line indicate more equal distributions of engagement. On the left, the more typical linear scale is shown. However, because the distributions are difficult to distinguish, a logarithmic scale is used for the y axis on the right. A small linear portion is included from 0 to 10−6 in order to visualize the point at which the distribution transitions from zero to non-zero values.

For organizational purposes, we can sort the metrics into four different categories. The Atkinson index is part of a family of more generalizable entropy measures,36 and Gini also measures an entropy-like quantity,37 so we will refer to them together as “entropy” metrics. We define the second group as “ratio” metrics, containing the percentile and share ratios. The third group is defined as “tail share” metrics, and it contains the more general non-ratio measures of share of wealth at the top or bottom of the distribution. The final class of metrics is “equivalence” metrics, or those metrics defining percentiles where shares of wealth distribution are equal to one another. Now, having defined these metrics, we measure them on different types of engagements with content on Twitter. We defer discussion of the metrics with respect to the criteria set out above until later sections, in order to be able to evaluate theoretical properties together with empirical and qualitative ones.

Understanding metric behavior on synthetic data

Before applying the proposed metrics to real-world data, we would like to understand what one might expect for the behavior of the metrics, particularly for the empirical criteria of stability and effect size. To do this, we perform experiments on synthetic data sampled from a power law distribution of the following form:38

| (Equation 1) |

Stability of metrics

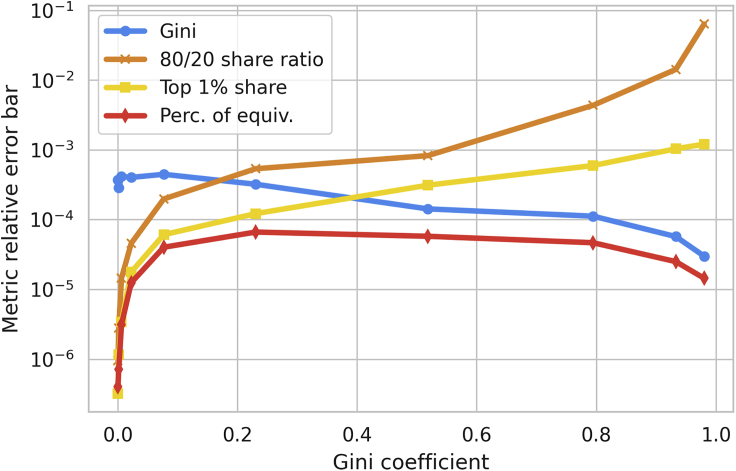

Our first experiment on synthetic data focuses on the stability of metrics. In particular, we would like to understand how much the metrics vary, relative to their value, when the underlying distribution does not change. We choose different values of the parameter a, corresponding to different levels of skew for the distribution. At each a, we sample n = 105 points from the distribution and compute the metrics. After doing these trials 10 times, we compute the mean, μ, and SD, σ, of the metric values across trials and consider the quantity as a measure of the relative stability of the metric. (For this study, we choose one metric from each family specified above. The other metrics in the same family perform similarly, so we omit them for clarity in visualization.) We measure this stability as a function of the overall Gini coefficient of the distribution, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Metric stability: Relative error on metrics as a function of overall skew of the power law distribution (Gini coefficient)

At high Gini values, the 80/20 ratio has the highest relative error (is the least stable), while at low Gini values the Gini is the least stable metric.

At high skews (where social media engagements are more likely to live, given prior work), the share ratio metric is quite unstable. This makes sense, since highly skewed distributions will have low values for the 20% share, which appears in the denominator of the metric. At low skews, the percentile-based metrics are all quite stable, with relative errors from resampling the same distribution on the order of one part in a million. The Gini coefficient, on the other hand, has a larger relative error.

Effect size of changes in the distribution

Our second experiment on synthetic data focuses on the effect size we can expect from the metrics. Here, we fix and sample points. We transfer a fraction of wealth from the richest individual in the population to the poorest and measure the relative change in each metric. This gives us a sense of how responsive the metrics are when there are actual differences between the distributions. The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Metric effect size: Relative change in metric value as a function of how much wealth is transferred from the richest to the poorest individual

First, we compare the relative scales of the effect sizes. In this case, the 80/20 share ratio and top 1% share show larger relative reductions in metric value by an order of magnitude. Next, we consider the shapes of how the metric value changes. The Gini coefficient varies smoothly, as it considers the shape of the entire distribution. The 80/20 share ratio and top 1% share decrease until the wealth transfer gets to the point where the rich individual is no longer in the percentile of interest, at which point we have reached the maximum possible decrease in the metric from the single transfer. Similarly, the percentage of equivalence changes like a step function.

Measuring attention inequality on Twitter

Having established how the metrics behave on synthetic data, we next evaluate how these metrics perform on real-world data from Twitter, focusing on distributions of different types of engagements. A priori, we expect different types of engagements to have meaningfully different distributions, as each engagement type requires a different level of effort by the user and is a different signal as to how the reader reacted to the Tweet. Therefore, comparisons of the metrics between these distributions should allow us to evaluate the stability and effect size criteria of the metrics as well as validate that they are indeed useful beyond a simple toy setting. Finally, we hope to use the metrics and comparisons to understand more carefully what drives attention inequality on Twitter.

Result 1: Inequality metrics meaningfully capture differences between engagement types

One way to measure the efficacy of distributional inequality metrics is to use them to quantify how skewed different types of engagements on Twitter are. In this section, we break down the distribution of engagements, both passive and active, finding that the engagements where readers share an author’s content to their own followers are the most skewed.

To analyze the types of engagement, we first collect a dataset of all users who authored Tweets in the month of August 2021 from any client, including Android, iOS, web, and third-party apps. For each of their Tweets in that time frame, we measure a number of different interactions, both passive and active. First, we count a passive interaction, also known as a “linger impression” (which we will simply refer to as an impression for short). An impression is logged when at least 50% of the Tweet is visible for at least 500 ms, indicating that the reader spent some amount of time viewing the Tweet. Next, we consider three types of active click-based engagements: profile clicks, likes, and Retweets. Profile clicks happen when a reader clicks on the author’s profile icon embedded as part of a Tweet (potentially indicating they wanted to learn more about the author). Likes are logged when a reader clicks the heart icon on a Tweet, while Retweets are logged when a reader clicks the Retweet icon and shares the tweet to their own followers. The third and final class of interactions is active content-based engagements. Replies happen when a reader clicks the reply icon and posts a Tweet in response to an author’s Tweet. Quote Tweets occur when a reader shares a Tweet with their own followers, by clicking the Retweet icon, but also adds their own content in response to the Tweet before sharing. These interactions span a range of efforts expended by the reader, from simply spending time on a Tweet to actively replying and sharing it. All interactions are logged by Twitter directly during a user’s session.

The final dataset aggregates, for each Tweet author, the number of interactions over all Tweets composed by that author in August 2021. The dataset includes authors who posted a tweet in that month but did not receive any interaction, as long as that author had at least one tweet selected for display on a timeline. For any particular interaction type, if an author did not receive any engagements of that type from readers in August, their count is zero in that distribution. We restricted our analysis to authors who have at least one follower. After aggregation, the dataset consisted of over 100,000 authors. (Note that the number of interactions is a raw count of engagements, not normalized to the author’s overall activity. We make this choice because an author’s overall activity is directly influenced by the number of impressions that they get. Since we are endeavoring to measure outcomes of the entire system of models, we want to be able to capture differences in activity as part of the metric. This is another reason that the normative assumption is not “no inequality,” as there is also inequality in activity over time. In addition, the income inequality metrics are less interpretable and generally not suited to distributions of rates as inputs [e.g., top 1% share of all impressions or dollars makes sense mathematically, but top 1% share of impressions per tweet or dollars per job less so]. The time frame we use to count the number of impressions is also August 2021. We compared our results to using a time frame for all impressions received until October 2021 [still using Tweets created in August], but found the differences to be negligible, as the average Tweet receives most of its impressions within a few days of creation.)

Figure 1 shows the Lorenz curves for different types of interactions. On the left, we see that it is difficult to distinguish the curves on a linear scale and that the area under the curves is quite small. As such, we show the curves on a logarithmic scale on the right, with a small linear region from 0 to 10−6. This view is interesting because we can clearly see the number of users at which the distribution transitions from zeros to non-zero counts. Unsurprisingly, this transition happens earliest for the impression interactions, as these are the lowest effort of interaction with a Tweet. It is also interesting to note that some of the curves do cross, making it difficult to evaluate the skew of the distributions visually.

Figure 4 shows the breakdown of the distributional inequality metrics by engagement type. For the Atkinson index, we chose , as we found this value to give good distinction between the engagement types while still being numerically stable. In each case, the interactions are sorted by their Gini index, to allow for comparison between metrics. To compute errors, we performed bootstrap resampling of the author population and recomputed the metric for each resample, but we found that these error bars were small enough not to be visible (except in the case of Figure 7B).

Figure 4.

Inequality of engagements: Families of metrics, computed for the distribution of different engagement types

(A) The Gini and Atkinson indices.

(B) The 80/20 share and percentile ratios. Note here that these are shown only for impressions, as for all other types of engagements the share of the bottom 20% of users is zero.

(C) The top 1% share and top 10% share for all engagement types.

(D) The percentage of equivalence and the bottom percentage of users with share equal to the top 10% of users. Note that here, the percentages are inverted (100 − metric value rather than the value itself) because these metrics are very close to 100% and are more easily visualized on a logarithmic scale when inverted.

Figure 7.

Breakdown by popularity: Breakdown of the ranking and miscellaneous out-of-network suggestion types by number of followers

(A) The average number of impressions increases similar to number of followers for both algorithms, with the overall number of in-network impressions being larger.

(B) For authors with lower numbers of followers, the distribution of impressions from out-of-network sources is significantly more skewed than for in-network sources. In the highest bin, the Gini indices between the two sources are close to each other, showing that the distributions of impressions are very similar for both suggestion types once an author has enough followers.

Our first observation is that the metrics all generally agree on the ordering of the distributions, with profile clicks being the least skewed distribution and quote Tweets being the most skewed. We also note that all of the distributions are quite imbalanced, with Gini index above 0.95 in all cases and top 1% share greater than 70%. Finally, we note that the 80/20 share and percentile ratios were calculable only for the impression distribution. As can be seen in the Lorenz curves of Figure 1, all other engagement types are still in the zero part of their distribution at the 20th percentile, making the ratio undefined.

In short, the metrics are able to distinguish between imbalances of different types of engagements. Specifically, we see differences in the value of each metric across different types of engagements, and the relative changes across distributions for the metrics are consistent with what we observed in synthetic data (i.e., the ratios and tail shares have larger differences between the distributions, while the entropy and equivalence metrics have smaller differences). In addition, we find that with very top heavy distributions, ratio metrics are unsuitable, as they would need to be adjusted per distribution to find the point where the quantity becomes non-zero in the population.

Result 2: Inequality metrics identify out-of-network suggestions as potential drivers of skew

It is clear from the previous section that engagements with content are quite skewed, with high-ranking authors receiving the bulk of interactions. Tweets can appear on a reader’s home timeline via a variety of sources. In this section, we propose using the metrics defined above to determine whether certain content suggestion types contribute more strongly to the overall skew of the distribution. This will allow us to determine what effect sizes they have when comparing different algorithm types, as well as giving us a concrete use case in which to evaluate their usability.

For this study, we focus on the impression distribution from the previous section. We break down the number of impressions by the source that recommended that Tweet to the reader, with the source logged by Twitter when a user’s timeline is generated during a session. In this dataset, we consider five different categories of suggestions. The first, “in-network” (IN) suggestions, consists of Tweets from authors followed by a reader. Next, we have some aggregated “out-of-network” (OON) suggestion types, or suggestions for Tweets that were created by a person not followed by the reader. One type, which we refer to as “OON, Likes,” consists of Tweets that appear on a reader’s timeline because they were liked by a person the reader follows, but the reader does not follow the author of the Tweet. Another, “OON, Graph,” includes Tweets that are considered interesting based on shared interests among the users, specifically computed using information from the social graph, and include recommendations coming from the SimCluster algorithm.39 The final category is an aggregation of miscellaneous other OON suggestions, including situations where an OON author was recently followed by in-network users, Tweets the reader may be interested in based on recent search queries, OON replies to in-network Tweets, and OON Tweets based on previous entities that the user engaged with. These are collectively referred to as “OON, Misc.” Finally, we consider a suggestion type that is a hybrid of in-network and OON. “Topics” suggestions come from topics that a reader has followed, including cases where the Tweet author themselves is not followed by the reader (although some Tweet authors in the Topic may be followed by the reader). As before, if an author did not receive any impressions via a particular suggestion type, their count is zero for that distribution.

Figure 5 shows the breakdown of metrics for impressions by suggestion type. Here, we report only the entropy and tail-share metrics, as the others are ill defined due to the presence of many zeros in the distributions. We find generally that suggestions for in-network Tweets have more equitable distributions of impressions than OON Tweets. This is likely due to the fact that the OON suggestion algorithms rely on the structure of the social graph. For example, in the case of “OON, Favorites.” the author must have a path to a reader B through follower A in order to appear on reader B’s feed. For in-network suggestion types, the number of impressions should grow roughly linearly with the number of followers, as these suggestions apply only to readers following the author. However, OON suggestion types are likely to have their impressions grow faster than linearly, as adding a single follower also adds paths to that follower’s followers.

Figure 5.

Inequality by suggestion type: Measured values of entropy-based and tail-share metrics by suggestion type for the distribution of impressions

We again choose for the Atkinson index, as in Figure 4. The distribution of impressions from the in-network ranking algorithm is the least skewed, while miscellaneous out-of-network suggestions are the most skewed.

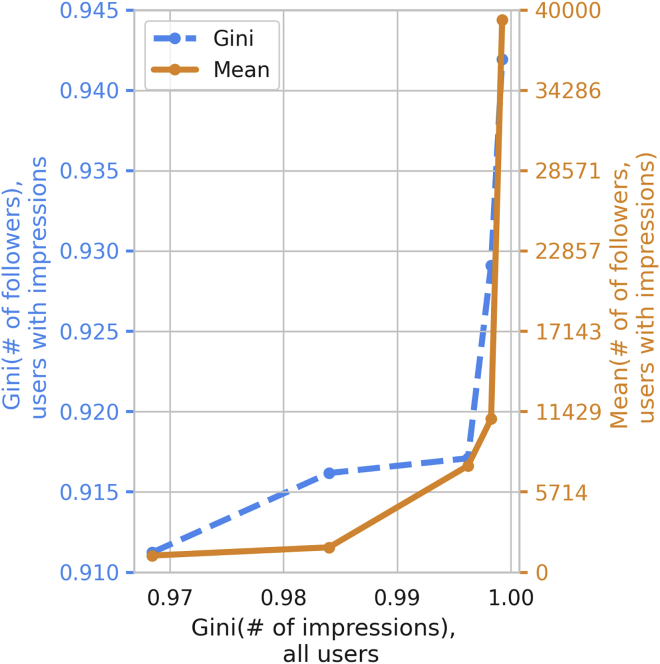

To further analyze these results, we consider the relationship between impression skew and number of followers, focusing on the Gini index (Gini, Atkinson, and top 1% share were all found to be highly correlated in these data, so we chose the Gini index for simplicity). Figure 6 shows the Gini index and average of the number of followers distribution for authors who received impressions from a particular suggestion type as a function of the Gini index for that suggestion type from all users (the quantity shown in Figure 5, left). We see that suggestion types that have larger Gini indices for impressions also have larger means and Gini indices for number of followers, indicating that authors who benefit from the more skewed interaction types have more followers.

Figure 6.

Gini of impressions and followers: A comparison of the Gini coefficient of number of impressions and the statistics of number of followers

Each point is one suggestion type, and the y axis shows the Gini index and average of number of followers for users who received impressions from that suggestion type.

Another way to see this effect is shown in Figure 7. Here, we bin authors by number of followers, allowing us to compute the within-bin Gini indices and average number of impressions by bin. Figure 7A shows how the average number of impressions grows with average number of followers in the bin. The number of impressions grows at a similar rate for both the ranking and the OON suggestions, with authors in general getting more impressions via the in-network ranking suggestions. However, when we look at the within-bin Gini index versus the average number of followers, we see that the distribution of impressions that come from OON suggestions is much more skewed for authors with a low number of followers. The within-bin Gini indices for authors with a very high number of followers are almost identical between the ranking and the OON suggestions, while for lower numbers of followers the OON distribution is significantly more skewed. This gives some support to the hypothesis that the larger disparities seen in OON suggestion types are driven by the number of followers an author has, with a smaller fraction of low-follower authors getting an opportunity to have their content exposed via OON suggestions. We note also that some of these disparities may be coming from biases in upstream algorithm behavior as well, and an interesting direction for future work would be to attempt to decompose the influence of the algorithm itself from the structure of the network.

Overall, these results demonstrate the richness of potential insights that can be derived from the use of these metrics in operational settings. In addition, they have given us a better understanding of how they satisfy the empirical properties we set forth, as we discuss in more detail in the next section.

Discussion

How do the proposed metrics measure up?

In the empirical use cases above, we have seen that distributional inequality metrics can help us glean detailed information about both the state and the origins of skews in algorithm-driven outcomes on a platform like Twitter. In this section, we will revisit the proposed criteria we set forth early on in light of those analyses.

Evaluation with respect to desirable criteria

Table 2 shows our evaluation of the criteria based on the analyses of impression distributions we conducted on both synthetic and real data.

Table 2.

Metric criteria overview: Summary of metrics and desirable criteria

| Theoretical |

Qualitative |

Empirical |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population? | Adjustable? | Scale? | Subgroups? | User? | Stable? | Effect? | |

| Gini | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | high | low |

| Atkinson | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | high | low |

| Top X% share∗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | high | high |

| Percentile ratio | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | low | medium |

| Share ratio | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | low | high |

| Equiv to top X% | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | high | low |

| % of equal share | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | high | low |

∗ indicates the best performing metric according to the criteria

With respect to the theoretical criteria, the performance of the metrics varies. The entropy, tail-share, and ratio metrics are all population invariant, meaning that they have the same meaning regardless of population size. The equivalence metrics do not satisfy this criterion, as the percentage they output has a different meaning in terms of number of users as the population changes. For adjustability, most metrics had an adjustable parameter, with the exception of the Gini index and percentage of equal share. All of the metrics were multiplicative scale invariant, keeping the same output if all values in the distribution are multiplied by a constant. Finally, only the entropy metrics were subgroup decomposable, with all the other metrics lacking this property because the percentages calculated on subgroups are not easily mapped to the full population due to overlaps in ranks between the groups (e.g., a person in the top 1% of a subgroup could be in the bottom 1% of the full population). (We note that Atkinson specifically is “additively decomposable,” meaning that the total Atkinson index is a sum of the Atkinson index on subgroups. Gini is still decomposable, but the total Gini is a weighted average of subgroup Gini indices, with the weights being the population fraction of the subgroup.)

For the qualitative criteria, we found a similar mix of results. In user focus, all percentage-based metrics passed the criteria, as either their parameters or their outputs could be directly translated to a number of users. The entropy metrics did not meet this criterion. We decided not to include interpretability in the summary table because there is no rigorous way to evaluate it with this work. Subjectively, we feel that the top X% share metrics are highly interpretable, as they use phrasing that is common in everyday discussion (e.g., “the top 1% of authors get 80% of all impressions”). However, a user study would be required to fully evaluate the interpretability of the metrics, and that is out of the scope of this work.

Finally, we evaluate the empirical criteria based on the synthetic and real examples examined earlier in the paper. For this discussion, we focus on the high inequality regime. All metrics except the ratio metrics are quite stable, with negligible error bars seen from bootstrap resampling on real data and resampling from the same underlying distribution in synthetic data. We rate the ratio metrics as having low stability because their values can become quite large if the low end of the population does not have a large share of wealth, and in many cases they can even be undefined. In addition, in the synthetic setting, their relative error at high inequality was orders of magnitude higher than the other metrics, reaching almost 1 part in 10. For effect size, the top X% share and share ratios had the highest rating, with a large dynamic range when comparing different engagement types or algorithms (see Figures 4C and 5, right) and the most responsivity to transfers in the synthetic dataset. The entropy and equivalence metrics showed relatively low differences in both datasets. Even in the real Twitter data, the percentage of equivalence had to be visualized as its inverse, since the differences between distributions were so small.

When considering all the criteria together, we find that the top X% share received the highest ratings for this dataset, failing only the subgroup decomposability criterion. The entropy-based metrics had no user focus, but did well in other criteria. Ratio and equivalence metrics had low stability and effect size, respectively, and failed some of the theoretical criteria. Overall, we hope that these evaluations will be useful for practitioners in deciding which metric may be best suited to their use case.

Limitations of proposed metrics

While we found that distributional inequality metrics were useful for capturing discrepancies in exposure for authors on Twitter, these metrics (like any metric) do have inherent limitations. First, these metrics are most useful for distributions where “improvement” can be defined as a reduction in the skew. If, for example, these metrics were applied to a quantity where benefit versus harm is more ambiguous, they might be less useful in evaluating disparities. Second, while their lack of reliance on demographic information is useful in an operational context, they cannot ever fully replace measurements of disparate treatment or outcomes between groups. They are meant as a supplement to illustrate trade-offs rather than a replacement, as it will always be crucial to understand how algorithms are affecting underrepresented groups specifically. Finally, our evaluation of the criteria is limited to the characteristics of the datasets we evaluated. However, we feel that these highly concentrated impressions distributions are indicative of many distributions on internet datasets, and therefore these metrics should be useful for any distributions that exhibit similar properties.

Future directions

Based on what we learned from the evaluation of these metrics, we have found a few key paths for future work that we intend to pursue. First, we are developing tools to leverage inequality metrics during product development, so that those building machine learning models can use them to understand disparate impacts. Second, we aim specifically to understand how to integrate these metrics into A/B testing frameworks, particularly focusing on how the choice of randomization unit affects the choice of metric. Third, we believe more work is needed to understand the changes in inequality as a function of number of followers for in-network versus out-of-network suggestions. To this end, future work could focus on measures of inequality that explicitly incorporate information about graph structure. Finally, we hope to conduct user studies in the future to better understand how practitioners interact with these metrics and to assess their interpretability.

Conclusion

In this paper, we evaluated a number of metrics in the context of outcomes of Twitter’s recommendation system. We found that certain metrics are useful in different contexts, with the top X% share performing the best according to our evaluation criteria. We used these metrics to identify sources of skew in engagements with content on Twitter, particularly noting that certain OON suggestions lead to more skewed outcomes. In addition, we showed that having a lower number of followers disproportionately skews outcomes for OON suggestions compared with in-network suggestions. Overall, we found that these metrics are useful tools for identifying algorithmic sources of disparate outcomes.

Experimental procedures

The data used for this analysis were collected internally by Twitter directly from interactions of users with Twitter’s platform client applications. Details of the specific datasets used can be found in the results.

Resource availability

Lead contact

The lead contact for this work is Tomo Lazovich, whose email is tlazovich@twitter.com.

Materials availability

No physical materials were used for this paper.

Visual representation of inequality metrics

Figure 8 shows an annotated Lorenz curve of synthetic data (generated from a sum of Poisson distributions) that we can use to define other quantities of interest. The follow metrics can be defined in terms of quantities labeled on the curve:

-

•

Gini index: A is the area between the curve and the line of equality, and B is the area below the Lorenz curve. The Gini index can be defined as . Equivalently, because , it is equal to or .

-

•

Top X% share: d is 1 minus the value of the curve at a fraction of 0.8. This corresponds to the share of the top 20% of individuals in the population.

-

•

Share ratio: c is the value of the Lorenz curve at a cumulative population fraction of 0.2. The quantity is the 80/20 share ratio, or the share held by the top 20% divided by the share held by the bottom 20%.

-

•

Equivalent to top X%: the cumulative population fraction e is the bottom percentage of users equivalent to the top 20%, as it is the fraction at which the point on the Lorenz curve equals d.

-

•

Percentage of equivalence: the fraction f is the point at which the Lorenz curve’s value is 50%, meaning that the top % of individuals has the same share as the bottom %.

Figure 8.

Example Lorenz curve: An example Lorenz curve with annotations that can be used to derive several related metrics

Capital letters (A and B) are areas, while the rest are lengths.

Distribution of followers

In the second case study, we explored the impressions distributions and metrics as a function of number of followers. Figure 9 shows the distribution of number of followers, as was used for binning in that section.

Figure 9.

Follower multiplicity distribution: Distribution of number of followers for users in the dataset described in the results

The bins here correspond to the bins used to define each point in Figure 7.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Neal Cohen, Claire Woodcock, Wenzhe Shi, the members of the Twitter META team, and the reviewers for their insightful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. The work by F.H. on this article was completed while the author was a consultant for Twitter. All authors were compensated by Twitter for this work, either as employees or as a paid consultant. Funding for the project was provided by Twitter.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the formulation of the project and contributed insights throughout the process. T.L. conducted the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. L.B., K.L., F.H., and R.C. advised the project and provided guidance. A.G. helped provide the dataset used in the analysis. A.B. and U.T. gave ideas and advice during the project and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

Dr. Rumman Chowdhury is a member of the Patterns advisory board, and all authors are affiliated with Twitter.

Published: August 12, 2022

Data and code availability

Because these distributions are computed on individual user data, it is not possible to make the full dataset publicly available due to privacy constraints. However, the authors do note that parts of the paper, in particular the comparison of non-impression engagement distributions, are reproducible through Twitter’s public API. Any researchers who wish to reproduce these results would need to agree to the appropriate terms and apply through Twitter’s developer portal for access to the data. Given that the code for this paper was geared toward internal data rather than the public API, we cannot release it directly. However, there are many publicly available examples on how to access these data through the Twitter API. In addition, Twitter is exploring methods to release additional data to experimenters in a privacy-preserving way.40

References

- 1.McCurley K.S. 2008. Income Inequality in the Attention Economy.https://storage.googleapis.com/pub-tools-public-publication-data/pdf/33367.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu L., Lerman K. Attention inequality in social media. arXiv. 2016 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1601.07200. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClain C., Widjaya R., Rivero G., Smith A. The behaviors and attitudes of U.S. adults on Twitter. 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/11/15/the-behaviors-and-attitudes-of-u-s-adults-on-twitter/

- 4.Benjamin R. John Wiley and Sons; 2019. Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buolamwini J., Gebru T. Conference on fairness, accountability and transparency. PMLR; 2018. Gender shades: intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification; pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noble S.U. New York University Press; 2018. Algorithms of Oppression. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barocas S., Hardt M., Narayanan A. 2019. Fairness and Machine Learning.http://www.fairmlbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehrabi N., Morstatter F., Saxena N., Lerman K., Galstyan A. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021;54:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell S., Potash E., Barocas S., D’Amour A., Lum K. Algorithmic fairness: choices, assumptions, and definitions. Annu. Rev. Stat. Appl. 2021;8:141–163. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geyik S.C., Ambler S., Kenthapadi K. Proceedings of the 25th acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining. 2019. Fairness-aware ranking in search & recommendation systems with application to linkedin talent search; pp. 2221–2231. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sapiezynski P., Zeng W., E Robertson R., Mislove A., Wilson C. Companion Proceedings of The 2019 World Wide Web Conference. 2019. Quantifying the impact of user attention on fair group representation in ranked lists; pp. 553–562. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang K., Stoyanovich J. Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Scientific and Statistical Database Management, SSDBM ’17. New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery; 2017. Measuring fairness in ranked outputs. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trapeznikova I. IZA World of Labor; 2019. Measuring Income Inequality. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Speicher T., Heidari H., Grgic-Hlaca N., Gummadi K.P., Singla A., Weller A., Zafar M.B. Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge. Discovery & Data Mining; 2018. A unified approach to quantifying algorithmic unfairness: measuring individual &group unfairness via inequality indices; pp. 2239–2248. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandy J., Diakopoulos N. More accounts, fewer Links: how algorithmic curation impacts media exposure in twitter timelines. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021;5:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saint-Jacques G., Sepehri A., Li N., Perisic I. Fairness through Experimentation: inequality in A/B testing as an approach to responsible design. arXiv. 2020 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2002.05819. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cowgill B., Tucker C.E. Columbia Business School Research Paper; 2020. Algorithmic Fairness and Economics. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rambachan A., Kleinberg J., Ludwig J., Mullainathan S. An economic perspective on algorithmic fairness. AEA Papers and Proceedings. 2020;110:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasy M., Abebe R. Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. 2021. Fairness, equality, and power in algorithmic decision-making; pp. 576–586. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biega A.J., Gummadi K.P., Weikum G. The 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval. 2018. Equity of attention. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh A., Joachims T. Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. 2018. Fairness of exposure in rankings; pp. 2219–2228. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zehlike M., Bonchi F., Castillo C., Hajian S., Megahed M., Baeza-Yates R. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management. 2017. FA∗IR: A Fair Top-k Ranking Algorithm. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dwork C., Hardt M., Pitassi T., Reingold O., Zemel R. Proceedings of the 3rd innovations in theoretical computer science conference. 2012. Fairness through awareness; pp. 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bower A., Eftekhari H., Yurochkin M., Sun Y. Individually fair rankings international conference on learning representations. 2021. https://iclr.cc/virtual/2021/poster/2627

- 25.Raj A., Ekstrand M.D. Comparing fair ranking metrics. axRiv. 2020 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2009.01311. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulshrestha J., Eslami M., Messias J., Zafar M.B., Ghosh S., Gummadi K.P., Karahalios K. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, CSCW ’17, 417–432. New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery; 2017. Quantifying search bias: investigating sources of bias for political searches in social media. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L., Ma R., Hannák A., Wilson C. Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’18, 1–14. New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery; 2018. Investigating the impact of gender on rank in resume search engines. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green B. SSRN; 2022. Escaping the Impossibility of Fairness: From Formal to Substantive Algorithmic Fairness. Published online April 25, 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milli S., Belli L., Hardt M. Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. 2021. From optimizing engagement to measuring value; pp. 714–722. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allison P.D. Measures of inequality. Am. Socio. Rev. 1978;43:865–880. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farris F.A. The Gini index and measures of inequality. Am. Math. Mon. 2010;117:851–864. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gini C. In: Reprinted in Memorie di metodologica statistica. Pizetti E., editor. 1912. Variabilità e mutabilità. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atkinson A.B. On the measurement of inequality. J. Econ. Theor. 1970;2:244–263. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sitthiyot T., Holasut K. A simple method for measuring inequality. Palgrave Commun. 2020;6:112–119. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorenz M.O. Methods of measuring the concentration of wealth. Publ. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1905;9:209–219. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shorrocks A.F. The class of additively decomposable inequality measures. Econometrica. 1980;48:613–625. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biró T.S., Néda Z. Gintropy: Gini index based Generalization of entropy. Entropy. 2020;22:E879–E4300. doi: 10.3390/e22080879. https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/22/8/879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Virtanen P., Gommers R., Oliphant T.E., Haberland M., Reddy T., Cournapeau D., Burovski E., Peterson P., Weckesser W., Bright J., et al. SciPy 10 Contributors SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods. 2020;17:261–272. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Satuluri V., Wu Y., Zheng X., Qian Y., Wichers B., Dai Q., Tang G.M., Jiang J., Lin J. Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. 2020. Simclusters: community-based representations for heterogeneous recommendations at twitter; pp. 3183–3193. [Google Scholar]

- 40.OpenMined . 2022. Announcing Our Partnership with Twitter to Advance Algorithmic Transparency.https://blog.openmined.org/announcing-our-partnership-with-twitter-to-advance-algorithmic-transparency/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Because these distributions are computed on individual user data, it is not possible to make the full dataset publicly available due to privacy constraints. However, the authors do note that parts of the paper, in particular the comparison of non-impression engagement distributions, are reproducible through Twitter’s public API. Any researchers who wish to reproduce these results would need to agree to the appropriate terms and apply through Twitter’s developer portal for access to the data. Given that the code for this paper was geared toward internal data rather than the public API, we cannot release it directly. However, there are many publicly available examples on how to access these data through the Twitter API. In addition, Twitter is exploring methods to release additional data to experimenters in a privacy-preserving way.40