Abstract

Introduction

Remote patient monitoring (RPM) is a telehealth activity to collect and analyze patient health or medical data. Its use has expanded in the past decade and has improved medical outcomes and care management of non-communicable chronic diseases. However, implementation of RPM into routine clinical activities has been limited. The objective of this study was to describe the French funding program for RPM (known as ETAPES) and one of the RPM solution providers (Satelia®) dedicated to chronic heart failure (CHF).

Methods

A descriptive assessment of both the ETAPES funding program and Satelia® RPM solution was conducted. Data were collected from official legal documents and information that was publicly available online from the French Ministry of Health.

Results and Discussion

ETAPES was formally created in 2016 based on previous legislation pertaining to the national health insurance funding strategy. However, it only started to operate in 2018. Patients with CHF were only eligible if they were at medium or high risk of re-hospitalization with a New York Heart Association (NYHA) score superior or equal to two and a BNP>100 pg/ml or NT pro BNP>1000 pg/ml. Medical monitoring was supported through the therapeutic education of a patient on the RPM model of care with a minimum of three training sessions during the first six months. The use of Satelia® Cardio is noteworthy since it relies only on symptomatic monitoring through which the patient manually reports their information by answering a simple questionnaire on a regular basis and does not rely on any connected devices.

Conclusion

Innovative funding programs and solutions for RPM need real-world evaluation in the future.

Keywords: Chronic heart failure, telemedicine, telehealth, remote patient monitoring, health funding

Introduction

Remote patient monitoring (RPM) is a telehealth activity employed to collect and analyze patient health or medical data and is primarily involved in medical follow-ups.1,2 Data from RPM is either collected directly by a patient and/or caregiver and may involve connected medical devices. The activity has shown the most growth in Europe and in North America over the past decade and has noticeably improved medical outcomes and care management of non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs). However, implementing RPM into routine clinical activities has been limited due to the lack of dedicated funding models, good practice guidelines, and high-quality scientific evidence.

To date, cardiovascular diseases have been a central topic of research and evaluation for the use of RPM in medicine. Within these NCDs, chronic heart failure (CHF), implantable cardiac devices (ICD), and atrial fibrillation were those given the most attention and yielding the most results.3–10 The purpose of using RPM for CHF is to more rapidly detect clinical situations that risk complications to prevent episodes of acute heart failure, which may cause a visit to the emergency department, re-hospitalization, or even death if left untreated. Several studies from various countries have suggested a positive impact of RPM for CHF on some or all risks involved.11–13

In France, RPM for CHF is not yet publicly funded by the national health insurance system in routine medical practice; however, it has been involved in several experimental initiatives. Various clinical studies have been conducted with mixed results to date. 14 Most importantly, the Ministry of Health (MOH) started a temporary national funding program for NCDs (including CHF) known as ETAPES through which healthcare providers and RPM solution providers are temporarily being funded. Moreover, this program is a prefiguration for integrating the RPM funding model for routine clinical activities into a model that has not yet been defined. 15 The objective of this study was to describe the French funding program for RPM (ETAPES) and an RPM solution provider (Satelia®) for CHF.

Methods

A descriptive study of both the ETAPES funding program and the Satelia® solution on RPM for CHF was conducted. Satelia® solution was described to provide an example of solution accepted in the ETAPES program.

Data concerning the ETAPES program were collected from official legal documents and public information that was available online from the MOH. 16 Legal documents were identified through a search of the Legifrance online database using keywords related to the ETAPES program. The key words in French language use for the legal database search were “Télémédecine,” “Télésurveillance,” “ETAPES,”

Data concerning the Satelia® solution were collected directly from internal company documentation. Description of the ETAPES program included the regulatory basis for the program, the medical model of RPM for CHF included in the program, its associated funding model, and the processes required to be registered as an experimentation site as well as a solution provider.

RPM solution providers listed by the French MOH were identified and each solution was described according to its name, company name, date of listing by the MOH, and whether they were listed for other diseases within the ETAPES program. Satelia® was specifically detailed according to the model of care including the questionnaire content, frequency of questionnaires, alerts, and educational content. An ethical agreement was not required to conduct this study in accordance with French regulations on medical research.

This study did not include any quantitative or qualitative evaluation of the ETAPES program or the Satelia® Cardio solution.

Results

The ETAPES program was formally created in 2016 and was based on 2014 legislation for the national health insurance funding strategy for three chronic diseases (CHF, chronic respiratory failure, and chronic kidney failure). In 2017, the medical scope of the program was further extended to include diabetes and ICD as well. Furthermore, the program has been extended for four additional years that will end on 31 December 2021 and had an update to the medical and funding model in October 2018 which was also again revised in December 2020 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Timeline and legal foundation of the ETAPES funding program for remote patient monitoring in France.

| Year | Legal basis | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | LOI n° 2013-1203 du 23 décembre 2013 de financement de la sécurité sociale pour 2014 | Creation of a national program for experimenting new telehealth funding models. |

| 2016 | Arrêté du 6 décembre 2016 portant cahiers des charges des expérimentations relatives à la prise en charge par télésurveillance mises en œuvre sur le fondement de l’article 36 de la loi n° 2013-1203 de financement de la sécurité sociale pour 2014 | Creation of the ETAPES program for funding remote patient monitoring for chronic diseases applied to nine administrative regions. Chronic diseases covered in this program include chronic heart failure, chronic respiratory failure, and chronic kidney failure. |

| 2017 | LOI n° 2016-1827 du 23 décembre 2016 de financement de la sécurité sociale pour 2017 | Extension of the ETAPES program to a nationwide scale to all regions in France. |

| Arrêté du 25 avril 2017 portant cahier des charges des expérimentations relatives à la prise en charge par télésurveillance du diabète mises en œuvre sur le fondement de l’article 36 de la loi n° 2013-1203 de financement de la sécurité sociale pour 2014 | Integration of remote patient monitoring for diabetes into the ETAPES program. | |

| Arrêté du 14 novembre 2017 portant cahier des charges des expérimentations relatives à la prise en charge par télésurveillance des patients porteurs de prothèses cardiaques implantables à visée thérapeutique mises en œuvre sur le fondement de l’article 36 de la loi n° 2013-1203 de financement de la sécurité sociale pour 2014 | Integration of remote patient monitoring of implantable cardiac devices into the scope of the ETAPES program. | |

| 2018 | LOI n° 2017-1836 du 30 décembre 2017 de financement de la sécurité sociale pour 2018 | Extension of the ETAPES program to four years, from 2018 until 31 December 2021. |

| Arrêté du 11 octobre 2018 portant cahiers des charges des expérimentations relatives à la prise en charge par télésurveillance mises en œuvre sur le fondement de l’article 54 de la loi n° 2017-1836 de financement de la sécurité sociale pour 2018 | Revision of the ETAPES program based on newly enacted legislation. | |

| 2020 | Arrêté du 23 décembre 2020 portant cahiers des charges des expérimentations relatives à la prise en charge par télésurveillance mis en œuvre sur le fondement de l’article 54 de la loi n° 2017-1836 de financement de la sécurité sociale pour 2018 | Update of the ETAPES program following the Covid-19 pandemic. |

Patients with CHF were only eligible for the program if they were at medium or high risk of re-hospitalization with a New York Heart Association (NYHA) score≥2 and a Brain Natriuretic Peptid (BNP)>100 pg/ml or NT pro BNP>1000 pg/ml. Patients were required to have a long-term disease (“Affection Long Durée”) registered with national health insurance system and be present in a nursing home, hospital, or have a permanent residence. 7

Patients were not eligible if a physician's assessment deemed them to not be physically or mentally able to be remotely monitored. This was also the case for those who had chronic dialysis, severe liver failure, the presence of any other medical condition resulting in a less than one-year life expectancy, an estimated low adherence to treatment, and/or the lack of a stable place of residence. Patients refusing to participate in the program were also ineligible.

Inclusion of patients was possible only by referral from cardiologists, general practitioners with a post-graduate diploma in heart failure, treating physicians, or geriatricians. Only the first two were allowed to perform the RPM. A medical prescription was mandatory if the referring physician was not also acting as the monitoring physician. Every six months, a physician assessed whether a patient was still eligible and showed no subsequent exclusion criteria. Monitoring occurred at intervals of between one to five times per week depending on the risk score and the patient's wishes and could include clinical alerts to be managed.

Medical monitoring was supported through the therapeutic education of a patient on the RPM model of care with a minimum of three sessions during the first six months. The session could be conducted physically, by phone, or online through video calls or via an e-learning content platform. The sessions were conducted by physicians trained in therapeutic education having completed a Continuous Medical Education (CME) program or possessing a post-graduate diploma, or by other Healthcare Professionals (HCPs) with the same requirements who had received training on heart failure through a CME program. The sessions included an educational diagnosis, patient training based on guidelines from the French Society of Cardiology, and the definition of relevant clinical targets. Each session was recorded in the patient's medical records.

Medical monitoring included data collection of the patient's weight. A medical algorithm generating clinical alerts in case of early decompensation and the potential need to have a treatment updated was also included. The alert was sent directly to the physician in charge of the monitoring or triaged by a nurse who was responsible for contacting the patient first to check the relevance of the alert. All data was recorded in the medical record and could be shared with a patient and/or the treating physicians if patient's prior informed consent was given.

Physicians and healthcare facilities wanting to participate in the program were required to send a written declaration based on a national template provided by the MOH to their respective Regional Health Agency and Departmental Medical Board. Solution providers of RPM tools sent a declaration to the same entities as well as to the MOH. The funding model combined both capital-based funding and pay-for-performance models. The monitoring physician, the HCP performing the therapeutic education, and the solution provider were all included in the funding model and paid directly by the public health insurance system.

The capital-based model was biannual and was paid based on stakeholder declarations submitted to the insurance system through a dedicated funding code created for the ETAPES program (Code TSF for the solution provider, Code TSM for the physician, and Code TSA for the therapeutic education professional). For each six-month period and for each patient, the fees were 110€ for the physician, 60€ for the professional in charge of the therapeutic education, and 300€ for the RPM solution provider (Table 2).

Table 2.

Funding model of ETAPES program for the remote patient monitoring of chronic heart failure patients in France.

| Role | Capital-based funding | Pay-for-performance funding |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring physician | 110€ per semester per patient | [0.15*(year-to-year cost difference) /amount of physicians]/number of patients |

| Therapeutic education professional | 60€ per semester per patient | [0.05*(year-to-year cost difference)/amount of physicians]/number of patients |

| Solution provider | 300€ per semester per patient | [0.30*(year-to-year cost difference)]/ number of patients |

The pay-for-performance model was triggered if there was a relative decrease of 20% of total hospitalizations for CHF patients included in the ETAPES program per healthcare provider or healthcare facility compared to the previous year's data. The cost difference between the two years was multiplied by 0.15, 0.05, or 0.30 for the physician, education professional, and the solution provider, respectively, and then divided by the number of patients monitored.

As of 31 July 2021, there were 26 providers listed by the MOH that supplied RPM for the ETAPES program. One solution provider was listed three times with the same name but under three different legal entities. Another company was listed as having two different solutions for the same purpose. Half the providers were listed in 2018, which was the year that the program was renewed, whereas only one solution was added in 2019, and another one in 2020. Most of the solutions (n = 14) were also listed in the ETAPES program for another disease (Table 3).

Table 3.

Telehealth solutions listed in the ETAPES program for remote patient monitoring for chronic heart failure patients in France.

| Name | Company | Listed | CHF only |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covotem | GCS Normand’e-Santé | 31/10/17 | Yes |

| 1 minute pour mon coeur | Newcard | 27/11/17 | No |

| NOMHADChronic | CDM e-health | 05/12/17 | No |

| Latitude NXT | Boston Scientific | 12/12/17 | No |

| Implicity insuffisance cardiaque | Implicity | 05/01/18 | No |

| ApTelecare | TMM Software | 18/01/18 | No |

| Cardio + | BePatient | 07/02/18 | Yes |

| Optified Self | Almerys | 27/03/18 | Yes |

| C-WE | Serviligne Développement | 03/04/18 | No |

| Colnec | Colnec Health | 07/05/18 | No |

| Satelia | NP Medical | 11/05/18 | No |

| Coramis | Ysiis | 02/07/18 | No |

| MH Link | MHCOMM | 05/07/18 | No |

| Vivii | 3C Health | 09/07/18 | No |

| Careline | Careline Solutions | 13/08/18 | Yes |

| My Predi | Predimed technology | 14/08/18 | No |

| Optified Self | GCS Cardiauvergne | 19/10/18 | Yes |

| Telaais | Telaais | 28/03/19 | No |

| Theraflow IC | Betterise Technologies | 11/05/20 | Yes |

| Optified Self | Be Ys Health solutions France | 19/01/21 | Yes |

| Cardiolaxy | Betterise Technologies | 04/03/21 | Yes |

| TwoCan Pulse | E Device SA | 24/03/21 | Yes |

| DIETIS Telesurveillan ce | Alantaya | 30/06/21 | No |

| EIIS | Epoca Uxi | 01/07/21 | No |

| Bioserenity Platform | Bioserenity | 05/07/21 | Yes |

| Educat | SAS Educat | 15/07/21 | Yes |

Satelia® Cardio is a CHF patient management solution with a remote monitoring system and therapeutic guidance. It is a software-as-a-medical device system with a CE marking label. The system is accessible from any device and does not require any software installation, application, or external sensors. Its use caters to all non-connected patients and does not induce digital inequity like other innovative remote patient management systems. This ensures that the platform is more than a standard telehealth platform by still including the means and processes to follow-up on patients who would usually not be able to perform the periodic online questionnaires alone.

At the time of this study, non-connected patients on the Satelia® Cardio platform were managed through a dedicated phone platform where nurses could deliver coaching sessions to patients in need (in addition to the help provided answering the questionnaires). The platform also included a series of 12 short educational movies on CHF in lay language to improve their understanding and awareness of the disease and its care management. The videos were available through the patient portal.

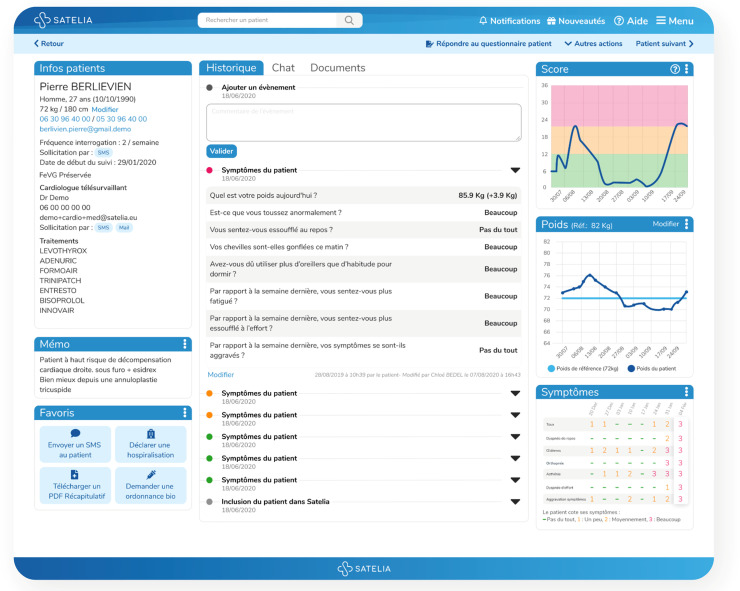

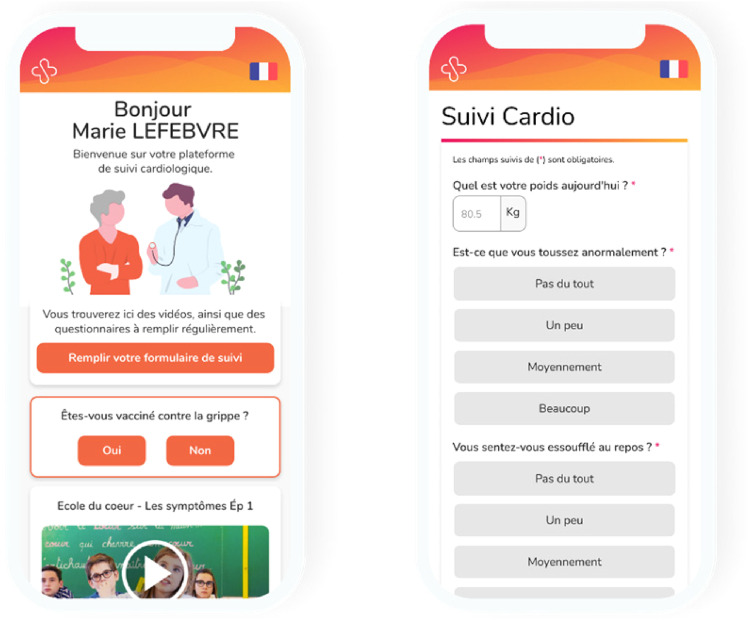

The workflow of the RPM solution included the following steps: (i) patient inclusion by a cardiologist, (ii) phone call by a nurse within 48 h after inclusion to explain the process, (iii) reception of SMS by a patient, with a hyperlink inviting them to answer a symptomatic questionnaire (eight questions) (Table 4), (iv) the same SMS received one or more times per week during the monitoring period, (v) notification to the nurse and/or physicians in case of clinical alerts of worsening symptoms, and (vi) reminders if the alert was not addressed. Alerts were triggered by a clinical algorithm based on the answers from the questionnaire. Furthermore, the nurse was able to call patients directly to conduct the questionnaire by phone (Figures 1 and 2).

Table 4.

Questionnaire from the Satelia® Cardio remote patient monitoring solution.

| Question | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | What is your body weight today? |

| 2 | Are you coughing abnormally? |

| 3 | Do you feel out of breath at rest? |

| 4 | Are your ankles swollen this morning? |

| 5 | Did you have to use more pillows than usual to sleep? |

| 6 | Compared to last week, do you feel more tired? |

| 7 | Compared to last week, do you feel more out of breath when making an effort? |

| 8 | Compared to last week, did your symptoms worsen? |

Figure 1.

Satelia® doctor interface for the remote patient monitoring of chronic heart failure in France.

Figure 2.

Satelia® patient interface for the remote patient monitoring of chronic heart failure in France.

Discussion

The ETAPES program has been an innovative national funding program of RPM focusing on chronic diseases including CHF. It was developed through comprehensive legislative efforts from 2014 and listed telehealth solutions such as Satelia® Cardio, a web application dedicated to CHF digital management.

ETAPES has also been a unique model in the world since it continues to provide temporary national public funding to healthcare providers and telehealth solution providers in RPM of CHF based on specific medical criteria. To date, no other countries have initiated such a program. In Germany, the DiGa initiative stemming from the 2019 Digital Healthcare Act aims to allow health insurance systems to fund digital health apps prescribed by physicians.17,18 The program which came into effect in April 2020 has, however, been more of a fast-track market access method rather than a medical program with predefined criteria. Additionally, it does not focus solely on RPM. Similar processes have nonetheless been observed with a prerequisite assessment from the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, BfArM) to be listed in a directory of reimbursable digital health applications.

The ETAPES program differs from the US approach of routine RPM reimbursement from the Center for Medicare and Medicare Services (CMS) updated in 2021.19,20 In this public program, RPM data must be automatically collected from connected devices and cannot be collected manually by the patient, such as with patient-reported outcomes or symptomatic monitoring. Therefore, the medical scope of the American program is limited to and only based on connected devices. Another difference is the absence of a restricted funding scope which allowed physicians, on the other hand, to decide for themselves when they think RPM may be relevant for their patient. There are, however, some similarities such as the existence of the CPT code 99453 which compensates providers for patient onboarding and education.

The use of Satelia® Cardio may be prominent since it relies only on symptomatic monitoring where the patient manually reports information by consistently answering a questionnaire on a regular basis and does not rely on any connected devices. 21 Moreover, the questionnaire is linked to a clinical algorithm within a solution recognized as a medical device therefore allowing for reimbursement as routine care by the national health insurance system following proof of effectiveness.

The weight was reported by the patient and did not rely on any connected weight measurement device integrated into the web application. Self-questionnaires may be easier to implement and expand by avoiding any logistic or connectivity issues from the connected devices but implies trusting the patient regarding their reported weight and symptoms. This method may also promote a better sense of empowerment from the patient since data collection and reporting on the system or through the nurse implies an active involvement and awareness of the data in contrast to automatically shared data where the patient may not be aware of what is transpiring. The combination of nurse management within the overall disease management strategy corresponded with a recent network meta-analysis showing the impact of home visits by a nurse on reducing all-cause mortality compared to usual care. 22 Regarding educational content, it is included in the application and therefore accessible by users at any time allowing for a large-scale deployment. The educational sessions organized by nurses would however require additional resources for further implementation. This additional resource may be useful as well to monitor and promote sustained patient empowerment over longer period of time.

While defining strict inclusion and exclusion criteria for patient participation, the ETAPES program for CHF does not define a strict model of care for the monitoring itself. The only obligations are to include daily weight monitoring and the use of an algorithm to trigger alerts. The detailed monitoring parameters (monitoring frequency, questionnaires content, alerts generation algorithm, alert management algorithm, data collection method) were however not defined. Therefore, each telehealth solution provider may define and evaluate their own specific model. This approach aligned with the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for heart failure stating that “the optimal method of monitoring will depend on local organizations and resources and will vary among patients” and that “each approach needs to be assessed on its individual merit.” 23 The guidelines were updated in 2019 to promote the use of home telemonitoring of CHF in a similar model to that of the TIM-HF2 study,24,25 and recently in 2021 as well. 26

In conclusion, regarding the ETAPES program, it is clearly necessary that each type of model of care and solution provider be assessed based on published scientific results to identify the most suitable models or frameworks to support routine funding of RPM from 2022 onwards. 27 Moreover, there have not currently been any scientific publications released on RPM of CHF within the ETAPES program in France. Real-world studies therefore need to be strongly promoted within this program to provide relevant data for policymakers in the future. Such studies are ongoing for Satelia® Cardio to assess the impact on healthcare services utilization.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank AcaciaTools for their medical writing and editing services.

Footnotes

Contributorship: N Pages and S Nisse-Durgeat contributed to the writing of the manuscript. C Bedel and L Betito: reviewed the manuscript. F Picard, F Barritault, W Amara, S Lafitte, P Maribas, P Abassade, J Ph Labarre, R Boulestreau, H Chaouky, M Abdennadher, H Lemieux, R Lasserre, B Diebold: usage and inclusion of patients in SATELIA® Cardio.

Conflict of interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. N Pages is founder and CEO of NP Medical. H Chaouky, L Betito, and C Bedel are employees of NP Medical. S Nisse-Durgeat is an employee of WeHealth™ Digital Medicine/Servier.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by WeHealth™ Digital Medicine.

Guarantor: Not applicable.

ORCID iD: N Pages https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9074-4016

References

- 1.Farias FAC, Dagostini CM, Bicca YA, et al. Remote patient monitoring: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health 2020; 26: 576–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor ML, Thomas EE, Snoswell CL, et al. Does remote patient monitoring reduce acute care use? A systematic review. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e040232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashi N, Karunanithi M, Fatehi F, et al. Remote monitoring of patients with heart failure: an overview of systematic reviews. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrès E, Talha S, Zulfiqar AA, et al. Current research and new perspectives of telemedicine in chronic heart failure: narrative review and points of interest for the clinician. J Clin Med 2018; 7: 544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varma N, Love CJ, Michalski J, et al. TRUST investigators. Alert-based ICD follow-up: a model of digitally driven remote patient monitoring. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2021; 7(8): 976–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Versteeg H, Timmermans I, Widdershoven J, et al. Effect of remote monitoring on patient-reported outcomes in European heart failure patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: primary results of the REMOTE-CIED randomized trial. Europace 2019; 21: 1360–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hindricks G, Varma N, Kacet S, et al. Daily remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: insights from the pooled patient-level data from three randomized controlled trials (IN-TIME, ECOST, TRUST). Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 1749–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avram R, Ramsis M, Cristal AD, et al. Validation of an algorithm for continuous monitoring of atrial fibrillation using a consumer smartwatch. Heart Rhythm 2021; 18(9): 1482–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gawałko M, Duncker D, Manninger M, et al. The European TeleCheck-AF project on remote app-based management of atrial fibrillation during the COVID-19 pandemic: centre and patient experiences. Europace 2021; 23: 1003–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pluymaekers NAHA, van der Velden RMJ, Hermans ANL, et al. On-demand mobile health infrastructure for remote rhythm monitoring within a wait-and-see strategy for recent-onset atrial fibrillation: TeleWAS-AF. Cardiology 2021; 146: 392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koehler J, Stengel A, Hofmann T, et al. Telemonitoring in patients with chronic heart failure and moderate depressed symptoms: results of the telemedical interventional monitoring in heart failure (TIM-HF) study. Eur J Heart Fail 2021; 23: 186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winkler S, Koehler K, Prescher S, et al. Is 24/7 remote patient management in heart failure necessary? Results of the telemedical emergency service used in the TIM-HF and in the TIM-HF2 trials. ESC Heart Fail 2021; 8(5): 3613–3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inglis SC, Clark RA, Dierckx R, et al. Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 10: CD007228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galinier M, Roubille F, Berdague P, et al. Telemonitoring versus standard care in heart failure: a randomised multicentre trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2020; 22: 985–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Douarin Y, Traversino Y, Graciet A, et al. participants of Giens XXXV Round Table Health, economy. Telemonitoring and experimentation in telemedicine for the improvement of healthcare pathways (ETAPES program). Sustainability beyond 2021: what type of organisational model and funding should be used? Therapie. 2020;75:43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. Liste des solutions techniques déclarées conformes au cadre règlementaire de la télésurveillance. Accessed at: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/liste_des_fournisseurs_de_solutions_techniques_maj_le_02_08_2021_.pdf (Last accessed on 6 August 2021)

- 17.Kuhn E, Rogge A, Schreyer K, et al. Apps auf Rezept in der Arztpraxis, aber wie? Fallbasierter Problemaufriss medizinethischer Implikationen bei der Nutzung von DiGA [Apps on Prescription in the Medical Office, but how? A Case-based Problem Outline of Medical-ethical Implications of DHA Usage]. Gesundheitswesen. 2021 May 6. German. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Düvel JA, Gensorowsky D, Hasemann L, et al. Lösungsansätze für den Zugang digitaler Gesundheitsanwendungen zur Gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung: eine qualitative Studie [Digital Health Applications: A Qualitative Study of Approaches to Improve Access to Statutory Health Insurance]. Gesundheitswesen. 2021 Feb 26. German. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2019 Home Health Prospective Payment System Rate Update and CY 2020 Case-Mix Adjustment Methodology Refinements; Home Health Value-Based Purchasing Model; Home Health Quality Reporting Requirements; Home Infusion Therapy Requirements; and Training Requirements for Surveyors of National Accrediting Organizations. Final rule with comment period. Fed Regist 2018; 83: 56406–56638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. Accessed at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes (Last accessed on 6 August 2021)

- 21.Vanier A, Oort FJ, McClimans L, et al. Response Shift - in Sync Working Group. Response shift in patient-reported outcomes: definition, theory, and a revised model. Qual Life Res. 2021; 30(12): 3309–3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Spall HGC, Rahman T, Mytton O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of transitional care services in patients discharged from the hospital with heart failure: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19: 1427–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2016; 69: 1167. English, Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2016.11.005. Erratum in: Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2017 Apr;70(4):309-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seferovic PM, Ponikowski P, Anker SD, et al. Clinical practice update on heart failure 2019: pharmacotherapy, procedures, devices and patient management. An expert consensus meeting report of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 1169–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koehler F, Koehler K, Deckwart O, et al. Efficacy of telemedical interventional management in patients with heart failure (TIM-HF2): a randomised, controlled, parallel-group, unmasked trial. Lancet 2018; 392: 1047–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021; 42: 3599–3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Journal Officiel de la République Française n°0315 du 30 Décembre 2020. Texte n°72. Arrêté du 23 décembre 2020 portant cahiers des charges des expérimentations relatives à la prise en charge par télésurveillance mis en œuvre sur le fondement de l’article 54 de la loi n° 2017-1836 de financement de la sécurité sociale pour 2018.