Abstract

Single IRB (SIRB) consultation resources were established by the Utah Trial Innovation Center to assist and educate investigative teams prior to the submission of funding applications for multisite, cooperative research. Qualitative analysis of the written consultation materials and meeting minutes revealed the most common areas of education needed by investigative teams, including (a) the differences and relationships between the IRB and a Human Research Protection Program (HRPP); (b) the main phases of the SIRB process; and (c) the use of technology platforms for documentation of SIRB review processes. For investigative teams who are inexperienced with using a SIRB, such consultation in the pre-award period is likely to fill in knowledge gaps and improve the study start-up process.

Keywords: Single IRB, Education, Multicenter trials, Consultations, Human research protection program

1. Introduction

A significant change to the Federal Policy for the Protections of Human Subjects is the mandate to use a single institutional review board (SIRB) for multi-site studies [1]. Since this mandate went into effect on January 20, 2020, institutions that receive federal funding for multi-site studies are generally required to use one IRB for review of a project, instead of seeking approval from all the IRBs that may be affiliated with each site individually. The Trial Innovation Network (TIN), funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), recognized the need to educate and assist investigators who did not have prior experience using a SIRB review model. As part of its goal to address roadblocks and accelerate clinical research [2], the TIN's three Trial Innovation Centers (TICs) provide consultation to investigators initiating and conducting clinical trials. SIRB consultation resources were established to not only educate investigators about the costs and components of SIRB review, but also to assist the investigators by providing coordination of the SIRB review process for trials using one of the TIC SIRBs. The TICs collaborate with the existing IRBs at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, the University of Utah, and Vanderbilt University, to provide SIRB coordination and review of TIN-selected projects.

One challenge with the implementation of SIRB review is the lack of preparedness or experience of investigative teams to secure SIRB review for all sites in multi-center studies [[3], [4], [5]]. Because the use of SIRB review has not been previously required, many investigative teams are most familiar with the IRB at their home institution, and do not have practical experience working with a variety of IRBs for their projects. In addition, though lead investigators of multi-site research may have experience working with multiple co-investigators, they are often inexperienced in managing and overseeing the SIRB review process for multiple sites. The University of Utah TIC has conducted over 70 pre-funding SIRB consultations with investigators across the country since 2016, which helped us develop best practices to better prepare investigators for SIRB processes. The purpose of this manuscript is to describe the most observed knowledge gaps of investigators in SIRB consultations performed by the University of Utah TIC and provide suggestions for how best to educate investigative teams about the SIRB process.

2. Methods and design

An examination of the written materials documenting SIRB consultations is one way to understand investigative teams' needs while preparing for SIRB submission and review. Though overall TIN satisfaction surveys were sent to investigative teams for feedback, there were no specific questions that allowed for direct feedback about the sIRB consults; however, each consult's written meeting materials offer a valuable perspective. Investigators interested in using the TIC SIRB for review of their multi-site projects requested a consult using the TIN submission portal. Requests for consult were distributed evenly between the three TICs. For consults requesting SIRB support, the Utah TIC contacted the investigators they had been assigned to schedule a virtual consult, which lasted between 60 and 90 min. The consults typically included investigators and study personnel, a TIC project manager, and a TIC Director. All of the consults discussed multi-site, prospective, health-related research projects. Standard SIRB process-related topics were included on the agenda for each consult, but discussion was catered to the specific needs of the project. For example, while all consults included a discussion item about establishing reliance agreements between the SIRB and the participating sites, discussion would be catered to the specific participating sites' experience and paperwork needs. For sites already using established, national reliance agreements, the discussion would require less time and detail. For sites that had not used reliance agreements before, the discussion would include a more in-depth discussion and instruction. The standard SIRB consult agenda included the following topics: reliance agreements and decisions, phases of the SIRB review process, IT platforms for documenting SIRB review, TIC resources for navigating and coordinating SIRB submissions, and study activation procedures post-SIRB approval. Presentation slides were used by the TIC personnel during the consult to present the agenda and provide information about each topic.

Written materials from the 20 most recent SIRB consults conducted by the Utah TIC were selected for review, performed from 2019 to 2021. Written materials included (a) SIRB consult presentation slides prepared by the TIC personnel, (b) SIRB consult meeting minutes prepared by the TIC personnel, and (c) SIRB revision letters prepared by the SIRB staff after a project was submitted to the SIRB. SIRB consult meetings were not recorded, thus transcripts of these meetings were not available for analysis. SIRB consultations performed between 2019 and 2021 were selected because the written materials documenting SIRB consults were the most robust during this period, allowing for thorough analysis. Meeting minutes and presentation slides for each meeting were analyzed to identify the most-discussed topics of in-depth education during SIRB consults. SIRB revision letters were analyzed to determine if there were common errors in the submissions that were related to topics of education during the SIRB consults.

A qualitative, descriptive approach was used in this study [6]. Consistent with this conceptual framework, a content analysis was conducted on the written materials to create codes that captured the most common topics discussed. A qualified member of the research team who was not present for the SIRB consults read all the written materials and applied open coding on the data. For example, if the meeting minutes mentioned “discussed what a human research protection program (HRPP) was” this was coded as “what is an HRPP?”. When reviewing presentation slides, it was noted that after some consults, the slides were amended based on the previous meeting's discussion in anticipation of potential questions by investigators in future consults. The TIC personnel's iterative process of evaluating the discussion foci of each consult and preparing for future consults with that information provided another source of data for understanding the common areas that investigative teams needed addressed. Codes were applied that captured the key topics of the presentations. The codes from the slides and meeting minutes were summarized based on similarity within and across the materials to create categories. Other members of the research team, SIRB staff, and TIC personnel who regularly attended the SIRB consults reviewed the codes and themes to determine if they were consistent with the shared experience for the consults, providing clarification and additional details on the common in-depth discussion topics.

3. Results

Results are presented as the most common in-depth discussion questions and topics with investigative teams during consultations about the SIRB process for their research. Results include the following questions and topics: the differences and relationship between the IRB and an HRPP; the main phases of the SIRB process; and the use of IT platforms for documentation of SIRB review processes.

3.1. Differences and relationship between the IRB and an HRPP

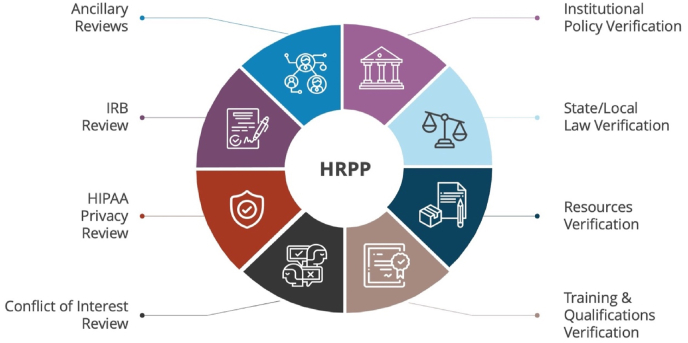

Every consult discussed the difference between an IRB and the other related review components that constitute the HRPP, such as verification of compliance with local laws and policies, conflict of interest review, and other ancillary safety, resource, and scientific reviews (Fig. 1). In-depth discussion shows that many investigators were not aware that their institution had an HRPP and that IRB review is only one facet of ensuring protection of human participants. Even though the concept of an HRPP has existed at research institutions for many years, we found investigators were relatively unaware of the existence of an HRPP within the organization itself.

Fig. 1.

A Human Research Protection Program (HRPP). A variety of review components constitute the full HRPP.

A common misconception for investigators was that SIRB approval of the protocol was all that was required for the protocol to be initiated at each participating site. This misconception required frequent corrections during the consults to help investigators understand that each participating site's HRPP also had review and approval responsibilities that must be completed before research activities could proceed. Investigators often did not realize that each participating research institution, through the HRPP, still retained authority for the conduct and oversight of the research.

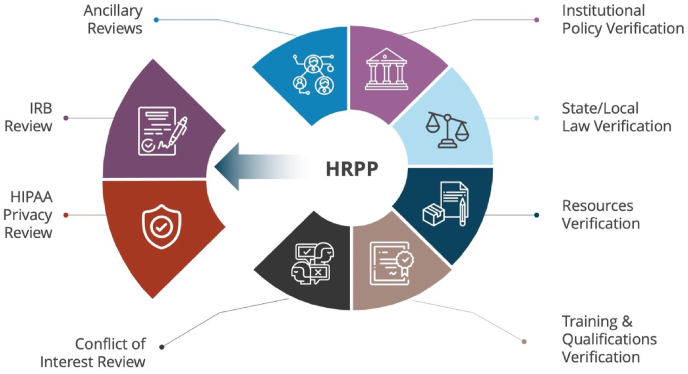

Presentation slides used in the consults helped to emphasize these two distinct roles by visually representing the IRB (often combined with HIPAA Privacy Review) as a component that could be separated from the HRPP (Fig. 2). While this separation occurs when a SIRB is used, it does not remove or replace the HRPP's responsibilities. Re-enforcing the need for two approvals—SIRB and HRPP approval—was a critical concept for the investigative team personnel who were responsible for obtaining required approval documentation before research procedures began.

Fig. 2.

A Human Research Protection Program using a Single IRB. Depiction of a HRPP when IRB and HIPAA Privacy Review activities are performed externally by a Single IRB.

3.2. The main phases of the SIRB process

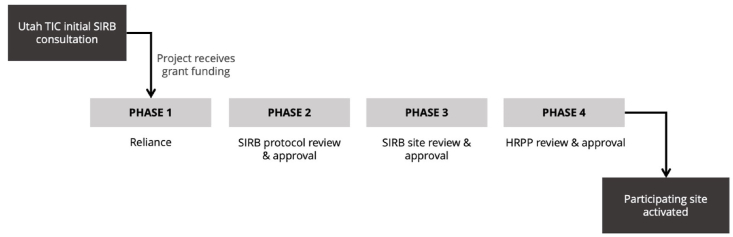

Investigators required in-depth education and guidance on the timing and requirements for the SIRB submission and review process if their project received grant funding. Presentation slides used during the consult included a visual representation of the workflow (Fig. 3), helping to orient investigators to their current process phase and the steps that would be taken after funding was received.

Fig. 3.

Phases of the Utah trial innovation center single IRB review process.

For the purposes of this paper, the details of the SIRB submission and review process used by the University of Utah TIC will not be discussed in detail. However, it is important to present the process in general terms in order to describe the guidance that investigators needed in the SIRB consult. We taught investigators that there were four main phases of the SIRB process: the reliance phase, the SIRB protocol review and approval phase, SIRB site review and approval phase, and the HRPP review and approval phase.

Reliance Phase: In-depth discussion revealed that investigators were largely unaware that reliance relationships would need to be established in writing between each participating site and the SIRB prior to the SIRB's willingness to provide review for the sites. Providing details on how this would be completed was helpful in setting their expectations for the timing of the full process. The SIRB performed a separate reliance consultation with lead investigators in the post-award period to help them understand this requirement in detail.

SIRB Protocol Review & Approval Phase: Our analysis showed that investigators were generally comfortable with the requirements in this phase, given that they had interacted with IRB review processes on past projects; this was not a topic that showed much in-depth discussion. However, the details for interacting with the SIRB's electronic submission system were commonly discussed in-depth, as discussed in the next section.

SIRB Site Review & Approval Phase: The documents indicated that investigators were also comfortable with the SIRB submission requirements in this phase, but the TIC personnel had to reinforce components of the reliance phase and the HRPP review and approval phase that impact the SIRB site review and approval. This included education that the SIRB would need pertinent details from the HRPP related to site-specific laws and policies before the SIRB review could be completed. Additionally, investigative teams were often reminded that the SIRB would not be able to approve the study without the HRPP documenting the institution's decision to rely.

HRPP Review & Approval Phase: As previously noted, investigators were new to the concept of the HRPP, and thus discussion about the HRPP review phase was lengthier. TIC personnel emphasized the need to submit appropriate study documentation to the HRPP, complete all HRPP requirements, and then receive HRPP approval. Investigators were also informed that the site could only be activated to begin research procedures once SIRB and HRPP approval were both received for the site.

3.3. IT platforms for facilitating SIRB review

To streamline the SIRB review process, the use of electronic systems to coordinate the flow of information and the timing of actions is often key. It was expected that investigators would require additional instruction during the consults about the use of IT platforms with which they were not familiar. The platform TIN SIRBs use to document reliance is the IRB Reliance Exchange system, or IREx [7]. This platform connects institutions’ IRBs, HRPPs, and study teams; enables documentation of reliance relationships in a central location; and captures local review and institutional profiles. During the consults, introductory information about IREx was provided to the investigators, including expectations for its use if the project received funding and moved forward. More detailed information about IREx and the SIRB review platforms was provided later if the project was funded and the systems would be used.

The SIRB revision letters did not yield any common themes that coincided with those found in the consult presentation slides and meeting minutes. Additional discussion about the implication of this finding follows.

4. Discussion

SIRB consultations are an important mechanism at the University of Utah TIC for educating investigators about navigating SIRB requirements, addressing misconceptions about the participating site HRPP and SIRB reliance relationship, and preparing investigators to use unfamiliar electronic platforms. The findings of this qualitative content analysis suggest that SIRB consults in the pre-award period can be a useful education mechanism. These findings open the door to future research on improving the SIRB process and increasing the knowledge of investigative teams in a prospective manner.

There are anticipated limitations to the findings of this content analysis. Such an analysis does not and cannot answer all the questions about the education needed by investigative teams and whether such education results in a more efficient SIRB review process. Additionally, this project did not assess whether there were other measurable factors that influenced an investigative team's needs, such as level of IRB and SIRB experience within the team, career stage (early-, mid-, late-career) of the investigator, and past working experience with the participating sites. Another limitation previously mentioned is that investigative teams were not purposefully asked for feedback after their participation in the SIRB consult. Such data directly from the investigative team would have been valuable for understanding the perceived benefits of SIRB consults, how to improve the educational content of consults, and the impact SIRB consults may have had on multi-site SIRB process management.

We were surprised that the SIRB revision letters did not show any meaningful thematic overlap with the misunderstandings and questions documented in the SIRB consult documentation; we initially expected there to be a greater indication of knowledge gaps on the part of the investigative team during SIRB application submission and review, resulting in revisions. However, our analysis of SIRB consult documentation shows that SIRB applications were not a topic investigative teams asked many questions about, and thus there was little in-depth discussion on this topic recorded. As such, it is possible that SIRB revision letters were not an appropriate document to assess the effects of the education investigative teams received in the consults, as the teams were already prepared to engage with the SIRB application process effectively. It is also possible that the education received during SIRB consults allowed investigative teams to avoid certain mistakes that would have been caught by the SIRB otherwise; further analysis and comparison to a control group would provide clarity to this question.

Our findings are consistent with the literature that describes both perceived and experienced challenges of SIRB review. Others have cited the challenge researchers and institutions can experience when trying to differentiate the roles of the IRB from the HRPP [[3], [4], [5],[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]] as well as the difficulty navigating unfamiliar IT platforms [[13], [14], [15]]. Our results show that these challenges are a reality and that SIRB consults may be an avenue for reducing challenges.

Other institutions may benefit from adopting a similar SIRB consultation process for investigators in the pre-award period, to ensure they are prepared to initiate their multi-site studies efficiently if funding is received. Such consultation processes may be valuable to ensure that investigators are compliant with not only the SIRB mandate, but with institutional policies and requirements overseen by HRPPs. Additionally, investigators can benefit from pre-award planning for any potential SIRB costs to ensure that these are included in the budget.

We recommend that institutions have materials available that clearly describe the full process for relying on a SIRB, and then encourage discussion about the SIRB process through consultations and other education events. Investigators who consulted with the University of Utah TIC found the materials we provided valuable. The discussion increased investigators’ knowledge and comprehension, as evidenced by the questions generated during consultations and the ease with which investigators were able to complete the SIRB review process. SIRB educational tools reflective of the materials used in the SIRB consultation process are publicly available on the Trial Innovation Network website [16].

We also recommend that education efforts about HRPPs continue, whether such education comes from research institutions or from funding agencies. It is noted, however, that some investigators may need a more nuanced understanding of HRPP responsibilities, particularly for participating sites that do not routinely conduct research—such as private medical practices, community organizations, and certain governmental branches—and may not have a formal program to address human research protection elements beyond IRB review. IRBs and the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Human Research Protections may be in the best position to provide this level of guidance and education.

5. Conclusion

Investigative teams who are new to using a single IRB for multisite research are likely to benefit from the additional education that can be provided during expert consultation in the pre-award setting. Standardized tools and methods for engaging investigative teams are key to ensuring effective education. Such education is an important step for ensuring efficient clinical trial initiation.

Funding sources and support

This work was supported by the Utah Trial Innovation Center funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) [U24TR001597]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Protection of Human Subjects, 45 Code of Federal Regulations 46.114(b)(1). [PubMed]

- 2.Bernard G.R., Harris P.A., Pulley J.M., et al. A collaborative, academic approach to optimizing the national clinical research infrastructure: the first year of the Trial Innovation Network. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2018;2(4):187–192. doi: 10.1017/cts.2018.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burr J.S., Johnson A.R., Vasenina V., et al. Implementing a central IRB model in a multicenter research Network. Ethics Hum. Res. 2019;41(3):23–28. doi: 10.1002/eahr.500016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klitzman R., Pivovarova E., Lidz C.W. Single IRBs in multisite trials: questions posed by the new NIH policy. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2061–2062. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson A.R., Kasimatis Singleton M., Ozier J., et al. Key lessons and strategies for implementing single IRB review in the Trial Innovation Network. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2022;6(1):e53. doi: 10.1017/cts.2022.391. Published 2022 Apr 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandelowski M. Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Res. Nurs. Health. 2000;23(3):246–255. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200006)23:3<246::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IREx. Irbexchange.Org. 2021. https://www.irbexchange.org/p/ Published. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henrikson N.B., Blasi P.R., Corsmo J.J., et al. You really do have to know the local context": IRB administrators and researchers on the implications of the NIH single IRB mandate for multisite genomic studies. J. Empire Res. Hum. Res. Ethics. 2019;14(3):286–295. doi: 10.1177/1556264619850440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu A., Holl J.L., Raval M.V. Pediatric specific challenges of the single institutional review board mandate. Trials. 2022;23(1):224. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06141-y. Published 2022 Mar 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lidz C.W., Pivovarova E., Appelbaum P., Stiles D.F., Murray A., Klitzman R.L. Reliance agreements and single IRB review of multisite research: concerns of IRB members and staff. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2018;9(3):164–172. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2018.1510437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn C., Kaufmann P., Bang S., Calvert S. Resources to assist in the transition to a single IRB model for multisite clinical trials. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2019;15 doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100423. Published 2019 Jul 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flynn K.E., Hahn C.L., Kramer J.M., et al. Using central IRBs for multicenter clinical trials in the United States. PLoS One. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corneli A., Dombeck C.B., McKenna K., Calvert S.B. Stakeholder experiences with the single IRB review process and recommendations for food and drug administration guidance. Ethics Hum. Res. 2021;43(3):26–36. doi: 10.1002/eahr.500092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoffel B., Sorkness C., Pech C. Use of a single, independent IRB: case study of an NIH funded consortium. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2017;8:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray A., Pivovarova E., Klitzman R., Stiles D.F., Appelbaum P., Lidz C.W. Reducing the single IRB burden: streamlining electronic IRB systems. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2021;12(1):33–40. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2020.1818877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Single IRB: Tools and Materials for IRBs. Trialinnovationnetwork.Org. 2021. https://trialinnovationnetwork.org/tools-and-materials-for-irbs/?key-element=1603 Published. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.