Abstract

Background

Whilst the management of Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) has evolved in response to the emerging data, treating such patients remains a challenge, and many treatments lack robust clinical evidence. We conducted a survey to evaluate Intensive Care Unit (ICU) management of COVID-19 patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure and compared the results with data from a similar survey focusing on Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) that was conducted in 2013.

Methods

The questionnaire was refined from a previous survey of ARDS-related clinical practice using an online electronic survey engine (Survey Monkey®) and all UK intensivists were encouraged to participate. The survey was conducted between 16/05/2020 and 17/06/2020.

Results

There were 137 responses from 89 UK centres. Non-invasive ventilation was commonly used in the form of CPAP. The primary ventilation strategy was the ARDSnet protocol, with 63% deviating from its PEEP recommendations. Similar to our previous ARDS survey, most allowed permissive targets for hypoxia (94%), hypercapnia (55%) and pH (94%). The routine use of antibiotics was common, and corticosteroids were frequently used, usually in the context of a clinical trial (45%). Late tracheostomy (>7 days) was preferred (92%). Routine follow-up was offered by 66% with few centres providing routine dedicated rehabilitation programmes following discharge. Compared to the ARDS survey, there is an increased use of neuromuscular agents, APRV ventilation and improved provision of rehabilitation services.

Conclusions

Similar to our previous ARDS survey, this survey highlights variations in the management strategies used for patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure due to COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, critical illness, intensive care, critical care, survey

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a novel disease caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), has since caused an extreme burden on critical care units worldwide.1–3 As of December 2020, an estimated 250,000 patients have been admitted to hospitals in the UK. 4 Data obtained from hospitals in England, Wales and Northern Ireland between the period 01/03/2020 to 18/12/2020, suggests that there were 18,612 COVID-19 related ICU admissions with a mortality of 36%, while 8% were still receiving critical care. 5 Guidelines for ventilatory support and ICU Covid-19 management were rapidly generated, primarily from expert opinion based on accepted care bundles used to manage Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). 6 However, clinicians soon realised that COVID-19 was a distinct complex multi-system clinical entity that might not behave or respond to treatment in the same way as ‘typical’ ARDS. 7 , 8

Clinicians were forced to learn and adapt quickly to deal with this new disease during the first wave of the pandemic. For example, there is evidence that the use of invasive ventilation reduced over time. 9 We have previously reported a survey on intensive care physicians’ perceptions of diagnosis and management of patients with ARDS. 10 To explore how UK critical care physicians adapted their usual management of acute hypoxic respiratory failure (AHRF) for COVID-19 and compare with our previous results, we modified our survey to be specific to COVID-19 and address the following areas:

Diagnostic definitions for acute respiratory failure associated with COVID-19

Relative frequency of different pharmacological and ventilatory management strategies adopted to treat COVID-19

Availability of post ICU discharge follow-up and rehabilitation measures for COVID-19 patients

Participation in clinical trials investigating novel COVID-19 treatments

Methods

We refined a previous survey of perceptions and management of ARDS practice to address key questions related to the care of critically ill patients with COVID-19 and to compare our findings with previously published comparative data where available. 10 The refined survey was specific to adult (>18 yrs.) ICU patients with AHRF, presumed or confirmed to be secondary to COVID-19.

We developed an electronic survey (Survey Monkey) accessible through a hyperlink or QR code. The survey contained 27 questions (18 questions modified from the original survey and 9 additional questions novel for this survey) and was piloted internally by the investigator team and subsequently with independent critical care consultants at University Hospital Southampton (online Appendix 1). We incorporated the following sections: (i) contextual information describing the type, size and location of the intensive care unit being surveyed; (ii) diagnostic and phenotypic description of COVID-19; (iii) management approaches including ventilation, fluid balance and pharmacological strategies; (iv) follow-up including post discharge approaches and rehabilitation programmes offered; (v) involvement of patients in clinical trials; and (vi) availability of health informatics to enable rapid identification of patients.

Intensive care physicians across the UK were encouraged to participate by dissemination to local intensive care teams through Critical Care Regional Network leaders and promotion in the Intensive Care Society (ICS) newsletter. Senior (ideally consultant level) clinicians from every intensive care unit were approached by the Critical Care Network leads and asked to complete the survey. Because of the urgency of acquisition of this data to help steer ongoing guideline development, the survey only remained open online for a one month period between 16 May 2020 and 17 June 2020.

Results were analysed with the help of the SurveyMonkey system and GraphPad Prism software version 8.0.0 La Jolla California, USA. Numerical data are presented as percentages of the total respondents to each particular question. Survey data relevant to COVID-19 were compared to previously collected data in relation to adult ARDS.

Results

Characteristics of respondents

One hundred and thirty-seven responses were received from 89 UK centres between 16 May and 17 June 2020 (Figure 1). Of these centres, 74 (84.3%) from England and the rest were from Wales (4.5%), Scotland (5.6%) and Northern Ireland (5.6%) respectively. This represents approximately 27% of the hospitals participating in the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC: Wales, England, Ireland) and Scottish Intensive Care Society Audit Group (SICSAG) Case-Mix programmes. 11 , 12 The majority of respondents were consultants (90%), with the remainder being SpR/StRs level (6.6%) and clinical/research fellows (2.2%). Most units were described by the respondents as general intensive care units (91.2%), followed by specialist cardiac (2.9%) and others (5.8%) included specialist neurology and hepatology units. The median number of ICU beds reported by respondents was 16 (range 4–100) with additional COVID-19 surge capacity to a median of further 21 ICU beds (range 0–170). The median number of in-patient beds per hospital was 600 (range 11–1,500).

Figure 1.

A pictorial representation of the locations of hospitals from which the responses obtained.

Disease classification

When asked about the presence of the H and L clinical phenotypes which has been suggested as distinct clinical entities in COVID-19 pneumonia, 7 almost all (>99%) respondents answered these questions regarding the existence of such phenotypes and whether recognising such phenotypes altered management approaches. The majority of responders (40.4%) reported that it was neither easy nor difficult to differentiate H and L sub-types, and 49.6% reported that they did not change their ventilation strategy according to these conceptual phenotypes. In COVID-19 AHRF, ARDS was mainly diagnosed using the Berlin Definition (57.8%). Others used no diagnostic criteria (22.2%) or a combination of American European Consensus Criteria (AECC), Lung Injury score and Berlin Definition of ARDS (10.4%).

Specialist imaging for diagnosis and management

This question was based on the use of specialist imaging for the diagnosis and management of patients with AHRF in COVID-19. Lung USS was performed primarily during clinical deterioration (44.3%) and frequent use was rare (22.1%). Similar to the USS, a thoracic CT scan was reportedly undertaken mainly during clinical deterioration by 70.8%. Transthoracic echocardiogram was performed on admission and frequently by 34.8%, and during clinical deterioration in 32.6% and admission and infrequently by 29.6%.

Pharmacological agents

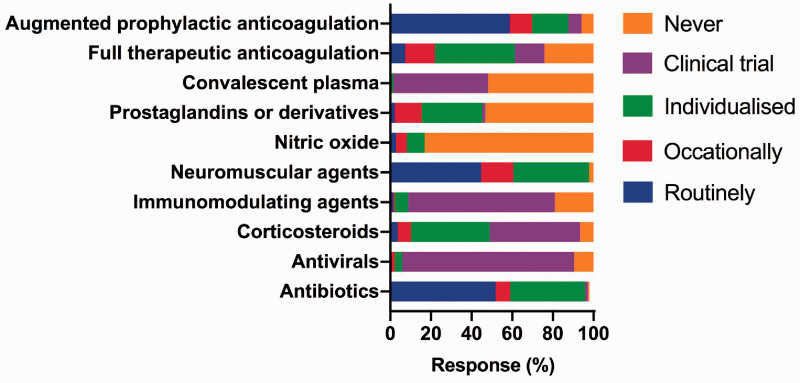

The responses to these questions were categorised as “routinely”, “occasionally”, “individualised”, “part of clinical trial” and “never”. Similar to our previous survey, for the purpose of this report, we pooled the “occasional” and “individualised according to patient” categories together (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The pharmacological therapies used to treat COVID-19 patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure.

Antibiotics and antivirals

Antibiotics were given on admission routinely by 51.8% with a COVID-19 specific protocol (29.3%) or as for standard use in community-acquired pneumonia (48.1%). The antibiotic guidance was based on microbiology (51.9%), blood C-reactive protein (CRP) (29.3%) or serum procalcitonin (PCT) (59.4%) concentrations. Antivirals were mainly given in the context of a clinical trial.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids were used in some form by 93.4% and of which 44.5% were reported to be part of a clinical trial. While some used corticosteroids occasionally or in an individualised patient fashion (45.3%), routine use was rare (3.7%). Methylprednisolone was the most commonly used steroid outside the context of a clinical trial, and the most typical dose was 1 mg/kg/day (57.1%) with a duration of <7 days (46.8%). The timing of the initiation of steroids outside a clinical trial was variable: with 39.3% starting within 7–14 days of ICU admission, and 2.3%, 6.7%, 15.7% and 19.1% at <72 hours, <7 days >14 days or ‘anytime’ respectively. The reasons for the initiation of corticosteroids outside a clinical trial were as an anti-inflammatory (21.3%), anti-fibrotic (26.2%) or to treat bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia (14.8%) or a combination of all of these (21.3%).

Anticoagulation

When asked regarding the use of therapeutic anticoagulation or augmented anticoagulation in the absence of clinical thromboembolism, all respondents (100%) answered this question. Therapeutic (rather than prophylactic) anticoagulation in the absence of a clinical thromboembolism was used ‘routinely’, ‘individualised or occasionally’, and ‘never’ by 7.3%, 54.0% and 24.1% respectively. 14.6% used therapeutic anticoagulation in the context of a clinical trial. Augmented anticoagulation was used routinely more often (58.8%), and on an individualised/occasional basis by 28.7%. We did not explore the rationale for both full/therapeutic and augmented anticoagulation.

Other pharmacotherapies

The use of other pharmacotherapies, including any other immune-modulating agents, neuromuscular agents, pulmonary vasodilators and convalescent plasma, are detailed in Figure 2.

Use of high flow nasal oxygen and non-invasive ventilation

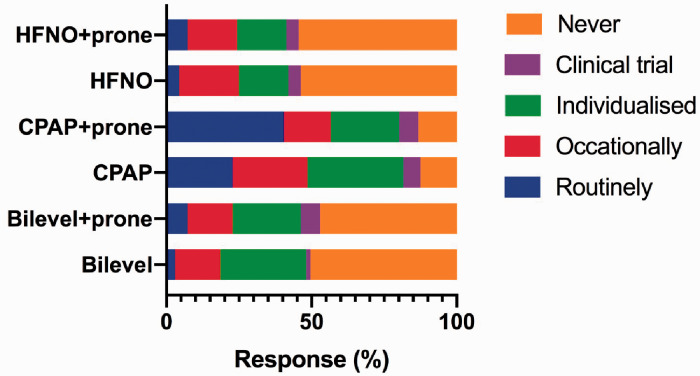

The use of HFNO, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and bilevel positive airway pressure ventilation (BiPAP) was assessed, including in the context of prone positioning, and nearly all respondents answered (99.2%). The use of CPAP with or without proning was the commonest method of oxygenation beyond face mask oxygen (Figure 3). We did not perform analysis of individual responses and as a result, not able to report on the use of combined interventions.

Figure 3.

The use of non-invasive ventilation, CPAP and high flow nasal oxygen.

CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; HFNO: high flow nasal oxygen.

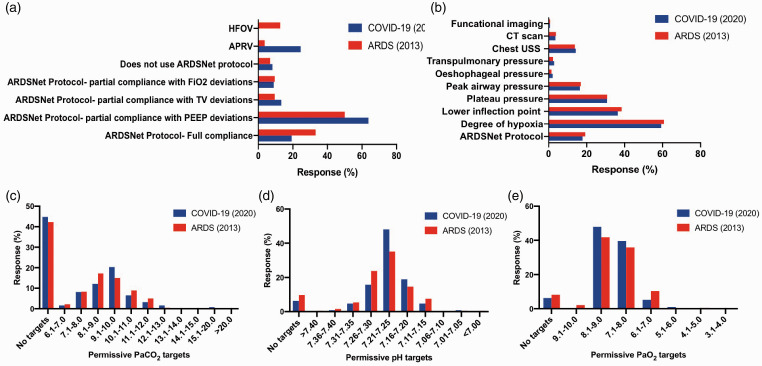

Invasive ventilation strategies, targets and rescue therapies

The commonest indication for intubation was a combination of both work of breathing and oxygenation indices (81.0%). The primary ventilation strategy was partial compliance with the ARDSNet protocol with deviation from PEEP recommendations (63.7%) with a tidal volume target of 6.1–8.0 mL/kg predicted body weight (PBW) (60.3%) followed by 4.0-6.0 mL/kg/PBW (38.2%). The PEEP titration was commonly guided by the degree of hypoxia (60.8%). The majority adopted permissive targets with a hypoxic range of 7.1-9.0 kPa (87.5%). Details of the primary ventilation strategy, variables used to guide titration of PEEP, the permissive targets for hypercapnia, pH and hypoxia in comparison to the previous survey are presented in Figure 4. Rescue therapies included prone positioning (99.3%), recruitment manoeuvres (51.5%), ECMO (46.3%), and pulmonary vasodilators (35.3%).

Figure 4.

Comparison of ARDS (2013) and COVID-19 surveys conducted for to assess the primary ventilation strategy (a), variables used for the guidance for positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) titration (b), and permissive targets for PaCO2 (c), pH (d) and PaO2 (e).

Prone positioning

Prone positioning was used based on PaO2/FiO2 by 69.3%, routinely (17.5%), and as a rescue measure (13.1%). The most frequent prone durations were 16–18 hours (65.9%) and 12–16 hours (27.9%). An unlimited number of prone cycles were performed by 47.4%, and 43.9% continued proning until improvements in PaO2/FiO2 were seen. Sixty percent of respondents reported the presence of a dedicated prone team.

Fluid balance

Most responders (86.7%) would target a euvolaemic fluid balance, and 8.9% targeted a “dry” state. The preferred resuscitation fluids were crystalloids (89.8%). Most (53.5%) would use a combination of diuretics, fluid restriction and haemofiltration to achieve their fluid balance targets.

Tracheostomy

A routine tracheotomy was considered by 47.5% and occasionally by 44.5%. However, on both occasions, the preferred timing was after 7 days (late). Tracheostomy was performed rarely by just 7.3%.

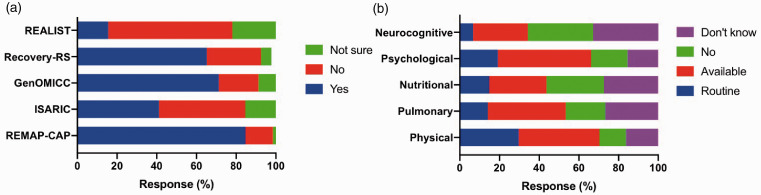

Participation in clinical research and data collection

There was excellent participation in clinical research; the studies were REMAP-CAP (84.6%), ISARIC (41.0%), GenOMICC (71.2%), Recovery Respiratory Support (68.2%) and REALIST (15.5%) (Figure 5). Pre-existing COVID-19 specific data collection was available in 93.8% centres. This was research specific in 32.6% of centres.

Figure 5.

Clinical research participation (a) and availability of rehabilitation facilities (b) post-ICU discharge.

Follow-up and the availability of rehabilitation programmes

COVID-19 routine follow-up was available for this cohort of patients following hospital discharge in 66.2%. Physical, pulmonary, nutritional, psychological and neurocognitive rehabilitation was available at 29.6%, 14.1%, 14.8%, 19.1% and 6.7% of the respondent’s units, respectively (Figure 5). We did not differentiate if these rehabilitation measures are specific to COVID-19 or common for all ICU patients.

Discussion

This was a cross-sectional survey conducted among the UK intensive care physicians describing the management of patients admitted with COVID-19 related acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The response rate lower than would normally be anticipated, but in the context of the initial surge of the pandemic with demanding clinical duties, this level of response may be understandable, and we believe still contributes meaningful and useful results. Most of the respondents were consultants from general ICUs across the UK. This survey demonstrates significant variations in the management of patients with COVID-19 related AHRF across the UK. This is the first survey of this nature to be conducted in the UK and may provide helpful insights for clinicians and guidelines writers as the pandemic evolves.

The key findings concerning clinical phenotypes and respiratory support were: (i) most clinicians were not able to differentiate the claimed sub-types of COVID-19 pneumonia, 7 in general described a spectrum of phenotypes over the course of the illness, and most did not base their clinical management on a distinction between such phenotypes; (ii) Most clinicians reported using non-invasive ventilation with the preferred choice being CPAP with self-proning; (iii) Bilevel NIV and HFNO were used by 50 and 40–45% of respondents respectively, reflecting a highly polarised response for the use of bilevel NIV and HFNO with a roughly 50:50 divide. (iv) a majority of respondents reported that their ventilation approach was based on the ARDSnet protocol for tidal volumes but with deviations from the recommended PEEP settings; (v); permissive targets were allowed for pH, PaCO2 and PaO2 and were similar to the previous ARDS survey responses. Overall, compared with the previous ARDS survey, full compliance of ARDSnet ventilation protocol was less (19.3% vs 34%) with increased use of APRV (24.4% vs 3.7%) in COVID-19 patients. Routine and late (>7 days) tracheostomy was the preferred options in both surveys. 10

There key findings in relation to pharmacotherapy were: (i) Antibiotic use was almost universal whereas antivirals were only prescribed in the context of clinical trials; (ii) PCT was commonly used in preference to CRP to guide antibiotic prescription in COVID-19 patients (iii) Rapid diagnostic PCR platforms to assess bacterial, and other viral co-infections were available in some centres (iii) Corticosteroids were commonly prescribed outside clinical trials, particularly methylprednisolone (23% of respondents). Among those who gave methylprednisolone, it was given at various time points of the disease process, early within 7 days (47%), between 7–14 days (38%), and >14 days by the rest at a dose of 1–2 mg/kg/day; (iv) Corticosteroids were given for mitigating inflammation, as an anti-fibrotic, and to treat bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia; (v) Augmented prophylactic anticoagulation was used routinely by 59% of respondents with 94% adopting this approach for some patients. Most survey responses (135 out of 137) were provided before the publication of the Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) study results, which demonstrated benefit from the use of dexamethasone and all responses predated the subsequent publication of the Randomised Embedded Multi-factorial, Adaptive platform trial for Community-Acquired pneumonia (REMAP-CAP) results in relation to Hydrocortisone use. 13 , 14 In comparison with the previous ARDS survey, there was increased use of corticosteroids for any reason including as part of a clinical trial (93% vs 70%) and routine use of neuromuscular agents (44.5% vs 15%). 10

Participation in clinical trials was extraordinary, with a substantial majority reporting enrolment into REMAP-CAP (82%). 14 This was much higher than our previous ARDS survey. Although routine follow-up after discharge took place in nearly two-thirds of units, less than one third offered any form of routine rehabilitation.

The limitations of the study include a low response rate which may in part be a consequence of the high clinical workload pertaining to the COVID-19 burden at the time that the study was conducted. Although responses were obtained from most of the Critical Care Networks across the UK, it was not inclusive of all hospitals within that Network. Moreover, there were multiple responses from individual hospitals. Consequently, we may have introduced non-responder and multiple responder bias affecting the integrity of the results and the generalisability and validity. Additional selection bias may have been introduced due to the electronic design of the survey. The questions regarding pharmacotherapies and the non-invasive ventilation, the answer domains were classified as “routinely”, “occasionally”, “individualised according to patient”, part of a clinical trial or “never”. To mitigate any confusions between the terms “occasionally” and “individualised according to patient”, we presented the data combining these two domains.

This manuscript summarises the experience of UK intensive care physician’s clinical management during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic based on the responses to a structured survey. Despite the rapid and substantial accumulation of knowledge from randomised controlled trials and large observational cohort studies around the world, unanswered research questions remain regarding many aspects of COVID-19 management in intensive care setting including: effectiveness of early use of CPAP/NIV in hypoxic patients, the timing of the transition from CPAP/NIV to invasive mechanical ventilation, the use of pharmacotherapies such as routine admission antibiotics, high dose corticosteroids, pulmonary vasodilators, augmented or therapeutic anticoagulation, antiplatelets, the utility of PCT to guide antibiotic prescription, as well as the most beneficial oxygen and fluid balance targets. Although it may not be feasible to answer all of these questions through clinical trials, this list emphasises the importance of recruiting patients into the established platform trials as well as the value of clear guidelines synthesising clinical experience and existing evidence to improve outcomes during this challenging and uncertain time.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-inc-10.1177_17511437211002352 for Intensive care physicians’ perceptions of the diagnosis & management of patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure associated with COVID-19: A UK based survey by A Dushianthan, AF Cumpstey, M Ferrari, W Thomas, SR Moonesinghe, C Summers, H Montgomery and MPW Grocott in Journal of the Intensive Care Society

Acknowledgements

We thank all the survey participants for their contribution. The study was conducted by NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre and University of Southampton. We thank The Intensive Society for advertising this survey on their newsletter. We also thank all the General Intensive Care unit consultants at University Hospital Southampton for their involvement in the internal pilot validation of the survey questionnaire.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: AC is funded is through the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre in Southampton as a clinical research fellow. MG holds an NIHR Senior Investigator award and is in part funded by the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre. The study was sponsored by the University Hospital Southampton R&D department. HM was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals. CS receives research funding from the Cambridge NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council and GlaxoSmithKline.

ORCID iDs: A Dushianthan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0165-3359

AF Cumpstey https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6257-207X

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.WHO Timeline - COVID-19, www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline–-covid-19 (accessed 8 May 2020).

- 2.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. Jama 2020; 323: 1545–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GOV.UK Coronavirus (COVID-19 in the UK), https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/healthcare (accessed 22 December 2020).

- 5.These data arise from the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. The case mix programme is the national clinical audit of patient outcomes from adult critical care coordinated by the Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC), www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports (accessed 22 December 2020).

- 6.National Guidance – ICM Anaesthesia COVID-19. Clinical guide for the management of critical care adults with COVID-19 during the coronavirus pandemic, https://icmanaesthesiacovid-19.org/clinical-guide-for-the-management-of-critical-care-for-adults-with-covid-19-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic. (accessed 28 October 2020).

- 7.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 1099–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts CM, Levi M, McKee M, et al. COVID-19: a complex multisystem disorder. Br J Anaesth 2020; 125: 238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doidge JC, Gould DW, Ferrando-Vivas P et al. Trends in Intensive Care for Patients with COVID-19 in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 203: 565--574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dushianthan A, Cusack R, Chee N, et al. Perceptions of diagnosis and management of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a survey of United Kingdom intensive care physicians. BMC Anesthesiol 2014; 14: 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.These data arise from the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database, CMP Participating Units, www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/About/Participation (accessed 14 September 2020).

- 12.These data arise from the Scottish Intensive Care Society Audit Group, SICSAG Participating Units, www.sicsag.scot.nhs.uk/About/Participants.html (accessed 14 September 2020).

- 13.Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 693--704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Writing Committee for the REMAP-CAP Investigators. Effect of hydrocortisone on mortality and organ support in patients with severe COVID-19: the REMAP-CAP COVID-19 corticosteroid domain randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324: 1317–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-inc-10.1177_17511437211002352 for Intensive care physicians’ perceptions of the diagnosis & management of patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure associated with COVID-19: A UK based survey by A Dushianthan, AF Cumpstey, M Ferrari, W Thomas, SR Moonesinghe, C Summers, H Montgomery and MPW Grocott in Journal of the Intensive Care Society