Abstract

Background and Objectives

Chest X-ray (CXR) is a non-invasive imaging modality used in the prognosis and management of chronic lung disorders like tuberculosis (TB), pneumonia, coronavirus disease (COVID-19), etc. The radiomic features associated with different disease manifestations assist in detection, localization, and grading the severity of infected lung regions. The majority of the existing computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) system used these features for the classification task, and only a few works have been dedicated to disease-localization and severity scoring. Moreover, the existing deep learning approaches use class activation map and Saliency map, which generate a rough localization. This study aims to generate a compact disease boundary, infection map, and grade the infection severity using proposed multistage superpixel classification-based disease localization and severity assessment framework.

Methods

: The proposed method uses a simple linear iterative clustering (SLIC) technique to subdivide the lung field into small superpixels. Initially, the different radiomic texture and proposed shape features are extracted and combined to train different benchmark classifiers in a multistage framework. Subsequently, the predicted class labels are used to generate an infection map, mark disease boundary, and grade the infection severity. The performance is evaluated using a publicly available Montgomery dataset and validated using Friedman average ranking and Holm and Nemenyi post-hoc procedures.

Results

: The proposed multistage classification approach achieved accuracy (ACC)= 95.52%, F-Measure (FM)= 95.48%, area under the curve (AUC)= 0.955 for Stage-I and ACC=85.35%, FM=85.20%, AUC=0.853 for Stage-II using calibration dataset and ACC = 93.41%, FM = 95.32%, AUC = 0.936 for Stage-I and ACC = 84.02%, FM = 71.01%, AUC = 0.795 for Stage-II using validation dataset. Also, the model has demonstrated the average Jaccard Index (JI) of 0.82 and Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) of 0.9589.

Conclusions

: The obtained classification results using calibration and validation dataset confirms the promising performance of the proposed framework. Also, the average JI shows promising potential to localize the disease, and better agreement between radiologist score and predicted severity score (r) confirms the robustness of the method. Finally, the statistical test justified the significance of the obtained results.

Keywords: Superpixels, Multi-Stage Classification, Disease Localization, Chest X-Ray, Severity Assessment

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Automation of healthcare facilities is one of the critical aspects of the current pandemic situation. Due to advancements in medical imaging modalities, the number of radiological examinations performed has substantially increased, which overburdened the radiologists and affects the overall quality of patient healthcare [1,2]. Further, the high morbidity and mortality rate due to various infectious lung diseases such as tuberculosis (TB) [3], pneumonia [4], COVID-19 [5], etc. demand a robust, end-to-end computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) system, which could assist in accurate diagnosis, localization, patient monitoring/triage, and streamlining the clinical communication and coordination between different healthcare departments [6].

In this context, thoracic imaging like computed tomography (CT) and chest radiograph images (X-ray) are frequently performed screening tests in clinical practices to investigate various lung infections [7,8]. In particular, chest radiography (or chest X-ray) uses a low radiation dose and is relatively cheaper, fast, and easily accessible. Moreover, it provides panoptic diagnostic information that supports subjective interpretation, severity assessment, and artificial intelligence-based disease detection and localization [9]. Also, it can be easily ported to a patient's bed in case of emergency and serve as an essential clinical adjunct to take instant therapeutic decisions [6]. However, due to 2D projection of X-ray beams and subtle radiographic responses of various diseases, a comprehensive visual evaluation of the infected area and volumetric involvement is challenging [10,11]. Also, the present radio-diagnosis procedure involves subjective interpretation of CXR films, which is a highly cognitive task, requires domain knowledge, and is biased due to inter-operator and intra-operator variability [5]. Therefore, an automated image analysis method that provides sufficient visual evidence (localize disease) to support classification results is of vital importance.

Different diseases exhibit different radiographic texture patterns in CXR image, as shown in Fig. 1 . The advanced machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms are sensitive to these textural responses and use it to segregate different lung abnormalities [2,7]. Further, the local neighborhood feature analysis helps identify the abnormality's spatial location and grade the severity [12], [13], [14]. In this direction, several automated CAD systems have been developed to detect different lung diseases using CXR images [3,5,11,[15], [16], [17]]. However, the majority of the CAD systems were mainly focused on disease classification and does not localize or grade the severity [5,17,18]. Recent studies addressed these issues using class activation map (CAM) of deep classification networks [13,19]. However, it generates a rough bounding box of the actual disease manifestation and fails to produce accurate boundary, making it unreliable and limiting its clinical applicability [20,21]. The reason being that the areas of the activated regions largely differ by channel, activated regions corresponding to the negative weights often cover large parts of the target object and the most activated regions of each channel largely overlap at small regions [22]. In some studies, a local patch-based approach is utilized. The intuition was that the features extracted from local patches can accurately represent the disease manifestations, which might be superseded if the global image features were used [12], [13], [14]. However, a recent approach using simple linear iterative clustering (SLIC) based superpixels gives a more compact representation of the local patch [23]. This method has been widely explored in the field of remote sensing [24], [25], [26] and could also be implemented to deal with complex medical image analysis tasks [27,28].

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray images showing radiographic texture patterns due to: (a-b) Tuberculosis, (c-d) Pneumonia, (e-f) COVID-19, (g-h) fibrosis.

In this study, we proposed superpixel-based disease localization and severity assessment framework. Initially, the input CXR image is used to extract superpixels from the lungs air region. Subsequently, generated superpixels are used to extract different geometrical shape and texture features, which can efficiently encode the different disease manifestations. Further, the encoded features are passed to a multistage classification framework that uses different benchmark supervised classifiers to segregate normal and abnormal superpixels. Finally, the predicted abnormal superpixels are remapped to the original image to generate the actual disease markings, infection map and predict the disease severity score. The significant advantage of the proposed approach is that it gives a more compact and eye-catching disease marking and severity score that could assist experts in subjective interpretation and triage the patient health care.

1.1. Contribution and outline of the Paper

-

-

We designed a superpixel classification based disease localization and severity assessment (DLSA) framework using CXR images.

-

-

Proposed a multistage classification framework to segregate normal vs. soft-tissues/bone density/bone overlap vs. diseased area on the CXR images. It leverages the advantages of adapted neighborhood image segments (or superpixel) to encode the spatial disease characteristics and classify them using support vector machine.

-

-

We formulated 47 radiomic features that encode the geometrical shape of superpixel. Further, the proposed radiomic features are used in combination with advanced texture features such as first-order statistical feature (FOSF), gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) features, and visual bag of words based SURF (speeded up robust features) feature.

-

-

Unlike the poor localization of CAM [6], we presented superpixel-based a robust method for generating a more compact infection map, disease marking, and severity score.

The rest of the paper is outlined as follows. Initially, Section 2 elaborates on the retrospective studies related to classification, localization, and severity assessment. Then, Section 3 describes the proposed approach and materials and methods used in this study. Finally, the experimental results and statistical validation are presented in Section 4, followed by a detailed discussion and a conclusion in Section 5 and Section 6, respectively.

2. Related Works

Identifying spatial locations of the abnormality play a vital role in adopting an appropriate curative plan. However, due to subtle radiographic responses of normal anatomy and disease manifestations, it is challenging to get the precise location of the infection [15]. To address this issue, Wang et al. [29] released a ChestX-ray-14 dataset comprising 112,120 CXR images of 14 distinct abnormalities. The author has applied weakly supervised CNN to produce a likelihood infection map and set up the base for future works and comparisons. However, the generated infection map has a low agreement with the ground truth bounding box. In Yao et al. [30], the author incorporated the conditional dependencies among the class labels and LSTM (Long short-term memory) method to improve the performance presented in [29]. Another similar work by Rajpurkar et al. [31] used 121-layer CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) architecture to create a finetuned CheXNet model, which outperformed the previous baseline approaches presented in [29,30]. However, the method shows rough localization and weak supervision in their work, which was addressed in [32]. Zhou et al. [32] utilized adaptive DenseNet that efficiently captured the disease manifestations and improved the localization accuracy by generating the disease bounding box. In Li et al. [33], the author has leveraged the class and annotation information to train the CNN model and extract the features from local patch grids to detect and localize abnormalities. The author in [34] proposed an novel approach for identification of secondary pulmonary tuberculosis using Pseudo Zernike moment feature extractor and deep stacked sparse autoencoder and achieved an accuracy of 93.23% ± 0.81% and F1 score of 93.23% ± 0.83%. Another work [35] presents rotation angle vector grid-based fractional Fourier entropy and deep stacked sparse autoencoder for accurate recognition of tuberculosis. The method achieved accuracy of 94.01±0.70% and F1-score of 88.07±1.38% outperforming the other benchmark methods. However, the DL approaches mentioned above demand extensive annotated data to train a generalized model [21]. Also, despite their promising detection performance, class activation map and saliency-map based disease localization generate a rough spatial location, which remains inaccurate compared to the actual disease marking.

Besides accurate diagnosis and spatial localization of the disease, severity scoring is another crucial component of any automated CAD system [14]. It helps track the disease progression, prioritize the scarce medical resources, and facilitate treatment planning in clinical practice [33]. Unfortunately, only a few relevant works have been reported in the literature related to severity scoring in CXR images [6,36,37]. Table 1 present a detailed description of the studies related to disease classification, localization, and severity scoring using CXR images. In particular, Candemir et al. [38] have investigated the performance of CNN architecture to grade the Cardiomegaly severity into borderline, mild, moderate, and severe class. In [37], the author has proposed a CNN-based COVID-19 infection grading mechanism that classifies the infection as mild, moderate, severe, and critical and achieved an accuracy of 95.52%. However, these methods do not quantify the infection inside the lungs. In this direction, Fridadar et al. [39] has used a residual network and activation map to generate a COVID-19 pneumonia score, which quantifies the infection severity. Degerli et al. [40] demonstrated an E-D CNN model for joint localization, severity grading, and detection of COVID-19 from CXR images. The model evaluated on a large compiled dataset and achieved a good localization accuracy of 83.20%. Although, the method is tested in relatively larger dataset (1,19,316 images), the infection localization performance still needs to be improved. The author in [41] has introduced transfer learning based COVID-Net CXR-S for predicting COVID-19 severity. However, the method does not provide any production ready solution. In [37] author has presented a novel variant of CNN model for grading the COVID-19 patients in four categories (i.e. mild, moderate, severe, and critical) and obtained an average accuracy of 95.52%. In study [42], author has presented an unified approach for lung segmentation, COVID-19 infection localization and severity quantification using U-Net, U-Net++ and a large benchmark CXR dataset. The reported results reveal the superior performance with dice coefficient of 97.99% (for lung segmentation) and 88.21% (for infection localization). However, this model is complex and need to be optimized. In study [43], author has addressed the issues related to vision transformer (ViT) architecture and proposed a Multi-task ViT approach, which uses low-level CXR feature corpus obtained from a backbone network for COVID-19 diagnosis and severity grading. The method used the saliency maps for diseases severity scoring and reported promising results using different cross-datasets. The author in [44] demonstrated a deep learning algorithm for COVID-19 severity scoring by quantifying the affected lung area in chest CT images (between 0-25). In addition, the deep learning algorithm's score is combined with RT-PCR, which improved the COVID-19 diagnostic accuracy (97.4% to 99.7%). However, the author has used Youden-index method for deciding the severity cutoff value, which changes with disease prevalence. Another study used the Brixia score to assign discrete values to different lung zones based on the extent of infection and generated a superpixel-based explainability map [6]. However, the method is biased to segmentation accuracy and radiologist expertise. Also, in some studies, lung CT images were used to score the severity and triage the patient healthcare [14,[45], [46], [47]]. However, the CT imaging modality uses high radiation dose, time taking, and costly; therefore, it is less preferably used.

Table 1.

Literature related to disease classification, localization, and severity assessment in chest X-ray images using various machine learning and deep-learning approaches.

(Abbreviations: IoP: Intersection over Prediction, GDA: Gaussian discriminant analysis, CAM: Class Activation Map, ACC: Accuracy, F1S: F1-Score, AUC: Area Under the Curve, Sen: Sensitivity, Spe: Specificity, COVID: Coronavirus Disease, DB: Database, DL: Deep Learning, FPN: Feature Pyramid Network, ResNet: Residual Network, RSNA: Radiological Society of North America, LSNet: Location-Sensitive Network, ISMIR: Italian Society of Medical and Interventional Radiology, CNN: Convolutional Neural Network, DC: Dice Coefficient, NIH: National Institutes of Health).

| References | Dataset Used | Technique Used |

Classification Performance | Localization Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease classification | Disease Localization | Severity Assessment | ||||

| Showkatian et al.[51] | Montgomery and Shenzhen dataset | ConvNet, Exception, Inception_V3, ResNet50, VGG16, VGG19 | - | - | For Exception ResNet50, and VGG16 ACC: 90.0 |

- |

| Rajaraman et al.[52] | TBX11K, Montgomery and Shenzhen dataset | Many deep learning models | U-Net based Saliency Maps, Grad-CAM | - | VGG-16-Fine-tuned ACC:92.31 |

VGG16 DC:0.5261 IoU:0.3743 |

| Puttagunta et al.[53] | TBX11K, JSRT, India, Belarus, Montgomery and Shenzhen dataset | Reviewed several methods | - | - | - | - |

| Degerli et al.[21] | QaTa‑COV19 | DeepNet-121, CheXNet Inception -v3, ResNet-50 |

Infection Map | - | ACC:99.73 F1S:95.67 |

ACC:99.85 F1S:83.20 |

| Wang et al.[2] | ChestX-ray14 | A 3 Net | element-wise attention in A 3 Net | - | AUC:82.60 | - |

| Zhang et al.[54] | COVID-19 Chest X-ray set, ChestX- ray14 | Deep-Learning using three Backbone Network | Grad-CAM | - | ACC:96.00 | - |

| Wang et al.[7] | COVID-19 DB | Discrimination-DL (ResNet-50+FPN) |

Localzation-DL | - | ACC:98.71 | ACC:93.03 |

| Fridadar et al.[39] | RSNA Pneumonia Detection, COVID-19 Image Data | ResNet-50 | LSNet-Aug | Pneumonia Ratio | ACC:0.94 | JI:0.86 DC:0.92 |

| Irmak et al.[37] | COVID-19 Image Data Collection, COVID-19 Radiography, ISMIR COVID-19 database, Twitter COVID-19 database, COVID-19 Image Repository, Novel Corona Virus2019 Dataset, COVID-19 Open Research Dataset |

- | - | CNN | - | ACC:95.52 AUC:0.98 |

| Tabik et al.[55] | COVID-19 Image Data Collection, RSNA, ChestX-ray8, MIMIC-CXR, PadChest dataset | - | - | COVID Smart Data based Network (COVID-SDNe) | - | Mild-ACC: 46.0 Moderate-ACC:85.38 Severe-ACC:97.72 |

| Minaee et al.[56] | COVID-Xray-5k Dataset | ResNet18, ResNet50, SqueezeNet, DenseNet-121 | - | - | Sen:98 Spe:≈90 |

- |

| Chandra et al.[12] | Montgomery dataset | - | Image patch-based clustering | - | - | ACC: 92.11 DC: 0.40 |

| Taghanaki et al.[57] | NIH ChestX-ray8 | Deep Learning | InfoMask | - | ACC: 82.48 AUC:82.51 |

IoP: 0.44 |

| Pesce et al.[9] | Private Dataset | Convolution networks with attention feedback, Recurrent attention model with annotation feedback |

Convolution networks with attention feedback | - | Lesion vs. Normal ACC: 85.0 Lesion vs. All Others ACC: 76.0 |

Lesion vs. Normal Avg Overlap: 74.0 Lesion vs. All Others Avg Overlap: 43.0 |

| Pasa et al.[58] | Montgomery (MC), Shenzhen (SZ) and Combined (CB) dataset |

CNN | Saliency Maps, Grad-CAM | - | MC-ACC:79 SZ-ACC:84.4 CB-ACC:86.2 |

- |

| Islam et al.[59] | Montgomery and Shenzhen dataset | CNN based U-Net | - | - | Segmentation Performance DC:0.986 | - |

Recently, the superpixel based disease classification and segmentation has gained significant attention [6,48,49]. Ortiz-Toro et al. [48] has compared the performance of three textural feature (radiomics, fractal dimension and superpixel-based histón) using different conventional machine learning techniques. Author reported that the superpixel based feature extraction approach achieved better performance for both training testing set and for validation set. In study [49], author has proposed COVID-19 Super pixel SqueezNet model using superpixel of network activation map to perform binary and multi-class classification. The proposed system obtained approx. 99% classification accuracy promising localization accuracy (dice coefficient of 0.92 for ground glass opacities, 0.85 for consolidations, and 0.87 for hazy patches). However, the author has not performed severity analysis and the applied superpixel segmentation utilized constant vertical and horizontal window size (that affect the discriminating potential of extracted features). Another similar work [50] presented transfer learning based COVID-19 detection and infection segmentation model using CXR images. The method achieved 99.69% and 99.48% classification accuracy for binary and three class classification; whereas 83.43% accuracy for segmentation. However, the method has extracted superpixels from CAM and not directly from the CXR images and thus the accuracy of superpixel method is dependent on CAM.

Remark. As discussed in the aforementioned literature that the disease localization and severity scoring techniques have a significant enhancement scope. However, most of the existing works are based on activation map or saliency map, which generate rough localization and thus affect the severity scoring. Also, most of the existing superpixel based approaches use superpixel extracted from network activation map, which limits its performance. Therefore, this study proposed a conventional machine learning based superpixel multistage classification frameworks that examines each superpixel and yields a more compact infection map, smooth disease marking, and severity score. The next section elaborates on the materials and methods used in this study.

3. Materials and Methods

This section presents a detailed technical description of the following components: dataset, superpixel-level augmentation, multistage superpixel classification using texture, shape, and visual bag of words (VBoW) features, disease spatial localization, and severity scoring.

3.1. Dataset

Training-testing and validation of the proposed method are achieved using CXR images from the publicly available Montgomery dataset [60,61]. This dataset is acquired from the TB Control Program of the Department of Health and Human Services of Montgomery County, MD, USA. It comprises of 138 deidentified posterior-anterior (PA) CXR images in which 58 images are taken from patients infected with TB. The images are captured in grayscale mode with a pixel density of 72 dots per inch (DPI), bit depth of 12-bit, image resolution of 4020×4892 or 4892×4020 and are made available for public use in Portable Network Graphics (PNG) file format. The dataset also includes left and right PA-view binary lung mask and consensus annotations from two radiologists. The primary motivation behind selecting this dataset is that it includes a gold standard lung segmentation mask, which helps us assess the actual performance of the proposed method. Besides, the limited training data enables us to evaluate the efficacy of the proposed method in a limited training environment. All the experiments in this study are evaluated using two sub-sets of the dataset—calibration set (80%) and validation set (20%). The superpixels extracted from the calibration set are used train the supervised models in 10-fold cross-validation setup; while the superpixels extracted from validation set are used to validate the trained models on completely new samples, which were not used at the time of training.

Further, to generate ground truth (GT) disease marking, we asked two expert radiologists from Pt. Jawahar Lal Nehru Memorial Medical College, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. The first radiologist is having 20 years of work experience as a consultant radiologist and is currently working as a professor and head in the department of radiodiagnosis. The second radiologist is having 6 years of work experience as a consultant radiologist and is currently working as an associate professor in the department of radiodiagnosis. The experts are provided with the original CXR image, segmented lung fields (obtained using GT mask), and a small software tool based on MATLAB® to mark the abnormal area. Finally, the disease marking (binary mask) obtained from two expert radiologists is aggregated using a union operator to get the final disease marking (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

(a) Original CXR image, (b) Segmented lung field, (c) Disease marking by Radiologist-1, (d) Disease marking by Radiologist-2, (e) Aggregated disease marking.

3.2. Proposed Methodology

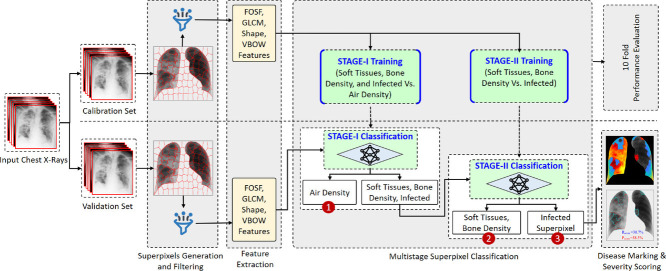

The proposed disease localization and severity assessment (DLSA) framework (shown in Fig. 3 ) employs multistage superpixel classification (MsSpC) using extracted geometrical shape and advanced texture features. The proposed framework is grounded on the following hypothesis:

Fig. 3.

Propose methodological diagram for Superpixel-based multistage classification for disease localization and severity assessment framework.

Hypothesis 1

We hypothesized that instead of subdividing the lung parenchyma using square-shaped dense-grid patches, a more compact representation using SLIC based superpixel method would significantly improve the localization performance.

Hypothesis 2

The comparative more geometrical irregularities in the shape of superpixels near the abnormal area (shown in Fig. 4 (a)) can be encoded using radiomic shape features and contribute to identifying infected superpixels.

Fig. 4.

(a) CXR image showing superpixel image segments (k = 150, c = 1), (b) Superpixels that are very small in size.

Hypothesis 3

The strong mathematical background and elegant data transformation ability using kernel-trick functions give support vector machine (SVM) a better inductive reasoning capability [5]. It would help to learn the non-linear features from subtle disease responses and produce a better generalized model.

Hypothesis 4

Unlike Grad-CAM and saliency maps that generate a rough localization [6], we hypothesized that the proposed superpixel-based infection map would produce a smooth and compact disease marking and help to grade the severity accurately.

Hypothesis 5

The subjective interpretation based severity assessment suffers from inter-observer and intra-observer variability [62]. Further, instead of grading the infection level as severe, moderate, or mild (as in the case of subjective assessment), assigning a quantitative score based on the disease progression would help triage patient health care and fair allocation of scares medical resources, specifically in pandemic situations.

The aforementioned hypothetical assumptions are evaluated using the proposed MsSpC-DLSA framework, as shown in Fig. 3. The proposed model operates in two modes: model calibration (offline) and model validation (online). In offline mode, different supervised models are trained using training data (calibration dataset) to build a generalized model. Whereas in the online mode, the fully trained models are employed to classify the input images from the validation dataset (which were not used in the training phase). Subsequently, the different performance metrics are computed. The primary steps involved in training and testing the proposed framework include: pre-processing, superpixel generation and patch level augmentation, shape and texture feature extraction, multistage supervised classification, disease spatial-localization, and severity scoring. In pre-processing, the input CXR images are segmented to extract the region of interest (RoI). To achieve this, we have used nonrigid registration of anatomical atlas based robust lung segmentation method proposed in [60]. The rationale behind the choice of this method is the significantly higher degree of agreement between the segmented lung boundary and GT markings given by the radiologist. Subsequently, to evaluate Hypothesis 1, the segmented lung parenchyma is subdivided into different lung regions using SLIC based superpixel approach (described in Section 3.3). From the obtained superpixels, it was observed that the number of non-infected superpixels was significantly greater than the number of infected superpixels. This imbalanced data substantially affects the overall performance and is a hindrance to producing a stable model. To confront this issue, the superpixel augmentation approach is used (described in Section 3.3). Further, to examine Hypothesis 2, forty-seven radiomic shape features are formulated. These shape features can efficiently encode the geometrical irregularities in the shape of infected superpixels. Moreover, to encode various disease radiographic texture responses, different texture features (described in Section 3.4) are extracted. The extracted shape and texture features are combined and used to train the different benchmark supervised classifiers (Hypothesis 3). Subsequently, the different superpixels classified as infected are used to generate an infection map and a smooth disease marking that more accurately adheres with the disease boundary (Hypothesis 4). Finally, the percentage infection score is computed by counting the infected pixels from the complete lung area (Hypothesis 4). All the experimentations in this study are performed in MATLAB R2020a1 using a 64-bit laptop (2.9 GHz, AMD Ryzen-7 octa-core CPU, 4 GB NVIDIA graphic card, and 24 GB of RAM). The following sub-sections elaborate on the different steps involved in this study.

3.3. Superpixel Generation and Augmentation

Disease infection in the CXR image exhibits cloudy patches, which is significantly different from the normal anatomy (shown in Fig. 1). Statistical analysis of these disease responses depicts the irregular shape and different texture patterns. In particular, superpixel image segments constitute pixels with spectral similarity and spatial proximity to generate a compact representation of irregular visual scenes [25]. Moreover, disease interpretation using the subdivided lung fields has demonstrated substantial prognostic value [63,64]. Therefore, in this study, the SLIC algorithm [23] is used to generate superpixels, as shown in Fig. 4 (a).

The given input CXR image ‘I’ is subdivided into a set of ‘k’ superpixels si such that I = {si}, ∀ i = 1, 2, 3…k; where i is the superpixel index. To control the number and compactness of superpixel, two parameters ‘k’ and ‘c’ are used, respectively. The value of ‘k’ is empirically chosen as discussed in Section 4. Whereas the lower value of compactness ‘c = 1’ is selected, which makes superpixel adhere to the boundaries better.

The extracted superpixels show that many superpixels are significantly small and do not contain much discriminative information, as shown in Fig. 4 (b). These non-informative superpixels are filtered out using Eq.1. Here, the information threshold ‘t’ is empirically selected to be 10%;

| (1) |

Where, P non zero = Non zero pixels in superpixels

Pall = Total number of pixels in superpixels

t = denotes the information threshold

Further, to train a generalized model, a balanced dataset plays an important role [65]. However, in this study, it was observed that the number of non-infected superpixels is significantly greater than the number of infected superpixels. Therefore, to balance the data, superpixel augmentation technique is performed. The method applies various random photometric transformations like sharpening, Gaussian blur (0.1 to 1.5), brightness (-10 to 10), contrast, and rotations (-10 to 10 degrees). The Table 11 (in Appendix) presents the actual number of superpixels extracted from the input image and the number of augmented superpixels for calibration set (stage-I and Stage-II).

3.4. Feature Extraction

The superpixels infected due to different abnormalities exhibit unusual radiographic texture patterns compared to the non-infected regions (shown in Fig. 1). These patterns need to be encoded in a suitable form to make them comparable. In this study, we used three robust texture descriptors—first-order statistical feature (FOSF) [5], gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) [5,66] feature and bag of visual words (BoVW) based SURF (speeded up robust features) feature [11,67]. The FOSF represent basic image features energy, entropy, smoothness, kurtosis, roughness, mean and variance, etc. However, it does not encode the local neighborhood pixel correlation. The GLCM feature establishes the spatial correlation among the neighborhood pixel intensities in different orientations ‘θ’ and distance ‘d’. However, both the features (FOSF and GLCM) are not scale and rotation invariant. Therefore, BoVW based SURF descriptor is used (vocabulary size: 500, point selection: Grid, grid step: 8×8). It achieves scale invariance by representing the image in pyramid and computing the difference of gaussian image; whereas, the rotation invariance is achieved by computing Haar Wavelet responses in x and y direction. The selection of the aforementioned texture descriptors are based on their efficacy to encode disease texture patterns in medical image analysis task [3,5,27,68].

Besides the texture features, geometrical analysis of the superpixel shape may contribute to the identification of infected superpixels. It can be observed from Fig. 4 (a) that the superpixels near the abnormal lung regions exhibit more geometrical irregularities compared to the normal regions. In Hypothesis-2, it is speculated that these irregular shape patterns can be efficiently encoded with the help of low-level shape features. Therefore, we formulated 47 derived geometrical shape features.

For the extracted set of superpixel patches Si = {s 1, s 2,……sk} ∀ SiεDn, where k is the number of superpixel in each image ‘i’ and ‘n’ is the number of images in dataset D, we compute the following shape features. It is important to note that the some of the shape features are calculated using “regionprops” function of the MATLAB 20202 .

-

•Edge Count (Ec): An edge represents the significant local changes in the intensity of the image. It can be computed by discrete approximation of gradients in vertical (gx) and horizontal (gy) direction, as described in Eq.2. Further, the edge direction can be computed using .

(2)

-

•Corner Count (Cc): Corner is the point of intersection of two gradients in different directions. It is invariant to rotation, illumination, and translation. The corner point is identified by computing variation in intensity for (Δx, Δy) displacement in all directions as described in Eq.3. Where, w(x, y) is the window function and I(x + Δx, y + Δy) is the shift intensity. The Cc feature returns a scalar value, which can elegantly encode the corners created by the irregular boundaries of infected superpixels, as shown in Fig. 5 (Row-3).

(3) -

•Radial Distance (Rd): The Rd metric measures the Euclidean distance from the centroid to a point on the periphery of the superpixel at an angle θ (described in Eq.4). It helps to quantify the variations in structure and curvature of the boundary, which presents essential information about the shape of the superpixel. In this study, we used inclination angle θ = 10°, therefore extracted a total of 36 radial distance features as shown in Fig. 5 (Row-4).

(4)

Fig. 5.

Superpixel patches showing—Row-1: Input normal and infected superpixels, Row-2: Canny edges and edge count, Row-3: Corner count and locations, Row-4: Superpixel centroid and radial distances, Row-5: Superpixel perimeter, major axis length, minor axis length, and orientation, Row-6: convex hull marking and superpixel convexity.

where, n = 0, 1, …N − 1 is obtained by tracing all pixels on the boundary

-

•

Major Axis Length (ALmajor): It is the length of the line segment connecting two farthest points on the periphery of the ellipse (as shown in Fig. 5 (Row-5)), where the normalized second central moments (NSCM) of the ellipse is equal to that of superpixel. It is rotation and illumination invariant and returns a scalar value.

-

•

Minor Axis Length (ALminor): It is the length of the line segment connecting two nearest points on the periphery of the ellipse (as shown in Fig. 5 (Row-5)), where the NSCM of the ellipse is equal to that of the superpixel. It is rotation and illumination invariant and returns a scalar value.

-

•

Eccentricity (E): It measures the aspect ratio of the superpixel by computing the ratio of the distance from the center to a focus (c) and distance from that focus to a vertex (a) as described in Eq.4. It returns a scalar value that describes how the shape of a superpixel varies from that of the circle. The E for rounded superpixel tends to 0, while, for squeezed superpixel, it tends to 1.

-

•

(5)

-

•

Orientation (O): It represents the angular direction of the superpixel. It is computed by measuring the angle between the x-axis and the ellipse's major axis, which has the same NSCM as the superpixel. Its value varies between − 90° to 90°.

-

•

Perimeter (p): It returns a sum of the scalar distance of each adjacent pair of pixels on the boundary of the superpixel. The perimeter of irregular shapes usually tends to be larger than the perimeter of the regularly shaped superpixels of the same size. It is rotation and illumination invariant.

-

•Solidity (S): It returns a rotation, illumination, and scale-invariant scalar value that denotes the degree to which the superpixel is concave or convex. It is measured by computing the ratio of area of superpixel (Asp) to the convex hull (Chull) as described in Eq.5. By definition, the S of convex superpixel is always 1.

(6) -

•Extent (Ext): This metric measures the ratio of the pixels in the superpixel region to pixels in the superpixel bounding box as described in Eq.6. It returns a rotation, illumination, and scale-invariant scalar quantity.

(7) -

•Circularity Ratio (Cratio): This metric measures the perimeter roughness or how the shape of a superpixel is similar to a circle. It is computed as the ratio of area of superpixel (Asp) to the squared perimeter (p 2) as described in Eq.7.

(8) -

•Convexity (Con): It returns a scalar quantity by measuring the ratio of the perimeter of convex hull to the perimeter of the superpixel as described in Eq.8.

(9)

The brief summary about the dimension of various texture and shape features extracted are shown in Table 12 (in the Appendix).

3.5. Multistage Superpixel Classification

In this section, we elaborate on the proposed multistage superpixel classification approach. Initially, the Binary Grey Wolf Optimization (BGWO) [69] metaheuristic technique is applied to select the strongest features from the combined shape and texture feature. Subsequently, for classification, seven supervised benchmark classification algorithms—SVM (Linear and Cubic kernel) [70,71], Ensemble (Boosted tree) [72], K Nearest Neighbor (KNN) [73], Naive Bayes [74], Logistic Regression [75], and Decision Tree [76] are used. The training and validation of the proposed system are achieved in two stages. In Stage-I, the supervised models are trained to segregate the superpixels containing air density (class-A) vs. superpixels containing soft tissue, bone density, and disease infection (class-B). Similarly, in Stage-II—infected superpixel vs. superpixels containing soft tissue and bone density are used to train the models. Further, the trained models are employed to classify the superpixels in class-A and class-B (in Stage-I) and all the superpixels that are assigned to class-B (in stage-I) are classified to infected superpixel vs. superpixels containing soft tissue and bone density in stage-II (shown in Fig. 3). All the supervised algorithms used in this study are trained using 10-fold cross-validation setup and the hyperparameters are automatically optimized using Bayesian optimization technique [77].

Further, the choice of the classification algorithms is inspired by the fact that these algorithms can be expeditiously trained the models using limited training data without much impairing the performance. Moreover, they are pervasively used in literature to classify the medical images, which motivated us to use them in our study [5,62,78].

3.6. Disease Spatial-Localization

Once the abnormal superpixels are identified, the corresponding binary masks are merged using the union operator as described in Eq.10 to create the infection mask. This infection mask is remapped on the input CXR image to create a compact and smooth disease boundary (Fig. 11).

| (10) |

Where, ‘i’ is the index of the infected superpixel

Fig. 11.

Chest X-ray images showing Ground Truth disease marking (Red), predicted abnormal area (Cyan), Radiologist Severity Score (Rscore) and Predicted Severity Score (Pscore).

Subsequently, an infection map is generated by overlaying the heatmap images for infected superpixels and soft-tissue regions on the input CXR image, as shown in Fig. 9. Finally, the Dice similarity coefficient between predicted disease marking and GT is measured to evaluate the localization performance.

Fig. 9.

Infection map images showing: RED— predicted abnormal area, Blue— predicted soft tissues, bone density and bone overlap, Grayscale— predicted normal area.

3.7. Infection Severity Scoring

Besides, disease localization, severity scoring play an important role in treatment planning, prioritizing patient healthcare services, and scarce medical resources [28]. In this study, we used the ratio of infected lung area (Ainfection) to the total lung area (Alung) to quantify the severity of lung infection as described in Eq.11. Further, the predicted infection score could be used for prioritizing the treatment and allocation of scarce medical resources, specifically in the situations like a pandemic.

| (11) |

Finally, the predicted infection score is compared with the radiologist score (Rscore) to assess the performance.

3.8. Performance Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of the proposed approach, eight performance metrics—accuracy (ACC), specificity, precision, recall, F1-Measure, area under the curve (AUC), Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), Jaccard Similarity Index, and Dice Similarity Coefficient are used [73]. These metrics are described in Eq. 12 to Eq. 20. Where the true positive (STP) and true negative (STN) represents the number of superpixels correctly identified by the proposed system; whereas false positive (SFP) and false-negative (SFN) denotes the false prediction; SP = STP + SFN and SN = STN + SFP.

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

Further, to evaluate the statistical significance of the obtained results, an average ranking-based non-parametric Friedman's test [62,79] is used. It performs multiple tests using given sets of data to find any significant variance in the performance of algorithms. Moreover, Holm [80] and Nemenyi [81] post-hoc N × N multiple comparision procedures is used to find the pair of algorithms in which the significant difference exist.

4. Experimental Results

This section elaborates on the obtained experimental results of the proposed multistage superpixel classification-based disease localization and severity assessment (MsSpC-DLSA) framework (shown in Fig. 3). The detailed implementation of the proposed framework is described in Section 3.2. Further, to evaluate the validity of hypothesized assumptions (discussed in Section 3.2), we articulated different experiments and discussed them in detail.

Initially, in the first experiment, we subdivided the segmented lung fields into different superpixels using the SLIC algorithm (discussed in Section 3.3). To select the optimal number of superpixel (‘k’) that can accurately adhere to the disease boundary, the classification performance of different benchmark classifiers using different number of superpixel (k = 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300) is investigated as shown in Fig. 6 (Tabular data is shown in Appendix: Table 8). From the figure, it was observed that the different classifiers achieved significantly better classification performance for k = 150. The achieved higher classification performance is due to the fact that the generated superpixel is neither too small (as in the case of k > 150) that discards the important information nor too large (as in case of k < 150) to include the unwanted features from neighboring regions. Based on the observed results, all the subsequent training and validations of the supervised models used in the proposed study are performed using superpixel generated with the value of ‘k = 150’.

Fig. 6.

Superpixel classification performance for the different numbers of superpixels (50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300) using a 10-fold cross-validation setup. (Tabular data is shown in Appendix: Table 8).

Subsequently, the second experiment was designed to examine the assumptions that the superpixel shape feature may contribute to identifying infected superpixels (Hypothesis 2). To achieve this, the texture features (FOSF, GLCM, and BoVW) are used to train the supervised models. From the obtained results shown in Appendix: Table 9, it was observed that the texture feature, when used in isolation, achieved limited diagnostic performance due to subtle radiographic appearance of disease manifestations with normal anatomical structures. Moreover, to adopt the radiologist's diagnostic procedure (first examine the shape deformations followed by analysis of disease texture patterns) as presented in [3], we articulated 47 geometrical shape features. Further, the extracted shape and texture features are combined and utilized to train the models (10-fold). The comparison of the obtained results (classifier's performance) using texture features vs. texture+shape features is shown in Fig. 7 . From the figure, one can observe that the combined features achieved better classification performance than isolated texture descriptors, which justified the validity of Hypothesis 2. The enhanced performance by using integrated features is due to the fact that the proposed shape features can efficiently encode the irregularities in the shape of infected superpixels (shown in Fig. 5 (Row-1)). In contrast, the texture feature quantifies the disease texture patterns.

Fig. 7.

Radar chart showing accuracy (ACC) comparison of different classifiers using texture features vs. texture+shape features using calibration set for (a) Stage-I and (b) Stage-II. (Tabular data is shown in Appendix: Table 9)

In the third experiment, performance of the proposed MsSpC-DLSA framework was assessed using different supervised algorithms in two stages, as described in Section 3.5. The combined features are passed to different benchmark classifiers, and their performance is evaluated in 10-fold environment using calibration and validation dataset. The obtained results are shown in Table 2 (for calibration set) and Table 3 (for validation set). It is observed from Table 2 that the SVM classifier with cubic kernel trick function outperformed the others with ACC=95.52%, FM=95.48%, AUC=0.955 for Stage-I, and ACC=85.35%, FM=85.20%, AUC=0.853 for Stage-II. Similarly, it also achieved higher classification performance (ACC=93.41%, FM=95.32%, AUC=0.936 for Stage-I and ACC=84.02%, FM=71.01%, AUC=0.795 for Stage-II) using validation dataset as shown in Table 3. The outstanding performance of SVM (cubic kernel) classifier can be justified with the fact that the strong mathematical foundation and ability to transform data in higher feature space using kernel trick function helps to find optimal support-vectors that can accurately separate the non-linear data. Moreover, the elegant inductive reasoning ability help to learn the non-linear features and produce a generalized model. The achieved higher performance of SVM (cubic kernel) justify the validity of hypothetical assumption presented in Hypothesis 3.

Table 2.

Superpixel classification performance in Stage-I and Stage-II using FOSF+GLCM+ Shape+BoVW features on Calibration set (10-fold cross-validation setup).

(Abbreviations: SVM=Support Vector Machine, KNN=k-Nearest Neighbour, AUC=Area Under Curve, MCC=Matthews Correlation Coefficient).

| Classification Algorithm | Accuracy | Specificity | Precision | Recall | F-Measure | AUC | MCC |

| STAGE-I | |||||||

| SVM (Linear) | 94.868 | 96.481 | 96.364 | 93.255 | 94.784 | 0.949 | 0.898 |

| SVM (Cubic) | 95.517 | 96.313 | 96.254 | 94.721 | 95.481 | 0.955 | 0.910 |

| Ensemble (Boosted Tree) | 94.973 | 96.230 | 96.132 | 93.716 | 94.909 | 0.950 | 0.900 |

| KNN | 90.155 | 93.506 | 93.040 | 86.804 | 89.814 | 0.902 | 0.805 |

| Naive Bayes | 91.705 | 94.721 | 94.383 | 88.689 | 91.447 | 0.917 | 0.836 |

| Logistic Regression | 93.527 | 95.685 | 95.490 | 91.370 | 93.385 | 0.935 | 0.871 |

| Decision Tree | 93.444 | 93.967 | 93.903 | 92.920 | 93.409 | 0.934 | 0.869 |

| STAGE-II | |||||||

| SVM (Linear) | 82.218 | 84.758 | 83.943 | 79.678 | 81.755 | 0.822 | 0.645 |

| SVM (Cubic) | 85.347 | 86.307 | 86.039 | 84.387 | 85.205 | 0.853 | 0.707 |

| Ensemble (Boosted Tree) | 82.032 | 87.918 | 86.306 | 76.146 | 80.908 | 0.820 | 0.645 |

| KNN | 79.802 | 80.112 | 79.988 | 79.492 | 79.739 | 0.798 | 0.596 |

| Naive Bayes | 71.964 | 69.641 | 70.989 | 74.287 | 72.601 | 0.720 | 0.440 |

| Logistic Regression | 75.496 | 80.173 | 78.127 | 70.818 | 74.293 | 0.755 | 0.512 |

| Decision Tree | 75.031 | 90.211 | 85.943 | 59.851 | 70.562 | 0.750 | 0.525 |

Table 3.

Superpixel classification performance in Stage-I and Stage-II using FOSF+GLCM+ Shape+BoVW features on Validation dataset.

(Abbreviations: SVM=Support Vector Machine, KNN=k-Nearest Neighbour, AUC=Area Under Curve, MCC=Matthews Correlation Coefficient).

| Classification Algorithm | Accuracy | Specificity | Precision | Recall | F-Measure | AUC | MCC |

| STAGE-I | |||||||

| SVM (Linear) | 91.731 | 91.244 | 96.422 | 91.921 | 94.118 | 0.916 | 0.805 |

| SVM (Cubic) | 93.411 | 94.009 | 97.556 | 93.178 | 95.317 | 0.936 | 0.845 |

| Ensemble (Boosted Tree) | 91.990 | 91.244 | 96.435 | 92.280 | 94.312 | 0.918 | 0.810 |

| KNN | 84.884 | 92.627 | 96.610 | 81.867 | 88.630 | 0.872 | 0.686 |

| Naive Bayes | 87.984 | 90.783 | 96.032 | 86.894 | 91.235 | 0.888 | 0.732 |

| Logistic Regression | 87.209 | 94.470 | 97.510 | 84.381 | 90.472 | 0.894 | 0.731 |

| Decision Tree | 91.214 | 91.244 | 96.395 | 91.203 | 93.727 | 0.912 | 0.794 |

| STAGE-II | |||||||

| SVM (Linear) | 75.224 | 81.454 | 55.952 | 59.494 | 57.669 | 0.705 | 0.402 |

| SVM (Cubic) | 84.022 | 89.975 | 73.154 | 68.987 | 71.010 | 0.795 | 0.600 |

| Ensemble (Boosted Tree) | 76.840 | 86.466 | 60.584 | 52.532 | 56.271 | 0.695 | 0.408 |

| KNN | 68.402 | 74.436 | 45.161 | 53.165 | 48.837 | 0.638 | 0.264 |

| Naive Bayes | 66.248 | 66.165 | 43.750 | 66.456 | 52.764 | 0.663 | 0.297 |

| Logistic Regression | 70.018 | 79.198 | 47.134 | 46.835 | 46.984 | 0.630 | 0.261 |

| Decision Tree | 72.890 | 90.226 | 54.118 | 29.114 | 37.860 | 0.597 | 0.242 |

The Sankey flow diagram shown in Fig. 8 shows the flow of data (input superpixels) to different class labels (predicted) in SVM (Cubic kernel) classifier. Here, the width of flow lines represents the volume of data flow. The narrow flow line from ‘Air Density’ class to ‘ISp/BD/ST’ (Infected Suppixel/ Bone Density/Soft-tissues) and vice-versa shown in Fig. 8(a) for calibration set, and Fig. 8(c) for validation set denotes the better performance (or low misclassification); whereas, the comparatively wide flow line from ‘BD/ST’ class to ‘ISp’ and vice-versa shown in Fig. 8(b) and Fig. 8(d) represent substantial misclassification of the superpixels, which can also be observed from lower performance in Stage-II from Table 2 (ACC=85.35%) and Table 3 (ACC=84.02%). The relatively lower performance in Stage-II of the proposed framework is due to the fact that the infected superpixel exhibits a subtle radiographic appearance with superpixels containing bone density, bone overlap and soft tissues (as shown in Fig. 14(a-d) of the Appendix), which limits the discriminating performance of the texture features.

Fig. 8.

Performance visualization using Sankey flow diagram for SVM (Cubic kernel) classification at (a) STAGE-I using Calibration dataset., (b) STAGE-II using Calibration dataset, (c) STAGE-I using Validation dataset., (d) STAGE-II using Validation dataset.

(Abbreviations: ISp=Infected Suppixel, BD=Bone Density, ST=Soft-tissues)

Fig. 14.

Radiographic texture patterns in superpixels of (a) Abnormal region, (b) Bone density, (c) Bone overlap, (d) Soft tissue.

The fourth experiment was designed to evaluate the disease localization performance using the proposed superpixel approach (discussed in Hypothesis 4). First, the identified infected superpixel are merged to create an infection mask, and the superpixels classified as soft-tissue or bone density class are used to generate a soft-tissue mask. Subsequently, the obtained masks are utilized to create an infection map by overlaying the heatmap image on the CXR image, as shown in Fig. 9 . From the subjective assessment of the obtained infection map, it can be observed that, unlike Grad-CAM and saliency maps, the proposed superpixel approach produce a smooth and compact infection map, which validates Hypothesis 4.

Further, the quantitative assessment of disease localization performance was achieved by computing the Jaccard index (JI) and Dice similarity coefficient (DC) metrics, and the results are shown in Fig. 10 (a) and Fig. 10 (b), respectively. Both the metrics measure the degree of overlap between predicted disease marking and GT marking (by an expert radiologist). From the box plot shown in Fig. 10 (a,b), it is observed that the SVM classifier using cubic kernel outperformed the other by achieving the highest average JI of 0.82 and average DC of 0.77. We also compared this result with our previous experiment [12] that used square-shaped dense-grid patches and unsupervised clustering algorithms to localize the infected region. The comparative analysis reveals that the proposed superpixel-based localization approach generates more compact disease marking and achieved significantly higher average JD and DC, which justifies the validity of Hypothesis-1.

Fig. 10.

Box plot showing average (a) Jaccard Similarity Index and (b) Dice Similarity Coefficient between Ground Truth disease marking (by radiologist) and predicted abnormal area using validation set (STAGE-II, 150 superpixels). (Tabular data is shown in Appendix: Table 10).

(Abbreviations: SVM=Support Vector Machine, KNN=k-Nearest Neighbour, NB=Naive Bayes, LR=Logistic Regression, DT=Decision Tree)

The retrospective study of the literature reveals that the subjective assessment of CXR image is a highly cognitive task and may suffer from inter-observer and intra-observer variability [28,45,62]. Moreover, grading the severity as severe, moderate, or mild based on subjective assessment may not serve the purpose specifically in the situations like pandemics. Therefore, in the fifth experiment, we assigned a severity score (as discussed in Section 3.7) to each CXR image based on disease progression, as shown in Fig. 11 . The score represents the area (in percent) of lung infected by the disease inflammation, which can prioritize the patient's treatment and allocation of scarce medical resources. Further, we compared the predicted severity score (obtained from the proposed system) with the radiologist score (computed using the GT disease marking) using Pearson's correlation plot shown in Fig. 12 . From the figure, it is that the predicted score is positively correlated with the radiologist score, which can also be verified from the correlation coefficient r = 0.9589. Here, the value of ‘r’ varies from -1 to 0 to +1 for negative correlation, no correlation, and positive correlation, respectively. The obtained high positive correlation between predicted and radiologist scores justified the validity of Hypothesis 5.

Fig. 12.

Pearson's correlation plot between Predicted severity score and Radiologist severity score (the observed value of correlation coefficient r = 0.9589).

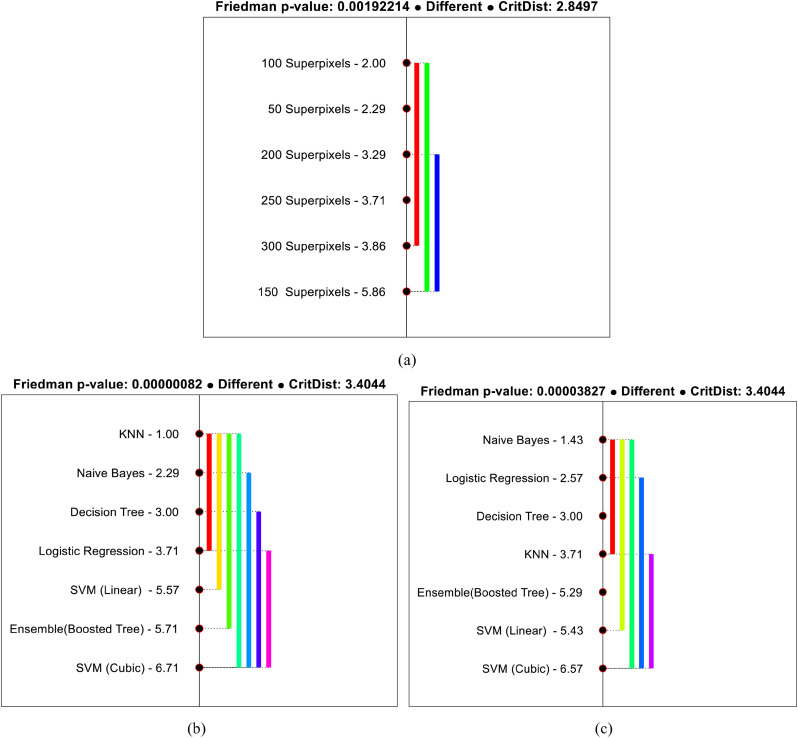

4.1. Statistical Analysis

This section aims to demonstrate the statistical significance of the obtained results using Friedman average ranking [79] and Holm [80] and Nemenyi [81] based post-hoc pairwise multiple comparison methods. Initially, the Friedman statistical test is used to rank the classification performances using different number of superpixel setups. The test assumes the null hypothesis that the classification performance using different number of superpixel setup are equal. From the test results shown in Table 4 (a), it is observed that the test rejects the null hypothesis while accepting the alternate at 5 degrees of freedom and significance level α = 0.05, which reveals the substantial difference in the performance of different superpixel setup. Besides, the superpixel setup with a value of k = 150 achieved a minimum average rank, which shows the statistical significance of the results presented in Fig. 6. The results can also be validated from the computed Friedman p − value = 0.001923 < α. Similarly, the average ranks of different benchmark classifiers in Stage-I and Stage-II are also evaluated to test any significant difference in the performance of different classifiers. From the obtained results shown in Table 4 (b), it is found that the performance of different classifiers are significantly different (accepting alternate hypothesis) in both the stages, which can be verified from Friedman p − value = 0.0000008218 < α (for Stage-I) and p − value = 0.000038269 < α (for Stage-II). Further, the lowest mean rank for SVM (cubic kernel) in Stage-I and Stage-II demonstrates the statistical significance of the obtained result shown in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 4.

Friedman average ranks of (a) Classification performances based on different number of superpixel setups (with 5 degrees of freedom). (b) Various classification algorithms based on classification performance metrics for disease localization (with 6 degrees of freedom).

(Note: The lower rank represents the better performance).

| (a) | |

|---|---|

| Number of Superpixels | Average Ranking |

| 100 Superpixels | 5.00 |

| 50 Superpixels | 4.71 |

| 200 Superpixels | 3.71 |

| 250 Superpixels | 3.29 |

| 300 Superpixels | 3.14 |

| 150 Superpixels | 1.14 |

| (b) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Classification Algorithm | Average Ranking |

|

| STAGE-I | STAGE-II | |

| KNN | 7.00 | 4.29 |

| Naive Bayes | 5.71 | 6.57 |

| Decision Tree | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Logistic Regression | 4.29 | 5.43 |

| SVM (Linear) | 2.43 | 2.57 |

| Ensemble (Boosted Tree) | 2.29 | 2.71 |

| SVM (Cubic) | 1.29 | 1.43 |

Further, as the average ranks of different superpixel setup and classification algorithms are significantly different, therefore it is meaningful to find the pairs where the significant differences occur. To accomplish this, Holm and Nemenyi post-hoc pairwise multiple comparison procedures are used in this study. Initially, the test creates 15 pairs of different superpixel setups for comparison (shown in Table 5 ) and assumes that the performance of each superpixel setup in the pair is equal (null hypothesis). Subsequently, the Holm and Nemenyi procedures reject those pairs with an unadjusted p − value ≤ 0.003846 and p − value ≤ 0.003333, respectively. From the test statistics shown in Table 5, it is found that the performance of superpixel setup for k = 150 performed significantly better compared to the others.

Table 5.

Holm and Nemenyi based pairwise post-hoc multiple comparisons (using p-value and adjusted p-value at significance level α = 0.05) of performance of different superpixel setup using calibration set and 10 fold-cross-validation setups.

| i | Algorithms | p | Holm | Adjusted p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pNemenyi | pHolm | |||||

| 15 | 100 Superpixels vs. 150 Superpixels | 3.857143 | 0.000115 | 0.003333 | 0.001721 | 0.001721 |

| 14 | 50 Superpixels vs. 150 Superpixels | 3.571429 | 0.000355 | 0.003571 | 0.005326 | 0.004971 |

| 13 | 150 Superpixels vs. 200 Superpixels | 2.571429 | 0.010128 | 0.003846 | 0.151920 | 0.131664 |

| 12 | 150 Superpixels vs. 250 Superpixels | 2.142857 | 0.032125 | 0.004167 | 0.481869 | 0.385495 |

| 11 | 150 Superpixels vs. 300 Superpixels | 2.000000 | 0.045500 | 0.004545 | 0.682504 | 0.500503 |

| 10 | 100 Superpixels vs. 300 Superpixels | 1.857143 | 0.063291 | 0.005000 | 0.949362 | 0.632908 |

| 9 | 100 Superpixels vs. 250 Superpixels | 1.714286 | 0.086476 | 0.005556 | 1.297144 | 0.778286 |

| 8 | 50 Superpixels vs. 300 Superpixels | 1.571429 | 0.116083 | 0.006250 | 1.741247 | 0.928665 |

| 7 | 50 Superpixels vs. 250 Superpixels | 1.428571 | 0.153127 | 0.007143 | 2.296912 | 1.071892 |

| 6 | 100 Superpixels vs. 200 Superpixels | 1.285714 | 0.198543 | 0.008333 | 2.978142 | 1.191257 |

| 5 | 50 Superpixels vs. 200 Superpixels | 1.000000 | 0.317311 | 0.010000 | 4.759658 | 1.586553 |

| 4 | 200 Superpixels vs. 300 Superpixels | 0.571429 | 0.567709 | 0.012500 | 8.515637 | 2.270837 |

| 3 | 200 Superpixels vs. 250 Superpixels | 0.428571 | 0.668235 | 0.016667 | 10.023527 | 2.270837 |

| 2 | 50 Superpixels vs. 100 Superpixels | 0.285714 | 0.775097 | 0.025000 | 11.626454 | 2.270837 |

| 1 | 250 Superpixels vs. 300 Superpixels | 0.142857 | 0.886403 | 0.050000 | 13.296045 | 2.270837 |

Besides the test statistics, the significant difference in the performance can be visualized using critical distance (CD) diagram shown in Fig. 13 (a). The CD diagram establishes the comparison between different methods with the help of bars and mean ranks. The bar connects those methods that are not statistically different. From Fig. 13 (a), it can be observed that the performance of superpixel setup with k = 150 (used in this study) performed significantly better compared to k = 50, k = 250 andk = 300.

Fig. 13.

Critical distance diagram with mean rank (at significance level α = 0.05) using Calibration set for (a) Localization performance using the different number of superpixel setup, (b) Different classifiers at STAGE-I, (c) Different classifiers at STAGE-II.

Similarly, for classification algorithms, 21 pairs are created, as shown in Table 6 (for Stage-I) and Table 7 (for Stage-II). The test assumes that all the algorithms performed equally as the null hypothesis. From the obtained statistical results, the Holm and Nemenyi procedures reject those pairs of algorithms that have an unadjusted p − value ≤ 0.003333 (for Holm), p − value ≤ 0.002381 (for Nemenyi) in Stage-I and p − value ≤ 0.003125 (for Holm), p − value ≤ 0.002381(for Nemenyi) in Stage-II. Further, the difference in the performance of different algorithms is shown in Figs. 13(b) and 13(c) for Stage-I and Stage-II, respectively. From the figure, it can be visualized that the performance of SVM (cubic kernel) classifier is significantly better compared to SVM (linear) and Ensemble (boosted tree) for Stage-I. Whereas, in stage-II, it performed considerably better than SVM (linear), Ensemble (boosted tree), and Decision Tree.

Table 6.

Holm and Nemenyi based pairwise post-hoc multiple comparisons (using p-value and adjusted p-value at significance level α = 0.05) of different classification algorithms at STAGE-I using calibration set and 10 fold-cross-validation setups.

| i | Algorithms | p | Holm | Adjusted p-Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pNemenyi | pHolm | |||||

| 21 | SVM (Cubic) vs. KNN | 4.948717 | 0.000001 | 0.002381 | 0.000016 | 0.000016 |

| 20 | Ensemble (Boosted Tree) vs. KNN | 4.082691 | 0.000045 | 0.002500 | 0.000935 | 0.000890 |

| 19 | SVM (Linear) vs. KNN | 3.958973 | 0.000075 | 0.002632 | 0.001581 | 0.001430 |

| 18 | SVM (Cubic) vs. Naive Bayes | 3.835255 | 0.000125 | 0.002778 | 0.002634 | 0.002258 |

| 17 | SVM (Cubic) vs. Decision Tree | 3.216666 | 0.001297 | 0.002941 | 0.027235 | 0.022047 |

| 16 | Ensemble (Boosted Tree) vs. Naive Bayes | 2.969230 | 0.002985 | 0.003125 | 0.062695 | 0.047768 |

| 15 | SVM (Linear) vs. Naive Bayes | 2.845512 | 0.004434 | 0.003333 | 0.093114 | 0.066510 |

| 14 | SVM (Cubic) vs. Logistic Regression | 2.598076 | 0.009375 | 0.003571 | 0.196870 | 0.131247 |

| 13 | Ensemble (Boosted Tree) vs. Decision Tree | 2.350640 | 0.018741 | 0.003846 | 0.393564 | 0.243635 |

| 12 | KNN vs. Logistic Regression | 2.350640 | 0.018741 | 0.004167 | 0.393564 | 0.243635 |

| 11 | SVM (Linear) vs. Decision Tree | 2.226922 | 0.025952 | 0.004545 | 0.545002 | 0.285477 |

| 10 | Ensemble (Boosted Tree) vs. Logistic Regression | 1.732051 | 0.083265 | 0.005000 | 1.748555 | 0.832645 |

| 9 | KNN vs. Decision Tree | 1.732051 | 0.083265 | 0.005556 | 1.748555 | 0.832645 |

| 8 | SVM (Linear) vs. Logistic Regression | 1.608333 | 0.107762 | 0.006250 | 2.263008 | 0.862098 |

| 7 | Naive Bayes vs. Logistic Regression | 1.237179 | 0.216021 | 0.007143 | 4.536432 | 1.512144 |

| 6 | KNN vs. Naive Bayes | 1.113461 | 0.265510 | 0.008333 | 5.575718 | 1.593062 |

| 5 | SVM (Linear) vs. SVM (Cubic) | 0.989743 | 0.322300 | 0.010000 | 6.768292 | 1.611498 |

| 4 | SVM (Cubic) vs. Ensemble (Boosted Tree) | 0.866025 | 0.386476 | 0.012500 | 8.116001 | 1.611498 |

| 3 | Logistic Regression vs. Decision Tree | 0.618590 | 0.536187 | 0.016667 | 11.259922 | 1.611498 |

| 2 | Naive Bayes vs. Decision Tree | 0.618590 | 0.536187 | 0.025000 | 11.259922 | 1.611498 |

| 1 | SVM (Linear) vs. Ensemble (Boosted Tree) | 0.123718 | 0.901539 | 0.050000 | 18.932311 | 1.611498 |

Table 7.

Holm and Nemenyi based pairwise post-hoc multiple comparisons (using p-value and adjusted p-value at significance level α = 0.05) of different classification algorithms at STAGE-II using calibration set and 10 fold-cross-validation setups.

| i | Algorithms | p | Holm | Adjusted p-Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pNemenyi | pHolm | |||||

| 21 | SVM (Cubic) vs. Naive Bayes | 4.453845 | 0.000008 | 0.002381 | 0.000177 | 0.000177 |

| 20 | SVM (Linear) vs. Naive Bayes | 3.464102 | 0.000532 | 0.002500 | 0.011172 | 0.010640 |

| 19 | SVM (Cubic) vs. Logistic Regression | 3.464102 | 0.000532 | 0.002632 | 0.011172 | 0.010640 |

| 18 | Ensemble (Boosted Tree) vs. Naive Bayes | 3.340384 | 0.000837 | 0.002778 | 0.017569 | 0.015059 |

| 17 | SVM (Cubic) vs. Decision Tree | 3.092948 | 0.001982 | 0.002941 | 0.041618 | 0.033690 |

| 16 | SVM (Linear) vs. Logistic Regression | 2.474358 | 0.013348 | 0.003125 | 0.280299 | 0.213561 |

| 15 | SVM (Cubic) vs. KNN | 2.474358 | 0.013348 | 0.003333 | 0.280299 | 0.213561 |

| 14 | Ensemble (Boosted Tree) vs. Logistic Regression | 2.350640 | 0.018741 | 0.003571 | 0.393564 | 0.262376 |

| 13 | SVM (Linear) vs. Decision Tree | 2.103205 | 0.035448 | 0.003846 | 0.744406 | 0.460823 |

| 12 | KNN vs. Naive Bayes | 1.979487 | 0.047761 | 0.004167 | 1.002986 | 0.573135 |

| 11 | Ensemble (Boosted Tree) vs. Decision Tree | 1.979487 | 0.047761 | 0.004545 | 1.002986 | 0.573135 |

| 10 | SVM (Linear) vs. KNN | 1.484615 | 0.137646 | 0.005000 | 2.890563 | 1.376458 |

| 9 | Naive Bayes vs. Decision Tree | 1.360897 | 0.173546 | 0.005556 | 3.644471 | 1.561916 |

| 8 | Ensemble (Boosted Tree) vs. KNN | 1.360897 | 0.173546 | 0.006250 | 3.644471 | 1.561916 |

| 7 | SVM (Cubic) vs. Ensemble (Boosted Tree) | 1.113461 | 0.265510 | 0.007143 | 5.575718 | 1.858573 |

| 6 | KNN vs. Logistic Regression | 0.989743 | 0.322300 | 0.008333 | 6.768292 | 1.933798 |

| 5 | Naive Bayes vs. Logistic Regression | 0.989743 | 0.322300 | 0.010000 | 6.768292 | 1.933798 |

| 4 | SVM (Linear) vs. SVM (Cubic) | 0.989743 | 0.322300 | 0.012500 | 6.768292 | 1.933798 |

| 3 | KNN vs. Decision Tree | 0.618590 | 0.536187 | 0.016667 | 11.259922 | 1.933798 |

| 2 | Logistic Regression vs. Decision Tree | 0.371154 | 0.710523 | 0.025000 | 14.920983 | 1.933798 |

| 1 | SVM (Linear) vs. Ensemble (Boosted Tree) | 0.123718 | 0.901539 | 0.050000 | 18.932311 | 1.933798 |

5. Discussion

Disease localization and severity assessment have become crucial components in automated CAD systems [6,46]. It assists physicians in determining the extent of disease progression and grades the severity to triage the patients and scarce medical resources, specifically in the situations like pandemics [14,37]. In this direction, several works have been reported in the literature that used deep learning approaches to address the issue [6,21,37,82]. However, most of them used the Saliency Maps and Grad-CAM to localize the disease manifestations, which generate a rough disease boundary. To confront this problem, some studies have used superpixel approach to obtain the most out of CAD-assisted interpretation [6,48,49]. Ortiz-Toro et al. [48] has extracted Superpixel-based histon feature, which describes the local correlations of pixel intensity levels in an image. The histon feature is highly sensitive to any variations in the intensity associated with opacities and other abnormalities. However, it should be noted that the author has used contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalisation (CLAHE), which also enhances the normal anatomical structures and noise texture patterns. Chhablani et al. [83] in his study employed a hybrid CNN and Graph Neural Network (GNN) approach to capture spatial information and information from super pixels and suggested improved performance. Another similar study by Prakash et al. [49] utilized gaussian mixture model superpixel and SqueezeNet architecture for COVID-19 infection localization. However, the method extracted superpixels from CAM using a constrained superpixel size, which might miss the larger pathologies. Signoroni et al. [6] designed a multi-block Deep learning architecture, which assigns Brixia score to different lung zones on the basis of infection and superpixel based explainability map. However, the method is biased to segmentation accuracy and radiologist expertise. In addition, the above methods have manly focused on classification and infection segmentation. Thus, in this study, we proposed a superpixel classification based DLSA framework to identify the disease's spatial location and grade the severity. The major issues that we addressed in this study are:

-

-

Selecting an optimal value of ‘k’ to subdivide the lung field into small segments (or superpixels), which resolved the superpixel size tradeoff to capture the small and large pathologies.

-

-

Subtle radiographic disease manifestations with other abnormalities and normal anatomical structures (like soft tissues, bone overlap, etc.) make it very challenging to discriminate the superpixel.

-

-

The generated superpixels vary in size based on the spatial similarity of neighboring regions. Therefore, extracting features from these superpixel results in the feature vector of different lengths.

-

-

While subdivided the lung fields, the number of non-infected superpixels is significantly larger than that of infected superpixels, which substantially affects the performance. Moreover, to train a generalized model, a balanced dataset is required [65].

The results of this study demonstrate that infected region in CXR images can be efficiently identified using multistage superpixel classification approach. Unlike the existing methods [6,48,49] which used texture feature extracted from superpixel or heat map from Super Pixel Pooling Layer to quantify the disease patterns, we extracted both, texture and geometrical shape features from the superpixels. The obtained results using texture features (ACC=93.36%, FM=93.39%, AUC=0.934 for Stage-I, and ACC=81.56%, FM=81.57%, AUC=0.816 for Stage-II) and using combined shape and texture feature (ACC=95.52%, FM=95.48%, AUC=0.955 for Stage-I, and ACC=85.35%, FM=85.20%, AUC=0.853 for Stage-II) reveals the promising performance of the proposed model. The results also reveals that the SVM (cubic kernel) classification method stands out among the others. Similarly, the results of our study shows that the proposed method also achieved promising performance (ACC=93.41%, FM=95.32%, AUC=0.936 for Stage-I and ACC=84.02%, FM=71.01%, AUC=0.795 for Stage-II) using validation dataset, which justify the model's performance using external validation data (not supplied at the time of training). Moreover, in terms of infection localization and severity scoring, the proposed model achieved a good score of average JI: 0.82 and average DC: 0.77, which shows improved localization result compared to the localization approach (using square-shaped dense-grid patches and unsupervised clustering algorithms) presented in [12]. The improved result is due to the fact that superpixel-based infection localization method produces more compact disease marking. Finally, we compared the performance of the proposed model with subjective assessment score of expert radiologist and the results reveal the high degree of agreement (correlation coefficient r=0.9589) between proposed model's performance and expert radiologist score.

Unlike the existing state of the art methods [6,21,37,48,49,82] that employs deep learning approaches for infection localization grading severity, we utilized conventional machine learning algorithms, which could be trained using small number of annotated data and with low computational overload. In addition, the proposed method also generates severity score that could be helpful in patient's triage for optimal allocation of scarce resources. Also, the promising performance of the proposed approach can be justified with the following facts:

-

-

The proposed method leverages the inductive reasoning capability of SVM and its ability to train a generalized model using a small dataset with minimal hyperparameter tuning.

-

-

Spatial similarity-based lung subdivisions generate superpixels that represent the disease manifestations more accurately than other approaches like squared patches or thresholding.

-

-

The superpixel-level augmentation approach generates sufficient instances to balance the class labels at the time of training, which helps to produce a robust model.

-

-

The used texture descriptors (FOSF, GLCM, BoVW) are robust and can efficiently quantify the radiographic disease responses in medical images. Further, the proposed shape features are elegant in quantizing the geometrical irregularities in the shape of infected superpixels. These descriptors generate a feature vector of the same length irrespective of superpixel size.

-

-

The multistage classification approach uses a dedicated, supervised model in each stage, which divides the complex multiclass problem into a small binary problem.

Besides the excellent disease localization and severity performance, some limitations of the proposed approach include (i) Radiographic responses due to multiple bone overlap near the outer periphery of the lungs and soft tissues exhibit subtle appearance with the disease manifestations, which confuses the supervised algorithms resulting in significant misclassification in Stage-II; (ii) The proposed method is trained with limited training data because generating manual ground-truth diseases marking for large dataset is relatively hectic task. Further, to achieve a more concrete conclusion requires further experimentations using a larger dataset; (iii) To the best of the author's knowledge, the existing state of the art studies that used Montgomery dataset have not performed superpixel based disease localization and severity scoring. Therefore, the obtained results could not be compared directly with them (as in both the cases, the base for comparison are not the same).

6. Conclusion

In this study, we tailored a superpixel classification based disease localization and severity assessment framework. The proposed method subdivides the lung fields into small superpixels using SLIC algorithm and used radiomic texture (FOSF, GLCM, BoVW) and proposed shape features to encode different disease manifestations present in each superpixel. Further, the extracted features are used to train the different supervised benchmark algorithms to perform multistage classification. Subsequently, the classified superpixels are used to identify the disease's spatial location and grade the severity. The main conclusions of this study are summarized as follows:

-

-

The proposed multistage classification approach shows satisfactory performance as verified from the obtained classification results i.e. ACC=95.52%, FM=95.48%, AUC=0.955 for Stage-I and ACC=85.35%, FM=85.20%, AUC=0.853 for Stage-II using calibration dataset (in 10-fold cross validation setup) and ACC = 93.41%, FM = 95.32%, AUC = 0.936 for Stage-I and ACC = 84.02%, FM = 71.01%, AUC = 0.795 for Stage-II using validation dataset.

-

-

The method shows promising potential to localize the disease (average JI=0.82, and average DC=0.77), and better agreement between radiologist score and predicted severity score (Pearson's correlation coefficient r = 0.9589) confirms the robustness of the method.

-

-

The combination of different texture features and the proposed superpixel shape features are highly efficient in capturing the disease textural responses and shape irregularities in infected superpixels, respectively.

-

-

The hypothesized superpixel based disease localization approach generates a compact disease marking that more accurately adheres to the disease boundary than the Grad-CAM and saliency map-based techniques.

-

-

Friedman average ranking and Holm and Nemenyi based pairwise post-hoc multiple comparison methods confirm the statistical significance of the obtained results.

From the findings above, it can be concluded that superpixel based lung subdivision significantly improved the localization performance and generate compact disease boundary, which further helps in grading the disease severity accurately. Therefore, this type of CAD system could play an important role in pandemic situations like COVID-19. The future work of this study should concentrate on developing a more robust CAD system, which incorporates classification, localization, and severity scoring at a single and easy-to-use platform. Other direction may consider using chest computed tomography (CT) images for assessment and use larger dataset to validate the generalization capability of the proposed model.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study used a publicly available Montgomery dataset. The dataset is exempted from IRB review (No. 5357) and is de-identified by the data providers. Further, this article does not contain any study performed on animals.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment