Abstract

The cell-cycle is a tightly orchestrated process where sequential steps guarantee cellular growth linked to a correct DNA replication. The entire cell division is controlled by cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). CDK activation is balanced by the activating cyclins and CDK inhibitors whose correct expression, accumulation and degradation schedule the time-flow through the cell cycle phases. Dysregulation of the cell cycle regulatory proteins causes the loss of a controlled cell division and is inevitably linked to neoplastic transformation. Due to their function as cell-cycle brakes, CDK inhibitors are considered as tumor suppressors. The CDK inhibitors p16INK4a and p15INK4b are among the most frequently altered genes in cancer, including hematopoietic malignancies. Aberrant cell cycle regulation in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) bears severe consequences on hematopoiesis and provokes hematological disorders with a broad array of symptoms. In this review, we focus on the importance and prevalence of deregulated CDK inhibitors in hematological malignancies.

Keywords: cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, hematopoiesis, hematopoietic diseases, INK4 family, Cip/Kip family

1 Introduction

Cell-cycle progression is a fundamental biological process which requires tight regulation to guarantee a correct cell division. Perturbations of cell cycle components may provoke an uncontrolled cell proliferation. Dysregulated G1-S transition is a common feature of tumor development and associated with genetic alterations of key regulators of the cell-cycle machinery (1). Based on their function as a cell cycle brake, CDK inhibitors (CKIs) mainly act as tumor suppressors and are frequently deactivated in human neoplasia (2–4).

2 CKIs regulate the cell cycle

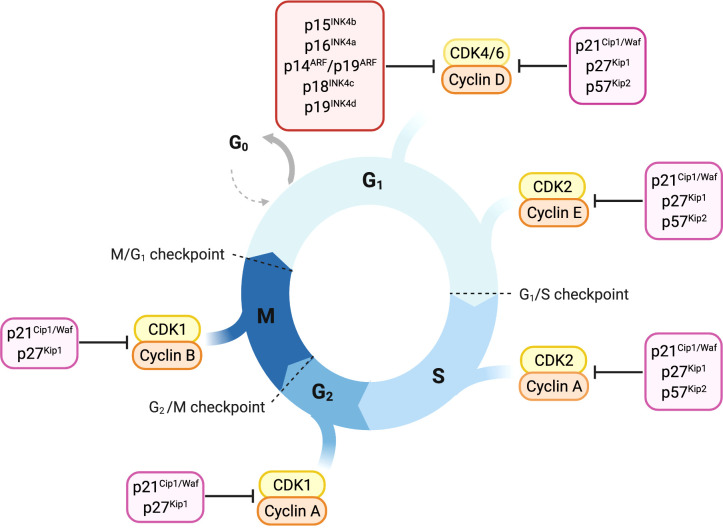

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), their activating cyclins and CDK inhibitors guide cells through the cell cycle ( Figure 1 ). Distinct cyclins are periodically produced and assemble to cyclin-CDK complexes that drive the specific cell-cycle steps, from G1 to M phase. Fine tuning is achieved by inhibitory phosphorylation or binding of CDK inhibitory subunits (CKls) (5–7).

Figure 1.

Overview of cell-cycle control and its main regulators. Progression through cell cycle phases is governed by different CDK-cyclin complexes and the respective cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Members of the INK4 family, p16INK4a, p15INK4b, p18INK4c and p19INK4d, specifically bind and inhibit CDK4/6-cyclin D complexes promoting cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase. The Cip/Kip proteins including p21Cip1/Waf, p27kip1 and p57Kip2, play their role as cell-cycle inhibitors by counteracting a broader spectrum of CDK-cyclin complexes. p21Cip1/Waf, p27kip1 and p57Kip2 restrain cell-cycle both during early and late G1 phase by binding either CDK4/6-cyclin D or CDK2-cyclin E complexes. Later in the cell-cycle, they can bind and inhibit CDK2-cyclin A complex, thus imposing a brake during the S-phase. p21Cip1/Waf and p27kip1 are able to delay entry in the M phase by inhibiting CDK1-cyclin A complex and thereby prevent the progression through mitosis counteracting CDK1-cyclin B complex.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and CDK6 are closely related serine/threonine kinases responsible for driving cells through the G1 phase. Mitogenic signals induce transcription of D-type cyclins (D1, D2 and D3). Their association with CDK4 and CDK6 leads to kinase activation and phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (Rb) (8). CDK-dependent Rb phosphorylation releases Rb from E2F transcription factors and induces transcription of E2F target genes required for S-phase entry (9). G1-S transition is then initiated by CDK2-cyclin E/A complexes, which are active during the entire S-phase (10–12). CDK1 activity is low during G1/S transition but raises during G2-M phase, controlling the initiation of mitosis (13, 14).

CDK-cyclin activity is counterbalanced by members of the two CDK inhibitor families, the INK4 family and the Cip/Kip family (8). p16INK4a, p15INK4b, p18INK4c and p19INK4d are the members of the INK4 family and are specific for CDK4 and CDK6 (15). In response to anti-proliferative signals, INK4 proteins are transcribed and bind CDK4 and CDK6 causing a conformational change which reduces their affinity for D-type cyclins (16).

The Cip/Kip family consists of p21Cip1/Waf, p27Kip1 and p57Kip2. In contrast to INK4 proteins,

Cip/Kip proteins have the ability to bind CDK4/6-cyclin D and CDK-cyclin A/B/E complexes (8, 16–19). p21Cip1/Waf and p27Kip1 are described to have a dual function in cell cycle regulation. Whereas they mainly inhibit CDK-cyclin activity they have been reported to also enhance the assembly of CDK4/6-cyclin D complexes, resulting in a proliferative advantage for the cell (18, 20, 21).

When present at low levels, p21Cip1/Waf preferentially binds to CDK4/6-cyclin D complexes, facilitating complex formation, nuclear localization and cell-cycle progression. In response to DNA damage and p53 stimulation, p21Cip1/Waf accumulates at high levels in a cell and provokes a robust cell cycle arrest by inhibiting CDK2- cyclin E-A complexes (8, 22–25). The mechanism behind these observations is given by in vitro experiments showing that changes in p21Cip1/Waf stoichiometry reflect the conversion of active to inactive cyclin-CDK complexes. Active complexes contain a single p21Cip1/Waf molecule, while two molecules are required for complex inhibition (26, 27).

This double-faced role has been described also for p27Kip1. On the one hand, p27Kip1 binds to the conserved cyclin box residues thus promoting the subsequent complex formation between p27Kip1-cyclin A and CDK2. Upon complex formation, p27Kip1 induces a distortion on the CDK2 N-terminal lobe in proximity of CDK2 catalytic site, thereby preventing ATP binding. On the other hand, phosphorylated p27 Kip1 binds to CDK4 leading to a remodeling of the ATP site and results in increased RB phosphorylation. Data suggest a similar mechanism for p21Cip1/Waf activating CDK4 via phosphorylation sites (28).

p57Kip2 mainly functions during G1-S and G2-M transitions where it blocks any CDK-cyclin complexes. No cell cycle activating mechanisms have been described yet.

The Cip/Kip members, p57Kip2 and p21Cip1/Waf are major players in cellular stress responses, where they balance the induction of cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and senescence (29). p21Cip1/Waf has a unique role as it mediates cell cycle arrest downstream of the tumor suppressor p53 (22). A variety of cellular stresses, such as DNA damage and oncogene activation, stimulate p53 expression, which in turn transactivates its targets including the pro-apoptotic genes Bax, PUMA and Noxa as well as p21Cip1/Waf (30–32). Therefore, p21Cip1/Waf might be an exploitable candidate for therapeutic intervention in p53 mutated tumors.

3 CKIs in hematopoietic stem cells

Under homeostatic conditions, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside in the hypoxic bone marrow niche in a quiescent state (33–35). When needed, HSCs rapidly enter the cell cycle to replenish peripheral hematopoiesis. Self-renewal and differentiation are tightly balanced to maintain the stem cell pool while giving rise to hematopoietic progenitors, which ultimately differentiate into mature blood cells (35, 36). The delicate balance between quiescence and proliferation in HSCs requires a strictly controlled cell cycle progression.

Cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) represent a major break for cell cycle entry and the prevention of uncontrolled proliferation. Several studies started to unravel the impact of CKIs in HSCs (37–40).

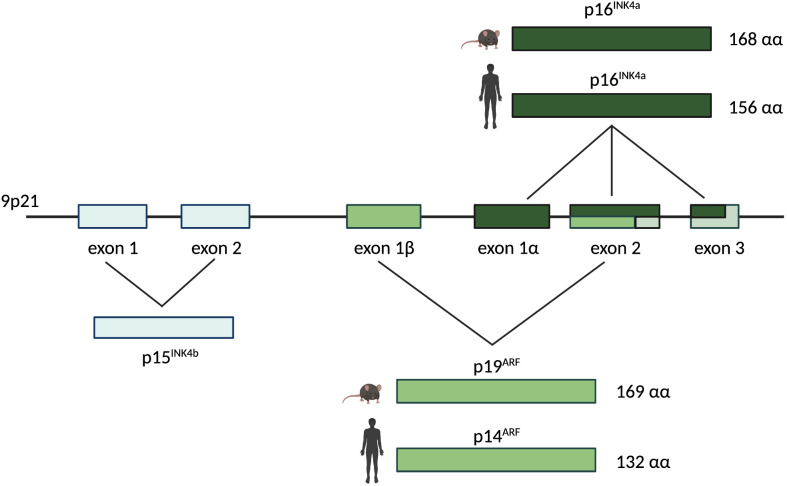

p16INK4a is encoded by exons 1α, 2 and 3 of the INK4a locus ( Figure 2 ). A different transcript derived from the same locus, encoded by the exons 1β, 2 and 3, encodes for the protein p19ARF ( Figure 2 ) which has the capacity to block the cell cycle progression at the G1 and G2 phase (41–43). Thus, the INK4a locus represents a master growth regulator through its capacity to interface with both proliferation (Rb pathway via p16INK4a) and apoptosis (p53 pathway via p19ARF) (4, 44).

Figure 2.

The human/murine INK4a/ARF locus. The INK4a/ARF locus resides on chromosome 9p21 and encodes for two different proteins in human and mouse: p16INK4a and p14ARF (named p19ARF in mouse). The INK4a gene is represented by exons 1α, 2, and 3 and it encodes for p16INK4a, a 168 amino acids protein in mouse and a 156 amino acids protein in human. The ARF gene is composed by exons 1β, 2, and 3. It encodes for p19ARF in mouse (169 amino acids) and for p14ARF in human (132 amino acids). Upstream of the INK4a and ARF genes on the same chromosome, exons 1 and 2 represent the INK4b gene encoding for p15INK4b.

The transcriptional repressor Bmi-1 is part of the Polycomb group and it is present at high levels in HSCs (45–47). Bmi-1 represses the INK4a locus, thus limiting p16INK4a and p19ARF expression (39, 48). Bmi-1 deficiency impairs HSCs self-renewal as it increases p16INK4a and p19ARF levels thereby leading to proliferative arrest and cell death (39). Mice lacking p16INK4a do not show any dramatic effect on hematopoiesis, which could be explained by the reported low p16INK4a expression in normal HSCs (49, 50).

p16INK4a expression increases in HSCs with aging and this is associated with lower HSC numbers. p16INK4a inhibition counteracts the reduced HSC maintenance associated with aging, improves their repopulation ability and mitigates apoptosis (51).

The role of p16INK4a and p19ARF for the regulation of hematopoietic progenitor cells becomes evident in mice harboring a targeted deletion of the INK4a locus that eliminates both proteins. Young p16INK4a-/-/p19ARF-/- mice show extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen with a high proportion of lymphoblasts and megakaryocytes in the red pulp and proliferative expansion of the white pulp. Aging aggravates this phenomenon and extends extramedullary hematopoiesis to nonlymphoid organs (49).

Among the CKIs, p18INK4c is the most powerful player and cell cycle inhibitor involved in murine HSC self-renewal (40, 52). p18INK4c deficient mice show HSCs with enhanced self-renewal ability which leads to the expansion of the HSC pool. This is also evident in serial transplantation experiments where p18INK4c deletion allows for an advanced HSC repopulation ability (40, 53).

Information on p15INK4b and p19INK4d in regulating HSC function is scarce. Characterization of the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells of p15INK4b deficient mice revealed an increased frequency in common myeloid progenitors, but no alterations in the HSC compartment (54, 55).

The need to get first insights into the role of p19INK4d in HSCs leads to the characterization of the hematopoietic system of mice lacking p19INK4d . Knockout mice do not reveal any defect under homeostatic conditions (56). However, in vitro studies highlight the involvement of p19INK4d in megakaryopoiesis, where it regulates the endomitotic cell cycle arrest coupled to terminal differentiation (57).

Moreover, p19INK4d effects become evident when HSCs are exposed to genotoxic stress. In this context, p19INK4d is required to maintain HSCs in a quiescent state, protecting them from apoptosis as genotoxic substances act during the S-phase (58).

The p53 induced CKI p21Cip1/Waf also regulates effects upon stress. Bone marrow transplantation experiments, using cells derived from mice after 2 Gy irradiation show that p21Cip1/Waf deficiency leads to a significantly reduced repopulation ability (37, 59).

In contrast, p27Kip1 knock-out mice lack any perturbations in HSC number, self – renewal ability or cell-cycle state. The role of p27Kip1 is restricted to more committed progenitor cells where its deletion increases proliferation and the pool size of Sca1+Lin+ cells (38).

In quiescent HSCs p57Kip2 dominates as major CKI, where it is expressed at high levels. p57Kip2 deficiency reduces the HSC population, compromises the maintenance of quiescence and impairs repopulation capacity (60).

In summary this led us to conclude that CKIs have distinct essential roles in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells that are only partially understood. Whereas Cip/Kip proteins are predominantly involved in stress responses, INK proteins dominate in the control of hemostatic conditions.

4 Alterations in CKIs

In human cancers the INK4a-ARF-INK4b locus at chromosome 9p21 is one of the most frequently mutated and epigenetically silenced sites (61–63). This locus encodes for the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors p16INK4a and p15INK4b and for the tumor suppressor protein p14ARF (p19ARF in the mouse), which is induced upon p53 activation ( Figure 2 ) (64, 65). Many solid tumors including melanoma, pancreatic adenocarcinomas, esophageal and non-small cell lung carcinoma, harbor mutations in the p16INK4a and p15INK4b genes. In hematological malignancies p16INK4a and p15INK4b are frequently deleted e.g. in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) (66–70).

p18INK4c and p19INK4d , mapped on chromosome 1p32 and 19p13.2 respectively (71, 72), are involved in the development of a more distinct set of tumors. Somatic mutations of p18INK4c are associated with medullary thyroid carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and breast cancer (73–75). Only little information is available regarding the role of p19INK4d in human malignancies; frame shift mutations and rearrangements in the p19INK4d gene have been documented in osteosarcoma (76), while its loss or downregulation have been detected in hepatocellular carcinoma (77) and testicular germ cell tumors (78).

The deletion of the Cip/Kip proteins in mice leads to an increased development of malignancies (79–81), underlining their main role as tumor suppressors. Contradictorily, in some tumor types Cip/Kip proteins also display an oncogenic activity when relocated to the cytoplasm (82–84).

Low p27Kip1 levels are associated with more aggressiveness and poor prognosis in several human cancers (85–87). Control of p27Kip1 levels involves a nuclear to cytoplasmic redistribution which is regulated by phosphorylation sites on distinct residues. Mitogenic signals induce p27Kip1 phosphorylation on Ser10, inducing nuclear export (88, 89), while phosphorylation on Thr198, mediated by PKB/Akt, promotes p27Kip1 association with 14-3-3 proteins and its transport to the cytoplasm (90).

Whereas nuclear p27Kip1 inhibits cell proliferation and suppresses tumor formation, cytoplasmatic p27Kip1 is involved in cytoskeleton rearrangement and contributes to cell migration (82, 89) and may promote metastasis. In some hematologic malignancies (91–93) and carcinomas (such as breast, esophagus, cervix and uterus tumors) (94–98), a positive association of cytoplasmic p27Kip1 levels with a poor clinical outcome has been reported.

p21Cip1/Waf acts as a tumor suppressor in breast, colorectal, gastric, ovarian and oral cancers. Similar to p27Kip1 it may display oncogenic activities when retained in the cytoplasm. p21Cip1/Waf cytoplasmic accumulation is caused by phosphorylation at Thr145 by activated AKT1 (99). Through the association with proteins involved in the apoptotic process, cytoplasmatic p21Cip1/Waf mediates their inhibition, thus exhibiting anti-apoptotic effects. As such, cytoplasmic p21Cip1/Waf is indicative for aggressiveness and poor survival in prostate, cervical, breast and squamous cell carcinomas (100).

In contrast, the role of p57Kip2 is limited at being a tumor suppressor, as there is so far no evidence of an oncogenic role so far (101–104).

Given the extensive knowledge regarding the role of CDK inhibitors in tumor biology there is increasing interest in exploiting them as potential target for cancer treatments. Here we review and discuss the importance they play in hematopoietic malignancies.

5 CKIs in hematologic malignancies

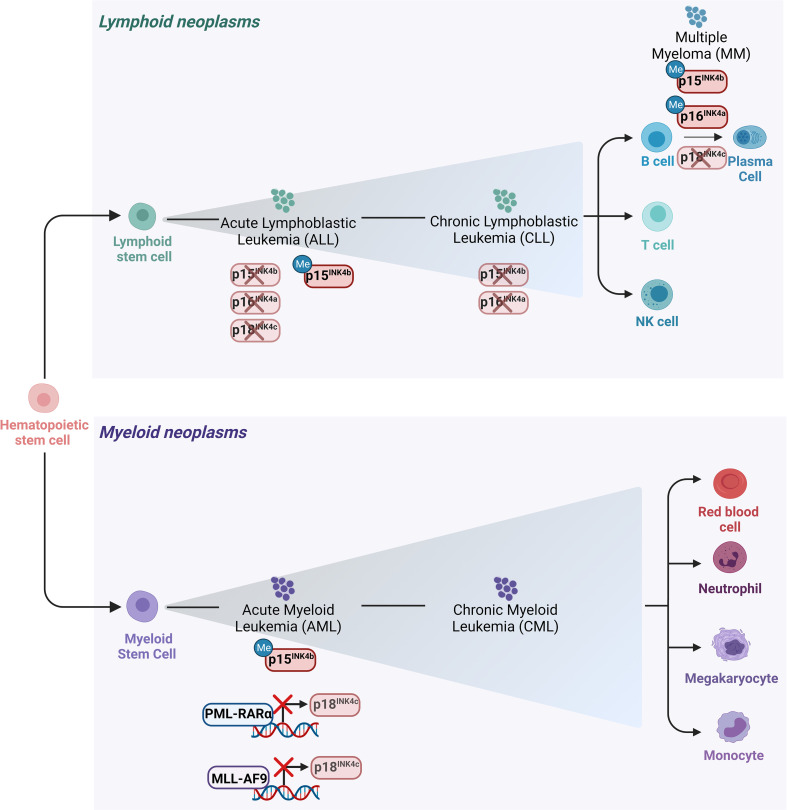

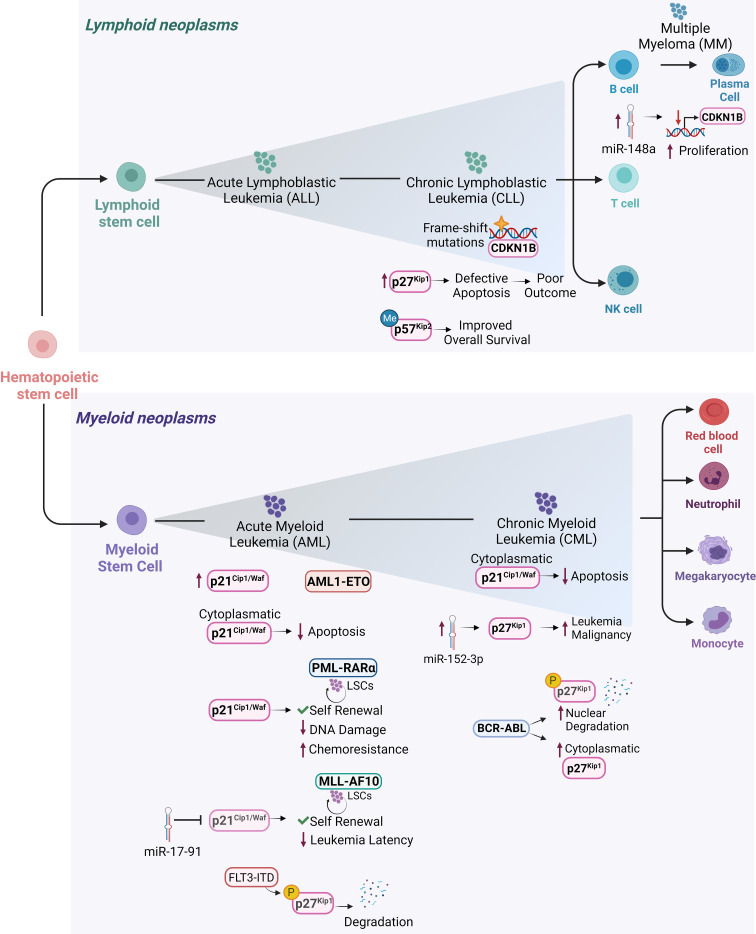

Hematologic malignancies consist of a spectrum of malignant neoplasms that affect bone marrow, blood and lymph nodes and originate from the uncontrolled proliferation of hematopoietic cells. They are driven by genetic and epigenetic aberrations, which can be exploited for diagnosis and therapeutic decisions. The dominant alterations of CKIs are reviewed below and illustrated in Figures 3 , 4 .

Figure 3.

Main alterations of the INK4 proteins in leukemia and lymphomas. Schematic representation of the hematopoietic tree and main alterations affecting the INK4 proteins in different hematopoietic malignancies. Deletion of p15INK4b and p16INK4a together with their 5’ CpG islands hypermethylation in their promoter regions are the most frequent modes of p15INK4b and of p16INK4a inactivation in various subtypes of hematopoietic neoplasms including ALL and CLL. Deletion of p18INK4c has been rarely observed in ALL, whereas it is frequently deleted in MM. p18INK4c is subjected to a transcriptional repression imposed by the oncofusion protein PML-RARα in APL blasts and it is similarly downregulated by MLL-AF9 in cell lines derived from AML patients.

Figure 4.

Cip/Kip proteins main deregulations and functions in different hematopoietic malignancies. Schematic representation of the hematopoietic tree and main functions exerted by Cip/Kip proteins in different hematopoietic malignancies. Increased p21Cip1/Waf levels have been reported in AML1-ETO positive AML patients, where it is believed to support LSCs maintenance and self-renewal ability. p21Cip1/Waf anti-apoptotic functions associated with its cytoplasmatic localization have been observed in AML blasts and in cell lines derived from human CML in blast crisis. In PML-RARα LSCs, p21Cip1/Waf expression maintains self-renewal of LSCs and limits DNA damage, thus protecting them from functional exhaustion and conferring chemoresistance. In MLL-AF10 induced AML, p21Cip1/Waf suppression mediated by miR-17-91 leads to decreased leukemia latency. Elevated p27Kip1 levels in B-CLL where they confer protection against apoptosis, are associated with poor outcome. In hairy cell leukemia, a form of B-CLL, CDKN1B gene encoding for p27Kip1 is the second most common altered gene by frame shift mutations. In MM, higher miR-148a levels correlate with decreased CDKN1B expression leading to sustained proliferation. In CML, overexpression of miR-152-3p targets p27Kip1 and promotes leukemia malignancy. In AML, p27Kip1 is subjected to FLT3-ITD phosphorylation (pY88- p27Kip1) which mediates p27Kip1 degradation. BCR-ABL1+ CML can promote degradation of nuclear p27Kip1 and to increased cytoplasmatic p27Kip1, thus compromising p27Kip1 tumor suppressor activity and promoting leukemic cell survival. p57Kip2 gene has been frequently found methylated in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients, where the low-risk group it is associated with a more favorable overall survival.

5.1 INK4 proteins in leukemia and lymphoma

5.1.1 p16INK4a and p15INK4b

The CDKN2A/B locus encodes for p16INK4a, p14ARF (p19ARF in mice) and p15INK4b. This locus is affected by deletion, mutation or promoter hyper-methylation (62, 63) and frequently altered in patients with hematologic malignancies (4, 105, 106). The design of mouse strains with single or multiple targeted disruptions of the p16INK4a , p19ARF and p15INK4b loci shed light on their distinct roles.

p19ARF-/- mice spontaneously develop a variety of tumors already by the age of 2 months. Analysis of diseased mice shows that T cell lymphoma is the second most common tumor type (107, 108). In line, p19ARF-/- newborn mice exposed either to X-ray or to γ-irradiation develop anaplastic T cell lymphoma (107, 108). In an acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) model, the loss of p19ARF initiates a more aggressive disease BCR-ABL1+ transformation. In this model, p19ARF deletion also confers resistance to the kinase inhibitor imatinib (109). These data suggest a specific role for p19ARF in the lymphoid lineage. Therefore, it would be interesting to analyze if p19ARF could serve as a marker for prognosis and therapeutic outcome.

Homozygous deletion of p16INK4a is not associated with an increased spontaneous cancer development. Of note, the concomitant heterozygous loss of p19ARF in p16INK4a-/- animals increases tumorigenesis and provokes the development of a wide spectrum of malignancies, including lymphoma (110). Importantly, the spontaneous tumors originating from mice harboring the heterozygous loss of p19ARF and p16INK4a homozygous deletion, retain the second p19ARF allele. However, the observed increased tumorigenesis in p16INK4a-/- mice upon heterozygous p19ARF loss underlines the cooperation of the two tumor suppressors.

Young mice show spontaneous tumorigenesis and a higher sensitivity to carcinogenic treatments, especially B cell lymphoma (49).

p15INK4b-/- mice show lymphoproliferative disorders including lymphoid hyperplasia in the spleen and formation of secondary follicles in lymph nodes but rarely develop lymphoma. This suggests that p15INK4b controls homeostasis of the hematopoietic compartment, rather than acting as a tumor suppressor (111).

Although p15INK4b and p16INK4a function as repressors of the cell cycle, in view of the phenotypes shown by the mouse models described above, they seem to have roles in different contexts. p15INK4b is mainly responsible for homeostasis and p16INK4a, together with p19ARF, is more involved in regulating the response to oncogenic stress. This suggests that p16INK4a might function as a sensor of oncogenic signals thus representing a safeguard against neoplasia.

CDK4R24C/CDK6R31C double knock-in mice have been used to address the importance of INK4 inhibitors in regulating CDK4 and CDK6. INK4 binding is prevented by introducing point mutations in CDK4 (R24C) and CDK6 (R31C). The CDK4R24C mutation has been initially identified in hereditary melanoma and shows elevated CDK4 kinase activity (112). So far the CDK6R31C mutation has not been found in patients but is used to investigate CDK6-INK4 interactions. CDK4R24C/CDK6R31C mice show a shortened survival caused by the onset of primary endocrine epithelial or hematopoietic malignancies. Mice injected with CDK4R24C/CDK6R31C BCR-ABL1 transformed cell lines display accelerated tumor growth and reduced disease latency (113). This analysis highlights the crucial importance of INK4 binding to control CDK4/CDK6 activity in hematopoiesis. Therefore, it is attractive to conclude that CDK4/6 inhibitors are effective in patients that lack appropriate INK4-mediated control.

First evidence indicated that the CDKN2 locus in human tumor cell lines derived from solid tumors is predominantly homozygously deleted and thereby p16INK4a becomes inactivated. This was later verified also for leukemia and lymphoma; only a low frequency of point mutations has so far been documented (114–118).

Studies in primary leukemia also identified alterations in p15INK4b . The highest frequency of homozygous deletions of p16INK4a or p15INK4b occurs in ALL, while they are heterozygously deleted in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (114, 119–121). T-ALL is most frequently associated with p16INK4a loss, while p15INK4b deletions are more often observed in pediatric ALL (70, 106, 119, 122–127). Initial studies focused their attention on the frequency of p16INK4a and p15INK4b mutations in adult and childhood ALL (70, 114, 120, 122, 128). Only at later stages the potential of these genes as prognostic factors was taken into account.

The overall incidence of p16INK4a deletion is higher than p15INK4b . Patients with p15INK4b deletions harbor p16INK4a co-deletions, which is not consistently observed vice versa. Cases with homozygous p16INK4a deletion either maintain an unmutated p15INK4b gene or show a hemizygous p15INK4b deletion. These findings point at p16INK4a as the central target of deletions which play the central role for ALL leukemogenesis (70, 119, 120, 123).

The prognostic significance of p16INK4a and p15INK4b deletions remains a matter of debate with contradictory reports: some studies showed an adverse prognostic effect (122, 123, 127, 129–133), which was not confirmed by others (70, 134–136).

Analysis of mixed leukemia types, small patient cohorts or insensitive molecular techniques, like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunocytochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) may have complicated the interpretation. The conclusion of some studies still leaves the potential implication of p16INK4a and p15INK4b deletions in patient prognosis elusive.

Point mutations in the CDKN2A/CDKN2B genes, encoding for p16INK4a and p15INK4b respectively, are sporadically found in human hematopoietic disorders. A comprehensive analysis of 264 T-ALL cases, searching for mutations in cell cycle genes, found CDKN2A/CDKN2B as the most mutated ones (137). Inactivation of p15INK4b and p16INK4a genes can also be based on hypermethylation of the 5’ CpG islands in their promoter regions which induces transcriptional silencing (138). This mode of p16INK4a inactivation is commonly found in breast and colon cancer (139) but also in leukemia and lymphoma. Normal hematopoietic cells lack p15INK4b and p16INK4a promoter hypermethylation, which only occurs de novo upon malignant transformation (140). Interestingly, p15INK4b or p16INK4a seem unaffected at any stage of CML (140), whereas hypermethylation of p15INK4b and p16INK4a is a common event in multiple myeloma (MM) (141). Selective p15INK4b promoter hypermethylation, without p16INK4a alterations, is observed in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndrome and ALL (140, 142–146), whereas Burkitt’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s lymphoma present p16INK4a hypermethylation (140, 141, 147–150).

Overall, the current available data show that inactivation of p15INK4b and p16INK4a in human hematopoietic malignancies is caused by genetic deletion or promoter hypermethylation. Linking these alterations in a well-evaluated cohort of patients would be extremely precious to finally define their role for disease progression and their prognostic relevance. The frequency of their alterations in leukemia and lymphoma is indicative of a central role and renders them promising candidates for novel therapeutic approaches.

5.1.2 p18INK4c

Being the functionally most relevant INK in HSC regulation under stress conditions, it is not surprising that the absence of p18INK4c provokes hematopoietic abnormalities and extramedullary hematopoiesis (111). Mice lacking p18INK4c experience the consequences of the absence of its tumor suppressor function and its role in controlling lymphocyte homeostasis (111, 151). p18INK4c-/- mice spontaneously develop neoplasia including angiosarcoma, testicular tumors, pituitary tumors and lymphoma.

p18INK4c mutations in human hematopoietic malignancies are surprisingly rare in acute leukemias, as they have not been identified in AML and deletions have been reported in just some cases of adult ALL (70, 152, 153). p18INK4c maps on the chromosomal region 1p32. In line with data showing no involvement of p18INK4c in childhood AML (70), no alterations of the 1p region in childhood ALL have been found so far (154). Similarly, no evidence for p18INK4c promoter hypermethylation in acute leukemia has been reported (155).

In MM, p18INK4c is frequently deleted, whereas no point mutations have been detected (156, 157).

In normal B-cells, p18INK4c controls the cell cycle and is involved in the terminal differentiation of B-cells into plasma cells through the inhibition of CDK6 (158, 159). Despite that role, p18INK4c expression is preserved in most lymphoid malignancies (68, 118). The hemizygous loss of p18INK4c has been reported in mantle cell lymphoma, but not in Hodgkin’s lymphoma, where p18INK4c is frequently repressed due to promoter hypermethylation (160–162).

The oncofusion protein PML-RARα which drives acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) directly suppresses p18INK4c expression which is downregulated in APL blasts compared to normal promyelocytes (163).

ChIP-seq experiments of MLL and AF9 in THP-1 cells reveal the CDKN2C locus, encoding for p18INK4c, as a binding region. This indicates that p18INK4c expression is subject to MLL-AF9 mediated regulation (164).

A detailed map of p18INK4c regulation in different leukemic subtypes is still missing and would help clarifying the role of p18INK4c in hematopoietic malignancies and leukemic stem cells (LSCs). The data currently available are indicative for sporadic alterations of p18INK4c in hematologic malignancies.

5.1.3 p19INK4d

The analysis of p19INK4d knock-out mice failed to detect any tumor suppressing effects of p19INK4d. Mice lacking p19INK4d do not spontaneously develop tumors and no abnormalities of the hematopoietic system are evident (56). In line, alterations of p19INK4d are not general hallmarks of hematopoietic neoplasms (76, 165) albeit the data available are scarce. The absence of a mouse phenotype in terms of enhanced cell proliferation and tumor development upon p19INK4d loss suggests a functional compensation exerted by the other INK4 or Cip/Kip proteins.

5.2 Cip/Kip proteins in leukemia and lymphoma

5.2.1 p21Cip1/Waf

p21Cip1/Waf is a key mediator of p53-dependent tumor suppressor functions (22) and acts as a negative regulator of cell cycle progression. p21Cip1/Waf and its role in cellular proliferation have been described in a vast body of literature. Its negative function on cell cycle progression indicates that p21Cip1/Waf may exert tumor suppressive roles and participates in leukemia development even under wild type p53 conditions.

p21Cip1/Waf deficient mice are viable and fertile (166, 167). In those mice, harboring wild type p53, spontaneous tumor development occurs late in life at an average age of 16 months. The variety of malignancies includes tumors of hematopoietic, vascular and epithelial origin. For instance, 14% of all tumors are B-cell lymphoma (168).

The tumor spectrum developed by p21Cip1/Waf deficient mice is remarkably similar to the one observed in p53 deficient mice, which is not surprising keeping in mind the p21Cip1/Waf activation by p53. However, p53 deficient mice are characterized by longer latency. However, p21Cip1/Waf deficient mice do not develop T-cell lymphoma, one of the most frequent tumors arising in p53 deficient mice.

The clinical relevance and potential as a prognostic marker of aberrant p21Cip1/Waf expression has been assessed in various types of human cancers.

Loss of p21Cip1/Waf protein levels correlates with a more advanced tumor stage and worse prognosis in pancreatic cancer (169), while its overexpression has been shown to be associated with poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer (170) and in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients (171).

Interestingly, other studies report low p21Cip1/Waf expression being associated with reduced survival in patients affected by esophageal carcinoma (172, 173).

The relationship between p21Cip1/Waf expression and gastric cancer remains controversial as well. Some authors reported a positive correlation between p21Cip1/Waf expression and favorable prognosis (174, 175), whereas others observed that p21Cip1/Waf expression is associated with poor survival (176).

Analysis of deletions and mutations of p21Cip1/Waf has been carried out in few human hematological malignancies and could be mapped in few subtypes. p21Cip1/Waf alterations are rare in typical mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), but loss of p21Cip1/Waf expression is present in aggressive MCLs harboring wild-type p53 gene (177).

In a large cohort of AML patient blasts, high p21Cip1/Waf expression was found in AML1-ETO positive leukemia (178) with unknown significance. Given its role in maintaining the HSC-pool during normal hematopoiesis (37), one may speculate that it plays a role for LSCs by supporting their self-renewal capacity.

p21Cip1/Waf mutations appear to be not involved in childhood T-ALL pathogenesis, despite extensive studies no mutations were detected (179).

p21Cip1/Waf methylation status in leukemia still remains a debated topic. p21Cip1/Waf hypermethylation was observed in bone marrow cells derived from ALL patients, where it is indicative of a poor prognosis (180). Other studies failed to find any evidence for p21Cip1/Waf methylation in ALL and AML (155, 181, 182).

For instance, p21Cip1/Waf expression appears independent of its promoter methylation status in AML cell lines but correlates with demethylation of p73, a homologue of p53 and a known upstream transcriptional activator of p21Cip1/Waf (183). Treatment of AML cell lines with the methylation inhibitor 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-CdR) results in the induced p21Cip1/Waf expression by p73 demethylation, provoking a cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase (184, 185). Decreased p21Cip1/Waf expression, without any signs of methylation, has been linked to higher disease aggressiveness in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). In line with the data from AML patients, reduced p21Cip1/Waf expression was commonly correlated to p73 methylation (186).

More studies are required to precisely understand how the p21Cip1/Waf methylation status interferes with disease progression and if p73 methylation can be used as a marker for the p21Cip1/Waf status.

In addition to growth arrest, p21Cip1/Waf is involved in apoptosis, DNA repair and senescence. For instance, one of the most extensively studied functions of p21Cip1/Waf is the protection of cells against apoptosis.

An example is given by the usage of histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACI) to induce apoptosis (187–189). p21Cip1/Waf expression is upregulated by an increased histone acetylation of H3K4 at the p21Cip1/Waf promoter region, which is mediated by the HDACI SAHA (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid) (190). p21Cip1/Waf overexpression confers resistance to SAHA-induced apoptosis which was shown in human AML cells. SAHA treatment promotes apoptotic cell death in leukemic cells by inducing pro-apoptotic genes such as TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) and its downstream effector caspase-8. One mechanism through which p21Cip1/Waf exerts anti-apoptotic effects in AML cell lines is the inhibition of caspase-8 cleavage to suppress TRAIL-mediated apoptosis (191).

A second anti-apoptotic function of p21Cip1/Waf was also reported for AML blasts. There, high cytoplasmatic p21Cip1/Waf protein levels provide protection against cytotoxic agents. Blasts with cytoplasmatic p21Cip1/Waf levels show reduced etoposide (VP-16) mediated apoptosis (192). Similarly, the enforced expression of p21Cip1/Waf in CML blast cells confers resistance to Imatinib induced apoptosis (193). These studies suggest that p21Cip1/Waf expression should be investigated to act as a marker for therapeutic outcome.

p21Cip1/Waf expression is essential for the initiation and maintenance of leukemogenesis induced by PML/RAR-transformed HSCs. Under this condition p21Cip1/Waf is required to maintain the self-renewal capacity of LSCs and to limit DNA-damage. p21Cip1/Waf protects from functional exhaustion (194). In line p21Cip1/Waf is crucial for the maintenance of self-renewal and chemoresistance of LSCs in a murine model of T-ALL (195).

In MLL-AF10-induced AML p21Cip1/Waf suppression is achieved by the oncomir miR-17-91, that is associated with enhanced LSC self-renewal and decreased leukemia latency (196). Functional studies for the role of p21Cip1/Waf have been mainly carried out in cell lines from different leukemia subtypes. The literature on primary patient samples is scarce. It appears that the involvement of p21Cip1/Waf is highly context dependent and relies on the differentiation status of the cells and on the driver oncogenes.

The fact that p21Cip1/Waf is important to maintain stem cell self-renewal might provide a basis for novel attempts to target p21Cip1/Waf to induce exhaustion.

5.2.2 p27Kip1

p27Kip1 regulates cell proliferation by inhibiting CDK complexes and arresting cell proliferation in response to anti-mitogenic signals ( Figure 1 ) (8, 197–199).

Analysis of p27Kip1 knock-out mice highlighted the importance of p27Kip1 as cell cycle regulator: p27Kip1 deficient mice have an overall augmented cell proliferation which is reflected in increased body size and hyperplastic organs. Tumor formation becomes manifested spontaneously; pituitary and parathyroid tumors evolve and the mice show an increased susceptibility to tumorigenesis upon γ-irradiation or treatment by the chemical carcinogen N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) (79, 80, 200). These studies defined p27Kip1 as tumor suppressor.

Mutations in the p27Kip 1 gene and its homozygous inactivation are generally rare in human cancers. In people CDKN1B, encoding for p27Kip1, has been identified as the second most common altered gene by frame-shift mutations in heterozygosity in hairy cell leukemia (HCL), a form of B-cell CLL. In most patients the CDKN1B mutation is clonal, thereby suggesting an early role in the pathogenesis of HCL (201, 202).

The subcellular location of p27Kip1 and its concentration determine the impact on malignant transformation. On the one hand, p27Kip1 acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting CDK-cyclin complexes and cell cycle progression when present in the nucleus. On the other hand, a localization shift of p27Kip1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, may promote tumor formation by regulating cytoskeletal structure and cell migration (89).

Augmented levels of p27Kip1 and its cytoplasmic localization have been correlated with poor prognosis and increased metastasis in diverse solid tumors including breast (94), cervix (97) and esophagus (95) carcinomas, as well as in some lymphoma and leukemia (91–93).

Despite a rare mutation rate, p27Kip1 deregulation is one of the key events promoting leukemogenesis. Several mechanisms altering p27Kip1 expression and localization have been described. miRNAs play a prominent role and abundance of p27Kip1 subjected to miRNA-mediated regulation: oncogenic expression of miRNA targeting p27Kip1 translation can cause p27Kip1 loss (203). In CML patients, increased miR-152-3p promotes aggressive behavior of CML cells by targeting p27Kip1 (204). Similarly, miR-148a correlates with low p27Kip1 expression and increased proliferation in MM cells (205).

In lymphoma, low p27Kip1 levels correlate with a poor prognosis (206). Vice versa, high p27Kip1 levels are associated with enhanced disease-free survival in AML, indicative for disease progression (207).

In contrast, AML patients with low p27Kip1 due to deletion of the chromosomal region 12p13, have a better overall survival. Although together with CDKN1B, nine other genes are located in the 12p13 chromosomal region, the reported improved clinical outcome can be ascribed to reduced CDKN1B expression levels which might lead to higher cell proliferation which makes leukemic cells more susceptible to cytotoxic agents (208).

Besides the genomic alterations, also the phosphorylation sites play an important role for p27Kip1 levels. p27Kip1 is a substrate of FLT3 and FLT3-ITD in AML patient samples, where they phosphorylate p27Kip1 at the residue Y88 which is required for subsequent p27Kip1 phosphorylation at T187 by the CDK2-cyclin complex marking p27Kip1 for SCFSkp2-mediated degradation. FLT3 inhibition reduces pY88-p27Kip1 and increases p27Kip1 levels leading to cell cycle arrest (209).

High p27Kip1 levels are associated with a poor outcome in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL). In B-CLL disease progression does not result from uncontrolled cell proliferation but is the result of defective apoptosis and enhanced cell survival. High p27Kip1 expression is discussed to contribute to the protection against apoptotic stimuli like p21Cip1/Waf (93).

The presence of high p27Kip1 levels in CLL was confirmed by others who also found an inverse correlation with c-Myc protein levels. C-Myc deregulation is a frequent event in leukemia and lymphoma (210, 211). Low Myc levels are associated with low expression of its target gene Skp2, a component of the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase complex that degrades p27Kip1. The reduced Skp2-mediated degradation leads to the p27Kip1 accumulation which confers resistance to apoptosis (210).

In untransformed CD34+ progenitor cells, β1-integrin engagement increases p27Kip1 nuclear levels, which in turn decrease CDK2 activity thus restraining G1/S-phase progression. BCR-ABL expression in CML CD34+ cells induces elevated cytoplasmatic p27Kip1 levels. In this context, such high p27Kip1 levels do not restrain CML cell proliferation due to its cytoplasmatic relocation, thereby contributing to the loss of integrin-mediated proliferation inhibition observed in normal CD34+ cells (212).

More recent studies demonstrate that BCR-ABL1 promotes leukemia by subverting nuclear p27Kip1 tumor-suppressor function via two independent mechanisms. In a kinase-dependent manner, BCR-ABL1 induces SCFSkp2 expression through the PI3K pathway (213), promoting the degradation of nuclear p27Kip1, thus compromising its tumor-suppressor activity. In a kinase-independent fashion it increases cytoplasmatic p27Kip1 abundance, preventing apoptosis and thereby promoting leukemic cell survival (214, 215).

The overexpression of a stable p27Kip1 harboring two point mutations which prevent its phosphorylation on sites responsible for its SCFSkp2-mediated nuclear degradation (T187A) and for its PI3K-directed cytoplasmatic sequestration (T157A) causes a G1/S arrest, markedly inhibiting proliferation of BCR-ABL+ cells (216).

The complexity of the regulation mechanism regulation location and degradation require further investigations to define disease entities where p27Kip1 may serve as clinical marker.

5.2.3 p57Kip2

Based on its ability to inhibit G1-S phase cyclin-CDK complexes, p57Kip2 is considered a tumor suppressor. As mentioned above for p21Cip1/Waf and p27Kip1, p57Kip2 is involved in many cellular processes including apoptosis, and cellular migration.

The fact that p57Kip2 has a crucial role during embryogenesis and is required for normal embryonic development makes it unique under der CKI family. p57Kip2 knock-out mice show severe developmental defects and display increased embryonic and perinatal lethality (217, 218) which complicated further studies on tumorigenesis in mice and most studies rely on human patient samples.

Reduced p57Kip2 expression is associated with high tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis in several types of tumors, such as gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, breast and lung carcinoma as well as leukemia (103, 104, 219–221). p57Kip2 expression is decreased in MDS, in particular in patients with a poor karyotype. Low expression results from an impaired response to the SDF-1/CXCR4 signal which induces p57Kip2 expression (222). p57Kip2 knock-out mice show hyperproliferation and differentiation delay in several tissues (218), which are features associated with the pathogenesis of MDS (223).

Another described mechanism how p57Kip2 expression is altered is promoter methylation. Hypermethylation of the CDKN1C gene, encoding for p57Kip2, occurs in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma, ALL (224, 225) and nodal DLBCL (226). In the low-risk group of DLBCL, CDKN1C methylation is associated with a more favorable overall survival. The authors proposed aberrant CDKN1C promoter methylation as a biological marker in patients with DLBCL (226). Another study in DLBCL patients suggested that the analysis of CDKN1C methylation status may serve as a biomarker for the detection of minimal residual disease, underlining the importance of p57Kip2 for determining leukemia relapse risk (227).

Analysis of the p57Kip2 methylation status in adult and childhood ALL found a rate of 50% CDKN1C hypermethylation in adult ALL but only 7% hypermethylation in childhood leukemia (226). Interestingly, in 53% of the childhood ALL samples p57Kip2 was absent without methylation and overall p57Kip2 levels were 8-fold lower compared to normal lymphocytes. The low expression points at additional ways to regulate p57Kip2 in this particular disease class (228). In line, p57Kip2 methylation and protein expression in adult ALL patients does not show any correlation as 10 out of 15 patients with CDKN1C hypermethylation expressed p57Kip2 (229).

Overall, methylation status of p57Kip2 does not seem to be a reliable marker for p57Kip2 levels. Conditional knockout mice would be a useful tool to study the role of p57Kip2 in hematopoietic diseases in more detail.

6 Pharmacologic CDK inhibition in hematologic malignancies

CDK kinase inhibitors are under extensive investigation in numerous preclinical and clinical studies in a variety of solid tumors and they are currently tested in hematological neoplasms (230, 231).

Pan-CDK inhibitors represented the very first generation of CDK inhibitors with the function to restrain cell proliferation via the inhibition of the CDK enzymatic activity. Flavopiridol was the first CDK inhibitor used in clinical trials and tested for the treatment of ALL, AML and CLL (232–234). Due to their low selectivity causing severe cytotoxic effects in healthy cells and a wide range of side effects, pan-CDK inhibitors have been discontinued in clinical trials (113, 235).

Considering the key role of CDK6 in malignant hematopoiesis it represents an effective therapeutic target (236–238). This is underlined by the high frequency of p15INK4b and p16INK4a inactivation in leukemia and lymphoma. The development of more specific CDK inhibitors, including CDK4/6-kinase inhibitors, represented an exciting turn over in the field (239).

Palbociclib is a CDK4/6 kinase inhibitor that acts by blocking enzymatic functions by mimicking INK4 binding. Palbociclib has been FDA approved to treat breast cancer patients and clinical trials exploring its effects in hematological malignancies are ongoing. Richter et al. present in their recent work (231) an extensive and detailed collection of preclinical and clinical studies conducted with several CDK4/6 inhibitors in hematological diseases.

Palbociclib resistance is a common phenomenon in breast cancer patients (240, 241). In breast cancer and AML high levels of p16INK4a and p18INK4c are associated with resistance to Palbociclib and to a CDK6 protein degrader that is based on the structure of Palbociclib. Despite this correlation, low p16INK4a levels are not predictive for Palbociclib sensitivity (242). All INK4 proteins are in principle capable to prevent Palbociclib binding to CDK6 and thereby capable to induce resistance. Whether this fact is also true for other CDK inhibitors needs to be investigated. The cell-type specific expression of INK4 proteins needs also to be taken into consideration when studying CDK-inhibitors resistance.

The challenge in the development of novel inhibitors is in the design of molecules able to reduce the side effects and to overcome drug resistance. An innovative approach of CDK inhibition would consider the possibility to mimic the functions of INK4 proteins for a selective inactivation of CDKs. However, intensive research is needed to fill the need of X-ray crystal structures of most of the CDKs and CDKs/INK4/Cip/Kip complexes and to make this creative approach possible.

7 Discussion

INK4 and Cip/Kip proteins were initially identified as CDK inhibitors and negative regulators of cell cycle progression. Only recently, the involvement in other cellular processes including apoptosis and cell migration was uncovered. Thereby CKIs bridge cell cycle regulation to other cellular functions. Under certain circumstances CKIs may even promote cancer progression.

Tumor cells frequently display mutations in CKIs which underscores the significance of these proteins for tumorigenesis. We here summarize the dominant alterations of CKIs in hematopoietic malignancies and discuss their consequences for disease development, maintenance, and diagnosis.

Within the INK4 family, p15INK4b and p16INK4a are most frequently inactivated in leukemia and lymphoma either by deletion or hypermethylation of 5’ CpG islands in their promoter regions (114–116, 118, 140–150). The prognostic importance of these alterations in distinct disease entities remains unclear. Considering the unique functions of each INK4 proteins, especially their role under stress conditions, one could speculate that distinct expression patterns lead to different disease subtypes and dictates therapeutic outcomes.

CDK4/6 specific inhibitors represent a promising valuable choice for the treatment of hematological malignancies. However, resistance to CDK inhibitor therapy has been frequently observed. INK4 proteins are capable of inducing resistance by binding to CDK6. Studies are needed to evaluate whether this holds true for other CDK inhibitors.

As proliferation and cell cycle control are essential features of a cell, the components of the cell cycle machinery are present in multiple variants, which can substitute for each other. INK4 proteins share common tasks and, in a similar manner, CDKs may substitute for each other. This complexity makes it exceedingly difficult to generalize any consequence upon loss or mutations of a single player. Effects will also be context and cell type dependent.

This enormous plasticity of the cell cycle machinery to adapt ensures cell proliferation and presents a major challenge when it comes to predict therapeutic outcomes of drugs interfering with CDKs or INKs. The removal or inhibition of a single player may be rapidly compensated by a rearrangement of CDK complexes.

Another layer of complexity is induced by the emerging CDK6 kinase-independent functions that regulate transcriptional processes relevant for leukemia. The involvement of CDK6 in LSCs biology makes it an attractive target for leukemia therapy (238, 243). It is unclear how CKIs binding to CDK6 interferes with the transcriptional role of CDK6. It is also unknown whether INK4 or Cip/Kip binding to CDK6 alters the composition of CDK6 containing transcriptional complexes and/or chromatin location. We need to understand how CDK-CKIs complexes interfere with cell cycle-independent functions to reliable predict treatment outcomes. Moreover, effects of kinase inhibitor treatment on the kinase-independent functions of CDK6 are still enigmatic. The frequent upregulation of CDK6 (237, 235) in hematopoietic tumors (243, 244) and the fact that alterations of INK4 proteins are commonly found in hematopoietic tumors demands for the understanding of any CDK6-INK4 correlation in leukemia/lymphoma to exploit CDK4/6 inhibitors in hematopoietic malignancies.

Despite the importance of p18INK4d for HSC self-renewal under homeostatic and stress conditions (40, 52,53), p18INK4d mutations are not a hallmark of hematopoietic malignancies. p18INK4d deregulation is rarely observed in hematopoietic neoplasms. Alterations on the transcriptional/translational level cannot be entirely excluded. As such the oncogene MLL-AF9 regulates p18INK4d. In line, the comparison of AML subtypes identified distinct INK4 expression patterns for different AML entities. The global analysis of the protein levels of individual CIKs in respect to their hematopoietic disease type is required to design tailored treatment strategies.

We are only starting to understand and appreciate functions of the Cip/Kip proteins in regulating apoptosis and cell migration. The involvement of Cip/Kip in tumorigenesis is an attractive emerging field of research and will open novel innovative therapeutic avenues.

p21Cip1/Waf has a dual context-dependent role in leukemogenesis and acts as tumor suppressor and promoter. In cell lines, the anti-apoptotic effect of cytoplasmatic p21Cip1/Waf confers a survival advantage and mediates chemoresistance. Inhibition of p21Cip1/Waf under these conditions bears the potential to sensitize leukemic cells to chemotherapy. Similarly, cytoplasmatic p27Kip1 prevents apoptosis and may be exploited as potential therapeutic target. Most studies rely on cell lines and this only partially reflects the in vivo situation. The reality-check in patients is still missing to judge the clinical relevance of these observations. Therapeutic strategies that simultaneously target oncogenic Cip/Kip functions while preserving tumor suppressive functions would represent an innovative optimal approach.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial, direct, and intellectual contributions to the work. KK was the principal investigator and takes primary responsibility for the paper. AS, VS and KK wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access Funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), project grant P 31773 (KK), and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, grant agreement no. 694354 (VS).

Acknowledgments

Graphics were created with BioRender.com (24 March 2022). Open Access Funding by the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science (1996) 274:1672–7. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sherr CJ. The pezcoller lecture: Cancer cell cycles revisited. Cancer Res (2000) 60:3689–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malumbres M, Barbacid M. To cycle or not to cycle: a critical decision in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer (2001) 1:222–31. doi: 10.1038/35106065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ruas M, Peters G. The p16INK4a/CDKN2A tumor suppressor and its relatives. Biochim Biophys Acta (1998) 1378:F115–177. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00017-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morgan DO. Principles of CDK regulation. Nature (1995) 374:131–4. doi: 10.1038/374131a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morgan DO. Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol (1997) 13:261–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hartwell LH, Weinert TA. Checkpoints: Controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science (1989) 246:629–34. doi: 10.1126/science.2683079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev (1999) 13:1501–12. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Classon M, Harlow E. The retinoblastoma tumour suppressor in development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer (2002) 2:910–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Verde F, Ansorge W, Draetta G. Cyclin a is required at two points in the human cell cycle. EMBO J (1992) 11:961–71. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Lukas J, Baldin V, Ansorge W, Bartek J, et al. Regulation of the cell cycle by the cdk2 protein kinase in cultured human fibroblasts. J Cell Biol (1993) 121:101–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.1.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsai LH, Lees E, Faha B, Harlow E, Riabowol K. The cdk2 kinase is required for the G1-to-S transition in mammalian cells. Oncogene (1993) 8:1593–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liao H, Ji F, Ying S. CDK1: beyond cell cycle regulation. Aging (Albany NY) (2017) 9:2465–6. doi: 10.18632/aging.101348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bashir T, Pagano M. Cdk1: the dominant sibling of Cdk2. Nat Cell Biol (2005) 7:779–81. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ekholm SV, Reed SI. Regulation of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases in the mammalian cell cycle. Curr Opin Cell Biol (2000) 12:676–84. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00151-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Russo AA, Tong L, Lee JO, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Structural basis for inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk6 by the tumour suppressor p16INK4a. Nature (1998) 395:237–43. doi: 10.1038/26155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blain SW, Montalvo E, Massagué J. Differential interaction of the cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitor p27Kip1 with cyclin a-Cdk2 and cyclin D2-Cdk4. J Biol Chem (1997) 272:25863–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. LaBaer J, Garrett MD, Stevenson LF, Slingerland JM, Sandhu C, Chou HS, et al. New functional activities for the p21 family of CDK inhibitors. Genes Dev (1997) 11:847–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. James MK, Ray A, Leznova D, Blain SW. Differential modification of p27Kip1 controls its cyclin d-cdk4 inhibitory activity. Mol Cell Biol (2008) 28:498–510. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02171-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sugimoto M, Martin N, Wilks DP, Tamai K, Huot TJG, Pantoja C, et al. Activation of cyclin D1-kinase in murine fibroblasts lacking both p21(Cip1) and p27(Kip1). Oncogene (2002) 21:8067–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng M, Olivier P, Diehl JA, Fero M, Roussel MF, Roberts JM, et al. The p21(Cip1) and p27(Kip1) CDK “inhibitors” are essential activators of cyclin d-dependent kinases in murine fibroblasts. EMBO J (1999) 18:1571–83. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. El-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, et al. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell (1993) 75:817–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge SJ. The p21 cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell (1993) 75:805–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev (1995) 9:1149–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leonardo AD, Linke SP, Clarkin K, Wahl GM. DNA Damage triggers a prolonged p53-dependent G1 arrest and long-term induction of Cip1 in normal human fibroblasts. Genes Dev (1994) 8:2540–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang H, Hannon GJ, Beach D. p21-containing cyclin kinases exist in both active and inactive states. Genes Dev (1994) 8:1750–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.15.1750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Keyomarsi K, Dynlacht B, Tsai LH, Zhang P, et al. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by p21. MBoC (1995) 6:387–400. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.4.387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guiley KZ, Stevenson JW, Lou K, Barkovich KJ, Kumarasamy V, Wijeratne TU, et al. p27 allosterically activates cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and antagonizes palbociclib inhibition. Science (2019) 366:eaaw2106. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rossi MN, Antonangeli F. Cellular response upon stress: p57 contribution to the final outcome. Mediators Inflammation (2015) 2015:259325. doi: 10.1155/2015/259325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. El-Deiry WS. The role of p53 in chemosensitivity and radiosensitivity. Oncogene (2003) 22:7486–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mandinova A, Lee SW. The p53 pathway as a target in cancer therapeutics: Obstacles and promise. Sci Trans Med (2011) 3:64rv1–1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the light: The growing complexity of p53. Cell (2009) 137:413–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells (1978) 4:7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wilson A, Trumpp A. Bone-marrow haematopoietic-stem-cell niches. Nat Rev Immunol (2006) 6:93–106. doi: 10.1038/nri1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seita J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cell: self-renewal versus differentiation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med (2010) 2:640–53. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Giebel B, Bruns I. Self-renewal versus differentiation in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells: a focus on asymmetric cell divisions. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther (2008) 3:9–16. doi: 10.2174/157488808783489444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cheng T, Rodrigues N, Shen H, Yang Y, Dombkowski D, Sykes M, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science (2000) 287:1804–8. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cheng T, Rodrigues N, Dombkowski D, Stier S, Scadden DT. Stem cell repopulation efficiency but not pool size is governed by p27(kip1). Nat Med (2000) 6:1235–40. doi: 10.1038/81335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Park I, Qian D, Kiel M, Becker MW, Pihalja M, Weissman IL, et al. Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature (2003) 423:302–5. doi: 10.1038/nature01587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yuan Y, Shen H, Franklin DS, Scadden DT, Cheng T. In vivo self-renewing divisions of haematopoietic stem cells are increased in the absence of the early G1-phase inhibitor, p18INK4C. Nat Cell Biol (2004) 6:436–42. doi: 10.1038/ncb1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stone S, Jiang P, Dayananth P, Tavtigian SV, Katcher H, Parry D, et al. Complex structure and regulation of the P16 (MTS1) locus. Cancer Res (1995) 55:2988–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mao L, Merlo A, Bedi G, Shapiro GI, Edwards CD, Rollins BJ, et al. A novel p16INK4A transcript. Cancer Res (1995) 55:2995–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ouelle DE, Zindy F, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ. Alternative reading frames of the INK4a tumor suppressor gene encode two unrelated proteins capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cell (1995) 83:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90214-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sharpless NE, DePinho RA. The INK4A/ARF locus and its two gene products. Curr Opin Genet Dev (1999) 9:22–30. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lessard J, Baban S, Sauvageau G. Stage-specific expression of polycomb group genes in human bone marrow cells. Blood (1998) 91:1216–24. doi: 10.1182/blood.V91.4.1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lessard J, Schumacher A, Thorsteinsdottir U, van Lohuizen M, Magnuson T, Sauvageau G. Functional antagonism of the polycomb-group genes eed and Bmi1 in hemopoietic cell proliferation. Genes Dev (1999) 13:2691–703. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Park I-K, He Y, Lin F, Laerum OD, Tian Q, Bumgarner R, et al. Differential gene expression profiling of adult murine hematopoietic stem cells. Blood (2002) 99:488–98. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lessard J, Sauvageau G. Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature (2003) 423:255–60. doi: 10.1038/nature01572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Serrano M, Lee H, Chin L, Cordon-Cardo C, Beach D, DePinho RA. Role of the INK4a locus in tumor suppression and cell mortality. Cell (1996) 85:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81079-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Passegué E, Wagers AJ, Giuriato S, Anderson WC, Weissman IL. Global analysis of proliferation and cell cycle gene expression in the regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell fates. J Exp Med (2005) 202:1599–611. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Janzen V, Forkert R, Fleming HE, Saito Y, Waring MT, Dombkowski DM, et al. Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a. Nature (2006) 443:421–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gao Y, Yang P, Shen H, Yu H, Song X, Zhang L, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors targeting INK4 protein p18(INK4C) enhance ex vivo expansion of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Commun (2015) 6:6328. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yu H, Yuan Y, Shen H, Cheng T. Hematopoietic stem cell exhaustion impacted by p18 INK4C and p21 Cip1/Waf1 in opposite manners. Blood (2006) 107:1200–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rosu-Myles M, Wolff L. p15Ink4b: dual function in myelopoiesis and inactivation in myeloid disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis (2008) 40:406–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rosu-Myles M, Taylor BJ, Wolff L. Loss of the tumor suppressor p15Ink4b enhances myeloid progenitor formation from common myeloid progenitors. Exp Hematol (2007) 35:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zindy F, van Deursen J, Grosveld G, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. INK4d-deficient mice are fertile despite testicular atrophy. Mol Cell Biol (2000) 20:372–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.1.372-378.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gilles L, Guièze R, Bluteau D, Cordette-Lagarde V, Lacout C, Favier R, et al. P19INK4D links endomitotic arrest and megakaryocyte maturation and is regulated by AML-1. Blood (2008) 111:4081–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hilpert M, Legrand C, Bluteau D, Balayn N, Betems A, Bluteau O, et al. p19INK4d controls hematopoietic stem cells in a cell-autonomous manner during genotoxic stress and through the microenvironment during aging. Stem Cell Rep (2014) 3:1085–102. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. van Os R, Kamminga LM, Ausema A, Bystrykh LV, Draijer DP, van Pelt K, et al. A limited role for p21Cip1/Waf1 in maintaining normal hematopoietic stem cell functioning. Stem Cells (2007) 25:836–43. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Matsumoto A, Takeishi S, Kanie T, Susaki E, Onoyama I, Tateishi Y, et al. p57 is required for quiescence and maintenance of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell (2011) 9:262–71. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ortega S, Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cyclin d-dependent kinases, INK4 inhibitors and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta (2002) 1602:73–87. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00037-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gil J, Peters G. Regulation of the INK4b–ARF–INK4a tumour suppressor locus: all for one or one for all. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2006) 7:667–77. doi: 10.1038/nrm1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gu F, Pfeiffer RM, Bhattacharjee S, Han SS, Taylor PR, Berndt S, et al. Common genetic variants in the 9p21 region and their associations with multiple tumours. Br J Cancer (2013) 108:1378–86. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Weber JD, Taylor LJ, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ, Bar-Sagi D. Nucleolar arf sequesters Mdm2 and activates p53. Nat Cell Biol (1999) 1:20–6. doi: 10.1038/8991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sherr CJ. The INK4a/ARF network in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2001) 2:731–7. doi: 10.1038/35096061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liggett WH, Sidransky D. Role of the p16 tumor suppressor gene in cancer. J Clin Oncol (1998) 16:1197–206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Okamoto A, Demetrick DJ, Spillare EA, Hagiwara K, Hussain SP, Bennett WP, et al. Mutations and altered expression of p16INK4 in human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (1994) 91:11045–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Otsuki T, Clark HM, Wellmann A, Jaffe ES, Raffeld M. Involvement of CDKN2 (p16INK4A/MTS1) and p15INK4B/MTS2 in human leukemias and lymphomas. Cancer Res (1995) 55:1436–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sill H, Goldman JM, Cross NCP. Homozygous deletions of the p16 tumor-suppressor gene are associated with lymphoid transformation of chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood (1995) 85:2013–6. doi: 10.1182/blood.V85.8.2013.bloodjournal8582013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Takeuchi S, Bartram CR, Seriu T, Miller CW, Tobler A, Janssen JW, et al. Analysis of a family of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors: p15/MTS2/INK4B, p16/MTS1/INK4A, and p18 genes in acute lymphoblastic leukemia of childhood. Blood (1995) 86:755–60. doi: 10.1182/blood.V86.2.755.bloodjournal862755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Guan KL, Jenkins CW, Li Y, Nichols MA, Wu X, O’Keefe CL, et al. Growth suppression by p18, a p16INK4/MTS1- and p14INK4B/MTS2-related CDK6 inhibitor, correlates with wild-type pRb function. Genes Dev (1994) 8:2939–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.2939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Guan KL, Jenkins CW, Li Y, O’Keefe CL, Noh S, Wu X, et al. Isolation and characterization of p19INK4d, a p16-related inhibitor specific to CDK6 and CDK4. Mol Biol Cell (1996) 7:57–70. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.1.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. van Veelen W, Klompmaker R, Gloerich M, van Gasteren CJR, Kalkhoven E, Berger R, et al. P18 is a tumor suppressor gene involved in human medullary thyroid carcinoma and pheochromocytoma development. Int J Cancer (2009) 124:339–45. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Morishita A, Masaki T, Yoshiji H, Nakai S, Ogi T, Miyauchi Y, et al. Reduced expression of cell cycle regulator p18(INK4C) in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology (2004) 40:677–86. doi: 10.1002/hep.20337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lapointe J, Lachance Y, Labrie Y, Labrie C. A p18 mutant defective in CDK6 binding in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res (1996) 56:4586–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Miller CW, Yeon C, Aslo A, Mendoza S, Aytac U, Koeffler HP. The p19INK4D cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor gene is altered in osteosarcoma. Oncogene (1997) 15:231–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Morishita A, Gong J, Deguchi A, Tani J, Miyoshi H, Yoshida H, et al. Frequent loss of p19INK4D expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: relationship to tumor differentiation and patient survival. Oncol Rep (2011) 26:1363–8. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bartkova J, Thullberg M, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Skakkebaek NE, Bartek J. Lack of p19INK4d in human testicular germ-cell tumours contrasts with high expression during normal spermatogenesis. Oncogene (2000) 19:4146–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Nakayama K, Ishida N, Shirane M, Inomata A, Inoue T, Shishido N, et al. Mice lacking p27Kip1 display increased body size, multiple organ hyperplasia, retinal dysplasia, and pituitary tumors. Cell (1996) 85:707–20. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81237-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Fero ML, Rivkin M, Tasch M, Porter P, Carow CE, Firpo E, et al. A syndrome of multiorgan hyperplasia with features of gigantism, tumorigenesis, and female sterility in p27Kip1-deficient mice. Cell (1996) 85:733–44. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81239-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Denicourt C, Dowdy SF. Cip/Kip proteins: more than just CDKs inhibitors. Genes Dev (2004) 18:851–5. doi: 10.1101/gad.1205304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Besson A, Assoian RK, Roberts JM. Regulation of the cytoskeleton: an oncogenic function for cdk inhibitors? Nat Rev Cancer (2004) 4:948–55. doi: 10.1038/nrc1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Roninson IB. Oncogenic functions of tumour suppressor p21(Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1): association with cell senescence and tumour-promoting activities of stromal fibroblasts. Cancer Lett (2002) 179:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00847-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Gartel AL. Is p21 an oncogene? Mol Cancer Ther (2006) 5:1385–6. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Slingerland J, Pagano M. Regulation of the cdk inhibitor p27 and its deregulation in cancer. J Cell Physiol (2000) 183:10–7. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Philipp-Staheli J, Payne SR, Kemp CJ. p27(Kip1): regulation and function of a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor and its misregulation in cancer. Exp Cell Res (2001) 264:148–68. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bloom J, Pagano M. Deregulated degradation of the cdk inhibitor p27 and malignant transformation. Semin Cancer Biol (2003) 13:41–7. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00098-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Boehm M, Yoshimoto T, Crook MF, Nallamshetty S, True A, Nabel GJ, et al. A growth factor-dependent nuclear kinase phosphorylates p27(Kip1) and regulates cell cycle progression. EMBO J (2002) 21:3390–401. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. McAllister SS, Becker-Hapak M, Pintucci G, Pagano M, Dowdy SF. Novel p27(kip1) c-terminal scatter domain mediates rac-dependent cell migration independent of cell cycle arrest functions. Mol Cell Biol (2003) 23:216–28. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.216-228.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Fujita N, Sato S, Katayama K, Tsuruo T. Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p27Kip1 promotes binding to 14-3-3 and cytoplasmic localization. J Biol Chem (2002) 277:28706–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203668200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sáez A, Sánchez E, Sánchez-Beato M, Cruz MA, Chacón I, Muñoz E, et al. p27KIP1 is abnormally expressed in diffuse Large b-cell lymphomas and is associated with an adverse clinical outcome. Br J Cancer (1999) 80:1427–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Sánchez-Beato M, Camacho FI, Martínez-Montero JC, Sáez AI, Villuendas R, Sánchez-Verde L, et al. Anomalous high p27/KIP1 expression in a subset of aggressive b-cell lymphomas is associated with cyclin D3 overexpression. p27/KIP1-cyclin D3 colocalization in tumor cells. Blood (1999) 94:765–72. doi: 10.1182/blood.V94.2.765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Vrhovac R, Delmer A, Tang R, Marie JP, Zittoun R, Ajchenbaum-Cymbalista F. Prognostic significance of the cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 in chronic b-cell lymphocytic leukemia. Blood (1998) 91:4694–700. doi: 10.1182/blood.V91.12.4694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kouvaraki M, Gorgoulis VG, Rassidakis GZ, Liodis P, Markopoulos C, Gogas J, et al. High expression levels of p27 correlate with lymph node status in a subset of advanced invasive breast carcinomas: relation to e-cadherin alterations, proliferative activity, and ploidy of the tumors. Cancer (2002) 94:2454–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Anayama T, Furihata M, Ishikawa T, Ohtsuki Y, Ogoshi S. Positive correlation between p27Kip1 expression and progression of human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer (1998) 79:439–43. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Watanabe J, Sato H, Kanai T, Kamata Y, Jobo T, Hata H, et al. Paradoxical expression of cell cycle inhibitor p27 in endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus - correlation with proliferation and clinicopathological parameters. Br J Cancer (2002) 87:81–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Shiozawa T, Shiohara S, Kanai M, Konishi I, Fujii S, Nikaido T. Expression of the cell cycle regulator p27(Kip1) in normal squamous epithelium, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, and invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. immunohistochemistry and functional aspects of p27(Kip1). Cancer (2001) 92:3005–11. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Dellas A, Schultheiss E, Leivas MR, Moch H, Torhorst J. Association of p27Kip1, cyclin e and c-myc expression with progression and prognosis in HPV-positive cervical neoplasms. Anticancer Res (1998) 18:3991–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Winters ZE, Leek RD, Bradburn MJ, Norbury CJ, Harris AL. Cytoplasmic p21WAF1/CIP1 expression is correlated with HER-2/ neu in breast cancer and is an independent predictor of prognosis. Breast Cancer Res (2003) 5:R242–9. doi: 10.1186/bcr654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Abbas T, Dutta A. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer (2009) 9:400–14. doi: 10.1038/nrc2657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Guo H, Lv Y, Tian T, Hu TH, Wang WJ, Sui X, et al. Downregulation of p57 accelerates the growth and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis (2011) 32:1897–904. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Guo S-X, Taki T, Ohnishi H, Piao H-Y, Tabuchi K, Bessho F, et al. Hypermethylation of p16 and p15 genes and RB protein expression in acute leukemia. Leukemia Res (2000) 24:39–46. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(99)00158-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Borriello A, Caldarelli I, Bencivenga D, Criscuolo M, Cucciolla V, Tramontano A, et al. p57(Kip2) and cancer: time for a critical appraisal. Mol Cancer Res (2011) 9:1269–84. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kavanagh E, Joseph B. The hallmarks of CDKN1C (p57, KIP2) in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta (2011) 1816:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Krug U, Ganser A, Koeffler HP. Tumor suppressor genes in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Oncogene (2002) 21:3475–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Sulong S, Moorman AV, Irving JAE, Strefford JC, Konn ZJ, Case MC, et al. A comprehensive analysis of the CDKN2A gene in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia reveals genomic deletion, copy number neutral loss of heterozygosity, and association with specific cytogenetic subgroups. Blood (2009) 113:100–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-166801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]