Abstract

Post-COVID condition is prevalent in 10–35% of cases in outpatient settings, however a stratification of the duration and severity of symptoms is still lacking, adding to the complexity and heterogeneity of the definition of post-COVID condition and its oucomes. In addition, the potential impacts of a longer duration of disease are not yet clear, along with which risk factors are associated with a chronification of symptoms beyond the initial 12 weeks. In this study, follow-up was conducted at 7 and 15 months after testing at the outpatient SARS-CoV-2 testing center of the Geneva University Hospitals. The chronification of symptoms was defined as the continuous presence of symptoms at each evaluation timepoint (7 and 15 months). Adjusted estimates of healthcare utilization, treatment, functional impairment and quality of life were calculated. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the associations between the chronification of symptoms and predictors. Overall 1383 participants were included, with a mean age of 44.3 years, standard deviation (SD) 13.4 years, 61.4% were women and 54.5% did not have any comorbidities. Out of SARS-CoV-2 positive participants (n = 767), 37.0% still had symptoms 7 months after their test of which 47.9% had a resolution of symptoms at the second follow-up (15 months after the infection), and 52.1% had persistent symptoms and were considered to have a chronification of their post-COVID condition. Individuals with a chronification of symptoms had an increased utilization of healthcare resources, more recourse to treatment, more functional impairment, and a poorer quality of life. Having several symptoms at testing and difficulty concentrating at 7 months were associated with a chronification of symptoms. COVID-19 patients develop post-COVID condition to varying degrees and duration. Individuals with a chronification of symptoms experience a long-term impact on their health status, functional capacity and quality of life, requiring a special attention, more involved care and early on identification considering the associated predictors.

Subject terms: SARS-CoV-2, Prognosis, Public health, Quality of life

Introduction

Post-COVID condition is increasingly recognized with symptoms that may persist several weeks1 to months2. The World Health Organization consensus definition describes post-COVID condition as symptoms persisting at least 3 months after the infection, after excluding other causes3. The prevalence of post-COVID condition varies between 10 and 35% of infected individuals4 and can reach up to 70% in patients post-hospitalization5. In a recent systematic review of 57 studies, post-covid condition manifested mostly through fatigue, pulmonary, neurologic and mental health long-term consequences6. Data are now emerging on the direct impact of COVID-19 on the brain among other organ systems. A recent study showed changes on the brain imaging of infected patients on average 141 days after their infection, mostly in the limbic system and correlated with a larger cognitive decline compared to SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals7. In a different study, brain structural changes were associated with functional modifications affecting different brain networks depending on whether the patients were aware of their deficits or not8. Another study suggested astrocytic impairment potentially underlying reported neurological post-COVID symptoms9, and brain tissue autopsies of SARS-CoV-2 infected non-human primates showed multiple evidence of neurologic damage including in animals that did not develop severe respiratory disease, potentially providing insight into the neurological manifestations of post-COVID condition10.

Without current treatment options, and as more evidence is gathered to explain the underlying pathophysiology, time and the natural evolution of symptoms accompanied by interdisciplinary care, rehabilitation and the management of daily activities remain the cornerstone of therapy11–13. While the prevalence of persistent symptoms decreases with time5,14–16, a subset of patients develop chronic symptoms that may impact them on the long-term. Thus, infected individuals could potentially be categorized into three groups: acute infection without post-COVID condition, acute infection with post-COVID condition, and acute infection with post-COVID condition and a chronification of symptoms. The latter group may experience increased functional impairment, with a debilitating tail of the pandemic that can last for years. This has been described after the 1918 influenza pandemic17, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 200318, and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 201219, among other viruses. In post-COVID condition, studies have already suggested an increased functional impairment in healthcare workers and in the general population related to the direct effects of the virus20,21. With chronic disability, patients may be sicker for a long time with a poorer quality of life, and require more healthcare resources and treatment22.

The subset of patients with a chronification of symptoms along with potential consequences have not been studied yet in post-COVID condition, focusing initially on the overall prevalence without a stratification of severity, duration and long-term impact. Additionally, some evidence suggests that female sex, the number of symptoms in the acute phase, age and body-mass index (BMI) are associated with post-COVID condition23,24. However, it is not yet clear which risk factors could be associated with a chronification of symptoms.

This study aims to describe and evaluate the evolution of symptoms at 7 and 15 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, in order to determine the proportion of individuals with a chronification of symptoms and their impact on functional capacity, quality of life, and healthcare utilization as well as any potential predictors, compared to the general population, to infected individuals with post-COVID condition without a chronification of symptoms and to infected individuals without post-COVID condition.

Methods

Participants and study setting

Individuals tested for SARS-CoV-2 by Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) at the outpatient center of the Geneva University Hospitals between October and December 2020 and who had an email address on file were contacted in July 2021 and January 2022 for follow-up. Inclusion criteria included a laboratory-confirmed test date at the Geneva University Hospitals, and being symptomatic at time of testing. Exclusion criteria included being asymptomatic at time of testing, having a positive test in between the laboratory confirmed test result at the Geneva University Hospitals and follow-up, or having a reinfection less than 7 months prior to follow-up.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All individuals gave consent and the study was approved by the Cantonal Research Ethics Commission of Geneva, Switzerland (protocol number 2021-00389). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data collection

Participants completed follow-up in July 2021 and January 2022. Follow-up included questions about self-rated health, symptoms at time of testing, evolution of symptoms since testing, persistent symptoms, symptoms intensity and frequency when present, functional capacity, productivity, quality of life, chronic treatment, and utilization of healthcare resources including hospitalizations, visits to the emergency room, visits to the primary care physician or other specialists. The follow-up survey instrument is presented in Supplement 1. Fatigue was assessed using the Chalder fatigue scale25 and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance scale26. Dyspnea was assessed using the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale27 and the Nijmegen questionnaire28. Insomnia was assessed using the insomnia severity index (ISI)29, anxiety and depression were assessed using the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HAD)30. All remaining symptoms were assessed using a Likert scale with self-reported options of mild, moderate or severe. Quality of life was assessed using the 12-item short form survey (SF-12) questionnaire31. Self-rated health was assessed using the first question of the 12-item short form survey “How would you rate your general state of health prior to testing” with answers (1) excellent, (2) very good, (3) good, (4) poor, (5) very poor. Answers were then combined into “good to excellent”, and “poor to very poor”. Functional capacity was assessed using the Sheehan disability scale32. The Sheehan disability scale is a five-item questionnaire. The first three items are each graded from 0 (no impairment), 1–3 (mild impairment), 4–6 (moderate impairment), 7–9 (marked impairment), to 10 (extreme impairment) evaluating functional impairment in three domains: professional, social and family life. Each domain can be assessed separately, and a global impairment rating is derived by adding the three scores. The remaining two items of the five-item questionnaire evaluate the number of days lost and days with reduced productivity due to functional impairment in the week preceding the questionnaire.

The chronification of symptoms was defined as the continuous presence of symptoms at each evaluation timepoint (7 and 15 months). Groups of participants were defined as: (1) infected individuals with post-COVID condition and a chronification of symptoms (individuals reporting symptoms since the infection with symptoms present at each follow-up), (2) infected individuals with post-COVID condition without a chronification of symptoms (individuals reporting having symptoms for more than 12 weeks after the infection with symptoms present at the first follow-up and no symptoms at the second follow-up), (3) infected individuals without post-COVID condition (individuals reporting symptoms lasting less than 12 weeks after the infection), and (4) SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals. The inclusion of SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals aimed to compare the differential impact of post-COVID condition with a chronification of symptoms to individuals who were not infected, by introducing a group of individuals who lived through similar pandemic conditions but did not get infected. The goal was to determine the direct effect of the infection, and potentially evaluate an increasing impact proportional to the effect of the infection versus no infection.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA v16.0. Descriptive analyses included percentages with comparisons using chi-square tests. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used for significance. Symptoms defining the presence of symptoms were any new symptom onset after SARS-CoV-2 infection including: fatigue, insomnia, headache, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, difficulty concentrating, paresthesia, loss or change in smell, loss or change in taste, generalized pain, myalgia, arthralgia, fever, cough, digestive symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain), and hair loss.

In order to determine the impact of the chronification of symptoms on individuals, estimates of healthcare utilization, treatment, functional impairment and quality of life were calculated and compared between the four defined groups. These estimates were adjusted for age, sex, physical activity, smoking status, vaccination status, hospitalization, self-rated health prior to testing, symptoms at testing and the following comorbidities: obesity or overweight, hypertension, diabetes, respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, headache disorders, cognitive disorders, sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, hypothyroidism, rheumatologic disease, anemia, chronic pain or fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome.

In order to determine potential predictors of the chronification of symptoms, the group of individuals with post-COVID condition without a chronification of symptoms was compared to the group of individuals with post-COVID condition with a chronification of symptoms. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the associations between the chronification of symptoms and the following predictors: age, sex, having several symptoms at time of testing, and symptoms at 7 months (fatigue, difficulty concentrating, headache, dizziness, insomnia, loss or change in smell, loss or change in taste, myalgia or arthralgia, or dyspnea). Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) were adjusted for age, sex, profession, civil status (single, married, widowed/separated or divorced), number of symptoms at time of testing, vaccination status, hospitalization, and pre-existing comorbidities (cognitive disorders, headaches, depression, anxiety), based on previous studies evaluating risk factors for the chronification of symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome33–35.

Results

Overall participants

Out of 3914 participants in July 2021, 2923 had consented to both follow-ups (response rate 74.7%) and 2048 completed both follow-ups fully. Out of the 2048 participants (44.8% with a positive test result, 55.2% with a negative test result), 392 had no symptoms at time of testing, and 1 preferred not to answer, both groups were excluded from this study. Out of the remaining participants, 177 had a positive test result between their documented RT-PCR and the second follow-up and 95 had a reinfection between their initial positive test result and the second follow-up; both groups were excluded from this study. Overall 1383 participants were included, 767 had a positive test result and 616 had a negative test result (Fig. 1). The mean age of participants was 44.3 years, standard deviation (SD) 13.4 years; 61.4% were women and 54.5% did not have any comorbidities. In comparison, individuals who did not participate were 55.3% women, mean age was 41.3 years (SD 13.8); 46.2% had a SARS-CoV-2 positive test, 9.4% were hospitalized and 48.9% did not have any comorbidities. Further characteristics are shown in Table 1, stratification by group of participants is presented in Supplement 2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart with 1383 participants included out of 2923 who had a follow-up at 7 and 15 months. Out of the 1383 participants, 767 were SARS-CoV-2 positive and 616 were SARS-CoV-2 negative.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants (n = 1383).

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age categories | |

| Below 40 years | 554 (40.1) |

| 40–59 years | 653 (47.2) |

| 60 years and above | 176 (12.7) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 534 (38.6) |

| Female | 849 (61.4) |

| Education | |

| Primary | 39 (2.8) |

| Apprenticeship | 158 (11.4) |

| Secondary | 174 (12.6) |

| Tertiary | 932 (67.4) |

| Other | 61 (4.4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 19 (1.4) |

| RT-PCR test result | |

| Negative | 616 (44.5) |

| Positive | 767 (55.5) |

| Civil status | |

| Single | 265 (20.7) |

| In couple, not married | 334 (26.1) |

| Married or registered partnership | 528 (41.2) |

| Divorced or separated | 130 (10.1) |

| Widowed | 15 (1.2) |

| Other | 10 (0.8) |

| Living situation | |

| Alone | 265 (20.7) |

| Single parent with children | 94 (7.3) |

| In couple, without children | 325 (25.4) |

| In couple, with children | 474 (37) |

| Cohabitation | 123 (9.6) |

| Work status | |

| Salaried | 909 (71.0) |

| Retired | 105 (8.2) |

| Student or in training | 93 (7.3) |

| Independent worker | 64 (.05) |

| Homemaker | 33 (2.6) |

| Unemployed | 40 (3.1) |

| Disability | 12 (0.9) |

| Other | 24 (1.9) |

| Work situation | |

| Fixed term contract | 114 (11.1) |

| Open-ended long term contract | 817 (79.7) |

| Subsidized | 3 (0.3) |

| Training | 26 (2.5) |

| Other | 65 (6.3) |

| Profession | |

| Unskilled workers | 48 (3.5) |

| Skilled workers | 238 (17.2) |

| Highly skilled workers | 323 (23.4) |

| Professional-managers | 438 (31.7) |

| Other | 206 (14.9) |

| Prefer not to answer | 20 (1.5) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never smoked | 741 (53.6) |

| Current smoker | 207 (15.0) |

| Ex-smoker, stopped independently of COVID-19 | 400 (28.9) |

| Ex-smoker, stopped because of COVID-19 infection | 9 (0.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 26 (1.9) |

| Physical activity | |

| No physical activity | 195 (14.1) |

| Partial physical activity | 711 (51.4) |

| Complete physical activity | 469 (33.9) |

| Prefer not to answer | 8 (0.6) |

| Body-mass index | |

| Less than 18.5 kg/m2 | 38 (3.1) |

| Between 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 724 (58.7) |

| Between 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 351 (28.4) |

| Between 30–34.9 kg/m2 | 93 (7.5) |

| Between 35 and 40 kg/m2 | 28 (2.3) |

| Symptoms at testing | |

| Pauci-symptomatic | 461 (33.3) |

| Several symptoms | 922 (66.7) |

| Vaccination status | |

| No vaccination | 183 (13.2) |

| 1 dose | 215 (15.5) |

| 2 doses | 455 (32.9) |

| 3 doses | 524 (37.9) |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 (0.4) |

| Hospitalization | 90 (6.5) |

| Comorbidities | |

| None | 755 (54.6) |

| Obesity or overweight | 275 (19.9) |

| Hypertension | 144 (10.4) |

| Diabetes | 26 (1.9) |

| Respiratory disease | 74 (5.4) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 40 (2.9) |

| Headache disordersa | 230 (16.6) |

| Cognitive disordersb | 117 (8.5) |

| Sleep disorders | 249 (18.0) |

| Depression | 116 (8.4) |

| Anxiety | 149 (10.8) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 12 (0.9) |

| Hypothyroidism | 49 (3.5) |

| Anemia | 63 (4.6) |

| Thromboembolic disease | 16 (1.2) |

| Dysmenorrhea | 18 (1.3) |

| Fibromyalgia or chronic pain | 35 (2.5) |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | 99 (7.2) |

| Rheumatologic disordersc | 186 (13.4) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 98 (7.1) |

aHeadache disorders include migraine, tension headaches, and other types of headaches.

bCognitive disorders include memory and attention deficit.

cRheumatologic disorders include tendinitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis.

Symptoms at 7 and 15 months

Out of SARS-CoV-2 positive participants (n = 767), 63.0% (n = 483) had no symptoms 7 months after their test (first follow-up median time 208 days, interquartile range IQR 194–221), and 37.0% (n = 284) still had symptoms 7 months after their test and were considered to have post-COVID condition. Out of individuals with post-COVID condition, 47.9% (n = 136) had a resolution of symptoms at the second follow-up (15 months after the infection), and 52.1% (n = 148) had persistent symptoms and were considered to have a chronification of their post-COVID condition. The most common remaining symptoms at 15 months were fatigue, difficulty concentrating, headache, insomnia, loss or change in smell, loss or change in taste, myalgia, arthralgia, and dyspnea.

Utilitzation of resources and treatment

Individuals with a chronification of symptoms had an increased utilization of healthcare resources since their test date (62.2% at 15 months), when compared to infected individuals with post-COVID without chronification of symptoms (43.6%), infected individuals without post-COVID (27.9%), and SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals (31.6%), with details presented in Fig. 2. The increased utilization of resources included visits to the emergency room, visits to the primary care physician and visits to specialists. Individuals with a chronification of symptoms had more recourse to treatment overall (10.0% reported no treatment at all since their test date) compared to infected individuals with post-COVID without a chronification of symptoms (13.3% without any treatment), infected individuals without post-COVID (21.4% without any treatment), and SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals (12.6% without any treatment). SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals had a higher usage of anti-depressants and anxiolytics when compared to the other groups. More details on treatment consumption are presented in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Adjusted frequency estimates of utilization of healthcare resources since test date, stratified by SARS-CoV-2 infection and duration of symptoms, including infected individuals without post-COVID condition, with post-COVID condition without a chronification of symptoms and with a chronification of symptoms (n = 1383). Healthcare utilization was defined as the presence of any of the visits to the primary care physician, the emergency room or other specialists since the test date. Chronification of symptoms was defined as the continuous persistence of symptoms, present at 7 and 15 months of follow-up. Symptoms defining the persistence of symptoms were any new symptom onset after SARS-CoV-2 infection including: fatigue, insomnia, headache, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, difficulty concentrating, paresthesia, loss or change in smell, loss or change in taste, generalized pain, myalgia, arthralgia, fever, cough, digestive symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain), and hair loss. Estimates were adjusted for age, sex, physical activity, smoking status, vaccination status, hospitalization, self-rated health prior to testing, symptoms at testing and the following comorbidities: obesity or overweight, hypertension, diabetes, respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, headache disorders, cognitive disorders, sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, hypothyroidism, rheumatologic disease, anemia, chronic pain or fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Table 2.

Adjusted frequency estimates of treatment, functional impairment and quality of life in SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals with and without chronification of symptoms, and SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals (n = 1383).

| Negative (n = 616) | Positive without post-COVID symptoms (n = 483) | Positive with post-COVID symptoms without chronification of symptoms (n = 136) | Positive with chronification of symptoms (n = 148) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95%) | % (95%) | % (95%) | % (95%) | ||

| Treatment since testing | |||||

| None | 12.6 (11.9–13.4) | 21.4 (20.2–22.5) | 13.3 (11.7–14.9) | 10.0 (8.8–11.2) | < 0.001 |

| Paracetamol | 67.7 (66.7–68.8) | 60.8 (59.5–62.1) | 73.4 (71.3–75.4) | 72.3 (70.2–74.5) | < 0.001 |

| Anti-inflammatories | 46.6 (45.5–47.7) | 35.5 (34.3–36.7) | 41.4 (39.2–43.5) | 39.4 (37.3–41.4) | < 0.001 |

| Aspirin | 8.2 (7.8–8.7) | 7.8 (7.3–8.4) | 8.1 (7.2–9.0) | 8.2 (7.1–9.4) | 0.007 |

| Inhaled sprays | 9.6 (8.4–10.8) | 5.3 (4.4–6.2) | 8.6 (6.4–10.9) | 10.5 (8.0–13.0) | < 0.001 |

| Systemic steroids | 3.0 (2.7–3.3) | 3.6 (3.1–4.0) | 3.8 (3.0–4.6) | 6.1 (5.1–7.0) | < 0.001 |

| Anticoagulation | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) | 2.7 (2.2–3.2) | 2.0 (1.5–2.6) | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 0.011 |

| Antidepressants | 11.2 (9.7–12.6) | 4.3 (3.2–5.3) | 6.4 (3.9–8.8) | 8.3 (5.9–10.7) | < 0.001 |

| Sleeping medication | 5.2 (4.4–6.1) | 1.9 (1.3–2.4) | 9.7 (6.9–12.5) | 6.9 (5.1–8.7) | < 0.001 |

| Anxiolytics | 8.3 (7.2–9.3) | 4.1 (3.3–4.8) | 6.9 (4.9–8.9) | 4.5 (3.3–5.7) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin D | 27.4 (26.5–28.4) | 21.2 (20.4–21.9) | 34.3 (32.0–36.5) | 38.0 (35.9–40.0) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin C | 19.4 (18.8–20.0) | 16.4 (15.9–16.9) | 30.3 (28.9–31.7) | 26.6 (25.4–27.9) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin B12 | 11.6 (11.2–12.1) | 9.5 (9.2–9.9) | 18.3 (17.1–19.5) | 14.3 (13.3–15.2) | < 0.001 |

| Zinc | 12.4 (11.9–13.0) | 12.1 (11.6–12.6) | 17.6 (16.3–18.9) | 18.1 (16.7–19.4) | < 0.001 |

| Other treatment | 5.9 (5.6–6.3) | 5.1 (4.7–5.4) | 5.2 (4.6–5.8) | 6.8 (6.1–7.6) | < 0.001 |

| Physical therapy | 23.7 (22.6–24.8) | 16.2 (15.4–17.1) | 17.3 (15.3–19.2) | 24.0 (22.3–25.8) | < 0.001 |

| Impact at 15 months | |||||

| Functional impairmenta | 12.5 (11.8–13.2) | 5.0 (4.6–5.3) | 43.7 (41.2–46.2) | 95.6 (95.2–96.0) | < 0.001 |

| 1 or more days lost or with reduced productivity in the past week | 23.6 (22.7–24.5) | 23.8 (22.9–24.7) | 16.8 (15.5–18.2) | 46.9 (44.7–49.2) | < 0.001 |

| Quality of lifeb | |||||

| Physical health score | 51.0 (50.7–51.2) | 52.7 (52.5–52.9) | 51.9 (51.5–52.3) | 46.1 (45.7–46.5) | < 0.001 |

| Mental health score | 40.7 (40.5–40.8) | 41.9 (41.7–42.0) | 39.7 (39.3–40.0) | 40.2 (39.9–40.5) | < 0.001 |

Estimates were adjusted for age, sex, physical activity, smoking status, vaccination status, hospitalization, self-rated health prior to testing, symptoms at time of testing and the following comorbidities: obesity or overweight, hypertension, diabetes, respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, headache disorders, cognitive disorders, sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, hypothyroidism, rheumatologic disease, anemia, chronic pain or fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome.

aFunctional impairment was calculated using the Sheehan disability scale32.

bQuality of life was assessed using the SF-12 scale31.

Functional impairment and quality of life

Individuals with a chronification of symptoms had consistently more functional impairment at each follow-up (93.0% at 15 months), compared to individuals with post-COVID condition without a chronification of symptoms who had an improvement in functional capacity between the first and second follow-up and individuals without post-COVID condition who did not report functional impairment (Fig. 2). They also had an increased frequency of days lost or with reduced productivity at work (46.9% compared to 16.8% in post-COVID individuals without a chronification of symptoms, 23.8% in SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals without post-COVID condition and 23.6% in SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals). Details are presented in Table 2. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals with a chronification of symptoms had a poorer quality of life evidenced by lower physical health scores on the SF-12 scale (mean 46.1 in group 1, compared to 51.9 in post-COVID individuals without a chronification of symptoms, 52.7 in SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals without post-COVID condition, 51.0 in SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals). The mental health scores on the SF-12 scale were low across all four groups.

Predictors of chronification

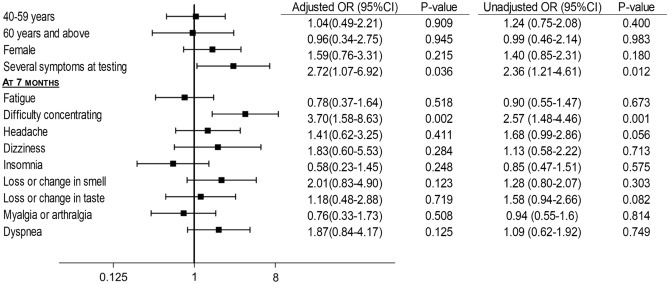

When comparing individuals with post-COVID condition without chronification to individuals with post-COVID condition with chronification, results showed an independent association between having difficulty concentrating at 7 months and the chronification of symptoms (aOR 3.70; 1.58–8.63). The chronification of symptoms was also associated with having several symptoms at time of testing (aOR 2.72; 1.07–6.92), and was not associated with age, sex, or any other symptom at 7 months (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Associations between predictors and chronification of symptoms in SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals with post-COVID condition (n = 284). Individuals who had symptoms at 7 months and no symptoms at 15 months were considered to have post-COVID condition without chronification. Individuals with symptoms at 7 months and 15 months were considered to have post-COVID condition with chronification. Symptoms defining the presence of symptoms were any new symptom onset after SARS-CoV-2 infection including: fatigue, insomnia, headache, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, difficulty concentrating, paresthesia, loss or change in smell, loss or change in taste, generalized pain, myalgia, arthralgia, fever, cough, digestive symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain), and hair loss. Odds ratios were adjusted for age, sex, profession, civil status (single, married, widowed/separated or divorced), symptoms at time of testing, number of symptoms at 7 months, nature of symptom at 7 months (fatigue, difficulty concentrating, headache, dizziness, loss or change in smell, loss or change in taste, insomnia, myalgia, arthralgia, dyspnea), vaccination status, hospitalization, and pre-existing comorbidities (cognitive disorders, headaches, depression, anxiety.

Discussion

Post-COVID symptoms improve in almost 50% of individuals with post-COVID condition between 7 and 15 months after testing. Yet, the chronification of symptoms defined as the continuous presence of symptoms at each follow-up and beyond 12 months after the infection is prevalent in 19.3% (148/767) of infected individuals. The chronification of symptoms is predicted by neurologic symptoms and leads to an increased utilization of healthcare resources, as well as functional impairment.

A stratification of post-COVID condition, taking into account the nature and duration of post-COVID symptoms is important in addressing this condition, as all patients may not require the same treatment or management. The chronification of symptoms largely increases the utilization of healthcare resources, including visits to the emergency room and outpatient visits, as well as the need for more chronic treatment. The increased utilization of healthcare resources and treatment options remains significant after adjusting for sociodemographic variables and comorbidities. Of note, SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals had a higher use of anti-depressants and anxiolytics when compared to the other groups. One hypothesis is that people with more anxiety or depression might have opted to stay home or be less socially active during the pandemic thus decreasing their risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection36,37. The increased use of healthcare resources and treatment potentially leads to compounded individual and public health effects due to the chronification of symptoms.

The impact of the chronification of symptoms on individuals and on society is manifested by an increased functional impairment, more days lost or with reduced productivity at work. These results show that a proportion of individuals will suffer from debilitating effects, long after their infection. Individuals with a chronification of symptoms also suffer from a poorer quality of life. While mental health scores were overall low in all study groups compared to the average of 50 in the general population31, the physical health scores were markedly lower in the group of individuals with a chronification of symptoms, indicating potential physical limitations in their everyday life. While awaiting for potential treatment options, patients with potential risk factors of chronification should be identified and managed early in order to potentially reduce the impact on daily life as much as possible.

Risk factors for the chronification of symptoms may include having several symptoms at time of testing and the presence of cognitive symptoms evidenced by a difficulty concentrating. A recent study described the longitudinal evolution of symptoms over 12 months and suggested neurologic symptoms such as paresthesia might increase with time16. This is in line with our hypothesis that the chronification of symptoms may be driven by a neurological process. In comparison, risk factors for other chronic conditions similar to post-COVID have been reported such as age, sex, education levels, depression or anxiety found to be associated with an increased risk of chronic fatigue syndrome33–35,38. However, these studies have shown contradictory results showing an association with lower income34, but also with middle-high income leading to more diagnosis38. Studies also showed an association of chronic fatigue syndrome with younger33, and older age35. These factors were not associated with a chronification of symptoms in our study. Also comparatively, patients with post-COVID condition after hospitalization might exhibit more respiratory symptoms6, which was not as evident in our study. To date, the definition of post-COVID condition includes both outpatient and inpatient settings however the manifestation of disease might be different and so could the predicting factors.

The underlying mechanisms of post-COVID are not yet understood. Four hypotheses remain at the forefront of explanations of post-COVID condition including viral persistence, dysbiosis39, an autoimmune response40 or a dysregulated inflammatory response39,41. Studies have shown that inflammatory markers are elevated in post-COVID individuals42, autoantibodies during the acute phase could be correlated with long-term symptoms, and smaller studies have detected persistent viral particles on gastrointestinal biopsies43,44. In addition to learning about the mechanisms of post-COVID condition, it is paramount to understand the mechanisms leading to a chronification of symptoms. Comparatively, the chronification of symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome shows that immune dysregulation or a low-level chronic inflammation might be potential contributors45.

Limitations include ascertainment bias in online follow-ups based on a survey format, as well as including only laboratory-confirmed results. This was a decision based on the importance to objectively differentiate SARS-CoV-2 from other viruses or diseases as much as possible, however could potentially miss taking into account false negative results46 or individuals who did not have timely access to testing. In addition, the chronification of symptoms is a newly defined concept that was elaborated specifically in this study context, to be validated by further studies. Similarly, reports of cognitive signs and disorders did not include a validated questionnaire which would have required an in-person assessment. Including a validated questionnaire would better define cognitive symptoms in addition to the ones used for fatigue, dyspnea and sleep disorders. Finally, more women participated in the study raising the issue of the generalizability. Age and sex were adjusted for in the regression models and frequency estimates.

In conclusion, this study shows that COVID-19 patients develop post-COVID condition to varying degrees and durations, and a subset of individuals might have a chronification of their symptoms, potentially predicted by neurologic manifestations, and with a long-term impact including poor quality of life, increased functional impairment and an increased utilization of healthcare resources. The risks of the chronification of symptoms and functional impairment should be assessed early on, taking into account identified predictors and providing specific and more involved care for these individuals to mitigate long-term consequences.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

M.N., O.B., F.C. and I.G. contributed to the conceptualisation of the study. M.N. contribued to data collection. M.N. and I.G. contributed to the formal analysis and validation of results. I.G. supervised the work. All authors including the CoviCare study team contributed to the protocol. All authors including the CoviCare study team reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Private Foundation of the Geneva University Hospitals, Leenaards foundation.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Mayssam Nehme, Email: Mayssam.nehme@hcuge.ch.

CoviCare Study Team:

Mayssam Nehme, Olivia Braillard, Pauline Vetter, Delphine S. Courvoisier, Frederic Assal, Frederic Lador, Lamyae Benzakour, Matteo Coen, Ivan Guerreiro, Gilles Allali, Christophe Graf, Jean-Luc Reny, Silvia Stringhini, Hervé Spechbach, Frederique Jacquerioz, Julien Salamun, Guido Bondolfi, Dina Zekry, Paola M. Soccal, Riccardo Favale, Stéphane Genevay, Kim Lauper, Philippe Meyer, Nana Kwabena Poku, Agathe Py, Basile N. Landis, Thomas Agoritsas, Marwène Grira, José Sandoval, Julien Ehrsam, Simon Regard, Camille Genecand, Aglaé Tardin, Laurent Kaiser, François Chappuis, and Idris Guessous

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-18673-z.

References

- 1.Nehme M, Braillard O, Alcoba G, Aebischer Perone S, Courvoisier D, Chappuis F, Guessous I. COVID-19 symptoms: Longitudinal evolution and persistence in outpatient settings. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-5926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, McDonald D, Magedson A, Wolf CR, Chu HY. Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(2):e210830. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. A clinical case defintion of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Last updated October 6, (2021) https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/345824/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post-COVID-19-condition-Clinical-case-definition-2021.1-eng.pdf (Accessed 10 Oct 2021).

- 4.Pavli A, Theodoridou M, Maltezou HC. Post-COVID syndrome: Incidence, clinical spectrum, and challenges for primary healthcare professionals. Arch. Med. Res. 2021;52(6):575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, Wang Q, Ren L, Wang Y, Hu P, Guo L, Liu M, Xu J, Zhang X, Qu Y, Fan Y, Li X, Li C, Yu T, Xia J, Wei M, Chen L, Li Y, Xiao F, Liu D, Wang J, Wang X, Cao B. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398(10302):747–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo AE, Ba DM, Parsons N, Poudel GR, Lekoubou A, Oh JS, Ericson JE, Ssentongo P, Chinchilli VM. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(10):e2128568. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douaud G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voruz P, Cionca A, Jacot de Alcântara I, Nuber-Champier A, Allali G, Benzakour L, Thomasson M, Lalive PH, Lövblad KO, Braillard O, Nehme M, Coen M, Serratrice J, Pugin J, Guessous I, Landis BN, Adler D, Griffa A, Van De Ville D, Assal F, Péron JA. Functional connectivity underlying cognitive and psychiatric symptoms in post-COVID-19 syndrome: Is anosognosia a key determinant? Brain Commun. 2022;4(2):057. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcac057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang AC, Kern F, Losada PM, Agam MR, Maat CA, Schmartz GP, Fehlmann T, Stein JA, Schaum N, Lee DP, Calcuttawala K, Vest RT, Berdnik D, Lu N, Hahn O, Gate D, McNerney MW, Channappa D, Cobos I, Ludwig N, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Keller A, Wyss-Coray T. Dysregulation of brain and choroid plexus cell types in severe COVID-19. Nature. 2021;595(7868):565–571. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03710-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutkai I, Mayer MG, Hellmers LM, Ning B, Huang Z, Monjure CJ, Coyne C, Silvestri R, Golden N, Hensley K, Chandler K, Lehmicke G, Bix GJ, Maness NJ, Russell-Lodrigue K, Hu TY, Roy CJ, Blair RV, Bohm R, Doyle-Meyers LA, Rappaport J, Fischer T. Neuropathology and virus in brain of SARS-CoV-2 infected non-human primates. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):1745. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29440-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basu D, Chavda VP, Mehta AA. Therapeutics for COVID-19 and post COVID-19 complications: An update. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2022;3:100086. doi: 10.1016/j.crphar.2022.100086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nopp S, Moik F, Klok FA, Gattinger D, Petrovic M, Vonbank K, Koczulla AR, Ay C, Zwick RH. Outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with long COVID improves exercise capacity, functional status, dyspnea, fatigue, and quality of life. Respiration. 2022 doi: 10.1159/000522118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, Kang L, Guo L, Liu M, Zhou X, Luo J, Huang Z, Tu S, Zhao Y, Chen L, Xu D, Li Y, Li C, Peng L, Li Y, Xie W, Cui D, Shang L, Fan G, Xu J, Wang G, Wang Y, Zhong J, Wang C, Wang J, Zhang D, Cao B. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397(10270):220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nehme M, Braillard O, Chappuis F, Courvoisier DS, Guessous I. Prevalence of symptoms more than seven months after diagnosis of symptomatic COVID-19 in an outpatient setting. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021 doi: 10.7326/M21-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran VT, Porcher R, Pane I, Ravaud P. Course of post COVID-19 disease symptoms over time in the ComPaRe long COVID prospective e-cohort. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):1812. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29513-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spinney L. Pandemics disable people—The history lesson that policymakers ignore. Nature. 2022;602(7897):383–385. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-00414-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tansey CM, Louie M, Loeb M, Gold WL, Muller MP, de Jager J, Cameron JI, Tomlinson G, Mazzulli T, Walmsley SL, Rachlis AR, Mederski BD, Silverman M, Shainhouse Z, Ephtimios IE, Avendano M, Downey J, Styra R, Yamamura D, Gerson M, Stanbrook MB, Marras TK, Phillips EJ, Zamel N, Richardson SE, Slutsky AS, Herridge MS. One-year outcomes and health care utilization in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167(12):1312–1320. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SH, Shin HS, Park HY, et al. Depression as a mediator of chronic fatigue and post-traumatic stress symptoms in middle east respiratory syndrome survivors. Psychiatry Investig. 2019;16(1):59–64. doi: 10.30773/pi.2018.10.22.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Havervall S, Rosell A, Phillipson M, Mangsbo SM, Nilsson P, Hober S, Thålin C. Symptoms and functional impairment assessed 8 months after mild COVID-19 among health care workers. JAMA. 2021;325(19):2015–2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nehme M, Braillard O, Chappuis F, Courvoisier D, Kaiser L, Guessous I, CoviCare Study Team 1-year persistent symptoms and functional impairment in SARS-CoV-2 positive and negative individuals. J. Intern. Med. 2022 doi: 10.1111/joim.13482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moynihan R, Sanders S, Michaleff ZA, Scott AM, Clark J, To EJ, Jones M, Kitchener E, Fox M, Johansson M, Lang E, Duggan A, Scott I, Albarqouni L. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e045343. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bechmann N, Barthel A, Schedl A, Herzig S, Varga Z, Gebhard C, Mayr M, Hantel C, Beuschlein F, Wolfrum C, Perakakis N, Poston L, Andoniadou CL, Siow R, Gainetdinov RR, Dotan A, Shoenfeld Y, Mingrone G, Bornstein SR. Sexual dimorphism in COVID-19: Potential clinical and public health implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(3):221–230. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00346-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freire APCF, Lira FS, Morano AEVA, Pereira T, Coelho-E-Silva MJ, Caseiro A, Christofaro DGD, Marchioto Júnior O, Dorneles GP, Minuzzi LG, Pinho RA, Silva BSA. Role of body mass and physical activity in autonomic function modulation on post-COVID-19 condition: An observational subanalysis of fit-COVID study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19(4):2457. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, Wallace EP. Development of a fatigue scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 1993;37(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buccheri G, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M. Karnofsky and ECOG performance status scoring in lung cancer: A prospective, longitudinal study of 536 patients from a single institution. Eur. J. Cancer. 1996;32A(7):1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahler DA, Wells CK. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest. 1988;93(3):580–586. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.3.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Dixhoorn J, Duivenvoorden HJ. Efficacy of Nijmegen Questionnaire in recognition of the hyperventilation syndrome. J. Psychosom. Res. 1985;29(2):199–206. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 1997;27(2):93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galland-Decker C, Marques-Vidal P, Vollenweider P. Prevalence and factors associated with fatigue in the Lausanne middle-aged population: A population-based, cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e027070. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lacerda EM, Geraghty K, Kingdon CC, Palla L, Nacul L. A logistic regression analysis of risk factors in ME/CFS pathogenesis. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):275. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1468-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stevelink SAM, Fear NT, Hotopf M, Chalder T. Factors associated with work status in chronic fatigue syndrome. Occup. Med. 2019;69(6):453–458. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqz108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan VS, Dominitz JA, Eastment MC, et al. Risk factors for testing positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in a National United States Healthcare System. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;73(9):e3085–e3094. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark C, Davila A, Regis M, Kraus S. Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: An international investigation. Glob. Transit. 2020;2:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.glt.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solomon L, Reeves WC. Factors influencing the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004;164(20):2241–2245. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merad M, Blish CA, Sallusto F, Iwasaki A. The immunology and immunopathology of COVID-19. Science. 2022;375(6585):1122–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.abm8108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cervia C, Zurbuchen Y, Taeschler P, Ballouz T, Menges D, Hasler S, Adamo S, Raeber ME, Bächli E, Rudiger A, Stüssi-Helbling M, Huber LC, Nilsson J, Held U, Puhan MA, Boyman O. Immunoglobulin signature predicts risk of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):446. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27797-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maamar M, Artime A, Pariente E, Fierro P, Ruiz Y, Gutiérrez S, Tobalina M, Díaz-Salazar S, Ramos C, Olmos JM, Hernández JL. Post-COVID-19 syndrome, low-grade inflammation and inflammatory markers: A cross-sectional study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2022 doi: 10.1080/03007995.2022.2042991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phetsouphanh C, Darley DR, Wilson DB, Howe A, Munier CML, Patel SK, Juno JA, Burrell LM, Kent SJ, Dore GJ, Kelleher AD, Matthews GV. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2022;23(2):210–216. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lehmann M, Allers K, Heldt C, Meinhardt J, Schmidt F, Rodriguez-Sillke Y, Kunkel D, Schumann M, Böttcher C, Stahl-Hennig C, Elezkurtaj S, Bojarski C, Radbruch H, Corman VM, Schneider T, Loddenkemper C, Moos V, Weidinger C, Kühl AA, Siegmund B. Human small intestinal infection by SARS-CoV-2 is characterized by a mucosal infiltration with activated CD8+ T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2021;14(6):1381–1392. doi: 10.1038/s41385-021-00437-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arostegui D, Castro K, Schwarz S, Vaidy K, Rabinowitz S, Wallach T. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein presence in the intestinal epithelium of a pediatric patient 3 months after acute infection. JPGN Rep. 2022;3(1):e152. doi: 10.1097/PG9.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bansal AS, Bradley AS, Bishop KN, Kiani-Alikhan S, Ford B. Chronic fatigue syndrome, the immune system and viral infection. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012;26:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Z, Bi Q, Fang S, Wei L, Wang X, He J, Wu Y, Liu X, Gao W, Zhang R, Gong W, Su Q, Azman AS, Lessler J, Zou X. Insight into the practical performance of RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 using serological data: A cohort study. Lancet Microb. 2021;2(2):e79–e87. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30200-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.