Abstract

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has been used to probe, under physiological conditions, the surface ultrastructure and molecular interactions of spores of the filamentous fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. High-resolution images revealed that the surface of dormant spores was uniformly covered with rodlets having a periodicity of 10 ± 1 nm, which is in agreement with earlier freeze-etching measurements. In contrast, germinating spores had a very smooth surface partially covered with rough granular structures. Force-distance curve measurements demonstrated that the changes in spore surface ultrastructure during germination are correlated with profound modifications of molecular interactions: while dormant spores showed no adhesion with the AFM probe, germinating spores exhibited strong adhesion forces, of 9 ± 2 nN magnitude. These forces are attributed to polysaccharide binding and suggested to be responsible for spore aggregation. This study represents the first direct characterization of the surface ultrastructure and molecular interactions of living fungal spores at the nanometer scale and offers new prospects for mapping microbial cell surface properties under native conditions.

Spores have great importance in the life cycle of fungi, since they are means of vegetative multiplication, dispersal, and survival (1, 30). The surface of spores of many fungi, including ascomycetes, basidiomycetes, and zygomycetes, is covered by a thin layer of regularly arranged rodlets (1, 6, 9, 13, 24, 32). These structures, 5 to 10 nm thick and up to 250 nm in length, are composed mainly of proteins (31), while hyphal walls are essentially composed of polysaccharides, such as glucans and chitin. Germination results in the disruption of the rodlet layer (13).

Understanding spore adhesion (10), spore aggregation (8), and spore dispersal (1) requires knowledge of the structure and physicochemical properties of the spore surface at supramolecular scale. The ultrastructure of fungal spores has been investigated by transmission electron microscopy combined with freeze-fracture and surface replica techniques for over 3 decades (1, 2, 11, 27, 28); however, direct information on the native spore surface was inaccessible. On the other hand, methods used so far to measure interaction forces at biological interfaces, including the osmotic stress method (18), the surface-force apparatus (19), and the micropipette technique (7, 20), did not offer lateral resolution.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) (3) has proved useful to investigate the morphology of biological surfaces (4, 12, 14, 23) and to measure interaction forces between complementary biomolecules (17, 33). In particular, well-ordered arrangements of isolated bacterial surface proteins have been visualized at high spatial resolution (15, 21, 22, 25, 29). However, the application of AFM to direct probing of the surface ultrastructure of living microbial cells down to the nanometer scale has not been reported. In this study, we used AFM to determine, in situ, the ultrastructure and molecular interactions at the surface of living spores of Phanerochaete chrysosporium and their changes during germination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Conidiospores of P. chrysosporium INA-12 (strain I-398 in the Collection Nationale de Culture de Microorganismes, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) were collected from mycelial mats and grown in agitated liquid medium for 8.5 h at 37°C, as described earlier (8). They were washed twice by resuspension in deionized water (Milli-Q; Millipore) and centrifugation and resuspended in water. The pH of the spore suspension was about 6.5. Spores were immobilized by mechanical trapping in an Isopore polycarbonate membrane (Millipore) with a pore size similar to the spore size (16). After filtering of a spore suspension (10 ml; 106 cells per ml), the filter was carefully cut (1 by 1 cm) and attached to a steel sample puck (Digital Instruments, Santa Barbara, Calif.) by using a small piece of adhesive tape, and the mounted sample was transferred into the AFM liquid cell. AFM measurements were made at room temperature (20°C), under water, by using an optical lever microscope (Nanoscope III; Digital Instruments), applied force maintained below 1 nN, a scan rate of ∼2 Hz, and oxide-sharpened microfabricated Si3N4 cantilevers (Park Scientific Instruments, Mountain View, Calif.) with a spring constant of 0.03 N/m and a probe curvature radius of typically 20 nm (according to manufacturer specifications). Images were recorded in both height and deflection modes. In height mode, the local height variations are measured while the probe-sample interaction force is kept constant; in deflection mode, the deflection of the cantilever is measured while the probe scans at a constant height. While height images provide quantitative information on sample surface topography, deflection images often exhibit higher contrast of the morphological details.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

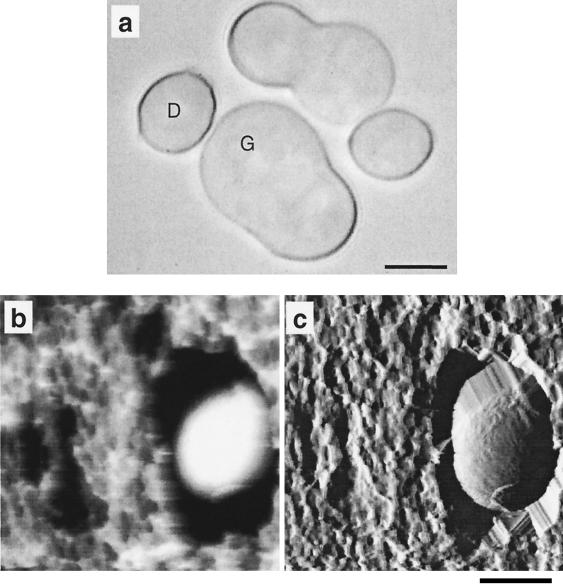

Figure 1a shows an optical micrograph of spores after 8.5 h of incubation in liquid medium. While dormant spores are spherical particles about 5 μm in diameter, germinating spores have a swollen part which is the starting point of the germ tube.

FIG. 1.

(a) Optical micrograph of P. chrysosporium spores observed after 8.5 h of incubation in agitated liquid medium. Scale bar = 5 μm. While dormant spores (D) are spherical particles, germinating spores are swollen and allow identification of a germinating zone (G). (b and c) AFM images of a dormant spore recorded, under water, in two different modes: height image (b) and deflection image (c). Scale bar = 5 μm; z range = 2 μm (b) and 1 μm (c).

To investigate spores under native conditions by AFM, we achieved cell immobilization by mechanical trapping in porous membranes. Low-resolution AFM images of a dormant spore are shown in Fig. 1b and c. While the height image (Fig. 1b) provides quantitative topographic information, the deflection image (Fig. 1c) reveals fine surface details (12). At imaging forces lower than 1 nN, images of the same area were obtained repeatedly without detaching the spores or altering the surface morphology. In the deflection image (Fig. 1c), the spore is surrounded by artifactual structures resulting from the contact between the AFM probe and the edges of the spore and of the pore.

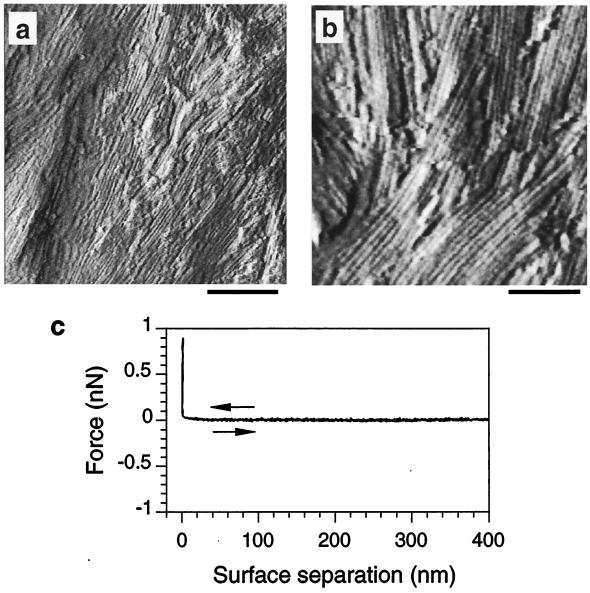

High-resolution images of dormant spores showed that the surface was uniformly covered with a regular pattern of rodlets (Fig. 2a and b). These structures were several hundred nanometers in length and had a periodicity of 10 ± 1 nm, in excellent agreement with earlier freeze-etching characterization (9). Images obtained by forward and backward scanning were identical, indicating no significant contribution of lateral forces to the apparent topographic contrast. Changing the scanning angle by 90° resulted in the rotation of the rodlet orientation accordingly, demonstrating that the observed patterns are due to real surface relief.

FIG. 2.

(a and b) Deflection images showing rodlet structures at the surface of dormant spores at two different magnifications. Scale bars = 250 nm (a) and 125 nm (b); z range = 15 nm (a) and 20 nm (b). (c) Force-distance curve recorded, under water, between the surface of a dormant spore and the silicon nitride AFM probe. Similar results were obtained with at least 1,000 force-distance curves recorded in different regions of the spore. The data shown are representative of results obtained with more than 10 spores, by using different probes and independent preparations.

A force-versus-distance curve recorded between the silicon nitride probe and the surface of a dormant spore is shown in Fig. 2c. Upon approach, no significant deviation from linearity was seen in the contact region, indicating that the sample was not deformed by the probe. Upon retraction, no adhesion forces were detected, reflecting the absence of molecular interactions between probe and surface. 32 × 32 force-distance curves recorded on 1- by 1-μm areas all showed the same features, indicating that the spore surface was homogeneous as regards physicochemical properties.

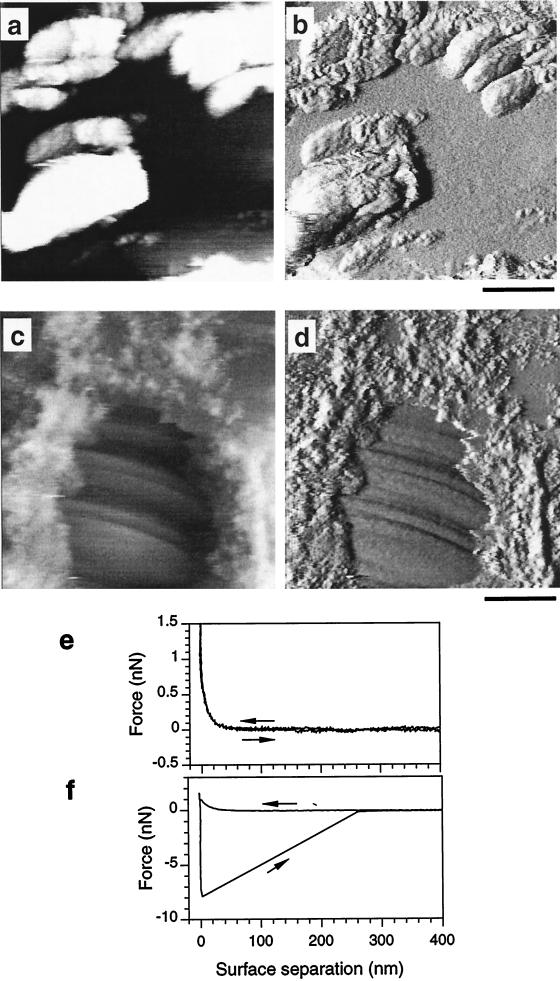

The ultrastructure of germinating spores was clearly different from that of dormant spores. AFM images (Fig. 3a to d) revealed that part of the surface was coated with rough granular material (rms roughness on 250- by 250-nm areas of height images = 3.4 ± 1.2 nm), apparently resulting from the fragmentation of the rodlet layer, while the underlying surface was very smooth (rms roughness = 0.4 ± 0.1 nm) and showed ring-like structures (Fig. 3c and d). Images recorded on the germinating zone (Fig. 1a) were uniformly smooth, while those obtained on other zones showed that the rough material represented a high surface fraction. The change in cell surface ultrastructure is consistent with earlier electron microscopy observations of the same spores: a rodlet layer was detected at the surface of dormant spores, while the wall of germinating spores became fragmented and residual rodlets were disseminated on the new spore surface (9). In the same way, dormant sporangiospores of Syncephalastrum racemosum had a regular pattern of rodlets at their surface (13); during germination, these rodlets were displaced, revealing a very smooth germ tube. The granular material is thus attributed to residues of loosely bound rodlets, while smooth zones with rings would reflect the new cell wall material.

FIG. 3.

(a to d) AFM images showing the heterogeneous surface ultrastructure of a germinating spore. Images were recorded in the height (a and c) and deflection (b and d) modes. Scale bars = 250 nm (a and b) and 500 nm (c and d); z range = 100 nm (a and c), 50 nm (b), and 25 nm (d). (e and f) Force-distance curves recorded on the granular (e) and on the smooth (f) material. The same features were found in at least 1,000 force-distance curves recorded on the two different zones. Similar results were obtained with more than 10 spores, by using different probes and independent preparations; small variations in the absolute values of the adhesion force (f) were observed.

Force-distance curve measurements demonstrated that the changes in spore surface ultrastructure during germination went along with profound modifications of the physicochemical properties (Fig. 3e and f). In contrast with dormant spores, germinating spores revealed a curvature upon approach, reflecting sample softness and/or repulsive surface forces. These might be due to electrostatic interactions; however, silicon nitride surfaces were shown to be close to electrical neutrality over a wide pH range (pH 6 to 8.5) (26). The heterogeneous surface morphology of germinating spores was directly correlated with differences in adhesion forces revealed by retraction curves: no adhesion forces were measured between the probe and the granular material (Fig. 3e), while strong adhesion forces, of 9 ± 2 nN (n = 50) magnitude, were measured on smooth zones (Fig. 3f).

These results represent the first direct (i.e., under physiological conditions) characterization of the surface ultrastructure and molecular interactions of living fungal spores at the nanometer scale. They demonstrate that dramatic changes in cell surface ultrastructure and physicochemical properties occur during germination of P. chrysosporium spores and provide direct indications as to the functions of fungal surfaces. It has been suggested that rodlet layers play a role in spore dissemination and protection against lytic enzymes (1, 5). Our finding that rodlet layers at the surface of dormant spores of P. chrysosporium are rigid and endowed with nonadhesive properties points to their role as protection and dispersal structures. Polysaccharides at the germ tube surface have been proposed to mediate spore aggregation (6, 13). For P. chrysosporium, an increase in the surface polysaccharide concentration during germination was demonstrated by surface analysis with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and suggested to be involved in spore aggregation (8). The observation of strong adhesion forces on the smooth zones of germinating spores may thus be attributed to the presence of polysaccharides and provides evidence for their role in the aggregation process. Molecular interactions could be investigated further by using chemically modified probes.

The approach presented here offers promise as an application for the nanoscale characterization of the surface properties of prokaryotic, animal, and plant cells in the native state. In particular, probes functionalized with relevant chemical functions or biochemical moieties (33) could be used to map the distribution of specific cell surface components. This would provide new insight into the molecular mechanisms of biointerfacial phenomena such as cell aggregation, cell adhesion, molecular recognition, and intercellular communication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The support of the National Foundation for Scientific Research (FNRS), of the Foundation for Training in Industrial and Agricultural Research (FRIA), and of the Federal Office for Scientific, Technical and Cultural Affairs (Interuniversity Poles of Attraction Programme) is gratefully acknowledged.

We thank P. Grange for the use of the atomic force microscope and K. Lee for programming associated with the force measurements.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beever R E, Dempsey G P. Function of rodlets on the surface of fungal spores. Nature. 1978;272:608–610. doi: 10.1038/272608a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beveridge T J, Graham L L. Surface layers of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:684–705. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.684-705.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binnig G, Quate C F, Gerber C. Atomic force microscope. Phys Rev Lett. 1986;56:930–933. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.56.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butt H-J, Wolff E K, Gould S A C, Dixon Northern B, Peterson C M, Hansma P K. Imaging cells with the atomic force microscope. J Struct Biol. 1990;105:54–61. doi: 10.1016/1047-8477(90)90098-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claverie-Martin F, Diaz-Torres M R, Geoghegan M J. Chemical composition and electron microscopy of the rodlet layer of Aspergillus nidulans conidiospores. Curr Microbiol. 1986;14:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dute R R, Weete J D, Rushing A E. Ultrastructure of dormant and germinating conidia of Aspergillus ochraceus. Mycologia. 1989;81:772–782. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans E A. Analysis of adhesion of large vesicles to surfaces. Biophys J. 1980;31:425–432. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)85069-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerin P A, Dufrene Y, Bellon-Fontaine M-N, Asther M, Rouxhet P G. Surface properties of the conidiospores of Phanerochaete chrysosporium and their relevance to pellet formation. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5135–5144. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5135-5144.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerin P A, Asther M, Sleytr U B, Rouxhet P G. Detection of rodlets in the outer wall region of conidiospores of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:412–416. doi: 10.1139/m94-068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamer J E, Howard R J, Chumley F G, Valent B. A mechanism for surface attachment in spores of a plant pathogenic fungus. Science. 1988;239:288–290. doi: 10.1126/science.239.4837.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handley P S. Negative staining. In: Mozes N, Handley P S, Busscher H J, Rouxhet P G, editors. Microbial cell surface analysis: structural and physicochemical methods. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers; 1991. pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson E, Haydon P G, Sakaguchi D S. Actin filament dynamics in living glial cells imaged by atomic force microscopy. Science. 1992;257:1944–1946. doi: 10.1126/science.1411511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hobot J A, Gull K. Changes in the organisation of surface rodlets during germination of Syncephalastrum racemosum. Protoplasma. 1981;107:339–343. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoh J H, Lal R, John S A, Revel J-P, Arnsdorf M F. Atomic force microscopy and dissection of gap junctions. Science. 1991;253:1405–1408. doi: 10.1126/science.1910206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karrasch S, Hegerl R, Hoh J, Baumeister W, Engel A. Atomic force microscopy produces faithful high-resolution images of protein surfaces in an aqueous environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:836–838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasas S, Ikai A. A method for anchoring round shaped cells for atomic force microscope imaging. Biophys J. 1995;68:1678–1680. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee G U, Chrisey L A, Colton R J. Direct measurement of the forces between complementary strands of DNA. Science. 1994;266:771–773. doi: 10.1126/science.7973628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeNeveu D M, Rand R P, Parsegian V A. Measurement of forces between lecithin bilayers. Nature. 1976;259:601–603. doi: 10.1038/259601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marra J, Israelachvili J. Direct measurements of forces between phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine bilayers in aqueous electrolyte solutions. Biochemistry. 1985;24:4608–4618. doi: 10.1021/bi00338a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merkel R, Nassoy P, Leung A, Ritchie K, Evans E. Energy landscapes of receptor-ligand bonds explored with dynamic force spectroscopy. Nature. 1999;397:50–53. doi: 10.1038/16219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohnesorge F, Heckl W M, Häberle W, Pum D, Sára M, Schindler H, Schilcher K, Kiener A, Smith D P E, Sleytr U B, Binnig G. Scanning force microscopy studies of the S-layers from Bacillus coagulans E38-66, Bacillus sphaericus CCM2177 and of an antibody binding process. Ultramicroscopy. 1992;42–44:1236–1242. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(92)90429-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pum D, Sleytr U B. Molecular nanotechnology and biomimetics with S-layers. In: Sleytr U B, Messner P, Pum D, Sára M, editors. Crystalline bacterial cell surface proteins. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes; 1996. pp. 175–209. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radmacher M, Tillmann R W, Fritz M, Gaub H E. From molecules to cells: imaging soft samples with the atomic force microscope. Science. 1992;257:1900–1905. doi: 10.1126/science.1411505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sassen M M A, Remsen C C, Hess W M. Fine structure of Penicillium megasporum conidiospores. Protoplasma. 1967;64:75–87. doi: 10.1007/BF01257383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schabert F A, Henn C, Engel A. Native Escherichia coli OmpF porin surfaces probed by atomic force microscopy. Science. 1995;268:92–94. doi: 10.1126/science.7701347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Senden T J, Drummond C J. Surface chemistry and tip-sample interactions in atomic force microscopy. Colloids Surf A. 1995;94:29–51. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sleytr U B. Heterologous reattachment of regular arrays of glycoproteins on bacterial surfaces. Nature. 1975;257:400–402. doi: 10.1038/257400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sleytr U B, Messner P, Pum D. Analysis of crystalline bacterial surface layers by freeze-etching, metal shadowing, negative staining and ultrathin sectioning. Methods Microbiol. 1988;20:29–60. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Southam G, Firtel M, Blackford B L, Jericho M H, Xu W, Mulhern P J, Beveridge T J. Transmission electron microscopy, scanning tunneling microscopy, and atomic force microscopy of the cell envelope layers of the archaeobacterium Methanospirillum hungatei GP1. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1946–1955. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.1946-1955.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wessels J G H. Fruiting in the higher fungi. Adv Microb Physiol. 1993;34:147–202. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wessels J G H. Hydrophobins: proteins that change the nature of the fungal surface. Adv Microb Physiol. 1997;38:1–45. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wessels J G H, Kreger D R, Marchant R, Regensburg B A, de Vries O M H. Chemical and morphological characterization of the hyphal wall surface of the basidiomycete Schizophyllum commune. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;273:346–358. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(72)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong S S, Joselevich E, Woolley A T, Cheung C L, Lieber C M. Covalently functionalized nanotubes as nanometre-sized probes in chemistry and biology. Nature. 1998;394:52–55. doi: 10.1038/27873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]