Abstract

A toll-free statement alerting consumers how to report side effects to FDA is required for both prescription drug labeling and direct-to-consumer (DTC) print ads. Due to different regulatory requirements between these materials (TFNR vs. FDAAA, respectively), the wording of this statement differs. We studied how statement wording for reporting side effects to FDA in DTC television ads affects comprehension of product risks and benefits, comprehension of and memory for the toll-free statement, and perceived statement clarity. Participants viewed one of eight mock prescription drug television ads that varied the wording and placement of the toll-free statement, and then responded to a questionnaire. The FDAAA statement was more noticeable, clear, and more participants were able to recall and recognize its correct purpose. Comprehension of product risk and benefit information did not differ based on statement wording. Findings suggest that the FDAAA toll-free statement wording is superior to that of the TFNR.

Keywords: DTC, prescription drugs, advertisements, toll-free statement, Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act

Introduction

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Medical Products Reporting Program (MedWatch), created in 1993, functions as a mechanism through which FDA disseminates safety information and a portal through which adverse events for FDA-regulated human medical products can be reported directly to the Agency. Initially designed to increase voluntary reporting from healthcare professionals (1), this mechanism has also provided a way for consumers and patients to report adverse events directly to FDA. Congress passed legislation in 2002 designed to make this mechanism visible and available to consumers. The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA; Public Law 107–109) and subsequent regulations (2) require most human drug product labels to include (a) a toll-free number maintained by FDA to receive reports of adverse events, and (b) a statement that the number should be used for reporting purposes only, not to receive medical advice. The BPCA did not mandate particular wording for this statement, so FDA conducted two focus groups with consumers to determine the best wording of this statement. The findings from that research elicited the following statement wording: “Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to FDA at 1–800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.” This language was subsequently tested in a labeling comprehension study and codified in the Toll-free Number for Reporting Adverse Events on Labeling for Human Drug Products Rule (TFNR; 3).

The TFNR is limited to product labeling. A separate law, the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA), specifically addressed the inclusion of this reporting availability in prescription drug direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising. Title IX of FDAAA requires printed DTC advertisements (ads) for prescription drug products to include the following statement: “You are encouraged to report negative side effects of prescription drugs to the FDA. Visit www.fda.gov/medwatch, or call 1–800-FDA-1088.” The specific wording was mandated in the law. Title IX also required that a study be conducted to determine (a) if this “toll-free statement” is appropriate for inclusion in DTC television ads for prescription drug products, or if its presence would interfere with viewers’ comprehension of risk information in the ads; and (b) if it is appropriate, the length of time the statement should be displayed in the ads.

The wording of toll-free statement for reporting side effects differs as a function of the specific law under which it falls, despite being intended for the same purpose. Prescription drug labeling requires the TFNR statement. Prescription drug consumer-directed print advertising (and, potentially TV advertising) requires the FDAAA statement. The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of wording differences of the toll-free statement between the TFNR language and the FDAAA language when presented in DTC prescription drug TV ads. Based on prior consumer testing, we hypothesized that the TFNR statement would result in higher recall, comprehension, and ratings of clarity than the FDAAA statement. We are not aware of any consumer testing of the FDAAA statement.

Materials and Methods

The study reported here was part of a larger study which had a sample of 4,961 adults drawn from Knowledge Network’s (now GfK) KnowledgePanel®, a nationally representative o-nline panel. This panel consists of individuals aged 13 or older who have been recruited through a combination of random-digit-dialing and address-based sampling, and the study was restricted to noninstitutionalized adults aged 18 or older with an oversample of respondents with diagnosed high blood pressure (HBP). We oversampled respondents with HBP in order to test for differences between this population and the general population, given that the ad used in this study offered treatment for HBP. To qualify, participants had to consent to participate in the experiment, be able to and actually view the streaming video ads, and recall that they saw the study ad. From the larger study, 3,295 adults participated in this part of the study. See Table 1 for participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics.

| Category | Weighted percentage |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 7.8% |

| 25–34 | 16.8% |

| 35–44 | 22.9% |

| 45–54 | 19.3% |

| 55–64 | 16.2% |

| 65 or older | 17.1% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 69.7% |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 11.5% |

| Hispanic | 13.3% |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 5.5% |

| Gender | |

| Male | 48.7% |

| Female | 51.3% |

| Education | |

| Less than high school graduate | 6.8% |

| High school graduate | 37.0% |

| Some college | 28.4% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 27.8% |

| Diagnosed with high blood pressure | |

| Currently taking prescription high blood pressure drug | 28.2% |

| Yes | 24.6% |

| No | 75.0% |

| Refused | 0.4% |

Note. Unweighted N = 3,295.

Study Design

We examined the wording of the statement and its placement in the ad relative to the major statement of risks. Statement wording was defined by which toll-free statement respondents saw, either the FDAAA statement or the TFNR statement:

FDAAA: “You are encouraged to report negative side effects of prescription drugs to the FDA. Visit www.fda.gov/medwatch, or call 1-800-FDA-1088.”

TFNR: “Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects. You may report side effects to FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.”

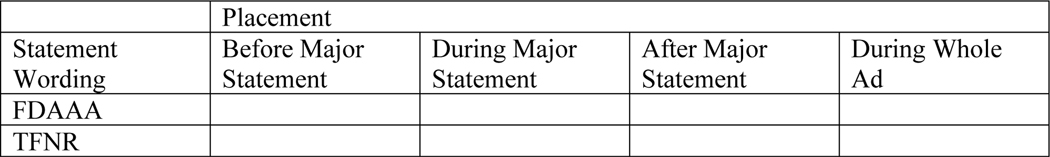

The statement was presented on-screen as superimposed text (super) for either 10 seconds before, during, or after the major statement, or for the duration of the whole ad. This resulted in a 2 (statement wording: FDAAA, TFNR) by 4 (placement: before, during, after, whole ad) fully crossed design (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Study Design

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to view one version of an ad for a fictional HBP drug, Zintria, within a group of four ads in the following order: iTunes (15 seconds), Nasonex (30 seconds), Tide (15 seconds), and Zintria. To reduce effects that might result from the novelty of the toll-free statement, the Nasonex ad also included the FDAAA toll-free statement matched to the test condition with which it was paired (e.g., 3-second duration after the major statement in both ads). Participants then responded to a series of questions about the ad (described below). At the conclusion of the study, participants were informed that Zintria was not a real prescription drug.

Study Measures

Comprehension of risk and benefit information.

We asked participants 20 true/false questions (e.g., “If you have a very slow heart rate, you should not take Zintria”) and 5 multiple-choice questions (e.g., “Why should you not stop taking Zintria suddenly?”). We created separate risk and benefit indices from these items. We assigned participants “+1” for each risk or benefit statement identified correctly as being included/not included in the ad and for each correct multiple-choice response. The range for the risk index was 0 to 11 and the range for the benefit index was 0 to 9.

Perceived product benefit and risk.

We measured perceived benefit with two closed-ended 7-point Likert questions (e.g., “How well do you think Zintria would or would not work for you?”; 1 = not at all well, 7 = extremely well). Similarly, we measured perceived risk of the product with two closed-ended, 7-point Likert questions (e.g., “How safe or not safe do you think Zintria is?”; 1 = not at all safe, 7 = extremely safe). These items did not reach a threshold of Cronbach’s alpha ≥ .80 (Bland and Altman 1997) when combined for either measure (benefit: Cronbach’s alpha = .64; risk: Cronbach’s alpha = .78) and thus we analyzed them separately.

Memory and comprehension of the toll-free statement.

We asked participants three closed-ended questions: whether the ad listed any websites, whether the ad listed any phone numbers, and whether they noticed a statement in the ad about FDA. We asked participants who reported noticing a statement about FDA two additional questions: what the statement said (open-ended) and why you should contact FDA according to the statement (closed-ended). We asked participants who did not remember a statement about FDA if they remembered a statement about reporting side effects. Finally, we showed all participants six statements and asked them to select which appeared in the ad. Wording of and correct responses to each of these questions appear in Table 2.

Table 2.

Weighted mean (95% confidence interval) of participants’ risk/benefit comprehension and memory for the toll-free statement, by statement type

| Statement type | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Dependent variable (response) | FDAAA | TFNR |

| Comprehension of benefits (0–9) | 4.5 (4.4, 4.7) | 4.7 (4.5, 4.8) |

| Comprehension of risks (0–11) | 5.2 (5.0, 5.4) | 5.5 (5.2, 5.7) |

| How well do you think Zintria would or would not work? (1 = not at all, 7 = extremely) | 2.5 (2.4, 2.6) | 2.6 (2.5, 2.7) |

| How likely or not likely would you be to lower your blood pressure if you took Zintria? (1 = not at all, 7 = extremely) | 3.9 (3.6, 3.9) | 3.9 (3.8, 4.0) |

| How safe or not safe do you think Zintria is? (1 = not at all, 7 = extremely) | 3.3 (3.3, 3.4) | 3.4 (3.3, 3.5) |

| How risky or not risky do you think Zintria is? (1 = extremely, 7 = not at all) | 3.4 (3.3, 3.5) | 3.5 (3.4, 3.6) |

| Did the ad list any web sites? (% Yes) | 43.3 (39.7, 47.0) | 39.7 (36.3, 43.2) |

| Did the ad list any telephone numbers? (% Yes) | 39.6 (36.0, 43.2) | 35.7 (32.4, 39.2) |

| Did you notice a statement about FDA in the ad for Zintria? (% Yes) | 49.8 (46.1, 53.4) | 40.5* (37.0, 44.1) |

| What did the statement say?1 (% Open-ended responses coded as “to report side effects” or “call FDA”) | 30.5 (26.1, 35.2) | 11.3* (8.4, 15.1) |

| Why should you contact FDA, according to the statement?1 (% Selected “to report side effects”) | 50.2 (45.2, 55.3) | 30.7* (25.9, 36.0) |

| Did you notice a statement about reporting side effects?2 (% Yes) | 71.3 (66.2, 76.0) | 71.0 (66.6, 75.0) |

| Which, if any, of the following appeared in the ad? (% Selected the toll-free statement) | 44.4 (40.9, 48.1) | 49.2 (45.6, 52.9) |

| Statement clarity (% extremely understandable/not at all confusing/extremely clear) | 65.0 (61.4, 68.5) | 48.0* (44.3, 51.6) |

Note.

significantly different at p < .05.

These questions were asked only of participants who responded “yes” when asked whether they noticed a statement about FDA in the ad.

This question was asked only of participants who responded “no” when asked whether they noticed a statement about FDA in the ad.

Clarity of the toll-free statement.

After completing the toll-free memory and comprehension questions, we showed all participants the same toll-free statement they saw in the ad and asked three closed-ended questions to assess perceived statement clarity: “How understandable is this statement?” (1 = not at all understandable, 7 = extremely understandable), “How confusing is this statement?” (1 = extremely confusing, 7 = not at all confusing), and “How clear is this statement?” (1 = not at all clear, 7 = extremely clear) (Cronbach’s alpha = .89). Because the distribution of responses was highly skewed (more than 60% of participants indicated “7” for all three questions), we converted this scale to a binary measure in which we assigned a code of “1” for all participants who indicated “Extremely understandable,” “Not at all confusing,” and “Extremely clear” to each respective question. With the exception of 27 observations for which no summary variable was calculated because of missing data (due to participants not answering a question), we coded all other response patterns as a “0.”

Analyses

We used weighted data in our analyses to account for nonresponse, noncoverage, underrepresentation of minority groups, and other types of sampling and survey error. Because there were few differences between the HBP and non-HBP participants, the results presented here reflect estimates from the population-weighted data representing the general population, including both HBP participants and non-HBP participants. We performed bivariate analyses to test for significant differences between statement wording conditions. Results of the placement variable are reported elsewhere. We report weighted estimates with 95% confidence intervals and significance level determined by Student’s t-tests. In addition, multivariate analyses were performed using gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, HBP status, and HBP medication use as covariates. Because the multivariate analyses provided similar conclusions as the bivariate analyses, we report only the results from the bivariate analyses.

Results

Comprehension of Product Risks and Benefits

Statement wording did not affect participants’ comprehension of the product’s risks or benefits (all ps > 0.10).

Perceived Product Benefit and Risk

Statement wording did not affect participants’ ratings of Zintria’s likeliness to work, likeliness to lower blood pressure, safety, or riskiness (all ps > .10).

Memory and Comprehension of Statement

There was a main effect of statement wording for noticing a statement about FDA. Participants in the FDAAA group (49.8%) noticed a statement about FDA significantly more often than participants in the TFNR group (40.5%), t(1, 3294) = 3.54, p < .001. Among participants who noticed the statement about FDA, more participants in the FDAAA group (30.5%) correctly remembered (open-ended) that the FDA statement recommended reporting side effects or calling FDA, compared with the TFNR group (11.3%), t(1, 1510) = 6.63, p < .001. More participants who saw the FDAAA statement (50.2%) correctly recognized (multiple choice) that the reason to call FDA is “to report side effects,” compared with participants who saw the TFNR statement (30.7%), t(1, 1508) = 5.33, p < .001.

Statement wording did not affect memory of telephone numbers or web sites in the ad or participants’ ability to select the toll-free statement from among other statements. Among participants who did not notice a statement about FDA, memory for a statement about reporting side effects did not differ by statement wording (all ps > 0.05).

Clarity of Toll-Free Statement

More participants rated the FDAAA statement as higher in clarity (65%) compared to participants who saw the TFNR statement (48%), t(1, 3294) = 7.35, p < .001.

Discussion

This study examined differences in wording of the toll-free statement presented in a DTC ad. We focused on 1) comprehension of the risk and benefit information detailed in the ad, 2) the ability to remember the presence and content of the toll-free statement, and 3) an adequate understanding of the toll-free statement (i.e., that the statement encourages consumers to contact the FDA to report side effects).

We did not find any differences in comprehension of the product risks or benefits as a function of statement wording. Thus, the wording does not appear to affect participants’ processing of the product information in the ad. This is reassuring because, from a public health perspective, it would be detrimental to add information that would distract consumers from important risk and benefit information about the product. Note that both statements were presented as stationary superimposed text and did not include motion, music, or other potentially distracting elements.

In terms of which toll-free statement to use, the FDAAA toll-free statement appears superior to the TFNR statement in terms of noticeability, effectiveness, and clarity. More participants in the FDAAA group noticed a statement about FDA, more correctly remembered the purpose of the statement, and the FDAAA statement was rated higher in clarity compared to the TFNR statement. This is surprising because the TFNR statement was developed through extensive testing with consumers and the FDAAA statement was not. The results may be a function of the purpose of each statement. When crafting the TFNR statement, a major concern was that consumers would mistakenly think that they should use the number to report side effects to FDA in lieu of getting medical help (2). Therefore, the statement begins “Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects.” Subsequent testing of the TFNR statement showed this concern was unfounded; consumers reported they understood the purpose of the toll-free number when it included the preamble about medical advice and were able to distinguish between serious and less serious side effects (2). This suggests consumers do not confuse the FDA number with one they should call for medical help with side effects. Although the current study did not specifically address the issue of confusion over whom to call for medical help, it is possible the location of the TFNR statement on prescription drug labels, including packaging, evokes a different analysis than the toll-free statement in a prescription drug ad. Further examination of the two statements in the context of drug packaging received from the pharmacist would clarify whether the context makes these concerns more relevant.

A notable limitation of our research concerns repetition of the FDAAA statement exclusively in the FDAAA statement condition. Participants in this condition saw the statement once during the Nasonex ad and again during the Zintria ad, whereas participants in the TFNR statement condition saw the FDAAA statement during the Nasonex ad and the TFNR statement during the Zintria ad. We incorporated the FDAAA statement into the Nasonex ad for both conditions to control for novelty of the statement content; specifically, we sought to ensure that participants did not inappropriately assume that there was something unique about the risks of Zintria that required such a statement. In hindsight, we recognize that our approach may have reinforced memory (through repetition) for those in the FDAAA statement condition. To bolster experimental control, we should have instead incorporated the TFNR statement into the Nasonex ad for participants exposed to the TFNR statement in the Zintria ad. We advise that researchers conducting similar research follow this more controlled approach.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the wording of the toll-free statement proposed in FDAAA is higher in clarity and more noticeable than the wording proposed in the TFNR. This research supports the current use of the FDAAA wording in print ads and the adoption of the FDAAA wording in television ads. The findings also suggest that other researchers may want to further examine the wording of the labeling statement to explore its effectiveness. Nonetheless, the TFNR statement appears on labeling pieces that are usually accessed by consumers after they have been prescribed the drug. Thus, the needs for particular types of information may differ in these contexts. Overall, the FDAAA statement appears appropriate in situations where consumers are likely to scan quickly (print ads) or view an externally-paced video (television ads).

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Office of Prescription Drug Promotion, Food and Drug Administration and was provided an exemption from FDA’s Research Involving Human Subjects Committee.

Footnotes

Note that use of brand name products in this study does not imply endorsement by FDA.

References

- 1.Code of Federal Regulations (2014a), 21 CFR 310.305 (drugs); 21 CFR 600.80 (biologics); 21 CFR 803 (devices). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food and Drug Administration (2007). Toll-Free Number for Reporting Adverse Events on Labeling for Human Drug Products; Labeling Comprehension Study. 72 FR, 5056–5057. Available at http://www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2003-N-0313-0009. Last accessed May 7, 2015.

- 3.Food and Drug Administration (2008), “Toll-Free Number for Reporting Adverse Events on Labeling for Human Drug Products: Final Rule,” 73 FR 209, 63886–63987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]