Abstract

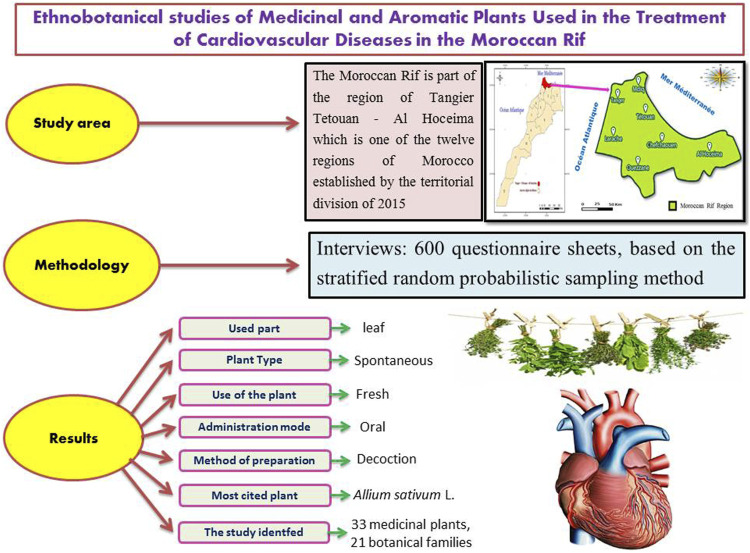

Background: Since the dawn of time, Moroccans have used medicinal plants as a popular remedy to treat a wide range of human and cattle health issues. Nonetheless, very little research has been conducted in the past to record and disseminate indigenous ethnopharmacological knowledge adequately. This study was conducted in the Rif and attempted to identify medicinal plants used by indigenous people to treat cardiovascular problems and the ethnomedicinal knowledge linked with them.

Methods: The ethnobotanical study was carried out in the Moroccan Rif area over 2 years, from 2016 to 2018. We questioned 520 traditional herbalists and consumers of these herbs in total. The gathered data were examined and contrasted using quantitative ethnobotanical indicators such as family importance value (FIV), the relative frequency of citation (RFC), plant part value (PPV), fidelity level (FL), and informant consensus factor (ICF).

Results: The findings analysis revealed the presence of 33 plant species classified into 20 families, with the Poaceae dominating (7 species). Regarding disorders treated, the category of cardiac arrhythmias has the greatest ICF (0.98). The study discovered that the leaves were the most often utilized portion of the plants (PPV = 0.353) and that the most frequently used preparation was a decoction (31%).

Conclusions: The current study’s findings revealed the presence of indigenous ethnomedicinal knowledge of medicinal plants in the Moroccan Rif to treat cardiovascular illnesses. Further phytochemical, pharmacological, and toxicological investigations should be conducted to identify novel drugs from these documented medicinal plants.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, herbal medicine, ethnobotany, ethnomedicine, medicinal and aromatic plant

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1 Introduction

Cardiovascular disorder (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality globally (Muna, 1993; Lopez et al., 2006; Strong et al., 2006). CVD encompasses many problems, including cardiac muscle diseases and the vascular system that supplies the heart, brain, and other essential organs. Humans have long utilized medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) to cure and combat illness. Traces of its usage may be found in all ancient civilizations and continents. Thus, despite advances in pharmacology, the medicinal use of plants is still prevalent in certain countries, particularly in impoverished nations (Gurib-Fakim, 2009).

In recent decades, plants have become essential sources of both preventative and therapeutic traditional medicinal preparations for humans and animals. Plants are also significant in global business nowadays (Zhang, 1998). In the lack of an excellent medical system, the demand for medicinal plants increases daily in underdeveloped and industrialized countries (World Health Organization, 2001).

Due to its relief and biogeographical location, Moroccan Rif has a vibrant ecological, and floristic diversity, becoming a natural plant genetic reserve (Benabid & Bellakhdar, 1987; Bellakhdar, 1997; Chaachouay et al., 2019a). This biodiversity is characterized by considerable floristic endemism, which allows the Rif to occupy a privileged place among the Mediterranean regions with a long medical tradition and traditional know-how based on medicinal and aromatic plants. Indeed, herbal medicine has long played an important role in Moroccan medical practices, and the Rif area is a prime example (Chaachouay et al., 2019b; Chaachouay et al., 2020a).

This investigation aimed to examine medicinal plants growing in the study region to add to indigenous knowledge about MAPs and to analyze the data about existing associations between medicinal species and cardiovascular disorders. Indeed, it is critical to turn this traditional knowledge into scientific knowledge to revalue, maintain, and utilize it properly.

2 Methods

2.1 Description of the study area

The study was conducted in the Rif (northern Morocco). Its northern latitude ranges from 34° to 36°, while its eastern longitude ranges from 4° to 6°. It is bounded to the north by the Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean Sea; to the south by the Rabat-Sale-Kenitra and Fez-Meknes regions; to the east by the Eastern Region the west by the Atlantic Ocean (Figure 1). The general geographical area of the Rif is 11,570 km2, and the city’s population is around 3 549 512 inhabitants, with a population density rate of 222.2/km2 (HCP, 2018).

FIGURE 1.

Map of the study area.

The study region has a Mediterranean climate, with the most significant temperature surpassing 45°C during summer (July-August) and below 0°C during winter (December-January). At the same time, the average annual precipitation varies from 700 to 1,300 mm, falling mainly between October and February (DMNM, 2018). It is mountainous, with heights varying from 145 to 2.456 m above sea level (Jbel Tidirhine). This area is dominated by species such as Cedrus atlantica (Endl.), Quercus suber L, Quercus ilex L, Quercus canariensis Willd, Abies marocana Trab, Pinus halepensis Mill., Juniperus oxycedrus L, Ceratonia siliqua L, and Pistacia atlantica Desf. Rif people rely heavily on subsistence farming, cattle, and, to a lesser extent, forest reserves for a living (Benabid & Bellakhdar, 1987; Chaachouay et al., 2019c).

2.2 Methodology

2.2.1 Data collection

From 30 June 2016, to 1 June 2018, an ethnomedical study was conducted to gather information on plant species used to treat cardiovascular illnesses in the Rif. Semi-structured interviews, open-ended questions, group discussions, free listing, and notes and recordings using a digital voice recorder were used to gather data (Cotton & Wilkie, 1996; Klotoé et al., 2013). Five hundred twenty respondents between the ages of 17 and 81 were selected randomly for conversations (cautery installers, farmers, elders, bonesetters, herbalists, and therapists) in the study region. Following a stratified random sampling procedure, samples were created in each of the 28 strata, including seven urban communes, and then combined to form the total sample of 520 informants (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of survey points at the study area level.

The number of respondents varies according to the availability of medicinal plants desired in each stratum (Figure 2). Each interview lasted around 20 min to an hour. The interviewee’s profile (age, sex, educational status, monthly salary, family status, and location) and ethnomedicinal statistics for each plant gathered include the common local name, the route of administration, the preparation methods, the dosage, the part used, the condition of the plant used, and the diseases treated Appendix A. The inhabitants of the Rif speak Amazigh or Arabic dialects, and interviews are performed in these languages. All documentation has since been translated into English.

2.2.2 Medicinal plants identification and preservation

We documented the collection of plant materials, then dehydrated, positioned, processed, and conserved plant components (Jain, 1964). Specimens were identified, gathered, dried, compressed, poisoned, and placed on standard herbarium sheets for identification based on ethnomedicinal knowledge supplied by our interviewees. The plants were classified systematically according to their common name, scientific name, family, the plant parts utilized, production method, relative abundance, and geographical distribution. This plant species indicated by the informants were taxonomically identified using local flora available, such as “The medicinal plants of Morocco” (Sijelmassi, 1993), and “Practical flora of Morocco” (Fennane et al., 1998, 1999, 2014), and “Catalog of vascular plants of north Morocco tomes I and II” (Valdés, 2002). Finally, the voucher specimens were placed at the Herbarium, Department of Biology, Ibn Tofail University, Morocco, for future reference.

2.2.3 Data analysis

A descriptive and quantitative statistical technique was applied (ANOVA One-way and Independent Samples t-Test, p-values of 0.05 or less were considered significant). The findings of the ethnobotanical survey were evaluated using the Family Importance Value (FIV), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), Plant Part Value (PPV), Fidelity Level (FL), and Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) (ICF). The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 21 and Microsoft Excel 2010 was used for all statistical analyses.

2.2.3.1 Family importance value

The FIV recognizes the importance of plant families. It is a cultural significance measure that may be used in ethnobotany to assess the worth of natural plant taxa. To calculate FIV, we use the following formula: Where FCfamily = RFC is the number of informants who mentioned the family, and Ns denotes each family’s total number of species (Sreekeesoon & Mahomoodally, 2014).

2.2.3.2 Frequency and relative frequency of citation

The relative frequency of citation (RFC) is calculated by dividing the frequency of citation (FC) by the total number of survey participants (N). The RFC value for medicinal plant species is calculated using the proportion of informants who mention the species. The following formula was used to compute the RFC (Tardío & Pardo-de-Santayana, 2008): with (0 < RFC <1).

2.2.3.3 Plant part value

Plant part value (PPV) was calculated using the following formula: Where RU is the number of uses reported of all parts of the plant and RUplant part is the sum of uses reported per part of the plant. The section with the greatest PPV is the most often utilized by responders (Chaachouay et al., 2019d).

2.2.3.4 Fidelity level

The fidelity level (FL) refers to the proportion of informants who acknowledged using certain plant species to cure a specific condition in the research location. This formula is used to determine the FL index (Friedman et al., 1986): . Where Np denotes the number of informants who assert using a particular plant species to cure a specific ailment and N represents the number of informants who claim the use of plants as a medication to treat any given disease.

2.2.3.5 Informant consensus factor

An informant consensus factor was derived from seeking an agreement between the informants on the documented cures for each group of diseases (Heinrich et al., 1998). . Nur denotes the total number of usage reports for each illness category, and Nt indicates the number of species utilized.

3 Results

3.1 Socio-demographic features of the informants

Six hundred local informants were questioned, including 311 females and 289 men (a female/male sex ratio of 1.08). Traditional herbal treatments have an effect on both sexes in the Moroccan Rif. At the research area level, the majority of respondents (45.7 percent) were between the ages of 40 and 60, followed by informants older than 60 years (25.8 percent) and informants between the ages of 20 and 40 years (22.3 percent). Finally, informants less than 20 years old are placed last (6.2 percent). The analysis of the collected data reveals that married people (80.3 percent) use MAPs significantly more than divorced people (10.3 percent). In comparison, widowers account for 7.3 percent of the population. Singles account for only 2.1 percent because married people can avoid or minimize the material charges imposed by the doctor and pharmacist. In terms of education, 75.2 percent of respondents are illiterate, with elementary education accounting for 20.3 percent. Nonetheless, just 4.5 percent of persons with a secondary education utilize medicinal herbs. However, 63.4 percent were jobless, 26.1 percent had a low socioeconomic level, 10% had an average level, and just 0.5 percent had a better income (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic details of the informants in the Moroccan Rif area.

| Variables | Categories | Number of informants n = 600 | Percentages (%) | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 311 | 51.8 | 0.053 |

| Male | 289 | 48.2 | ||

| Age groups | <18 years | 37 | 6.2 | 0.000 |

| 20–40 | 134 | 22.3 | ||

| 40–60 | 274 | 45.7 | ||

| >60 years | 155 | 25.8 | ||

| Family situation | Married | 482 | 80.3 | 0.000 |

| Divorced | 62 | 10.3 | ||

| Widower | 44 | 7.3 | ||

| Single | 12 | 2.1 | ||

| Educational level | Illiterate | 451 | 75.2 | 0.000 |

| Primary | 122 | 20.3 | ||

| Secondary | 27 | 4.5 | ||

| University | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Income/month | Unemployed | 380 | 63.4 | 0.000 |

| 250–1500 DH | 157 | 26.1 | ||

| 1,500–5000 DH | 60 | 10 | ||

| >5000 DH | 3 | 0.5 |

3.2 Medicinal plant species of the study area

Thirty-three medicinal plant species from 20 botanical families were employed to treat cardiovascular disorders in the study region. Among the information acquired during this study was the local name of the medicinal plants, their scientific name, preparation methods, the portion of the plant utilized, and the medical prescription for which it is employed. The data are organized alphabetically by family name, and the FIV, RFC, FL, and ICF data are shown in Tables 2. According to the number of species and the FIV score, the most botanical family of medicinal plant species used to treat cardiovascular disorders was Poaceae with seven species (FIV 0.02), followed by Fabaceae with three species (FIV 0.035). In comparison, other families had only one or two species.

TABLE 2.

List of medicinal and aromatic plant actives on the cardiovascular diseases in the Moroccan Rif region.

| Family and scientific name | Vernacular name | Part used | Mode of preparation | Medicinal uses | FL | FC | RFC | FIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | 0.093 | |||||||

| Spinacia oleracea L | Sabanikh, Selq | Leaf | Raw | HA | 100 | 56 | 0.093 | |

| Amaryllidaceae | 0.159 | |||||||

| Allium sativum L | Touma, Tishert | Bulb | Cooked | HA | 100 | 118 | 0.197 | |

| Allium porrum L | Borro | Bulb | Infusion | HA | 100 | 72 | 0.12 | |

| Apiaceae | 0.17 | |||||||

| Daucus carota L | Khizou | Leaf | Decoction | HA | 100 | 102 | 0.17 | |

| Araliaceae | 0.002 | |||||||

| Hedera hebernica (G.Kirchn.) Carrière | Louwaya | Leaf | Infusion | BP | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Arecaceae | 0.076 | |||||||

| Phoenix dactylifera L | Tmar, Tazdayet | Fruit | Other | HA, AG | 78 | 46 | 0.076 | |

| Asteraceae | 0.017 | |||||||

| Carduus getulus Pomel | Lssan Maghribi | Leaf | Other | AG | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Cynara scolymus L | Lqoq | Whole plant | Decoction | HA | 100 | 09 | 0.015 | |

| Cactaceae | 0.031 | |||||||

| Opuntia ficus indica (L.) Mill | Sbar, Zaâboul | Fruit | Infusion | BP | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Opuntia ficus-barbarica A.Berger | Hendya | Seed | Decoction | HA | 100 | 36 | 0.06 | |

| Cannabaceae | 0.018 | |||||||

| Cannabis sativa L | Lkif | Seed | Cataplasm | AG | 100 | 11 | 0.018 | |

| Dryopteridaceae | 0.002 | |||||||

| Dryopteris filix-mas (L.) Schott | Sarkhs Dakar | Leaf | Decoction | BP | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Fabaceae | 0.035 | |||||||

| Lens culinaris Medik | Aaddes | Seed | Cooked | HA | 100 | 48 | 0.08 | |

| Medicago polymorpha L | Fessa | Whole plant | Decoction | AG | 100 | 14 | 0.023 | |

| Vicia sativa L | Guersana | Whole plant | Infusion | BP | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Geraniaceae | 0.005 | |||||||

| Erodium cicutarium (L.) L'Hér | Rakma Chokrania | Leaf | Cooked | AG | 100 | 03 | 0.005 | |

| Iridaceae | 0.002 | |||||||

| Gladiolus italicus Mill | Dalbout Itali | Leaf | Other | AG | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Lauraceae | 0.105 | |||||||

| Laurus nobilis L | Wrak Sidnamossa, Rend | Leaf | Decoction | HA, AG, BP | 0.89 | 91 | 0.152 | |

| Persea gratissima C.F.Gaertn | Avocat | Fruit | Cataplasm | HA | 100 | 35 | 0.058 | |

| Malvaceae | 0.002 | |||||||

| Hibiscus sabdariffa L | Karkadé | Leaf | Decoction | BP | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Poaceae | 0.02 | |||||||

| Zea mays L | Dra | Fruit | Decoction | HA | 100 | 08 | 0.013 | |

| Phragmites communis Trin | Kseb | Root | Infusion | HA | 100 | 74 | 0.123 | |

| Glyceria fluitans (L.) R.Br | Aaima | Whole plant | Other | BP | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Miscanthus sinensis Andersson | Kseb Chinwa | Leaf | Decoction | BP | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Pennisetum setaceum (Forssk.) Chiov | Dyl Ethaalab | Seed | Decoction | BP | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Hordeum murinum L | Chaair El FIran | Leaf | Infusion | AG | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Avena barbata Pott ex Link | Chofan Barri | Whole plant | Raw | AG | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Polygonaceae | 0.043 | |||||||

| Rumex sanguineus L | Hommida | Leaf | Decoction | AG | 100 | 26 | 0.043 | |

| Ranunculaceae | 0.003 | |||||||

| Ranunculus bullatus L | Wden Elhallouf | Root | Decoction | AG | 100 | 02 | 0.003 | |

| Rosaceae | 0.082 | |||||||

| Rubus ulmifolius Schott | Oualik, Tabgha | Leaf | Raw | HA | 100 | 49 | 0.082 | |

| Rubiaceae | 0.104 | |||||||

| Rubia peregrina L | Fûwa, Tarubya | Root | Infusion | HA | 100 | 123 | 0.205 | |

| Galium aparine L | Lsak | Leaf | Infusion | AG | 100 | 01 | 0.002 | |

| Solanaceae | 0.001 | |||||||

| Solanum sodomaeum Dunal | Tfah Lfar | Fruit | Cataplasm | BP | 100 | 07 | 0.001 |

HA: heart arrhythmia; AG: angina; BP: blood pressure.

3.3 RFC and FL plant species

To assess the relative relevance of reported medicinal plants, the relative frequency of citation (RFC) was determined based on informants’ citations for certain understudied species, with values ranging from 0.002 to 0.205. Results of this study depicted that Rubia peregrina L. exhibited the higher RFC (0.205), followed by the Allium sativum L (RFC = 0.197), Daucus carota L (RFC = 0.17), and Laurus nobilis L (RFC = 0.152). Thirteen plant species have the lowest RFC (RFC = 0.002 each). We computed the FL to find the most often utilized species for each disease group. According to our findings, twenty-two species with the greatest FL of 100% were employed by respondents to treat cardiovascular illnesses (Table 2).

3.4 Plant parts used to treat cardiovascular problems

The inhabitants of Morocco’s Rif region pick various plant parts to manufacture traditional cures (e.g., seed, root, flower, bulb, fruit, leaf, and whole plant). According to the plant part value PPV index, the leaf was reported as the dominating plant part for cardiovascular treatment manufacture in the research region (PPV 0.353), followed by root (PPV 0.213), bulb (PPV 0.201), fruit (PPV 0.103), seed (PPV 0.102), and the entire plant (PPV 0.027) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Parts of medicinal plants used in the study area.

3.5 Remedies preparation method and routes of administration

Many preparation methods are used to administer the plant’s active ingredients, including decoction, fumigation, cataplasm, infusion, maceration, cooked, and raw (Figure 4). In the study region, decoction continues to be the most common method of preparation (31%), followed by infusion (29%), cooked (17.9%), and raw (10.7%) cataplasm (6.2 percent). The combined proportion of other preparation forms (fumigation, maceration) is not more than 5.2 percent. The method of administration varies depending on the ailment and the ingredients employed. In general, the majority of prepared recipes (84 percent) are administered orally, followed by massage (5.7 percent), various modes of administration (5 percent), swabbing (4 percent), and washing (4 percent) (1.3 percent).

FIGURE 4.

Frequency of different methods of preparation.

3.6 Conditions of medicine preparation

Most of the time, the locals said that they prefer the fresh plant part over the dried plant part for medicine making. The bulk of the cures in the research region (62%) were made from new portions of medicinal plants, followed by dried forms (35.4%) and (2.6%) made from both dry and fresh plant components.

3.7 Source of knowledge about medicinal plants

In our ethnobotanical study, we discovered that 69.3 percent of the population gained information about the therapeutic use of plants as a cure for cardiovascular problems from the experiences of others. This shows the relative transmission of cultural behaviors across generations. 19% of respondents practice herbal medicine on the advice of herbalists, 10.3 percent received information from a pharmacist, and only 1.6 percent gained knowledge through reading books about traditional Arab medicine, watching television programs, or through personal experience with a large number of medicinal plants in their surroundings. As a result, the environment and the experiences of others continue to be the most effective methods of transmitting information about the medical uses of plants (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Traditional knowledge acquisition modes.

3.8 Medicinal use and informant consensus factor

Cardiovascular illnesses are classified into three ailment groups in the study region, and informant consensus factor (ICF) analyses were performed. The ICF values for the various uses categories in this research varied from 0.44 to 0.98. A total of 33 species have been identified as potential therapeutic agents for cardiovascular disorders. For each class, the informant consensus factors have been determined (Table 3). The most incredible ICF value (0.98) is found for disorders connected with cardiac arrhythmia, whereas the lowest ICF value (0.44) is founded for hypertension.

TABLE 3.

ICF values by categories for treating cardiovascular diseases.

| Categories | List of plant species used and number of citations | Total number of | ICF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Use citations | |||

| Heart arrhythmia (HA) | Daucus carota L. (102), Allium porrum L. (72), Cynara scolymus L. (9), Opuntia ficus-barbarica A.Berger. (36), Spinacia oleracea L. (56), Lens culinaris Medik. (48), Laurus nobilis L. (81), Persea gratissima C.F.Gaertn. (35), Allium sativum L. (118), Zea mays L. (8), Phragmites communis Trin. (74), Rubus ulmifolius Schott. (49), Rubia peregrina L. (123), Phoenix dactylifera L. (10) | 14 | 821 | 0.98 |

| Angina (AG) | Phoenix dactylifera L. (36), Carduus getulus Pomel. (1), Cannabis sativa L. (11), Medicago polymorpha L. (14), Erodium cicutarium (L.) L'Hér. (3), Gladiolus italicus Mill. (1), Hordeum murinum L. (1), Avena barbata Pott ex Link. (1), Rumex sanguineus L. (26), Ranunculus bullatus L. (2), Galium aparine L. (1), Laurus nobilis L. (7) | 12 | 104 | 0.88 |

| Blood pressure (BP) | Hedera hebernica (G.Kirchn.) Carrière. (1), Opuntia ficus indica (L.) Mill. (1), Dryopteris filix-mas (L.) Schott (1), Vicia sativa L. (1), Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (1), Glyceria fluitans (L.) R.Br. (1), Miscanthus sinensis Andersson. (1), Pennisetum setaceum (Forssk.) Chiov. (1), Solanum sodomaeum Dunal. (7), Laurus nobilis L. (3) | 10 | 18 | 0.44 |

4 Discussion

Traditional herbal treatments have an effect on both sexes in the Moroccan Rif. However, females have a greater knowledge of the plant species and their use with a predominance of 51.8% against a percentage of 48.2% among males though the test (independent sample t-test) did not show a significant difference (p = 0.053) between male and female informants on the number of medicinal plant species they listed and associated uses reported. The vigilance of women for the balance the illness and their loyalty to everything traditional might explain this female preponderance. Women provide food and treatment to their families in times of disease. These findings corroborate the findings of earlier ethnobotanical studies conducted nationwide (Chaachouay et al., 2019a; Orch et al., 2021; Benkhnigue et al., 2022).

The majority of respondents were between the ages of 40 and 60, followed by informants older than 60 years. ANOVA One-way analysis revealed significant differences (p = 0.000). The responders of the most significant age offer more accurate information because they possess a large amount of ancestral knowledge that is passed down orally. As a result, there is a loss of ability about MAPs, which may be explained by the skepticism of some young people, who are disinterested in this herbal medication due to modernity and foreign cultural influences. Conventional medical knowledge passed down from generation to generation is in jeopardy since transmission between the elderly and the younger generation is not always guaranteed (Anyinam, 1995). These findings corroborate those observed in other parts of Morocco (Orch et al., 2021; Benkhnigue et al., 2022).

The analysis of the collected data reveals that married people use medicinal plants significantly more than others. The relationship between family status and indigenous knowledge of cardiovascular disease management was statistically significant (p = 0.000). These results corroborate earlier studies done by in others areas (El Hilah et al., 2015). In terms of education, 75.2 percent of respondents are illiterate, with elementary education accounting for 20.3 percent. As a result, the difference in educational level and indigenous knowledge was statistically significant (p = 0.000). As a result, the utilization of MAPs diminishes as the degree of study rises. This conclusion is consistent with the results of previous investigations (Lahsissene et al., 2009; El Hilah et al., 2015; Bouzid et al., 2017; Chaachouay et al., 2021). In our study, 63.4% were unemployed, 26.1% had a low socioeconomic level, and 10% had an average level, just 0.5 percent had a better grade. The difference in monthly income and indigenous knowledge was statistically significant (p = 0.000). The expensive expense of current medical treatments and their adverse effects are among the primary reasons why respondents preferred herbal therapy. As a result, we can observe that the usage of plants grows as the monthly income of these informants rises. These findings are comparable to those surveyed in Morocco’s Moyen Moulouya (Douiri et al., 2007).

Thirty-three medicinal plant species from 20 botanical families were employed to treat cardiovascular disorders in the Rif. According to the number of species the most botanical family of medicinal plant species used by local people of Rif to treat cardiovascular disorders was Poaceae with seven species (FIV 0.02), followed by Fabaceae with three species (FIV 0.035). In comparison, other families had only one or two species. This large percentage of Poaceae may be explained by the family’s significant presence in the Rif’s flora due to ecological variables that support the growth and adaption of the majority of this family’s species. This representation has been found in various ethnomedicinal studies undertaken in different areas, with minor divergences (Jouad et al., 2001; Eddouks et al., 2002; Okello et al., 2010; Yetein et al., 2013; Ahmad et al., 2014; Orch et al., 2021; Benkhnigue et al., 2022).

Results of this study depicted that Rubia peregrina L. exhibited the higher RFC (0.205), followed by the Allium sativum L (RFC = 0.197), Daucus carota L (RFC = 0.17), and Laurus nobilis L (RFC = 0.152). Thirteen plant species have the lowest RFC (RFC = 0.002 each). These plants had the highest RFC index because many informants cited them, and RFC is directly proportional to the number of informants who mention the usage of a particular plant. Medicinal plant species with a high RFC should be further analyzed phytochemically and pharmaceutically to determine their active ingredients for any medication extraction (Vitalini et al., 2013). These species should also be conserved since their chosen usage may jeopardize their populations owing to overharvesting. According to our findings, twenty-two species with the greatest FL of 100% were employed by respondents to treat cardiovascular illnesses. The most excellent FL score implies that plant species are favored by the research population when treating a specific condition. The MAPs with a high degree of authenticity have more therapeutic potential and include more natural components in the Moroccan Rif area (tannins, flavonoids, and alkaloids).

Concerning the plant part value PPV index, the leaf was reported as the dominating plant part for cardiovascular treatment manufacture in the research region (PPV 0.353), followed by root (PPV 0.213) and bulb (PPV 0.201). The choice of leaves was based on their ease of availability, ease of harvesting, and ease of remedy formulation. Furthermore, the leaves are the site of photosynthesis and, in some instances, the storage of secondary metabolites that contribute to the plant’s biological features. Our findings on the amounts of various plant parts utilized in this study accord with the majority of earlier ethnomedicinal studies conducted in numerous different countries, which have revealed the dominance of the leaf as a material used in the manufacture of herbal medications (Teklehaymanot & Giday, 2007; Lulekal et al., 2008; Simbo, 2010; Chaachouay & Zidane, 2019; Chaachouay et al., 2020b; Chaachouay et al., 2021b; Benkhnigue et al., 2022).

In the study region, decoction continues to be the most common method of preparation, followed by infusion, and cooked. The combined proportion of other preparation forms (fumigation, maceration) is not more than 5.2 percent. The decoction’s widespread usage is explained by the fact that it allows for the collection of the most active elements and attenuates or eliminates the poisonous impact of some recipes. In other parts of Morocco, ethnobotanical research surveys revealed that most respondents prepared the treatment using decoction (Ramana, 2008; Ghasemi et al., 2013; Chaachouay et al., 2020a; Chaachouay & Zidane, 2021; Kumar et al., 2021; Orch et al., 2021; Benkhnigue et al., 2022). This demonstrates that the Moroccan people are constantly exchanging knowledge about the usage of therapeutic and aromatic herbs. At the continental level, decoction is described as the primary preparation technique (Okello et al., 2010; Stangeland et al., 2011; Yetein et al., 2013). The majority of prepared recipes are administered orally, followed by massage. The region’s high frequency of internal diseases may explain the region’s preponderance of oral administration (Polat & Satıl, 2012). On the other hand, it is assumed that the oral route is the most agreeable to the patient. The preponderance of oral administration of several medicinal plants in Moroccan Rif is entirely consistent with most ethnobotanical investigations conducted in Africa (Abdurhman, 2010, 2010; Benarba et al., 2014; Sreekeesoon & Mahomoodally, 2014; Chermat & Gharzouli, 2015; Chaachouay et al., 2021a; Chaachouay & Zidane, 2022).

The bulk of the cures in the research region (62%) were made from fresh parts of medicinal plants. According to research done in Tigray (Abdurhman, 2010) 86 percent of preparations were in a fresh form, whereas Getahun (Getahun, 1976) revealed that 64 percent of medicinal herbs were utilized in fresh condition and 36 percent in dried form. The Moroccan Rif people’s reliance on fresh materials is mainly owing to the efficacy of fresh medicinal herbs in therapy since the contents are not lost before usage, as opposed to dried versions.

The ICF values for the various uses categories in this research varied from 0.44 to 0.98. A total of 33 species have been identified as potential therapeutic agents for cardiovascular disorders. For each class, the informant consensus factors have been determined. The most incredible ICF value (0.98) is found for disorders connected with cardiac arrhythmia, whereas the lowest ICF value (0.44) is founded for hypertension. The ICF findings showed that illnesses prevalent in the Moroccan Rif region had a higher informant consensus factor (0.98). These high ICF values suggested that informants were reasonably reliable on the usage of medicinal plant species (Lin et al., 2002). The informant consensus values also suggested that the people share knowledge about the most important medicinal plant species for treating the most often encountered ailments in the research region. As a result, species with high ICF should be prioritized for future pharmacological, toxicological, and phytochemical investigations.

5 Conclusion

The ethnobotanical survey found that the study region is rich in biodiversity, with a diverse range of medicinal and aromatic species, and that more inquiry is necessary. This opulent flower arrangement demonstrates the enormous potential for traditional knowledge to aid in creating natural product derivatives as inexpensive medications. These plants continue to play a critical part in people’s lives in the Moroccan Rif. However, ethnomedicinal data for medicinal plants used to treat cardiovascular disorders in this area is lacking. According to the findings of this study, increasing the use-value, preference ranking scores, and fidelity level values of recorded medicinal plant species will facilitate future pharmaceutical and phytochemical research and conservation methods. In this regard, emphasis should be placed on conserving traditional medicinal plants and related indigenous knowledge in the Moroccan Rif region to ensure their continued viability.

Acknowledgments

We would like to offer our deepest gratitude to all of the Rif region’s authorities and local people for their assistance. We also want to thank everyone who helped make this project a reality.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

NC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Writing A Original Draft. AA: Software, Writing. BB: Validation, Visualization. LZ: Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Project administration.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Abdurhman N. (2010). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local people in ofla wereda, southern zone of Tigray region Ethiopia. Addis Ababa University. MSc Thesis, 1–112. http://etd.aau.edu.et/handle/123456789/1869 . Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M., Sultana S., Fazl-i-Hadi S., Ben Hadda T., Rashid S., Zafar M., et al. (2014). An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in high mountainous region of chail valley (district swat-Pakistan). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 10 (1), 36. 10.1186/1746-4269-10-36 PubMed Abstract | 10.1186/1746-4269-10-36 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anyinam C. (1995). Ecology and ethnomedicine: Exploring links between current environmental crisis and indigenous medical practices. Soc. Sci. Med. 4, 321–329. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0098-d 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0098-d | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellakhdar J. (1997). Contribution à l’étude de la pharmacopée traditionnelle au maroc: La situation actuelle, les produits, les sources du savoir (enquête ethnopharmacologique de terrain réalisée de 1969 à 1992). Université Paul Verlaine-Metz. [PhD Thesis]. https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/tel-01752084 . Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Benabid A., Bellakhdar J. (1987). Relevés floristiques et catalogue des plantes médicinales dans le Rif Occidental. Al Biruniya 3 (2), 87–120. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Benarba B., Meddah B., Tir Touil A. (2014). Response of bone resorption markers to Aristolochia longa intake by Algerian breast cancer postmenopausal women. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 820589. 10.1155/2014/820589 PubMed Abstract | 10.1155/2014/820589 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkhnigue O., Chaachouay N., Khamar H., El Azzouzi F., Douira A., Zidane L. (2022). Ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological study of medicinal plants used in the treatment of anemia in the region of Haouz-Rehamna (Morocco). J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 10 (2), 279–302. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Bouzid A., Chadli R., Bouzid K. (2017). Étude ethnobotanique de la plante médicinale Arbutus unedo L. dans la région de Sidi Bel Abbés en Algérie occidentale. Phytothérapie 15 (6), 373–378. 10.1007/s10298-016-1027-6 10.1007/s10298-016-1027-6 | Google Scholar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Benkhnigue O., Douira A., Zidane L. (2021). Poisonous medicinal plants used in the popular pharmacopoeia of the Rif, northern Morocco. Toxicon 189, 24–32. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2020.10.028 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/j.toxicon.2020.10.028 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Benkhnigue O., El Ibaoui H., El Ayadi R., Zidane L. (2019a). Medicinal plants used for diabetic problems in the Rif, Morocco. Ethnobot. Res. App. 18, 1–19. 10.32859/era.18.21.1-29 10.32859/era.18.21.1-29 | Google Scholar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Benkhnigue O., Fadli M., El Ayadi R., Zidane L. (2019b). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat osteoarticular diseases in the Moroccan Rif, Morocco. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 7 (6), 454–470. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Benkhnigue O., Fadli M., El Ibaoui H., El Ayadi R., Zidane L., et al. (2019c). Ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological study of medicinal and aromatic plants used in the treatment of respiratory system disorders in the Moroccan Rif. Ethnobot. Res. App. 18, 1–16. 10.32859/era.18.22.1-17 10.32859/era.18.22.1-17 | Google Scholar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Benkhnigue O., Fadli M., El Ibaoui H., Zidane L. (2019d). Ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological studies of medicinal and aromatic plants used in the treatment of metabolic diseases in the Moroccan Rif. Heliyon 5 (10), e02191. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02191 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02191 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Benkhnigue O., Zidane L. (2020a). Ethnobotanical study aimed at investigating the use of medicinal plants to treat nervous system diseases in the Rif of Morocco. J. Chiropr. Med. 19 (1), 70–81. 10.1016/j.jcm.2020.02.004 10.1016/j.jcm.2020.02.004 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Douira A., Hassikou R., Brhadda N., Dahmani J., Belahbib N., et al. (2020b). Etude floristique et ethnomédicinale des plantes aromatiques et médicinales dans le Rif (Nord du Maroc). Département de Biologie - Université Ibn Tofail - Kénitra. Phdthesis. Available at: https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03376377 . Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Douira A., Zidane L. (2021a). COVID-19, prevention and treatment with herbal medicine in the herbal markets of Salé Prefecture, North-Western Morocco. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 42, 101285. 10.1016/j.eujim.2021.101285 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/j.eujim.2021.101285 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Douira A., Zidane L. (2021b). Herbal medicine used in the treatment of human diseases in the Rif, northern Morocco. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 47, 131–153. 10.1007/s13369-021-05501-1 PubMed Abstract | 10.1007/s13369-021-05501-1 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N. (2020). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal and aromatic plants used in the treatment of genito-urinary diseases in the Mo. Available at: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=fr&user=DMXnc0oAAAAJ&cstart=20&pagesize=80&citation_for_view=DMXnc0oAAAAJ:4DMP91E08xMC . PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Zidane L. (2021). Cystitis treatment with phytotherapy within the Rif, northern Morocco. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 7 (1), 81. 10.1186/s43094-021-00226-2 10.1186/s43094-021-00226-2 | Google Scholar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Zidane L. (2022). Ethnobotanical and Ethnomedicinal study of medicinal and aromatic plants used against dermatological diseases by the people of Rif, Morocco. J. Herb. Med. 32, 100542. 10.1016/j.hermed.2022.100542 10.1016/j.hermed.2022.100542 | Google Scholar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaachouay N., Zidane L. (2019). “Ethnomedicinal studies on medicinal plants used by people of Rif, Morocco,” in Proceedings of 5th international electronic conference on medicinal chemistry. 6406. 10.3390/ECMC2019-06406 10.3390/ECMC2019-06406 | Google Scholar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chermat S., Gharzouli R. (2015). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora in the north east of Algeria-an empirical knowledge in djebel zdimm (setif). J. Mater Sci. Eng. 5, 50–59. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Cotton C. M., Wilkie P. (1996). Ethnobotany: Principles and applications. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- DMNM (2018). Direction de la Météorologie nationale. Maroc. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Douiri E., El Hassani M., Bammi J., Badoc A., Douira A. (2007). Plantes vasculaires de la Moyenne Moulouya (maroc oriental). Bull. Soc. Linn. Bordx. 142, 409–438. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Eddouks M., Maghrani M., Lemhadri A., Ouahidi M.-L., Jouad H. (2002). Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiac diseases in the south-east region of Morocco (Tafilalet). J. Ethnopharmacol. 82 (2–3), 97–103. 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00164-2 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00164-2 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hilah F. B. A., Dahmani J., Belahbib N., Zidane L. (2015). Étude ethnobotanique des plantes médicinales utilisées dans le traitement des infections du système respiratoire dans le plateau central marocain. J. Animal &Plant Sci. 25 (2), 3886–3897. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Fennane M., Ibn Tattou M., El Oualidi J. (2014). “Flore pratique du Maroc, dicotylédones,” in Monocotylédones. Travaux de l’Institut Scientifique Rabat (Série Botanique, 40. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Fennane M., Tattou M. I., Mathez J., Quézel P. (1999). Flore pratique du Maroc: Manuel de détermination des plantes vasculaires. Pteridophyta, Gymnospermae, Angiospermae (Lauraceae-Neuradaceae). Institut scientifique. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Fennane M., Tattou M. I., Valdés B. (1998). “Catalogue des plantes vasculaires rares, menacées ou endémiques du Maroc,” in Herbarium mediterraneum panormitanum. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J., Yaniv Z., Dafni A., Palewitch D. (1986). A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 16 (2–3), 275–287. 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90094-2 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90094-2 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getahun A. (1976). Some common medicinal and poisonous plants used in Ethiopian folk medicine. Amare Getahun 07, 1–25. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi P. A., Momeni M., Bahmani M., GhAsemi PirbAlouti A. (2013). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by Kurd tribe in Dehloran and Abdanan districts, Ilam province, Iran. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 10 (2), 368–385. 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i2.24 PubMed Abstract | 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i2.24 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurib-Fakim A. (2009). “Natural Product networks in Africa and their contribution to cooperation and economic development,” in Regional and interregional cooperation to strengthen basic Sciences in developing countries, 103. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- HCP (2018). “Haut-commissariat au plan, Monograpie de la région Tanger Tétouan Al Hoceima,” in Direction régionale de Tanger-tétouan-Al hoceima. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich M., Ankli A., Frei B., Weimann C., Sticher O. (1998). Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 47 (11), 1859–1871. 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00181-6 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00181-6 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S. K. (1964). The role of botanist in folklore research. Folklore 5 (4), 145–150. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Jouad H., Haloui M., Rhiouani H., El Hilaly J., Eddouks M. (2001). Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes, cardiac and renal diseases in the North centre region of Morocco (Fez–Boulemane). J. Ethnopharmacol. 77 (2–3), 175–182. 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00289-6 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00289-6 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotoé J. R., Dougnon T. V., Koudouvo K., Atègbo J. M., Loko F., Akoègninou A., et al. (2013). Ethnopharmacological survey on antihemorrhagic medicinal plants in South of Benin. Eur. J. Med. Plants 3 (1), 40–51. 10.9734/ejmp/2013/2093 10.9734/ejmp/2013/2093 | Google Scholar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Kumar S., Ramchiary N., Singh P. (2021). Role of traditional ethnobotanical knowledge and indigenous communities in achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 13 (6), 3062. 10.3390/su13063062 10.3390/su13063062 | Google Scholar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lahsissene H., Kahouadji A., Hseini S. (2009). Catalogue des plantes medicinales utilisees dans la region de Zaër (Maroc Occidental). Lejeunia . Revue de Botanique. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Puckree T., Mvelase T. P. (2002). Anti-diarrhoeal evaluation of some medicinal plants used by Zulu traditional healers. J. Ethnopharmacol. 79 (1), 53–56. 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00353-1 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00353-1 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A. D., Mathers C. D., Ezzati M., Jamison D. T., Murray C. J. (2006). Global burden of disease and risk factors. The World Bank: World Bank and Oxford University Press.. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/ handle/10986/7039 Google Scholar [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lulekal E., Kelbessa E., Bekele T., Yineger H. (2008). An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Mana Angetu District, southeastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 4 (1), 10. 10.1186/1746-4269-4-10 PubMed Abstract | 10.1186/1746-4269-4-10 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muna W. F. (1993). Cardiovascular disorders in Africa. World Health Stat. Q. 46 (2), 125–133. PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okello S. V., Nyunja R. O., Netondo G. W., Onyango J. C. (2010). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by Sabaots of Mt. Elgon Kenya. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 7 (1)–10. 10.4314/ajtcam.v7i1.57223 10.4314/ajtcam.v7i1.57223 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orch H., Chaachouay N., Douiri E. M., Faiz N., Zidane L., Douira A. (2021). Use of medicinal plants in dermato-cosmetology: An ethnobotanical study among the population of Izarène. Jordan J. Pharm. Sci. 14, 323–340. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Polat R., Satıl F. (2012). An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Edremit Gulf (Balıkesir–Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 139 (2), 626–641. 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.004 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.004 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramana M. V. (2008). Ethnomedicinal and ethnoveterinary plants from boath, adilabad district, Andhra Pradesh, India. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2008 (1), 46. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Sijelmassi A. (1993). Les plantes médicinales du Maroc, 3ème édition Fennec. Moroc: Casablanca. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Simbo D. J. (2010). An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Babungo, Northwest Region, Cameroon. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 6 (1), 8. 10.1186/1746-4269-6-8 PubMed Abstract | 10.1186/1746-4269-6-8 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreekeesoon D. P., Mahomoodally M. F. (2014). Ethnopharmacological analysis of medicinal plants and animals used in the treatment and management of pain in Mauritius. J. Ethnopharmacol. 157, 181–200. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.030 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.030 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangeland T., Alele P. E., Katuura E., Lye K., are A. (2011). Plants used to treat malaria in Nyakayojo sub-county, Western Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 137 (1), 154–166. 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.002 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.002 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong K., Mathers C., Epping-Jordan J., Beaglehole R. (2006). Preventing chronic disease: A priority for global health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 35 (2), 492–494. 10.1093/ije/dyi315 PubMed Abstract | 10.1093/ije/dyi315 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardío J., Pardo-de-Santayana M. (2008). Cultural importance indices: A comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of southern cantabria (northern Spain)1. Econ. Bot. 62 (1), 24–39. 10.1007/s12231-007-9004-5 10.1007/s12231-007-9004-5 | Google Scholar [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teklehaymanot T., Giday M. (2007). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by people in Zegie Peninsula, Northwestern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 3 (1), 12. 10.1186/1746-4269-3-12 PubMed Abstract | 10.1186/1746-4269-3-12 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdés B. (2002). Catalogue des plantes vasculaires du Nord du Maroc, incluant des clés d’identification, 1. Editorial CSIC-CSIC Press. Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Vitalini S., Iriti M., Puricelli C., Ciuchi D., Segale A., Fico G., et al. (2013). Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in val san giacomo (sondrio, Italy)—an alpine ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 145 (2), 517–529. 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.024 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.024 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2001). Legal status of traditional medicine and complementary. World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42452 . Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

- Yetein M. H., Houessou L. G., Lougbégnon T. O., Teka O., Tente B. (2013). Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used for the treatment of malaria in plateau of Allada, Benin (West Africa). J. Ethnopharmacol. 146 (1), 154–163. 10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.022 PubMed Abstract | 10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.022 | Google Scholar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. (1998). “Regulatory situation of herbal medicines—a worldwide review,” in Traditional medicine programme (World Health Organization; ). WHO/TRM/98.1. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/ 63801 Google Scholar [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.