Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a major cause of ocular infectious (corneal infection or microbial keratitis (MK) and conjunctivitis) and non-infectious corneal infiltrative events (niCIE). Despite the significant morbidity associated with these conditions, there is very little data about specific virulence factors associated with the pathogenicity of ocular isolates. A set of 25 S. aureus infectious and niCIEs strains isolated from USA and Australia were selected for whole genome sequencing. Sequence types and clonal complexes of S. aureus strains were identified by using multi-locus sequence type (MLST). The presence or absence of 128 virulence genes was determined by using the virulence finder database (VFDB). Differences between infectious (MK + conjunctivitis) and niCIE isolates from USA and Australia for possession of virulence genes were assessed using the chi-square test. The most common sequence types found among ocular isolates were ST5, ST8 while the clonal complexes were CC30 and CC1. Virulence genes involved in adhesion (ebh, clfA, clfB, cna, sdrD, sdrE), immune evasion (chp, esaD, esaE, esxB, esxC, esxD), and serine protease enzymes (splA, splD, splE, splF) were more commonly observed in infectious strains (MK + conjunctivitis) than niCIE strains (p = 0.004). Toxin genes were present in half of infectious (49%, 25/51) and niCIE (51%, 26/51) strains. USA infectious isolates were significantly more likely to possess splC, yent1, set9, set11, set36, set38, set40, lukF-PV, and lukS-PV (p < 0.05) than Australian infectious isolates. MK USA strains were more likely to possesses yent1, set9, set11 than USA conjunctivitis strains (p = 0.04). Conversely USA conjunctivitis strains were more likely to possess set36 set38, set40, lukF-PV, lukS-PV (p = 0.03) than MK USA strains. The ocular strain set was then compared to 10 fully sequenced non-ocular S. aureus strains to identify differences between ocular and non-ocular isolates. Ocular isolates were significantly more likely to possess cna (p = 0.03), icaR (p = 0.01), sea (p = 0.001), set16 (p = 0.01), and set19 (p = 0.03). In contrast non-ocular isolates were more likely to possess icaD (p = 0.007), lukF-PV, lukS-PV (p = 0.01), selq (p = 0.01), set30 (p = 0.01), set32 (p = 0.02), and set36 (p = 0.02). The clones ST5, ST8, CC30, and CC1 among ocular isolates generally reflect circulating non-ocular pathogenic S. aureus strains. The higher rates of genes in infectious and ocular isolates suggest a potential role of these virulence factors in ocular diseases.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, ocular infectious isolates, whole genome sequencing, virulence factors

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for nearly 70% of ocular infections worldwide [1]. These can result in tissue damage, morbidity, and vision loss [2,3]. S. aureus infections involving the cornea (microbial keratitis; MK) can be sight-threatening and the organism is the most common cause of MK in Australia [4,5] and USA [6,7]. S. aureus can also cause conjunctivitis [8] and non-infectious corneal infiltrative events (niCIE) during contact lens wear [9].

S. aureus is known to encode a diverse arsenal of virulence determinants that enables it to cause a variety of infections [10]. The genomic make-up of S. aureus influences the virulence of its strains and pathogenicity associated with its disease [11]. The antibiotic susceptibility data of the isolates previously reported [12] and used in this study demonstrated that although most of the strains were multi-drug resistant (MDR), the non-infectious (niCIE) strains were more susceptible to antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, ceftazidime, oxacillin) than were the conjunctivitis strains, and the conjunctivitis strains were more susceptible to antibiotics (chloramphenicol, azithromycin) than were the MK strains [12]. MK strains from Australia were more susceptible to antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, oxacillin) compared to MK strains from USA [12]. Whilst several studies have examined which virulence factors might be involved in the development of keratitis by S. aureus, there is much less information on the association of virulence factors with conjunctivitis or niCIE [13]. Similarly, as outlined previously [13], infectious isolates (MK + conjunctivitis) had a higher frequency of genes involved in evasion of the immune system and invasion of the host (hlg, hld) compared to niCIE strains. On the other hand, scpA, that encodes a staphylococcal cysteine proteinase, was more common in niCIE strains. However, those previous studies only examined a subset of genes, specifically those that had been previously reported to be involved in infections of the eye or antibiotic resistance. This current study examines the whole genome of a subset of strains isolated from MK, conjunctivitis, and niCIE. This analysis may identify new genes that are associated with particular infections or resistance to antibiotics.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is a widely used technique that can identify antibiotic resistance genes, virulence determinants, emerging bacterial lineages, and their population structures [14,15,16]. Comparative genomics and genome-wide association studies of clinical isolates can reveal genetic determinants that may be important in the setting of specific infections. For example, WGS has been used successfully to examine S. aureus isolates collected from systemic infections (bloodstream, airways, endocarditis, and joint infections) to further understand specific population structures as well as to explore the relationship between virulence factors and patient outcomes [16,17,18,19].

WGS of S. aureus strains isolated from different infections (airways, soft-tissues, and skin lesions) showed high level of diversity and co-presence of local, global, livestock-associated, and hypervirulent clones and found that some virulence factors and clones were disease specific. For example, the sequence type ST22 was associated with toxic shock syndrome toxin TSST-1 and ST5 was associated with enterotoxins (SE) [18]. Another study explored genomic relatedness between commensal nasal isolates and those isolated from prosthetic joint infections and found the commensals shared the same clonal complex (CC) and the prevalence of virulence genes among isolates from commensal and prosthetic joint infections in arthroplasty patients was almost equal, suggesting that commensal S. aureus nasal clones can cause joint infections [19].

In the current study, WGS was used to analyze 25 S. aureus strains from ocular infectious and niCIEs isolated from USA and Australia. A custom analytical pipeline determined MLST, to define circulating S. aureus ocular lineages in infectious and non-infectious strains from USA and Australia, as well as the presence or absence of 128 known S. aureus virulence factors. The ocular strains were then compared to 10 fully sequenced non-ocular strains to determine the key virulence factors involved in ocular diseases.

2. Results

2.1. General Features of the Genomes

After de novo assembly, the isolates had different numbers of contigs ranging from 328 for SA31 to 3916 for SA86. Isolates had an average guanine plus cytosine (GC) content of 32.8%. The tRNA copy number for the isolates ranged from 60 to 89. Similarly, the number of coding sequences (CDS), which was determined based on Prokka annotation pipeline, ranged from 2614 (in M19-01) to 3873 (SA86). The general features of isolates are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genetic features of the S. aureus isolates.

| Ocular Condition | S. aureus Isolates | Region | GC Content (%) | No. of Contigs | Total Sequence Length (bp) | CDSs (Total) | tRNAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial keratitis | SA107 | USA | 32.8 | 1173 | 3,599,003 | 3302 | 71 |

| SA111 | 33 | 655 | 3,113,006 | 2858 | 85 | ||

| SA112 | 32.9 | 614 | 3,170,760 | 2930 | 74 | ||

| SA113 | 32.8 | 530 | 3,014,859 | 2771 | 72 | ||

| SA114 | 32.9 | 1332 | 3,175,242 | 2877 | 60 | ||

| SA34 | AUS | 32.9 | 349 | 2,914,342 | 2694 | 60 | |

| SA129 | 32.9 | 694 | 3,105,791 | 2897 | 66 | ||

| M5-01 | 32.9 | 624 | 2,975,620 | 2701 | 85 | ||

| M19-01 | 33 | 429 | 2,893,905 | 2614 | 77 | ||

| M28-01 | 32.8 | 475 | 2,960,866 | 2715 | 62 | ||

| M43-01 | 33.1 | 985 | 3,029,867 | 2741 | 89 | ||

| M71-01 | 32.9 | 536 | 2,918,758 | 2665 | 74 | ||

| Conjunctivitis | SA86 | USA | 32.9 | 3916 | 4,579,417 | 3873 | 76 |

| SA90 | 32.8 | 404 | 3,015,554 | 2755 | 62 | ||

| SA101 | 32.6 | 998 | 3,602,977 | 3296 | 63 | ||

| SA102 | 32.8 | 1067 | 3,406,253 | 3085 | 65 | ||

| SA103 | 32.9 | 479 | 3,069,147 | 2857 | 72 | ||

| SA46 | AUS | 32.9 | 388 | 2,903,724 | 2646 | 62 | |

| SA136 | 32.8 | 735 | 3,035,909 | 2803 | 76 | ||

| niCIE | SA20 | AUS | 32.8 | 385 | 2,909,603 | 2660 | 61 |

| SA25 | 32.8 | 366 | 2,907,754 | 2622 | 61 | ||

| SA27 | 32.8 | 345 | 2,919,830 | 2686 | 67 | ||

| SA31 | 32.8 | 328 | 2,976,006 | 2782 | 60 | ||

| SA32 | 32.7 | 649 | 2,990,036 | 2665 | 65 | ||

| SA48 | 32.8 | 338 | 2,922,947 | 2665 | 64 |

CDS = coding DNA sequence. Note: all strains had N50 values of 985.

2.2. Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

Eighteen different types of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes for various classes of antibiotics were detected in this study (Table 2). Antimicrobial resistance genes for vancomycin (vanA), fusidic acid (fusA, fusB), trimethoprim (dfrA, dfrB, dfrG), ciprofloxacin (gyrA, gyrlA, grlB), fosfomycin (fosB), and rifampin (rpoB) were not found in any of the strains. The beta lactamase resistance gene blaZ which encodes penicillin resistance was found in 76% of isolates. However, the methicillin resistance gene mecA was found in 28% of strains, all of which were from the USA; the possession of mecA was significantly more common in infectious isolates from USA than from Australia (p = 0.0016).

Table 2.

Acquired antimicrobial resistance genes in S. aureus isolates from different ocular conditions.

| Gene | USA Infectious Isolates (MK+ Conjunctivitis) | Australian Infectious Isolates (MK+ Conjunctivitis) | niCIE | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 107 | 111 | 112 | 113 | 114 | 86 | 90 | 101 | 102 | 103 | 34 | 129 | M5-01 | M19-01 | M28-01 | M43-01 | M71-01 | 46 | 136 | 20 | 25 | 27 | 31 | 32 | 48 | |

| Beta lactamase resistance gene | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| blaZ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mecA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aminoglycoside resistance gene | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| aac(6′) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| aph(2 ′) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ant(6)-la | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| aph(3′)-III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ant(9)-la | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| aadD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Macrolide, Lincosamide, Streptogramin B | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| erm(A) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| msr(A) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| erm(C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mph(C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tetracycline, chloramphenicol resistance genes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| tetK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| cat(pC233) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| tetM | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quaternary ammonium compounds | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| qacB | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| qacD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pseudomonic acid (Mupirocin) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mupA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Grey color represents the presence of the gene. Dark blue = USA MK strains, light blue = Australian MK strains; dark green = conjunctivitis USA strains, light green = conjunctivitis Australian strain, peach color = niCIE strains.

The aminoglycoside resistance genes were significantly more common (p = 0.0006) in strains from the USA, with only strain M28-01 isolated from MK in Australia possessing one of these genes, ant(9)-la. Genes associated with resistance to macrolides, lincosamide, or streptogramin B were significantly more likely to be found in USA isolates (p = 0.002), with only Australian isolates M28-01 possessing erm(A) and SA25 possessing erm(A), msr(A), and erm(C). Six isolates possessed tetK that encodes tetracycline resistance, and these were scattered across isolates from MK (2 USA, 1 Australian), conjunctivitis (1 USA) and niCIE (2 Australia). Resistance gene for tetracycline (tetM) and quaternary ammonium compound (qacD) were found in single isolate (USA) whereas pseudomonic acid (mupirocin) was present in only two USA isolates and quaternary ammonium compound qacB was found in single USA and single Australian isolate. Chloramphenicol resistance gene cat(pC233) was only found in a single Australian isolate (Table 2).

Overall, in Australian infectious isolates only five acquired antimicrobial resistance genes were detected. As the current study relied on draft genomes it may not be able to predict actual genomic diversity and could not detect actual antimicrobial resistance genes. There could be more genes, complete gene sequence of isolates can show the actual number of antimicrobial resistance genes. Similarly, USA infectious isolates had acquired 17 different antimicrobial resistance genes (Table 2). NiCIE isolates from Australia had acquired six different antimicrobial resistance genes. One USA infectious isolate, SA101, had the largest number of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes (eight).

2.3. S. aureus Virulence Determinants

Of the 128 virulence factors examined, 22 virulence genes (atl, ebh, clfA, clfB, cna, ebp, eap, efb, fnbA, fnbB, icaA, icaB, icaC, icaD, icaR, sdrC, sdrD, sdrE, sdrF, sdrG, sdrH, spa) in VFDB are categorized as genes involved in S. aureus adhesion. Of these adhesins, atl, ebp, eap, efb, fnbA, fnbB, icaA, icaB, icaC, icaR, sdrC, and spa were found in ≥96% of all S. aureus isolates. On the other hand, sdrF, sdrG, sdrH were not detected in any of the strains.

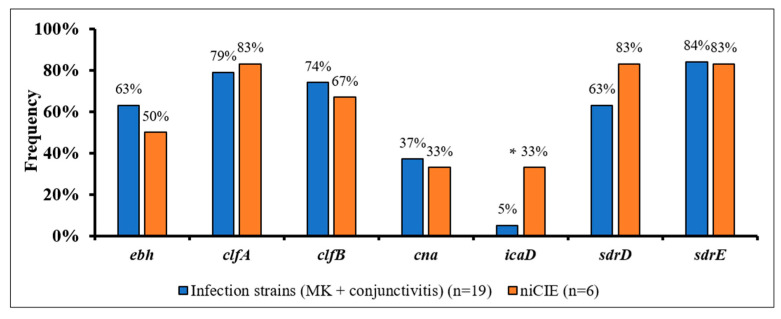

S. aureus strains from ocular infectious and niCIE showed non-significant differences in the frequency of possession of six adhesins (Figure 1), with only possession of icaD showing a trend towards being more common in niCIE isolates (p = 0.1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of seven virulence genes involved in S. aureus adhesion by disease group. *, trend to be more common in niCIE strains (p = 0.1).

When differences were examined for the possession of adhesins in the infectious isolates from different countries, there were no significant differences observed in MK and conjunctivitis isolates from USA and Australia.

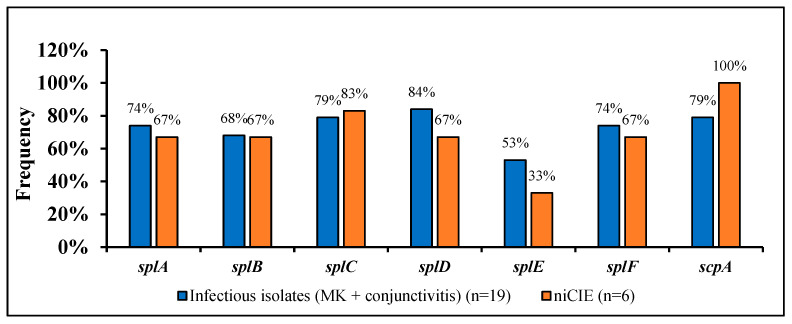

Of the remaining 106 virulence genes, 15 were categorized as enzymes in VFDB. These were genes for the cysteine proteases scpA and sspB, the serine proteases sspA, splA, splB, splC, slpD, splE, splF, hyaluronate lyase hysA, the lipases geh and lip, staphylocoagulase coa, staphylokinase sak and thermonuclease nuc. Of these genes, 67% (9/15; sspB, hysA, geh, lip, v8, sspA, sak, and nuc) were found in ≥96% of all S. aureus isolates. The isolates from infections or niCIEs isolates did not show significant differences (p > 0.05) or trend towards significance (p = 0.1), for the possession of other seven proteases, (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency of 7 proteases in S. aureus by disease group.

Similarly, the frequency of protease genes in strains isolated from MK or conjunctivitis was not significantly different, although conjunctivitis strains (100%) had a trend for more frequent presence of splA (p = 0.1) and splF (p = 0.1) than MK strains (58%). In infectious isolates (MK + conjunctivitis) from the USA, possession of splC (100% vs. 55%; p = 0.03) and splB (90% vs. 44%; p = 0.05) was higher and there was also a trend for higher possession of splD (100% vs. 66%; p = 0.08) and splA (100% vs. 55%; p = 0.1) compared to Australian isolates, except scpA (100% vs. 60%; p = 0.08) which was higher in infectious isolates (MK + conjunctivitis) from Australia.

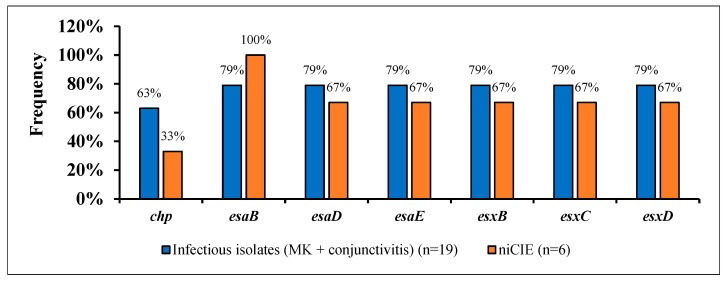

Of the remaining 91 virulence genes, five were involved in immune evasion (IE; adsA, chp, cpsA, scn, sbi), and 12 genes were involved in the type VII secretion systems (esaA, esaB, esaD, esaE, esaG, essA, essB, essC, esxA, esxB, esxC, esxD). Of these, 10/17 (adsA, cpsA, scn, sbi, esaA, esaG, essA, essB, essC, and esxA) were found in ≥96% of all S. aureus isolates. There were no significant differences or trends in possession of any IE or type VII secretion system genes by disease group or by country. Figure 3 shows the differences in possession of seven of these genes between infectious and niCIE isolates.

Figure 3.

Possession of 7 virulence genes involved in immune evasion and type VII secretion system in S. aureus by disease group.

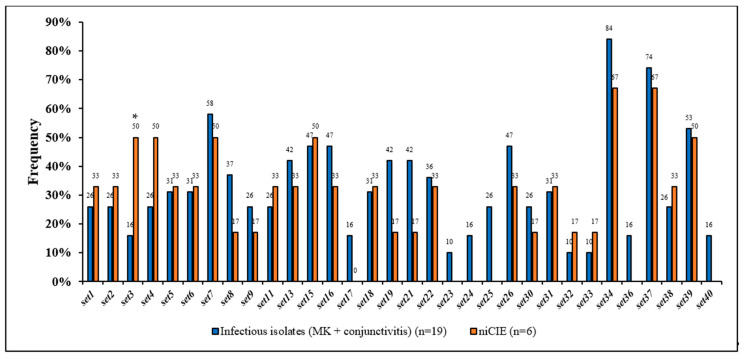

The remaining 74 virulence genes encoded for toxins including hemolysins (hla, hlb, hld, hlgA, hlgB, hlgC), enterotoxins (sea, seb, sec, sed, see, seg, seh, sei, sej, yent1, yent2, selk, sell, selm, seln, selo, selp, selq, selr, selu), exfoliative toxins (eta, etb, etc, etd), exotoxins, also known as enterotoxin like genes, (set1, set2, set3, set4, set5, set6, set7, set8, set9, set10, set11, set12, set13, set14, set15, set16, set17, set18, set19, set20, set21, set22, set23, set24, set25, set26, set30, set31, set32, set33, set34, set35, set36, set37, set38, set39, set40), leukocidins (lukF-like, lukM, lukD, lukE, lukf-PV, lukS-PV), and toxic shock syndrome toxin (tsst).

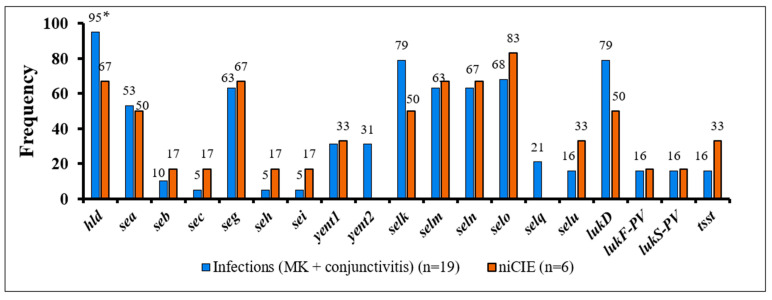

Of these, the hemolysins hla, hlgA, hlgB, hlgC were found in ≥96% of all S. aureus isolates. Of the remaining 70 toxins, sed, see, sej, selp, selr, eta, etb, etc, etd, set10, set12, set14, set20, lukM were not detected in any of the isolates, and hlb, sell, set35, lukF-like, lukE were present only in 4% of all S. aureus isolates. However, 51 toxins showed some differences between S. aureus infectious and niCIE isolates (Figure 4). Of these the only significant differences or trends for differences were as follows: niCIE isolates tended to have a higher frequency (50%) of only set3 (p = 0.1) (Figure 4) than infectious isolates (16%), and infectious isolates tended to have a higher frequency (95%) of only hld (p = 0.1) than niCIE (67%) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Frequency of 32 enterotoxin-like genes in S. aureus by disease group. *, trend more common in niCIE strains (p = 0.1).

Figure 5.

Frequency of 19 enterotoxins, exfoliative toxins and tsst in S. aureus by disease group. *, trend more common in infectious strains (p = 0.1).

Overall conjunctivitis strains were more likely to possess set36 (43% vs. 0%; p = 0.03), set38 (57% vs. 8%; p = 0.03), set40 (43% vs. 0%; p = 0.03), lukF-PV (43% vs. 0%; p = 0.03), lukS-PV (43% vs. 0%; p = 0.03), with a trend for set31 (57% vs. 17%; p = 0.1) than MK strains. These 51 toxins were also examined for differences in the isolate’s country of origin. The only differences were for MK strains, where isolates from the USA had a significantly higher frequency of possession of yent1 (60% vs. 0%; p = 0.04), set9 (60% vs. 0%; p = 0.04), and set11 (60% vs. 0%; p = 0.04) than MK isolates from Australia.

The VFDB results of these 25 ocular isolates were compared with previously published non-ocular isolates for the possession of the 128 virulence determinants. Eight genes involved in adhesion (ebp, eap, efb, fnbA, fnbB, icaA, icaR, sdrC) were found in all ocular and non-ocular S. aureus isolates and three (sdrF, sdrG, sdrH) were not found in any isolate. S. aureus ocular isolates showed higher frequency for the possession of cna (40% vs. 0%; p = 0.03) and icaR (100% vs. 70%; p = 0.01) whereas non-ocular isolates showed higher frequency for the possession of icaD (60% vs. 12%; p = 0.007), ebh (90% vs. 60%; p = 0.1), and sdrD (100% vs. 68%; p = 0.07). Of 15 enzymes, 9 (spa, sspB, sspC, hysA, geh, lip, sspA, coa, nuc) were found in all S. aureus isolates and no significant differences (or trends) were found in the possession of any other enzyme-associated gene. Similarly, all five (adsA, cpsA, scn, sbi, chp) genes involved in immune evasion were found in all isolates. Six (esaA, esaB, esaG, essA, essB, esxA) of the genes involved in type VII secretion system were found in ≥96% of all S. aureus isolates, with non-significant differences in frequency of possession of the remaining six, type VII secretion system gene, esaD (80% vs. 100%; p = 0.29), esaE (80% vs. 100%; p = 0.29), essC (92% vs. 100%; p = 0.99), esxB (76% vs. 100%; p = 0.15), esxC (76% vs. 100%; p = 0.15), esxD (76% vs. 100%; p = 0.15) in ocular and non-ocular isolates respectively.

Of 74 toxins, four hemolysin genes (hla, hlgA, hlgB, hlgC) were found in ≥96% of all S. aureus isolates and 18 toxin genes (hlb, sed, see, sej, selp, selr, eta, etb, etc, etd, set10, set12, set14, set20, set35, lukF-like, lukM, lukE) were found in ≤4% of all strains. Of the remaining 52 toxins, S. aureus ocular isolates possessed sea (80% vs. 20%; p = 0.001), set1 (28% vs. 0%; p = 0.08), set5 (32% vs. 0%; p = 0.07), set16 (44% vs. 0%; p = 0.01), set19 (36% vs. 0%; p = 0.03), whereas non-ocular isolates possessed selq (30% vs. 0%; p = 0.018), set30 (70% vs. 24%; p = 0.01), set32 (50% vs. 12%; p = 0.02), set36 (50% vs. 12%; p = 0.02), set37 (100% vs. 72%; p < 0.0001), lukD (100% vs. 72%; p < 0.0001), lukF-PV (60% vs. 16%; p = 0.001), and lukS-PV (60% vs. 16%; p = 0.001).

2.4. Sequence Types and Clonal Complexes of S. aureus Isolates

The MLST typing of 25 S. aureus genomes revealed a total of 14 distinct sequence types (STs) and seven clonal complexes (Table 3), ST5 (n = 5, 20%) and ST8 (n = 4, 16%) were the most common sequence types in this cohort of ocular isolates. For strain M19-01, no ST type was identified, and was named as NI (Table 3). In the current study most of the USA isolates were from CC5 or CC8, whereas there was a greater spread of sequence types and clonal complexes in the Australian isolates.

Table 3.

Sequence types and clonal complexes of S. aureus isolates.

| S. aureus Isolates | Sequence Type | Clonal Complex | Number of: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Genes | Shell Genes | Pan/Total Genes | |||

| 107 | 15 | CC15 | 2392 | 1187 | 3579 |

| 111 | 105 | CC5 | 2382 | 770 | 3152 |

| 112 | 5 | CC5 | 2380 | 841 | 3221 |

| 113 | 105 | CC5 | 2330 | 782 | 3112 |

| 114 | 30 | CC30 | 2168 | 129 | 3377 |

| 86 | 840 | CC5 | 1984 | 2577 | 4561 |

| 90 | 5 | CC5 | 2342 | 739 | 3089 |

| 101 | 8 | CC8 | 2533 | 898 | 3431 |

| 102 | 8 | CC8 | 2497 | 760 | 3257 |

| 103 | 8 | CC8 | 2514 | 498 | 3012 |

| 34 | 508 | CC45 | 2194 | 974 | 3168 |

| 129 | 34 | CC30 | 2227 | 1112 | 3339 |

| M5-01 | 188 | CC1 | 2267 | 844 | 3111 |

| M19-01 | NI | NI | 2302 | 684 | 2986 |

| M28-01 | 109 | CC1 | 2304 | 775 | 3079 |

| M43-01 | 672 | NI | 2296 | 827 | 3123 |

| M71-01 | 97 | CC97 | 2315 | 705 | 3020 |

| 46 | 5 | CC5 | 2325 | 664 | 2989 |

| 136 | 188 | CC1 | 2328 | 821 | 3149 |

| 20 | 121 | NI | 2252 | 824 | 3076 |

| 25 | 5 | CC5 | 2341 | 608 | 2949 |

| 27 | 39 | CC30 | 2180 | 996 | 3176 |

| 31 | 34 | CC30 | 2220 | 1010 | 3230 |

| 32 | 8 | CC8 | 2416 | 501 | 2917 |

| 48 | 5 | CC5 | 2300 | 736 | 3036 |

NI = not identified. Isolates highlighted in shades of blue indicate MK strains; dark blue represents MK strains from USA and light blue represents MK strains from Australia. Shades of green indicate conjunctivitis strains; dark green indicates conjunctivitis strains from USA and light green indicates conjunctivitis strains from Australia. The peach color indicates strains from niCIE.

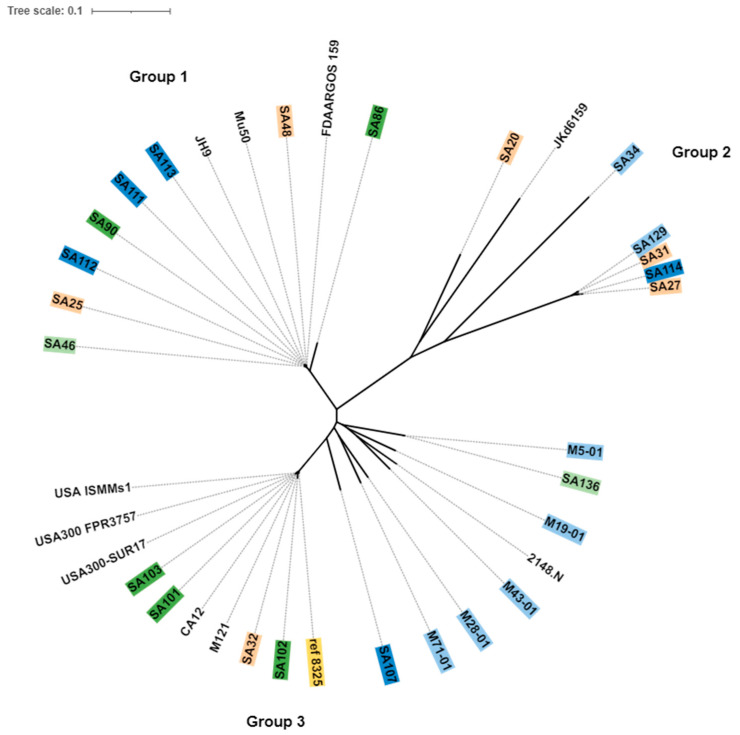

The core, shell (genes present in two or more strains), and pan genes of published isolates are provided in Supplementary Table S1. The core genes were used to create a phylogenetic tree of the S. aureus isolates using S. aureus NCTC 8325 (NC_007795.1) as a reference strain. The ten published non-ocular S. aureus isolates downloaded from the Genebank database were also included. Isolates of the same clonal complex or same sequence type were grouped together in the same cluster irrespective of their ocular condition or country of origin (Figure 6). The core genomes formed three groups in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 6). Isolates in Group 1 were related, as they belonged to the same CC5. This group also contained all the extensively-drug resistant isolates (XDR: resistant to almost all antibiotics) (SA111, SA112, SA113) and three multi-drug resistant (MDR: resistant to three different classes of antibiotics) isolates (SA90, SA48, SA46) reported in the previous study [12]. Isolates from CC30 in Group 2 were further clustered into two sub-lineages based on their core genes and STs. Group 3 was larger and contained the majority of MDR strains. Australian strains clustered into sub lineages within group 3, whereas USA isolates with same ST8 clustered together within group 3.

Figure 6.

Core genome phylogeny of S. aureus, using Parsnp. S. aureus strain NCTC 8325, was used as a reference strain (yellow). Isolates highlighted in shades of green indicate conjunctivitis strains; dark green indicates conjunctivitis strains from USA and light green indicates conjunctivitis strains from Australia. Shades of blue indicate MK strains; dark blue represents MK strains from USA and light blue represents MK strains from Australia. The peach color indicates strains from niCIE and strains with no color indicate non-ocular isolates. The tree was constructed using online webtool itol (interactive tree of life, https://itol.embl.de/ (accessed on 4 April 2022).

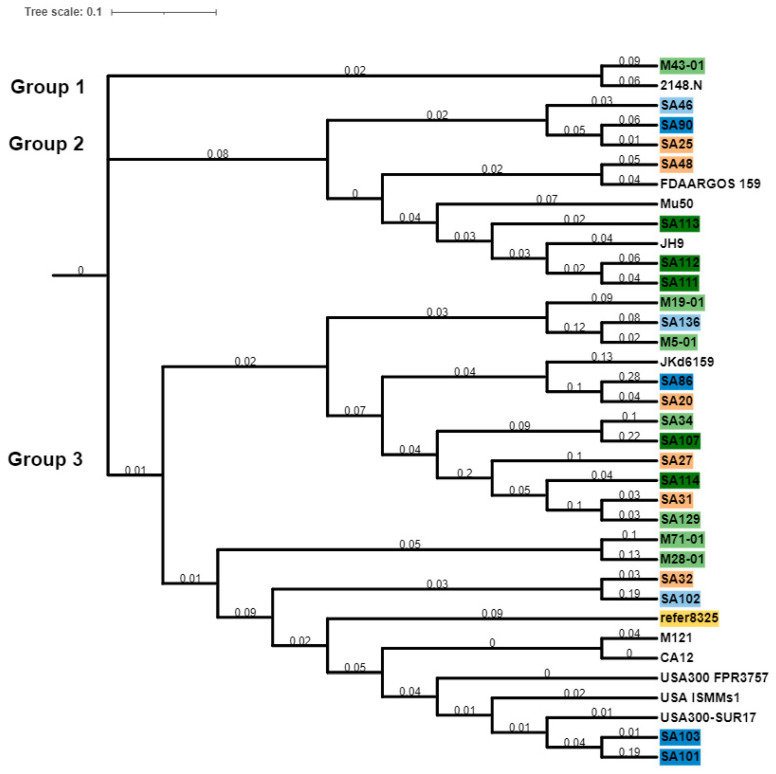

The pan phylogenetic relationships of these S. aureus isolates were assessed (Figure 7). This divided the S. aureus isolates into three major groups. Group 1 of the pan genome phylogeny contained only two isolates, ocular isolate M43-01 and a non-ocular isolate of the same clonal complex. The second group included isolates with the same clonal complex, and XDR (resistant to almost all antibiotics) and MDR (resistant to three different classes of antibiotics) strains, irrespective of their ocular condition and country of origin. Group 3 was further divided into two subgroups; isolates with the same pangenome and CC or ST were clustered together. Isolates in group 3 had a large number of pan genes. Isolates belonging to the same sequence type or clonal complex were grouped together, for example, isolates 129, 31, 114, 27 were from clonal complex 30.

Figure 7.

Pan genome phylogeny of S. aureus isolates. S. aureus strain NCTC 8325 was used as a reference strain (yellow color). Isolates in shades of green are conjunctivitis strains; dark green indicates conjunctivitis strains from USA, and light green conjunctivitis strains from Australia. Shades of blue indicate MK strains; dark blue represents MK strains from USA and light blue represents MK strains from Australia. Isolates in peach color are strains from niCIE and those with no color are non-ocular isolates. The tree was constructed using online webtool itol (interactive tree of life, https://itol.embl.de/, (accessed on 4 April 2022). The tree scale indicates differences between the isolates and branch length indicates the number of changes that have occurred in that branch.

3. Discussion

This study investigated genomic differences in resistance and virulence genes of S. aureus isolates from different infectious (MK and conjunctivitis) and non-infectious (niCIE) ocular conditions from USA and Australia. Based on previous phenotypic susceptibility [12] and PCR data [13] it was expected that there would be differences in the resistance and virulence determinants between infectious and non-infectious disease. Most (n = 22, 88%) of the isolates used in the study were MDR [12]. Phenotypically non-infectious (niCIE) isolates in a previous study were more susceptible to antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, ceftazidime and oxacillin) than conjunctivitis and MK strains, and MK isolates from USA were more resistant to antibiotics than MK isolates from Australia (ciprofloxacin, ceftazidime and oxacillin) [12]. The current study’s genotypic data shows that infectious isolates from USA harbored more antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) compared to Australian isolates, which supports the phenotypic data of the previous study. Similarly, PCR results for a subset of 12 known virulence genes had previously reported that genes involved in evasion and invasion (hlg and hld) were more commonly found in infectious isolates than niCIE [13]. The current study results for hld are consistent with the previous report [13]. However, hlg which was more common in infectious strains than niCIE strains in the previous study [13] was found in ≥96% of all S. aureus isolates in the current study. In addition, due to the selection of isolates in the current study, staphylococcal cysteine proteinase scpA, which was more common in niCIE isolates than infectious strains [13] in the previous study, whilst being more commonly observed in niCIE strains than infectious strains in the current study, did not reach significance (100% vs. 79%, p = 0.28).

Overall, 76% of all strains possessed the acquired penicillin resistance gene blaZ but only 28% of strains, all from USA infectious (MK+ conjunctivitis), possessed mecA (i.e., were MRSA). The high level of MRSA among S. aureus ocular isolates from USA in the current study is consistent with previous studies [20,21]. The current study reports low level of MRSA among ocular isolates from Australia which supports previous studies showing low rates (≤6.3%) of MRSA among S. aureus ocular isolates from Australia [12,22].

The aminoglycoside resistance genes aac (6′) and aph (2′), which encode for gentamicin resistance, were found in only one isolate from USA which is consistent with phenotypic susceptibility [12] and other previous studies from USA and Australia [22,23,24] which suggest gentamicin remains a good option to treat S. aureus ocular infections in both Australia and USA. Genes ant (6)-la, aph (3′) III, which encode for streptomycin resistance, were found in three USA isolates but in none of the Australian isolates. Streptomycin is no longer used in clinical treatment [25], so this resistance may not be clinically relevant but does suggest environmental selection for the persistence of genes. Gene ant (9)-la, which confers resistance to spectinomycin, was found in four USA isolates (three were MRSA) and one isolate from Australia. Several previous reports showed an association between aminoglycoside resistance and methicillin resistance [26,27]. Gene aadD, which is responsible for resistance to kanamycin/neomycin and tobramycin [28], was found in four USA isolates.

Strains from niCIE showed a trend of higher frequency possession of icaD, the intercellular adhesion gene, is involved in biofilm production [29]. As niCIE are associated with contact lens wear and contact lenses may provide a surface where bacteria can attach and colonize as a biofilm [30], it is perhaps not surprising that possession of icaD was more common in niCIE isolates and suggests that biofilm formation mediated by this gene is not critical for ocular surface infection (i.e., MK or conjunctivitis). In the current study when ocular isolates were compared to non-ocular isolates, they showed higher frequency for the possession of cna (40% vs. 0%; p = 0.03) and icaR (100% vs. 70%; p = 0.01), whereas non-ocular isolates showed higher frequency for the possession of icaD (60% vs. 12%; p = 0.007), ebh (90% vs. 60%; p = 0.1), and sdrD (100% vs. 68%; p = 0.07). The product of cna, collagen binding adhesin, has been reported to be involved in the pathogenesis of S. aureus keratitis [31] and the possession of this gene in ocular strains in the current study confirms that it may be an important virulence determinant in S. aureus ocular infections. Gene icaR is a strong negative regulator of biofilm formation, and its absence enhances PNAG (poly-N-acetylglucosamine) production and biofilm formation [32,33]. Ocular strains used in this study are enriched with icaR which further suggests biofilm formation is not an absolute requirement for S. aureus ocular infections.

Non-ocular strains in the current study were enriched with icaD which is involved in biofilm production [29]; this suggests that biofilm formation is important for their non-ocular pathogenesis. Gene ebh is a cell wall-associated fibronectin binding protein [34] which helps S. aureus to adhere to host extracellular matrix (ECM) and plays a role in cell growth, envelope assembly [35] while contributing to structural homeostasis of bacterium by forming a bridge between the cell wall and cytoplasmic membrane [36]. The lower frequency of ebh possession in S. aureus ocular strains suggests it has a minor role in eye infections. Gene ebh is produced during human blood infection, as serum samples taken from patients with confirmed S. aureus infection were found to contain anti-ebh antibodies. Gene sdrD (serine–aspartate repeat protein D) is member of the MSCRAMMs (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules) [37], promotes the adherence of S. aureus to nasal epithelial cells [38], human keratinocytes [39], and contributes to abscess formation [40]. A high prevalence of S. aureus sdrD gene is reported among patients with bone infections [41] which suggests that sdrD may contribute to systemic infection. sdrD is also reported to aid the pathogen in immune evasion by increasing S. aureus virulence and survival in blood [40]. The lower frequency of possession of this gene in ocular isolates indicates sdrD may not be involved in pathogenesis of currently prevalent types of eye infections, however, S. aureus with sdrD could contribute more to eye infection.

Overall, isolates from conjunctivitis had a higher frequency for possession of the serine proteases splA and splF than isolates from MK. Infectious isolates from USA were significantly, or trended to be more likely to, possess the proteases splC splA, splB, and splD than infectious isolates from Australia. Serine proteases are encoded on the νSaβ pathogenicity island [42,43]. The spl operon is present in most of S. aureus strains but some strains may not have the full operon [44]. Previous studies suggest that serine proteases are expressed during human infections and modulate S. aureus physiology and virulence [45], but their role in ocular infections is unknown. The current study suggests that some of these serine proteases may have a role in pathogenesis of conjunctivitis, and this should be studied in future experiments. Again, the trend of pathogenic isolates from USA infections to possess other serine proteases might be related to the different clonal types circulating in the USA. Studies reported ST5 (27%), ST8 (16%), ST30 (9%), and ST45 (6%) as prevalent clonal types in USA ocular isolates [46]. However, a study from tropical northern Australia reported CC75 as a prevalent clone in Australia [47]. In the current study 50% of infectious strains possessing serine proteases were CC5 (ST5, ST105, and ST840), 30% were CC8 (ST8), and 10% were CC15 (ST15) and CC30 (ST30). All strains from CC5 and CC30 possessed 4−6 proteases whereas strains from CC8 and CC15 possessed all six proteases. There was a greater spread of sequence types and clonal complexes in the Australian infectious isolates.

There were several differences in possession of toxins genes of the set family and others. The set genes are similar to staphylococcal superantigens but more likely to be involved in immune avoidance [48]. Several toxins in staphylococci are often carried on large mobile genetic elements (MGEs) known as pathogenicity islands that can be horizontally transferred [49] and can be located on the pathogenicity island SaPIn2, SaPIl, and SaPIboy [50]. An increasing number of enterotoxins and enterotoxin-like genes in S. aureus have been identified and it is a global trend that around 80% of S. aureus both pathogenic and non-pathogenic isolates carry an average of 5−6 enterotoxin genes [51,52,53]. Whether the set genes in different strains were present on pathogenicity islands will be examined in future studies.

The current study’s finding that enterotoxin E (sea) was more commonly found in ocular strains, infectious strains from USA (70%), AUS (33%), niCIE strains (50%) than non-ocular strains (20%), however, the current study findings are not consistent with earlier studies [54,55]. S. aureus strains isolated from atopic patients experiencing keratoconjunctivitis with corneal ulceration, possessed enterotoxins more frequently compared to patients with no ulceration [56]; the role of enterotoxins in ocular infections remains to be fully defined. Another study found enterotoxin and enterotoxin-like genes were found to be highly correlated with MRSA and predictive for MDR status in ocular isolates [57]. The antibiotic susceptibility data of the isolates used in the current study shows that most of the strains were multi-drug resistant (MDR) [12], so the distribution of enterotoxin-like genes in 28% of MRSA USA infectious strains (MK + conjunctivitis) may indicate their MDR status, but the presence of enterotoxin-like genes in MSSA (methicillin sensitive S. aureus) MDR strains from other conditions indicates enterotoxin genes are probably associated with the source of isolation. The genes lukF-PV and lukS-PV encode for the Panton–Valentine leukocidin which is linked to community acquired MRSA infections [58]. Their presence in conjunctivitis strains from USA (60%) in the current study supports previous studies which reported that Panton–Valentine leukocidin (pvl) is found in the majority of (67%) ocular strains [59].

The finding that there were no differences in the possession of genes related to immune evasion or type VII secretion systems (adsA, chp, cpsA, scn, sbi, esaA, esaB, esaD, esaE, esaG, essA, essB, essC, esxA, esxB, esxC, esxD) between different isolate types, countries, or ocular and non-ocular strains, and the finding that most isolates possessed the adhesin genes atl, ebp, eap, efb, fnbA, fnbB, icaA, icaB, icaC, icaR, sdrC, and spa, the enzyme genes (proteases, thermonuclease, lipase, staphylokinase, and hyaluronate lyase) sspB, scpA, hysA, geh, lip, v8, sspA, sak, and nuc, and the hemolysin genes hla, hlgA, hlgB, hlgC might indicate that possession of these genes is important either for survival in either the eye or in the environment prior to gaining access to the ocular surface to cause infection or inflammation.

The core and pan genome phylogenies included strains from all ocular conditions. Acquired genes are part of the pan rather than core genome [60] and the presence of larger pan genomes points towards the acquisition of new genes [61]. The core genome (which is almost 90% of pan or total genome) refers to the conserved genes present in a species, which might differ in each individual strain within that species [62]. With respect to multi-locus sequence typing, in the current study sequence types (STs), ST5 (20%), ST8 (16%), clonal complex (CC), CC30 (16%), and CC1 (12%) were the most prevalent (predominant) types respectively. Previous studies identified that specific lineages including ST5 and ST8 are common among S. aureus ocular strains [54,59,63,64,65]. ST5 MRSA isolates from USA were the frequent cause of hospital acquired infections [66] and ST8 MRSA isolates from USA most commonly the causes of community acquired skin and soft tissue infections [67,68]. This suggests that S. aureus isolates from ocular infections align with major circulating pathogenic S. aureus strains capable of causing systemic infections.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Isolates

Twenty-five S. aureus ocular isolates, 9 isolated from infections (MK + conjunctivitis) in Australia, 10 isolated from infections (MK + conjunctivitis) in USA and 6 isolated from niCIEs in Australia were used (Table 4). The isolates were selected from a larger collection of strains based on their published susceptibility to various antibiotics [12] and possession of virulence genes [13]. Most strains were multi-drug resistant (MDR; Table 4).

Table 4.

| Ocular Condition | Stain Number | Phenotypic Resistance (R) and Susceptibility (S) Profile | Profile of Virulence Genes Known to Be Possessed by the Isolates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial keratitis USA | SA107 | CIP, CEFT, OXA, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, CHL (S) |

fnbpA, eap, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld. |

| SA111 | CIP, CEFT, OXA, GN, AZI, POLYB (R) VAN, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld | |

| SA112 | CIP, CEFT, OXA, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld | |

| SA113 | CIP, CEFT, OXA, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld | |

| SA114 | CIP, CEFT, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, OXA, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld | |

| Microbial keratitis Australia | SA34 | CEFT, AZI, POLYB (R) CIP, GN, VAN, OXA, CHL (S) |

fnbpA, eap, scpAsspB, sspA, coa, seb, hla, hlg, hld |

| SA129 | CEFT, CHL, AZI, POLYB (R) CIP, GN, VAN, OXA (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld | |

| M5-01 | CIP, CEFT, CHL, AZI (R) GN, VAN, OXA, POLYB (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld | |

| M19-01 | CEFT, AZI, POLYB (R) CIP, GN, VAN, OXA, CHL (S) |

fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld | |

| M28-01 | CEFT, CHL, AZI, POLYB (R) CIP, GN, VAN, OXA (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld | |

| M43-01 | CIP, CEFT, OXA, CHL, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN (S) |

clfA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld | |

| M71-01 | CIP, CEFT, CHL, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, OXA (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld | |

| Conjunctivitis USA | SA86 | CEFT, CHL, AZI, POLYB (R) CIP, GN, VAN, OXA (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, coa, seb, hla, hlg, hld, pvl. |

| SA90 | CIP, CEFT, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, OXA, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, coa, hla, hlg, hld. | |

| SA101 | CIP, CEFT, OXA, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld, pvl | |

| SA102 | CIP, CEFT, OXA, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, sspB, sspA, coa, seb, hla, hlg, hld. | |

| SA103 | CIP, CEFT, OXA, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld, pvl | |

| Conjunctivitis Australia | SA46 | AZI, POLYB (R) CIP, CEFT, OXA, GN, VAN, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld. |

| SA136 | CIP, CEFT, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, OXA, CHL (S) |

fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld. | |

| niCIE Australia | SA20 | CEFT, CHL, AZI, POLYB (R) CIP, GN, VAN, OXA (S) |

fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, seb, hla, hlg, pvl. |

| SA25 | AZI, POLYB (R)CIP, CEFT, GN, VAN, OXA, CHL (S) | clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, seb, hla, hlg, hld. | |

| SA27 | CEFT, OXA, AZI, POLYB (R) CIP, GN, VAN, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld. | |

| SA31 | CIP, CEFT, AZI, POLYB (R) GN, VAN, OXA, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld. | |

| SA32 | POLYB (R) CIP, CEFT, AZI, GN, VAN, OXA, CHL (S) |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg, hld. | |

| SA48 | CEFT, CHL, AZI, POLYB (R) CIP, GN, VAN, OXA (S). |

clfA, fnbpA, eap, scpA, sspB, sspA, coa, hla, hlg. |

R = resistant, S = sensitive; CIP = ciprofloxacin, CEFT = ceftazidime, OXA = oxacillin, GN = gentamicin, VAN = vancomycin, CHL = chloramphenicol, AZI = azithromycin, POLYB = polymyxin B. clfA = clumping factor, fnbpA = fibronectin binding protein, eap = extracellular adhesion protein, scpA = cysteine protease staphopain A, sspB = cysteine protease staphopain B, sspA = serine protease v8, coa = collagen binding adhesion, seb = enterotoxin, hla = alpha-toxin, hlg = gamma-toxin, hld = delta-toxin, pvl = Panton–Valentine leukocidin.

4.2. Whole Genome Sequencing

Genomic DNA from each S. aureus strain was extracted using QIAGEN DNeasy blood and tissue extraction kit (Hilden, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to prepare paired-end libraries. All the libraries were multiplexed on one MiSeq run. FastQC version 0.117 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc, accessed on 9 July 2021) was used to assess the quality of sequenced genomes using raw reads. Trimmomatic v0.38 (http://www.usadellab.org/cms/?page=trimmomatic, accessed on 9 July 2021) was used for trimming the adapters from the reads with the setting of minimum read length of 36 and minimum coverage of 15 [69]. De novo assembly using Spades v3.15.0 was performed using the default setting [70]. Assembled genomes were annotated with Prokka v1.12 using GeneBank® compliance flag [71]. The genome of S. aureus NCTC 8325 (reference strain in this study) was re-annotated with Prokka to avoid annotation bias.

Multi-locus sequence type (MLST) was determined using PubMLST (https://pubmlst.org/, accessed on 29 September 2021) [72] to find the sequence of each strain. Pan genomes of the S. aureus isolates were analyzed using Roary v3.11.2 [73] which uses the GFF3 files produced by Prokka. The program was run using the default settings, which uses BLASTp for all-against-all comparison with 95% of percentage sequence identity. Core genes were taken as the genes which were common in at least 99% of strains. Core genome phylogeny was constructed using Harvest Suite Parsnp v1.2 [74] with S. aureus NCTC 8325 (NC_007795.1) as a reference strain. The output file ‘genes_ presence_absence.csv’ generated by Roary was used to compare the S. aureus isolates. Phylogenetic tree was constructed using online webtool itol (https://itol.embl.de/, accessed on 4 April 2022). Acquired antibiotic resistance genes of S. aureus isolates were examined by using the online database Resfinder v3.1 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/, accessed on 30 October 2021) [75]. To determine the association of specific virulence determinants with specific ocular conditions, 128 virulence factors previously described to be associated with many S. aureus infections in the virulence factors database (VFDB) were examined (VFDB; Centre for Genomic Epidemiology, DTU, Denmark, http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/main.htm, (accessed on 9 May 2022) respectively [76]. The assembled S. aureus isolates were compared to a custom VFDB consisting of 128 virulence genes associated with adhesion, enzymes, immune evasion, type VII secretion systems, and toxins (enterotoxins, enterotoxin-like genes, exfoliative toxins, and exotoxins). A gene sequence had to cover at least 60% of the length of the gene sequence in the database with a sequence identity of 90% to be considered as being present in the strain. As acquired antimicrobial resistance genes may be carried on integrons, S. aureus genomes were analyzed for integrons using integron Finder version 1.5.1 (https://bioweb.pasteur.fr/packages/pack@Integron_Finder@1.5.1, accessed on 5 February 2022). There was no evidence for integrons in these 25 isolates. Isolates with the same sequence types were compared for nucleotide similarities using the MUMmer online web tool (http://jspecies.ribohost.com/jspeciesws/#analyse, accessed on 18 February 2022).

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Differences in virulence factors database (VFDB) results for the presence or absence of virulence genes between the disease groups and differences in ocular and non-ocular isolates were analyzed using a chi-square test in GraphPad prism v8.0.2.263 for windows (San Diego, CA, USA, (www.graphpad.com, accessed on 1 June 2022). For all analyses a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and p-value < 0.1 was considered as trending towards significance.

Nucleotide accession: The nucleotide sequences are available in the Genebank under the Bio project accession number PRJNA859391 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA859391, accessed on 24 July 2022), (genomes accession number (JANHMY000000000, JANHMZ000000000, JANHNA000000000, JANHNB000000000, JANHNC000000000, JANHND000000000, JANHNE000000000, JANHNF000000000, JANHNG000000000, JANHNH000000000, JANHNI000000000, JANHNJ000000000, JANHNK000000000, JANHNL000000000, JANHNM000000000, JANHNN000000000, JANHNO000000000, JANHNP000000000, JANHNQ000000000, JANHNR000000000, JANHNS000000000, JANHNT000000000, JANHNU000000000, JANHNV000000000, JANHNW000000000).

5. Conclusions

With respect to virulence determinants distribution, there were some differences between ocular and non-ocular isolates and ocular infectious and niCIE isolates. The current study could not detect plasmids in any of the isolates, as it relied on draft genomes. Further studies including more strains will focus on improvement of the assembly and probe the WGS for possession of pathogenicity islands such as νSaβ, SaPIn2, SaPIl, and SaPIboy. Overall, these findings have extended our understanding of the genomic diversity of S. aureus in infectious and non-infectious ocular conditions. The information can be used to elucidate various mechanisms that would help combat virulent and drug resistant strains.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Darlene Miller, Bascom Palmer Institute, Miami (USA) and Monica Lahra, Prince of Wales Hospital Sydney, for providing S. aureus MK strains. The authors would also like to acknowledge Associate Scott Rice and Stephen Summers and genome facility of the Singapore Centre of Life Science Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for providing the sequencing. We are also thankful to UNSW high performance computing facility KATANA for providing us with the cluster time for the data analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antibiotics11081011/s1, Table S1: Genomic features of S. aureus non-ocular isolates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., M.D.P.W., F.S. and A.K.V.; methodology, M.A., M.D.P.W., F.S. and A.K.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.D.P.W., F.S. and A.K.V.; supervision, M.D.P.W., F.S. and A.K.V.; funding acquisition, M.D.P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

S. aureus strains from the Bascom Palmer Institute, Miami (USA), were kindly provided by Dr. Darlene Miller. All strains were donated without identifiable patient data and ethics was not required to send or receive these strains. The more recent strains from the Prince of Wales Hospital (Australia) were kindly provided by Dr. Monica Lahra. Ethics was obtained (HREA Application ID: 2020/ETH02783), approval was required and obtained for these strains to be transferred to the School of Optometry and Vision Science, UNSW. No clinical data was provided that could be identified back to the patients from which the bacterial strains had been collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mainous A.G., III, Hueston W.J., Everett C.J., Diaz V.A. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus in the United States, 2001–2002. Ann. Fam. Med. 2006;4:132–137. doi: 10.1370/afm.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collier S.A., Gronostaj M.P., MacGurn A.K., Cope J.R., Awsumb K.L., Yoder J.S., Beach M.J. Estimated burden of keratitis-United States, 2010. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014;63:1027–1030. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields T., Sloane P.D. A comparison of eye problems in primary care and ophthalmology practices. Fam. Med. 1991;23:544–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green M., Carnt N., Apel A., Stapleton F. Queensland Microbial Keratitis Database: 2005-2015. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019;103:1481–1486. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mah F.S., Davidson R., Holland E.J., Hovanesian J., John T., Kanellopoulos J., Kim T. Current knowledge about and recommendations for ocular methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2014;40:1894–1908. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin H., Parker W.T., Law N.W., Clarke C.L., Gisseman J.D., Pflugfelder S.C., Al-Mohtaseb Z.N. Evolving risk factors and antibiotic sensitivity patterns for microbial keratitis at a large county hospital. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2017;101:1483–1487. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-310026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sand D., She R., Shulman I.A., Chen D.S., Schur M., Hsu H.Y. Microbial keratitis in los angeles: The doheny eye institute and the los angeles county hospital experience. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong V.W., Lai T.Y., Chi S.C., Lam D.S. Pediatric ocular surface infections: A 5-year review of demographics, clinical features, risk factors, microbiological results, and treatment. Cornea. 2011;30:995–1002. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31820770f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sweeney D.F., Jalbert I., Covey M., Sankaridurg P.R., Vajdic C., Holden B.A., Rao G.N. Clinical characterization of corneal infiltrative events observed with soft contact lens wear. Cornea. 2003;22:435–442. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otto M. Basis of virulence in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64:143–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung G.Y.C., Bae J.S., Otto M. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence. 2021;12:547–569. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1878688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Afzal M., Vijay A.K., Stapleton F., Willcox M. Susceptibilty of ocular Staphylococcus aureus to antibioticsand multipurpose disinfecting soutions. Antibiotics. 2021;10:1203. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10101203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Afzal M., Vijay A.K., Stapleton F., Willcox M. Virulence genes of Staphylococcus aureus associated with keratitis, conjunctivitis and contact lens-assocaied inflammation. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022;11:5. doi: 10.1167/tvst.11.7.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humphreys H., Coleman D.C. Contribution of whole-genome sequencing to understanding of the epidemiology and control of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019;102:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2019.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leopold S.R., Goering R.V., Witten A., Harmsen D., Mellmann A. Bacterial whole-genome sequencing revisited: Portable, scalable, and standardized analysis for typing and detection of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:2365–2370. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00262-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Recker M., Laabei M., Toleman M.S., Reuter S., Saunderson R.B., Blane B., Massey R.C. Clonal differences in Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia-associated mortality. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2:1381–1388. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lilje B., Rasmussen R.V., Dahl A., Stegger M., Skov R.L., Fowler V.G., Ng K.L., Kiil K., Larsen A.R., Petersen A., et al. Whole-genome sequencing of bloodstream Staphylococcus aureus isolates does not distinguish bacteraemia from endocarditis. Microb. Genom. 2017;3:e000138. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manara S., Pasolli E., Dolce D., Ravenni N., Campana S., Armanini F., Asnicar F., Mengoni A., Galli L., Montagnani C., et al. Whole-genome epidemiology, characterisation, and phylogenetic reconstruction of Staphylococcus aureus strains in a paediatric hospital. Genome Med. 2018;10:82. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0593-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wildeman P., Tevell S., Eriksson C., Lagos A.C., Söderquist B., Stenmark B. Genomic characterization and outcome of prosthetic joint infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:5938. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62751-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asbell P.A., DeCory H.H. Antibiotic resistance among bacterial conjunctival pathogens collected in the antibiotic resistance monitoring in ocular microorganisms (ARMOR) surveillance study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0205814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diekema D.J., Pfaller M.A., Schmitz F.J., Smayevsky J., Bell J., Jones R.N., Beach M., SENTRY Partcipants Group Survey of infections due to Staphylococcus species: Frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific region for the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (SARP), 1997–1999. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;32:114–132. doi: 10.1086/320184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabrera-Aguas M., Khoo P., George C.R.R., Lahra M.M., Watson S.L. Antimicrobial resistance trends in bacterial keratitis over 5 years in Sydney, Australia. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020;48:183–191. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coombs G.W., Bell J.M., Collignon P.J., Nimmo G.R., Christiansen K.J. Prevalence of MRSA strains among Staphylococcus aureus isolated from outpatients, 2006. Report from the Australian Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. Commun. Dis. Intell. Q. Rep. 2009;33:10–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwiecinski J., Jin T., Josefsson E. Surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus play an important role in experimental skin infection. Apmis. 2014;122:1240–1250. doi: 10.1111/apm.12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundin G.W., Bender C.L. Dissemination of the strA-strB streptomycin-resistance genes among commensal and pathogenic bacteria from humans, animals, and plants. Mol. Ecol. 1996;5:133–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.1996.tb00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khosravi A.D., Jenabi A., Montazeri E.A. Distribution of genes encoding resistance to aminoglycoside modifying enzymes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2017;33:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadegar A., Sattari M., Mozafari N.A., Goudarzi G.R. Prevalence of the genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and methicillin resistance among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus in Tehran, Iran. Microb. Drug Resist. 2009;15:109–113. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2009.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramirez M.S., Tolmasky M.E. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist. Updates. 2010;13:151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gad G.F., El-Feky M.A., El-Rehewy M.S., Hassan M.A., Abolella H., El-Baky R.M. Detection of icaA, icaD genes and biofilm production by Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis isolated from urinary tract catheterized patients. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2009;3:342–351. doi: 10.3855/jidc.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willcox M.D.P., Carnt N., Diec J., Naduvilath T., Evans V., Stapleton F., Holden B.A. Contact lens case contamination during daily wear of silicone hydrogels. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2010;87:456–464. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181e19eda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhem M.N., Lech E.M., Patti J.M., McDevitt D., Hook M., Jones D.B., Wilhelmus K.R. The collagen-binding adhesin is a virulence factor in Staphylococcus aureus keratitis. Infec. Immun. 2000;68:3776–3779. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.6.3776-3779.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerca N., Brooks J.L., Jefferson K.K. Regulation of the intercellular adhesin locus regulator (icaR) by SarA, sigmaB, and IcaR in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:6530–6533. doi: 10.1128/JB.00482-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jefferson K.K., Pier D.B., Goldmann D.A., Pier G.B. The teicoplanin-associated locus regulator (TcaR) and the intercellular adhesin locus regulator (IcaR) are transcriptional inhibitors of the locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:2449–2456. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.8.2449-2456.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clarke S.R., Harris L.G., Richards R.G., Foster S.J. Analysis of Ebh, a 1.1-megadalton cell wall-associated fibronectin-binding protein of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immu. 2002;70:6680–6687. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6680-6687.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng A.G., Missiakas D., Schneewind O. The giant protein Ebh is a determinant of Staphylococcus aureus cell size and complement resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2014;196:971–981. doi: 10.1128/JB.01366-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuroda M., Tanaka Y., Aoki R., Shu D., Tsumoto K., Ohta T. Staphylococcus aureus giant protein Ebh is involved in tolerance to transient hyperosmotic pressure. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;374:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foster T.J., Geoghegan J.A., Ganesh V.K., Höök M. Adhesion, invasion and evasion: The many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Microb. 2014;12:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corrigan R.M., Miajlovic H., Foster T.J. Surface proteins that promote adherence of Staphylococcus aureus to human desquamated nasal epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Askarian F., Ajayi C., Hanssen A.M., Van Sorge N.M., Pettersen I., Diep D.B., Johannessen M. The interaction between Staphylococcus aureus SdrD and desmoglein 1 is important for adhesion to host cells. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22134. doi: 10.1038/srep22134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng A.G., Kim H.K., Burts M.L., Krausz T., Schneewind O., Missiakas D.M. Genetic requirements for Staphylococcus aureus abscess formation and persistence in host tissues. FASEB J. 2009;23:3393–3404. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-135467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabat A., Melles D.C., Martirosian G., Grundmann H., van Belkum A., Hryniewicz W. Distribution of the serine-aspartate repeat protein-encoding sdr genes among nasal-carriage and invasive Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbio. 2006;44:1135–1138. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.1135-1138.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baba T., Bae T., Schneewind O., Takeuchi F., Hiramatsu K. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain newman and comparative analysis of Staphylococcal genomes: Polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:300–310. doi: 10.1128/JB.01000-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zdzalik M., Karim A.Y., Wolski K., Buda P., Wojcik K., Brueggemann S., Jonsson I.M. Prevalence of genes encoding extracellular proteases in Staphylococcus aureus—Important targets triggering immune response in vivo. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012;66:220–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reed S.B., Wesson C.A., Liou L.E., Trumble W.R., Schlievert P.M., Bohach G.A., Bayles K.W. Molecular characterization of a novel Staphylococcus aureus serine protease operon. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:1521–1527. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1521-1527.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paharik A.E., Salgado-Pabon W., Meyerholz D.K., White M.J., Schlievert P.M., Horswill A.R. The Spl Serine proteases modulate Staphylococcus aureus protein production and virulence in a rabbit model of pneumonia. mSphere. 2016;1:e00208–e00216. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00208-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson W.L., Sohn M.B., Taffner S., Chatterjee P., Dunman P.M., Pecora N., Wozniak R.A.F. Genomics of Staphylococcus aureus ocular isolates. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0250975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ng J.W.S., Holt D.C., Lilliebridge R.A., Stephens A.J., Huygens F., Tong S.Y.C., Currie B.J., Giffard P.M. Phylogenetically Distinct Staphylococcus aureus Lineage Prevalent among Indigenous Communities in Northern Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:2295–2300. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00122-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bretl D.J., Elfessi A., Watkins H., Schwan W.R. Regulation of the staphylococcal superantigen-like protein 1 gene of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in murine abscesses. Toxins. 2019;11:391. doi: 10.3390/toxins11070391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grumann D., Nübel U., Bröker B.M. Staphylococcus aureus toxins–Their functions and genetics. Infec. Gen. Evol. 2014;21:583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuroda M., Ohta T., Uchiyama I., Baba T., Yuzawa H., Kobayashi I., Hiramatsu K. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2001;357:1225–1240. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Becker K., Friedrich A.W., Peters G., von Eiff C. Systematic survey on the prevalence of genes coding for staphylococcal enterotoxins SElM, SElO, and SElN. Mol. Nut. Food Res. 2004;48:488–495. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200400044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisher E.L., Otto M., Cheung G.Y.C. Basis of virulence in enterotoxin-mediated staphylococcal food poisoning. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:436. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jarraud S., Peyrat M.A., Lim A., Tristan A., Bes M., Mougel C., Lina G. A highly prevalent operon of enterotoxin gene forms a putative nursery of superantigens in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 2001;166:669–677. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peterson J.C., Durkee H., Miller D., Maestre-Mesa J., Arboleda A., Aguilar M.C., Alfonso E. Molecular epidemiology and resistance profiles among healthcare and community-associated Staphylococcus aureus keratitis isolates. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019;12:831–843. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S190245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kłos M., Pomorska-Wesołowska M., Romaniszyn D., Chmielarczyk A., Wójkowska-Mach J. Epidemiology, drug resistance, and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from ocular infections in polish patients. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2019;68:541–548. doi: 10.33073/pjm-2019-056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujishima H., Okada N., Dogru M., Baba F., Tomita M., Abe J., Saito H. The role of Staphylococcal enterotoxin in atopic keratoconjunctivitis and corneal ulceration. Allergy. 2012;67:799–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu M., Parel J.M., Miller D. Interactions between staphylococcal enterotoxins A and D and superantigen-like proteins 1 and 5 for predicting methicillin and multidrug resistance profiles among Staphylococcus aureus ocular isolates. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0254519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vandenesch F., Naimi T., Enright M.C., Lina G., Nimmo G.R., Heffernan H., Etienne J. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes: Worldwide emergence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003;9:978–984. doi: 10.3201/eid0908.030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kang Y.C., Hsiao C.H., Yeh L.K., Ma D.H.K., Chen P.Y.F., Lin H.C., Huang Y.C. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ocular infection in Taiwan: Clinical features, genotying, and antibiotic susceptibility. Medicine. 2015;94:e1620. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roy P.H., Tetu S., Larouche A., Elbourne L., Tremblay S., Ren Q., Dodson R., Harkins D., Shay R., Watkins K., et al. Complete genome sequence of the multiresistant taxonomic outlier Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA7. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Subedi D., Vijay A.K., Kohli G.S., Rice S.A., Willcox M. Comparative genomics of clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from different geographic sites. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15668. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34020-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolfgang M.C., Kulasekara B.R., Liang X., Boyd D., Wu K., Yang Q., Lory S. Conservation of genome content and virulence determinants among clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8484–8489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832438100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nithya V., Rathinam S., Siva Ganesa Karthikeyan R., Lalitha P. A ten-year study of prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility pattern, and genotypic characterization of Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus causing ocular infections in a tertiary eye care hospital in South India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019;69:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wurster J.I., Bispo P.J.M., Van Tyne D., Cadorette J.J., Boody R., Gilmore M.S. Staphylococcus aureus from ocular and otolaryngology infections are frequently resistant to clinically important antibiotics and are associated with lineages of community and hospital origins. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0208518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carrel M., Perencevich E.N., David M.Z. USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, United States, 2000-2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:1973–1980. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Challagundla L., Reyes J., Rafiqullah I., Sordelli D.O., Echaniz-Aviles G., Velazquez-Meza M.E., Robinson D.A. Phylogenomic classification and the evolution of clonal complex 5 methicillin-esistant Staphylococcus aureus in the Western Hemisphere. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strauß L., Stegger M., Akpaka P.E., Alabi A., Breurec S., Coombs G., Mellmann A. Origin, evolution, and global transmission of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus ST8. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:e10596–e10604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702472114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tenover F.C., Goering R.V. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300: Origin and epidemiology. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009;64:441–446. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nurk S., Bankevich A., Antipov D., Gurevich A., Korobeynikov A., Lapidus A., Sirotkin Y. Annual International Conference on Research in Computational Molecular Biology. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2013. Assembling genomes and mini-metagenomes from highly chimeric reads; pp. 158–170. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jolley K.A., Maiden M.C.J. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Page A.J., Cummins C.A., Hunt M., Wong V.K., Reuter S., Holden M.T., Parkhill J. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Treangen T.J., Ondov B.D., Koren S., Phillippy A.M. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2014;15:524. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., Larsen M.V. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Joensen K.G., Scheutz F., Lund O., Hasman H., Kaas R.S., Nielsen E.M., Aarestrup F.M. Real-time whole-genome sequencing for routine typing, surveillance, and outbreak detection of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Clinic. Microbiol. 2014;52:1501–1510. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03617-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and available upon request.