Abstract

We purified from the culture supernatant of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 and characterized a transglycosylating enzyme which synthesized β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2, 2-acetamido-6-O-(2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-d-glucopyranosyl)-2-deoxyglucopyranose from β-(1→4)-(GlcNAc)2. The gene encoding a novel transglycosylating enzyme was cloned into Escherichia coli, and its nucleotide sequence was determined. The molecular mass of the deduced amino acid sequence of the mature protein was determined to be 99,560 Da which corresponds very closely with the molecular mass of the cloned enzyme determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The molecular mass of the cloned enzyme was much larger than that of enzyme (70 kDa) purified from the supernatant of this strain. These results suggest that the native enzyme was the result of partial proteolysis occurring in the N-terminal region. The enzyme showed significant sequence homology with several bacterial β-N-acetylhexosaminidases which belong to family 20 glycosyl hydrolases. However, this novel enzyme differs from all reported β-N-acetylhexosaminidases in its substrate specificity. To clarify the role of the enzyme in the chitinolytic system of the strain, the effect of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 on the induction of chitinase was investigated. β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 induced a level of production of chitinase similar to that induced by the medium containing chitin. On the other hand, GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, and (GlcNAc)3 conversely repressed the production of chitinase to below the basal level of chitinase activity produced constitutively in medium without a carbon source.

Chitin, an insoluble linear β-1,4-linked polymer of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), is the second most abundant polymer in nature. Many species of bacteria are known to synthesize chitin-degrading enzymes not only for utilization of chitin as a carbon and nitrogen source but also for returning chitin to the ecosystem in a biologically usable form. Chitinase (EC 3.2.1.14) and β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (GlcNAcase; EC 3.2.1.30) are essential components catalyzing the conversion of insoluble chitin to its monomeric component. Chitinases hydrolyze the insoluble chitin to soluble chitin oligomers, and GlcNAcases release GlcNAc residues from the nonreducing end of oligomers and N-acetylchitobiose [(GlcNAc)2]. These enzymes are found in a wide variety of organisms including bacteria, fungi, insects, plants, and animals, and their corresponding genes have been cloned and characterized. Among gram-negative bacteria, chitinolytic activity has been described for strains of Alteromonas (29, 34), Serratia (3, 11, 12), Aeromonas (5, 9, 21), Ewingella (10), and Vibrio (1, 13, 24). Genes encoding these chitinolytic enzymes can be generally induced by chitin and can be either induced or repressed by GlcNAc or (GlcNAc)2 which is a degradation product of chitin. However, the detailed biochemical mechanisms involved in enzyme induction are not yet fully understood.

We have been studying the chitinolytic system of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 to clarify the roles of individual enzymes involved in chitin degradation, the relationship between structure and function, and the regulation of gene expression. The chitinolytic marine bacterium Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 produces at least three different chitinases (ChiA, ChiB, and ChiC) and three different GlcNAcases (GlcNAcaseA, GlcNAcaseB, and GlcNAcaseC) in the presence of chitin. Previously, we have purified and characterized chitinases and GlcNAcases from this strain (29–32). Among them, the genes encoding ChiA (34), ChiC (29), GlcNAcaseB (33), and GlcNAcaseC (32) have been cloned and characterized to clarify the role of individual enzymes in the chitinolytic system of the microorganism. In this strain, total chitinase activities were induced by chitin and repressed by GlcNAc or (GlcNAc)2. Chitin must be hydrolyzed to smaller molecules to transport across the cell membrane. Therefore, we developed an interest in studying how this insoluble polymer would induce chitinase production in this strain. Recently, Shimoda et al. reported the highly efficient formation of a unique β-(1→6)-linked disaccharide of GlcNAc [(β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2)] from either chitin or chitin oligomers with the culture supernatant from Alteromonas sp. strain OK2607 (20); however, a transglycosylative enzyme which produces β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 has not been isolated and characterized. Here we describe the cloning of a gene encoding a novel transglycosylative enzyme. This novel enzyme differs from all reported GlcNAcases in its substrate specificity. Furthermore, we demonstrate that β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 is an active inducer of chitinase production for this strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was grown at 27°C in Bacto Marine Broth 2216 (Difco) and was used as the source of chromosomal DNA. Escherichia coli JM109 and BL21 were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (LB; 1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl). For agar medium, LB was solidified with 1.5% (wt/vol) agar (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). For the production of a transglycosylative enzyme, Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was grown at 27°C in a medium containing, per liter of artificial seawater (Jamarin S; Jamarin Laboratory, Osaka, Japan), 5.0 g of Bacto Peptone (Difco), 1.0 g of Bacto Yeast Extract (Difco), and 1.0 g of powdered chitin from crab shell (Nacalai Tesque). For chitinase induction, Altermonas sp. strain O-7 was grown at 27°C in artificial seawater containing 1% yeast extract and 50 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.5 (marine minimal medium, MMM), supplemented with various carbon sources.

Purification of a transglycosylative enzyme.

Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was grown at 27°C with agitation at 200 rpm on a rotary shaker for 18 h. The seed culture (100 ml) was transferred into a 5-liter jar fermentor containing 2 liters of the medium. Fermentation was carried out at 27°C under aeration of 0.5 liters/min and agitation at 200 rpm for 48 h. The culture supernatant (1.8 liters) was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C and was used as a crude enzyme solution. All purification steps were carried out at 4°C unless otherwise mentioned. The enzyme was precipitated by adding solid ammonium sulfate to 40% saturation in an ice bath. After centrifugation, the pellet was dissolved in a small volume of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and was dialyzed overnight against the same buffer. The dialyzed enzyme solution was applied to a DEAE-Toyopearl 650M column (1.9 by 45 cm; Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) equilibrated with the same buffer. The column was washed first with buffer and then with a linear gradient of NaCl (0 to 1.0 M) at a flow rate of 36 ml/h. The enzyme was eluted at about 0.3 M NaCl. The pooled active fractions were dialyzed against the buffer and concentrated by ultrafiltration with NanoSpin Plus (Gelman Sciences, Ann Arbor, Mich.). The concentrated sample was chromatographed by using a fast-performance liquid chromatography Q2 anion-exchange column (7 by 52 mm; Bio-Rad) equilibrated with buffer. The column was washed with buffer, and then the enzyme was eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl. Active fractions were eluted at a concentration of about 0.25 M and used as the purified enzyme solution.

Enzyme activity assay.

Transglycosylative enzyme activity was assayed by mixing a 0.1-ml aliquot of approximately diluted enzyme with 1% (GlcNAc)2 in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5. After incubation at 50°C for 30 min, the reaction was terminated by boiling the mixture for 5 min. The reaction mixture was filtrated with a 0.2-μm-pore-size membrane filter. The filtrate was analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography with a Shimadzu SPD-6A UV detector (detection, 215 nm; column, Asahipak NH2P-50 (4.6 φ by 250 mm); mobile phase, actonitrile-water (75:25, vol/vol); flow rate, 1.0 ml/min; temperature, ambient). One unit of a transglycosylative enzyme was defined as the amount of enzyme that produced 1 μmol of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 in 1 min under the conditions described above.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was done as described before (34). After electrophoresis, activity staining of chitinases in polyacrylamide gels was carried out by the method of Wolfgang et al. (39). Western blot analysis was performed with enhanced chemiluminescence-Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Life Science Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

N-terminal amino acid sequence and protein assay.

Purified protein was analyzed by an Applied Biosystems model 473A gas-phase sequencer. Protein was assayed by the method of Bradford (2), with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Isolation of the gene encoding a transglycosylative enzyme.

Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 total DNA, prepared as described previously (34), was used as a template for PCR. The bidirectional degenerated PCR primers were synthesized based on the N-terminal amino acid sequence of purified enzyme. The sequences of the primers were 5′-CA(A,G)GA(C,T)-AA(C,T)CA(A,G)CC(A,C,G,T)GA(C,T)GC-3′ and 5′-CC(A,C,G,T)GT(A,C,T)AT-(A,C,G,T)GT(A,C,T)AT(A,C,G,T)CC-3′. PCR amplification was performed for 50 cycles consisting of 94°C for 30 s, 40°C for 2 s, and 74°C for 30 s. The 75-bp product obtained was subcloned into pMOS Blue (Amersham Life Science), sequenced, and used as a probe.

Chromosomal DNA was digested with EcoRI and electrophoresed on 0.6% agarose gel. The fragments in the range of 3.6 to 4.2 kb were excised from the gel, purified with a Sephaglas BandPrep kit (Pharmacia), and then ligated into the dephosphorylated EcoRI site of pUC18; the recombinant plasmids were inserted into competent E. coli JM109. The library was screened by colony hybridization with the alkaline phosphatase-labeled amplified fragment as a probe (AlkPhos DIRECT; Amersham Life Science). Hybridization and washing were performed according to the supplier’s instructions.

Nucleotide sequencing.

A series of subclones from a 3.6-kb EcoRI fragment obtained by colony hybridization were prepared by using pUC18 or pUC19. The nucleotide sequence was determined by the dideoxy-chain termination method (19) with a Thermo Sequenase fluorescence-labeled primer cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Life Science). DNA fragments were analyzed on a Hitachi model SQ3000 DNA sequencer. Sequence data were analyzed with GENETYX computer software. Homology searches in GenBank were carried out with a BLAST program.

Induction study of chitinases.

Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was precultured in ZoBell 2216E medium at 27°C for 16 h. After centrifugation, the cells were washed twice with artificial seawater and suspended with a small volume of artificial seawater. The cells were used to inoculate a 100-ml flask with three indents containing 20 ml of MMM supplemented with various carbon sources. Cultures were grown at 27°C under agitation at 200 rpm on a rotary shaker for 24 h, and chitinase activities in the culture supernatant were periodically measured.

Chemicals.

β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 was prepared by enzymatic conversion of (GlcNAc)2 by the method of Shimoda et al. (20). β-(1→4)-(GlcNAc-GlcN) and β-(1→4)-(GlcN-GlcNAc) were kindly provided by K. Ohishi (Numazu Industrial Research Institute of Shizuoka Prefecture) and K. Tokuyasu (National Food Research Institute), respectively. (GlcNAc)2 was kindly provided by the Yaizu Suisan Chemical Co. (Shizuoka, Japan). All other chemicals were of reagent grade and obtained commercially.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper will appear in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence databases with accession no. AB026053.

RESULTS

Purification of a transglycosylative enzyme.

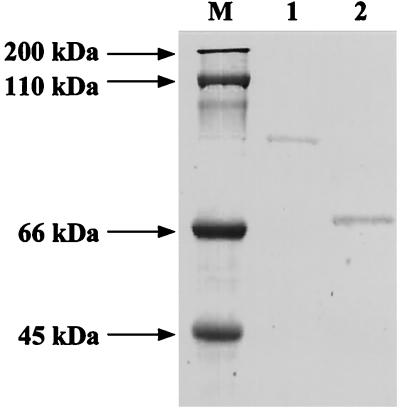

To characterize a transglycosylative enzyme, the enzyme was purified from the supernatant of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 by ammonium sulfate precipitation and DEAE-Toyopearl 650M column and Q2 anion-exchange column chromatographies. By the procedure described, the enzyme was purified about 4.2-fold with a yield of 3.5%, as shown in Table 1. The yield of the enzyme was a very low because much of the activity left in the fractions was discarded to improve the efficiency of the purification. The purified enzyme showed a single band on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). The molecular masses of the enzyme were 70 and 68 kDa, as determined by SDS-PAGE and analytical size exclusion fast-performance liquid chromatography (Superdex 200; Pharmacia), respectively. These results indicate that the enzyme is a monomeric protein. The N-terminal sequence of the enzyme was QDNQPDASGYKLEVDAFSGITITG.

TABLE 1.

Purification of the transglycosylative enzyme

| Fraction | Total proteina (mg) | Total activity (U) | Sp actb (U/mg of protein) | Purification factor | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture supernatant | 596 | 6.0 × 105 | 1,007 | 1.0 | 100.0 |

| 0–40% (NH4)2SO4 | 46 | 6.4 × 104 | 1,391 | 1.4 | 10.7 |

| DEAE-Toyopearl 650M | 39 | 6.2 × 104 | 1,589 | 1.6 | 10.3 |

| Bio-scale Q2 | 5 | 2.1 × 104 | 4,200 | 4.2 | 3.5 |

Protein concentration was measured by the method of Bradford (2), with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that produced 1 μmol of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 per min.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of a transglycosylative enzyme from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 and the cloned enzyme from E. coli. Lanes: 1, the cloned enzyme; 2, a transglycosylative enzyme from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7; M, marker proteins.

Substrate specificity.

We investigated the substrate specificity of the enzyme by using various substrates, such as GlcNAc, chitin oligosaccharides from (GlcNAc)2 to (GlcNAc)6, GlcNAc-GlcN (GlcN, glucosamine), GlcN-GlcNAc, p-nitrophenyl-β-N-acetylglucosamine (PNP-GlcNAc) and PNP-GlcN. The enzyme showed transglycosylative activity on (GlcNAc)2 but showed no activity on the other substrates tested. The pH activity profile obtained with (GlcNAc)2 showed a maximum at pH 7.0, and the temperature optimum was 50°C.

Cloning of the transglycosylative enzyme-encoding gene.

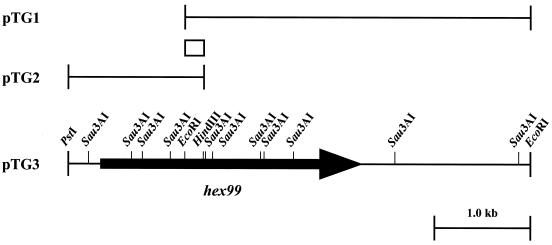

To isolate the transglycosylative enzyme-encoding gene from a genomic library of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7, a PCR probe was synthesized on the basis of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the enzyme. Southern hybridization using this probe against total DNA digested with various restriction endonucleases showed that the probe hybridized strongly with EcoRI fragments of about 3.6 kb (data not shown). Thus, for library construction, the DNA fragments with sizes between 3.6 and 4.2 kb were ligated to pUC18 digested with EcoRI and introduced into E. coli JM109. Among 1,056 transformants, four positive clones which hybridized to the probe were isolated by colony hybridization. The clones (pTG1) were analyzed by restriction endonuclease digestion and found to contain a common 3.6-kb insert (Fig. 2). However, analysis of the entire nucleotide sequence of the inserted DNA indicated deletion of the 5′ upstream region. Thus, we cloned the upstream region of the open reading frame (ORF) by the DNA-probing method with a 214-bp fragment, isolated from the inserted DNA by EcoRI and HindIII digestion, as a probe. Southern hybridization showed that a 1.4-kb chromosomal fragment digested with PstI and HindIII hybridized to the probe. This fragment was recovered from agarose gel, cloned into pUC18, and transformed into E. coli JM109. Among the approximately 1,000 transformants tested, a set of five clones (pTG2) containing identical inserted DNA was obtained. Analyses by restriction endonuclease and by sequencing of the fragment showed that two inserts from pTG1 and pTG2 had in common a 214-bp EcoRI-HindIII region. Plasmid pTG3, which contained the full-length gene encoding the enzyme, was constructed by combining a 3.6-kb EcoRI fragment from pTG1 and a 1.2-kb PstI-EcoRI fragment from pTG2 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Restriction map of the gene, hex99, encoding a transglycosylative enzyme. The hybridization probe (EcoRI-HindIII fragment) is represented by the box; the arrow indicates the ORF and direction of transcription.

Nucleotide sequence and putative product of the gene.

The nucleotide sequence of each strand of pTG3 was determined, and sequence analysis revealed a single ORF. The ORF has an ATG start codon at position 91 which is preceded by a possible ribosome-binding site (GGAG) at a distance of five nucleotides. It could encode a protein of 914 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 101,532 Da. The molecular mass of the translated protein was much larger than that of the enzyme purified from the supernatant of this strain (70 kDa), determined by SDS-PAGE. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the enzyme purified from the culture supernatant did not match any region near the N terminus of the deduced polypeptide; however, it coincided precisely with the sequence starting from glutamine 285 of the deduced polypeptide. These results suggest that two forms of enzyme differing in size were the result of partial proteolysis occurring in the N-terminal region. The deduced N-terminal amino acid sequence showed the typical features of signal peptides, which are composed of a positively charged region, a hydrophobic region, and a signal sequence cleavage site. Characterization of the putative cleavage site suggests that it may lie between serine 13 and leucine 14, which is compatible with the -3,-1 rule of von Heijne (37).

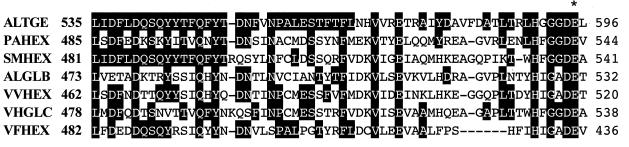

Comparison of the deduced product of the ORF with the BLAST database revealed that the gene encoded a protein homologous to the several β-hexosaminidases belonging to family 20 (7, 8). The ORF was designated hex99 on the basis of the molecular mass of the mature protein. The gene product Hex99 is aligned with some representative enzymes in Fig. 3. Hex99 showed homology with β-hexosaminidase (32% identity) from Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain S9 (25), chitobiase (31% identity) from Serratia marcescens (27), β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (31% identity) from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 (33), β-hexosaminidase (29% identity) from Vibrio vulnificus (22), chitobiase (29% identity) from V. harveyi (23), and β-N-acetylhexosaminidase (29% identity) from V. furnissi (14). Based on the crystal structure of S. marcescens chitobiase (28), it was proposed that chitobiase uses an acid-base reaction mechanism with glutamic acid 540 as the catalytic amino acid, which is well conserved in all family 20 glycosyl hydrolases. Despite this similarity, there is significant difference in substrate specificity. The chitobiases, β-hexosaminidase, and β-N-acetylglucosaminidase so far reported hydrolyzed PNP-GlcNAc and/or PNP-GlcN. However, Hex99 showed no activity toward these chromogenic substrates.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the amino acid sequence of Hex99 with those of the active-site regions of β-N-acetylhexosaminidases. The residue number of the first amino acid in each line is shown on the left. Residues that are identical are indicated by white letters on a black background. The putative active-site glutamic acid residue is marked by an asterisk. ALTGE, Hex99 from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7; PAHEX, β-hexosaminidase from Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain S9; SMHEX, β-N-acetylhexosaminidase from S. marcescens; ALGLB, β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7, VVHEX, β-N-acetylhexosaminidase from V. vulnificus; VHGLC, β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from V. harveyi; VFHEX, β-N-acetylhexosaminidase from V. furnissii.

Purification of the cloned enzyme.

To purify and characterize the cloned enzyme, E. coli carrying pTG3 was cultured to the early stationary phase at 37°C with vigorous shaking. The cells (10.8 g) were collected by centrifugation, and the periplasmic fraction containing a transglycosylating enzyme (400 ml) was prepared as described previously (34). The cloned enzyme was purified from the periplasmic fraction by the same procedure as the native enzyme from the supernatant of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. The enzyme showed a single band on SDS-PAGE, and the molecular mass was estimated to be 99 kDa, as shown in Fig. 1. The N-terminal sequence of the cloned enzyme (GLALL) was good agreement with the sequence starting from glycine 14 of the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by the hex99 gene. Thus, we determined that cleavage of the signal peptide occurred between serine 13 and glycine 14. The cloned enzyme showed almost the same enzymatic properties (specific activity, substrate specificity, and optimum pH and temperature) as the native enzyme, indicating that the N-terminal portion of Hex99 is not essential for enzyme activity. This N-terminal portion of Hex99 showed no significant similarity to any other protein in GenBank databases.

Effect of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 on chitinase induction.

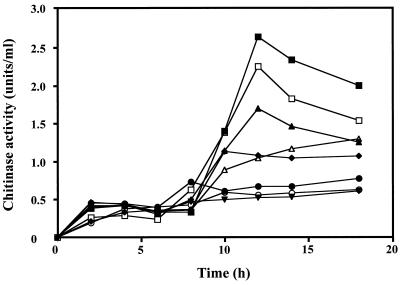

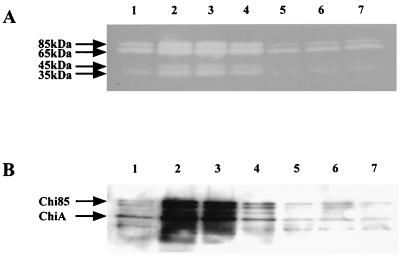

To clarify the role of Hex99 in the chitinolytic system of the strain, the effect of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 on induction of chitinases was investigated. When Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was cultured in MMM without a carbon source, the strain produced a low level of chitinase activity (Fig. 4). When the strain was grown in medium containing powdered chitin or β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2, chitinase activity gradually increased and reached the maximum after 12 h. Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 showed almost identical growth curves in MMM with and without a carbon source (data not shown). The induction effect increased as the concentration of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 rose. Chitinase activity was induced 2.4-fold by 0.1% chitin and 2.0-fold by 1.0% β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 compared to the basal level of chitinase produced when the strain was cultured for 12 h in MMM without a carbon source. On the other hand, GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, and (GlcNAc)3 repressed chitinase production to below the basal level. Since these results were based on total chitinase activities of more than one enzyme, activity staining of chitinases in SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing glycol chitin was performed to examine the level of induction of individual enzymes (Fig. 5). Four chitinase activity bands corresponding to proteins of 85 kDa (Chi85), 65 kDa (ChiA, a truncated form of Chi85), 45 kDa (ChiC), and 35 kDa (ChiB) were observed in all culture supernatants tested. The synthesis of each chitinase increased in the presence of chitin or β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2, whereas GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, and (GlcNAc)3 repressed the production of chitinases. We also tested the effect of addition of GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, (GlcNAc)3, or glucose to the chitin-containing medium. Repression was observed when GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, or (GlcNAc)3 was added as a carbon source, whereas glucose had no effect (data not shown). These results conformed well to those shown in Fig. 4. We previously suggested that the 65-kDa chitinase (ChiA) is a truncated form of the initial gene product (Chi85), based on comparison between the N-terminal amino acid sequence of ChiA and the deduced amino acid sequence of the cloned gene and their enzymatic properties. Western blot analysis using a polyclonal rabbit antibody to ChiA revealed that ChiA is a proteolytically processed form of Chi85 (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Time course of chitinase production by Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 cultured in media containing various carbon sources. Aliquots were taken at the indicated times and centrifuged; chitinase activity was measured with PNP-(GlcNAc)2 as a substrate. Symbols: ■, 0.1% chitin; □, 1% β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2; ▴, 0.1% β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2; ▵, 0.1% glucose; ▾, 0.1% (GlcNAc)2; ●, 0.1% GlcNAc; ○, 0.1% (GlcNAc)3; ⧫, no addition. Data represent the means of three independent experiments.

FIG. 5.

Effects of various carbon sources on induction of extracellular chitinase activity. (A) Zymogram of chitinase activity; (B) Western blot analysis. Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was cultured in media containing various carbon sources; samples were taken at 12 h. Lanes: 1, no addition; 2, 0.1% chitin; 3, 1% β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2; 4, 0.1% β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2; 5, 0.1% (GlcNAc)2; 6, 0.1% GlcNAc; 7, 0.1% (GlcNAc)3.

DISCUSSION

Chitinolytic bacteria convert chitin to GlcNAc by the cooperative interaction of two enzymes, chitinase and GlcNAcase, and the process is a key transformation step in the biological carbon and nitrogen cycles in nature. A number of chitinolytic enzymes have been well characterized biochemically, and their genes have been identified. We recently found in the culture supernatant of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 grown in the presence of chitin a novel transglycosylative enzyme which is clearly different in substrate specificity from the chitinolytic enzymes so far reported. In the present study, we identified and sequenced a gene (hex99) encoding a transglycosylative enzyme from the strain and expressed the gene in E. coli. The cloned enzyme was purified from the periplasmic fraction of E. coli transformants. In most cases, when genes encoding foreign extracellular proteins are cloned in E. coli, the precursor is synthesized, processed, and exported across the inner membrane. The cloned enzyme was not secreted into the growth medium but accumulated in the periplasmic space, indicating that the signal peptide is functional in E. coli; however, Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 makes use of a secretion machinery different from that of E. coli to cross the outer membrane. The sequence of the first five amino acids at the N terminus of the pure protein was determined and found to match exactly an amino acid sequence deduced from the gene sequence of hex99. The deduced amino acid sequence of the mature protein, based on the position of the N-terminal amino acid sequence, includes 901 amino acids that would theoretically encode a protein with an Mr of 99,560. This corroborates the result of SDS-PAGE and demonstrates that the protein purified and characterized in this work was encoded by the hex99 gene from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. On the other hand, the native enzyme of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was recovered as a single 70-kDa polypeptide from the growth medium, and the N-terminal amino acid sequence matched the sequence starting from Gln285 of the deduced polypeptide, indicating that the enzyme is truncated form of the initial gene product. Two proteolytic enzymes (AprI and AprII) were detected in the culture supernatant of the strain (35, 36). Therefore, AprI and/or AprII seem to be involved in the specific cleavage of Hex99, although this remains to be examined experimentally. Study of the function of the N-terminal region is under way.

Amino acid sequence analysis showed that Hex99 has homology to bacterial β-N-acetylglucosaminidase, β-N-acetylhexosaminidase, and chitobiase belonging to family 20 glycosyl hydrolases (7, 8); on the basis of these alignments we believe that Hex99 should be classified in family 20. Family 20 enzymes generally hydrolyze PNP-β-GlcNAc and/or PNP-β-GalNAc; however, unlike these enzymes, Hex99 was inactive with these chromogenic substrates and all other substrates tested except (GlcNAc)2. Although there is extensive literature on hexosaminidases from a wide variety of organisms, to our knowledge there are no reports on enzymes with unique specificity like that of Hex99.

To clarify the role of Hex99 in the chitinolytic system of the strain, the effect of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 on induction of chitinases was investigated. In chitinase-producing microorganisms, chitin is a common inducer of chitinase production. However, since chitin is insoluble and impermeable to microorganisms, a soluble degradation product(s) such as GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, or higher oligomers is considered to act as a direct inducer of chitinase. For example, it has been reported that chitinases from V. furnissi (1), V. harveyi (17), and Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain S9 (26) are induced by GlcNAc, and chitinases from S. marcescens (38) are induced by (GlcNAc)2. On the other hand, it has been shown that GlcNAc represses chitinase production in S. marcescens (15) and S. lividans (18). In Alteromonas sp. strain O-7, chitin induced four chitinases differing in size. On the other hand, GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, and (GlcNAc)3, which are soluble degradation products of chitin, repressed the production of chitinases to below the basal level of chitinase activity produced constitutively in MMM without a carbon source. This was probably because the membrane-associated GlcNAcase of this strain (31), designated GlcNAcaseA, readily split (GlcNAc)2 or higher oligosaccharides into GlcNAc. These results suggest that a soluble substrate analog(s) of low molecular weight other than GlcNAc and (GlcNAc)2 acts as an effective inducer in Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. Thus, an investigation of the active inducer for chitinase production was undertaken. Chitinolytic activity was induced when the strain was grown in medium containing β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2. β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 induced a level of production of chitinase similar to that induced by medium containing chitin. Repression was observed when GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, or (GlcNAc)3 was added to medium containing chitin, whereas the addition of glucose had no effect. Chitin degradation by microorganisms is extraordinarily complex, involving multiple signal transduction systems and many proteins (1). Montgomery and Kirchman have demonstrated that production of chitin-binding proteins, chitinase activity, and attachment to chitin are induced in V. harveyi by chitin and GlcNAc oligomers (17). Thus, it remains to be investigated if proteins other than chitinase involved in the chitin degradation system of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 are inducible by the addition of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2.

From the pioneering work of Monod (16), it is known that some substrate analogs which cannot be enzymatically cleaved are effective inducers for glycosidases. In induction of β-galactosidase in E. coli (4), an active inducer is not lactose but allolactose (6-O-β-d-galactopyranosyl-d-glucose), which is a transglycosylation product from lactose by β-galactosidase itself. We determined that β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 formed by extracellular Hex99 was the smallest molecule to induce chitinase production in Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. The involvement of other elements in chitinase induction could not be excluded, because recent report by Chernin et al. demonstrated that quorum-sensing control mediated by N-hexanoyl-l-homoserine lactone plays an important role in the regulation of chitinase production in a gram-negative bacterium (6).

In conclusion, we propose that induction of chitinase by chitin occurs in Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 by the following process. Chitin is converted by low constitutive levels of chitinases to (GlcNAc)2, some of which is cleaved by membrane-associated GlcNAcaseA. The extracellular (GlcNAc)2 is subsequently transglycosylated to β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2, an active inducer, by extracellular Hex99, and β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 enhances the expression of chitinase genes. Since β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 induces chitinase production, it presumably interacts with the transcriptional regulatory protein that control the expression of chitinase genes. Studies of the transport system and metabolic route of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 are under way to obtain more information about the mechanism of induction of chitinase genes in Alteromonas sp. strain O-7.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Kazuyoshi Masaki (Toyo Suisan Kaisha, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for helpful advice and timely guidance. We are also grateful to Toyo Suisan Kaisha for providing the authentic sample of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassler B L, Yu C, Lee Y C, Roseman S. Chitin utilization by marine bacteria. Degradation and catabolism of chitin oligosaccharides by Vibrio furnissii. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24276–24286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brurberg M B, Eijsink V G H, Haandrikman A J, Venema G, Nes I F. Chitinase B from Serratia marcescens BJL200 is exported to the periplasm without processing. Microbiology. 1995;141:123–131. doi: 10.1099/00221287-141-1-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burstein C, Cohn M, Kepes A, Monod J. Role of lactose and its metabolic products in the induction of the lactose operon in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1965;95:634–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J P, Nagayama F, Chang M C. Cloning and expression of a chitinase gene from Aeromonas hydrophila in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2426–2428. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.8.2426-2428.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chernin L S, Wilson M K, Thompson J M, Haran S, Bycroft B W, Chet I, Williams P, Stewart G S A B. Chitinolytic activity in Chromobacterium violaceum: substrate analysis and regulation by quorum sensing. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4435–4441. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4435-4441.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henrissat B. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1991;280:309–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. New families in the classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1993;293:781–788. doi: 10.1042/bj2930781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inbar J, Chet I. Evidence that chitinase produced by Aeromonas caviae is involved in the biological control of soil-borne plant pathogens by this bacterium. Soil Biol Biochem. 1991;23:973–978. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inglis P W, Peberdy J F. Production and purification of a chitinase from Ewingella americana, a recently described pathogen of the mushroom, Agaricus bisporus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones J D G, Grady K L, Suslow T V, Bedbrook J R. Isolation and characterization of the genes encoding two chitinase enzymes from Serratia marcescens. EMBO J. 1986;5:467–473. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshi S, Kozlowski M, Selvaraj G, Iyer V N, Davies R W. Cloning of the genes of the chitin utilization regulon of Serratia liquefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2984–2988. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.2984-2988.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keyhani N O, Wang L-X, Lee Y C, Roseman The chitin catabolic cascade in the marine bacterium Vibrio furnissii. Characterization of an N,N′-diacetyl-chitobiose transport system. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33409–33413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keyhani N O, Roseman S. The chitin catabolic cascade in the marine bacterium Vibrio furnissii. Molecular cloning, isolation, and characterization of a periplasmic β-N-acetylglucosaminidase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33425–33432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monreal J, Reese E T. The chitinase of Serratia marcescens. Can J Microbiol. 1969;15:689–696. doi: 10.1139/m69-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monod J. Remarks on the mechanism of enzyme induction. In: Woff A, Ullmann A, editors. Selected papers on molecular biology by Jaque Monod. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1956. pp. 313–334. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery M T, Kirchman D L. Role of chitin-binding proteins in the specific attachment of the marine bacterium Vibrio harveyi to chitin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:373–379. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.2.373-379.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neugebauer E, Gamache B, Dery V, Brzezinski R. Chitinolytic properties of Streptomyces lividans. Arch Microbiol. 1991;156:192–197. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimoda K, Nakajima K, Hiratsuka Y, Nishimura S, Kurita K. Efficient preparation of β-(1→6)-(GlcNAc)2 by enzymatic conversion of chitin and chito-oligosaccharides. Carbohydr Polym. 1996;29:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiro M, Ueda M, Kawaguchi T, Arai M. Cloning of a cluster of chitinase genes from Aeromonas sp. no. 10S-24. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1305:44–48. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Somerville C C, Colwell R R. Sequence analysis of the β-N-acetylhexosaminidase gene of Vibrio vulnificus: evidence for a common evolutionary origin of hexosaminidases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6751–6755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soto-Gil R W, Zyskind J W. N,N′-Diacetylchitobiase of Vibrio harveyi: primary structure, processing, and evolutionary relationships. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14778–14783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Svitil A L, Ni Chadhain S M, Moore J A, Kirchman D L. Chitin degradation proteins produced by the marine bacterium Vibrio harveyi growing on different forms of chitin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:408–413. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.408-413.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Techkarnjanaruk, S., and A. E. Goodman. 1999. GenBank accession no. AF072375.

- 26.Techkarnjanaruk S, Pongpattanakitshote S, Goodman A E. Use of a promoterless lacZ gene insertion to investigate chitinase gene expression in the marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain S9. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2989–2996. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.2989-2996.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tews I, Vincentelli R, Vorgias C E. N-Acetylglucosaminindase (chitobiase) from Serratia marcescens: gene sequence, and protein production and purification in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1996;170:63–67. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00848-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tews I, Perrakis A, Oppenheim A, Dauter Z, Wilson K S, Vorgias C E. Bacterial chitobiase structure provides insight into catalytic mechanism and the basis of Tay-Sachs disease. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:638–648. doi: 10.1038/nsb0796-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsujibo H, Orikoshi H, Shiotani K, Hayashi M, Umeda J, Miyamoto K, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Characterization of chitinase C from a marine bacterium, Alteromonas sp. strain O-7, and its corresponding gene and domain structure. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:472–478. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.472-478.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsujibo H, Yoshida Y, Miyamoto K, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Purification, properties, and partial amino acid sequence of chitinase from a marine Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. Can J Microbiol. 1992;38:891–897. doi: 10.1139/m92-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsujibo H, Fujimoto K, Kimura Y, Miyamoto K, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Purification and characterization of β-acetylglucosaminidase from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:1135–1136. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsujibo H, Fujimoto K, Tanno H, Miyamoto K, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Gene sequence, purification and characterization of N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase from a marine bacterium, Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. Gene. 1994;146:111–115. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90843-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsujibo H, Fujimoto K, Tanno H, Miyamoto K, Kimura Y, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Molecular cloning of the gene which encodes β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from a marine bacterium, Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:804–806. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.804-806.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsujibo H, Orikoshi H, Tanno H, Fujimoto K, Miyamoto K, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Cloning, sequence, and expression of a chitinase gene from a marine bacterium, Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:176–181. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.176-181.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsujibo H, Miyamoto K, Tanaka K, Kawai M, Tainaka K, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Cloning and sequence of an alkaline serine protease-encoding gene from the marine Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. Gene. 1993;136:247–251. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90473-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsujibo H, Miyamoto K, Tanaka K, Kaidzu Y, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Cloning and sequence analysis of a protease-encoding gene from the marine bacterium Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:1284–1288. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Heijne G. Patterns of amino acids near signal sequence cleavage sites. Eur J Biochem. 1983;133:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe T, Kimura K, Sumiya T, Nikaidou N, Suzuki K, Suzuki M, Taiyoji M, Ferrer S, Regue M. Genetic analysis of the chitinase system of Serratia marcescens 2170. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7111–7117. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7111-7117.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfgang H S, Bronnenmeier K, Gräbnitz F, Staudenbauer W L. Activity staining of cellulases in polyacrylamide gels containing mixed linkage β-glucans. Anal Biochem. 1987;164:72–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]