Abstract

The major virulence factor of the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans is an extensive polysaccharide capsule which surrounds the cell. Almost 90% of the capsule is composed of a partially acetylated linear α-1,3-linked mannan substituted with d-xylose and d-glucuronic acid. A novel mannosyltransferase with specificity appropriate for a role in the synthesis of this glucuronoxylomannan is active in cryptococcal membranes. This membrane-associated activity transfers mannose in vitro from GDP-mannose to an α-1,3-dimannoside acceptor, forming a second α-1,3 linkage. Product formation by the transferase is dependent on protein, time, temperature, divalent cations, and each substrate. It is not affected by amphomycin or tunicamycin but is inhibited by GDP and mannose-1-phosphate. The described activity is not detectable in the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, consistent with the absence of a similar polysaccharide structure in that organism. A second mannosyltransferase from C. neoformans membranes adds mannose in α-1,2 linkage to the same dimannoside acceptor. The two activities differ in pH optimum and cation preference. While the α-1,2 transferase does not have specificity appropriate for a role in glucuronoxylomannan synthesis, it may participate in production of mannoprotein components of the capsule. This study suggests two new targets for antifungal drug discovery.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a pathogenic fungus responsible for life-threatening disease in immunosuppressed populations (21). Affected individuals include 5 to 10% of patients with AIDS as well as those who are functionally immunosuppressed due to lymphoproliferative disorders or secondary to treatment after organ transplantation (9, 17). Current therapy for this disease is inadequate due to harmful adverse drug reactions, the inability to completely clear infection in severely ill patients, and the development of resistant organisms (10, 21).

The major virulence factor of C. neoformans is its elaborate polysaccharide capsule, which surrounds the cell membrane and the glucan-based cell wall (18). This impressive structure may have a radius many times that of the cell itself, and its production varies with metabolic state and environment (1, 13, 20, 25, 29). The capsule has been implicated in multiple fungal mechanisms to evade or weaken host defenses (3), and cells that do not produce it are unable to cause fatal infections in animal models for cryptococcosis (4–6). The three main capsule components (reviewed in reference 7) are mannoprotein, galactoxylomannan (GalXM), and glucuronoxylomannan (GXM).

GXM accounts for 88% of the capsule mass and confers serotype specificity on the organism (7). It is shed into the host’s bloodstream by an unknown mechanism and is the basis for diagnosis of cryptococcal infection (2). The structure of GXM (Fig. 1) has been well studied and consists of an extensive (>100,000 Da) linear mannan in α-1,3 linkage with 3 to 10% of the residues 6-O acetylated. Monosaccharide side chains of β-1,2-linked glucuronic acid and β-1,2- and β-1,4-linked xylose are present in ratios which vary with the serotype examined. The overall ratios of mannose/glucuronic acid/xylose range from 3:1:1 (serotype D) to 3:1:4 (serotype C), and the patterns of side-chain addition allow nuclear magnetic resonance-based chemotyping of cryptococcal strains (8). Investigations of capsule biosynthesis have been limited, although incorporation of radiolabeled sugars from UDP-xylose and UDP-glucuronic acid into mannans in crude membrane systems has been observed (30). A mannosyltransferase of appropriate specificity for a role in GXM synthesis has not been identified, despite efforts to do so (31).

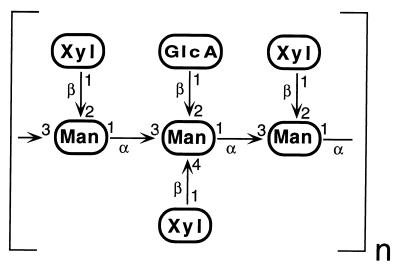

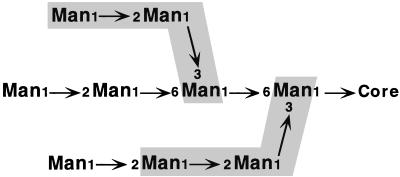

FIG. 1.

Major repeat unit of GXM from C. neoformans serotype B. The trimer repeat is composed of mannose (Man), xylose (Xyl), and glucuronic acid (GlcA) in the linkages depicted. The acetylation of mannose described in the text is not shown.

Genetic approaches to understanding capsule synthesis have been attempted. Mutants which produce abnormally high or low levels of capsular material have been isolated in screens based on gross morphology (15, 16, 19). Three genes putatively involved in capsule synthesis have been cloned by complementation of capsule mutants, but their sequences show no homology to known genes involved in sugar metabolism (4–6).

Because of the importance of C. neoformans as a pathogen, and the inadequacy of current treatment, there is a need to identify new therapeutic agents effective against this fungus. The unusual structure of GXM suggests that biosynthesis of this virulence factor represents a pathway that could be effectively targeted. Of particular interest is the mannan backbone, which is unique in its extent of repeated α-1,3 mannose residues. Although the termini of some O-linked glycans in Saccharomyces cerevisiae contain two to three residues linked in this manner (reviewed in reference 23), longer repeats of this structure have not been reported in any organism. To begin investigations of capsule synthesis, I searched for an appropriate mannosyltransferase activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Guanosine diphosphate [2-3H]mannose (15 Ci/mmol) was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc. (St. Louis, Mo.), and α-1,3-d-mannobiose was from V-Labs, Inc. (Covington, La.). Medium components were from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, Mich.), amphomycin was a gift of S. Turco (University of Kentucky), and GXM-derived mannan was a gift of R. Cherniak (Georgia State University). Where not specified, other materials were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.).

Strains and cell growth.

S. cerevisiae RSY607 (MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 PEP4::URA3) was obtained from R. Schekman (University of California at Berkeley). C. neoformans ATCC 24067 (32) and the acapsular mutant strain Cap67 (15) were obtained from A. Casadevall (Albert Einstein College of Medicine). All cultures were grown in YPD (1% Bacto Yeast Extract, 2% Bacto Peptone, 2% dextrose) at 30°C with continuous shaking (200 rpm). Growth was monitored by turbidity at 600 nm. An absorbance reading of 1.0 at this wavelength in a 1-cm-diameter cuvette corresponds to a cell density of approximately 107/ml.

Membrane preparation.

Overnight (saturated) cultures were diluted in YPD such that growth for 7 to 10 generations resulted in absorbance readings of 1 to 2 (early logarithmic growth). Cells from a 1-liter culture were chilled and collected by centrifugation (3,000 × g; 15 min; 4°C), and all subsequent steps were performed on ice.

The cells were washed once with distilled water and once with buffer A (100 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.5], 0.1 mM EDTA). The pellet was resuspended in 1 to 2 ml of buffer A, and 0.5-mm-diameter glass beads (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, Okla.) were added to the level of the meniscus. The cells were lysed by vigorous vortex mixing of the suspension for five 60-s intervals, alternating with equal intervals on ice. Lysis was assessed by microscopic examination, and the lysate was transferred to a fresh tube. The beads were rinsed in buffer A, and the rinse was pooled with the lysate. This combined material was subjected to centrifugation (1,000 × g; 5 min; 4 °C) to remove debris and unbroken cells, and the supernatant fraction was then spun at 100,000 × g (45 min; 4°C). The resulting membrane pellet was resuspended in buffer A and resedimented under the same conditions.

The final high-speed pellet consisted of three layers: a minor dark-brown portion at the bottom of the tube, a broader beige layer above that, and (in wild-type C. neoformans only) a broad creamy upper layer enriched in capsular material. This pellet is similar to that described for biosynthetically active membrane preparations from a nonpathogenic species of cryptococcus, Cryptococcus laurentii (27). Efforts were made to remove the capsular material (when it was present) and to resuspend only the middle layer in buffer A for protein analysis (Bio-Rad [Hercules, Calif.] protein assay) and activity assay (see below). Membranes were typically diluted to 60 mg/ml and stored at 4°C. Enzyme activity was stable when the membranes were stored for up to 1 month and was retained when the membranes were frozen at −70°C in the presence of glycerol and thawed before assay (data not shown).

Mannosyltransferase assay.

Standard assays (50 μl) included 0.45 mg of membrane protein, 0.25 mg of α-1,3-d-mannobiose, and 0.5 μCi of GDP-[3H]mannose in buffer A supplemented with 15 mM MgCl2 or other cations as indicated in the text. The reaction mixture was prepared on ice and incubated for 40 min at 30°C (unless otherwise indicated). The reaction was stopped by the addition of Triton X-114 (2% final concentration) and returned to ice for 15 min with occasional vortex mixing. To recover soluble products from the membrane mixture, the extract was centrifuged (15,000 × g; 5 min; 4°C) and the supernatant fraction was then incubated briefly at 32°C. The clouded detergent mixture was spun to achieve phase separation (15,000 × g; 30 s; room temperature), and the upper (aqueous) phase was applied to minicolumns containing AG 2-X8 resin (Bio-Rad Laboratories) to remove unincorporated radiolabel.

Column effluents were dried and resuspended in 10 μl of 40% n-propanol for application to thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates (Kieselgel 60; Merck). The plates were developed three times in n-propanol/acetone/water (5:4:2) with air drying between developments, and radioactive products were localized by tritium scanning (System 200A imaging scanner; Bioscan Inc., Washington, D.C.) or by autoradiography after spraying the plates with En3Hance (NEN Research Products, Boston, Mass.). Partial hydrolysis (3 h; 95°C; 0.1 N HCl) of unsubstituted mannan generated from cryptococcal GXM (generously provided by R. Cherniak) yielded a ladder of α-1,3-linked mannose oligomers which served as standards. The standards were detected after being sprayed with orcinol solution (26).

Mannosidase treatments.

For mannosidase analysis, the standard assay was scaled up fourfold and the product of interest was localized by scanning. Material was scraped from the appropriate region of the plate and extracted twice with the solvent mixture used for plate development and once with distilled water. Pooled extracts were dried and resuspended in reaction buffers provided by the manufacturers and then incubated overnight (37°C) with mannosidases from the following organisms (specificity and vendor indicated): Xanthomonas manihotis (α-1,6 and α-1,2/α-1,3) from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.); jack bean (α-1,2/α-1,3/α-1,6) from Boehringer Mannheim Corporation (Indianapolis, Ind.) or from Oxford Glycosystems (Oxford, United Kingdom); and Aspergillus saitoi (α-1,2) and Helix pomatia (β-1,4) from Oxford Glycosystems. According to the manufacturer, this preparation of the H. pomatia enzyme is known to cleave mannose that is linked β-1,4, but it has not been tested on other β linkages.

RESULTS

To begin studies of the mannosyltransferase responsible for GXM synthesis, an assay with a crude cryptococcal membrane preparation as a source of activity was devised. α-1,3-d-mannobiose (V-Labs, Inc.) was included in the assay as a soluble acceptor because the activity of interest extends a chain of α-1,3-linked mannose, and GDP-[3H]Man was included as the sugar donor. Initial experiments were performed with membranes from ATCC 24067, a serotype D isolate from the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with cryptococcal meningitis (32). However, it was difficult to efficiently break these highly encapsulated cells, resulting in poor membrane yields with low synthetic activity. For this reason, parallel experiments with an acapsular strain (Cap67 [15]) were performed. Experimental results with ATCC 24067 and Cap67 were qualitatively identical, and the greater yields of product from the latter strain allowed detailed product characterization.

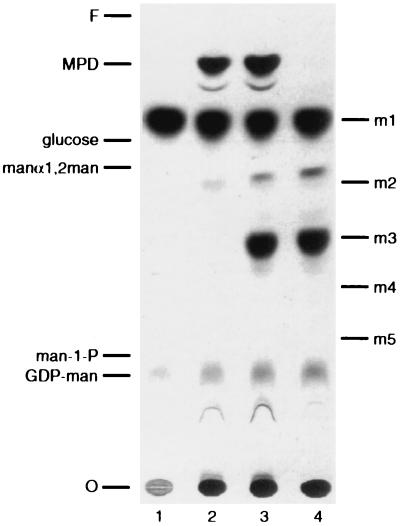

Reaction components were incubated with buffer and appropriate cation salts, after which the soluble components were recovered and analyzed by TLC as described in Materials and Methods. The TLC system used resolves individual hexoses as well as oligosaccharides that differ in linkage (see the standards in Fig. 2). When the reaction mixture was heated at 65°C for 10 min before incubation (Fig. 2, lane 1), the only radiolabeled species resolved on the plate were free mannose, presumably from label degradation, and a small amount of residual GDP-Man that was not removed during sample processing. When reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C, a radiolabeled species (termed product I) which comigrated with the GXM-derived mannotriose standard (m3) was detected. The appearance of this product depended on the presence of acceptor mannobiose (Fig. 2, compare lanes 2 and 3). The formation of product I was not affected by the addition of amphomycin to the reaction mixture (lane 4). The concentration of amphomycin used is sufficient to inhibit the formation of mannosyl-phosphoryl-dolichol (MPD) by cryptococcal membranes by over 97% (lane 4 and data not shown). This result indicated that transfer of mannose from the nucleotide sugar to the disaccharide acceptor does not require an MPD intermediate. Previous studies (30, 31) also suggest that mannose-containing lipid-linked intermediates are not involved in GXM synthesis.

FIG. 2.

Radiolabeled mannose is incorporated into a product that comigrates with GXM-derived mannotriose. C. neoformans Cap67 membranes were used to perform assays as described in Materials and Methods with the following modifications: lane 1, reaction components were heated (65°C; 10 min) before assay; lane 2, dimannoside substrate was omitted; lane 3, standard assay; lane 4, the reaction mixture was supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 and 0.45 μg of amphomycin/μl. An autoradiograph of the TLC is shown. O, origin; F, solvent front; man-1-P, mannose-1-phosphate; manα-1,2man, commercial α-1,2-mannobiose. The ladder of standards marked m1 through m5 corresponds to a series of linear oligomers containing one to five mannose residues in α-1,3 linkage (derived from hydrolysis of GXM mannan).

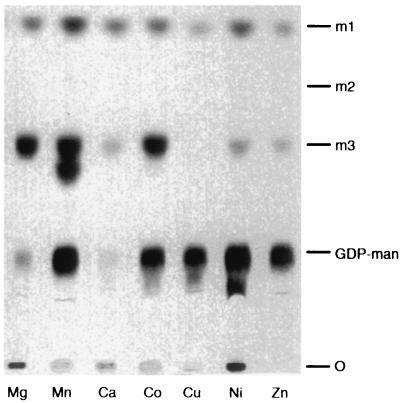

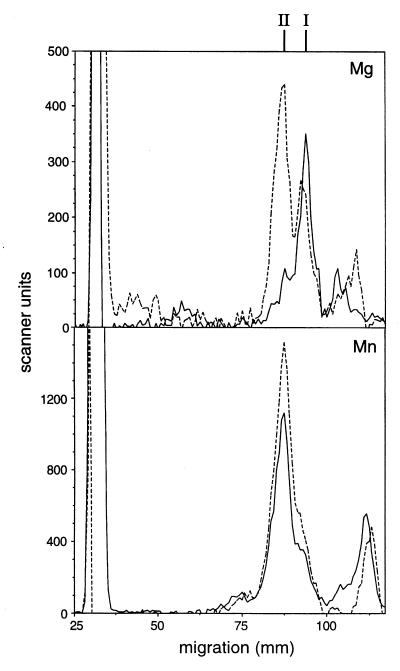

Addition of EDTA to mannosyltransferase assays abolished all activity (not shown), and assessment of cation preference showed maximal activity in the presence of manganese (Fig. 3). However, in the presence of this cation there was even greater production of an additional mannosylated species (product II) which migrated more slowly than the m3 standard (Fig. 3, second lane from left). This result suggested the presence of a second mannosyltransferase activity capable of modifying the disaccharide substrate. The formation of product II was also sensitive to EDTA and not affected by amphomycin (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Cation preference and detection of a second mannosyltransferase. Standard assays were performed in the presence of 10 mM chloride salts of the cations indicated, and an autoradiograph of the TLC plate is shown. Removal of unincorporated GDP-[3H]man was incomplete in several of the reactions. See the legend to Fig. 2 for abbreviations.

Chemical and enzymatic approaches were taken to analysis of both radiolabeled assay products isolated from preparative-scale reactions. Silica was recovered from the TLC plate region corresponding to each species, and the material was eluted for analysis (see Materials and Methods). In addition to its comigration on TLC with GXM-derived mannotriose (Fig. 2), product I coeluted with that standard from a Dionex CarboPac PA1 column (27a). Product II did not comigrate with any GXM-derived standard in either chromatographic system.

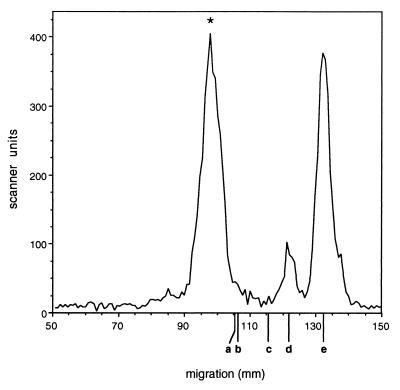

The radiolabeled assay products were also subjected to acid hydrolysis. Partial hydrolysis of product I yielded a radiolabeled disaccharide comigrating with commercial α-1,3-linked dimannoside, indicating that the newly added sugar was in that linkage (data not shown). In contrast, similar treatment of product II yielded a radiolabeled disaccharide which comigrated with commercial α-1,2-linked dimannoside, giving the first clue as to the new linkage which had been formed (Fig. 4). Complete hydrolysis of either product yielded free mannose, showing that the nucleotide sugar had not been metabolized (Fig. 4 and data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of product II by partial acid hydrolysis. Product II was isolated from large-scale reactions as described in Materials and Methods and was treated with 0.1 N HCl at 95°C for 2.5 h before TLC analysis. A scan of the TLC track is shown. ∗, position of migration of untreated material. The migration positions of nonradioactive standards are indicated below the abscissa. a, m3 standard; b, Man-α-1,6-Man; c, Man-α-1,3-Man; d, Man-α-1,2-Man; e, mannose.

To confirm the linkages enzymatically, each reaction product was analyzed with a range of mannosidases (Table 1). Product I was sensitive to an enzyme with broad α-mannosidase specificity and to one capable of cleaving both α-1,2 and α-1,3 bonds, as these treatments resulted in efficient release of the radiolabel as free mannose. However, it resisted digestion with a β-mannosidase or with enzymes specific for α-1,2 or α-1,6 linkages. These data, together with the hydrolysis results, show that the initially detected C. neoformans activity is an α-1,3 mannosyltransferase. This is consistent with the comigration of product I and the GXM standard containing only that linkage. Parallel enzyme digestions demonstrated that product II contains an α-1,2-linked mannose residue (Table 1), indicating that the second activity detected is an α-1,2 mannosyltransferase.

TABLE 1.

Mannosidase treatment of assay productsa

| Enzyme source | Enzyme specificity | % Product Ib

|

% Product IIb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mock | Treated | Mock | Treated | ||

| Jack bean | α1→2, α1→3, α1→6 | 5.3 | 64 | 4.8 | 76 |

| X. manihotis | α1→2, α1→3 | 3.2 | 62 | 2.0 | 63 |

| A. saitoi | α1→2 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 71 |

| X. manihotis | α1→6 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| H. pomatia | β linkages | 4.2 | 3.1 | 6.4 | 3.1 |

Each product was isolated from preparative reactions (see Materials and Methods), and aliquots were digested with the indicated mannosidases (Treated) or mock treated (Mock).

Values indicate the percent of total label which comigrated with free mannose after treatment, corresponding to successful degradation by the enzyme.

Because of the unique structure of the capsule and its importance for the virulence of C. neoformans, subsequent experiments focused on the α-1,3 mannosyltransferase, which demonstrates an activity appropriate for a role in GXM synthesis. The α-1,2-linked species (product II) predominated at a lower pH and in the presence of manganese (Fig. 5). For this reason standard conditions of pH 8.5 and 15 mM magnesium were chosen to simplify analysis; under these conditions only product I is formed from α-1,3-mannobiose (Fig. 3 and data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effect of pH and cations on formation of products I and II. Assays were performed at pH 7.5 (dashed lines) or 8.5 (solid lines) in the presence of Mg or Mn as indicated, and the TLC plate was scanned. The abscissa is expanded to clarify the separation between the two products, and the region towards the solvent front (containing only free mannose) is not shown. The peak extending beyond the plot frame is at the plate origin. The ordinate is in arbitrary scanner units, and product peaks are identified above the top panel.

Introduction of free mannose as the sole exogenous substrate under standard conditions yielded a radiolabeled disaccharide. This consisted primarily of Man-α-1,2-Man and contained no α-1,3-linked material (not shown). Use of α-1,3-linked trimer as an assay substrate did not yield any detectable tetramer product (not shown), but the material available did not permit assaying this substrate at concentrations comparable to those of the dimer.

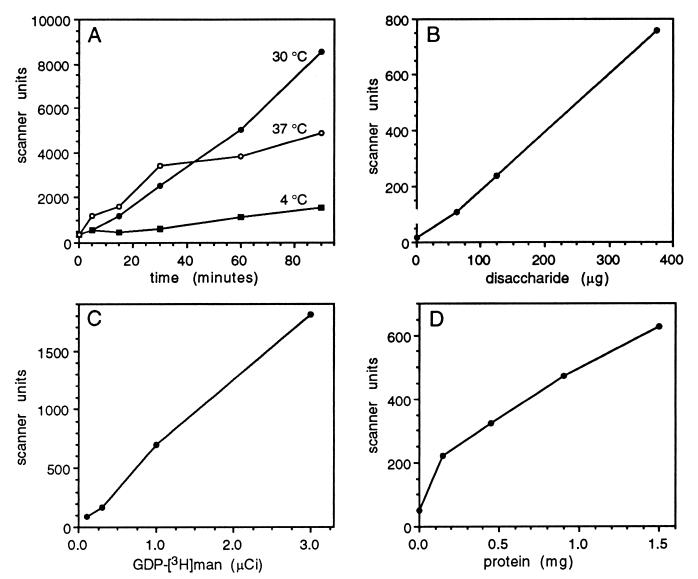

Preliminary characterization of the α-1,3 mannosyltransferase showed robust product synthesis at 30°C, the temperature which allows the most rapid growth of C. neoformans in the laboratory (Fig. 6A). There was also substantial activity at 37°C, as would be required for function in a mammalian host, although this reached a plateau after about 40 min. The pH optimum of the activity was 8.0 (data not shown). Product synthesis was dependent on the amount of disaccharide acceptor and mannose donor present in the reaction (Fig. 6B and C), as well as the protein concentration (Fig. 6D). To further characterize the reaction, the effects of compounds related to GDP-mannose or known to alter sugar metabolism were tested; these data are shown in Table 2.

FIG. 6.

Preliminary characterization of α-1,3 mannosyltransferase activity. Standard assays were performed and analyzed by TLC. The TLC plates were scanned, and the area under each peak which comigrated with the m3 standard was plotted in arbitrary scanner units. (A) Time course of activity at the three temperatures indicated; (B) dependence of activity on amount of disaccharide acceptor; (C) dependence on nucleotide sugar; (D) dependence on cryptococcal protein.

TABLE 2.

Effects of potential inhibitors on α-1,3 mannosyltransferase activity

| Addition to assay | Concn | % Control activitya |

|---|---|---|

| None | 100 | |

| EDTA | 10 mM | 4 |

| Tunicamycin | 20 μg/ml | 99 |

| CaCl2 | 5 mM | 79 |

| Amphomycin-CaCl2b | 0.45 mg/ml-5 mM | 77 |

| GMP | 1 mM | 75 |

| GDP | 1 mM | 51 |

| GTP | 1 mM | 80 |

| Mannose | 5 mM | 75 |

| Mannose-1-phosphate | 5 mM | 63 |

Quantitation was done as described for Fig. 5, with values normalized to the control reaction with no additions.

Amphomycin was tested in the presence of 5 mM CaCl2; the appropriate control is listed in the previous row.

In a standard reaction (1 h; 30°C) 20% of the radiolabel introduced as GDP-[3H]mannose was recovered in uncharged form. Of this material, 15% was incorporated into product I, 9% was free mannose, and the remainder was in compounds that did not leave the origin of the TLC plate. The last material may reflect incorporation of radiolabel into capsule fragments present in the enzyme preparation. The Km for the nucleotide sugar was approximately 1 μM, but detailed kinetic studies will require protein purification to avoid interference by endogenous transferase substrates.

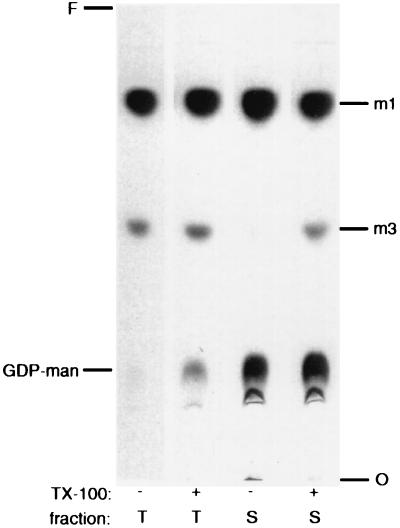

To examine membrane association of the α-1,3 mannosyltransferase activity, membranes were incubated with Triton X-100 and then subjected to ultracentrifugation (Fig. 7). The activity in total membranes was slightly stimulated when Triton X-100 was added to the assay (Fig. 7, compare lanes 1 and 2). This higher level of product formation was almost completely recovered in a high-speed supernatant fraction after membrane solubilization in a final concentration of 1% Triton X-100 (lane 4). In contrast, the supernatant fraction from unextracted membranes demonstrated little activity (lane 3).

FIG. 7.

α-1,3 mannosyltransferase activity is solubilized by Triton X-100. Aliquots of membranes were incubated for 30 min on ice in the presence of 1% Triton X-100 (+) or an equal volume of water (−). The membranes were then either kept on ice for an additional 30 min before assay (total membranes [T]) or subjected to centrifugation (100,000 × g; 30 min; 4°C), with only the supernatant fraction (S) assayed. An autoradiograph of the TLC plate is shown. See the legend to Fig. 2 for abbreviations.

It was important to determine whether the α-1,3 mannosyltransferase activity was present in membranes from the model yeast S. cerevisiae. The availability of genome sequences and abundant genetic tools for this organism could greatly facilitate the study of such an enzyme. However, as S. cerevisiae does not produce a similar polysaccharide capsule, perhaps expression of the same transferase would not be expected. Tests of S. cerevisiae membranes prepared and assayed under conditions identical to those used with C. neoformans demonstrated that they produced no detectable amounts of product I in standard reactions (not shown). Membranes of Candida albicans, a nonencapsulated pathogenic fungus, were also tested in standard assays. These membranes produced no product I but instead modified the assay substrate to form both product II and the branched mannose trimer Man-α-1,6-(Man-α-1,3)-Man, a structure similar to that formed at several branch points of N-glycan synthesis (11).

DISCUSSION

The C. neoformans polysaccharide capsule is a fascinating structure with multiple roles in the biology of this fungal organism. Mutant cells which are defective in capsule production are avirulent in animal models; correction of the defects by complementation restores both capsule production and the ability to cause fatal infection (4–6). Encapsulated organisms can deplete host complement by fixing it with great efficiency and are resistant to phagocytosis and killing by host effector cells. This leads to a reduction in host immune responses, such as cytokine production and antigen presentation (reviewed in reference 3). GXM is the dominant capsule component and plays a clear role in inhibiting host response. High serum or cerebrospinal fluid levels of this antigen also correlate with poor clinical prognosis (21). GXM is also the best-described capsule component in terms of its structure, due to extensive study by Cherniak and coworkers (8). Because of the unique structure of GXM, understanding its biosynthesis will yield information of biochemical interest. Since current therapy for cryptococcosis is inadequate, an additional goal of this work is to identify potential targets for antifungal agents.

This paper describes an α-1,3 mannosyltransferase, an enzyme with specificity consistent with a role in synthesis of the mannose backbone of GXM. This membrane-associated activity is robust at temperatures experienced by the fungus both in the environment (where it is ubiquitous) and in the infected mammalian host. The most likely function of this enzyme is synthesis of GXM. The second capsular mannan, GalXM, also contains mannose in α-1,3 linkage, but it is added to an α-1,4-linked mannose residue, making it less likely that the same enzyme serves both functions.

The structure of GXM is novel in containing multiple sequential mannose residues in α-1,3 linkage. The only other place that two sequential α-1,3 mannosyl linkages have been described in eukaryotes is at the distal end of some O-linked oligosaccharides of S. cerevisiae (22, 23). The first of these bonds, added in a reaction mediated by Mnn1p (12, 33), extends an α-1,2-linked mannose and would therefore probably be synthesized by an enzyme of different specificity than the capsular transferase. The last mannose should be added to a glycan similar to the substrate used in this assay, but the enzyme responsible for formation of this bond has not been characterized; its existence has been inferred from structural information. To see whether comparable activities were present in S. cerevisiae and C. neoformans, parallel assays were performed in membranes from each. Under standard assay conditions the α-1,3 mannosyltransferase was not active in S. cerevisiae membranes, although when conditions of cations and pH were altered, an α-1,3 transfer activity was detected (data not shown). No α-1,3 mannosyltransferase was detected under any conditions in the unencapsulated pathogenic fungus C. albicans. These results are consistent with the idea that the α-1,3 transferase described in this work is unique to C. neoformans and that it is likely to play a role in GXM construction.

In these experiments radiolabeled products larger than trisaccharides were not detected. Because the substrate was in substantial molar excess over the radiolabel under standard assay conditions, it is not surprising that only a single round of addition would occur. On the other hand, if this enzyme functions in the construction of an extensive linear mannan, it might be expected to display processivity. One possible explanation for the absence of evidence for processivity is that a factor required for this behavior was absent or inactive in the membranes prepared for these assays. Another possibility is based on the structure of GXM, which is composed of repeating mannose trimers with their associated side chains (7, 8). It is conceivable that individual trimannose units are constructed and modified with side chains before the polymer is assembled. Kinetic and substrate studies will address these mechanistic questions in the future, once enzyme purification has progressed.

A second mannosyltransferase present in wild-type cryptococcal membranes was discovered in the course of this work and shown to form α-1,2 linkages. The precise position of mannose attachment was not determined in these experiments, as the results from both enzymatic and chemical degradation experiments are consistent with either a linear mannose trimer (Man-α-1,2-Man-α-1,3-Man) or the branched structure Man-α-1,2-(Man-α-1,3)-Man. It is most likely that the product is a linear species, because it migrates fairly close to the linear standard derived from GXM (Fig. 3), separated by a distance similar to that which separates α-1,3- and α-1,2-linked dimer standards (Fig. 2). Branched species exhibit very different behavior on this TLC system (not shown). Additionally, neither O-linked, N-linked, nor glycosyl phosphatidylinositol structures of yeasts that have been described contain the branched-structure motif (11).

Mannose in α-1,2 linkage is not found in either GXM or GalXM (28). It may be present, however, in the mannoprotein component of the capsule (4% by mass [7]). Protein-linked glycans of C. neoformans have not been analyzed directly, but examination of these structures in S. cerevisiae may be instructive in suggesting a role for the α-1,2 mannosyltransferase activity. While adjacent α-1,2 and α-1,3 linkages between mannose residues do occur in O-linked glycans of S. cerevisiae, they are present in reverse order to the structure probably formed here (24). However, there are two occasions during core N-glycan synthesis when Man-α-1,2-Man-α-1,3-Man is made. One is when the fourth mannose of the dolichol-linked core oligosaccharide is added, forming a branch from the chitobiose core which corresponds to this trimer (Fig. 8, lower shaded region). This addition only occurs after the third core mannose is added (by Alg2p in yeast [[14]) to form a branched structure. As no branched tetramer occurred in these assays, it is unlikely that the observed activity performs an analogous function. The Man-α-1,2-Man-α-1,3-Man sequence is also formed when the eighth mannose is added during the MPD-dependent extension of Man5GlcNAc2 structure that occurs later in core oligosaccharide synthesis (Fig. 8, upper shaded region). The activity described here is not dependent on the presence of MPD, as it resists inhibition by amphomycin (data not shown). Therefore, it is likely that either (i) this transferase is involved in as-yet-undefined steps of glycan synthesis in cryptococcus or (ii) it participates in N glycosylation but has characteristics different from those of previously described enzymes. Further study of this activity should differentiate between these interesting possibilities.

FIG. 8.

Structure of the Man9GlcNAc2 N-glycan precursor. The shaded regions correspond to the two Man-α-1,2-Man-α-1,3-Man trimers considered in the discussion. All linkages to mannose are α. Core refers to the chitobiose portion of the N-glycan, which is linked to protein.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to Robert Haltiwanger, Arturo Casadevall, Paul Englund, Robert Cherniak, Jochen Buck, Alvaro Acosta-Serrano, Tim McGraw, and members of my laboratory for helpful discussions about this project. I thank Robert Haltiwanger and Jochen Buck for constructive comments on the manuscript, and I greatly appreciate the assistance of Robert Haltiwanger and Ulf Sommer in obtaining Dionex data cited in this work. I particularly thank Robert Cherniak for his generosity in providing GXM-derived materials, Sam Turco for amphomycin, and Randy Schekman and Arturo Casadevall for strains.

T.L.D. is supported by a Burroughs Wellcome Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergman F. Studies of capsule synthesis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Sabouraudia. 1965;2:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloomfield N, Gordon M A, Elmendorf D F., Jr Detection of Cryptococcus neoformans antigen in body fluids by latex particle agglutination. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1963;114:64–67. doi: 10.3181/00379727-114-28586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchanan K L, Murphy J W. What makes Cryptococcus neoformans a pathogen? Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:71–83. doi: 10.3201/eid0401.980109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang Y C, Kwon-Chung K J. Complementation of a capsule-deficient mutation of Cryptococcus neoformans restores its virulence. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4912–4919. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang Y C, Kwon-Chung K J. Isolation of the third capsule-associated gene, CAP60, required for virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2230–2236. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2230-2236.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang Y C, Penoyer L A, Kwon-Chung K J. The second capsule gene of Cryptococcus neoformans, CAP64, is essential for virulence. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1977–1983. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1977-1983.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherniak R, Sundstrom J B. Polysaccharide antigens of the capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1507–1512. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1507-1512.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherniak R, Valafar H, Morris L C, Valafar F. Cryptococcus neoformans chemotyping by quantitative analysis of 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of glucuronoxylomannans with a computer-simulated artificial neural network. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:146–159. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.2.146-159.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Currie B P, Casadevall A. Estimation of the prevalence of cryptococcal infection among patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:1029–1033. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.6.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dismukes W E. Management of cryptococcosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(Suppl. 2):S507–S512. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_2.s507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gemmill T R, Trimble R B. Overview of N- and O-linked oligosaccharide structures found in various yeast species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1426:227–238. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham T R, Seeger M, Payne G S, MacKay V L, Emr S D. Clathrin-dependent localization of α 1,3 mannosyltransferase to the Golgi complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:667–678. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granger D L, Perfect J R, Durack D T. Virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Regulation of capsule synthesis by carbon dioxide. J Clin Investig. 1985;76:508–516. doi: 10.1172/JCI112000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson B J, Kukurazinska M A, Robbins P W. Biosynthesis of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the alg2 mutation. Glycobiology. 1993;3:357–364. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson E S, Ayers D J, Harrell A C, Nicholas C C. Genetic and phenotypic characterization of capsule mutants of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:1292–1296. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.3.1292-1296.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson E S, Jenkins N D, Todd J M. Relationship between superoxide dismutase and melanin in a pathogenic fungus. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4085–4086. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.4085-4086.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan M H, Rosen P P, Armstrong D. Cryptococcosis in a cancer hospital. Cancer. 1977;39:2265–2274. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197705)39:5<2265::aid-cncr2820390546>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozel T R. Virulence factors of Cryptococcus neoformans. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:295–299. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88957-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozel T R, Cazin J., Jr Nonencapsulated variant of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1971;3:287–294. doi: 10.1128/iai.3.2.287-294.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Littman M L. Capsule synthesis by Cryptococcus neoformans. Trans NY Acad Sci. 1958;20:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.2164-0947.1958.tb00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell T G, Perfect J R. Cryptococcosis in the era of AIDS—100 years after the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:515–548. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakajima T, Ballou C E. Characterization of the carbohydrate fragments obtained from Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan by alkaline degradation. J Biol Chem. 1979;249:7679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orlean P. Biogenesis of yeast wall and surface components. In: Pringle J R, Broach J R, Jones E W, editors. The molecular and cellular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces. Vol. 3. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1997. pp. 229–362. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orlean P. Dolichol phosphate mannose synthase is required in vivo for glycosyl phosphatidylinositol membrane anchoring, O mannosylation, and N glycosylation of protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5796–5805. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.5796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivera J, Feldmesser M, Cammer M, Casadevall A. Organ- dependent variation of capsule thickness in Cryptococcus neoformans during experimental murine infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5027–5030. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.5027-5030.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider P, Ralton J E, McConville M J, Ferguson M A. Analysis of the neutral glycan fractions of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositols by thin-layer chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1993;210:106–112. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schutzbach J S, Ankel H. Multiple mannosyl transferases in Cryptococcus laurentii. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:2187–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27a.Sommer, U., R. Haltiwanger, and T. L. Doering. Unpublished data.

- 28.Vaishnav V V, Bacon B E, O’Neill M O, Cherniak R. Structural characterization of the galactoxylomannan of Cryptococcus neoformans CAP67. Carbohydr Res. 1998;306:315–330. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(97)10058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vartivarian S E, Anaissie E J, Cowart R E, Sprigg H A, Tingler M J, Jacobson E S. Regulation of cryptococcal polysaccharide by iron. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:186–190. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White C W, Cherniak R, Jacobson E S. Side group addition by xylosyltransferase and glucuronyltransferase in biosynthesis of capsular polysaccharide in Cryptococcus neoformans. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:289–301. doi: 10.1080/02681219080000381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White C W, Jacobson E S. Mannosyl transfer in Cryptococcus neoformans. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:129–133. doi: 10.1139/m93-019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson D E, Bennett J E, Bailey J W. Serologic grouping of Cryptococcus neoformans. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1968;127:820–823. doi: 10.3181/00379727-127-32812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yip C L, Welch S K, Klebl F, Gilbert T, Seidel P, Grant F J, O’Hara P J, MacKay V L. Cloning and analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MNN9 and MNN1 genes required for complex glycosylation of secreted proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2723–2727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]