Abstract

Background: Emotional problems such as depression and anxiety are very serious among college students, especially during the COVID-2019 pandemic. The present study aimed to explore the mediating role of resilience in the relationship between self-concept and negative emotion, and the moderating role of exercise intensity in the direct and indirect effect of self-concept on negative emotion among college students. Methods: A total of 739 Chinese college students aged between 18 and 25 years (M = 20.13; SD = 1.67) were selected to complete the Tennessee Self-Concept Scale (TSCS), the Depression Anxiety Stress Self Rating Scale, the Adolescent Psychological Resilience Scale, and the Physical Exercise Scale (PARS-3) to assess self-concept, negative emotions, psychological resilience, and exercise intensity, respectively. Hayes’ PROCESS macro for SPSS was used to test the relationships among these variables. Results: Self-concept was negatively correlated with negative emotions; psychological resilience partially mediated the association between self-concept and negative emotions; exercise intensity moderated the effect of self-concept on negative emotions, and college students with low intensity physical activity would strengthening the association between self-concept and psychological resilience, psychological resilience, and negative emotions. Conclusions: Psychological resilience is a critical mediating mechanism through which self-concept is associated with negative emotions among college students, and exercise intensity plays a role as a moderating variable in the direct and indirect influence of self-concept on negative emotions. Implications for preventing or reducing negative emotions are discussed.

Keywords: self-concept, negative emotion, psychological resilience, exercise intensity

1. Introduction

During the COVID-2019 pandemic, college students faced various major life challenges. They had to do e-learning and lost face-to face contact with teachers or classmates, which deteriorated their mental health and increased levels of stress and loneliness. If they cannot adapt to the changes brought by these life events, they will be prone to negative emotions, and their physical and mental health may be seriously affected. Negative emotions refer to one’s unpleasant experiences, which become manifest in the form of anxiety [1], depression [2], and stress [3], all of which are prevalent among contemporary college students. Individuals who are not skillful at dealing with negative emotions are susceptible to psychological problems and even mental diseases. Studies have shown that patients with major depressive disorder have difficulties processing negative emotions, in which context enhanced limbic activation has been observed [4]. Research pertaining to the factors influencing negative emotions has theoretical and practical implications for reducing the level of negative emotions and mitigating the associated psychological problems or diseases.

Several factors contribute to negative emotions, including personality traits [5], life satisfaction and happiness [6], cognitive impairment [7], etc. Among them, self-concept is widely cited. As an organized system that shapes how individuals feel about themselves, other individuals, and their social relationships [8], self-concept is closely related to mental health among college students, and there are negative correlation between self-concept scores and depression, interpersonal sensitivity, psychosis, and obsessive-compulsive disorder [9]. The lower the quality of college students’ self-concept construction, the higher the proportion of college students exhibiting psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, and even suicidal behavior [10]. This close relationship between self-concept and emotion was also identified among other groups [11,12]. For example, Lohbeck and colleagues [12] examined the relationship between German teachers’ self-concept and three emotions (enjoyment, anger, anxiety), and they found that teachers’ self-concepts were positively related to enjoyment and negatively related to anxiety and anger. Moreover, resilience is considered to be a protective factor against negative emotions, such as depressive syndromes and anxiety disorders [13], which enables a person to manage adversity and maintain stable emotional health, control of the environment, and a positive outlook [14,15]. Interestingly, some studies have noted that there are significant positive correlations and predictive ability between self-concept and psychological resilience in practice nurses [16], migrant children [17], vocational students [18], college freshmen [19], and other groups, as verified by correlation and regression analysis. In addition, it has been suggested that psychological resilience mediates and moderates the process of depression [20,21]. However, whether self-concept affects negative emotions by affecting psychological resilience remains unclear. Given these facts, further research on the relationship between self-concept and negative emotions is needed to develop better rational interventions to reduce the impact of negative emotions.

It has been well documented that physical activity can improve individuals’ emotional states and reduce their negative emotions [14,22,23,24]. However, the effect of the intensity of physical exercise on emotions has not been observed consistently [25]. Some studies indicated that moderate- or high-intensity exercise improved emotions [26,27,28,29,30,31]. For example, Balchin and colleagues [26] investigated the effect of exercise intensity on depression among moderately depressed males, and they found that moderate- and high-intensity exercise improved depression levels, while very-low intensity exercise did not have as beneficial an effect. However, other researchers have not indicated intensity-related differences in mood change [32,33,34]. In a study by Buscombe et al. [32], results showed that individuals’ affective change occurred when exercising at different intensities, but a self-selected intensity was the most beneficial for producing affective changes, indicating the effect of exercise intensity on emotions may be moderated by the individual’s state. The differences reported in existing studies may be due to researchers either focused only on the direct effect of exercise on emotion, or paid attention to the effect of exercise intensity on a specific pathway, lack of attention to the impact of exercise on emotion from a multi-level perspective. We supposed that the influence of exercise on emotion is multifaceted. Therefore, the moderating role of exercise intensity in the direct and indirect effect of self-concept on negative emotions was examined in this study.

Although previous studies have evidence that self-concept is significantly correlated with negative emotions, the underlying mechanism of the relationship between self-concept and negative emotion has not been thoroughly discussed. The present study was designed to extend existing knowledge about the relationship between self-concept and negative emotion. Different from previous studies, in addition to exploring the mediating role of psychological resilience in the relationship between self-concept and negative emotion, we also focused on the moderating role of exercise intensity in the direct and indirect effect of self-concept on negative emotion among college students.

Based on previous studies, we put forward the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

Self-concept can negatively predict negative emotions.

Hypothesis 2.

Psychological resilience plays a mediating role between self-concept and negative emotions.

Hypothesis 3.

Exercise intensity would moderate the direct and indirect relations between self-concept and negative emotions.

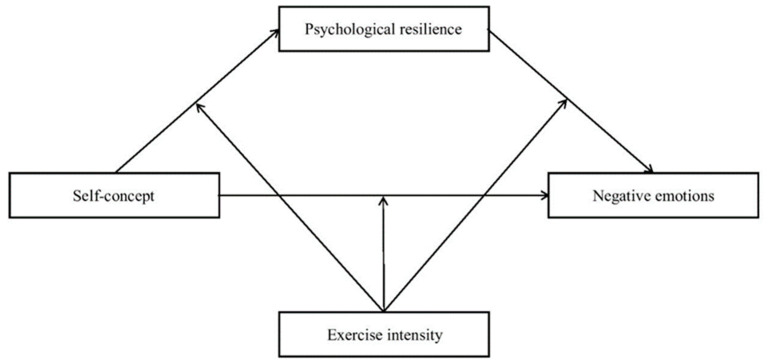

These hypotheses were examined by a moderated mediation model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The proposed moderated mediation model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The present study recruited college students from Nantong University in Jiangsu province, China, using a convenience sampling method. The data were collected by administering an anonymous electronic questionnaire on the WenJuanXing public online platform (https://www.wjx.cn, accessed on 3 April 2022), and 756 college students completed the questionnaire during 9 October to 25 October 2021.

To enhance the quality of data collection, the researchers explained the research purpose and schedule to the participants and informed them that their participation was voluntary. Moreover, the participants were assured that all questionnaires would be kept confidential, and all data would be used for scientific research purposes only. All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nantong University (2020-041).

The invalid data were eliminated according to the following criteria: 1. Respondents completed the survey in less than 120 s; 2. Answers to all items were similar; Seventeen invalid questionnaires were excluded, leaving 739 valid questionnaires for further analysis (effective rate = 98%). Among the participants, 371 (50.2%) were male, the age range was from 18 to 25, with an average age of 20.13 years (SD = 1.67).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Self-Concept

The Tennessee Self-Concept Scale (TSCS) revised by Lin [35] was used to measure self-concept. The scale includes ten factors: self-identity, self-satisfaction, self-action, physical self, moral self, psychological self, family self, social self, self-criticism and comprehensive status. The statements were assessed on a five-point Likert-scale that ranged from 1 (completely false) to 5 (completely true). According to the composite score, a higher score corresponds to more positive self-concept. Cronbach’s alpha for the present sample was 0.89.

2.2.2. Negative Emotions

The short version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) [36] was used to assess negative emotions of college students. The scale has been proved to have good reliability and validity in Chinese culture [37]. The scale contains 3 subscales: 7-item depression, 7-item anxiety, and 7-item stress. Items were rated from 0 (never true) to 3 (always true), with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress. Cronbach’s alpha for the present sample was 0.92.

2.2.3. Psychological Resilience

The 27-item Adolescent Psychological Resilience Scale developed by Hu and Gan [38] was administered to assess resilience, the scale has good reliability and validity in Chinese culture. Each item is rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (always true), and the higher score is corresponding to higher level of psychological resilience. This scale was developed with two factors: personal strength and support. Personal strength includes goal focus, emotional control, and positive cognition; support includes family support and interpersonal assistance. Cronbach’s alpha for the present sample was 0.85.

2.2.4. Exercise Intensity

The three-question Physical Activity Rating Scale (PARS-3) revised by Liang [39] was adopted, namely the intensity, time and frequency of physical activity, 5-point Likert scale was adopted for quantification, scoring from 1 to 5 points, and thus measure the intensity of participation in physical activity. Physical activity score = activity intensity score × (activity time score − 1) × activity frequency score, score interval 0 to 100 points. The scale of physical activity is: low intensity physical activity ≤ 19 points, moderate-intensity physical activity ≤ 20–42 points, and high intensity physical activity ≥ 43 points. Data of participants with high and low intensity physical activity according to their scores were selected to analyze the moderating role of physical exercise intensity in present study.

2.3. Data Analyses

To test correlations among variables (Hypothesis 1), descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analysis were inspected.

To examine the mediation effect of psychological resilience (Hypothesis 2), Model 4 of the PROCESS macro in SPSS21.0 was utilized [40]. We conducted bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to determine the mediation effect. If the bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence interval (CI) did not include zero, it indicated a significant mediation effect at the level of α = 0.05.

To test the moderating role of physical exercise intensity in indirect and direct effects of self-concept on negative emotions (Hypothesis 3), Model 59 of the PROCESS macro was used. We performed bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to verify the significance of the moderation effect.

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Deviation Test

In order to avoid common methodological deviations, the Harman single factor method was used for statistical control, the results showed that there were 23 factors with a characteristic value greater than 1, and the first factor explained a variation of 25.02%, which was far less than the 40% critical value. Therefore, the influence of common method deviation on the results of this study can be excluded.

3.2. Correlation Analysis

Means, standard deviation, and correlation analysis of each variable in this study were shown in Table 1. All variables were significantly correlated with each other. Among them, self-concept was significant positively correlated with psychological resilience and exercise intensity, and negative emotions were significant negatively correlated with self-concept, psychological resilience and exercise intensity, indicating that the data was suitable for further model testing and analysis. Hypothesis 1 is therefore supported.

Table 1.

The mean, standard deviation and correlation analysis of each variable (r).

| M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Self-concept | 266.3 ± 25.758 | 1 | |||

| 2 Psychological resilience | 98.13 ± 13.213 | 0.696 *** | 1 | ||

| 3 Negative emotion | 30.92 ± 8.704 | −0.653 *** | −0.582 *** | 1 | |

| 4 Exercise intensity | 23.99 ± 26.632 | 0.148 ** | 0.225 ** | −0.102 * | 1 |

Note. N = 739. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. All values are reserved with three decimal places, same below.

3.3. Psychological Resilience as a Mediator

In Hypothesis 2, we predicted that resilience would mediate the relationship between self-concept and negative emotion. Thus, Model 4 of the PROCESS macro was used to test this hypothesis in 739 participants. The results in Table 2 showed that self-concept significantly predicted psychological resilience (b = 0.361, p < 0.001) and negative emotions (b = −0.223, p < 0.001), and psychological resilience significantly predicted negative emotions (b = −0.164, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of self-concept on negative emotions via psychological resilience was significant, with an indirect effect of −0.059, 95% CI = [−0.085, −0.034].

Table 2.

Testing the mediation effect of self-concept on job negative emotion.

| Predictors | Negative Emotion | Psychological Resilience | Negative Emotion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | b | t | |

| Self-concept | −0.223 | −23.349 *** | 0.361 | 26.229 *** | −0.164 | −12.687 *** |

| Psychological resilience | −0.164 | −6.557 *** | ||||

| R² | 0.426 | 0.484 | 0.458 | |||

| F | 545.159 *** | 687.971 *** | 309.675 *** | |||

Note. N = 739. *** p < 0.001. All values are reserved with three decimal places, same below.

In addition, after filtering the data and adding moderator variable, self-concept significantly predicted psychological resilience (b = 0.363, p < 0.001) and negative emotions (b = −0.222, p < 0.001), and psychological resilience significantly predicted negative emotions (b = −0.141, p < 0.001). The Bootstrap test showed that the 95% CI = [−0.245, −0.199]. Thus, the results in Table 2 and Table 3 suggested that resilience play a partial mediating role, and therefore Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Table 3.

Moderated mediation model test results.

| Predictors | Negative Emotion | Psychological Resilience | Negative Emotion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | b | t | |

| Self-concept | −0.222 | −19.197 *** | 0.363 | 23.331 *** | −0.168 | −10.474 *** |

| Exercise intensity | −0.031 | −0.091 | ||||

| Psychological resilience | −0.141 | −4.502 *** | ||||

| Psychological resilience × Exercise intensity | 0.073 | 2.762 * | ||||

| Self-concept × Exercise intensity | −0.048 | −2.682 ** | −0.027 | −1.575 | ||

| R² | 0.402 | 0.498 | 0.431 | |||

| F | 368.518 *** | 544.318 *** | 103.451 *** | |||

Note. Each column is a regression model that predicts the criterion at the top of the column. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

3.4. Exercise Intensity as a Moderator

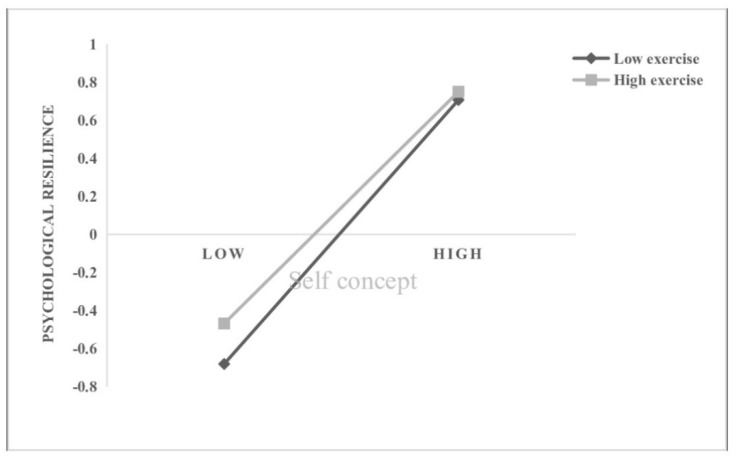

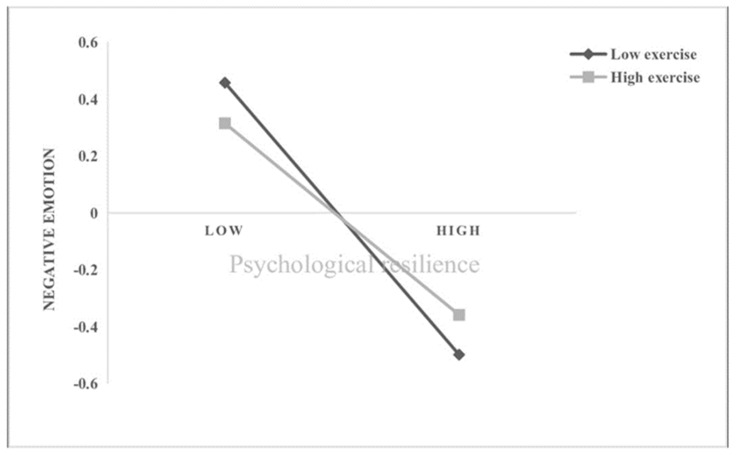

In Hypothesis 3, exercise intensity was anticipated as a moderator variable to moderate all pathways in the mediation process. According to scores in PARS-3, participants with high (N = 154, mean = 63.23) or low (N = 397, mean = 8.76) exercise intensity were selected for the moderated mediation analysis in Model 59 of PROCESS macro. As shown in Table 3, the interaction term between self-concept and exercise intensity can significantly predict psychological resilience (b = 0.048, t = −2.682, p < 0.01), and the interaction term between psychological resilience and exercise intensity can significantly predict negative emotions (b = 0.073, t = 2.762, p < 0.05). That is, exercise intensity plays a moderating role in the effect of self-concept on psychological resilience, and the effect of psychological resilience on negative emotions. Furthermore, we conducted a simple slope analysis and plotted the effect of self-concept on psychological resilience separately for college students with high or low exercise intensity (Figure 2). The results showed that compared with high exercise intensity group (bsimple = 0.283, p < 0.001), higher levels of self-concept were more strongly predictive of higher levels of psychological resilience among college students with low exercise intensity (bsimple = 0.379, p < 0.001). That is, low exercise intensity may exacerbate the association between self-concept and psychological. Similarly, we also performed a simple slope analysis and plotted the effect of psychological resilience on negative emotions separately for college students with high or low exercise intensity (Figure 3). The simple slope test showed that the higher levels of psychological resilience was predictive of lower level of negative emotions among college students with low exercise intensity = (bsimple = −0.182, p < 0.001), while the conditional indirect effect of self-concept on negative emotion via psychological resilience was weaker when exercise intensity was low (bsimple = −0.036, p > 0.05), indicating that the mediating effect of psychological resilience gradually weakened as the exercise intensity increased.

Figure 2.

Exercise intensity as a moderator in the relationship between self–concept and psychological resilience.

Figure 3.

Exercise intensity as a moderator in the relationship between psychological resilience and negative emotion.

However, the bootstrapping results showed that the direct effect of self-concept on negative emotions was not moderated by exercise intensity, the index of moderated effect being −0.013, SE = 0.014, 95% CI = [−0.013, 0.040]. Specifically, the conditional indirect effect in low exercise intensity (b = −0.56, 95% CI = [−0.26, −0.20]) or high exercise intensity (b = −0.20, 95% CI = [−0.25, −0.16]) did not show significant differences. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was partially supported.

4. Discussion

Our study paid attention to self-concept and negative emotions among college students, trying to revealing possible mediating and moderating mechanisms underlying the relationship between self-concept and negative emotions. As predicted and consistent with previous studies [41], our survey results showed that self-concept was significantly negatively correlated with negative emotions. That is, the more positive one’s self-concept was, the less likely one would experience negative emotions when encountering stressful events. Our findings are similar to Showers et al. [42] research, which have found that individuals with a positive self-concept tend to have a more positive mood and higher self-esteem.

We also explored the mediating role of psychological resilience and the moderating role of exercise intensity in the relationship between self-concept and negative emotion. Existing data showed that psychological resilience had a significant mediating effect on the relationship between self-concept and negative emotions. College students with more positive self-concept were more likely to develop psychological resilience [43], and had less negative feelings. Our results reconfirmed the effect of psychological resilience on self-concept and negative emotion, and further extended the existing researches. People who have a clear, swiftly developed, and stable view of themselves are better able to make sense of their life experiences, feel less vulnerable to being affected negatively by challenging situations, and consistently communicate their needs and desires in interpersonal interactions [44,45,46]. Individuals with high levels of psychological resilience are better able to cope with acute or chronic adversity and setbacks [47,48]. After successfully resolving difficulties, the clarity of one’s self-concept is improved in terms of personal ability and self-efficacy [42], resulting in a higher level of psychological resilience. Therefore, it is extremely important to develop a positive self-concept and psychological resilience. These finding provides implications within the process of education; we should therefore adopt a targeted approach in accordance with the characteristics of self-concept formation and the development of students at different ages to promote the steady formation of a self-concept. Such as vulnerable groups [49] or those with a negative self-concept, need more attention and development of their psychological resilience, or reduce the impact of negative emotions on them by increasing the intensity of exercise.

In addition, the hypothesis of the moderating effect of exercise intensity was partially supported. Specifically, the relationship between self-concept and psychological resilience and the relationship between psychological resilience and negative emotion is moderated by exercise intensity, while the moderating effect of exercise intensity on the relationship between self-concept and negative emotion is not significant. Moderate-intensity exercise can help adolescents maintain a healthy body and improve their cognitive ability [50] and can allow them to perform better when dealing with frustration in a competitive environment, thus increasing their psychological resilience. Our results showed that the relationship between self-concept and psychological resilience was stronger for college students who experienced lower exercise intensity than those who experienced higher exercise intensity, indicating that college students’ psychological resilience level was more strongly affected by their self-concept among low exercise intensity group. However, among high-intensity group, other factors, such as the volitional regulation of will power via physical exercise [51], would weaken the impact of self-concept on psychological resilience. Moreover, our findings indicated that psychological resilience level can significantly negatively predict negative emotions among low exercise intensity group, while in the high exercise intensity group, psychological resilience level cannot predict negative emotions. This finding may be due to the fact that the higher frequency and longer duration of physical exercise serves as a direct vent of negative emotions [24], no matter their psychological resilience level is high or not in the high exercise intensity group. However, among the low exercise intensity group, college students need higher levels of psychological resilience to mitigate and adapt to setbacks and stressful events (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic), thereby reducing their negative emotional experiences. These results suggest that physical activity can more effectively improve individuals’ psychological resilience and decrease their negative emotion, especially for those engage in low exercise intensity. Our results showed that high and low exercise intensity had different effects on the relationship between self- concept and negative emotion. On the one hand, this result is helpful in order to deeply understand the internal mechanism of exercise intensity affecting emotion. On the other hand, it also explains the difference of existing research results to a certain extent [52,53,54].

Although the present study advances our understanding of the relationship between self-concept and negative emotions, some limitations need to be taken into consideration. First, we relied on cross-sectional data in this study; causal conclusions regarding the cross-sectional findings must be interpreted cautiously, and future research might implement prospective and longitudinal designs. Second, we recruited college students only from one university, but failed to include participants in other universities, who might display different relationship among these variables. Future studies should increase the sample size for a broader study.

5. Conclusions

Psychological resilience is a critical mediating mechanism through which self-concept is associated with negative emotions among college students, and exercise intensity plays a role as a moderating variable in the direct and indirect influence of self-concept on negative emotions.

The current evidence can be used to inform college students to prevent or reduce negative emotions through improving their self-concept, psychological resilience, and exercise intensity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants who participated in this study and Jiali Wang for her help.

Author Contributions

Q.Z.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Funding acquisition. L.M.: Methodology, Formal analysis. L.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—Review & Editing. H.W.: Methodology, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We secured written consent from all participants and obtained approval for the research from the Nantong University Academic Ethics Committee (2020-041).

Informed Consent Statement

We secured written consent from all participants and obtained approval for the research from the Nantong University Academic Ethics Committee.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (No. KYCX21_3134) to Qinfei Zhang.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mark G., Smith A.P. Occupational stress, job characteristics, coping, and the mental health of nurses. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2012;17:505–521. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monteiro S., Marques Pinto A., Roberto M.S. Job demands, coping, and impacts of occupational stress among journalists: A systematic review. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2015;25:751–772. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2015.1114470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tian S., Xu S., Ma Z., Liu Z., Sun G. Mediating Effect of Psychological Resilience on Physical Activity Level and Negative Emotions in College Students: 924. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021;53:305. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000762688.93041.d8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemke H., Probst S., Warneke A., Waltemate L., Winter A., Thiel K., Meinert S., Enneking V., Breuer F., Klug M., et al. The Course of Disease in Major Depressive Disorder Is Associated With Altered Activity of the Limbic System During Negative Emotion Processing. Biol. Psychiatry. Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2022;7:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2021.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkovich I., Eyal O. Teachers’ Big Five personality traits, emotion regulation patterns, and moods: Mediation and prototype analyses. Res. Pap. Educ. 2021;36:332–354. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2019.1677758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seo E.H., Kim S.-G., Kim S.H., Kim J.H., Park J.H., Yoon H.-J. Life satisfaction and happiness associated with depressive symptoms among university students: A cross-sectional study in Korea. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry. 2018;17:6. doi: 10.1186/s12991-018-0223-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reppermund S., Brodaty H., Crawford J., Kochan N., Slavin M., Trollor J., Draper B., Sachdev P. The relationship of current depressive symptoms and past depression with cognitive impairment and instrumental activities of daily living in an elderly population: The Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011;45:1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leary M.R., Tangney J.P. Handbook of Self and Identity. Guilford Press; New York, NY, USA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vispoel W.P. Self-concept in artistic domains: An extension of the Shavelson, Hubner, and Stanton (1976) model. J. Educ. Psychol. 1995;87:134–153. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.87.1.134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen T.H., Hsiao R.C., Liu T.L., Yen C.F. Predicting effects of borderline personality symptoms and self-concept and identity disturbances on internet addiction, depression, and suicidality in college students: A prospective study. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2019;35:508–514. doi: 10.1002/kjm2.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arslan E. Investigation of pre-school childrens’ self-concept in terms of emotion regulation skill, behavior and emotional status. Univ. Murcia Serv. Publ. 2021;37:508–515. doi: 10.6018/analesps.364771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lohbeck A., Hagenauer G., Frenzel A.C. Teachers’ self-concepts and emotions: Conceptualization and relations. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018;70:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edward K.-L. Resilience: A protector from depression. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2005;11:241–243. doi: 10.1177/1078390305281177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid R. Psychological Resilience. Med. Leg. J. 2016;84:172–184. doi: 10.1177/0025817216638781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas L.J., Revell S.H. Resilience in nursing students: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today. 2016;36:457–462. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills J., Woods C., Harrison H., Chamberlain-Salaun J., Spencer B. Retention of early career registered nurses: The influence of self-concept, practice environment and resilience in the first five years post-graduation. J. Res. Nurs. 2017;22:372–385. doi: 10.1177/1744987117709515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J., Li X., Zhao J., An Y. Relations among resilience, emotion regulation strategies and academic self-concept among Chinese migrant children. Curr. Psychol. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02086-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau P.L., Wilkins-Yel K.G., Wong Y.J. Examining the indirect effects of self-concept on work readiness through resilience and career calling. J. Career Dev. 2020;47:551–564. doi: 10.1177/0894845319847288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haktanir A., Watson J.C., Ermis-Demirtas H., Karaman M.A., Freeman P.D., Kumaran A., Streeter A. Resilience, academic self-concept, and college adjustment among first-year students. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2021;23:161–178. doi: 10.1177/1521025118810666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang J.-J., Ji Y., Li Y.-H., Yuan M.-Y., Su P.-Y. Childhood trauma and depression in college students: Mediating and moderating effects of psychological resilience. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2021;65:102824. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou W.K., Tong H., Liang L., Li T.W., Liu H., Ben-Ezra M., Goodwin R., Lee T.M.-C. Probable anxiety and components of psychological resilience amid COVID-19: A population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;282:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge L.K., Hu Z., Wang W., Siu P.M., Wei G.X. Aerobic Exercise Decreases Negative Affect by Modulating Orbitofrontal-Amygdala Connectivity in Adolescents. Life. 2021;11:577. doi: 10.3390/life11060577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He Q., Wu J., Wang X., Luo F., Yan K., Yu W., Mo Z., Jiang X. Exercise intervention can reduce the degree of drug dependence of patients with amphetamines/addiction by improving dopamine level and immunity and reducing negative emotions. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021;13:1779–1788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ligeza T.S., Kałamała P., Tarnawczyk O., Maciejczyk M., Wyczesany M. Frequent physical exercise is associated with better ability to regulate negative emotions in adult women: The electrophysiological evidence. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2019;17:100294. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.100294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan J.S., Liu G., Liang D., Deng K., Wu J., Yan J.H. Special issue—Therapeutic benefits of physical activity for mood: A systematic review on the effects of exercise intensity, duration, and modality. J. Psychol. 2019;153:102–125. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2018.1470487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balchin R., Linde J., Blackhurst D., Rauch H.L., Schönbächler G. Sweating away depression? The impact of intensive exercise on depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;200:218–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox R.H., Thomas T.R., Hinton P.S., Donahue O.M. Effects of acute 60 and 80% VO2max bouts of aerobic exercise on state anxiety of women of different age groups across time. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2004;75:165–175. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2004.10609148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daley A.J., Welch A. The effects of 15 min and 30 min of exercise on affective responses both during and after exercise. J. Sports Sci. 2004;22:621–628. doi: 10.1080/02640410310001655778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ensari I., Sandroff B.M., Motl R.W. Intensity of treadmill walking exercise on acute mood symptoms in persons with multiple sclerosis. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2017;30:15–25. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2016.1146710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer J.D., Koltyn K.F., Stegner A.J., Kim J.S., Cook D.B. Influence of Exercise Intensity for Improving Depressed Mood in Depression: A Dose-Response Study. Behav. Ther. 2016;47:527–537. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider S., Askew C.D., Diehl J., Mierau A., Kleinert J., Abel T., Carnahan H., Strüder H. EEG activity and mood in health orientated runners after different exercise intensities. Physiol. Behav. 2009;96:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buscombe R.M., Inskip H. Affective change as a function of exercise intensity in a group aerobics class. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2013;11:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jesf.2013.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dishman R.K., Thom N.J., Puetz T.W., O’Connor P.J., Clementz B.A. Effects of cycling exercise on vigor, fatigue, and electroencephalographic activity among young adults who report persistent fatigue. Psychophysiology. 2010;47:1066–1074. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woo M., Kim S., Kim J., Petruzzello S.J., Hatfield B.D. Examining the exercise-affect dose-response relationship: Does duration influence frontal EEG asymmetry? Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2009;72:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin B. Revision of Tennessee self - concept scale. China’s Annual Test (Taiwan) 1980;27:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antony M., Bieling P., Cox B., Enns M., Swinson R. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol. Assess. 1998;10:176–181. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang K., Shi H.S., Geng F.L., Zou L.Q., Tan S.P., Wang Y., Neumann D.L., Shum D.H., Chan R.C. Cross-cultural validation of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 in China. Psychol. Assess. 2016;28:e88–e100. doi: 10.1037/pas0000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu Y.-Q. Development and Psychometric Validity of the Resilience Scale for Chinese Adolescents. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2008;40:902–912. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2008.00902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang D. Stress level of college students and its relation with physical exercise. Chin. Ment. Health. 1994;8:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayes A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford Press; New York, NY, USA: 2013. p. xvii-507. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dejonckheere E., Bastian B. Perceiving Social Pressure not to Feel Negative is Linked to a More Negative Self-concept. J. Happiness Stud. 2021;22:667–679. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00246-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Showers C.J., Ditzfeld C.P., Zeigler-Hill V. Self-Concept Structure and the Quality of Self-Knowledge. J. Personal. 2015;83:535–551. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Womble M.N., Labbé E.E., Cochran C.R. Spirituality and personality: Understanding their relationship to health resilience. Psychol. Rep. 2013;112:706–715. doi: 10.2466/02.07.PR0.112.3.706-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cote J. Sociological Perspectives on Identity Formation: The Culture-Identity Link and Identity Capital. J. Adolesc. 1996;19:417–428. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajan-Rankin S. Self-Identity, Embodiment and the Development of Emotional Resilience. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2013;44:2426–2442. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bct083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin J.Y., Steger M., Henry K. Self-concept clarity’s role in meaning in life among American college students: A latent growth approach. Self Identity. 2016;15:206–223. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2015.1111844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tabibnia G. An affective neuroscience model of boosting resilience in adults. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020;115:321–350. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zannas A.S., West A.E. Epigenetics and the regulation of stress vulnerability and resilience. Neuroscience. 2014;264:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sethi M., Asghar M. Study of Self-Esteem of Orphans and Non-Orphans. Peshawar J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2016;1:163–182. doi: 10.32879/pjpbs.2015.1.2.163-182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawabata M., Lee K., Choo H.C., Burns S.F. Breakfast and Exercise Improve Academic and Cognitive Performance in Adolescents. Nutrients. 2021;13:1278. doi: 10.3390/nu13041278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vladimir S., Yu K. Volitional Control in Junior Athletes. Psychology. J. High. Sch. Econ. 2012;9:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paolucci E.M., Loukov D., Bowdish D.M.E., Heisz J.J. Exercise reduces depression and inflammation but intensity matters. Biol. Psychol. 2018;133:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oliveira B.R., Slama F.A., Deslandes A.C., Furtado E.S., Santos T.M. Continuous and high-intensity interval training: Which promotes higher pleasure? PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e79965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hammer T.M., Pedersen S., Pettersen S.A., Rognmo K., Sagelv E.H. Affective Valence and Enjoyment in High-and Moderate-High Intensity Interval Exercise. The Tromsø Exercise Enjoyment Study. Front. Psychol. 2022;13:825738. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.825738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.