Abstract

The gene (dctA) encoding the aerobic C4-dicarboxylate transporter (DctA) of Escherichia coli was previously mapped to the 79-min region of the linkage map. The nucleotide sequence of this region reveals two candidates for the dctA gene: f428 at 79.3 min and the o157a-o424-o328 (or orfQMP) operon at 79.9 min. The f428 gene encodes a homologue of the Sinorhizobium meliloti and Rhizobium leguminosarum H+/C4-dicarboxylate symporter, DctA, whereas the orfQMP operon encodes homologues of the aerobic periplasmic-binding protein- dependent C4-dicarboxylate transport system (DctQ, DctM, and DctP) of Rhodobacter capsulatus. To determine which, if either, of these loci specify the E. coli DctA system, the chromosomal f428 and orfM genes were inactivated by inserting Spr or Apr cassettes, respectively. The resulting f428 mutant was unable to grow aerobically with fumarate or malate as the sole carbon source and grew poorly with succinate. Furthermore, fumarate uptake was abolished in the f428 mutant and succinate transport was ∼10-fold lower than that of the wild type. The growth and fumarate transport deficiencies of the f428 mutant were complemented by transformation with an f428-containing plasmid. No growth defect was found for the orfM mutant. In combination, the above findings confirm that f428 corresponds to the dctA gene and indicate that the orfQMP products play no role in C4-dicarboxylate transport. Regulation studies with a dctA-lacZ (f428-lacZ) transcriptional fusion showed that dctA is subject to cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP)-dependent catabolite repression and ArcA-mediated anaerobic repression and is weakly induced by the DcuS-DcuR system in response to C4-dicarboxylates and citrate. Interestingly, in a dctA mutant, expression of dctA is constitutive with respect to C4-dicarboxylate induction, suggesting that DctA regulates its own synthesis. Northern blot analysis revealed a single, monocistronic dctA transcript and confirmed that dctA is subject to regulation by catabolite repression and CRP. Reverse transcriptase-mediated primer extension indicated a single transcriptional start site centered 81 bp downstream of a strongly predicted CRP-binding site.

Escherichia coli can utilize C4-dicarboxylates as a carbon and energy source under aerobic and anaerobic conditions (9, 50, 56). Anaerobically, the uptake, exchange, and efflux of C4-dicarboxylates (fumarate, malate, maleate, and succinate) and l-aspartate are mediated by the three independent dicarboxylate uptake (Dcu) systems, DcuA, DcuB, and DcuC (9, 12, 13, 50, 56). These Dcu systems appear to be active solely under anaerobic conditions (9).

Aerobically, uptake of C4-dicarboxylates is mediated by a secondary transporter and/or a binding-protein-dependent system, designated Dct (20, 24). The Dct system has an apparent Km of 10 to 20 μM for C4-dicarboxylates and is driven by the electrochemical proton gradient (15), and its activity is induced by succinate and is subject to catabolite repression (20, 27). The corresponding dctA mutants cannot utilize the C4-dicarboxylates malate and fumarate but grow normally on the monocarboxylate lactate (27). Transport across the outer membrane may be mediated by a C4-dicarboxylate-binding protein (Cbt; Kd for C4-dicarboxylates of 30 to 50 μM) and a porin (3, 4, 25–30).

Three genetic loci (cbt at 16.6 min, dctA at 79.3 min, and dctB at 16.4 min) are involved in aerobic C4-dicarboxylate transport (27). The nucleotide sequence of the 76- to 81.5-min region revealed a putative dctA gene (f428) encoding a protein (DctA) most closely resembling the DctA proteins of Sinorhizobium meliloti and Rhizobium leguminosarum (62 to 63% identity) that function as H+/C4-dicarboxylate symporters (51). The DctA proteins are members of a family that includes the Na+/H+ glutamate symporters (GltP/GltT). A role for the putative dctA gene of E. coli in the utilization of C4-dicarboxylates (and the cyclic monocarboxylate orotate) has been suggested by complementation studies with Salmonella typhimurium dctA or outA mutants (2, 51). The coding regions corresponding to the dctB (predicted to encode an inner membrane protein) and cbt (predicted to encode the binding protein) genes have yet to be identified (23).

In addition to the dctA (f428) gene, E. coli contains three apparently cotranscribed genes (o157-o424-o328 or orfQMP) at 79.9 min that encode products 23 to 32% identical to the DctPQM components of the periplasmic binding protein-dependent C4-dicarboxylate transport system of Rhodobacter capsulatus (11, 46, 51). The orfQMP genes are apparently part of a large operon involved in pentose sugar metabolism (11, 42). This suggests that the orfQMP products form a pentose sugar transporter, although, given their similarity to the R. capsulatus DctPQM components, it is also possible that they transport C4-dicarboxylates.

To investigate the potential roles of the dctA and orfQMP genes of E. coli in C4-dicarboxylate transport, the corresponding genes were inactivated and the phenotypes of the resulting mutants were studied. The results showed that the dctA (f428) product is required for aerobic growth on malate and fumarate and mediates the transport of C4-dicarboxylates. Interestingly, dctA mutants were still able to grow aerobically on succinate, indicating the presence of an uncharacterized transporter with specificity for succinate. In contrast, the orfQMP products play no apparent role in C4-dicarboxylate utilization and transport. Transcript mapping and regulatory studies with a dctA-lacZ transcriptional fusion showed that the dctA gene is monocistronic, has a single transcriptional start site, and is activated by cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) in the absence of glucose, repressed by ArcA during anaerobiosis, and weakly activated by the recently identified DcuS-DcuR system (13, 57) in the presence of C4-dicarboxylates. In addition, inactivation of dctA led to constitutive dctA-lacZ expression with respect to C4-dicarboxylates, suggesting that DctA regulates its own synthesis through an interaction with DcuS in a manner similar to that proposed for DctA- and DctB-dependent regulation of dctA in S. meliloti and R. leguminosarum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subcloning the dctA (f428) and orfQMP genes.

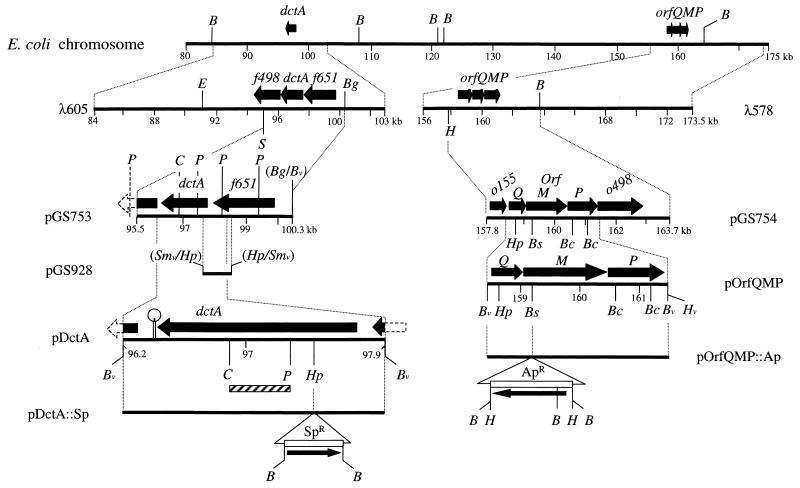

The dctA (f428) and orfQMP genes were subcloned from phages λ605 and λ578, respectively (21), by standard procedures (36). DNA was isolated from the liquid lysates as described by Miller (36). A 4.9-kb BglII-SalI restriction fragment containing dctA was subcloned from λ605 into the BamHI and SalI sites of pSU18, generating plasmid pGS753 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Similarly, a 5.9-kb HindIII-BamHI fragment, containing orfQMP, was isolated from λ578 and inserted into pSU18, generating pGS754 (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Restriction maps of the dctA-orfQMP region of the E. coli chromosome. The inserts cloned in λ578, λ605, pGS753, pGS754, pGS928, pDctA, pOrfQMP, pDctA::Sp and pOrfQMP::Ap are shown along with E. coli DNA (thick black lines) and the Apr and Spr resistance cassettes (open bars). Relevant restriction sites are indicated: B, BamHI; Bc, BclI; Bg, BglII; Bs, BsphI; C, ClaI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; Hp, HpaI; P, PstI; S, SalI; and Sm, SmaI. Restriction sites within vector DNA are denoted by a v, and hybrid restriction sites no longer recognized by the corresponding enzymes are in parentheses. Solid arrows indicate the positions and polarities of relevant structural genes. The hatched bar represents the DNA fragment used as a hybridization probe, and a strongly predicted stem-loop structure is also indicated. Coordinates are from reference 51.

TABLE 1.

Strains, phages, and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| AN387 | Wild type | G. Unden, Mainz, Germany |

| DH5α | Δ(argF-lac)U169 (φ80ΔlacZM15) recA | 41 |

| JC7623 | thr-1 leu-6 proA2 his-4 thi-1 argE3 lacY1 galR2 ara-14 xyl-5 mtl-1 tsx33 rpsL31 supE44 recB21 recC22 sbcB15 | 37 |

| JRG1728 | MC1000 Δ(tyrR-fnr-rac-trg)17 zdd-230::Tn9 | 52 |

| JRG1999 | MC1000 ΔcrpT8 | S. T. Cole, Paris, France |

| JRG2814 | AN387 dcuA::spc dcuB::kan | 50 |

| JRG3351 | MC4100/λRS45(dctA′-lacZYA) | This work |

| JRG3835 | MC4100/λRS45(dcuB′-lacZYA) | 12 |

| JRG3983 | JRG3835 dcuS::mini-Tn10 | 13 |

| JRG3984 | JRG3351 dcuS::mini-Tn10 | 13 |

| JRG4005 | JRG3351 dctA::spc | This work |

| JRG4011 | JRG3351 ΔarcA1 zjj::Tn10 | This work |

| JRG4013 | JRG3351 Δ(tyrR-fnr-rac-trg)17 zdd-230::Tn9 | This work |

| JRG4016 | JRG1999/λRS45(dctA-lacZYA) | This work |

| JRG4017 | MC1000/λRS45(dctA-lacZYA) | This work |

| MC1000 | ΔlacX74 Δ(araABC-leu) | 48 |

| MC4100 | Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL | 48 |

| MDO1 | JC7623 dctA::spc | This work |

| MDO2 | JC7623 orfM::amp | This work |

| MDO800 | AN387 dctA::spc | This work |

| MDO900 | AN387 orfM::amp | This work |

| RH90 | MC4100 rpoS359::Tn10 | R. Hengge-Aronis, Konstanz, Germany |

| RM315 | MC4100 ΔarcA1 zjj::Tn10 | 43 |

| SCA344 | MDO800 orfM::amp | This work |

| SCA345 | JRG3351 rpoS::Tn10 | This work |

| Phages | ||

| P1vir1 | 36 | |

| λRS45 | 49 | |

| λ578 | 21 | |

| λ605 | 21 | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCH21 | pBR325 + 1.65-kb BamHI-HindIII fnr-containing fragment of pGS24; Apr Cmr | 16 |

| pDctA | pSU18 + 1.7-kb dctA fragment | This work |

| pDctA::Sp | pDctA + 1.9-kb spc cassette inserted in dctA; Spr Cmr | This work |

| pGS279 | pBR325 + 2.8-kb BamHI-SalI crp-containing fragment of pBScrp2; Apr Cmr | J. R. Guest, Sheffield, United Kingdom |

| pGS753 | pSU18 + 4.9-kb dctA fragment | This work |

| pGS754 | pSU18 + 5.9-kb orfQMP fragment | This work |

| pGS928 | pRS528 + 0.9-kb dctA′-lacZ | This work |

| pHP45ΩSpc | Apr Spr | 10 |

| pHP45ΩAp | Knr Apr | 10 |

| pOrfQMP | pSU18 + 3.1-kb orfQMP fragment | This work |

| pOrfQMP::Ap | pOrfQMP + 2.6-kb amp cassette inserted in orfM | This work |

| pRB38 | pACYC184 + 4.2-kb arc+ SalI fragment, Cmr | J. R. Guest, Sheffield, United Kingdom |

| pRS528 | Apr | 49 |

| pSU18 | Cmr | 35 |

Inactivation of dctA (f428) and orfQMP.

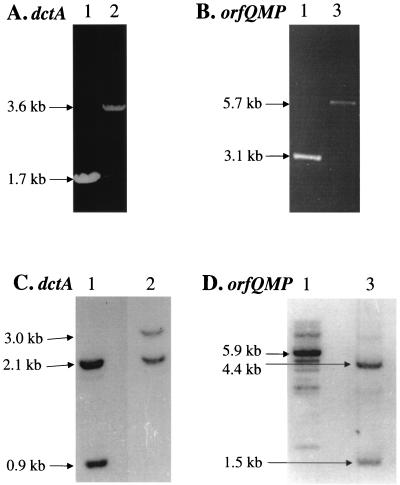

A 1.7-kb fragment containing the putative dctA gene was PCR amplified from pGS753 by using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and primers annealing ∼300 bp upstream and ∼100 bp downstream of the dctA coding region, and the 1.7-kb product was subcloned into the SmaI site of pSU18 to generate pDctA (Fig. 1). The cloned dctA gene was disrupted by inserting a 1.9-kb SmaI fragment containing the spc cassette of pHP45ΩSpc into the HpaI site of pDctA, generating pDctA::Sp (Fig. 1). A similar strategy was used to disrupt the orfQMP operon. A 3.1-kb fragment containing the orfQMP genes was PCR amplified from plasmid pGS754 with Pfu and primers annealing ∼250 bp upstream of orfQ and ∼150 bp downstream of orfP. The 3.1-kb PCR product was subcloned into the SmaI site of pSU18, generating pOrfQMP (Fig. 1), and the operon was disrupted by inserting the amp cassette contained in the 2.6-kb SmaI fragment of pHP45ΩAp into the Klenow-infilled BsphI site of pGS754 to generate pOrfQMP::Ap (Fig. 1). The chromosomal dctA and orfQMP genes were replaced by the disrupted versions in pDctA::Sp and pOrfQMP::Ap by allelic exchange (37). This was achieved by transforming JC7623 (recBC sbcB) with pDctA::Sp or pOrfQMP::Ap and isolating potential dctA::spc and orfM::amp mutants by screening for Spr Cms or Apr Cms colonies. The successful disruption of the dctA and orfM genes was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analyses (Fig. 2). PCR amplification and Southern blotting of the dctA and orfM genes gave the expected band sizes for the parental strain and representative Spr Cms or Apr Cms mutants (MDO1 and MDO2, respectively), indicating that the corresponding dctA or orfM genes had indeed been disrupted with the spc or amp cassette (Fig. 1 and 2). Finally, the dctA::spc and orfM::amp mutations of strains MDO1 and MDO2 were transferred to the wild-type strain, AN387, by phage P1-mediated transductions (36) to produce the mutants MDO800 (AN387, dctA::spc) and MDO900 (AN387, orfM::amp). The identities of the resulting mutants were confirmed by PCR analysis (results not shown).

FIG. 2.

PCR and Southern blot analysis of dctA::spc and orfM::amp mutants. PCR (A and B) and Southern blotting (C and D) were performed, as described in Materials and Methods, with chromosomal DNA from JC7623 (lanes 1), JC7623 dctA::spc (MDO1) (lanes 2), and JC7623 orfM::amp (MDO2) (lanes 3), together with PCR primers or hybridization probes specific for the dctA (A and C) and orfQMP (B and D) regions. The sizes of the PCR products and major hybridizing bands are shown. Analysis of MDO3 gave results similar to those of MDO2 (data not shown).

Southern blot analysis of dctA and orfQMP mutants.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from JC7623 and the Spr Cms and Apr Cms derivatives (34). Southern blotting was performed with 10 μg of chromosomal DNA digested with PstI (dctA analysis) or with HindIII and BamHI (orfQMP analysis), separated by agarose electrophoresis, and blotted onto nylon membranes (41). Hybridizations were carried out at 63°C, and for the dctA analysis the hybridization probe was the digoxigenin-labeled 4.9-kb insert of pGS753, whereas for the orfQMP analysis the hybridization probe was the digoxigenin-labeled 5.9-kb insert of pGS754.

[14C]fumarate and [14C]succinate uptake experiments.

Cultures were grown aerobically to late exponential phase in 500 ml of Luria broth (L broth), and the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (2,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C), resuspended in 100 ml of M9 salts solution (Sigma) at 4°C, centrifuged as before, and finally resuspended in 5 ml of M9 salts solution and kept on ice for up to 6 h before use. Uptake of [14C]fumarate or [14C]succinate (1.8 to 2.2 Gbq mmol−1; NEN) was measured in a stirred Clark-type oxygen electrode assembly at 37°C under aerobic conditions (11, 45, 46). Aliquots (5 μl) of cell suspension were added to 2 ml of M9 salts solution and equilibrated for 1 min before the addition of the radiolabeled substrate to a final concentration of 20 μM [14C]fumarate or [14C]succinate. Samples (0.1 ml) were taken after 20 s and thereafter at 30-s intervals, immediately added to 5 ml of stop buffer (64 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.0], 10 mM fumarate, 0.2 mM sodium fluoroacetate), and filtered rapidly through Whatman GF/F filters. The filters were dried and assayed for radioactivity by scintillation counting. The total protein contents of the cell suspensions were determined by the Lowry et al. assay (32).

Construction of the dctA-lacZ transcriptional fusion.

The 0.9-kb HpaI-HpaI f651′-dctA′ fragment of pGS753 was subcloned into the SmaI site of pRS528 (49) to generate pGS928, carrying a dctA-lacZ transcriptional fusion (Fig. 1). The dctA-lacZ fusion was transferred to phage λRS45 (49) by in vivo homologous recombination as described by Simons et al. (49), and the resulting Lac+ phage, λRS45(dctA′-lacZYA), was used to create a monolysogenic derivative of MC4100, JRG3351 (Δlac λdctA-lacZYA).

To investigate the effects of ArcA, RpoS, and FNR on dctA expression, arcA, rpoS, and fnr deletions were transferred from the respective donor strains, ECL585, RH90, and JRG1728, by P1vir-mediated transduction, to the dctA-lacZ fusion strain, JRG3351, generating strains JRG4011, SCA345, and JRG4013, respectively (Table 1). To study the effects of CRP on dctA expression, a pGS279 (crp+) transformant of strain JRG1999 (Δcrp) was infected with λRS45(dctA′-lacZYA) to generate the monolysogen JRG4016(pGS279), which was subsequently cured of pGS279 by being propagated under nonselective conditions (Table 1).

Growth media and conditions.

Cultures were grown at 37°C either aerobically (50 ml in 250-ml conical flasks at 250 rpm) or anaerobically (10 ml in filled and sealed Bijou bottles) in L broth or M9 minimal salts (Sigma) with various carbon sources.

β-Galactosidase measurements.

β-Galactosidase specific activities (expressed in micromoles of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside [ONPG] per minute per milligram of protein) were determined for samples taken at 0.5- to 1-h intervals from two independent cultures. Each sample was assayed in duplicate, as described previously (12).

Northern hybridization and primer extension analysis.

Total RNA was extracted by a method (12) based upon that described by Aiba et al. (1). The 0.46-kb ClaI-PstI dctA fragment of pDctA (Fig. 1) was used as the hybridization probe. Reverse transcriptase-mediated primer extension analysis was performed (12, 39) with two independent primers for each promoter (see reference 51 for coordinates): P1dctA (5′-2235ATCGCTGTCAGGACCTGAAAGTAAAGGCTT2206-3′) and P2dctA (5′-2211TAGAAATGGCCAAGGAGAATACCAATGGCT2182-3′). Sequence ladders were generated with the T7 Sequenase DNA sequencing kit (Amersham) together with pGS753 as template and the primers described above. A potential CRP site was identified by using the score-matrix searching option of the xnip program (53) and a score matrix derived from 25 experimentally determined CRP-binding sites.

RESULTS

Growth properties of the dctA and orfM mutants.

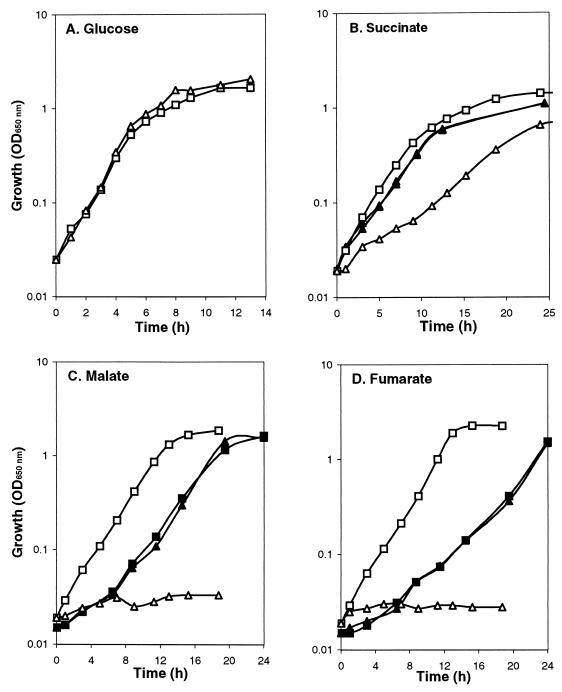

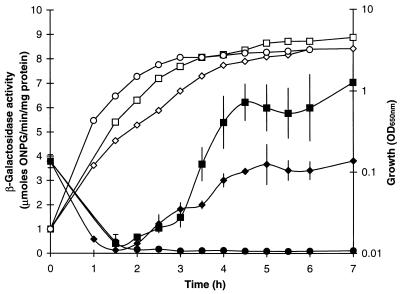

The wild type and dctA mutant grew identically under aerobic conditions in L broth (data not shown) and minimal medium containing 0.4% glucose (Fig. 3A), 0.4% fructose, 40 mM lactate, 40 mM acetate, or 0.4% glycerol (data not shown) as the sole carbon source. However, the dctA mutant (MDO800) failed to grow with malate or fumarate as the sole carbon source and grew more slowly than the wild type with succinate (Fig. 3). The growth difference on succinate was fully complemented by pDctA (Fig. 3B), but the growth defects on fumarate and malate were only partially restored by pDctA (Fig. 3C and D). However, AN387(pDctA) grew at the same rate as MDO800(pDctA) in fumarate and malate minimal medium (Fig. 3C and D), showing that pDctA lowers the fumarate- and malate-dependent growth of the parental strain. No growth defects were detected for the orfM mutant, MDO900, under the same conditions.

FIG. 3.

Effects of the dctA::spc mutation on growth. Cultures were grown aerobically in M9 salts medium containing 0.4% glucose (A), 50 mM succinate (B), 50 mM malate (C), or 50 mM fumarate: AN387 (dctA+) (□), MDO800 (dctA::spc) (▵), AN387(pDctA) (■), and MDO800(pDctA) (▴). OD650 nm, optical density at 650 nm.

The results indicate that dctA (f428) does indeed encode the aerobic C4-dicarboxylate transporter of E. coli whereas orfQMP plays no apparent role in aerobic C4-dicarboxylate transport. They also show that the dctA mutant retains the ability to utilize succinate as a carbon and energy source, albeit at a reduced rate relative to the wild type. This suggests that E. coli possesses a succinate transporter of relatively low activity that enables the dctA mutant to grow on succinate. The possibility that aerobic succinate transport in the dctA mutant is mediated by the OrfQMP system or the anaerobic C4-dicarboxylate transporters, DcuA and DcuB, was excluded by showing that the aerobic growth of the dctA orfM (SCA344), dctA dcuA (MDO1200), and dctA dcuA dcuB (MDO1100) mutants on succinate was identical to that of the dctA mutant (results not shown). Furthermore, it is unlikely that the other anaerobic C4-dicarboxylate transporter, DcuC, corresponds to the putative DctA-independent aerobic succinate transporter, since dcuC expression is strongly repressed aerobically (58). Therefore, it appears that E. coli contains an uncharacterized succinate transporter, designated SucT, distinct from DctA, DcuA, DcuB, DcuC, and the OrfQMP system.

Anaerobic growth of the dctA and orfM mutants in glycerol (0.4%) plus fumarate (50 mM) was unaffected relative to the wild type, and the dctA mutation likewise had no effect on the anaerobic growth of the dcuA and dcuA dcuB mutants in the same medium (results not shown). This suggests that DctA plays a strictly aerobic role in the transport of C4-dicarboxylates and that the orfQMP products are not involved in either aerobic or anaerobic C4-dicarboxylate transport.

Fumarate and succinate uptake properties of the dctA mutant.

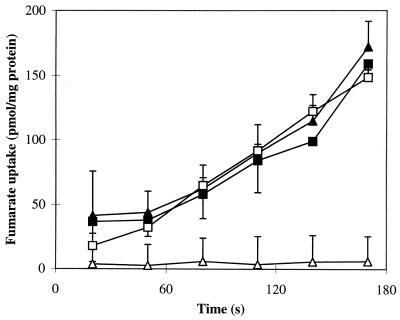

To determine whether the dctA::spc mutation affects transport or some other metabolic function, [14C]fumarate uptake was compared in the wild type and dctA mutant, and in the corresponding pDctA (dctA+) transformants, after aerobic growth to late log phase in L broth (Fig. 4). High levels of fumarate transport activity (∼56 pmol of fumarate/min/mg of protein with 20 μM fumarate) were observed for the wild type (AN387), and although no uptake activity was detected with the dctA mutant, it was fully restored in the pDctA transformant (Fig. 4). This shows that the growth defects of the dctA mutant are due to deficient C4-dicarboxylate transport (Dct) activity and that the failure to transport fumarate is due to inactivation of the dctA gene. The Dct activity of AN387 was inhibited to below detectable levels by a 100-fold excess of unlabeled fumarate but was not affected by 100-fold excess lactate, pyruvate, or acetate (data not shown). This indicates that neither lactate, pyruvate, nor acetate is transported by the DctA system. Dct activity for AN387 in L broth was 19-fold higher during the stationary phase than the early log phase (not shown), probably due to stationary-phase induction of dctA transcription (see below).

FIG. 4.

Effects of the dctA::spc mutation on fumarate transport. Cultures were grown aerobically in L broth, harvested, washed in M9 salts solution, and then used to measure the rate of [2,3-14C]fumarate uptake, in duplicate, as described in Materials and Methods. The strains were AN387 (dctA+) (□), MDO800 (dctA::spc) (▵), AN387(pDctA) (■), and MDO800(pDctA) (▴). Standard deviations are shown.

As anticipated from the growth studies (Fig. 3), the dctA mutant was able to transport succinate, but the rate was ∼10- fold lower than that of the wild type (data not shown). Thus, the poor growth of the dctA mutant on succinate is apparently a consequence of reduced transport capacity.

Environmental factors affecting dctA expression.

To provide a more complete understanding of the role of DctA in C4-dicarboxylic acid transport, factors that regulate dctA expression were examined by using a strain harboring a single-copy dctA-lacZ transcriptional fusion: JRG3351 (MC4100/λRS45[dctA′-lacZYA]). The fusion contains 0.43 kb of the upstream f651 gene, the 0.18-kb f651-dctA intergenic region, and 0.3 kb of the dctA coding region (Fig. 1). The activity of the dctA-lacZ fusion in single copy (see below) indicated that the dctA gene possesses an independent promoter and therefore, contrary to a previous suggestion (51), is not dependent on the upstream f651 gene for transcription.

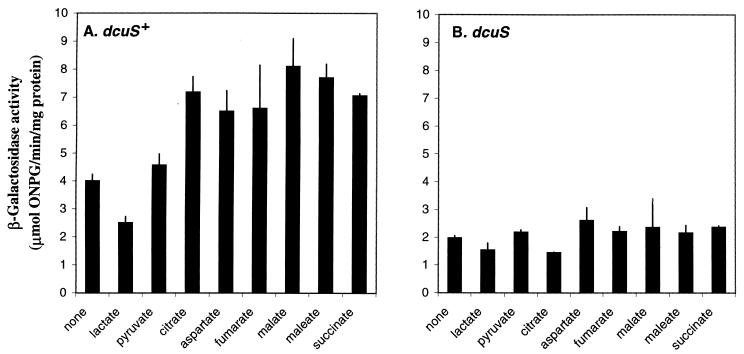

The activity of the dctA-lacZ fusion varied in a growth-phase-dependent manner during aerobic growth in L broth (Fig. 5), increasing up to 19-fold in stationary phase (∼3.8 μmol/min/mg) relative to the early-log-phase activity (∼0.2 μmol/min/mg). This growth-phase-dependent pattern resembles that observed for CRP-regulated genes such as the cst genes, mcc, and glgCAP (22, 31), suggesting that dctA is also regulated by CRP (see below). The addition of glucose lowered the expression of the fusion by up to ∼30-fold to give a relatively constant activity (∼0.13 μmol/min/mg) throughout the growth cycle (Fig. 5). This further supports the view that dctA is subject to CRP-mediated catabolite repression, which is consistent with studies by Kay and Kornberg (20) showing that CRP, cyclic AMP (cAMP), and glucose regulate Dct activity. Interestingly, dctA expression was induced approximately twofold by the presence of succinate (7.3 and 3.8 μmol/min/mg with and without succinate, respectively) (Fig. 5). Similarly, inductions were observed when citrate, aspartate, fumarate, malate, or maleate was added to the L broth, but no dctA-lacZ induction was observed with lactate and pyruvate (Fig. 6A). These data show that dctA is weakly induced by its C4-dicarboxylate transport substrates and by citrate, but not by the monocarboxylates tested. These findings are consistent with recent reports that dctA is induced approximately threefold by succinate and twofold by fumarate (13, 57), and they are compatible with a weak C4-dicarboxylate-dependent activation of dctA by the DcuS-DcuR system (13).

FIG. 5.

Expression of a dctA-lacZ transcriptional fusion during aerobic growth in L broth. The β-galactosidase activities (solid symbols) and culture densities (open symbols) of JRG3351 (dctA-lacZ) are shown after growth at 37°C in L broth (◊ and ⧫), L broth with 50 mM succinate (□ and ■), and L broth with 1% glucose (○ and ●). Error bars represent standard deviations for two cultures, each assayed in duplicate. OD650 nm, optical density at 650 nm.

FIG. 6.

Effects of various carboxylates and the dcuS mutation on dctA-lacZ expression. Cultures of JRG3351 (dcuS+) (A) and JRG3984 (dcuS) (B) were grown aerobically to the postexponential phase in L broth supplemented with carboxylates (50 mM) as indicated. The β-galactosidase activities are shown with standard deviations.

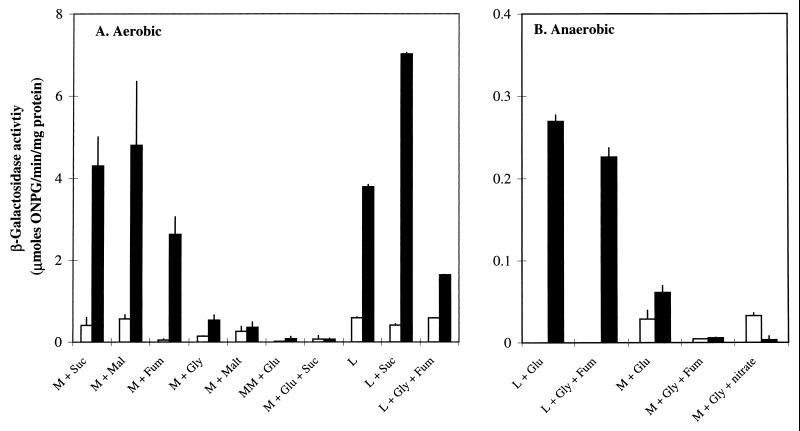

Expression of the dctA-lacZ fusion during aerobic growth in minimal medium varied with the carbon source (Fig. 7A). Expression of dctA was ca. sixfold higher with glycerol than with glucose (∼0.8 and ∼0.13 μmol/min/mg, respectively, in the postexponential phase) as the sole carbon source, presumably due to catabolite repression. However, much higher levels of expression were achieved with C4-dicarboxylate substrates (2.7 to 4.8 μmol/min/mg in the postexponential phase), further indicating that dctA expression is activated by C4-dicarboxylates. The weak dctA expression with glucose was not relieved by succinate, presumably because the catabolite repression effect exerted by glucose is dominant over the activation effect mediated by C4-dicarboxylates (Fig. 7A). This is fully consistent with strong activation of dctA transcription by CRP and weak induction in response to C4-dicarboxylates.

FIG. 7.

Expression of dctA-lacZ during aerobic (A) and anaerobic (B) growth. Growth of JRG3351 took place in L broth or M9 minimal medium with or without 50 mM succinate (Suc), malate (Mal), fumarate (Fum), or nitrate or 0.4% glycerol (Gly) or maltose (Malt), or 0.4% glucose (Glu) in minimal medium (M) and 1% glucose in L broth (L). β-Galactosidase activities were assayed in duplicate with samples taken from duplicate cultures at 0.5- to 1-h intervals over the entire growth phase, but only those corresponding to early-logarithmic (open bars) and postexponential (solid bars) growth are shown. Standard deviations are indicated.

During anaerobic growth, the dctA-lacZ fusion was weakly expressed (0.003 to 0.27 μmol/min/mg) under all conditions used (Fig. 7B). In particular, the activities observed anaerobically in L broth or in minimal medium containing glycerol and fumarate were 7- and 150-fold lower than the corresponding levels observed aerobically (Fig. 7). These findings clearly indicate that dctA transcription is repressed in the absence of oxygen.

Effects of global regulators on dctA-lacZ expression.

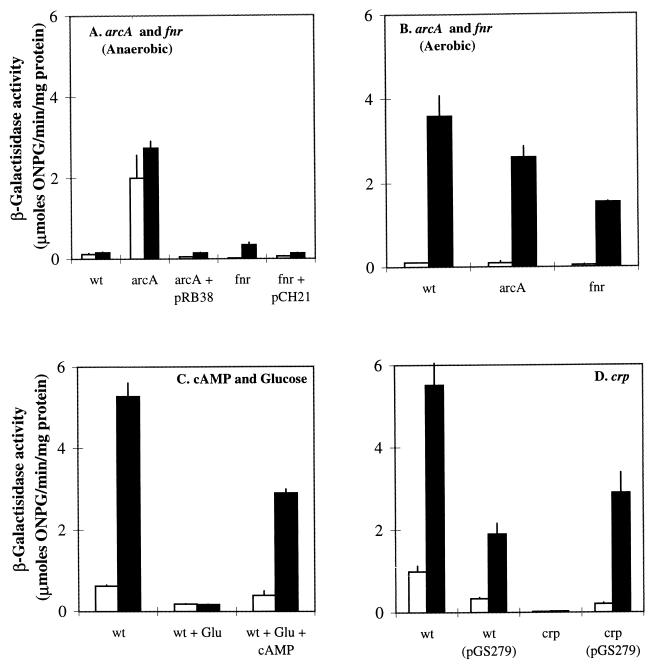

The above studies show that dctA expression is strongly affected by catabolite repression, repressed in the absence of oxygen, induced in the stationary phase, and induced ca. twofold in the presence of citrate and C4-dicarboxylates. The roles of the global transcriptional regulators, ArcA, FNR, CRP, and RpoS, in the regulation of dctA transcription were investigated by studying the appropriate regulatory mutants. The postexponential anaerobic expression of the dctA-lacZ fusion under fumarate respiratory conditions was 18-fold higher in the ΔarcA strain, JRG4011, than in the arcA+ parental strain, JRG3351 (Fig. 8A), but transformation of the ΔarcA strain with the arcA-containing plasmid, pRB38, restored the anaerobic repression of dctA expression, resulting in expression levels similar to those of the wild type (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the Δfnr mutation of JRG4013 increased dctA expression by only twofold. This effect was reversed by supplying the multicopy fnr+ plasmid, pCH21 (Fig. 8A). Similar results were observed with cultures grown under fermentative conditions (L broth plus 0.4% fructose), where postexponential dctA expression was 12- and 2-fold higher in the arcA and fnr mutants (2.4 and 0.4 μmol/min/mg), respectively, than in the wild type (0.2 μmol/min/mg). These results indicate that the anaerobic repression of dctA is mediated primarily by ArcA, with a minor contribution from FNR that is likely to be related to the activation of arcA expression by FNR (6).

FIG. 8.

Effects of ArcA, FNR, cAMP, and CRP on dctA-lacZ expression. Cultures were grown anaerobically (A) or aerobically (B to D) at 37°C in L broth plus 0.4% glycerol and 50 mM fumarate (A), in L broth only (B and D), or in L broth with and without 1% glucose (Glu) and 5 mM cAMP (C). The strains were JRG3351 (wild type [wt]), JRG4011 (arcA), JRG4013 (fnr), and JRG4016 (crp) and the corresponding transformants containing plasmids pRB38 (arcA+), pCH21 (fnr+), and pGS279 (crp+). Note that JRG4017 (the corresponding crp+ control for JRG4016) gave very similar results to those obtained with JRG3351 (data not shown). Other details are as for Fig. 7.

Somewhat surprisingly, the Δfnr mutation caused a 2.4-fold reduction in aerobic dctA expression (Fig. 8B), which suggests a minor aerobic role for FNR in the aerobic induction of dctA expression, as has been observed previously for eight unidentified E. coli gene products (44). There was only a slight (1.4-fold) reduction in dctA expression in the ΔarcA strain (Fig. 8B), indicating that Arc has little effect on dctA expression aerobically.

The ∼30-fold postexponential repression of dctA expression by glucose in L broth observed under aerobic conditions was largely reversed by the addition of cAMP (from 0.17 to 2.9 μmol/min/mg), which provides a strong indication that dctA is activated by the cAMP-CRP complex (Fig. 8C). Furthermore, aerobic dctA expression in L broth was virtually abolished by the Δcrp mutation of JRG4016 (Fig. 8D), resulting in a 275-fold reduction of dctA expression from 5.5 to 0.02 μmol/min/mg. Complementation of the Δcrp mutation by the crp+ plasmid, pGS279, increased dctA expression ∼130-fold to a level similar to that of the corresponding parental transformant, JRG3351 (Fig. 8D). Expression of dctA was unaffected by the rpoS mutation of SCA345, showing that dctA transcription is RpoS independent (data not shown). These observations strongly suggest that the cAMP-CRP complex is a major transcriptional activator for dctA expression and is responsible for the observed stationary-phase induction.

The strong CRP-mediated catabolite repression of dctA expression is in agreement with the prevention of induction of Dct activity by glucose: the presence of glucose in succinate minimal medium caused a ∼50-fold reduction in Dct activity (20), which compares well with the ∼67-fold reduction in aerobic postexponential dctA expression caused by the presence of glucose in succinate minimal medium (Fig. 7A). The observed CRP regulation is also consistent with the inability of mutants lacking phosphotransferase system components to grow on succinate (54) and the reestablishment of Dct activity in cya (adenyl cyclase) mutants by the addition of cAMP to the growth medium (27). In addition, the ca. twofold induction of dctA expression by C4-dicarboxylates matches the two- to threefold maleate-dependent induction of Dct activity in minimal medium containing various carbon sources (20). Therefore, Dct activity and dctA transcription are regulated in parallel in response to catabolite repression and C4-dicarboxylates, indicating that Dct activity is regulated mainly at the level of transcription.

Roles of DcuS-DcuR and DctA in the C4-dicarboxylate-dependent regulation of dctA-lacZ expression.

The possibility that the C4-dicarboxylate-dependent induction of dctA expression is mediated by the recently discovered two-component C4-dicarboxylate-responsive DcuS-DcuR system was tested by using a dcuS mutant, JRG3984. Under aerobic conditions in L broth, the dcuS mutation caused a twofold reduction in postexponential dctA expression and abolished dctA induction by C4-dicarboxylates or citrate (Fig. 6B). These findings are consistent with the recent report that dctA is induced fourfold by C4-dicarboxylates in a DcuS-DcuR-dependent manner (13). The dctA gene could thus be a member of the DcuSR regulon, along with the dcuB-fumB (specifying an anaerobic C4-dicarboxylate transporter and the anaerobic fumarase) and frdABCD (encoding fumarate reductase) operons (13, 57). However, it should be noted that these results contradict those of Zientz et al. (57), who concluded that the C4-dicarboxylate induction of dctA is DcuS-DcuR independent.

The possibility that the DctA protein is involved in regulating its own synthesis either directly or indirectly (via its transport activity) was tested by comparing dctA expression in JRG3351 (dctA-lacZ dctA+) and JRG4005 (dctA-lacZ dctA::spc) during aerobic growth in glycerol (0.4%) minimal medium with and without 50 mM malate, succinate, or maleate (Fig. 9). The dctA mutation resulted in a 2.6-fold increase in dctA expression in the absence of C4-dicarboxylates, suggesting that DctA represses its own synthesis. Interestingly, the C4-dicarboxylates no longer induced dctA-lacZ expression in the dctA mutant. Therefore, the dctA mutation results in the constitutive expression of dctA-lacZ with respect to the presence or absence of C4-dicarboxylates. A similar phenomenon has been reported for the dctA genes of R. leguminosarum and S. meliloti (17, 40, 55). It has been suggested that in these species, in the absence of C4-dicarboxylates DctA interacts with the C4-dicarboxylate-sensing histidine-kinase (DctB) in a way that inhibits signal transduction from DctB to the cognate response regulator (DctD). In the presence of substrate, the DctA-mediated inhibition of DctB activity is thought to be relieved, leading to the induction of dctA by DctD (18, 55). It is possible that an analogous mechanism operates aerobically in E. coli, whereby the C4-dicarboxylate-sensing histidine kinase activity of DcuS is inhibited by DctA in the absence, but not the presence, of C4-dicarboxylates (and presumably citrate).

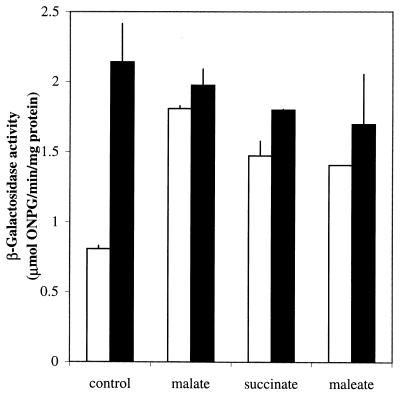

FIG. 9.

Effects of the dctA mutation on dctA-lacZ expression. Cultures of JRG3351 (dctA+) (open bars) or JRG4005 (dctA::spc) (solid bars) were grown aerobically at 37°C in M9 salts medium containing 0.4% glycerol with or without 50 mM malate, succinate, or maleate. Other details are as for Fig. 7.

Citrate induces dcuB expression in a DcuS-DcuR-dependent manner.

Although the DcuS-DcuR system is known to respond to external C4-dicarboxylates (aspartate, fumarate, malate, maleate, succinate, and tartrate) (12, 13, 57), it had not been shown to respond to citrate until tested here (Fig. 6). To determine whether other members of the DcuSR regulon are also induced by citrate in a DcuS-DcuR-dependent fashion, expression of a dcuB-lacZ transcriptional fusion was measured following anaerobic growth to the late log phase (25 h of growth to an optical density at 650 nm of ∼0.4) in minimal medium containing 0.4% glycerol and 50 mM trimethylamine oxide, with and without 50 mM citrate. The expression of dcuB was induced ∼20-fold by citrate in the dcuS+ strain (JRG3835) (0.59 ± 0.05 and 0.032 ± 0.01 μmol of ONPG/min/mg of protein in the presence and absence, respectively, of citrate) but not in the dcuS mutant, JRG3983 (0.009 ± 0.0004 and 0.012 ± 0.002 μmol/min/mg, respectively), and in the presence of citrate, dcuB expression was 66-fold greater in the dcuS+ strain than the dcuS mutant. As expected, these results show that dcuB (like dctA) is induced by citrate in a DcuS-DcuR-dependent manner. This confirms that the DcuS-DcuR system responds to citrate as well as to C4-dicarboxylates.

Northern blot analysis of dctA transcription.

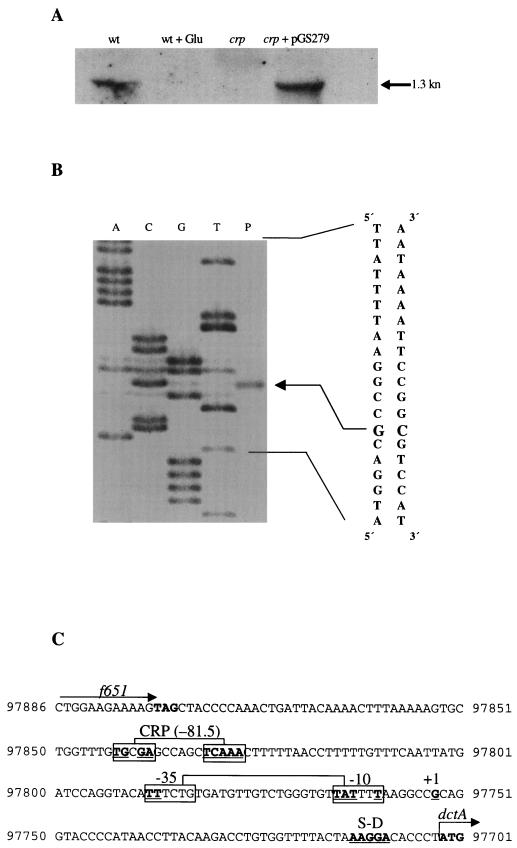

Northern hybridization was performed to determine the size of the dctA transcript and to correlate its abundance with expression of the dctA-lacZ fusion (Fig. 10A). Total RNA was extracted from MC1000 (wild type), JRG1999 (Δcrp), and a pGS279 (crp+) transformant of JRG1999, grown to stationary phase in L broth with and without 0.4% glucose, and then hybridized with a labeled dctA fragment (Fig. 10A). A single dctA-hybridizing (1,300-nucleotide [nt]) transcript was detected for the wild type grown in the absence of glucose (Fig. 10A). The size corresponds to that expected for a monocistronic dctA transcript initiating at the promoter identified in the f651-dctA intergenic region (see below) and terminating at an inverted repeat (bp 96402 to 96372) located 15 bp downstream of the dctA stop codon (bp 96417) (GenBank accession no. U00039). No dctA-hybridizing transcript was detected for the wild type grown with glucose or from the crp mutant grown in the absence of glucose. However, a single major hybridizing band corresponding to the 1,300-nt dctA transcript was observed in the pGS279-complemented crp strain grown in the absence of glucose. Thus, the dctA Northern blot analysis supports the conclusions derived from the studies with the dctA-lacZ fusion that dctA transcription is strongly activated by the cAMP-CRP complex. Also, contrary to an earlier prediction (51) that dctA forms an operon with the upstream f651 gene (encoding a serpin-like protein), dctA appears to be monocistronic (Fig. 1).

FIG. 10.

Analysis of the dctA transcript. (A) Northern blotting. Total RNA was extracted from MC1000 (wild type [wt]), JRG1999 (crp), and JRG1999 transformed with pGS279 (crp+). Strains were grown aerobically in L broth with or without 1% glucose (Glu). Following electrophoresis and capillary transfer, RNA was hybridized with a labeled dctA fragment. The arrow on the right indicates the specifically hybridizing dctA transcripts. The size of the dctA mRNA transcript (in kilonucleotides) is indicated. (B) Determination of the dctA transcriptional start site by reverse transcriptase-mediated primer extension. RNA was isolated from MC1000 grown aerobically in L broth. Lane P indicates the primer extension product with primer P2dctA. Similar results were obtained with primer P1dctA (results not shown). The sequencing ladder (lanes A, C, G, and T) was generated by using primer P2dctA and pGS753 as template. The corresponding nucleotide sequence, its complement, and the transcriptional start site (indicated by an arrow) are shown. (C) Nucleotide sequence of the dctA promoter region. Coordinates are from reference 51. The experimentally determined +1 site is boxed and labeled, as are the deduced −35 and −10 sites and the predicted CRP site. Residues matching the corresponding consensus sequence for the CRP, −35, −10, +1, and Shine-Dalgarno (S-D) sites are in bold and underlined. The positions of the predicted start codon of dctA and termination codon of f651 are in bold.

Transcriptional start site of the dctA gene.

The 5′ end of the dctA transcript was defined by primer extension analysis (Fig. 10B). A single primer extension product corresponding to a start site at G-97752, 51 bp upstream of the anticipated dctA translational start codon, was detected (Fig. 10C). It matches the start site determined for the dctA gene of Salmonella typhimurium (2) and is preceded by appropriately positioned −10 and −35 sites, which are separated by the optimal distance, 17 bp. The −35 site is relatively poor, and this would explain why dctA expression is weak in the absence of cAMP-CRP activation. There is a strongly predicted CRP-binding site at bp −81.5, which is consistent with the strong cAMP-CRP activation of dctA expression (Fig. 10C), and this indicates that dctA is expressed from a class I CRP-dependent promoter (5). Although ArcA binding-site consensus sequences have been proposed (8, 33), they do not allow the accurate prediction of ArcA-binding sites (47). Therefore, it is not possible to locate potential ArcA-binding sites by sequence analysis, although it is presumed that dctA is directly repressed by ArcA.

DISCUSSION

The coidentity of dctA and f428 was previously assumed because of the high degree (∼63%) of amino acid sequence identity between the translation products of the E. coli f428 gene and the rhizobial dctA genes (51), together with the close locations of the E. coli f428 and dctA genes in the respective physical and linkage maps (19, 25, 51). The data presented here confirm that f428 does indeed correspond to the dctA gene encoding the aerobic C4-dicarboxylate transporter of E. coli. The dctA::spc mutant was unable to grow aerobically on fumarate or malate and grew weakly on succinate, which is consistent with the phenotype reported by Kay and Kornberg (19). Anaerobic growth was not affected, nor was aerobic growth on other carbon sources, indicating that dctA is strictly concerned with aerobic C4-dicarboxylate metabolism. The growth defects of the dctA mutant were complemented by a multicopy dctA+ plasmid, confirming that the mutant phenotype is indeed caused by the inactivation of the chromosomal dctA gene. No comparable effects were detected for the orfM::amp mutant, suggesting that the orfQMP genes are not required for C4-dicarboxylate transport. The overexpressed orfP-encoded periplasmic-binding protein has also been shown not to bind C4-dicarboxylates (11a). The orfQMP genes would appear to form part of a nine-gene cluster that is required for l-lyxose utilization (42, 51), and so these genes are likely to be involved in the transport of l-lyxose or some other pentose sugar.

The role of DctA in the aerobic transport of C4-dicarboxylates was confirmed by the aerobic fumarate transport deficiency of the dctA mutant and its complementation by a dctA+ plasmid. Overall, the results show that DctA is probably the sole mediator of fumarate and malate transport under aerobic conditions and that there is at least one undefined transporter (SucT) mediating the aerobic uptake of succinate, albeit at relatively low rates. Possible candidates are the products of the ygjU and o463 genes at 70 and 39 min (respectively), which encode DctA homologues with 27 and 20% sequence identity relative to DctA, or the ygjE (a potential tartrate/succinate antiporter), citT/ybdS (a citrate/succinate antiporter), and ybhI (a potential tricarboxylate transporter) genes (37a, 38).

Previous work has shown that a dctA mutant of Salmonella typhimurium cannot use orotate, a cyclic monocarboxylate, for pyrimidine synthesis, but that the lesion could be complemented by a dctA+ plasmid encoding the E. coli DctA protein, which is 95% identical to the S. typhimurium protein (2). The S. typhimurium dctA mutant was reported to be unable to grow on solid medium containing fumarate and malate, and it grew weakly with succinate, but no transport studies or attempts to complement the nutritional phenotype were made (2), nor was the capacity of the mutant to undergo aerobic growth on other carboxylates and anaerobic growth on C4-dicarboxylates tested. A role for E. coli dctA in C4-dicarboxylate transport has also been implied in a recent study (4a) showing that the inability of an E. coli atp deletion strain to grow on C4-dicarboxylates can be complemented by a dctA+ plasmid.

Expression of a dctA-lacZ transcriptional fusion was found to be subject to strong CRP-mediated catabolite repression and ArcA-mediated anaerobic repression. Despite an earlier report to the contrary (56), the present results clearly support the view that the DcuS-DcuR system is involved in the C4-dicarboxylate-dependent regulation of dctA (13). In a dctA mutant, dctA-lacZ expression was constitutive with respect to the presence or absence of C4-dicarboxylates, indicating a role for DctA in regulating its own synthesis. By analogy to the mechanism proposed for rhizobial dctA autoregulation (17, 18, 40, 55), it is suggested that in aerobically grown E. coli in the absence of exogenous C4-dicarboxylates, DcuS is inhibited by inactive (nontransporting) DctA. Conversely, in the presence of C4-dicarboxylates, DctA would be active (transporting) and the inhibition of DcuS would be relieved, thus allowing signal transduction from DcuR to DcuS and the consequent induction of dctA. Such a mechanism implies that DcuS activity is dictated by the status of DctA. However, anaerobically, DcuS appears to directly sense external C4-dicarboxylates in way that is independent of DctA or the DcuA, DcuB, and DcuC proteins (13, 57), suggesting that DcuS has two modes of operation, one that acts anaerobically and one that acts aerobically. Switching between the anaerobic and aerobic modes could be mediated by the central PAS domain of DcuS. The proposed redox-sensing role of the PAS domain would be consistent with this suggestion (13).

Previous work had shown that the DcuS-DcuR system is responsive to external C4-dicarboxylates, namely, aspartate, fumarate, malate, maleate, succinate, and tartrate (13, 57). In this study, citrate was also found to be a coeffector for the DcuS-DcuR system, indicating that DcuS has broader ligand specificity than was previously realized. It is likely that the induction of the DcuSR regulon by citrate is physiologically significant, since, although most E. coli strains cannot utilize citrate aerobically, under anaerobic conditions citrate can be converted to fumarate for respiratory purposes (38). The anaerobic utilization of citrate would require the expression of the fumarate reductase operon, frdABCD, and the anaerobic fumarase gene of the dcuB-fumB operon. Appropriately, these operons are members of the DcuSR regulon (13, 57) and would therefore be induced by external citrate.

The pattern of dctA regulation is largely consistent with the role of its product in the aerobic uptake of C4-dicarboxylates. The strong CRP activation of dctA ensures that external C4-dicarboxylates are taken up for catabolic purposes only in the absence of “more preferable” carbon and energy sources, such as glucose. The anaerobic repression of dctA by ArcA limits the function of DctA to aerobic conditions. This is desirable since DctA is thought to be a proton symporter and would therefore consume energy, whereas the anaerobic C4-dicarboxylate transporters can act in substrate-product exchange (antiport) mode and would therefore be non-energy consuming, a property that is likely to be important under the relatively low-energy-yielding conditions of anaerobic respiration. The relatively weak induction of dctA expression by C4-dicarboxylates (and citrate) is unlikely to have any major impact on the C4-dicarboxylate metabolism. Interestingly, a dcuS mutant exhibits the same growth defects as the dctA mutant, namely, no growth on fumarate and malate, and weak growth on succinate (13). This suggests that the dcuS mutant is devoid of Dct activity, which in turn suggests that DcuS (or DcuR, since the dcuS mutation is likely to have a polar effect on dcuR) could have a direct effect on DctA transport activity. This possibility is supported by the observation that the dcuS mutant totally lacks Dct activity (7a), although dctA transcription is only halved. The physiological purpose of such a regulatory mechanism is unclear but could be related to the need to ensure that DctA does not mediate net export of C4-dicarboxylates, which could otherwise occur when external C4-dicarboxylate concentrations are low.

The regulatory features of the dctA gene are reminiscent of those of the genes encoding the aerobic CAC (citric acid cycle) enzymes. Like dctA, CAC enzymes are regulated at the level of transcription by CRP-mediated catabolite repression and by the oxygen/redox-responsive, two-component ArcBA system (7). This mode of regulation ensures that CAC activity is relatively low both anaerobically, when the ability of the cycle to supply energy is restricted, and aerobically during growth on glycolytic substrates (such as glucose), when the full cycle is unnecessary because sufficient energy can be derived through glycolysis. Since the role of DctA is to deliver external C4-dicarboxylates for consumption via the aerobically operating CAC, it is physiologically appropriate that dctA regulation should largely match that of the aerobic CAC enzymes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul Bond and Peter Cotterell for technical assistance.

We thank the BBSRC for awarding a Special Studentship (S.J.D.), a Project Grant (S.C.A. and J.R.G.), and an Advanced Fellowship (S.C.A.). We also thank the Iranian government for providing a postgraduate research scholarship (D.O.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba H, Adkya S, de Crombrugghe B. Evidence for a functional gal promoter in intact Escherichia coli cells. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:11905–11910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker K E, Ditullio K P, Neuhard J, Kelln R A. Utilization of orotate as a pyrimidine source by Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli requires the dicarboxylate transport protein encoded by dctA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7099–7105. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7099-7105.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bewick M A, Lo T C Y. Dicarboxylic acid transport in Escherichia coli K12: involvement of a binding protein in the translocation of dicarboxylic acids across the outer membrane of the cell envelope. Can J Biochem. 1979;57:653–661. doi: 10.1139/o79-082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bewick M A, Lo T C Y. Localization of the dicarboxylate binding protein in the cell envelope of Escherichia coli K12. Can J Biochem. 1980;58:885–897. doi: 10.1139/o80-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Boogerd F C, Boe L, Michelsen O, Jensen P R. atp mutants of Escherichia coli fail to grow on succinate due to a transport deficiency. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5855–5859. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5855-5859.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busby S, Ebright R H. Transcription activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2771641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compan I, Touati D. Anaerobic activation of arcA transcription in Escherichia coli: roles of Fnr and ArcA. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:955–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cronan J E, LaPorte D. Tricarboxylic acid cycle and glyoxylate bypass. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 206–216. [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Davies, S., S. C. Andrews, and D. J. Kelly. Unpublished data.

- 8.Drapal N, Sawers G. Purification of ArcA and analysis of its specific interaction with the pfl promoter-regulatory region. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:597–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel P, Kramer R, Unden G. Anaerobic fumarate transport in Escherichia coli by an fnr-dependent dicarboxylate uptake system which is different from aerobic dicarboxylate uptake. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5533–5539. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5533-5539.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fellay R, Frey J, Krisch H. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria—a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1987;52:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forward J A, Behrendt M C, Wyborn N R, Cross R, Kelly D J. TRAP transporters: a new family of periplasmic solute transport systems encoded by the dctQMP genes of Rhodobacter capsulatus and by homologs in diverse gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5482–5493. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5482-5493.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Gibson, M., S. C. Andrews, and D. J. Kelly. Unpublished results.

- 12.Golby P, Kelly D J, Guest J R, Andrews S C. Transcriptional regulation and organization of the dcuA and dcuB genes, encoding homologous anaerobic C4-dicarboxylate transporters in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6586–6596. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6586-6596.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golby P, Davies S, Kelly D J, Guest J R, Andrews S. Identification and characterization of a two-component sensor-kinase and response-regulator system (DcuS-DcuR) controlling gene expression in response to C4-dicarboxylates in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1238–1248. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1238-1248.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guest J R, Green J, Irvine A S, Spiro S. The FNR modulon and FNR-regulated gene expression. In: Lin E C C, Lynch A S, editors. Regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Washington, D.C: Landes Co. and Chapman & Hall; 1996. pp. 317–342. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutowski S J, Rosenberg H. Succinate uptake and related proton movements in Escherichia coli K12. Biochem J. 1975;152:647–654. doi: 10.1042/bj1520647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamison D J, Higgins C F. Anaerobic and leucine-dependent expression of a peptide transport gene in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:131–136. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.1.131-136.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jording D, Sharma P K, Schmidt R, Engelke T, Uhde C, Pühler A. Regulatory aspects of the C4-dicarboxylate transport in Rhizobium meliloti—transcriptional activation and dependence on effective symbiosis. J Plant Physiol. 1992;141:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jording D, Uhde C, Schmidt R, Pühler A. The C4-dicarboxylate transport-system of Rhizobium meliloti and its role in nitrogen-fixation during symbiosis with alfalfa (Medicago sativa) Experienta. 1994;50:874–883. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kay W W, Kornberg H L. Genetic control of the uptake of C4 dicarboxylic acids by Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1969;3:93–96. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(69)80105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kay W W, Kornberg H L. The uptake of C4 dicarboxylic acids by Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1971;18:274–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1971.tb01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohara Y, Akiyama K, Isono K. The physical map of the whole E. coli genome. Cell. 1987;50:495–508. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolter R, Siegele D A, Tormo A. The stationary phase of the bacterial life cycle. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:855–874. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.004231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin E C C. Dissimilatory pathways for sugars, polyols, and carboxylates. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 307–342. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo T C Y. The molecular mechanism of dicarboxylic acid transport in Escherichia coli K12. J Supramol Struct. 1977;7:463–480. doi: 10.1002/jss.400070316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lo T C Y, Bewick M A. The molecular mechanism of dicarboxylic acid transport in Escherichia coli K12. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:7826–7831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo T C Y, Bewick M A. Use of a nonpenetrating substrate analogue to study the molecular mechanism of the outer membrane dicarboxylic acid transport in Escherichia coli K12. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:5511–5517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo T C Y, Rayman K, Sanwal B D. Transport of succinate in Escherichia coli K12. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:6323–6331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo T C Y, Sanwal B D. Isolation of the soluble substrate recognition component of the dicarboxylate transport system of Escherichia coli K12. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:1600–1602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo T C Y, Sanwal B D. Genetic analysis of mutants of Escherichia coli K12 defective in dicarboxylate transport. Mol Gen Genet. 1975;140:303–307. doi: 10.1007/BF00267321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo T C Y, Sanwal B D. Membrane bound substrate recognition components of the dicarboxylate transport system of Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;63:278–285. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(75)80040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loewen P C, Hengge-Aronis R. The role of the sigma factor ςS (KatF) in bacterial global regulation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:53–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynch A S, Lin E C C. Transcriptional control mediated by the ArcA two-component response regulator protein of Escherichia coli: characterization of DNA binding at target promoters. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6238–6249. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6238-6249.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. Methods Enzymol. 1964;6:726–739. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez E, Bartolomé B, De La Cruz F. pACYC184-derived cloning vectors containing the multiple cloning site and lacZα reporter gene of pUC8/9 and pUC18/19 plasmids. Gene. 1988;68:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for E. coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oden K L, DeVeaux L C, Vibat C R T, Cronan J E, Jr, Gennis R B. Genomic replacement in Escherichia coli K-12 using covalently closed circular plasmid DNA. Gene. 1990;96:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90337-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37a.Paulsen, Ian T. January 1999, posting date. Sequences. [Online.] http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/∼ipaulsen/transport/ecoli.html. [8 February 1999, last date accessed.]

- 38.Pos K M, Dimroth P, Bott M. The Escherichia coli citrate carrier CitT: a member of a novel eubacterial transporter family relaed to the 2-oxoglutarate/malate translocator from spinach chloroplasts. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4160–4165. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4160-4165.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quail M A, Haydon D J, Guest J R. The pdhR-aceEF-lpd operon of Escherichia coli expresses the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:95–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ronson C W, Ashwood P M. Genes involved in the carbon metabolism of bacteroids. In: Evans H J, Bottomley P J, Newton W E, editors. Nitrogen fixation research progress. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanchez J C, Gimenez R, Schneider A, Fessner W, Baldoma L, Aguilar J, Badia J. Activation of a cryptic gene encoding a kinase for l-xylose opens a new pathway for the utilisation of l-lyxose by Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29665–29669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sawers G, Suppmann B. Anaerobic induction of pyruvate formate-lyase gene expression is mediated by the ArcA and FNR proteins. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3474–3478. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3474-3478.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sawers R G, Zeheleih E, Böck A. Two-dimensional gel electrophoretic analysis of Escherichia coli proteins: influence of various anaerobic growth conditions and the fnr gene product on cellular protein composition. Arch Microbiol. 1988;149:240–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00422011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaw J G, Kelly D J. Binding-protein dependent transport of C4-dicarboxylates in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Arch Microbiol. 1991;155:466–472. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaw J G, Hamblin M J, Kelly D J. Purification, characterisation and nucleotide sequence of the periplasmic C4-dicarboxylate binding protein (DctP) from Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:3055–306291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen J, Gunsalus R P. Role of multiple ArcA recognition sites in anaerobic regulation of succinate dehydrogenase (sdhCDAB) gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:223–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5561923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silhavy T J, Barman M L, Enquist L W. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Six S, Andrews S C, Unden G, Guest J R. Escherichia coli possesses two homologous anaerobic C4-dicarboxylate membrane transporters (DcuA and DcuB) distinct from the aerobic dicarboxylate transport system (Dct) J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6470–6478. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6470-6478.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sofia H J, Burland V, Daniels D L, Plunkett III G, Blattner F R. Analysis of the Escherichia coli genome. V. DNA sequence of the region from 76.0 to 81.5 minutes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2576–2586. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.13.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spiro S, Guest J R. Inactivation of the FNR protein of Escherichia coli by targeted mutagenesis in the N-terminal region. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:701–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Staden R. The Staden sequence-analysis package. Mol Biotechnol. 1996;5:233–241. doi: 10.1007/BF02900361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang R J, Morse M L. Carbohydrate accumulation and metabolism in Escherichia coli. I. Description of pleiotropic mutants. J Mol Biol. 1968;32:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yarosh O K, Charles T C, Finan T M. Analysis of C4-dicarboxylate transport genes in Rhizobium meliloti. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:813–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zientz E, Six S, Unden G. Identification of a third secondary carrier (DcuC) for anaerobic C4-dicarboxylate transport in Escherichia coli: roles of the three Dcu carriers in uptake and exchange. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7241–7247. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7241-7247.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zientz E, Bongaerts J, Unden G. Fumarate regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli by the DcuSR (dcuSR genes) two-component regulatory system. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5421–5425. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5421-5425.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zientz E, Janausch I G, Six S, Unden G. Functioning of DcuC as the C4-dicarboxylate carrier during glucose fermentation of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3716–3720. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3716-3720.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]