Abstract

Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E is a solvent-resistant strain that is able to grow in the presence of high concentrations of toluene. We have cloned and sequenced the cti gene of this strain, which encodes the cis/trans isomerase, termed Cti, that catalyzes the cis-trans isomerization of esterified fatty acids in phospholipids, mainly cis-oleic acid (C16:1,9) and cis-vaccenic acid (C18:1,11), in response to solvents. To determine the importance of this cis/trans isomerase for solvent resistance a Cti-null mutant was generated and characterized. This mutant showed a longer lag phase when grown with toluene in the vapor phase; however, after the lag phase the growth rate of the mutant strain was similar to that of the wild type. The mutant also showed a significantly lower survival rate when shocked with 0.08% (vol/vol) toluene. In contrast to the wild-type strain, which grew in liquid culture medium at temperatures up to 38.5°C, the Cti-null mutant strain grew significantly slower at temperatures above 37°C. An in-frame fusion of the Cti protein with the periplasmic alkaline phosphatase suggests that this constitutively expressed enzyme is located in the periplasm. Primer extension studies confirmed the constitutive expression of Cti. Southern blot analysis of total DNA from various pseudomonads showed that the cti gene is present in all the tested P. putida strains, including non-solvent-resistant ones, and in some other Pseudomonas species.

Organic solvents such as toluene, xylene, or styrene are known to damage the bacterial cell membrane and thus to inhibit growth. They bind to and penetrate the lipid bilayer and impair vital membrane functions, leading to loss of ions and metabolites, to dissipation of the pH gradient and electrical potential, and to inhibition of membrane protein functions. The toxicity of the solvent depends on the logarithm of its partition coefficient in a mixture of octanol and water (log Pow) (37). During the last decade, numerous bacteria belonging mainly to the genus Pseudomonas, with high resistance to organic solvents, have been isolated (6, 18, 30, 32, 40). To overcome the damage caused by these solvents, several adaptive mechanisms which readjust membrane fluidity have been suggested. Among these mechanisms are solvent efflux pumps (22, 31) and changes in lipopolysaccharide and phospholipid composition (8, 30, 33, 40). The alteration in phospholipid composition includes modifications in the phospholipid headgroup as well as changes in esterified fatty acid composition. There are two major mechanisms involving esterified fatty acids: a shift in the unsaturated/saturated fatty acid ratio, and cis-trans isomerization. The cis-trans modification is considered a short-term response (21) which takes place within 1 min after solvent exposure, whereas changes in the degree of saturation and phospholipid headgroups are long-term responses which are detected after 15 to 20 min. Additionally, an increase in the total amount of phospholipids was found in response to solvent exposure (30).

cis fatty acids are present in most bacteria, whereas the trans isomers are less widespread. Further details about trans fatty acids in bacteria are given in the review by Keweloh and Heipieper (21). The cis-trans isomerization triggered by solvent exposure, which occurs without shifts in the position of the double bond of the C16:1,9 and C18:1,11 fatty acids, was shown to be a postsynthetic enzyme modification in Pseudomonas putida P8 (8). The cis-trans isomerase (Cti) in P. putida P8 has recently been cloned and sequenced (accession no. AJ000978 [15]).

We studied the influence of cis-trans isomerization on toluene resistance in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E (31–33), a strain which can grow in the presence of 90% (vol/vol) toluene and use toluene as the sole source of carbon and energy. Toluene causes an increase in membrane fluidity which is counteracted by an elevated level of trans fatty acids and an increase in the content of cardiolipin as the phospholipid headgroup (33). Both changes decrease membrane fluidity. The cis/trans ratio decreases from 7.5 to 1 when cells are grown in the presence of 1% (vol/vol) toluene in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. In a time course experiment, the level of trans fatty acids increased immediately after exposure to toluene, at the expense of the cis fatty acids. The relative level of cardiolipin was twofold higher in cells growing in the presence of toluene than in cells growing in its absence (33). Toluene efflux pumps were recently identified as playing a major role in toluene resistance (31), whereas the absence or presence of the metabolic route for toluene degradation had no influence on solvent resistance in strain DOT-T1E (26).

We now report the cloning, sequencing, and expression of the cis/trans isomerase, Cti, in P. putida DOT-T1E. To evaluate the role of this isomerase in solvent tolerance, a Cti-null mutant of strain DOT-T1E was generated and physiologically characterized. We found that the mutant was more sensitive than the parent strain to sudden solvent shock and exhibited delayed growth when exposed to nonlethal concentrations of toluene or high temperatures. We also found that the cti gene was expressed constitutively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, culture media, and growth conditions.

P. putida DOT-T1E (Table 1) (32), which is rifampin resistant, was routinely grown in batch culture at 30°C in M9 mineral salt medium supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose or toluene in the vapor phase. The sequence of the gene encoding the 16S rRNA of the P. putida strains (Table 2) showed an identity of more than 99.3% (17). Escherichia coli DH5α was used as a host for most of the cloning experiments. The plasmids used in this study were pUC18Not, which encodes ampicillin resistance (14); pHP45Ω-Km, which encodes kanamycin resistance (10); and pJB3Tc19, which encodes both tetracycline and ampicillin resistance (2). E. coli CC118λPIR was used as the host for the suicide vector pKNG101 (20); this plasmid carries a streptomycin resistance determinant and bears the sacB gene, encoding levansucrase. E. coli HB101(pRK600) was used as a helper strain in triparental matings (14). All E. coli strains were routinely grown in LB medium at 37°C. Other Pseudomonas strains, used for DNA preparations in Southern blots, were grown on LB medium at 30°C and are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Fatty acid composition of the wild-type P. putida DOT-T1E and derivative strainsa

| Fatty acid | Amt of fatty acid (% of total fatty acids) in strain:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| DOT-T1E (wild type) | DOT-T1Ecti0 (mutant) | DOT-T1Ecti0C (complemented) | |

| C16:0 | 38 | 38 | 35 |

| C16:1,9 cis | 10 | 36 | 14 |

| C16:1,9 trans | 21 | 0 | 21 |

| C17:cyclopropane | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| C18:0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| C18:1,11 cis | 14 | 22 | 16 |

| C18:1,11 trans | 9 | 0 | 7 |

Bacteria were grown in minimal medium plus toluene in the vapor phase until the late exponential growth phase.

TABLE 2.

Hybridization of total DNA digested with BglII or SalI of different strains with the cti probe

| Strain | Sizes (kb) of fragmentsa of DNA digested with:

|

Source or reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BglII | SalI | ||

| P. putida DOT-T1Eb | 4.5 | 3.3, 1 | 32 |

| P. putida P8 | 4.5 | NDc | 15 |

| P. putida 2440 | 4.5 | 3.3, 1 | 14 |

| P. putida MTB6b | 4.5 | 3.3, 1 | 17 |

| P. putida MTB5 | 4.5 | 3.3, 1 | 17 |

| P. putida SMO116 | 4.5 | 3.3, 1 | 17 |

| P. putida F1 | 4.5 | 3.3, 1 | 11 |

| P. putida JLR11 | 4.5 | 3.3, 1 | 9 |

| P. fluorescens EEZ20 | 4.2wc | 3.3, 1.5w | 34 |

| P. stutzeri EEZ29 | 3.2 | 1w | 34 |

| P. oleovorans | 7.2 | 1.8, 3.7 | 5 |

| P. mendocina KR1 | 8w | 3.9 | 41 |

| P. syringae pv. syringae EEZ30 | ND | 5.0w | 34 |

| Ralstonia solanacearum EEZ24 | NSc | NS | 34 |

| Burkholderia cepacia CECT322 | NS | NS | 34 |

| Comamonas acidovorans EEZ23 | NS | NS | 34 |

| Brevundimonas diminuta CECT313 | NS | NS | 7 |

| Ralstonia pickettii CECT330 | NS | NS | 7 |

Signals obtained in the Southern blots.

This strain grows in the presence of 1% (vol/vol) toluene in LB medium.

ND, not determined; w, weak band in Southern blot; NS, no signal detected in Southern blot.

Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 50 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; rifampin, 20 μg/ml; streptomycin, 100 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 25 μg/ml.

Recombinant DNA techniques and analysis.

Total DNA preparations, digestion of DNA with restriction enzymes, and agarose gel electrophoresis were done by standard methods (36). Plasmid DNA was isolated on Miniprep spin columns (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA was extracted from agarose gels with the QIAexII gel extraction kit, and PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Competent E. coli cells were prepared by the method of Sambrook et al. (36). DNA for Southern blots was blotted onto positively charged nylon membranes. Fragments of random primed DNA, labeled with digoxigenin (DIG)-dUTP, were used as probes for Southern blots. DNA was sequenced by the automated dideoxy sequencing termination method with T7 phage DNA polymerase.

Triparental matings involving an E. coli donor strain carrying the plasmid to be transferred, E. coli HB101(pRK600) as the helper strain, and benzoate-utilizing P. putida DOT-T1E as the recipient strain were done as described previously (14). P. putida DOT-T1E transconjugants were rescued on M9 minimal medium supplemented with benzoate (10 mM) and appropriate antibiotics.

RNA preparation and primer extension.

RNA was isolated by the method of Marqués et al. (25). We used a single-stranded DNA primer, 5′-ACGCACTTCTCGGTGAAGATCGG-3′, complementary to cti mRNA for primer extension. The primer was labeled at the 5′ end with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. About 105 cpm of the 5′-end-labeled primer was hybridized to 0.2 μg of total RNA, and primer extensions were carried out with avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase as described previously (25). The products of the reverse transcription reaction were separated in a urea-polyacrylamide sequencing gel and visualized by audioradiography.

PCRs.

The standard PCR mixture (25 μl) contained 10 ng of DNA, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 50 pmol of each primer, 2 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide, and 0.25 U of Taq polymerase (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) in the buffer supplied by the manufacturer. The PCR conditions were as follows: 4 min at 95°C, and then 35 cycles of 60°C for 45 s, 72°C for 30 to 180 s, and 94°C for 4 s, followed by a final 5-min step at 72°C.

Alkaline phosphatase assay.

For alkaline phosphatase measurements (39), whole cells of strain DOT-T1E harboring plasmid pJBctipho (which carries a cti::phoA gene fusion in the wide-host-range pJB14 plasmid [see below]) were harvested by centrifugation, washed once with APase buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 1 mM ZnCl2, 1 mM MgCl2), and resuspended in a 1 ml of APase buffer containing 2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. The reaction was started by adding 10 mM 4-nitrophenyl phosphate at 37°C and was stopped after 5 min of incubation at 37°C with 200 μl of 1 M NaOH. The sample was centrifuged for 10 min in a microcentrifuge at 12,000 × g. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 405 nm and compared with a standard curve for 4-nitrophenol.

Analysis of phospholipids.

Phospholipids were extracted by the method of Bligh and Dyer (3). To measure fatty acids, phospholipids were trans esterified by dissolving 3 to 10 mg of fatty acids in 350 μl of hexane. Then 40 μl of 2 M KOH dissolved in methanol was added and mixed vigorously. After the addition of 2 ml of hexane, the upper (hexane) phase was removed and, within 1 h, methyl ester derivatives of fatty acids were identified by mass spectrometry after gas chromatographic separation as described previously (33).

Computer analysis.

Nucleic acid and protein sequences were analyzed by the programs DNA Strider, Amplify, and Align.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence of the cis/trans isomerase gene and the flanking region in strain P. putida DOT-T1E was submitted to the EMBL data bank under accession no. AF110738. Preliminary sequence data for P. aeruginosa and Vibrio cholerae was obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research Website (38a).

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the cti gene from P. putida DOT-T1E including the upstream and downstream region.

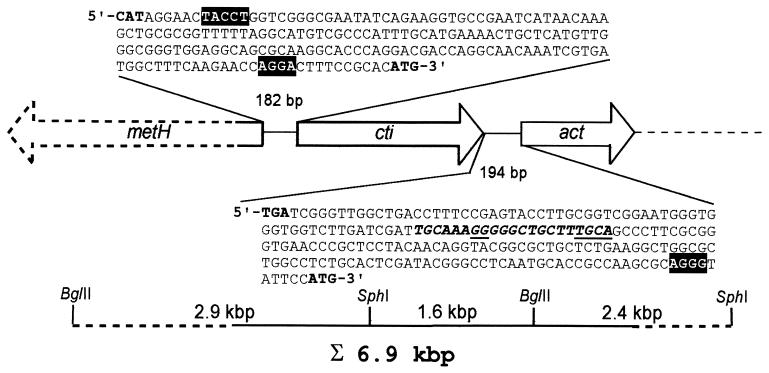

Primers (5′-GCCCGGCTATTTCCTACA-3′ and 5′-AGGCGCAGGAAGTTGAC-3′) deduced from the published sequences of the cis-trans isomerase-encoding gene cti, of P. putida P8 (15) were used to generate a 1,500-bp DIG-labeled DNA probe by PCR with total DNA prepared from P. putida DOT-T1E as a template source. This labeled probe was hybridized against total DNA of strain DOT-T1E digested with BglII. This revealed a single hybridization band in the 4.5-kb region (Table 2). Fragments in the 4.5-kb region were recovered from agarose gels and were ligated into BamHI-digested pUC18Not. Clones were successfully screened with the DIG-labeled cti probe, and a single clone with a 4.5-kbp insert was identified. This 4.5-kbp fragment encoded the entire cis-trans isomerase (Fig. 1). The cti gene of P. putida DOT-T1 had a coding capacity of 766 amino acids, yielding a calculated molecular weight of 86,822. A putative hydrophobic signal sequence of the first 22 amino acids was identified, which suggests that this protein is located in the membrane, as observed for Cti of P. putida P8. A hydrophobicity plot (16) for Cti showed that the rest of the protein consists mainly of hydrophilic amino acids. Upstream of cti of P. putida DOT-T1E we located a putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence (AGGA). Preliminary primer extension experiments (results not shown) gave multiple signals for the putative transcriptional start point, and therefore it could not be determined. A putative transcription stop signal (stem loop) was found downstream (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Map of the cti locus in P. putida DOT-T1E. The two clones BglII and SphI, used for sequencing, are shown (dotted lines indicate unsequenced regions). The orientation and location of the genes encoding methionine synthetase (metH; 3.7 kbp, estimated size from comparison with E. coli metH), cis-trans isomerase (cti; 2.3 kbp), and acetyltransferase (act; 1 kbp) are indicated by arrows. The intergenic regions of metH and cti and of cti and act have been enlarged, and the Shine-Dalgarno sequences (white letters on black background), start and stop codons (boldface), putative promoter sequences (bold italics and underlined), and putative stop signal (boldface italics) are indicated.

Upstream of the cti gene we found an incomplete open reading frame (ORF) (328 bp was sequenced) in the opposite orientation, which encoded a methionine synthetase (Fig. 1). The gene was identified by sequence comparison with metH′ in P. putida P8 (15). The start codons of cti and metH in the P. putida DOT-T1 chromosome were separated by 182 bp.

To identify possible genes downstream of cti, a 4-kbp SphI fragment was cloned from total DNA of strain DOT-T1E digested with SphI. This clone, which overlaps the BglII clone by 1,626 bp (Fig. 1), was identified by colony-screening hybridization with a DIG-labeled PCR probe obtained with primers (5′-CCGGGGCTGGATACC-3′ and 5′-GCCTGAAGCGAATACAGC-3′) deduced from the sequenced 4.5-kb BglII clone. In all, 2.6 kbp of this clone was sequenced. We found a complete ORF, termed act, in the same orientation as cti. Sequence analysis showed that act encoded a protein containing 344 amino acids (Mr,calc = 39,288) that showed similarities to acetyltransferases. The stop codon of cti and the start codon of act were 194 bp apart. A putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence (AGGG) and a putative sigma 54 promoter were identified (Fig. 1). The acetyltransferase Act was identified by sequence comparisons and showed the highest amino acid sequence identity (30.1%) to ExoZ, a protein involved in the production of acidic exopolysaccharides (4). However, comparative sequence studies revealed further sequence similarities to acetyltransferases, such as macrolide 3-O-acyltransferase (27.1% identity) (1), integral membrane acetyltransferase (26.3% identity) (27), and 3-O-acyltransferase MdmB (24.7% identity) (12).

Construction of a Cti knockout mutant of P. putida DOT-T1 by gene replacement.

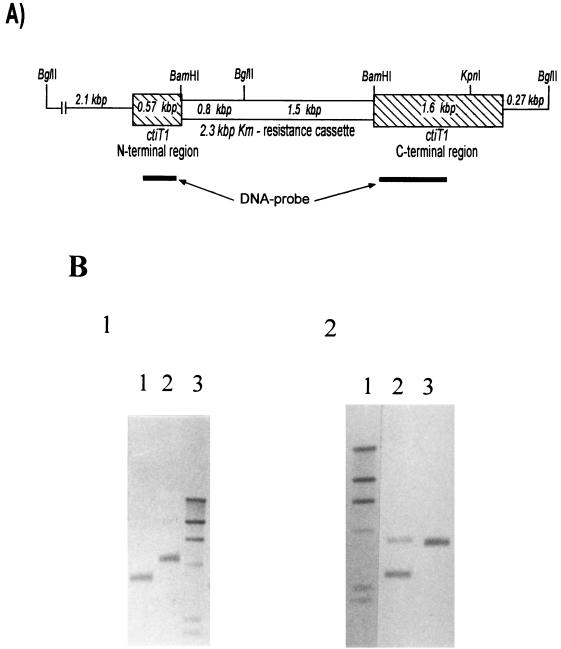

A mutant unable to synthesize Cti was generated by homologous recombination of a knocked-out cti gene with the wild-type gene. The cti gene was manipulated by deleting an internal 68-bp stretch and inserting a kanamycin cassette (Fig. 2A).

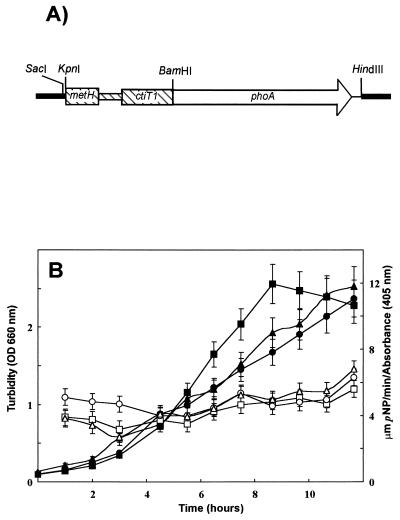

FIG. 2.

Construction of a mutant cti gene to obtain a CtiT null mutant. (A) Map of the manipulated cti gene. An internal sequence of 68 bp of the cti gene was deleted and replaced by the kanamycin cassette obtained from plasmid pHP45Ω-Km. The hybridization sites for the cti DNA probe (used for Southern blots) are indicated. (B) Southern blot hybridization of the chromosomal DNA of the wild-type strain DOT-T1E and the mutant strain DOT-T1Ecti0 with a 1.5-kbp cti DNA probe (as in panel A). For blot 1, lanes 1 and 2 contain DOT-T1E digested with BglII-KpnI and BglII, respectively, and lane 3 contains DIG-labeled DNA marker (λ-genomic DNA digested with HindIII); for blot-2, lane 1 contains DIG-labeled λ DNA digested with HindIII and lanes 2 and 3 contain mutant DOT-T1Ecti0 DNA digested with BglII-KpnI and BglII, respectively. The sizes of the bands of the λ marker from top to bottom are 23.1, 9.4, 6.5, 4.3, 2.3, and 2.1 kb. In a BglII digest, the wild-type gene (blot 1, lane 2) appeared at 4.5 kbp and the mutant (blot 2, lane 3) showed two bands at 3.5 kbp (2.1 + 0.57 + 0.8 kbp) and 3.4 kbp (1.5 + 1.6 + 0.27 kbp), which are indistinguishable in the blot. To separate the bands, a BglII-KpnI digest was performed. The wild-type band was shortened by 1 kbp to 3.5 kbp (blot 1, lane 1), and the 3.4-kbp band of the mutant was shortened to 2.4 kbp (blot 2, lane 2).

To obtain a cti clone with an internal deletion (68 bp) and restriction sites for further subcloning, crossover PCR deletion products were constructed in two steps (23). First, two PCR products of cti were generated, one for the N-terminal region starting at base +76 (the cti ATG start codon) to +647 (596-bp product; primers N1 [5′-CCCCGAGCTCAGCCCGGCTATTTCCTACA-3′] and N2 [5′-ACCGCCCGGATCCCTGGCGGCGAGCAGGGCCACTTCTT-3′]) and the other for the C-terminal region starting at position +715 to +2289 (1,600-bp product; primers C1 [5′-GCCGCCAGGGATCCGGGCGGTTGAGCAGTTCTTCCC-3′] and C2 [5′-ATCAGAAGCTTTCGTACCGGTTCATGTCCA-3′]). (Primers N1 and C2 had a SacI and a HindIII restriction site attached, respectively. Primers N2 and C1 both had a BamHI site and were complementary at their 5′ end over 21 bp [underlined].) Both PCR products were purified, and in a second PCR, both products were mixed and used as templates with primers N1 and C2. The 2,175-bp fusion product was gel purified, cut with SacI and HindIII, ligated into a SacI-HindIII-digested pUC18Not vector (14), and transformed into E. coli DH5α.

A kanamycin resistance gene of 2,200 bp, flanked by transcriptional stop signals, was excised from plasmid pHP45Ω-Km (10) with BamHI and ligated into the BamHI site of the crossover PCR product to yield pUC18NotctiKm. This construct was cut with NotI, ligated into a NotI-digested suicide vector, pKNG101 (20), to yield pKNG101ctiKm, and transformed into E. coli CC118λPIR. Plasmid pKNG101ctiKm was mobilized from E. coli CC118λPIR into P. putida DOT-T1E. The cells were plated on benzoate minimal medium containing kanamycin and streptomycin. This medium selects for the transconjugants of P. putida DOT-T1E bearing a cointegrate of plasmid pKNG101ctiKm in the chromosome incorporated by a single homologous recombination event (20, 35). The transconjugants were unable to grow in the presence of 8% (wt/vol) sucrose in LB medium because of the synthesis of levans, a product formed by the sacB gene product. One random colony of these cointegrates was chosen and grown overnight at 30°C in LB medium without antibiotics to select for the second recombination event, which resulted in the loss of the wild-type gene, the Smr marker, and the sacB gene. The resulting P. putida DOT-T1E was expected to be sucrose tolerant, Kmr and Sms. Clones exhibiting these features were termed P. putida DOT-T1cti0, and a random clone was retained for further characterization.

The successful formation of the cointegrate (insertion of the suicide plasmid construct pKNG101ctiKm into the chromosome), occurred after the first recombination event, and the resolved cointegrate formation (second recombination event, in which the plasmid is excised from the chromosome) was confirmed by Southern blotting. In both cases, the wild-type band disappeared (the resolved clone is shown in Fig. 2B). In addition, we confirmed the absence of the Cti protein by analyzing the fatty acid profile by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Table 1). The Cti-null mutant of P. putida DOT-T1E grown on LB and minimal medium in the presence of toluene in the vapor phase showed none of the trans fatty acids that had been detected in the wild type under the same growth conditions (Table 1).

Characterization of the Cti-null mutant.

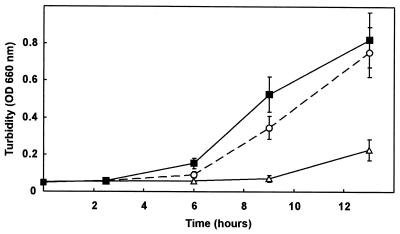

We further characterized the phenotype of the Cti-null mutant in physiological studies. When an LB preculture was used to inoculate minimal medium with toluene in the vapor phase as the sole source of carbon and energy, a lag phase of about 4 h was observed for the wild type whereas the mutant strain had a lag phase of about 9 h (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Growth curves of P. putida DOT-T1E, DOT-T1Ecti0, and the complemented strain DOT-T1Ecti0C in the presence of toluene in the vapor phase. All strains were precultured on LB medium overnight and then transferred to minimal medium with toluene supplied in the gas phase. Growth was determined at the indicated times. ■, DOT-T1E (wild type); ▵, DOT-T1Ecti0; ○, DOT-T1Ecti0C. OD 660 nm, optical density at 660 nm.

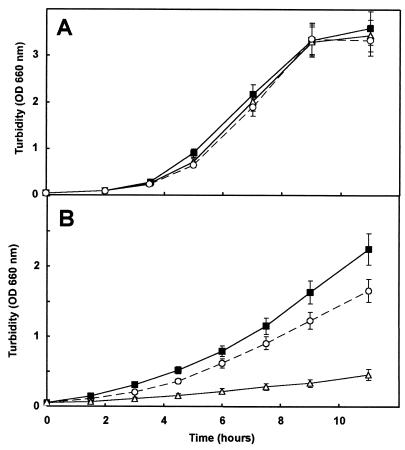

A different survival rate of mutant and wild-type cells in LB medium was observed when cultures were shocked with 0.08% (vol/vol) toluene added directly to the liquid medium. In all, 35% of the wild-type cells died and 90% of the DOT-T1cti0 cells did not survive the toluene shock. However, mutant cells that survived the solvent shock were able to grow at a rate similar to that of the wild-type (doubling times were dT1-Cti0 = 1.72 h and dDOT-T1E = 1.97 h). We also tested the temperature sensitivity of both strains, which were routinely grown at 30°C on minimal medium with glucose. No difference in the growth rate was observed at this temperature (Fig. 4A). At 38.5°C, in the same medium, the Cti-null mutant grew significantly slower than the wild type (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, at 38.5°C no growth was observed for DOT-T1cti0 when toluene was the sole source of carbon and energy. However, the wild type grew under these conditions, albeit at a significantly slower rate than with glucose.

FIG. 4.

Temperature-dependent growth curves of P. putida DOT-T1E, DOT-T1Ecti0, and the complemented strain DOT-T1Ecti0C. Bacterial cells were precultured in LB medium at 30°C. Then the cultures were diluted 1:100 in the same medium and incubated at 30°C (A) or 38.5°C (B). Growth was determined at the indicated times. ■, DOT-T1E (wild type); ▵, DOT-T1Ecti0; ○, DOT-T1Ecti0C. OD 660 nm, optical density at 660 nm.

Complementation of P. putida DOT-T1cti0.

We complemented the mutant strain DOT-T1cti0 with a plasmid carrying the intact cti gene. The original 4.5-kb BglII clone (plasmid pUC18Not), which carries the complete cti gene and its promoter region (Fig. 1), was cut with SacI and HindIII and ligated into plasmid pJB3Tc19. The new construct, termed pJBctiT1, was transferred into DOT-T1cti0 via triparental mating. At 38.5°C, the complemented mutant strain grew at a rate similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 4B). When minimal medium with toluene in the vapor phase was inoculated with an LB medium preculture, the lag phase was reduced (Fig. 3). Gas chromatography and mass spectrometry of the total fatty acids of the complemented strain DOT-T1cti0C (Table 1) showed the same fatty acid profile as for the wild type, including the trans isomers; these results confirm that the mutation was successfully complemented.

Construction and characterization of a Cti::PhoA fusion protein.

An in-frame fusion protein of the cis-trans isomerase and the membrane alkaline phosphatase, which is active only in the periplasmic space, was constructed by using the pUCH218 vector, which harbors the promoterless and signal sequence-deficient phoA gene with a multiple-cloning site at its N-terminal end (38). A 942-bp PCR product (bp −345 to +583 of cti ATG) that included the promoter region of cti and its membrane signal sequence (encoding the first 22 amino acids plus an additional 172 amino acids), with attached restriction sites (primers used were 5′-GTTGGTACCCTTCACATCGCTTG-3′ with a kpnI site and 5′-GCTGGATCCGCTGGTACTCCACC-3′ with a BamHI site), was amplified and ligated into the multiple-cloning site of vector pUCH218 to obtain construct pUCctiphoA. The cti::phoA fusion was excised with SacI-HindIII digestion and ligated into plasmid pJB3Tc19 (Fig. 5A). This construct, termed pJBctiphoA, was transferred into P. putida DOT-T1E by triparental mating. Transconjugants were selected as blue colonies on minimal medium containing benzoate, ampicillin, tetracycline, and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP). The accuracy of the in-frame fusion was further confirmed by DNA sequencing.

FIG. 5.

Map of in-frame fusion construct cti::phoA in plasmid pJBctiphoA and growth-dependent alkaline phosphatase activity in wild-type P. putida DOT-T1E transformed with plasmid pJBctiphoA. (A) The cti::phoA fusion in pJB3Tc19 yielded pJBctiphoA as described in the text. DNA from strain DOT-T1E is shown as a hatched area, and vector pJB3Tc19 is shown as thick lines. (B) PhoA activity of the cti::phoA fusion was measured in the presence and absence of toluene at the indicated times. ■ and □, DOT-T1E with pJBctiphoA grown on glucose; ▴ and ▵, DOT-T1E with pJBctiphoA grown on toluene in the gas phase; ● and ○ DOT-T1E with pJBctiphoA grown on glucose and toluene in gas phase. Solid symbols indicate growth curve, and open symbols indicate phosphatase activity (micromoles of p-nitrophenol per minute per turbidity unit [measured as optical density, OD, at 660 nm]).

P. putida DOT-T1E (pJBctiphoA) produced blue colonies in cultures containing BCIP regardless of the presence of toluene. (The leader sequence of Cti translocates the fusion protein to the periplasm, and the PhoA protein produces the blue color upon hydrolysis of BCIP). We therefore presume that Cti was expressed constitutively. To confirm this, we assayed PhoA activity in P. putida DOT-T1E (pJBctiphoA) in liquid medium under different conditions throughout the growth phases (Fig. 5B). There was no difference in PhoA activity when the cells were grown in minimal medium with glucose, glucose and toluene, or toluene only as the source of carbon and energy. Basal PhoA activity was approximately 5 μmol of 4-nitrophenol/min/turbidity unit at 660 nm in all cultures. The control strain, P. putida DOT-T1E, grown on glucose did not show PhoA activity.

Total DNA hybridization experiments to localize cti in Pseudomonas strains.

We checked for the presence of the cis-trans isomerase in various Pseudomonas strains by Southern blot analysis. Total DNA preparations of the Pseudomonas strains were digested with BglII or SalI, separated on an agarose gel, blotted, and hybridized with a 1.5-kbp DIG-labeled PCR product of cti (primers, 5′-GCCCGGCTATTTCCTACA-3′ and 5′-AGGCGCAGGAAGTTGAC-3′). Signals were obtained for most Pseudomonas strains (Table 2), and the hybridization pattern was identical for all P. putida strains.

DISCUSSION

The gene encoding the cis-trans isomerase of esterified fatty acids and the surrounding DNA in strain P. putida DOT-T1E was sequenced. Upstream of the cti gene in P. putida DOT-T1E, a methionine synthetase gene, metH, was found, as in P. putida P8. The two synthetases were identical over the 109 amino acids sequenced so far. Downstream of cti in P. putida DOT-T1E we found a putative stop signal (stem-loop) and a putative acetyltransferase (act) gene preceded by a presumed sigma-54 promoter sequence in the noncoding region between the two genes (25). We therefore assume that cti is transcribed as a monocistronic transcriptional unit (Fig. 1).

The isomerase Cti of P. putida DOT-T1E was found to have high sequence identity to Cti of P. putida P8 (15). In addition, in the P. aeruginosa genomics data bank we found an ORF whose translation yielded a protein that exhibited 65% identity (contig 53, bp 1278998-1281287) to the above-mentioned cis-trans isomerases. We also found in The Institute for Genomic Research Website (38a) a protein from V. cholerae that had 39% identity to the Cti protein of P. putida DOT-T1E. This is in agreement with the identification of trans fatty acids in strains of the genus Vibrio (21). These proteins may constitute a novel enzyme group.

RNA primer extension experiments for cti in P. putida DOT-T1E showed that multiple bands were detected in the presence and in the absence of toluene. We thus concluded that cti is constitutively expressed and that its expression might be driven by multiple promoters; however, the exact location of these promoters is unknown. The constitutive expression of cti was also verified by using a cti′::′phoA gene fusion (Fig. 5). Furthermore, physiological experiments showed that cis-trans isomerization of fatty acids takes place immediately after cells are exposed to solvents (13, 29, 30, 33). This confirms that the isomerase is constitutively expressed. However, the nature of cis-trans isomerase activation is still unknown. Since different environmental signals including solvent exposure, temperature increase, or salt shock, can trigger cis-trans isomerization (24), it seems likely that a change in membrane structure affects the enzyme and causes activation. In this regard, Pedrotta and Witholt (29) have recently purified the Cti from P. oleovorans, which can now be used to study the mechanism of activation of this family of proteins. Our results with the PhoA fusion suggest that in P. putida DOT-T1E the enzyme may be localized in the periplasm, where access to esterified phospholipids is possible, in agreement with the results of Holtwick et al. (15).

Recently, another bacterial cis-trans isomerase of esterified fatty acids was biochemically characterized in Pseudomonas sp. strain E-3 (28). The Cti enzyme of strain E3 catalyzes the isomerization of esterified as well as free fatty acids without a shift in the double-bond position in the fatty acid chain. This isomerase contains a large percentage of hydrophobic amino acids, but no protein sequence data is available. The molecular weight of this isomerase, determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, was 80,000, a value in the same range as that of Cti isomerase (Mr = 86,960). However, the total amino acid composition showed clear differences: the glycine and serine contents of Cti of strain E3 were 21.2 and 11.9%, respectively, of the total amino acid composition, whereas glycine and serine made up 6.6 and 5%, respectively, of the deduced Cti protein of P. putida DOT-T1. In addition, the substrate range differed markedly from that of the Cti enzymes of P. putida P8 and DOT-T1E, since cis-vaccenic acid (C18:1,11), a common fatty acid in phospholipids of P. putida, is not a substrate of Cti of strain E3.

The function of the Cti isomerase in P. putida DOT-T1E was unequivocally established with the Cti-null mutant, which was deficient in trans fatty acids. The ability to isomerize cis fatty acids was restored to the mutant strain upon complementation with the cti gene cloned in a wide-host-range vector (Fig. 2 and 4; Table 1). The lack of cis-trans isomerization after a shock with 0.08% (vol/vol) toluene increased the mortality of DOT-T1cti0 sixfold in comparison to the wild type. The mutant strain also showed slower rates at temperatures higher than 37°C. Consequently, at higher temperatures the lack of trans isomers cannot be compensated for by changes in the lipid bilayer. Similar findings were reported by Holtwick et al. (15), who used temperature sensitivity to screen for Cti-deficient clones of P. putida P8.

In Southern blot analyses, we used a P. putida DOT-T1E cti probe to check for the presence of the gene encoding the isomerase in other microorganisms (Table 2). Almost all pseudomonads, but especially P. putida, gave clear signals, except for Ralstonia solanacearum and Brevundimonas diminuta strains. Hence, the cis-trans isomerase gene seems to be widespread in pseudomonads but not essential. In this regard, the cis-trans isomerase gene of P. putida KT2440, a non-solvent-resistant strain (19), was sequenced. The deduced protein sequence for this Cti enzyme had 99.5 and 95.6% amino acid sequence identity to Cti of P. putida DOT-T1E and P8, respectively.

In summary, cis-trans isomerization of esterified fatty acids represents a short-term response to environmental stress in P. putida. This allows cells to adapt immediately to new environmental conditions under which denser membrane packing is a selective advantage. Thus, cells can gain time for the de novo biosynthesis of membrane components, which permits a more precise and broader adjustment to a specific stress. Regarding solvent stress, the following changes in the content and in the rate of phospholipid biosynthesis are involved: shifts in the saturated/unsaturated fatty acid ratio, synthesis of solvent extrusion pumps, modifications in lipid polysaccharides, and alterations in membrane protein content (8, 30, 33, 40). Changes in the phospholipid composition were observed as late as 15 min after solvent exposure in one P. putida strain (30), but cis-trans isomerization was observed immediately (13, 30, 33). This rapid, nonspecific mechanism of adaptation may account for the fact that most solvent-tolerant strains are P. putida. The presence of Cti in non-solvent-resistant strains and the survival of the Cti-null mutant in the presence of high toluene concentrations indicate that the isomerase is not the most crucial element in solvent resistance but is an important factor in preventing initial cell damage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by grants from the European Commission (BIO4-CT97-2270), the Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (BIO97-0657), and the Junta de Andalucía. F. Junker was supported by an EC grant (ERB-4001-GT-97-0033) from the Biotechnology Programme.

We are grateful to P. Godoy for doing the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of the fatty acids and to J. J. Rodríguez-Herva for his advice on experimental strategies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arisawa A, Kawamura N, Takeda K, Tsunekawa H, Okamura K, Okamoto R. Cloning of the macrolide antibiotic biosynthesis gene acyA, which encodes 3-O-acyltransferase, from Streptomyces thermotolerans and its use for direct fermentative production of a hybrid macrolide antibiotic. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2657–2660. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2657-2660.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blatny J M, Brautaset T, Winther-Larsen H C, Haugan K, Valla S. Construction and use of a versatile set of broad-host-range cloning and expression vectors based on the RK2 replicon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:370–379. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.370-379.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bligh E G, Dyer W J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buendia A M, Enenkel B, Koplin R, Niehaus K, Arnold W, Puhler A. The Rhizobium meliloti exoZ1exoB fragment of megaplasmid 2: ExoB functions as a UDP-glucose 4-epimerase and ExoZ shows homology to NodX of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae strain TOM. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1519–1530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Q, Jansen D B, Witholt B. Growth on octane alters the membrane lipid fatty acids of Pseudomonas oleovorans due to the induction of the alKB and synthesis of octanol. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6894–6901. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6894-6901.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruden D L, Wolfram J H, Rogers R D, Gibson D T. Physiological properties of a Pseudomonas strain which grows with p-xylene in a two-phase (organic-aqueous) medium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2723–2729. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.2723-2729.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson C, Belloch C, García-López M D, Uruburu F, editors. Coleccioón Española de Cultivos Tipo, catalogue of strains. Valencia, Spain: University of Valencia Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diefenbach R, Keweloh H. Synthesis of trans unsaturated fatty acids in Pseudomonas putida P8 by direct isomerization of the double bond of lipids. Arch Microbiol. 1994;162:120–125. doi: 10.1007/s002030050112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esteve-Núñez A, Ramos J L. Metabolism of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene by Pseudomonas sp. JLR11. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32:3802–3808. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fellay R, Frey J, Krisch H. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1987;52:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson D T, Hensley M, Yoshioka H, Mabry T J. Formation of (+)-cis-2,3-dihydroxy-1-methylcyclohexa-4,6-diene from toluene by Pseudomonas putida. Biochemistry. 1970;9:1626–1630. doi: 10.1021/bi00809a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hara O, Hutchinson C R. A macrolide 3-O-acyltransferase gene from the midecamycin-producing species Streptomyces mycarofaciens. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5141–5144. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.5141-5144.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heipieper H J, de Bont J A M. Adaptation of Pseudomonas putida S12 to ethanol and toluene at the level of fatty acid composition of membranes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4440–4444. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4440-4444.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign DNA in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holtwick R, Meinhardt F, Keweloh H. cis-trans isomerization of unsaturated fatty acids: cloning and sequencing of the cti gene from Pseudomonas putida P8. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4292–4297. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4292-4297.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopp T, Woods K R. Prediction of protein antigenic determinants from amino acid sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:3824–3828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huertas, M. J., E. Duque, R. Roselló-Mora, G. Mosqueda, P. Godoy, B. Christensen, S. Mølin, and J. L. Ramos. Unpublished data.

- 18.Inoue A, Horikoshi K. A Pseudomonas thrives in high concentrations of toluene. Nature (London) 1989;338:264–266. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junker, F., and J. L. Ramos. 1998. GenBank accession no. AF110739.

- 20.Kaniga K, Delor I, Cornelis G R. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene. 1991;109:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keweloh H, Heipieper H J. Trans unsaturated fatty acids in bacteria. Lipids. 1996;31:129–137. doi: 10.1007/BF02522611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kieboom J, Dennis J J, de Bont J A M, Zylstra G J. Identification and molecular characterization of an efflux pump involved in Pseudomonas putida S-12 solvent tolerance. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:85–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Link A J, Phillips D, Church G M. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6228–6237. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6228-6237.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loffeld B, Keweloh H. cis/trans isomerization of unsaturated fatty acids as possible control mechanism of membrane fluidity in Pseudomonas putida P8. Lipids. 1996;31:811–815. doi: 10.1007/BF02522976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marqués S, Ramos J L, Timmis K N. Analysis of the mRNA structure of the Pseudomonas meta-fission pathway operon around the transcription initiation point, the xylTE and the xylFJ region. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1216:227–237. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosqueda G, Ramos-Gonzales M I, Ramos J L. Toluene metabolization by the solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1 strain, and its role in solvent impermeabilization. Gene. 1998;232:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakano Y, Yoshida Y, Yamashita Y, Koga T. A gene cluster for 6-deoxy-l-talan synthesis in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1442:409–414. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okuyama H, Ueno A, Enari D, Morita N, Kusano T. Purification and characterization of 9-hexadecaenoic acid cis-trans isomerase from Pseudomonas sp. strain E-3. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s002030050537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedrotta V, Witholt B. Isolation and characterization of the cis/trans fatty-unsaturated isomerase of Pseudomonas oleovorans. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3256–3261. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3256-3261.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinkart H C, White D C. Phospholipid biosynthesis and solvent tolerance in Pseudomonas putida strains. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4219–4226. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4219-4226.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramos J L, Duque E, Godoy P, Segura A. Efflux pumps involved in toluene tolerance in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3323–3329. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3323-3329.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramos J L, Duque E, Huertas M J, Haidour A. Isolation and expansion of the catabolic potential of a Pseudomonas putida strain able to grow in the presence of high concentrations of aromatic hydrocarbons. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3911–3916. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3911-3916.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos J L, Duque E, Rodriguez-Herva J-J, Godoy P, Haidour A, Reyes F, Fernandez-Barrero A. Mechanisms for solvent tolerance in bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3887–3890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramos-González M I, Ruíz-Cabello F, Brettar I, Garrido F, Ramos J L. Tracking genetically engineered bacteria: monoclonal antibodies against surface determinants of the soil bacterium Pseudomonas putida 2440. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2978–2985. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.2978-2985.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodríguez-Herva J J, Ramos J L. Characterization of an OprL null mutant of Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5836–5840. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5836-5840.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sikkema J, de Bont J A M, Poolman B. Mechanisms of membrane toxicity of hydrocarbons. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:201–222. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.201-222.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strom M S, Lory S. Mapping of export signals of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pilin with alkaline phosphatase. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3181–3188. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.3181-3188.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38a.The Institute for Genomic Research. Pseudomonal genome. Sequences. [Online.] http://www.tigr.org. [13 June 1999, last date accessed].

- 39.Wagner K U, Masepohl B, Pistorius E K. The cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 contains a second alkaline phosphatase encoded by phoV. Microbiology. 1995;141:3049–3058. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-12-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber F J, Isken S, de Bont J A M. cis/trans isomerization of fatty acids as a defense mechanism of Pseudomonas putida strains to toxic concentrations of toluene. Microbiology. 1994;140:2013–2017. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whited G M, Gibson D T. Separation and partial characterization of the enzymes of the toluene-4-monooxygenase catabolic pathway in Pseudomonas mendocina KR1. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3017–3020. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.3017-3020.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]