Abstract

Introduction

Involving patients in decision making adds value in the context of pharmacovigilance (PV). This added value goes beyond participation in spontaneous reporting systems for adverse drug reactions. However, there is a gap between allowing patients to report and actual patient involvement. Views regarding best practices from regulators, patient organizations and pharmaceutical companies could help increase and improve patient involvement in PV.

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the factors contributing to best practices for patient involvement in PV and to develop a definition of patient involvement based on a qualitative multistakeholder study across Europe.

Methods

A literature review was conducted to map the field of study and obtain insights for the elaboration of an interview guide. Subsequently, patient representatives, members of the pharmaceutical industry and regulators were invited to participate in interviews. These interviews were analyzed using NVIVO® software and employing reflective thematic analysis.

Results

A total of 20 interviews were conducted with representatives at both the national and European levels. The best practices identified were engagement from the start, face-to-face communication, a full circle of feedback, same-level partners, structured involvement and guidelines, establishing common goals, patient education and empowerment, and developing trust and balance. These activities can be implemented via deep collaboration among stakeholders. A definition of patient involvement was constructed in accordance with the input of all stakeholder groups, which reflects the involvement of all types of patients at all levels of the decision-making process.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed a definition for patient involvement based on qualitative interviews. The factors contributing to best practices for patient involvement were mentioned across stakeholder groups and aimed to stimulate patient involvement in PV. Patients are eager to become equal partners and to engage effortlessly in the same manner as other stakeholders.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40264-022-01222-y.

Key Points

| Qualitative interviews with stakeholders in pharmacovigilance (PV) can help identify factors that contribute to improving patient involvement in PV. |

| Patients are eager to become equal partners in PV and to be involved effortlessly in the same manner as other stakeholders. |

| Best practices for patient involvement were identified and can be implemented via deep collaboration among stakeholders. |

Introduction

In recent years, patient involvement has become increasingly important in the context of pharmacovigilance (PV). Direct patient reporting is one of the most prevalent ways in which patients can be involved. Previous studies have proven the importance of such reporting and concluded that it helps uncover blind spots in drug safety monitoring, as patient reports pertain not only to prescription drugs but also to over-the-counter (OTC) medicines and nonauthorized products such as herbals, macrobiotics, and other products that are not reported by healthcare professionals (HCPs). In addition, direct patient reports promote early safety signals more than situations in which only the HCP reports are considered [1].

However, patients are considered to be important stakeholders who can be involved in activities other than adverse drug reaction (ADR) reporting, such as safety data communication. Patient organizations have shown interest in topics related to drug safety and aim to participate in PV in a more active way. These organizations appear to play an important role in encouraging patients to participate in the drug safety environment, both as communication platforms to disseminate safety information and signals to patients in a more effective way than is possible via regulatory and scientific channels and as powerful educational platforms that provide safety data for other stakeholders [2–5].

Another role played by patients that must be highlighted is that of expert patients, a term that refers to patients who live with a chronic illness, have extensive knowledge of the management and implications of their disease, and possess personal knowledge and experience regarding their illness [6, 7]. Expert patients play a key role, as they have the unique opportunity to clarify patients' values and priorities, and are able to identify needs that are not considered highly by HCPs; this knowledge allows expert patients to work contribute to the development of comprehensive care and disease management and to participate in clinical decision making [6]. Expert patients also act as educators for other patients, provide feedback regarding care delivery, and are involved in the development and implementation of guidelines for practice as well as in the design and conduct of research initiatives and clinical studies [7].

In an effort to enhance the role of expert patients, several ‘expert patient programs’ and ‘chronic disease self-management programs’ have been established as a way to educate patients and motivate them to employ their own skills and knowledge to take control over their lives with chronic illnesses [6].

Finally, regular patients who are not actively involved in patient organizations or educational programs also play an important role within the PV system, as they are uniquely positioned to serve as vigilant monitors of safety; they can detect medication errors, quality issues, drug misuse and other important drug safety concerns and play an active role in the therapeutic decision-making process [6]. For instance, during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there has been a surge in the number of reports from the general public regarding COVID-19 vaccines, which can contribute to our knowledge of the safety profile of these vaccines in daily practice [8].

Pharmaceutical companies have started to create more patient-centered initiatives; one recent study found that the most frequently implemented initiatives included patient organization landscape analysis, support of patient advocacy groups, patient advisory boards, home nursing networks, social media/online communities, lay-language summaries of the results of clinical trials, new clinical data collection applications (apps), adaptive trial designs and patient involvement in study feasibility and design; however, at the time of that study, most of these initiatives were in the planning or piloting stages and had not yet arrived at the implementation stage [9, 10].

Despite all these efforts on the part of all stakeholders, there are still challenges to overcome if patients are to play a larger role in PV, with communication being one of the main challenges in this context. It is important to determine whether current initiatives are fulfilling patients' needs and making them feel truly involved, as well as to identify the areas in which there is still room for improvement.

For the purpose of this study, we have chosen to focus on the term patient involvement, although the terms patient involvement and engagement are frequently used interchangeably, and there are no established definitions of these terms or clear differences between them [11, 12]. However, certain elements have been mentioned by different authors when referring to these terms, of which it is useful to have a general understanding. The concept of patient involvement refers to the participation of patients in decision making related to their own health problems, such as choices regarding their treatment, and public health issues, such as the development, approval and marketing of medicines [13–15]. Another definition of this term refers to sharing feelings, emotions, and information between patients and health care professionals, thus improving the relationship between those parties and making the patient more receptive to the guidelines issued by these professionals [13, 15]. Patient involvement can also be defined as the continuous process of exchanging knowledge and ideas among the various parties involved via the implementation of interventions intended to promote the participation of interested stakeholders [12]. Other authors have referred to the concept of patient engagement as "the active, meaningful, authentic and collaborative interaction between patients and researchers throughout all stages of the research process, in which research decision-making is guided by the contributions of patients as partners, recognizing their unique experiences, values and knowledge" [16].

Within the field of PV, the concept of patient engagement is understood in terms of the participation of patients in the safety decision-making process at different levels, for example, in the regulatory field, by allowing patients to participate in public hearings at which decisions are made regarding crucial safety issues; patients can participate as safety data providers, for example, through patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and contributions of real-life data, which can guide decision making, and they can ultimately make therapeutic decisions regarding their own health based on the available information [1, 17–20]. One recent study conceptualized the term PV engagement as an ongoing process of knowledge exchange among stakeholders that implies the crucially important mutuality of this process [21], indicating that such engagement is a two-way process of communication in which patients also share their knowledge with other stakeholders. This form of knowledge exchange can take place via different lines of communication, for example, through direct patient reporting or public hearings, but it also recognizes the different roles that patients can play in PV, such as serving as expert patients or participating in patient organizations, and collaborating with them to ensure that patients’ voices and knowledge are shared at every level.

Views regarding best practices from regulators, patient organizations and pharmaceutical companies could be helpful to increase and improve patient involvement in PV. To obtain insight into factors that are important for improving patient involvement in the context of PV, a qualitative multistakeholder study across Europe was conducted. In-depth interviews were conducted to explore participants' views and perceptions of patient involvement and the activities that are currently being implemented to enhance the participation of patients in PV. The aim of this study was to investigate the factors that contribute to patient involvement in PV and to develop a definition of patient involvement based on a qualitative multistakeholder study across Europe.

Methods

This study conducted qualitative research using an inductive methodology [22] and was designed to adhere to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist [23].

Literature Search

The first step was to use a literature review of PubMed® to identify the current practices used by stakeholders to involve patients in PV. In addition, the literature review aimed to define the initial stakeholders to be included in the interview stage. A search was conducted in PubMed® by one of the authors (MvH) on 2 February 2021, with a time range filter between 2010 and 2021. Publications in English and Spanish were included. The electronic search strategy implemented to conducted the literature review is available as electronic supplementary material (ESM) 1. Articles regarding patient involvement in areas other than postmarketing surveillance, for example, in drug development, were not included. Finally, references across articles were checked to identify interesting articles that could be included in the study. EndNote X9® software (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA) was used for the selection of articles and the detection of duplicates. Two authors (MvH, KC) screened the publications and the results were then discussed with another author (FvH). Findings from the articles were extracted using an extraction template in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) that contained the following fields: stakeholder, full reference, description of patient involvement initiatives.

Based on the findings, a semi-structured interview guide was designed, and purposive sampling was used to recruit participants for the interviews.

Interview Guide Design

Based on the results of the literature review, a semi-structured interview guide was designed. The interview guide contained 17 open-ended questions to allow the interviewees to provide in-depth answers related to the participation of patients in PV. The topics included in the interview guide were the definition of patient involvement, the importance of patient involvement, and the activities they have conducted/in which they have participated or that they would like to conduct/in which they would like to participate in the future, as well as the benefits of patient involvement and ways of incorporating feedback from patients themselves.

Interviewees were asked 12 questions from this list of 17 questions depending on the stakeholder group to which they belonged, and each interview was estimated to last 30 min. The interview guide containing all 17 questions is available as ESM 2.

The first concept interview guide, which was developed by MvF and FvH, was discussed during an online (recorded) brainstorming session that included all authors and that was held on 5 March 2021, which suggested feedback for the guide’s improvement. Finally, the interview guide was field-tested by reference to three subjects (research interns and colleagues) and subsequently altered.

Participant Selection

Three stakeholder groups were identified as most relevant to the research question, namely drug regulators (national competent authorities or European Union [EU] regulators), representatives of the pharmaceutical industry and representatives of patient organizations. Only stakeholders who were based in Europe were selected. Participants were further categorized into two levels: stakeholders on a European level and stakeholders on a national level.

After using the literature review to identify the stakeholders to be included in the research, the first interviewees to be invited were contacts of the researchers; subsequently, new participants were recruited via the snowballing technique. This series of purposive sampling techniques ensured the selection of particularly knowledgeable participants who were directly involved or interested in patient involvement in PV [24].

Recruitment Process and Confidentiality

An email invitation was sent to the first potential interviewees, including a formal invitation letter that was sent alongside an informed consent form that adhered to the general data protection regulations of the EU [25]. In the event that the first invitation email received no response, two reminder emails were sent following a 2-week interval.

Participants who agreed to participate scheduled an interview appointment with the lead researcher. The interviews were conducted via Zoom®, Microsoft Teams® or Skype®, and all interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim using oTranscribe.com (MuckRock Foundation, Somerville, MA, USA).

Interviewees were asked to refer the researcher to potential participants from their personal contact lists who were knowledgeable in the field of PV and belonged to one of the stakeholder groups included in this study.

To maintain the confidentiality of the interviewees, pseudonymization via an alphanumeric code was employed in the presentation of the results. Participants received a copy of the final report describing their data for comments as requested by the COREQ quality guidelines [23].

The number of interviewees was determined based on data saturation. Data saturation is defined as the point at which no new codes emerge from the data [26, 27]. At the point of data saturation, the snowballing process terminated and only already scheduled interviews were completed.

Data Analysis and Coding Process

The transcripts of the interviews were imported into QSR International Pty Ltd (2020) NVivo® software [28] for coding and analysis. In vivo coding was used to minimize interpretation bias [29].

Data coding for thematic analysis consists of identifying data fragments in terms of their meaning and labeling them with a code (codes represent the third-level hierarchy) that assigns a symbolic value to, and evokes the meaning of, that piece of information [22, 30]. As this process continues, relations or connections among these codes can be depicted, which generates high-level concepts (which represent the second-level hierarchy). Groups of related high-level concepts are subsequently assembled into larger groups to create themes (which represent the first-level hierarchy).

To reduce the risk for interpretation bias, the first interview was coded individually by three researchers (MvH, KC and FvH), and disagreements regarding the coding were discussed to verify the credibility of the coding [30]. The coding process remains active throughout the analysis, i.e., active modification of the codes, high-level concepts and themes continues until a final set of connections can be clearly established. The emerging structure connecting all three levels of the hierarchy into a tree structure emerges through consensus among the researchers.

If a study in The Netherlands is subject to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO), it must undergo a review by an accredited Medical Research Ethics Committee or the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO). This study does not fall under the WMO act. Participants in the study provided a written statement of consent to participate prior to participating in the study [31].

Definition of Patient Involvement

As part of the interview, patients were asked to provide their definitions of patient involvement. The answers to this question were included in the coding process and were used to elaborate a multistakeholder definition of this concept.

A word cloud was generated using NVivo® using the most frequently used words, which were analyzed based on the context in which they were used [32]. The most frequently mentioned ideas were coded together into high-level concepts and were located within the definition. Following the analysis, the most frequently used words and their contexts were merged into a definition that reflects the ideas of all three stakeholder groups.

Results

A semi-structured interview guide was designed based on the literature review; a total of 61 articles were identified, including 54 from the database search and 7 articles that were added following the cross-reference check. After initial screening, 37 articles were excluded due to being inaccessible or failing to meet the selection criteria, which focused on articles referring to current activities intended to involve patients in PV, articles describing the definition of patient involvement, articles highlighting the importance of patient involvement in PV, and articles describing the stakeholders who are involved in PV. In total, 24 studies were included in the review. The complete list of articles that were included in the literature review, which were obtained from the search engine and the cross-reference check, is available as ESM 2.

The literature review led to the identification of three stakeholders for inclusion in the study and that of the patient involvement activities in which those stakeholders were engaged.

The results of the literature review also served as the foundation for the creation of the interview guide, which consisted of 17 questions. Not all 17 questions were asked of every interviewee, and some questions were modified in accordance with the type of stakeholder in question. Therefore, only 12 of the 17 questions were asked during each interview.

A total of 30 participants were invited and 20 agreed to participate in the interviews. Participants were categorized as regulatory agency representatives (n = 5), marketing authorization holder representatives (n = 6), patient organization representatives (n = 8) or a neutral party—a supranational organization that fosters conversations among other stakeholder groups was added to obtain a neutral perspective on the research question (n = 1).

In one interview, two individuals represented one organization. For one interview, answers were accepted in written form via email due to time and scheduling constraints. All interviews were conducted between March and June 2021.

Study Participants

A total of 20 interviews were conducted. Table 1 presents an overview of the participants.

Table 1.

Profiles and classification of participants

| Participant identifier | Sex | Type of stakeholder | Participant' s location | Organization' s location | Level of engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI01 | M | Patient representative | UK | Pan-European | European |

| SI02 | F | Regulator | The Netherlands | The Netherlands | National |

| SI03 | F | Regulator | The Netherlands | Pan-European | European |

| SI04 | F | Regulator | The Netherlands | Pan-European | European |

| SI05 | F | Patient representative | Luxemburg | National branch of a pan-European organization | National |

| SI06 | F | Patient representative | The Netherlands | The Netherlands | National |

| SI07 | M | Patient representative | Portugal | Portugal | National |

| SI08 | M | Patient representative | France | Pan-European | European |

| SI09 | F | Marketing authorization holder | The Netherlands | The Netherlands | National |

| SI10 | F | Patient representative | Denmark | National branch of a pan-European organization | National |

| SI11 | F | Regulator | Norway | Norway | National |

| SI12 | F | Neutral party | Sweden | Worldwide organization | European |

| SI13 | M | Patient representative | Spain | Spain | National |

| SI14 | M | Regulator | UK | UK | National |

| SI15 | M | Patient representative | Portugal | Portugal | National |

| SI16 | F | Marketing authorization holder | France | Organization's headquarters | National |

| SI17 | F | Marketing authorization holder | Belgium | Belgium | National |

| SI118 | F | Marketing authorization holder | The Netherlands | The Netherlands | National |

| SI19 | M | Marketing authorization holder | UK | British branch of a global organization | National |

| SI20 | M | Marketing authorization holder | Austria | Austrian branch of a global organization | National |

M male, F female

Interview Thematic Analysis

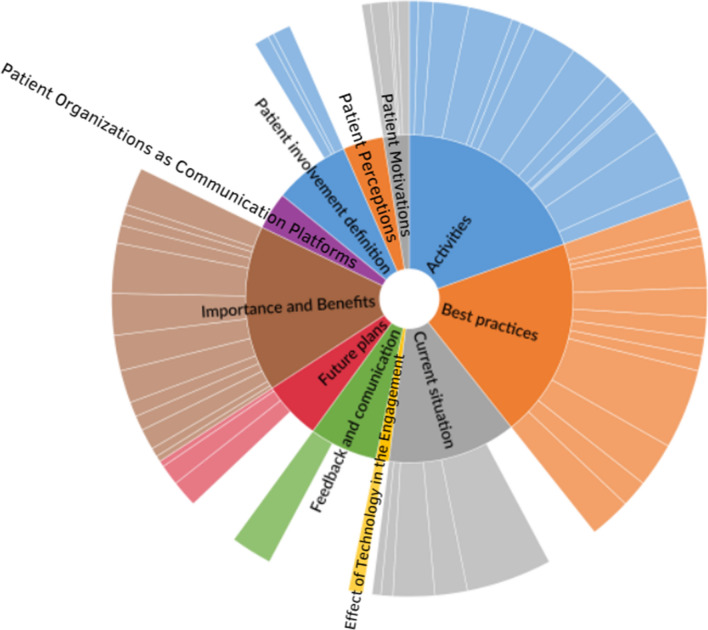

The general hierarchy chart of the coding structure from the data analysis using thematic analysis is shown in Fig. 1; the size and color saturation of each section represents the number of references pertaining to that theme. The chart is divided into a three-level coding hierarchy, according to which the inner circle represents the themes, which is followed by high-level concepts and ultimately individual codes.

Fig. 1.

Hierarchy chart of codes and themes across all stakeholder groups and levels

The ‘Best Practices’ theme refers not to specific activities but rather to the presence of elements or factors to which stakeholders referred to as important for meaningful and successful engagement with respect to actions to which patients could truly contribute as a partner. The high-level concepts pertaining to ‘best practices in patient involvement’ were noted by all groups of interviews and were classified as such because either they were mentioned by the majority or all stakeholder groups or because the majority or all of the participants from one specific group mentioned them.

The ‘Activities’ theme corresponds to specific activities and actions currently being implemented in the areas of patient involvement that the participants either helped organize or in which they were invited to participate. as well as participants’ perceptions regarding those activities.

The ‘Definition of Patient Involvement’ theme corresponds to the ideas that all stakeholders expressed regarding their own perceptions of the definition of patient involvement.

The ‘Importance and Benefits of Patient Involvement’ theme pertains to the main benefits that stakeholders view as resulting from real engagement with patients.

The theme ‘Current Situation’ refers to the ways in which stakeholders perceived the present state of patient engagement in PV and limitations in the relationships between the different stakeholders and patients.

The theme ‘Future Plans’ focuses on the activities that stakeholders plan to implement or would like to see implemented in the future to enhance the participation of patients in PV.

The theme ‘Feedback and Communication’ corresponds to the participants’ perceptions regarding the importance of communicating, the channels usually used to facilitate communication, and the drawbacks of some of those channels.

The theme ‘Patient Motivations’ includes the main reasons that patient representative participants discussed as motivations for patients to become involved and remain active in PV.

The ‘Patient Perceptions’ theme refers to the sentiments that patient representatives described when discussing the activities in which they were involved and their relationships with those working in the field of PV.

The ‘Patient Organizations as Communication Platforms’ theme refers to the stakeholders’ views of the role that patient organizations can play in the context of patient involvement as intermediaries in communications between regular patients and other stakeholders.

The ‘Effect of Technology on Engagement’ theme corresponds to the perceptions that participants discussed regarding the influence of the development of information technology in terms of the ways in which patients participate in the PV.

Based on the aim of this study, the Best Practices and Activities themes were chosen to be analyzed in-depth alongside the definition of patient involvement. Information regarding the themes that are not presented in depth in the results was used to improve our understanding of the situation under study.

Best Practices

The ‘Best Practices’ theme refers not to specific activities but rather to the presence of elements or factors to which stakeholders referred to as important for the meaningful and successful involvement of patients in actions in which they can truly contribute as a partner.

The high-level terms that comprise the theme of Best Practices are Patient Education and Empowerment, Engagement from the Start-Design, Face-to-Face Communication, Full Circle of Feedback, High-Level Contact Person, Managing Expectations, Patients as Same-Level Partners, Establishing Common Goals, Structured Involvement and Guidelines, Developing Trust and Balance, Constant Engagement and Engagement at Different Levels.

Four main high-level concepts under Best Practices were mentioned: Patient Education and Empowerment, Patients as Same-Level Partners, Engagement from the Start-Design, and Structured Involvement and Guidelines.

From a stakeholder perspective, Patients as Same-Level Partners was the topic regarding which stakeholder groups overlapped the most, since it was mentioned at all levels. Patient Education and Empowerment was mentioned by all groups, with the exception of national-level regulators, with a high frequency among patient representatives at the national level. Other topics that were mentioned across groups were Structured Involvement and Guidelines, with the exception of marketing authorization holders, and Engagement from the Start-Design, which was not mentioned by national-level patient representatives.

Among regulatory representatives at the European level, the most frequently discussed topics were Structured Involvement and Guidelines, Engagement from the Start-Design and Managing Expectations. However, at a national level, the discussion primarily focused on Setting Common Goals and working with Patients as Same-Level Partners.

At the European level, the main high-level concept mentioned by patient representatives was Patient Education and Empowerment, followed by the high-level concepts Contact Person and Structured Involvement and Guidelines, while at the national level, their main focus was on Patient Education and Empowerment and Developing Trust and Balance, followed by Full Circle of Feedback and Face-to-Face Communication. It is important to note that despite the fact that Developing Trust and Balance, Full Circle of Feedback and Face-to-Face Communication were among the most important topics for this group at the national level, these topics were not mentioned by other stakeholder groups quite so frequently.

For the marketing authorization holder group, the main concepts discussed were Patients as Same-Level Partners and High-Level Contact Person.

The excerpts shown in Table 1 are examples of the main ideas discussed by participants with respect to each code. The quotations shown were chosen based on their relevance and clarity, to exemplify the main ideas shared by different stakeholder groups and the ideas shared by most participants from one specific group.

Activities

The ‘Activities’ theme corresponds to the specific activities and actions currently being developed in the field of patient involvement that participants have either helped organize or in which they have been invited to participate as well as their perceptions of those activities.

The high-level concepts that pertain to the Activities theme are Surveys and Questionnaires, Benefit-Risk Assessment, Board and High-Level Representation, Collaborations and Role Models, Committees and Councils, Data Collection, Decision-Making Process, Design of Educational Material and Communications Review, Educational Programs, Expert Meetings, Focus Groups, Project Development, Public Hearings and Seminars, Conferences and Meetings.

The five high-level concepts pertaining to ‘Activities’ that were mentioned most frequently overall were Seminars, Conferences and Meetings, Design of Educational Materials and Communications Review, Committees and Councils, Public Hearings, and Collaborations or Role Models.

Analyzing the results from a stakeholder perspective, the concepts that were mentioned across all groups and levels were Public Hearings, Educational Programs and Expert Meetings. It is important to note that Seminars, Conferences and Meetings was mentioned by all stakeholder groups but only at the national level. Committees and Councils and Collaborations or Role Models were mentioned by nearly all the groups, with the exception of the marketing authorization holders. Design of Educational Materials and Communications Review was not mentioned by patient representatives at any level.

With respect to the regulator representatives at the European level, the main high-level concepts discussed were Committees and Councils and Public Hearings, while at the national level, Educational Programs was the most frequently mentioned activity, followed by Public Hearings, Educational Programs and Collaborations or Role Models.

The main high-level concepts discussed by European-level patient representatives were Educational Programs, Public Hearings, Collaborations or Role Models and Committees and Councils. On the other hand, at the national level, the main topic discussed was Seminars, Conferences and Meetings, followed by Educational Programs and Collaborations and Role Models.

On the other hand, for the marketing authorization holder group, the high-level terms that were discussed most frequently were Design of Educational Materials and Communications Review and Educational Programs, followed by Seminars, Conferences and Meetings.

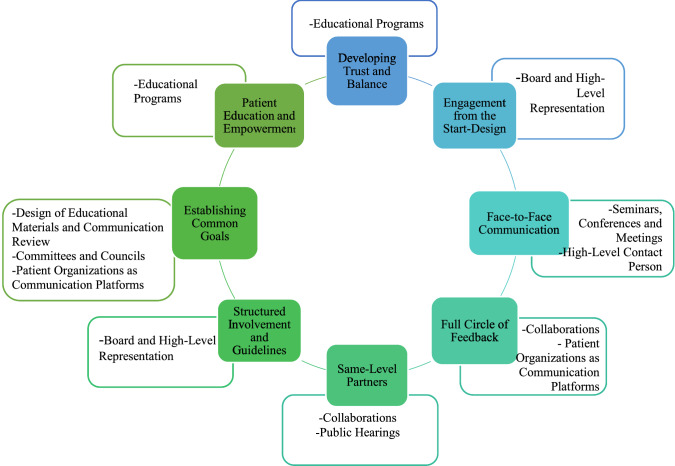

Best Practices and Activities

An illustration of the relationships between the Best Practices and Activities themes was created to showcase examples of possible activities that can help stakeholders implement the best practices identified (Fig. 2). The inner circle represents the best practices previously identified, while the outer boxes contain activities extracted from the Activities theme that relate to those practices.

Fig. 2.

Representation of the best practices in pharmacovigilance identified alongside the activities that relate to them

The high-level concepts that were highlighted with respect to the Best Practices theme were classified as such either because they were mentioned by the majority of the stakeholder groups or because the majority of participants from one specific group mentioned them.

Definition of Patient Involvement

Participants were asked to provide their own definitions of patient involvement based on their experience, with the aim of creating a general definition that included the viewpoints of different stakeholders and engagement levels throughout Europe. The ‘Definition of Patient Involvement’ theme corresponds to the ideas mentioned in this context.

Participants across all stakeholder groups mentioned the concept of “viewing the involvement of patients as partners who should be involved in the decision-making process to ensure that their needs are heard” as important in the definition of patient involvement.

Representatives from all groups mentioned the differences among regular patients, expert patients and patient organizations, and participants from the regulator and marketing authorization holder groups noted that “the targets for their patient involvement initiatives were mostly patient organizations or expert patients”.

Two participants from different stakeholder groups made a distinction between involvement and engagement, referring to engagement as “the real partnership, where patients are viewed as equals and not as a must-have in order to check a requirement box”.

Combining these aspects results in a definition for patient involvement as follows: “The placement of patients, ranging from individual patients to expert patients and irrespective of whether they belong to a patient organization, at the center of all actions that involve medicines as same-level partners in the decision-making process at all levels and stages of the life cycle of the product, which can extend from the development of policies and legislative changes to decisions regarding their own individual health”.

The main excerpts from the interviews are presented in Table 2. The extracts shown were chosen based on their relevance, and quotations regarding common ideas expressed by different stakeholders were chosen to exemplify the concepts (Table 3).

Table 2.

Excerpts extracted from the interviews and coded as part of the best practices theme

| Interview | Stakeholder group | Excerpt | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| SI08 | Patient representative | We have to educate the people; a lot of training is needed, so we have our own programs for patients to understand pharmacovigilance. We have to increase awareness of how the PV works and how patients can report, and that is why we participate in the European Awareness Week on PV and patient reporting, and I think we have to amplify this communication | Patient Education and Empowerment |

| SI12 | Neutral party | Now we see that patients who actually completed the EUPATI program have a foundation of knowledge that completely steps up their game in terms of the advice given, their understanding, and their contributions to the discussions; their general contributions to the system are huge | Patient Education and Empowerment |

| SI13 | Patient representative | Offer information, especially training in different areas like medicines, regulatory and approval processes of drugs and how they follow them up, so that when the patient has the opportunity to participate, they have a good level of base knowledge of the topics in the discussion | Patient Education and Empowerment |

| SI19 | Marketing authorization holder | When patients are well informed, they make good decisions, and I would say that the more educated, the better | Patient Education and Empowerment |

| SI04 | Regulator | Every activity we have done, we have tested with patients; the Patient and Consumer Working Party (PCWP is instrumental in things like the public hearings. They were working with us when we designed how we would do it, how long they would be, how long each speaker would have, how we should lay down the audience, everything we did with them, everything we have done, we have always done it by consulting with the patients | Engagement from the Start-Design |

| SI11 | Regulator | We have 2 years of doing these patient seminars with the patient organizations; we have a program or a group with representatives from the patient organization with whom we sit down and consider what kind of agenda, what kind of topics would they like to hear about; we have a full day of speakers, and they can come with their issues | Engagement from the Start-Design |

| SI17 | Marketing authorization holder | It is important to have a long-term partnership so that when you are talking about real collaboration, real partnership and long-term, it is really not at the end and you just say "is this ok for you or not?" but rather having the people involved from the start | Engagement from the Start-Design |

| SI01 | Patient representative | There should be laws, there should be policies, there should be practice guidelines, there should be standards showing how these patients should be involved in the regulatory and pharmacovigilance system and how they relate to other stakeholders, almost like a framework like the one WHO has, so that everyone is clear about what is expected from them, what are their obligations, what are their rights | Structured Involvement and Guidelines |

| SI04 | Marketing authorization holder | I think is important moving forward now to have this guidance like the one that the FDA has, like global guidance on patient engagement, how to involve patients throughout the whole life cycle of the medicine | Structured Involvement and Guidelines |

| SI12 | Neutral party | There were initiatives like, for example, PARADIGM* and others that really gave a structured identity and structured way of involving patients, how can it be done and the conditions to do it. That really encourages organizations to do it more proactively | Structured Involvement and Guidelines |

| SI03 | Regulator | What we are currently doing is complementing the generic framework, because that framework is for any kind of engagement we have in relation to medicine, but for pharmacovigilance we don't have a specific one, so we want to complement what we have with a document on points to consider, and that would be tailored to specific risk scenarios, to see how we can engage in those | Structured Involvement and Guidelines |

| SI04 | Marketing authorization holder | They have this valuable information that is needed to do a proper follow-up for any medicine that is on the market, so I think things have changed over the years, and it is not just that patients should just be passive acceptors of medicine and treatments, but they have now evolved to be collaborators with us | Patients as Same-Level Partners |

| SI06 | Patient representative | My dream is that patients are just one of the stakeholders, they are viewed as just one of the stakeholders, so you have the pharmaceutical companies for the development of new medicines, regulatory agencies for regulation, but in that list you also have the patients in the same position, and they are really seen as one of them. For now, I think it is not the case; we have to fight for the position of the patients, and in the future I hope that will not be necessary anymore | Patients as Same-Level Partners |

| SI03 | Regulator | The role of the patient has changed over the years and is no longer just the person with an illness that receives treatment from a sort of higher authority from the medical system; it is increasingly becoming and has been defined as a partnership and shared decision-making | Patients as Same-Level Partners |

| SI12 | Neutral party | Real-time interactions like a meeting are a sign of respect somehow, because otherwise, with a survey, it might look a little bit more transactional, and you can have written feedback afterward, of course, to use it in your research, but I think if you really want to partner with patients, it is more important to have a meeting | Face-to-Face Communication |

| SI10 | Patient representative | There is just something to be said for face-to-face interaction; it is the most powerful, it is a force of nature, you must listen to me while I am speaking. An email, an online platform, you can ignore it, but with face-to-face interaction, you can't, so nothing beats it | Face-to-Face Communication |

| SI13 | Patient representative | I have always thought that having someone there whom you can ask a question face-to-face, either by videocall or a physical channel, and seeing someone there at the other side makes communication easier, gives you trust and the security to know who is answering you | Face-to-Face Communication |

| SI06 | Patient representative | I would like to know what is going to be done with my feedback email, or when they have had many emails, they say "Okay, we are going to talk about it, and in about a month we will give you back feedback from us, and we can give you the negative points and the positive points and what can we do better in the future," which would trigger me to send another email in the future | Full Circle of Feedback |

| SI07 | Patient representative | Sometimes we just hear people and don't hear the results of their hearings or meetings, and so people afterward feel they weren't heard; they never know exactly what was done with their opinions and with their work, so it is really important to have the full circle of patient involvement in the process, to give them the full feedback | Full Circle of Feedback |

| SI08 | Patient representative | I think that probably the best way that pharmacovigilance could progress is when regulators and patient organizations, for example, have some research questions and work together on how to respond to those questions. I think that the ultimate goal of pharmacovigilance and patient engagement would be direct-to-patient PV, that whenever a questions arises, we join together and discuss how we can respond to those questions | Establishing Common Goals |

| SI14 | Regulator | That your goal and the goals of the patients are aligned or clear between both of those parties, and they can be accomplished together so that it is meaningful and impactful and can have value for patients and public health | Establishing Common Goals |

| SI05 | Patient representative | In one of the committees I work with, there is really an equilibrium, and we discuss what is going wrong, and they accept a lot. And in the other group, there are a lot of doctors, and I am the only patient … and they have real difficulties accepting the opinion of a patient; they are too far away from the patients, and I am sitting there and playing my role a little bit to see that they don't make something that is impossible for patients, but I don't bring a lot of news because I don't feel good in this group | Developing Trust and Balance |

| SI14 | Regulator | In my role, I would pretty much be keeping in touch and building those relationships over time, and it does take a while to foster that change and for them to feel comfortable, to have that free interaction, I guess, because the patients and the organization need to feel that | Developing Trust and Balance |

| SI10 | Patient representative | It is intimidating to see someone on the other side, because all of you look like doctors and politicians in our eyes, and patients get intimidated or scared, maybe, not to say what you guys want to hear | Developing Trust and Balance |

PV pharmacovigilance

Table 3.

Excerpts extracted from the interviews and coded as part of the patient involvement definition theme

| Interview | Stakeholder group | Excerpt | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| SI17 | Marketing authorization holder | We see it as a direct and constructive interaction with the patient during the entire life cycle of the medicine | Life Cycle of the Product |

| SI04 | Regulator | It is not just that patients should just be passive acceptors of medicine and treatments, but they have now evolved to be collaborators with us | Active Involvement |

| SI19 | Marketing authorization holder | I want to be active in making decisions about the medications I receive. So, for me, patient involvement is participating in everything, through every phase of the life cycle of the medicine where a patient can contribute to a decision | Life Cycle of the Product |

| SI01 | Patient representative | It is very important now that we differentiate the expert patient from the regular patient. Expert patients will engage in higher patient engagement | Definition of Patient Involvement |

| SI02 | Regulator |

There is always an important difference in the definitions of patients because, of course, you can look at the individual patients who are using medicines On the other hand, the representatives of the patient community who can provide a more collective perspective on a certain patient group, so when I am talking about patient involvement, also in pharmacovigilance, I like to focus on the representative |

Definition of Patient Involvement |

| SI12 | Neutral party | Patient involvement or patient engagement would be the act of purposively placing the patient not only in the center but in the front of the drug life cycle to make sure that patient representatives are able to give input regarding what they believe is more correct so that we are not making assumptions about what patients want but asking patients and patient representatives what they want and need | Life Cycle of the Product |

| SI03 | Regulator | The role of the patient is changing to be not just the person with an illness who receives treatment from a sort of higher authority; it is increasingly becoming and has been defined as a partnership and shared decision-making | Definition of Patient Involvement |

| SI01 | Patient representative |

Patient engagement is now a robust spectrum It can mean, at the top, someone who is out there to change the institutional policy, legislative practice and framework of global health; then, there are others who want to be national advocates, so they will be talking about their own countries’ health systems; and finally the patient advocate, who is attached to a general practitioner in primary health care, who is responsible only for their own health |

Definition of Patient Involvement |

| SI04 | Regulator | We say more engagement because it is really a two-way process | Definition of Patient Involvement |

| SI10 | Patient representative |

Patient involvement is where we are involving a patient in some way, shape or form to check a box. Patient engagement is where we actually engage the patients to allow them to actively participate, be part of maybe ideas or brainstorming or maybe even taking part in the decision about what needs to happen |

Definition of Patient Involvement |

Discussion

The factors contributing to best practices for patient involvement that we drew from the interviews were Developing Trust and Balance, Engagement from the Start-Design, Face-to-Face Communication, Same-Level Partners, Structured Involvement and Guidelines, Establishing Common Goals, Patient Education and Empowerment, and Full Circle of Feedback. For these concepts, activities were mentioned with respect to the task of putting them into practice.

Our work builds on previous work, such as the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI)-funded PARADIGM, which aimed to develop a comprehensive set of tools and practices to support the integration of patient perspectives into the development life cycle of medicine and to design a roadmap to support systematic change in stakeholder organizations to make patient engagement a common practice [33]. In our study, we focused on the postmarketing phase of the drug life cycle in Europe.

It is important to examine the differences in the best practices and activities that were discussed by different stakeholder groups. Patients at the national level described the notions of a Full Circle of Feedback, Developing Trust and Balance and Face-to-Face Communication as important, but this importance was not reflected by other groups given that Face-to-Face Communication and Developing Trust and Balance were not mentioned by either the marketing authorization holder representatives or the regulators at the European level. This discrepancy creates room for improvement for other stakeholders by allowing them to consider important factors that can facilitate patients in engaging in actions that are meaningful and relevant to them.

With respect to the Activities theme, both the marketing authorization holder and regulator groups mentioned the involvement of patients in the Design of Educational Materials and Communications Review; however, this activity was not mentioned by the patient representative group at either level, which raises the questions of whether patients considered this activity to constitute real engagement and whether they felt that by helping in the design of material, their voice would be heard and would have an impact on their lives.

However, previous studies focusing on patient organizations in Europe have highlighted the design of educational materials as one of the activities in which these organizations participate [4]. Such organizations focus on this activity mainly to inform patients about relevant topics, not merely including topics related to drug safety but also those pertaining to the disease itself; for example, the French Association of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia developed a patient-friendly knowledge base with resources related to drug information and drug safety that featured the use of several educational tools, such as videos [3].

On the other hand, national patient representatives emphasized Seminars, Conferences and Meetings as being the activities in which they participated or that they organized most frequently. Other stakeholder groups also mentioned this subject but only at the national level, indicating that this sort of activity is not of particular interest at the European level but might be a way of allowing national-level organizations to feel involved with European stakeholders, given that patients noted that more extensive and high-level initiatives can feel distant and irrelevant to their own participation.

All stakeholders agreed regarding the importance of Patient Education and Empowerment as a first step for taking more meaningful actions and achieving better outcomes from them. This conclusion supports the findings of previous studies that have highlighted education as the first step that is necessary for patient organizations to promote patient safety and PV [4].

The activity Public Hearings proved to be important for patients at both the European and national levels and was one of the activities that was mentioned by all stakeholders. Bahri et al. [34] analyzed stakeholder input at a public hearing and a dedicated meeting for the 2017–2018 EU procedure regarding valproate teratogenicity and designed proposals for enhancing engagement in risk minimization measures at the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC). The European Medicines Agency (EMA) committee is responsible for assessing and monitoring the safety of human medicines. The ideas of these authors for enhancing dialog among regulators, patients and HCPs are in accordance with the concepts uncovered in our study.

As stated previously, there is no clear definition of 'patient involvement', and this term is used interchangeably with others, such as engagement and participation [12]. We developed a definition of patient involvement for the context of this study to identify a standard term that is shared across stakeholder groups. The definition proposed is based on the perceptions of these participants and cannot be generalized; however, efforts are being made by other investigators to develop a complete and definitive definition of the concept of patient involvement. Brown and Bahri have already proposed a regulatory framework for patient involvement that could serve as the first steps taken toward the creation of a structure that could be applied in the regulatory field; they also proposed a widely applicable conceptual framework [12].

This study suggests a set of concepts and activities regarding best practices in Europe that can be implemented by organizations that want to develop better and closer relationships with patients. The results of this study relate to the work currently being carried out by the CIOMS XI group with respect to ‘Patient Involvement Global Guidance’ [35], which will also be of use in countries that have not yet had as much experience with patient involvement in the context of PV as countries in Europe. Other efforts are being made to create a more structured and systemized way of engaging patients in PV, such as the decision guide recently developed for regulators with respect to the selection of mechanisms for engagement with patients and HCPs [21].

In addition to patients with (chronic) illnesses, it is important to include the general public as a stakeholder in this context. Such inclusion is particularly important, for example, in the context of preventive interventions such as vaccines. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the challenges in global health more than ever before in terms of vaccine hesitancy and the risk of misinformation [36, 37]. The pandemic highlighted the need to ensure the engagement of the public both from inception and throughout the life cycle of a medicinal product (whether preventive or therapeutic). The EMA has for instance held public stakeholder meetings regarding the development, authorization, safety, and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in the EU [38]. Future studies should highlight the best ways of informing and involving the general public in this context, both at the EU and national levels and with respect to different stakeholder groups.

Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is the involvement of three important stakeholder groups relevant to PV that provided different perspectives on patient involvement based on their roles and responsibilities within their organizations. In addition, a structured and detailed methodology was employed in all the various steps of this study, a rigorous coding process was used, and the COREQ quality guidelines were observed. Together, these quality marks add transparency and robustness to the findings of this study.

This study focused on a European environment, which implies an important limitation of the study since its findings might not be applicable globally. Furthermore, the use of participants who are part of a European or multinational organization as a sample may not reflect the perspectives and initiatives of their organizations at a national level.

We employed a purposive sampling technique, and such sampling might have led to bias due to only colleagues who were interested in or had a positive perspective regarding patient involvement participating in the study. Another limitation is that although our sample included good representation of the pharmaceutical industry, it took a great deal more effort and snowballing to reach industry colleagues who felt they could contribute to the topic of our research. Furthermore, no European-level representation of the pharmaceutical industry was available to participate. Finally, it is important to note that not every participant was able to express themselves proficiently in English; accordingly, it is always possible for participant bias to affect the interviews.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed a definition for patient involvement based on qualitative interviews. The factors contributing to best practices for patient involvement highlighted by this study were mentioned across stakeholder groups and aimed to stimulate patient involvement in PV. Patients noted that there is still a great deal of room for improvement; one area in which patients were eager to see improvement was the perceptions that other stakeholders have of patients, i.e., with respect to allowing patients to become equal partners and be recognized as experts regarding their disease and the ways in which they deal with that disease. Patients mentioned their desire to experience a natural form of involvement similar to the effortless presence of other stakeholders.

Future research should be conducted to evaluate the progress of patient integration with respect to improving drug safety. Specific activities should be developed to implement the best practices outlined in this study. The creation of guidelines that provide structure is an important point to investigate in future studies, as is the creation of new feedback channels that satisfy patients’ desires in terms of directness and face-to-face communication, which can allow such communication to become a full circle in which patients are constantly informed of what is being done with their input.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Funding

No external funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest

Monica van Hoof, Katherine Chinchilla, Linda Härmark, Cristiano Matos, Pedro Inácio, and Florence van Hunsel declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

If a study in The Netherlands is subject to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO), it must undergo a review by an accredited Medical Research Ethics Committee or the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO). This study does not fall under the WMO act. Participants in the study provided a written statement of consent to participate prior to participating in the study.

Consent for publication

Participants in the study provided a written statement of consent to allow their data to be used for the purpose of this research and for publication of the study results, prior to participating in the study.

Availability of data and material

The dataset (consisting of interview transcripts and NVIVO® analysis files) used for this manuscript is not publicly available because of the data protection policy of Lareb. Requests to access the dataset should be directed to the first author and will be granted upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the first author and will be granted upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

The original study protocol was designed by all authors and the interviews were conducted by MvH. Data analysis was conducted by MvH, KC and FvH. The design of the manuscript was developed by all authors, and all authors contributed to the final data analysis and drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version for publication and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Hunsel FV, Härmark L, Rolfes L. Fifteen years of patient reporting—what have we learned and where are we heading to? Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2019;18(6):477–484. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2019.1613373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Härmark L, Weits G, Meijer R, Santoro F, Norén GN, van Hunsel F. Communicating adverse drug reaction insights through patient organizations: experiences from a pilot study in the Netherlands. Drug Saf. 2020;43(8):745–749. doi: 10.1007/s40264-020-00932-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daban M, Lacroix C, Micallef J. Patients' organizations in rare diseases and involvement in drug information: illustrations with LMC France, the French Association of Chronic Myeloid leukemia. Therapie. 2020;75(2):221–224. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2020.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chinchilla K, Matos C, Hall V, van Hunsel F. Patient organizations' barriers in pharmacovigilance and strategies to stimulate their participation. Drug Saf. 2021;44(2):181–191. doi: 10.1007/s40264-020-00999-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogt EM. Effective communication of drug safety information to patients and the public: a new look. Drug Saf. 2002;25(5):313–321. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200225050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cordier JF. The expert patient: towards a novel definition. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(4):853–857. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00027414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulet LP. The expert patient and chronic respiratory diseases. Can Respir J. 2016;2016:9454506. doi: 10.1155/2016/9454506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kant A, van Hunsel F, van Puijenbroek E. Numbers of spontaneous reports: how to use and interpret? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(3):1365–1368. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michaels DL, Lamberti MJ, Peña Y, Kunz BL, Getz K. Assessing biopharmaceutical company experience with patient-centric initiatives. Clin Ther. 2019;41(8):1427–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson A, Getz KA. Insights and best practices for planning and implementing patient advisory boards. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2018;52(4):469–473. doi: 10.1177/2168479017720475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inácio P, Cavaco A, Airaksinen M. The value of patient reporting to the pharmacovigilance system: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(2):227–246. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown P, Bahri P. 'Engagement' of patients and healthcare professionals in regulatory pharmacovigilance: establishing a conceptual and methodological framework. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;75(9):1181–1192. doi: 10.1007/s00228-019-02705-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vahdat S, Hamzehgardeshi L, Hessam S, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Patient involvement in health care decision making: a review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014 doi: 10.5812/ircmj.12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Härmark L, van Grootheest AC. Pharmacovigilance: methods, recent developments and future perspectives. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(8):743–752. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longtin Y, Sax H, Leape LL, Sheridan SE, Donaldson L, Pittet D. Patient participation: current knowledge and applicability to patient safety. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):53–62. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Health Council. The National Health Council rubric to capture the patient voice: a guide to incorporating the patient voice into the health ecosystem. National Health Council; 2019.

- 17.European Medicines Agency. Summary of the EMA public hearing on valproate in pregnancy. European Medicines Agency; 2017.

- 18.Phipps DL, Giles S, Lewis PJ, Marsden KS, Salema N, Jeffries M, et al. Mindful organizing in patients' contributions to primary care medication safety. Health Expect. 2018;21(6):964–972. doi: 10.1111/hex.12689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourke A, Dixon WG, Roddam A, Lin KJ, Hall GC, Curtis JR, et al. Incorporating patient generated health data into pharmacoepidemiological research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020;29(12):1540–1549. doi: 10.1002/pds.5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee AK, Okun S, Edwards IR, Wicks P, Smith MY, Mayall SJ, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in safety event reporting: PROSPER Consortium guidance. Drug Saf. 2013;36(12):1129–1149. doi: 10.1007/s40264-013-0113-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bahri P, Pariente A. Systematising pharmacovigilance engagement of patients, healthcare professionals and regulators: a practical decision guide derived from the international risk governance framework for engagement events and discourse. Drug Saf. 2021;44(11):1193–1208. doi: 10.1007/s40264-021-01111-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). OJ L;119:1–88 (2016).

- 26.Ando H, Cousins R, Young C. Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: development and refinement of a codebook. Compr Psychol. 2014 doi: 10.2466/03.Cp.3.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114523. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bazeley P, Richards L. The NVIVO qualitative project book. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skjott Linneberg M, Korsgaard S. Coding qualitative data: a synthesis guiding the novice. Qual Res J. 2019;19(3):259–270. doi: 10.1108/QRJ-12-2018-0012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutton J, Austin Z. Qualitative research: data collection, analysis, and management. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(3):226–231. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v68i3.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministerie van Volksgezondheid Welzijn & Sport. Uw onderzoek: WMO-plichtig of niet?—Onderzoekers—Centrale Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek. Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport; 2018. Available at: https://www.ccmo.nl/onderzoekers/wet-en-regelgeving-voor-medisch-wetenschappelijk-onderzoek/uw-onderzoek-wmo-plichtig-of-niet. Accessed 6 Jan 2021.

- 32.Ignatow G, Mihalcea R. Text mining: a guidebook for the social sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavaller-Bellaubi M, Faulkner SD, Teixeira B, Boudes M, Molero E, Brooke N, et al. Sustaining meaningful patient engagement across the lifecycle of medicines: a roadmap for action. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2021;55(5):936–953. doi: 10.1007/s43441-021-00282-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahri P, Morales DR, Inoubli A, Dogné JM, Straus S. Proposals for engaging patients and healthcare professionals in risk minimisation from an analysis of stakeholder input to the EU valproate assessment using the novel Analysing Stakeholder Safety Engagement Tool (ASSET) Drug Saf. 2021;2:1179–1942. doi: 10.1007/s40264-020-01005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.CIOMS. Working Group XI—patient involvement. 2020. Available at: https://cioms.ch/working-groups/working-group-xi-patient-involvement/#:~:text=The%20CIOMS%20Working%20Group%20XI,and%20the%20World%20Medical%20Association. Accessed 13 July 2022.

- 36.Hou Z, Tong Y, Du F, Lu L, Zhao S, Yu K, et al. Assessing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, confidence, and public engagement: a global social listening study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(6):e27632. doi: 10.2196/27632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rubinelli S, Purnat TD, Wilhelm E, Traicoff D, Namageyo-Funa A, Thomson A, et al. WHO competency framework for health authorities and institutions to manage infodemics: its development and features. Hum Resour Health. 2022;20(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12960-022-00733-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Medicines Agency. Public stakeholder meeting: development and authorisation of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines in the EU. European Medicines Agency; 2020. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/events/public-stakeholder-meeting-development-authorisation-safe-effective-covid-19-vaccines-eu.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.