Abstract

Agrobacterium tumefaciens transfers T-DNA to plant cells, where it integrates into the genome, a property that is ensured by bacterial proteins VirD2 and VirE2. Under natural conditions, the protein MobA mobilizes its encoding plasmid, RSF1010, between different bacteria. A detailed analysis of MobA-mediated DNA mobilization by Agrobacterium to plants was performed. We compared the ability of MobA to transfer DNA and integrate it into the plant genome to that of pilot protein VirD2. MobA was found to be about 100-fold less efficient than VirD2 in conducting the DNA from the pTi plasmid to the plant cell nucleus. However, interestingly, DNAs transferred by the two proteins were integrated into the plant cell genome with similar efficiencies. In contrast, most of the integrated DNA copies transferred from a MobA-containing strain were truncated at the 5′ end. Isolation and analysis of the most conserved 5′ ends revealed patterns which resulted from the illegitimate integration of one transferred DNA within another. These complex integration patterns indicate a specific deficiency in MobA. The data conform to a model according to which efficiency of T-DNA integration is determined by plant enzymes and integrity is determined by bacterial proteins.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens evolved to perform a sophisticated version of bacterial conjugation with a plant cell. The mobilized DNA is a segment of the bacterium’s 200-kb Ti (tumor-inducing) plasmid. This DNA (T-DNA, transferred DNA) is delimited by two 25-bp sites called the left and right borders. Upon induction by a wounded plant cell, the T-DNA is transferred to the plant cell nucleus and integrated into the genome. The production and transfer of the T-strand are mediated by the bacterial virulence proteins (Vir proteins; reviewed in references 15, 29, 33, 37, 41, and 46). VirD2, in conjunction with VirD1, nicks the bottom strand and attaches itself covalently to the 5′ end of the single-stranded T-DNA. The resulting T-strand is released from the Ti plasmid and is then transferred to the plant cell.

Once the T-DNA is in the plant cell, its nuclear import is ensured by the attached VirD2 protein, which contains the required NLSs (nuclear localization sequences) for interaction with the import machinery (16, 32, 43). The single-stranded DNA binding protein VirE2, also accompanying the T-strand in the plant cell, has been shown to be important for protecting the T-DNA from nucleolytic attack (31) and may also facilitate its translocation through the nuclear pore (33, 37).

Transformation experiments using an Agrobacterium strain mutated at a particular amino acid in VirD2 revealed that the integrated T-DNA molecules were truncated at the 5′ end. This suggested that wild-type VirD2 plays a role in conserving the 5′ end of the T-DNA intact until it is delivered to the plant chromosome (42, 44). Since T-DNA integration efficiencies were not affected by the mutation, we proposed that VirD2 was not conducting the ligation reaction. Thus, the plant machinery would carry out the steps leading to the integration of the T-DNA into the genome.

Agrobacterium was shown to enable the transfer of broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010 to plants (7). This plasmid’s promiscuous behavior in bacterial conjugation, which is due to its ability to use many different transfer systems for its mobilization (reviewed in reference 11), may explain why RSF1010 can be transferred from Agrobacterium to plants. Indeed, transfer of RSF1010 to plants was shown to depend on the components of the T-DNA transfer machinery (3, 7, 12). Extensive in vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated that RSF1010 encodes all of the proteins necessary for its own processing (2). MobA, in conjunction with MobB and MobC, performs the nicking of the plasmid specifically at the OriT (origin of transfer) cleavage site and subsequently binds to the free 5′ end of the DNA strand to be transferred. The OriT site recognized by the MobA protein consists of 38 bp of DNA (5); the nick itself has been mapped within the OriT, between positions 3138 and 3139 in the published RSF1010 sequence (35). Transfer was shown to be linear and unidirectional (18).

It is interesting that MobA-mediated transformation of plant cells occurs since MobA shares only a little sequence homology with VirD2 (18% identity, Fig. 1) and cannot be suspected to have evolved any feature specific for the process in a plant cell.

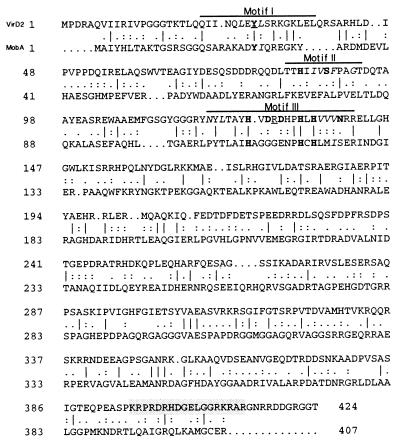

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of the VirD2 and MobA proteins encoded by plasmids pTiA6 and RSF1010, respectively. This alignment reveals 18% identity and 40% similarity between the two proteins. Motifs I, II, and III correspond to the conserved domains characterizing members of the relaxase family to which VirD2 belongs (27). Boldface letters indicate identical amino acids found in all of the analyzed proteins from this family; italics symbolize amino acids preserved in at least 50% of the cases. Y29 (underlined) of motif I of VirD2 was shown to be involved in the phosphotyrosine bond establishing the liaison with the T-strand (27). R129 (underlined) of motif III was replaced in a previous work with glycine (44; see Discussion). The shaded area corresponds to the bipartite functional nuclear localization signal from VirD2. Note that the NLS and motifs I, II, and III are not, or poorly, conserved in MobA.

Among the key questions that remain unanswered in the process of Agrobacterium-plant cell transformation is: how specific do the interactions between proteins accompanying the T-DNA and plant cell components have to be? To answer this question, we compared the transfer from MobA- or VirD2-containing agrobacteria to plants, as well as the efficiency and precision of integration into the plant DNA. Analysis of the performance of MobA in the plant cell during transformation was found here to be less efficient and less precise than that of VirD2. This allowed conclusions about the activities of VirD2 originally adapted to perform transformation of plant cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and media.

Strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. Bacterial and plant media were prepared as previously described (24, 34).

TABLE 1.

Agrobacterium strains and plasmids used in this study

| Agrobacterium strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| ATvir | GV3101(ppPM6000); pPM6000 is a disarmed Ti plasmid with an intact virulence region | 4 |

| ATvirΔD2 | Same as ATvir but with a precise nonpolar total deletion of the virD2 gene | 6 |

| ATvirΔE2 | GV3101(pPM6000E); same as ATvir but with a precise nonpolar deletion of the virE2 gene | 31 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTd33 | Binary plasmid carrying bacterial resistance to gentamicin; the T-DNA carries the uidA and nptII genes under control of plant regulatory sequences | 44 |

| pTd73 | Same as pTd33, except that the right border of the T-DNA and the overdrive have been replaced with the OriT sequence of plasmid RSF1010 | This work |

| pMob | pKT231; RSF1010-derived plasmid; carries the genes encoding mobilization proteins MobA, MobB, and MobC; also carries bacterial genes conferring resistance to kanamycin and streptomycin | 1 |

Binary plasmids.

pTd33 is a binary vector carrying the marker genes uidA and nptII on its T-DNA (Fig. 2) (44). pTd33 contains an XbaI site, located 34 bp from the border nicking site, which can be used to analyze the integrity of the integrated DNAs at their 5′ ends. Plasmid pTd73 is a derivative of pTd33 in which the overdrive and the right border sequence were precisely replaced with the OriT sequence of RSF1010 (Fig. 2). For this purpose, primer pr1 (Table 2), containing the OriT sequence of RSF1010 (Fig. 2B), was used in combination with primer pr2 to amplify a 2-kb fragment of pTd33. After sequence analysis confirming the presence of the OriT nick site, the NotI-KpnI fragment was used to replace the corresponding fragment in plasmid pTd33, resulting in pTd73. The XbaI site is kept 34 nucleotides from the OriT nicking site, inside the R-DNA. Introduction of plasmids pTd33 and pTd73 into the Agrobacterium strains was performed by electroporation.

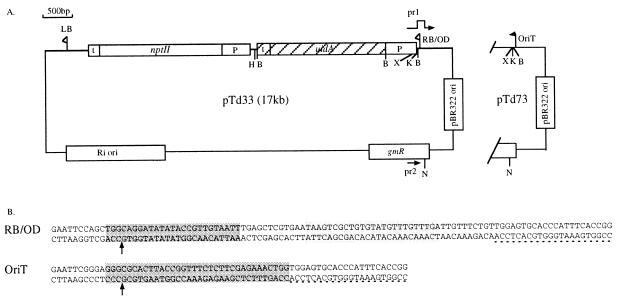

FIG. 2.

Binary plasmids pTd33 and pTd73. (A) Only the region of pTd73 that is different from plasmid pTd33 is shown, and its sequence is presented in panel B. pTd33 carries the right border (RB) and left border (LB), as well as the overdrive enhancer sequence (OD). In pTd73, primers pr1 and pr2 (see Table 2) were used to replace the right border and the overdrive with the OriT region. The flags representing the two borders delimit the T-DNA. P and t are the 35S promoter from CaMV and the terminators of the nopaline synthase gene, respectively. nptII codes for neomycin phosphotransferase (kanamycin resistance), and uidA codes for β-glucuronidase. pBR322 ori and Ri ori correspond to the origins of replication of Escherichia coli and Agrobacterium, respectively, and gmR is the gene conferring resistance to gentamicin. The underlined region of the T-DNA represents the region used as a probe for Southern analyses. H, B, N, and X are restriction sites for HindIII, EcoRI, BamHI, NotI, and XbaI, respectively. (B) Sequences of the nick regions (dark shaded box) of binary plasmids pTd33 and pTd73. Cleavage occurs on the bottom strand and is indicated by the arrow. The light shaded box contains the overdrive enhancer sequence.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | 5′→3′ sequence |

|---|---|

| OriT | |

| pr1 | CCCCGGGTACCGAGCTCGAATTCGGGAG |

| GGCGCACTTACCGGTTTCTCTTCGAGAA | |

| ACTGGTGGAGTGCACCCATTTCACCGG | |

| pr2 | CATCGCGCTTGCTGCCTTCGACCA |

| R-DNA | |

| RB1 | AGATAGCTGGGCAATGGAATCCG |

| RB2 | GAGGAGGTTTCCGGATATTACCC |

| RB3 | ACTGTTCGCCAGTCTTTACGGCG |

| RB4 | GGGTTTCTACAGGACGGATG |

| RB5 | ATTCCCCGGATCCGTCCATG |

| RB6 | CTCGGATTCCATTGCCCAGC |

| RB7 | AAGTCCATTGATGTGATATC |

Tobacco seedling transient expression and transformation assay.

We followed the protocol described in references 30 and 44. Briefly, 200 tobacco seedlings were cocultivated with the Agrobacterium strain be tested, which was diluted to an optical density of 0.6 at 600 nm. Half of the seedlings were used to measure the transient expression and the other half were used to measure the stable expression of the marker genes, uidA and nptII, respectively, carried by the T-DNA (17, 22, 25).

Analysis of the pattern of integration by PCR and by Southern blotting.

Plant DNA was extracted as previously described (28). A standard PCR protocol, using Ampli-Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) was applied to 0.5 to 1 mg of plant DNA mixed with the corresponding oligonucleotides (Table 2 and Results). Southern blot analysis was performed as previously described (34). Radioactive probes were made by using a random priming labeling kit (Boehringer-Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) and [α-32P]dATP (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom).

Isolation and analysis of the T-DNA–plant DNA junctions by TAIL-PCR.

Plant DNA from transformants was isolated in order to analyze the junction region between the 5′ end of the R-DNA and the adjacent plant DNA. The isolation of these border junctions was performed by thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR (TAIL-PCR) as previously described (21), except that primers RB1, RB2, and RB3 were used as R-DNA-specific primers. The fragments were isolated, purified, and cloned into the plasmid PCR2.1 (Invitrogen). Sequencing was performed by using δ-rhodamine terminators (Applied Biosystem), which were incorporated by using universal primers with a Gene-Amp PCR system (Perkin-Elmer). The analysis was performed with an ABI prim 377 automated DNA sequencer.

RESULTS

We engineered an Agrobacterium strain containing all of the necessary components to study MobA-mediated transformation of plants. To avoid any interference between the VirD2 and MobA proteins, we used strain ATvirΔD2 (6), which carries a complete and precise deletion of the virD2 gene. As a MobA protein source, the RSF1010 derivative pMob (pKT231; 1) was introduced into this Agrobacterium strain, giving ATvirΔD2 (pMob).

Construction of a binary plasmid for comparison of MobA- and VirD2-mediated transformations was based on plasmid pTd33 (Table 1). pTd73 was constructed by precisely replacing the sequence of pTd33 encompassing the right border and the overdrive with the 38 essential nucleotides from the OriT of RSF1010 (Fig. 2 and Materials and Methods). pTd33 and pTd73 thus differ only in their nicking sequences, which can be recognized and processed by VirD2 and MobA, respectively. Both plasmids carry the marker genes uidA (coding for β-glucuronidase) and nptII (conferring resistance to kanamycin) for monitoring of transfer and transformation events, respectively.

Transfer of the DNA to plant cells could not be detected from the resulting strain, ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd33), indicating that pTd33 itself does not contain any sequence which could serve as an alternative nicking site for the MobA endonuclease encoded by pMob. Since pTd73 differs in sequence from pTd33 only at the OriT nick site, any detectable transfer of pTd73 will be considered to result from a specific nick of the vector by MobA at this sequence.

pTd73 was then introduced into ATvirΔD2(pMob), giving strain ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd73). For the following sections, we define as R-DNA the molecule originating from plasmid pTd73 that is processed and transferred by MobA.

Transfer of R-DNA to the plant cell nucleus. (i) Transfer efficiency.

Strains ATvir(pTd33) and ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd73) were tested for efficiency of DNA transfer to young tobacco seedlings (30). In this assay, the activity of β-glucuronidase transiently expressed by the uidA gene carried on vectors pTd33 and pTd73 represents a quantitative measure of transferred DNA molecules which arrive in the plant cell nucleus without necessarily being integrated into the genome (transfer efficiency). Transient expression was evaluated 3 days after cocultivation with the respective strains by counting of the blue spots appearing on the seedlings after histochemical staining (see Materials and Methods). Table 3 shows that in the absence of VirD2, MobA transferred R-DNA molecules to plants with an efficiency between those corresponding to the dilution of strain ATvir(pTd33) to 1/250 to 1/100. A comparably low transfer efficiency of a virD2-containing bacterial strain ATvir(pMob/pTd73) was observed, demonstrating that DNA transfer mediated by MobA is neither dependent on nor inhibited by the presence of VirD2 (data not shown) and confirming earlier observations (36).

TABLE 3.

Efficiency of transfer, transformation, and integration of Agrobacterium strains containing VirD2 or MobA

| Inoculation ratioa | Efficiency of:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transferb

|

Transformationc

|

Integrationd

|

|||||||

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 3 | Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 3 | Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 3 | |

| 1/50 | —e | 3.27 | 3.5 | — | 0.16 | 0.2 | — | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| 1/100 | 2.62 | 2.25 | 2.7 | 1.26 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| 1/250 | 1.0 | 0.74 | 1.6 | 0.56 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.56 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| MobA | 1.8 | 1.13 | 2.5 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

1/100, 1/250, and 1/500 are the ATvir(pTd33)/ATvirΔD2(pTd33) ratios used to inoculate the seedlings. MobA corresponds to strain ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd73) used undiluted.

Spot/seedling ratio.

Callus/seedling ratio.

Transformation/transfer ratio.

—, not tested.

The R-DNA molecules reach the plant cell nucleus much less efficiently than do T-DNA molecules. Several aspects, from processing until nuclear entry, could be impaired during this transfer process. The competition for transfer with pMob plasmids present in the bacterium could also contribute to the low transfer efficiency.

(ii) Requirement for VirE2 in MobA-mediated transfer.

It was previously reported that the export of VirE2 proteins can be inhibited by the presence of RSF1010-derived plasmids in Agrobacterium, consequently leading to a decrease in transfer efficiency (3, 40). We investigated whether the low transfer efficiency mediated by MobA could be explained by a similar blocking effect of the RSF1010-derived plasmid present in strain ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd73).

First, we analyzed the dependence of MobA-mediated transfer on VirE2. Plasmids pMob and pTd73 were introduced into VirE2-deficient strain ATvirΔE2 (Table 1) (31), resulting in strain ATvirΔE2(pMob/pTd73). Transfer from this strain was not detected, while dilutions of a wild-type strain in which transfer is mediated by VirD2 indicated that we could have detected transfer values at least 3 orders of magnitude lower than those measured in the presence of VirE2. MobA-mediated transfer to plants therefore requires VirE2 to the same extent as the VirD2-mediated transfer.

Second, we tested whether the export of VirE2 was impaired in ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd33); the concentration of VirE2 protein delivered to the plant cell may not be sufficient to ensure proper transfer of the R-DNA. T-DNA transfer from a VirE2-defective strain has been reported to be complementable either by another VirE2-proficient Agrobacterium present during the cocultivation period (8, 26) or by a plant expressing the VirE2 protein (9). Both types of complementation assays were tested here to determine whether the VirE2 supply from transfer-proficient strain ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd73) was limiting for R-DNA transfer. Experiments were performed by using for the cocultivation a mixture of strain ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd73) and VirE2 donor strain ATvirΔD2, which lacks any transferable DNA. This gave rise to transfer values increased by an order of magnitude (Table 4, experiments 1 and 2), confirming that the concentration of VirE2 protein supplied by the transfer-proficient bacterium ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd73) was limiting. Similarly, a threefold increase in transfer efficiency was observed when tobacco plants transgenic for VirE2 were used in the cocultivation experiments (Table 4, experiments 3 and 4).

TABLE 4.

Dependence of MobA-mediated transfer on VirE2a

| Strain ratio | Transfer efficiency

|

VirE2+/VirE2− ratio

|

Transfer efficiency

|

VirE2+/VirE2− ratio

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilution strain: VirE2−

|

Dilution strain: VirE2+

|

Dilution strain: VirE2−

|

Dilution strain: VirE2−

|

|||||||||

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 3 | Expt 4 | Expt 3 | Expt 4 | Expt 3 | Expt 4 | |

| 1 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 7.6 | —b | 10.8 | NAc | — | — | — | — | NA | NA |

| 1/2 | 0.3 | 0.49 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 11.3 | 5.7 | — | — | — | — | NA | NA |

| 1/10 | — | 0.09 | — | 0.7 | NA | 7.8 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 3.9 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 3 |

| 1/50 | 0.01 | — | 0.15 | 0.1 | 15 | NA | 0.3 | 0.05 | 0.88 | 0.17 | 2.9 | 3.4 |

| 1/100 | — | — | 0.08 | — | NA | NA | — | — | 0.48 | 0.08 | NA | NA |

Four independent experiments were performed, in which either an Agrobacterium strain (experiments 1 and 2) or a plant transgenic for VirE2 (experiments 3 and 4) was used as a donor of VirE2 protein. Transfer efficiencies were measured in GUS spots and seedlings. 1/2, 1/10, 1/50, and 1/100 are the ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd73)/dilution strain ratios (above the columns of data used to make the dilutions for inoculation of the seedlings. For the control experiments without an additional VirE2 source (first two columns of data for experiments 1 and 2 and experiments 3 and 4), the strain with virE2 deleted (ATvirΔE2), represented by VirE2−, was used as the diluting Agrobacterium strain. For complementation experiments 1 and 2 (middle two columns), strain ATvirΔD2, represented by VirE2+, was used as the VirE2 source for the dilutions. In experiments 3 and 4, in which transgenic plants were used as the VirE2 source, the dilutions were performed with strain ATvirΔE2, in which virE2 is deleted. Efficiency of VirE2 complementation is presented (in the rightmost columns of paired data) as the ratio of transfer efficiencies obtained in the presence/absence of an additional VirE2 source (VirE2+/VirE2−).

—, not tested.

NA, not applicable.

(iii) Effect of the size of the transferred DNA.

We investigated whether the larger size of the R-DNA (17 kb) than the T-DNA of pTd33 (6 kb) was a handicap. pTd333, a derivative of pTd33 missing only the left border sequence, was constructed. The T-DNA in this plasmid consequently consisted of 17 kb containing only one nicking site (5a). Transfer of this plasmid from a VirD2-containing strain was found to be as efficient as that of pTd33 (data not shown). Furthermore, the transfer of T-DNA from a pTd333-containing strain was not significantly improved by the presence of either source of VirE2 during cocultivation (data not shown).

The low efficiency of R-DNA transfer is therefore partially due to the transfer of limited amounts of VirE2 molecules to the plant cell in the presence of plasmid pMob.

Integration into the plant genome. (i) Efficiency of integration.

The stable expression of the nptII gene, encoding the neomycin phosphotransferase protein, was used to select R-DNA integration events. The number of kanamycin-resistant calli per tested seedling was used as a measure of transformation (transformation efficiency). Integration efficiency is defined as the ratio of the number of kanamycin-resistant calli per seedling to the number of blue spots per seedling (i.e., the transformation efficiency over the transfer efficiency); it refers to the fraction of molecules integrated into the genome from the number of molecules that entered the nucleus. The relative transfer and transformation efficiencies observed for MobA strain ATvirΔD2(pMob/pTd73) were on the order of 1/250 to 1/100 of those of wild-type strain ATvir(pTd33). However, the calculated integration efficiencies of the two strains were very similar (Table 3). This indicated that the same proportion of transferred molecules integrated into the genome, irrespective of whether the pilot protein was VirD2 or MobA. The integration efficiency was independent of the dilution used in a given experiment, indicating the linearity of the assay, as was previously reported (44).

(ii) Analysis of the right R-DNA junctions after integration.

Since one of the main features of T-DNA transformation is the precision of insertion into the genome, analysis of the integrity of integrated DNA molecules has proven to be very informative about the function of the bacterial virulence proteins accompanying the T-DNA (6, 31, 44). The function of MobA in integration was therefore studied by analyzing the pattern of the integrated R-DNA. Because OriT is the only site on the vector which is recognized and nicked by the MobA protein (see above), it was expected that a linear R-DNA molecule transferred to the plant cell results from two successive cleavages of the OriT site, in which the second nick occurs only after the initially nicked OriT site has been restored by lagging-strand synthesis (see the nicking site in Fig. 2B). In other words, the OriT was expected to play the role of both the left and the right borders and the size of the transferred DNA was expected to correspond to that of 17-kb plasmid pTd73.

The structures at the 5′ end of the R-DNA after integration were analyzed by Southern blotting by using the XbaI site, located 34 nucleotides from the OriT nicking site inside the R-DNA, as a marker for the integrity of the 5′ end. The DNA from plants that showed a conserved 5′ end was subsequently subjected to TAIL-PCR (see Materials and Methods) for analysis of the junctions at the nucleotide level. The DNA from plants lacking a conserved XbaI site was tested by a classical PCR to determine the extent of the deletions.

DNA from nine independent transformants regenerated from kanamycin-resistant calli was digested with the restriction enzyme HindIII (which cuts only once in the plasmid, 3 kb from the right border inside the R-DNA, revealing the number of inserts per transformant) alone or in combination with XbaI (see above and Fig. 2). The DNA was then subjected to Southern blot analysis using a BamHI fragment spanning the uidA open reading frame as a probe (Fig. 2). Detection of a defined 3-kb band of the vector upon double digestion with restriction enzymes HindIII and XbaI was indicative of a relatively conserved 5′ end of either a T-DNA or an R-DNA after integration.

Using the TAIL-PCR technology (see Materials and Methods), we isolated and sequenced the R-DNA–recipient DNA junctions from the transformants which contained the most complete 5′ ends of the R-DNA. This was done by using three sets of nested primers to sequentially favor the amplification of specific bands corresponding to the junction area. Results of Southern blot and TAIL-PCR analyses, schematically represented in Fig. 3A, show that the different transformants can be grouped into several categories.

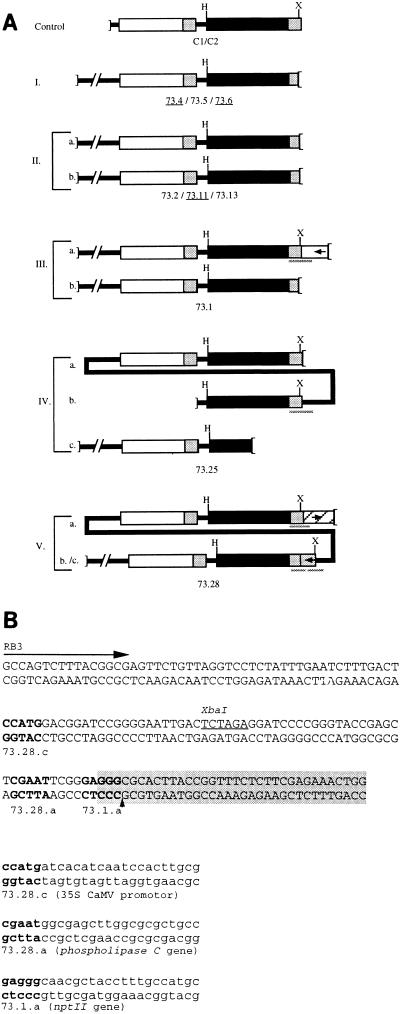

FIG. 3.

(A) Patterns of integrated R-DNA molecules. The dark box represents the uidA gene, the white box represents the nptII gene, the shaded area represents the 35S promoter from CaMV, and the hatched area represents the phospholipase C gene (see text). The arrows indicate the orientation of transcription in the regions were T-DNA integration took place. H and X are restriction sites for HindIII and XbaI. The plasmid DNA segment is shown as a bold line. Controls C1 and C2 represent two independent T-DNA transformants. Categories I to V are different patterns of R-DNA transformants. They carry either one insert (category I) or two separate inserts (categories II and III; a and b). The two transformants in categories IV and V carry two inserts each, of which one is a partial concatemer of plasmid pTd73 (a, b, and c, where a and c can be interchanged). The sequenced junctions (see text) are shown with a shaded line underneath. (B) Sequence analysis of R-DNA–plant DNA junctions isolated by TAIL-PCR. The original sequence around OriT (dark box; the nick site is represented by the arrowhead) of plasmid pTd73 is shown (uppercase letters), as well as the positions of the junctions sequenced from three transformants (boldface letters). Below, the three sequences in lowercase correspond to the junctions between R-DNA (boldface letters) and recipient DNA (lightface letters). The targeted site on the recipient DNA is in parenthesis. The junctions which were isolated but corresponded to the uncut OriT region of a concatemer of pTd73 are not shown. The last nested primer (RB3) used during the TAIL-PCR is indicated.

The patterns of DNA extracted from kanamycin-resistant plants obtained by VirD2-mediated transformation using strain ATvir(pTd33) were used as controls (C1 and C2). Digestion with HindIII showed that transformants 73.4, 73.5, and 73.6 have single inserts (category I). However, upon additional digestion with XbaI, their bands did not shift to the expected size of 3 kb, indicating that they have lost the 5′ extremity of the R-DNA. In the four transformants which contained two inserts, either both XbaI sites were lost (73.2, 73.11, 73.13; category II) or only one was conserved (73.1; category III). Remarkably, sequence analysis of the junction of transformant 73.1 revealed a perfect junction between the OriT nicking site and the recipient DNA, suggesting that the MobA–R-DNA bond has been used in this ligation process (IIIa; Fig. 3B). But, surprisingly, the molecular analysis of the DNA sequence fused to the OriT nicking site corresponded to the sequence of an nptII gene truncated at its 3′ end by the integration event, suggesting that this integration event occurred in another molecule of R-DNA.

PCR analysis was performed on plants from categories I and II by using a fixed primer, located 725 nucleotides from the MobA nicking site and facing it (primer RB4), in combination with three different primers 60, 300, and 500 nucleotides from the nicking site (primers RB5, RB6, and RB7, respectively; Table 2). The results indicated that the sizes of the deletions were always larger than 300 nucleotides and were between 300 and 500 nucleotides in three of the six plants analyzed.

In transformant 73.25 (category IV), two of the three inserts carried a preserved 5′ end (a and b). The third insert was part of a high-molecular-weight band only weakly hybridizing to the probe; it may be indicative of a partial deletion of the uidA gene. The fact that this fragment did not shift upon digestion with XbaI indicates that the truncation occurred at the 5′ end. The junction amplified by TAIL-PCR from this transformant revealed the presence of the complete OriT sequence of plasmid pTd73 (Fig. 3, IVb). This result indicates that plasmid pTd73 was transferred and integrated as a concatemer in this transformant. Such an event can be explained by a combination of rolling-circle DNA replication with lagging-strand synthesis, displacement and export from the bacterium of the R-DNA, and absence of a second cleavage at the restored OriT. We did not succeed in isolating junction IVa of this transformant.

In transformant 73.28 (Fig. 3A, category V), two bands were detected by Southern analysis while three different junctions were amplified by TAIL-PCR (a, b, and c). Insert a carried the XbaI site and a deletion of 15 nucleotides from the nicking site; insert b carried the XbaI site and corresponded to a concatemer carrying a complete OriT sequence. This fragment, identified by TAIL-PCR, was not detectable by Southern analysis because it most probably suffered from a severe deletion at the 3′ end of the uidA gene. Insert c lacked the XbaI site, as well as 60 nucleotides from the nicking site. Sequence analysis of junctions 73.28a and 73.28c suggested the integration of the R-DNA inside another R-DNA, since the sequence fused to the right extremity of each analyzed R-DNA was found to have a high degree of homology with a gene encoding a phospholipase C probably of bacterial origin (homology hit with the corresponding gene from Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and with a truncated 35S promoter from cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV), respectively. The simplest interpretation of these data is that the unprocessed border detected by the TAIL-PCR and the truncated 35S promoter belong to the same R-DNA molecule (Fig. 3A).

To summarize, these analyzes revealed that in 1 out of 15 integration events (monitored within nine plants), the nucleotide presumably attached to MobA was conserved. In three cases, the deletion is less than 60 nucleotides long, and in at least four cases (and in, at the most, seven cases, if we consider that in plants 73.1, 73.2, and 73.11 the longest insert would hinder the analysis of the shorter one by PCR), it extended to between 300 and 500 nucleotides from the nick site. In the remaining cases (seven or four cases [see above]), the deletion extended to more than 500 nucleotides. Using the right side of the R-DNA, we could only rescue three junctions, all corresponding to recombination events between two molecules of R-DNA: one event could have been MobA mediated, whereas the two others were probably MobA independent since they led to truncations of the right end of the transferred molecules.

DISCUSSION

There are interesting parallels between Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of plants and conjugal transfer of DNA between bacteria (20, 38, 39, 45). To analyze whether VirD2 evolved special functions allowing it to mediate integration of the T-DNA into the plant genome, we compared VirD2-mediated and MobA-mediated plant transformations.

Transfer of R-DNAs.

In our study, almost similar binary plasmids, differing only by 38 nucleotides at the nick site for the respective endonuclease, were used to compare the transfer efficiencies of MobA and VirD2. To avoid any competition, we measured the transfer of an OriT-containing plasmid mediated by MobA in a VirD2-free Agrobacterium strain and VirD2-mediated T-DNA transfer in a MobA-free Agrobacterium strain. MobA-dependent R-DNA transfer occurred with a much lower efficiency than VirD2-dependent T-DNA transfer (less than 1/100). This low transfer efficiency could reflect the impairment of any step, from processing in the bacteria to entry into the plant cell nucleus. Earlier reports on MobA-mediated transformation indicate that products from the RSF1010 plasmid could interfere with the export of the VirE2 protein from Agrobacterium (3, 40). Since our aim was to study the integration process and since VirE2 protein plays a crucial role in preserving the T-DNA’s integrity (31), we first investigated whether products from the RSF1010 derivative pMob could similarly inhibit the export of VirE2. Indeed an additional source of VirE2 protein was able to increase up to 10-fold the transfer of uidA-containing R-DNA strands from a strain already expressing VirE2, indicating that VirE2 export was limiting the transformation mediated by MobA. This competition between RSF1010 products and VirE2 suggests a high-affinity recognition of elements of the DNA export machinery by the MobA components and may be an important feature of broad-host-range plasmids since it would allow them to parasitize other DNA transfer systems efficiently.

Although the complementation by extracellular VirE2 allowed a significant (10-fold) increase in transfer efficiency, the transfer efficiency mediated by MobA under these conditions remained 1 order of magnitude lower than that mediated by VirD2. We did not attempt to identify other steps that could be affected during transfer of R-DNAs, but the lack of classical NLSs on MobA, necessary for efficient nuclear entry, probably contributes to the observed phenotype. However, the activity of a nonconsensus NLS cannot be excluded (Fig. 1). The presence of the plasmid pMob in the bacterium may also contribute to the low transfer efficiency measured for pT73, but it is not expected that transfer of pMob to plant cells would influence the integration efficiency, since this depends on the transfer and transformation efficiencies, which were measured with marker genes located only on pTd73.

Apart from nuclear targeting, it is possible that MobA-mediated T-DNA transfer is handicapped by the lack specific interactions with certain plant proteins involved in as yet unknown mechanisms (e.g., cyclophilins; 10).

Integration.

The efficiency of integration of R-DNA molecules was very similar to that measured for T-DNA, indicating that the R-DNA complex has integrative capacities similar to those of the T-DNA complex. However, analysis of the 5′-end integration patterns of R-DNAs revealed drastic differences between the two systems: while the 5′ end of the T-DNA is usually preserved up to the nucleotide attached to VirD2 (6, 13, 23, 31, 44), the 5′ ends of the integrated R-DNAs are deleted in the majority of the cases. This result suggests that MobA, unlike VirD2, is not “conceived” to release the attached nucleotide in order to favor a precise ligation between the R-DNA and the plant DNA.

These data are reminiscent of the properties of T-DNA integration mediated by a mutant form of VirD2, VirD2R129G (created by replacement of arginine 129 with glycine; 44); in both cases, the efficiency of integration is unaltered compared to the respective wild-type situation while the pattern of integration indicates deletions at the 5′ end. The independence of efficiency and precision of integration was used to suggest that the 3′ end of the T-DNA was affecting the first synapsis with the plant DNA (44). However, there is a clear difference between the integration mediated by this VirD2R129G mutant protein and that mediated by MobA. The junction isolated with the mutant protein never showed integration within another T-DNA molecule; the patterns of integration were clear and easy to analyze and could be mostly interpreted as single integration events. When R-DNA integration was analyzed, in the majority of the cases, at least two right-end junctions were identified per transformed plant. Furthermore, in the three cases in which it was possible to rescue and analyze these junctions, they showed integration events occurring inside another R-DNA molecule, indicating complicated recombination events.

It is difficult to interpret how, despite a low efficiency of transformation, the majority of the plants recovered after MobA-mediated transformation contain two distinct inserts and a complex pattern of integration. This phenomenon has never been observed under similar experimental conditions for VirD2- or VirD2R129G-mediated transformation, either in the presence or in the absence of VirE2 (6, 31, 44). Therefore, a specific defect of MobA in ligating the R-DNA to the recipient DNA would probably not be sufficient to explain the observed pattern of integration. Rather, this indicates that certain plant cells are far more competent than others for transformation by R-DNAs. Our hypothesis is that this competence is determined by the disruption of the nuclear envelope that accompanies mitosis. Under these conditions, several R-DNAs present in the cytoplasm can reach the genomic DNA simultaneously. The particular recombinogenic activity associated with the status of the dividing cells would then contribute to integration patterns. Our results therefore suggest that the presence of NLSs on VirD2 is also a determining factor in the pattern of integration of the T-DNA, a hypothesis which is being tested in our laboratory.

This hypothesis meets two other lines of evidence: firstly, the complexity of the T-DNA integration has already been reported to be very much dependent on the type of plant tissue used for transformation, suggesting variation from cell to cell in recombination behavior (14; but it has not been demonstrated that a higher complexity can be correlated to cell division). Secondly, complex types of integration patterns are encountered when trangenic plants are obtained by using direct gene transfer technologies (see reference 19 and references therein); in these cases, the transfected DNA is not associated with any nuclear localization signal and its access to the nuclear genome probably depends upon mitosis and disruption of the nuclear envelope.

The complexity of the R-DNA integration events observed does not allow extensive speculation about the mechanism taking place (e.g., whether there is extrachromosomal recombination and whether the recombination substrates are present in single- or double-stranded form). However, it remains interesting that in 1 integration event (among 15 analyzed), the nucleotide proposed to be attached to MobA is found correctly ligated to the “recipient” DNA. Although rare, this event indicates that MobA has the potential to release the phosphotyrosine bond involved in the linkage with the transferred DNA. Specifically for the ligation reaction, the two proteins VirD2 and MobA may indeed vary in the ability to expose the linkage bond.

Our detailed analysis of MobA’s “flaws” when substituting for VirD2 reinforces the qualities already attributed to VirD2. These properties have enabled Agrobacterium to ensure precise and efficient transformation of plants, making it a widely used instrument in the generation of transgenic plants. This and a plant tissue carrying a high generation capacity combined with a good generation susceptibility to transformation are the most important requirements for the successful generation of transgenic plants. However, quality control of integration events at the cellular level will probably represent one of the next challenges in transgenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Crouzet and J. Fütterer for stimulating discussions and advice and A. Zimienowicz and M. Hanin for critically reading the manuscript. F. Jasper and H. H. Steinbiss kindly provided the transgenic plants expressing VirE2, and M. Bagdasarian provided the plasmid pKT231.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bagdasarian M, Lurz R, Ruckert B, Franklin F C, Bagdasarian M M, Frey J, Timmis K N. Specific-purpose plasmid cloning vectors. II. Broad host range, high copy number, RSF1010-derived vectors, and a host-vector system for gene cloning in Pseudomonas. Gene. 1981;16:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharjee M K, Meyer R J. Specific binding of MobA, a plasmid-encoded protein involved in the initiation and termination of conjugal DNA transfer, to single-stranded oriT DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4563–4568. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.19.4563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binns A N, Beaupré C E, Dale E M. Inhibition of VirB-mediated transfer of diverse substrates from Agrobacterium tumefaciens by the IncQ plasmid RSF1010. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4890–4899. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4890-4899.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnard G, Tinland B, Paulus F, Szegedi E, Otten L. Nucleotide sequence, evolutionary origin and biological role of a rearranged cytokinin gene isolated from a wide host range biotype III Agrobacterium strain. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;216:428–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00334387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasch M A, Meyer R J. A 38 base-pair segment of DNA is required in cis for conjugative mobilization of broad host-range plasmid R1162. J Mol Biol. 1987;198:361–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Bravo-Angel, A. M. Unpublished data.

- 6.Bravo-Angel A M, Hohn B, Tinland B. The omega sequence of VirD2 is important but not essential for efficient transfer of T-DNA by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:57–63. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchanan-Wollaston V, Passiatore J E, Cannon F. The mob and oriT mobilization functions of a bacterial plasmid promote its transfer to plants. Nature. 1987;328:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christie P J, Ward J E, Winans S C, Nester E W. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens virE2 gene product is a single-stranded-DNA-binding protein that associates with T-DNA. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2659–2667. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2659-2667.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Citovsky V, Zupan J, Warnick D, Zambryski P. Nuclear localization of Agrobacterium VirE2 protein in plant cells. Science. 1992;256:1802–1805. doi: 10.1126/science.1615325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng W, Chen L, Wood D W, Metcalfe T, Liang X, Gordon M, Comai L, Nester E W. Agrobacterium VirD2 protein interacts with plant host cyclophilins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7040–7045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frey J, Bagdasarian M M, Bagdasarian M. Replication and copy number control of the broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010. Gene. 1992;113:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90675-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fullner K J. Role of Agrobacterium virB genes in transfer of T complexes and RSF1010. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:430–434. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.430-434.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gheysen G, Villarroel R, van Montagu M. Illegitimate recombination in plants: a model for T-DNA integration. Genes Dev. 1991;5:287–297. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grevelding C, Fantes V, Kemper E, Schell J, Masterson R. Single-copy T-DNA insertions in Arabidopsis are the predominant form of integration in root-derived transgenics, whereas multiple insertions are found in leaf discs. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;23:847–860. doi: 10.1007/BF00021539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooykaas P J J, Beijersbergen A. The virulence system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1994;32:157–179. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard E A, Zupan J R, Citovsky V, Zambryski P C. The VirD2 protein of A. tumefaciens contains a C-terminal bipartite nuclear localization signal: implication for nuclear uptake of DNA in plant cells. Cell. 1992;68:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen B J, Gardner R C. Localized transient expression of GUS in leaf discs following cocultivation with Agrobacterium. Plant Mol Biol. 1989;14:61–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00015655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K, Meyer R J. Unidirectional transfer of broad host-range plasmid R1162 during conjugative mobilization. Evidence for genetically distinct events at oriT. J Mol Biol. 1989;208:501–505. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90513-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohli A, Leech M, Vain P, Laurie D A, Christou P. Transgene organization in rice engineered through direct DNA transfer supports a two-phase integration mechanism mediated by the establishment of integration hot spots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7203–7208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lessl M, Lanka E. Common mechanisms in bacterial conjugation and Ti-mediated T-DNA transfer to plant cells. Cell. 1994;77:321–324. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y-G, Mitsukawa N, Oosumi T, Whitier R F. Efficient isolation and mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA insert junction by thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR. Plant J. 1995;8:457–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08030457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machida Y, Shimoda N, Yamamoto-Toyoda A, Takahashi Y, Nishima R, Aoki S, Matsuoka K, Nakamura K, Yoshioka Y, Ohba R, Obata R T. Molecular interaction between Agrobacterium and plant cells. In: Nester E W, editor. Advances in molecular genetics of plant-microbe interactions. Vol. 2. Boston, Mass: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1993. pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayerhofer R, Koncz-Kalman Z, Nawrath C, Bakkeren G, Crameri A, Angelis A, Redei G P, Schell J, Hohn B, Koncz C. T-DNA integration: a mode of illegitimate recombination in plants. EMBO J. 1991;10:697–704. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07999.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio-assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nam J, Matthysse A G, Gelvin S B. Differences in susceptibility of arabidopsis ecotypes to crown gall disease may result from a deficiency in T-DNA integration. Plant Cell. 1997;9:317–333. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otten L, De Greve H, Leemans J, Hain R, Hooykaas P J, Schell J. Restoration of virulence of vir region mutants of Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain B6S3 by coinfection with normal and mutant Agrobacterium strains. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;195:159–163. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pansegrau W, Schröder W, Lanka E. Concerted action of three distinct domains in the DNA cleaving-joining reaction catalysed by relaxase (TraI) of conjugative plasmid RP4. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2782–2789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paszkowski J, Shillito R D, Saul M W, Mandak V, Hohn T, Hohn B, Potrykus I. Direct gene transfer to plants. EMBO J. 1984;3:2717–2722. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ream W. Agrobacterium tumefaciens and interkingdom genetic exchange. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1989;27:583–618. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.27.090189.003055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossi L, Escudero J, Hohn B, Tinland B. Efficient and sensitive assay for T-DNA dependent transient gene expression. Plant Mol Biol Reporter. 1993;12:220–229. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossi L, Hohn B, Tinland B. Integration of complete T-DNA units is dependent of the activity of VirE2 protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:126–130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossi L, Hohn B, Tinland B. The VirD2 protein carries nuclear localization signals important for transfer of T-DNA to plants. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;239:345–353. doi: 10.1007/BF00276932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossi L, Tinland B, Hohn B. Role of virulence protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens in the plant cell. In: Spaink H, Hooykaas P, Kondorosi A, editors. The Rhizobiaceae, in press. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1996. pp. 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scholz P, Haring V, Wittmann-Liebold B, Ashman K, Bagdasarian M, Scherzinger E. Complete nucleotide sequence and gene organisation of the broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010. Gene. 1989;75:271–288. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shadenkov A A, Kovaleva M V, Kuz’min E V, Uzbekova S V, Shemyakin M F. VirD2-independent but MobA-dependent transfer of broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010 DNA from Agrobacterium into plant cell nucleus. Mol Biol. 1996;30:272–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheng J, Citovsky V. Agrobacterium-plant cell DNA transport: have virulence proteins, will travel. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1699–1710. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stachel S E, Nester E W. The genetic and transcriptional organization of the vir region of the A6 Ti plasmid of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. EMBO J. 1986;5:1445–1454. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stachel S E, Timmerman B, Zambryski P. Generation of single-stranded T-DNA molecules during the initial stages of T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to plant cells. Nature. 1986;322:706–711. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stahl L E, Jacobs A, Binns A N. The conjugal intermediate of plasmid RSF1010 inhibits Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence and VirB-dependent export of VirE2. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3933–3939. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3933-3939.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tinland B. The integration of T-DNA into plant genomes. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1:178–184. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tinland B, Hohn B. Recombination between procaryotic and eucaryotic DNA: integration of Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA into the plant genome. In: Setlow J K, editor. Genetic engineering: principles and methods. Vol. 17. New York, N.Y: Plenum; 1995. pp. 209–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tinland B, Koukolíková-Nicola Z, Hall M N, Hohn B. The T-DNA-linked VirD2 protein contains two distinct functional nuclear localization signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7442–7446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tinland B, Schoumacher F, Gloeckler V, Bravo-Angel A M, Hohn B. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence D2 protein is responsible for precise integration of T-DNA into the plant genome. EMBO J. 1995;14:3585–3595. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waters V L, Guiney D G. Processes at the nick region link conjugation, T-DNA transfer and rolling circle replication. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1123–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zambryski P C. Chronicles from the Agrobacterium-plant cell DNA transfer story. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1992;43:465–490. [Google Scholar]