Abstract

External auditory canal cholesteatomas (EACC), are rare, more so when they affect the facial nerve in its vertical mastoid segment. EACC are known to possess bone eroding properties, causing a variety of complications, similar to the better-known attic cholesteatomas. We describe here the novel surgical management of a case of EACC, affecting only the vertical segment of the facial nerve, causing seventh nerve palsy at the time of presentation. A 46 year old male, complaining of right-sided otalgia and otorrhea, presented with grade IV facial palsy and associated mild conductive hearing loss. Clinical examination and radiological investigations suggested the diagnosis of an external auditory canal cholesteatoma. The patient underwent a trans-canal facial nerve decompression along with the cholesteatoma removal. Post-operatively, the patient showed marked clinical improvement with the facial palsy reverting to grade II. EACC involving only the vertical segment of the facial nerve can be approached via the trans-canal route, in contrast to the conventional postauricular approach, with a good clinical outcome. To the best of our knowledge, our case pertains to the only case of EACC with complications, managed by trans-canal facial nerve decompression.

Keywords: External auditory canal cholesteatoma, Facial nerve, Keratosis obturans, Facial nerve palsy, Facial nerve decompression

Introduction

An external auditory canal cholesteatoma (EACC) is a rare entity, with an incidence of 0.1–0.5% of new patients presenting with otologic complaints [1]. An EACC can erode bone, causing complications such as the invasion of the mastoid cavity, facial nerve paralysis, labyrinthine fistulae, erosion of the temporomandibular joint, invasion of the skull base, meningitis, and intracranial abscesses, not unlike an attic cholesteatoma [2]. The propensity of EACC to invade the vertical segment of the facial nerve has been seen, with very few mentions in literature. We present a rare case report of an EACC with facial nerve palsy, due to the involvement of the vertical segment of the nerve, which was managed by decompression of the facial nerve through the external auditory canal.

Case Report

A 46 year old male, with no comorbidities, presented to the ENT clinic, with complaints of right-sided otalgia and otorrhea for 1 month, with an inability to close the right eye and deviation of the angle of mouth to the left for 10 days. The otalgia was mild, of dull character, and did not disturb sleep. Ear discharge was scanty, purulent, and with a putrid smell. There was no history of reduced hearing, vertigo, or tinnitus, ruling out labyrinthine involvement. There was no history of headache, fever, vomiting, neck stiffness, ear trauma, or episodes of ear discharge in childhood.

On clinical examination, the right external auditory canal (EAC) was filled with greyish white cholesteatoma flakes, along with the erosion of the posterior and inferior canal wall. The right-sided tympanic membrane was intact with Grade 1 pars tensa retraction. The pars flaccida was normal. The right facial nerve showed Grade IV palsy according to the House-Brackman grading (HBG). Cerebellar signs were negative. Tuning fork tests and a pure tone audiogram showed a right-sided mild conductive hearing loss. A provisional clinical diagnosis of right EAC cholesteatoma with facial nerve palsy was made. The rest of the otolaryngologic, general, and systemic examination was unremarkable.

A high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan of the temporal bone was taken, which showed posterior and inferior bony EAC widening, and erosion, also involving the vertical segment of the facial nerve. The attic, middle ear, scutum, ossicular chain, and bony canal over the horizontal segment of the facial nerve were intact. There was no soft tissue density in the tympano-mastoid cavity. There was no evidence of tegmen or sinus plate erosion and no obvious intracranial extension.

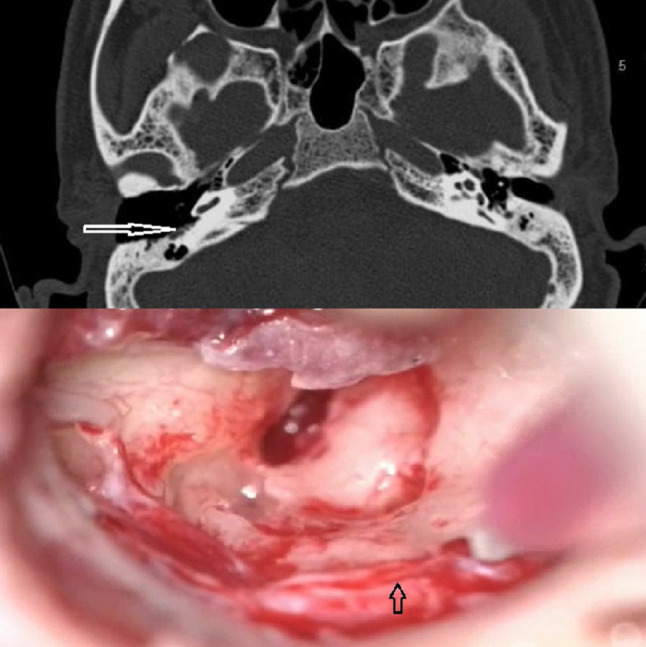

The patient underwent a trans-canal facial nerve decompression and canaloplasty under general anesthesia. Intra-operatively, cholesteatoma flakes were removed and the tympanomeatal flap was elevated. No cholesteatoma was found in the epitympanum or mesotympanum. The posterior canal wall was drilled to expose the vertical segment of the facial nerve. The bone over the entire segment of the facial nerve from the second genu to the stylomastoid foramen was thinned. The bone over the vertical segment was removed and the intact nerve sheath was excised, decompressing the oedematous facial nerve (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

HRCT image (top panel) and intra-operative photograph (bottom panel). High-Resolution Computed Tomography picture (top panel) showing widened EAC on the right side. The white arrow shows the exposed vertical segment of the facial nerve. Intraoperative view (bottom panel) showing the exposed facial nerve. The sheath of the vertical segment of the facial nerve (arrow) was incised to decompress the nerve via the trans-canal route. (Patient consent obtained for the publication of the photograph)

The exposed nerve was covered with steroid soaked absorbable gelatin foam. The tympanomeatal flap was repositioned and the EAC was filled with antibiotic ointment.

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was referred to physiotherapy for facial nerve exercises. Over 2 months, the patient recovered significantly and was left with a grade II facial paresis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Preoperative (left) and postoperative (right) clinical photograph of the patient. The facial palsy improved throughout the follow-up. (Patient consent obtained for publication of the photograph)

Discussion

The EAC cholesteatoma is a rare entity seen in the ENT clinic. The reported incidence stands at about 1.2–3.7 out of every 1000 new cases presenting to an otolaryngologist [2]. Accumulation of keratin plugs in the deep bony EAC has been described as both due to keratosis obturans and EACC, although entities such as malignant otitis externa, osteoradionecrosis of the temporal bone, squamous cell carcinoma of the EAC, and post-inflammatory medial canal fibrosis may mimic an EACC clinically [3].

Keratosis obturans (KO), being the closest differential diagnosis, is bilateral and is seen in younger patients. A widened ear canal is also seen in KO, due to local pressure, causing entire circumferential canal distension [4]. EACC, on the other hand, is a separate condition, differentiated from KO first by Piepergerdes et al. in 1980. EACC presents in the elderly, with intermittent or persistent ear discharge and dull ear pain. Hearing loss is not usually apparent as the tympanic membrane is mostly intact [5]. The EACC causes extensive osteolysis and invasion of the bony external canal wall, due to localized periostitis and sequestration of bone. The advancing end of the bony invasion comprises of an epithelialized sac, which secretes proteolytic enzymes weakening the bone. The accumulating keratin debris harbor moisture and bacteria, causing ulceration and forming granulation tissue, resulting in purulent otorrhea [3]. The diagnosis in our case report conforms to the clinical picture of EACC, as opposed to KO.

The rate of epithelial migration is the fastest and the vascularity least along the floor of the EAC. Abnormal lateral migration of the epithelium of the EAC, especially along the poorly vascularised floor, leads to ‘keratinization in situ [6] and accumulation of squamous cell flakes. Bony sequestrum builds up, eroding the mastoid. Microangiopathy of the blood vessels, microtrauma, dehiscence of the petrotympanic fissure, canal stenoses, and entrapment of first branchial cleft epithelium have also been variously attributed to the causation of EACC [7]. Holt classified EACC based on etiology into the following groups—Postsurgical, post-traumatic, congenital or ear canal stenosis, post-obstructive, post-inflammatory, and spontaneous [8]. The above patient appeared to have a spontaneous etiology for the EACC.

Cross-sectional imaging by high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) aids in the diagnosis of the extent of the cholesteatoma in general and invasion of the attic and labyrinth in particular. EACC appears as an ovoid soft-tissue density, with well-defined margins. The lesion may extend as far as the temporomandibular joint anterior to the EAC, the hypotympanum, the jugular bulb, the mastoid cavity proper, and the bony wall of the facial nerve canal [9]. The involvement of the fallopian canal may be seen in the form of unroofing of the bone over the canal or as direct involvement of the canal along with cholesteatoma in the mastoid cavity. An isolated canal wall cholesteatoma does not show the opacification of the mastoid air cells. The erosion of the EAC may be smooth as in cholesteatomas in general or irregular in case of diffuse periostitis. A uniform clinical staging system was proposed by Naim et al. [10], also taking into account the histopathological picture. The above case falls into stage IV, subclassified into class F due to facial nerve palsy.

The treatment ranges from conservative treatment with frequent atraumatic aural toilet to canal wall down mastoidectomy with adequate reconstruction and obliteration of the cavity. Surgery should be tailored to the extent of the disease and is indicated in EACC to prevent progression, to provide an open clean canal, and to halt the erosive pathology.

In the above case, the cholesteatoma confined to the EAC had eroded only the mastoid segment of the facial nerve as it coursed through the posterior canal wall. A trans-canal facial nerve decompression was planned as the patient had well maintained anatomic landmarks, intact ossicular chain, and minimal preoperative conductive hearing loss. This was a deviation from the accepted canal wall down mastoidectomy and reconstruction of the defect with soft tissue grafting, usually followed for Naim stage IV lesions [10]. The mastoid cavity was not drilled in our case. The postoperative course of the patient as reported was good, as facial palsy reverted to a lower HB grade. Histopathologic examination of the cholesteatoma along with granulations and sequestrum is necessary to rule out malignancies of the external canal, which may look similar clinically.

Conclusions

In the very small proportion of patients of EACC who present with facial palsy, surgery should not be delayed. In cases with facial nerve palsy involving the vertical segment of the facial nerve, modification of the routine trans-mastoid approach is a feasible option. The surgical routes can be tailored to the extent of the disease. Rational individualization of the approach is mandatory to preserve nerve function. To the best of our knowledge, our report is the only case of EACC with isolated involvement of the vertical mastoid segment of the facial nerve, treated with trans-canal decompression and cholesteatoma removal.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgments to declare.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Raghul Sekar, Email: raghul8020@gmail.com.

Stuti Chowdhary, Email: stuti.9894@gmail.com.

Arun Alexander, Email: arunalexandercmc@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Hartley C, Birzgalis AR, Hartley RH, Lyons TJ, Farrington WT. External ear canal cholesteatoma. Case report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104:868–870. doi: 10.1177/000348949510401108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho KY, Huang TY, Tsai SM, Wang HM, Chien CY, Chang NC. Surgical treatment of external auditory canal cholesteatoma—10- years of clinical experience. J Int Adv Otol. 2017;13(1):9–13. doi: 10.5152/iao.2017.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heilbrun ME, Salzman KL, Glastonbury CM, Harnsberger HR, Kennedy RJ, Shelton C. External Auditory Canal Cholesteatoma: clinical and Imaging Spectrum. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;1(24):751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glynn F, Keogh IJ, Burns H. Neglected keratosis obturans causing facial nerve palsy. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:784–785. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106001137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piepergerdes MC, Kramer BM, Behnke EE. Keratosis obturans and external auditory canal cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:383–391. doi: 10.1002/lary.5540900303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubach P, Mantokoudis G, Caversaccio M. Ear canal cholesteatoma: a meta-analysis of clinical characteristics with update on classification, staging and treatment. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;18:369–376. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32833da84e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konishi M, Iwai H, Tomoda K. Reexamination of etiology and surgical outcome in patient with advanced external auditory canal cholesteatoma. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37:728–734. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holt JJ. Ear canal cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:608–613. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199206000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jerbi Omezzine S, Dakkem M, Ben Hmida N, et al. Spontaneous cholesteatoma of the external auditory canal: the utility of CT. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2013;94:438–442. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naim R, Linthicum F, Jr, Shen T, Bran G, Hormann K. Classification of the external auditory canal cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:455. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000157847.70907.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]