Abstract

Background

There is pressing need to improve hospital-based addiction care. Various models for integrating substance use disorder care into hospital settings exist, but there is no framework for describing, selecting, or comparing models. We sought to fill that gap by constructing a taxonomy of hospital-based addiction care models based on scoping literature review and key informant interviews.

Methods

Methods included a scoping review of the literature on US hospital-based addiction care models and interventions for adults, published between January 2000 and July 2021. We conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 key informants experienced in leading, implementing, evaluating, andpracticing hospital-based addiction care to explore model characteristics, including their perceived strengths, limitations, and implementation considerations. We synthesized findings from the literature review and interviews to construct a taxonomy of model types.

Results

Searches identified 2,849 unique abstracts. Of these, we reviewed 280 full text articles, of which 76 were included in the final review. We added 8 references from reference lists and informant interviews, and 4 gray literature sources. We identified six distinct hospital-based addiction care models. Those classified as addiction consult models include (1) interprofessional addiction consult services, (2) psychiatry consult liaison services, and (3) individual consultant models. Those classified as practice-based models, wherein general hospital staff integrate addiction care into usual practice, include (4) hospital-based opioid treatment and (5) hospital-based alcohol treatment. The final type was (6) community-based in-reach, wherein community providers deliver care. Models vary in their target patient population, staffing, and core clinical and systems change activities. Limitations include that some models have overlapping characteristics and variable ways of delivering core components.

Discussion

A taxonomy provides hospital clinicians and administrators, researchers, and policy-makers with a framework to describe, compare, and select models for implementing hospital-based addiction care and measure outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07618-x.

KEY WORDS: addiction consult service, psychiatry consult liaison service, hospital-based opioid treatment, substance withdrawal syndrome, substance-related disorders, hospitalized patient, referral and consultation

BACKGROUND

Amidst an unrelenting substance use disorder (SUD) epidemic, SUD-related hospitalizations are rising across the USA.1–4 One in nine hospitalized adults has SUD.5 Most hospitalized patients with SUD are not engaged in addiction care or seeking treatment at admission6,7; yet hospitalization is a critical touchpoint to engage and intervene with people with SUD.8,9 Hospital-based SUD care can improve patient and provider experience,10,11 increase trust in hospital physicians,12 increase adoption of evidence-based treatment,13 increase post-hospital SUD treatment engagement,7,14 reduce substance use severity,14,15 reduce death,16 and transform health systems to be more healing for people who use drugs.11 Despite its effectiveness, few hospitals offer evidence-based SUD care.6

The opioid crisis has spurred new efforts to address SUD in hospitals, propagating new care models, often without formal guidance. While there is growing consensus that all hospitals must be able to provide a basic level of SUD care, in reality, hospitals have widely varied readiness to embrace SUD care, expertise, resources, and needs. To date, there is no framework that categorizes, compares, and contrasts hospital-based addiction care models. This limits clinicians and policy-makers’ ability to select approaches. It also poses a barrier to understanding effectiveness of various approaches and to informing best practice guidelines, because of the heterogeneity of the models being tested.

To fill this gap, we constructed a taxonomy of hospital-based addiction care models. Better classifying and characterizing these models can promote more rigorous evaluation and broader adoption and implementation of such models as clinicians, hospital leaders, payers, and policy-makers work to meet urgent and widespread clinical needs.

METHODS

We constructed a taxonomy of hospital-based addiction care models in four steps: (1) generating a preliminary list of model types, including representative examples; (2) performing a scoping literature review; (3) conducting key informant interviews; and (4) analyzing findings to construct a taxonomy. The OHSU institutional review board approved this study (#00022957).

Generating Preliminary List of Model Types

Authors generated an initial list of model types, including representative examples, based on our knowledge of the literature and the field. We identified an initial list based on models’ adoption in current clinical practice, innovativeness, or focus on specific populations or settings. We reviewed published examples of representative models and abstracted data about staffing, clinical infrastructure, core clinical activities, educational and other activities, funding, service scope and size, and keyword search terms and MeSH headings to inform step 2. We also used this step to refine the interview guide and identify informants for step 3.

Scoping Review

We conducted a scoping review using PRISMA-ScR reporting guidelines.17 In July 2021, a trained medical librarian (TR) searched for studies describing hospital-based addiction care models published after 2000 without language restrictions in the MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycInfo databases using the Ovid search platform and the CINAHL databases using the Ebsco search platform (see Appendix for full search). We expanded our initial list of search terms by reviewing reference lists and tailored terms to each database using key words and control vocabulary.

Included studies described an SUD care model or clinical intervention serving adults (≥18 years) in a US general hospital setting. We included models that addressed any SUD, but not those addressing tobacco use disorder alone. Excluded were studies published before 2000 because of the transformative impact of the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000, which allowed bupre1norphine to be administered outside of opioid treatment programs, including in hospitals.18 Additional exclusion criteria were studies without an inpatient general hospital component (e.g., Emergency Department only); that focused solely on screening or withdrawal management; that had no medical component (e.g., peer-only interventions); or were medication trials or guidelines only and did not describe a hospital-based delivery model or its outcome. Finally, we excluded abstracts and titles without full text articles and studies not published in English.

We used Covidence software to conduct screening.19 At least two authors reviewed each title and abstract for inclusion, and resolved any disagreements by consulting additional authors. Two authors (H. E., A. J.) reviewed each full text article and met to resolve disagreements. We added additional articles and gray literature identified from reference lists and key informant interviews. We did not register this protocol.

Key Informant Interviews

We identified informants based on the literature review and professional networks. We purposively selected informants across diverse regions, organizations, and professional backgrounds with experience leading, implementing, evaluating, and practicing hospital-based addiction care, recruiting informants who could represent diverse model types, including published and unpublished models. We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to create a semi-structured interview guide.20 We conducted interviews via videoconference. One interviewer (H. E.) conducted individual interviews (and one two-person interview) and one researcher (A. J.) took detailed field notes. We asked participants to describe hospital-based addiction care models they have seen in practice and to specify key components, perceived strengths and limitations, and implementation considerations. We presented patient scenarios to clarify model details and distinguishing features. We recruited informants until we reached saturation and had clearly defined model components and distinguishing features.

Analysis of Findings to Construct a Taxonomy

We conducted a content analysis of informant interviews based on model components of interest, including target patient population, staffing, core clinical activities, efforts to direct system-change, and necessary resources. The research team (H. E., A. J., N. K., A. P., J. M.) met regularly to discuss findings from the scoping review and interviews, and formed definitions of models’ fundamental parameters and characteristics, which led to a final taxonomy. Model definitions emphasized essential elements and distinguishing features as described by informants and the literature. We aimed to create meaningful categories with defined minimum criteria that reflect current practice. If manuscripts did not fit into our categories because they had some but not all elements of a given model type, we grouped them with the model where they met all minimum criteria.

RESULTS

Searches identified 2,849 unique abstracts. Of these, we reviewed 280 full text articles, 75 of which met inclusion criteria. We identified an additional 8 references from reference lists and informant interviews. We identified 4 gray literature sources. The literature flow diagram (Appendix) summarizes search results and the study selection process. Table 1 summarizes final sources.

Table 1.

Sources of hospital-based addiction care models

| Model | Published literature | Gray literature | Key informant interview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addiction consult models | |||

| Interprofessional addiction consult service |

Reports with multiple ACS sites21–25 Massachusetts General Hospital 14,32–35 New York City Hospital + Health Systems36 Oregon Health & Science University7,8,10,11,12,13,15,37–42 University of California San Francisco46 University of Colorado47 Yale University51 |

Allegheny Health Network54 | ✓ |

| Psychiatry consult liaison service |

Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston)55–58 University of California Davis61 University of California Los Angeles62 University of Hawaii63 University of Minnesota64 University of Texas San Antonio65 Yale University66 York Hospital, PA67 |

Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston)69 | ✓ |

| Individual consultant |

Aurora St. Luke’s, Milwaukee70 University of Alabama at Birmingham73–75 Washington University St Louis78–80 University of Wisconsin81 |

✓ | |

| Practice-based models | |||

| Hospital-based opioid treatment (HBOT) |

CA Bridge (multiple hospitals)82 Concord, NH83 BI Deaconess, Boston84 Duke University85 Johns Hopkins86 Lehigh Valley87 Maryland88 Rutgers89 University of California San Francisco90 University of Louisville91 University of Miami92 |

CA Bridge (multiple hospitals)95 | ✓ |

| Hospital-based alcohol treatment | University of California San Francisco96 | ✓ | |

| In-reach models | |||

| Community-based in-reach | Boston Medical Center97 | Boulder Care98 | ✓ |

| Multiple model types | |||

| N/A99,100 | |||

We interviewed 15 informants (13 individual and one two-person interview) between June and October 2021. Because physicians led most published models, most informants were physicians. Informants included experts with experience across wide-ranging disciplines, practice settings, and geographic regions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key informant participants

| Key informants (n=15) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Profession (n=15) | |

| Physician | 12 (80) |

| Advanced practice provider | 1 (7) |

| Peer support specialist | 1 (7) |

| Healthcare technology CEO | 1 (7) |

| Medical specialty* (n=13) | |

| Addiction medicine | 7 (46) |

| Hospital medicine | 6 (40) |

| Addiction psychiatry | 2 (15) |

| Family medicine | 2 (15) |

| Infectious diseases | 2 (15) |

| General internal medicine | 2 (15) |

| Primary practice setting (n=15) | |

| Academic medical center | 8 (53) |

| Telehealth | 2 (13) |

| Community-based organization | 2 (13) |

| Veterans Affairs hospital | 1 (7) |

| Community hospital | 1 (7) |

| Community clinic | 1 (7) |

| US geographical region (n=15) | |

| West | 8 (53) |

| Northeast | 2 (13) |

| Midwest | 2 (13) |

| Southwest | 2 (13) |

| Southeast | 1 (7) |

*Categories not mutually exclusive

We identified six distinct hospital-based addiction care models. Those classified as addiction consult models include (1) interprofessional addiction consult services (ACSs), (2) psychiatry consult liaison (PCL) services, and (3) individual consultant models. Those classified as practice-based models, wherein general hospital staff integrate addiction care into usual practice, include: (4) hospital-based opioid treatment (HBOT) and (5) hospital-based alcohol treatment (HBAT). The final type was (6) community-based in-reach, wherein community providers deliver care. Models vary in their target patient population, staffing, and core clinical and systems change activities.

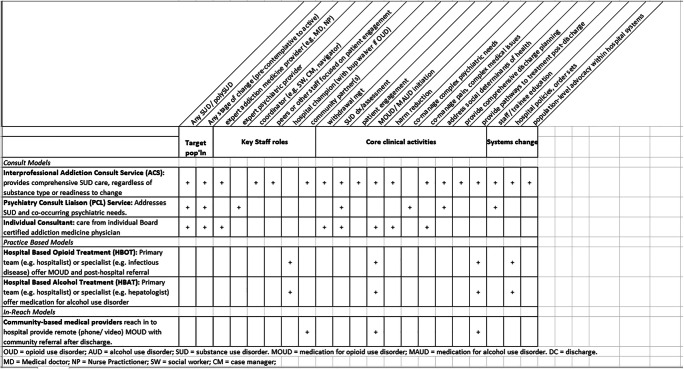

Table 3 defines each model’s fundamental components. In practice, models may include additional components. For example, while not all PCL services offer medication for OUD, some do. Further, models may deliver core clinical activities differently and to varied degrees. For example, an ACS may arrange for a hospital-based peer to accompany patients to follow-up appointments, whereas a practice-based model might schedule an appointment; however, both meet the criteria for providing post-discharge treatment pathways.

Table 3.

Fundamental components for each model, including target patient population, required staffing, and core clinical and systems change activities

Table 4 describes how models deliver various components. Below, we summarize the six model types, comparing and contrasting model strengths, limitations, and implementation considerations.

Table 4.

Taxonomy: model descriptions

| Addiction consult models | Target patient population | Staffing | Core clinical activities | Systems change activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interprofessional addiction consult service (ACS): Provides comprehensive care for people SUD. Educates staff and trainees. Creates hospital and health system-level change. | Any substance, any readiness for change |

Team-based care that, at minimum, includes (1) medical provider (addiction physician or advanced practice practitioner), (2) dedicated social worker or case manager with addictions expertise. Often includes others, including peers, navigators, nurses, pharmacists Care is typically delivered in-person, though some telehealth ACS exist. Staff may have longitudinal relationship with patients over multiple admissions and across varied stages of change. Staff have dedicated time and funding, which may include come from hospital, grants, and billing revenue. |

Provide comprehensive SUD assessment and diagnosis (e.g., DSM-5, ASAM assessments) Identify and treat withdrawal (including polysubstance) Offer evidence-based treatment with medications (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine, acamprosate); provide buprenorphine at discharge Provide supported pathways to various community SUD services (e.g., opioid treatment programs, harm reduction services, residential programs). Explicit engagement efforts (e.g., peers) Emphasize trauma-informed care and harm reduction. Support complex acute medical needs (e.g., pain) Advocate for patients to receive needed care (e.g., valve replacement surgery, hepatitis treatment) Provide early comprehensive discharge planning that address social determinants of health. |

Widespread hospital staff education (bedside and didactics), often addressing stigma Include trainees (e.g., fellow, resident, interdisciplinary students). Improve hospital practices (e.g., endocarditis care) and policies (e.g., active use) Lead large scale quality improvement efforts, including responding to emerging needs (e.g., COVID, changes in drug supply) |

| Psychiatry consult liaison service (PCL): Typically focuses on addressing SUD and co-occurring psychiatric needs. Not all offer MOUD or MAUD. | Patients with co-occurring SUD and other mental health condition. |

Typically includes psychiatrist (general or addiction psychiatry) and a psychiatric social worker who is familiar with local mental health resources. Staff have dedicated time/funding; typically on site and in person. Staff typically funded by hospital and billing revenue. |

Comprehensive psychiatric diagnosis (e.g., DSM-5) May offer motivational interviewing or behavioral therapies Psychiatric medication management; though some do not offer MOUD. Make recommendations for post-hospital treatment setting (e.g., detoxification, community dual diagnosis treatment); less likely than ACS to have established community partnerships and supported treatment pathways. |

Rare; not explicit focus of model. |

| Individual consultant: | All patients, regardless of interest in changing use, substance type, or interest in a particular treatment |

Addiction physician (backgrounds vary, include psychiatry, toxicology, internal medicine/family medicine) Typically funded through billing revenue, sometimes with additional grant or hospital funding. May partner with other disciplines (e.g., infectious disease consultants) to address specific disease conditions (e.g., endocarditis). Does not include a team member whose primary focus is engagement (such as peers or social workers). |

Diagnose and treat SUD. Identify and treat withdrawal. Offer evidence-based medication for all SUD and provide bridge buprenorphine prescription at discharge. Sometimes partner with other disciplines to guide hospital care (e.g., multidisciplinary endocarditis management). Usually partner with general hospital staff (e.g., unit social worker) who may make treatment referrals. |

May develop order sets, protocols, and general provider education materials. |

| Practice-based models | Target patient population | Staffing | Core clinical activities and notable features | Systems change activities |

| Hospital-based opioid treatment (HBOT): Primary team (e.g., hospitalist) or specialist consultant (e.g., infectious disease provider) offer medication for opioid use disorder as part of their standard practice. | Patients with OUD interested in medication treatment. |

Requires general hospital providers (e.g., hospitalists, residents) or subspecialists with buprenorphine waiver. Some HBOT models have additional supports such as dedicated navigator. Staff often connected with formal and informal mentoring, warm lines, and other training/clinical supports. Typically no dedicated funding. |

Offer MOUD (buprenorphine; may or may not also offer methadone, naltrexone intramuscular). Some offer naloxone kits and overdose education. Refer to post-hospital OUD treatment, including prescription for buprenorphine at discharge. Typically model does not address co-occurring pain, complex clinical decision-making (e.g. assessing appropriateness for surgery) or explicit efforts around motivational enhancement or patient engagement. |

Prescribers commonly rely on buprenorphine and/or methadone protocols/order sets and policies. |

| Hospital-based alcohol treatment (HBAT): Primary team or specialist consultant (e.g., hepatology) offer medication for alcohol use disorder as part of standard practice. | Patients with AUD interested in medication treatment. |

Care delivered by general hospital providers (e.g., hospitalists, residents) or subspecialists as part of their usual care. Example of RN-driven HBAT. Typically no dedicated funding. |

Offer medication for alcohol use disorder (e.g., naltrexone, acamprosate) in hospital. Refer to post-hospital AUD treatment, typically through primary care medication based treatment and/or recommending fellowship resources (e.g., alcoholics anonymous). |

May include order sets and protocols to guide care. |

| In-reach models | Target patient population | Staffing | Core clinical activities and notable features | Systems change activities |

| Community-based provider in-reach provides remote support to initiate or sustain MOUD during admission. | Patients interested in initiating MOUD or already on MOUD at time of admission |

Typically, community medical providers with buprenorphine waiver (e.g., primary care or specialty addictions providers). Example of RN-based in-reach with community nurse who is connected to outpatient substance use treatment programs. Staff are not formal part of hospital care teams. Typically no dedicated funding and may be difficult for providers to bill encounters if not credentialed at hospital. Typically providers are local clinicians, though telehealth opportunity exists. |

General hospital providers contact community providers who may provide brief assessment (typically by phone or video). Offer guidance to primary teams re initiation and provision of MOUD. For buprenorphine, typically offer bridge prescription and follow up appointment in their ambulatory practice at discharge. Staff typically do not document in the hospital record. |

N/A; focus is direct patient contact with referral after discharge. |

OUD opioid use disorder, AUD alcohol use disorder, SUD substance use disorder, MOUD medication for opioid use disorder, MAUD medication for alcohol use disorder, DSM-5 Diagnostic Specific Manual 5th edition, ASAM American Society of Addiction Medicine, RN registered nurse

Addiction Consult Models

Interprofessional Addiction Consult Services include comprehensive care from an expert addiction provider, a dedicated coordinator (e.g., social work or case manager), and staff focused on patient engagement (e.g., peers), and often other roles including nurses or pharmacists.21,36,37,43,46,48 ACSs work with patients with any substance type and all stages of change. ACSs address broad patient complexity, including polysubstance use, serious medical illness (e.g., end of life care), complex medical decision making (e.g., valve surgery, transplant101), and complex behavioral issues (e.g., active substance use during admission). ACSs provide comprehensive assessments102 and care includes an explicit focus on patient engagement and harm reduction tailored to patient priorities and risks.103 ACSs typically promote staff and trainee education and hospital culture change11 (e.g., leading hospital-wide stigma reduction efforts). Further, ACSs can serve as a platform for population health improvement efforts101 and respond to emerging needs such as COVID.22,38 ACSs do not necessarily include psychiatry expertise and may be less prepared to provide comprehensive care for patients with co-occurring psychiatric illness than PCL. Several informants described ACS partnering with PCL to address this gap, and some ACSs include addiction psychiatrists within their multidisciplinary teams. Informants stressed that ACS’ ability to support post-hospital treatment linkages depends on community resources; some ACSs have developed new treatment pathways8 and/or partnered to expand community access (e.g., developed bridge clinics).32,104

Informants noted ACS implementation considerations related to staffing, resources, and funding. Lack of qualified addiction providers can be a significant obstacle to initiating or scaling up ACS.105 One hospital addressed this gap by training hospitalists in addiction medicine, protecting their time, and encouraging them to pursue board certification while fulfilling their ACS roles.47 Several informants discussed the potential for telehealth to address staffing shortages, including existing or planned tele-ACS that includes addiction physicians, peers, and coordinators. Informants described potential for tele-ACS in rural settings where ACS could be deployed regionally as an extension of an existing ACS. Another common ACS challenge is funding non-revenue generating staff (e.g., peers).23 Informants described pursuing grant funding, demonstrating length of stay and quality benefits, and aligning efforts with hospital priorities as strategies for supporting and sustaining ACS.

Psychiatry Consult Liaison Services provide expert management of patients with complex psychiatric illness, often including SUD. PCLs are staffed by psychiatrists and frequently include a social worker or psychologist with expert knowledge of community mental health resources.55,59,61,62,64,106 Commonly, PCLs have a diagnostic focus, and provide psychiatric medication management (e.g., for psychosis or depression) and behavioral interventions, including motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapies.66,106 In academic settings, medical trainees are often integral members of the PCL team.

Informants and literature support that historically, many PCLs have not included SUD in their primary scope, and not all PCLs offer medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD).55,59,106 Informants felt that this can occur because PCLs may be under-staffed, or that some psychiatrists have limited training in addiction and MOUD. Compared to ACSs, PCLs focus less on acute medical and surgical complications of SUD (e.g., pain, infectious complications of SUD).107 Informants noted that PCL may have clearer connections to community mental health and less comprehensive pathways to community SUD services than ACS.

In the individual consultant model, a single physician with board certification in addiction offers consultation that includes acute medical needs such as withdrawal and MOUD and/or medication for alcohol use disorder (MAUD) initiation.81 Physicians may draw from multiple disciplines (e.g., internal medicine, toxicology, psychiatry), and they may partner with specialty teams for specific health conditions or populations.70,71,76,81,108 Typically, individual consultants partner with general hospital staff (e.g., social workers, discharge planners) to support post-hospital treatment referrals.

Informants described one advantage of the individual consultant model is feasibility; it is less resource intensive than ACS, and physician billing can help finance service delivery. Many informants described that the individual consultant can be a stepping stone to developing a full ACS. Informants highlighted that without dedicated interdisciplinary staff, individual consultants may be less able to engage pre-contemplative, non-treatment seeking patients; address comprehensive complex discharge needs; and fully address social determinants of health. Individual consultants also typically have other clinical commitments (e.g., outpatient practice) that compete for their attention to hospitalized patients. Others noted inefficient use of consultants’ time spent coordinating care that non-physician staff with SUD expertise could address. Informants also noted that unless the consultant has a psychiatry background, the model has a less robust focus on behavioral health than does PCL.

Practice based models utilize general hospital staff and do not rely on expert addiction consultants

In Hospital-Based Opioid Treatment, generalists (e.g., hospitalists) or non-addiction specialists (e.g., infectious diseases) integrate MOUD as part of routine hospital care.84–86,92,93 Informants emphasized that necessary components for HBOT implementation include medical providers with basic MOUD knowledge and a Drug Enforcement Agency waiver to prescribe buprenorphine at discharge,18 availability of MOUD on hospital formularies, and hospital policies that support MOUD. Many HBOT programs rely on standard protocols and order sets.83 Informants noted that successful HBOT may rely on a strong clinical champion to garner hospital support, lead staff education, and drive quality improvement. Commonly, champions are hospital-based physicians who volunteer or have a small amount of protected time for program start-up. HBOT tends to focus on motivated patients who want MOUD, and this model does not generally incorporate motivational interviewing or other engagement strategies (e.g., peers). While HBOT can include protocol-driven naloxone prescribing, it does not typically include the broader range of harm reduction services common in ACS (e.g., tailored safer use education, fentanyl test strips). Increasingly, however, infectious disease physicians are addressing SUD-related population health gaps and expanding their scope of practice to include buprenorphine and infection-focused harm reduction education.84,92 While most HBOT models are physician-driven, examples of pharmacist-led HBOT also exist.89

Informants noted HBOT advantages over ACS include lower costs, normalizing MOUD delivery like any other medication, and scalability to hospitals lacking local addiction expertise. Informants noted that many HBOT champions seek training and mentoring through local,87 regional,109 and national outlets.99 One notable example of highly structured and intensive implementation support is the CA Bridge program, which has expanded HBOT statewide by supporting local hospital champions with intensive HBOT technical assistance and training, and by funding navigators.82,95

Informants described that HBOT has limited ability to perform formal OUD assessments, manage complex SUD (e.g., polysubstance, acute pain) or advocacy (e.g., cardiac valve surgery), and risks methadone or buprenorphine dosing errors. Many felt that HBOT may be a first step toward building an ACS, and HBOT can integrate more comprehensive supports. For example, one volunteer HBOT team partners with pharmacy, palliative care, and chaplaincy to expand their service scope.93

While most practice-based models focused on opioids, there are examples of Hospital-Based Alcohol Treatment (HBAT) that integrate medications for alcohol use disorder (MAUD) as part of routine hospital care.96 Informants hypothesized that because alcohol is legal and less stigmatized, and because MAUD has few side effects or risks, MAUD adoption may be easier and require less support from a clinical champion. Informants noted examples of nurse-led HBAT, where dedicated nurses make protocol-guided MAUD recommendations and make post-hospital treatment referrals.

In-reach

Community-Based In-Reach Though not well captured in the literature, informants described examples of community-based providers from primary care or specialty addiction care “reaching in” to offer hospital-based MOUD and follow-up. Informants noted that in-reach can support hospitalists who lack buprenorphine training or licensing,18 and may include MOUD continuation or initiation. In one published example, a community-based nurse came in to the hospital and supported methadone linkage and treatment linkage.97 In-reach requires little or no hospital financial investment, and community providers typically volunteer their time without billing an inpatient visit. In the examples we learned of—unlike ACS or individual consultant models—in-reach focuses on OUD, lacks capacity to support polysubstance use or complex medical or behavioral health needs, and focuses on patients with high treatment-readiness. Informants noted flexibility—including telehealth potential—as a model strength. Informants noted that in hospitals with no addiction expertise, in-reach could provide individual staff education and patient-level advocacy. Informants noted for the model to work, hospital providers have to recognize OUD and contact in-reach providers, which may fall through with high census or staff turnover. They also noted that insurance barriers can interfere with treatment linkage (e.g., if outpatient clinic does not accept all insurance), that there may be challenges if community providers are unable to obtain hospital credentials, that the intervention does not create systems change within hospitals, and that it depends on motivated outpatient providers willing to offer services for little-to-no reimbursement. Informants acknowledged a potential pitfall of hospital leaders thinking the model supports sufficient SUD care, where informants viewed this approach as a temporary solution to bigger need.

DISCUSSION

Addressing SUD in US hospitals will require diverse approaches across many years. We constructed a taxonomy that includes the six models that are most commonly found in current practice. Summarizing the characteristics of these models provides a framework to guide the adoption, expansion, and evaluation of hospital-based addiction care across diverse hospital settings. This study builds on prior work which characterized the ACS model,21 but did not contextualize it in a broader service delivery landscape or compared it to other hospital-based approaches addressing SUD.

The most comprehensive, intensive, and rigorously studied models are ACS, which manage high patient and system complexity. ACSs provide an important clinical, education, health system, and research platform. ACS, however, may not be feasible at all hospitals. PCLs are long-established services in many US hospitals, and offer unique strengths in their ability to address complex psychiatric needs. Though historically many have not addressed SUD as a central practice, they may be well positioned to expand their scope to include SUD and offer MOUD, MAUD, and community treatment referrals, much the way generalists have with HBOT/HBAT. The individual consultant model may be less resource intensive and easier to implement than ACS or PCL in settings with existing ambulatory addiction specialists. Further, they can serve as starting point on which to build more robust SUD services. Many ACSs started with an individual consultant and subsequently added broader supports including dedicated social workers, peers, and robust hospital-to-community pathways.

Practice-based models, HBOT and HBAT, are delivered by staff already involved in patients’ care who have expanded their scope to encompass MOUD and/or MAUD and post-hospital treatment linkage. These models often rely on protocols and order sets, and are not designed to manage complex SUD or co-occurring medical or behavioral health needs. Compared to addiction consult models, they are less resource intensive and may be more easily scaled-up. Community in-reach is the least intensive intervention, and may be well suited to hospitals with no internal champion or dedicated SUD resources.

While the taxonomy defines six unique models, models can co-exist or build on each other. For example, a large health system might deploy HBOT for patients interested in MOUD who have fewer psychosocial needs, while also offering an ACS for patients with complex withdrawal, polysubstance use, co-occurring pain, or complex illness such as endocarditis requiring valve replacement. Combining models this way may allow efficient resource allocation. Similarly, a rural hospital with little local addictions expertise could implement HBOT/HBAT and partner with telehealth addiction specialists to provide in-reach, affording patients MOUD/MAUD access during and after hospitalization, enriching community treatment options, and expanding access to addiction expertise among hospital staff. Conceptualizing hospital-based addiction care this way is similar to how palliative care has evolved. In many hospitals, generalists offer core palliative care elements such as basic code status discussions and symptom management, whereas specialists—often in interdisciplinary teams—support complex needs such as negotiating conflict within families, addressing existential distress, or managing refractory symptoms.110

Approaches combining SUD and infectious diseases care are emerging—particularly for people needing prolonged intravenous antibiotics.92,111 These approaches span SUD models, including ACS, individual consult, and HBOT, and highlight opportunities for interprofessional team-based care that bridge hospital and community settings.73,76,77,108,112 Though primarily observed in infectious diseases, specialists in hepatology113 or palliative care114,115 could consider similar models.

While these hospital-based models have great promise for improving addiction care, all require access to post-discharge SUD services for long-term effectiveness. Hospitalization is an important touchpoint, but the benefits of hospital-based intervention will only be fully realized if patients can receive ongoing care. Community treatment offerings may be limited due to geography (such as rural settings or areas without access to methadone or harm reduction programs), patient characteristics (such as insurance coverage), and systemic barriers (such as discrimination based on race/ethnicity).116–124

Our study has potential limitations. First, we describe a representative taxonomy rather than an exhaustive list. Second, models may have overlapping characteristics and variable ways of delivering specific components that are adapted to local settings and resources. Third, there are no studies comparing outcomes of different models, which limits the ability to provide recommendations regarding model effectiveness. Future research should explore this. Fourth, some models may exist that are not described in the published literature. We tried to address this by using key informants, but it is possible that our taxonomy misses some models. Most informants are from Western USA, which may have biased their input to reflect regional practice. Finally, little evidence describes model sustainability and the policy context needed to support and spread models. This is also an area for future research.

CONCLUSION

Hospital clinicians and administrators working to improve and expand addiction care need guidance on treatment models that best match local needs and resources. This taxonomy provides a set of models to consider, which can then be adapted and further developed in specific settings. For health services researchers, a taxonomy creates a framework to describe and compare interventions on implementation, effectiveness, and other outcomes. Finally, policy-makers can use a taxonomy to guide funding initiatives and generate guidelines and metrics that support SUD treatment standards across hospitals, measure hospital performance, and assess hospitals’ ability to meet needs of people with SUD. Given the high prevalence, morbidity, mortality,125 and cost of untreated SUD, all hospitals should be prepared to provide basic SUD care. This taxonomy can be the first step in developing a path toward broad adoption and implementation of hospital-based SUD care.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 83 kb)

(DOCX 114 kb)

(DOCX 20.4 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Susan Calcaterra, Richard Bottner, Dr Alena Balasanova, Dr Laura Marks, Sean Mahoney, Dr Marlene Martin, Dr Hannah Snyder, Dr Ashish Thakrar, Dr Andrea Kondracke, and other key informants for their expertise. We would like to thank Dr. Devan Kansagara and Dr. Christina Nicolaidis for the feedback on an earlier draft of this manuscript and the OHSU Research in Progress for help framing this study.

Funding

Grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, supported investigators’ time (UG1DA015815 HE, JM, NK, PTK), and R01DA045669 (JM).

Declarations

Competing Interests

Dr. Englander, Amy Jones, Dr. Krawczyk, Alisa Patten, Timothy Roberts, and Dr McNeely have no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Korthuis has no financial conflicts of interest, but serves as principal investigator for NIH-funded trials that accept donated study medications from Alkermes (extended-release naltrexone) and Indivior (sublingual buprenorphine).

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations Related To Opioid Abuse/Dependence And Associated Serious Infections Increased Sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winkelman TA, Admon LK, Jennings L, Shippee ND, Richardson CR, Bart G. Evaluation of amphetamine-related hospitalizations and associated clinical outcomes and costs in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183758. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capizzi J, Leahy J, Wheelock H, Garcia J, Strnad L, Sikka M, et al. Population-based trends in hospitalizations due to injection drug use-related serious bacterial infections, Oregon, 2008 to 2018. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fingar KR, Owens PL. Opioid-Related and Stimulant-Related Adult Inpatient Stays, 2012-2018. Statistical Brief#271. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2021. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb271-Stimulant-Opioid-Hospitalizations-2012-2018.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2021.

- 5.Suen LW, Makam AN, Snyder HR, Repplinger D, Kushel MB, Martin M, et al. National Prevalence of Alcohol and Other Substance Use Disorders Among Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations: NHAMCS. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;2021:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07069-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Priest KC, Lovejoy TI, Englander H, Shull S, McCarty D. Opioid Agonist Therapy During Hospitalization Within the Veterans Health Administration: a Pragmatic Retrospective Cohort Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2365–74. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05815-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Englander H, Dobbertin K, Lind BK, Nicolaidis C, Graven P, Dorfman C, et al. Inpatient addiction medicine consultation and post-hospital substance use disorder treatment engagement: a propensity-matched analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(12):2796–803. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05251-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, Nicolaidis C, Chan B, Velez C, et al. Planning and Designing the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) for Hospitalized Adults with Substance Use Disorder. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):339–42. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. "It's been an experience, a life learning experience": a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296–303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. "We've Learned It's a Medical Illness, Not a Moral Choice": Qualitative Study of the Effects of a Multicomponent Addiction Intervention on Hospital Providers' Attitudes and Experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(11):752–8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins D, Alla J, Nicolaidis C, Gregg J, Gullickson DJ, Patten A, et al. "If It Wasn't for Him, I Wouldn't Have Talked to Them": Qualitative Study of Addiction Peer Mentorship in the Hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;12:12. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King C, Collins D, Patten A, Nicolaidis C, Englander H. Trust in Hospital Physicians Among Patients With Substance Use Disorder Referred to an Addiction Consult Service: A Mixed-methods Study. J Addict Med. 2021;09:09. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Englander H, King C, Nicolaidis C, Collins D, Patten A, Gregg J, et al. Predictors of Opioid and Alcohol Pharmacotherapy Initiation at Hospital Discharge Among Patients Seen by an Inpatient Addiction Consult Service. J Addict Med. 2020;14(5):415–22. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, Rigotti NA. Inpatient Addiction Consultation for Hospitalized Patients Increases Post-Discharge Abstinence and Reduces Addiction Severity. J Gen Intern Med. 2017. 10.1007/s11606-017-4077-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.King C, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Priest KC, Englander H. Patterns of substance use before and after hospitalization among patients seen by an inpatient addiction consult service: A latent transition analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;118:108121. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimmel SD, Walley AY, Li Y, Linas BP, Lodi S, Bernson D, et al. Association of Treatment With Medications for Opioid Use Disorder With Mortality After Hospitalization for Injection Drug Use-Associated Infective Endocarditis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2016228. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi: 10.7326/m18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. H.R.2634, 106th Cong. 2nd Sess. (July 27, 2000).

- 19.covidence.org [internet]. Melbourne: Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software [cited 2021 Dec 7]. Available from: www.covidence.org.

- 20.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the Hospital in the 21st Century Opioid Overdose Epidemic: The Addiction Medicine Consult Service. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):104–12. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris MTH, Peterkin A, Bach P, Englander H, Lapidus E, Rolley T, et al. Adapting inpatient addiction medicine consult services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2021;16(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13722-021-00221-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Priest KC, McCarty D. Making the business case for an addiction medicine consult service: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):822. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4670-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enos G. Addiction consult services in hospitals show promise in facilitating ongoing care. Alcohol Drug Abuse Wkly. 2019;31(2):1–7. doi: 10.1002/adaw.32221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Priest KC, Englander H, McCarty D. "Now hospital leaders are paying attention": A qualitative study of internal and external factors influencing addiction consult services. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;110:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trowbridge P, Weinstein ZM, Kerensky T, Roy P, Regan D, Samet JH, et al. Addiction consultation services - Linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;79:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein ZM, Wakeman SE, Nolan S. Inpatient Addiction Consult Service: Expertise for Hospitalized Patients with Complex Addiction Problems. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):587–601. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Amico MJ, Walley AY, Cheng DM, Forman LS, Regan D, Yurkovic A, et al. Which patients receive an addiction consult? A preliminary analysis of the INREACH (INpatient REadmission post-Addiction Consult Help) study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;106:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kathuria H, Seibert RG, Cobb V, Weinstein ZM, Gowarty M, Helm ED, et al. Patient and Physician Perspectives on Treating Tobacco Dependence in Hospitalized Smokers With Substance Use Disorders: A Mixed Methods Study. J Addict Med. 2019;13(5):338–45. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinstein ZM, Cheng DM, D'Amico MJ, Forman LS, Regan D, Yurkovic A, et al. Inpatient addiction consultation and post-discharge 30-day acute care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;213:108081. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy PJ, Price R, Choi S, Weinstein ZM, Bernstein E, Cunningham CO, et al. Shorter outpatient wait-times for buprenorphine are associated with linkage to care post-hospital discharge. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;224:108703. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wakeman SE, Kane M, Powell E, Howard S, Shaw C, Kehoe L, et al. A hospital-wide initiative to redesign substance use disorder care: Impact on pharmacotherapy initiation. Subst Abus. 2020:1-8. 10.1080/08897077.2020.1846664 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Wakeman SE, Kane M, Powell E, Howard S, Shaw C, Regan S. Impact of Inpatient Addiction Consultation on Hospital Readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;22:22. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05966-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wakeman SE, Kanter GP, Donelan K. Institutional Substance Use Disorder Intervention Improves General Internist Preparedness, Attitudes, and Clinical Practice. J Addict Med. 2017;11(4):308–14. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wakeman SE, Rigotti NA, Herman GE, Regan S, Chang Y, Snow R, et al. The effectiveness of post-discharge navigation added to an inpatient addiction consultation for patients with substance use disorder; a randomized controlled trial. Subst Abus. 2020:1-8. 10.1080/08897077.2020.1809608 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.McNeely J, Troxel AB, Kunins HV, Shelley D, Lee JD, Walley A, et al. Study protocol for a pragmatic trial of the Consult for Addiction Treatment and Care in Hospitals (CATCH) model for engaging patients in opioid use disorder treatment. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2019;14(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13722-019-0135-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Englander H, Mahoney S, Brandt K, Brown J, Dorfman C, Nydahl A, et al. Tools to Support Hospital-Based Addiction Care: Core Components, Values, and Activities of the Improving Addiction Care Team. J Addict Med. 2019;13(2):85–9. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King C, Vega T, Button D, Nicolaidis C, Gregg J, Englander H. Understanding the impact of the SARS-COV-2 pandemic on hospitalized patients with substance use disorder. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0247951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, Rabinowitz M, Phoutrides E, Nicolaidis C. "We've Learned It's a Medical Illness, Not a Moral Choice": Qualitative Study of the Effects of a Multicomponent Addiction Intervention on Hospital Providers' Attitudes and Experiences. J Hosp Med. 2018. 10.12788/jhm.2993 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Englander H, Gregg J, Gullickson J, Cochran-Dumas O, Colasurdo C, Alla J, et al. Recommendations for integrating peer mentors in hospital-based addiction care. Subst Abus. 2020;41(4):419–24. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2019.1635968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King C, Collins D, Patten A, Nicolaidis C, Englander H. Trust in Hospital Physicians Among Patients With Substance Use Disorder Referred to an Addiction Consult Service: A Mixed-methods Study. J Addict Med. 2021. 10.1097/adm.0000000000000819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Button D, Hartley J, Robbins J, Levander XA, Smith NJ, Englander H. Low-dose Buprenorphine Initiation in Hospitalized Adults With Opioid Use Disorder: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. J Addict Med. 2021;17:17. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson HM, Hill K, Jadhav R, Webb TA, Pollack M, Karnik N. The Substance Use Intervention Team: A Preliminary Analysis of a Population-level Strategy to Address the Opioid Crisis at an Academic Health Center. J Addict Med. 2019;13(6):460–3. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson HM, Faig W, VanKim NA, Sharma B, Afshar M, Karnik NS. Differences in length of stay and discharge destination among patients with substance use disorders: The effect of Substance Use Intervention Team (SUIT) consultation service. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0239761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tran TH, Swoboda H, Perticone K, Ramsey E, Thompson H, Hill K, et al. The substance use intervention team: A hospital-based intervention and outpatient clinic to improve care for patients with substance use disorders. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):345–53. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin M, Snyder HR, Coffa D, Steiger S, Clement JP, Ranji SR, et al. Time to ACT: launching an Addiction Care Team (ACT) in an urban safety-net health system. BMJ open qual. 2021;10(1). 10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Calcaterra SL, McBeth L, Keniston AM, Burden M. The Development and Implementation of a Hospitalist-Directed Addiction Medicine Consultation Service to Address a Treatment Gap. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;19:19. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06849-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nordeck CD, Welsh C, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Cohen A, O'Grady KE, et al. Rehospitalization and substance use disorder (SUD) treatment entry among patients seen by a hospital SUD consultation-liaison service. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gryczynski J, Nordeck CD, Welsh C, Mitchell SG, O'Grady KE, Schwartz RP. Preventing Hospital Readmission for Patients With Comorbid Substance Use Disorder: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2021;06:06. doi: 10.7326/M20-5475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weintraub E, Weintraub D, Dixon L, Delahanty J, Gandhi D, Cohen A, et al. Geriatric patients on a substance abuse consultation service. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(3):337–42. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200205000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Castellucci M. Reducing risk of readmission by talking about substance abuse before discharge. Modern Healthcare. 2018;48(48):38. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kilwein TM, Brown S, Gaffaney M, Farrar J. Bridging the Gap: Can Group Interventions Assist Addiction Consult Services in Providing Integrated, Comprehensive Healthcare for Patients Hospitalized for Opioid-Related Infections? J Clin Psychol Med. 2020;06:06. doi: 10.1007/s10880-020-09712-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marcovitz DE, Sidelnik SA, Smith MP, Suzuki J. Motivational Interviewing on an Addiction Consult Service: Pearls, Perils, and Educational Opportunities. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(3):352–5. doi: 10.1007/s40596-020-01196-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allegheny Health Network [Internet]. Center for Inclusion Health: Addiction Medicine; c2021 [cited 2021 Dec 7]. Available from: https://www.ahn.org/services/medicine/center-for-inclusion-health/addiction-medicine.html.

- 55.Suzuki J, DeVido J, Kalra I, Mittal L, Shah S, Zinser J, et al. Initiating buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized patients with opioid dependence: A case series. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):10–4. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suzuki J, Meyer F, Wasan AD. Characteristics of medical inpatients with acute pain and suspected non-medical use of opioids. Am J Addict. 2013;22(5):515–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suzuki J. Medication-assisted treatment for hospitalized patients with intravenous-drug-use related infective endocarditis. Am J Addict. 2016;25(3):191–4. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suzuki J, Robinson D, Mosquera M, Solomon DA, Montgomery MW, Price CD, et al. Impact of Medications for Opioid Use Disorder on Discharge Against Medical Advice Among People Who Inject Drugs Hospitalized for Infective Endocarditis. Am J Addict. 2020;29(2):155–9. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murphy MK, Chabon B, Delgado A, Newville H, Nicolson SE. Development of a substance abuse consultation and referral service in an academic medical center: challenges, achievements and dissemination. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009;16(1):77–86. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wai JM, Aloezos C, Mowrey WB, Baron SW, Cregin R, Forman HL. Using clinical decision support through the electronic medical record to increase prescribing of high-dose parenteral thiamine in hospitalized patients with alcohol use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;99:117–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bourgeois JA, Wegelin JA, Servis ME, Hales RE. Psychiatric Diagnoses of 901 Inpatients Seen by Consultation-Liaison Psychiatrists at an Academic Medical Center in a Managed Care Environment. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2005;46(1):47–57. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hassamal S, Goldenberg M, Ishak W, Haglund M, Miotto K, Danovitch I. Overcoming Barriers to Initiating Medication-assisted Treatment for Heroin Use Disorder in a General Medical Hospital: A Case Report and Narrative Literature Review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(3):221–9. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Muramatsu RS, Goebert D, Sweeny HW, Takeshita J. A descriptive study of a unique multi-ethnic consultation-liaison psychiatry service in Honolulu. Hawaii. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2008;38(4):425–35. doi: 10.2190/PM.38.4.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grant JE, Meller W, Urevig B. Changes in psychiatric consultations over ten years. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(5):261–5. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(01)00159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pezzia C, Pugh JA, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK. Psychiatric consultation requests by inpatient medical teams: an observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):336. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martino S, Zimbrean P, Forray A, Kaufman JS, Desan PH, Olmstead TA, et al. Implementing Motivational Interviewing for Substance Misuse on Medical Inpatient Units: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2520–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05257-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dilts SL, Jr, Mann N, Dilts JG. Accuracy of referring psychiatric diagnosis on a consultation-liaison service. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(5):407–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.5.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marcovitz DE, Maruti S, Kast KA, Suzuki J. The Use of Therapeutic Metaphor on an Addiction Consult Service. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2021;62(1):102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brigham and Women's Hospital [Internet]. Boston: Division of Addiction Psychiatry; c2021 [cited 2021 Dec 7]. Available from: https://www.brighamandwomens.org/psychiatry/brigham-psychiatric-specialties/addiction-psychiatry.

- 70.Ray V, Waite MR, Spexarth FC, Korman S, Berget S, Kodali S, et al. Addiction Management in Hospitalized Patients With Intravenous Drug Use-Associated Infective Endocarditis. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(6):678–87. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bhatraju EP, Ludwig-Barron N, Takagi-Stewart J, Sandhu HK, Klein JW, Tsui JI. Successful engagement in buprenorphine treatment among hospitalized patients with opioid use disorder and trauma. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;215:108253. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Beieler AM, Klein JW, Bhatraju E, Iles-Shih M, Enzian L, Dhanireddy S. Evaluation of Bundled Interventions for Patients With Opioid Use Disorder Experiencing Homelessness Receiving Extended Antibiotics for Severe Infection. Open forum infect. 2021;8(6):ofab285. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eaton EF, Lee RA, Westfall AO, Mathews RE, McCleskey B, Paddock CS, et al. An Integrated Hospital Protocol for Persons With Injection-Related Infections May Increase Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Use but Challenges Remain. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Suppl 5):S499–s505. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eaton EF, Mathews RE, Lane PS, Paddock CS, Rodriguez JM, Taylor BB, et al. A 9-Point Risk Assessment for Patients Who Inject Drugs and Require Intravenous Antibiotics: Focusing Inpatient Resources on Patients at Greatest Risk of Ongoing Drug Use. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(6):1041–3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eaton EF, Westfall AO, McClesky B, Paddock CS, Lane PS, Cropsey KL, et al. In-Hospital Illicit Drug Use and Patient-Directed Discharge: Barriers to Care for Patients With Injection-Related Infections. Open forum infect. 2020;7(3):ofaa074. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fanucchi LC, Walsh SL, Thornton AC, Lofwall MR. Integrated outpatient treatment of opioid use disorder and injection-related infections: A description of a new care model. Prev Med. 2019;128:105760. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fanucchi LC, Walsh SL, Thornton AC, Nuzzo PA, Lofwall MR. Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy Plus Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder and Severe Injection-related Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(6):1226–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Marks LR, Munigala S, Warren DK, Liang SY, Schwarz ES, Durkin MJ. Addiction medicine consultations reduce readmission rates for patients with serious infections from Opioid Use Disorder. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;68(11):1935–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marks LR, Liang SY, Muthulingam D, Schwarz ES, Liss DB, Munigala S, et al. Evaluation of Partial Oral Antibiotic Treatment for Persons Who Inject Drugs and Are Hospitalized With Invasive Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(10):e650–e6. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Marks LR, Munigala S, Warren DK, Liss DB, Liang SY, Schwarz ES, et al. A Comparison of Medication for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment Strategies for Persons Who Inject Drugs With Invasive Bacterial and Fungal Infections. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Suppl 5):S513–S20. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Manwell LB, Mindock S, Mundt M. Patient reaction to traumatic injury and inpatient AODA consult: Six-month follow-up. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28(1):41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Snyder H, Kalmin MM, Moulin A, Campbell A, Goodman-Meza D, Padwa H, et al. Rapid Adoption of Low-Threshold Buprenorphine Treatment at California Emergency Departments Participating in the CA Bridge Program. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78(6):759–772. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang SJ, Wade E, Towle J, Hachey T, Rioux J, Samuels O, et al. Effect of Inpatient Medication-Assisted Therapy on Against-Medical-Advice Discharge and Readmission Rates. Am J Med. 2020;133(11):1343–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rapoport AB, Rowley CF. Stretching the scope - becoming frontline addiction-medicine providers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(8):705–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1706492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ivey N, Clifton DC. Tales from the frontlines: An alarming rise in hospitalizations related to opioid use disorder in the era of COVID-19. J Opioid Manag. 2021;17(1):5–7. doi: 10.5055/jom.2021.0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thakrar AP, Furfaro D, Keller S, Graddy R, Buresh M, Feldman L. A Resident-Led Intervention to Increase Initiation of Buprenorphine Maintenance for Hospitalized Patients With Opioid Use Disorder. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(6):339–44. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beauchamp GA, Laubach LT, Esposito SB, Yazdanyar A, Roth P, Lauber P, et al. Implementation of a Medication for Addiction Treatment (MAT) and Linkage Program by Leveraging Community Partnerships and Medical Toxicology Expertise. J Med Toxicol. 2021;17(2):176–84. doi: 10.1007/s13181-020-00813-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sweeney S, Coble K, Connors E, Rebbert-Franklin K, Welsh C, Weintraub E. Program development and implementation outcomes of a statewide addiction consultation service: Maryland Addiction Consultation Service (MACS). Subst Abus. 2020:1-8. 10.1080/08897077.2020.1803179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 89.Andrews LB, Bridgeman MB, Dalal KS, Abazia D, Lau C, Goldsmith DF, et al. Implementation of a pharmacist-driven pain management consultation service for hospitalised adults with a history of substance abuse. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(12):1342–9. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tierney HR, Rowe CL, Coffa DA, Sarnaik S, Coffin PO, Snyder HR. Inpatient Opioid Use Disorder Treatment by Generalists is Associated With Linkage to Opioid Treatment Programs After Discharge. J Addict Med. 2021;02:02. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kays LB, Steltenpohl ED, McPheeters CM, Frederick EK, Bishop LB. Initiation of Buprenorphine/Naloxone on Rates of Discharge Against Medical Advice. Hosp Pharmacy. 2020:0018578720985439. 10.1177/0018578720985439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Serota DP, Barocas JA, Springer SA. Infectious Complications of Addiction: A Call for a New Subspecialty Within Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Disease. 2019;70(5):968–72. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Christian N, Bottner R, Baysinger A, Boulton A, Walker B, Valencia V, et al. Hospital Buprenorphine Program for Opioid Use Disorder Is Associated With Increased Inpatient and Outpatient Addiction Treatment. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(6):345–8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bottner R, Moriates C, Tirado C. The Role of Hospitalists in Treating Opioid Use Disorder. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 95.cabridge.org [Internet]. Oakland: California Department of Health Care Services. CA Bridge: Transforming Addiction Treatment. c2021 [cited 2021 Dec 7]. Available from: https://cabridge.org/.

- 96.Wei J, Defries T, Lozada M, Young N, Huen W, Tulsky J. An inpatient treatment and discharge planning protocol for alcohol dependence: efficacy in reducing 30-day readmissions and emergency department visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):365–70. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2968-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shanahan CW, Beers D, Alford DP, Brigandi E, Samet JH. A transitional opioid program to engage hospitalized drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):803–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1311-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.boulder.care [internet]. Portland, Or: Boulder Care, Inc. c2021 [cited 2021 Dec 7]. Available from: https://boulder.care.

- 99.Englander H, Priest KC, Snyder H, Martin M, Calcaterra S, Gregg J. A call to action: hospitalists' role in addressing substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(3):E1–e4. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.French R, Aronowitz SV, Brooks Carthon JM, Schmidt HD, Compton P. Interventions for hospitalized medical and surgical patients with opioid use disorder: A systematic review. Subst Abus. 2021:1-13. 10.1080/08897077.2021.1949663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.Weimer MB, Falker CG, Seval N, Golden M, Hull SC, Geirsson A, et al. The Need for Multidisciplinary Hospital Teams for Injection Drug Use-Related Infective Endocarditis. J Addict Med. 2021. 10.1097/adm.0000000000000916 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 102.Mee-Lee D. The ASAM Criteria: Treatment Criteria for Addictive, Substance-related, and Co-occurring Conditions: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2013.

- 103.Perera R, Stephan L, Appa A, Giuliano R, Hoffman R, Lum P, et al. Meeting people where they are: implementing hospital-based substance use harm reduction. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12954-022-00594-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Buchheit BM, Wheelock H, Lee A, Brandt K, Gregg J. Low-barrier buprenorphine during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid transition to on-demand telemedicine with wide-ranging effects. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2021;131:108444. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McNeely J, Schatz D, Olfson M, Appleton N, Williams AR. How Physician Workforce Shortages Are Hampering the Response to the Opioid Crisis. Psychiatr Serv. 2021:appips202000565. 10.1176/appi.ps.202000565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 106.Kathol RG, Kunkel EJ, Weiner JS, McCarron RM, Worley LL, Yates WR, et al. Psychiatrists for medically complex patients: bringing value at the physical health and mental health/substance-use disorder interface. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(2):93–107. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Marcovitz D, Nisavic M, Bearnot B. Staffing an addiction consult service: Psychiatrists, internists, or both? General Hospital Psychiatry. 2019;57:41–3. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Marks LR, Munigala S, Warren DK, Liang SY, Schwarz ES, Durkin MJ. Addiction Medicine Consultations Reduce Readmission Rates for Patients With Serious Infections From Opioid Use Disorder. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(11):1935–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Englander H, Patten A, Lockard R, Muller M, Gregg J. Spreading Addictions Care Across Oregon's Rural and Community Hospitals: Mixed-Methods Evaluation of an Interprofessional Telementoring ECHO Program. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(1):100–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06175-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Appa A, Barocas Joshua A. Can I Safely Discharge a Patient with a Substance Use Disorder Home with a Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter? NEJM Evidence. 2022;1(2):EVIDccon2100012. doi: 10.1056/EVIDccon2100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sikka MK, Gore S, Vega T, Strnad L, Gregg J, Englander H. "OPTIONS-DC", a feasible discharge planning conference to expand infection treatment options for people with substance use disorder. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):772. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06514-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Patel K, Maguire E, Chartier M, Akpan I, Rogal S. Integrating Care for Patients With Chronic Liver Disease and Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders. Fed Pract. 2018;35(Suppl 2):S14–S23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ebenau A, Dijkstra B, Stal-Klapwijk M, Ter Huurne C, Blom A, Vissers K, et al. Palliative care for patients with a substance use disorder and multiple problems: a study protocol. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12904-018-0351-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Witham G, Galvani S, Peacock M. End of life care for people with alcohol and drug problems: Findings from a Rapid Evidence Assessment. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27(5):e637–e50. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Stein BD, Dick AW, Sorbero M, Gordon AJ, Burns RM, Leslie DL, et al. A population-based examination of trends and disparities in medication treatment for opioid use disorders among Medicaid enrollees. Subst Abus. 2018;39(4):419–25. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1449166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Barton H, Hutnich J. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General, Washington, DC). Geographic Disparities Affect Access to Buprenorphine Services for Opioid Use Disorder. Report in Brief. 2020 January. Report No. OEI-12-17-00240. [cited 2021 Jan 8]. Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-12-17-00240.asp.

- 118.Gregg JL. Dying To Access Methadone. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1225–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Andrilla CHA, Moore TE, Patterson DG, Larson EH. Geographic Distribution of Providers With a DEA Waiver to Prescribe Buprenorphine for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: A 5-Year Update. J Rural Health. 2019;35(1):108–12. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cummings JR, Wen H, Ko M, Druss BG. Race/ethnicity and geographic access to Medicaid substance use disorder treatment facilities in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):190–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.James K, Jordan A. The Opioid Crisis in Black Communities. J Law Med Ethics. 2018;46(2):404–21. doi: 10.1177/1073110518782949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hansen HB, Siegel CE, Case BG, Bertollo DN, DiRocco D, Galanter M. Variation in use of buprenorphine and methadone treatment by racial, ethnic, and income characteristics of residential social areas in New York City. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2013;40(3):367–77. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9341-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lagisetty PA, Ross R, Bohnert A, Clay M, Maust DT. Buprenorphine Treatment Divide by Race/Ethnicity and Payment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):979–81. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Hoeppner BB, Terplan M, Hansen H, Bernson D, et al. Assessment of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Medication to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Among Pregnant Women in Massachusetts. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e205734. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.King C, Cook R, Korthuis PT, Morris CD, Englander H. Causes of Death in the 12 months After Hospital Discharge Among Patients With Opioid Use Disorder. J Addict Med. 2021. 10.1097/adm.0000000000000915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 83 kb)

(DOCX 114 kb)

(DOCX 20.4 kb)