Abstract

Background

Inappropriate polypharmacy, prevalent among older patients, is associated with substantial harms.

Objective

To develop measures of high-risk polypharmacy and pilot test novel electronic health record (EHR)-based nudges grounded in behavioral science to promote deprescribing.

Design

We developed and validated seven measures, then conducted a three-arm pilot from February to May 2019.

Participants

Validation used data from 78,880 patients from a single large health system. Six physicians were pre-pilot test environment users. Sixty-nine physicians participated in the pilot.

Main Measures

Rate of high-risk polypharmacy among patients aged 65 years or older. High-risk polypharmacy was defined as being prescribed ≥5 medications and satisfying ≥1 of the following high-risk criteria: drugs that increase fall risk among patients with fall history; drug-drug interactions that increase fall risk; thiazolidinedione, NSAID, or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker in heart failure; and glyburide, glimepiride, or NSAID in chronic kidney disease.

Interventions

Physicians received EHR alerts when renewing or prescribing certain high-risk medications when criteria were met. One practice received a “commitment nudge” that offered a chance to commit to addressing high-risk polypharmacy at the next visit. One practice received a “justification nudge” that asked for a reason when high-risk polypharmacy was present. One practice received both.

Key Results

Among 55,107 patients 65 and older prescribed 5 or more medications, 6256 (7.9%) had one or more high-risk criteria. During the pilot, the mean (SD) number of nudges per physician per week was 1.7 (0.4) for commitment, 0.8 (0.5) for justification, and 1.9 (0.5) for both interventions. Physicians requested to be reminded to address high-risk polypharmacy for 236/833 (28.3%) of the commitment nudges and acknowledged 441 of 460 (95.9%) of justification nudges, providing a text response for 187 (40.7%).

Conclusions

EHR-based measures and nudges addressing high-risk polypharmacy were feasible to develop and implement, and warrant further testing.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-07296-1.

KEY WORDS: polypharmacy, electronic health records, high-risk geriatric polypharmacy electronic clinical quality measures, behavioral economics, clinical decision support

Polypharmacy is highly prevalent among older adults in the USA and is associated with adverse drug events (ADEs), higher costs, falls, and increased mortality.1–4 There are recommendations for high-risk polypharmacy deprescribing.5–8 However, to date, there has been little convincing evidence of effective interventions to reduce high-risk polypharmacy and to improve health outcomes.9,10 Interventions such as education, traditional interruptive computerized clinical decision support, and academic detailing have implicitly relied on a model of decision making in which clinicians are rational agents who carefully weigh benefits against harms and are motivated to provide the best care possible to their patients.9,11–15 Such interventions have varying effectiveness, can be costly, difficult to scale (because they require providing academic detailing, hiring clinical pharmacists, or implementing multidisciplinary teams),9,16 and may not fit into workflows (e.g., mailed polypharmacy reports from health plans, that arrive at times not conducive to medical decision making).11,15,17 Furthermore, current payment models in the USA provide little incentive to reduce high-risk polypharmacy.

Behavioral economic interventions referred to as “nudges” are manipulations of conditions under which decisions are made that attempt to steer individuals towards particular courses of action while preserving their liberty to choose what to do.18 They have been used successfully to improve clinicians’ prescribing behavior.19–21 Nudges recognize that clinicians make quick decisions that are influenced by their environments, especially via electronic health records (EHRs). Nudges are promising strategies to reduce high-risk polypharmacy. Nudges can be integrated into existing clinical workflows and are scalable, assuming they are acceptable to clinicians and do not force providers to respond with a complex action in the middle of their other tasks. The primary objectives of this study were the following: (1) to develop electronic clinical quality measures (eCQMs) to assess for high-risk polypharmacy among older outpatients, (2) to develop clinical decision support nudges to be used in a commercial EHR, and (3) to conduct a pilot test of these methods in primary care practice.

METHODS

Setting and Data Sources

For eCQM and decision support development, we used data from patients aged 65 years and older evaluated in any of 60 outpatient primary care sites from a large health system using a single instance of a commercial EHR (Epic, Verona, WI). Three primary care sites with 69 physicians participated in the pilot conducted from February 12 to May 31, 2019. Northwestern University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Measure Development

We produced explicit measures of high-risk polypharmacy to be used with EHR data. We selected these measures after review of three sources: the Beers Criteria, the Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (STOPP) Criteria, and the National Action Plan for Adverse Drug Event Detection.5,8,22

The 2015 Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults were published by the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Panel.22 This panel used a modified Delphi method to grade the evidence on drug risks and reach consensus on identifying potentially inappropriate, high-risk medications among older adults outside the palliative or hospice setting. Multiple studies have found associations between medication regimens that meet Beers criteria (in their earlier versions) and poor health outcomes, including falls, confusion, and mortality.23,24 Beers criteria have served as the basis for prior interventions targeting geriatric polypharmacy.9 The 2015 Beers criteria are specified in five groups: (a) medications to avoid for many or most older adults (defined by individual drug); (b) medications for older adults with specific diseases or syndromes to avoid (defined by individual drug-disease combination); (c) potentially harmful medications (defined by individual drug); (d) certain drug–drug interactions (defined by combinations of non-anti-infective drugs); and (e) medications (other than anti-infective agents) to avoid or the dosage of which should be adjusted based on the individual’s kidney function (defined by individual drug and creatinine clearance).

Version 2 of the STOPP criteria were updated by an expert panel in 2015 using a Delphi consensus method.5 Prior research has found that the STOPP criteria are significantly associated with ADEs25 and have been used in previous pharmacist-based interventions that reduced ADEs.26 We examined medications targeted by the National Action Plan for Adverse Drug Event Prevention.8 This National Action Plan, published in 2014 by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, identified 3 medication classes as initial targets for ADE prevention: anticoagulants (primary ADE of concern: bleeding), diabetes agents (primary ADE of concern: hypoglycemia), and opioids (primary ADE of concern: accidental overdoses/oversedation/respiratory depression).

From these criteria and with input from experts in ADEs (JTH, SH), geriatric pharmacology (JTH, TAR), deprescribing and informatics (SH, SDP, DM), and performance measurement (MWF, SDP), we constructed seven electronic clinical quality measures to detect the presence of high-risk polypharmacy from patients’ medication lists, diagnoses, and other data elements within an EHR. The initial step involved de-duplicating medications with multiple entries and eliminating non-systemic medications. Measures indicate high-risk polypharmacy when the patient was prescribed at least five different systemic medications, certain clinical criteria, or certain drug–drug combinations. The measures are listed in Table 1, and their technical specifications are provided in the electronic supplementary material.

Table 1.

Electronic Clinical Quality Measures of High-Risk Polypharmacy in the Elderly

| Measure | Criteria* | Sources | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| CKD-glyburide/glimepiride interaction | Prescribed glyburide or glimepiride among individuals with estimated GFR† <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | National Action Plan8 | CKD stage 3 and prescribed glyburide |

| CKD-NSAID interaction | Prescribed a NSAID among individuals with estimated GFR† <30 ml/min/1.73m2 | Beers; STOPP | CKD stage 4 and prescribed naproxen |

| Fall condition–drug interaction | Prescribed ≥1 medication associated with falls among individuals with prior fall or identified as at risk for fall | Beers6,22; STOPP5 | Prior hip fracture and prescribed amitriptyline |

| Fall drug–drug interaction | Prescribed ≥3 medications associated with falls | Beers; STOPP | Prescribed gabapentin, zolpidem, and fluoxetine |

| HF-non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker interaction | Prescribed a non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker among individuals with HF with reduced ejection fraction | Beers; STOPP | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and prescribed verapamil |

| HF-NSAID interaction | Prescribed a NSAID among individuals with HF | Beers | Heart failure and prescribed diclofenac |

| HF-thiazolidinedione interaction | Prescribed a thiazolidinedione among individuals with HF | Beers; STOPP | Heart failure and prescribed pioglitazone |

HF heart failure; STOPP Screening Tool of Older Person’s potentially inappropriate Prescription; CKD chronic kidney disease; NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

*All measure criteria included the prescription of five or more systemic medications

†eGFR calculated by Cockcroft-Gault equation34 to prevent over estimation of creatinine clearance in older people35

Measure Validation

We specified the value sets and logic for each quality measure and applied them to EHR data from 78,880 patients aged 65 and older within the Northwestern Medicine system who had one or more primary care visits during 2017 and 2018. Of these patients, 55,107 (70%) had five or more medications on their active outpatient medication lists. To determine the number of medications at a point in time, we did the following: (1) determined all ordered outpatient medications with a start date on or before the measurement date with an end date that was blank or after the measurement date, (2) discarded medications not given by a systemic route, (3)de-duplicated medications by simple generic name if they appeared more than once, and (4) counted the remaining medications. Historical or patient-reported medications were not included. To determine if the automated queries were accurate and were yielding the expected results, we randomly sampled records for patients who did and did not meet each measurement criteria used in any of the measures. A physician reviewer (SDP) examined the patient records in the EHR and determined the value for these criteria based on chart review. In cases where the query results did not match the chart findings, the physician reviewer and the analyst worked together to identify the source of the discrepancy, and the analyst modified the query logic to correct it. We then sampled additional patients and performed physician review until there were no longer discrepancies present. In this process, we conducted chart reviews on 20 to 90 charts per data element. We determined the rates of each measure in this population.

Interventions

Decision Support Nudges Development

We convened a multidisciplinary team to inform intervention design to be used to attempt to curb the initiation or continuation of high-risk polypharmacy. This included experts in persuasion, social influence, and decision theory (CRF, NJG, JND); clinician behavior change (JAL, SDP, MWF); medical informatics (SDP, DM); and primary care (JAL, SDP, MWF). We developed a commitment nudge and a justification nudge to address high-risk polypharmacy.

Commitment Nudge

The commitment intervention leverages the fact that many medication renewals occur outside of visits, but deprescribing discussions with patients typically occur during visits. The commitment nudge is an EHR alert triggered when a clinician renews one or more medications for a patient aged 65 or greater who meets criteria for high-risk polypharmacy. Medication renewal requests are often handled through a physician’s EHR inbox asynchronously—outside the context of face-to-face patient visits. Nearly all commercial EHRs have inbox-like features for medication renewals.

We hypothesized that clinicians (who would rather not be working after-hours) would address medication renewal requests as quickly as possible, taking the easiest cognitive pathway, which is to simply renew the medications. By contrast, professional norms for not renewing a chronic medication generally require the clinician to communicate with the patient to discuss key questions: Is the medication still necessary? Is it achieving the desired effect? Do benefits outweigh risks? For clinicians, having such a conversation before deciding whether to renew is much more difficult than just renewing the medication without discussion. Alternative paths, such as issuing a brief renewal and manually setting up a reminder to call the patient or discuss polypharmacy at the next visit, require more time and effort.

When triggered, the commitment nudge offered the clinician a novel choice designed to be an attractive and simple alternative to status quo renewal of the requested medication. This new choice option alerted the clinician to the high-risk polypharmacy and enabled the clinician to set a reminder to discuss polypharmacy at the patient’s next visit. This commitment to a future discussion could be shared with the patient at the clinician’s discretion via the EHR patient portal or added to the after-visit summary if the commitment was made during an office visit. When the clinician saw the patient during the next encounter, the alert the clinician set for him or herself in the past would appear. In essence, after being “snoozed” by the clinician, the alarm would sound again—the clinician was confronted with their prior commitment—hopefully at a time more conducive to reducing the high-risk polypharmacy. Moreover, both the patient and the clinician would know that such a conversation was recommended by the clinician in the past.

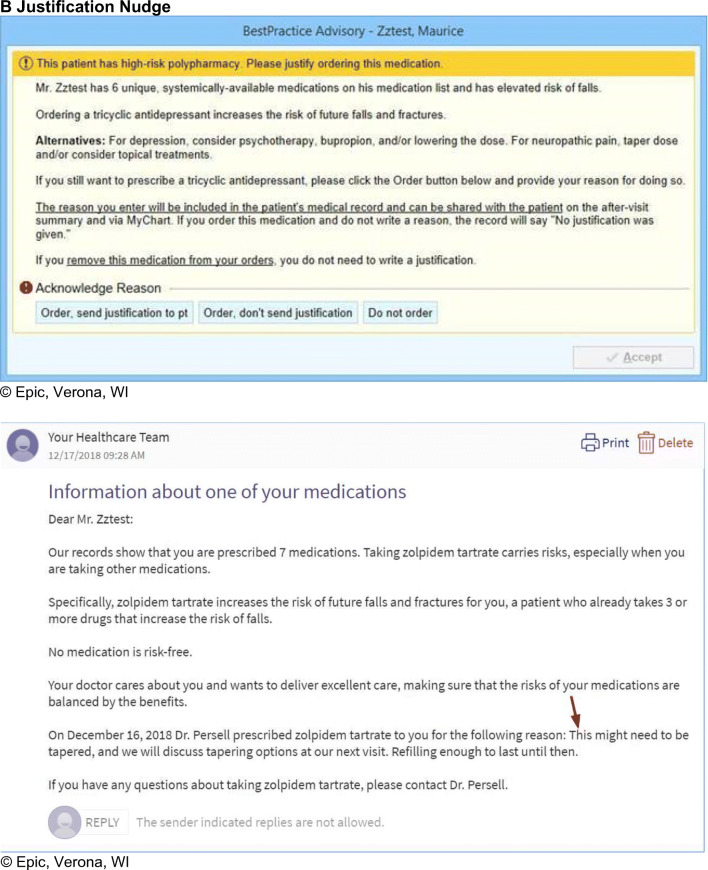

Justification Nudge

The justification nudge was an EHR alert triggered when a clinician began to renew or newly prescribe a medication that caused a high-risk criterion to be fulfilled (i.e., a medication meeting any of the criteria for the measures listed in Table 1). Like a justification nudge used previously by our group to address antibiotic overprescribing,18,33,52 this alert informed the clinician of the high-risk nature of the prescription and requested a free-text justification for starting or renewing the medication. This written justification appeared in the chart as a “justification note” that other chart users could see. If no justification was given, the default text “No justification was given” appeared in the note. In addition, the clinician could decide whether to share their written justification with the patient. This sharing occurred via an EHR patient portal message (for inbox renewals) and/or notation in the after-visit summary (for medications prescribed during a visit). This sharing feature was intended to intensify the pressure to behave in a way that the patient would approve (i.e., to discontinue high-risk medications that could not be well-justified). The clinician could avoid the justification request altogether (with no default justification note generated) by not prescribing or renewing the medication that triggered the justification nudge.

Additional description of the nudge content and the underlying rationale for the selected content are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Rationale for and Description of Clinical Decision Support Interventions

| Potential driver of clinician prescribing decisions | Behavioral economics/social psychology principle | Nudge | Examples of language from CDS interventions presented to clinicians |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underestimation of harm from high-risk polypharmacy | Making potential downstream harms more available makes continuing high-risk polypharmacy appear risky | Commitment and Justification |

“This patient has high-risk polypharmacy.” “Amitriptyline and hydrocodone increase the risk of falls…” |

| Effort required to reduce or stop prescription is much greater than effort to renew. Renewal requests may occur when patient not present | Committing to an action in the future may appear less burdensome than acting in the present. Efforts to be done in the future are discounted. Action postponed to time when patient is present | Commitment | “Would you like to set a reminder to discuss high-risk polypharmacy at your next visit…” |

| Other topics compete for time during future office visit. No change is easier than making a change | People feel compelled to honor their prior commitments | Commitment | “On June 2, 2021 you indicated that you would like to discuss high-risk polypharmacy at today’s visit.” |

| Patient reminders may make clinician feel accountable to their patient to take action | Commitment | “…we will also send Mr. X a message… | |

| Justification reason included in chart and visible to peers and patient may provoke sense of accountability and draw on reputational concerns | Justification | “The reason you enter will be included in the patient’s medical record and can be shared with the patient on the after-visit summary and via Mychart…” |

User Testing

We performed user testing of both nudges in an EHR test environment (using pre-programmed, realistic patient scenarios) with six primary care physicians, solicited their feedback, and modified the nudges accordingly. These modifications included altering nudge wording for clarity, changing the exact timing of nudge firing to better match clinical workflow, and allowing prescribers to decide whether to share their justifications with patients via EHR patient portal and after-visit summary.

Conduct of the Pilot

The pilot was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier: NCT03791580. We approached the leadership of three primary care practices and obtained their permission to include their practices in the pilot. We oriented physicians to the intervention content through brief presentations at practice meetings and by sending each physician an email link to participate in a brief educational online module that covered the clinical content addressed by these alerts and introduced the appearance and function of the clinical decision support. The interventions were implemented at the practice level with a waiver of individual informed consent. Clinicians received information on the study’s purpose and risks and consented to participate in the questionnaire linked to the online educational module. The pilot test of the clinical decision support nudges took place from 2/12/2019 to 5/31/2019. One clinic with 36 physicians received justification nudges only, one clinic with 23 physicians received the commitment nudges only, and one clinic with 9 physicians received both.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the variables collected from the overall validation population, the baseline measurements administered in the three pilot clinics before the pilot test, and final measurements in the three pilot clinics at the end of the pilot test.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the criteria for the seven high-risk polypharmacy measures we developed. In the overall validation population of 78,880 patients aged 65 years and older, the rates of these measures ranged from 0.04% for the chronic kidney disease glyburide/glimepiride interaction measure to 5.9% for the fall condition–drug interaction measure (indicating medication associated with falls was prescribed among individuals with prior fall or identified as at risk for fall [Table 3]). Of the 65 and older patient population, 7.9% took at least 5 different medications and had one or more of the high-risk criteria we examined. Among those prescribed five or more systemic medications, 11.4% had one or more high-risk criteria.

Table 3.

Frequencies of High-Risk Polypharmacy Among 78,880 Adults Aged 65 and Older in Primary Care Practices from a Large Health System during 1/1/2017 – 12/31/2018

| Measures | Denominator | Numerator | Rate among 55,107 patients prescribed ≥5 medications | Rate among all 78,880 ≥65 yo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any (1 or more) of the 7 measures | 55,107 | 6256 | 11.4% | 7.9% |

| CKD-glyburide/glimepiride interaction | 19,712 | 158 | 0.8% | 0.2% |

| CKD-NSAID interaction | 2321 | 72 | 3.1% | 0.1% |

| Fall condition–drug interaction | 15,118 | 4643 | 30.7% | 5.9% |

| Fall drug–drug interaction | 55,107 | 1494 | 2.7% | 1.9% |

| HF-non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker interaction | 4115 | 294 | 7.1% | 0.4% |

| HF-NSAID interaction | 5561 | 223 | 4.0% | 0.3% |

| HF-thiazolidinedione interaction | 5561 | 33 | 0.6% | 0.04% |

Characteristics of the pilot physicians, clinic volumes during the pilot, and the frequency of the nudges are provided in Table 4. During the pilot, physicians assigned to commitment nudges alone received mean (SD) 1.7 (0.4) nudges per week. Physicians in the justification nudges only group received 0.8 (0.5) nudges per week. Physicians assigned both received 1.9 (0.5) nudges per week (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of Pilot Physicians and Their Practices, Nudges Delivered, and Outcomes

| Participating pilot physicians | Commitment only N=23 |

Justification only N =36 |

Commitment and Justification N = 9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, N (%) | 14 (60.9) | 25 (69.4) | 6 (66.7) |

| Mean patient visits per week during pilot (SD) | 45.8 (3.8) | 19.4 (3.1) | 52.4 (5.9) |

| Patients seen by pilot physicians in the preceding year who met any (1 or more) of the 7 polypharmacy measures, n/N (%) | 776/7260 (10.7) | 965/6743 (14.3) | 216/2867 (7.5) |

| Average of Commitment nudges per physician per week (SD) | 1.7 (0.4) | N/A | 1.5 (0.5) |

| Average of Justification nudges per physician per week (SD) | N/A | 0.8 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.2) |

| Total nudges per physician per week (SD) | 1.7 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.5) |

| Nudges Delivered and outcomes | |||

| Nudges delivered during the pilot, N | 625 | 400 | 277 |

| Reminder requested, N (%) | 159 (25.4) | 0* | 77 (28) |

| Justification entered, N (%) | 0* | 172 (43.0) | 15 (5.4) |

| Patients with nudges, N | 581 | 288 | 207 |

| Patients with follow-up visit, N | 150 | 105 | 49 |

| Patients with fewer medications at end of pilot among patients with nudges and follow-up visit, n/N (%) | 53 / 150 (35) | 25 / 105 (24) | 21 / 49 (43) |

| Patients no longer meeting high-risk criteria at end of pilot among patients with nudges and follow-up visit, n/N (%) | 51 / 150 (34) | 17 / 105 (16) | 13 / 49 (27) |

| Patients no longer meeting high-risk criteria at end of pilot among all patients with nudges, n/N (%) | 199 / 581 (34.3) | 58 / 288 (20) | 65 / 207 (31) |

* Commitment nudges did not ask for justifications and justification nudges did not offer reminders

Physicians acknowledged 441 of 460 (95.9%) justification nudges, provided a text response for 187 (40.7%), and chose to share their justification with the patient for 135 (29.3%). They requested to be reminded to address in the future for 240/847 (28.3%) of the commitment nudges and indicated that they were reducing medication(s) now for 59/833 (7.1%).

During this short pilot, overall rates of the high-risk polypharmacy measures in the population decreased. Among patients whose physicians were exposed to one or more nudges and who had a visit following nudge exposure, 99 of 304 (32.6%) had a reduction in total medications prescribed, and 81 of 304 (26.6%) no longer met the criteria for high-risk polypharmacy that was previously identified.

Examples of the appearance of the justification and commitment nudges as well the patient message associated with the commitment nudge are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Examples of clinical decision support nudges shown to physicians. a Commitment Nudge b Justification Nudge

DISCUSSION

This work represents several new developments in the field of advancing medication safety for older adults.

First, we developed and validated seven eCQMs that indicate potentially inappropriate medication usage in older adults for use in electronic health records. Not all cases flagged by these measures represent inappropriate use and sometimes there are clinical tradeoffs involved when selecting pharmacotherapy. We agree with Steinman and Fick27 that the goal is not for scores on polypharmacy measures to reach 0; rather, we believe they are useful for identifying potentially risky prescribing practices and, at the patient level, serve as the starting point for review aimed at reducing risk through deprescribing when safer alternatives are available, or benefits that justify the increased risk are lacking.

Second, we applied these measures to a large ambulatory population in a regional health system and demonstrated that high-risk polypharmacy is common among patients aged 65 and older; 7.9% met one or more of the seven high-high risk criteria. Among those prescribed five or more medications, the prevalence was 11%. Fall condition–drug interaction was the most common quality indicator violated, appearing in 30% of those taking five or more medications and 6% of all patients over 65.

Third, we developed two behavioral science-informed EHR nudges to address high-risk polypharmacy. We then successfully deployed and pilot tested them. These interventions take advantage of behavioral and workflow analysis insights that we have not seen previously applied to improving medication prescribing. The commitment nudge acknowledges realities of refilling medications which may occur when clinicians have little time, may not be with the patient, and therefore may resist a recommendation to make a change at the time a refill is requested. The nudge takes advantage of the fact that the prescriber may be willing to agree to address this in the future, and may even discount the effort required to do so.28,29 People in general feel compelled to act consistently with their own prior commitments, particularly if those comments are made publicly to others. We hypothesize that this approach may lead to more effort towards reducing high-risk polypharmacy at future visits because providers are likely to honor their prior commitments, particularly if made with the patient’s knowledge.

The justification nudge aims to engender accountability by adding explicit documentation to the record about potentially inappropriate prescribing and by sharing this information with the patient directly. Our group applied a similar approach when a clinician was about to prescribe antibiotics for an acute respiratory tract infection for which antibiotics were likely not indicated.19,30–32 Here, we have applied that previously successful approach to high-risk polypharmacy.

LIMITATIONS

Several limitations should be noted. The data used to develop and test the eCQMs came from a single health system from one large metropolitan area. We do not know how generalizable the findings are to other settings. Second, we did not design measures to identify all potentially inappropriate medication uses from the evidence-based resources we evaluated. We restricted our focus to individuals prescribed five or more medications33 and who met additional risk criteria. Third, the pilot was performed among only 69 physicians over a short time. A longer and larger randomized trial is needed to test the effectiveness of these interventions on actual changes in prescribing behavior. Lastly, the measures did not include historical medications or medications prescribed outside this health system that were not reconciled; therefore, the number of patients with high-risk polypharmacy may have been underestimated.

CONCLUSIONS

We successfully developed electronic clinical quality measures of high-risk polypharmacy among older patients and implemented them in a commercial electronic health record. We used these criteria to deliver EHR-based decision support nudges informed by behavioral science research. This small-scale pilot demonstrates feasibility of this approach. We plan further testing in a multisite trial of greater duration.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 24 kb)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Ryan Chmiel and Darren Kaiser, Northwestern Memorial Healthcare, for their valuable contributions to the design and implementation of the clinical decision support used in this study.

FUNDING:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21AG057396. Dr. Linder’s contribution to this work was supported in part by grant P30AG059988 from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

DECLARATIONS

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Persell receives unrelated research support from Omron Healthcare Co, LTD., and has previously received unrelated research support from Pfizer, Inc. He is a consultant to the RAND Corporation. After the completion of the research presented in this paper, Dr. Friedberg became a paid employee of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Stephen D. Persell, Email: spersell@nm.org.

Tiffany Brown, Email: t-brown@northwestern.edu.

Jason N. Doctor, Email: jdoctor@usc.edu.

Craig R. Fox, Email: craig.fox@anderson.ucla.edu.

Noah J. Goldstein, Email: noah.goldstein@anderson.ucla.edu.

Steven M. Handler, Email: handler@pitt.edu.

Joseph T Hanlon, Email: jth14@pitt.edu.

Ji Young Lee, Email: jlee1@northwestern.edu.

Jeffrey A. Linder, Email: jlinder@northwestern.edu.

Daniella Meeker, Email: dmeeker@usc.edu.

Theresa A Rowe, Email: theresa.rowe@northwestern.edu.

Mark D. Sullivan, Email: sullimar@uw.edu.

Mark W. Friedberg, Email: mfriedberg1@partners.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Ruby CM, Weinberger M. Suboptimal prescribing in older inpatients and outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(2):200–209. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):57–65. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.827660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wastesson JW, Morin L, Tan ECK, Johnell K. An update on the clinical consequences of polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(12):1185–1196. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2018.1546841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW, Valim C, Mandl KD. Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting: an 11-year national analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(9):901–910. doi: 10.1002/pds.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Mahony D, O'Sullivan D, Byrne S, O'Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213–218. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J, O'Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person's Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46(2):72–83. doi: 10.5414/CPP46072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . National Action Plan for Adverse Drug Event Prevention. Washington, DC: Author; 2014. pp. 99–130. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rankin A, Cadogan CA, Patterson SM, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9(9):Cd008165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008165.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson T, Abuzahra ME, Keller S, et al. Impact of strategies to reduce polypharmacy on clinically relevant endpoints: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(2):532–548. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clyne B, Fitzgerald C, Quinlan A, et al. Interventions to Address Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(6):1210–1222. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yourman L, Concato J, Agostini JV. Use of computer decision support interventions to improve medication prescribing in older adults: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2008;6(2):119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tjia J, Velten SJ, Parsons C, Valluri S, Briesacher BA. Studies to reduce unnecessary medication use in frail older adults: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(5):285–307. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827–834. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper JA, Cadogan CA, Patterson SM, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy in older people: a Cochrane systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009235. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castelino RL, Bajorek BV, Chen TF. Targeting suboptimal prescribing in the elderly: a review of the impact of pharmacy services. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1096–1106. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clyne B, Bradley MC, Hughes C, Fahey T, Lapane KL. Electronic prescribing and other forms of technology to reduce inappropriate medication use and polypharmacy in older people: a review of current evidence. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):301–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New York: Penguin Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malhotra S, Cheriff AD, Gossey JT, Cole CL, Kaushal R, Ancker JS. Effects of an e-Prescribing interface redesign on rates of generic drug prescribing: exploiting default options. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(5):891–898. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiu AS, Jean RA, Hoag JR, Freedman-Weiss M, Healy JM, Pei KY. Association of Lowering Default Pill Counts in Electronic Medical Record Systems With Postoperative Opioid Prescribing. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(11):1012–1019. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–2246. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fick DM, Mion LC, Beers MH. J LW. Health outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(1):42–51. doi: 10.1002/nur.20232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stockl KM, Le L, Zhang S, Harada AS. Clinical and economic outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate prescribing in the elderly. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(1):e1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton H, Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, O'Mahony D. Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(11):1013–1019. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallagher PF, O'Connor MN, O'Mahony D. Prevention of potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial using STOPP/START criteria. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(6):845–854. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinman MA, Fick DM. Using Wisely: A Reminder on the Proper Use of the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria(R) J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):644–646. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loewenstein G, Prelec D. Anomalies in intertemporal choice: Evidence and an interpretation. Q J Econ. 1992;107(2):573–597. doi: 10.2307/2118482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers T, Bazerman MH. Future lock-in: Future implementation increases selection of ‘should’ choices. Organ Behav Human Decis Processes. 2008;106(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2007.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linder JA, Meeker D, Fox CR, et al. Effects of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing in Primary Care 12 Months After Stopping Interventions. JAMA. 2017;318(14):1391–1392. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Persell SD, Doctor JN, Friedberg MW, et al. Behavioral interventions to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing: a randomized pilot trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:373. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1715-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Persell SD, Friedberg MW, Meeker D, et al. Use of behavioral economics and social psychology to improve treatment of acute respiratory infections (BEARI): rationale and design of a cluster randomized controlled trial [1RC4AG039115-01]--study protocol and baseline practice and provider characteristics. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:290. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doan J, Zakrzewski-Jakubiak H, Roy J, Turgeon J, Tannenbaum C. Prevalence and risk of potential cytochrome P450-mediated drug-drug interactions in older hospitalized patients with polypharmacy. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(3):324–332. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hilmer SN, Tran K, Rubie P, et al. Gentamicin pharmacokinetics in old age and frailty. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71(2):224–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 24 kb)