Abstract

The gut microbiota and its metabolites have become a hotspot of recent research. Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) metabolized by the gut microbiota is closely related to many diseases such as cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, etc. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an important contributor to morbidity and mortality from non-communicable diseases. Recently, increasing focus has been put on the role of TMAO in the development and progress of chronic kidney disease. The level of TMAO in patients with chronic kidney disease is significantly increased, and a high level of TMAO deteriorates chronic kidney disease. This article describes the relationship between TMAO and chronic kidney disease and the research progress of drugs targeted TMAO, providing a reference for the development of anti-chronic kidney disease drugs targeted TMAO.

Keywords: trimethylamine N-oxide, chronic kidney disease, gut microbiota, targeted TMAO drugs, mechanism, treatment

1 Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) refers to abnormal kidney structure and function caused by various reasons such as diabetes, hypertension, and older age. A persistently reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 for more than 3 months) is the specific diagnostic criterion for CKD (National Kidney, 2002; Stevens and Levin, 2013). The global incidence of CKD in 2017 was 9.1%, and approximately 1.2 million people died of CKD. The prevalence of CKD is about 9.5%, and the death toll is about 176,000 in China in 2017 (Collaboration, 2020). It is estimated that CKD will become the fifth leading cause of early death by 2040 (Foreman et al., 2018). CKD is not only an important contributor to morbidity and mortality from non-communicable diseases, but also an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (Collaboration, 2020).

Early-stage CKD is asymptomatic and difficultly diagnosable. However, slowing early-stage CKD progression provides economic benefits (Trivedi et al., 2002) and prevents the development of End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) and cardiovascular complications (Group, 2013). The mechanisms of CKD have not been fully elucidated. Nephron loss, nephron hypertrophy, impaired glomerular filtration, and fibrosis are summarized as primary pathophysiological characteristics of CKD (Romagnani et al., 2017). The first-line drugs are inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), including angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), which have limited effectiveness and only delay CKD progression (Ruggenenti et al., 2012; Ruiz-Ortega et al., 2020). What’s more, Inhibitors of RAS must be used with caution in patients with advanced CKD (stages 4, 5), because they can lead to hyperkalemia, acute declines in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (Leon and Tangri, 2019). Therefore, developing novel medicines preventing CKD generation and progression and even achieving restoration of renal function in all patients with CKD are of paramount importance. Clarifying the mechanisms of CKD is an important step to find valuable targets for CKD treatment.

In addition, Common CKD biomarkers such as Cystatin C, creatinine, and Proteinuria have limitations, especially the low sensitivity of serum creatinine and eGFR in early-stage CKD and the limited application of uric acid under certain circumstances (Chonchol et al., 2007; Fassett et al., 2011). Progression of CKD is irreversible and there are no effective therapies for advanced CKD. The earlier the diagnosis, the greater the patients will benefit. Therefore, it is necessary to explore new biomarkers for early diagnosis and prediction of CKD.

TMAO can be detected in plasma, urine and feces, there are various methods to detect, such as LC-MS, and molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) based electrochemical sensor (Romano et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2015; Lakshmi et al., 2021; Rox et al., 2021). These methods were rapid, high-throughput and cost-effective for analysis TMAO, and preparation of samples was simple. LC-MS was a common method to detect TMAO which was easy to operate in clinical application.

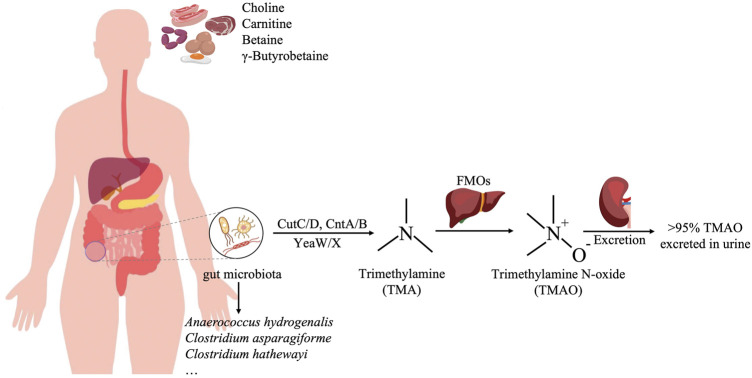

Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) is a metabolite of choline, L-carnitine, and betaine in the diet. Choline and L-carnitine that are not absorbed in the small intestine are metabolized by the gut flora into trimethylamine (TMA) in the colon and then oxidized to TMAO in the liver by Flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3) (Bennett et al., 2013). The gut microbiota produced TMA is various and abundant, such as Anaerococcus hydrogenalis, Clostridium asparagiforme, Clostridium hathewayi (Romano et al., 2015). The majority (greater than 95%) of trimethylamine N-oxide was excreted in urine, only 4% of the dose was excreted in the feces and <1% in the breath (Figure 1) (Al-Waiz et al., 1987). Studies have shown that TMAO is closely related to a variety of diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, and tumors. In recent years, the relationship between TMAO and CKD has been gradually recognized. TMAO level is related to the occurrence and prognosis of CKD, and it can serve as a potential risk factor for the development of CKD (Cho and Caudill, 2017). At present, the treatment of CKD mainly focuses on controlling its progression rate and related complications, and the treatment options are very limited. TMAO is expected to become a new target for CKD treatment and provide new options for CKD treatment (Tomlinson and Wheeler, 2017). This article reviews the relationship between TMAO and chronic kidney disease and the research progress of targeted TMAO drugs in order to provide a theoretical reference for the development of new anti-chronic kidney disease drugs.

FIGURE 1.

The production process of TMAO. Red meat, egg, and sausage are rich in choline and carnitine, which are metabolized by the gut flora, such as Anaerococcus hydrogenalis, Clostridium asparagiforme, and Clostridium hathewayi, into trimethylamine (TMA) in the colon, and then oxidized to TMAO in the liver by Flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3).

2 Trimethylamine N-oxide and chronic kidney disease

2.1 Trimethylamine N-oxide is a risk factor for chronic kidney disease

Risk factors for chronic kidney disease are various, including disease factors (Diabetes, hypertension, autoimmune diseases, systemic infections, urinary tract infections, acute kidney injury, etc.), Sociodemographic factors (age, gender, ethnicity, and family history of CKD, etc.), and lifestyle factor (smoking, heavy alcohol use, obesity, etc.) (Taal and Brenner, 2008; Drawz and Rahman, 2015). eGFR, an important indicator for kidney function, is used for diagnosis of CKD and assessment of progression of CKD. The common biomarkers of eGFR are Cystatin C and creatinine. (Fassett et al., 2011; Webster et al., 2017). These biomarkers’ measured concentrations are easily affected by factors other than eGFR. What’s more, Proteinuria, as a measure of kidney damage, is associated with the progression of CKD (Inker et al., 2014). An additional limitation of proteinuria is that it’s associated with rapid progression but that is not always present in CKD or may vary in different CKD stages (Group, 2013). Serum creatinine, eGFR, and proteinuria are insensitive and reliance on these may delay the early diagnosis and treatment (Fassett et al., 2011). Potential biomarkers have tried to overcome the limitations of current clinical biomarkers, such as biomarkers for the early stages of CKD and diagnosis of CKD in elderly individuals in whom the current clinical biomarkers have limited sensitivity and specificity (Canadas-Garre et al., 2019). The search for new relevant biomarkers to better stratify patients with CKD according to the risk of progression, morbidity, and mortality is underway.

Metabolomic studies in CKD found TMAO is a potential biomarker that may help identify CKD patients (Canadas-Garre et al., 2019). The TMAO level of CKD patients is higher than that of the control (Tang et al., 2015), and TMAO has a strong association with CKD in a validation study, 80% sensitivity with other six urinary metabolites including glutamate, guanidoacetate, and α-phenylacetylglutamine (all increased in CKD), 5-oxoproline, taurine, and citrate (all decreased in CKD) (Posada-Ayala et al., 2014). The levels of TMA and TMAO before hemodialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are also higher than those in the control (Bain et al., 2006). High circulating TMAO and baseline choline level have a strong correlation with the occurrence of CKD (Rhee et al., 2013). At the early stages of CKD, a high TMAO level in plasma indicates a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (Tang et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2017). In a cross-sectional study, Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and renal function were closely related with plasma TMAO levels and TMAO may serve as a diagnostic biomarker for HFpEF and renal function (Guo et al., 2020).

The impaired renal TMAO clearance may lead to elevated circulating TMAO concentration and reduced glomerular filtration rate, which could aggravate burden of kidney (Toyohara et al., 2010; Hai et al., 2015). In another study, there was a strong correlation between plasma TMAO levels and mGFR in CKD patients, that can be mainly related to a decrease in TMAO glomerular filtration (Pelletier et al., 2019). In animal models, it was found that increasing TMAO would aggravate renal fibrosis and renal dysfunction (Tang et al., 2015).

High TMAO concentration is associated with long-term mortality in patients with CKD and coronary atherosclerosis (Stubbs et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2022). Higher TMAO levels were associated with increased risk of all-cause death in CKD patients from mild to end-stage, which remained significance after controlling for glomerular filtration rates and other covariates, suggesting that TMAO can be an independent predictor for mortality in CKD patients (Missailidis et al., 2016). Similarly, circulating TMAO concentrations were shown to be the highest risk of cardiovascular events in patients with advanced CKD (Kim et al., 2016). Elevated TMAO concentration is associated with renal impairment and dysfunction, which predict poor long-term survival in CKD patients (Tang et al., 2015; Gruppen et al., 2017). However, Kaysen et al. (2015), didn’t find any significant association between serum TMAO concentrations and all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, or hospitalizations in 235 hemodialysis patients. There were studies that mainly researched 4-5 stage CKD, few about 1–3 stage CKD (Hu et al., 2022). The lack of early-stage CKD patients may limit the application of TMAO as a clinical biomarker of CKD. The level of TMAO in each stage of CKD patients was different (Hu et al., 2022). So the sensibility of TMAO in each CKD patients is unclear. TMAO stands out as a potential biomarker in CKD, which need to validate in the large-scale study and in different populations.

2.2 The mechanisms of trimethylamine N-oxide promoting the development of chronic kidney disease

Inflammation is an important mechanism for the TMAO-mediated occurrence and development of CKD. High concentration of TMAO leads to renal interstitial fibrosis and dysfunction by promoting renal oxidative stress and inflammation (Sun et al., 2017). Similarly, a high concentration of TMAO may reduce the production of NO by inducing vascular oxidative stress and inflammation, thereby triggering CKD complications, such as endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease (Li et al., 2018). TMAO activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to the release of IL-1β and IL-18, thereby accelerating kidney inflammation (Fang et al., 2021). Studies have found that TMAO promotes vascular calcification in rats with chronic kidney disease by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB signaling pathway. Antibiotic intervention reduces TMAO levels and reduces vascular calcification (Zhang et al., 2020). In addition, TMAO causes vascular inflammation and myocardial fibrosis to exacerbate cardiovascular disease by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome (Chen et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019a).

The mechanisms by which TMAO may enhance renal damage and aggravate nephropathy have not been well established. TMAO yet activates NF-κB signaling and then induce expression of inflammation gene (Seldin et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Besides, activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB signaling aggravate kidney disease (Vilaysane et al., 2010; Shahzad et al., 2015). In addition, long-term and excessive consumption of red meat (rich in carnitine and choline) can increase TMAO production and reduce renal excretion (Wang et al., 2019). This indicates that TMAO aggravates inflammation, but the related mechanisms of inducing kidney damage need to be thoroughly investigated. Therefore, it is important to investigate the mechanism of TMAO exacerbating kidney disease through activation of the inflammatory response, which can help TMAO become an effective target.

3 Potential treatments or drugs targeting trimethylamine N-oxide

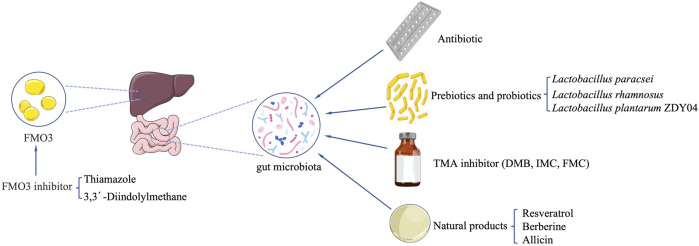

3.1 Regulation of gut microbiota

TMAO is related to the abundance of 13 genera of the gut microbiota, including Prevotella, Mitsuokella, Fusobacterium, Desulfovibrio, and bacteria belonging to Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae, as well as the Methane-producing bacteria Methanobrevibacter smithii (Fu et al., 2020), which could inspire the development of a drug that specifically targets these gut microbiotas. In other words, drugs that specifically target these gut microbes may have a better TMAO reduction effect. Studies on humans and animals have shown that several bacterial families are involved in the production of TMA-TMAO, such as Deferribacteraceae, Anaeroplasmataceae, Prevotellaceae (Koeth et al., 2013), and Enterobacteriaceae (Craciun and Balskus, 2012; Zhu et al., 2014). Thus, direct regulation of the gut microbiota can serve as one of the targets for regulating the production of TMAO.

3.1.1 Antibiotic

It is considered feasible to reduce TMAO levels by inhibiting the growth of the gut microbiota by using broad-spectrum antibiotics to achieve the purpose of treating chronic kidney disease. Now there is no effective evidence directly demonstrating the feasibility of the treatment, and several large randomized prospective human trials have shown no benefit of antibiotic treatment or prophylactic treatment for CVD. In patients with stable coronary artery disease, taking azithromycin every week for 1 year did not change the risk of cardiac events (Grayston et al., 2005). Long-term use of an antibiotic that is effective against Clostridium pneumonia has not been observed to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events (Cannon et al., 2005). The 3-month course of azithromycin did not significantly reduce the clinical sequelae of coronary heart disease in patients who are in a stable condition with previous myocardial infarction and with Chlamydia pneumonia infection (O’Connor et al., 2003).

Oral antibiotics can inhibit the increase of TMAO level after stimulation of the choline or carnitine diet, suggesting that intestinal bacteria are required for TMAO production (Wang et al., 2011; Koeth et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2013). Discontinuation of antibiotics for 1 month led to the increase of TMAO levels (Tang et al., 2013). This indicates that broad-spectrum antibiotics are not an ideal treatment, because they may have other undesired consequences, and long-term treatment may lead to the emergence of resistant bacteria (Velasquez et al., 2016). CKD patients are often accompanied by gut microbiota dysbiosis, and the use of antibiotics will aggravate the dysbiosis. Although it is unclear whether dysbiosis leads to the increase of TMAO production in CKD patients, it may lead to more serious consequences, such as impaired intestinal mucosal barrier, increased intestinal inflammation (Lange et al., 2016; Vaziri et al., 2016; Velasquez et al., 2016; Andersen et al., 2017). Therefore, antibiotics intervention may be not a desirable method. Targeted TMAO-producing gut microbiota, which undergoes non-lethal inhibition, may be a more reliable method.

3.1.2 Prebiotics and probiotics

Oral prebiotics or probiotics reduce the production of metabolites by changing the composition of the gut microbiota. Regulating the gut microbiota can alter their ability to produce TMA, which may be a reasonable intervention strategy for the prevention or treatment of TMAO-induced metabolic diseases (Kalagi et al., 2019).

Lactobacillus Plantarum ZDY04 can significantly reduce the content of TMAO in serum and TMA in the cecum by regulating the structure of gut microbiota community, and effectively inhibit the development of atherosclerosis in mice (Qiu et al., 2018). However, the research on the function of probiotics in the microbial-dependent production of TMA and TMAO is very limited (He and Chen, 2017). So far, there is no data on the potential effects of probiotics on the production of TMAO in humans (Koppe et al., 2015). After mice was administered with probiotic Lactobacillus paracsei, the production of TMA was reduced, but TMAO level remained unchanged; but after administered with Lactobacillus rhamnosus, the TMAO level was increased, and the TMA concentration in the liver of mice was unchanged (Martin et al., 2008). Treatment with multi-strain probiotic VSL#3 did not appear to reduce the elevated TMAO level in plasma caused by a high-fat diet (Boutagy et al., 2015). After supplementing CKD patients with probiotics (Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium longum) for 3 months, there was no change in TMAO level, but the betaine level in plasma was significantly increased (Borges et al., 2019). A randomized controlled trial study of probiotics in CKD patients found that probiotics were unable to reduce uremia toxins and inflammation markers (Table 1) (Borges et al., 2018). The efficacy of probiotics in CKD is uncertain, studies in its efficacy are urgently needed.

TABLE 1.

Probiotic/prebiotic that effect TMAO level.

| Probiotic/prebiotic | Result | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus paracsei | Decreased TMA and invariant TMAO | — | Martin et al. (2008) |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Increased TMAO and invariant TMA | — | Martin et al. (2008) |

| Multi-strain probiotic VSL#3 | Invariant TMAO in plasma | — | Boutagy et al. (2015) |

| Lactobacillus plantarum ZDY04 | Decreased TMAO in serum and TMA in the cecum | Lactobacillus plantarum ZDY04 regulate structure of the gut microbiota | Qiu et al. (2018) |

Coincidentally, the results of various trials in which probiotics were used to alter gut microbiota to improve uremia also show useless (Ranganathan et al., 2010; Miranda Alatriste et al., 2014; Natarajan et al., 2014). The low efficacy of the probiotics limits their clinical application. But Vaziri et al. (2016) proposed that it would be futile to try to restore the required microbiome by introducing beneficial microorganisms without simultaneously improving the biochemical environment of the intestine because the changed structure and function of the gut microbial community are caused by uremic-induced alterations of the intestinal biochemical/biophysical environment. Therefore, improving the gut microbiota environment while using probiotic intervention may enable better efficacy.

Furthermore, future researches need to focus on the interactions between probiotics and TMA production in the gut and activity of flavin monooxygenase (FMO) producing TMAO in the liver also need to be further explored (He and Chen, 2017). Therefore, it is also necessary to consider the impact of probiotic metabolism on the human body. We haven’t understood potential effect of probiotic metabolism in vivo.

3.2 Target trimethylamine N-oxide generation pathway

3.2.1 Trimethylamine inhibitor

There are four main enzymes involved in the production of TMA: choline-TMA lyase (CutC/D), carnitine monooxygenase (CntA/B), betaine reductase, and TMAO reductase (Barrett and Kwan, 1985; Craciun and Balskus, 2012). In addition, the CntA/B homologous enzyme YeaW/X can also transform betaine, γ-Butyrobetaine, L-carnitine and choline into TMA (Koeth et al., 2014; Iglesias-Carres et al., 2021).

Non-lethal targeting of microorganisms by selectively inhibiting pathways is beneficial to the host. TMA-production related enzymes such as CutC/D, CntA/B, and YeaW/X have become targets of current drug development (Rath et al., 2017). Studies with similar ideas have achieved good results. Structural analogs of choline, 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB), which non-lethally inhibits microbial CutC/D reduced TMAO level in mice fed with high choline or L-carnitine (Wang et al., 2015). This research team then modified DMB and found two choline analogs with better effects: iodomethylcholine (IMC) and fluoromethylcholine (FMC) (Roberts et al., 2018). Targetting TMA lyase of gut microbiota is a potential and effective way for the treatment of atherosclerotic heart disease, and inhibiting bacterial CutC is promising to be an effective strategy (Skye et al., 2018). In the isoproterenol-induced CKD mouse model, supplementation of IMC reduced the level of TMA and TMAO by selectively inhibiting the TMA lyase activity of the gut microbiota, consequently ameliorating tubulointerstitial fibrosis (TIF) induced by choline diet, and improving renal function damage. IMC prevents abnormal expression of multiple renal profibrotic genes and reverses multiple changes in gut microbiota composition associated with TMAO and renal function impairment (Gupta et al., 2020). Studies have also found that supplementing IMC can slow down the progression of chronic kidney disease (Zhang et al., 2021) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Target the gut microbiota that produces TMA or its TMA lyase.

| Selectively target | Result | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB) | Decreased TMAO | DMB non-lethally suppresses microbial CutC/D | Wang et al. (2015) |

| Iodomethylcholine (IMC) | Decreased TMA and TMAO | IMC and FMC selectively target inhibition of choline TMA lyase activity of the gut microbiota | Robert et al. (2018) |

| Fluoromethylcholine (FMC) | Gupta et al. (2020) | ||

| Iodomethylcholine (IMC) | Decreased TMAO level | IMC non-lethal inhibit choline TMA lyase activity | Zhang et al. (2021) |

3.2.2 Flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 inhibitor

There are many species of FMO3 substrate. Drugs such as Ranitidine, Benzydamine, Tamoxifen, Sulindac serve as substrates for FMOs (Lawton et al., 1990; Chung et al., 2000). Currently, few types of research reported FMO3 inhibitors, and FMO3 is not easily inhibited (Shimizu et al., 2015). Antisense oligonucleotide knockout FMO3 in mice reduced atherosclerosis, and downregulation of FMO3 not only reduced TMAO level but also regulated lipid metabolism and inflammation, thereby reducing atherosclerosis (Shih et al., 2015). Thiamazole is a classic substrate and competitive inhibitor of FMO3 with high affinity (Schweifer and Barlow, 1996). The 3,3′-Diindolylmethane from Cruciferous vegetables inhibited FMO3 activity and reduces the TMAO level (Chen et al., 2019). Clinical trials demonstrated that consuming indole reduces the relative ratio of TMAO to TMA by inhibiting FMO3 (Cashman et al., 1999), which binds to NADPH-specific residues similar to Thiamazole and competitively suppresses enzymatic activity (Steinke et al., 2020). Obviously, indole isn’t an ideal FMO inhibitor, because of its blood-brain barrier permeability and toxicity of indoxyl sulfate, a liver metabolite of indole (Chen et al., 2016a; Zajdel et al., 2016; Huc et al., 2018) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Compounds that inhibit FMO3 activity.

| FMO3 inhibitor | Results | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thiamazole | Decreased TMAO level, increased TMA level | Thiamazole is classic substrate and competitive inhibitor of FMO3 | Schweifer and Barlow (1996) |

| 3,3′-Diindolylmethane | Decreased TMAO level | 3,3′-Diindolylmethane inhibits FMO3 | Chen et al. (2019) |

| Cashman et al. (1999) | |||

| Consuming indole | Decreased the relative ratio of TMAO to TMA | Consuming indole competitively inhibits FMO3 | Steinke et al. (2020) |

However, regulation of TMAO concentrations by targeting FMO3 remains unfavorable, because the accumulation of TMA will exhibit “Fish Malodor Disorder”, therefore, appropriate targets that regulate TMAO levels need to be investigated (Dolphin et al., 1997; Zhang and Davies, 2016).

3.3 Potential drugs

3.3.1 Approved drugs

Ranitidine and Finasteride had potential effects of protecting cardiovascular system and kidneys by improving the composition of the gut microbiota, inhibiting the synthesis and metabolism of TMAO, delaying the deposition of lipids and endotoxins (Liu et al., 2020). Meldonium decreased the gut microbiota-dependent production of TMA/TMAO from L-carnitine in Wistar rats (Velasquez et al., 2016). Meldonium did not influence bacterial growth and bacterial uptake of L-carnitine, but TMA production by the bacteria K. pneumoniae was significantly decreased (Kuka et al., 2014). Vitamins B plus vitamin D lowered plasma fasting TMAO. The molecular mechanisms and health implications of these changes are currently unknown (Obeid et al., 2017). Aspirin reduced the level of TMAO by inhibiting the activity of microbial TMA lyase and reducing the atherogenic effects associated with a high-choline diet (SL, 2016), which highlighted the necessity of aspirin as a preventive treatment. In future clinical applications, “prevention before disease onset” enables the efficacy better (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Drugs that reduce TMAO level.

| Drugs | Results | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ranitidine | Decreased TMAO | Ranitidine and Finasteride inhibit the synthesis and metabolism of TMAO by improving composition of the gut microbiota | Liu et al. (2020) |

| Finasteride | |||

| Meldonium | Decreased the relative ratio of TMA to TMAO | Meldonium doesn’t influence bacterial growth and bacterial uptake of L-carnitine, but TMA production by the gut microbiota bacteria K. pneumoniae was significantly decreased | Kuka et al. (2014) |

| Velasquez et al. (2016) | |||

| Aspirin | Decreased TMAO | Aspirin inhibits the activity of microbial TMA lyase | SL, (2016) |

| Vitamins B vitamin D | Decreased TMAO in plasma | — | Obeid et al. (2017) |

3.3.2 Natural products

Resveratrol (RSV) attenuated TMAO-induced atherosclerosis (AS) by decreasing TMAO levels and increasing hepatic bile acid (BA) biosynthesis via remodeling the gut microbiota (Chen et al., 2016b). Berberine (BBR) attenuated TMA/TMAO production in the C57BL/6J and ApoE KO mice fed with choline-supplemented chow diet and mitigated atherosclerotic lesion areas in ApoE KO mice. BBR altered the gut microbiota composition, function, and cutC/cntA gene abundance. BBR was shown to inhibit choline-to-TMA conversion (Li et al., 2021). Gynostemma pentaphyllum (GP) elevated the level of phosphatidylcholine and decreased the level of TMAO (Wang et al., 2013). TMAO is closely related to phosphatidylcholine metabolism. The ability of GP to decrease TMAO levels suggests that GP has an inhibitory effect on the pathway of phosphatidylcholine to TMAO. Allicin reduced TMAO levels in mice fed with high choline. Allicin may be capable of protecting the host from producing TMAO when carnitine is consumed through its impact on the gut microbiota (Wu et al., 2015). Fructus Ligustri Lucidi (FLL) reduced FMO3 expression and TMAO level by regulating the gut microbiota in elderly mice (Li et al., 2019b). Consistent intake of Black Raspberry (BR) extract might alleviate hypercholesterolemia and hepatic inflammation induced by excessive choline with a high-fat diet via lowering the elevated level of TMA in cecal and TMAO in serum in rats, Polyphenols in BR extract reduced the level of TMA in the cecum by regulating the gut microbiota (Lim et al., 2020). Nobiletin significantly reduced TMAO-induced vascular inflammation via inhibition of the NF-κB/MAPK pathways. Nobiletin decreased TMAO-induced apoptosis of HUVEC cells and counteracted TMAO-induced HUVEC cell proliferation, which indicates that it has a potential ability to reduce TMAO levels (Yang et al., 2019). Black Beans (BB) lowers the abundance of hepatic FMO3, even with a high-fat diet protecting against the production of TMAO, which may be related to modification of the gut microbiota (Sanchez-Tapia et al., 2020) (Table 5; Figure 2).

TABLE 5.

Natural products that reduce TMAO level.

| Natural compounds | Results | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resveratrol (RSV) | Decreased TMAO and increased hepatic bile acid (BA) | RSV remodels the gut microbiota | Chen et al. (2016a) |

| Berberine (BBR) | Decreased the relative ratio of TMA to TMAO | BBR alteres the gut microbiota composition, microbiome functionality, and cutC/cntA gene abundance | Li et al. (2021) |

| Gynostemma pentaphyllum (GP) | Decreased TMAO and increased phosphatidylcholine | GP has an inhibitory effect on the pathway of phosphatidylcholine to TMAO | Wang et al. (2013) |

| Allicin | Decreased TMAO | Allicin altered the gut microbiota composition | Wu et al. (2015) |

| Fructus ligustri lucidi (FLL) | Decreased FMO3 expression and TMAO | FLL regulate the gut microbiota | Li et al. (2019a) |

| Black raspberry (BR) extract | Decreased TMA in cecal and TMAO in serum | Polyphenols in BR extract enable to reduce the level of TMA in the cecum by regulating the gut microbiota | Lim et al. (2020) |

| Nobiletin | Nobiletin reduced TMAO-induced vascular inflammation | Nobiletin inhibits of the NF-κB/MAPK pathways | Yang et al. (2019) |

| Black beans (BB) | Decreased FMO3 expression and TMAO | BB modificate the gut microbiota | Sanchez-Tapia et al. (2020) |

FIGURE 2.

Potential strategies to reduce TMAO formation in vivo.

Furthermore, the latest research reveals a new mechanism that a high-fat diet promotes the production of TMAO through the gut microbiota. Impaired bioenergetics of mitochondria in the colonic epithelium by high fat diet resulted in the increase of luminal bioavailability of oxygen and nitrate, thereby intensifying respiration-dependent choline catabolism of E. coli, which increased the level of circulating TMAO. The 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) treatment blunts the increase in circulating TMAO in mice on the choline-supplemented high-fat diet (Woongjae Yoo et al., 2021).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are first-line drugs for chronic kidney disease treatment (Excellence, 2021). Their main effect is to protect the kidney and slow the progression of kidney disease by lowering blood pressure and reducing urinary protein. However, ACEI and ARBs are not suitable for all CKD patients (Hricik et al., 1983; Textor et al., 1985; Holm et al., 1996). ACEI is contraindicated in CKD pregnant patients because it is related to neonatal anuria, pulmonary hypoplasia, and neonatal death (Hanssens et al., 1991; Hou, 1999). Therefore, TMAO-targeting drugs are expected to expand the application of patients with CKD, such as probiotics, food-borne natural compounds, etc., whose mild pharmacological effects may be suitable for the vast majority of patients with CKD. In addition, CKD is often associated with a variety of complications, such as mineral and bone disorders (MBD), and it is clinically recommended for regular vitamin D or vitamin D analogs and calcitriol treatment for MBD (Excellence, 2021; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes, 20112017). Vitamin D has previously been shown to lower TMAO levels (Obeid et al., 2017), it is worthy to investigate the role of Vitamin D in the treatment of CKD and its complications. In conclusion, drugs targeting TMAO are various which have a wide range of sources and great development potential. They are expected to be good complements and alternatives for CKD first-line drugs to overcome the limitations of this drugs, such as the limited applicable population, complicated medications for complications, etc.

4 Conclusion and future perspective

TMAO is closely related to chronic kidney disease. It is not only a risk factor for CKD but also a potential biomarker. This review summarizes the currently known drugs, natural compounds, probiotics, and prebiotics that can reduce the level of TMA and TMAO. Targeting the TMA-producing gut microbiota and TMAO-related enzymes are expected to be an important method to reduce TMAO level following the development of research on the gut microbiota and TMAO. It is unlikely that a single biomarker will satisfy the requirement of predicting CKD progression as it would be unlikely to reflect the complexities of the multiple pathophysiological processes involved in CKD progression. Therefore, TMAO may be used as a novel biomarker to assist other biomarkers to improve the accuracy of CKD detection.

Susceptibility to CKD has inter-individual differences (Webster et al., 2017), and difference in TMAO concentration among individuals is an important contributor, which may relate to individual differences in the composition of the microbiota. Genetic variation in the metabolism and disposition of TMAO modifies its concentration, which may be particularly consequential for CKD patients. Due to abnormal human TMA metabolism, the attention on FMO3 SNPs was spurred for many years. Until now more than 300 SNPs of the human FMO3 have been reported (D'Angelo et al., 2013). FMO3 allelic variants have a significant effect on TMAO production, which is closely related to trimethylaminuria (TMAU). The relationship between FMO3 allelic variants and CKD is unclear. FMO3 genotype at amino acid 158 was associated with higher plasma TMAO concentrations, and heterozygous CKD patients (E/K) and homozygous variant CKD patients (K/K) had a greater risk of mortality compared to homozygous CKD patients (E/E) (Robinson-Cohen et al., 2016). Studies had identified that organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2, SLC22A2) mediates TMAO uptake into renal proximal tubular cells and that multiple transporter of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family, including ABCG2 (BCRP) and ABCB1 (MDR1), are capable of TMAO efflux (Miyake et al., 2017; Teft et al., 2017). Therefore, gene polymorphisms of OCT2 and ABC in different populations may affect the excretion of TMAO, comprehensive genomic studies of transporters involved in TMAO excretion are required. Studies had found that gut microbiota abundance was significantly altered in CKD and ESRD patients, some of them are TMA producing bacteria, such as Firmicutes (Vaziri et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2017; Lun et al., 2019). To consider whether gut microbiota abundance can be used as a biomarker for patients with CKD. However, it is important to note that gut microbiota abundance may vary greatly at different stages of CKD disease, which requires that CKD patients at different stages are classified and studied in larger human cohorts.

In conclusion, there are many targets that regulate the production of TMAO. Nonlethal inhibition of the gut microbiota CutC/D, CntA/B et al. are of more clinical significance. Further research is needed to develop probiotics and probiotics to make them work in vivo. Researching approved drugs that can reduce TMAO levels with the help of the idea of “repurposing” would be able to save a lot of money for the early development of drugs. Natural compounds are abundant which require extensive screening and investigating the mechanisms. Besides, there are other methods to reduce the TMAO levels, such as taking advantage of the physical properties of the drug, AST-120 is a carbon preparation (Brand name: KREMEZIN), its efficient adsorption function can attenuate absorption of hazardous metabolites in vivo. The use of AST-120 in animals and patients with chronic kidney disease can reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, and slow down the progression of kidney disease (Shibahara and Shibahara, 2010; Nakamura et al., 2011; Bolati et al., 2012; Ito et al., 2013). There are also other potential inhibitors, It was reported that many choline-utilizing gut microorganisms can hydrolyze phosphatidylcholine (PC) using a phospholipase D (PLD) enzyme and further convert the released choline to TMA (Chittim et al., 2019), Thus searching for inhibitors that target PLD without affecting host enzymes may reduce PC hydrolyze, then reducing TMAO production.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft. CL: Revising. ZX: Writing—review and editing. FQ: Revising. ZB: Revising. LC: Revising. RT: Writing—review and editing. OD: Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by Hunan Provincial Natural Science Fund (S2022JJKYLH0094); Hunan Key Laboratory for Bioanalysis of Complex Matrix Samples (grant number2017TP1037); Key R&D Programs of Hunan Province (grant number 2019SK2241); International Scientific and Technological Innovation Cooperation Base for Bioanalysis of ComplexMatrix Samples in Hunan Province (grant number2019CB1014); Hunan Science and technology innovation plan project (grant number 2018SK52008).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Al-Waiz M., Mitchell S. C., Idle J. R., Smith R. L. (1987). The metabolism of 14C-labelled trimethylamine and its N-oxide in man. Xenobiotica. 17 (5), 551–558. 10.3109/00498258709043962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen K., Kesper M. S., Marschner J. A., Konrad L., Ryu M., Kumar Vr S., et al. (2017). Intestinal dysbiosis, barrier dysfunction, and bacterial translocation account for CKD-related systemic inflammation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28 (1), 76–83. 10.1681/ASN.2015111285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain M. A., Faull R., Fornasini G., Milne R. W., Evans A. M. (2006). Accumulation of trimethylamine and trimethylamine-N-oxide in end-stage renal disease patients undergoing haemodialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 21 (5), 1300–1304. 10.1093/ndt/gfk056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett E. L., Kwan H. S. (1985). Bacterial reduction of trimethylamine oxide. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 39, 131–149. 10.1146/annurev.mi.39.100185.001023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B. J., de Aguiar Vallim T. Q., Wang Z., Shih D. M., Meng Y., Gregory J., et al. (2013). Trimethylamine-N-oxide, a metabolite associated with atherosclerosis, exhibits complex genetic and dietary regulation. Cell. Metab. 17 (1), 49–60. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolati D., Shimizu H., Niwa T. (2012). AST-120 ameliorates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and interstitial fibrosis in the kidneys of chronic kidney disease rats. J. Ren. Nutr. 22 (1), 176–180. 10.1053/j.jrn.2011.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges N. A., Carmo F. L., Stockler-Pinto M. B., de Brito J. S., Dolenga C. J., Ferreira D. C., et al. (2018). Probiotic supplementation in chronic kidney disease: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Ren. Nutr. 28 (1), 28–36. 10.1053/j.jrn.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges N. A., Stenvinkel P., Bergman P., Qureshi A. R., Lindholm B., Moraes C., et al. (2019). Effects of probiotic supplementation on trimethylamine-N-oxide plasma levels in hemodialysis patients: A pilot study. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 11 (2), 648–654. 10.1007/s12602-018-9411-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutagy N. E., Neilson A. P., Osterberg K. L., Smithson A. T., Englund T. R., Davy B. M., et al. (2015). Probiotic supplementation and trimethylamine-N-oxide production following a high-fat diet. Obes. (Silver Spring) 23 (12), 2357–2363. 10.1002/oby.21212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadas-Garre M., Anderson K., McGoldrick J., Maxwell A. P., McKnight A. J. (2019). Proteomic and metabolomic approaches in the search for biomarkers in chronic kidney disease. J. Proteomics 193, 93–122. 10.1016/j.jprot.2018.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon C. P., Braunwald E., McCabe C. H., Grayston J. T., Muhlestein B., Giugliano R. P., et al. (2005). Antibiotic treatment of Chlamydia pneumoniae after acute coronary syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 352 (16), 1646–1654. 10.1056/NEJMoa043528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman J. R., Xiong Y., Lin J., VerHagen H., van Poppel G., van Bladeren P. J., et al. (1999). In vitro and in vivo inhibition of human flavin-containing monooxygenase form 3 (FMO3) in the presence of dietary indoles. Biochem. Pharmacol. 58 (6), 1047–1055. 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00166-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Tao L. X., Xiao W., Ji S. S., Wang J. R., Li X. W., et al. (2016). Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel chiral oxazino-indoles as potential and selective neuroprotective agents against Aβ25-35-induced neuronal damage.. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 26 (15), 3765–3769. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.05.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. L., Yi L., Zhang Y., Zhou X., Ran L., Yang J., et al. (2016). Resveratrol attenuates trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)-Induced atherosclerosis by regulating TMAO synthesis and bile acid metabolism via remodeling of the gut microbiota. mBio 7 (2), e02210–15. 10.1128/mBio.02210-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. L., Zhu X. H., Ran L., Lang H. D., Yi L., Mi M. T. (2017). Trimethylamine-N-Oxide induces vascular inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through the SIRT3-SOD2-mtROS signaling pathway. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6 (9), e006347. 10.1161/JAHA.117.006347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Henderson A., Petriello M. C., Romano K. A., Gearing M., Miao J., et al. (2019). Trimethylamine N-oxide binds and activates PERK to promote metabolic dysfunction. Cell. Metab. 30 (6), 1141–1151. 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittim C. L., Martinez Del Campo A., Balskus E. P. (2019). Gut bacterial phospholipase Ds support disease-associated metabolism by generating choline. Nat. Microbiol. 4 (1), 155–163. 10.1038/s41564-018-0294-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho C. E., Caudill M. A. (2017). Trimethylamine-N-Oxide: Friend, foe, or simply caught in the cross-fire? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 28 (2), 121–130. 10.1016/j.tem.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chonchol M., Shlipak M. G., Katz R., Sarnak M. J., Newman A. B., Siscovick D. S., et al. (2007). Relationship of uric acid with progression of kidney disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 50 (2), 239–247. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung W. G., Park C. S., Roh H. K., Lee W. K., Cha Y. N. (2000). Oxidation of ranitidine by isozymes of flavin-containing monooxygenase and cytochrome P450. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 84 (2), 213–220. 10.1254/jjp.84.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaboration G. B. D. C. K. D. (2020). Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 395 (10225), 709–733. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciun S., Balskus E. P. (2012). Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109 (52), 21307–21312. 10.1073/pnas.1215689109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo R., Esposito T., Calabro M., Rinaldi C., Robledo R., Varriale B., et al. (2013). FMO3 allelic variants in Sicilian and Sardinian populations: Trimethylaminuria and absence of fish-like body odor. Gene 515 (2), 410–415. 10.1016/j.gene.2012.12.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin C. T., Riley J. H., Smith R. L., Shephard E. A., Phillips I. R. (1997). Structural organization of the human flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 gene (FMO3), the favored candidate for fish-odor syndrome, determined directly from genomic DNA. Genomics 46 (2), 260–267. 10.1006/geno.1997.5031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drawz P., Rahman M. (2015). Chronic kidney disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 162 (11), ITC1–16. 10.7326/AITC201506020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excellence N. i. f. H. a. C. (2021). Chronic kidney disease: Assessment and management[ng203]. London: NICE. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Q., Zheng B., Liu N., Liu J., Liu W., Huang X., et al. (2021). Trimethylamine N-oxide exacerbates renal inflammation and fibrosis in rats with diabetic kidney disease. Front. Physiol. 12, 682482. 10.3389/fphys.2021.682482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassett R. G., Venuthurupalli S. K., Gobe G. C., Coombes J. S., Cooper M. A., Hoy W. E. (2011). Biomarkers in chronic kidney disease: A review. Kidney Int. 80 (8), 806–821. 10.1038/ki.2011.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman K. J., Marquez N., Dolgert A., Fukutaki K., Fullman N., McGaughey M., et al. (2018). Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: Reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 392 (10159), 2052–2090. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31694-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu B. C., Hullar M. A. J., Randolph T. W., Franke A. A., Monroe K. R., Cheng I., et al. (2020). Associations of plasma trimethylamine N-oxide, choline, carnitine, and betaine with inflammatory and cardiometabolic risk biomarkers and the fecal microbiome in the Multiethnic Cohort Adiposity Phenotype Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 111 (6), 1226–1234. 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayston J. T., Kronmal R. A., Jackson L. A., Parisi A. F., Muhlestein J. B., Cohen J. D., et al. (2005). Azithromycin for the secondary prevention of coronary events. N. Engl. J. Med. 352 (16), 1637–1645. 10.1056/NEJMoa043526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group K. D. I. G. O. K. C. W. (2013). KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. (3), 1–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruppen E. G., Garcia E., Connelly M. A., Jeyarajah E. J., Otvos J. D., Bakker S. J. L., et al. (2017). TMAO is associated with mortality: Impact of modestly impaired renal function. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 13781. 10.1038/s41598-017-13739-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F., Qiu X., Tan Z., Li Z., Ouyang D. (2020). Plasma trimethylamine n-oxide is associated with renal function in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 20 (1), 394. 10.1186/s12872-020-01669-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N., Buffa J. A., Roberts A. B., Sangwan N., Skye S. M., Li L., et al. (2020). Targeted inhibition of gut microbial trimethylamine N-oxide production reduces renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis and functional impairment in a murine model of chronic kidney disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 40 (5), 1239–1255. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai X., Landeras V., Dobre M. A., DeOreo P., Meyer T. W., Hostetter T. H. (2015). Mechanism of prominent trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) accumulation in hemodialysis patients. PLoS One 10 (12), e0143731. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssens M., Keirse M. J., VankelecomF., Van Assche F. A. (1991). Fetal and neonatal effects of treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 78 (1), 128–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Chen Z. Y. (2017). What are missing parts in the research story of trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)? J. Agric. Food Chem. 65 (26), 5227–5228. 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm E. A., Randlov A., Strandgaard S. (1996). Brief report: Acute renal failure after losartan treatment in a patient with bilateral renal artery stenosis. Blood Press. 5 (6), 360–362. 10.3109/08037059609078075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S. (1999). Pregnancy in chronic renal insufficiency and end-stage renal disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 33 (2), 235–252. 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70296-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hricik D. E., Browning P. J., Kopelman R., Goorno W. E., Madias N. E., Dzau V. J. (1983). Captopril-induced functional renal insufficiency in patients with bilateral renal-artery stenoses or renal-artery stenosis in a solitary kidney. N. Engl. J. Med. 308 (7), 373–376. 10.1056/NEJM198302173080706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D. Y., Wu M. Y., Chen G. Q., Deng B. Q., Yu H. B., Huang J., et al. (2022). Metabolomics analysis of human plasma reveals decreased production of trimethylamine N-oxide retards the progression of chronic kidney disease. Br. J. Pharmacol.. 10.1111/bph.15856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huc T., Nowinski A., Drapala A., Konopelski P., Ufnal M. (2018). Indole and indoxyl sulfate, gut bacteria metabolites of tryptophan, change arterial blood pressure via peripheral and central mechanisms in rats. Pharmacol. Res. 130, 172–179. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Carres L., Hughes M. D., Steele C. N., Ponder M. A., Davy K. P., Neilson A. P. (2021). Use of dietary phytochemicals for inhibition of trimethylamine N-oxide formation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 91, 108600. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2021.108600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inker L. A., Levey A. S., Pandya K., Stoycheff N., Okparavero A., Greene T., et al. (2014). Early change in proteinuria as a surrogate end point for kidney disease progression: An individual patient meta-analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 64 (1), 74–85. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S., Higuchi Y., Yagi Y., Nishijima F., Yamato H., Ishii H., et al. (2013). Reduction of indoxyl sulfate by AST-120 attenuates monocyte inflammation related to chronic kidney disease. J. Leukoc. Biol. 93 (6), 837–845. 10.1189/jlb.0112023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalagi N. A., Abbott K. A., Alburikan K. A., Alkofide H. A., Stojanovski E., Garg M. L. (2019). Modulation of circulating trimethylamine N-oxide concentrations by dietary supplements and pharmacological agents: A systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 10 (5), 876–887. 10.1093/advances/nmz012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen G. A., Johansen K. L., Chertow G. M., Dalrymple L. S., Kornak J., Grimes B., et al. (2015). Associations of trimethylamine N-oxide with nutritional and inflammatory biomarkers and cardiovascular outcomes in patients new to dialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 25 (4), 351–356. 10.1053/j.jrn.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes C. K. D. M. B. D. U. W. G. (20112017). KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int. Suppl. 7 (1), 1–59. 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R. B., Morse B. L., Djurdjev O., Tang M., Muirhead N., Barrett B., et al. (2016). Advanced chronic kidney disease populations have elevated trimethylamine N-oxide levels associated with increased cardiovascular events. Kidney Int. 89 (5), 1144–1152. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeth R. A., Levison B. S., Culley M. K., Buffa J. A., Wang Z., Gregory J. C., et al. (2014). γ-Butyrobetaine is a proatherogenic intermediate in gut microbial metabolism of L-carnitine to TMAO.. Cell. Metab. 20 (5), 799–812. 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeth R. A., Wang Z., Levison B. S., Buffa J. A., Org E., Sheehy B. T., et al. (2013). Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 19 (5), 576–585. 10.1038/nm.3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppe L., Mafra D., Fouque D. (2015). Probiotics and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 88 (5), 958–966. 10.1038/ki.2015.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuka J., Liepinsh E., Makrecka-Kuka M., Liepins J., Cirule H., Gustina D., et al. (2014). Suppression of intestinal microbiota-dependent production of pro-atherogenic trimethylamine N-oxide by shifting L-carnitine microbial degradation. Life Sci. 117 (2), 84–92. 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi G., Yadav A. K., Mehlawat N., Jalandra R., Solanki P. R., Kumar A. (2021). Gut microbiota derived trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) detection through molecularly imprinted polymer based sensor. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1338. 10.1038/s41598-020-80122-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange K., Buerger M., Stallmach A., Bruns T. (2016). Effects of antibiotics on gut microbiota. Dig. Dis. 34 (3), 260–268. 10.1159/000443360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M. P., GasseR R., Tynes R. E., Hodgson E., Philpot R. M. (1990). The flavin-containing monooxygenase enzymes expressed in rabbit liver and lung are products of related but distinctly different genes. J. Biol. Chem. 265 (10), 5855–5861. 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)39441-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon S. J., Tangri N. (2019). The use of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in patients with chronic kidney disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 35 (9), 1220–1227. 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Chen B., Zhu R., Li R., Tian Y., Liu C., et al. (2019). Fructus Ligustri Lucidi preserves bone quality through the regulation of gut microbiota diversity, oxidative stress, TMAO and Sirt6 levels in aging mice. Aging (Albany NY) 11 (21), 9348–9368. 10.18632/aging.102376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Gua C., Wu B., Chen Y. (2018). Increased circulating trimethylamine N-oxide contributes to endothelial dysfunction in a rat model of chronic kidney disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 495 (2), 2071–2077. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.12.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Geng J., Zhao J., Ni Q., Zhao C., Zheng Y., et al. (2019). Trimethylamine N-oxide exacerbates cardiac fibrosis via activating the NLRP3 inflammasome. Front. Physiol. 10, 866. 10.3389/fphys.2019.00866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Su C., Jiang Z., Yang Y., Zhang Y., Yang M., et al. (2021). Berberine attenuates choline-induced atherosclerosis by inhibiting trimethylamine and trimethylamine-N-oxide production via manipulating the gut microbiome. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 7 (1), 36. 10.1038/s41522-021-00205-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim T., Ryu J., Lee K., Park S. Y., Hwang K. T. (2020). Protective effects of Black Raspberry (rubus occidentalis) extract against hypercholesterolemia and hepatic inflammation in rats fed high-fat and high-choline diets. Nutrients 12 (8), E2448. 10.3390/nu12082448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Lai L., Lin J., Zheng J., Nie X., Zhu X., et al. (2020). Ranitidine and finasteride inhibit the synthesis and release of trimethylamine N-oxide and mitigates its cardiovascular and renal damage through modulating gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16 (5), 790–802. 10.7150/ijbs.40934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lun H., Yang W., Zhao S., Jiang M., Xu M., Liu F., et al. (2019). Altered gut microbiota and microbial biomarkers associated with chronic kidney disease. Microbiologyopen 8 (4), e00678. 10.1002/mbo3.678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F. P., Wang Y., Sprenger N., Yap I. K. S., Lundstedt T., Lek P., et al. (2008). Probiotic modulation of symbiotic gut microbial-host metabolic interactions in a humanized microbiome mouse model. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4, 157. 10.1038/msb4100190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda Alatriste P. V., Urbina Arronte R., Gomez Espinosa C. O., Espinosa Cuevas M. d. l. A. (2014). Effect of probiotics on human blood urea levels in patients with chronic renal failure. Nutr. Hosp. 29 (3), 582–590. 10.3305/nh.2014.29.3.7179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missailidis C., Hallqvist J., Qureshi A. R., Barany P., Heimburger O., Lindholm B., et al. (2016). Serum trimethylamine-N-oxide is strongly related to renal function and predicts outcome in chronic kidney disease. PLoS One 11 (1), e0141738. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake T., Mizuno T., Mochizuki T., Kimura M., Matsuki S., Irie S., et al. (2017). Involvement of organic cation transporters in the kinetics of trimethylamine N-oxide. J. Pharm. Sci. 106 (9), 2542–2550. 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.04.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T., Sato E., Fujiwara N., Kawagoe Y., Suzuki T., Ueda Y., et al. (2011). Oral adsorbent AST-120 ameliorates tubular injury in chronic renal failure patients by reducing proteinuria and oxidative stress generation. Metabolism. 60 (2), 260–264. 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan R., Pechenyak B., Vyas U., Ranganathan P., Weinberg A., Liang P., et al. (2014). Randomized controlled trial of strain-specific probiotic formulation (Renadyl) in dialysis patients. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 568571. 10.1155/2014/568571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Kidney F. (2002). K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 39 (2 Suppl. 1), S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor C. M., Dunne M. W., Pfeffer M. A., Muhlestein J. B., Yao L., Gupta S., et al. (2003). Azithromycin for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease events: The WIZARD study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290 (11), 1459–1466. 10.1001/jama.290.11.1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeid R., Awwad H. M., Kirsch S. H., Waldura C., Herrmann W., Graeber S., et al. (2017). Plasma trimethylamine-N-oxide following supplementation with vitamin D or D plus B vitamins. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 61 (2), 1600358. 10.1002/mnfr.201600358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier C. C., Croyal M., Ene L., Aguesse A., Billon-Crossouard S., Krempf M., et al. (2019). Elevation of trimethylamine-N-oxide in chronic kidney disease: Contribution of decreased glomerular filtration rate. Toxins (Basel) 11 (11), E635. 10.3390/toxins11110635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada-Ayala M., Zubiri I., Martin-Lorenzo M., Sanz-Maroto A., Molero D., Gonzalez-Calero L., et al. (2014). Identification of a urine metabolomic signature in patients with advanced-stage chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 85 (1), 103–111. 10.1038/ki.2013.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L., Tao X., Xiong H., Yu J., Wei H. (2018). Lactobacillus plantarum ZDY04 exhibits a strain-specific property of lowering TMAO via the modulation of gut microbiota in mice. Food Funct. 9 (8), 4299–4309. 10.1039/c8fo00349a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan N., Ranganathan P., Friedman E. A., Joseph A., Delano B., Goldfarb D. S., et al. (2010). Pilot study of probiotic dietary supplementation for promoting healthy kidney function in patients with chronic kidney disease. Adv. Ther. 27 (9), 634–647. 10.1007/s12325-010-0059-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath S., Heidrich B., Pieper D. H., Vital M. (2017). Uncovering the trimethylamine-producing bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Microbiome 5 (1), 54. 10.1186/s40168-017-0271-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee E. P., Clish C. B., Ghorbani A., Larson M. G., Elmariah S., McCabe E., et al. (2013). A combined epidemiologic and metabolomic approach improves CKD prediction. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24 (8), 1330–1338. 10.1681/ASN.2012101006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A. B., Gu X., Buffa J. A., Hurd A. G., Wang Z., Zhu W., et al. (2018). Development of a gut microbe-targeted nonlethal therapeutic to inhibit thrombosis potential. Nat. Med. 24 (9), 1407–1417. 10.1038/s41591-018-0128-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Cohen C., Newitt R., Shen D. D., Rettie A. E., Kestenbaum B. R., Himmelfarb J., et al. (2016). Association of FMO3 variants and trimethylamine N-oxide concentration, disease progression, and mortality in CKD patients. PLoS One 11 (8), e0161074. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romagnani P., Remuzzi G., Glassock R., Levin A., Jager K. J., Tonelli M., et al. (2017). Chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 3, 17088. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano K. A., Vivas E. I., Amador-Noguez D., Rey F. E. (2015). Intestinal microbiota composition modulates choline bioavailability from diet and accumulation of the proatherogenic metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. mBio 6 (2), e02481. 10.1128/mBio.02481-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rox K., Rath S., Pieper D. H., Vital M., Bronstrup M. (2021). A simplified LC-MS/MS method for the quantification of the cardiovascular disease biomarker trimethylamine-N-oxide and its precursors. J. Pharm. Anal. 11 (4), 523–528. 10.1016/j.jpha.2021.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggenenti P., Cravedi P., Remuzzi G. (2012). Mechanisms and treatment of CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23 (12), 1917–1928. 10.1681/ASN.2012040390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ortega M., Rayego-Mateos S., Lamas S., Ortiz A., Rodrigues-Diez R. R. (2020). Targeting the progression of chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16 (5), 269–288. 10.1038/s41581-019-0248-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Tapia M., Hernandez-Velazquez I., Pichardo-Ontiveros E., Granados-Portillo O., Galvez A., Tovar A. R., et al. (2020). Reply: "Comment on "consumption of cooked Black beans stimulates a cluster of some clostridia class bacteria decreasing inflammatory response and improving insulin sensitivity.".. Nutrients 12 (4), E2093. 10.3390/nu12072093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweifer N., Barlow D. P. (1996). The Lx1 gene maps to mouse chromosome 17 and codes for a protein that is homologous to glucose and polyspecific transmembrane transporters. Mamm. Genome 7 (10), 735–740. 10.1007/s003359900223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seldin M. M., Meng Y., Qi H., Zhu W., Wang Z., Hazen S. L., et al. (2016). Trimethylamine N-oxide promotes vascular inflammation through signaling of mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κb.. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5 (2), e002767. 10.1161/JAHA.115.002767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad K., Bock F., Dong W., Wang H., Kopf S., Kohli S., et al. (2015). Nlrp3-inflammasome activation in non-myeloid-derived cells aggravates diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 87 (1), 74–84. 10.1038/ki.2014.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibahara H., Shibahara N. (2010). Cardiorenal protective effect of the oral uremic toxin absorbent AST-120 in chronic heart disease patients with moderate CKD. J. Nephrol. 23 (5), 535–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih D. M., Wang Z., Lee R., Meng Y., Che N., Charugundla S., et al. (2015). Flavin containing monooxygenase 3 exerts broad effects on glucose and lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis. J. Lipid Res. 56 (1), 22–37. 10.1194/jlr.M051680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M., Shiraishi A., Sato A., Nagashima S., Yamazaki H. (2015). Potential for drug interactions mediated by polymorphic flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 in human livers. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 30 (1), 70–74. 10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skye S. M., Zhu W., Romano K. A., Guo C. J., Wang Z., Jia X., et al. (2018). Microbial transplantation with human gut commensals containing CutC is sufficient to transmit enhanced platelet reactivity and thrombosis potential. Circ. Res. 123 (10), 1164–1176. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sl H. (2016). Treating and preventing disease with TMA and TMAO lowering agents. US: Cleveland Clinic Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Steinke I., Ghanei N., Govindarajulu M., Yoo S., Zhong J., Amin R. H. (2020). Drug discovery and development of novel therapeutics for inhibiting TMAO in models of atherosclerosis and diabetes. Front. Physiol. 11, 567899. 10.3389/fphys.2020.567899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens P. E., Levin A. (2013). Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: Synopsis of the kidney disease: Improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline.. Ann. Intern. Med. 158 (11), 825–830. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J. R., House J. A., Ocque A. J., Zhang S., Johnson C., Kimber C., et al. (2016). Serum trimethylamine-N-oxide is elevated in CKD and correlates with coronary atherosclerosis burden. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27 (1), 305–313. 10.1681/ASN.2014111063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G., Yin Z., Liu N., Bian X., Yu R., Su X., et al. (2017). Gut microbial metabolite TMAO contributes to renal dysfunction in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 493 (2), 964–970. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taal M. W., Brenner B. M. (2008). Renal risk scores: Progress and prospects. Kidney Int. 73 (11), 1216–1219. 10.1038/ki.2008.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. H., Wang Z., Kennedy D. J., Wu Y., Buffa J. A., Agatisa-Boyle B., et al. (2015). Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ. Res. 116 (3), 448–455. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. H., Wang Z., Levison B. S., Koeth R. A., Britt E. B., Fu X., et al. (2013). Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 (17), 1575–1584. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teft W. A., Morse B. L., Leake B. F., Wilson A., Mansell S. E., Hegele R. A., et al. (2017). Identification and characterization of trimethylamine-N-oxide uptake and efflux transporters. Mol. Pharm. 14 (1), 310–318. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Textor S. C., Novick A. C., Tarazi R. C., Klimas V., Vidt D. G., PohlM. (1985). Critical perfusion pressure for renal function in patients with bilateral atherosclerotic renal vascular disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 102 (3), 308–314. 10.7326/0003-4819-102-3-308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson J. A. P., Wheeler D. C. (2017). The role of trimethylamine N-oxide as a mediator of cardiovascular complications in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 92 (4), 809–815. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.03.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyohara T., Akiyama Y., Suzuki T., Takeuchi Y., Mishima E., Tanemoto M., et al. (2010). Metabolomic profiling of uremic solutes in CKD patients. Hypertens. Res. 33 (9), 944–952. 10.1038/hr.2010.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi H. S., Pang M. M. H., Campbell A., Saab P. (2002). Slowing the progression of chronic renal failure: Economic benefits and patients' perspectives. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 39 (4), 721–729. 10.1053/ajkd.2002.31990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri N. D., Wong J., Pahl M., Piceno Y. M., Yuan J., DeSantis T. Z., et al. (2013). Chronic kidney disease alters intestinal microbial flora. Kidney Int. 83 (2), 308–315. 10.1038/ki.2012.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri N. D., Zhao Y. Y., Pahl M. V. (2016). Altered intestinal microbial flora and impaired epithelial barrier structure and function in CKD: The nature, mechanisms, consequences and potential treatment. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 31 (5), 737–746. 10.1093/ndt/gfv095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez M. T., Ramezani A., Manal A., Raj D. S. (2016). Trimethylamine N-oxide: The good, the bad and the unknown. Toxins (Basel) 8 (11), E326. 10.3390/toxins8110326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilaysane A., Chun J., Seamone M. E., Wang W., Chin R., Hirota S., et al. (2010). The NLRP3 inflammasome promotes renal inflammation and contributes to CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21 (10), 1732–1744. 10.1681/ASN.2010020143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Wang F., Wang Y., Ma X., Zhao M., Zhao C. (2013). Metabonomics study of the therapeutic mechanism of Gynostemma pentaphyllum and atorvastatin for hyperlipidemia in rats. PLoS One 8 (11), e78731. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Bergeron N., Levison B. S., Li X. S., Chiu S., Jia X., et al. (2019). Impact of chronic dietary red meat, white meat, or non-meat protein on trimethylamine N-oxide metabolism and renal excretion in healthy men and women. Eur. Heart J. 40 (7), 583–594. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Klipfell E., Bennett B. J., Koeth R., Levison B. S., Dugar B., et al. (2011). Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 472 (7341), 57–63. 10.1038/nature09922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Roberts A. B., Buffa J. A., Levison B. S., Zhu W., Org E., et al. (2015). Non-lethal inhibition of gut microbial trimethylamine production for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell. 163 (7), 1585–1595. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster A. C., Nagler E. V., Morton R. L., Masson P. (2017). Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 389 (10075), 1238–1252. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32064-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W. K., Ho C-T., Kuo C-H., Wu M-S., Sheen L-Y., Sheen L. Y. (2015). Dietary allicin reduces transformation ofL-carnitine to TMAO through impact on gutmicrobiota. J. Funct. Foods 15, 408–417. 10.1016/j.jff.2015.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woongjae Yoo J. K. Z., Nora J. F., Torres Teresa P., Shelton Catherine D., Shealy Nicolas G., Byndloss Austin J., et al. (2021). High-fat diet–induced colonocyte dysfunction escalates microbiota-derived trimethylamine N -oxide. Science 373 (6556), 813–818. 10.1126/science.aba3683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K. Y., Xia G. H., Lu J. Q., Chen M. X., Zhen X., Wang S., et al. (2017). Impaired renal function and dysbiosis of gut microbiota contribute to increased trimethylamine-N-oxide in chronic kidney disease patients. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 1445. 10.1038/s41598-017-01387-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Lin C. C., Yang Y., Yuan L., Wang P., Wen X., et al. (2019). Nobiletin prevents trimethylamine oxide-induced vascular inflammation via inhibition of the NF-κB/MAPK pathways.. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67 (22), 6169–6176. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b01270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajdel P., Marciniec K., Satala G., Canale V., Kos T., Partyka A., et al. (2016). N1-Azinylsulfonyl-1H-indoles: 5-HT6 receptor antagonists with procognitive and antidepressant-like properties. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 7 (6), 618–622. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. S., Davies S. S. (2016). Microbial metabolism of dietary components to bioactive metabolites: Opportunities for new therapeutic interventions. Genome Med. 8 (1), 46. 10.1186/s13073-016-0296-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Miikeda A., Zuckerman J., Jia X., Charugundla S., Zhou Z., et al. (2021). Inhibition of microbiota-dependent TMAO production attenuates chronic kidney disease in mice. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 518. 10.1038/s41598-020-80063-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Li Y., Yang P., Liu X., Lu L., Chen Y., et al. (2020). Trimethylamine-N-Oxide promotes vascular calcification through activation of NLRP3 (Nucleotide-Binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, pyrin domain-containing-3) inflammasome and NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) signals.. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 40 (3), 751–765. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhang C., Li H., Hou J. (2019). The presence of high levels of circulating trimethylamine N-oxide exacerbates central and peripheral inflammation and inflammatory hyperalgesia in rats following carrageenan injection. Inflammation 42 (6), 2257–2266. 10.1007/s10753-019-01090-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Zeisel S. H., Zhang S. (2015). Rapid LC-MRM-MS assay for simultaneous quantification of choline, betaine, trimethylamine, trimethylamine N-oxide, and creatinine in human plasma and urine. Electrophoresis 36 (18), 2207–2214. 10.1002/elps.201500055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Jin H., Ju H., Sun M., Chen H., Li L. (2022). Circulating trimethylamine-N-oxide and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 9, 828343. 10.3389/fmed.2022.828343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Jameson E., Crosatti M., Schafer H., RajaKumar K., Bugg T. D. H., et al. (2014). Carnitine metabolism to trimethylamine by an unusual Rieske-type oxygenase from human microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111 (11), 4268–4273. 10.1073/pnas.1316569111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]