Abstract

Survivors of critical illness face substantial challenges in their recovery, including physical and cognitive dysfunction. Resilience is the ability to adapt and maintain one’s mental health after facing such challenges. Higher resilience levels have been found to be beneficial throughout the illness trajectory in cancer patients, but resilience has not been widely researched in critical care patients. We undertook a scoping review to identify published studies on resilience following critical illness and describe: how resilience has been measured; the prevalence of low resilience in critical care patients; and what associations (if any) exist between resilience and clinical outcomes. We searched: PubMed, Medline, PsychINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, to identify relevant studies. We found 882 unique titles: 17 were selected for full text review, 10 were considered relevant. These included ICU inpatients and survivors, and trauma and sepsis survivors. A broad critical appraisal of each study was undertaken. The overall quality of published studies was low: there was wide variation in resilience-assessment tools across the studies, including the timing of measurement; only one used a validated tool. Estimates of low resilience ranged from 28%-67%, but with varying populations, high risk of inclusion bias, and small samples. Higher resilience levels were significantly associated with lower depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, pain, anger, executive dysfunction, and difficulty with self-care in critical care patients and survivors. Future studies should use validated resilience assessment, determine the optimum timing, and explore prevalence, associations with outcomes, and resilience-promoting interventions in non-selected or clearly defined populations.

Keywords: Resilience, psychological, critical care, critical illness, intensive care units, survivorship

Introduction

As intensive care unit (ICU) mortality has decreased, ICU-survivors have become an important focus of research. A 2016 matched-cohort study by Lone et al. reported that ICU-survivorship is associated with greater hospital resource use and 33% higher 5-year mortality than hospital patients; 1 25% of ICU-survivors in Scotland experienced unplanned hospital readmission within 90-days of hospital-discharge. 1 This represents a substantial burden on patients, caregivers, and society, highlighted when the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence made rehabilitation post-critical illness a quality standard. 2 ‘Post-Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS)’ describes new or worsening physical and mental-health problems that present following critical illness, affecting about 25% of patients. 3 This includes impaired cognition, psychological health, and physical function e.g. due to ICU-acquired neuromuscular weakness.3,4 Understanding how best to identify those at greatest risk of PICS, characterise individual issues and needs, and provide evidence-based interventions that improve the rate and degree of recovery are priorities for critical care research and practice. 5

Previous studies found pre-critical illness factors (e.g. comorbidities) were stronger predictors of hospital resource use and 90-day readmission than acute illness-factors in ICU-survivors.1,6 Barriers to ICU-recovery, which may trigger hospital readmission and contribute to poor health and well-being, were identified in a recent mixed-methods study, which reported many patients ‘struggling to cope’. 7 This study suggested resilience could be a relevant factor, but it was not formally measured or assessed as a possible issue influencing recovery. 7

Resilience is increasingly recognised as potentially important when recovering from illness or living with chronic conditions. 8 Psychological resilience is the capacity to maintain one’s mental health against adversity: it is a dynamic process of ‘bouncing back’. 9 Resilience is a complex multidimensional construct; its determinants include biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors which interact to determine response to stressful experiences. 10 It can be viewed as: a trait, process, or outcome, and exists on a continuum which can vary across multiple life domains, and change over time. 11 The nature of this complexity has led to substantial variation in the literature in how it is defined and measured. 12

Recent qualitative studies of ICU-survivorship indicate the complexity of the recovery journey, the multiple factors that contribute to personal recovery, and noted similarities with cancer survivorship.4,13 Resilience has been studied extensively in cancer populations, and is widely recognised as important in supporting patients during recovery. Research in cancer populations has found resilience to be a useful and protective trait throughout the illness trajectory; for example, greater resilience is associated with less anxiety and depression. 14 Importantly, resilience has been shown to be potentially modifiable in cancer patients through interventions, which can translate into greater well-being and recovery. 15 Given the similarities between a cancer diagnosis and an episode of critical illness in terms of a life-threatening life event with potential long-term psycho-social sequelae, it is possible that resilience is also important in ICU populations. This would require valid methods of measurement, and the development of resilience-promoting interventions that could support recovering patients with PICS. However, resilience has not been widely studied among ICU-survivors, and we found no review of available evidence.

We aimed to undertake a scoping review of published literature concerning resilience in a critical care population. We had three broad questions given the paucity of previous research on this topic in this population: first, to elucidate how resilience has been measured in critical care patients and survivors; second, what the prevalence of low resilience in critical care patients is in published research; and third, what associations (if any) exist between resilience and clinical outcomes including depression and anxiety.

Methods

Based on the Joanna Briggs Institute guidance, we chose a scoping review approach because the literature on resilience in a critical care population has not been comprehensively reviewed and is heterogenous, and because we aimed to address several questions (see above) rather than one specific systematic review question. 16 We aimed to understand the concept of resilience in relation to critical illness recovery, to broadly search and summarise the available literature, and to identify knowledge gaps. 17

We followed the principles recommended for undertaking scoping reviews. 18 We defined our population as critically ill patients, without restrictions relating to type of illness or time during the illness or recovery. Wherever possible, details of the population in terms of demographics and illness were extracted. The concept under review was resilience; broad search terms were used given this is an emerging area of research. We had no limitations based on geography, healthcare system, or demographic factors.

Full search details are available in Appendix 1.

We searched six databases (Medline, PubMed, PsychINFO, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature). A combination of keywords and MeSH headings were used with the intention of capturing all relevant literature. Reference lists of articles were searched to identify potentially relevant articles not identified with the main search terms. Resource issues meant we were unable to provide a comprehensive search of grey literature.

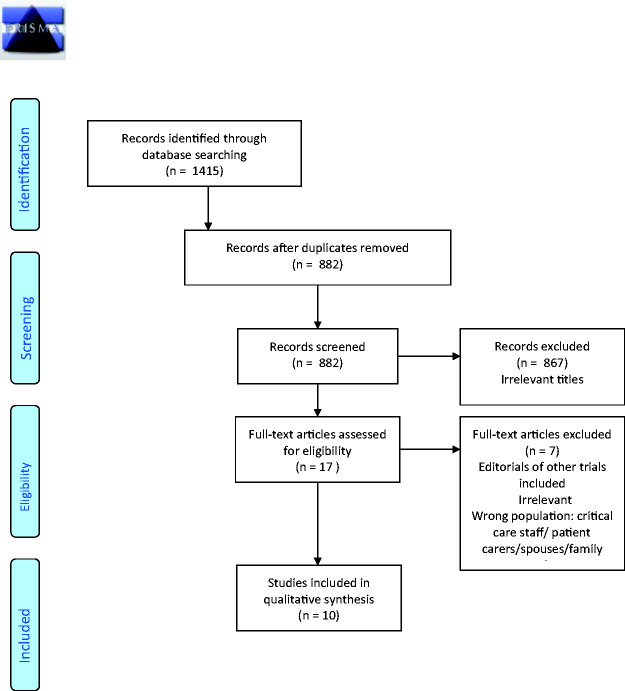

The results were screened by by title and abstract by two independent reviewers (EP and TW). Where reviewers were in disagreement, reasons for this were discussed and consensus was reached. Relevant articles were retrieved for full text reading to identify relevant studies. Results were managed using Mendeley. 19 Outcomes from the search terms and screening were summarised using a PRISMA flow-diagram. 20

As this was a scoping review no formal quality analysis or summary statistics were undertaken. A broad critical appraisal was undertaken to summarise strengths and weaknesses of each study.

The literature was summarised in tables organised by: title, study design, sample size, population, how resilience was measured and when, outcomes investigated, data collection, strengths, and weaknesses. We extracted data from the identified articles that mapped on to our three broad review questions and summarised this in a descriptive narrative and table.

Results

Literature searching (conducted on 15/12/2020) revealed 882 unique titles; screening titles revealed 29 considered relevant. Abstract searching revealed 17 records for full text review; 10 were considered relevant.21–30 One German study only published their abstract in English, so findings available in their abstract have been included. 21 Characteristics of the studies included and a broad qualitative appraisal is summarised in Table 1. The main findings from the evidence are summarised in Table 2.

Table 1.

Table summarising the characteristics to the studies included, organised by: study design, sample size, population included, how resilience was measured, when resilience was measured, outcome variables, data collection, strengths, weaknesses.

| Study | Study design | Sample size | Population | How resilience was measured | Timing of resilience measurement | Outcome variables investigated | Outcome data collection | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Resilience in Survivors of Critical Illness in the Context of the Survivors’ Experience and Recovery

Maley et al., 2016 23 |

Cross-sectional observational | 43 | Patients who survived admission to one of two medical ICUs in Pennsylvania ICU stay ≥2 days; not discharged to a hospice |

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (10-item); via telephone call using standardised script | 6-12 months after ICU discharge; Jan-May 2014 | Cognition (Health Utilities Index-3) Anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)) Depression (HADS) PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome 10-Questions Inventory) Mobility/social interaction (Life-Space Questionnaire) Quality of life (EuroQol EQ-5D-5L) |

Telephone-administrated self-reported questionnaires and interviewing | Used a validated tool to measure resilience. Used interviews in combination with questionnaires. Population from 2 different hospitals. Participants and non-participants not significantly different at baseline. |

Used short version of CDRISC – may not fully assess all psychometric properties of resilience. Self-reported measures open to reporting and recall bias. Cross-sectional design Small sample Low enrolment rate. Excluded patients discharged to a hospice. |

|

Psychosocial resiliency is associated with lower emotional distress among dyads of patients and their informal caregivers in the neuroscience intensive care unit

Shaffer et al., 2012 63 |

Cross-sectional observational | 87 patients, 99 carers | Patients of Neuro-ICU in a Boston hospital and their informal carers | Measured ‘resiliency factors’: Mindfulness Coping Intimate bond Self-efficacy All with self-reported questionnaires |

Within 2 weeks of admission to ICU – 85% within 2 days of admission | Emotional distress Anxiety Depression Anger The above were measured using Emotion Thermometers on a visual analog scale, 0-10. |

self-completed questionnaire completed at patient’s bedside in ICU | Participants completed questionnaires alone to minimise reporting bias. Measures were economical, easy to use, and have shown strong relations with more comprehensive measures. |

Did not use a validated resilience tool. Self-reported measures open to reporting and recall bias. Limited generalisability to non-neurological ICU patients. Cross sectional design Small sample size High non-respondent rate No comparison of participants and non-participants. |

|

Mindfulness and Coping Are Inversely Related to Psychiatric Symptoms in Patients and Informal Caregivers in the Neuroscience ICU: Implications for Clinical Care

Shaffer et al., 2016 24 |

Cross-sectional observational | 81 patients, 92 carers | Patients of Neuro-ICU in a Boston hospital and their informal carers | Measured ‘resiliency factors’: Mindfulness Coping With self-reported questionnaires. |

Within 2 weeks of admission to ICU | PTSD (Post-traumatic Checklist-Specific Stressor PCL-S) Anxiety (HADS) Depression (HADS) |

Self-reported measurement tools, completed at patient’s bedside in ICU | Participants completed questionnaires alone to minimise reporting bias. Measures were economical, easy to use, and have shown strong relations with more comprehensive measures. |

Did not use a validated resilience tool. Self-reported measures open to reporting and recall bias. Limited generalisability to non-neurological ICU patients. Cross sectional design Small sample size High non-respondent rate No comparison of participants and non-participants. |

|

Resilience and long-term outcomes after trauma: an opportunity for early intervention?

Nehra et al., 2019 23 |

Cross-sectional observational | 305 | Adult trauma patients with moderate-severe injury admitted to 1/3 level 1 trauma centres Excluded those with self-inflicted injuries |

3 questions assessed resilience as part of the study’s ‘Trauma quality of life survey (T-QoL)’ | 6 months after traumatic injury | Functional limitation (T-QoL) Return to work (asked during interview) Chronic pain (T-QoL) Composite mental and physical health scores (12-item short form health survey) PTSD (Seven-Item Breslau PTSD Screen) |

Self-reported measurement tools via telephone interview | Larger sample size. Participants and non-participants were comparable at baseline and injury-related characteristics. Excluded patients with self-inflicted injuries. |

Low enrolment rate. Cross sectional design Did not use a validated resilience scale. |

|

Physical and mental long-term sequelae following intensive care of severe sepsis in patients and relatives

*abstract only* Jaenichen et al., 2012 21 |

Cross-sectional observational | 87 | Patients who survived a severe sepsis and requested advice from the German Sepsis Aid’s National Helpline | Not explained in abstract | Not explained in abstract | Not explained in abstract | Not explained in abstract | N/A | N/A |

| Baseline resilience and depression symptoms predict trajectory of depression in dyads of patients and their informal caregivers following discharge from the Neuro-ICU. Meyers et al. 2020 27 |

Prospective longitudinal study | 102 patients, 103 carers | Patients admitted to Neuroscience ICU in a Boston Hospital and their informal carers | Measured ‘resiliency factors’: Mindfulness Coping |

Within 2 weeks of admission to ICU | Depression (HADS) |

Self-reported measurement tools, completed at patient’s bedside in ICU, then at 3 and 6 months contacted via email and completed via REDCap | Participants completed questionnaires alone to minimise reporting bias. Measures were economical, easy to use, and have shown strong relations with more comprehensive measures. Longitudinal design informed on how resilience affects depressive symptoms over time. |

Did not use a validated resilience tool. Self-reported measures open to reporting and recall bias. Limited generalisability to non-neurological ICU patients, and only recruited from one hospital. Small sample size High non-respondent rate No comparison of participants and non-participants. Only cognitively intact patients were included, excluding most critically ill patients in Neuro-ICU – risk of selection bias. |

| Baseline Resilience and Posttraumatic Symptoms in Dyads of Neurocritical Patients and Their Informal Caregivers: A Prospective Dyadic Analysis Meyers et al. 2020 28 |

Prospective longitudinal study | 102 patients, 103 carers | Patients admitted to Neuroscience ICU in a Boston Hospital and their informal carers | Measured ‘resiliency factors’: Mindfulness Coping |

Within 2 weeks of admission to ICU | PTSD (PCL-S) | Self-reported measurement tools, completed at patient’s bedside in ICU, then at 3 and 6 months contacted via email and completed via REDCap | Participants completed questionnaires alone to minimise reporting bias. Measures were economical, easy to use, and have shown strong relations with more comprehensive measures. Longitudinal design informed on how resilience affects PTSD symptoms over time. |

Did not use a validated resilience tool. Self-reported measures open to reporting and recall bias. Limited generalisability to non-neurological ICU patients, and only recruited from one hospital. Small sample size High non-respondent rate No comparison of participants and non-participants. Only cognitively intact patients were included, excluding most critically ill patients in Neuro-ICU – risk of selection bias. |

| The Impact of Resilience Factors and Anxiety During Hospital Admission on Longitudinal Anxiety Among Dyads of Neurocritical Care Patients Without Major Cognitive Impairment and Their Family Caregivers Meyers et al. 2020 29 |

Prospective longitudinal | 102 patients, 103 carers | Patients admitted to Neuroscience ICU in a Boston Hospital and their informal carers | Measured ‘resiliency factors’: Mindfulness Coping |

Within 2 weeks of admission to ICU | Anxiety (HADS) | Self-reported measurement tools, completed at patient’s bedside in ICU, then at 3 and 6 months contacted via email and completed via REDCap | Participants completed questionnaires alone to minimise reporting bias. Measures were economical, easy to use, and have shown strong relations with more comprehensive measures. Longitudinal design informed on how resilience affects PTSD symptoms over time. |

Did not use a validated resilience tool. Self-reported measures open to reporting and recall bias. Limited generalisability to non-neurological ICU patients, and only recruited from one hospital. Small sample size High non-respondent rate No comparison of participants and non-participants. Only cognitively intact patients were included, excluding most critically ill patients in Neuro-ICU – risk of selection bias. |

| Recovering together: building resiliency in dyads of stroke patients and their caregivers at risk for chronic emotional distress; a feasibility study Bannon et al. 2020 31 |

Feasibility randomised controlled trial | 20 patients, 20 carers | Patients admitted to a Neuroscience ICU in a Boston Hospital and their informal carers (within 1 week of hospitalisation) – either patient or carer/both had to screen for clinically significant depression or anxiety or PTSD | Measured ‘resiliency factors’: Mindfulness Coping Self-efficacy Interpersonal bond |

Pre- and post-treatment (6 weeks) and at 12 week follow up | Feasibility of intervention, satisfaction (Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire CEQ, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire CSQ-3) Depression (HADS) Anxiety (HADS) PTS (PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version PCL-C) |

Self-reported measurement tools, completed at patient’s bedside in ICU on paper, then ‘posttreatment’ (6 weeks), and at 3 months electronically via REDCap | Allowed lessons to be learned to implement in the future RCT to improve feasibility Good adherence to sessions and follow-up questionnaires |

Many dyads were missed before study staff were able to approach Control intervention was not matched Participants were not blinded |

| Feasibility and Efficacy of a Resiliency Intervention for the Prevention of Chronic Emotional Distress Among Survivor-Caregiver Dyads Admitted to the Neuroscience Intensive Care Unit: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Vranceanu et al. 2020 30 |

Single-blinded pilot randomised controlled trial | 58 patients, 58 carers | Patients admitted to a Neuroscience ICU in a Boston Hospital and their informal carers– either patient or carer/both had to screen for clinically significant depression or anxiety or PTSD | Measured ‘resiliency factors’: Mindfulness Coping |

Pre- and post-treatment (6 weeks) and at 12 week follow up | Feasibility of intervention, satisfaction (CEQ, CSQ-3) Depression (HADS) Anxiety (HADS) PTS (PLC-C) |

Self-reported measurement tools, completed at patient’s bedside in ICU on paper, then ‘posttreatment’ (6 weeks), and at 3 months electronically via REDCap | Trialled a novel intervention. Single-blinded design reduced reporting bias. RCT design allowed comparison with a basic education-based control intervention. |

Pilot study – sample size was small therefore may be underpowered to detect differences in mindfulness/coping between groups. Did not use stratified randomisation so samples may have been unbalanced. Dyads may have been missed as one member had to endorse emotional distress during the patient’s ICU stay to participate – this may have developed at a later date. Relatively homogenous group – may not be generalisable beyond these baseline characteristics i.e. educated, white. Self-reported measurements risked reporting bias. |

N/A: not applicable: strengths and weakness could not be assessed as only the abstract was available in English

Table 2.

Summary of the evidence found by this review mapped onto 3 broad questions: how resilience has been measured in critical care patients/survivors, what the prevalence of low resilience in critical care patients is in published research; and what associations (if any) exist between resilience and clinical outcomes including depression and anxiety, along with other findings in this review.

| Scoping review questions | Number of sources of evidence | Key findings | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| How resilience was measured | 10 | Used a validated tool 1 | Maley et al. used the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CDRISC) 33 administered via telephone interview 23 |

| Measured resiliency factors 7 | Shaffer et al., Meyers et al., Bannon et al. and Vranceanu et al.’s studies measured mindfulness and coping25–31 ‘Mindfulness’ was defined as the ability to remain present and defer judgement in the face of adversity. It was measured using the Cognitive Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised. ‘Coping’ was defined as the arsenal of cognitive, behavioural, or emotional skills that an individual can rely on to manage stress. It was measured using the Measure of Current Status-Part A. One of Shaffer’s studies 25 , and Bannon et al. 30 also measured intimate bond and self-efficacy.‘Intimate bond’ was defined as empathetic interpersonal interactions that meet one’s emotional and functional needs. It was measured using The Intimate Bond Measure.‘Self-efficacy’ was defined as one’s perceived resourcefulness to adapt under adversity. It was measured using the General Self-Efficacy Scale. |

||

| Used a bespoke tool 1 | Nehra et al. used their own bespoke tool – ‘Trauma Quality of Life Instrument’. This included 3 questions on a 5-point Likert scale. 24 | ||

| N/A 1 | Jaenichen et al.’s abstract did not describe how resilience was measured. 22 | ||

| Prevalence of low resilience | 2 | Maley et al. reported low resilience in 28% (12) of ICU-survivors 23 | Resilience was normal in 63% (27) and high in 9% (4).

20

They defined low resilience as ≤26/40, normal as 27-37/40, high as ≥38/40 on the CDRISC22,31 Median population resilience was 29/40 (range = 25-34). 22 |

| Nehra et al. reported resilience was low in 67% (87) of trauma survivors who were in ICU 24 | Resilience was high in 33% (42)

24

They defined low resilience as scores <=1 on their tool, and high as ≥2. 24 There was no difference between patients with low versus high resilience regarding having an ICU admission or not (p = 0.86) 24 |

||

| Association between resilience and clinical outcomes | Anxiety 5 | 5 studies reported that greater resilience/resiliency factors was significantly associated with lower anxiety 22 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 28 | 1. Resilience was inversely correlated with anxiety in ICU-survivor patients (r=−0.49, p ≤ 0.001)

23

2. Greater mindfulness was associated with less anxiety (r=−0.45, p < 0.001) in Neuro-ICU patients. Coping was not significantly associated with anxiety (r=−0.27, p < 0.05). 26 3. Greater mindfulness (r=−0.55, p < 0.0001) and coping (r=−0.32, p < 0.01) were associated with lower anxiety (22) 4. Higher mindfulness at baseline was associated with lower anxiety at baseline (r=−0.575, p < 0.001), 3 months (r=−0.479, p < 0.001), and 6 months (r=−0.505, p < 0.001) in Neuro-ICU patients. 26 Higher coping at baseline was associated with lower anxiety at baseline (r=−0.372, p < 0.001), 3 months (r=−0.373, p < 0.001), and 6 months (r=−0.284, p < 0.05), in Neuro-ICU patients 29 5. Jaenichen et al.’s abstract reported a significant negative association between resilience and anxiety 22 |

| Depression 5 | 5 studies reported that greater resilience/resiliency factors was significantly associated with lower depression 22 , 22 ,24–26 | 1. Resilience was inversely correlated with depression in ICU-survivor patients (r=−0.47, p ≤ 0.01)

23

2. Greater mindfulness (r=−0.49, p < 0.001) and coping (r=−0.30, p < 0.01) was associated with lower depression in Neuro-ICU patients. Greater self efficacy was associated with lower depression (r=−0.30, p < 0.01) 26 3. Greater mindfulness (r=−0.48, p < 0.001) and coping(r=−0.51, p < 0.001) was associated with lower depression in Neuro-ICU patients 25 4. Higher mindfulness at baseline was associated with lower depression at baseline (r=−0.457, p < 0.001), 3 months (r=−0.429, p < 0.001), and 6 months (r=−0.368, p < 0.001) in Neuro-ICU patients 24 . Higher coping at baseline was associated with lower depression at baseline (r=−0.491, p < 0.001), 3 months (r=−0.335p < 0.001), and 6 months (r=−0.194, p > 0.05), in Neuro-ICU patients 27 5. Jaenichen et al.’s abstract reported a significant negative association between resilience and depression 22 |

|

| PTSD 6 | 6 studies reported that greater resilience/resiliency factors was significantly associated with lower PTSD22–26, 27 | 1. Resilience was inversely correlated with PTSD in ICU-survivor patients (r=−0.53, p < 0.001)

23

2. Greater mindfulness (r=−0.35, p < 0.01) and self-efficacy (r=−0.30 p < 0.01) were significantly associated with lower distress in Neuro-ICU patients. Coping (r=−0.25) and intimate bond (r=−0.13) were not significantly associated with distress (p > 0.05) 26 3. Greater mindfulness was associated with lower PTSD (r=−0.54, p < 0.001) in Neuro-ICU patients; coping also significantly associated with lower PTS (r=−0.34, p < 0.01) 25 4. Higher mindfulness at baseline was associated with lower PTSD at baseline (r=−0.387, p < 0.001), 3 months (r=−0.331, p < 0.05), and 6 months (r=−0.246, p > 0.05) in Neuro-ICU patients 25 . Higher coping at baseline was associated with lower PTSD at baseline (r=−0.620, p < 0.001), 3 months (r=−0.433, p < 0.001), and 6 months (r=−0.409, p < 0.001), in Neuro-ICU patients 28 5. Trauma survivor patients with low resilience were more likely to screen positive for PTSD (OR = 2.96, 1.58-5.54, p = 0.001) 24 6. Jaenichen et al.’s abstract reported a significant negative association between resilience and PTSD 22 |

|

| Other 1 | Executive dysfunction | Resilience was inversely correlated with executive dysfunction (r=−0.34, p < 0.05) 23 | |

| 2 | Difficulty with self-care/activities of daily living | 1. Resilience was inversely correlated with difficulty with self care (r=−0.32, p < 0.05)

23

2. Trauma survivors with low resilience had higher odds of functional limitations in activities of daily living (OR = 4.81, 2.48-9.34, p < 0.001) 24 |

|

| 3 | Pain | 1. Resilience was inversely correlated with pain (r=−0.33, p < 0.05)

23

2. Trauma survivors with low resilience were less likely to report chronic pain (OR = 2.57, 1.54-4.3, p < 0.001) 24 .3. Jaenichen et al.’s abstract reported a significant negative association between resilience and physical complaints 22 . |

|

| 1 | Anger | Greater mindfulness was associated with less anger (r=−0.45, p < 0.001) 26 .Greater coping and intimate bond was associated with less anger (r=−0.31, p < 0.01; r=−0.36 p < 0.01) 26 | |

| 1 | Return to work/school | Trauma survivors with low resilience were less likely to have returned to work or school at 6 months (OR = 3.25, 1.71-6.19, p < 0.001) 24 | |

| 5 | Dyadic relationships | 1. Patients’ psychosocial resiliency factors were not associated with their partners’ resiliency or emotion domains

26

2. One’s own mindfulness was independently related to one’s partner’s depressive symptoms 25 3. For both patients and caregivers, baseline mindfulness predicted partner's degree of depressive symptoms at baseline (p = 0.03), but not at 3-, and 6-month follow-up (ps > 0.09) 27 4. Own degree of PTS symptoms at 3 months predicted worse PTS symptoms in one's partner at 6 months, for both patients and caregivers (p = 0.02)28 5. For both patients and caregivers, one’s own baseline mindfulness predicted their partner’s anxiety symptoms 3 months later (p = 0.008), but not at 6 month follow-up 29 |

|

| Other relevant studies i.e. intervention trial | 3 | The feasibility 31 and efficacy 30 randomised controlled trials testing the ‘Recovering together’ intervention suggest that resiliency factors are modifiable, and this is potentially efficacious in improving depression, anxiety, and PTS following Neuro-ICU admission. This suggests a dyadic approach to interventions may be effective. | 1. Feasibility of enrolment (87%), satisfaction (11.33/12 for patients), and adherence to treatment (6/7 dyads attended 4/6 sessions) was good. There were no technical difficulties. Participation was associated with clinically significant decrease in patient depression, anxiety, and PTS symptoms from baseline to post-test: medium-large effect sizes: (d=−0.41, -1.25, -0.83 respectively). Gains in resiliency variables demonstrated small-large effect sizes (d = 0.07-0.85) in Recovering Together but not in the control intervention. Lessons were learned to inform future research in next trial.

30

2. 86% of dyads completed 4/6 sessions. Satisfaction levels were high – 98% endorsed scores higher than the midpoint on the Client Satisfaction Scale. Participation in RT was associated with statistically and clinically significant improvement between baseline and postintervention in survivors for depression (-3.4 difference , p = 0.002), anxiety (-6.3 difference, p < 0.001), PTS (-12.3 difference, p < 0.001). There was a statistically significant increase in survivor’s coping (difference 0.6, p = 0.002), but no other significant differences (e.g. in mindfulness) 30 |

One study’s population was 43 ICU-survivor patients contacted six to twelve months after hospital discharge to home. 22 Seven studies’ population was Neuroscience-ICU patients from Massachusetts General Hospital recruited within two weeks of ICU-admission, and their ‘informal-carers’ (patients and carers were investigated as dyads);24–30 Shaffer et al. included 87 patients and 99 carers in one study, 25 and 81 patients and 92 carers in another, 24 Meyers et al. included 102 patients and 103 carers in three studies.26–28 Bannon et al. included 20 dyads, 30 and Vranceanu et al. included 58 dyads. 29 One study included 305 Level-1 trauma centre patients with Injury Severity Scores >=9, of which 129 (42.3%) were admitted to ICU. 23 One study (abstract only available) included 87 severe sepsis survivors who requested advice from the German Sepsis Aid’s National Helpline. 21

Qualitative quality appraisal

Three studies had prospective longitudinal designs: resiliency factors and clinical outcomes were measured at baseline, 3-months, and 6-months.26–28 This allowed temporal, causal relationships between resilience and the outcomes to be explored, which was not possible in the five cross-sectional studies included.21–25 One study was a single-blinded randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a resiliency intervention (‘Recovering Together’ (RT)), 29 one was the feasibility trial which preceded this. 30 All sample sizes were relatively small, therefore results may not be generalisable to all ICU-patients and were open to chance effects. Seven studies were conducted in the same, single hospital, therefore the generalisability of the overall findings is potentially limited.24–30 Low inclusion rates risked selection bias. Only studies based in the United States or Germany were found, and other regions’ populations may significantly differ as cultural factors can impact resilience, such as attachments to caregivers and spiritual beliefs. 32 Self-reported questionnaire use risked reporting bias. The timing of measuring resilience, the population included, the method for resilience measurement and therefore how it was defined, was inconsistent across the studies.

How resilience was measured

Maley et al. used the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CDRISC) to measure resilience, 31 administered through telephone interview. Shaffer, Meyers, Bannon, and Vranceanu et al. measured resilience indirectly via ‘resiliency factors’, mindfulness and coping, using self-reported questionnaires, completed at ICU-beside at baseline, then online at follow-up.25–31 Two studies also measured ‘intimate bond’ and ‘self-efficacy’.25,30 Nehra et al. used their own bespoke tool (Trauma Quality of Life Measurement). 23 Jaenichen et al.’s abstract did not describe how resilience was measured. 21

Prevalence of low resilience

2 studies reported on the prevalence of low resilience:22,23 Maley et al. reported low resilience in 28% (12) of ICU-survivors, 22 which they defined as ≤26/40 on the CDRISC. The median population resilience was 29/40 (range = 25-34). 22 Nehra et al. reported low resilience in 67% (87) of trauma survivors who were admitted to ICU, which they defined as ≤1 on their tool. 23

Associations between resilience and clinical outcomes

5 studies investigated associations between resilience and anxiety,21,22,24,25,28 5 studies investigated depression,21,22,24–26 and 6 studies investigated symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).21–25,27 Maley et al. and Jaenichen et al. reported significant negative associations between resilience and anxiety, depression, and PTS in ICU 22 and sepsis 21 survivors respectively. Both studies by Shaffer et al. reported greater mindfulness, defined as a higher score on the Cognitive Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised, 33 as significantly associated with lower anxiety, depression, and PTS in Neuro-ICU patients.24,25 Meyers et al. reported this was also true at 3 and 6-month follow-up27–29 (except for lower PTSD at 6-months, (p > 0.05) 28 ). Both Shaffer et al.’s studies found higher coping was significantly associated with lower depression;24,25 but only one found higher coping was significantly associated with anxiety or PTS. 25 At baseline and 3-month follow-up, Meyers found that higher coping was significantly associated with lower anxiety, 28 depression, 26 and PTS. 28 The same was true at 6-months for only PTS.27–29 Shaffer et al. reported greater mindfulness and self-efficacy were associated with lower distress, but greater coping or intimate bond was not. 25

Higher resilience was significantly inversely correlated with executive dysfunction, 22 difficulty with self-care, 22 pain,21–23 functional limitations in activities of daily living, 23 and not returning to work or school at 6-months in ICU-survivors. 23 Greater mindfulness, coping, and intimate bond were associated with less anger in Neuro-ICU patients. 25 Shaffer et al. and Meyers et al. found that patient and carer resiliency levels were interdependent.24–28

Modifying resilience

2 studies described RT, a novel intervention delivered through 6 weekly sessions teaching mindfulness, cognitive-behavioural, and positive psychology skills, aiming to improve resilience in patient-carer dyads.29,30

Bannon et al. aimed to test the feasibility and highlight areas for methodological improvement. 30 This included suggesting making research staff available in the Neuro-ICU everyday to avoid missing eligible patients, and collaborating with nursing staff so they could refer for participation patients who were mentally able to enrol, to avoid approaching ineligible patients. 30 Vranceanu et al. found RT was associated with a significant increase in survivor coping skills, 29 but not mindfulness, and Vranceanu and Bannon’s RCTs found RT was associated with statistically and clinically significant improvements in depression, anxiety and PTSD compared to the ‘educational-control’.29,30

Discussion

We conducted a scoping review of the published literature on resilience in critical care patients, with a focus on: how resilience was measured, the prevalence of low resilience in this population, and potential relationships between resilience and clinical outcomes. To our knowledge this is the first review undertaken on this topic in critically ill patients. We found a wide range of approaches were used to measure resilience, and a validated tool was only used in one study. The timing varied widely between studies. The quality of the studies and the wide variation in assessment tools and populations meant the prevalence of low resilience among critical care survivors could not be reliably estimated. Despite widely varying designs, many studies suggested an association between low resilience and greater prevalence of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, and a range of other adverse outcomes that are known components of PICS. We found no high-quality studies investigating whether identifying low resilience and providing interventions to support these patients could improve critical illness recovery or PICS features.

Strengths and limitations

Our scoping review approach allowed us to undertake a broad review of the available literature; This was appropriate given resilience is a new area of interest in the critically ill. In contrast to a systematic review, we pre-defined three relevant questions rather than a single question, which allowed several issues to be examined from the published literature. The search strategy was intentionally broad to identify all relevant studies. Although not formally required in scoping review methodology, we conducted a qualitative quality assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the studies, which was informative for future work. The nature and design of the studies meant meta-analysis was not feasible or appropriate so we used a narrative approach to summarise the data as recommended for scoping reviews. Our review has limitations: it is possible that some studies were missed, and we did not use a formal quality assessment tool. We did not search the ‘grey’ literature because we had inadequate resource to do this during the lead author’s period of study. Only one independent reviewer extracted data, although this may be less likely to introduce bias in scoping reviews which largely aim to describe available information.

Meaning of our findings

Maley et al. and Nehra et al.’s studies suggest there is a high prevalence of low resilience in the critical care survivor population.22,23 However, these findings may have limited generalisability to all ICU-survivors as both studies had relatively small sample sizes and were from one centre in the USA.22,23 In most studies it was unclear whether included patients were representative of total ICU populations, and in those where prevalence of low resilience was described low enrolment rates occurred (27%, 22 43% 23 respectively). These factors increase the risk of selection bias, and suggest the available literature does not enable an estimation of the true prevalence of low resilience among ICU-survivors or the factors that may be associated with it. Neither study included comparator data on resilience in the general population or non-critically ill patients.22,23

The widely varying methods used to measure resilience further complicate the interpretation of the literature. As resilience is a multidimensional complex construct, using validated tools that capture all relevant aspects is important. Validated resilience measurement tools are available and future studies should use these to enable comparisons between studies, with the general population, and other patient groups. Windle et al. reviewed 19 resilience measures: 10 although no ‘gold standard’ has been defined and all measures lacked assessment of some psychometric properties of resilience, the CDRISC was amongst the 3 best-rated measures.10,31 Only one study included in this review used this validated tool. The timing of resilience assessment was also highly variable, ranging from within the ICU to later during post-ICU recovery. Given the prevalence of cognitive impairment and ongoing physical impairments in the early post-ICU period, these could confound assessment of resilience if measured at this time. Our review shows that future studies should determine which validated tools are most appropriate for ICU-survivors, and the optimum time to administer them following ICU-discharge if the aim is to triage patients for interventions to support longer term recovery from PICS. Comparison between the studies was limited as the tools used to measure clinical outcomes e.g. PTSD varied widely, and these may have assessed different properties.

Despite the small sample, Vranceanu’s study suggests that targeting resilience in future interventions may benefit critical care survivors and help support them in their recovery. 29 Future trials enrolling larger samples from a range of different ICUs are indicated. The co-dependent dyadic relationships between resiliency and outcomes described24–30 suggests that targeting patient-carer dyads in future interventions may be effective.

Comparison with other population

Two reviews of the published literature on resilience in cancer patients reported that resilience is independently associated with health and psychosocial outcomes.8,14 In patients undergoing cancer treatment, more resilient patients reported less anxiety and depression; higher physical, emotional, social functioning; and a better quality of life than those with lower resilience.8,14 Similar outcomes were reported in cancer survivors, which is consistent with the present review’s findings.8,14

The generalisability of these findings to critical care patients is limited as the populations involved are heterogeneous, such as in terms of age and comorbidities. However, many challenges involved in PICS and in cancer diagnosis, treatment and remission processes overlap, for example: depression, weakness, and fatigue. A grounded theory-based study of ICU-survivorship found many similarities with cancer survivorship from a person perspective, suggesting resilience could be relevant to recovery. 34

A review of 22 trials including 2912 patients reported on interventions to promote resilience in cancer. 15 The SMART intervention, a cognitive-behavioural therapy programme, significantly improved resilience and quality of life, and reduced anxiety symptoms, in breast cancer survivors relative to the control group37. Interventions including 12 or more ‘sessions’ including behavioural therapy, mindfulness, positive psychology, and supportive-expressive group therapy, produced beneficial effects on resilience and post-traumatic growth in acutely ill and post-cancer patients. 15 Greater effect sizes were achieved with greater duration of interventions, and when interventions were provided immediately after diagnosis, in parallel with medical cancer therapies such as chemotherapy. 35 The similarities between the issues faced by cancer survivors and those recovering from critical illness with PICS suggest resilience should be studied further in the ICU-survivor population. The benefits found in cancer survivors from resilience-focussed interventions also suggests future research to evaluate the impact of resilience-increasing interventions in ICU-survivors is justified, given recovery from critical illness is also a complex, long-term process. 34

Conclusion

This review suggests measuring and addressing low resilience may be important in critical care survivors. The most valid way to measure resilience in this population is uncertain, and the prevalence of low resilience uncertain given the heterogenous tools used. Future high quality studies including larger sample sizes with higher enrolment, on screening for low resilience with validated tools or on resilience-promoting interventions in critical care patients are indicated to determine if, like in the cancer literature, resilience is modifiable and important in this population.

Appendix 1. Search strategy

We initially used a deliberately broad search (to capture all relevant sources and give an approximation of how much literature was available) in Scopus to identify the main subject areas which the literature existed in.

We used the terms:

Resilience

‘critical care’ OR ‘ICU’ or ‘intensive care’

This yielded 42071 results (15/12/2020). The top subject areas were:

Medicine (16836)

Social Sciences (14510)

Psychology (10093)

Nursing (4090)

Environmental Science (2700)

Based on this, we decided that the databases: Medline, Pubmed, and PsychINFO were appropriate and relevant to conduct the search in. After analysing the text words contained in the titles and abstracts of papers retrieved from these searches, and the descriptive index terms, a literature search was conducted in: Medline, Pubmed, PsychINFO, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature).

In order to capture all of the relevant publications, we used keywords and the relevant MeSH (Medical Subject Heading) combined with OR. The keyword ‘resilience’ and its relevant MeSH heading was selected as this is the construct being investigated; the keywords ‘acute care’, ‘ICU’, ‘intensive care’ and ‘critical care’ were used to capture all of the relevant population (ICU patients), and were combined with the relevant MeSH headings, and this was further focussed with the keyword ‘patient*’ to further focus this to patients and patient-centred outcomes.

Medline search strategy (16/12/2020):

Resilience

RESILIENCE, PSYCHOLOGICAL/

1 or 2

Critical Care/

Intensive Care Units/

Critical Illness/

4 or 5 or 6

‘acute care’ or ‘ICU’ or ‘intensive care’ or ‘critical care’

7 or 8

Patient*

9 and 10

3 and 11

After retrieving papers from these 6 databases, we exported all the results (1415) to Mendeley and used the ‘Find Duplicates’ tool and hand-searching to remove all duplicate titles (533). We then read the titles, abstracts, then full texts, excluding papers at each stage of this which did not satisfy inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were: original journal article, available in English, measuring resilience in some way, with adult ICU patients or survivors as the population.

Many papers retrieved in searching were considered irrelevant as the populations were nursing/critical care staff or family members of patients. After screening, 9 articles (and 1 abstract) met these specific criteria. We screened the reference lists of these texts for other potential relevant papers for inclusion. See PRISMA diagram for full details of this process.

Appendix 1 - Literature search

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Ellen Pauley https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6994-9722

References

- 1.Lone NI, Gillies MA, Haddow C, et al. Five year mortality and hospital costs associated with surviving intensive care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194: 198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Excellence NI for health and C. Rehabilitation after critical illness in adults. NICE guidance, www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs158/resources/rehabilitation-after-critical-illness-in-adults-pdf-75545546693317 (2017, accessed 15 April 2019).

- 3.Rawal G, Yadav S, Kumar R. Post-intensive care syndrome: an overview. J Transl Int Med 2017; 5: 90–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lone NI, Seretny M, Wild SH, et al. Surviving intensive care: a systematic review of healthcare resource use after hospital discharge*. Crit Care Med 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James Lind Alliance. The Priority Setting Partnerships (Online). Intensive Care Top 10.

- 6.Lone NI, Lee R, Salisbury L, et al. Predicting risk of unplanned hospital readmission in survivors of critical illness: a population-level cohort study. Thorax 2019; 74: 1046–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donaghy E, Salisbury L, Lone NI, et al. Unplanned early hospital readmission among critical care survivors: a mixed methods study of patients and carers. BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 27: 915–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seiler A, Jenewein J. Resilience in cancer patients. Front Psychiatr 2019; 10: 208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comaz Diaz L. The road to resilience. American Psychological Association, www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx (2018, accessed 15 April 2019).

- 10.Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011; 9: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Windle G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev Clin Gerontol 2011; 21: 152–169. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hee Lee J, Kyung Nam S, Kim A. Resilience: a meta‐analytic approach. J Couns Dev 2013; 91 Epub ahead of print DOI: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00095.x. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith DM, Salisbury LG, Lee RJ, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life after ICU. Crit Care Med 2018; 46: 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molina Y, Yi JC, Martinez-Gutierrez J, et al. Resilience among patients across the cancer continuum: diverse perspectives. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2014; 18: 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joyce S, Shand F, Tighe J, et al. Road to resilience: a systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e017858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18: 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P. Chapter 11: scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (eds) JBI manual for evidence synthesis. 2020. Epub ahead of print 2020. DOI: 10.46658/JBIMES-20-12.

- 18.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendeley Desktop.

- 20.Moher D, PRISMA Group, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaenichen D, Brunkhorst FM, Strauss B. [Physical and mental long-term sequelae following intensive care of severe sepsis in patients and relatives]. Korperliche und Psych Langzeitfolgen nach Intensivmed Behandlung einer schweren Sepsis bei Patienten und Angehor 2012; 62: 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maley JH, Brewster I, Mayoral I, et al. Resilience in survivors of critical illness in the context of the survivors’ experience and recovery. Annals ATS 2016; 13: 1351–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nehra D, Herrera-Escobar JP, Al Rafai SS, et al. Resilience and long-term outcomes after trauma: an opportunity for early intervention? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2019; 87: 782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaffer KM, Riklin E, Jacobs JM, et al. Mindfulness and coping are inversely related to psychiatric symptoms in patients and informal caregivers in the neuroscience ICU. Crit Care Med 2016; 44: 2028–2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaffer KM, Riklin E, Jacobs JM, et al. Psychosocial resiliency is associated with lower emotional distress among dyads of patients and their informal caregivers in the neuroscience intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2016; 36: 154–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyers E, Lin A, Lester E, et al. Baseline resilience and depression symptoms predict trajectory of depression in dyads of patients and their informal caregivers following discharge from the Neuro-ICU. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2020; 62: 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyers EE, Shaffer Km, Gates M. Baseline resilience and posttraumatic symptoms in dyads of neurocritical patients and their informal caregivers: a prospective dyadic analysis. Psychosom J Consult Liaison Psychiatry 2019; No-Specified. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Meyers EE, Presciutti A, Shaffer KM, et al. The impact of resilience factors and anxiety during hospital admission on longitudinal anxiety among dyads of neurocritical care patients without major cognitive impairment and their family caregivers. Neurocrit Care 2020; 33: 468–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vranceanu A-M, Bannon S, Mace R, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a resiliency intervention for the prevention of chronic emotional distress among survivor-caregiver dyads admitted to the neuroscience intensive care unit: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e2020807–e2020807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bannon S, Lester EG, Gates MV, et al. Recovering together: building resiliency in dyads of stroke patients and their caregivers at risk for chronic emotional distress; a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2020; 6. Epub ahead of print DOI: 10.1186/s40814-020-00615-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CDRISC). Depress Anxiety 2003; 18: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ungar M. Resilience across cultures. Br J Soc Work 2006; 38: 218–235. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman G, Hayes A, Kumar S, et al. Mindfulness and emotion regulation: the development and initial validation of the cognitive and affective mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2007; 29: 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kean S, Salisbury LG, Rattray J, et al. Intensive care unit survivorship’ – a constructivist grounded theory of surviving critical illness. J Clin Nurs 2017; 26: 3111–3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loprinzi CE, Prasad K, Schroeder DR, et al. Stress management and resilience training (SMART) program to decrease stress and enhance resilience among breast cancer survivors: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Clin Breast Cancer 2011; 11: 364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]