Purpose

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth use in the United States increased dramatically as providers shifted their modes of practice to decrease risks of exposure to the virus.1,2 During this time, telehealth use for behavioral health conditions far exceeded its use for general physical health conditions.1,2Telehealth includes health services rendered via interactive, synchronous or asynchronous, audio and video telecommunication systems. Overall, rates of telehealth use for all conditions declined later in 2020, as the initial COVID-19 surge abated.1 However, these declines were primarily driven by visits for physical health conditions, while rates for behavioral health conditions remained consistently high throughout 2021.2,3

These early data suggest that the use of telehealth for behavioral health conditions resonates with both patients and providers and may be a vital component to continue to include in benefit packages offered by employers to support the well-being of their employees. These data also suggest that expanded telehealth benefits and reduced cost sharing for telehealth visits among self-insured plans and other commercial insurers in some states4 incentivized the uptake of telehealth in the early months of the pandemic. Given the increase in the reported prevalence of behavioral health conditions during the pandemic,5,6 continuing disruptions to the workforce due to resignations7 and work-from-home policies,8-10 and evidence of increased burnout overall,11 the continued expansion of access to behavioral health services via telehealth is an important consideration for employers.

To date, analyses of the use of telehealth during the pandemic have not stratified trends for behavioral health telehealth visits by substance use disorder (SUD) vs mental health conditions. Employers need information about trends across these 2 broad groups to inform benefit design. The purpose of this analysis was to examine trends in (1) the delivery of telehealth by behavioral health care providers compared with general health care providers and (2) the use of telehealth for behavioral health care stratified by mental health conditions and substance use conditions. Our study time frame extends through November 2021 to allow for the observation of trends before and after the surge of the Delta variant of COVID-19.

Methods

Sample

The data used for this analysis, covering January 2020 through November 2021, were from the IBM® MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases, combining annual, quarterly, and early view releases. During this period, these claims databases represented the health services of approximately 26 million employees, dependents, and retirees in the United States with primary or Medicare coverage through privately insured fee-for-service, point-of-service, or capitated health plans. More than 70% of the data came from large, self-insured employers. The remaining data came from health plans that serve a variety of employer clients.

Design, Measures, and Analysis

We examined approximately 849 million outpatient service records during this period for use of telehealth services. Telehealth was identified from the outpatient files using a combination of place of service codes (Telehealth, value 02) and the procedure modifier codes listed in Table 1. Using a combination of codes ensured inclusion of both audio and video telehealth modalities. We categorized data using key major behavioral health diagnostic groups and bundled them into mental health or SUD diagnostic groups as well as groups for selected provider types. We conducted a descriptive trend analysis using the World Programming System (WPS) 4.3.12

Table 1.

Procedure Modifier Codes in Health Claims Used to Identify Telehealth.

| Code | Definition |

|---|---|

| 95 | Synchronous telemedicine service rendered via real-time interactive audio and visual telecommunication system |

| GO | Telehealth services for diagnosis, evaluation, or treatment of symptoms of acute stroke |

| GQ | Telehealth service rendered via asynchronous telecommunications system |

| GT | Telehealth service rendered via interactive audio and video telecommunication systems |

The IBM MarketScan Research Databases contain statistically deidentified data that are fully compliant with U.S. privacy laws and regulations, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Such data are exempt from institutional review board approval.

Results

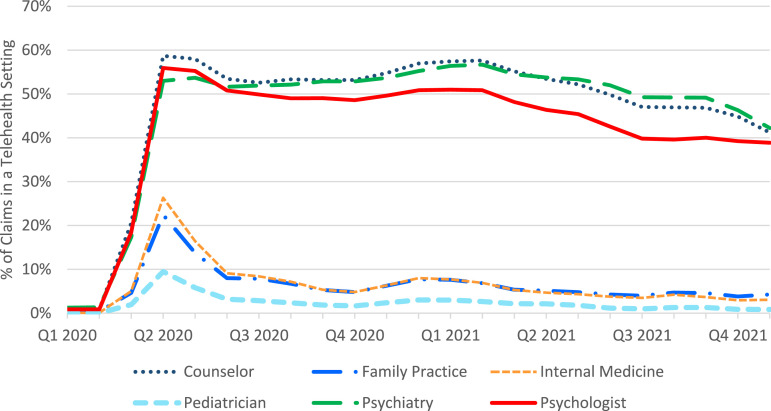

As the COVID-19 pandemic began to affect the U.S. health care system, providers who treat mental health and SUD diagnoses (i.e., counselors, psychiatrists, and psychologists) saw a rapid rise in telehealth claims, from about 1% in February 2020 to about 20% in March and 53-59% in April 2020, with an attenuation to about 40% at the end of 2021 (see Figure 1). Telehealth claims from these providers also showed a slight rise at the end of 2020 into the beginning of 2021. In contrast, general practitioners (i.e., pediatricians and those in general medicine or family practice) saw a much lower rise in telehealth claims at the beginning of the pandemic and a rapid fall to almost prepandemic levels after the April 2020 peak. These categories quickly attenuated to less than 10% of claims by provider type by June 2020 and less than 5% by the end of 2021. Still, overall telehealth claims as a proportion of all health care claims across all provider types were several orders of magnitude larger than prepandemic levels, with the largest, most persistent gains among behavioral health providers.

Figure 1.

Percentage of claims for services provided by telehealth, January 2020 to November 2021.

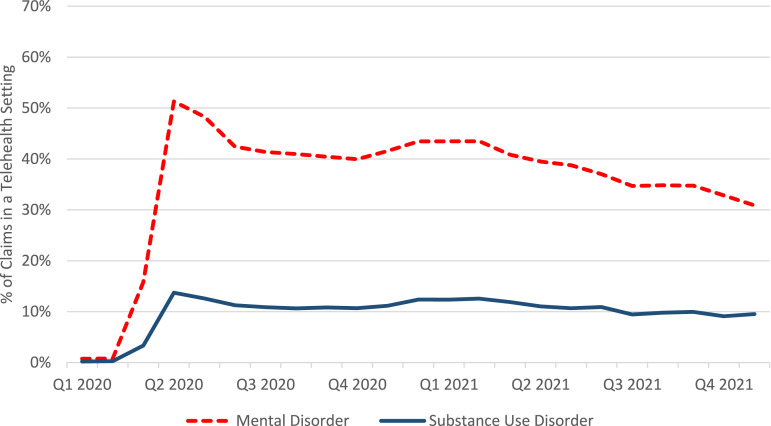

Looking specifically at mental health and SUD telehealth claims, we observed similar patterns to those identified in the analysis by provider type. As shown in Figure 2, the proportion of behavioral health claims that were telehealth was much higher by April 2020 than in the immediate prior months. In January–February 2020, all telehealth claims for these diagnoses represented a very small proportion of overall behavioral health claims. However, by April 2020, telehealth claims for mental health diagnoses accounted for more than 51% of all mental health claims. Since that time, the proportion of telehealth claims for mental health diagnoses has generally fallen, with a slight rise at the end of 2020 through the beginning of 2021, to roughly 30% of all mental health diagnosis claims. Claims for SUD diagnoses also saw a rapid rise in the first months of the pandemic in the United States, from less than 1% in February 2020 to almost 14% in April. As with mental health diagnoses, there was a drop in the share of telehealth claims for SUD diagnoses through the end of 2021 to about 10%, although that proportion seems to have plateaued.

Figure 2.

Percentage of claims for services provided by telehealth for mental and substance use disorders, January 2020 to November 2021.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced a major systemic change in the delivery of behavioral health care in the United States.3,13,14 This analysis demonstrates that telehealth services continued to be attractive to those covered by commercial insurance and Medicare Supplemental Insurance well into 2021, irrespective of whether COVID-19 transmission was in an acute surge. Furthermore, these data suggest that individuals are continuing to use telehealth, despite the widespread return to in-person activities in health care settings, workplaces, and other public spaces.

This persistence in the use of telehealth for behavioral health conditions indicates that at this point, use of telehealth is likely not simply about safety concerns but also convenience, comfort, and costs. Pre-COVID-19 concerns about acceptability of this modality of health care delivery appear to be somewhat allayed.15,16 Previous barriers related to the comfort of patients or providers with mental health care delivery through telehealth in particular may have been overcome during this pandemic-initiated system change.1,14 The ability of telehealth services for mental health conditions to fit flexibly and easily into busy lives may have an impact on staying power. Decreased transportation costs for patients and reduced infrastructure costs for providers who do not need to pay for office space may also be factors. Telehealth also has the potential to facilitate care more easily to those who previously may have been reluctant to attend in-person care due to stigma, mental health symptoms such as social anxiety, or other issues.2

However, the findings do suggest somewhat different patterns for adoption of telehealth for SUD-related care compared with telehealth adoption for mental health care. SUD-related telehealth constituted a lower share of behavioral health telemedicine visits throughout the observation period. At the same time, the line seemingly remains flat, whereas the proportion of claims for mental health services continues to drop slowly. These differences suggest that although there may be some continued attenuation of telehealth visits for mental health, the current rate of decline in SUD telehealth visits may have plateaued. A better understanding of patient and provider comfort with telehealth for SUDs is warranted, especially given some indication that SUD group treatment is less easily facilitated by telehealth.17 Privacy concerns related to telehealth treatment may also be a significant concern for those with SUD.18

Key questions remain about the extent to which quality behavioral health care can be effectively delivered via telehealth. Evidence supports that the quality of care for mental health conditions via telehealth is comparable to care provided in person,17,19 but there is mixed evidence for both uptake and effectiveness of SUD treatment via this modality.1,20 It is important to consider how the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE)-related policy flexibilities affected trends in the use of telehealth for initiation of treatment and counseling for opioid use disorder (OUD). In particular, questions remain about the relationship between the continuation or expansion of these PHE flexibilities, telehealth service use trends, and effective treatment for individuals with OUD.21

The findings from this analysis make a compelling argument that flexibilities in the workplace should be matched by flexibilities in the delivery of health care via telehealth, although the potential for subsequently creating new barriers to treatment should be carefully considered. On one hand, as workplaces continue to support hybrid working environments,22 including a broader geographic range of behavioral health providers in employer-based insurance plans via telehealth may be an important strategy to expand employees’ access to behavioral health services, especially given current constraints in the behavioral health provider workforce.23 To effectively leverage opportunities to expand access presented by this shift to telehealth, and to support robust coverage for employees, employers should consider including telehealth in their benefit packages. However, disparities in access to broadband internet likely need to be considered in rural communities.24,25 Similarly, understanding the differences between video and telephonic delivery of care is also important, as patterns of engagement vary across these 2 formats by demographic groups.25,26 In some cases, telehealth services have also led to a shift to self-pay among behavioral health clinicians,3,15 which could ultimately restrict access.

Our study prompts several considerations for the field. First, this descriptive trend analysis does not provide any information about the quality of the telehealth care provided. We also do not know from this analysis how much patient preferences, such as the potential for decreased stigma, or provider preferences, such as reductions in cost for office space, are driving the shift to telehealth. In addition, the analysis does not consider the adequacy of telehealth in filling pandemic-related gaps in behavioral health care, nor does it address whether there are differences in acceptability of telehealth treatment for initiation vs continuation of treatment. Finally, although the extent of the difference in trends is large from prepandemic to the end of the observation period for this analysis, further research should test the significance of these changes over time and assess the impact of these system changes on behavioral health outcomes.

Despite being in the early phases of research on its effectiveness across behavioral health diagnostic categories, telehealth seems to resonate with employees. Including telehealth in employee benefit packages may be an important strategy that employers can use to bolster their network of behavioral health providers and support employee health. As the evidence base continues to expand, hybrid approaches to behavioral health treatment that include both in-person and telehealth treatment modalities across episodes of care may be a possible outcome of this system change. Employers may consider coverage of behavioral health treatment for both video and telephonic approaches as well as reimbursement rates that are equivalent across all modes of delivery.27 Self-insured companies may also consider examining their own data to assess differential uptake of telehealth across specific demographic groups to ensure equitable access to treatment using this modality.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the contributions of Rachel Henke for consultation, Mary Beth Schaefer for editing, and Amanda Mummert for data access and coordination.

Footnotes

Disclaimers: Certain data used in this study were supplied by International Business Machines Corporation as part of one or more IBM MarketScan Research Databases. Any analysis, interpretation, or conclusion based on these data is solely that of the authors and not International Business Machines Corporation. The opinions expressed by the authors are their own and this material should not be interpreted as representing the official viewpoint of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health or the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Friedman AB, Gervasi S, Song H, et al. Telemedicine catches on: changes in the utilization of telemedicine services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28(1):e1-e6. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2022.88771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo J, Rae M, Amin K, Cox C, Panchal N, Miller B. Telehealth has played an outsized role meeting mental health needs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2022. (accessed April 28, 2022).https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/telehealth-has-played-an-outsized-role-meeting-mental-health-needs-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, Rost J. Telehealth: A Quarter-Trillion-Dollar Post-Covid-19 Reality? McKinnsey and Company. 2021. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality

- 4.Weigel G, Ramaswamy A, Sobel L, Salganicoff A, Cubanski J, Freed M. Opportunities and Barriers for Telemedicine in the U.S. During the COVID-19 Emergency and beyond. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2020. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/opportunities-and-barriers-for-telemedicine-in-the-u-s-during-the-covid-19-emergency-and-beyond/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, Niu J, Yin X, Xie J, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:91-98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049-1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory V, Steinberg J. Why Are Workers Staying Out of the U.S. Labor Force? The Regional Economist. 2022. https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/2022/feb/why-workers-staying-out-us-labor-force?utm_source=Federal+Reserve+Bank+of+St.+Louis+Publications&utm_campaign=28a5e88956-REUpdate&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_c572dedae2-28a5e88956-64044172 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galanti T, Guidetti G, Mazzei E, Zappalà S, Toscano F. Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: the impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement and stress. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(7):e426-e432. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao Y, Becerik-Gerber B, Lucas G, Roll SC. Impacts of working from home during COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental well-being of office workstation users. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(3):181-190. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barone Gibbs B, Kline CE, Huber KA, Paley JL, Perera S. Covid-19 shelter-at-home and work, lifestyle and well-being in desk workers. Occup Med. 2021;71(2):86-94. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqab011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abramson A. Burnout and Stress Are Everywhere. American Psychological Association. 2022. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/01/special-burnout-stress [Google Scholar]

- 12.WPS [Computer Software] . World Programming Software. 2022. https://www.worldprogramming.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner Lee N, Karsten J, Roberts J. Removing Regulatory Barriers to Telehealth before and after COVID-19. Brookings. 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/removing-regulatory-barriers-to-telehealth-before-and-after-covid-19

- 14.Zhu D, Paige SR, Slone H, et al. Exploring telemental health practice before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J Telemed Telecare. 2021. doi: 10.1177/1357633X211025943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Kyle MA, Blendon RJ, Findling MG, Benson JM. Telehealth use and satisfaction among US households: results of a national survey. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:237437352110527. doi: 10.1177/23743735211052737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen MLT, Garcia F, Juarez J, et al. Satisfaction can co-exist with hesitation: qualitative analysis of acceptability of telemedicine among multi-lingual patients in a safety-net healthcare system during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):195. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07547-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mark TL, Treiman K, Padwa H, Henretty K, Tzeng J, Gilbert M. Addiction treatment and telehealth: review of efficacy and provider insights during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(5):484-491. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison S. The struggle to make health apps truly private Vox. 2021. https://www.vox.com/recode/22570076/health-apps-privacy-opioid-addiction-app-report

- 19.Bulkes NZ, Davis K, Kay B, Riemann BC. Comparing efficacy of telehealth to in-person mental health care in intensive-treatment-seeking adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;145:347-352. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oesterle TS, Kolla B, Risma CJ, et al. Substance use disorders and telehealth in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(12):2709-2718. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livingston NA, Ameral V, Banducci AN, Weisberg RB. Unprecedented need and recommendations for harnessing data to guide future policy and practice for opioid use disorder treatment following COVID-19. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;122:108-222. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker K, Horowitz J, Minkin R. COVID-19 Pandemic Continues to Reshape Work in America. Pew Research Center. 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2022/02/16/covid-19-pandemic-continues-to-reshape-work-in-america/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cantor J, McBain RK, Kofner A, Hanson R, Stein BD, Yu H. Telehealth adoption by mental health and substance use disorder treatment facilities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(4):411-417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zahnd WE, Bell N, Larson AE. Geographic, racial/ethnic, and socioeconomic inequities in broadband access. J Rural Health. 2021; 38(3): 519–526. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoong EC. Policy considerations to ensure telemedicine equity. Health Aff. 2022;41(5):643-646. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eberly LA, Kallan MJ, Julien HM, et al. Patient characteristics associated with telemedicine access for primary and specialty ambulatory care during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2031640. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gajarawala SN, Pelkowski JN. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J Nurse Pract. 2021;17(2):218-221. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]