Introduction

Although, they represent the lion’s share of the American workforce, few articles specifically address the mental health and wellbeing needs and related resources for small employers.1-4 In this paper we define small businesses and their share of the U.S. workforce. Next, we review the research on the increasing burden of behavioral health disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, we discuss the role of employee assistance programs (EAP) in small businesses to effectively respond to the kinds of worker health and workplace problems exacerbated by the pandemic.

Small employers can be defined in several ways. In the United States, having 1 to 50 employees qualifies a company for access to the federal health care benefits associated with the Affordable Care Act.5 In contrast, the Small Business Association (SBA) part of the federal government generally defines its audience as employers with less than 500 employees. However, to qualify as a small business for various government loans and other SBA programs involves a complex combination involving the number of employees (ranging from under 100 to over 1000), the industry, and the total annual revenue for the company.6

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) conducts an annual compensation survey of employers of all sizes, industries, and sectors to assess employee wages and other employer-sponsored benefits.7 When combined with other national data from the Census Bureau on the number of businesses and organizations at the county level based on size of the establishment,8 we can create a profile of American business by company size and sector. This profile, for the most recent year available from 2021, is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of Establishments and Number of Workers in the United States in Year 2021: By Company Size within Private and Public Sectors.

| Establishments | Workers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size of employer | Number | % | Number | % |

| Private sector - all businesses | ||||

| Very small (1-49) | 7,555,381 | 94.5% | 52,396,317 | 39.5% |

| Small (50-99) | 243,199 | 3.0% | 16,700,678 | 12.6% |

| Medium (100-499) | 176,338 | 2.2% | 33,575,795 | 25.3% |

| Large (500+) | 21,963 | .3% | 30,084,137 | 22.7% |

| Total | 7,996,881 | 100.0% | 132,756,927 | 100.0% |

| Public sector - state and local governments | ||||

| Very small (1-49) | 1804 | 54.9% | 15,876 | 1.1% |

| Small (50-99) | 146 | 4.4% | 10,959 | .8% |

| Medium (100-499) | 755 | 23.0% | 182,316 | 13.0% |

| Large (500+) | 592 | 18.0% | 1,197,271 | 85.1% |

| Total | 3287 | 100.0% | 1,406,422 | 100.0% |

This data indicates that the smallest size employers, those with less than 50 workers, constitute the vast majority of all establishments in the U.S., accounting for 94.5% of the total. These workplaces employ 52.4 million workers, which is almost 40% of the total workers in the private sector. The next size up of companies with between 50 and 99 workers is only 3% of the total employers in the private sector, but they employ another 16.7 million workers (about 1 every 8 workers). All of the establishments with less than 100 employees when combined as 1 group – defined as “small employers” for this paper – account for 97.5% of all establishments and also the majority of all of the workers in the private sector (based on both total count of over 69 million workers and 52% of total workers).

In the public sector in the U.S. (ie, local and state government employers; excluding federal government workers), the story is both similar and different. Although small employers (ie, under 100 workers) represent almost 60% of all establishments, these organizations employ only a small fraction of the total workers at the local and state government level (2.9% of the 1.2 million total count of employees). Thus, when both sectors are considered together, over 99% of all small employers are in the private sector, based on both number of total establishments (private = 7,798,580 vs public = 1950) and the number of total workers (private = 69,096,995 vs public = 26,835).

Workplace Mental Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context

Historically, about 1 in every 4 working adults in the United States meet clinical criteria for having a behavioral health condition.10,11 The consequences of leaving anxiety, depression, alcohol, drugs, and other common behavioral disorders unidentified and untreated9,12,13 have negative impacts in several areas relevant to employers.14 These problems include reducing the ability of employees to be at work (absenteeism) and to properly perform their work,15-18 increased health care treatment costs,19,20 and greater workplace safety risks that can contribute to employee accidents and disability.21-23

Many of these behavioral health conditions have become much more prevalent in the United States,24,25 and in other countries26 during the COVID-19 global pandemic. For example, results of the National Health Interview Survey and the U.S. Census Bureau27 showed that in the first half of 2019 (before the pandemic) about 1 in every 10 Americans reported symptoms of depression or anxiety, but that after the pandemic had taken hold in January of 2021 this rate increased almost 4-fold (from 11% to 41%). The pandemic has made worker mental health a topic of major concern among employers with greater emphasis on the role of employee assistance programs (EAP).28-32

Employee Assistance Programs

What are Employee Assistance Programs?

Employee assistance programs are an employer-sponsored benefit designed to help employees resolve acute but modifiable behavioral health and personal life issues. A unique goal of these programs is to understand the clinical and work impacts of these kinds of issues and how to provide counseling that can restore both better health and work performance. More specifically, the Employee Assistance Professionals Association (EAPA)33 defines EAP as:

“a worksite-based program designed to assist (1) work organizations in addressing productivity issues and (2) employee clients in identifying and resolving personal concerns, including, but not limited to, health, marital, family, financial, alcohol, drug, legal, emotional, stress, or other personal issues that may affect job performance.”

How is Brief Counseling Provided?

EAPs are staffed mostly by masters-level licensed social workers or mental health counselors.34 The clinical experience usually involves a comprehensive initial assessment of the issue or problem and the available support options (from the EAP, from employee benefits, or from the local community or online resources).35 Then problem-focused counseling is provided to individuals for usually between 3 to 6 sessions per case over a 1 to 2 month treatment period. Anything discussed with the counselor is confidential and is not shared with the employer sponsor of the EAP - within the professional limits of patient privacy laws that allow for rare exceptions for legally mandated disclosure of self-harm or harm to others. Most EAPs are available to use 24/7 by telephone. However, there is variation how fast a client can be connected with a counselor, depending on the level of clinical severity, the availability of counselors on staff at the EAP or network affiliate counselors who work on contract part-time for EAP vendors, and the client’s preference for using in-person, telephonic, online video, or text/email modalities to meet with their counselor.

Why is Employee Assistance Programs Counseling Used?

The reasons why employees using such counseling represent a wide range of behavioral health, personal life, and work-related issues. For example, the most recent industry report examined the mix of presenting issues for over 29,000 total cases contributed by 35 different EAPs globally during the years 2010 to 2021.36 This study found that mental health issues (such as anxiety or depression) accounted for 30% of the total cases. In contrast, alcohol misuse or other addiction issues represented less than 3% of the total cases. The other two-thirds of cases in this study were spread across categories of personal life and personal stress (29%), marital, family, or personal relationships (19%), or various kinds of occupational issues and work-related stress (19%).

Beyond these counselor care users are employees who use the EAPs for support with many kinds of personal life issues other than mental health. Most EAPs have staff and specialists who can address wellness and wellbeing resources (eg, stress, sleep, nutrition, exercise),37 work/life issues for child care, elder care, and family members,38 and personal legal or financial issues.39 Debt and money problems for families has increased in society40 and thus has become of the most common reasons for seeking support from EAPs in recent years

Who Uses Employee Assistance Programs?

The users of EAP counseling represent a complex mix of working adults of both genders and across all ages and industries.41 Most EAPs also cover the immediate family members of employees. Many people who use an EAP for counseling are in the normal (pre-clinical) range of behavioral health risks but who experience an acute stressor event of some kind and thus need immediate support and practical direction to return to their typical level of personal functioning and work performance. However, some employees with more severe clinical symptoms also use EAPs are usually referred out of the EAP for further treatment by other employee benefit providers or to relevant community or specialty support services (ie, 5% to 20% of all cases are referred to outpatient mental health, addiction treatment, psychiatric medications).42

How Many Employees Use Employee Assistance Programs counseling?

Historically, about 5 out every 100 employees with access to the EAP benefit use it for personal counseling in a year.42 But more recently since the pandemic this clinical use rate has doubled. A clinical case utilization rate was obtained from recent national survey of 96 EAPs – split between external vendors and internal programs (with similar findings for both types).36 The results found that an average of 7.6 people per every 100 covered employees used the EAP for counseling in year 2019 and this rose to 9.7 during the pandemic in 2021. Other results revealed the average number of sessions of counseling per case rose from 3.9 in 2019 to 5.3 sessions in 2021. Thus, both the number of total cases and the number of sessions of counseling used per case increased during the pandemic. These results represent national data across many EAP vendors and programs and the use rates were not detailed by size of the employer or by the market sector.

How do Employee Assistance Programs Support the Workplace?

In addition to supporting individual workers, most full-service EAPs also support the workplace and larger organizational issues. This side of the EAP business model involves providing consulting to managers and leaders,43 workplace crisis preparedness and incident response,44 organizational level behavioral health risk management services,45 and specialists for difficult workplace events (ie, harassment, bullying, sexual inappropriate behavior, customer conflicts, work team dysfunction).46 Moreover, full-service providers often seek to build strategic alliances with other employee benefits and family support services for a more proactive approach to finding at-risk employees. When EAPs are embraced within the organization by health promotion, wellness, safety, and company leadership, they can be more effectively integrated into other parts of the larger organization.47

What Types of Employee Assistance Programs are Available?

There are different types of EAPs based on who they serve and how they are purchased.48 EAPs vary based on if the services are provided by staff who work for the same company served the program (internal models), the services are provided by an external company (vendor models), or a hybrid model that has some combination of internal staff and external provider services. Most smaller size employers, due to having less funding available per employee than medium and larger size employers, tend to get their EAP services from 1 of 3 kinds of external EAP sellers: a specialty insurance company, a health plan, or an external full-service EAP vendor. Another option for small employers in some locations is to get EAP services from 1 of the hundreds of internal EAP programs that serve a particular hospital or health system that also sells their counseling and workplace support services to other employers in the same local area.

How do Small Businesses use Employee Assistance Programs?

Most smaller businesses rely on insurance brokers to select their provider of EAP services (along with other insurance needs). Many insurance carriers also sell very low-cost EAPs or even give away EAP services for free if other higher-revenue insurance products are purchased. Because of this broker-lead sales model, many small employers may be unwitting victims of these imposter EAPs.49,50 low cost and “Free EAPs” are rarely promoted and lack much (if any) interaction with the workplace and the managers and HR staff who can make referrals, the “Free EAPs” are under-utilized (only 1 to 2 counseling cases per every 100 covered employees51) and thus offer little real business value to the employer.

How Many U.S. Workers Have Access to an Employee Assistance Programs in 2021?

We know from annual government surveys how many workers have an EAP benefit and also some evidence of how many employers sponsor an EAP. The most recent Bureau of Labor Statistics national survey data from year 20217 – shown in Table 2 reveals that although most employers have an EAP benefit, it varies dramatically by market sector and company size.

Table 2.

Percentage and Number of Workers in the United States in Year 2021 for Small Employers (1-99 Workers): By Private and Public Sectors and Total.

| Private sector (all businesses) | Public sector (Local and State Governments) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size of employer | % Of workers with EAP benefit | Number of workers with EAP benefit | % Of workers with EAP benefit | Number of workers with EAP benefit | % Of workers with EAP benefit | Number of workers with EAP benefit |

| Very small (1-50) | 27% | 14,147,006 | 60% | 9526 | 32% | 21,853,748 |

| Small (50-99) | 46% | 7,689,764 | 68% | 7452 | ||

| Medium (100-499) | 66% | 22,160,025 | 69% | 125,798 | ||

| Large (500+) | 83% | 24,969,834 | 89% | 1,065,571 | ||

| Total | 51% | 67,706,033 | 78% | 1,097,009 | ||

| Public sector federal | ||||||

| 100% | 2,181,106 | 70,984,148 | ||||

This data indicates that in the private sector, the percentage of workers with an EAP benefit ranges from about 1 in every 4 workers at the smallest size employers (under 50 workers), to almost half of workers at companies with between 50 and 99 workers, to about two-thirds of workers at medium size companies and better than 8 in every 10 workers at large companies. Results for the public sector reveals the same increasing trend by size of employer but at higher overall rates. The percentage of public sector workers with an EAP benefit ranges from 60% of very small organizations, 68% of workers at companies with between 50 and 99 workers, 69% of workers at medium size organizations, and 89% of workers at large organizations.

In total, there are over 67 million workers in the private sector who have access to an EAP from the 51% of all companies that sponsor this benefit. There are also another 1.1 million workers in the public sector at the local and state level who have an EAP from the 79% of employers in this sector that sponsor the benefit. In addition, all 2.2 million civilian employees working for the federal government also have access to an EAP. In total, over 70.9 million workers in the U.S. have access to an EAP.

Considering just the small employers who have from 1 to 99 workers, about 1 in 3 employees (32%) at these companies have an EAP. This translates into about 21.9 million total employees working for small employers who have access to an EAP. Almost all of these employees are from small companies in the private sector with only 1% coming from the small size state and local government employers.

How Many U.S. Employers (Workplaces) Have an Employee Assistance Programs in 2021?

Employers in many countries around the world are also increasingly starting to sponsor EAPs, although at lower levels than in the U.S. (see review in52). A global survey conducted in 2016 identified 839 different external providers EAPs, with 70% of these vendors based in the U.S.53 Yet, an accurate count of the total number of EAPs in the U.S. is unknown as there is no centralized list of all of the vendors and internal/hybrid programs. Thus, for this paper, the BLS data for the total number of establishments and the percentage of workers in such establishments with access to an EAP benefit was analyzed together to yield an actuarial estimate the number of specific employer establishments with an EAP benefit. This was done for the year 2021 for both the private and public sectors.

Table 3 shows the results in the estimated number of total establishments or specific workplaces that have an EAP benefit, sorted by size of employer in the private and public sectors in year 2021. The number of small size employers with EAP is estimated to be over 2.1 million, with the vast majority being from the very small size employers with less than 50 workers. There are 111,971 small employers (50-99 workers) with an EAP. Which is about the same as the 116,904 medium size employers with EAP. The number of large size employers with EAP is far less at just 18,756. Combined, that is about 4.1 million different establishments in the U.S. Of this total, very small employers account for 89.2%, small employers 4.9%, medium size employers 5.1%, and large employers only .8%. It is important to note that most of the small size employers likely have the “Free EAP” type of benefit that is embedded in other insurance products, which are quite different in design and effectiveness than the other types of full-service EAPs that are purchased directly from health plans or external specialty vendors by most of the medium and large size employers. Some of the largest size organizations even have internal staff to run their employee assistance program.

Table 3.

Number of Establishments in U.S. in Year 2021 with an EAP: By Private and Public Sectors and Total.

| Size of Employer | Establishments with EAP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private sector (all businesses) | Public sector (local and state governments) | Total | Total as % | |

| Very small (1-50) | 2,039,953 | 1082 | 2,041,035 | 89.2 |

| Small (50-99) | 111,872 | 99 | 111,971 | 4.9 |

| Medium (100-499) | 116,383 | 521 | 116,904 | 5.1 |

| Large (500+) | 18,229 | 527 | 18,756 | 0.8 |

| Total | 2,286,437 | 2230 | 2,288,666 | |

Time Trends for Employee Assistance Programs in U.S. 1999 to 2021

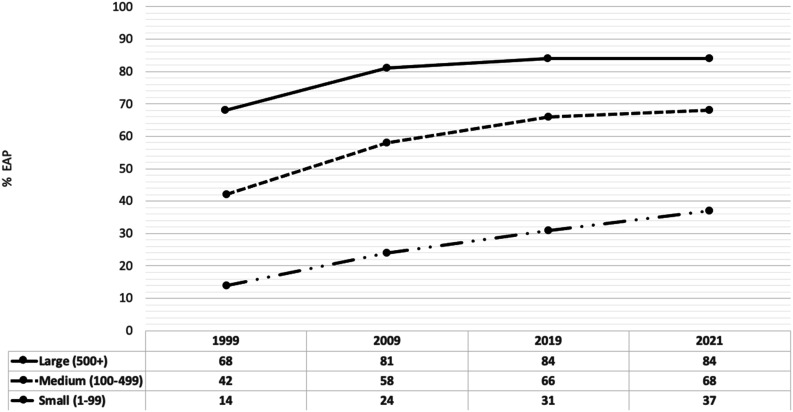

A final point of interest was understanding how access to EAPs has changed over time. Figure 1 uses data from the BLS but shows the percentage of workers in the private sector in the U.S. that had access to an EAP for small, medium, and large size employers in years 1999,54 2009,55 2019,56 and 2021.7 This data shows a trend for small size employers that after a big increase from 1999 to 2009 (change from 14% to 24%), the level of EAP access continued to increase over the past decade (2019 = 31%) with a jump up since the pandemic started (37% in 2021). For medium size employers there was also a trend of that a big increase from 1999 to 2009 (change from 42% to 58%), followed by a continued increase over the past decade with only a small rise since the pandemic (2009 = 66%; 2021 = 68%). The trend for large size employers also shows a large increase between 1999 to 2009 (change from 68% to 81%), which then remained stable over the past decade and into the pandemic period (2019 = 84%; 2021 = 84%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of workers with access to an EAP in the United States in the private sector: By Employer size in years 1999, 2009, 2019 and 2021 (source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, US government).

We know from Table 2 that there is a big difference by the size of employer involving access to EAPs in present day. As in year 2021 there were major differences by company size in the trends over time for EAP. The percentage of workers with access to an EAP at small employers was 2.64 times greater in 1999 than it was in 2021. This same 23-year period had less dramatic growth for adding EAP services among both the medium (1.62 x more) and the large size employers (1.23 x more), largely because of the relatively much higher starting rates these latter groups compared to small employers.

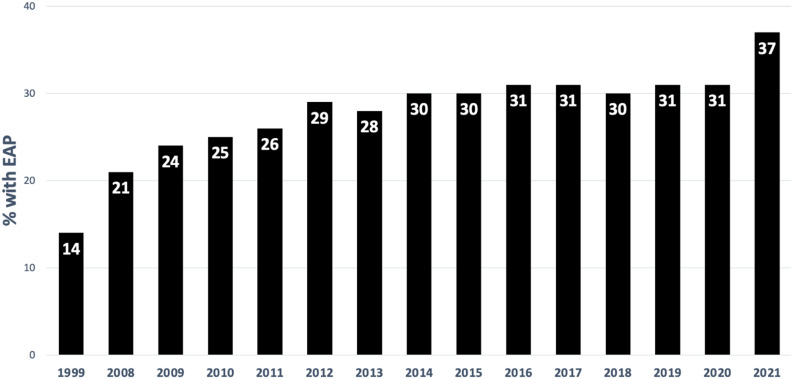

As the most rapid growth in the EAPs occurred with small employers, this was examined in more detail for each year of data available. Figure 2 uses national data from the BLS in year 199951 and then annually for each year starting with 2008 through 202157-67 just for the small size employers (1-99 workers) in the private sector. This line chart shows the large increase in the percentage of workers at small size employers in the private sector that have access to an EAP over time in the U.S. Of key importance is the jump up in the most recent year of data (from 31% to 37% of workers with access to EAP among these small employers) reflecting the COVID-19 pandemic period. Thus, more small employers had added an EAP in response to the increased need for mental health support associated with the pandemic.

Figure 2.

Percentage of workers with access to an EAP in the United States among small employers (1-99 workers) in the private sector: By year 1999 to 2021 (source: Bureau of labor statistics, US government).

What is the Business Case for Employee Assistance Programs?

Research indicates that counseling provided by EAPs is generally effective for most clients, regardless of whether it is provided in-person, over the telephone, or using internet video.36,42,68-70 The financial return on investment for EAPs is also compelling with cost savings in multiple areas, such as avoided health care claims, avoided lost work productivity and absenteeism, and possibly even avoided employee turnover, accidents, disability claims or other high cost events.71-74 A recent analysis estimated a $3.25 return for every $1.00 invested in the EAP for the typical small employer in the U.S.75 This ROI was based on only the outcomes of work productivity and absenteeism at $2034 in savings per counseling case, using a $25 per employee per year rate of the investment in the EAP, and a low level of use at only 5% of all covered employees using the EAP for counseling.

Conclusion

More research is needed to understand the specific mental health burden of small employers and current strategies for addressing this burden. Using EAPs to support employee mental health issues may be relevant for smaller size employers as they have fewer workers, managers, and leaders available to make the business successful, it is all the riskier for a behavioral health breakdown to occur for any 1 of the human parts of the work organization. The relatively low cost and high impact of an EAP may make sense for small employers if they can encourage employee utilization when needed – especially during the increased challenges of the global pandemic.

However, more research is needed to understand the specific mental health burden of small employers and current strategies for addressing these issues. One promising example is the recent initiative by Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO) in the U.S. to better understand the needs of small and mid-size businesses.77 In early 2022 they conducted a survey and plan to offer a small and mid-size business summit in the fall of 2022 to examine issues of employee mental and emotional health and well-being, how leaders and manager can support employee health and well-being, applying best practices within small and mid-size organizations, and controlling health risks and costs. Similar efforts by other employer groups supportive of small businesses are encouraged.

ORCID iD

Mark Attridge https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1852-2168

References

- 1.Merrill RM, Aldana SG, Pope JE, et al. Evaluation of a best-practice worksite wellness program in a small-employer setting using selected well-being indices. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(4):448-454. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182143ed0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rohlman DS, Campo S, Hall J, Robinson EL, Kelly KM. What could Total Worker Health® look like in small enterprises? Annals Work Exposures Health. 2018;62(S1):S34-S41. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxy008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leonard E, Terblanche L. An employee assistance programme for small and medium enterprises in Namibia: A needs assessment. Soc Work. 2020;56(1):1. http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/sw/v56n1/02.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bufquin D, Park JY, Back RM, de Souza Meira JV. de Souza Meira JV, Hight SK. Employee work status, mental health, substance use, and career turnover intentions: An examination of restaurant employees during COVID-19. Int J Hospit Manag. 2021;102764:93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . United States Government. How the Affordable Care Act Affects Small Business. 2022. https://www.healthcare.gov/small-businesses/learn-more/how-aca-affects-businesses/

- 6.Department of State, United States Government . What Is a Small Business? 2021. Washington, DC. https://www.state.gov/what-is-a-small-business/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bureau of Labor Statistics . US Department of Labor, United States Government. National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March. 2021. 2021. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2021/employee-benefits-in-the-united-states-march-2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Census Bureau . United States Government. County Business Patterns (CBP). 2022. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp.html

- 9.Congressional Research Service . United States Government. Federal Workforce Statistics Sources: OPM and OMB–. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43590.pdf

- 10.Karg RS, Bose J, Batts KR, et al. Past year mental disorders among adults in the United States, Results from the 2008–2012 Mental Health Surveillance Study. CBHSQ Data Review. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014. https://europepmc.org/article/MED/27748100 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) , Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs and Health. Office of the Surgeon General. 2016. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/surgeon-generals-report.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proudman D, Greenberg P, Nellesen D. The growing burden of major depressive disorders (MDD): Implications for researchers and policy makers. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(6):619-625. doi: 10.1007/s40273-021-01040-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mekonen T, Chan GC, Connor JP, Hides L, Leung J. Estimating the global treatment rates for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;295:1234-1442. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goetzel RZ, Roemer EC, Holingue C, et al. Mental health in the workplace: A call to action proceedings from the mental health in the workplace: Public health summit. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(4):322-330. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lerner D, Henke RM. What does research tell us about depression, job performance, and work productivity? J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(4):401-410. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31816bae50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henke RM, Carls GS, Short ME, et al. The relationship between health risks and health and productivity costs among employees at Pepsi Bottling Group. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(5):519-527. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181dce655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen D, Hines EW, Pazdernik V, Konecny LT, Breitenbach E. Four-year review of presenteeism data among employees of a large United States health care system: A retrospective prevalence study. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):1-10. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0321-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thørrisen MM, Bonsaksen T, Hashemi N, Kjeken I, Van Mechelen W, Aas RW. Association between alcohol consumption and impaired work performance (presenteeism): A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:9. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029184.e029184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Donnell MP, Schultz AB, Yes L. The portion of health care costs associated with lifestyle-related modifiable health risks based on a sample of 223, 461 employees in seven industries: The UM-HMRC Study. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(12):1284-1290. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goetzel RZ, Henke RM, Head MA, Benevent R, Rhee K. Ten modifiable health risk factors and employees’ medical costs-an update. Am J Health Promot. 2020;34(5):490-499. doi: 10.1177/0890117120917850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frey JJ, Osteen PJ, Berglund PA, Jinnett K, Ko J. Predicting the impact of chronic health conditions on workplace productivity and accidents: Results from two US Department of Energy national laboratories. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(4):436-444. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veltrup C, John U. Addictive disorders: Problems and interventions at the workplace. In: Bültmann U, Siegrist J, eds, 1. New York, NY: Springer; 2020:1-20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-75381-2_28-1.Handbook of Disability, Work and Health. Handbook Series in Occupational Health Sciences. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2021. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35319/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:817-818. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdalla SM, Ettman CK, Cohe GH, Galea S. Mental health consequences of COVID-19: A nationally representative cross-sectional study of pandemic-related stressors and anxiety disorders in the USA. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e044125. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santomauro DF, Herrera AM, Shadid J, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700-1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panchal N, Kamal R, Orgera K, et al. The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. White Paper. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021. https://pameladwilson.com/wp-content/uploads/4_5-2021-The-Implications-of-COVID-19-for-Mental-Health-and-Substance-Use-_-KFF-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfeffer J, Williams L. Mental Health in the Workplace: The Coming Revolution. McKinsey Quarterly. 2020. Dec. 8 www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/mental-health-in-the-workplace-the-coming-revolution# [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards R. The importance of reintroducing employee assistance programs during the pandemic. Forbes. 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbeshumanresourcescouncil/2020/07/24/the-importance-of-reintroducing-employee-assistance-programs-during-the-pandemic/?sh=7345f2591c98 [Google Scholar]

- 30.WorldatWork . The WorldatWork COVID-19 Employer Response Survey.USA, 2020. White Paper. Scottsdale, AZ. https://worldatwork.org/media/Survey/COVID-19_Employer_Response-April2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks CD, Ling J. “Are we doing enough”: An examination of the utilization of employee assistance programs to support the mental health needs of employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Insur Regul. 2020;39(8):1-34. https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/jir-za-39-08-el-mental-health-eaps.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Society for Human Resources Management . SHRM Foundation, Ostuka Pharmaceutical Co. Mental Health in America: A 2022 Workplace Report. White Paper. Washington, DC, USA. 2022. https://www.workplacementalhealth.shrm.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Mental-Health-in-America-A-2022-Workplace-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.Employee Assistance Professionals Association . Orientation to Employee Assistance Programs: For Mental Health Professionals in the U.S.A. McLean, VA, USA. 2015. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/15775 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobson JF, Pastoor J, Sharar D. Predicting practice outcomes among social work employee assistance counselors. Soc Work Ment Health. 2013;11(5):460-472. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2012.749827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shotlander J. An Introduction to Employee Assistance Programs: NetCE Course #76252. NetCE. Sacramento, CA, USA; 2019:1-36. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Attridge M. Workplace Outcome Suite (WOS) Annual Report 2021: EAP Counseling Use and Outcomes, COVID-19 Pandemic Impact, and Best Practices in Outcome Data Collection LifeWorks. White Paper. Toronto, ON: Canada; 2022. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/18701 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Attridge M. Integration Insights Column (5): EAP integration with worksite wellness programs. J Empl Assistance. 2016;46(1):6-7. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/7209 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobson JM, Attridge M. Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs): An allied profession for Work/Life. In: Sweet S, Casey J, eds Work and Family Encyclopedia. Chestnut Hill, : Sloan Work and Family Research Network; 2010. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/2603 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Attridge M. Employee Assistance Program Outcomes Similar for Counselor (Phone and In-person) and Legal/Finance Consultation Clients. Presented at the annual conference of the American Psychological Society. New Orleans, LA, USA; 2002. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/3855 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witteveen D, Velthorst E. Economic hardship and mental health complaints during COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(44):27277-27284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Attridge M. Workplace Outcome Suite (WOS) Annual Report 2020: Part 2: Profiles of Work Outcomes on 10 Context Factor of EAP Counseling Use. White Paper. Toronto, ON: Canada; 2020. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/1375 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Attridge M, Cahill T, Granberry S, Herlihy P. The national behavioral consortium industry profile of external EAP vendors. J Workplace Behav Health. 2013;28(4):251-324. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolski-Andreaco A, Tomlinson D. EAP Training for Managers: Shifting the Paradigm from Managing to Coaching. EASNA Research Notes. 2018;7(1):1-9. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/7468 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Attridge M, VandePol B. The business case for workplace critical incident response: A literature review and some employer examples. J Workplace Behav Health. 2010;25(2):132-145. doi: 10.1080/15555241003761001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Attridge M. Integration Insights Column (8): EAP Integration with behavioral risk management. J Empl Assistance. 2017;47(3):32-33. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/7398 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Attridge M. Integration Insights Column (10): Psychological health & safety in the workplace. J Empl Assistance. 2018;49(3):18-19. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/9842 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Attridge M. Integrating Employee Assistance Programs into Other Workplace Programs: The Organizational Health Map. Keynote address presented at the annual conference of the Employee Assistance Professionals Association. Chicago, IL, USA; 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/7292 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Attridge M, Amaral T, Bjornson T, et al. EAP services, programs and delivery channels. EASNA Research Notes. 2009;1(4):1-6. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/5097 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharar DA, Burke J. The perceived value of ‘Free’ versus fee-based employee assistance programs. WorldatWork J. 2009;8(4):21-31. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/4129 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandys J. The evolution of employee assistance programs in the United States: A 20-year retrospective from 26 EAP vendors. EASNA Research Notes. 2015;5(1):1-6. http:/hdl.handle.net/10713/4890 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Attridge M. Implications of pricing for EAP integration and ROI. J Empl Assistance. 2017;47(1):2627. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/7211 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Attridge M. A global perspective on promoting workplace mental health and the role of employee assistance programs. Am J Health Promot. 2019;34(4):622-627. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0890117119838101c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mollenhauer M. Top Industry. Chapter in Chestnut Global Partners Trends Report 2017. Bloomington, IL, USA: Chestnut Global Partners; 2017. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/6515 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in Private Industry in the United States, 1999 Supplemental Tables, 2000. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/sp/ebtb0001.pdf

- 55.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March2009. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2009/ebbl0044.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2019. 2019. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2019/employee-benefits-in-the-united-states-march-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . Table 38. Quality of Life Benefits: Access, Private Industry Workers, National Compensation Survey, March 2008. 2008. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2008/ownership/private/table24a.pdf

- 58.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . Table 38. Quality of Life Benefits: Access, Private Industry Workers, National Compensation Survey, March 2010. 2010. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2010/ownership/private/table24a.pdf

- 59.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . Table 40. Quality of Life Benefits: Access, Private Industry Workers, National Compensation Survey. Survey, March 2011. 2011. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2011/ownership/private/table24a.pdf

- 60.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . Table 40. Quality of Life Benefits: Access, Private Industry Workers, National Compensation Survey. Survey, March 2012. 2012. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2012/ownership/private/table24a.pdf

- 61.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . Table 40. Quality of Life Benefits: Access, Private Industry Workers, National Compensation Survey. Survey, March 2013. 2013. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2013/ownership/private/table24a.pdf

- 62.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . Table 40. Quality of Life Benefits: Access, Private Industry Workers, National Compensation Survey. Survey, March 2014. 2014. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2014/ownership/private/table40a.pdf

- 63.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . Table 40. Quality of Life Benefits: Access, Private Industry Workers, National Compensation Survey, March 2015. 2015. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2015/ownership/private/table24a.pdf

- 64.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . Table 40. Quality of Life Benefits: Access, Private Industry Workers. National Compensation Survey, March 2016. 2016. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2016/ownership/private/table40a.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . Table 40. Quality of Life Benefits: Access, Private Industry Workers, National Compensation Survey, March 2017. 2017. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2017/ownership/private/table40a.pdf

- 66.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . Table 40. Quality of Life Benefits: Access, Private Industry Workers, National Compensation Survey, March 2018. 2018. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2018/ownership/private/table40a.pdf

- 67.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Government . National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2020. 2020. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2020/employee-benefits-in-the-united-states-march-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 68.Joseph B, Walker A, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M. Evaluating the effectiveness of employee assistance programmes: A systematic review. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2018;27(1):1-15. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2017.1374245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Attridge M. Do EAPs Work? Presented at the Spring Think Tank meeting of the Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO). San Antonio, TX, USA; 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/8869 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Csiernik R, Cavell M, Csiernik B. EAP evaluation 2010–2019: What do we now know? J Workplace Behav Health. 2021;36(2):105-124. doi: 10.1080/15555240.2021.1902336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Attridge M. 20 years of EAP cost-benefit research: Taking the pareto path to ROI. Part 2 of 3. J Empl Assistance. 2010;40(3):12-15. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/14935 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Attridge M. 20 years of EAP cost-benefit research: Taking the productivity path to ROI. Part 3 of 3. J Empl Assistance. 2010;40(4):8-11. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/14903 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Attridge M. The Business Value of Employee Assistance: A Review of the Art and Science of ROI. Keynote address presented at the annual conference of the Employee Assistance Professionals Association. Phoenix, AZ, USA; 2013. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/8380 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Attridge M, Dickens SP. Health and work outcomes of brief counseling from an EAP in Vermont: Follow-up survey results, client satisfaction, and estimated cost savings. Sage Open. 2022;12(1):215824402210872. doi: 10.1177/21582440221087278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Attridge M. Workplace Outcome Suite (WOS) Annual Report 2020: Part 1-Decade of Data on EAP Counseling Reveals Prominence of PresenteeismMorneau Shepell. White Paper. Toronto, ON: Canada; 2020. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/1375 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Health Enhancement Research Organization . Small and midsize business well-being at HERO 2020. https://hero-health.org/blog/hwb-for-smb/ [Google Scholar]