Abstract

Some Escherichia coli strains with impaired cell division form branched cells at high frequencies during certain growth conditions. Here, we show that neither FtsI nor FtsZ activity is required for the development of branches. Buds did not form at specific positions along the cell surface during high-branching conditions. Antibiotics affecting cell wall synthesis had a positive effect on branch formation in the case of ampicillin, cephalexin, and penicillin G, whereas mecillinam and d-cycloserine had no substantial effect. Altering the cell morphology by nutritional shifts showed that changes in morphology preceded branching, indicating that the cell’s physiological state rather than specific medium components induced branching. Finally, there was no increased probability for bud formation in the daughters of a cell with a bud or branch, showing that bud formation is a random event. We suggest that branch formation is caused by abnormalities in cell wall elongation rather than by aberrant cell division events.

Some strains of Escherichia coli form branched cells during certain growth conditions. The mechanism(s) for branch formation is not known, although an understanding of this phenomenon might help in understanding how the rod shape of E. coli cells is maintained. Branching occurs at high frequencies in one type of the so-called intR1 strains (6), in which chromosome replication starts from an integrated R1 plasmid (8). Branched cells have also been observed in min mutants (6) during blockage of chromosome replication by antibiotics (48) and in thymine-requiring strains starved for thymine (48, 54, 55). The frequency of branching has also been shown to be dependent on the type of medium (6).

Branching strains often display a disturbed nucleoid distribution (6, 8, 26, 36) and produce filaments and/or minicells (4, 10, 22). One report has indicated that branches develop from cell poles formed by asymmetric cell division events (53). In this report, we have investigated whether branches result from aberrant cell division events or, alternatively, whether branches are formed as outgrowths from small asymmetries arising at low frequencies during cell wall elongation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and shift of medium.

The E. coli strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The intR1 strain EC::71CC is a derivative of EC1005 in which part of oriC has been deleted and replaced by the R1 replicon, which controls replication in this strain (8). Strain EC1005ptac-ftsZ was obtained by transduction of EC1005 with a P1 lysate of VIP205 (19) and selection for kanamycin resistance on Luria agar (LA) plates containing 20 μM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Strains EC1005ftsZ84 and MG1655ftsZ84 were obtained by transduction of EC1005 and MG1655, respectively, with a P1 lysate of VIP183 and selection for tetracycline resistance on LA plates. VIP183 was obtained from Miguel Vicente and carries the ftsZ84(Ts) allele (31) and leu::Tn10. Strains were grown in Luria broth medium containing 0.2% glucose (LBglu) or in M9 minimal medium (43) supplemented with 0.2% glucose (M9glu) or 0.2% sodium acetate and 0.5% Casamino Acids (Difco) (M9caace). For EC1005 and for strains derived from EC1005, M9glu was supplemented with methionine (50 μg/ml). Drugs were added to the following concentrations: ampicillin, 20 μg/ml; cephalexin, 10 μg/ml; kanamycin, 20 μg/ml (M9caace) or 50 μg/ml (LA plates, for selection of P1 transductants); and tetracycline, 10 μg/ml. The cells were incubated in shaker baths as follows: EC1005, MG1655, EC1005ptac-ftsZ, and EC1005ΔminB at 37°C; EC::71CC and MG::71CC at 34°C; and EC1005ftsZ84 and MG1655ftsZ84 at 30°C (permissive temperature) or 42°C (nonpermissive temperature).

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains used in this study

| Strain | Parent | Relevant features | Source or reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EC1005 | metB1 nalA relA1 spoT1 λr F− | 20 | |

| EC1005ΔminB | EC1005 | EC1005 ΔminB Kmr | 5 |

| EC::71CCb | EC1005 | EC1005 ΔoriC::pOU71 Apr | 8 |

| EC1005ptac-ftsZ | EC1005 | EC1005 ftsA::kan T4 lacIqptac::ftsZa | This study; 19 |

| EC1005ftsZ84 | EC1005 | EC1005 ftsZ84(Ts) leu::Tn10 | This study |

| MG1655 | λr F− | 7, 27 | |

| MG1655ftsZ84 | MG1655 | MG1655 ftsZ84(Ts) leu::Tn10 | This study |

| MG::71CCb | MG1655 | MG1655 ΔoriC::pOU71 Apr | 6 |

The insert between ftsA and ftsZ was introduced into EC1005 with a P1 lysate of VIP205 (17) and was selected for by kanamycin.

The initiation frequency of chromosome replication in EC::71CC and MG::71CC is regulated by temperature, such that growth at 35°C or higher results in overreplication (see Bernander et al. [8]).

For the shift of growth medium, 1 ml of culture in exponential growth phase (optical density of <0.3, measured at 550 nm) was centrifuged at about 4,000 × g for 7 min, the supernatant was removed by aspiration, and the cells were resuspended in 10 ml of prewarmed growth medium.

Microscopic studies.

To measure cell length and the frequency of branched cells in exponentially growing cultures, cells were first fixed in 70% ethanol. Cells were then resuspended in 0.9% NaCl, and 10 μl was put on microscope slides covered with thin 1% agar layers. For visualization of nucleoids, 0.5 μg of DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) per ml was included in the agar. To monitor changes in the frequency of branched cells after the shift of growth medium, 10-μl samples were put directly onto microscope slides with agar layers, and the cells were studied immediately. The microculture technique (5) was used to monitor the growth of individual cells and to study microcolonies: 5 to 20 μl of cell culture was added to microscope slides covered with thin 1% agar layers containing the same growth medium. The slides were incubated at 37°C or on a thermostatically controlled heating plate connected to the microscope, where the temperature was monitored by using a small probe inserted directly into the agar.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed essentially as described by Hiraga et al. (22), except that we used 10-well multitest slides from ICN Biomedicals, Inc. FtsZ-specific antisera was a gift from Joe Lutkenhaus, and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody was purchased from Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.

Cells were analyzed with a Nikon Optiphot-2 microscope, and the images were digitized by using a cooled charge-coupled device camera (Meridian) connected to a computerized image analysis system (soft- and hardware were from Bergström Instrument AB). The digitized images were printed by using a Sony UP-860/CE videoprinter or were processed in Adobe Photoshop and submitted in digital form.

RESULTS

Bud formation in the wild-type and intR1 and minB mutant strains.

We first investigated whether branches develop at specific positions along the cell surface, e.g., related to putative division sites (midcell) or cell poles. E. coli strains giving low (wild-type), moderate (minB), and high (intR1) branching frequencies were grown exponentially in LBglu and/or M9caace (Table 2 and Materials and Methods). The microculture technique was used to monitor the growth of individual cells (5).

TABLE 2.

Effects on branch formation of cephalexin or growth at the nonpermissive temperature of strains carrying the ftsZ84(Ts) allele

| Strain | Medium, temp (°C) | Cephalexin (10 μg/ml) | % Frequency of branched cellsa | Avg cell length (μm)b | No. of branches/ mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC1005 | LBglu, 37 | − | 0.1 | 4.3 | 0.2 |

| + | 0.2 | 15 | 0.2 | ||

| M9caace, 37 | − | 3.3 | 3.1 | 11 | |

| + | 23 | 13 | 18 | ||

| MG1655 | LBglu, 37 | − | 0.4 | 4.6 | 0.9 |

| + | 1.3 | 16 | 0.9 | ||

| M9caace, 37 | − | 2.8 | 3.0 | 9.4 | |

| + | 26 | 10 | 25 | ||

| EC::71CC | M9caace, 34 | − | 20 | 6.0 | 43 |

| + | 53 | 29 | 47 | ||

| EC1005ftsZ84 | M9caace, 30 | − | 1.3 (1.5)c | 2.5 (2.2) | 5.0 (6.9) |

| + | 15 (6.2) | 11 (9.8) | 14 (6.3) | ||

| M9caace, 42 | − | 4.7 (0.99) | 9.6 (3.0) | 4.9 (3.3) | |

| + | 9.0 (5.3) | 13 (9.5) | 6.8 (5.5) | ||

| MG1655ftsZ84 | M9caace, 30 | − | <0.1 (0.2) | 2.3 (2.1) | <0.5 (1.0) |

| + | 4.3 (3.0) | 10 (8.4) | 4.2 (3.5) | ||

| M9caace, 42 | − | 1.1 (0.1) | 8.7 (3.1) | 2 (0.32) | |

| + | 1.8 (1.4) | 11 (8.0) | 1 (1.7) |

Values were obtained by counting more than 2,000 cells from each culture grown in LBglu and more than 500 cells for cultures grown in M9caace.

The average cell lengths were obtained by measuring 50 cells of EC1005 and MG1655 grown in M9caace and 100 cells from each of the other cultures.

Numbers in parentheses are values obtained with the corresponding wild-type under the same conditions. Note that the effect of cephalexin on branching for EC1005 at 30 and 42°C was much smaller than what was typically observed at 37°C.

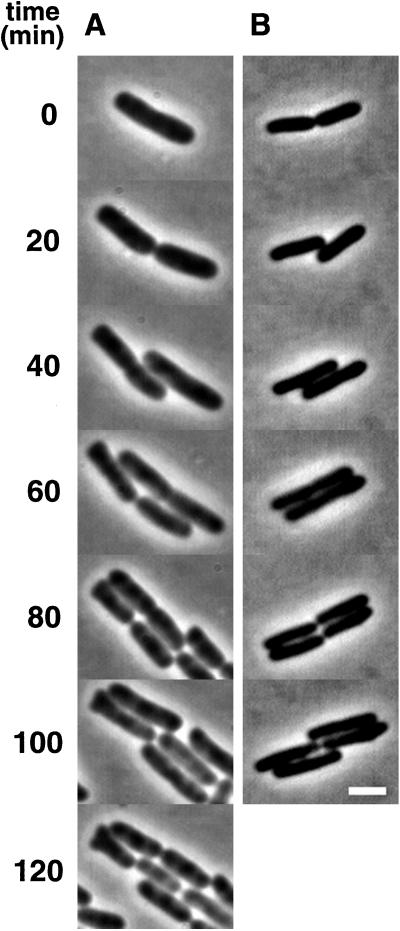

In LBglu, the frequency of branched wild-type (EC1005) cells was <1% (Table 2). Four bud formation events were observed by monitoring the growth of microcolonies, and all of these buds were formed at cell poles (Fig. 1A). The cells that formed buds were of wild-type length and continued to grow normally after bud formation. Interestingly, all four poles at which bud formation was observed were present at the start of the microculture experiments, and the buds were formed between one and three cell generations later, i.e., branching occurred at the old cell poles. Similarly, buds were located at or close to cell poles in fixed cells of the intR1 strains EC::71CC (21 of 23) and MG::71CC (25 of 29).

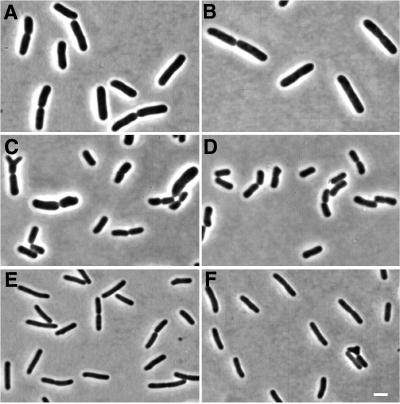

FIG. 1.

Formation of branched cells in EC1005. Cells were grown exponentially in LBglu medium (A) or M9caace (B) at 37°C, whereupon 10 μl of the culture was transferred to a flat agar surface containing the same growth medium. Bar, 2 μm.

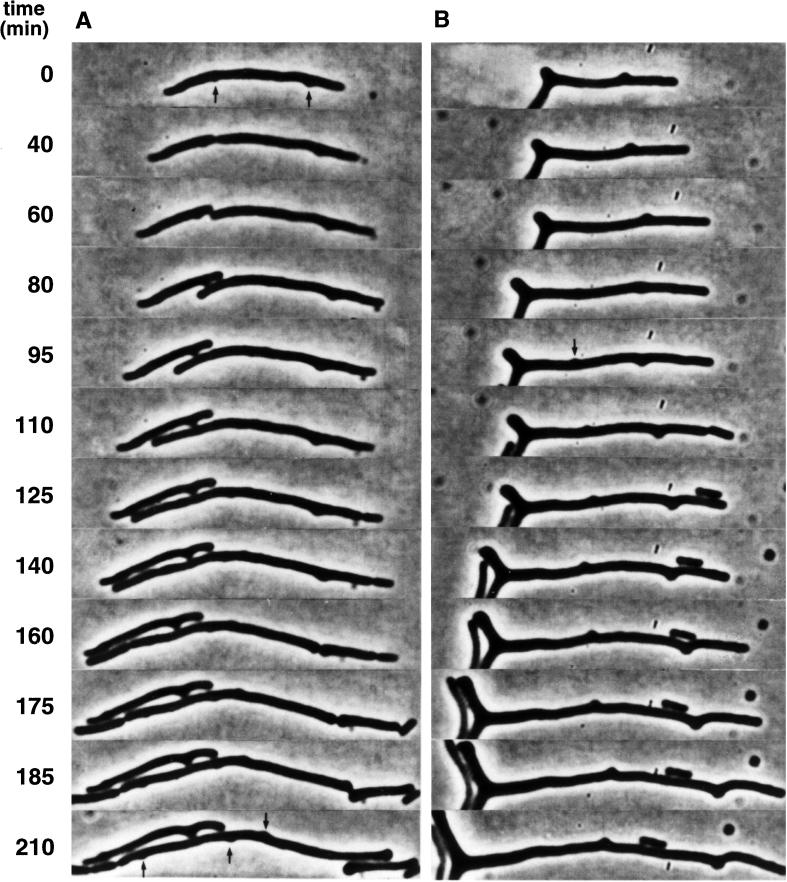

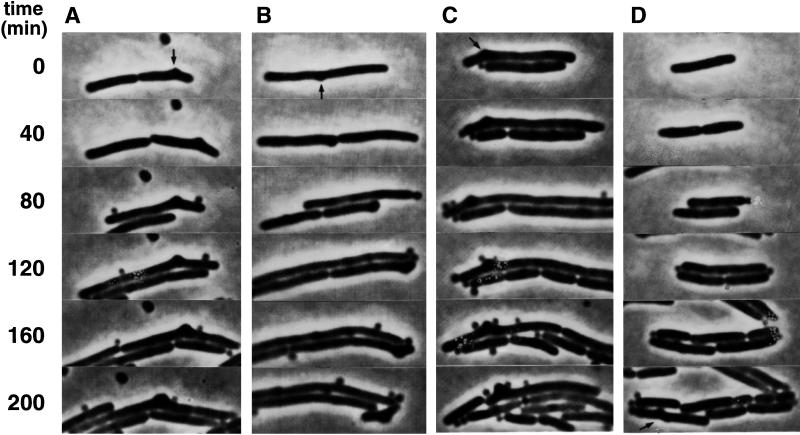

In M9caace, the frequency of branching was higher than in LBglu (Table 2), and three polar and seven nonpolar branch formation events were observed in the wild type. The branched cells were of wild-type length, and the polar buds appeared from cell poles present at the start of the microculture experiments after about one cell generation. Six of the seven nonpolar buds were formed between the cell pole and the center of the cell (Fig. 1B), whereas one bud formed at midcell. In the intR1 strain (EC::71CC), most buds were localized along filaments (Fig. 2A, 0 min, arrows) and grew slowly, sometimes resulting in a kink of the cell (Fig. 2A, 210 min, left daughter cell; and Fig. 2B, 210 min). Cell division sometimes occurred close to buds, resulting in dumbbell-shaped cell poles (Fig. 2A, 160 min, right daughter cell), and new buds developed at various positions along the cell surface (Fig. 2A, 210 min, arrows; and Fig. 2B, 95 min, arrow). Some newly formed cells did not grow, indicating that chromosome-less cells were formed (Fig. 2B, 100 min). Strikingly, buds appeared to rotate around the cell cylinder (cf. Fig. 2B, 60 and 95 min). The slow development and growth of the buds (Fig. 3A, arrow; Fig. 3C; and Fig. 3D, 200 min, arrow), as well as the formation of dumbbell-shaped cells (Fig. 3B, 40 min, left daughter cell), was also observed in a minB mutant.

FIG. 2.

Growth and division pattern of branched cells in the intR1 strain EC::71CC. Cells were grown exponentially in M9caace medium at 34°C, whereupon 5 to 10 μl of the culture was transferred to a flat agar surface containing the same medium, and the growth of two cells (A and B) was monitored. Small buds on the cell surface are indicated (arrows).

FIG. 3.

Growth and division pattern of branched cells in the EC1005ΔminB strain. Cells were grown exponentially and treated as described in the legend of Fig. 2, except that the temperature was 37°C. Four different cells (A to D) are shown. Small buds on the cell surface are indicated (arrows).

In conclusion, the positions at which buds appeared were medium dependent. In LBglu, branching preferentially initiated from the old cell poles, whereas in M9caace, a majority of branches appeared along the length axis of the cells. The buds developed and grew slowly, and cell division sometimes occurred close to buds. However, no clear correlation between the positioning of nonpolar buds and the putative cell division sites (at midcell) was observed.

Bud formation does not require FtsI.

Septum synthesis in E. coli cells requires the action of the ftsI gene product, FtsI, also known as penicillin-binding protein 3 (PBP3) (11, 45, 47). FtsI is a cytoplasmic membrane protein which is specifically involved in peptidoglycan synthesis of the septum. Cephalexin inhibits FtsI activity, which results in elongated cells and eventual cell death (44, 46). If FtsI activity is required throughout the early parts of bud formation, the addition of cephalexin should stop the appearance of new buds and the frequency of branched cells should remain constant or decrease. To test this idea, exponentially growing cultures were divided into two parts, and cephalexin was added to one part to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. After a fourfold increase in optical density (untreated culture), the cells were fixed in 70% ethanol and the frequency of branched cells was measured (Table 2).

For EC1005 (wild-type) grown in LBglu, the frequency of branched cells was low both in cultures grown with and without cephalexin. In a screen for branched cells in a cephalexin-treated culture, all six buds were located at or close to the poles of the filamented cells. For MG1655 the frequency of branched cells increased 3.4- and 4-fold (two experiments) after the addition of cephalexin (Table 2). Again, most (18 of 21) of the buds were located at or close to cell poles. The number of buds per millimeter (cell length) was similar before and after the addition of cephalexin, suggesting that new buds appeared during filamentation of the cells.

In M9caace, the frequency of branched cells in the wild-type strains increased from 2 to 3% to 20 to 30% after the addition of cephalexin (Table 2). In a microculture experiment, a majority (13 of 14) of the buds developed at nonpolar positions (in contrast to that in LBglu cells [see above]). In the intR1 strain (EC::71CC), the frequency of branched cells increased from 20 to 53% after the addition of cephalexin (measured after two mass doublings for the untreated culture). A significant proportion of the branched cells had more than one branch, and the average number of branches per cell was ca. 1.4. For the wild-type strains, the number of branches per millimeter of cell length had increased after two mass doublings in the presence of cephalexin, whereas the total increase in cell length remained fairly constant (Table 2).

The results suggest that FtsI activity is not required for branch formation. Instead, blockage of FtsI by cephalexin increased the number of buds and branches per millimeter of cell length. This observation argues against the idea that the cell division process is involved in branch formation.

Bud formation is not dependent on FtsZ.

One of the earliest steps in cell division in E. coli is the assembly of the FtsZ protein to a ring around the cytoplasm at the future division site (9, 12, 30, 35). FtsZ is essential for cell division, and FtsZ ring formation is a prerequisite for the localization of many other cell division proteins to the cell division site, including FtsI (1, 3, 51). Severe over- or underexpression of FtsZ in E. coli inhibits cell division (14, 52).

To test whether there is any correlation between FtsZ and bud formation, FtsZ was visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy, and the localization of FtsZ structures was compared to the localization of buds in strains EC1005 and MG1655. When grown exponentially in M9caace, ca. 40% of the cells in populations of EC1005 and 45% of the cells in populations of MG1655 had a distinct, central fluorescent band or, in cells with a deep constriction at midcell, a dot. A few cells showed diffuse fluorescence at one or both poles. Buds did not specifically colocalize with FtsZ structures. As with the cell poles, however, buds sometimes contained diffuse fluorescence, and it is possible that FtsZ rings or structures were assembled and depolymerized before the bud became visible. We next added cephalexin to increase the number of branches per unit cell length (above) and analyzed the distribution of FtsZ rings by immunofluorescence microscopy. No structures other than a central fluorescent band or, in some cells taken at a later time point, one band at each cell quarter position were detected. Thus, we did not find any colocalization of FtsZ structures and buds. It should be noted, however, that any FtsZ structures involved in bud formation might be transient and therefore difficult to detect.

To further investigate any correlation between FtsZ and bud formation, we tested the capability of bud formation in cells with low and high levels of FtsZ and in strains producing a temperature-sensitive FtsZ protein after shifting the cells to the nonpermissive temperature.

FtsZ levels were altered by using a construct in which chromosomal ftsZ gene expression is under the control of the tac promoter (19). This construct also contains four copies of a strong transcriptional terminator, uncoupling ftsZ from its natural promoters, the lacIq gene and a kanamycin resistance gene. The construct was introduced into strain EC1005, resulting in EC1005ptac-ftsZ, and IPTG was used to set the level of ftsZ gene expression. Growth of EC1005ptac-ftsZ in M9caace at 0 or 100 μM IPTG yielded populations with broad cell length distributions, whereas at 5 μM IPTG, the cell size distribution was similar to that of EC1005. No effect of IPTG on the cell size distribution of EC1005 was evident. As observed by immunofluorescence microscopy, the amount of FtsZ in EC1005ptac-ftsZ increased with the concentration of IPTG. At 0 μM IPTG, most cells had one or no centrally localized FtsZ band, and the fluorescence signals from these bands were significantly weaker than for those in cells grown at 5 μM IPTG. At 100 μM IPTG, most cells had a broad band of FtsZ at their center with a marked increase in fluorescence intensity, and many cells had additional long regions with an equally high fluorescence intensity. At 5 μM IPTG, the frequency of branched cells was ca. 0.5%. At 0 and 100 μM IPTG, the frequency was ca. 2 to 3%. Thus, there was no proportionality between FtsZ levels and the frequency of branched cells.

Strains producing a temperature-sensitive FtsZ protein were made by introducing the ftsZ84(Ts) allele (31) into EC1005 and MG1655, yielding EC1005ftsZ84 and MG1655ftsZ84, respectively. The strains were grown continuously in M9caace at 30°C (permissive temperature) and then shifted to 42°C (nonpermissive temperature). Cells were fixed after two doublings in optical density, and the frequency of branched cells and the number of branches per millimeter of cell length were measured (Table 2). The results clearly showed that branches were formed in both strains at both the permissive and nonpermissive temperatures. Buds were also formed at the nonpermissive temperature in the presence of cephalexin. Shifting EC1005 and MG1655 from 30 to 42°C indicated that the increased temperature had a slight negative effect on branch formation, both in the absence and in the presence of cephalexin (Table 2).

In conclusion, inactivation or alteration of the levels of FtsZ did not inhibit branch formation. Together with the finding that branch formation continues after inactivation of FtsI by cephalexin, these results strongly suggest that the cell division process is not required for branch formation.

Buds can form in cells with both normal and disturbed nucleoid distribution.

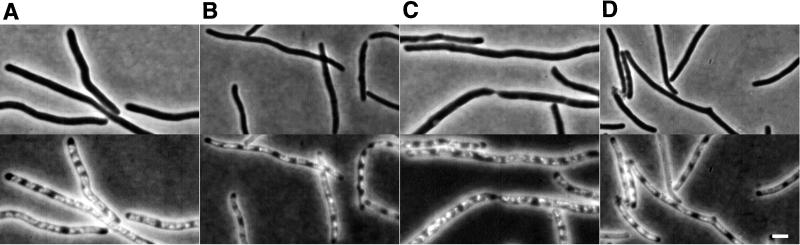

Branched cells have been reported to form in cells affected in chromosome replication (48, 54, 55), and we have previously shown that strains with a disturbed nucleoid distribution have an elevated frequency of branched cells (6). Mulder and Woldringh (37) showed that in a dnaX(Ts) mutant grown at the restrictive temperature, the peptidoglycan synthesis rate is slower at the central part of the filamentous cells containing the nucleoid than at the nucleoid-free cell ends, suggesting a negative effect of the nucleoid on peptidoglycan synthesis rate. Thus, an irregular nucleoid distribution may lead to asymmetric peptidoglycan synthesis, thereby causing the formation of buds on the cell surface. As stated above, the frequency of branched cells was significantly higher in M9caace than in LBglu (Table 2), and we therefore investigated whether the nucleoid distribution was different in cells grown in M9caace compared to those grown in LBglu. In the wild-type strains, growth in both media in the presence of cephalexin resulted in an essentially regular distribution of nucleoids (Fig. 4). Buds in these cells were found in regions occupied by nucleoids, as well as in nucleoid-free regions. In strain EC::71CC, in which the branching frequency was higher, the nucleoid distribution was similarly disturbed in both LBglu and M9caace. Thus, a disturbed nucleoid distribution appeared not to be required for bud formation.

FIG. 4.

Nucleoid distribution in EC1005 and MG1655 grown in the presence of cephalexin (10 μg/ml) for about two mass doublings. Panels: A, EC1005 grown in LBglu; B, EC1005 grown in M9caace; C, MG1655 grown in LBglu; D, MG1655 grown in M9caace. All cultures were grown at 37°C, and cephalexin was added to exponentially growing cultures. Bar, 2 μm.

Branch formation correlates with cell physiology rather than with medium components.

The frequency of branched cells varies with the growth medium. This might correlate with the different cell morphologies obtained in the different media (Fig. 5) and/or with specific components in the medium. In an attempt to distinguish between these possibilities, we shifted cells (EC1005 and MG1655) from M9glu (low branching) to M9caace (high branching) and monitored the changes in cell morphology and the frequency of branched cells (Fig. 6A and C). An increase in branch formation before any change in morphology would suggest a direct effect of some medium component on branching. A change in morphology before an increase in branch formation, on the other hand, would suggest that the medium effect on branching comes by an overall change in cell morphology. EC1005 had a slower growth rate during the first 3 h after the shift from M9glu to M9caace (doubling time of 80 min) than when grown continuously in M9caace, whereas MG1655 reached its new growth rate in about 1 h. (The doubling times during balanced growth for EC1005 and MG1655 in M9caace were ca. 40 and 60 min, respectively, and in M9glu were ca. 40 and 50 min, respectively.) The frequency of branched cells did not start to increase until the cells had become microscopically indistinguishable from cells growing continuously in M9caace (one to three mass doublings [indicated by arrows in Fig. 6]). In one experiment, the frequencies of branched cells in M9glu were 4 and 3% for EC1005 and MG1655, respectively. (These high frequencies in M9glu were only observed once and could not be reproduced. It should also be noted that the branching frequencies obtained here with EC1005 grown continuously in M9caace were higher than we have reported previously [6]. We have no explanation for these differences.) When these cultures were shifted to M9caace, there was a drastic initial decrease in the frequency of branched cells. This decrease was followed by an increase, which again came well after the observable changes in cell morphology were complete.

FIG. 5.

Cell morphology of EC1005 and MG1655 in different growth media. Panels: A, C, and E, EC1005; B, D, and F, MG1655; A and B, LBglu; C and D, M9glu; E and F, M9caace. Bar, 2 μm.

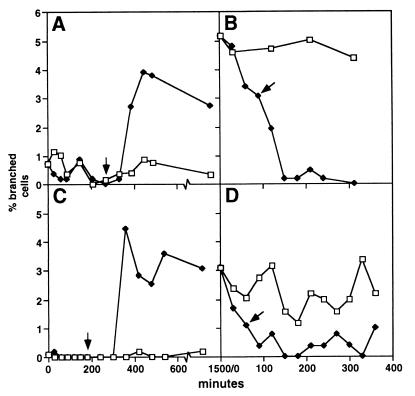

FIG. 6.

Changes in branching frequency after a shift of growth medium. Exponentially growing cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in the same growth medium or in another growth medium. The cultures were diluted repeatedly to maintain exponential growth. The frequency of cells with buds and branches was estimated by putting cells directly onto an agar surface, and at least 500 cells were counted. Arrows indicate the first time sample in which cells shifted to the new growth medium had become microscopically indistinguishable from cells grown continuously in the new growth medium. Panels: A and C, EC1005 and MG1655, respectively, shifted from M9glu to M9caace; B and D, EC1005 and MG1655, respectively, shifted from M9caace to LBglu.

During a shift from M9caace to M9glu, there was a long period (several hours) of metabolic adaptation with no or very little mass growth. After a shift from M9caace to LBglu, the cells became larger (Fig. 5A and B), and a drastic, initial decrease in the frequency of branched cells was observed (Fig. 6B and D). This decrease was consistent with low or no branch-forming activity, i.e., it does not imply the disappearance of already existing buds and branches. A shift from LBglu to M9caace was followed by a long period with very little or no mass growth, as observed with the shift from M9caace to M9glu.

In conclusion, changes in cell morphology preceded changes in branching frequencies in the shifts from M9glu to M9caace, suggesting that branching correlates with cell physiology rather than with specific medium components. The drastic initial decrease in branching after shifts from M9caace to LBglu could be due to branch formation being sensitive to changes in cell physiology.

Effect on branching of antibiotics affecting cell wall synthesis.

Our results so far do not suggest any involvement of the cell division process or a disturbed nucleoid distribution in branch formation. An alternative mechanism for branch formation would be that branches form from small asymmetries in the cell wall that arise during elongation. We therefore investigated whether branch formation was affected by antibiotics affecting cell wall synthesis in different ways. Antibiotics were added at a series of different concentrations to cultures in balanced growth, and cells were fixed after two doublings in optical density (as measured for the untreated culture). The frequencies of branched cells and branches per millimeter of cell length in the absence or presence of antibiotics are summarized in Table 3. Values are given for the antibiotic concentrations yielding the largest observed effect on branching or, in the case of no observed effect, for the highest concentration at which no substantial cell lysis or rounded cells were observed.

TABLE 3.

Effects of different antibiotics on branch formation

| Straina | Antibiotic | Antibiotic concn (μg/ml) | % Frequency of branched cellsb | Avg cell length (μm)c | No. of branches/ mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC1005 | Ampicillin | 2 | 14 (3.1)d | 9.6 (2.9) | 15 (10) |

| MG1655 | 2 | 3.9 (0.7) | 8.9 (2.7) | 4.4 (2.6) | |

| EC1005 | Penicillin G | 10 | 15 (3.1) | 9.2 (2.9) | 16 (10) |

| MG1655 | 10 | 5.2 (0.7) | 9.3 (2.7) | 5.7 (2.6) | |

| EC1005 | Mecillinam | 0.01 | 2.1 (2.7) | 2.5 (2.7) | 8.5 (10) |

| EC1005 | d-Cycloserine | 6 | 1.8 (1.4) | 2.5 (2.5) | 7.2 (5.8) |

| MG1655 | 6 | 1 (1.2) | 2.7 (2.6) | 3.7 (4.7) |

Strains were grown in M9caace at 37°C.

Values were obtained by counting at least 500 cells.

The average cell lengths were obtained by measuring at least 100 cells.

Numbers in parentheses refer to the untreated culture in each experiment.

Like cephalexin, ampicillin and penicillin G have a high affinity for PBP3 (45). As opposed to cephalexin, however, ampicillin and penicillin G also bind to PBP2 with relatively high affinities (45). PBP2 is required for cell wall elongation (44). The addition of ampicillin or penicillin G at 2 or 10 μg/ml, respectively, yielded filaments with an increased number of branches per millimeter similar to that obtained with cephalexin (Tables 2 and 3), thus showing that any effect on PBP2 by ampicillin and penicillin G had no extra effect on branch formation. Also, the addition of mecillinam, an antibiotic highly specific for PBP2 (44), did not have any substantial effect on branching at concentrations not causing substantial rounding of the cells (Table 3) (at higher concentrations, buds were difficult to distinguish due to the round shape of the cells).

To disturb cell wall synthesis at an earlier step than the transpeptidation reactions carried out by PBP2 and PBP3 (23, 24), we used the antibiotic d-cycloserine that inhibits formation of d-alanine dipeptides (51), required for cell wall elongation. d-Alanine dipeptides are added to tripeptide side chains in peptidoglycan precursors to form pentapeptide side chains (17, 25). Pentapeptides are then required for the subsequent transpeptidation reactions. We could find no major effect of d-cycloserine on branch formation.

In conclusion, cephalexin, ampicillin, and penicillin G had a positive effect on branching, whereas mecillinam and d-cycloserine had no substantial effect. Cephalexin, ampicillin, and penicillin G all bind several penicillin-binding proteins (45), and the effect on branching could be due to the binding to one or more of these proteins.

Branch formation is a random event.

The frequency of branched cells was qualitatively the same in most experiments performed with the same strain and the same growth conditions. In the shift experiments described above, cells resuspended in the same medium after centrifugation maintained approximately the same frequency of branched cells for several generations. Cells shifted from M9glu to M9caace showed an increase in bud-forming activity after a certain time period after the shift. These observations suggest that bud formation does not take place primarily in a subpopulation with an elevated bud-forming activity, which would lead to variations in the frequency of branched cells during the course of an experiment. It is still conceivable, however, that once a bud has formed on a cell, there is an increased probability that its daughter cells will also form a bud. If this increase in probability is sufficiently small and/or if branched cells have a sufficiently decreased growth rate or viability, this kind of “inheritance” would not give rise to large subpopulations with an elevated bud-forming activity.

In the time-lapse experiments we found one example of a cell with a bud that gave rise to a daughter cell that also formed a bud. To complement this observation with a larger number of cells, cells were grown as in the time-lapse experiments for 3.5 h, and the total number of cells and the number of cells with a bud were then counted for each of at least 100 microcolonies (Table 4). In the two samples from the same culture of EC1005 grown in M9caace, the total frequencies of branched cells on the agar slide were ca. 2.4 and 1.9%. The average numbers of cells per microcolony were ca. 10.5 and 11.1. Only one microcolony in one of the samples was found to contain two cells with a bud, and no microcolony was found that contained three or more cells with a bud. These results do not indicate any increased probability for daughter cells to a cell with a bud to form a new bud.

TABLE 4.

Number of branched cells in microcolonies of EC1005 grown on M9caace

| Sample | No. of microcolonies containinga:

|

Avg no. of cells/microcolony | Total % frequency of branched cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 BC | 1 BC | 2 BC | |||

| 1 | 82 | 25 | 1 | 10.5 | 2.4 |

| 2 | 97 | 26 | 0 | 11.1 | 1.9 |

BC, branched cell(s).

Cultures of EC1005 and MG1655 grown in M9caace in the presence of cephalexin for about two mass doublings contained more than 20% branched cells. However, only ca. 1% of the cells had two buds (cells with more than two buds were very rare). This is significantly less than what would be expected if buds formed independently of each other in the same cell. Thus, there appears to be some physiological constraint in the cephalexin-treated cells on the formation of a second bud. Since only one microcolony contained two branched cells (Table 4), it is also possible that, in a culture not treated with cephalexin, this constraint exists for the daughter cells of a cell that has formed a bud.

DISCUSSION

Previous reports have indicated that an aberrant cell division process could lead to branch formation. We have previously reported an increased branching frequency in the filamenting intR1 strains EC::71CC and MG::71CC and in strains with the minB operon deleted (6). Branched cells have also been observed after depletion of the cell division protein FtsL (21) and FtsZ spirals have been shown to cause spiral invaginations (2), suggesting a potential of FtsZ to alter cell wall morphology. In the present study, we found no correlation between the cell division process and branch formation. Branch formation was not confined to putative cell division sites, and no FtsZ structures were found to colocalize preferentially to buds. In addition, separate or simultaneous inactivation of the cell division proteins FtsI and FtsZ did not inhibit branch formation.

A correlation between a disturbed chromosome replication or nucleoid morphology is indicated in previous reports (6, 48, 54, 55). Also, nucleoids have been shown to affect the peptidoglycan synthesis rate (37) and might therefore contribute to putative asymmetries in the cell wall that cause branch formation. Here, branch formation was shown to occur in normally replicating wild-type strains with a normal nucleoid distribution.

An alternative mechanism to account for branch formation would be that branches form from small asymmetries in the cell wall. In support of this idea, interference with cell wall synthesis by growing cells in the presence of cephalexin, ampicillin, or penicillin G had a positive effect on branching. This effect cannot (solely) be due to filamentation, since cephalexin had a positive effect on branching in filaments induced by growth at the nonpermissive temperature of strains carrying the ftsZ84(Ts) allele.

Many bacterial species are able to change the direction of growth, resulting in branched cells or hypha-like networks of filamented cells, but the mechanisms that lead to the formation of new cell poles and branching are unknown. In Rhizobium meliloti, inhibition of cell division by addition of cephalexin, nalidixic acid, or mitomycin C caused branching at the cell poles, whereas overexpression of either of the bacterium’s two FtsZ proteins caused branching at midcell (28). Also, constitutive expression of FtsZ in Caulobacter crescentus caused the formation of a bifurcated stalk (41). However, neither ftsZ nor ftsQ is required for branch formation in Streptomyces coelicolor (33, 34), and it is possible that the extended C terminus of FtsZ in R. meliloti FtsZ1 and C. crescentus is causing the differences (32, 40).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joe Lutkenhaus for providing FtsZ-specific antiserum and Miguel Vicente for providing strains VIP183 and VIP205.

This work was supported by the Swedish Natural Science Research Council and the Swedish Cancer Society. A grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation enabled us to purchase the microscope and the image analysis equipment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addinall S G, Lutkenhaus J. FtsA is localized to the septum in an FtsZ-dependent manner. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7167–7172. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7167-7172.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addinall S G, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ-spirals and -arcs determine the shape of the invaginating septa in some mutants of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:231–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Addinall S G, Cao C, Lutkenhaus J. FtsN, a late recruit to the septum in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:303–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4641833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adler H I, Fischer W D, Cohen A, Hardigree A A. Miniature Escherichia coli cells deficient in DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;57:321–326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.57.2.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Åkerlund T, Bernander R, Nordström K. Cell division in Escherichia coli minB mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2073–2083. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Åkerlund T, Bernander R, Nordström K. Branched Escherichia coli cells. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:849–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachmann B J. Derivations and genotypes of some mutant derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12. In: Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 1190–1219. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernander R, Merryweather A, Nordström K. Overinitiation of replication of the Escherichia coli chromosome from an integrated runaway-replicon derivative of plasmid R1. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:674–683. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.674-683.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1991;354:161–164. doi: 10.1038/354161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. Isolation and characterization of ftsZ alleles that affect septal morphology. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5414–5423. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5414-5423.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botta G A, Park J T. Evidence for involvement of penicillin-binding protein 3 in murein synthesis during septation but not during cell elongation. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:333–340. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.333-340.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bramhill D, Thompson C M. GTP-dependent polymerization of Escherichia coli FtsZ protein to form tubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5813–5817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook W R, MacAlister T J, Rothfield L I. Compartmentalization of the periplasmic space at division sites in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1430–1438. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1430-1438.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai K, Lutkenhaus J. ftsZ is an essential cell division gene in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3500–3506. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3500-3506.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Boer P A J, Crossley R E, Rothfield L I. A division inhibitor and a topological specificity factor coded for by the minicell locus determine proper placement of the division septum in E. coli. Cell. 1989;56:641–649. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Boer P A J, Crossley R E, Rothfield L I. Roles of MinC and MinD in the site-specific septation block mediated by the MinCDE system of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:63–70. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.63-70.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncan K, van Heijenoort J, Walsh C T. Purification and characterization of the d-alanyl-d-alanine-adding enzyme from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2379–2386. doi: 10.1021/bi00461a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erickson H P. FtsZ, a prokaryotic homolog of tubulin? Cell. 1995;80:367–370. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrido T, Sánches M, Palacios P, Aldea M, Vicente M. Transcription of ftsZ oscillates during the cell cycle of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1993;12:3957–3965. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grinsted J, Saunders J R, Ingram L C, Sykes R B, Richmond M H. Properties of an R factor which originated in Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1822. J Bacteriol. 1972;110:529–537. doi: 10.1128/jb.110.2.529-537.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzman L-M, Barondess J, Beckwith J. FtsL, an essential cytoplasmic protein involved in cell division in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7716–7728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiraga S, Ichinose C, Niki H, Yamazoe M. Cell cycle-dependent duplication and bidirectional migration of SeqA-associated DNA-protein complexes in E. coli. Mol Cell. 1998;1:381–387. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishino F, Park W, Tomioka S, Tamaki S, Takase I, Kunugita K, Matsuzawa H, Asoh S, Ohta T, Spratt B G, Matsuhashi M. Peptidoglycan synthetic activities in membranes of Escherichia coli caused by overproduction of penicillin-binding protein 2 and RodA protein. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:7024–7031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishino F, Matsuhashi M. Peptidoglycan synthetic enzyme activities of highly purified penicillin-binding protein 3 in Escherichia coli: a septum-forming reaction sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;101:905–911. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91835-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito E, Strominger L. Enzymatic synthesis of the peptide in a uridine nucleotide from Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:PC5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaffé A, D’Ari R, Hiraga S. Minicell-forming mutants of Escherichia coli: production of minicells and anucleate rods. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3094–3101. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3094-3101.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen K F. The Escherichia coli K-12 “wild types” W3110 and MG1655 have an rph frameshift mutation that leads to pyrimidine starvation due to low pyrE expression levels. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3401–3407. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3401-3407.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latch N J, Margolin W. Generation of buds, swellings, and branches instead of filaments after blocking the cell cycle of Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2373–2381. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2373-2381.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Löwe J, Amos L. Crystal structure of the bacterial cell division protein FtsZ. Nature. 1998;391:203–206. doi: 10.1038/34472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring in bacterial cytokinesis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:403–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lutkenhaus J F, Wolf-Watz H, Donachie W D. Organization of genes in the ftsA-envA region of the Escherichia coli genetic map and identification of a new fts locus (ftsZ) J Bacteriol. 1980;142:615–620. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.2.615-620.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margolin W, Corbo J C, Long S R. Cloning and characterization of a Rhizobium meliloti homolog of the Escherichia coli cell division gene ftsZ. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5822–5830. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.18.5822-5830.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCormick J R, Su E P, Driks A, Losick R. Growth and viability of Streptomyces coelicolor mutant for the cell division gene ftsZ. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:243–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCormick J R, Losick R. Cell division gene ftsQ is required for efficient sporulation but not growth and viability in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5295–5301. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5295-5301.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukherjee A, Lutkenhaus J. Guanine nucleotide-dependent assembly of FtsZ into filaments. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2754–2758. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2754-2758.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mulder E, El’Bouhali M, Pas E, Woldringh C L. The Escherichia coli minB mutation resembles gyrB in defective nucleoid segregation and decreased negative supercoiling of plasmids. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:87–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00280372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulder E, Woldringh C L. Autoradiographic analysis of diaminopimelic acid incorporation in filamentous cells of Escherichia coli: repression of peptidoglycan synthesis around the nucleoid. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4751–4756. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4751-4756.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedro M, Quintela J C, Höltje J-V, Schwarz H. Murein segregation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2823–2834. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2823-2834.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pichoff S, Vollrath B, Touriol C, Bouché J-P. Deletion analysis of gene minE which encodes the topological specificity factor of cell division in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:321–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18020321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quardokus E, Din N, Brun Y V. Cell cycle regulation and cell type-specific localization of the FtsZ division initiation protein in Caulobacter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6314–6319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raskin D M, de Boer P A J. The MinE ring: an FtsZ-independent cell structure required for selection of the correct division site in E. coli. Cell. 1997;91:685–694. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothfield L I, Zhao C-R. How do bacteria decide where to divide? Cell. 1996;84:183–186. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80971-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spratt B G. Distinct penicillin binding proteins involved in the division, elongation, and shape of Escherichia coli K12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:2999–3003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.8.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spratt B G. Properties of the penicillin-binding proteins of Escherichia coli K12. Eur J Biochem. 1977;72:341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spratt B G. Penicillin-binding proteins and the future of β-lactam antibiotics. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:1247–1260. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-5-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spratt B G, Pardee A B. Penicillin binding proteins and cell shape in E. coli. Nature. 1975;254:516–517. doi: 10.1038/254516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suit J C, Barbee T, Jetton S. Morphological changes in Escherichia coli strain C produced by treatments affecting deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis. J Gen Microbiol. 1967;49:165–173. doi: 10.1099/00221287-49-1-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teather R M, Collins J F, Donachie W D. Quantal behavior of a diffusible factor that initiates septum formation at potential division sites in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1974;118:407–413. doi: 10.1128/jb.118.2.407-413.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang E, Walsh C. Suicide substrates for the alanine racemase of Escherichia coli B. Biochemistry. 1978;17:1313–1321. doi: 10.1021/bi00600a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, Khattar M K, Donachie W D, Lutkenhaus J. FtsI and FtsW are localized to the septum in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2810–2816. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2810-2816.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ward J E, Jr, Lutkenhaus J. Overproduction of FtsZ induces minicell formation in E. coli. Cell. 1985;42:941–949. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woldringh C L, Zaritsky A, Grover N B. Nucleoid partitioning and the division plane in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6030–6038. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6030-6038.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaritsky A. Branching of fast-growing Escherichia coli 15T− at low thymine concentrations. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1977;2:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zaritsky A, Woldringh C L. Chromosome replication rate and cell shape in Escherichia coli: lack of coupling. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:581–587. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.2.581-587.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao C-R, de Boer P A J, Rothfield L I. Proper placement of the Escherichia coli division site requires two functions that are associated with different domains of the MinE protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4313–4317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]