Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that causes infections in eye, urinary tract, burn, and immunocompromised patients. We have cloned and characterized a serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) kinase and its cognate phosphoprotein phosphatase. By using oligonucleotides from the conserved regions of Ser/Thr kinases of mycobacteria, an 800-bp probe was used to screen P. aeruginosa PAO1 genomic library. A 20-kb cosmid clone was isolated, from which a 4.5-kb DNA with two open reading frames (ORFs) were subcloned. ORF1 was shown to encode Ser/Thr phosphatase (Stp1), which belongs to the PP2C family of phosphatases. Overlapping with the stp1 ORF, an ORF encoding Hank’s type Ser/Thr kinase was identified. Both ORFs were cloned in pGEX-4T1 and expressed in Escherichia coli. The overexpressed proteins were purified by glutathione-Sepharose 4B affinity chromatography and were biochemically characterized. The Stk1 kinase is 39 kDa and undergoes autophosphorylation and can phosphorylate eukaryotic histone H1. A site-directed Stk1 (K86A) mutant was shown to be incapable of autophosphorylation. A two-dimensional phosphoamino acid analysis of Stk1 revealed strong phosphorylation at a threonine residue and weak phosphorylation at a serine residue. The Stp1 phosphatase is 27 kDa and is an Mn2+-, but not a Ca2+- or a Mg2+-, dependent Ser/Thr phosphatase. Its activity is inhibited by EDTA and NaF, but not by okadaic acid, and is similar to that of PP2C phosphatase.

Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of many proteins is a well-known mechanism for the regulation of their cellular activities. Such protein kinases (and protein phosphate phosphatases) have been classified into a number of groups based primarily on the target amino acids that are phosphorylated (or dephosphorylated after phosphorylation), i.e., histidine kinases, tyrosine kinases, serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) kinases, etc. (7, 8, 15, 20, 26, 30). Even though early classifications indicated histidine kinases to be the predominant kinases in prokaryotes and tyrosine or Ser/Thr kinases to be the predominant kinases in eukaryotes, subsequent investigations demonstrated the presence of eukaryote-like kinases and phosphatases in prokaryotes as well (24, 31). Such eukaryote-like protein-serine/threonine/tyrosine kinases and phosphoprotein-serine/threonine/tyrosine phosphatases have been implicated in regulating bacterial growth, development, and virulence characteristics (24, 31).

The advent of genomics in recent years has provided interesting insights into the presence of multiple genes encoding tyrosine or Ser/Thr kinases and phosphatases in prokaryotes. For example, DNA sequences and in vitro kinase assays demonstrated the presence of at least seven eukaryote-like protein kinases in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, several of which were biochemically identified (7). A complete genome analysis showed the presence of 11 such genes in M. tuberculosis (4), although very little is known about their cellular functions. Another example is the presence of at least four putative Ser/Thr kinases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, one of which has been implicated in its virulence (29). It is interesting to note that both a protein-tyrosine phosphatase (YopH) and a Ser/Thr kinase (YpkA) have been shown in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis to be encoded by the virulence plasmid and to be secreted into the host cell by a type III secretion mechanism (5, 8, 9). While YopH modulates host function by dephosphorylation of p130cas and FAK and the disruption of peripheral focal complexes, the YpkA protein is targeted to the inner surface of the plasma membrane and causes morphological alterations (5, 8). However, no target protein of YpkA has yet been identified. Since P. aeruginosa uses a type III secretion mechanism similar to that of the Yersinia Yop system, delivering ExoS and other enzymes directly into the host cell (27, 28), it is possible that, like YpkA or YopH, the P. aeruginosa Ser/Thr kinase or phosphatase types of eukaryote-like proteins may also be targeted to the host cells by a type III mechanism. The detection of such secreted enzymes depends upon their presence in the eukaryotic cells, as determined by Western blotting, as well as the fusion of genes encoding enzymes such as adenylate cyclase to the kinase/phosphatase gene. This requires the availability of the genes and purified enzymes of the Ser/Thr kinase/phosphatase. As a first step to such detailed studies, we have cloned and sequenced a gene cluster encoding a Ser/Thr kinase and its cognate phosphoprotein phosphatase. We purified the gene products, and we describe here some of the characteristics of these proteins and demonstrate that these genes are a part of large operon and are cotranscribed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are given in Table 1. P. aeruginosa PAO and Escherichia coli were grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C. Kanamycin (40 μg/ml), ampicillin (100 μg/ml), or tetracycline (12 μg/ml) were used whenever required. The oligonucleotides, described in Table 1, were synthesized by Gibco-BRL Laboratories. Inhibitors were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or oligonucleotide | Genotype or sequence | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 λ-φ80 dlacZΔM15 F−ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm | Gibco-BRL |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | Novagen | |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | Wild type | 25 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLAFR1 | Vector cosmid, Tetr | |

| pGEM-T Easy | TA cloning vector | Promega |

| pKS+ | Bluescript, Ampr | Stratagene |

| pET24a | T7-tagged expression vector, Kanr | Novagen |

| pGEX-4T1 | GST fusion vector | Pharmacia |

| pSM100 | 800-bp PCR product in pGEM-T Easy | This study |

| pSM101 | 20-kb P. aeruginosa cosmid in pLAFR1 | This study |

| pSM102 | 4.5-kb EcoRI fragment from pSM101 in KS+ | This study |

| pSM103 | 1.8-kb EcoRI-EcoRV fragment from pSM102 in KS+ | This study |

| pSM104 | 1.1-kb EcoRI-HindIII clone in pGEM-T Easy | This study |

| pSM105 | 1.1-kb EcoRI-HindIII clone in pET24a | This study |

| pSM106 | K86A mutation in stk1 gene in pGEM-T Easy | This study |

| pSM107 | K86A mutation in stk1 gene in pET24a | This study |

| pSM200 | BamHI-NotI fragment from pSM105 in pGEX-4T1 | This study |

| pWB101 | 726-bp EcoRI-HindIII fragment of stp1 in pET24a | This study |

| pSM202 | BamHI-NotI fragment from pWB101 in pGEX-4T1 | This study |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| 1 | GGAATTCATGCAACGCACCGAGCCCTG | |

| 2 | AAGCTTTCAGGGACAGCGAAGGCA | |

| 3 | GGAATTCATGAACGAACCGC | |

| 4 | AAGCTTTCAACGGGCAAGAACGCC | |

| 5 | GGTCGGGGCGGCGAAGGCGAA | |

| 6 | GCAGCGCTAGCGCTACCAGCGGCGCCGGGT | |

| 7 | GGTAGCGCTAGCGCTCAACGAGTCGGT | |

| 8 | GGAAGCTTTCAGGGACAGCGAAGGCA | |

| 9 | AGTTCGTAGAGGACGCAGGC | |

| 10 | GACGGCCGTGGTGATCCGCC |

Cloning of the stk1 and stp1 genes from P. aeruginosa PAO1.

By using oligonucleotides 9 and 10 derived from the conserved sequence of serine-threonine kinases from M. tuberculosis (7, 11), an 800-bp fragment from P. aeruginosa was PCR amplified. The PCR reaction was carried out in a 50 μl of reaction volume containing 1× PFU buffer, 2.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 2 ng of P. aeruginosa chromosomal DNA, and 2.5 U of Pfu polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) under the following conditions: 95°C for 2 min, 53°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 2 min per cycle for 30 cycles. The amplified DNA was purified and was cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector to generate pSM100. The insert was sequenced, and the translated sequence showed 50% sequence identity to the Ser/Thr kinase gene from S. coelicolor. In order to clone the complete gene from P. aeruginosa, the 800-bp DNA was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by random priming (Amersham Life Sciences) and used as a probe to screen the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genomic library. A cosmid clone of ∼20 kb (pSM101) was isolated. Subsequently, a 4.5-kb EcoRI fragment from pSM101 was subcloned into pKS+ to generate pSM102, and a 1.8-kb EcoRV-EcoRI fragment was further subcloned from pSM102 into pKS+ to generate pSM103. The plasmid pSM102 was sequenced on both strands at the Cancer Research Center of the University of Chicago. The sequence was translated by using Expasy translate tool and was aligned by using the Align program.

Purification of the Stp1-GST fusion protein.

The upstream region of the pSM103 was sequenced and an open reading frame (ORF) was identified. By using two oligonucleotides with EcoRI (oligonucleotide 1) and HindIII (oligonucleotide 2) restriction sites (Table 1), the 726-bp ORF was PCR amplified and cloned into pET24a as pWB101. A BamHI/NotI fragment was excised and cloned into pGEX-4T1 to generate pSM202. The glutathione S-transferase (GST)-phosphatase fusion protein was purified by using a glutathione-Sepharose 4B affinity column. The Stp1 fusion protein was visualized for the expressed protein by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 12.5% gel and also by Western blot with an anti-GST monoclonal antibody (Pierce Company, Rockford, Ill.).

Characterization of the Stp1 phosphatase.

With p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) as a substrate, the Stp1 phosphatase activity was determined by adding 2 μg of the purified phosphatase in 20 μl of buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8] with 0.1% dithiothreitol [DTT]). The samples were incubated in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+, 5 mM Mn2+, or 5 mM Mg2+ ions for various time points, and the absorbance was measured at 410 nm with a Shimadzu Biospec 1601 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Instruments, Inc., Wood Dale, Ill.). The optimal concentration of Mn2+ was also determined by the above method with different concentrations of MnCl2. The effect of various inhibitors such as EDTA (10 and 100 mM), okadaic acid (0.1, 10, and 100 μM), NaF (5, 50, and 500 mM), and sodium vanadate (2, 20, and 200 μM) were also tested according to a similar procedure.

In order to show that the purified Stp1 phosphatase exhibited a Ser/Thr phosphoprotein phosphatase activity, casein was labeled at the Ser/Thr residues with [γ-32P]ATP by using cyclic AMP-dependent casein kinase II (CKII) in 20 μl of TMD buffer and was incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The unincorporated [γ-32P]ATP was removed by a G50 Sephadex Quick Spin column. The 32P-labeled casein was incubated with the purified Stp1 (∼2 μg) in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH8.0), 5 mM MnCl2, and 0.1% DTT at 30°C. The total reaction volume was 400 μl. Four 100-μl aliquots were taken at 0, 30, 60, and 90 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 5 μl of 2× SDS-gel loading buffer, and 30 μl of the sample was analyzed by SDS-PAGE on a 12.5% gel. The amount of 32P-labeled casein was estimated by exposing the gel to a phosphorimager cassette by using a STORM 860 phosphorimager.

Purification of the Stk1-GST fusion protein.

In order to express the Ser/Thr kinase as a GST fusion protein, the 1.1-kb BamHI-NotI fragment from pSM105 was excised and ligated into the compatible sites of pGEX-4T1 (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) to generate pSM200. pSM200 was transformed into E. coli BL21 for protein induction. The fusion enzyme was induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and was purified by glutathione-Sepharose 4B affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified protein was tested for purity by SDS–12.5% PAGE and also by Western blotting with the anti-GST monoclonal antibody.

Purification of Stk1-T7 tag fusion protein.

In order to overexpress the stk1 gene, PCR with oligonucleotides 3 and 8 (Table 1) and pSM103 as the template was performed. The PCR reaction was carried out in a 50-μl reaction volume with Pfu buffer, 2 mM dNTP concentrations, and Pfu polymerase at 95°C for 2 min, 55°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 2 min for 25 cycles. The 1.1-kb PCR product obtained was digested with EcoRI and HindIII and was cloned in frame with the N-terminal sequence of the gene 10 leader peptide of phage T7 (T7 tag) of pET24a to generate pSM105. The plasmid pSM105 was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) for induction of the Stk1 protein. The induced protein was purified by using T7-conjugated affinity chromatography (Novagen, Madison, Wis.).

Construction of K86A mutation in Stk1.

A K86A mutation in stk1 was constructed by two-step overlapping PCR according to the method of Ho et al. (12). In the first step, two independent PCR reactions were performed. By using an external oligonucleotide at the 5′ end of stk1 (oligonucleotide 3) and an internal altered oligonucleotide (oligonucleotide 6), a PCR was performed with pSM102 as the template. Similarly, by using a combination of the altered oligonucleotide 7 and the 3′-end oligonucleotide 8, a second PCR reaction was performed. The PCR products were purified and mixed in appropriate proportions, and the second-step PCR reaction to obtain the entire 1.1-kb gene was performed with the flanking oligonucleotides 3 and 8. The PCR reactions were carried out in a 50-μl volume with Pfu polymerase. The PCR product was cloned in pGEM-T Easy and was designated pSM106. The K86A mutation in the mutant stk1 created an NheI restriction site and was confirmed by restriction analysis.

Immunoprecipitation of Stk1 and kinase assays.

E. coli BL21(DE3) strain was transformed with pSM105 (wild type) or pSM107 (K86A). pSM105 carries the stk1 gene cloned in frame with the T7 tag. Similarly, pSM107, which carries a K86A substitution in the stk1 gene that was generated by site-directed mutagenesis, was also cloned in frame with the T7 tag. E. coli cells harboring these constructs were induced with 1 mM IPTG. Both the wild-type and K86A mutant proteins were purified by immunoprecipitation.

Approximately 200 μg of cellular protein was added to 40 μl of 50% slurry containing T7-monoclonal antibody Sepharose conjugate (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). The Sepharose conjugate was rinsed and washed with TNN buffer (Tris-HCl, 50 mM, pH 7.5; NaCl, 10 mM; 0.1% NP-40) prior to mixing and was set to slow rocking for 2 h at 4°C. The immunoprecipitate was washed once with TNN buffer and thrice in TMD buffer by low-speed centrifugation. Finally, the immunoprecipitated protein was assayed for kinase reaction in a buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM DTT, 2.5 μM ATP, 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, and histone H1 (2 μg) as the substrate. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min, after which the reaction was terminated by the addition of 2 μl of SDS sample buffer, and the proteins were separated by SDS–12.5% PAGE and autoradiographed.

Phosphoamino acid analysis.

The phosphorylated Stk1 protein corresponding to the expected 39 kDa was excised from the gel, eluted with deionized distilled water, and hydrolyzed with 6 N HCl at 110°C for 1 h as described by Boyle et al. (3). The hydrolyzate was lyophilized and resuspended in a solution containing nonradioactive phospho-Ser, phosho-Thr, and phospho-Tyr (Sigma). The sample was resolved on a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate (CBS Scientific) by electrophoresis in a buffer containing formic acid-glacial acetic acid-water (25:78:897) in the first dimension at pH 1.9 for 20 min at 1.5 kV. The TLC plate was dried in an oven and electrophoresed in the second dimension in a buffer containing glacial acetic acid-pyridine-water (50:5:945) at pH 3.5 for 16 min at 1.3 kV. The TLC plate was dried in the oven for 10 min at 65°C. The positions of the three standard phosphoamino acids were detected by staining with ninhydrin. The TLC plate was exposed to an X-ray film for 7 days and was subsequently developed.

RT-PCR and Northern hybridization.

Total mRNA from a mid-log-phase P. aeruginosa PAO1 culture was isolated by using the hot-phenol extraction method (22). The isolated RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) and was purified by using the RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, San Diego, Calif.). Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was performed by using the Superscript One-Step RT-PCR system (Gibco-BRL) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. About 2.5 μg of total RNA was used for each reaction in a total 50-μl reaction volume. The cDNA synthesis was performed at 50°C for 30 min, followed by denaturation at 94°C for 2 min. By using various oligonucleotide combinations (see Fig. 8 and Table 1), amplification was carried out at 94°C for 15 s, 54°C for 90 s, and 72°C for 90 s per cycle for 30 cycles, with a final extension at 72°C for 6 min. The amplified products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. For Northern analysis, ca. 25 μg of the RNA isolated from the mid-log-phase culture was analyzed on a 1.8% agarose gel containing formaldehyde and was transferred onto a nylon membrane (Amersham). The membrane was UV cross-linked and then hybridized at 65°C either with the stk1 or stp1 gene labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by random priming. The blots were washed twice with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) with 0.1% SDS for 30 min and were then autoradiographed.

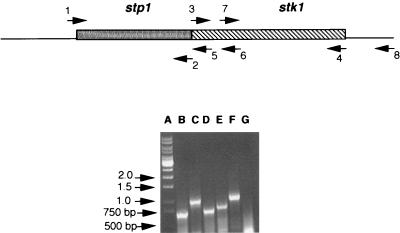

FIG. 8.

RT-PCR analysis showing the contranscription of stp1 and stk1 genes from P. aeruginosa PAO1. Lanes: A, DNA markers (kilobases); B, primer combination 1 and 2; C, primer combination 3 and 4; D, primer combination 7 and 4; E, primer combination 1 and 5; F, primer combination 1 and 6; G, primer combination 3 and 8. All of the PCR products were of the expected sizes, and there was no amplification of the cDNA when primers 3 and 8 were used (control).

RESULTS

Characterization of stk1 and stp1 genes from P. aeruginosa.

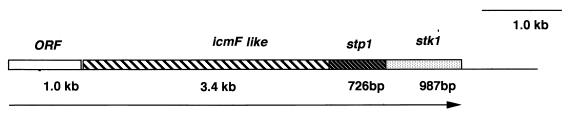

An 800-bp PCR-amplified DNA from P. aeruginosa (pSM100) with sequence similarity to conserved M. tuberculosis Ser/Thr kinase genes (7) was used to screen a PAO1 genomic library. A 20-kb cosmid clone that hybridized to this probe was identified (pSM101). A 4.5-kb EcoRI fragment, which showed positive hybridization with the probe, was then subcloned into pKS+ to generate pSM102. DNA sequence analysis of pSM102 revealed two ORFs with one nucleotide overlap (Fig. 1). The ORF1 is 726 bp (termed stp1) and encodes a 242-amino-acid protein (27 kDa), which showed 34% identity at the amino acid level to phosphatases from B. subtilis and M. tuberculosis (Fig. 2B). The serine/threonine phosphatases vary in size from 28 kDa (B. subtilis) to 57 kDa (M. tuberculosis). There are 11 conserved motifs in the PPM family (which includes PP2C) of phosphatases, and the Stp1 has most of the 11 conserved motifs (Fig. 2B), like the PP2C subfamily of phosphatases (2, 24).

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the Ser/Thr phosphatase (stp1) and Ser/Thr kinase (stk1) of P. aeruginosa PAO1. A 4.5-kb EcoRI fragment encodes two overlapping ORFs, stp1 and stk1. The stp1 ORF is 726 bp and encodes a Ser/Thr phosphatase belonging to the PP2C family. The stk1 ORF is 987 bp and encodes a Hank’s type Ser/Thr kinase. Upstream of stp1 is an ORF with sequence similarity to the L. pneumophila icmF gene. A search of the P. aeruginosa genome database indicated the presence of yet another ORF with very little intervening sequence, suggesting that stp1 and stk1 genes might be a part of a regulon.

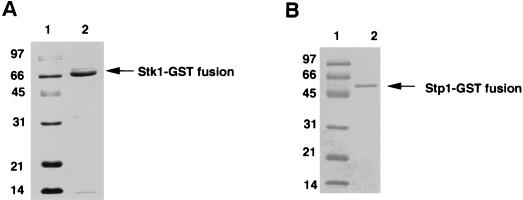

FIG. 2.

(A) Amino acid sequence alignment of P. aeruginosa (P.a) Stk1 with M. tuberculosis (M.t), S. coelicolor (S.c), and M. xanthus (M.x) kinases. The conserved residues are indicated by the asterisk, and various motifs described in the text are marked. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of P. aeruginosa (P.a) Stp1 with M. tuberculosis (M.t) and B. subtilis (B.s) phosphatases. The conserved residues are indicated by the asterisk, and various motifs described in the text are marked.

The second ORF (with a one-nucleotide overlap with ORF1) encodes a 329-amino-acid protein with sequence similarity to Ser/Thr kinases (termed stk1). The translated gene product has an estimated molecular mass of 39 kDa. The amino acid sequence of the kinase contains essentially all of the consensus subdomains (Fig. 2A). The translated protein sequence showed an overall 35% identity with several bacterial Ser/Thr kinases. The alignment of the Stk1 sequence with that of the Ser/Thr kinase of S. coelicolor and of M. tuberculosis is shown in Fig. 2A. The Stk1 sequence differs significantly from the S. coelicolor kinase PkaA in the domains I, VI, VIII, IX, and X. For example, in domain I, Stk1 has the sequence of GAGGMGTV, whereas PkaA has GRGATGTV. Domain VI of Stk1 has the sequence HGDLKPSNVML, while PKaA has HRDLKPANVLL. Domain VIII of Stk1 has GYAAPE, while PkaA has AYVAPE. Domain IX of both has the conserved aspartic acid, but the flanking sequences are different. The prokaryotic family of Ser/Thr kinases vary in size from 47 to 110 kDa. It is interesting to note that all of the 11 conserved domains are located toward the amino and central regions of the protein, whereas the C-terminal regions show considerable variation and, therefore, only the homologous regions are shown in Fig. 2A (10). The Stk1 is the smallest functional kinase observed thus far compared to the M. tuberculosis (47 kDa), M. xanthus (87 kDa), and S. coelicolor (58 kDa) Ser/Thr kinases.

Characterization of the Stk1 enzyme.

To demonstrate that the stk1 gene encodes a functional protein kinase, E. coli carrying pSM105 was induced with IPTG to allow expression of the stk1 gene, and the protein was purified by immunoprecipitation by using T7-monoclonal antibody.

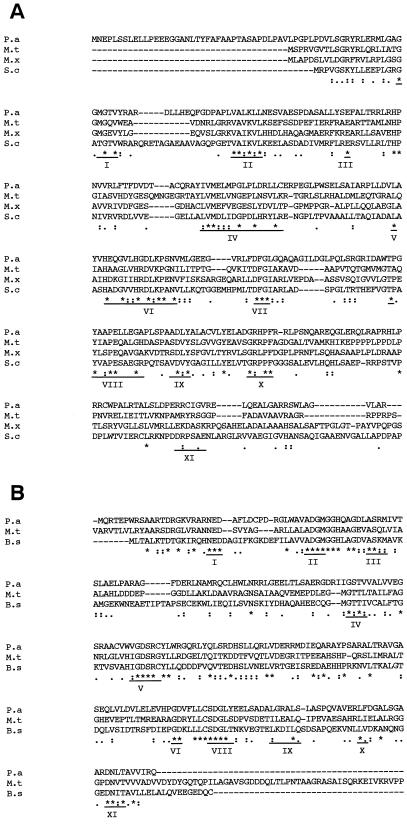

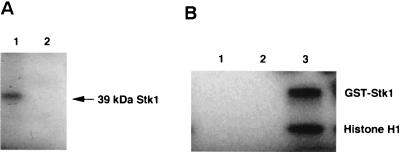

The stk1 gene was also cloned as a GST fusion by excising the 1.1-kb BamHI-NotI fragment from pSM105 and ligating it into the pGEX-4T1 vector. The purified protein was analyzed by SDS–12.5% PAGE as shown in Fig. 3A, lane 2. The purified protein was also tested by Western blot analysis with the anti-GST monoclonal antibody and showed positive cross-reaction (data not shown). The estimated size of the fusion product (GST-Stk1) is 67 kDa. The T7-tagged immunoprecipitated purified Stk1 was used for autophosphorylation in a kinase reaction buffer by using [γ-32P]ATP. As shown in Fig. 4A (lane 1), a 39-kDa phosphorylated protein was detected, whereas the Stk1 mutant (K86A) did not undergo autophosphorylation (Fig. 4A, lane 2). Thus, K86 is critical for catalyzing the phosphorylation reaction. The lysine residue is an invariant residue that is involved in the autophosphorylation reaction among all of the Ser/Thr kinases studied (6, 13). In order to see if the overexpressed Stk1 is active, we tested its ability to phosphorylate histone H1, a commonly used substrate for such kinases (17). As shown in Fig. 4B, the purified autophosphorylated Stk1 phosphorylated the histone H1 (lane 3). In presence of heat-inactivated Stk1 and [γ-32P]ATP (lane 1) or in presence of [γ-32P]ATP alone (lane 2), no phosphorylation of histone H1 was observed, a result suggesting that phosphorylation was catalyzed by Stk1.

FIG. 3.

(A) Purification of the P. aeruginosa Stk1 as a GST fusion in E. coli. Lanes 1, molecular mass standards; 2, Stk1-GST fusion protein (67 kDa). (B) Purification of the P. aeruginosa Stp1 as a GST fusion in E. coli. Lanes 1, molecular mass standards; 2, Stp1-GST fusion protein (53 kDa).

FIG. 4.

(A) Autophosphorylation of the purified Stk1 (wild-type) and Stk1 (K86A) mutant proteins by using [γ-32P]ATP. First, 2 μg of the purified kinase and the K86A mutant protein were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in TMD buffer for 10 min before being loaded onto an SDS–12.5% PAGE gel. A 39-kDa phosphorylated band was observed in lane 1 (wild-type Stk1), whereas no such phosphorylated band was observed with the mutant protein (lane 2). (B) Phosphorylation of the histone H1 protein by Stk1. A total of 2 μg of histone H1 was incubated with 2 μg of the GST-Stk1 for 10 min. The reaction mixture was analyzed on an SDS–12% PAGE gel and autoradiographed. Lane 1, boiled Stk1 plus histone H1 plus [γ-32P]ATP; lane 2, histone H1 plus [γ-32P]ATP; lane 3, Stk1 plus histone H1 plus [γ-32P]ATP.

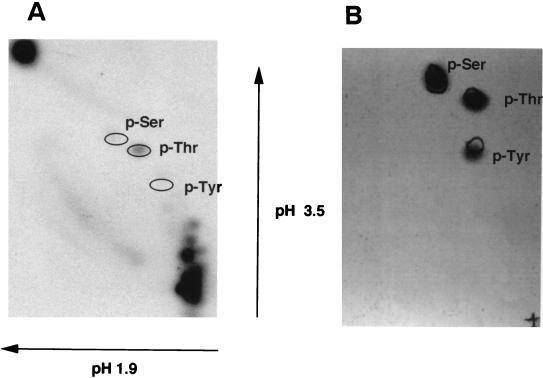

Phosphoamino acid analysis of the Stk1 kinase.

To identify the amino acid residue(s) that underwent phosphorylation, we performed a two-dimensional-phosphoamino acid analysis of the 32P-labeled T7-tagged Stk1 protein. It is clear from the phosphoamino acid analysis that Stk1 was labeled predominantly at the threonine residue and weakly at the serine residue (Fig. 5A). The relative positions of the standard P-serine, P-threonine, and P-tyrosine as stained by ninhydrin overlapped with the 32P-phosphorylated threonine and serine residues of the purified Stk1 (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

(A) Phosphoamino acid analysis of the purified Ser/Thr kinase, Stk1, from P. aeruginosa. Stk1 was expressed in E. coli and purified as a T7-tag fusion protein. The kinase was autophosphorylated and two-dimensional phosphoamino acid analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Threonine is strongly phosphorylated, and serine is weakly phosphorylated, whereas tyrosine is not phosphorylated at all. (B) Ninhydrin staining of the TLC plate showing the relative positions of the phosphoamino acids.

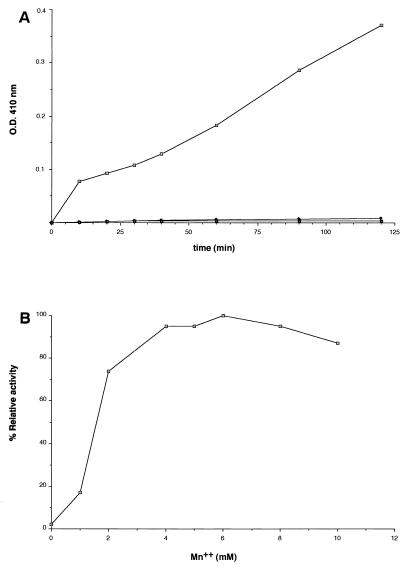

Characterization of the Stp1 phosphatase.

The gene demonstrating sequence homology to known phosphatases was cloned from pWB101 as a 726-bp BamHI-NotI fragment into pGEX-4TI as a gst gene fusion to generate pSM202. The plasmid pSM202 was introduced into E. coli BL21 and induced for protein expression, and the purified fusion protein was isolated as described for Stk1. SDS-PAGE analysis demonstrated the presence of a 53-kDa fusion protein (Fig. 3B), which showed a positive cross-reaction to the anti-GST monoclonal antibody (data not shown). The phosphatase activity of the purified Stp1 was tested by pNPP hydrolysis monitored at 410 nm. The phosphatase activity was observed only in the presence of Mn2+ but not in the presence of other divalent cations, such as Ca2+ or Mg2+ (Fig. 6A). The optimal Mn2+ concentration was determined by varying the concentrations of MnCl2 and was found to be 5 to 6 mM (Fig. 6B). The Ser/Thr phosphatase activity of the Stp1 was demonstrated by its ability to dephosphorylate labeled casein as shown in Fig. 7. Lanes 3, 4, and 5 show a significant decrease in signal compared to lane 1 (control), which was incubated in the absence of the enzyme for 90 min. The casein was phosphorylated at Ser and Thr residues by CKII kinase. A boiled control (Fig. 7, lane 2) was included to show that boiling did not appreciably lower the radioactivity, since boiling was part of the processing of the samples in lanes 3, 4, and 5. Inhibitors such as NaF or EDTA inhibited the activity of Stp1 at high concentrations (Table 2). Okadaic acid, a potent inhibitor of PP2A and PP2B family of phosphatases (16), did not inhibit the Stp1 phosphatase, which is one of the unique characteristics of the PP2C family of phosphatases. Similarly, sodium vanadate, a tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor, did not affect the Stp1 phosphatase activity at normal inhibitory concentrations (Table 2). Thus, Stp1 is a PP2C phosphatase.

FIG. 6.

(A) Effect of divalent cations on the Stp1 activity as determined by pNPP hydrolysis. Symbols: Mn++ (□), Ca++ (■), Mg++ (⧫). (B) Effect of manganese ion concentration on the Stp1 activity as determined by pNPP hydrolysis.

FIG. 7.

Activity of the purified P. aeruginosa Stp1 phosphatase overexpressed in E. coli. Phosphorylated casein was treated with the purified Stp1, and the dephosphorylated casein protein was analyzed by SDS–12.5% PAGE. Lane 1, phosphorylated casein (unboiled); lane 2, phosphorylated casein (boiled); lanes 3, 4, and 5, phosphorylated casein incubated with the purified Stp1 phosphatase for 30, 60, and 90 min, respectively. The radioactivities were measured by a phosphorimager, and the percent bound radioactivities are depicted below.

TABLE 2.

Inhibitors of Stp1 activity

| No. | Inhibitors (concn) | % Relative activitya |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control | 100 |

| 2 | EDTA (10 mM) | 14 |

| EDTA (100 mM) | 0 | |

| 3 | Sodium fluoride (5 mM) | 50 |

| Sodium fluoride (50 mM) | 10 | |

| Sodium fluoride (500 mM) | 0 | |

| 4 | Okadaic acid (100 nM) | 92 |

| Okadaic acid (10 nM) | 95 | |

| Okadaic acid (100 μM) | 95 | |

| 5 | Sodium vanadate (2 μM) | 95 |

| Sodium vanadate (20 μM) | 95 | |

| Sodium vanadate (200 μM) | 95 |

Activity was measured by pNPP hydrolysis at 410 nm in the absence or the presence of various inhibitors.

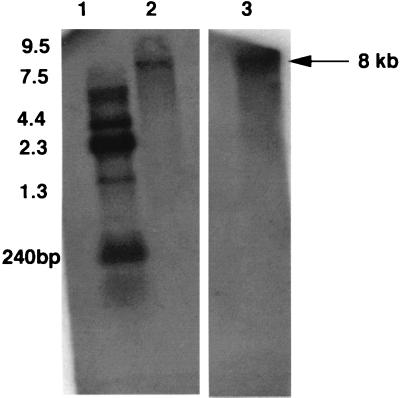

stk1 and stp1 are cotranscribed.

The sequence data in Fig. 1 showed that there is one nucleotide overlap between the end of stp1 and the beginning of stk1, suggesting that these two genes might be cotranscribed. Indeed, the sequence data further upstream of stp1 showed that both stp1 and stk1 might be part of a larger regulon encompassing the icmF-like gene and perhaps other genes as well. Since coregulation of a Ser/Thr kinase with its cognate phosphatase has never been reported, we were interested in knowing whether stp1 and stk1 might be cotranscribed, perhaps with icmF. We performed RT-PCR by using a single step RT-PCR kit from Gibco-BRL with various combinations of oligonucleotides. As shown in Fig. 8, a 750-bp amplification corresponding to the size of the stp1 gene was obtained when a set of oligonucleotides 1 and 2 was used (Fig. 8, lane B). Similarly, when the pair of oligonucleotides 3 and 4 was used, a 1-kb amplification corresponding to the stk1 gene was obtained (Fig. 8, lane C). Primer combinations 7 and 4 yielded, as expected, a shorter PCR product (Fig. 8, lane D) than primer combinations 3 and 4 (Fig. 8, lane C). By using combinations of oligonucleotides 1 and 5 and oligonucleotides 1 and 6, 835- and 950-bp products were obtained, respectively (Fig. 8, lanes E and F). When the combination of oligonucleotides 3 and 8 was used, no cDNA amplification was observed (Fig. 8, lane G), suggesting that the transcriptional unit does not extend beyond the stk1 gene. Based on the results of RT-PCR analysis, we concluded that the stp1 and the stk1 genes are in tandem and are cotranscribed.

In order to determine the size of the transcript formed during transcription of the stp1 and stk1 genes, we performed Northern hybridizations by using RNA isolated from P. aeruginosa PAO1. With the stp1 gene used as a probe, an approximately 8-kb transcript was detected (Fig. 9, lane 2). When the stk1 gene was used as a probe, a similar-sized transcript was again detected (Fig. 9, lane 3), implying that both stp1 and stk1 transcripts are present in a single fragment of 8 kb, presumably representing transcription of a larger operon with an icmF homologue and other genes upstream.

FIG. 9.

Northern blot analysis of the stp1 and stk1 genes from P. aeruginosa. Lanes: 1, RNA markers; 2, RNA probed with stp1 gene; 3, RNA probed with the stk1 gene.

DISCUSSION

One of the unique features of eukaryote-like Ser/Thr or Tyr kinases and their cognate phosphoprotein phosphatases is the presence of multiple genes for these enzymes both in eukaryotes and in prokaryotes (24). In prokaryotes, such enzymes have been detected in E. coli, M. tuberculosis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, S. coelicolor, M. xanthus, and other strains. In M. tuberculosis, there are 11 copies of Ser/Thr kinase genes (4), 5 in M. xanthus (31), and at least 3 or 4 in P. aeruginosa (20a). In M. xanthus, the two Ser/Thr kinases Pkn5 and Pkn6 have reciprocal roles in cellular development and fruiting body formation (33). In the filamentous Anabaena cyanobacterium, the Ser/Thr kinase gene pknE is located 301 bp downstream of the Ser/Thr phosphatase gene prpA but are independently regulated (32). This is in contrast to P. aeruginosa stp1 and stk1 genes that are cotranscribed. Anabaena PrpA and PknE function to regulate the level of phosphorylated proteins involved in nitrogen fixation and heterocyst formation (32). A eukaryote-like Ser/Thr kinase has been shown to phosphorylate AsfR protein involved in secondary metabolism in Streptomyces species (18). Like the Yersinia protein Ser/Thr kinase YpkA, which is known to be involved in Yersinia virulence by a type III mechanism (5, 8, 9), a Ser/Thr kinase, in contrast to the Ser/Thr kinase described here, has been shown to contribute to P. aeruginosa virulence in neutropenic mice (29). No biochemical characterization or genetic regulation of this kinase has been described. It would thus be of great interest to develop antibodies and gene fusions to examine whether Stk1 and Stp1 may modulate P. aeruginosa virulence, perhaps by a type III secretion mechanism, as demonstrated for exoenzyme S and other virulence factors (27, 28).

The coregulation of stp1 and stk1 genes is interesting. As previously mentioned, the corresponding Anabaena genes, prpA and pknE, while clustered together, are independently regulated (32). Since the Stk1 kinase and the Stp1 phosphatase act in a reciprocal manner to maintain the level of phosphorylation of target proteins, it is interesting that two Ser/Thr kinases, the cytoplasmic Pkn5 and the transmembrane protein Pkn6, act reciprocally to balance fruiting body formation and cellular development in M. xanthus (33). If an Stk1/Stp1 combination is involved in virulence in P. aeruginosa, a likely target (other than host cell signaling proteins) would be the enzymes involved in alginate synthesis. Alginate is a capsular polysaccharide in P. aeruginosa that is believed to protect the infecting cells from host cell defense and antibiotic therapy in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients, thereby contributing to P. aeruginosa virulence (19). There are two regulatory proteins, AlgR1 and the histone H1 homologue AlgR3 (14), which are important for alginate gene activation (19). We have shown that histone H1 is a substrate for Stk1 (Fig. 4B). Both AlgR1 and AlgR3 have the potential signature motifs SAR and RXT, respectively, for phosphorylation by Ser/Thr kinases, as does P. aeruginosa IcmF. It would be interesting to examine whether purified AlgR1, IcmF, and/or AlgR3 would be targets for Stk1 and whether the phosphorylated forms in turn could be dephosphorylated by Stp1. At present, however, histone H1 is the only protein that has been used as a substrate.

An interesting aspect of the genetic organization of stk1 and stp1 genes is their close association with an icmF-like gene (Fig. 1). Since the RT-PCR experiment indicated that the transcript stops at the end of the stk1 gene (Fig. 8), it is likely that the large transcript for stk1 and stp1 genes also includes the icmF gene. The IcmF from P. aeruginosa is 48% similar (at the amino acid level) to that of the L. pneumophila IcmF protein. The icm genes, including icmF in L. pneumophila, are required for intracellular replication in the macrophages (1), for macrophage cell death (21), and for plasmid conjugation (23). The IcmF protein is localized in the inner membrane of Legionella and presumably plays an accessory role by translocating macromolecules that are involved in macrophage killing. Thus, by analogy, the IcmF homolog in P. aeruginosa might also be involved in translocating potential virulence factors such as Stk1 and Stp1 that may be involved in the killing of host eukaryotic cells and are thus coregulated. Further studies are needed to determine whether IcmF-like protein of P. aeruginosa may play a role in the secretion of Stk1/Stp1 in the host cell by a type III mechanism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI 16790-18 from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Lester Lau and Yanzhuang Li of the Department of Molecular Genetics for help in the phosphoamino acid analysis of the phosphorylated Stk1 protein and Dianah Jones-James for typing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bettina C B, Sadosky A B, Shuman H A. The Legionella pneumophilia icm locus: a set of genes required for intracellular multiplication in macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:797–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bork P, Brown N P, Hegyi H, Schultz J. The protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) superfamily: detection of bacterial homologues. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1421–1425. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle J W, Geer P V D, Hunter T. Phosphopeptide mapping and phosphoaminoacid analysis by two-dimensional separation on thin-layer cellulose plates. Methods Enzymol. 1991;201:110–149. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01013-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Rajandream M-A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston J E, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornelis R G. The Yersinia deadly kiss. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5495–5504. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5495-5504.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorado M J, Inouye S, Inouye M. A gene encoding a protein serine/threonine kinase is required for normal development of M. xanthus, a gram-negative bacterium. Cell. 1991;67:995–1006. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gay A, Davies J. Components of eukaryotic-like protein signaling pathways in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microb Com Gen. 1997;2:63–73. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaylov E E, Hakansson S, Forsberg A, Wolf-Watz H. A secreted protein kinase of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is an indispensable virulence determinant. Nature. 1994;361:730–732. doi: 10.1038/361730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaylov E E, Hakansson S, Wolf-Watz H. Characterization of the operon encoding YpkA Ser/Thr protein kinase and the YpoJ protein of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4543–4548. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4543-4548.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanks S K, Quinn A M, Hunter T. The protein kinase family conserved features and deduced phylogeny of the catalytic domains. Science. 1988;241:42–52. doi: 10.1126/science.3291115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanks S K, Linderberg A. Use of degenerate oligonucleotide probe to identify clones that encode protein kinases. Methods Enzymol. 1991;200:525–532. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00168-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamps M P, Sefton B M. Neither arginine nor histidine can carry out the function of lysine-295 in the ATP binding site of p60src. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:751–757. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato J, Misra T K, Chakrabarty A M. AlgR3, a protein resembling eukaryotic histone H1, regulates alginate synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2887–2891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennelly P J, Potts M. Fancy meeting you here! A fresh look at ‘prokaryotic’ protein phosphorylation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4759–4764. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4759-4764.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackintosh C, Mackintosh R W. Inhibitors of protein kinases and phosphatases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:444–447. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maizels E T, Peters C A, Kline M, Cutler R E, Shanmugam M, Hunzicker-Dunn M. Heat-shock protein-25/27 phosphorylation by the ς isoform of protein kinase C. Biochem J. 1998;332:703–712. doi: 10.1042/bj3320703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto A, Hong S K, Ishizuka H, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Phosphorylation of the AfsR protein involved in secondary metabolism in Streptomyces species by a eukaryotic-type protein kinase. Gene. 1994;146:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90832-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.May T B, Chakrabarty A M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: genes and enzymes of alginate biosynthesis. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:151–157. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90664-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parkinson J S, Kofoid E. Communication modules in bacterial signaling proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:71–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Pseudomonas aeruginosa Genome Sequence. 15 March 1999, copyright date. [Online.] http://www.pseudomonas.com. [10 April 1999, last date accessed.]

- 21.Purcell M, Shuman H A. The Legionella pneumophila icm GCDJBF genes are required for killing of human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2245–2255. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2245-2255.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segal G, Purcell M, Shuman H A. Host killing and bacterial conjugation requires overlapping sets of genes within a 22-kb region of the Legionella pneumophila genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1669–1674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi L, Potts M, Kennelly P J. The serine, threonine and/or tyrosine specific protein kinases and protein phosphatases of prokaryotic organisms: a family portrait. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1998;22:229–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shortridge V D, Lazdunski A, Vasil M V. Osmoprotectants and phosphate regulate expression of phospholipase C in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:863–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urabe H, Ogawara H. Cloning, sequencing and expression of serine/threonine-encoding genes from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Gene. 1995;153:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00789-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vallis A J, Finck-Barbancon V, Yahr T L, Frank D W. Biological effects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secreted proteins on CHO cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2040–2044. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.2040-2044.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallis A J, Yahr T L, Barbieri J T, Frank D W. Regulation of ExoS production and secretion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in response to tissue culture conditions. Infect Immun. 1999;67:914–920. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.914-920.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Li C, Yang H, Mushegian A, Jin S. A novel serine/threonine protein kinase homologue of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is specifically inducible within the host infection site and is required for full virulence in neutropenic mice. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6764–6768. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6764-6768.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang C C. A gene encoding a protein related to eukaryotic protein kinases from the filamentous heterocystous cyanobacterium Anabaena PCC 7120. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11840–11844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang C C. Bacterial signalling involving eukaryotic-type protein kinases. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C C, Friry A, Peng L. Molecular and genetic analysis of two closely linked genes that encode, respectively, a protein phosphatase 1/2A/2B homolog and a protein kinase homolog in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2616–2622. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.10.2616-2622.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang W, Inouye M, Inouye S. Recirprocal regulation of the differentiation of Myxococcus xanthus by Pkn5 and Pkn6, eukaryotic like Ser/Thr protein kinases. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:435–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]